Abstract

The transcription factors Msn2 and Msn4 (multicopy suppressor of SNF1 mutation proteins 2 and 4) bind the stress-response element in gene promoters in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, the roles of Msn2/4 in primary metabolic pathways such as fatty acid β-oxidation are unclear. Here, in silico analysis revealed that the promoters of most genes involved in the biogenesis, function, and regulation of the peroxisome contain Msn2/4-binding sites. We also found that transcript levels of MSN2/MSN4 are increased in glucose-depletion conditions and that during growth in nonpreferred carbon sources, Msn2 is constantly localized to the nucleus in wild-type cells. Of note, the double mutant msn2Δmsn4Δ exhibited a severe growth defect when grown with oleic acid as the sole carbon source and had reduced transcript levels of major β-oxidation genes. ChIP indicated that Msn2 has increased occupancy on the promoters of β-oxidation genes in glucose-depleted conditions, and in vivo reporter gene analysis indicated reduced expression of these genes in msn2Δmsn4Δ cells. Moreover, mobility shift assays revealed that Msn4 binds β-oxidation gene promoters. Immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-peroxisome membrane protein antibodies disclosed that the msn2Δmsn4Δ strain had fewer peroxisomes than the wild type, and lipid analysis indicated that the msn2Δmsn4Δ strain had increased triacylglycerol and steryl ester levels. Collectively, our data suggest that Msn2/Msn4 transcription factors activate expression of the genes involved in fatty acid oxidation. Because glucose sensing, signaling, and fatty acid β-oxidation pathways are evolutionarily conserved throughout eukaryotes, the msn2Δmsn4Δ strain could therefore be a good model system for further study of these critical processes.

Keywords: fatty acid metabolism, lipotoxicity, peroxisome, stress response, transcription regulation, triacylglycerol, β-oxidation, Msn2 and Msn4

Introduction

The maintenance of cellular integrity is one of the most crucial factors in cell survival. All cell types, from unicellular to those in multicellular organisms, possess a robust and well-evolved mechanism to address environmental stress. Response to such stress requires a complex network of sensing and signal transduction mechanisms that include transcriptional regulation of genes. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two closely related transcription factors named Msn2 and Msn4 (multicopy suppressor of SNF1 mutation proteins 2 and 4) are master regulators of stress-responsive gene expression (1). Msn2 and Msn4 are zinc finger proteins that share 66% sequence homology. Both proteins bind specifically to the stress response element (STRE)3 5′-AGGGG or 5′-GGGGA during stress (2). Msn2/Msn4 influence the expression of more than 90% of the genes that are up-regulated during heat stress, osmotic stress, and carbon starvation stress (3). However, these transcription factors have not yet been implicated in fatty acid metabolism.

Regulation of stress-responsive genes is critically dependent on the translocation of Msn2/Msn4 from the cytosol to the nucleus. Msn2 is distributed in the cytosol under glucose-rich conditions or in cells in log phase, whereas a sudden depletion in glucose or stress results in predominant nuclear localization (4). S. cerevisiae invokes evolutionarily conserved glucose sensing and signaling pathways to adopt such changes within the nutritional environment (5), with two major pathways that mediate glucose signaling. Snf1, a serine/threonine protein kinase-dependent pathway that is activated under glucose-limited conditions, promotes induction of glucose-repressed genes (6). The other pathway, the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway, is activated by cAMP in response to elevated glucose levels.

In addition to playing crucial roles in cell cycle progression and energy metabolism, the PKA pathway has been established as the major regulator of metabolic reprogramming in regulation of environmental stress responses (7). The Msn2/Msn4-mediated stress response is negatively regulated by cAMP-dependent PKA (7, 8), and PKA-mediated stress resistance is due to localization of Msn2 in the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of stress-inducible genes (4). However, activated PKA prevents nuclear localization of Msn2 via phosphorylation, which ultimately leads to inhibition of the general stress response (9).

The regulatory role of Msn2/Msn4 has also been implicated in the conserved target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway, which regulates multiple cellular processes in response to nutrient stress, such as from nitrogen, carbon, and amino acids (10). Inhibition of TOR signaling in yeast and many other organisms leads to increased longevity and enhanced stress responses caused by nuclear accumulation of Msn2/Msn4 (11).

Cells increase peroxisome biogenesis and proliferation under low-glucose or stationary-phase conditions (12, 13). Based on the available data, it is clear that Msn2/Msn4 localizes predominantly to the nucleus under low-glucose or stress (oxidative, heat, and osmotic) conditions (4, 14, 15). However, Msn2/Msn4 localization during growth on non-favorable carbon sources, such as oleate, galactose, and glycerol, has not been studied to date.

Maintenance of cells under low-glucose or stress conditions requires energy. Based on the findings cited above, it is clear that Msn2/Msn4 may have crucial roles in maintaining cellular energy homeostasis and in cell survival during conditions of low glucose or stress, in addition to their functions in regulating the TOR and PKA pathways. However, the exact regulatory mechanism is not known. Because fatty acid catabolism through β-oxidation provides an alternative source of ATP production in response to low-glucose or stationary-phase conditions, it can be hypothesized that Msn2/Msn4 may play a role in fatty acid metabolism under glucose-limiting or stationary-phase conditions.

In the present study, we report that the stress response transcription factors Msn2/Msn4 positively regulate β-oxidation genes under stationary-phase conditions in S. cerevisiae. Msn2/Msn4 play a vital role in management of fatty acid toxicity and in peroxisome development. Furthermore, by utilizing the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant and single-deletion strains of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis and function, we show that triacylglycerol (TAG) and steryl ester (SE) accumulate to avoid fatty acid toxicity.

Results

The Msn2/Msn4 consensus binding site is present in the upstream region of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism

In silico analysis of the promoter sequences of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis and function was performed using the pattern match tool from the Saccharomyces Genome Database. Our analysis revealed the presence of the Msn2/Msn4/STRE, a 5′-AGGGG/GGGGA (2) binding site, in the upstream sequence of more than 66% of the genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis, function, and regulation (Table 1). These analyses revealed that Msn2 and Msn4 may regulate these genes under glucose-limiting conditions.

Table 1.

Peroxisome genes have Msn2/Msn4-binding site at promoter region

| S no. | Systematic name | Gene name | STRE element (at −10−3 to −1 bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YDR216W | ADR1 | −190 |

| 2 | YAL051W | OAF1 | −606 |

| 3 | YIL160C | POT1 | −182 |

| 4 | YGL205W | POX1 | −285 |

| 5 | YKR009C | FOX2 | −120 |

| 6 | YLR284C | ECI1 | −433 |

| 7 | YNL202W | SPS19 | −193 |

| 8 | YOR180C | DCI1 | −381 |

| 9 | YKL197C | PEX1 | −396 |

| 10 | YJL210W | PEX2 | −759 |

| 11 | YDR244W | PEX5 | −317 |

| 12 | YNL329C | PEX6 | −454 |

| 13 | YDR142C | PEX7 | −134 |

| 14 | YLR191W | PEX13 | −971 |

| 15 | YNL214W | PEX17 | −324 |

| 16 | YHR160C | PEX18 | −378 |

| 17 | YDL065C | PEX19 | −298 |

| 18 | YAL055W | PEX22 | −891 |

| 19 | YPL112C | PEX25 | −633 |

| 20 | YHR150W | PEX28 | −535 |

| 21 | YDR479C | PEX29 | −859 |

| 22 | YGR004W | PEX31 | −402 |

| 23 | YBR168W | PEX32 | −804 |

| 24 | YCL056C | PEX34 | −858 |

| 25 | YPL147W | PXA1 | −461 |

| 26 | YKL188C | PXA2 | −264 |

| 27 | YJR104C | SOD1 | −218 |

| 28 | YHR008C | SOD2 | −76 |

| 29 | YER015W | FAA2 | −597 |

| 30 | YMR246W | FAA4 | −890 |

| 31 | YML042W | CAT2 | −746 |

| 32 | YDR256C | CTA1 | −820 |

| 33 | YCR005C | CIT2 | −473 |

| 34 | YNL009W | IDP3 | −812 |

| 35 | YLR151C | PCD1 | −166 |

| 36 | YFL030W | AGX1 | −796 |

| 37 | YNL242W | ATG2 | −743 |

| 38 | YIL146C | ATG32 | −177 |

| 39 | YML054C | CYB2 | −397 |

| 40 | YIR004W | DJP1 | −981 |

| 41 | YIL065C | FIS1 | −888 |

| 42 | YDL022W | GPD1 | −210 |

| 43 | YGR154C | GTO1 | −760 |

| 44 | YIR034C | LYS1 | −845 |

| 45 | YDR234W | LYS4 | −398 |

| 46 | YDL078C | MDH3 | −814 |

| 47 | YNL117W | MLS1 | −543 |

| 48 | YBR222C | PCS60 | −70 |

| 49 | YGL037C | PNC1 | −100 |

| 50 | YPR165W | RHO1 | −638 |

| 51 | YLR389C | STE23 | −611 |

| 52 | YGL184C | STR3 | −756 |

| 53 | YJR019C | TES1 | −593 |

| 54 | YKR001C | VPS1 | −797 |

Glucose depletion or the presence of a non-favorable carbon source leads to nuclear localization of Msn2

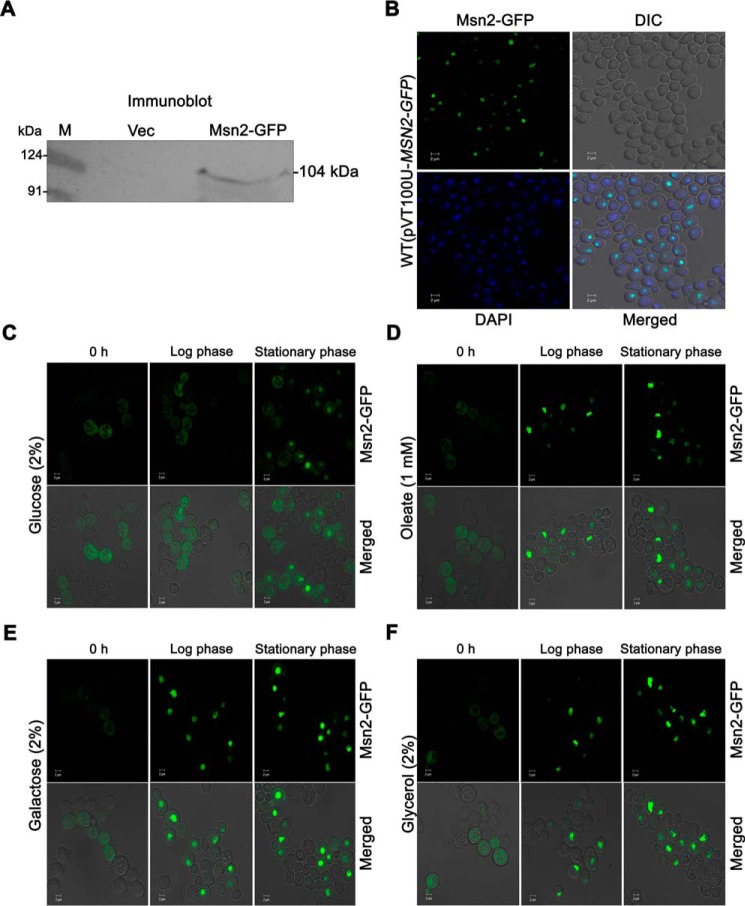

To examine the carbon source-dependent localization of Msn2, an Msn2-GFP fusion construct was generated, and expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A). Nuclear localization of Msn2-GFP was confirmed by staining the cells with DAPI (Fig. 1B). Msn2 localization was also monitored on different sole carbon sources, such as glucose, oleate, galactose, and glycerol, whereby cells grown to different time points were subjected to confocal microscopy. We observed that Msn2-GFP was uniformly distributed in the cytosol at 0 h and in early log-phase conditions in cells grown with glucose, whereas in the stationary phase, it was concentrated in the nucleus (Fig. 1C). In cells grown with oleate, galactose, and glycerol, Msn2-GFP was localized only in the nucleus, irrespective of time point (Fig. 1, D–F). These experiments reveal that glucose limitation (stationary phase) or the presence of a non-favorable carbon source leads to translocation of Msn2 from the cytosol to the nucleus.

Figure 1.

Translocation of Msn2 under various carbon sources. WT cells harboring pVT100U and pVT100U-MSN2-GFP were grown SM−URA medium containing 2% glucose up to stationary phase. A, the expression of Msn2-GFP was confirmed by immunoblotting by anti-GFP antibodies. B, the same cells were used to study the nuclear localization of Msn2-GFP by confocal microscopy. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. C–F, equal numbers of 2% glucose grown log phase cells were transferred to medium containing glucose, oleate, galactose, and glycerol as a sole carbon source, and samples were collected at different time intervals and viewed under a confocal microscope for Msn2-GFP localization study in different carbon source. Bar, 2 μm. Vec, vector; DIC, differential interference contrast.

The msn2Δmsn4Δ double mutant is sensitive to fatty acid toxicity

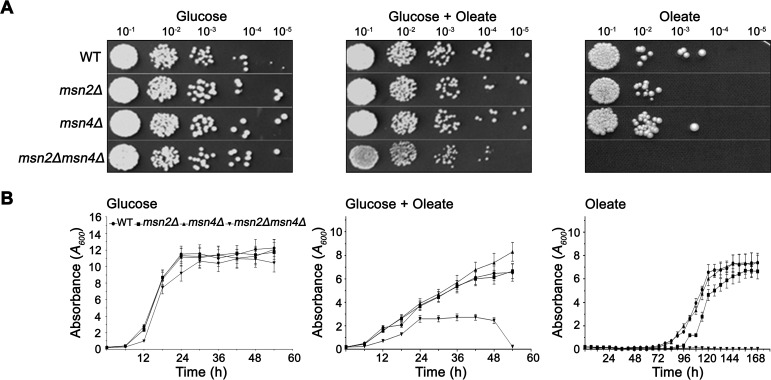

Wild-type, msn2Δ, msn4Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were grown on a medium containing 1 mm oleate and 0.5% glucose or a medium containing only 1 mm oleate as the sole carbon source. The msn2Δmsn4Δ cells showed a severe growth defect on solid agar medium containing 1 mm oleate and 0.5% glucose compared with that containing 2% glucose as the sole carbon source. In contrast, no growth was observed on the medium containing oleate as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2A). However, compared with wild-type cells, msn2Δ and msn4Δ strains did not show any significant growth defects under the same conditions. Similar results were obtained when the growth experiment was performed using a liquid medium (Fig. 2B). These experiments suggest a possible role for Msn2/Msn4 in fatty acid metabolism.

Figure 2.

Effect of lipotoxicity on the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant. WT, msn2Δ, msn4Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were subcultured in synthetic media containing glucose, glucose + oleate, and oleate. The images were obtained on day 3 for glucose-grown cells and day 8 for oleate-grown cells. A, for the spotting experiment, log-phase cells were serially diluted and spotted onto solid agar. B, growth curve analyses of WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ grown with various carbon sources are shown.

Glucose depletion leads to increased mRNA expression of MSN2/MSN4

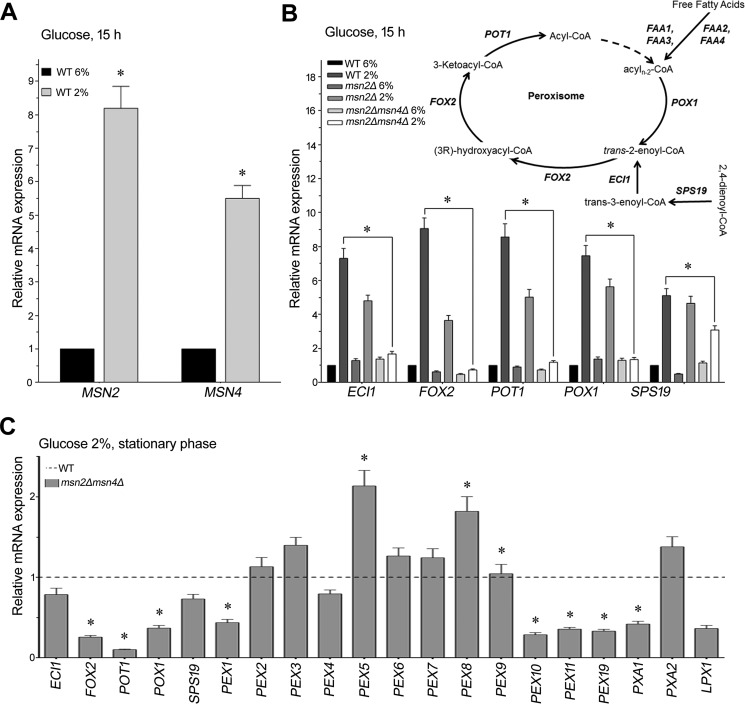

Translocation of Msn2/Msn4 from the cytosol to the nucleus is a stress response mechanism (7). We performed real-time PCR analysis to evaluate the transcript levels of MSN2 and MSN4 under glucose limitation, which was carried out in WT cells grown for 15 h on 2% (normal) and 6% glucose (high glucose). Our results showed that the expression levels of MSN2 and MSN4 increased up to 8.8- and 5.5-fold, respectively, in cells grown on 2% glucose compared with those grown on 6% glucose (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that the stress regulatory mechanism of Msn2/Msn4 occurs via both their translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus and an increase in their transcript levels.

Figure 3.

Expression profiles of MSN2, MSN4, and peroxisomal genes in the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant. WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were grown in 2% or 6% glucose for 15 h. Total RNA was isolated and converted into cDNA for gene expression analysis. ACT1I (actin) was used as an endogenous control. A, relative mRNA levels of MSN2 and MSN4 genes were analyzed only in T cells. B, expression analysis of β-oxidation genes in WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells. C, expression analysis of β-oxidation and peroxisome genes in WT cells grown in 2% glucose up to stationary phase. The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*).

MSN2 and MSN4 double deletion causes reduced expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism under glucose depletion conditions

Fatty acid β-oxidation is an evolutionarily conserved process that is reported to occur in the stationary phase of yeast cells when glucose is exhausted from the medium (13). Therefore, the increased transcript levels of MSN2 and MSN4, nuclear localization of Msn2 in different carbon sources, and the inability of msn2Δmsn4Δ strain to grow on medium containing oleate as the sole carbon source led us to predict a role for these factors in the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism. Accordingly, we performed real-time PCR analysis to assess the expression levels of major genes involved in β-oxidation pathways (Fig. 3B) (16, 17) in WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells grown under normal- and high-glucose conditions. We observed that glucose limitation resulted in increased expression of ECI1, POT1, FOX2, POX1, and SPS19 in WT cells. Single deletion of MSN2 caused a decrease in the expression level of these genes compared with WT cells. However, the expression levels of these genes in msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were extremely low, with no increase under glucose limitation (Fig. 3B).

Double deletion of MSN2 and MSN4 causes reduced expression of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis and β-oxidation under stationary-phase conditions

Peroxisome proliferation and function are known to occur in the stationary phase (13). Thus, we evaluated the expression levels of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis (PEX1 to PEX11 and PEX 19), fatty acid transporters (PXA1 and PXA2), and peroxisome lipase (LPX1) (18–20) in the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant grown to the stationary phase. Overall, expression of genes related to peroxisome biogenesis (PEX1, PEX4, PEX10, PEX11, and PEX19) decreased in msn2Δmsn4Δ (Fig. 3C). Although the level of PXA1 expression was significantly low, no significant change was observed in the level of PXA2. Expression of the peroxisome lipase gene LPX1 was also low in the double mutant. Such decreased expression levels of genes involved in the β-oxidation pathway and peroxisome biogenesis and fatty acid transporters further strengthen the evidence that Msn2/Msn4 transcription factors play an important role under glucose-limitation conditions.

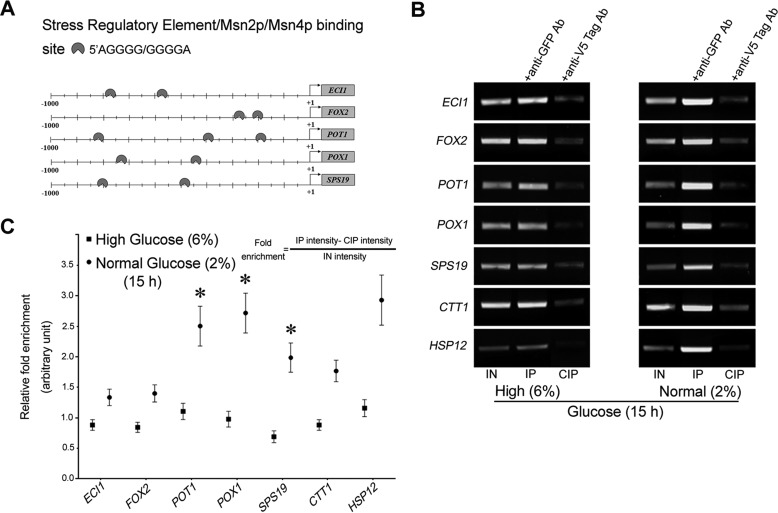

Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirms that Msn2 occupies STREs of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism under glucose limitation

It has been shown that Msn2 and Msn4 bind to a conserved STRE site present in the promoters of their target genes. Pattern match tool (Saccharomyces Genome Database) analysis of the promoter sequences of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism revealed the presence of an STRE site for Msn2/Msn4 (Fig. 4A). To evaluate Msn2 occupancy on the promoter region of the genes ECI1, FOX2, POT1, POX1, and SPS19, a ChIP assay was performed in WT cells harboring pvt100U-MSN2-GFP and grown on 2 and 6% glucose for 15 h. The data revealed that Msn2 occupied the promoter regions of these genes under glucose-depleted conditions (Fig. 4B). In addition, relative binding was more intense in 2% glucose-grown cells than in 6% glucose-grown cells (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that Msn2 occupies STREs of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism under glucose-limitation conditions.

Figure 4.

ChIP-PCR assay of Msn2-GFP binding to β-oxidation genes. Chromatin was isolated from WT-pVT100-Msn2-GFP cells subjected to a ChIP-PCR assay using an anti-GFP antibody to determine the occupancy of Msn2 on β-oxidation-specific gene promoters. An anti-V5 epitope antibody was used as a negative control. A, schematic representation of Msn2/Msn4/STRE binding site. B, agarose gel showing IN and IP ChIP-PCR products. C, relative fold enrichment was calculated by the formula provided in the figure (upper panel). The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3), as fold enrichment (arbitrary unit). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*).

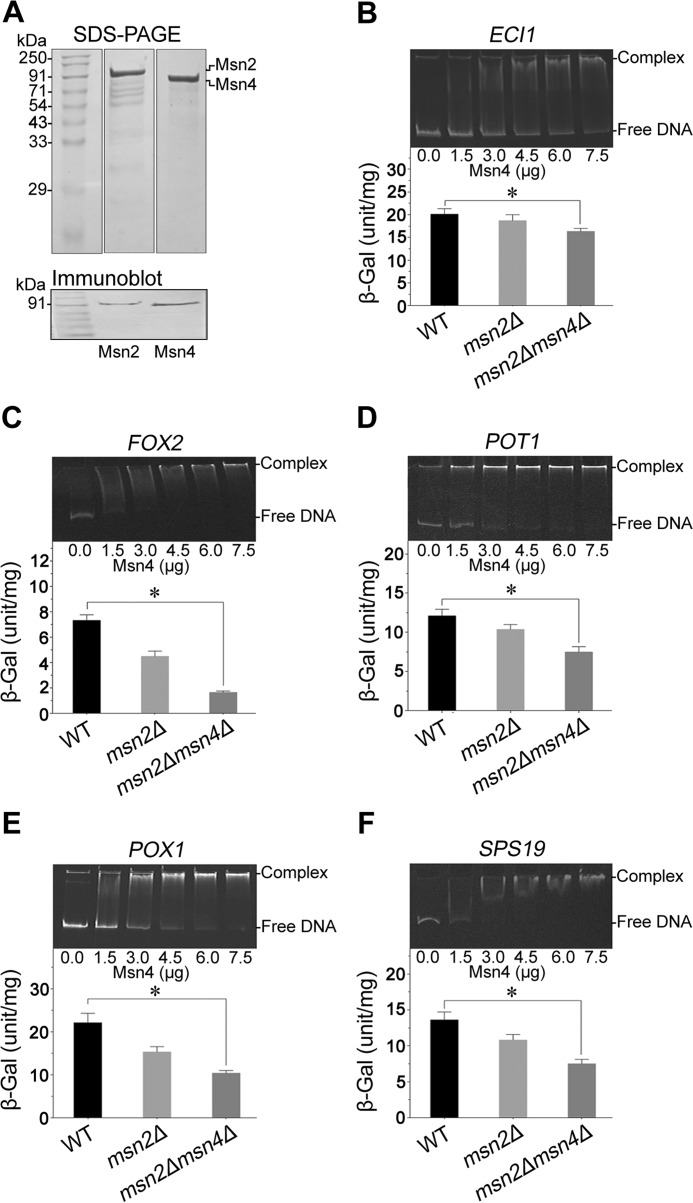

The Msn2 transcription factor positively regulates β-oxidation genes

In addition to promoter occupancy, a β-galactosidase assay was performed to determine the in vivo effect of Msn2 on the expression of major genes involved in β-oxidation (ECI1, FOX2, POT1, POX1, and SPS19). WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells harboring YEp357-ECI1pro, YEp357-FOX2pro, YEp357-POT1pro, YEp357-POX1pro, and YEp357-SPS19pro were grown to the stationary phase in SM−URA medium containing 2% glucose. We observed that the β-galactosidase activities of ECI1 (1.2-fold), FOX2 (4.4-fold), POT1 (1.6-fold), POX1 (2.1-fold), and SPS19 (1.8-fold)-expressing cells were lower for the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant compared with WT and the msn2Δ mutant (Fig. 5, B–F, bottom panels). These results suggest that Msn2 positively regulates expression of these genes.

Figure 5.

In vivo and in vitro interaction of Msn2/Msn4 with the promoter of β-oxidation genes. Msn2 and Msn4 were expressed by the bacterial expression vector pET-28a, purified, and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. A, the upper panel shows the purified proteins; the lower panel shows immunoblots for Msn2 and Msn4. B–F, electrophoretic mobility shift assays using Msn4 and the promoters of β-oxidation-specific genes are shown in the upper panels; β-galactosidase assays are shown in the lower panels. The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*).

EMSA confirms binding of Msn2/Msn4 to β-oxidation pathway gene promoters

To visualize DNA–protein interactions in vitro, bacterially expressed recombinant Msn2 and Msn4 were purified and confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5A). Because Msn2 and Msn4 are homologous, we performed EMSA with the Msn4-His-tagged protein and 1000-bp promoter fragments of five major β-oxidation pathway genes (ECI1, FOX2, POT1, POX1, and SPS19). An increase in the DNA-protein complex was observed with an increasing amount of protein (Fig. 5, B–F, top panels). We did not observe any DNA–protein complex with DGA1 promoter and Msn4, which was used as a negative control (data not shown). Our results clearly show that Msn4 interacts effectively with the promoter region of these β-oxidation genes.

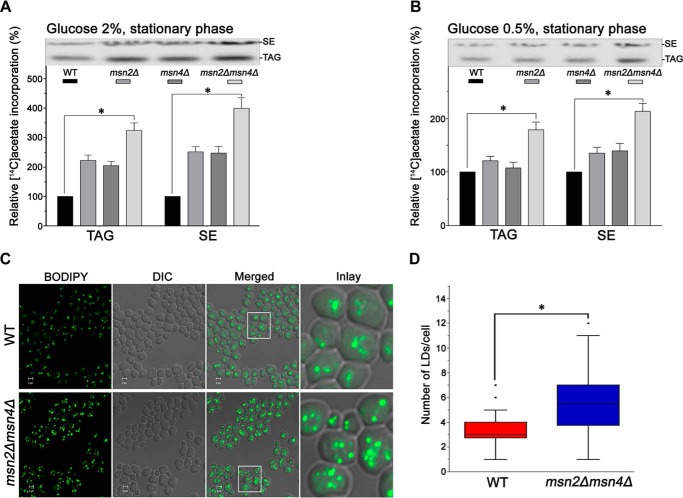

Double deletion of MSN2 and MSN4 causes an increase in nonpolar lipids as a response to lipotoxicity

Defective fatty acid metabolism causes lipotoxicity in yeast (21). Therefore, acylation of free fatty acids into nonpolar lipids, such as TAG and SE, is a defense mechanism to avoid toxicity (22). Accordingly, we analyzed the nonpolar lipid profile of WT, msn2Δ, msn4Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells grown up to stationary phase in 2% (Fig. 6A) and 0.5% (Fig. 6B) glucose followed by relative quantification of TAG and SE. WT, msn2Δ, and msn4Δ cells were used as the controls. We observed that the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant showed a prominent accumulation of TAG and SE compared with WT, msn2Δ, and msn4Δ (Fig. 6, A and B). Because TAG and SE are stored in the form of cytoplasmic lipid droplets, we further validated the increase in TAG and SE by staining the lipid droplets with BODIPYTM 493/503 stain and viewing the cells under a confocal microscope. The data showed an increase in the number of lipid droplets in msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant cells compared with WT (Fig. 6, C and D).

Figure 6.

Effect on nonpolar lipid metabolism of double deletion of MSN2/MSN4. WT, msn2Δ, msn4Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were grown in synthetic media containing [14C]acetate (0.2 μCi/ml). An equal amount (A600 = 20) of cells was harvested at the stationary phase; lipids were extracted and analyzed by silica TLC. To calculate the relative amount as a percentage (%), the dpm of radioactivity associated with the total lipids extracted from an equal amount (A600 = 20) of cells (dpm/A600) was set as 100. A and B, nonpolar lipid profile of stationary-phase cells grown in 2 and 0.5% glucose, respectively. The top panels show TAG and SE TLC results; the lower panels represent the relative [14C]acetate incorporation as a percentage. C, WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were stained with BODIPYTM 493/503. Bar, 2 μm. D, quantitative analysis of lipid droplets was performed in 100–200 cells from multiple fields of view were scored in each strain (counted manually per cell), and the number of lipid droplets was represented by a box–whiskers plot. Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*). The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). DIC, differential interference contrast.

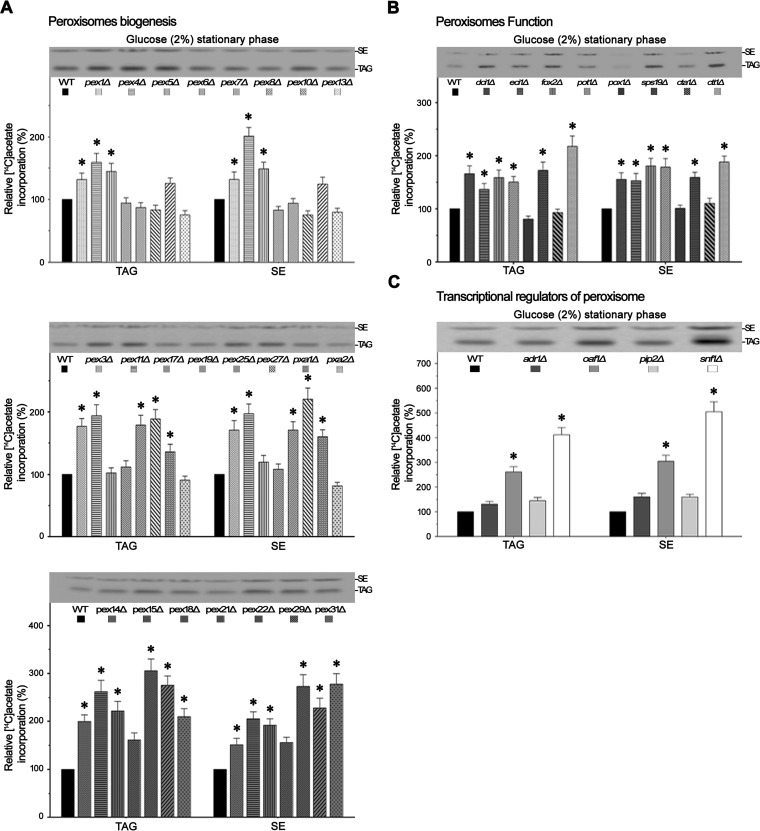

Deletion of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis, function, and regulation causes an increase in nonpolar lipids as a response to lipotoxicity

In yeast, the peroxisome is the site of fatty acid metabolism. To validate the function of MSN2 and MSN4 in fatty acid oxidation, we also analyzed the nonpolar lipid profile of single deletions of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis, function, and regulation. All deletion strains were grown in 2% glucose to the stationary phase; relative quantification of TAG and SE was performed and was compared with WT cells. Similar to msn2Δmsn4Δ cells, the deletion mutants pex1Δ, pex4Δ, pex5Δ, pex10Δ, pex3Δ, pex11Δ, pex25Δ, pex27Δ, pxa1Δ, pex14Δ, pex15Δ, pex18Δ, pex21Δ, pex22Δ, pex29Δ, and pex31Δ showed accumulation of TAG and SE compared with WT (Fig. 7A). Additionally, the fatty acid transporter mutant pxa1Δ also showed accumulation of TAG and SE but no change in pxa2Δ (Fig. 7A). Strains deleted for peroxisome function, namely dci1Δ, eci1Δ, fox1Δ, pot1Δ, sps19Δ, and ctt1Δ, also accumulated TAG and SE compared with WT (Fig. 7B). Similar to the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant, oaf1Δ and snf1Δ showed significant increases in TAG and SE levels (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Effect of peroxisome genes on nonpolar lipid metabolism. All deletion strains were grown in synthetic media containing [14C]acetate (0.2 μCi/ml). An equal amount (A600 = 20) of cells was harvested at the stationary phase; total lipids were extracted and resolved on a silica TLC plate using a nonpolar solvent system. Corresponding TAG and SE bands were scraped off and counted using a liquid scintillation counter. The dpm of radioactivity associated with TAG and SE is represented as relative [14C]acetate incorporation as a percentage. The top panels represent TAG and SE bands; the lower panels represent the relative [14C]acetate incorporation as a percentage (%) in single-deletion strains. A, peroxisome biogenesis. B, function. C, transcription factors. The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*).

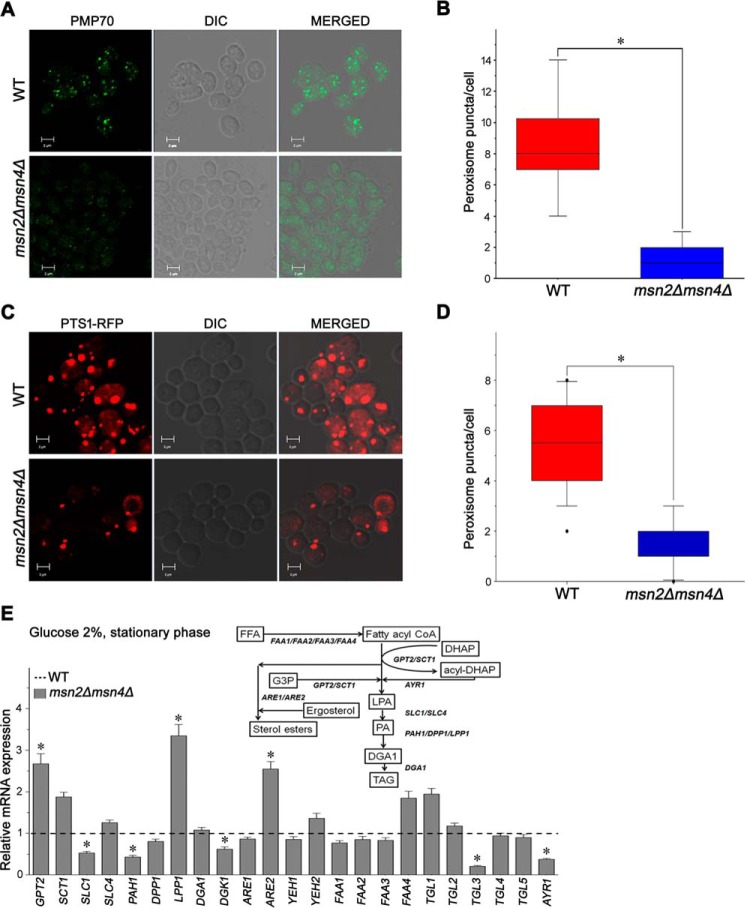

Immunofluorescence microscopy reveals that msn2Δmsn4Δ has a low number of peroxisomes

We performed an immunofluorescence assay using confocal microscopy for the visualization of peroxisomes with anti-PMP 70 (peroxisomal membrane protein 70) antibodies in WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells grown to the stationary phase in 2% glucose (Fig. 8, A and B). Our results showed a relatively low number of peroxisomes in the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant compared with WT cells. Taken together, these data suggest that Msn2 and Msn4 regulate fatty acid metabolism in budding yeast.

Figure 8.

Peroxisome localization and quantitative expression analysis of genes involved in lipid metabolism. WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were grown to the stationary phase in a synthetic medium containing 2% glucose. A, immunofluorescent peroxisomes were visualized under a confocal microscope using the anti-PMP 70 antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled secondary antibody. B, to quantify the peroxisomes puncta/cell, 100 cells from multiple fields of view were scored in each strain (counted manually per cell), and the number of peroxisomes puncta was represented by a box–whiskers plot. C, WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells harboring the RFP fused with the C-terminal peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1) construct were grown up to the stationary phase in a synthetic medium, SM-uracil-methionine containing 2% glucose. Peroxisomes were visualized under a confocal microscope. D, the graph represents the quantification of peroxisome puncta/cell. To quantify the peroxisomes puncta/cell, 100 cells from multiple fields of view were scored in each strain, and the number of peroxisomes puncta was represented by a box–whiskers plot. E, quantitative expression analysis of genes involved in lipid metabolism in the msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant. Expression of genes in WT cells was set as 1. ACT1 (actin) was used as an endogenous control. The values are presented as the means ± S.E. (n = 3). Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*). DIC, differential interference contrast.

RFP-PTS1 localization microscopy revealed that msn2Δmsn4Δ has a low number of peroxisomes

We performed the RFP-PTS1 localization in WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ mutant cells grown up to stationary phase in 2% glucose. The cells were observed under a confocal microscope for the visualization of peroxisomes (Fig. 8, C and D). Our result showed that the number of peroxisomes in msn2Δmsn4Δ strain were less than WT cells. These data suggested that Msn2 and Msn4 may have a regulatory effect on peroxisome in budding yeast.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated the novel function of stress regulatory transcription factors Msn2 and Msn4 in fatty acid metabolism under glucose-limiting or stationary-phase conditions. Glucose is the preferred carbon source for S. cerevisiae and is required for exponential cell division. Glucose depletion halts yeast cell division and allows them to enter into the diauxic shift, followed by the stationary phase. Our study provides evidence for the role of Msn2 and Msn4 in maintaining energy homeostasis during carbon source starvation stress via regulation of the induction of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism. The results of this study provide clear evidence that Msn2p/Msn4 positively regulates expression of genes involved in β-oxidation pathways in response to the low-glucose conditions that occur during the stationary phase of growth.

The Msn2/Msn4 nuclear localization signal is a direct target of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (4), and cAMP levels increase in a glucose-dependent manner, serving as a common indicator for glucose, nitrogen, and phosphate depletion in yeast (23). In yeast, peroxisome biogenesis and proliferation occurs during the postdiauxic phase (24) or during chronological aging, and fatty acid transporters are up-regulated to direct fatty acids toward β-oxidation (13).

Increased levels of MSN2 and MSN4 transcripts in WT cells, the rapid translocation of Msn2-GFP from the cytosol to the nucleus in response to low glucose and the consistent localization of Msn2-GFP in the nucleus in the presence of non-favorable carbon sources further strengthen our hypothesis. Deletion of both MSN2 and MSN4 causes a reduction in the transcript levels of genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis and function. However, fatty acid β-oxidation is important for a cell to maintain fatty acid homeostasis, and excess free fatty acids are toxic (25). Indeed, strains defective in fatty acid metabolism and peroxisome biogenesis are unable to grow on oleate or fatty acid-supplemented medium (21). Studies showed that double mutation of FAA1 and FAA4 genes caused defective growth in oleate (26). Our data showed that all major β-oxidation genes (Fig. 3C) and FAA1, FAA2, and FAA3 are down-regulated, and FAA4 is up-regulated in msn2Δmsn4Δ strain in stationary phase (Fig. 8E). Moreover, immunofluorescence microscopy with an anti-PMP 70 antibody (Fig. 8, A and B) and RFP-PTS1 localization experiment (Fig. 8, B and D) suggested there are fewer peroxisomes in the msn2Δmsn4Δ strain. Because of down-regulation of major β-oxidation genes and an overall lower number of peroxisomes, double mutants of MSN2 and MSN4 showed complete inhibition of growth on a medium containing fatty acids as the sole carbon source. Further conclusions are based on the results of the ChIP assay, which revealed increased occupancy of Msn2 on the promoters of β-oxidation genes under low-glucose conditions. The heat shock proteins Hsp12, Hsp30, and Ctt1 are well-known targets of Msn2/Msn4 (27). Consistent with this report, we also observed increased occupancy of Msn2 on the promoters of the genes HSP12, HSP30, and CTT1, which were used as positive controls. Furthermore, in vitro binding and β-galactosidase reporter analysis showed that the transcription factors Msn2 and Msn4 are positive regulators of β-oxidation genes. Yeast strains defective in fatty acid metabolism are reportedly defective in peroxisome proliferation (21, 28). In accordance with this observation, immunofluorescence microscopy with an anti-PMP 70 antibody and peroxisome, RFP-PTS1 localization studies revealed that double deletion of MSN2 and MSN4 reduced the number of peroxisomes.

As reported above, excess free fatty acids are toxic to cells, but an increase in acyltransferase activity can protect the cell from fatty acid toxicity (29–31). Therefore, acylation of free fatty acids is an essential, evolutionary conserved process to avoid fatty acid toxicity (31). In S. cerevisiae, Snf1p, Adr1p, Oaf1p, and Pip2p are transcription factors known to regulate peroxisomal genes (32–34), and it has been reported that deletion of SNF1 results in accumulation of nonpolar lipids (35). Consistent with these reports, our data also show accumulation of nonpolar lipids in msn2Δmsn4Δ. The increased expression levels of genes involved in the biosynthesis of nonpolar lipids further validate the above findings.

All organisms have the ability to sense and respond to nutrients, including glucose, related sugars, lipids, and amino acids. Any abnormality in the homeostasis of these important nutrients triggers nutrient sensing and signaling pathways. Energy extraction from different sources is a vital process for any organism; in fact, dedicated, evolutionary conserved pathways exist across eukaryotes (36, 37). Any abnormality in these pathways causes metabolic disorders. For example, an abnormality in glucose sensing and signaling causes diabetes and related diseases (38), an abnormality in fatty acid β-oxidation causes peroxisome disorders (39, 40), and other abnormalities in lipid sensing and signaling cause obesity and related diseases in animals. In yeast, the peroxisome is the sole site of fatty acid metabolism, in contrast to all other eukaryotic organisms, in which lipid metabolism also occurs in mitochondria (41). Carbon source starvation is the major stress for yeast cells, and previous studies have shown that glucose limitation in the growth medium causes a switch from fermentation to a respiratory mode but that alternative carbon sources, such as fatty acids, are metabolized for energy production (42). In the present study, we elucidated the role of Msn2/Msn4 as a regulator of fatty acid metabolism in S. cerevisiae.

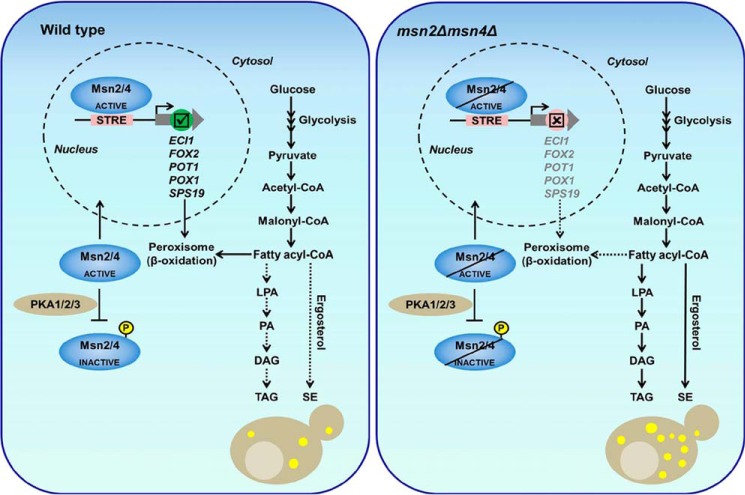

In summary, the model depicts that under low glucose conditions, activated MSN2/MSN4 localizes to the nucleus and binds to the promoter of fatty acid oxidation genes and activates their expression, whereas the absence of MSN2/MSN4 causes the defects in fatty acid metabolism and accumulated fatty acids pool acylated to nonpolar lipids such as triacylglycerol and steryl esters to avoid lipotoxicity (Fig. 9). These transcription factors have an important function in the management of energy imbalance under stationary-phase conditions. When glucose depletion occurs in the cell, Msn2/Msn4 transcription factors bind to the promoter of and positively regulate β-oxidation genes, and accumulation of nonpolar lipids in cells is a survival mechanism against fatty acid toxicity.

Figure 9.

Model depicting the role the of Msn2/Msn4 transcription factors in fatty acid metabolism in budding yeast. We propose that the Msn2/Msn4 transcription factors positively regulate β-oxidation genes and provide energy during stationary-phase conditions. In the msnΔ2 msn4Δ strain, the fatty acid pool shifted more toward TAG and SE to avoid fatty acid toxicity, ultimately resulting in “obese” yeast cells. The dotted lines represent the slow flow of metabolites, and the bold lines represent the fast flow of metabolites.

Experimental procedures

Materials

All chemicals used in this study were of reagent grade. Yeast nitrogen base without amino acids was obtained from Difco, and yeast synthetic drop-out medium supplements without uracil, histidine, leucine, and tryptophan were obtained from Sigma. Sodium oleate was obtained from Bio-basic Inc. Silica TLC plates were purchased from Merck. Restriction endonucleases and phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase were obtained from New England Biolabs. Yeast expression vectors, a fluorescence-based EMSA kit, and a peroxisome labeling kit were purchased from Molecular Probes and Life Technologies (Invitrogen BioServices, Bangalore, India). A Life Technologies cDNA synthesis kit and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Tween 40, glass beads, Folin's reagent, DNA purification kits, oligonucleotides, and an anti-monoclonal His6 antibody were obtained from Sigma. A yeast transformation kit was obtained from Clontech. Radiochemical [14C]acetate was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Yeast deletion strains were purchased from Euroscarf. Yeast expression vectors and a LacZ promoterless vector for yeast were obtained from ATCC. All solvents used for lipid analysis were obtained from Loba Chemie.

Yeast strains, media, and culture conditions

The yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The yeast strains used were derived from an S. cerevisiae haploid strain (BY4741: MATα; HIS3Δ1; LEU2Δ0;MET15Δ0; URA3Δ0). Escherichia coli DH5α was used for cloning and plasmid propagation, and E. coli BL21-AITM strains were used for heterologous protein expression. The msn2Δmsn4Δ strain used in this study was described previously (43). DH5α and BL21-AITM cells were grown in LB broth medium containing 1% tryptone, 1% NaCl, and 0.5% yeast extract and incubated at 37 °C. Ampicillin (100 mg/liter) or kanamycin (50 mg/liter) was added for the selection of cells carrying the respective plasmid. Recombinant protein was induced in E. coli (BL21-AITM) by adding 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 4–6 h at 37 °C. For recombinant and LacZ protein expression in yeast, 2% galactose or 2% glucose, respectively, was used as the carbon source in SM medium devoid of uracil (SM−URA). Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C with constant shaking at 200 rpm in a shaker-incubator chamber.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15Δ (lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk+) phoA supE44 λ-thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB (rB− mB−) gal dcm araB::T7RNAP-tetA | Invitrogen |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| BY4741 | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0; | Euroscarf |

| msn2Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YMR037C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| msn4Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YKL062W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| dci1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YOR180C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| eci1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YLR284C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| fox2Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YKR009C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pot1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YIL160C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pox1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGL205W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| sps19Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YNL202W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pxa1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YPL147W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pxa2Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YKL188C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| cta1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR256C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| ctt1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGR088W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YKL197C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex3Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR329C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex4Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGR133W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex5Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR244W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex6Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YNL329C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex7Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR142C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex8Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGR077C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex10Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR265W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex11Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YOL147C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex13Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YLR191W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex14Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGL153W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex15Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YOL044W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex17Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YNL214W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex18Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YHR160C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex19Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDL065C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex21Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGR239C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex22Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YAL055W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex25Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YPL112C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex27Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YOR193W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex29Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR479C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pex31Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YGR004W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| oaf1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YAL051W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| adr1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR216W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| pip2Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YOR363C::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| snf1Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YDR477W::kanMX4 | Euroscarf |

| msn2msn4Δ | BY4741; Mat a; his3Δ 1; leu2Δ 0; met15Δ 0; ura3Δ 0;YMR037C::kanMX4;YKL062W::LEU2 | Ref. 43 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-28a(+) | E. coli expression vector for polyhistidine-tagged proteins | Novagen |

| pVT100U-mtGFP | Yeast yEGFP, N-FUS vectors with uracil selection marker for yeast | ATCC |

| YEp357 | Yeast promoter less vector with lacZ, uracil selection marker for yeast | ATCC |

| pET-28a-MSN2 | MSN2 gene clone in E.¢oli expression vector with N-terminal His6 tag fusion | This study |

| pET-28a-MSN4 | MSN4 gene clone in E. coli expression vector with N-terminal His6 tag fusion | This study |

| pVT100U-MSN2-GFP | MSN2 gene cloned yeast expression vector with N-terminal GFP. | This study |

| pUG36-RFP-PTS1 | Plasmids expressing monomeric RFP bearing the PTS1 sequence | Jeffrey E. Gerst |

| YEp357-ECII pro | lacZ reporter gene containing the ECI1 promoter | This study |

| YEp357-FOX2 pro | lacZ reporter gene containing the FOX2 promoter | This study |

| YEp357-POT1 pro | lacZ reporter gene containing the POT1 promoter | This study |

| YEp357-POX1 pro | lacZ reporter gene containing the POX1 promoter | This study |

| YEp357-SPS19 pro | lacZ reporter gene containing the SPS19 promoter | This study |

BY4741 and all other mutants, single or double genes, were routinely maintained at 30 °C on YPD complete medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and 2% agar, pH 6.5) or in standard SM medium (yeast nitrogen base, 6.7 g; amino acid drop out, 1.92 g and uracil, 76 mg/liter, pH 6.5) supplemented with either 2% dextrose or 2% galactose or glycerol as the carbon source. The cells were grown to the stationary phase (unless otherwise mentioned) in YPD medium and further subcultured in fresh SM+URA medium containing glucose or any other carbon source as required in the experiments. Cells harboring yeast expression plasmids were grown in SM−URA medium with an appropriate carbon source.

Plasmids

Yeast genomic DNA was prepared as previously described (44). The MSN2 and MSN4 genes were amplified from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 3. The MSN2 gene was cloned into the yeast expression vector pVT100U-mtGFP using the HindIII and SmaI restriction sites, and the construct was named pVT100U-MSN2-GFP. Clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The MSN2 and MSN4 genes were cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET28(a) using BamHI and NotI for MSN2 and BamHI and XhoI for MSN4. The constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing and named pET28a-MSN2 and pET28a-MSN4, respectively. The constructs used for promoter validation were generated by cloning the 1000-bp upstream region of ECI1, FOX2, POT1, POX1, and SPS19 into the promoterless yeast expression vector yEP357 using restriction sites KpnI and PstI, which are common to all. The constructs, named YEp357-ECI1pro, YEp357-FOX2pro, YEp357-POT1pro, YEp357-POX1pro, and YEp357-SPS19pro, were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study

| No. | Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| pET28(a) | |||

| 1 | MSN2 gene | CGATGGATCCATGACGGTCGACCATGATTT | ATATTGCGGCCGCTTAAATGTCTCCATGTT |

| 2 | MSN4 gene | ATATGGATCCATGCTAGTCTTCGGACCTA | AGATCTCGAGTCAAAAATCACCGTGCT |

| pVT100-GFP | |||

| 3 | MSN2 gene | ATAAAGCTTATGACGGTCGACCATGATTTC | ATACCCGGGAGAATGTCTCCATGTTTTTTATG |

| YEp357 | |||

| 4 | ECI1 pro | ATATGGTACCGGAACCAAATGGAACTCGTTCTT | CGATCTGCAGTTGCCTAATTTCTTGCGACATA |

| 5 | FOX2 pro | ATATGGTACCTCTGATACAATCGATCAGTGCGTG | GCATCTGCAGGAAGGATAAATTTCCAGGCAT |

| 6 | POT1 pro | ATATGGTACCGAAAAAGTTGCAAAAAGC | ATCTGCAGACTTTGTAGTCTTTGAGACATTGC |

| 7 | POX1 pro | ATATGGTACCCACTCAACCACCTCCAAAAAATAA | GCATCTGCAGAATAGTAGTACGTCTCGTCATATC |

| 8 | SPS19 pro | GCATGGTACCTGAAAGCAACTGCCAACTTCTA | GCATCTGCAGCAAAGTGTTTGCTGTATTCATAGT |

| 9 | DGA1 pro | GAGATTATTGCCTTTACTGCGCC | GAATGTTCCTGACATTTATGTGACTGTTC |

| qRT-PCR | |||

| 10 | ACT1 qRT | ACTTTCAACGTTCCAGCCTTCT | ACACCATCACCGGAATCCAA |

| 11 | MSN2 qRT | AGAACGATATGCTGCCGAATTC | CGCCACTTTCGCAATAACG |

| 12 | MSN4 qRT | GGATTGATGGACCCGGTATTG | CCAAAGGTATATTCCGGCGAA |

| 13 | ECI1 qRT | TGGGTGTCAAATTTTGTCGC | AACCCTATTGCTGGTCCATTCA |

| 14 | FOX2 qRT | CTCCCAATGAACAAGGCTCAG | CCAGATTGCATGAGACTTCCC |

| 15 | POT1 qRT | GGAGAGCGCCATGGGTAAG | CGATGGCAGACCTGTTAGCA |

| 16 | POX1 qRT | GCAGGAGAGAGGTGCCACTT | CAGCCCTAGTCTGCAGCTGG |

| 17 | SPS19 qRT | ATGGTGTGCCGTTTCAAGGA | CGAACGTATACCCAGAGGCC |

| 18 | PEX1 qRT | TCTAAGTTGTTGGGCGGGAG | ACAACTGCTGCTCGGATTCA |

| 19 | PEX2 qRT | ACCAACCCATACCAGATCGC | CAGAGGATCCACAGGCATCG |

| 20 | PEX3 qRT | AGCGTGAACGAATACCTGGC | AGGAAAACGAGCTGGAGACG |

| 21 | PEX4 qRT | ATGACCCCATAGCGAACCC | TGACGGCCCAGAAATTATAGCT |

| 22 | PEX5 qRT | AACATGGCGAATATGCAAAGG | GAAAAAGGTGGAAGCCTGCC |

| 23 | PEX6 qRT | TTCCAGACTGCAGCGTCGT | AAGCCAGCCTCCAACTCTTG |

| 24 | PEX7 qRT | CAAGGTTTTAGTGGGTACGGTGT | AATTTTCCATTCCCAACCAGG |

| 25 | PEX8 qRT | CCTGCTAGACGAAATCGCG | ACTGCGATCGGAAAAGTGCT |

| 26 | PEX9 qRT | CGCGCGAGATGCTAGAACAA | TTTATCTGCCGGTAGTGCGG |

| 27 | PEX10 qRT | TCCTAACCTCTACGCTCGGG | TCATGTTCTGAACGCTCCTGT |

| 28 | PEX11 qRT | TCGCTGGTCCAATTGGTGTT | GACAAACGCAGCAATCTGGG |

| 29 | PEX19 qRT | GAAGCAGAGCCCGATGATGT | CCTGTACGCCATCACTGTCC |

| 30 | PXA1 qRT | TGCGACATGCTCCGTTTTTG | TGCTACTCCCACAGTTCCCA |

| 31 | PXA2 qRT | GGACCGTTTAACCCGAAGGA | TCAACTTCCGCTCCCAAAGT |

| 32 | LPX1 qRT | TGCAGACTTTTGCGCCTTTC | TTTTGCGGAGGACACCAGTT |

| 33 | GPT2 qRT | GGTGCCAACCATCCTTGTGT | ACTTTCCCGCTGATGTCTTCA |

| 34 | SCT1 qRT | CGACATCCGTTGCACCTTCT | TAAGACGGCCTGTGCGATTT |

| 35 | SLC1 qRT | CAAGCGTGCTCTATGGGTTTT | CCTGTTGTGCCAAATGGAAA |

| 36 | SLC4 qRT | AACCTGGTTTCCGCTCAACT | TACAAAGCCCCTGTCGCAAA |

| 37 | PAH1 qRT | CTTGTGTCGCCCGTGATG | ACCCTCGGTTCCTCCTTCTAAG |

| 38 | DPP1 qRT | TCCTCTTCCGTTCAAACCATTG | GGTGTCGTCAATATCACTGA |

| 39 | LPP1 qRT | AGTTGCATTTGGTGCCCTTT | GCTAGAACAGCTCCAGAGACAACA |

| 40 | DGA1 qRT | TGACTATCGCAACCAGGAATGT | AACGCACCAAGTGCTCCTATG |

| 41 | DGK1 qRT | GGGACCGAAGATGCCATTG | ACTTTCGCCGAGACTTGATGA |

| 42 | ARE1 qRT | TGTTCCCCGTCCTCGTGTA | CGCACACCTTCTCCAACACA |

| 43 | ARE2 qRT | GCAACTCACCAGCCAATGAA | ATGCGACGTCTCCGTTTGA |

| 44 | YEH1 qRT | TGGAGACCGAAGATGGGTTTG | AGCATCAAAATGGGTGGCCT |

| 45 | YEH2 qRT | TCAGAGAACGGTGATGGAAATG | TCCGCAAGCGGCAATGTTT |

| 46 | FAA1 qRT | CTCCAATCAGTCGGGATGCT | ATGTCTCGGTTAAACCGTAACCA |

| 47 | FAA2 qRT | TCATGACGAGCTCCGTATGC | CTTGTTCTACCTGCTCCAATGAAA |

| 48 | FAA3 qRT | TAGAGTCAAGAAGCGGCCCTTA | CATCTCGTTTTCCACCCTTGTT |

| 49 | FAA4 qRT | CCCATCGAAAAAACATGGTTGTA | ATCAGCCCACGTCCAATGTC |

| 50 | TGL1 qRT | TCATCCAACGCATGGTCTCA | TCATCCGCTTCATCAGCTTGT |

| 51 | TGL2 qRT | AGAGCAATGGCTTTGGATGC | CCCCCATTGAGTGTGCGATT |

| 52 | TGL3 qRT | GGTCTCGCCAAAGAAACAATG | ACCCCAGAAATGCCAACAA |

| 53 | TGL4 qRT | CAAGTATGGGCCGGCTAATG | CATGGCAGGTGTTTCAATGC |

| 54 | TGL5 qRT | CCCAGAAAAAACACGCCATCT | GCACTCGTCGATTGTTTTCCA |

| 55 | AYR1 qRT | GCCCTTGCCTGAAACCTCAA | ATCAGCTGGCATGGGCTTAT |

| ChIP primer | |||

| 56 | ECI1 ChIP | CCAACGCCTGACCTTTCTCAGC | CCTCCACCAAAACCTCATTTTGC |

| 57 | FOX2 ChIP | CTAGCAGCACAGTAGATTTCACTAACC | AAGTCCTTCTACCTTTCAACACTGG |

| 58 | POT1 ChIP | CGTTCAAATTCAATTCTTCCAATTTACGG | CTCAGAGCCACAAGAAATAACCATTCG |

| 59 | POX1 ChIP | CGATTGCAACAGAGTTTGTACCG | CGTAAATATAGGGCTTAAAATGTGTCAGG |

| 60 | SPS19 ChIP | GTTATTCTCGTCCAGGTTTCTTTCGG | ACAAGAGAGTACTGGTATAAAAGGGACC |

| 61 | CTT1 ChIP | GAATTGTGTTCGCTGGTAAGAGAAAATAGG | GTGAAGCTGAGCTGATTGATCTTATTGG |

| 62 | HSP12 ChIP | CTTTTCCTCTTGATACACAGAAAAGTGGG | AATTGAGGAAGTAGAACGCAATTCACC |

pro, promoter; qRT, quantitative real-time PCR.

In vivo [14C]acetate labeling of lipids

WT and yeast deletion strains were precultured overnight in YPD medium containing 2% glucose. An equal amount of cells (A600 = 0.2/5 ml) was subcultured in SM+URA medium containing an appropriate amount of glucose as required in the experiment and 0.2 μCi/ml [14C]acetate. The cells were allowed to grow until the required growth phase. An equal amount of cells (A600 = 20) from each sample was harvested by centrifugation, and the cell pellet was washed with ice-cold water. Lipids were extracted using the methods of Bligh and Dyer (49), with slight modifications. Briefly, the cells were broken with glass beads in the presence of chloroform, methanol, and 2% orthophosphoric acid (1:2:1, v/v/v) by vigorous vortexing for 2–3 min. Total lipids were extracted using an equal ratio of chloroform, methanol, and 2% orthophosphoric acid (1:1:1, v/v/v). The extracted lipids were dried in a SpeedVacTM concentrator and separated on a TLC plate using petroleum ether, diethyl ether, and acetic acid (70:30:1, v/v/v) as the solvent system. The TLC plates were exposed to radiosensitive screens for 16 h and scanned with a Typhoon FLA 9500 laser scanner (GE Healthcare). Lipid species were identified with the help of lipid standards co-migrating with the lipid samples. The TAG and SE bands were scraped off of the TLC plate, extracted from the silica, and dissolved in a toluene-based scintillation fluid. The radioactivity associated with TAG and SE was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer Micro Beta2 2450 microplate counter).

Lipid droplet staining and confocal microscopy

An equal amount of cells (A600 = 1) was fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with 1× PBS to remove the formaldehyde and stained with BODIPYTM 493/503 (final concentration, 1 μg/ml) by incubation in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were washed with 1× PBS to remove the excess stain and resuspended in 1× PBS containing 40% glycerol. An aliquot of the cells was loaded onto a slide precoated with 2% agarose, and the lipid droplets were visualized under a confocal microscope.

Growth curve and spotting assay

Wild-type, msn2Δ, msn4Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were pregrown overnight in YPD medium containing 2% glucose. An equal number of cells was inoculated into three individual tubes containing SM+URA medium. As the carbon source, tube 1 contained 2% glucose, tube 2 contained 0.5% glucose and 1 mm sodium oleate, and tube 3 contained 1 mm sodium oleate. Because sodium oleate was dissolved in 0.03% Tween 80 (v/v), it was added to all three tubes to maintain uniformity in the experiment. The cells were allowed to grow at 30 °C at 200 rpm, and the absorbance was measured every 3 h. For the spotting assay, the cells (A600 = 1) were 10-fold serially diluted and spotted onto solid agar plates containing the same media as in tubes 1, 2, and 3. Images were taken on day 3 for glucose plates and on day 8 for oleate plates.

Expression, purification, and confirmation of recombinant proteins

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring the pET28a-MSN2 and pET28a-MSN4 plasmids were precultured in 5 ml of LB medium with 50 mg/liter kanamycin and grown overnight at 37 °C. The cells from the preculture were then inoculated into 100 ml of LB medium containing 50 mg/liter kanamycin and grown at 37 °C to A600 = 0.6–0.9. The cells were induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 3–4 h at 37 °C and harvested. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, 1 mm PMSF, and 10% (v/v) glycerol. The cells were lysed by sonication, and the lysed sample was subjected to a high-speed centrifugation (10000 × g) for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing the recombinant protein was allowed to bind to the Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid matrix at 4 °C for 6 h with rotation on a Hula Mixer®. Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid-bound His-tagged protein was washed with a two-column volume of lysis buffer containing 20 mm imidazole, followed by a second wash with 40 mm imidazole in lysis buffer. The bound protein was then eluted with elution buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 250 mm imidazole, 1 mm PMSF, and 10% (v/v) glycerol. The protein fractions (1 ml each) were collected and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis using an anti-His6 monoclonal antibody raised in mice. The purified protein was subjected to dialysis and was then used for EMSA.

β-Galactosidase assay

WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were transformed with the control plasmid YEp357 and the promoter-containing plasmids YEp357-ECI1pro, YEp357-FOX2pro, YEp357-POT1pro, YEp357-POX1pro, and YEp357-SPS19pro. Transformants were grown to the stationary phase in SM−URA medium containing 2% glucose. Cell-free lysates were prepared, and an equal concentration of protein extract was used to measure β-galactosidase activity. Specific activity is expressed in nmol/min/mg protein.

RNA isolation and expression analysis

Expression profiling of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, peroxisome biogenesis, function, and regulation was performed by qPCR analysis. WT, msn2Δ, and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were grown to the stationary phase in a synthetic medium containing 2% glucose, and total RNA was extracted using the Nucleospin RNA II RNA isolation kit, followed by cDNA synthesis using 1 μg of RNA. An equal amount of cDNA (1:20 dilution) was used for expression analysis with the Power SYBR Green PCR master mix. Actin was used as an endogenous control, and the primers used for qPCR are listed in Table 3. Three independent experiments were performed, and each experiment was carried out in triplicate. The data are represented as relative mRNA expression.

EMSA

The promoter sequences of the ECI1, FOX2, POT1, POX1, and SPS19 genes (1 kb) were amplified from BY4741 genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 3. The gel-purified PCR products were used for EMSA. Increasing concentrations (0, 1.5, 3.0, 4.5, 6.0, and 7.5 μg) of recombinant Msn4 were incubated with 1 μg of PCR product in a binding buffer composed of 10% glycerol, 10 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.9, 4 mm Tris-Cl, 1 mm DTT, 60 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 100 nm ZnSO4. The reaction was performed at 30 °C for 15 min, and the DNA-protein complex was resolved by 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a running buffer composed of 50 mm Tris base, 400 mm glycine, 2 mm EDTA, pH 8.0; the gel was stained with SYBR Green nucleic acid stain. The complex was visualized at 300 nm using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system. Negative control EMSA was also performed with upstream promoter sequence of the DGA1 gene, which does not possess binding site for Msn2/Msn4.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Peroxisomes were visualized by epitope tagging of PMP 70 using SelectFX® Alexa Fluor® 488 peroxisome labeling kit (S34203, lot 1351930). Immunofluorescence was carried out as described (45), with a slight modification. WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were pregrown overnight in YPD medium containing 2% glucose. An equal amount of cells was subcultured in fresh SM+URA medium containing 2% glucose and grown to the stationary phase. An equal amount of cells (A600 = 2) from each strain was harvested and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were converted to spheroplasts by treatment with zymolyase (2 mg/ml) in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, and 1 m sorbitol for 1 h at 37 °C. The spheroplasts were harvested by centrifugation at 2,655 × g for 5 min, resuspended in PBS, and immobilized on a polylysine-coated glass coverslip. The immobilized spheroplasts were permeabilized by immersing the coverslips in ice-cold methanol for 6 min, followed by ice-cold acetone for 30 s. After air drying, the coverslips were blocked for 6 h in 1× normal goat saline. The cells were also treated with a 1,000-fold dilution of the anti-PMP 70 rabbit IgG fraction and incubated at room temperature for 6 h, followed by 2 h of incubation in 1000-fold-diluted Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies. The coverslips were washed with 1× PBS and observed under a confocal microscope.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

A ChIP assay was carried out as described by Yadav and Rajasekharan (46–48), with slight modification. ChIP-grade monoclonal anti-GFP (SAB2702211, lot 41232) and anti-V5 (V8173, lot 012M4796) antibodies and protein A-agarose Fast Flow (P3476, lot SLBL3639V) from Sigma-Aldrich were used in the assays. Briefly, wild-type cells harboring the pVT100U-MSN2-GFP construct were grown overnight in SM−URA medium containing 2% glucose. An equal number of cells were subcultured for 15 h in two different flasks containing 100 ml of SM−URA medium with 6 or 2% glucose. The cells were fixed with p-formaldehyde at a final concentration of 1% for 15 min. An excess amount of p-formaldehyde was quenched with 2.5 m glycine. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,214 × g for 5 min in 50-ml Falcon tubes, and the cell pellets were washed with 1× PBS and stored at −80 °C until use. To coat the anti-GFP antibody onto the protein A-agarose beads, 40 μl of protein A-agarose beads were first equilibrated with 1 ml buffer A (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) by centrifugation at 425 × g for 1 min and resuspended in 70 μl of the same solution. The anti-GFP antibody (2 μg) was added to the equilibrated beads and allowed to bind for 2 h at 4 °C. Unbound antibodies were removed by centrifugation at 425 × g for 1 min and washed twice with buffer A. The beads coated with the anti-GFP antibody were resuspended in 40 μl of buffer and stored at 4 °C until use. Harvested cells were resuspended in 400 μl of buffer A and transferred to 1.5-ml tubes. Acid-washed glass beads and a protease inhibitor mixture, EDTA-free, from Sigma (P8215) were added to the sample, which was vortexed for 40 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 956 × g at 4 °C. A SONICS Vibra cell sonicator was used to generate chromatin fragments of 300–700 bp. On ice, samples were sonicated for 15 cycles at 30% amplitude for 12 s and 1 min off. The samples were centrifuged at 17,949 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant, which contained the chromatin fragments. An aliquot of 50 μl of each sample was used for IP (immunoprecipitation), IN (input), and CIP (control immunoprecipitation), and the remaining samples were stored at −20 °C. The IP and CIP samples were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with the protein A-agarose beads coated with anti-GFP and anti-V5 antibodies, respectively. The protein A-agarose beads were washed with buffer B (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) and wash buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 250 mm LiCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate). DNA recovery from the IN, IP, and CIP samples was achieved using the PCR cleanup kit (Sigma). ChIP PCR was performed using 1% IN and 4% IP and CIP as the template. The primers used in the study are listed in Table 3. The HSP12 and CTT1 genes were used as the positive control. PCR product band intensities were quantified by densitometry analysis using ImageJ software. The results are represented as described (48).

Localization of RFP-PTS1 in peroxisome by confocal microscopy

Peroxisomes were visualized by the RFP-PTS1 peroxisomal targeting sequence construct, pUG36-RFP-PTS1 (a kind gift from Prof. Jeffrey E. Gerst, Department of Molecular Genetics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel). WT and msn2Δmsn4Δ cells were transformed with pUG36-RFP-PTS1 and selected on synthetic medium, SM−URA plate. An equal amount of cells was subcultured in fresh synthetic medium, SM-uracil-methionine containing 2% glucose, grown up to stationary phase. An equal amount of cells (A600 = 2) from each strain was harvested, immobilized on a polylysine-coated glass coverslip, and viewed under a confocal microscope (Fig. 8, C and D). The excitation at 545 nm and emission at 560–580 nm wavelength were used for monomeric RFP.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data are shown as the means ± S.E., and all quantitative data were analyzed using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and at least 100 cells of each strain were scored per experiment to quantify microscopic data. Lipids were extracted using the methods of Bligh and Dyer (49). The experiments were performed three times, and representative TLC results were shown in the figures. Significance was determined at p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

Author contributions

R. R. conceived and initiated the project. R. R. and P. K. R. designed the experiments. P. K. R. performed the experiments. M. A. executed the β-galactosidase activity assays. P. K. R. and R. R. discussed the data and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the Department of Biochemistry of the Indian Institute of Science (Bangalore, India) for help with the radioactive study.

This work was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (New Delhi, India) under the 12th 5-year plan project LIPIC (Lipidomic Center). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- STRE

- stress regulatory element

- TOR

- target of rapamycin

- TAG

- triacylglycerol

- SE

- steryl ester

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- IN

- input

- CIP

- control immunoprecipitation

- dpm

- disintegration/min.

References

- 1. Estruch F., and Carlson M. (1993) Two homologous zinc finger genes identified by multicopy suppression in a SNF1 protein kinase mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 3872–3881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart-Ornstein J., Nelson C., DeRisi J., Weissman J. S., and El-Samad H. (2013) Msn2 coordinates a stoichiometric gene expression program. Curr. Biol. 23, 2336–2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gasch A. P., Spellman P. T., Kao C. M., Carmel-Harel O., Eisen M. B., Storz G., Botstein D., and Brown P. O. (2000) Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4241–4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Görner W., Durchschlag E., Wolf J., Brown E. L., Ammerer G., Ruis H., and Schüller C. (2002) Acute glucose starvation activates the nuclear localization signal of a stress-specific yeast transcription factor. EMBO J. 21, 135–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rolland F., Winderickx J., and Thevelein J. M. (2002) Glucose-sensing and signalling mechanisms in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2, 183–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Papamichos-Chronakis M., Gligoris T., and Tzamarias D. (2004) The Snf1 kinase controls glucose repression in yeast by modulating interactions between the Mig1 repressor and the Cyc8-Tup1 co-repressor. EMBO Rep. 5, 368–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Görner W., Durchschlag E., Martinez-Pastor M. T., Estruch F., Ammerer G., Hamilton B., Ruis H., and Schüller C. (1998) Nuclear localization of the C2H2 zinc finger protein Msn2p is regulated by stress and protein kinase A activity. Genes Dev. 12, 586–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith A., Ward M. P., and Garrett S. (1998) Yeast PKA represses Msn2p/Msn4p-dependent gene expression to regulate growth, stress response and glycogen accumulation. EMBO J. 17, 3556–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norbeck J., and Blomberg A. (2000) The level of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A activity strongly affects osmotolerance and osmo-instigated gene expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 16, 121–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crespo J. L., and Hall M. N. (2002) Elucidating TOR signaling and rapamycin action: lessons from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 579–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Medvedik O., Lamming D. W., Kim K. D., and Sinclair D. A. (2007) MSN2 and MSN4 link calorie restriction and TOR to sirtuin-mediated lifespan extension in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLos Biol. 5, e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skoneczny M., and Rytka J. (1996) Maintenance of the peroxisomal compartment in glucose-repressed and anaerobically grown Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Biochimie 78, 95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lefevre S. D., van Roermund C. W., Wanders R. J., Veenhuis M., and van der Klei I. J. (2013) The significance of peroxisome function in chronological aging of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell 12, 784–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boisnard S., Lagniel G., Garmendia-Torres C., Molin M., Boy-Marcotte E., Jacquet M., Toledano M. B., Labarre J., and Chédin S. (2009) H2O2 activates the nuclear localization of Msn2 and Maf1 through thioredoxins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryotic Cell 8, 1429–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Santhanam A., Hartley A., Düvel K., Broach J. R., and Garrett S. (2004) PP2A phosphatase activity is required for stress and Tor kinase regulation of yeast stress response factor Msn2p. Eukaryotic Cell 3, 1261–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Geisbrecht B. V., Zhu D., Schulz K., Nau K., Morrell J. C., Geraghty M., Schulz H., Erdmann R., and Gould S. J. (1998) Molecular characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Δ3, Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33184–33191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Filppula S. A., Sormunen R. T., Hartig A., Kunau W.-H., and Hiltunen J. K. (1995) Changing stereochemistry for a metabolic pathway in vivo experiments with the peroxisomal β-oxidation in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27453–27457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gould S. J., and Collins C. S. (2002) Peroxisomal-protein import: is it really that complex? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith J. J., and Aitchison J. D. (2013) Peroxisomes take shape. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 803–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Roermund C. W., Ijlst L., Majczak W., Waterham H. R., Folkerts H., Wanders R. J., and Hellingwerf K. J. (2012) Peroxisomal fatty acid uptake mechanism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20144–20153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lockshon D., Surface L. E., Kerr E. O., Kaeberlein M., and Kennedy B. K. (2007) The sensitivity of yeast mutants to oleic acid implicates the peroxisome and other processes in membrane function. Genetics 175, 77–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kohlwein S. D. (2010) Triacylglycerol homeostasis: insights from yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15663–15667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conway M. K., Grunwald D., and Heideman W. (2012) Glucose, nitrogen, and phosphate repletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: common transcriptional responses to different nutrient signals. G3 (Bethesda) 2, 1003–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Casanovas A., Sprenger R. R., Tarasov K., Ruckerbauer D. E., Hannibal-Bach H. K., Zanghellini J., Jensen O. N., and Ejsing C. S. (2015) Quantitative analysis of proteome and lipidome dynamics reveals functional regulation of global lipid metabolism. Chem. Biol. 22, 412–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carballeira N. (2008) New advances in fatty acids as antimalarial, antimycobacterial and antifungal agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 50–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Faergeman N. J., Black P. N., Zhao X. D., Knudsen J., and DiRusso C. C. (2001) The acyl-CoA synthetases encoded within FAA1 and FAA4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function as components of the fatty acid transport system linking import, activation, and intracellular utilization. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37051–37059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boy-Marcotte E., Perrot M., Bussereau F., Boucherie H., and Jacquet M. (1998) Msn2p and Msn4p control a large number of genes induced at the diauxic transition which are repressed by cyclic AMP in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 180, 1044–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zipor G., Haim-Vilmovsky L., Gelin-Licht R., Gadir N., Brocard C., and Gerst J. E. (2009) Localization of mRNAs coding for peroxisomal proteins in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19848–19853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petschnigg J., Wolinski H., Kolb D., Zellnig G., Kurat C. F., Natter K., and Kohlwein S. D. (2009) Good fat, essential cellular requirements for triacylglycerol synthesis to maintain membrane homeostasis in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30981–30993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rani S. H., Saha S., and Rajasekharan R. (2013) A soluble diacylglycerol acyltransferase is involved in triacylglycerol biosynthesis in the oleaginous yeast Rhodotorula glutinis. Microbiology 159, 155–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kurat C. F., Natter K., Petschnigg J., Wolinski H., Scheuringer K., Scholz H., Zimmermann R., Leber R., Zechner R., and Kohlwein S. D. (2006) Obese yeast: triglyceride lipolysis is functionally conserved from mammals to yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ratnakumar S., and Young E. T. (2010) Snf1 dependence of peroxisomal gene expression is mediated by Adr1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10703–10714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karpichev I. V., and Small G. M. (1998) Global regulatory functions of Oaf1p and Pip2p (Oaf2p), transcription factors that regulate genes encoding peroxisomal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6560–6570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gurvitz A., Rottensteiner H., Hiltunen J. K., Binder M., Dawes I. W., Ruis H., and Hamilton B. (1997) Regulation of the yeast SPS19 gene encoding peroxisomal 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase by the transcription factors Pip2p and Oaf1p: β-oxidation is dispensable for Saccharomyces cerevisiae sporulation in acetate medium. Mol. Microbiol. 26, 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seip J., Jackson R., He H., Zhu Q., and Hong S.-P. (2013) Snf1 is a regulator of lipid accumulation in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7360–7370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Conrad M., Schothorst J., Kankipati H. N., Van Zeebroeck G., Rubio-Texeira M., and Thevelein J. M. (2014) Nutrient sensing and signaling in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 254–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Efeyan A., Comb W. C., and Sabatini D. M. (2015) Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature 517, 302–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Resnick H. E., and Howard B. V. (2002) Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 53, 245–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinberg S. J., Dodt G., Raymond G. V., Braverman N. E., Moser A. B., and Moser H. W. (2006) Peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 1733–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wierzbicki A. S., Lloyd M. D., Schofield C. J., Feher M. D., and Gibberd F. B. (2002) Refsum's disease: a peroxisomal disorder affecting phytanic acid α-oxidation. J. Neurochem. 80, 727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hiltunen J. K., Mursula A. M., Rottensteiner H., Wierenga R. K., Kastaniotis A. J., and Gurvitz A. (2003) The biochemistry of peroxisomal β-oxidation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 35–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kayikci Ö., and Nielsen J. (2015) Glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 15, fov068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yadav K. K., Singh N., Rajvanshi P. K., and Rajasekharan R. (2016) The RNA polymerase I subunit Rpa12p interacts with the stress-responsive transcription factor Msn4p to regulate lipid metabolism in budding yeast. FEBS Lett. 590, 3559–3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sambrook J., and Russell D. W. (2000) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kumar N. V., and Rangarajan P. N. (2012) The zinc finger proteins Mxr1p and repressor of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ROP) have the same DNA binding specificity but regulate methanol metabolism antagonistically in Pichia pastoris. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34465–34473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuo M.-H., and Allis C. D. (1999) In vivo cross-linking and immunoprecipitation for studying dynamic protein: DNA associations in a chromatin environment. Methods 19, 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harmeyer K. M., South P. F., Bishop B., Ogas J., and Briggs S. D. (2015) Immediate chromatin immunoprecipitation and on-bead quantitative PCR analysis: a versatile and rapid ChIP procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e38–e38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yadav P. K., and Rajasekharan R. (2016) Misregulation of a DDHD domain-containing lipase causes mitochondrial dysfunction in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 18562–18581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]