Abstract

Background

Intravenous iron allows for efficient and well-tolerated treatment in iron deficiency and is routinely used in diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

Objective

The aims of this study were to determine the probability of relapse of iron deficiency over time and to investigate treatment routine, effectiveness, and safety of iron isomaltoside.

Methods

A total of 282 patients treated with iron isomaltoside were observed for two treatments or a minimum of one year.

Results

Out of 282 patients, 82 had Crohn's disease and 67 had ulcerative colitis. Another 133 patients had chronic blood loss, malabsorption, or malignancy. Patients who received an iron isomaltoside dose above 1000 mg had a 65% lower probability of needing retreatment compared with those given 1000 mg. A clinically significant treatment response was shown, but in 71/191 (37%) of patients, anaemia was not corrected. The mean dose given was 1100 mg, lower than the calculated total iron need of 1481 mg. Adverse drug reactions were reported in 4% of patients.

Conclusion

Iron isomaltoside is effective with a good safety profile, and high doses reduce the need for retreatment over time. Several patients were anaemic after treatment, indicating that doses were inadequate for full iron correction. This trial is registered with NCT01900197.

1. Introduction

Intravenous (IV) iron allows for efficient and well-tolerated treatment in iron deficiency and is routinely used in diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), iron deficiency anaemia is the most common systemic complication and has been reported in 20–42% of patients [1–7], while iron deficiency has been reported in 35–90% of patients [1, 2, 6, 8–10]. Anaemia has been shown to negatively affect health-related quality of life and contribute to chronic fatigue in IBD patients [9, 11, 12].

According to current guidelines, iron supplementation should be administered in all cases of IBD with iron deficiency anaemia and to prevent recurrence of anaemia after prior iron supplementation [13]. In iron deficiency without anaemia, an individualised approach is recommended [13, 14]. The use of oral iron supplementation has limitations in clinical practice, including reduced efficiency, poor tolerance, and low adherence, and thus, IV iron is widely recommended [13, 15–17]. IBD patients with iron deficiency usually need high doses of iron, and full iron correction is in such cases only possible with IV iron treatment [13, 18]. Iron deficiency often recurs in IBD patients after iron replacement therapy [13, 18–20]. Additionally, many IBD patients do not receive adequate treatment for iron deficiency, and increased awareness and optimised treatment strategies are needed [3, 6, 21].

Iron isomaltoside 10% (Monofer®, Pharmacosmos A/S, Denmark) is a high-dose IV iron for fast infusion. The strongly bound formulation of iron and the carbohydrate isomaltoside in a matrix structure enables a controlled slow release of iron with small risk of iron toxicity. This allows for administration of high doses of iron in one visit. More than 3000 patients have been treated with iron isomaltoside in clinical studies until now, and more than 5.3 million doses have been used in clinical practice (data on file, Pharmacosmos A/S, Denmark).

The aims of this study were to determine the probability of relapse of iron deficiency over time, defined as retreatment related to the dose given, and further to investigate treatment routine, effectiveness, and safety of iron isomaltoside in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

Participants were recruited from a total of 10 sites in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in a prospective, observational study conducted from August 2013 to November 2015. Inclusion criteria were age > 17 years and diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia following local clinical guidelines. The patients were treated with iron isomaltoside according to the product label and clinical routine. The patients were followed prospectively for two treatments of iron isomaltoside given or for a minimum of 12 months after the first treatment. For patients not receiving two treatments, the observation time lasted until completion of the study in order to capture a second treatment. Due to the observational design of the study, all procedures were done according to local clinical practice and decisions by the participating investigators.

2.2. Data Collection

Data for iron isomaltoside treatment were collected prospectively for up to two treatments per patient. The dose administered in the study and the calculated iron need [13, 22] were recorded. Use of concomitant medication and pre- and posttreatment blood tests was also recorded. Data were collected from medical records. Treatment response was defined as normalisation of haemoglobin (Hb) or increase in Hb ≥ 2 g/dL [23, 24]. The occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was registered and reported to the sponsor's pharmacovigilance department and according to national reporting systems. The collected data were systematically entered into an electronic case report form (eClinicalOS, Merge Healthcare, NC, USA; licensed by BioStata ApS, Denmark).

2.3. Statistical Methods

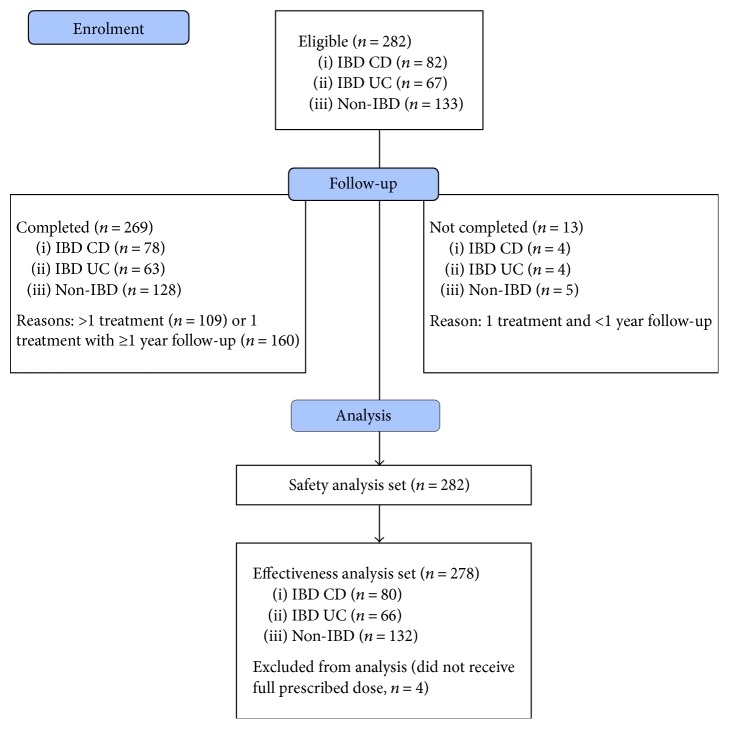

The safety analysis set population (n = 282) included all patients who were enrolled in the study and received the study drug, and the effectiveness analysis set population (n = 278) included all patients who received a full prescribed dose. The patient flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram (based on CONSORT 2010). CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Data are presented with mean and standard deviation or median and range, for continuous variables, and with a number of exposed subjects with percentages for categorical variables. The probability of iron isomaltoside retreatment over time was analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model and was determined from survival plots. Laboratory parameter changes were obtained from an analysis of covariance model. The effect of the iron dose on the Hb response was analysed by logistic regression. The significance cut-off for all analyses was p < 0.05. No formal adjustment for multiplicity was performed. Data were analysed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, USA).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The Regional Ethics Committee in Sweden (EPN Lund 2013/231), the Data Protection Official for Research in Norway (2013/10419), and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2013–41-1543) approved the study. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01900197). All study participants gave written, informed consent before inclusion, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the European Medicines Agency criteria for noninterventional studies [25].

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 282 patients were included in the study, and of these, 82 (29%) had Crohn's disease (CD) and 67 (24%) had ulcerative colitis (UC). A remaining group of 133 (47%) non-IBD patients was iron deficient due to chronic blood loss, malabsorption, or malignancy. At baseline, the use of concomitant medications for anaemia correction was low (oral iron 13%, blood transfusion 3%, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents 0.4%, and cobalamin or folic acid 28%). Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1. As shown, most patients having available ferritin data at baseline (both IBD and non-IBD patients) were iron deficient with a ferritin cut-off < 100 μg/L for iron deficiency. Not enough data for CRP were collected to be able to assess inflammation status.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics.

| IBD CD (n = 82) |

IBD UC (n = 67) |

Non-IBD (n = 133) |

Total (n = 282) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 46 (56.1) | 34 (50.7) | 93 (69.9) | 173 (61.3) |

| Male | 36 (43.9) | 33 (49.3) | 40 (30.1) | 109 (38.7) |

| Anaemica patients | (n = 82) | (n = 67) | (n = 132) | (n = 281) |

| 56b (68.3) | 44b (65.7) | 98 (74.2) | 198 (70.5) | |

| Patients with Hb < 10 g/dL | (n = 82) | (n = 67) | (n = 132) | (n = 281) |

| 14 (17.1) | 11 (16.4) | 41 (31.1) | 66 (23.5) | |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age, years | (n = 82) | (n = 67) | (n = 133) | (n = 282) |

| 42.2 (16.2) | 41.1 (15.9) | 54.3 (18.6) | 47.6 (18.4) | |

| Weight, kg | (n = 78) | (n = 64) | (n = 132) | (n = 274) |

| 73.1 (17.3) | 76.4 (15.4) | 74.6 (16.4) | 74.6 (16.4) | |

| Hb, g/dL | (n = 82) | (n = 67) | (n = 132) | (n = 281) |

| 11.6 (1.7) | 11.5 (1.7) | 10.9 (1.9) | 11.3 (1.8) | |

| TSAT, % | (n = 55) | (n = 41) | (n = 59) | (n = 155) |

| 9.9 (7.1) | 9.4 (6.5) | 10.3 (7.3) | 9.9 (7.0) | |

| Ferritin, μg/L | (n = 70) | (n = 63) | (n = 117) | (n = 250) |

| 34.3 (59.8) | 28.3 (59.1) | 23.9 (84.9) | 27.9 (72.4) | |

| Median (IQR)c | 11.0 (6.2–27) | 11.0 (7.0–21) | 9.0 (5.6–16) | 10.0 (6.0–20) |

aHb < 13 g/dL (men) and Hb < 12 g/dL (women). bMean (SD) Hb in IBD patients 10.8 (1.4) g/dL and mean (SD) weight 75.4 (17.4) kg. cMedian is presented for data not normally distributed. CD: Crohn's disease; Hb: haemoglobin; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; TSAT: transferrin saturation; UC: ulcerative colitis.

3.2. Probability of Retreatment and Treatment Routine

Of the 278 patients receiving a full prescribed dose of iron isomaltoside, 53 (19%) were given >1000 mg, 186 (67%) were given 1000 mg, and 39 (14%) were given <1000 mg at the first treatment. In 264/278 (95%) of patients, the full prescribed dose was administered in one single visit for the first iron isomaltoside treatment.

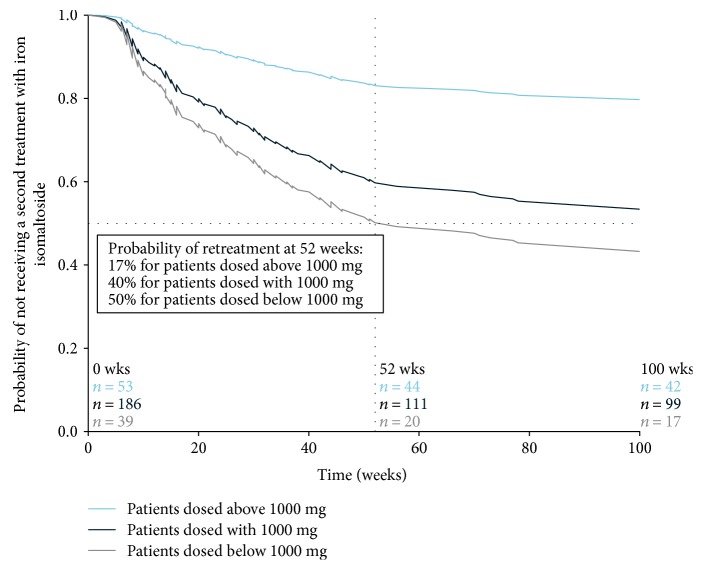

The majority of patients, 170/278 (61%), received only one treatment of iron isomaltoside during a median observation time of 19 (1–27) months. In 108/278 (39%) of patients who were retreated, those who received a dose > 1000 mg at the first treatment had a 65% lower probability (hazard ratio: 0.351; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.19, 0.66) of needing retreatment compared to those given 1000 mg. For patients who received a dose < 1000 mg at the first treatment, there was 36% higher probability (hazard ratio: 1.358; 95% CI: 0.81, 2.27) of needing retreatment compared to patients given 1000 mg. The hazard ratios were corrected for dose, diagnosis, and baseline Hb. The probability of retreatment at 52 weeks split by dose is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Probability of retreatment related to iron isomaltoside dose. The survival plot was obtained by using the Cox proportional hazards model with dose and diagnosis as factors and baseline haemoglobin as covariate. The probability (percent) of retreatment with iron isomaltoside at 52 weeks after the first treatment for each dose group was calculated from the survival curve. The number of patients at weeks 0, 52, and 100 for each dose group includes all patients.

In addition to the administered dose, baseline Hb was an independent predictor of the probability for retreatment, where the need for retreatment decreased by 18% (hazard ratio: 0.825; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.90) for each 1 g/dL unit higher baseline Hb. When comparing patients with CD and UC to non-IBD patients, there were no significant differences in the need for retreatment.

3.3. Effectiveness

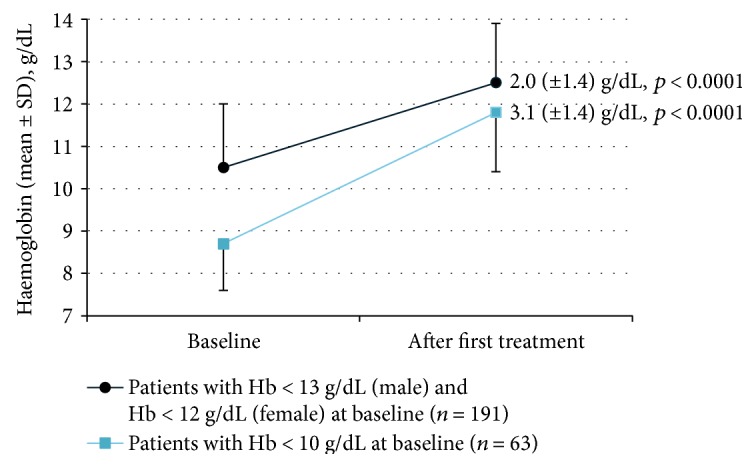

Effectiveness was assessed around 7 weeks after the first iron isomaltoside treatment (see Table 2 and Figure 3). Treatment response following the first treatment was achieved in 143/191 (75%) of the patients who were anaemic at baseline. The response rate after the first treatment increased significantly with an increasing iron isomaltoside dose (8/14 [57%] for doses < 1000 mg, 93/128 [73%] for doses of 1000 mg, and 42/49 [86%] for doses > 1000 mg) even when correcting for baseline Hb (p < 0.05). Of patients with anaemia at baseline, 71/191 (37%) were still anaemic following the first treatment.

Table 2.

Change in iron and blood cell parameters after the first iron isomaltoside treatment.

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Concentration change | p valuea | Time of evaluationb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Hb, g/dL (n = 191)c |

10.5 (1.5) | 12.5 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.4) | <0.0001 | 7.1 (6.0) |

| TSAT, % (n = 108)d |

9.6 (6.5) | 21.0 (9.8) | 11.4 (10.0) | <0.0001 | 7.6 (5.0) |

| Ferritin, μg/L | 25.0 (68.0) | 146.3 (173.1) | 121.3 (162.6) | <0.0001 | 7.4 (6.5) |

| Median (IQR)e (n = 222)d |

10.0 (6.0–20) | 95.0 (49–181) | 71.0 (35–157) | ||

a p values for concentration changes obtained by analysis of covariance test with diagnosis and dose as factors and pretreatment laboratory parameter concentration as covariate. bTime (weeks) between the last administration of first iron isomaltoside treatment and blood test follow-up. cAnaemic patients (Hb < 13 g/dL for men and Hb < 12 g/dL for women at baseline) with available pre- and posttreatment Hb measures in the total population. dPatients with available pre- and posttreatment laboratory measures in the total population. eMedian is presented for data not normally distributed. Hb: haemoglobin; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; TSAT: transferrin saturation.

Figure 3.

Change in haemoglobin (Hb) after the first iron isomaltoside treatment in anaemic patients with available pre- and posttreatment Hb measures. The time of evaluation corresponded to the time between the last administration of first iron isomaltoside treatment and blood test follow-up and occurred during a mean (SD) time of 7.1 (6.0) weeks for anaemic patients at baseline and during a mean (SD) time of 6.1 (4.7) weeks for patients with Hb < 10 g/dL at baseline. The p value calculations were obtained by analysis of covariance test with diagnosis and dose as factors and pretreatment laboratory parameter concentration as covariate.

3.4. Dosing in Clinical Practice and Calculated Iron Need

The calculated iron need using the Ganzoni formula and simplified dosing compared to the actual dose given in the study are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Study dose versus calculated iron need for anaemic patients.

| Anaemic patientsa | IBD CD (n = 50) |

IBD UC (n = 40) |

Non-IBD (n = 95) |

Total (n = 185) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Study doseb, mg | 1058 (338.1) | 1115 (265.6) | 1115 (305.6) | 1100 (306.2) |

| Iron need calculated from simplified dosing table, mg | 1420 (325.1) | 1438 (324.0) | 1532 (316.3) | 1481 (322.9) |

| Iron need calculated from Ganzoni formulac, mg | 1268 (279.4) | 1261 (316.0) | 1380 (284.1) | 1324 (294.2) |

aAnaemia defined as Hb < 13 g/dL for men and Hb < 12 g/dL for women at baseline. Patients having a weight < 50 kg and patients with missing weight data were excluded. bStudy dose for first iron isomaltoside treatment. cGanzoni formula based on a target Hb of 15 g/dL, Hb level before first iron isomaltoside treatment in study, and iron store of 500 mg. CD: Crohn's disease; Hb: haemoglobin; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis.

3.5. Safety

Twelve ADRs were reported in 10/282 (4%) of the patients given a total of 408 high-dose iron isomaltoside administrations. ADRs were seen in seven IBD patients and three non-IBD patients. Infusion reactions were reported in 6/282 (2%) of patients; the rest were delayed hypersensitivity reactions. One of the patients was admitted to the hospital for the treatment of a serious acute infusion reaction with generalised erythema, dyspnoea, general body pain mainly localised to the abdomen, and hypotension. We found no association between dose given and ADRs reported. All patients had uneventful recoveries.

4. Discussion

The main result of this study was that the probability of retreatment with IV iron could be reduced with dosing above 1000 mg. Most patients were given doses of 1000 mg or higher, and the majority received their full prescribed dose in one single visit and were treated only once during the observation period. The administered dose of iron isomaltoside and baseline Hb were independent predictors for retreatment. The response rate increased with higher dose; however, several patients remained anaemic after treatment indicating that patients receive inadequate iron dosing in routine clinical practice.

To our knowledge, no other studies have shown that higher doses of IV iron reduce the need for retreatment over time. In a Swedish observational study, it was demonstrated that the effect of IV iron treatment in IBD patients was mostly sustained for a year with up to 29% of patients being retreated within this period. In this study, however, association to an administered dose was not evaluated [26]. In an Austrian retrospective study following IBD patients treated with iron sucrose, the dose given had no influence on the need for retreatment over time [19].

In line with other studies, we found that the response rate correlated to the iron dose given [19, 20, 27]. There are few observational studies of IV iron in clinical practice in IBD [26, 28–30]. None of these have evaluated the dose given compared to the dose needed for full iron correction. In our study, we found that lower doses than the calculated iron need as recommended by international guidelines were given in clinical practice [13].

Treatment with IV iron in the current study showed a good safety profile with a frequency of hypersensitivity reactions similar to that reported in other studies even if high doses were given to the majority of our patients [15, 18–20, 26–29, 31, 32].

The limitation of our study is the observational design, but one of the aims of the study was to observe treatment routines in clinical practice to provide guidance for optimised treatment strategies for IV iron treatment. Hence, no instructions were given on dosing, time to effectiveness assessment, and retreatment. We did not collect data on clinical disease activity or anti-inflammatory treatment, which can influence recurrence of anaemia and the need for iron retreatment in patients with IBD.

Taken together, iron isomaltoside was effective with a good safety profile in both IBD and non-IBD patients with iron deficiency. A high dose, especially over 1000 mg, reduced the need for retreatment. The administration of higher doses, as recommended in current guidelines, seems required for the full iron correction and prevention of iron deficiency anaemia.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we show that iron isomaltoside allows for efficient and well-tolerated treatment in iron deficiency and furthermore that high doses reduce the need for retreatment over time. Several patients were anaemic after treatment, indicating that doses routinely given were inadequate for full iron correction. Infusion reactions were reported in 2% of patients, similar to what has been reported in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all investigators and study staff for their contribution to the study, as well as BioStata ApS, Denmark, for providing statistical support. This work was supported by Pharmacosmos A/S, Denmark. From Pharmacosmos A/S, Denmark, the authors specially thank Dorte Rytter Nielsen, Malin Winterleijon, and Sylvia Simon for coordinating and supporting the study. Critical language review of the manuscript was carried out by Associate Professor Dominic-Luc Webb, Uppsala University, Sweden.

Disclosure

Two earlier versions of this work were presented as posters at the 10th and 12th Congress of ECCO (European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation) in 2015 and 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The study centres received a fee per patient from the sponsor. The corresponding author has received fees from the sponsor for presenting the study data. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bager P., Befrits R., Wikman O., et al. The prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency in IBD outpatients in Scandinavia. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;46(3):304–309. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.533382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bager P., Befrits R., Wikman O., et al. High burden of iron deficiency and different types of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease outpatients in Scandinavia: a longitudinal 2-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;48(11):1286–1293. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.838605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lupu A., Diculescu M., Diaconescu R., et al. Prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency in Romanian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2015;24(1):15–20. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.lpu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ott C., Liebold A., Takses A., Strauch U. G., Obermeier F. High prevalence but insufficient treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2012;2012:7. doi: 10.1155/2012/595970.595970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergamaschi G., Di Sabatino A., Albertini R., et al. Prevalence and pathogenesis of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Influence of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment. Haematologica. 2010;95(2):199–205. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.009985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisshof R., Chermesh I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2015;18(6):576–581. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg N. D. Iron deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 2013;6:61–70. doi: 10.2147/ceg.s43493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisbert J. P., Gomollon F. Common misconceptions in the diagnosis and management of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;103(5):1299–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells C. W., Lewis S., Barton J. R., Corbett S. Effects of changes in hemoglobin level on quality of life and cognitive function in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;12(2):123–130. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000196646.64615.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein J., Bager P., Befrits R., et al. Anaemia management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: routine practice across nine European countries. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2013;25(12):1456–1463. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328365ca7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pizzi L. T., Weston C. M., Goldfarb N. I., et al. Impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2006;12(1):47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000191670.04605.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czuber-Dochan W., Ream E., Norton C. Review article: description and management of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;37(5):505–516. doi: 10.1111/apt.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignass A. U., Gasche C., Bettenworth D., et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2015;9(3):211–222. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Assche G., Dignass A., Bokemeyer B., et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 3: special situations. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2013;7(1):1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindgren S., Wikman O., Befrits R., et al. Intravenous iron sucrose is superior to oral iron sulphate for correcting anaemia and restoring iron stores in IBD patients: a randomized, controlled, evaluator-blind, multicentre study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;44(7):838–845. doi: 10.1080/00365520902839667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonovas S., Fiorino G., Allocca M., et al. Intravenous versus oral iron for the treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(2, article e2308) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein J., Dignass A. U. Management of iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease - a practical approach. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2013;26(2):104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinisch W., Altorjay I., Zsigmond F., et al. A 1-year trial of repeated high-dose intravenous iron isomaltoside 1000 to maintain stable hemoglobin levels in inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;50(10):1226–1233. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1031168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulnigg S., Teischinger L., Dejaco C., Waldhor T., Gasche C. Rapid recurrence of IBD-associated anemia and iron deficiency after intravenous iron sucrose and erythropoietin treatment. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(6):1460–1467. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evstatiev R., Alexeeva O., Bokemeyer B., et al. Ferric carboxymaltose prevents recurrence of anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;11(3):269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumenstein I., Dignass A., Vollmer S., Klemm W., Weber-Mangal S., Stein J. Current practice in the diagnosis and management of IBD-associated anaemia and iron deficiency in Germany: the German AnaemIBD Study. Journal of Crohn’s & Colitis. 2014;8(10):1308–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganzoni A. M. Intravenous iron-dextran: therapeutic and experimental possibilities. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1970;100(7):301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMaeyer E. M., Joint WHO/UNICEF Nutrition Support Programme . Preventing and Controlling Iron Deficiency Anaemia Through Primary Health Care : a Guide for Health Administrators and Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Assessement, Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.EMA. Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council Article 2(c) Luxembourg: European Medicines Agency; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Befrits R., Wikman O., Blomquist L., et al. Anemia and iron deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease: an open, prospective, observational study on diagnosis, treatment with ferric carboxymaltose and quality of life. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;48(9):1027–1032. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.819442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinisch W., Staun M., Tandon R. K., et al. A randomized, open-label, non-inferiority study of intravenous iron isomaltoside 1,000 (Monofer) compared with oral iron for treatment of anemia in IBD (PROCEED) The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(12):1877–1888. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khalil A., Goodhand J. R., Wahed M., Yeung J., Ali F. R., Rampton D. S. Efficacy and tolerability of intravenous iron dextran and oral iron in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-matched study in clinical practice. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011;23(11):1029–1035. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834a58d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortes X., Borras-Blasco J., Moles J. R., Bosca M., Cortes E. Safety of ferric carboxymaltose immediately after infliximab administration, in a single session, in inflammatory bowel disease patients with iron deficiency: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2015;10(5, article e0128156) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Lopez S., Bocos J. M., Gisbert J. P., et al. High-dose intravenous treatment in iron deficiency anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease: early efficacy and impact on quality of life. Blood Transfusion. 2016;14(2):199–205. doi: 10.2450/2016.0246-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahlerup J. F., Jacobsen B. A., van der Woude J., Bark L. A., Thomsen L. L., Lindgren S. High-dose fast infusion of parenteral iron isomaltoside is efficacious in inflammatory bowel disease patients with iron-deficiency anaemia without profound changes in phosphate or fibroblast growth factor 23. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;51(11):1332–1338. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1196496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bager P., Hvas C. L., Dahlerup J. F. Drug-specific hypophosphatemia and hypersensitivity reactions following different intravenous iron infusions. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2017;83(5):1118–1125. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]