Abstract

Aim:

This study aims to investigate the root canal anatomy of human extracted permanent maxillary anterior teeth in patients reporting to our dental institution in Chennai using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 285 maxillary anterior teeth comprising of 100 central incisors, 85 lateral incisors, and 100 canines extracted from various patients reporting to our institution were studied. The number of roots and number of canals were assessed; following which, the root canal anatomy of each tooth was evaluated for the canal pattern using CBCT. The collected data were analyzed using IBM. SPSS statistics software 23.0 version.

Results:

All the teeth examined were observed to be single rooted. All maxillary central incisors displayed Type I (100%) pattern whereas maxillary laterals and canines displayed canal variations. In maxillary laterals, Type I pattern (98%) was most prevalent followed by Type II (2%) configuration. Maxillary canines revealed a predominant Type I (96%) canal pattern followed by Type II (3%) and Type III (1%).

Conclusion:

A varied root canal anatomy was observed in maxillary anterior teeth among Chennai urban population in this institutional-based study. The most frequent canal pattern reported in the maxillary anterior dentition was Type I. Type II was observed in both maxillary lateral incisors and maxillary canines whereas Type III canal configuration was reported only in maxillary canines.

KEYWORDS: Anterior teeth, canal pattern, cone beam computed tomography, Indian population, root canal anatomy

INTRODUCTION

Complete debridement of the root canal system is one of the most important factors affecting the success of endodontic treatment.[1] However, many roots possess additional canals and a variety of other canal configurations which are not very unusual and are considered normal.[2] Hence, a comprehensive understanding of the root canal morphology and its aberrations is an essential prerequisite.[3] There have been numerous studies assessing the root canal anatomy over the years; from the early work of Hess and Zurcher to the most recent technologically advanced studies demonstrating complexities of the entire pulp canal space, and all these have concluded that a single root canal exiting as a single foramen is occasionally reported.[4,5] Unobserved and unfilled canals may continue to harbor bacteria and can lead to post-endodontic infection. Therefore, a thorough knowledge of the various root canal configurations aids the clinician to negotiate and debride the canals efficiently and thus provides a successful endodontic outcome.

It is well known that the morphology of root canal system varies with race, gender, and population.[4,5,6,7] Earlier studies pertaining to the morphology of root canals are most commonly reported in American, Turkish, Ugandan, Sudanese, Caucasian, Chinese, and Sri Lanka population.[7,8,9,10] Starting from the Caucasians to the Africans and Asians, root canal anatomy patterns follow a racial characteristic making endodontic treatment more challenging for the clinicians.[7,9,10,11,12,13,14]

In recent years, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) has become an effective tool in successfully exploring the root canal anatomy. Neelakantan et al. also reported that CBCT is as accurate as modified canal staining and clearing technique, which is the gold standard in the assessment of the root canal anatomy.[15]

Practitioners who regularly treat different population origins should be aware of racial differences and their influence on root canal morphological variations. A recent study by Mohammadzadeh Akhlaghi et al. also revealed that there are variations in the root canal anatomy and morphology of mandibular first molars which was conducted in a selected Iranian Population.[16] However, a careful review of literature revealed that studies pertaining to root canal morphology of maxillary anterior teeth among the Indian population are rarely reported. Although Somalinga Amardeep et al. in a study reported the root canal morphology of maxillary and mandibular canines in Indian population, root canal variations of maxillary anterior teeth per se are not studied earlier.[17] On the contrary, root canal anatomy of premolars and molars in Indian population has been extensively investigated. For instance, Gupta et al. (2015) reported that there is an increased propensity of morphological variations in the root and canal morphology of maxillary first premolar in North Indian population.[18] A recent study by Singh and Pawar et al. (2015) also revealed the root canal morphology of South Asian Indian maxillary molars and the authors had concluded that a varied root canal anatomy was evident in the mesiobuccal root of maxillary molars.[19] Hence, the present preliminary institutional-based study in Chennai city, India, was attempted to investigate the internal root canal anatomy and external root morphology of human-extracted permanent maxillary anterior teeth in a representative Indian population using CBCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an in vitro, experimental study in which two hundred and eighty-five human permanent maxillary anterior teeth extracted for periodontal reasons from various patients reporting to the outpatient ward of Meenakshi Ammal Dental College and Hospital, from July 2014 to May 2015 in Chennai, India, were studied. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of MAHER University, India (Ethical approval No: MADC/IRB/2014/047B). Those patients who were nonresidents of India were not considered for this study. In addition, teeth with deep caries, cracks, fracture, incompletely formed root apices, and those with root canal fillings were excluded from the study. All teeth were cleaned free of attached calculus and soft tissue using ultrasonic scalers and curette and were then preserved in 10% formalin until use.

The crown and root length of all the maxillary anterior teeth were assessed before CBCT evaluation. The number of roots was also noted. The crown length was determined by measuring the distance between the incisal edge to the height of cementoenamel junction (CEJ) on the labial aspect whereas the length of the root was measured from CEJ to the root apex. All the specimens were then subjected to CBCT evaluation to assess the various morphological parameters such as the number of roots, number of canals, and type of canal configuration. The collected data were then analyzed using IBM. SPSS statistics software 23.0 version (Armonk, NewYork, United States).

CONE BEAM COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY EVALUATION

All the teeth were dried and mounted longitudinally on a modeling wax sheet (The Hindustan Dental Products Pvt Ltd. India). Then, the teeth were scanned by a CBCT scanner (Sirona Dental System) using SICAT Galileo Implant version 1.8 software. The three-dimensional (3D) resolution (isotropic voxel size) was about 0.3 mm, and the spherical imaging volume was 15 cm with a magnification set at 1:1 ratio along with a reconstruction time of 2.5–4.5 s. The scan setting was done at 85 kVp, 42 mAs with an exposure time of 14 s. The software was also used for volumetric rendering of the 3D images through selective integration and measurement of adjacent voxels (all voxels are isotropic) in the display. The objects within the volume were then accurately measured in different directions.

The images generated by CBCT system were processed and then analyzed for the morphological evaluation. The pattern of the root canals was assessed and classified according to Vertucci's root canal classification system.[8] Additional patterns (observed, if any) were classified based on Sert and Bayirli's classification.[7]

The canal configurations were categorized into the following eight types based on Vertucci's classification:[8]

Type I. A single canal extends from the pulp chamber to the apex (1)

Type II. Two separate canals exit the pulp chamber and join short of the apex to form a single canal (2-1)

Type III. One canal leaves the pulp chamber, divides into two within the root, and then merges to exit as a main canal (1-2-1)

Type IV. Two separate and distinct canals are present throughout the extent from pulp chamber to the apex (2)

Type V. Single canal exits the pulp chamber but divides into two distinct canals with two distinct apical foramina (1-2)

Type VI. Two distinct canals leave the pulp chamber but join at the midpoint and divides again into two distinct canals with two separate apical foramina (2-1-2)

Type VII. Single canal exits the pulp chamber, divides and rejoins within the canal, and finally redivides into two distinct canals short of the apex (1-2-1-2)

Type VIII. Three distinct root canals exit the pulp chamber extending till the root apex (3).

RESULTS

NUMBER OF ROOTS

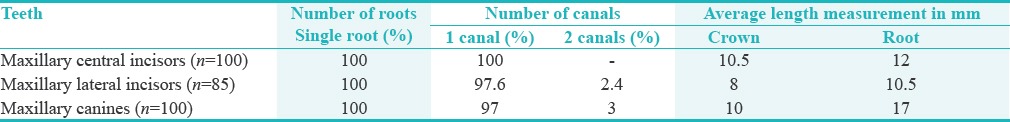

All the teeth examined were observed to be single rooted [Table 1].

Table 1.

Assessment of various morphological variations including number of roots, number of canals, and the type of canal configuration in permanent maxillary anterior teeth among our institutional-based study in Chennai population

NUMBER OF CANALS

Among the anterior teeth studied, all the maxillary central incisors displayed a single root canal whereas maxillary lateral incisors and maxillary canines demonstrated canal variations [Table 1].

CANAL PATTERN

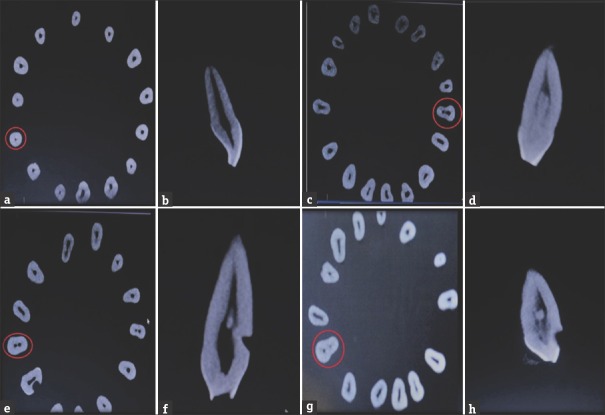

CBCT scanned images of the canal anatomy of the maxillary anterior teeth are depicted in Figure 1. All maxillary central incisors (100%) revealed Type I canal configuration [Figure 1a and b]. In maxillary lateral incisors [Figure 1c and d], Type I canal pattern (98%) was most prevalent followed by Type II (2%) configuration. Maxillary canines revealed a canal configuration with a predominant Type I (96%) pattern followed by Type II [Figure 1e and f] and Type III [Figure 1g and h] in 3% and 1% of the respective samples studied.

Figure 1.

Cone beam computed tomography images of root canal anatomy of maxillary anterior teeth among Chennai population studied. Cross-sectional (a) and axial views (b) of maxillary central incisors depicting Type I canal pattern; cross-sectional (c) and axial views (d) of maxillary lateral incisors depicting Type II canal pattern; cross-sectional (e) and axial views (f) of maxillary canines depicting Type II canal pattern; cross-sectional (g) and axial views (h) of maxillary canines depicting Type III canal pattern

DISCUSSION

Numerous researchers worldwide have been studying the root canal anatomy for a century now. It is well known that the morphology of root canal system varies with race, gender, and population.[4,5,6,7] Earlier studies pertaining to the root canal anatomy are most commonly reported in American, Ugandan, Turkish, Sudanese, Caucasian, Chinese and Sri Lanka population.[7,8,9,10] Starting from the Caucasians to the Africans and Asians, the patterns of root canal system follow a racial characteristic making endodontic management extremely challenging to the clinical practitioners.[18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] The various root canal anatomies constituting apical exit of the canal, apical deltas, lateral canals, intercanal anastomoses, and canal designs with their complexities itself, provide conducive environments for microbial colonization resulting in periapical infections, whose successful elimination plays a major influence in the treatment outcome.[1] Finally, it becomes the responsibility of the endodontist to rid these canals constituting of microbial biofilms with adequate canal cleaning and shaping techniques along with the effective use of appropriate irrigants and medicaments. Hence, a thorough knowledge of the root canal anatomy will only facilitate the clinicians to achieve this goal, thereby resulting in a drastic reduction in post-treatment failure rates. Studies on the root canal morphology of anterior teeth in the Indian population are very limited. Somalinga Amardeep et al. studied the root canal anatomy of maxillary and mandibular canines among the Indian population and reported canal variations.[17] However, root canal morphology of central and lateral incisors amidst Indian population have not been reported earlier. Hence, this institutional-based study in Chennai urban population (India) was in an attempt to assess the root canal variations of permanent maxillary anterior teeth using CBCT.

Various methodologies employed for assessing the root canal anatomy in extracted teeth include histopathological sections, regular radiographic imaging, contrast medium-enhanced radiographic techniques, modified canal staining and clearing technique and Dental Operating Surgical Microscope (DOM).[8,9,18,19,20,21] Most of these methods involve an invasive procedure which might alter the actual root canal morphology. However, an ideal technique would be one that is accurate, simple, nondestructive, and most importantly, feasible in an in vivo scenario, as stated by Mao and Neelakantan.[22] Conventional radiographic imaging is essentially 2D imaging of a 3D object. Furthermore, the interpretation of radiographs can be influenced by several confounding factors, including regional anatomy and superimposition of teeth and the surrounding dentoalveolar structures. The structures visualized by radiographs are also subject to geometric distortions.[23] However, these problems can be overcome by the use of advanced modes of radiographic imaging and analysis which have allowed for in-depth knowledge of pulpal space anatomy in three dimensions and ease of identification of rare aberrations. These methods include spiral computed tomography (SCT), microcomputed tomography, and CBCT.[15,24,25] The difference between these methods with respect to the identification of the root canal systems is mainly because of the variations in the slice thickness. Neelakantan et al. in a study investigated the accuracy of CBCT, peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pCT), SCT, plain (plain digi), and contrast medium-enhanced digital radiographs (contrast digi) in analyzing root canal morphology and concluded that CBCT and pCT are as accurate as the gold standard (modified canal staining and clearing technique) in identifying the root canal morphology.[15] CBCT imaging is an excellent method to analyze the variations in external and internal root anatomy. CBCT technology overcomes several drawbacks of conventional radiography as thin, relatively high-resolution, high-contrast slices eliminate the artifacts resulting from superimposition of adjacent anatomical structures.[26] The root canal anatomy of the teeth can also be observed in a 3D view aiding in identification of rare aberrations.[7,12,27] Ozcan et al. (2016) in a recent study have also employed CBCT to evaluate the root canal morphology of human primary molars.[28] Hence, CBCT was used in the present study for visualizing the root and root canal morphology of the maxillary anterior teeth.

In the present study, the most common canal configuration observed in maxillary anterior teeth among the population studied was Type I [Table 1] which is concomitant with the reports of Vertucci, Sert, and Bayirli.[7,8] Maxillary central incisors have been observed to possess only a single canal in 100% of American and Turkish populations.[7,8] An earlier study in Caucasian population revealed the prevalence of Type I configuration in 100% of maxillary central incisors,[8] whereas another study in the Turkish population revealed 98% Type I and 2% Type IV canal pattern in maxillary central incisors.[7] In addition, Weng et al. have reported Type I configuration in 95.8% of the maxillary central incisors.[20] Various other studies also have investigated the root canal anatomy among different teeth and reached the conclusion that the maxillary central incisor is the tooth with the least anatomic variations, showing a single canal (Vertucci's Type I canal pattern) in 100% of the cases.[8,11,18] However, isolated case reports of maxillary central incisors presenting with two, three, and four independent root canals have been reported in the literature.[29,30] Mangani and Ruddle also reported a case of Dens Invaginatus presenting four root canals in a maxillary central incisor.[31] This invagination can occur at the crown of the tooth or sometimes might extend into the root resulting in complex canal systems.[32]

In this study, maxillary lateral incisors revealed 98% Type I and 2% Type II root canal configuration. A study in Turkish population by Caliskan et al. reported that the maxillary lateral incisors exhibited variations with 78.05% Type I, 2.44% Type II, 14.63% Type III, and 4.88% Type V canal configurations.[12] Numerous studies conducted among Asian population revealed the following canal variations in maxillary lateral incisors: 91.4% Type I, 2.9% Type II, and 4.3% Type III pattern in Chinese Guanzhong area; 96.6% Type I, 1.2% Type III, and 1.1% Type V canal pattern in Sri Lanka population; 94% Type I and 4.5% Type V canal pattern in Japanese population.[20,33] Furthermore, isolated clinical reports of maxillary lateral incisors presenting with aberrant conditions such as Dens invaginatus, palatogingival groove, and peg laterals have been reported in literature.[34,35,36] However, none of the maxillary lateral incisors examined in the present study reported these variations in the population studied.

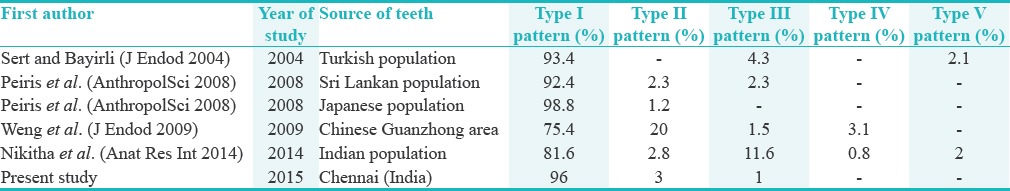

In the present study, maxillary canines in Indian population revealed 96% Type I, 3% Type II, and 1% Type III root canal configuration. A study by Caliskan et al. reported that 93.4% of maxillary canines had Type 1 canal configuration in a Turkish population.[12] Sert and Bayirli reported that the root canal configurations for maxillary canines were 91% Type 1, 3% Type 2, 4% Type 3, and 2% Type 4 in males and the root canal configurations for female patients were 96% Type 1 and 4% Type 4.[7] Weng et al. in a study in Chinese population reported the canal variations of maxillary canines with 75.4% Type I, 20% Type II, 1.5% Type III, and 3.1% Type IV configurations.[20] Peiris reported the following canal variations in maxillary canines: 92.4% Type I, 2.3% Type II, 2.3% Type III in Sri Lanka population, and 98.8% Type I, 1.2% Type II in Japanese population.[33] Somalinga Amardeep et al. in a study in Indian population reported that maxillary canines exhibited 81.6% Type I, 2.8% Type II, 11.6% Type III, 0.8% Type IV, and 2% Type V canal patterns.[17] On the contrary, Type IV and Type V canal patterns were not reported in maxillary canines among this institutional-based population study. Variations in the root canal morphology of maxillary canines among different populations are presented in Table 2.[7,17,20,33]

Table 2.

Root canal morphology of maxillary canines in various studies among different populations

It has been shown that these conflicting reports of various anatomical studies might be attributed to differences in the observation methods, classification systems, sample sizes, and ethnic backgrounds of tooth specimens.[37] Study design differences and the various origins of the investigated teeth could also account for the highly variable results.

Awareness of the probable variations in root and root canal anatomy reduces the possibility of unobserved canals during root canal treatment. With globalization and the world coming closer, people from various countries and different races are found settled worldwide. Hence, a thorough knowledge of the root canal anatomy of different ethnic populations can facilitate a more predictable outcome of endodontic treatment.[15,20] As stated by Ghasemi et al. in a recent article, the complexity of the root canal system is influenced by genetics, and this factor should also be always considered before interpreting and comparing the results of various other morphological studies, in addition to factors such as age and gender.[38] However, a careful interpretation of multiple-angled preoperative intraoral radiographs and use of 3D imaging (CBCT/pCT) along with the aid of a dental operating microscope might be useful in effective identification of such root canal variations and their successful endodontic management.

However, this current study is not without its limitations. This institutional-based research attempted in Chennai urban city was a preliminary study to assess the root canal morphology of permanent maxillary anterior teeth in the Indian population. Although patients across various places in Tamil Nadu and various countries across India report to our institution, this study does not represent either total Chennai or Indian population. Hence, further studies pertaining to the root canal anatomy of maxillary anterior teeth collected from various representative zones in urban cities like Chennai across the entire state and various such representations from all the states across India should be undertaken to reflect a true picture of canal variations among Indian population.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this institutional-based CBCT study in Chennai population, it could be concluded that:

Type I was the most common canal pattern observed in maxillary anterior dentition.

All maxillary central incisors (100%) revealed a Type I canal configuration.

Most of the maxillary lateral incisors (98%) revealed Type I canal configuration whereas 2% of maxillary lateral incisors displayed Type II pattern.

In addition to Type I (96%) configuration, maxillary canines revealed Type II (3%) and Type III (1%) canal patterns.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: Part 1: Periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44:583–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen S, Hargreaves KM. Pathways of the Pulp. 9th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Elsevier; 2006. pp. 216–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vertucci FJ. Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endod Top. 2005;10:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess W, Zurcher E. The Anatomy of Root Canals of Teeth of Permanent and Deciduous Dentitions. New York: William Wood and Co; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naseri M, Safi Y, Akbarzadeh Baghban A, Khayat A, Eftekhar L. Survey of anatomy and root canal morphology of maxillary first molars regarding age and gender in an Iranian population using cone-beam computed tomography. Iran Endod J. 2016;11:298–303. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trope M, Elfenbein L, Tronstad L. Mandibular premolars with more than one root canal in different race groups. J Endod. 1986;12:343–5. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(86)80035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sert S, Bayirli GS. Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. J Endod. 2004;30:391–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200406000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:589–99. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rwenyonyi CM, Kutesa AM, Muwazi LM, Buwembo W. Root and canal morphology of maxillary first and second permanent molar teeth in a Ugandan population. Int Endod J. 2007;40:679–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sert S, Sahinkesen G, Topçu FT, Eroǧlu SE, Oktay EA. Root canal configurations of third molar teeth. A comparison with first and second molars in the Turkish population. Aust Endod J. 2011;37:109–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2010.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattanshetti N, Gaidhane M, Al Kandari AM. Root and canal morphology of the mesiobuccal and distal roots of permanent first molars in a Kuwait population – A clinical study. Int Endod J. 2008;41:755–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calişkan MK, Pehlivan Y, Sepetçioǧlu F, Türkün M, Tuncer SS. Root canal morphology of human permanent teeth in a Turkish population. J Endod. 1995;21:200–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80566-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weine FS, Hayami S, Hata G, Toda T. Canal configuration of the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar of a Japanese sub-population. Int Endod J. 1999;32:79–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasti F, Shearer AC, Wilson NH. Root canal systems of the mandibular and maxillary first permanent molar teeth of South Asian Pakistanis. Int Endod J. 2001;34:263–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neelakantan P, Subbarao C, Subbarao CV. Comparative evaluation of modified canal staining and clearing technique, cone-beam computed tomography, peripheral quantitative computed tomography, spiral computed tomography, and plain and contrast medium-enhanced digital radiography in studying root canal morphology. J Endod. 2010;36:1547–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohammadzadeh Akhlaghi N, Khalilak Z, Vatanpour M, Mohammadi S, Pirmoradi S, Fazlyab M, et al. Root canal anatomy and morphology of mandibular first molars in a selected Iranian population: An In vitro study. Iran Endod J. 2017;12:87–91. doi: 10.22037/iej.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somalinga Amardeep N, Raghu S, Natanasabapathy V. Root canal morphology of permanent maxillary and mandibular canines in Indian population using cone beam computed tomography. Anat Res Int. 2014;6:731859. doi: 10.1155/2014/731859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta S, Sinha DJ, Gowhar O, Tyagi SP, Singh NN, Gupta S, et al. Root and canal morphology of maxillary first premolar teeth in North Indian population using clearing technique: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2015;18:232–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.157260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Pawar M. Root canal morphology of South Asian Indian maxillary molar teeth. Eur J Dent. 2015;9:133–44. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.149662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng XL, Yu SB, Zhao SL, Wang HG, Mu T, Tang RY, et al. Root canal morphology of permanent maxillary teeth in the Han nationality in Chinese Guanzhong area: A new modified root canal staining technique. J Endod. 2009;35:651–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarze T, Baethge C, Stecher T, Geurtsen W. Identification of second canals in the mesiobuccal root of maxillary first and second molars using magnifying loupes or an operating microscope. Aust Endod J. 2002;28:57–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2002.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao T, Neelakantan P. Three-dimensional imaging modalities in endodontics. Imaging Sci Dent. 2014;44:177–83. doi: 10.5624/isd.2014.44.3.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotton TP, Geisler TM, Holden DT, Schwartz SA, Schindler WG. Endodontic applications of cone-beam volumetric tomography. J Endod. 2007;33:1121–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandhya R, Velmurugan N, Kandaswamy D. Assessment of root canal morphology of mandibular first premolars in the Indian population using spiral computed tomography: An in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:169–73. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.66626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan B, Yang J, Gutmann JL, Fan M. Root canal systems in mandibular first premolars with C-shaped root configurations. Part I: Microcomputed tomography mapping of the radicular groove and associated root canal cross-sections. J Endod. 2008;34:1337–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassan BA, Payam J, Juyanda B, Van der Stelt P, Wesselink PR. Influence of scan setting selections on root canal visibility with cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:645–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/27670911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aminsobhani M, Sadegh M, Meraji N, Razmi H, Kharazifard MJ. Evaluation of the root and canal morphology of mandibular permanent anterior teeth in an Iranian population by cone-beam computed tomography. J Dent (Tehran) 2013;10:358–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozcan G, Sekerci AE, Cantekin K, Aydinbelge M, Dogan S. Evaluation of root canal morphology of human primary molars by using CBCT and comprehensive review of the literature. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74:250–8. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2015.1104721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gondim E, Jr, Setzer F, Zingg P, Karabucak B. A maxillary central incisor with three root canals: A case report. J Endod. 2009;35:1445–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cimilli H, Kartal N. Endodontic treatment of unusual central incisors. J Endod. 2002;28:480–1. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200206000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mangani F, Ruddle CJ. Endodontic treatment of a “very particular” maxillary central incisor. J Endod. 1994;20:560–1. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hülsmann M. Dens invaginatus: Aetiology, classification, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment considerations. Int Endod J. 1997;30:79–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1997.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peiris R. Root and canal morphology of human permanent teeth in a Sri Lankan and Japanese population. Anthropol Sci. 2008;116:123–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh SC, Lin YT, Lu SY. Dens invaginatus in the maxillary lateral incisor: Treatment of 3 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:628–31. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasanth K, Kottoor J, Nandini S, Velmurugan N, Abarajithan M. Palatogingival groove mimicking as a mutilated root fracture in a maxillary lateral incisor: A case report. Gen Dent. 2014;62:e20–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kook YA, Park S, Sameshima GT. Peg-shaped and small lateral incisors not at higher risk for root resorption. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:253–8. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sert S, Aslanalp V, Tanalp J. Investigation of the root canal configurations of mandibular permanent teeth in the Turkish population. Int Endod J. 2004;37:494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghasemi N, Rahimi S, Shahi S, Samiei M, Frough Reyhani M, Ranjkesh B, et al. Areview on root anatomy and canal configuration of the maxillary second molars. Iran Endod J. 2017;12:1–9. doi: 10.22037/iej.2017.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]