Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of depression among elderly people varies across different setups such as old age homes (OAHs), community, and medical clinics.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to compare the epidemiological factors pertaining to depression among elderly residents of OAHs and community, using a new Gujarati version of the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form (GDS-G).

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional, epidemiological study conducted in an urban setup of Western India.

Materials and Methods:

All the eligible 88 elderly residents of all the six OAHs and 180 elderly residents from the same city were administered a pretested semistructured questionnaire having the GDS-G form.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics, odds ratio, Spearman's rank correlation test.

Results:

The elderly of OAHs were more depressed compared to those of community (odds ratio = 1.84; 95% confidence interval = 1.09–3.06). Older age, females, weaker family ties, economic maladies, poorer self-perception of health status, presence of chronic ailments, absence of recreational activity, lack of prayers, impaired sleep, history of addiction emerged as the predictors of depression in both the setups. More health complaints and a later self-perception of visit to a doctor were found among the depressed than the nondepressed in both the setups.

Conclusions:

Depressive symptoms were quite high among the elderly in both the setups. Special attention should be given toward health checkups of depressed persons in the OAH and improvement of family ties among depressed persons of the community.

Keywords: Community, depression, elderly, geriatric depression scale, old age homes, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The global share of people aged ≥60 years has increased from 9.2% (1990) to 11.7% (2013) and is projected to reach 21.1% of the world's population by 2050. Globally, the number of people ≥60 years is expected to more than double, from 841 million people in 2013 to more than 2 billion in 2050.[1] Although India was ranked 105th in the global country-wise ranking of percentage of population aged ≥60 years (8.2%),[1] the sheer large numbers of elderly population in India (96 million) coupled with the ever increasing life expectancy make it the second largest country of the elderly in the world.

Depression is among the most common psychiatric disorders among the elderly.[2] The ever-increasing proportion of elderly population of India makes the burden of depression increase over time. Studies using different screening criterion have been conducted at various setups such as community, psychiatric clinics, outpatient departments, and old age homes (OAHs) to gauge the prevalence of depression among the elderly. However, they have revealed a varying range of prevalence of depression throughout the country.[3] Studies in similar geographical locations using the same set of tools to evaluate depression across multiple setups can provide comparative insights into the scenario of depression.

Hence, this study was planned out to provide a comparative scenario of depression and its associates among elderly residents of OAHs and the community in the same geographical location.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling technique

All the elderly residents (≥60 years of age)[4] of all the six OAHs of Rajkot city were studied. Elderly who had any demonstrative hearing, understanding, speech impairment, or refusing to be part of the study were excluded. A total of 88 elderly residents were thus obtained from the OAHs. To get details of the elderly of the community, it was decided to have twice the number of elderly from the community as that obtained from the OAHs. Hence, a total of 176 elderly residents were to be studied. It was decided to have an equal representation of the elderly residing in the ‘slum/semi-slum’ and ‘non-slum’ areas of the entire city. Multistage sampling method was used to select the households. Stage 1: all the three ‘zones’ (East, West, and Central) as demarcated by the Rajkot Municipal Corporation were included in the study. Stage 2: from each ‘zone,’ two ‘slum/semi-slum’ and two ‘non-slum’ areas were selected by simple random sampling. Hence, from each ‘zone,’ four areas were selected. Stage 3: from each area, 15 elderly persons were selected; totaling up to 180 elderly persons across the 12 areas of the city. Stage 4: after reaching the center point of the area, the first nearest household on the East (purposively) was selected as the starting point. All the elderly persons within one household were covered and then adjacent households were visited till 15 elderly persons from one area were obtained. Standard ethical protocol was adhered to at all stages of the study.

Study instruments

A pretested, semistructured interview schedule was used. Sleep duration <7 hours within a period of 24 hours was considered as ‘impaired sleep.’[5] Enquiries into common preexisting chronic health ailments were made. A 7-point Likert scale was used to enquire as to which stage of illness the elderly would be most likely to visit a doctor. Guidelines of the VIIth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-VII) were used for classifying blood pressure.[6]

The study used the 15-item Geriatric Depression rating Scale Short Form (GDS-15/GDS-SF) for screening for depression in the elderly population.[7] GDS-SF has shown good sensitivity and specificity for predicting depressive disorders in different settings.[8,9,10] Keeping the local language proficiency, it was decided to use Gujarati version of the questions for assessing depression and emotional well-being. The Gujarati version (GDS-G) had been extensively reviewed and reframed before the actual start of this study.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered and analyzed using Epi Info software version 3.5.1[11] and MS Office Excel 2007. For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Profile of depression

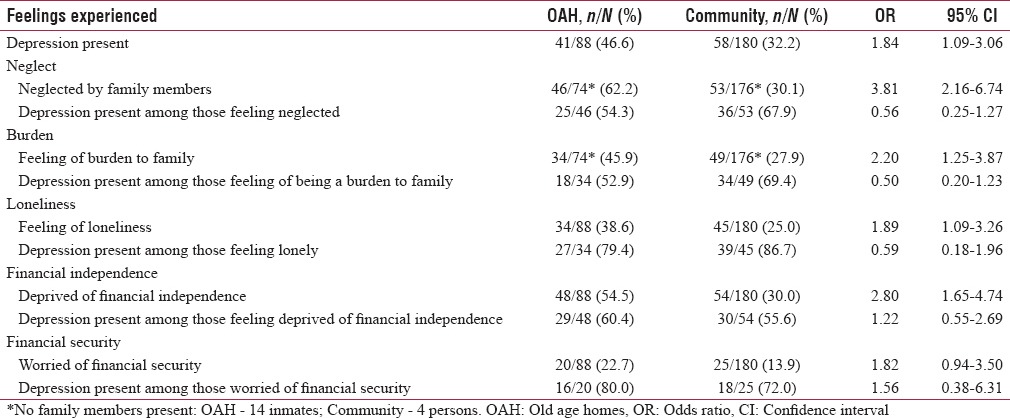

Table 1 shows that the association of depression was significantly more (odds ratio [OR] = 1.84; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.09–3.06) among the elderly of OAHs (46.6%) as compared to community (32.2%). The proportion of males and females being depressed was more in OAHs (46.7% males and 46.6% females), than in community (24.7% males and 37.9% females). A positive correlation was found with rising age and levels of depression in both settings (OAH: Spearman's rho = 0.38, P = 0.00; Community: Spearman's rho = 0.32, P = 0.00).

Table 1.

Profile of depression among elderly inmates of old age homes and community

It is pertinent to note that though feeling of ‘being neglected by their family members’ was significantly more among the elderly of OAHs than community (OR = 3.81; 95% CI = 2.16–6.74), the prevalence of depression was more among those grousing such a feeling of neglect by family members and yet staying in community (67.9%), rather than in OAHs (54.3%).

Although the feeling of ‘being a burden to the family’ was significantly higher (OR = 2.20; 95% CI = 1.25–3.87) among inmates of OAH, the prevalence of depression was higher among those harboring such a feeling in community (69.4%) than in OAHs (52.9%).

The ‘feeling of loneliness’ was significantly higher (OR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.09–3.26) among residents of OAHs. However, the prevalence of depression was higher among those elderly persons who inspite of staying in community (86.7%) had a ‘feeling of loneliness’ as compared to those having such a feeling but staying in OAHs (79.4%).

There was a negative correlation between “monthly income received now” and the levels of depression in both setups (OAH: Spearman's rho = −0.223, P = 0.037; Community: Spearman's rho= −0.346, P = 0.000).

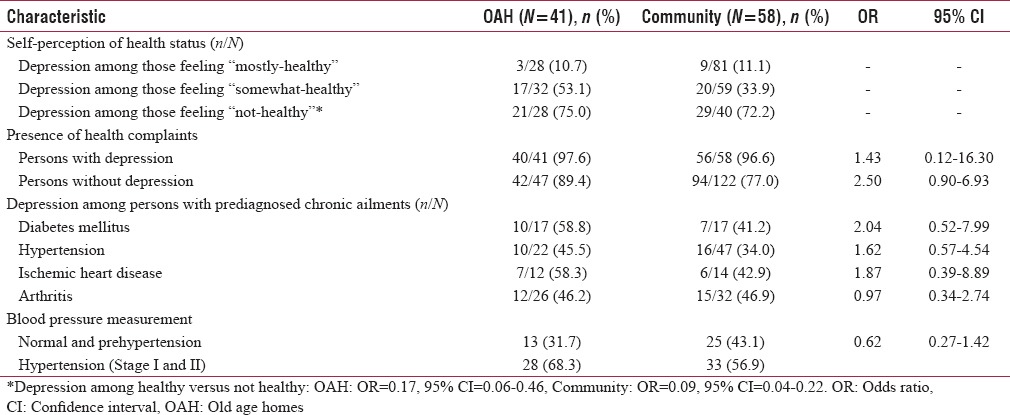

Health status

The prevalence of depression in both OAH and community decreased as one proceeded from the bottom level (not-healthy) to the top tier (mostly-healthy) of the pyramid of ‘self-perception of health-status’ [Table 2]. The presence of health complaints was more among depressed in both setups. A larger proportion of elderly persons who were suffering from diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease were found depressed in OAHs than in community. The prevalence of depression among those who had ‘normal and pre-hypertension’ was (13/36) 36.1% for inmates of OAHs as compared to (25/97) 25.8% for the elderly of community. The presence of depression among those who had ‘stage I and stage II hypertension’ was higher in the residents of OAHs (28/52: 53.8%) as compared to community (33/83: 39.8%).

Table 2.

Health status of the depressed elderly inmates of old age homes and community

The median level of ‘self-perception of illness, prompting an elderly to visit a doctor’ was for a later stage of illness, among depressed (OAH - five; community - four) as compared to not-depressed (OAH - two; community - two).

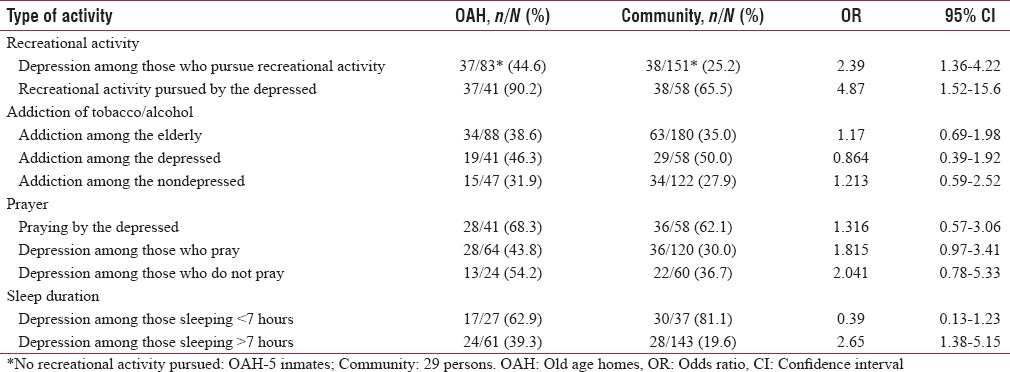

Other activities

A significant association (OR = 2.39, 95% CI = 1.36-4.22) was found in the pursuit of recreational activity and the absence of depression in both setups [Table 3]. A larger proportion of depressed persons of OAH pursued some recreational activity as compared to those of community (OR = 4.87, 95% CI = 1.52–15.6). The prevalence of addiction was comparatively more among depressed (vs. nondepressed) in OAH (46.3% vs. 31.9%: OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 0.77–4.38) and community (50.0% vs. 27.9%: OR = 2.58, 95% CI = 1.35–4.95). A greater proportion of those who having impaired sleep were found to be depressed, both in OAHs (62.9%) and community (81.1%). A significant association was found between the presence of impaired sleep and depression among the elderly of OAH (62.9% vs. 39.3%: OR = 2.62, 95% CI = 1.03–6.68) and community (81.1% vs. 19.6%: OR = 17.60, 95% CI = 7.01–44.19).

Table 3.

Activities pursued by depressed elderly inmates of old age homes and community

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of depression was found to be high in both setups. The levels of depression increased with age in both settings. Rising age has been found as a significant predictor of depression in several studies.[12,13,14,15,16,17]

The prevalence of depression was more among the elderly who had a feeling of ‘being neglected by their family members,’ ‘being a burden to the family members,’ and yet having to stay in the community. Studies have ascribed this depression to the loss of earning status, hence becoming a passive decision-maker, who often gets ignored in family decision-making process, which aggravates their loss of dignity compounded by breakdown of family ties, lowering self-esteem and heightening feeling of neglect.[18,19]

The prevalence of depression was higher among those elderly persons who inspite of staying in the community harbored a ‘feeling of loneliness’ as compared to those having such a feeling and staying in OAHs. These findings accurately reciprocate the feelings of the inmates of OAHs, who have confessed that their loneliness had forced them to shift to an OAH from community.[14,15,20,21]

Levels of depression increased as monthly income received by the elderly decreased. The WHO lists nine subcomponents pertaining toward detection of “financial abuse” among elderly person.[22] A study by Chou et al. revealed that elderly people living alone had higher levels of financial strain and more depressive symptoms.[23]

The prevalence of depression in both settings decreased as one's self perception of health status improved. A meta-analysis found that elderly people with poor self-rated health had higher risk of depression than those with good self-rated health (RR = 2.40; 95% CI = 1.94–2.97).[24] Bodhare et al. found a significant association (P = 0.01) between perceived poor health status and depression.[25] In a study among the elderly of South Korea, Woo et al. found that self-assessed health status was a good predictor of mortality and functional ability.[26]

Health complaints were more among depressed than nondepressed in both settings. A quantitative meta-analysis showed that compared with those elderly persons without chronic diseases, those with chronic diseases had a higher risk for depression (RR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.20–1.97).[24] A study by Akhtar et al. study showed that the presence of any chronic health problem increased risk of depression (OR = 1.43; 95% CI = 1.01–2.02).[16] Joshi et al. found an inverse relationship between number of physical morbidities and psychological well-being.[27]

The prevalence of depression was higher in those who ‘did not pray’ as compared to those who ‘prayed’ in both locales. Patel et al. highlighted the importance of prayer as a potentially effective intervention in dealing with depression among the elderly.[19]

A greater proportion of those elderly persons having ‘impaired sleep’ was found depressed in both settings. Sleep problem has been recommended as one of the indicators of ‘behavioral and emotional abuse’ among the elderly by the WHO.[22]

Limitations

GDS-15 is a well-recognized tool to detect depression in various settings:[8,9,10] however, no Gujarati version of it was available at the time of conducting the study. Hence, this study developed a Gujarati version of the GDS-15 scale using forward translation, back translation, pretesting, and cognitive interviewing techniques.[28] However, this process had not been validated.

CONCLUSIONS

Older age, females, weaker family ties, economic maladies, poorer self-perception of health status, chronic ailments, absence of recreational activity, lack of prayers, impaired sleep, history of addiction emerged as predictors of depression in both setups. Special attention should be given toward health checkups of depressed persons in OAHs and improvement of family ties among depressed persons residing in community.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Economic and Social Affairs World Population Ageing 2013. New York: United Nations; 2013. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 04]. United Nations. Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satcher D. Mental health: A report of the surgeon general-executive summary. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2000;31:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grover S, Malhotra N. Depression in elderly: A review of Indian research. J Geriatr Ment Health. 2015;2:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proceeding of NIPHC/HCPT Seminar on Services for the Aged-A National Commitment. New Delhi: 1996. Northern Illinios Public Health Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- 5.How Much Sleep Do We Really Need? Arlington, VA: National Sleep Foundation; 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 05]. National Sleep Foundation. Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/how-sleep-works/how-much-sleep-do-we-really-need . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Joseph L. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, US: Department of Health and Human Services US; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (short version) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;24:709–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wancata J, Alexandrowicz R, Marquart B, Weiss M, Friedrich F. The criterion validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:398–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kieffer KM, Reese RJ. A reliability generalization study of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 2002;62:969–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marc LG, Raue PJ, Bruce ML. Screening performance of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in a diverse elderly home care population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:914–21. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318186bd67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epi Info Ver. 3.5.1; 2008. Atlanta, US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Last accessed on 2012 Jun 11]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao KX, Huang CQ, Xiao Q, Gao Y, Liu QX, Wang ZR, et al. Age and risk for depression among the elderly: A meta-analysis of the published literature. CNS Spectr. 2012;17:142–54. doi: 10.1017/S1092852912000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sengupta P, Benjamin AI. Prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among the elderly in urban and rural field practice areas of a tertiary care institution in Ludhiana. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:3–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.152845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swarnalatha S. The prevalence of Depression among the rural elderly in Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1356–60. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5956.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy NB, Pallavi M, Reddy NN, Reddy CS, Singh RK, Pirabu RA. Psychological morbidity status among the rural geriatric population of Tamil Nadu, India: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:227–31. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akhtar H, Khan AM, Vaidhyanathan KV, Chhabra P, Kannan AT. Socio-demographic predictors of depression among the elderly patients attending out patient departments of a tertiary hospital in North India. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:971–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakulan A, Sumesh TP, Kumar S, Rejani PP, Shaji KS. Prevalence and risk factors for depression among community resident older people in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:262–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox D, Jimenez E. Achieving social objectives through private transfer. Oxford J Econ Soc Sci. 1990;5:205–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel V, Prince M. Ageing and mental health in a developing country: Who cares? Qualitative studies from Goa, India. Psychol Med. 2001;31:29–38. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799003098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, Mohan U, Tiwari SC, Singh SK, Singh VK. Quality of life of elderly people and assessment of facilities available in old age homes of Lucknow, India. Natl J Community Med. 2014;5:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawale AK, Mudey A, Lanjewar A, Wagh VV. Study of morbidity pattern in inmates of old age homes in urban area of central India. J Indian Acad Geriatr. 2010;6:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Abuse of the Elderly. Ch. 5. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Last accessed on 2016 May 25]. Violence injury prevention; p. 139. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap5.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou K, Chi L. Comparison between elderly persons living alone and those living with other. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2000;33:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L. Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: A meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2010;39:23–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodhare TN, Kaushal V, Venkatesh K, Anil Kumar M. Prevalence and risk factors of depression among elderly population in a rural area. Perspect Med Res. 2013;1:11–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woo EK, Han C, Jo SA, Park MK, Kim S, Kim E, et al. Morbidity and related factors among elderly people in South Korea: Results from the Ansan Geriatric (AGE) cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi K, Kumar R, Avasthi A. Morbidity profile and its relationship with disability and psychological distress among elderly people in Northern India. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:978–87. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 May 17]. Available from: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/# . [Google Scholar]