Abstract

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying lung cancer development have not been fully understood. The functions of histone deacetylases (HDACs), a class of total eighteen proteins (HDAC1–11 and SIRT1–7 in mammals) that deacetylate histones and non-histone proteins, in cancers are largely unknown.

Methods

Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice and HDAC7-depleted human lung cancer cell lines were used as models for studying the function of Hdac7 gene in lung cancer. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to explore the relationship between HDAC7 expression and prognosis of human lung cancers. Recombinant lentivirus-mediated in vivo gene expression or knockdown, Western blotting, and pull-down assay were applied to investigate the underlying molecular mechanism by which Hdac7 promotes lung tumorigenesis.

Results

The number and burden of lung tumor were dramatically reduced in Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice compared to control K-Ras mice. Also, in Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice, cell proliferation was significantly inhibited and apoptosis in lung tumors was greatly enhanced. Similarly, cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of human lung cancer cell lines expressing shHDAC7 were also significantly suppressed and apoptosis was dramatically elevated respectively. Mechanistic study revealed that Hdac7 mutation in mouse lung tumors or HDAC7 depletion in human tumor cell lines resulted in significantly enhanced acetylation and tyrosine-phosphorylation of Stat3 and HDAC7 protein directly interacted with and deacetylateed STAT3. The Hdac7 mutant-mediated inhibitory effects on lung tumorigenesis in mice and cell proliferation/soft agar colony formation of human lung cancer cell lines were respectively reversed by expressing dnStat3. Finally, the high HDAC7 mRNA level was found to be correlated with poor prognosis of human lung cancer patients.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that Hdac7 promotes lung tumorigenesis by inhibiting Stat3 activation via deacetylating Stat3 and may shed a light on the design of new therapeutic strategies for human lung cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12943-017-0736-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hdac7, Stat3, Acetylation & phosphorylation, Lung cancer

Background

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are a class of total eighteen proteins (HDAC1–11 and SIRT1–7 in mammals) that deacetylate histones and non-histone proteins [1]. HDACs play very important roles in diverse biological processes and related diseases such as cancers. High levels of HDACs is frequently associated with advanced cancers and poor prognosis [2]. However, HDACs also display tumor suppressive effects in some cancers, e.g. an HDAC2 truncating mutation was observed in human epithelial cancers [3]. Low expression of HDAC10 is associated with poor prognosis of lung and gastric cancers [4, 5]. Hdac2 −/− mice display a decreased intestinal tumors [6] while liver-specific Hdac3 KO mice develop hepatoma [7]. Furthermore, Hdac1 and Hdac2 function as tumor suppressors on preleukemic stage, but oncogenes for leukemia maintenance in PML-RAR-mediated mouse acute promyelocytic leukemia [8].

HDAC7 is a member of the HDAC family. Studies conducted on cell culture level by silencing or overexpressing HDAC7 have shown that HDAC7 is involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and migration. Hdac7 −/− mice are embryonic lethal due to a failure of angiogenesis (rupture of blood vessels) [9]. There are only a few reports studying the role of HDAC7 in cancers and even these scarce results were controversial. High HDAC7 protein level was observed in 9 out of 11 human pancreatic cancers [10]. HDAC7 together with HDAC1 is specifically over expressed in breast cancer stem cells (CSCs) and necessary to maintain CSCs [11]. High HDAC7 expression was associated with poor prognosis of 74 children with B-lineage CD10-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (≥95% common-ALL/pre-B ALL) [12]. All these results suggest an oncogenic function of HDAC7 in these human cancers. However, low HDAC7 expression was also observed in 75% of 28 pro-B-ALL samples [13] and reported to be associated poor prognosis of lung cancer patients [4]. This suggests a potential tumor suppressive function of HDAC7 in some other cancers and/or at different stages of cancer development.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a member of the STAT protein family. STAT3 activity is modulated by both acetylation and phosphorylation. In response to cytokines or growth factors, STAT3 is tyrosine-phosphorylated by receptor or nonreceptor kinases, forms dimmer and translocates into nucleus to activate the transcription of target genes implicated in a broad range of biological processes. In response to extracellular environmental factors including cytokines and nutrition, STAT3 acetylation is modulated by histone acetyl transferases/HDACs, e.g. p300/HDAC3, and therefore affecting its dimerization, phosphorylation, DNA binding and transactivation [14]. The STAT3 mutated at key acetylation sites abolishes its ability of dimerization, and consequently impairs its tyrosine-phosphorylation and so forth [14, 15]. STAT3 is thought to potently promote oncogenesis in a variety of tissues. The persistent tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 (pY-STAT3) and higher expression of STAT3 are observed in many human cancers and are often correlated with an unfavorable prognosis in these patients [16]. However, a growing number of reports also suggest a tumor-suppressive function of STAT3 in some cancers. The pY-STAT3 level is negatively correlated with tumor size and distant metastases of papillary thyroid carcinomas [17, 18]. High pY-STAT3 level is highly correlated with a better prognosis for soft tissue leiomyosarcoma, advanced rectal cancer and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [19–21]. Studies on mouse cancer models also reveal that Stat3 is a negative regulator for tumor progression in Apc mutant mice and in K-Ras mice [22, 23]. Furthermore, STAT3 promotes oncoprotein EGFRvIII-induced glial transformation when it forms a complex with EGFRvIII and conversely inhibits malignant transformation of astrocytes under Pten deficiency condition [24].

The role of STAT3 in lung cancer development appears complex. The expression of constitutive STAT3 (STAT3C) induced inflammation and adenocarcinomas in mouse lung [25]. STAT3 activation or high expression was initially reported to be associated with poor prognosis of lung cancer patients [26, 27]. However, it has recently been demonstrated that low STAT3 expression correlated with poor survival and advanced malignancy in human lung cancer patients with smoking history, and disruption of Stat3 signaling enhanced lung tumor initiation and malignant progression in mice [23]. Furthermore, almost at the same time, Zhou, et al., have shown that Stat3 can function as a tumor suppressor to prevent lung tumor initiation at an early stage of lung tumor development and an oncogene to facilitate lung cancer progression by promoting cancer cell growth at a late stage of lung cancer in the same K-Ras mice [28].

Here we report that Hdac7 functions as an oncogene in lung cancer. Higher HDAC7 protein level is observed in ~44% of human lung cancer samples and higher HDAC7 mRNA level is associated with poor prognosis of lung cancer patients. We also found that lung tumorigenesis was significantly inhibited in Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice. Hdac7 deficiency significantly inhibited proliferation and enhances apoptosis, respectively. The acetylation and phosphorylation of Stat3 were significantly enhanced in tumors from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice and HDAC7-depleted human tumor cell lines. We demonstrated that the Hdac7 mutant-mediated tumor suppression was rescued by expressing dnStat3 in mouse lung tumors. Finally, our studies showed that HDAC7 directly interacted with and deacetylated STAT3. Our studies may shed a light on the design of new therapeutic strategies for human lung cancer.

Methods

Mice

Hdac7 PB (PiggyBac) heterozygote mutant mice (thereafter called Hdac7 +/− mice or Hdac7 mutant mice), carrying an Hdac7 mutant allele disrupted by insertion of a PB transposon in the intron between exon 1 and 2, was generated on the FVB/NJ background. Mapping information of PB insertion in Hdac7 gene can be found in the PB mice database (http://idm.fudan.edu.cn/PBmice). LSL-K-Ras G12D mice (Stock No. 008179) were previously described [29] and LSL-K-Ras G12D allele was introduced into FVB genetic background through breeding with FVB mice for more than six generations (therefore called K-Ras mice or control mice). Hdac7 +/− mice were crossed with K-Ras mice to generate Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice. All mice were maintained on 12/12-h light/dark cycles. Experiments were conducted with consent from the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Developmental Biology and Molecular Medicine at Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

Lung tumor induction, enumeration and tumor burden analysis

Lung tumors were induced by the method described previously [30]. Briefly, 6-weeks-old Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice were infected with 5 × 107 plaque-forming units (PFU) of adenovirus (Ad-Cre) expressing Cre by intranasal inhalation, or 106 transforming unit (TU) of lentivirus (lenti-Cre or lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3) by tracheal instillation. Six weeks later, mouse lungs were retrieved and tumors on mouse lung surface were counted under dissection microscope. For tumor burden analysis, lungs were perfused through the trachea with 4% paraformaldehyde and fixed overnight followed by standard procedures for paraffin sections and H&E staining. Twelve randomly selected, lung sections/mice were scanned for 6 mice each genotype, total lung area occupied by tumor was measured and tumor burden was calculated as (area of lung section occupied by tumor)/(total area of section) in μm2 using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

TUNEL assay and EdU incorporation assay

TUNEL assay was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions for a kit (#G3250, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) assay, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 mg/kg EdU 6 weeks after Ad-Cre infection. Lung tissues were subjected to frozen section followed by EdU staining with a kit (#C10310–2, RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) 24 h after injection.

Plasmids

pFUW-Cre: A Cre fragment from MIGR1-Cre was cloned into of pFUGW to replace EGFP fragment. Plasmid pFUW-Cre-2A-dnStat3: A Cre fragment from pCS4-Cre and P2A–dnStat3 fragment from pCS4-dnStat3 were cloned into pFUGW to replace EGFP fragment. Plasmid pCMV6-Stat3-Flag: a PCR fragment of Stat3 was cloned into pCMV-Entry and in-frame fused to Flag tag. Plasmid pcDNA3.1-GST-Hdac7 (aa445–938): PCR fragments of GST and Hdac7 (aa 445–938) or Hdac7AWA (aa 445–938) were cloned into pcDNA3.1 and in-frame fused to Myc tag. Plasmid pLKO.1-shHDAC7: The selected ShHDAC7 targeting sequences were synthesized and cloned into pLKO.1. They are: shHDAC7 #1: ATCCGGGTGCACAGTAAATA, shHDAC7 #2: AAGTAGTTGGAACCAGAGAA, shHDAC7 #3: TCACTGACCTCGCCTTCAAAG.

Cell culture, virus preparation and infection

293T cells were cultured in as described [31]. Human lung cancer cells A549, H1299, H2009 and H522 were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS. Ad-Cre was prepared and titrated as previously described [32]. Recombinant lentiviruses were generated by co-transfecting lentivirus expression vectors and package plasmids (pCMV-VSV-G, pRSV-Rev and pMDLg/pRRE) into 293T cells and harvested 48 h later. Harvested lentiviruses for knockdown experiments were stored at −80 °C or directly used to infect human lung cancer cell lines. Hdac7-silencing or scrambled cells were selected with puromycin. Lentiviruses for infecting mice were further concentrated by PEG 6000 as described previously [33]. TU of lenti-Cre and lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 was determine by infecting 293T cells carrying LSL-EGFP transgenes followed the methods published [33].

MTT assay

Cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/well in 96-well plate and cultured for desired time periods. The medium was then replaced by 200 μl of fresh RPMI 1640 and 20 μl MTT (5.0 mg/ml) and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. 100 μl/well DMSO was added before reading OD 570 on a plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Annexin V assay

H1299 cells infected shHAC7 or scrambled lentivirus were gently dissociated with trypsin/EDTA and stained for annexin V and 7AAD using the eBioscience™ Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit APC (#88–8007-74, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The stained cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences). All annexin V positive cells were counted as apoptotic cells.

Soft agar assay

Soft agar assay was performed as previously described [34]. Briefly, cells were plated at a density of 500 cells/well in 6-well plates and cultured for 14–21 days. Colonies were stained with MTT and counted using Colony Counter software (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from wild type (wt) and Hdac7 mutant mouse lung tissue with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with TaKaRa RNA PCR kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and with Fast SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix on Mx3000P (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and data were analyzed with the MxPro software. Expression of Gapdh was used as an internal control. The primer sequence is: Hdac7-F: CCCAGTGTGCTCTACATTTCCC, Hdac7-R: CACGTTGACATTGAAGCCCTC.

Antibodies, immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Antibodies against the following proteins were used for our studies: HDAC7 (#ab53101) and AKAP12 (#ab49849) from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); acetylated lysine (#9441), STAT3 (#8768), Phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705)(#9145), Acetyl-Stat3 (Lys685)(#2523), JAK1(#3344), JAK2(#3230), PKC(#2056), p53(#2524) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA); anti-HA(#H3663), anti-FLAG(#F1804) and anti-β-Actin(A3854) from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MI, USA); Myc (#SC-40) from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Standard Western blot protocol was adopted. Images were acquired with Tanon-5200 and the density of bands was determined with Image J. The methods for immunoprecipitation was previously described [31].

GST pull-down assay and in vitro deacetylation assay

pCDNA3.1-GST-Hdac7(aa445–938), pCDNA3.1-GST-Hdac7(aa445–938)-AWA and pCMV6-Stat3-Flag were transfected into 293 T cells separately. Cells were lysed with RIPA (Radio immunoprecipitation assay) buffer 48 h after transfection. GST-Hdac7(aa445–938) and GST-Hdac7(aa445–938)-AWA fusion proteins were purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (#17–0756-01 GE Healthcare), and Flag-tagged Stat3 was purified with ANTI-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (#A2220, Sigma) and eluted with 3X FLAG peptide (#F4799, Sigma). For in vitro pull-down assays, purified proteins were incubated together in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer [31] for 1.5 h, followed by washing with PBS for three times, and finally analyzed by Western blot.

In vitro deacetylation assay was performed as described previously [35] with some modification. In brief, 0.5 μg purified Stat3 protein from 293 T cells was incubated with 0.5 μg purified GST-Hdac7(aa445–938) or GST-Hdac7(aa445–938)-AWA fusion proteins in deacetylation buffer (15 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 0.25 mM EDTA, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% (v/v) glycerol) for one hour at 37 °C. The reaction products were subjected to Western blot with anti-acetylated lysine antibody.

Human lung cancer samples and prognosis analysis of lung cancer patients

Clinical lung cancer samples obtained from Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China were used for immunoblot analysis.

For prognosis analysis of lung cancer patients, gene expression representative as FPKM (fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) derived from RNA-seq were downloaded from the TCGA project (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox’s proportional hazards regression were conducted by survival package in R (version: 3.2.3). Prognosis effect from HDAC7 was estimated by Peto & Peto modification of the Gehan-Wilcoxon test and conducted by survdiff function from survival package (R). Hazard ratio (HR) and corresponding 95%CI were estimated with Cox’s proportional hazards regression.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using an unpaired t test by GraphPad Prism (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

HDAC7 mutant inhibits lung tumorigenesis in mice

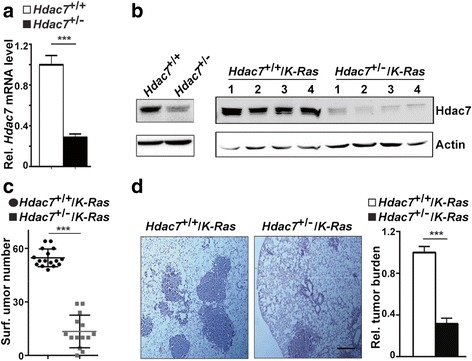

To investigate the role of Hdac7 in lung cancer, we first verified Hdac7 expression in wt and Hdac7 +/− mouse lung tissues. The results showed that both Hdac7 mRNA and protein levels were reduced by more than 50% in Hdac7 +/− mice compared to wt mice (Fig. 1a and b left panel). Then, Hdac7 +/− mice were crossed with K-Ras transgenic mice, the most frequently used mouse model for lung cancer [29]. The resulting Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice and control K-Ras mice were administrated with Ad-Cre to induce lung tumors (see Methods). The results showed that total tumor numbers on mouse lung surface (Fig. 1c) and tumor burden (Fig. 1d) were markedly reduced in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice compared with control mice. Immunoblotting also demonstrated again that Hdac7 expression in Hdac7 +/− mouse lung tumors was dramatically decreased (Fig. 1b right panel). These results suggest that Hdac7 mutant notably inhibits mouse lung tumorigenesis.

Fig. 1.

Hdac7 mutant inhibits lung tumorigenesis in mice. a. Statistical analysis of real-time qRT-PCR results for Hdac7 mRNA lever in normal lungs from wild type and Hdac7 heterozygous mutant mice. n = 3 for each genotypes. b. Western blot analyses of the Hdac7 protein level in normal lung tissues of wild type and Hdac7 +/− mice (left panel) and lung tumors from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice (right panel). Numbers above the blot in right panel represent the individual tumor from different mice. c. Statistical analysis of tumor number on mouse lung surface of Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice. Each dot/square represents an individual mouse. d. Histological (left panel) and quantitative (right panel) analyses of tumor burden. Left panel, histological images of H&E stained sections of lungs with tumors from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice, n = 6 for each genotypes. Bar 0.2 mm. Blots and images shown are representatives of three experiments. Values in (a and d) represent the means ± SD. of three separate experiments. ***, p < 0.001

Decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis in lung tumors of Hdac7+/−/ K-Ras mice

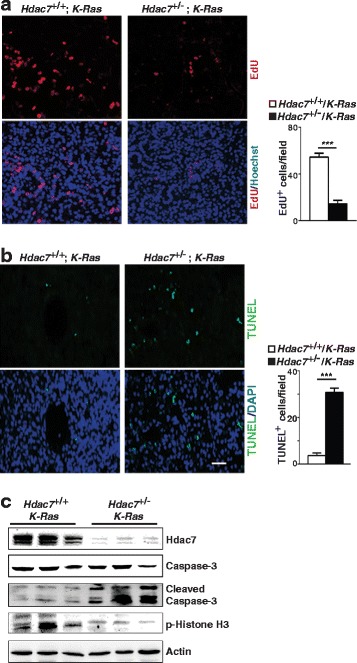

Cell proliferation and apoptosis play critical roles in cancer development. However, previously reported results about the role of HDAC7 in regulating cell proliferation of normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human cancer cell lines are controversial [36–38] and the functions of HDAC7 in apoptosis of different cells also appear varied [13, 39, 40]. To understand the cellular mechanism(s) by which Hdac7 mutant suppresses lung tumorigenesis, we evaluated cell proliferation and apoptosis in lung tumors of Hdac7 +/−/ K-Ras and control mice. Our in vivo EdU-pulse labeling experiments showed that cell proliferation was dramatically decreased in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras tumors (Fig. 2a). Our TUNEL assay also revealed that apoptosis in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras tumors was substantially increased (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the results of TUNEL and EdU labeling assay, more caspase-3 cleavage and less p-Histone H3 was observed in Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras tumor cells respectively (Fig. 2c). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that Hdac7 mutant can inhibit mouse lung cancer via attenuating cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Hdac7 mutant suppresses proliferation and enhances apoptosis of lung tumor cells in mice. a. Left panels: Representative florescent images of mouse lung sections stained for EdU-positive cells (red) in lung tumors. Right panel: Statistics analysis of EdU-positive cells per field. b. Left panels: Representative florescent images of mouse lung sections for TUNEL staining of apoptotic cells (green) in lung tumors. Right panel: representative statistics analysis of TUNEL positive cells per field. The genotypes of the mice were indicated above the images. Hoechst and DAPI was used for staining for nucleus, respectively. Bar 50μm. The EdU-positive or TUNEL-positive cells in tumor area of six randomly chosen fields/lung were counted on digital fluorescence images and more than five animals for each genotype were included. Values represent the means ± SD. ***, p < 0.001. c. Western blotting for caspase-3 cleavage and phosphorylation of Histone H3 in lung tumors from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and & control mice

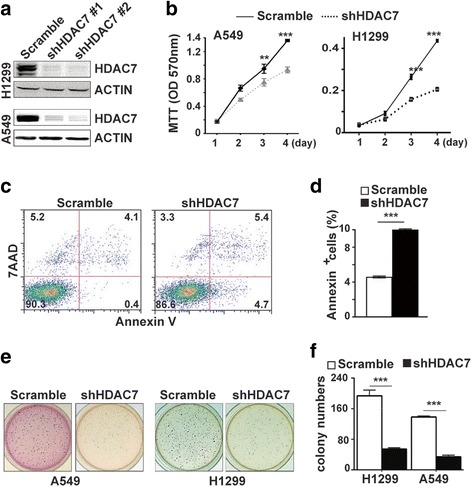

HDAC7 silencing suppresses growth of human lung cancer cells

Since in vivo study demonstrates that HDAC7 functions as an oncogenic factor in mouse lung cancer, we further reasoned that reduction of HDAC7 expression in human lung cancer cells could inhibit their growth. To verify this possibility and exam the biological impact of HDAC7 depletion on human lung cancer cells, we silenced HDAC7 expression by lentivirus-mediated shRNA in two human lung cancer cell lines (H1299 and H522) with wt K-RAS and two human lung cancer cell lines (A549 and H2009) with a mutant K-RAS to mimic the conditions of our mouse study (Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Figure S1B). The growth of H1299 and A549 cells expressing shHDAC7 was significantly inhibited (Fig. 3b). Annexin V assay showed that HDAC7 knockdown resulted in significant enhanced apoptosis of human lung cancer cells (Fig. 3c and d). Moreover, soft agar colony formation assay revealed that shHDAC7 markedly suppressed colony formation of H1299 and A549 cells in soft-agar (Fig. 3e and f). These results indicate that suppressing HDAC7 expression in human lung cancer cells may restrain human lung cancer development.

Fig. 3.

HDAC7 knockdown suppresses growth of human lung cancer cells. a, Representative Western blot of HDAC7 protein levels of human lung cancer cells, H1299 and A549, expressing shHDAC7 and scramble shRNA. b. The growth curves of human lung cancer cells, A549 and H1299, infected with lenti-shHDAC7 and control viruses. Cell growth was evaluated by MTT assay. c-d. HDAC7 knockdown induces apoptosis of human lung cancer cells. Representative flow cytometry of H1299/shHDAC7 and the control cells stained with Annexin V and 7AAD (c) and the statistical analyses (d) of FACS in c. Annexin V positive cells were counted as apoptotic cells. e-f. HDAC7 knockdown inhibits tumorigenecity of human lung cancer cells. Representative photographs of the soft agar colony formation assay for lung cancer cell lines, H1299 and A549, expressing shHDAC7 and scramble shRNA (e), and the statistical analyses (f) of the results of colony numbers formed in soft agar in e. Values in (b, d and f) represent the means ± SD. of three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01;***, p < 0.001

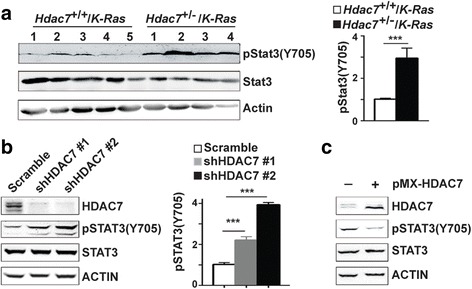

Loss of HDAC7 enhances STAT3 phosphorylation

Knockdown HDAC7 in multiple human cancer cell lines resulted in suppression of cell growth by down regulating c-MYC expression and up regulating p21 and p27 expression [38]. HDAC7 has also been shown to protect neurons from apoptosis by inhibiting c-JUN expression [39]. To investigate whether Hdac7 may regulate the proliferation and apoptosis of lung cancer cells by similar mechanisms, the expression of c-Myc, p21 and c-Jun in mouse lung tumors of Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice were evaluated by immunoblotting. The results showed that the protein levels of c-Myc, c-Jun and p21 were not considerably changed in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras lung tumors compared with the control K-Ras lung tumors (Additional file 1: Figure S1A).

Since HDAC7 silencing was reported to result in activation (phosphorylation of Tyr705) of STAT3 in HUVEC [41], we ask whether Hdac7 deficiency could also enhance STAT3 phosphorylation in mouse and human lung tumor cells. Indeed, our studies showed that Stat3 tyrosine phosphorylation, but not Stat3 protein level, was markedly increased in lung tumors from Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice compared to that in lung tumors from control mice (Fig. 4a). Similar results were also observed in multiple human lung cancer cell lines such as H1299, H2009, H522 and A549, expressing shHDAC7 (Fig. 4b, Additional file 1: Figure S1B). Consistent with the above results, STAT3 phosphorylation was significantly decreased without obvious change of Stat3 protein level when exogenous Hdac7 was expressed in H1299 (Fig. 4c). These results demonstrate that Hdac7 negatively regulates Stat3 phosphorylation (activity) without affecting its protein level in mouse and human lung cancer cells.

Fig. 4.

HDAC7 regulates STAT3 phosphorylation. a. Representative Western blot (left panel) and statistics analyses of the phosphorylation of Stat3 proteins in individual lung tumors isolated from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice. b, Representative Western blot (left panel) and quantitative (right panel) analyses of Stat3 phosphorylation level in H1299 cells expressing shHDAC7 and scramble shRNA. c, HDAC7 overexpression significantly abrogates STAT3 phosphorylation. Representative Western blot analyses of STAT3 phosphorylation level in H1299 cells transfected with pMX-Hdac7 and pMX control plasmids. The values in statistics analyses in (a and b) represent the means ± SD. of three separate experiments. ***, p<0.001

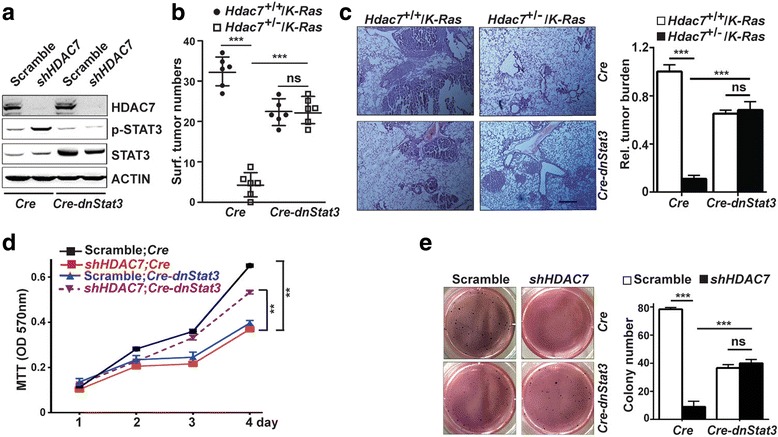

dnStat3 reverses tumor inhibition triggered by Hdac7 mutant in mice

STAT3 constitutive activation is usually associated with tumor promoting [16]. However, high pY-STAT3 was reported to be highly correlated with a better prognosis for some human cancers [19–21] and Stat3 can function as a tumor suppressor in Apc mice [22] and in K-Ras mice [23]. Here we also show that elevated Stat3 phosphorylation is correlated with suppression of lung tumor in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras (Fig. 1c and d). Based on the above information, we hypothesized that Hdac7 mutant inhibits lung tumorigenesis in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice via activating STAT3. To test our hypothesis, we investigated if expression of Stat3 Y705F, a dnStat3, could rescue lung tumor-suppression role of Hdac7 mutant in mice. Two lentiviruses, Lenti-Cre expressing Cre only and Lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 co-expressing Cre and dnStat3, were constructed. We first verified that expression of dnStat3 completely abolished enhanced phosphorylation of Stat3 in Hdac7-depleted H1299 cells infected by Lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 (Fig. 5a, compare lane 4 with lane 2). Then, by tracheal instillation, Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice and control K-Ras mice were infected separately with Lenti-Cre or Lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3, respectively. We found that in the Lenti-Cre infected group, Hdac7 mutant dramatically inhibited lung cancer development, however, in Lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 infected group, neither tumor number on lung surface (Fig. 5b) nor tumor burden (Fig. 5c) were significantly different between Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice and control K-Ras mice. These results demonstrate that lung tumorigenesis is significantly enhanced in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice after enforced expression of dnStat3, that is, that expression of dnStat3 rescues Hdac7-mutant-mediated suppression phenotype of lung tumor in mice. Therefore, we conclude that Hdac7 mutant suppresses lung tumorigenesis in mice by activating Stat3 proteins.

Fig. 5.

dnStat3 reverses Hdac7 mutant –mediated tumor inhibition in mice and partially rescues HDAC7 depletion-mediated growth suppression of human lung cancer cells. a Representative Western blot analysis of the STAT3 protein level and phosphorylation of endogenous STAT3 proteins of shHDAC7 or scramble shRNA-expressing H1299 cells infected with lenti-Cre or lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 viruses, respectively. b Statistical analyses of tumor numbers on lung surfaces of Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice infected with Lenti-Cre or Lenti-Cre-2A-dnStat3 viruses, respectively. Each dot/square represents an individual mouse. c Representative histologic images of H&E stained lung sections (left panels) and statistical analyses (right panel) of tumor burden (right panel) of the same mice in (b). d The growth curves of the same lung cancer cells in (a). MTT assay showed that HDAC7 knockdown-mediated cell growth suppression was partially restored by expressing dnStat3. e. Representative photographs (left panel) and statistical analysis (right panel) of the soft agar colony formation assay for the same lung cancer cells in (a). Values in (b-e) represent the means ± SD of three experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant

dnStat3 rescues growth suppression triggered by HDAC7 depletion in human lung cancer cell lines

To verify if STAT3 also plays a role in human tumor cell growth regulated by HDAC7, we tested whether expression of dnStat3 was able to rescue the growth suppression mediated by HDAC7 depletion in human lung cancer cell lines. Cell proliferation assay showed that Hdac7-depleted H1299 cells grew significantly slower than scrambled H1299 cells when they both were infected with control lentivirus; however, this growth inhibition was recovered or partially recovered (Fig. 5d) when Hdac7-depleted H1299 cells were infected lentivirus expressing dnStat3. We also found that dnStat3 expression also partially restored the capacity of colony formation of H1299 cells in soft agar that was suppressed by HDAC7 depletion (Fig. 5e). These results suggest that HDAC7 may also regulate the growth of human lung cancer cells by inhibiting STAT3 activity.

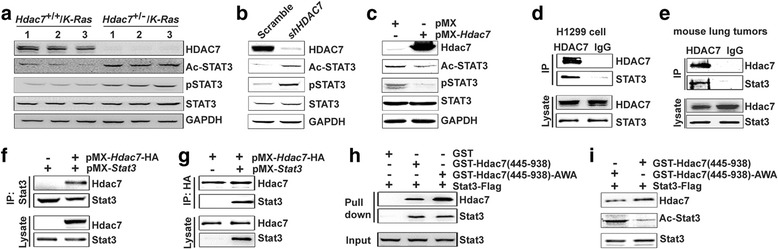

HDAC7 interacts with STAT3 and regulates STAT3 deacetylation

STAT3 phosphorylation is regulated by JAK, Src, PKC kinases [16]. It has been reported that silencing HDAC7 in glioblastoma (GMB) cell U87 enhanced STAT3 phosphorylation by upregulating JAK1 expression [42]. However, our immunoblotting analysis showed that the expression of JAK1, JAK2 and PKC was not significantly altered when HDAC7 expression was depleted in human lung cancer cell line H1299 (Additional file 1: Figure S1C).

STAT3 acetylation can be modulated by histone acetyl transferases/HDACs, e.g. p300/HDAC3, affect its dimerization, DNA binding and transactivation [14]. Also, the STAT3 mutated at key acetylation sites impairs tyrosine-phosphorylation of STAT3 [15]. HDAC7 was reported to repress STAT3 transcriptional activity by forming a complex with histone acetyltransferase Tip60, but there were no provided detailed mechanism(s) [43]. Therefore, we hypothesized that HDAC7 negatively regulates STAT3 activity by deacetylating STAT3. To test our hypothesis, we first evaluated STAT3 acetylation status in both lung tumors from Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice and HDAC7-depleted human lung cancer cell lines. The result revealed that Stat3 acetylation was significantly elevated in Hdac7 +/− mouse lung tumors (Fig. 6a) and HDAC7-depleted H1299 (Fig. 6b) and A549 cells (Additional file 1: Figure S1E). We also found that the STAT3 acetylation was decreased when exogenous Hdac7 was expressed in human cancer cells, H1299 (Fig. 6c) and A549 (Additional file 1: Figure S1F). Next, we examined if Hdac7 and Stat3 proteins interacted each other. Our study showed that not only exogenous Stat3 and Hdac7 proteins expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 6f and g) were co-immunoprecipitated reciprocally, but also endogenous STAT3 and HDAC7 proteins in human lung cancer cells and mouse lung tumors from control K-Ras mice (Fig. 6d and e). This suggests that Hdac7 may directly interact with Stat3 and catalyzes its deacetylation. To further verify this possibility, we performed pull-down assay and in vitro deacetylase assay using affinity purified Flag-tagged Stat3 protein and GST-Hdac7 fusion protein. Since we failed to purify full length GST-HDAC7 fusion proteins and ~500 aa C-terminal domain of HDAC7 has deacetylase activity [44], C-terminal domain (aa 445–938) of mouse Hdac7 protein (NP_062518) was fused to GST and used for the following two experiments. The pull-down assay disclosed that both GST-Hdac7(aa445–938) and GST-Hdac7(aa445–938)-AWA (a mutant Hdac7 lacking of deacetylase activity [45]), but not GST, bound to Stat3 (Fig. 6h). Our in vitro deacetylase assay also showed that purified GST-Hdac7(aa445–938) but not GST-Hdac7(aa445–938)-AWA, dramatically reduced the acetylation of purified Flag-Stat3 (Fig. 6i). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the Hdac7 protein directly interacts with and deacetylates Stat3, which in turn regulates Stat3 phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

HDAC7 interacts and deacetylates STAT3. a-c, HDAC7 regulates STAT3 acetylation. Western blot analysis of acetylation and phosphorylation of STAT3 in the individual lung tumors from Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras and control mice (a), H1299 human cancer cells expressing shHDAC7 (b) and an exogenous mouse Hdac7 cDNA (c) with antibodies specific for Stat3, or acetyl-STAT3(K685) or phospho-Stat3(p-Y705). d-g In vivo interaction of Hdac7 and Stat3 proteins. Immunoprecipitation -Western blots analyses of the endougenous HDAC7 and STAT3 in H1299 human cancer cells (d) and lung tumors from control K-Ras mice (e), and the exogenous mouse Hdac7 and Stat3 proteins expressed in 293 T cells (f and g) with the antibodies as indicated. h GST pull down-Western blot assay of affinity-purified GST-Hdac7 fusion protein and Flag-tagged Stat3 protein. Anti-Hdac7 and -Stat3 were used for blot to detect GST-Hdac7 fusion proteins and Stat3 protein, respectively. i In vitro deacetylase assay with affinity purified GST-HDAC7(aa 445–938), GST-HDAC7(aa 445–938)-AWA and Flag-tagged Stat3 proteins. Acetyl-STAT3 was detected with pan anti-acetyl-Lysine antibodies. Images are representatives of three experiments

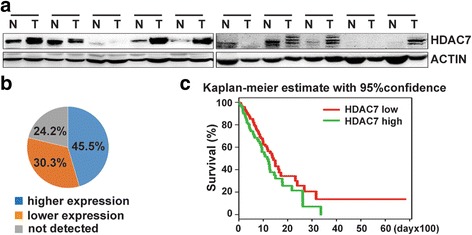

Upregulated HDAC7 expression in human lung cancer correlates with poor prognosis

To further investigate the effects of HDAC7 on human lung cancer, we examined HDAC7 protein level in 33 human lung tumors. HDAC7 expression was upregulated in 15 samples (~45.5%) and down-regulated in 10 samples compared to that in tumor-adjacent tissues, while no HDAC7 protein could be detected in both lung tumors and tumor-adjacent tissue from 8 patients (~24.2%) (Fig. 7a and b). To further gain insight into the role of HDAC7 in human lung cancer, gene expression data of 484 lung cancer patients were collected from TCGA (the Cancer Genome Atlas) for integrated analysis to assess correlation between HDAC7 expression and human lung cancer prognosis. As shown in Fig. 7c, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed low HDAC7 (< median) is a significant good prognosis factor (p < 7.8 × 10−5, X 2 = 15.6, df = 1, Gehan-Wilcoxon test) compared with HDAC7 high expression (> median) in overall patients with HR = 1.46 (95%CI: 1.00–2.13, p = 0.048). Collectively, these results suggest that up-regulation of HDAC7 expression function as an oncogenic factor for human lung cancer development.

Fig. 7.

High expression of HDAC7 in lung cancers correlates with poor patient survival. a and b. The assess of HDAC7 protein expression in human lung cancer tissues. Representative Western blot analyses of HDAC7 protein level in human lung tumor and adjacent tissues (a) and the graph illustration of HDAC7 expression level of 34 human lung cancer tissues (b). N: normal adjacent lung tissue, T: lung tumor tissue. c, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of 484 lung cancer patients with low and high HDAC7 mRNA level in lung cancer tissues (original data from TCGA)

Discussion

Lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [46] due to lack of fully understanding of the molecular mechanisms of lung cancer development. Here we demonstrate that both lung tumor number and burden are dramatically reduced in Hdac7 +/−/K-Ras mice compared with those in control K-Ras mice. We show that HDAC7 silencing inhibits cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of human cancer cell lines. We have also observed higher HDAC7 protein level in ~ 44% human lung tumor samples and found that high HDAC7 mRNA level in human lung cancer is correlated to poor prognosis. All these results from studies of mouse genetics, human lung cancer cell lines and clinic lung cancer patients strongly suggest that HDAC7 play an oncogenic role in human lung cancer, but our conclusion is contradictory to a previous report by Osada, et al., claiming that high HDAC7 mRNA level in human lung tumors was correlated to good progonosis [4]. One possible reason for the discrepancy may come from the different samples size in these two studies. Only 72 human lung cancer samples were analyzed by Osada, et al., while data from 484 lung cancer samples from TCGA were evaluated by this study.

HDAC7 enhances the proliferation of HUVEC and cancer cells such as HeLa, HCT116 and MCF-7 probably by stimulating c-Myc and inhibiting p21 and p27 expression [37, 38]. HDAC7 can also protect mouse thymocytes and cerebellar granule neurons from apoptosis via repressing Nur77 and c-Jun expression, respectively [39, 47]. In contrast, HDAC7 has recently been reported to promote apoptosis of human pro-B-ALL and Burkitt lymphoma by down regulating c-Myc expression [13]. Our study shows that reduction of Hdac7 expression in mice results in a decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of mouse lung cancer cells. However, we only observed enhanced phosphorylation (activation) of Stat3 proteins but no obvious alteration at protein levels for Stat3, c-Myc, c-Jun, p21 and p53 (Additional file 1: Figure S1A). All these results suggest that HDAC7 may regulate the proliferation and apoptosis of various cells through different molecular mechanisms.

During the period of preparing this manuscript, Peixoto, et al. reported that HDAC7 high expression in glioblastoma (GBM) is associated with poor prognosis. They have also demonstrated that HDAC7 silencing suppressed the tumor growth of GBM cell U87 in vivo mainly by inhibiting angiogenesis because HDAC7 depletion had no effect on the proliferation of GBM cell U87 in vitro [42]. Mechanistically, they also showed that HDAC7-depletion inhibited angiogenesis by activating the expression of JAK1 and AKAP12, both of which can synergistically sustain the activity of STAT3 by inducing its phosphorylation (JAK1 tyrosine kinase) and protein expression (AKAP12) [42]. Here we show that mouse Hdac7 mutation suppresses lung tumor development in vivo and HDAC7 silencing in human lung cancer cell lines inhibits their proliferation in vitro. Mechanistically, we have demonstrated Hdac7 can directly interact with Stat3 and deacetylate Stat3 proteins, and decreasing Hdac7 expression by mutation in mice or shRNA in human lung cancer cells results in enhanced acetylation and phosphorylation of Stat3 without significant effect on the expression of JAK1 and AKAP12 (Additional file 1: Figure S1B). Furthermore, STAT3 acetylation but not tyrosine phosphorylation has been shown to be required to silence expression of many tumor suppressor genes such as SHP-1, CDKN2A by recruiting DNMT1 to methylate their promoter in cancer cells [48–50]. Therefore, although HDAC7-mediated angiogenesis may also play a role in lung tumor development, we think that reducing Hdac7 expression is an important and sufficient factor to suppress lung tumorigenesis by inhibiting proliferation and enhancing apoptosis of tumor cells in mice, and probably in humans. This notion is supported by our observation that the expressions of cyclin D and cyclin E were significantly decreased in both lung tumors from Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice (Additional file 1: Figure S1A) and HDAC7-depleted human lung cancer cell line H1299 (Additional file 1: Figure S1D). This notion is also further supported by recent findings that HDAC7 expression is necessary to maintain breast and ovarian cancer stem cells in human and over-expression of HDAC7 is sufficient to augment the CSC phenotype [11].

Both positive and negative associations between STAT3 activation and survival of lug cancer patients or lung tumor progression have been reported [23, 26, 27]. Furthermore, Zhou, et al., have recently shown that deletion of Stat3 in K-Ras mice enhanced lung tumor number but reduced lung tumor volume, suggesting that Stat3 can function as a tumor suppressor and an oncogene at different stages of lung tumor development [28]. Their study also showed that cell proliferation and Cyclin D expression were decreased in the tumors from their Stat3 −/− /K-Ras mice in which Stat3 was deleted. These results only provided cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying Stat3 as an oncogene and failed to illustrate the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying Stat3 as a tumor suppressor. Here, our study results show that tumor number, tumor burden (Fig. 1c and d), and tumor size (unpublished data) were all decreased in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice. Our study supports the notion that Stat3 function as a tumor suppressor, but do not back the notion that Stat3 can also function as oncogene in lung tumor development because our results revealed that cell proliferation, Cyclin D and cyclin E expression were all decreased when Stat3 was more activated (Y705 phosphorylation) in the tumors from our Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice. Nevertheless, these two studies suggest that Stat3 may function as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer under different genetic scenarios.

STAT3β, lacking a transcriptional activation domain at its C-terminal, is a product of differential splicing form of STAT3 gene and displays a dominant negative function for the STAT3 [51]. Zhang, et al., have shown that high STAT3β expression correlated with a favorable prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Expression of STAT3β substantially increased the Y705-phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding/promoter occupation of STAT3, but the transcriptional activity of STAT3 decreased by STAT3β [52]. Here, we have not only shown that tumorigenesis was inhibited in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice and Stat3 was more activated (more phosphorylation of Y705) in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras tumors, but we also demonstrated that suppression of endogenous Stat3 activity in lung tumor cells, by expressing dnStat3, reversed Hdac7 mutant-mediated reduction of tumor number and burden in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice. These results rule out the possibility that reduced tumorigenesis in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice is due to increase expression of Stat3β because, if that is the case, expressing dnStat3 should result in further reduction rather than enhanced tumorigenesis in Hdac7 +/− /K-Ras mice.

The catalytic activity of class IIa HDACs (including HDAC4, −5, −7 and −9) was initially attributed to the presence of class I HDACs co-purified along with the class IIa HDACs. Later, the catalytic domains of HDAC4 and HDAC7 purified from E. coli that lacks histones and endogenous HDACs were demonstrated to have a low but measurable deacetylase activity on acetylated-lysine of histones [53, 54] and a high deacetylase activity on trifluoroacetyl lysine, a class IIa-specific substrates in vitro [53–55]. One of possible reasons proposed to explain the low catalytic activity of class IIa HDACs is that acetylated-lysine of histones is not a biological substrate for class IIa HDACs [54]. Now we demonstrate that loss of Hdac7 resulted in significantly enhanced Stat3 acetylation in both mouse primary tumors and human tumor cell lines. Our co-immunoprecitaion and pull down assay also show that HDAC7 protein directly interacts with Stat3 and the HDAC7 catalytic domain with AWA mutations failed to deacetylate Stat3 in the in vitro deacetylase assay. All these data suggest that the Stat3 protein may be a biological substrate for class IIa deacetylase HDAC7. However, the possibility that contribution of contamination of class I deacetylases such as HDAC3 cannot be ruled out completely since the HDAC7 catalytic domain used for our in vitro deacetylase assay was purified from mammalian 293T cells. Further experiments using HDAC7 purified from E.coli and/or class I-selective HDAC inhibitors will help to solve whether Stat3 is a biological substrate for class IIa deacetylase HDAC7.

Conclusion

Our studies demonstrate that HDAC7 functions as a tumor promoting factor by deacetylating STAT3, therefore reducing STAT3 activation. This furthers our understanding of lung cancer development and may provide a theoretical base for developing new therapeutic strategies for human lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Xinyuan Fu (Singapo National University, Singapo), Seok-Yong Choi (Chonnam National University Medical School, Republic of Korea) and Hung-Ying Kao (Case Western Reserve University, USA) for providing plasmids pMX-Stat3, pMX-dnStat3, pCS4-2A, pCMX-FLAG-mHdac7 and pCMX-FLAG-mHdac7 (AWA), respectively. We also thank Xiaofeng Tao for English editting.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1000504); National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB945304, 2011CB510102); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671330, 31471380); Open research fund of State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering Fudan University (SKLGE-1402).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (http://cancergenome.nih.gov).

Abbreviations

- AKAP12

A-kinase anchor protein 12

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HDAC7

Histone deacetylases 7

- JAK1

Janus kinase 1

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- K-Ras

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide

- PB

PiggyBac

- PFU

Plaque-forming units

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- Tip60

Tat interactive protein 60 kDa

- TU

Transforming unit

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Additional file

The effects of Hdac7 on the expression and post-translational modifications of other signaling molecules. A. Western blot and quantitative analyses of c-Jun, c-Myc, P21, P53, Cyclin D and Cyclin E proteins in lung tumors from the Hdac7+/−; K-Ras and control mice. B. Western blot and quantitative analyses of JAK1, JAK2, PKC-a and AKAP12 proteins in H1299 human lung cancer cells expressing shHDAC7. C. Western blot analysis of STAT3 phosphorylation in human lung cancer cells, A549, H2009 and H522 expressing shHDAC7. D. Representative immunoblot analysis of Cyclin D and Cyclin E in HDAC7 silencing H1299 cells. E and F. IP-Western blot analysis of STAT3 acetylation in A549 lung cancer cells expressing shHDAC7 (E) or exogenous Hdac7 with indicated antibodies (F). Ac-lysine: a pan anti-acetyl-Lysine antibodies. Images are representatives of three experiments. Values in A and B represent the means ± S.E of three experiments. **, p < 0.01 ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. (PDF 880 kb)

Authors’ contributions

YL and WT designed research, YL, LL, SZ, YF and XL performed research and collected data, BS and XC provided important human tissue samples, YL, SG, CW, HK, and WT analyzed and interpreted data, YL, SG, XC, HK and WT wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Use of mice was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Developmental Biology and Molecular Medicine at Fudan University, Shanghai, China. Clinical lung cancer samples were obtained from Huashan, Fudan University, with consents from the patients and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12943-017-0736-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xiaofeng Chen, Email: cxf3166@126.com.

Hengning Ke, Email: 15729577635@163.com.

Wufan Tao, Email: wufan_tao@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Li Y, Seto E. HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in cancer development and therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026831. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witt O, Deubzer HE, Milde T, Oehme I. HDAC family: what are the cancer relevant targets? Cancer Lett. 2009;277:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ropero S, Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Hamelin R, Yamamoto H, Boix-Chornet M, Caballero R, Alaminos M, Setien F, Paz MF. A truncating mutation of HDAC2 in human cancers confers resistance to histone deacetylase inhibition. Nat Genet. 2006;38:566–569. doi: 10.1038/ng1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Saito H, Yatabe Y, Mitsudomi T, Takahashi T. Reduced expression of class II histone deacetylase genes is associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:26–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin Z, Jiang W, Jiao F, Guo Z, Hu H, Wang L, Wang L. Decreased expression of histone deacetylase 10 predicts poor prognosis of gastric cancer patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5872–5879. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann S, Kiefer F, Prudenziati M, Spiller C, Hansen J, Floss T, Wurst W, Minucci S, Göttlicher M. Reduced body size and decreased intestinal tumor rates in HDAC2-mutant mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9047–9054. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhaskara S, Knutson SK, Jiang G, Chandrasekharan MB, Wilson AJ, Zheng S, Yenamandra A, Locke K, Yuan J-l, Bonine-Summers AR. Hdac3 is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santoro F, Botrugno OA, Dal Zuffo R, Pallavicini I, Matthews GM, Cluse L, Barozzi I, Senese S, Fornasari L, Moretti S. A dual role for Hdac1: oncosuppressor in tumorigenesis, oncogene in tumor maintenance. Blood. 2013;121:3459–3468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-461988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang S, Young BD, Li S, Qi X, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Histone deacetylase 7 maintains vascular integrity by repressing matrix metalloproteinase 10. Cell. 2006;126:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouaissi M, Sielezneff I, Silvestre R, Sastre B, Bernard JP, Lafontaine JS, Payan MJ, Dahan L, Pirro N, Seitz JF, et al. High histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7) expression is significantly associated with adenocarcinomas of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2318–2328. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9940-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt AE, Lee CW, Lee TI, Azzam DJ, Wang B, Caslini C, Petrocca F, Grosso J, Jones M, Cohick EB, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell-specific function for the histone deacetylases, HDAC1 and HDAC7, in breast and ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2016;36:1707–20. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno DA, Scrideli CA, Cortez MA, de Paula Queiroz R, Valera ET, da Silva Silveira V, Yunes JA, Brandalise SR, Tone LG. Differential expression of HDAC3, HDAC7 and HDAC9 is associated with prognosis and survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:665–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barneda-Zahonero B, Collazo O, Azagra A, Fernández-Duran I, Serra-Musach J, Islam A, Vega-García N, Malatesta R, Camós M, Gómez A. The transcriptional repressor HDAC7 promotes apoptosis and c-Myc downregulation in particular types of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1635. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan Z-l, Guan Y-j, Chatterjee D, Chin YE. Stat3 dimerization regulated by reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue. Science. 2005;307:269–273. doi: 10.1126/science.1105166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie Y, Erion DM, Yuan Z, Dietrich M, Shulman GI, Horvath TL, Gao Q. STAT3 inhibition of gluconeogenesis is downregulated by SirT1. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:492–500. doi: 10.1038/ncb1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gkouveris I, Nikitakis N, Sauk J. STAT3 signaling in cancer. J Cancer Ther. 2015;06:709–726. doi: 10.4236/jct.2015.68078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couto JP, Daly L, Almeida A, Knauf JA, Fagin JA, Sobrinho-Simoes M, Lima J, Maximo V, Soares P, Lyden D, Bromberg JF. STAT3 negatively regulates thyroid tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2361–E2370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201232109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim WG, Choi HJ, Kim WB, Kim EY, Yim JH, Kim TY, Gong G, Kim SY, Chung N, Shong YK. Basal STAT3 activities are negatively correlated with tumor size in papillary thyroid carcinomas. J Endocrinol Investig. 2012;35:413–418. doi: 10.3275/7907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Setsu N, Kohashi K, Endo M, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Takahashi Y, Yamada Y, Ishii T, Matsuda S, Yokoyama R. Phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma is associated with a better prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:109–115. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordziel C, Bratsch J, Moriggl R, Knosel T, Friedrich K. Both STAT1 and STAT3 are favourable prognostic determinants in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:138–146. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiao JR, Jin YT, Tsai ST, Shiau AL, Wu CL, Su WC. Constitutive activation of STAT3 and STAT5 is present in the majority of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and correlates with better prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:344–349. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musteanu M, Blaas L, Mair M, Schlederer M, Bilban M, Tauber S, Esterbauer H, Mueller M, Casanova E, Kenner L, et al. Stat3 is a negative regulator of intestinal tumor progression in Apc(min) mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1003–1011. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabner B, Schramek D, Mueller KM, Moll HP, Svinka J, Hoffmann T, Bauer E, Blaas L, Hruschka N, Zboray K, et al. Disruption of STAT3 signalling promotes KRAS-induced lung tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6285. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Iglesia N, Konopka G, Puram SV, Chan JA, Bachoo RM, You MJ, Levy DE, Depinho RA, Bonni A. Identification of a PTEN-regulated STAT3 brain tumor suppressor pathway. Genes Dev. 2008;22:449–462. doi: 10.1101/gad.1606508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Du H, Qin Y, Roberts J, Cummings OW, Yan C. Activation of the signal transducers and activators of the transcription 3 pathway in alveolar epithelial cells induces inflammation and adenocarcinomas in mouse lung. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8494–8503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang R, Jin Z, Liu Z, Sun L, Wang L, Li K. Correlation of activated STAT3 expression with clinicopathologic features in lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Diagn Ther. 2011;15:347–352. doi: 10.1007/BF03256470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mostertz W, Stevenson M, Acharya C, Chan I, Walters K, Lamlertthon W, Barry W, Crawford J, Nevins J, Potti A. Age-and sex-specific genomic profiles in non–small cell lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:535–543. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Qu Z, Yan S, Sun F, Whitsett JA, Shapiro SD, Xiao G. Differential roles of STAT3 in the initiation and growth of lung cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:3804. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, Jacks T, Tuveson DA. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Du X, Shi H, Deng K, Chi H, Tao W. Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) enhances the stability of forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) and the function of regulatory T cells by modulating Foxp3 Acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:30762–30770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.668442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanegae Y, Makimura M, Saito I. A simple and efficient method for purification of infectious recombinant adenovirus. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1994;47:157–166. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.47.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutner RH, Zhang X-Y, Reiser J. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:495–505. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Pei J, Xia H, Ke H, Wang H, Tao W. Lats2, a putative tumor suppressor, inhibits G1/S transition. Oncogene. 2003;22:4398–4405. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu DS-S, Wang H-J, Tai S-K, Chou C-H, Hsieh C-H, Chiu P-H, Chen N-J, Yang M-H. Acetylation of snail modulates the cytokinome of cancer cells to enhance the recruitment of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:534–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Margariti A, Zampetaki A, Xiao Q, Zhou B, Karamariti E, Martin D, Yin X, Mayr M, Li H, Zhang Z. Histone deacetylase 7 controls endothelial cell growth through modulation of β-catenin. Circ Res. 2010;106:1202–1211. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Li X, Parra M, Verdin E, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Control of endothelial cell proliferation and migration by VEGF signaling to histone deacetylase 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7738–7743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802857105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu C, Chen Q, Xie Z, Ai J, Tong L, Ding J, Geng M. The role of histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7) in cancer cell proliferation: regulation on c-Myc. J Mol Med. 2011;89:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma C, D'Mello SR. Neuroprotection by histone deacetylase-7 (HDAC7) occurs by inhibition of c-jun expression through a deacetylase-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4819–4828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dequiedt F, Kasler H, Fischle W, Kiermer V, Weinstein M, Herndier BG, Verdin E. HDAC7, a thymus-specific class II histone deacetylase, regulates Nur77 transcription and TCR-mediated apoptosis. Immunity. 2003;18:687–698. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turtoi A, Mottet D, Matheus N, Dumont B, Peixoto P, Hennequière V, Deroanne C, Colige A, De Pauw E, Bellahcene A. The angiogenesis suppressor gene AKAP12 is under the epigenetic control of HDAC7 in endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2012;15:543–554. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peixoto P, Blomme A, Costanza B, Ronca R, Rezzola S, Palacios AP, Schoysman L, Boutry S, Goffart N, Peulen O, et al. HDAC7 inhibition resets STAT3 tumorigenic activity in human glioblastoma independently of EGFR and PTEN: new opportunities for selected targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2016;35:4481–4494. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao H, Chung J, Kao HY, Yang YC. Tip60 is a co-repressor for STAT3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11197–11204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kao H-Y, Downes M, Ordentlich P, Evans RM. Isolation of a novel histone deacetylase reveals that class I and class II deacetylases promote SMRT-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:55–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Downes M, Ordentlich P, Kao HY, Alvarez JG, Evans RM. Identification of a nuclear domain with deacetylase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parra M, Mahmoudi T, Verdin E. Myosin phosphatase dephosphorylates HDAC7, controls its nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, and inhibits apoptosis in thymocytes. Genes Dev. 2007;21:638–643. doi: 10.1101/gad.1513107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee H, Zhang P, Herrmann A, Yang C, Xin H, Wang Z, Hoon DS, Forman SJ, Jove R, Riggs AD, Yu H. Acetylated STAT3 is crucial for methylation of tumor-suppressor gene promoters and inhibition by resveratrol results in demethylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7765–7769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205132109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Cui G, Sun L, Wang SJ, Li YL, Meng YG, Guan Z, Fan WS, Li LA, Yang YZ, et al. STAT3 acetylation-induced promoter methylation is associated with downregulation of the ARHI tumor-suppressor gene in ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:165–170. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Wang HY, Marzec M, Raghunath PN, Nagasawa T, Wasik MA. STAT3- and DNA methyltransferase 1-mediated epigenetic silencing of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase tumor suppressor gene in malignant T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6948–6953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501959102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caldenhoven E, van Dijk TB, Solari R, Armstrong J, Raaijmakers JA, Lammers J-WJ, Koenderman L, de Groot RP. STAT3β, a splice variant of transcription factor STAT3, is a dominant negative regulator of transcription. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13221–13227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H-F, Chen Y, Wu C, Wu Z-Y, Tweardy DJ, Alshareef A, Liao L-D, Xue Y-J, Wu J-Y, Chen B. The opposing function of STAT3 as an oncoprotein and tumor suppressor is dictated by the expression status of STAT3β in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:691–703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lahm A, Paolini C, Pallaoro M, Nardi MC, Jones P, Neddermann P, Sambucini S, Bottomley MJ, Surdo PL, Carfí A. Unraveling the hidden catalytic activity of vertebrate class IIa histone deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17335–17340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706487104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuetz A, Min J, Allalihassani A, Schapira M, Shuen M, Loppnau P, Mazitschek R, Kwiatkowski NP, Lewis TA, Maglathin RL. Human HDAC7 harbors a class IIa Histone Deacetylase-specific zinc binding motif and cryptic Deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11355–11363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones P, Altamura S, De FR, Gallinari P, Lahm A, Neddermann P, Rowley M, Serafini S, Steinkühler C. Probing the elusive catalytic activity of vertebrate class IIa histone deacetylases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1814–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (http://cancergenome.nih.gov).