Abstract

Neural stem cells (NSCs) have a unique role in neural regeneration. Cell therapy based on NSC transplantation is a promising tool for the treatment of nervous system diseases. However, there are still many issues and controversies associated with the derivation and therapeutic application of these cells. In this review, we summarize the different sources of NSCs and their derivation methods, including direct isolation from primary tissues, differentiation from pluripotent stem cells and transdifferentiation from somatic cells. We also review the current progress in NSC implantation for the treatment of various neural defects and injuries in animal models and clinical trials. Finally, we discuss potential optimization strategies for NSC derivation and propose urgent challenges to the clinical translation of NSC-based therapies in the near future.

Facts

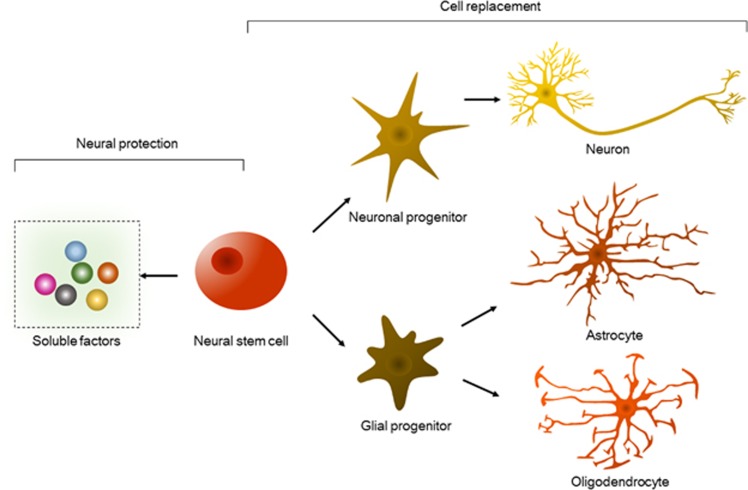

NSCs are a promising treatment modality for diseases associated with the nervous system as they secrete soluble factors and differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.

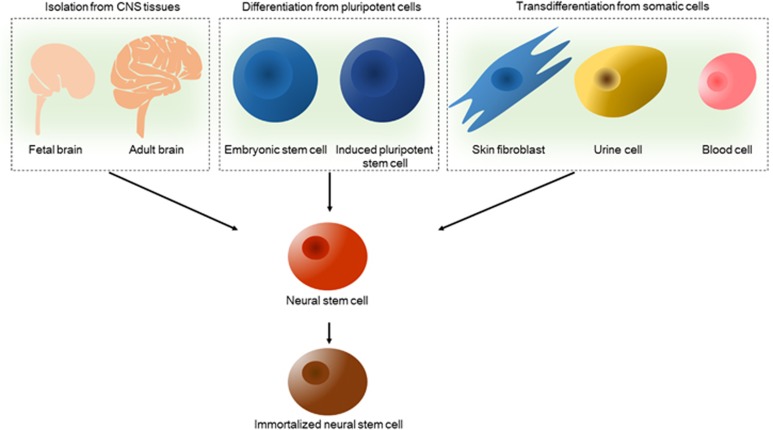

NSCs can be derived from three different sources using recent technical advances: direct isolation from primary tissues, differentiation from pluripotent stem cells and transdifferentiation from somatic cells.

Cell therapies based on NSC transplantation for the treatment of various neural defects and injuries in animal models and clinical trials have been widely investigated.

Open Questions

Which NSC derivation strategy is most efficient and safe for clinical translation?

How can NSC transplantation methods be translated from preclinical studies into clinical trials?

What are the optimization strategies and urgent challenges for the clinical translation of NSC-based therapies in the near future?

Nervous system diseases are refractory diseases that can cause loss of sensation, loss of motor function and memory failure, as well as directly threaten the life of a patient. Currently, the pathogenic factors involved in these diseases and their pathogenesis are unclear. Traditional drug treatments are used to delay disease progression and cannot restore function or regenerate tissues. Recent studies have indicated that the transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) is a promising treatment modality for diseases associated with the nervous system, for the regeneration of neural cells and for the restoration of the microenvironment at the injury site (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NSC properties for therapeutics. NSCs secrete soluble factors, including neurotrophic factors, growth factors and cytokines, thus protecting existing neural cells against damage in situ. Furthermore, they differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes via committed progenitor stages to replace lost neural cells. Either neural protection or cell replacement may aid in neurological functional recovery after acute or chronic injury via neural regeneration

The cell source is the first issue that must be addressed to enable the application of NSCs in clinical treatments because the cell dose required for adequate transplantation is very high. NSCs can be derived from three different sources using recent technical advances, including direct extraction from primary tissues, differentiation from pluripotent stem cells and transdifferentiation from somatic cells (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Sources of NSCs. Using recent technical advances, NSCs can be derived via three diverse methods: direct extraction from primary CNS tissues, including fetal brain, adult brain and spinal cord tissue; differentiation from pluripotent stem cells, such as embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells; and transdifferentiation from somatic cells, such as skin fibroblasts, urine cells and blood cells, which are easily harvested in the clinic. NSCs generated from the above sources can be further immortalized via genetic modification

Table 1. Derivation of neural stem cells.

| Species | Original tissues/cells | Treatment | Duration to derive NSCs | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation from primary tissues | ||||

| Mouse | Striatum | EGF | 1 week | 1 |

| Mouse | Thoracic spinal cord | EGF, bFGF | 1 week | 3 |

| Mouse | Dentate gyrus, SVZ | EGF, bFGF | 1–3 weeks | 4, 10, 11 |

| Mouse | Periventricular region | EGF, bFGF, heparin | 2 weeks | 5 |

| Human and rat | Periventricular region | EGF, bFGF, heparin | 2–3 weeks | 6 |

| Mouse | Olfactory bulb | EGF, bFGF | 1–2 weeks | 7 |

| Human | Olfactory bulb | EGF, bFGF | 1–2 weeks | 8 |

| Mouse | Postnatal cerebellum | EGF, bFGF | 2 weeks | 9 |

| Differentiation from pluripotent stem cells | ||||

| Human | ESCs | Suspension culture | 3–4 weeks | 13 |

| Human | ESCs | Adhesion co-culture with stromal cells MS-5 | 3 weeks | 18 |

| Human | ESCs | Adherent monolayer culture | 3–5 weeks | 20 |

| Human | iPSCs | Suspension and adherent culture | 2–5 weeks | 21 |

| Transdifferentiation from somatic cells | ||||

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc | 2–3 weeks | 24, 25 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | Brn4/Pou3f4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, E47/Tcf3 | 4–5 weeks | 26 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | Foxg1, Sox2, Brn2 | 3–4 weeks | 27 |

| Mouse and human | Fibroblasts | Sox2 | 2–3 weeks | 28 |

| Human | Fibroblasts | ZFP521 | 3–4 weeks | 29 |

| Primate | Fibroblasts | OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, SB431542, CHIR99021 | 2–3 weeks | 30 |

| Human | Fibroblasts | OCT4, A83-01, CHIR99021, NaB, LPA, Rolipram, SP600125 | 4 weeks | 31 |

| Mouse | Sertoli cells | Ascl1, Ngn2, Hes1, Id1, Pax6, Brn2, Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4 | 4–5 weeks | 32 |

| Mouse | Liver cells and B cells | Brn2, Hes1, Hes3, Klf4, c-Myc, Notch1, PLAGL1, Rfx4 | 4–5 weeks | 33 |

| Human | Urine cells | SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC, SV40LT, miR302-367, A83-01, PD0325901, CHIR99021, Thiazovivin, DMH1 | 4–5 weeks | 34 |

| Human | Astrocytes | OCT4, SOX2, NANOG | 2–3 weeks | 35 |

| Human | Cord blood CD34+ cells | OCT4, CHIR99021 | 2–3 weeks | 36 |

| Mouse and human | Fibroblasts, urine cells | VPA, CHIR99021, Repsox | 3 weeks | 37 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | CHIR99021, LDN193189, A83-01, Hh-Ag1.5, Vc, SMER28, RG108, Parnate | 2 weeks | 38 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | VPA, Forskolin, Tranylcypromine, CHIR99021, Repsox, SB431542, Dorsomorphin | 2 weeks | 39 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | VPA, A83-01, Purmorphamine, Vc, NaB, Thiazovivin | 2 weeks | 40 |

| Mouse and human | MSCs | bFGF, EGF | 1–2 weeks | 42, 43 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | bFGF, EGF, heparin, LIF | 3–4 weeks | 45 |

| Mouse | Fibroblasts | 3D sphere culture | NA | 46 |

Abbreviations: bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; 3D, three dimension; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; NA, not available; NaB, sodium butyrate; SVZ, subventricular zone; Vc, ascorbic acid; VPA, valproic acid

Strategies for the Isolation and Generation of NSCs

Isolating and culturing NSCs from primary tissues

The establishment of cell isolation and cell culture techniques has led to the development of favorable experimental methods and the identification of a rich cell source for NSC research. In 1992, Reynolds and Weiss isolated NSCs from the striatum of the adult mouse brain and reported the first use of epidermal growth factor (EGF) to induce NSC proliferation in vitro.1 Two years later, they found that the subependymal region in the mouse brain is the source of NSCs in vivo.2 Based on previous results, Weiss further reported that EGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) cooperatively induce the proliferation, self-renewal and expansion of NSCs isolated from adult mouse thoracic spinal cord.3 NSCs can grow in single-cell suspensions obtained by enzymatic digestion and form spherical clusters called neurospheres, which are non-adherent and can be re-plated in selective culture medium to obtain neural cells.4, 5 Neurospheres can also be sub-cultured to expand the pool of NSCs for experimental or therapeutic purposes. Periventricular regions and olfactory bulb in adult mammalian brains are rich sources of NSCs.6, 7, 8 Beyond these methods of isolating NSCs through diverse culturing strategies, NSCs can also be directly isolated by cell sorting based on the expression of NSC surface markers.9 Belenguer and Guo have developed an optimized protocol for the isolation, culture and expansion of NSCs from mammalian animals.10, 11 Although, a canonical protocol for obtaining human tissue-derived NSCs has not yet been established, the technical methods are generally similar to the ones applied in animals, and the tissues must be obtained in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into NSCs

Pluripotent stem cells, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), can generate desired cells through differentiation, which are attractive alternatives to primary cell isolation. Generally, protocols for neural differentiation from pluripotent stem cells can be categorized into two major routes: embryoid body (EB) formation and monolayer culture.

In the protocol for EB formation, ESC and iPSC colonies are detached and grow in suspension to form EBs. Subsequently, EBs are plated on adhesive substrates with defined serum-free medium that promote the generation of neural tube-like rosettes and the selection of neural progenitor cells (NPCs).12 Zhang et al.13 first described the differentiation, enrichment and transplantation of neural precursor cells from human ESC-derived EBs in vitro. Later, Kozhich et al.14 developed a novel protocol suitable for standardized generation and differentiation of neural precursor cells from human pluripotent stem cells, making iPSC-derived NSCs an appealing source for cell-based therapies.15 Pluripotent stem cells can also directly differentiate into NSCs in monolayer culture via the neural rosettes stage, which is a striking feature here.16, 17, 18 A serum-free and nutrient-poor medium is utilized to initiate differentiation, and depending on the cell line, additional growth factors or inhibitors may be required to promote neural differentiation.19 Banda and Grabel20 have been focusing on using monolayer culture to directly differentiate human ESCs into neural progenitors, which includes four typical stages. Wen and Jin21 have developed a straightforward and useful strategy for the generation of NSCs from both human ESC and iPSC lines. Comparisons of NSC marker expression and morphology have indicated that there are no significant differences between the NSCs derived via EB formation and monolayer culture methods.

Transdifferentiation of somatic cells into NSCs

The term transdifferentiation, also known as lineage reprogramming, was originally coined by Selman and Kafatos in 1974.22 During this process, one type of mature somatic cell transforms into another type of mature somatic cell without undergoing an intermediate pluripotent state.22, 23 This process is induced mainly by the exogenous expression of lineage-specific transcription factors (TFs) and by chemical compounds.

TF-induced transdifferentiation

Ding and others first demonstrated that transient expression of pluripotency factors combined with the appropriate neural signaling inputs can successfully induce mouse fibroblasts to form expandable NSCs,24, 25 which were called induced NSCs (iNSCs). This finding provides a new strategy for the generation of NSCs through direct cell transdifferentiation following virus-mediated exogenous gene expression. Aside from the pluripotency factors, NSC-specific TFs can also induce the generation of neural stem-like cells with self-renewal and tripotent differentiation potential.26, 27 Furthermore, it is found that a single TF, Sox2 or ZFP521, can be used to generate iNSCs from mouse and human fibroblasts.28, 29 Two Chinese teams, led by Zhang and Ding, have separately combined defined TFs with chemical cocktails that enable the generation of expandable iNSCs from both primate and human fibroblasts,30, 31 thus suggesting that small-molecule chemicals can increase the efficiency of iNSC generation. In addition to fibroblasts, many other somatic cell types are considered to be ideal starting cells for NSC generation depending on the clinical situation, including Sertoli cells,32 adult liver cells and B lymphocytes,33 urine epithelial-like cells,34 astrocytes,35 and cord blood sample.36

Chemical compound-induced transdifferentiation

In recent years, researchers have explored chemical reprogramming as a new method to manipulate cell fate. Compared with the conventional practice of importing exogenous viral genes to induce cell transdifferentiation, the use of small-molecule chemicals to elicit cell transdifferentiation has many obvious advantages in terms of safety and controllability.

We were the first to report using only a chemical cocktail containing valproic acid (VPA), CHIR99021 and Repsox, which inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, respectively, to generate chemically induced NPCs (ciNPCs) from mouse embryonic fibroblasts under hypoxic conditions.37 Further assays confirmed that mouse tail-tip fibroblasts and human urinary cells can also be induced into ciNPCs via treatment with the same chemical cocktail. This work demonstrates that direct lineage-specific conversion to NPCs can be achieved without introducing exogenous genes and that physiological hypoxia is essential for the initial transition process. In the absence of hypoxic conditions, Zhang et al.38 developed a cocktail of eight small-molecule components, namely CHIR99021, LDN193189 (an inhibitor of the BMP type I receptor ALK2/3), A83-01 (an inhibitor of the TGF-β type I receptor ALK4/5/7), Hh-Ag1.5 (a potent smoothened agonist), RA, SMER28 (an autophagy modulator), RG108 (a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor) and Parnate (a histone demethylase inhibitor), which can efficiently and specifically transdifferentiate mouse fibroblasts into NSC-like cells. These cells resemble primary NSCs in terms of their long-term self-renewal and tripotent differentiation abilities. Takayama et al.39 also developed a small-molecule cocktail composed of VPA, Forskolin (an adenylyl cyclase activator), Parnate, CHIR99021, Repsox, Dorsomorphin (a selective inhibitor of BMP signaling) and SB431542 (a selective inhibitor of TGF-β receptor I, such as ALK4 and ALK7) to induce neural crest-like precursors from mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Zheng et al.40 showed that a combination of A83-01, Purmorphamine (a smoothened receptor agonist), VPA and Thiazovivin (a selective Rho-associated protein kinase inhibitor) can directly lead to the generation of ciNSCs. Despite these achievements, the mechanisms underlying chemically induced transdifferentiation remain largely unknown. Global gene expression profiles determined through microarray analysis have revealed that the small-molecule-based culture method strongly affects cell identity and specifically induces neural differentiation and development-related genes. Interestingly, small molecules targeting HDACs, GSK-3 and TGF-β are included in most of the abovementioned reports and may constitute the core chemicals. It can be speculated that HDAC inhibitors cause chromatin decondensation and induce cells into a plastic state, TGF-β inhibitors may regulate cell transition between the mesenchymal and epithelial states and promote cell fate conversion, and GSK-3 inhibitors probably activate Wnt signaling, which helps maintain stem cell properties.41

Growth factor or three-dimensional culture-induced transdifferentiation

Regardless of the method used for NSC derivation, growth factors are utilized, which indicate the significance of these factors. Without the introduction of any exogenous genes and chemicals, Feng et al.42 successfully established a three-step induction protocol that generates highly purified neural stem-like cells from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) by activating SOX1 with conditional medium, EGF and bFGF. In addition, Song and Sanchez-Ramos43 proposed a detailed protocol with which to generate neural-like progenitors from bone marrow-derived MSCs and umbilical cord blood-derived MSCs. Later, Ge et al.44 found that cerebrospinal fluid containing growth factors may be a better microenvironment for a more rapid transition of MSCs to a NSC fate. Recently, Gao et al.45 reported a method for neural precursor cell generation from mouse fibroblasts using physical stress and a few growth factors, including EGF, bFGF, leukemia inhibitory factor and heparin, which synergize to regulate the signaling pathways upstream and downstream of Sox2. During this direct induction process, cells first pass through a transient partially reprogrammed state, and then, cell transdifferentiation is achieved via a safe, non-integrated and efficient method.

Given that stem cells reside in specific niches in vivo, a three-dimensional in vitro culture system should mimic the complex physical environment and enhance NSC self-renewal and multipotency compared with traditional two-dimensional culture conditions. Su et al.46 reported that mouse fibroblasts can be converted into three-dimensional spheres on non-adherent substrates and later exhibit the characteristics of neural progenitor-like cells in terms of cell morphology, specific marker expression and self-renewal ability. Immunocytochemical experiments have indicated that the expression of Sox2 is significantly upregulated in three-dimensional cultured mouse fibroblasts. This study has introduced a new paradigm for safer and more convenient cell transdifferentiation using physical tools. This study suggests that other three-dimensional scaffolds might also be used during iNSC generation. For example, graphene foam, a three-dimensional porous scaffold that is biocompatible and conducive to NSC proliferation, has shown great potential for NSC research, neural tissue engineering and neural prostheses.47

Progress in NSC Transplantation for the Treatment of Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are caused by neural or glial cell defects in the brain or spinal cord, which lead to memory deterioration, cognitive disorders, dementia or body movement disorders and mainly include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Huntington’s disease (HD).

ALS is characterized by degeneration and loss of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex, brain stem and spinal cord, thus resulting in muscle wasting, weakness and, eventually, death within 5 years.48 Human NSCs secrete glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which induced the regeneration of motor neurons in a transgenic rat model of ALS.49 Besides, human iPSCs-derived NSCs effectively improve the function of neuromuscular and motor units and significantly increase the lifespan of ALS mice after intrathecal or intravenous injection.50 Beyond the animal models, NSC treatment for ALS has been at the clinical trial stage for years. The clinical results indicate the safety of this therapeutic approach via spinal cord injection.51, 52, 53

PD is a disease characterized by the loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and their terminals in the striatum.54 In toxin-induced animal models of PD, transplanted human NSCs stimulate the dedifferentiation of rat astrocytes and the secretion of exogenous growth factors, thus inhibiting the activation of microglial cells and slowing PD progression by modulating the lesion microenvironment.55, 56 As Lmx1a contributes to NSC differentiation into dopamine neurons, the transplantation of Lmx1a-overexpressing iNSCs markedly enhances the efficiency of dopamine neuron production and elicits therapeutic effects in a PD mouse model.57 Although NSC transplantation in PD animal models has shown a certain degree of benefit,58, 59, 60, 61 additional studies are required to elucidate its clinical efficacy and safety. To date, one report has verified that human parthenogenetic stem cell-derived NSCs (hpNSCs) can successfully engraft, survive long-term and increase dopamine levels in the brains of rodent and nonhuman primate models of PD. In addition, hpNSCs have negligible tumourigenic potential and are safe for clinical application, thus supporting the approval of an hpNSC-based phase I/IIa study for the treatment of PD.62, 63

AD is characterized by increased levels of both soluble and insoluble amyloid beta peptides.64 It has also been reported that hippocampal neuronal mitochondria levels are decreased in AD patients. Transplantation of exogenous NSCs into transgenic AD mice leads to a significant increase in the number of mitochondria and the expression of mitochondria-related proteins, as well as improvements in mouse cognitive function.65 The therapeutic effect of NSC transplantation can be further improved by combining with cerebrolysin controlling amyloid precursor protein metabolism,66 self-assembled peptides providing a protective niche67 and nerve growth factor nanoparticles.68 Human NSCs have also been intensively investigated as an AD treatment in transgenic animal models.69, 70 Although many positive results have been reported based on those models, there were still negative consequences emerged. Marsh et al.71 used an immune-deficient AD model to examine the long-term effects of the transplantation of human NSC products and found that five months after transplantation, human NSCs had engrafted and migrated throughout the hippocampus; however, changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and increases in synaptic density were not observed. The disappointing result of this assay might be due to the failure of the human NSCs to terminally differentiate, which reinforces the notion that candidate cells need to be thoroughly evaluated for safety and efficacy before every transplantation. Considering these inconsistent data, to date, there have been no clinical study of NSC transplantation in AD patient.

HD is an autosomal-dominant inherited disease that induces caudate nucleus atrophy and is characterized by involuntary choreic movements, cognitive impairment and emotional disturbance.72 Animal HD models can be established by injecting quinolinic acid into rodent and primate striatum to simulate excitotoxicity. Human fetal NSCs can differentiate into neurons and astrocytes following transplantation into the rat striatum, partially eliciting behavioral and anatomical recovery in HD rats.73 Furthermore, intracerebral transplantation of NSCs combined with trehalose has been found to not only alleviate polyglutamine aggregation formation and decrease striatal volume but also extend lifespan in transgenic mouse model of HD.74 To further promote the beneficial effects of transplanting NSCs in animal models of HD, the timing of transplantation and cell preparation, NSC activity and co-transplantation of NSCs with helper cells, such as MSCs that secrete brain-derived neurotrophic factor, need to be fully considered based on the pathological conditions.75, 76

Spinal cord injury

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe physical injury and often gives rise to severe loss of motor function and secondary damage.77 There are no effective conventional treatments for SCI, but transplantation of NSCs in a mouse model of SCI leads to significant improvements in motor function recovery, thus indicating that NSCs can survive in vivo, differentiate, and alter the microenvironment of early chronic injury sites.78 In a primate SCI model, transplanted NSCs have been found to differentiate into cells expressing neuronal markers, thereby improving hind limb performance.79 Considering that treatment of SCI with NSCs is regulated by a variety of cytokines and proteins, drugs that modulate these factors will be a helpful adjunctive therapy, such as etanercept having anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects,80 free radical scavenger edaravone,81 and erythropoietin.82 With the rapid development of tissue engineering techniques, biomaterials have gradually been applied to SCI treatment and have provided new prospects for NSC transplantation; for example, biodegradable scaffolds with aligned columns83 and gelatine sponge scaffold.84 In contrast to these positive results, Anderson et al.85 found that human CNS-derived stem cells failed to show preclinical efficacy in a pathway study of cervical SCI. In that study, no evidence of donor cell differentiation into the neuronal lineage was observed. This failure might be attributed to the insufficient characterization of the clinical cell line supplied by the sponsor using potency assays. However, in a phase I/IIa clinical trial on the transplantation of fetal cerebral NSCs into 19 traumatic cervical SCI patients, 17 patients regained sensorimotor function after 1 year, and 2 patients showed complete motor but incomplete sensory recovery. There was no evidence of cord damage; syrinx or tumor formation; neurological deterioration; and exacerbating neuropathic pain or spasticity.86

Stroke

Stroke is an acute cerebrovascular disease that includes ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.87, 88 Transplanted mouse iPSC-derived or human fetus-derived NSC lines have been reported to provide neurotrophic factors and increase angiogenesis and neurogenesis in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke animal models.89, 90 Besides, Li et al.91 demonstrated that compared with transplantation of NPCs alone, co-transplantation with vascular progenitor cells, which might support NPC survival, leads to more effective improvements in neurovascular recovery and attenuation of the infarct volume. Furthermore, the application of three-dimensional electrospun fibers as cell carriers has shown promising results and has been found to extend the survival rate of administered human NSCs by blocking microglial infiltration in an animal model of stroke induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion.92 Despite positive results from animal assays, caution should be exercised before clinical trials, because other findings have suggested that endogenous neurogenesis is decreased after NPC treatment via microglial activation.93 However, in pioneering work, the United Kingdom has already initiated phase I/II clinical trials on the treatment of ischemic stroke with CTX0E03, an immortalized human NSC line.94 Thirteen men were recruited for the phase I trial in which a single dose of up to 20 million cells was implanted via stereotactic ipsilateral putamen injection, and whereas neurological function was improved, no adverse events were observed. Based on the results of the phase I trial, the phase II trial was initiated and is still underway.

Traumatic brain injury

The principal mechanisms of traumatic brain injury (TBI) are classified as focal brain damage and diffuse brain damage, which correspond to contact injury types and acceleration/deceleration injury types.95 TBI is extremely likely to cause cognitive and memory deficits as well as motor impairments. Previous study concluded that NSCs may stabilize the cortical microenvironment after TBI.96 Transplantation of mouse brain-derived NSCs into brain injury mice effectively prevents astroglial activation and microglial/macrophage accumulation while increasing oligodendrocytes and repairing and maintaining normal neuron function.97 A sodium hyaluronate collagen scaffold loaded with bFGF promotes the survival and differentiation of transplanted rat NSCs and promotes functional synapse formation to repair traumatic brain injuries in rats.98 In a clinical study, Zhu’s group labeled autologous cultured NSCs with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and then stereotactically implanted them around the regions of brain trauma in TBI patients. Magnetic resonance imaging tracking images showed the accumulation and proliferation of cells around the lesion and even their migration from the primary sites of injection to the border of the damaged tissue.99

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is an abnormal discharge of cerebral neurons resulting from an imbalance between excitation and inhibition in the CNS; this imbalance leads to transient cerebral dysfunction, which is mainly related to changes in ion channel neurotransmitters and glial cells. Nearly 30% of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) are resistant to antiepileptic drugs. Current reports demonstrate that NSC transplantation can inhibit spontaneous seizures. When transplanted into the epileptic sites of the hippocampus, exogenous NSCs produce a specific type of neuron that synthesizes the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid and astrocytes that secrete anticonvulsant factors, which slow the cognitive and emotional dysfunction caused by TLE.100, 101

Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of permanent movement disorders that appear in early childhood, which is due to the formation of non-progressive lesions in the developing central nervous system.102 At present, CP treatment includes many measures, but none of these treatments can cure CP patients. In recent years, the safety and efficacy of NSC/NPC therapy for CP has been evaluated. Based on current studies, transplantation of NSCs transduced with vascular endothelial growth factor can partially slow brain damage and has neuroprotective effects on neonatal rats with hypoxia-mediated CP, thus suggesting a new potential strategy for CP treatment.103, 104 In clinic, motor development and cognition have been found to be significantly accelerated after aborted fetal tissue-derived NPCs were injected into the lateral ventricle of children with CP.105 Besides, CP patients undergo bone marrow MSC-derived neural stem-like cell transplantation were followed up for long term. Improvements in motor function have been observed following this procedure but not improvements in language quotient, demonstrating that neural stem-like cells derived from autologous MSCs may be a better cell type for CP therapy.106

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a condition that occurs when the entire brain is incompletely deprived of adequate oxygen supply.107, 108 Recent research has shown that mild hypothermia therapy for neonatal encephalopathy via NSC transplantation can attenuate disease progression and prevent long-term damage associated with HIE.109 The ginsenoside Rg1 has been reported to be effective in promoting the recovery of brain function after injury, and thus, Li et al.110 performed ginsenoside-induced NSC transplantation into HIE rats and reported improved behavioral capacity compared with the control group that received only saline, thus presenting a promising new treatment for brain injury. In addition, human embryonic NSC treatment significantly improves learning, memory and cognitive deficits in HIE rat.111 Based on these preclinical studies, much effort is required to translate the NSC transplantation techniques for evaluation in clinical trials involving HIE patients.

Other disorders

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is characterized by a progressive loss of photoreceptors, and it is the leading cause of vision loss.112 Although treatment options for AMD are limited, transplantation of human NPCs into a rodent model of retinal degeneration not only halted the progression of vision loss but also preserved photoreceptors and visual function long term.113, 114 A phase I/II clinical study is investigating the safety and preliminary efficacy of unilateral subretinal transplantation of human NSCs in subjects with geographic atrophy secondary to AMD. In addition, intensive research and development have resulted in a series of NSC products and genetically modified NSCs entering the preclinical study phase and clinical testing phase for the treatment of malignant and non-malignant diseases, such as recurrent high-grade gliomas, metastatic encephaloma and lower limb ischemia (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Treating neurological disorders in animal models via neural stem cell transplantation.

| Disease target | Animal model | Transplanted cell source | Therapeutic mechanism | Outcome | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS | SOD1 (G93A) transgenic rat | Human fetal spinal cord-derived NSCs | Increased glial cell line-derived and brain-derived neurotrophic factors | Improved motor function and extended lifespan | 49 |

| ALS | SOD1 (G93A) transgenic mouse | Human iPSCs-derived NSCs | Increased neurotrophic factors and enhanced gliosis | Improved neuromuscular function and extended lifespan | 50 |

| PD | 6-OHDA-induced mouse | NSCs transdifferentiated from mouse sertoli cells with Lmx1a | Enhanced tyrosine hydroxylase signal and increased endogenous dopaminergic neurons | Improved motor function | 57 |

| PD | MPTP-induced monkey | Human parthenogenetic stem cell-derived NSCs | Increased striatal dopamine concentration, fiber innervation and number of dopaminergic neurons | Promoted behavior recovery | 63 |

| AD | APP/PS1 transgenic mouse | Mouse fetal brain-derived NSCs | Enhanced mitochondria biogenesis | Decreased cognitive deficits | 65 |

| AD | APP transgenic mouse | Mouse cortical NSCs with cerebrolysin | Increased survival of grafted cells | NA | 66 |

| AD | Aβ-induced AD rat | Rat brain-derived NSCs with designer self-assemble peptide | Increased survival and differentiation of the grafted cells, enhanced neuroprotection, anti-neuroinflammatory and paracrine action | Improved behavior recovery | 67 |

| AD | 192IgG-saporin-induced AD rat | Rat fetal brain-derived NSCs with nerve growth factor nanoparticles | Increased basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, hippocampal synapses and AchE-positive fibers | Improved spatial learning and memory | 68 |

| AD | 3x and Thy1-APP transgenic mouse | Neprilysin-modified human NSCs | Decreased Aβ plaques and increased synaptic density and plasticity | Decreased Alzheimer's disease pathology | 69 |

| AD | APP/PS1 transgenic mouse | Human brain-derived NSCs | Enhanced neuronal connectivity and metabolic activity | Improved cognitive, learning and memory, no change in anxiety level | 70 |

| AD | Rag-5xfAD transgenic mouse | Commercial human fetal brain-derived CNS-SCs | No changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor and no increase in synaptic density | Fail to improve learning and memory | 71 |

| HD | R6/2 transgenic mouse | C17.2 NSCs with trehalose | Decreased ubiquitin-positive aggregation, polyglutamine aggregation and striatal volume | Improved motor function, memory performance and survival rate | 74 |

| SCI | Weight drop on mouse | Commercial human fetal brain-derived CNS-SCs | Increased oligodendrocytes and neurons | Improved locomotor recovery | 77 |

| SCI | Weight drop on primate | Adult monkey NSCs | Migration of NSCs to the injury sites | Improved hind limb performance | 79 |

| SCI | Hemisection of rat | Rat fetal brain-derived NSCs with etanercept | Anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis | Re-myelination, neural regeneration and improved locomotor function | 80 |

| SCI | Weight drop on rat | Rat fetal brain-derived NSCs with edaravone | Decreased oxidative damage, increased survival and differentiation of NSCs | Improved rear-limb function | 81 |

| SCI | Hemisection of rat | Rat fetal brain-derived NSCs with biodegradable scaffolds | Improved axonal regeneration | No functional recovery | 83 |

| SCI | Hemisection of rat | Rat brain-derived NSCs-modified by NT-3 and TrkC gene with gelatin sponge scaffold | Increased survival of axotomized neurons and axonal regeneration | Improved partial locomotor functional recovery | 84 |

| SCI | Weight drop on mouse | Commercial human fetal brain-derived CNS-SCs | No neuronal lineage differentiation of donor cells | No functional recovery | 85 |

| Stroke | MCAO in rat | iPSC line-derived NPCs | Enhanced endogenous neurogenesis and angiogenesis and increased trophic factors | Improved functional recovery | 89 |

| Stroke | MCAO in rat | Mouse fetal brain-derived NSCs and and ESCs-derived vascular progenitor cells | Enhanced neurovascular recovery and neurotrophic factors and decreased infarct volume | Improved functional neurological deficits | 91 |

| Stroke | MCAO in rat | Sliding fibers containing human brain-derived NSCs | Increased survival rate of administered NSCs and decreased microglial infiltration | NA | 92 |

| TBI | CCI in mouse | Mouse brain-derived NSCs | Increased oligodendrocytes, decreased astroglial activation and microglial/macrophage accumulation | Delayed spatial learning deficits | 96 |

| TBI | CCI in rat | Sodium hyaluronate collagen scaffold loaded with rat brain-derived NSCs and bFGF | Increased survival and differentiation of NSCs and enhanced functional synapse formation | Improved cognitive function recovery | 98 |

| Epilepsy | Kainic acid-induced rat | Rat embryonic medial ganglionic eminence-derived NSCs | Increased GABAergic neurons and GDNF expression in hippocampal astrocytes | Reduced spontaneous recurrent motor seizures | 101 |

| CP | UCAO plus hypoxia in rat | Rat fetal NSCs transfected with VEGF | Increased VEGF protein expression and decreased neuronal apoptosis | Improved spatial discrimination, learning, memory recall capabilities and locomotor function | 103 |

| CP | UCAO plus hypoxia in rat | Rat fetal NSCs transfected with VEGF | Increased VEGF protein expression and neuroprotection | Improved motor function | 104 |

| HIE | UCAL in neonatal mouse | Mouse fetal brain-derived NSCs with mild hypothermia treatment | Increased survival rate of NSCs, decreased caspase-3, NF-κB and cerebral infarct volumes | Improved functional recovery | 109 |

| HIE | UCAL in neonatal rat | Human fetal brain-derived NSCs with ginsenoside Rg1 | Enhanced latency of somatosensory evoked potentials and increased neurotrophic factors | Improved learning and memory behavior | 110 |

| HIE | Unilateral carotid artery cutting in rat | Human embryonic NSCs | Decreased IL-1β expression, increased NF-κB translocation, reduced brain tissue loss and white matter injury | Alleviated sensorimotor disabilities, improved learning, memory, and cognitive functions | 111 |

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, alzheimer’s disease; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; APP, amyloid precursor protein; CCI, controlled cortical impact; CNS-SCs, central nerve system stem cells; CP, cerebral palsy; C17.2 cells, a murine neural progenitor cell line; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; GDNF, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor; HD, huntington's disease; HIE, neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, used as neurotoxins; NA, not available; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NPCs, neural progenitor cells; NSCs, neural stem cells; 6-OHDA, 6-hydroxydopamine, used as neurotoxins; PD, parkinson's disease; PS1, presenilin 1; Rag-5xfAD mice, an immune-deficient transgenic model exhibited several hallmarks of AD pathogenesis; SCI, spinal cord injury; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TBI, traumatic brain injury; UCAL, unilateral carotid artery ligation; UCAO, unilateral carotid artery occlusion; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Conclusions and Perspectives

NSCs show great plasticity in the treatment of nervous system diseases and can be induced to differentiate into mature neural cells of various types, including neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Under defined conditions, NSCs have a broad differentiation repertoire and can even give rise to non-ectodermal cells, including hematopoietic cells and skeletal myogenic cells.115, 116, 117 In addition, NSCs secrete neurotrophic factors that improve the lesion microenvironment, thereby generating appropriate conditions for pathological repair. The above findings confirm the significant value of NSCs in basic research and in therapeutic applications. The therapeutic effect of NSC transplantation can be further improved with adjuvant pharmaceutical agents, genetic modification, three-dimensional grafts or helper cells, which may improve cell survival and differentiation into specific types of cells.

Initially, NSCs could be obtained only from embryonic brains, and therefore, the limited source, technical issues in isolation and low purity blocked the progression of NSC-based cell therapy. In addition, there were ethical and moral concerns. Currently, emerging technologies continuously improve the methods that can be used to obtain NSCs, especially the identification of ESCs and the development of iPSCs, thus enabling the acquisition of a large number of NSCs and promoting basic research on NSCs. However, the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into NSCs with high purity usually requires a long time and is accompanied by safety issues, thus complicating the translation of this procedure into a clinical therapy. Somatic cell transdifferentiation, especially methods without a viral strategy or integration of exogenous genes such as chemical-, growth factor-, 3D culture- or microRNA-induced cell transdifferentiation,118 into NSCs avoids the previous shortcomings and provides a very attractive strategy for the mass production of NSCs for clinical application.

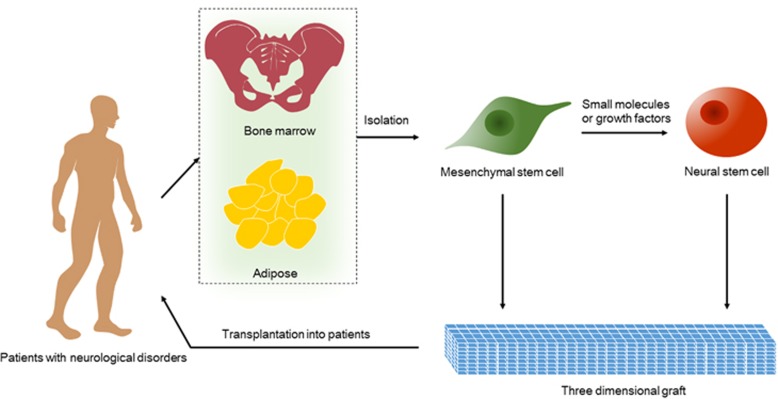

MSCs have great value in regenerative medicine because autologous MSCs are easily harvested and can be effectively induced into a variety of specialized cells, including neural cells. MSC-derived neural stem-like cells have been found to exhibit significant neuroprotective effects.119, 120 In addition, MSCs release paracrine signals that enhance neuronal cell proliferation and the differentiation of human NSCs in vitro in co-culture systems, except for the direct transition of MSCs to neural stem-like cells.121, 122, 123 Moreover, MSCs are a type of immune cell, which can be applied to decrease immune rejection, prolong the survival time of grafts and treat immune dysregulation. Importantly, MSCs alone have been used in many clinical trials for the treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders.59, 124, 125 Co-transplantation of bone marrow MSCs and adult NSCs in a transgenic rat model of HD has been found to confer long-term behavioral benefits and to improve survival of the transplanted NSCs.126 Thus, it should be anticipated that MSC-derived NSC-based therapy with or without MSCs will be a major direction for the treatment of nerve diseases in the future (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic strategies for the derivation and transplantation of NSCs. MSCs are ideal for NSC derivation because of the ease of accessibility from patient bone marrow and especially subcutaneous adipose tissue. NSCs transdifferentiated from plastic MSCs via non-viral and non-genetic methods, such as induction with small molecules or growth factors, are likely safer for clinical application. Transplantation of derived NSCs or co-transplantation of both cells with or without three-dimensional grafts into patents is dependent on disease-specific targets

Although NSC treatment has exhibited some success in a variety of animal disease models, many problems remain to be addressed before transition to clinical applications because of the substantial physiological differences between humans and animals. First, clinical treatments must abide by standardized protocols. Therefore, detailed and efficient standards must be established for therapeutic routines, including stem cell types, the time of transplantation and cell dosage. Purity of NSCs is the priority and needs to be addressed and approved, as contamination of other cells may cause unexpected side effects. The optimal transplantation time for NSCs should be evaluated for each type of acute or chronic disease. Along with others, we have found that even primary tissue-derived NSCs or NPCs can form a clot in vivo if transplanted at high density; thus, the density of transplanted NSCs must be precisely controlled to avoid secondary damages to the injected tissues. Therapeutic routines for NSC administration, including local injection via intracranial or intraspinal routes and systemic injection via intravenous or intrathecal routes, are highly dependent on the lesion site. Second, stem cells that are used as seeds must be verified as safe both in vitro and in vivo. To accomplish this, we suggest carrying out deep sequencing and checking tumor formation potency in mice for every lot of manufactured NSC products. Third, the poor survival rate and the modest treatment effects of NSCs in vivo are major problems that still remain to be solved. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms of stem cell therapy are still unclear, and hence, additional studies are required. Further basic research in related areas may help resolve the above-mentioned issues. Finally, advanced imaging techniques are required to monitor the physiological state of transplanted NSCs in vivo to exclude tumourigenicity and other pitfalls.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Table 3. Clinical trials for neural stem cell transplantation.

| Conditions | Transplanted cells | Status/intervening results | Phase | Location | Start year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS | Spinal cord-derived NSCs | Safe with unilateral and bilateral intraspinal lumbar microinjection | Phase I | United States | 2011 |

| ALS | Spinal cord-derived NSCs | No study results | Phase II | United States | 2012 |

| ALS | Fetal brain-derived NSCs | Improved tibialis anterior | Phase I | Italy | 2012 |

| ALS | CNS10-NPC-GDNF | Recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2016 |

| PD | Parthenogenetic stem cell-derived NSCs | Recruiting | Phase I | Australia | 2015 |

| PD | ESCs-derived NPCs | Recruiting | Phase I/II | China | 2017 |

| PD | Fetal brain-derived NSCs | Invitation | Phase II/III | China | 2017 |

| MS | MSCs-derived NPCs | Active, not recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2013 |

| SCI | Fetal brain-derived NSPCs | Safe and well-tolerated | Phase I/II | Korea | 2005 |

| SCI | MSCs-derived NSCs | Active, not recruiting | Phase I/II | Russia | 2014 |

| SCI | Spinal cord-derived NSCs | Recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2013 |

| SCI | CNS stem cells | Terminated, no study results | Phase II | United States, Canada | 2014 |

| SCI | NSCs combined with Scaffold | Recruiting | Phase I/II | China | 2016 |

| SCI | CNS stem cells | No study results | Phase I/II | Canada, Switzerland | 2011 |

| Stroke | CTX0E03 | Improved neurological function with no adverse events | Phase I | United Kingdom | 2010 |

| Stroke | CTX0E03 | Active, not recruiting | Phase II | United Kingdom | 2014 |

| CP | Fetal brain-derived NPCs | Improvement of functional development and no delayed complications | NA | China | 2005 |

| CP | Fetal brain-derived NSCs | Improvement with varying degrees and no severe adverse reactions | NA | China | 2005 |

| CP | Bone marrow MSCs- derived NSCs-like cells | Optimal improvement in motor function | NA | China | 2010 |

| CP | NSCs | Active, not recruiting | NA | China | 2016 |

| HIE | NPCs with paracrine factors from MSCs | Recruiting | NA | China | 2014 |

| MD | CNS stem cells | No study results | Phase I/II | United States | 2012 |

| LLI | CTX0E03 | Active, not recruiting | Phase I | United Kingdom | 2013 |

| Glioma | NSCs expressing E. Coli CD | No study results | Phase I | United States | 2010 |

| Glioma | NSCs expressing E. Coli CD | Recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2013 |

| Glioma | NSCs expressing Carboxylesterase | Recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2014 |

| Glioma | NSCs loaded with oncolytic adenovirus | Recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2017 |

| GBM | NPCs | Active, not recruiting | Phase I | United States | 2011 |

| IBM | NSCs | Terminated, no study results | Phase III | United States | 2007 |

Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CNS10-NPC-GDNF, human neural progenitor cells secreting glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; CNS, central nerve system; CP, cerebral palsy; CTX0E03, immortalized human neural stem cell line; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; GBM, glioblastoma; HIE, neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; IBM, Intraparenchymal brain metastases; LLI, lower limb ischemia; MD, macular degeneration; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; NPCs, neural progenitor cells; NSCs, neural stem cells; NSPCs, neural stem/progenitor cells; PD, parkinson's disease; SCI, spinal cord injury

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (16QA1402800) and the Technological Innovation Program from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (16XJ11001).

Footnotes

Edited by D Aberdam

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science 1992; 255: 1707–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshead CM, Reynolds BA, Craig CG, McBurney MW, Staines WA, Morassutti D et al. Neural stem cells in the adult mammalian forebrain: a relatively quiescent subpopulation of subependymal cells. Neuron 1994; 13: 1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S, Dunne C, Hewson J, Wohl C, Wheatley M, Peterson AC et al. Multipotent CNS stem cells are present in the adult mammalian spinal cord and ventricular neuroaxis. J Neurosci 1996; 16: 7599–7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari D, Binda E, De Filippis L, Vescovi AL. Isolation of neural stem cells from neural tissues using the neurosphere technique. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 2010; 15: 2D.6.1–2D.6.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azari H, Rahman M, Sharififar S, Reynolds BA. Isolation and expansion of the adult mouse neural stem cells using the neurosphere assay. J Vis Exp 2010; 45: e2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mothe A, Tator CH. Isolation of neural stem/progenitor cells from the periventricular region of the adult rat and human spinal cord. J Vis Exp 2015; 99: e52732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A, Bonfanti L, Doetsch F, Caille I, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA et al. Multipotent neural stem cells reside into the rostral extension and olfactory bulb of adult rodents. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano SF, Impagnatiello F, Girelli M, Cova L, Grioni E, Onofri M et al. Isolation and characterization of neural stem cells from the adult human olfactory bulb. Stem Cells 2000; 18: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Kessler JD, Read TA, Kaiser C, Corbeil D, Huttner WB et al. Isolation of neural stem cells from the postnatal cerebellum. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8: 723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Patzlaff NE, Jobe EM, Zhao X. Isolation of multipotent neural stem or progenitor cells from both the dentate gyrus and subventricular zone of a single adult mouse. Nat Protoc 2012; 7: 2005–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenguer G, Domingo-Muelas A, Ferron SR, Morante-Redolat JM, Farinas I. Isolation, culture and analysis of adult subependymal neural stem cells. Differentiation 2016; 91: 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P, Opitz T, Steinbeck JA, Ladewig J, Brustle O. A rosette-type, self-renewing human ES cell-derived neural stem cell with potential for in vitro instruction and synaptic integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 3225–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, Brustle O, Thomson JA. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2001; 19: 1129–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozhich OA, Hamilton RS, Mallon BS. Standardized generation and differentiation of neural precursor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rev and Rep 2013; 9: 531–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini V, Frati G, Sala D, De Cicco S, Luciani M, Cavazzin C et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived bona fide neural stem cells for ex vivo gene therapy of metachromatic leukodystrophy. Stem Cells Transl Med 2017; 6: 352–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkabetz Y, Studer L. Human ESC-derived neural rosettes and neural stem cell progression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2008; 73: 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PG, Stice SS. Development and differentiation of neural rosettes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev 2006; 2: 67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkabetz Y, Panagiotakos G, Al Shamy G, Socci ND, Tabar V, Studer L. Human ES cell-derived neural rosettes reveal a functionally distinct early neural stem cell stage. Genes Dev 2008; 22: 152–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daadi MM, Maag AL, Steinberg GK. Adherent self-renewable human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cell line: functional engraftment in experimental stroke model. PLoS ONE 2008; 3: e1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda E, Grabel L. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into neural progenitors. Methods Mol Biol 2016; 1307: 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Jin S. Production of neural stem cells from human pluripotent stem cells. J Biotechnol 2014; 188: 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman K, Kafatos FC. Transdifferentiation in the labial gland of silk moths: is DNA required for cellular metamorphosis? Cell Differ 1974; 3: 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature 2009; 462: 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Efe JA, Zhu S, Talantova M, Yuan X, Wang S et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 7838–7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thier M, Worsdorfer P, Lakes YB, Gorris R, Herms S, Opitz T et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts into stably expandable neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 10: 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DW, Tapia N, Hermann A, Hemmer K, Hoing S, Arauzo-Bravo MJ et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into neural stem cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 10: 465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan E, Chanda S, Ahlenius H, Sudhof TC, Wernig M. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to self-renewing, tripotent neural precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 2527–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring KL, Tong LM, Balestra ME, Javier R, Andrews-Zwilling Y, Li G et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse and human fibroblasts into multipotent neural stem cells with a single factor. Cell Stem Cell 2012; 11: 100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi E, Moradi S, Nemati S, Satarian L, Basiri M, Gourabi H et al. Conversion of human fibroblasts to stably self-renewing neural stem cells with a single zinc-finger transcription factor. Stem Cell Rep 2016; 6: 539–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Liu H, Huang CT, Chen H, Du Z, Liu Y et al. Generation of integration-free and region-specific neural progenitors from primate fibroblasts. Cell Rep 2013; 3: 1580–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Ambasudhan R, Sun W, Kim HJ, Talantova M, Wang X et al. Small molecules enable OCT4-mediated direct reprogramming into expandable human neural stem cells. Cell Res 2014; 24: 126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C, Zheng Q, Wu J, Xu Z, Wang L, Li W et al. Direct reprogramming of Sertoli cells into multipotent neural stem cells by defined factors. Cell Res 2012; 22: 208–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassady JP, D'Alessio AC, Sarkar S, Dani VS, Fan ZP, Ganz K et al. Direct lineage conversion of adult mouse liver cells and B lymphocytes to neural stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 2014; 3: 948–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang L, Huang W, Su H, Xue Y, Su Z et al. Generation of integration-free neural progenitor cells from cells in human urine. Nat Methods 2013; 10: 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti S, Nizzardo M, Simone C, Falcone M, Donadoni C, Salani S et al. Direct reprogramming of human astrocytes into neural stem cells and neurons. Exp Cell Res 2012; 318: 1528–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Huang N, Yu J, Jares A, Yang J, Zieve G et al. Direct conversion of cord blood CD34+ cells into neural stem cells by OCT4. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015; 4: 755–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Hu W, Qiu B, Zhao J, Yu Y, Guan W et al. Generation of neural progenitor cells by chemical cocktails and hypoxia. Cell Res 2014; 24: 665–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Lin YH, Sun YJ, Zhu S, Zheng J, Liu K et al. Pharmacological reprogramming of fibroblasts into neural stem cells by signaling-directed transcriptional activation. Cell Stem Cell 2016; 18: 653–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama Y, Wakabayashi T, Kushige H, Saito Y, Shibuya Y, Shibata S et al. Brief exposure to small molecules allows induction of mouse embryonic fibroblasts into neural crest-like precursors. FEBS Lett 2017; 591: 590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Choi KA, Kang PJ, Hyeon S, Kwon S, Moon JH et al. A combination of small molecules directly reprograms mouse fibroblasts into neural stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016; 476: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A, Cheng L. Chemical transdifferentiation: closer to regenerative medicine. Front Med 2016; 10: 152–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N, Han Q, Li J, Wang S, Li H, Yao X et al. Generation of highly purified neural stem cells from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by Sox1 activation. Stem Cells Dev 2014; 23: 515–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Sanchez-Ramos J. Preparation of neural progenitors from bone marrow and umbilical cord blood. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 438: 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W, Ren C, Duan X, Geng D, Zhang C, Liu X et al. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into neural stem cells using cerebrospinal fluid. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015; 71: 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Xiu W, Zhang L, Zang R, Yang L, Wang C et al. Direct induction of neural progenitor cells transiently passes through a partially reprogrammed state. Biomaterials 2017; 119: 53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su G, Zhao Y, Wei J, Xiao Z, Chen B, Han J et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts into neural progenitor-like cells by forced growth into 3D spheres on low attachment surfaces. Biomaterials 2013; 34: 5897–5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang Q, Gao S, Song Q, Huang R, Wang L et al. Three-dimensional graphene foam as a biocompatible and conductive scaffold for neural stem cells. Sci Rep 2013; 3: 1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen AA, Hudson AJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: concepts in pathogenesis and etiology. Can J Neurol Sci 1987; 14: 649–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Yan J, Chen D, Welsh AM, Hazel T, Johe K et al. Human neural stem cell grafts ameliorate motor neuron disease in SOD-1 transgenic rats. Transplantation 2006; 82: 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizzardo M, Simone C, Rizzo F, Ruggieri M, Salani S, Riboldi G et al. Minimally invasive transplantation of iPSC-derived ALDHhiSSCloVLA4+ neural stem cells effectively improves the phenotype of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model. Hum Mol Genet 2014; 23: 342–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley J, Glass J, Feldman EL, Polak M, Bordeau J, Federici T et al. Intraspinal stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase I trial, cervical microinjection, and final surgical safety outcomes. Neurosurgery 2014; 74: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman EL, Boulis NM, Hur J, Johe K, Rutkove SB, Federici T et al. Intraspinal neural stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: phase 1 trial outcomes. Ann Neurol 2014; 75: 363–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L, Gelati M, Profico DC, Sgaravizzi G, Projetti Pensi M, Muzi G et al. Human neural stem cell transplantation in ALS: initial results from a phase I trial. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agid Y. Parkinson's disease: pathophysiology. Lancet 1991; 337: 1321–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara T, Matsukawa N, Hara K, Yu G, Xu L, Maki M et al. Transplantation of human neural stem cells exerts neuroprotection in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 12497–12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo FX, Bao XJ, Sun XC, Wu J, Bai QR, Chen G et al. Transplantation of human neural stem cells in a parkinsonian model exerts neuroprotection via regulation of the host microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16: 26473–26492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Sheng C, Liu Z, Jia W, Wang B, Li M et al. Lmx1a enhances the effect of iNSCs in a PD model. Stem Cell Res 2015; 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond DE Jr., Vinuela A, Kordower JH, Isacson O. Influence of cell preparation and target location on the behavioral recovery after striatal transplantation of fetal dopaminergic neurons in a primate model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2008; 29: 103–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramana NK, Kumar SK, Balaraju S, Radhakrishnan RC, Bansal A, Dixit A et al. Open-labeled study of unilateral autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Transl Res 2010; 155: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Goetz CG, Kordower JH, Stoessl AJ, Sossi V, Brin MF et al. A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 2003; 54: 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lige L, Zengmin T. Transplantation of neural precursor cells in the treatment of parkinson disease: an efficacy and safety analysis. Turk Neurosurg 2016; 26: 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garitaonandia I, Gonzalez R, Christiansen-Weber T, Abramihina T, Poustovoitov M, Noskov A et al. Neural stem cell tumorigenicity and biodistribution assessment for phase I clinical trial in Parkinson's disease. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 34478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Garitaonandia I, Poustovoitov M, Abramihina T, McEntire C, Culp B et al. Neural stem cells derived from human parthenogenetic stem cells engraft and promote recovery in a nonhuman primate model of Parkinsons disease. Cell Transplant 2016; 25: 1945–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 2002; 297: 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Gu GJ, Shen X, Zhang Q, Wang GM, Wang PJ. Neural stem cell transplantation enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease-like pathology. Neurobiol Aging 2015; 36: 1282–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockenstein E, Desplats P, Ubhi K, Mante M, Florio J, Adame A et al. Neuro-peptide treatment with cerebrolysin improves the survival of neural stem cell grafts in an APP transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Stem Cell Res 2015; 15: 54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui GH, Shao SJ, Yang JJ, Liu JR, Guo HD. Designer self-assemble peptides maximize the therapeutic benefits of neural stem cell transplantation for Alzheimer's disease via enhancing neuron differentiation and paracrine action. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53: 1108–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Pan C, Xuan A, Xu L, Bao G, Liu F et al. Treatment efficacy of NGF nanoparticles combining neural stem cell transplantation on Alzheimer's disease model rats. Med Sci Monit 2015; 21: 3608–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, Spencer B, Michael S, Castello NA, Agazaryan AA, Davis JL et al. Neural stem cells genetically-modified to express neprilysin reduce pathology in Alzheimer transgenic models. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014; 5: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhu H, Sun X, Zuo F, Lei J, Wang Z et al. Human neural stem cell transplantation rescues cognitive defects in APP/PS1 model of Alzheimer's disease by enhancing neuronal connectivity and metabolic activity. Front Aging Neurosci 2016; 8: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh SE, Yeung ST, Torres M, Lau L, Davis JL, Monuki ES et al. HuCNS-SC human NSCs fail to differentiate, form ectopic clusters, and provide no cognitive benefits in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Stem Cell Rep 2017; 8: 235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachoud-Levi AC, Remy P, Nguyen JP, Brugieres P, Lefaucheur JP, Bourdet C et al. Motor and cognitive improvements in patients with Huntington's disease after neural transplantation. Lancet 2000; 356: 1975–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride JL, Behrstock SP, Chen EY, Jakel RJ, Siegel I, Svendsen CN et al. Human neural stem cell transplants improve motor function in a rat model of Huntington's disease. J Comp Neurol 2004; 475: 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CR, Yu RK. Intracerebral transplantation of neural stem cells combined with trehalose ingestion alleviates pathology in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci Res 2009; 87: 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johann V, Schiefer J, Sass C, Mey J, Brook G, Kruttgen A et al. Time of transplantation and cell preparation determine neural stem cell survival in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Exp Brain Res 2007; 177: 458–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JK, Kim J, Cho SJ, Hatori K, Nagai A, Choi HB et al. Proactive transplantation of human neural stem cells prevents degeneration of striatal neurons in a rat model of Huntington disease. Neurobiol Dis 2004; 16: 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RC, Thompson JM, Bebin J. The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1958; 21: 216–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar DL, Uchida N, Hamers FP, Cummings BJ, Anderson AJ. Human neural stem cells differentiate and promote locomotor recovery in an early chronic spinal cord injury NOD-scid mouse model. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati SN, Jabbari R, Hajinasrollah M, Zare Mehrjerdi N, Azizi H, Hemmesi K et al. Transplantation of adult monkey neural stem cells into a contusion spinal cord injury model in rhesus macaque monkeys. Cell J 2014; 16: 117–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wei FX, Cen JS, Ping SN, Li ZQ, Chen NN et al. Early administration of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist promotes survival of transplanted neural stem cells and axon myelination after spinal cord injury in rats. Brain Res 2014; 1575: 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YY, Peng CG, Ye XB. Combination of edaravone and neural stem cell transplantation repairs injured spinal cord in rats. Genet Mol Res 2015; 14: 19136–19143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zuo Y, Wang XL, Huo HJ, Jiang JM, Yan HB et al. Effect of neural stem cell transplantation combined with erythropoietin injection on axon regeneration in adult rats with transected spinal cord injury. Genet Mol Res 2015; 14: 17799–17808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson HE, Rooney GE, Gross L, Nesbitt JJ, Galvin KE, Knight A et al. Neural stem cell- and Schwann cell-loaded biodegradable polymer scaffolds support axonal regeneration in the transected spinal cord. Tissue Eng Part A 2009; 15: 1797–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du BL, Zeng X, Ma YH, Lai BQ, Wang JM, Ling EA et al. Graft of the gelatin sponge scaffold containing genetically-modified neural stem cells promotes cell differentiation, axon regeneration, and functional recovery in rat with spinal cord transection. J Biomed Mater Res A 2015; 103: 1533–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AJ, Piltti KM, Hooshmand MJ, Nishi RA, Cummings BJ. Preclinical efficacy failure of human CNS-derived stem cells for use in the pathway study of cervical spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Rep 2017; 8: 249–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JC, Kim KN, Yoo J, Kim IS, Yun S, Lee H et al. Clinical trial of human fetal brain-derived neural stem/progenitor cell transplantation in patients with traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Neural Plast 2015; 2015: 630932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci 1999; 22: 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diringer MN. Intracerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology and management. Crit Care Med 1993; 21: 1591–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau MJ, Deveau TC, Song M, Gu X, Chen D, Wei L. iPSC Transplantation increases regeneration and functional recovery after ischemic stroke in neonatal rats. Stem Cells 2014; 32: 3075–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Kim KS, Kim EJ, Choi HB, Lee KH, Park IH et al. Brain transplantation of immortalized human neural stem cells promotes functional recovery in mouse intracerebral hemorrhage stroke model. Stem Cells 2007; 25: 1204–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tang Y, Wang Y, Tang R, Jiang W, Yang GY et al. Neurovascular recovery via co-transplanted neural and vascular progenitors leads to improved functional restoration after ischemic stroke in rats. Stem Cell Rep 2014; 3: 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Yun S, Park KI, Jang JH. Sliding fibers: slidable, injectable, and gel-like electrospun nanofibers as versatile cell carriers. ACS Nano 2016; 10: 3282–3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnerup J, Kim JB, Schmidt A, Diederich K, Bauer H, Schilling M et al. Effects of neural progenitor cells on sensorimotor recovery and endogenous repair mechanisms after photothrombotic stroke. Stroke 2011; 42: 1757–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalladka D, Sinden J, Pollock K, Haig C, McLean J, Smith W et al. Human neural stem cells in patients with chronic ischaemic stroke (PISCES): a phase 1, first-in-man study. Lancet 2016; 388: 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon KJ, Theus MH, Nelersa CM, Mier J, Travieso LG, Yu TS et al. Endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells stabilize the cortical microenvironment after traumatic brain injury. Neurotrauma 2015; 32: 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoudaki PN, Papastefanaki F, Stamatakis A, Kouroupi G, Xingi E, Stylianopoulou F et al. Neural stem/progenitor cells differentiate into oligodendrocytes, reduce inflammation, and ameliorate learning deficits after transplantation in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Glia 2016; 64: 763–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Li X, Wang C, Hao P, Song W, Li M et al. Functional hyaluronate collagen scaffolds induce NSCs differentiation into functional neurons in repairing the traumatic brain injury. Acta Biomater 2016; 45: 182–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Zhou L, XingWu F. Tracking neural stem cells in patients with brain trauma. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2376–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldau B, Hattiangady B, Kuruba R, Shetty AK. Medial ganglionic eminence-derived neural stem cell grafts ease spontaneous seizures and restore GDNF expression in a rat model of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Stem Cells 2010; 28: 1153–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK. Neural stem cell therapy for temporal lobe epilepsy. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV (eds). Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. Oxford University Press Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2012, pp1098–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Bax MC. Terminology and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1964; 6: 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng XR, Zhang SS, Yin F, Tang JL, Yang YJ, Wang X et al. Neuroprotection of VEGF-expression neural stem cells in neonatal cerebral palsy rats. Behav Brain Res 2012; 230: 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Zheng X, Zhang S, Yang Y, Wang X, Yu X et al. Response of the sensorimotor cortex of cerebral palsy rats receiving transplantation of vascular endothelial growth factor 165-transfected neural stem cells. Neural Regen Res 2014; 9: 1763–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan Z, Liu W, Qu S, Du K, He S, Wang Z et al. Effects of neural progenitor cell transplantation in children with severe cerebral palsy. Cell Transplant 2012; 21(Suppl 1): S91–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Wang Y, Xu Z, Fang F, Xu R, Wang Y et al. Neural stem cell-like cells derived from autologous bone mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of patients with cerebral palsy. J Transl Med 2013; 11: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann AW Jr.. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (asphyxia). Pediatr Clin North Am 1986; 33: 451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston MV. Hypoxic-Ischemic encephalopathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2000; 2: 109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Jiang F, Li Q, He X, Ma J. Mild hypothermia combined with neural stem cell transplantation for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: neuroprotective effects of combined therapy. Neural Regen Res 2014; 9: 1745–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YB, Wang Y, Tang JP, Chen D, Wang SL. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1-induced neural stem cell transplantation on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neural Regen Res 2015; 10: 753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Liu M, Zhao XF, Liu XY, Guo QL, Guan ZF et al. NF-kappaB signaling is involved in the effects of intranasally engrafted human neural stem cells on neurofunctional improvements in neonatal rat hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. CNS Neurosci Ther 2015; 21: 926–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1432–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin M, Szirth B. Current treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Optom Vis Sci 2007; 84: 559–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MK, Lu B, Saghizadeh M, Wang S. Gene expression changes in the retina following subretinal injection of human neural progenitor cells into a rodent model for retinal degeneration. Mol Vis 2016; 22: 472–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson CR, Rietze RL, Reynolds BA, Magli MC, Vescovi AL. Turning brain into blood: a hematopoietic fate adopted by adult neural stem cells in vivo. Science 1999; 283: 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli R, Borello U, Gritti A, Minasi MG, Bjornson C, Coletta M et al. Skeletal myogenic potential of human and mouse neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci 2000; 3: 986–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DL, Johansson CB, Wilbertz J, Veress B, Nilsson E, Karlstrom H et al. Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells. Science 2000; 288: 1660–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Zhang L, An J, Zhang Q, Liu C, He B et al. MicroRNA-mediated reprogramming of somatic cells into neural stem cells or neurons. Mol Neurobiol 2017; 54: 1587–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang Y, Kong J, Dong M, Duan H, Chen S. Therapeutic efficacy of neural stem cells originating from umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nivet E, Vignes M, Girard SD, Pierrisnard C, Baril N, Deveze A et al. Engraftment of human nasal olfactory stem cells restores neuroplasticity in mice with hippocampal lesions. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 2808–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Park HJ, Han S, Lee J, Ko E, Kim J et al. Recapitulation of in vivo-like paracrine signals of human mesenchymal stem cells for functional neuronal differentiation of human neural stem cells in a 3D microfluidic system. Biomaterials 2015; 63: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft AP, Przyborski SA. Mesenchymal stem cells expressing neural antigens instruct a neurogenic cell fate on neural stem cells. Exp Neurol 2009; 216: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Tu W, Lou Y, Xie A, Lai X, Guo F et al. Mesenchymal stem cells regulate the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells through Notch signaling. Cell Biol Int 2009; 33: 1173–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L, Ferrero I, Luparello V, Rustichelli D, Gunetti M, Mareschi K et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase I clinical trial. Exp Neurol 2010; 223: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Venkataramana NK, Bansal A, Balaraju S, Jan M, Chandra R et al. Ex vivo-expanded autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in human spinal cord injury/paraplegia: a pilot clinical study. Cytotherapy 2009; 11: 897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]