Abstract

Intestine barrier disruption and bacterial translocation can contribute to sepsis and multiple organ failure- leading causes of mortality in burn-injured patients. Additionally, findings suggest ethanol (alcohol) intoxication at the time of injury worsens symptoms associated with burn injury. We have previously shown that interleukin-22 (IL-22) protects from intestinal leakiness and prevents overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria following ethanol and burn injury, but how IL-22 mediates these effects has not been established. Here, utilizing a model of ethanol and burn injury, we show that the combined insult results in a significant loss of proliferating cells within small intestine crypts and increases Enterobacteriaceae copies, despite elevated levels of the anti-microbial peptide (AMPs) lipocalin-2. IL-22 administration restored numbers of proliferating cells within crypts, significantly increased Reg3β, Reg3γ, lipocalin-2 AMP transcript levels in intestine epithelial cells, and resulted in complete reduction of Enterobacteriaceae in the small intestine. Knockout of signal transducer and activator of transcription factor-3 (STAT3) in intestine epithelial cells resulted in complete loss of IL-22 protection, demonstrating STAT3 is required for intestine barrier protection following ethanol combined with injury. Together, these findings suggest IL-22/STAT3 signaling is critical to gut barrier integrity and targeting this pathway may be of beneficial clinical relevance following burn injury.

Keywords: Alcohol, Ethanol, Burn, Antimicrobial peptide, Epithelial Cells, STAT3

Introduction

Trauma, including burn injury, has been shown to result in gut barrier disruption and bacterial translocation(1-3), which can cause systemic inflammation (4), sepsis (3), and multiple organ failure (2, 5). Co-morbidities including ethanol intoxication at the time of trauma, negatively impact patient prognosis and recovery. Studies have demonstrated that approximately half of patients admitted to burn units have detectable blood ethanol levels, and that these patients exhibit higher rates of infection and greater incidence of mortality (6, 7). We have shown that ethanol intoxication exacerbates the suppression of intestinal T cells and potentiates small bowel barrier disruption, and increases Gram-negative bacterial overgrowth within one day after burn injury (8, 9). More recently, we have discovered changes to the microbiome in our rodent model of burn injury directly reflect the changes observed to the microbiome of hospitalized burn patients (10). Microbial dysbiosis and gut leakiness may represent significant confounding factors to post-burn pathogenesis.

Interleukin-22 (IL-22) can protect the intestinal barrier through promoting epithelial cell proliferation and anti-microbial peptide (AMP) secretion through the Janus kinase (Jak)/STAT pathways (11). The AMPs regenerating islet-derived protein 3 (Reg3b/Reg3g) and lipocalin-2 are produced by epithelial cells in the intestine, and are key to maintaining intestinal homeostasis (12). Reg3 peptides are bactericidal against Gram-positive species by binding to peptidoglycan on the bacterial cell surface, and Gram-negative bacteria by permeabilizing the outer membrane (PLoS PAPER). Lipocalin-2 possesses bacteriostatic activity through iron sequestration (12).

We have previously shown a significant reduction in IL-22 production from T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissues following the combined injury (9). Restorative treatment with IL-22 following ethanol and burn injury resulted in substantially reduced gut barrier leakiness, and mitigated Gram-negative bacterial overgrowth (8). While IL-22 was protective following the combined insult, the mechanism of this protection remains unknown.

We hypothesized that IL-22 would protect the small intestine from microbial dysbiosis and epithelial barrier disruption via STAT3 signaling in intestine epithelial cells following the combined insult. Wild-type and VillinCre STAT3-/- knockout mice displayed similar increases of Enterobacteriaceae and reduction in the number of proliferating intestinal epithelial cells within the small intestine crypts following ethanol and burn injury. Administration of IL-22 mitigated the increase in Enterobacteriaceae, and restored intestine epithelial cell proliferation in wild-type animals in a STAT3-dependent fashion. Together, these findings support the suggestion that IL-22 is protective to the intestine, and that STAT3 signaling may be a relevant pathway to target for clinical therapies to protect the intestinal epithelial barrier and microbiome following injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male 10-12 week old (∼23-25g body weight) C57BL/6 (wildtype) mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Intestine epithelial cell specific VillinCre STAT3flox/flox knockout (henceforth referred to as “STAT3-/-“) mice were obtained from Dr. Bin Gao at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and were re-derived at Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). STAT3-/- genotype was verified upon arrival at Loyola University Health Sciences Division. Mice were housed at Loyola University Chicago Health Science Division, Maywood, IL, USA, and all experiments and procedures were carried out in adherence to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Loyola University Chicago Health Sciences Division Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ethanol/Burn Injury and IL-22 Treatment

Mice were subjected to ethanol and burn injury as described previously (13). Briefly, mice were randomly separated into six different experimental groups: sham vehicle, sham ethanol, burn vehicle, burn ethanol, sham + IL-22, burn ethanol + IL-22. As shown in Fig. 1A, mice received 400 μl of 25% ethanol (∼2.9g/kg) or vehicle (water) by oral gavage. Four hours following gavage when blood ethanol was approximately ∼100mg/dL, mice were anesthetized with ∼80 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride and ∼1.2 mg/kg xylazine, and their dorsum was shaved. Mice were then placed in a pre-fabricated template to expose ∼12.5% of their total body surface area. Mice receiving burn injury were submersed in 85-90°C water for 7 seconds, resulting in a histologically proven full-thickness burn. Peripheral nerves endings are destroyed by this injury (14). Mice were then immediately given a 1mL intraperitoneal normal saline resuscitation injection with or without 1mg/kg recombinant mouse IL-22 (GenScript, Piscataway Township, NJ). Mice were returned to their cages and allowed food and water ad libitum, and were euthanized by isoflurane overdose one day following the ethanol gavage.

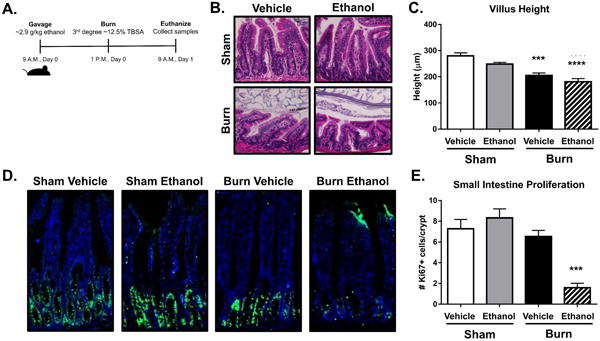

Figure 1. Ethanol and burn injury damages intestine morphology and reduces proliferation.

Schematic of the combined ethanol and burn injury model (A). H&E staining of distal ileum sections from four experimental groups (B) and the respective villus height measurements (C). Analysis of proliferation within small intestine crypts using Ki-67 staining (D) and quantification represented as the number of Ki-67+ cells per crypt, (E). n = 3-8 animals per group, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to sham vehicle.

Tissue Staining and Immunofluorescence

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, sections of ileum were saved in 10% formalin. Tissues were processed, sectioned, and stained by the Loyola University Health Science Division Tissue Processing Core. Ki-67 stainings were performed on tissues frozen in optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) medium. 5μm sections were obtained on a Cryostar NX50 Cryosectioner (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and mounted on glass slides. Ki-67 antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and Alexa-488 conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. Tissues were counterstained using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to visualize nuclei. Images were obtained on a Zeiss Axiovert 200m microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 200× total magnification. Brightness and contrast of images were adjusted using Photoshop CS3. Villus height was measured using Axiovision software (Zeiss). Intestinal epithelial cell proliferation was quantified by counting the number of Ki-67 positive staining cells per crypt in ileum tissue. Tissue sections were blinded and a minimum of 3 randomly obtained images at 200× magnification per animal were counted, and are represented as number of Ki-67 positive cells/crypt. Data presented are the average of two independent experiments.

Fluorescent in situ Hybridization (FISH)

Small intestine sections were taken from the ileocecal wall and fixed in 10% formalin. Paraffin blocks and slides with 5μm sections were prepared by the Loyola University Health Science Division Tissue Processing Core. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization was performed as described previously with small adjustments (15). Slides were deparaffinized, dried for 25 minutes at 50°C, and then incubated with the indicated probes at a final concentration of 1ng/μl in hybridization buffer (0.9M NaCl, 20mMTris-HCL, pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS) overnight at 50°C in a humidified slide box. Probe sequences were as follows(10): Universal bacterial probe EUB338: Alexa 555 5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT -3′

Enterobacteriaceae probe

ENTBAC 183: Alexa 488 5′-CTCTTTGGTCTTGCGACG -3′ (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following incubation, slides were washed 3 × 15′ in pre-warmed hybridization buffer from above at 50°C, air dried at room temperature, and mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 5 independent images were taken from a minimum of three animals per group. Sections were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200m microscope and processed using Axiovision software (Zeiss).

Quantitative Analyses of Fecal Microbiome

Real-time PCR was used to quantify bacterial ribosomal small subunit (SSU) 16S rRNA gene abundance, as described previously (10). Primers targeting SSU rRNA genes of microorganisms at the domain level (Bacteria) and at the family level (Enterobacteriaceae) were used. Primers included 340F: (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT) and 514R: (ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC) for domain-level analyses and 515F: (GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA) and 826R: (GCCTCAAGGGCACAACCTCCAAG) for Enterobacteriaceae analyses (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 10-fold dilution standards were made from purified genomic DNA from reference bacteria (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and run in triplicate. All reactions were run using SYBR green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 95°C for 3′, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15” and a 63°C (Bacteria) or 67°C (Enterobacteriaceae) for 60” using a Step One Plus Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Intestinal Epithelial Cell Isolation

Intestinal epithelial cells were isolated from the small intestine as described previously (16). Briefly, the distal 10cm of the small intestine was removed, opened longitudinally, and placed in ice cold PBS. Epithelial cells were then disrupted from the tissue by vigorous shaking in a digestion solution containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% HEPES, 1% pen/strep, 0.5% gentamicin, 5mM EDTA, and 1mM dithiothreitol (D.T.T.) in 1× Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) at 37°C.

Real-time PCR Gene Analysis

Anti-microbial peptide transcript levels were measured using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay. Briefly, RNA was isolated from intestinal epithelial cells using a Qigaen RNEasy Kit per the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription was performed using a High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), and real-time PCR were performed per manufacturer's instructions. Primers for Reg3β, Reg3γ, lipocalin-2, and β-actin were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

ELISA

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes. Serum was separated from red blood cells by centrifugation. IL-22 ELISA (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and IL-22BP ELISA (LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA) were performed per the manufacturer's instructions. Lipocalin-2 ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was performed on protein isolated from small intestine epithelial cells per the manufacturer's instructions. For lung and liver ELISAs, total tissues were collected and homogenized in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) containing protease inhibitor (Cell Signaling Technology) and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher). Tissues were then analyzed for IL-6 (R&D Systems) and KC (R&D Systems) by ELISA. Data are expressed as the amount of cytokine per milligram of protein homogenate loaded on the plate.

Flow Cytometry

Isolated small intestine epithelial cells were stained using antibodies towards cytokeratin-FITC (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom ab78478) and mouse IL-22 receptor-APC (R&D Systems, FAB42941A). Cells were then run on a CantoII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and subsequently analyzed using FlowJo Software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Statistics

Data from sham vehicle and ethanol + burn animals from independent experiments were combined and presented as the averages of those experiments. Comparisons were analyzed using a One-Way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test. All analysis was done using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Mice from Sham Vehicle and Ethanol Burn groups were combined from all experiments to increase sample size and minimize error, these are denoted in the figure legends. A confidence level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance is represented throughout the manuscript as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Results

We first examined the effects of ethanol, burn, and the combined insult on small intestine morphology. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of distal small intestine sections (Fig. 1B) showed a significant amount of villus blunting (widening), and villus height shortening one day following both burn alone and the combined injury compared to sham vehicle mice (Fig. 1C), which supports our previous findings in rats (17). We next wanted to quantify the proliferative capacity of epithelial cells within the small intestine to see if barrier regeneration was hindered. Immunofluorescent staining using Ki-67 showed significant decreases in the number of actively proliferating cells within the crypts of the small intestine following alcohol and burn injury compared to either alcohol or burn injury alone (Fig. 1D-E). These data collectively demonstrate that burn injury results in a significant loss to villus morphology and IEC proliferative capacity, which is worsened in the presence of ethanol.

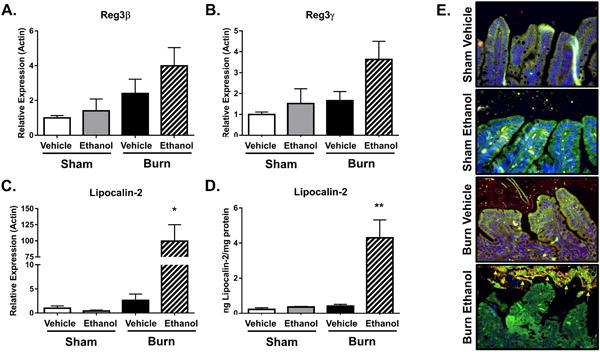

Previous data from our laboratory has demonstrated that there is a significant increase in both total bacteria and Enterobacteriaceae in the small intestine luminal content following the combined ethanol and burn injury (18). Therefore, we sought to quantify the ability of small intestine epithelial cells to produce anti-microbial peptides following the combined injury. While there were no significant differences between groups in Reg3β or Reg3γ transcript expression, lipocalin-2 transcripts were increased following the combined injury compared to sham animals (Fig. 2A-C). We chose to focus on lipocalin-2 protein expression, as lipocalin-2 has been shown to preferentially target the Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae family by sequestering iron required for bacterial growth(19). Lipocalin-2 protein levels in small intestine tissue were also significantly elevated compared to all other groups (Fig. 2D). Finally, we performed fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using probes targeting specific regions of the 16S ribosomal gene in order to visualize the proximity of total bacteria (red labeled probe) and Enterobacteriaceae (green labeled probe) to intestinal villi following the injury. Bacterial proximity to intestinal villi is one subjective way to correlate the ability of bacteria and endotoxins to cross the intestinal epithelial barrier into systemic or lymphatic circulation. We observed large populations of Enterobacteriaceae (yellow arrows) in close proximity to the villi in the small intestines of mice receiving the combined insult compared to all other experimental groups (Fig. 2E). These observations suggest that even in the presence of elevated anti-microbial peptide production from epithelial cells, Enterobacteriaceae are still able to preferentially colonize.

Figure 2. Combined injury results in overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae despite increased epithelial cell AMPs.

Real-time PCR analysis of AMP transcripts for Reg3β, Reg3γ, and lipocalin-2 following the combined injury, sham (A-C). Lipocalin-2 ELISA from total small intestine tissue (D), n = 3-11 animals per group. Specific fluorescent probes were used to perform FISH staining on total bacteria (red labeled probe) and Enterobacteriaceae (green labeled probe) on sections from distal ileum (E). Enterobacteriaceae appear yellow (arrows) due to the overlap of total bacteria (red) and Enterobacteriaceae (green) probes. FISH staining from one representative experiment, n = 3-6, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to all groups.

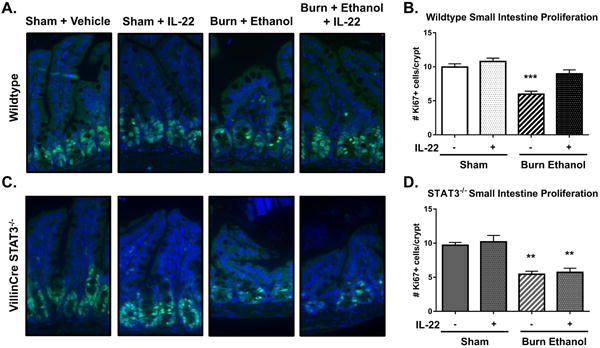

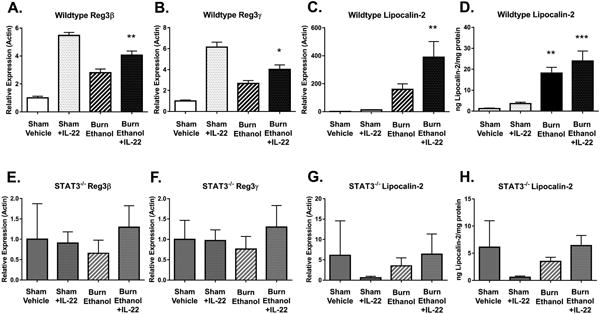

We have previously established that IL-22 production from T cells in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is significantly reduced following the combined injury(9). In addition, administration of recombinant IL-22 was shown to reduce intestine leakiness, suggesting that IL-22 may be beneficial following acute injury(8). We hypothesized that we could restore proliferation and further promote an anti-microbial defense by administering recombinant IL-22 at the time of resuscitation. Data in Figure 3 A-B show that treatment of mice with a single dose of IL-22 resulted in near complete restoration of the number of Ki67-positive cells within the crypts of the small intestine following the combined insult of ethanol and burn injury. Additionally, IL-22 further increased the expression of Reg3β, Reg3γ, and lipocalin-2 transcripts, and lipocalin-2 protein in the small intestine epithelial cells compared to mice receiving only saline resuscitation (Fig 4A-D).

Figure 3. IL-22 mediated restoration of proliferation is dependent on STAT3 in intestine epithelial cells.

Ki-67 staining on distal ileum sections of wildtype (n = 7-13), ***p < 0.001 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to all groups, and VillinCre STAT3-/- knockout (n = 3-5) **p < 0.01 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to sham groups. Wildtype data are expressed as the mean of two independent experiments. Quantification was blinded and expressed as the number of Ki-67+ proliferating cells per crypt.

Figure 4. IL-22 treatment further increases AMP production via STAT3 signaling.

Real-time PCR analysis of anti-microbial peptide gene expression following injury and IL-22 treatment. RNA from ileum epithelial cells was analyzed for expression of (A, E) Reg3β, (B, F) Reg3γ, (C,G) lipocalin-2 transcripts and (D,H) lipocalin protein in wild-type mice, (n=4-10) (A-D) and VillinCre STAT3-/- knockout mice, sham vehicle (n =3-8) (E-H). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to untreated sham vehicle.

To further delineate the mechanism underlying IL-22 mediated protection of the intestine barrier, we used intestine epithelial cell specific STAT3-/- knockout mice. STAT3 has been shown to mediate the beneficial effects of IL-22 in other models of chronic inflammatory conditions such IBD(20). To determine if IL-22 was mediating acute protective effects through STAT3, we administered IL-22 in STAT3 deficient mice and assessed the proliferative capacity and AMP production from small intestine epithelial cells. IL-22 administration to STAT3-/- mice did not rescue the proliferation of epithelial cells within the crypts of the small intestine following the combined injury (Fig. 3 C-D). Additionally, STAT3-/- mice were unable to generate any anti-microbial peptide response following injury, or treatment with IL-22 relative to wildtype mice (Fig. 4 E-H). These data together demonstrate that exogenously administered IL-22 utilizes STAT3 in intestinal epithelial cells to promote both barrier regeneration and anti-microbial peptide production following acute injury.

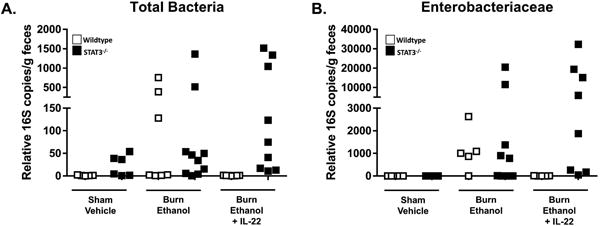

We sought to determine if IL-22 and STAT3 signaling plays any role in the maintenance of intestinal microbiome following ethanol and burn injury. We performed quantitative real-time PCR on 16S ribosomal RNA of both total bacteria and Enterobacteriaceae on small intestine lumenal content. Animals were housed in the same room and fed the same diet for a minimum of two weeks before beginning experiments to assimilate microbial exposure. Our results showed very large increases in both total bacteria (182-fold in wildtype, 208-fold in STAT3-/- knockout) and Enterobacteriaceae (1119-fold in wildtype, 3513-fold in STAT3-/- knockout) copies from the lumenal content of mice receiving the combined injury compared to shams (Fig. 5 A-B). Administration of IL-22 immediately after injury impressively mitigated these large increases in total bacteria (no change) and Enterobacteriaceae (5-fold increase) copies in wildtype mice. However, IL-22 was unable to rescue the large increases in either total bacterial (463-fold increase) or Enterobacteriaceae (9383-fold increase) populations in the STAT3-/- knockout mice (Fig. 5 A-B). Taken together, these data support our hypothesis that IL-22 promotes intestine barrier and mitigates microbial dysbiosis following ethanol and burn injury, however these IL-22 protective effects are dependent on STAT3 signaling in epithelial cells.

Figure 5. IL-22 prevents overgrowth of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae through intestine epithelial cells STAT3 signaling.

Real-time PCR 16S rRNA sequencing of small intestine luminal content in wild-type (white) and VillinCre STAT3-/- knockout (black) mice. Primers were specific for total bacteria (A) and Enterobacteriaceae (B). Data are combined from 2 independent experiments.

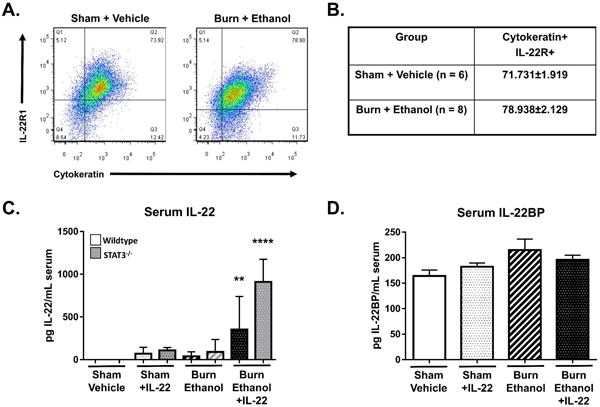

We wanted to assess the levels of circulating IL-22 to verify that IL-22 was indeed present in our mice receiving treatment. Surprisingly, IL-22 was present in circulation of mice receiving ethanol and burn injury alone. While IL-22 levels are elevated following the combined injury, we believe the amount of circulating IL-22 may not be sufficient to provide protective benefits to the intestines. An even more interesting observation was the extremely elevated levels of IL-22 in mice receiving both the combined injury and IL-22 treatment (Fig. 6C). There was no difference in IL-22 receptor expression on intestine epithelial cells following ethanol and burn injury compared to shams (Fig. 6 A-B). We further examined if this IL-22 was potentially sequestered by IL-22BP, however, no differences were observed in the expression of IL-22BP in expression (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. IL-22 treatment results in large amounts of IL-22 in circulation following the combined injury.

Flow cytometry analysis of small intestine epithelial cell IL-22R1 expression in sham vehicle and burn ethanol mice (A-B). Serum levels of IL-22 (C) and IL-22BP (D) in wildtype and STAT3-/- knockout mice following IL-22 treatment and burn ethanol injury. n = 3-14 animals per group from one representative experiment, **p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to untreated sham vehicle.

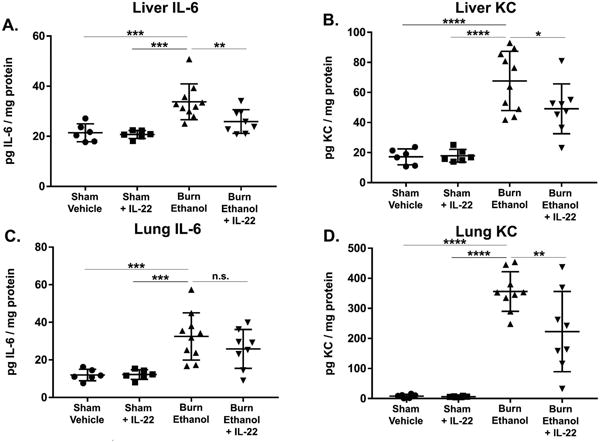

Finally, we wanted to assess whether IL-22 treatment helps to mitigate the systemic inflammation observed following alcohol and burn injury. To address this, we isolated protein from total liver and lung tissues in order to measure inflammatory cytokines present in these peripheral organs. Previous data from our lab have shown high levels of IL-6 and KC in both liver and lung tissues following alcohol and burn injury (13). We observed increased IL-6 and KC in livers and lungs of mice receiving the combined injury (Fig. 7). IL-22 treatment following the injury partially reduced inflammatory markers in all tissues (Fig. 7A-B, D) except for IL-6 in the lungs (Fig. 7C). Collectively, these data suggest that IL-22 treatment helps to partially reduce systemic inflammation following alcohol and burn injury.

Figure 7. Reduced inflammation in liver and lungs of alcohol and burn injured mice receiving IL-22 treatment.

Inflammatory markers were assessed by ELISA in peripheral tissues of mice following alcohol and burn injury with or without IL-22 treatment. Total tissue homogenates from liver (A, B) and lung (C, D) were analyzed for the inflammatory markers IL-6 (A, C) and KC (B, D). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 by One-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc compared to untreated burn ethanol group, n = 6 – 10 mice per group.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that burn injury in the presence of ethanol results in decreased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and results in a significant elevation in Enterobacteriaceae. Administration of recombinant IL-22 restored epithelial cell proliferation, AMP production, and drastically diminished microbial dysbiosis in the small intestine. Our findings further demonstrate that IL-22-mediated protection requires STAT3 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells, as STAT3-/- knockout mice did not benefit from IL-22 treatment following injury. Together, our data highlight the importance of both IL-22 and STAT3 signaling in protection against gut dysbiosis, as well as in maintenance of gut barrier integrity following ethanol and burn injury.

We have previously shown Gram-negative bacteria are present in mesenteric lymph nodes in a 20% total body surface area murine model of burn injury (10). A corollary study in our combined ethanol and burn injury model, which uses a burn injury nearly half the size (12.5% body surface area), showed intestinal barrier leakiness and overgrowth of culturable Gram-negative bacteria within one day following injury. IL-22 treatment significantly reduced gut leakiness and the presence of aerobic Gram-negative bacteria in the small intestine (8). The present study provides a mechanistic role for IL-22 mediated epithelial barrier regeneration and promotion of epithelial AMP secretion through STAT3, which could account for the observed barrier restoration. A recent supporting study from Hanash et al. showed that IL-22 specifically signals through STAT3 in stem cells within the crypts of both the small and large intestines to promote barrier regeneration in a murine model of graft versus host disease(21). While IL-22 has been shown in other models to signal through other STATs or MAPK/ERK pathways(22, 23), we found epithelial cell STAT3 to be necessary for IL-22 mediated protection in our acute model of ethanol and burn injury.

Though this study focused on the role of IL-22 on the epithelial cell barrier and microbiome, it is plausible that IL-22 could be promoting protection through other mediators as well. Several lines of evidence suggest that IL-22 can act as a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune responses following bacterial and viral infections. A recent study showed IL-22 mediated Reg3γ synthesis prevented colonization by antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus faecium via toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 stimulation on dendritic cells(24), and others have demonstrated that IL-22 mediated Clostridium difficile clearance from peripheral organs by upregulating systemic C3 complement activity(25). It appears that T cell TLR signaling may play a role in our model, as we demonstrated that ex-vivo stimulation with TLR ligands restored IL-2 and IFN-γ production(26). While the effects of IL-22 administration on immune cells in our system is still unclear, it is plausible that IL-22 has indirect effects on immune cell signaling in addition to its direct impact on epithelial cells in order to promote AMP secretion and mitigate bacterial overgrowth.

A surprising observation was the extremely high levels of IL-22 in circulation in injured mice receiving IL-22 treatment compared to all other groups. This most likely suggests either clearance of IL-22 following injury is hampered, or alternatively, IL-22 administration results in a positive feedback loop resulting in further IL-22 production from immune cells. Though literature suggests IL-22 can signal in a positive feedback loop in conjunction with IL-20 (27), there are currently no studies to our knowledge that have addressed how IL-22 is cleared from the host. The notion that IL-22 not only helps locally within the intestine, but also aids in prevention and clearance of systemic infections and sepsis has been shown as well. One study elegantly demonstrated that IL-22 helps prevent systemic infection with orally administered Citrobacter rodentium and opportunistic pathogens such as Enterococcus faecalis (28). Elevated IL-22 in infection is observed clinically as well, as patients with abdominal sepsis have elevated serum levels of IL-22 (29). However, whether IL-22 is beneficial is still conflicted, as another study by Weber et al. showed that IL-22 inhibition was beneficial to protect from polymicrobial sepsis (30). Mortality was observed in 3/21 mice receiving ethanol and burn injury alone (data not shown). Ethanol and burn injured mice recovered well from anesthesia and were ambulatory 4 hours following the insult, suggesting that their mortality overnight was independent of the initial shock of the injury. Mortality in ethanol and burn injured mice receiving IL-22 treatment was observed in 2/10 mice and occurred within 4 hours of the injury. This suggests that these animals died from the initial shock from the injury. However, we did not observe significant differences in overall mortality with or without IL-22 treatment (data not shown).

Our data showing the benefits of IL-22 in reducing inflammation in liver and lungs help to partially support this notion. However, we currently do not know whether the reduction in peripheral inflammation is directly due to IL-22, or as a result of another phenomenon such as improvements to the intestine following treatment. While currently we do not know the source of circulating IL-22, we believe what is present in serum is biologically active (i.e. not sequestered by the soluble IL-22 binding protein), and preliminary data suggests IL-22 is free in circulation, not cell-associated (unpublished data). We do not believe the modest increase in serum levels of IL-22 is sufficient to mount a beneficial physiological response to the combined injury alone, and it appears that only serum levels above a certain threshold following IL-22 treatment have a positive physiological effect. However, caution should be used in this regard, as high/prolonged levels of IL-22 are associated with human colon cancer (31).

Finally, the intestinal microbiome likely plays a role in post-burn pathogenesis due to close interactions with the epithelial barrier. In a recent study, our lab showed that large increases in Enterobacteriaceae in the intestinal microbiome of mice following burn injury is also observed in humans following injury (32). Enterobacteriaceae are able to out-compete normal commensal microbial species, specifically within the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes phyla, and can perpetuate the effects of trauma and inflammation (33, 34). Research examining the efficacy of pre- and probiotics following burn injury has failed to show any significant benefits (35), which may be due to changes in the intestinal microenvironment following trauma that allow Gram-negative facultative bacteria to selectively outcompete beneficial commensal microbe colonization. The cause and consequence of Enterobacteriaceae overgrowth in our model remains to be established, and this will be the focus of future studies, as the relationship between the microbiome and intestine epithelial cells is highly important for homeostasis.

In sum, this study highlights the importance of IL-22 and STAT3 signaling for protection against intestinal damage in an acute setting. We also report that IL-22 administration following ethanol and burn injury leads to a significant amount of circulating IL-22 one day after administration, even compared to sham treated animals. This observation gives new insight into either IL-22 clearance and/or a positive feedback loop. Finally, we propose that IL-22 is mainly protective by regulating the intestinal microbiome and preventing overgrowth and translocation of Enterobacteriaceae. Gut barrier disruption and leakiness is common to many different pathologies, and while the mechanism that causes barrier disruption amongst these different diseases may not be the same, our model of ethanol and burn injury provides insight into how IL-22 may help protect the host in these various other conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Suhail Akhtar for his experimental support.

Funding Sources: Supported by NIH R01AA015731, R01 AA015731-09S1, T32AA013527, F31AA024367

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Author Contributions: AMH and MAC conceived the work, AMH, NLM, ARC, OMK, RCG, NVM, IL, and XL performed the experiments and analysis, AMH, BG, and MAC wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zahs A, Bird MD, Ramirez L, Turner JR, Choudhry MA, Kovacs EJ. Inhibition of long myosin light-chain kinase activation alleviates intestinal damage after binge ethanol exposure and burn injury. American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2012;303(6):G705–712. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00157.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swank GM, Deitch EA. Role of the gut in multiple organ failure: bacterial translocation and permeability changes. World Journal of Surgery. 1996;20(4):411–417. doi: 10.1007/s002689900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deitch EA. The role of intestinal barrier failure and bacterial translocation in the development of systemic infection and multiple organ failure. Archives of Surgery (Chicago, Ill : 1960) 1990;125(3):403–404. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410150125024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird MD, Kovacs EJ. Organ-specific inflammation following acute ethanol and burn injury. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;84(3):607–613. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishman JE, Sheth SU, Levy G, Alli V, Lu Q, Xu D, Qin Y, Qin X, Deitch EA. Intraluminal nonbacterial intestinal components control gut and lung injury after trauma hemorrhagic shock. Annals of Surgery. 2014;260(6):1112–1120. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver GM, Albright JM, Schermer CR, Halerz M, Conrad P, Ackerman PD, Lau L, Emanuele MA, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL. Adverse clinical outcomes associated with elevated blood alcohol levels at the time of burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research : Official Publication of the American Burn Association. 2008;29(5):784–789. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31818481bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, Diallo A, Milner SM. The Effects of Preexisting Medical Comorbidities on Mortality and Length of Hospital Stay in Acute Burn Injury: Evidence From a National Sample of 31,338 Adult Patients. Annals of Surgery. 2007;245(4):629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250422.36168.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rendon JL, Li X, Akhtar S, Choudhry MA. Interleukin-22 modulates gut epithelial and immune barrier functions following acute alcohol exposure and burn injury. Shock. 2013;39(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182749f96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rendon JL, Li X, Brubaker AL, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL, Choudhry MA. The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in interleukin-23-dependent restoration of interleukin-22 following ethanol exposure and burn injury. Annals of Surgery. 2014;259(3):582–590. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a626f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earley ZM, Akhtar S, Green SJ, Naqib A, Khan O, Cannon AR, Hammer AM, Morris NL, Li X, Eberhardt JM, et al. Burn Injury Alters the Intestinal Microbiome and Increases Gut Permeability and Bacterial Translocation. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0129996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabat R, Ouyang W, Wolk K. Therapeutic opportunities of the IL-22-IL-22R1 system. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2014;13(1):21–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2011;9(5):356–368. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Akhtar S, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL, Choudhry MA. Inflammatory response in multiple organs in a mouse model of acute alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research : Official Publication of the American Burn Association. 2011;32(4):489–497. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182223c9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faunce DE, Llanas JN, Patel PJ, Gregory MS, Duffner LA, Kovacs EJ. Neutrophil chemokine production in the skin following scald injury. Burns : Journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 1999;25(5):403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canny G, Swidsinski A, McCormick BA. Interactions of intestinal epithelial cells with bacteria and immune cells: methods to characterize microflora and functional consequences. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, NJ) 2006;341:17–35. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weigmann B, Tubbe I, Seidel D, Nicolaev A, Becker C, Neurath MF. Isolation and subsequent analysis of murine lamina propria mononuclear cells from colonic tissue. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(10):2307–2311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhtar S, Li X, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Neutrophil chemokines and their role in IL-18-mediated increase in neutrophil O2- production and intestinal edema following alcohol intoxication and burn injury. American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2009;297(2):G340–347. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00044.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer AM, Khan OM, Morris NL, Li X, Movtchan NV, Cannon AR, Choudhry MA. The Effects of Alcohol Intoxication and Burn Injury on the Expression of Claudins and Mucins in the Small and Large Intestines. Shock. 2016;45(1):73–81. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachman MA, Miller VL, Weiser JN. Mucosal Lipocalin 2 Has Pro-Inflammatory and Iron-Sequestering Effects in Response to Bacterial Enterobactin. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(10):e1000622. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickert G, Neufert C, Leppkes M, Zheng Y, Wittkopf N, Warntjen M, Lehr HA, Hirth S, Weigmann B, Wirtz S, et al. STAT3 links IL-22 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells to mucosal wound healing. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206(7):1465–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanash AM, Dudakov JA, Hua G, O'Connor MH, Young LF, Singer NV, West ML, Jenq RR, Holland AM, Kappel LW, et al. Interleukin-22 protects intestinal stem cells from immune-mediated tissue damage and regulates sensitivity to graft versus host disease. Immunity. 2012;37(2):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamarthee B, Malard F, Gamonet C, Bossard C, Couturier M, Renauld JC, Mohty M, Saas P, Gaugler B. Donor interleukin-22 and host type I interferon signaling pathway participate in intestinal graft-versus-host disease via STAT1 activation and CXCL10. Mucosal Immunology. 2016;9(2):309–321. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K, Kim G, Kim JY, Yun HJ, Lim SC, Choi HS. Interleukin-22 promotes epithelial cell transformation and breast tumorigenesis via MAP3K8 activation. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(6):1352–1361. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abt MC, Buffie CG, Susac B, Becattini S, Carter RA, Leiner I, Keith JW, Artis D, Osborne LC, Pamer EG. TLR-7 activation enhances IL-22-mediated colonization resistance against vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(327):327ra325. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasegawa M, Yada S, Zhen Liu M, Kamada N, Muñoz-Planillo R, Do N, Núñez G, Inohara N. Interleukin-22 Regulates the Complement System to Promote Resistance against Pathobionts after Pathogen-Induced Intestinal Damage. Immunity. 2014;41(4):620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Rendon JL, Akhtar S, Choudhry MA. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 prevents suppression of T-cell interferon gamma production by modulating p38/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways following alcohol and burn injury. Molecular Medicine. 2012;18:982–991. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolk K, Haugen HS, Xu W, Witte E, Waggie K, Anderson M, Vom Baur E, Witte K, Warszawska K, Philipp S, et al. IL-22 and IL-20 are key mediators of the epidermal alterations in psoriasis while IL-17 and IFN-gamma are not. Journal of Molecular mMedicine. 2009;87(5):523–536. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pham TA, Clare S, Goulding D, Arasteh JM, Stares MD, Browne HP, Keane JA, Page AJ, Kumasaka N, Kane L, et al. Epithelial IL-22RA1-mediated fucosylation promotes intestinal colonization resistance to an opportunistic pathogen. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;16(4):504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bingold TM, Ziesche E, Scheller B, Sadik CD, Franck K, Just L, Sartorius S, Wahrmann M, Wissing H, Zwissler B, et al. Interleukin-22 detected in patients with abdominal sepsis. Shock. 2010;34(4):337–340. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181dc07b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber GF, Schlautkotter S, Kaiser-Moore S, Altmayr F, Holzmann B, Weighardt H. Inhibition of interleukin-22 attenuates bacterial load and organ failure during acute polymicrobial sepsis. Infection and Immunity. 2007;75(4):1690–1697. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01564-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang R, Wang H, Deng L, Hou J, Shi R, Yao M, Gao Y, Yao A, Wang X, Yu L, et al. IL-22 is related to development of human colon cancer by activation of STAT3. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris NL, Li X, Earley ZM, Choudhry MA. Regional variation in expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in the intestine following a combined insult of alcohol and burn injury. Alcohol. 2015;49(5):507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, Finlay BB. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;2(3):119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Thiennimitr P, Poon V, Keestra AM, Laughlin RC, Gomez G, Wu J, Lawhon SD, et al. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science. 2013;339(6120):708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayes T, Gottschlich MM, James LE, Allgeier C, Weitz J, Kagan RJ. Clinical safety and efficacy of probiotic administration following burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research : Official Publication of the American Burn Association. 2015;36(1):92–99. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]