Abstract

The cumulative total of persons forced to leave their country for fear of persecution or organized violence reached an unprecedented 24.5 million by the end of 2015. Providing equitable access to appropriate health services for these highly diverse newcomers poses challenges for receiving countries. In this case study, we illustrate the importance of translating epidemiology into policy to address the health needs of refugees by highlighting examples of what works as well as identifying important policy-relevant gaps in knowledge. First, we formed an international working group of epidemiologists and health services researchers to identify available literature on the intersection of epidemiology, policy, and refugee health. Second, we created a synopsis of findings to inform a recommendation for integration of policy and epidemiology to support refugee health in the US and other high-income receiving countries. Third, we identified eight key areas to guide the involvement of epidemiologists in addressing refugee health concerns. The complexity and uniqueness of refugee health issues, and the need to develop sustainable management information systems, require epidemiologists to expand their repertoire of skills to identify health patterns among arriving refugees, monitor access to appropriately designed health services, address inequities, and communicate with policy makers and multidisciplinary teams.

Keywords: epidemiology, refugees, asylum seekers, emigrants and immigrants, public policy, health policy, minority health, health status disparities, health care disparities, health services

Introduction

Large numbers of people are currently fleeing from persecution or organized violence. By the end of 2015, the cumulative total of displaced persons in the world had reached 65.3 million, the highest ever: this included 40.8 million internally displaced persons and 24.5 million who had left their country and were dispersed over more than 164 other countries. Among the latter group, 51 percent were under 18 years of age [1]. In 2015, 12.4 million people worldwide were newly displaced due to conflict or persecution; more than half (54 percent) originated from the Syrian Arab Republic (4.9 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million) and Somalia (1.1 million) [1].

High-income countries have unique resources for sheltering refugees, but they shoulder only a small part of the burden compared to many low- and middle-income countries. Indeed, developing regions host 86 percent of the 16.1 million refugees under the mandate of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) [1]. Refugees and asylum seekers migrate to other countries to escape persecution and violence, with the hope of successful resettlement or voluntary repatriation to their own countries. Refugee and asylum-seeker groups vary widely in education, health literacy, cultural beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. There is no “one size fits all” approach to identifying health needs and facilitating integration into each country’s health care system. The legal status of refugees and asylum seekers is a key factor in obtaining government assistance such as housing, food, vocational training and health insurance [2,3]. Traditionally, early-stage health assessment focused on communicable diseases (to avoid infection of the local population) and on mental health issues (to help cope with trauma caused by conditions in the home country, during transit, and on arrival in the receiving country) [2,4]. Increasingly, however, policy-makers are concerned with ensuring equitable, long-term access to appropriate health services, including management of chronic diseases and development of comprehensive programs that address social determinants of health and evaluate the health impact of policies [5–7].

In 2009, the American College of Epidemiology initiated an effort to illustrate the contributions and role of epidemiologists in health policy for a wide range of public health issues. The initiative has resulted in more than 2 editorials and 11 peer-reviewed articles [8]. All papers in this series have used a similar methodology—convening experts in the field to identify lessons learned, and participating in an in-person working meeting to develop this and other case narratives on the role of epidemiology in health policy. In this article, we discuss the importance of epidemiology in policies on refugee health and related issues, highlighting lessons learned from effective examples and from challenges that have arisen in attempting to implement these examples, as well as identifying important policy relevant gaps in knowledge. The focus will be on refugee movement over the past 15 years to Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia.

Methods

The American College of Epidemiology’s (ACE) Policy Committee convened in April 2016 an ad hoc working group of international experts in refugee health, epidemiology, policy, and program administration.

The workgroup consisting of representatives from the US, Canada, and the Netherlands (European Union), developed this paper through an iterative review process. The workgroup searched commercial library databases for peer-reviewed papers, reference lists, books, reports from international agencies and relief organizations, and unpublished data at national, state and local levels from 1999 to 2016. The scoping review focused on definitions of refugees and migrants, their health needs, and existing refugee policies. We used a combination of key terms and various synonyms as search terms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Concepts and key search terms used in the search process

| Refugees | Health | Country | Policy | Other terms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Using EBSCO databases, we searched the literature using search features inherent to each database to refine the results by source types, publication year, subject, publications, language, age, geography and more. For illustration purposes, a sample search limited to 1999–2016 year range using the following searching strategy produced a similar number of articles across all databases searched:

(refugees OR asylum seekers OR asylum applicants OR migrants OR unaccompanied minors) AND ("mental health" OR "infectious diseases") AND ("United States" OR US OR Europe OR Canada OR Australia) AND (polic* OR law OR guidelines) AND (health assessment OR health screening)

Search Results

The most relevant articles from this initial search came from EBSCO databases (a total of 448 hits), including PsychINFO (81 hits), Academic Search Complete (77 hits), MEDLINE (33 hits), Health Policy Reference Center (32 hits), and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition (28 hits). In addition, unique articles were identified in databases from other vendors and publishers, such as PubMed (73 hits), ScienceDirect (80 hits) from Elsevier, and Web of Science from Thomson Reuters (34 hits). In contrast to these low numbers of hits, Public Health from ProQuest retrieved 7,622 results. The high number of hits in Proquest Public Health database is due to the inclusion of dissertations and theses (1,299) and peer reviewed articles (5,141) that are unique to this particular database compared to the others. We excluded dissertations and theses from our review due to their length and comprehensive overview of a specific health problem. We also examined online reports in addition to grey literature to which we had previous awareness due to prior research experience.

The background information was focused on policies and statistics from high-income countries (United States, Europe, Canada, and Australia), excluding movement between low-income countries (e.g. from one African country to another). We excluded articles and reports on refugee health that were unrelated to epidemiologic research (e.g. descriptions of refugee programs without data or local descriptive case studies). In addition, we also excluded studies with convenience sample or descriptive case studies. The following migrant groups were not included in our final samples of references: internally displaced persons, economic migrants, and people entering the US, Canada, Europe and Australia illegally from refugee sending countries who do not apply for refugee status. The languages of articles were restricted to English, French, German, and Spanish because of authors’ language proficiency and lack of time to arrange translating resources. Using Zotero, a citation management software, we removed duplicates of references and irrelevant studies based on previously defined exclusion criteria.

Based on our findings and group discussion, we developed an outline for the paper, and workgroup members were assigned to write and/or review sections based on their area of expertise. All members reviewed and commented on the manuscript and any inconsistencies or presentations of national differences were discussed via email and conference calls in an iterative process until consensus was reached.

Results

We identified eight key lessons from effective examples and from challenges that have occurred in providing services to refugees (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of lessons learned

| 1. Nomenclature and definitions for refugee and asylum seekers often vary. |

| 2. It is necessary to develop efficient systems to identify health needs upon arrival and lay the foundation for integration into health care. |

| 3. Data sources need to be integrated and linked to allow ongoing monitoring of refugee health indicators. |

| 4. It is important to assess social determinants of health and adopt an intersectoral “health in all policies” approach to create health-promoting environments for refugees and asylum seekers. |

| 5. Refugees and asylum seekers must be granted equitable access to appropriate health services. |

| 6. Health services for refugees and asylum seekers must be evidence-based, integrated into the mainstream health care system, and delivered in accessible and effective ways. |

| 7. Initiatives to improve access to and quality of health care need to be evaluated. |

| 8. Training of epidemiologists needs to provide the tools to engage with policy makers and the public. |

Lesson 1: Nomenclature and definitions for refugee and asylum seekers often vary

One of the first challenges epidemiologists face is identifying an agreed definition of “refugees.” Unfortunately, no such definition exists. A distinction is often made between refugees being forced to leave and economic migrants voluntarily seeking a better life, but the distinction between “forced” and “voluntary” is hard to sustain. Refugees who leave have made a deliberate choice to flee rather than face danger and possible death. Economic migrants may be escaping conditions at least as threatening: natural disasters, climate change, grinding poverty, “failed states” and other possibly life-threatening circumstances not covered by refugee law [9].

What are the existing legal definitions? The United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol define a refugee as any person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country […..]” [10]. Each person seeking “Geneva” refugee status must therefore show he or she have good cause to fear such persecution. Simply coming from a country where there is organized violence is not usually considered sufficient.

However, other forms of protection are available. The 1969 Organization of African Unity Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of the Refugee Problem in Africa extended protection in Africa to those coming from war-torn countries. Weaker but more accessible “complementary” forms of protection have also been introduced in most countries, including temporary protection (requiring a return to the country of origin when circumstances permit) and humanitarian or discretionary protection. All these types of status are usually included in the general category of “refugee.” The UNHCR even adds a category “persons in refugee-like situations” for certain groups which in its view should be treated as refugees, but are not covered by existing legislation [1].

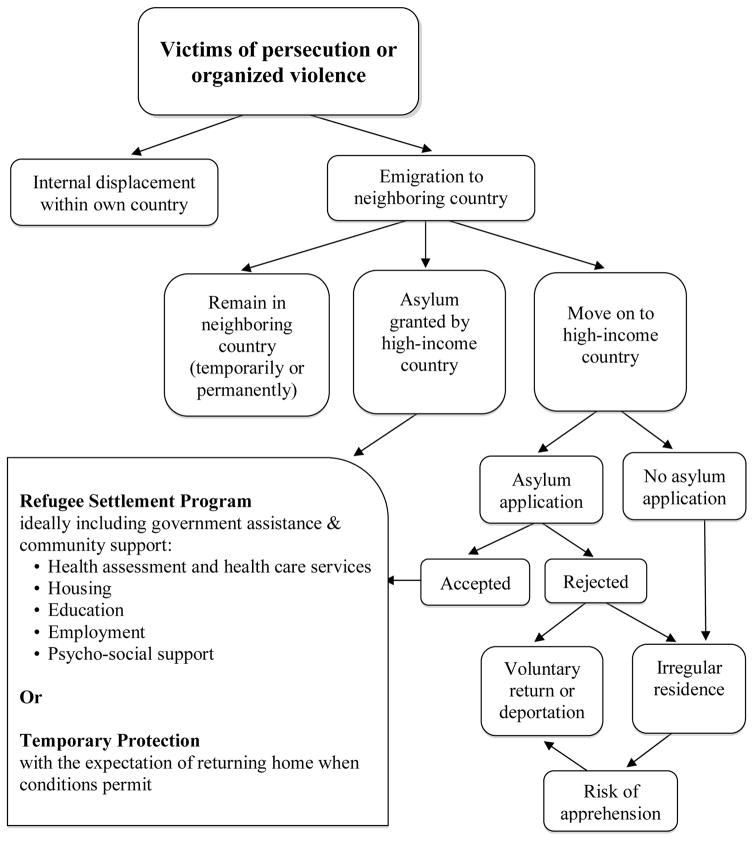

In this paper, we use the term “refugee” to refer to people whose claim to this status has been allowed. For researchers, however, the problem with this definition is that the legal assessment procedure can take years. Thus, research on “recognized” refugees is often carried out long after they have left their country. Even then, it is often difficult to locate this group because their refugee status may not be recorded in population registers. Before the grant of a status, the only way to identify refugees is by using empirical rather than legal criteria, but there is no general agreement on which criteria should be used. One can study groups of people in transit from a conflict-ridden country to a safe one, but there is no guarantee that all of them will acquire refugee status (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathways to safety for victims of persecution or organized violence

Before they receive this status, most refugees will have spent some time seeking asylum. Useful research can be carried out on the category of asylum seekers, though here again there are formal and informal definitions. Legally speaking, an “asylum seeker” or “asylum applicant” only counts as such after they have made an application for asylum. However, in everyday usage, those still searching for a place to apply (e.g. “boat people”) are often called asylum seekers as well. Some of these may apply for refugee settlement in a high-income country while they are sheltering in a neighboring country; others may enter a high-income country legally using a tourist or student visa and subsequently apply for asylum; and others will enter without authorization. Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention forbids States Parties from penalizing unauthorized entrants if they present themselves without delay to the authorities. However, if they fail to make a timely application, or are rejected and refuse an order to leave the country, they will become “undocumented” or “irregular” migrants. In this position, they will usually enjoy very limited entitlements to health services. By contrast, once a person is officially an asylum applicant they will usually be able to count on a reasonable level of health service provision, especially if they remain in government-run centers.

A final complication of terminology concerns whether a refugee or asylum seeker should be considered a type of migrant, or in a class by themselves. UNHCR has long maintained that refugees are not migrants and should not be classified as such. However, according to the UN’s own official definition, migrants are people who have changed their country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason. Within the UN system both definitions tend to be used alongside each other, which does little to reduce confusion in an area where clarity is badly needed [11].

Lesson 2: It is necessary to develop efficient systems to identify health needs upon arrival and lay the foundation for integration into health care

Port of entry screening and use of quarantine facilities dates back centuries [12]. Historically, immigration officials focused on detecting, treating and containing infectious diseases that migrants may carry. Present-day guidelines also address infectious diseases, such as Tuberculosis (TB), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis, Malaria and intestinal parasites, as well as childhood vaccinations [6,13,14]. Over time, a more rights-focused approach developed alongside the public health approach. This has recently been referred to as the health settlement approach [6]. It aims to vaccinate, screen, treat and integrate refugees into local primary health care systems. Rights-focused guidelines have placed greater emphasis on promoting health [15] and progressed on to consider non-communicable conditions such as mental health problems and chronic diseases [16]. Evidence-based approaches consider both the benefits and harms of interventions [17].

While it may not be possible to identify all needs in the initial health exam, basic questions on pregnancy or pregnancy intention and contraceptive needs and chronic diseases should be part of a standard assessment. Current practices vary by country. For instance, Canadian national guidelines include screening for unmet contraceptive needs during the initial assessment period [7], while in the US, national guidelines for refugee arrivals require only documentation of pregnancy status [13], leaving it to individual states to require more comprehensive assessments of sexual and reproductive health needs.

Beyond the initial screening, we must explore how integration into primary care is handled. Some screening locations (e.g., public health clinics providing follow-up visits at the same location) facilitate care continuity and coordination; others do not. It is also necessary to establish surveillance systems that allow us to monitor refugees’ and asylum-seekers’ access to care and health outcomes over time, as discussed in Lesson 3.

Lesson 3: Data sources need to be integrated and linked to allow ongoing monitoring of refugee health indicators

Interdisciplinary population-based studies are critical for evidence-based refugee health. These studies can detect inequities at both the disease and the health care system level. Large national longitudinal studies have been conducted in Australia [18] and Canada [19]. These studies have helped us appreciate the risk factors for decline in health including low health literacy, poor health of migrants from low-income countries, and gender differences. However, following highly mobile and multilingual populations over time is expensive and not very feasible, except in countries like Sweden, where multiple databases covering the entire population can be linked with each other.

Two examples of initiatives to improve surveillance for refugees in the US include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded Electronic Disease Notification System (EDN), and the Centers of Excellence in Refugee Health (COE-RH) in Colorado and Minnesota. The EDN is an electronic reporting system that collects health information on newly arriving refugees and immigrants [20]. However, one challenge for epidemiologic research is linking different data sources together (e.g., a unique linking identifier may not be available, refugee status is not always captured in data sources). One linking approach is the creation of a quasi-relational database and employing a probabilistic matching methodology as described in the Florida 2009 Refugee Health Status and Healthcare Utilization Report [21].

In the US, the federally-funded Centers of Excellence in Refugee Health (COE-RH) in Colorado and Minnesota have the mission to assess long-term health outcomes of refugees, multi-state surveillance of chronic and infectious diseases among refugees, and the development of clinical guidelines relevant for refugee populations settling in the US. The Colorado COE-RH [22] strives to collect and better analyze the medical screening data from refugees in the initial health-intake screening and to standardize data collection, which differs from state to state, and display it in a business intelligence platform. This will help providers, state partners, community leaders, and the public in accessing refugee health data and patterns. The Minnesota COE-RH works to improve the guidelines [23] and demonstrates how providers should conduct the initial health-intake medical screening as well as a few quality improvement projects such as Hepatitis B prevention. A women’s health guideline is planned to be included that will serve as a nationwide standard.

There remains a need to consider the inclusion of variables in electronic health records and data systems that allow ongoing monitoring of refugees, such as Country of birth, Language preference, Entry date, and Refugee/asylum status to the extent that privacy and ethical concerns can be addressed. For example, in the US refugees and asylum applicants have specific aid codes when using publicly funded health services, however the accuracy and completeness of the aid code has not been assessed. Current methods are still inadequate to differentiate between refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants in the US, making it challenging to calculate denominator data for these groups.

Lesson 4: It is important to assess social determinants of health and adopt an intersectoral “health in all policies” approach to create health-promoting environments for refugees and asylum seekers

Recognizing and improving living conditions and other social determinants is crucial for preventing and treating illness. Since the publication of the World Health Organization (WHO) Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health [24], increasing priority has been given to tackling the causes of illness through the strategy of “health in all policies”, a collaborative approach to improving the health of all people by incorporating health considerations into decision-making across sectors and policy areas [25]. This pragmatic approach is as relevant to refugees as it is to all other groups, while epidemiological research is essential to provide its evidence base.

A wide range of factors may influence the health of refugees before, during and after forced migration. Pre-migration factors can be further subdivided into factors that occur before and during the conflict. Average living conditions in the home country may be harsh, yet it is often not the worst-off who succeed in obtaining asylum: considerable personal or family resources may be necessary to succeed in obtaining protection in a safe country. Stereotypes regarding the socio-economic background of refugees from a given country can therefore be misleading.

Traditionally, researchers have regarded violence, deprivation and loss during the conflict and forced migration phase as the main source of physical and mental ill-health among refugees [12]. What is often overlooked is that serious health threats also exist in the pre-conflict situation and the processes of reception and integration in a new country [26]. Threats to health during forced migration can be fatal. Thousands of people – the true number will never be known – die each year while trying to reach safety; for those who survive, the journey may be accompanied by acute deprivation, exploitation, and violence of all kinds. Safe and legal pathways to claiming asylum would obviate most of these risks, but high-income countries are reluctant to provide these for fear of being overwhelmed by the demand.

Humane asylum procedures and effective integration policies are essential to ensure successful resettlement in a new country. Since the seminal work of Silove et al. [27], it has been increasingly recognized that the conditions in which asylum seekers are kept can be a major source of mental health problems. Prolonged uncertainty, inactivity and social isolation delays and undermines social integration. Resettlement support for employment, language skills, health care and housing support varies widely by country and region and over time within a country. This support is normally limited to recognized refugees, excluding asylum seekers. After acquiring a residence permit and potentially some limited resettlement support, refugees are all too often left to sink or swim in the new society without the long-term targeted, proactive support they need. If their claim for international protection is rejected, asylum seekers will very often remain in the country as “undocumented migrants,” with an even higher risk of marginalization and ill-health.

A recent report [28], mainly focused on Europe but drawing also on insights from the rest of the world, points out that the integration of refugees has frequently been unsuccessful in the past, resulting in marginalization, deterioration in living conditions and health, and chronic dependency on welfare. A proactive approach could save governments a lot of money in the end, yet few appear to realize this. Successful integration policies are described as “work-focused but not myopic, pre-emptive, coordinated and collaborative”; these priorities apply to migrant integration in general, not just to refugees. Advocating for enlightened policies needs to be backed up by sound epidemiological evidence. For example, Hjern [29] showed that most of the barriers to the successful integration of refugees in Sweden are more likely to be the cause, rather than the result, of impaired mental and physical health.

Lesson 5. Refugees and asylum seekers must be granted equitable access to appropriate health services

When the health system does not respond to the needs of any group to the best of its abilities, preventable and treatable illnesses become health inequities (i.e., unjust and avoidable disparities). Research on health service provision for migrants has shown that services provided to migrants are very often less affordable, harder to reach, and of lower quality (because they are often not adapted to the patient’s needs). Therefore, providing the best available services will often mean challenging or circumventing existing policies, for example, when these disallow reimbursement of service providers for providing treatment or interpretation services [30,31].

Many studies on inequities in health service provision to migrants have been carried out on an ad hoc basis, using a variety of different approaches, methods and samples that are difficult to combine and compare with each other. However, in 2015, the first round of a systematic longitudinal project in 38 countries was carried out to monitor levels of inequity for migrants in health care systems. This was part of a larger study, the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX), which has been gathering data since 2003 on different “strands” of migrant integration such as access to education and the labor market [32]. The addition of a “health strand” in 2015 [33] acknowledged the importance of health as an aspect of migrant integration [34].

MIPEX now measures health policies applying to migrant workers, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants, using a standardized set of 38 indicators. These indicators map two dimensions of policy:

Access — consisting of migrants’ entitlements to health services (i.e., affordable health care coverage) and accessibility (“reachability”) of health services for migrants.

Quality—consisting of responsiveness of health services to migrants’ needs and measures to achieve change, (i.e., to improve equity).

For epidemiologists working in refugee health, the most relevant findings of the MIPEX 2015 survey were:

Entitlements are best for migrants with a work permit and lowest for undocumented migrants, with asylum seekers in between. After protected status has been officially granted, refugees usually have the same entitlements as nationals.

A lack of information for migrants on how to use health services can be another serious barrier to access. A more outreaching approach, possibly employing “health navigators” or “cultural mediators”, may be needed.

Countries vary widely in their readiness to make services responsive to migrants’ needs. In English-speaking countries the concept of “cultural competence” has been propagated for several decades [35]; by contrast, eight of the European countries studied in MIPEX scored zero on this dimension, which includes attention for language barriers.

Measures to promote change include data collection and research, as well as coordinated efforts to link up stakeholders and provide leadership. These were more often found in countries with tax-based, rather than insurance-based, health systems.

Lesson 6: Health services for refugees and asylum seekers must be evidence-based, integrated into the mainstream health care system, and delivered in accessible and effective ways

Integrating refugees into robust health care systems must be a primary aim for public health, as separate programs for refugees will be vulnerable to budget cuts [36].

However, the implementation and delivery of refugee services must also consider how much refugee populations value the main outcomes of interventions, how acceptable and feasible are the interventions and what equity impacts could arise as a result of special services [37]. For example, routine testing during medical visits may not be acceptable to refugees coming from areas with a high degree of HIV-related stigma, while testing at community sites may be more acceptable and effective at reaching –the refugees– at highest risk for HIV exposure [38].

When we link a delivery approach with an intervention, we create a complex intervention. Research on delivery of services requires pilot testing, feasibility and on-going evaluation. A systematic and explicit process can be used to determine the effects and the certainty of these effects. Canada, US, and Australia have developed guidelines including delivery considerations for refugees [39]. Programs that show signs of effectiveness and efficiency nationally, and internationally, may be good candidates for scaling up. Similar to other interventions, benefits and harms, certainty of effect, cost effectiveness, and values and preferences should be considered evidence for all interventions and programs.

In 2015, with the Syrian war and refugee crisis, Europe was pressed to improve healthcare and other services for refugees and other migrants. As massive numbers of migrants arrived on the beaches of Greece, the European Union gained support for launching many research initiatives. Movements of refugees and other migrants across Europe left many non-government organizations and public health officials asking how Europe can improve health care delivery for newly arriving migrants. One such initiative is the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control evidence-based guidelines for health assessment and prevention for newly arriving migrants. These guidelines will hopefully encourage consistent and evidence-based health assessments that can begin at port of entry, play a role in detention centers and help deliver services at the community and public health level.

Lesson 7: Initiatives to improve access to and quality of health care need to be evaluated

The seventh lesson learned is that evaluation of initiatives to improve health care will not only help public and private organizations deliver better programs but also help sustain programs by documenting their quality and effectiveness. Refugee health program evaluation should be guided by the general principles of program evaluation, with particular emphasis on clarity and agreement among stakeholders regarding program components and outcomes, participation by the targeted community and knowledge of community complexities [30]. Innovative methods to evaluate refugee programs include using feedback loops, multilevel and mixed method data collection, and pre-post designs when the use of control groups present ethical challenges.

Agreement of clear outcome definitions among all stakeholders and partners remove excuses for inaction [30]. The multiple partners of the Australian Changing Cultures Project experienced time-consuming difficulties identifying the outcomes of a refugee education program [40]. Successful collaborations can involve State leadership in initiatives [41,42]. A Colorado initiative that developed a single point of access including interpreting services, comprehensive health assessments, education, data collection, and evaluation [43].

Refugee and community involvement are useful partners in evaluation; they can identify meaningful questions, interpret non-verbal cues and understand cultural perspectives [44,45]. An intervention to improve mammography screening among Serbo-Croatian speaking refugees in a Massachusetts hospital hired a patient navigator who was also a displaced person from the same war as the patients. She helped develop trusting relationships with the patients facilitating implementation and evaluation [46]. An intervention involving a prenatal educational video among a Minnesota Somali refugee population sought out refugee acceptability of the video before implementation [47].

Knowledge of community complexities is also important when evaluating health initiatives. Self-proclaimed community leaders representing subgroups rather than the entire community disrupted social structures, and decision-making complexities within refugee groups must be taken into account [48]. An intervention in Salinas, California among unaccompanied Central American minors unknowingly put adolescents who fled violence and death threats in the same room as adolescents who may have been related to or acquainted with the perpetrators [48]. Complexities in evaluation can also include community resilience [49–52]. Evaluation studies examining the mental and physical health of unaccompanied minors in high-income countries show long-term improvement years after initial resettlement [49]. Cultural differences in parenting practices lead US welfare services to remove refugee children from their homes. The Bridging Refugee Youth and Children's Services (BRYCS) evaluated the issue and conducted a series of community conversations between refugees and child welfare services that reduced tensions between refugee parenting culture and US child welfare practices [53].

Evaluations involving feedback loops, audit, reflection and modification cycles, can improve interventions. In Australia, refugee youth can receive up to a year in language education before they join their peers in school. The Changing Cultures Project used feedback loops and realized that language skills alone could take several years to obtain, thus, modified six refugee language and health programs [40]. An occupational therapy program aimed at refugee high school students in Australia used feedback loops and changed significantly over three cycles; from a focus on individual task mastery in the classroom environment to a focus on the development of social competence through an activity-based group program [54]. In addition to feedback loops, interventions through high school populations are a convenient way to minimize financial, structural and cultural barriers faced by refugee children [54,55].

Many refugee programs use multiple interventions and collaborations. A successful evaluation of a Federally Recognized Health Center program serving Cambodian refugees in Massachusetts included data collected by community-based organizations, who provided advocacy, peer support, stress management, and education, as well as data from the health centers [56,57]. Torres et al. used multiple evaluation strategies to evaluate the effectiveness of community health works (CHW) employed by a service provider organization compared to independent CHW. They used direct observation, in-depth interviews, analysis of policy documents and quantitative analysis of a caseload database [58]. This method allowed identification of nuances as well as evaluation [58]. The Australian Changing Cultures project used mixed methods evaluation including routinely collected data, group interviews with refugees and staff, program audits and observation of management meetings [45].

Many evaluation studies targeting health interventions lack control groups or randomization for experiments, while some do not follow up for long enough to provide meaningful conclusions [59]. Fox et al. evaluated a cognitive-behavioral school-based program by measuring screening scores on the Children's Depression Inventory [60]. The authors noted that using a treated and non-treated group may have improved validity but also created an ethical dilemma because they were not aware of any other mental health services in the community. Based on this, the authors decided to include all vulnerable refugee children; they had no external comparison group but used a pre-post evaluation design involving an internal comparison group [60]. Evaluators of refugee programs frequently use pre-post design [46,55,60,61].

Lesson 8: Training of epidemiologists needs to provide the tools to engage with policy makers and the public

The seven lessons detailed above are essential for the training of epidemiologists seeking to engage in refugee health work and/or research. One final component involves training in risk- or health communication to prepare epidemiologists to work on refugee health issues and communicate with policymakers and the public including refugees. Such communication is necessary, but often an afterthought in refugee emergency response situations.

Epidemiologists need to learn to communicate to the public and policymakers with language and examples, which they will understand, to counterbalance misinformation and provide accurate data. However, they are typically not trained to communicate with findings to a larger audience. For example, media stories can help to humanize the refugee experience and make data on health risks and challenges of integration into health care and equitable policies meaningful to the public. They also facilitate ongoing awareness after the initial news interest has faded. Training in translating findings to different audiences needs to enable epidemiologists to balance between methodological rigor and the need to provide accurate data in a timely fashion. While useful and informative messages can be efficiently communicated via social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, messages of panic and concern, including misleading and false statements, may also be communicated. These platforms have evolving roles in the landscape of journalism and social media. For many, the internet and social media are a source for news. For the average user, considerations of “source” are null, making any piece of information shared on the internet or social media platforms appear as “fact.”

Finally, communication to and for those affected the refugees is of utmost importance during relocations. One of the aims of risk- or health communication is to ensure that relocated populations have access to necessary and accurate information about available services, sources of relief, and policies or laws of their new country [62]. Some challenges may be faced by epidemiologists when attempting to relay messages to these populations. While giving information in lay terms is necessary, language issues may also be a concern. Often the language of the host population will differ from that of the refugee population, making communication via mass media even more difficult. Identification of such challenges, which may also include factors such as values, attitudes and cultural practices, will enable epidemiologists to partner with individuals, organizations, media outlets, and others to develop an appropriate communication strategy and implement effective health communication interventions. These situations, of course, are all country and often refugee specific. As such, one must be cognizant of the fluidity of those re-settlements, as well as the changes in needs of individual refugee populations. Subsequently, these lessons can be used to inform grassroots efforts to study and understand individual refugee populations and derive research and policies accordingly.

Conclusions

By the end of 2015 more than 65 million persons had been displaced from their homes, the highest total displacement ever recorded [63]. This is a world-wide problem that epidemiologists interested in immigrant health can lend their skills and knowledge to address. However, epidemiologists should expand their repertoire of skills to go beyond identification of disease patterns of arriving refugees to also monitor access to quality health care, address inequities and communicate to policy makers. The complexity and uniqueness of refugee health issues requires the use of multidisciplinary teams and development of sustainable management information systems. In addition, epidemiologists face the challenge of the lack of a standard definition of “refugees.” Examination of refugee needs and health care barriers by country of origin could potentially reduce confusion, permit research, and facilitate comparisons across countries and settings.

There has been a gradual shift from health assessment of infectious diseases and mental health status towards chronic diseases and long-term follow up. The level of detail for assessing reproductive health needs varies widely by high income countries, ranging from nonexistent to national guidelines. While it may not be possible to identify all needs in the initial health exam, basic questions on pregnancy or pregnancy intention and contraceptive needs and chronic diseases should be part of a standard assessment. The focus of standard assessments should be on preventable and treatable needs that will be part of follow-up care. When the receiving country does not integrate refugees to the extent of its ability, preventable and treatable illness become health inequities with a high cost to the individual and society. Current data on refugee health have been limited in scope and comprehensiveness. Recent efforts have been made to expand data collection specific to refugees and provide linkages across databases. Understanding the unique health challenges this population faces will allow the development of innovative programming to positively affect refugee health outcomes over the long term.

To explain why it is necessary to allocate resources to this population, researchers need to describe refugees’ mental and physical health risks and vulnerabilities. These descriptions need to be complemented by a description of the communities’ resourcefulness and resilience to cope with adversity so that effective strategies to achieve and preserve health can be developed.

Epidemiologists have a unique skill set for addressing methodological challenges in working with a highly mobile population to produce reliable data that takes account of selection bias, loss to follow-up, lack of comparison groups, missing data points, cross comparisons and adaptions of current monitoring systems. However, epidemiologists can benefit from training in qualitative and participatory research methods to supplement their quantitative training given the interdisciplinary and mixed methods nature of addressing each of these eight lessons. In order to respond to the changing needs of refugee populations and respective contexts (e.g., geography, origin, health care system, laws), epidemiologists need to be flexible and adept in assessing refugee population needs on the ground using informal and formal surveillance methods, as well as formulation of related research and policy questions. In addition, epidemiologists need to be part of a multidisciplinary team and be able to convey at times complex methodological considerations in assessing and evaluating refugee health with researchers and policymakers. With scarce resources, we need to develop rapid response methodologies and surveillance systems that will provide reliable data in a timely fashion. Evaluation of the systems put in place by epidemiologists will ensure the goal of improving the health and quality of life for refugees is met for future generations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge comments from participants of the June 2016 American College of Epidemiology policy committee workshop in Miami, Florida. We also acknowledge travel support from the University of Maryland's School of Public Health (OCP); and the Academic Senate, University of California, San Francisco and an anonymous private foundation (HTB) to attend the workshop. Efforts by Dr. Lorna Thorpe to coordinate the workshop where these case studies were discussed were partially supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Grant U48DP001904. Dr. Bertha Hidalgo is supported by an award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K01 HL130609-01). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

List of abbreviations and acronyms

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CHW

Community Health Worker

- COE-RH

Center of Excellence in Refugee Health

- EDN

Electronic Disease Notification System

- LHA

Lay Health Advisor

- LIDS

Landed Immigrant Data System

- MIPEX

Migrant Integration Policy Index

- PHA

Professional Health Advisor

- UNHCR

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- US

United States

Contributor Information

Heike Thiel de Bocanegra, University of California, San Francisco, Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, 3333 California Street, Suite 335, San Francisco, CA 94118, United States.

Olivia Carter-Pokras, University of Maryland, College Park, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, 2234G SPH Building, 2242 Valley Drive, College Park, Maryland 20742, United States.

J. David Ingleby, University of Amsterdam, Centre for Social Science and Global Health, Nieuwe Achtergracht 166, 1018 WV Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Kevin Pottie, University of Ottawa, Departments of Family Medicine and Epidemiology and Community Medicine, Bruyere Research Institute, 85 Primrose St, Annex E, Ottawa ON K1R 7G5, Canada.

Nedelina Tchangalova, University of Maryland, College Park, Engineering and Physical Sciences Library, 1403 William E. Kirwan Hall, College Park, MD 20742, United States.

Sophia I. Allen, Pennsylvania State University , Department of Public Health Sciences, College of Medicine, MC CH69 500, University Drive, P.O. Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033, United States.

Julie Smith-Gagen, University of Nevada, Reno, School of Community Health Sciences, 1664 N. Virginia Street/MS 274, Reno, NV 8557, United States.

Bertha Hidalgo, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Ryals Public Health Bldg, Suite 220D, Birmingham, AL 35294, United States.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. [accessed 21.03.17];Global trends: forced displacement 2015. 2015 http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html.

- 2.Terasaki G, Ahrenholz NC, Haider MZ. Care of adult refugees with chronic conditions. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(5):1039–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Hungary: assessing health-system capacity to manage sudden, large influxes of migrants. 2016 http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/317131/Hungary-report-assessing-HS-capacity-manage-sudden-large-influxes-migrants.pdf.

- 4.Kärki T, Napoli C, Riccardo F, Fabiani M, Dente MG, Carballo M, et al. Screening for infectious diseases among newly arrived migrants in EU/EEA countries: varying practices but consensus on the utility of screening. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):11004–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111011004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter-Pokras OD, Offutt-Powell TN, Kaufman JS, Giles WH, Mays VM. Epidemiology, policy, and racial/ethnic minority health disparities. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(6):446–55. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis FG, Peterson CE, Bandiera F, Carter-Pokras O, Brownson RC. How do we more effectively move epidemiology into policy action? Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(6):413–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(12):E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Translating epidemiology into policy. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Am Coll Epidemiol. n.d http://www.acepidemiology.org/ACE/Content/Translating_Epidemiology_into_Policy.aspx.

- 9.Crisp J. Research Paper No. 155. Geneva: UNHCR. UNHCR; 2008. [[accessed 21.03.17]]. Beyond the nexus: UNHCR’s evolving perspective on refugee protection and international migration. http://www.unhcr.org/research/working/4818749a2/beyond-nexus-unhcrs-evolving-perspective-refugee-protection-international.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The 1951 Refugee Convention. UNHCR; n.d. [accessed 21.03.17]. http://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carling J. The end of migrants as we know them? [accessed 21.03.17];U N Univ–Maastricht Econ Soc Res Inst Innov Technol UNU-MERIT. 2016 http://www.merit.unu.edu/the-end-of-migrants-as-we-know-them/

- 12.Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Roberts JH, Torres S, DesMeules M. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(12):E952–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed 21.03.17];Guidelines for the US domestic medical examination for newly arriving refugees. n.d http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/domestic-guidelines.html.

- 14.Johnston V. [accessed 21.03.17];Screening guidelines for the initial health assessment of newly arrived refugees in the Northern Territory. 2012 http://digitallibrary.health.nt.gov.au/prodjspui/handle/10137/528.

- 15.Cochrane Methods Equity. [accessed 21.03.17];Migrant health: Migrant Health Subgroup of the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group. n.d http://methods.cochrane.org/equity/migrant-health.

- 16.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Hassan G, Hui C, Kirmayer LJ. Caring for a newly arrived Syrian refugee family. Can Med Assoc J. 2016;188(3):207–11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swinkels H, Pottie K, Tugwell P, Rashid M, Narasiah L. Development of guidelines for recently arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada: Delphi consensus on selecting preventable and treatable conditions. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(12):E928–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiswick BR, Miller PW. Why is the payoff to schooling smaller for immigrants? Labour Econ. 2008;15(6):1317–40. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2008.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omariba DWR, Ng E. Immigration, generation and self-rated health in Canada: on the role of health literacy. Can J Public Health Rev Can Santee Publique. 2011;102(4):281–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03404049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee D, Philen R, Wang Z, McSpadden P, Posey DL, Ortega LS, et al. Disease surveillance among newly arriving refugees and immigrants: Electronic Disease Notification System, United States, 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2013;62(7):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markiewicz B, Baugh K, Tutwiler M, Vazquez J. Refugee health status and healthcare utilization report. Lawton Rhea Chiles Cent Healthy Mothers Babies Univ South Fla; 2009. [accessed 21.03.17]. http://health.usf.edu/publichealth/chilescenter/pdf/Refugee_Health_Status_and_Health_Care_Utilization_Report_final%20101509.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colorado Department of Human Services. [accessed 21.03.17];CDC awards Refugee Services a five-year grant. 2015 https://sites.google.com/a/state.co.us/humanservices/latest-news/cdcawardsrefugeeservicesafive-yeargrant.

- 23.Minnesota Department of Health. Provider update: mental health in Minnesota refugees. Refug Health Q; 2016. [[accessed 21.03.17]]. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/refugee/rhq/rhqjan16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Final report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. 2008 http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/

- 25.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, Wismar M, Cook S. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Health in all policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. 2013 http://www.euro.who.int/en/about-us/partners/observatory/publications/studies/health-in-all-policies-seizing-opportunities,-implementing-policies.

- 26.Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Bremner S, Franciskovic T, Galeazzi GM, Kucukalic A, et al. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):216–23. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silove D, Steel Z, Watters C. Policies of deterrence and the mental health of asylum seekers. JAMA. 2000;284(5):604–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papademetriou DG, Benton M. Towards a whole-of-society approach to receiving and settling newcomers in Europe. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Migrationpolicy.org. 2016 http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/towards-whole-society-approach-receiving-and-settling-newcomers-europe.

- 29.Hjern A. Migration and public health in Sweden: the National Public Health Report 2012. Chapter 13. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(9 suppl):255–67. doi: 10.1177/1403494812459610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ, Ronsmans C, Borghi J. Maternal survival 2: Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. The Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) [[accessed 21.03.17]];Translation and interpretation services. n.d https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financing-and-reimbursement/admin-claiming/translation/index.html.

- 32. [[accessed 21.03.17]];Migrant Integration Policy Index 2015. 2015 http://www.mipex.eu/

- 33. [[accessed 21.03.17]];MRS No. 52 - Summary Report on the MIPEX Health Strand and Country Reports - IOM Online Bookstore. 2016 https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-no-52-summary-report-mipex-health-strand-and-country-reports.

- 34.Ingleby D, Chimienti M, Hatziprokopiou P, Ormond M, De Freitas C. The role of health in integration. In: Fonseca ML, Malheiros J, editors. Social Integration and Mobility: Education, Housing and Health. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos; 2005. [accessed 24.03.17]. pp. 49–65. http://www.ceg.ul.pt/migrare/publ/Cluster%20B5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Like RC, Goode TD. Promoting cultural and linguistic competence in the American health system: levers of change. In: Ingleby D, Krasnik A, Lorant V, Razum O, editors. Inequalities in Health Care for Migrants and Ethnic Minorities. Antwerp/Apeldoorn: Garant; 2012. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, Welch V, Swinkels H, Rashid M, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(3):E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pottie K, Medu O, Welch V, Dahal GP, Tyndall M, Rader T, et al. Effect of rapid HIV testing on HIV incidence and services in populations at high risk for HIV exposure: an equity-focused systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006859. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaves N, Paxton G, Biggs B, Thambiran A, Smith M, Williams J, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive post-arrival health assessment for people from refugee-like backgrounds. Australas Soc Infect Dis Refug Health Netw Aust Guidel Writ Group; 2011. [accessed 21.03.17]. https://www.asid.net.au/documents/item/1225. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bond L, Giddens A, Cosentino A, Cook M, Hoban P, Haynes A, et al. Changing cultures: enhancing mental health and wellbeing of refugee young people through education and training. Promot Educ. 2007;14(3):143–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geltman PL, Cochran J. A private-sector preferred provider network model for public health screening of newly resettled refugees. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):196–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Obaidi A, West B, Fox A, Savin D. Incorporating preliminary mental health assessment in the initial healthcare for refugees in New Jersey. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51(5):567–74. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9862-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kennedy J, Seymour DJ, Hummel BJ. A comprehensive refugee health screening program. Public Health Rep. 1999;114(5):469–77. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakkash RT, Alaouie H, Haddad P, Hajj TE, Salem H, Mahfoud Z, et al. Process evaluation of a community-based mental health promotion intervention for refugee children. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):595–607. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liamputtong P. Doing research in a cross-cultural context: methodological and ethical challenges. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Doing Cross-Cult Res. Springer; Netherlands: 2008. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Percac-Lima S, Milosavljevic B, Oo SA, Marable D, Bond B. Patient navigation to improve breast cancer screening in bosnian refugees and immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):727–30. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeStephano CC, Flynn PM, Brost BC. Somali prenatal education video use in a United States obstetric clinic: a formative evaluation of acceptability. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(1):137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oyebanjo E, Bushell F. A critical evaluation of the UK SunSmart campaign and its relevance to Black and minority ethnic communities. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134(3):144–9. doi: 10.1177/1757913913516288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eide K, Hjern A. Unaccompanied refugee children - vulnerability and agency. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(7):666–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sawyer CB, Márquez J. Senseless violence against Central American unaccompanied minors: historical background and call for help. J Psychol. 2017;151(1):69–75. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1226743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walg M, Fink E, Großmeier M, Temprano M, Hapfelmeier G. Häufigkeit psychischer Störungen bei unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen in Deutschland [Frequency of mental disorders in unaccompanied minors in Germany] Z Für Kinder- Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlson BE, Cacciatore J, Klimek B. A risk and resilience perspective on unaccompanied refugee minors. Soc Work. 2012;57(3):259–69. doi: 10.1093/sw/sws003. sw/swsO03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morland L, Duncan J, Hoebing J, Kirschke J, Schmidt L. Bridging refugee youth and children’s services: a case study of cross-service training. Child Welfare. 2005;84(5):791–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Copley J, Turpin M, Gordon S, McLaren C. Development and evaluation of an occupational therapy program for refugee high school students. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58(4):310–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Lascurain MC, Kicklighter JR, Jonnalagadda SS, Boudolf EA, Duchon D. Effect of a nutrition education program on nutritionrelated knowledge of english-as-second-language elementary school students: a pilot study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(1):57. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-6342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grigg-Saito D, Och S, Liang S, Toof R, Silka L. Building on the strengths of a Cambodian refugee community through community-based outreach. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(4):415–25. doi: 10.1177/1524839906292176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grigg-Saito D, Toof R, Silka L, Liang S, Sou L, Najarian L, et al. Long-term development of a “whole community” best practice model to address health disparities in the Cambodian refugee and immigrant community of Lowell, Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2026–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torres S, Labonté R, Spitzer DL, Andrew C, Amaratunga C. Improving health equity: the promising role of community health workers in Canada. Healthc Policy. 2014;10(1):73–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:477–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fox PG, Rossetti J, Burns KR, Popovich J. Southeast Asian refugee children: a school-based mental health intervention. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res. 2005;11(1):1227–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martijn C, de Vries NK, Voorham T, Brandsma J, Meis M, Hospers HJ. The effects of AIDS prevention programs by lay health advisors for migrants in The Netherlands. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):157–65. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woods LN. Behaviour change communication in emergencies: a toolkit. U N Child Fund; Nepal: 2006. [[accessed 21.03.17]]. https://www.unicef.org/ceecis/BCC_full_pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Connor P, Krogstad JMK. Key facts about the world’s refugees. [[accessed 21.03.17];Pew Res Cent. 2016 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/05/key-facts-about-the-worlds-refugees/