Abstract

Epidemiological studies have provided the evidence for association between nephrolithiasis and a number of cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, metabolic syndrome. Many of the co-morbidities may not only lead to stone disease but also be triggered by it. Nephrolithiasis is a risk factor for development of hypertension and have higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and some hypertensive and diabetic patients are at greater risk for stone formation. An analysis of the association between stone disease and other simultaneously appearing disorders, as well as factors involved in their pathogenesis, may provide an insight into stone formation and improved therapies for stone recurrence and prevention. It is our hypothesis that association between stone formation and development of co-morbidities is a result of certain common pathological features. Review of the recent literature indicates that production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and development of oxidative stress (OS) may be such a common pathway. OS is a common feature of all cardiovascular diseases (CVD) including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis and myocardial infarct. There is increasing evidence that ROS are also produced during idiopathic calcium oxalate (CaOx) nephrolithiasis. Both tissue culture and animal model studies demonstrate that ROS are produced during interaction between CaOx/calcium phosphate (CaP) crystals and renal epithelial cells. Clinical studies have also provided evidence for the development of oxidative stress in the kidneys of stone forming patients. Renal disorders which lead to OS appear to be a continuum. Stress produced by one disorder may trigger the other under the right circumstances.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Diabetes, Hypertension, Metabolic syndrome, Nephrolithiasis, Oxidative stress

Introduction

Urolithiasis afflicts a large percentage of the US population [1]. It is estimated that 5–15% of the US population develops symptomatic stone disease by the age of 70 years. The worldwide prevalence of urolithiasis in men by age 70 varies from approximately 4% in England to 20% in Saudi Arabia. According to current data, the incidence of kidney stones is on the rise as indicated by a 37% increase between 1976–1980 and 1988–1994 in both genders in the United States [2]. Geographically, kidney stones are more common in places with high humidity and temperatures [3]. It has been predicted that with the expected temperature rise worldwide, there will be an increase of 1.6–2.2 million lifetime cases of kidney stone by 2050, particularly in the southeast regions of the USA [4]. In addition, urolithiasis is a chronic disease with a 60% chance of recurrence within 10 years of the first episode. Stone disease has also been linked with a number of other chronic diseases such as obesity (OB) [5], diabetes mellitus (DM) [6], hypertension (HTN) [5], metabolic syndrome (MS) [7], and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [8].

Even though our understanding of various factors and steps involved in crystallization and stone formation in the kidneys has improved [9, 10], a complete picture of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved is still unclear. It is our hypothesis that stone formation and associated co-morbidities have certain common pathological features. Therefore, an analysis of the association between stone disease and other simultaneously appearing disorders, as well as factors involved in their pathogenesis, may provide an insight into stone formation and improved therapies for stone recurrence and prevention. This article will present a brief review of recent literature on the relationship between stone formation and associated disorders.

Epidemiological studies

Hypertension

One of the earliest epidemiological studies to demonstrate an association between hypertension and nephrolithiasis was performed in Sweden (Table 1). Tibblin performed a cross-sectional retrospective study of 850, 50-year-old males [11] living in Goteberg. Based on radiological or historical data 6.5% of the patients were stone formers. When stratified by blood pressure into four groups, the prevalence of urolithiasis increased from 1.1% in the lowest blood pressure group (<145/90 mmHg untreated) to 13.3% in the subjects with the highest blood pressure (>175/115 mmHg or treated hypertension). Cirillo et al. confirmed these observations through a cross-sectional retrospective study of 3,431 European patients. There was an increased prevalence of stones in hypertensive patients (5.22%) compared to the normotensive ones (3.36%) [12].

Table 1.

Association between nephrolithiasis and hypertension

| Study type | Patient population | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective | 850 men, age 50 years | NOR (BP < 145/90), SP 1.1%; HTN (BP > 175/115), SP 13.3% | [11] |

| Cross-sectional retrospective | 3,431 European | NOR, SP 3.36%; HTN, SP 5.22% | [12] |

| Cross-sectional retrospective | 688 men, age 21–68 years | NOR, SP 13.4%; untreated HTN, 24.3%; treated HTN, 32.8%; risk of ST in HTN twice that of NOR; OR 1.79; 95% CI 1.53 to 2.09 | [13] |

| 8 years follow-up, prospective | 503 men, age 21–68 years | NOR, SP 8.5%; HTN, SP 16.7%; PTs with HTN develop ST, age- adjusted RR 1.89; 95% CI 1.12–3.18 | [15] |

| 8 years follow-up, prospective | 381 men, age 21–58 years | PTs with ST developed HTN; age-adjusted RR 1.96; 95% CI 1.25–3.07 | [16] |

| 8 years follow-up, prospective | 51,529 men, 40–75 years | Baseline, HTN and ST age-adjusted OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.30–1.32; ST PTs develop HTN, OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.12–1.41; HTN PTs develop ST, OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.82–1.12 | [17] |

| 8 years follow-up, prospective | 89,376, women, age 34–59 years | Baseline, HTN and ST age-adjusted OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.34–1.67; ST PTs develop HTN, RR 1.36; 95% CI 1.20–1.43; HTN PTs develop ST, OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.85–1.20 | [18] |

| 8 years follow-up, prospective | 132 HTN PTs; 135 NOR, men, 35–50 years | HTN PTs develop ST, OR 5.5; 95% CI 1.82–16.66 | [19] |

| Retrospective, population-based case control | 260 ST cases and matched controls | ST and HTN OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.04–1.35 | [6] |

| Retrospective cross-sectional, electronic | 23,349 cases | HTN prevalence in ST OR 1.841; 95% CI 1.651–2.053 | [23] |

| Retrospective cross-sectional | 9,541 white, 2,620 African-American, men | HTN and ST hazard ratio, 1.69; 95% CI 1.69 | [24] |

| Retrospective cross-sectional | 919 ST; 19,120 NOR | Female ST PTs 69% increase odd of HTN, 95% CI 1.33–2.17 | [25] |

ST stone, SP stone prevalence, Norm normotensive, HTN hypertensive, BP blood pressure, OR odds ratio, RR relative risk, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, PT patients, MV multivariate, UV univariate, UA uric acid, CON control

To test the hypothesis that kidney stones are more common in hypertensive men, a cross-sectional study of 688 male workers aged 21–68 years, of The Olivetti factory in Naples, Italy, was performed [13]. 118 had untreated hypertension while 61 were under treatment for hypertension. The overall prevalence of urolithiasis was 16.3% of which 13.4% were normotensive subjects, 24.3% were untreated hypertensive patients and 32.8% were treated hypertensives (p < 0.001). The relative risk of hypertensive patients having a history of urolithiasis was twice that of the normotensive subjects [odds ratio (OR) of 2.11; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17–3.81]. The age-adjusted relative risk of kidney stones in hypertensive patients remained twice that of normotensive subjects (OR 1.79; 95% CI 1.53–2.09). It was concluded that an independent clinical association existed between urolithiasis and hypertension. The results of a recent South Korean study showed hypertension as an independent predictor of stone recurrence [14].

The Olivetti Prospective Heart Study participants were then followed up after 8 years. 503 male workers aged 21–68 years, who previously did not report a history of urolithiasis were evaluated for stone disease [15]. After 8 years, 10.3% of the participants reported stone episode. The incidence of urolithiasis was higher in hypertensive patients (16.7%) than normotensives (8.5%, p = 0.011). The risk was unaffected by treatment (relative risk 2.01; 95% CI 1.13–3.59), age (RR 1.89; 95% CI 1.12–3.18), body weight (RR 1.78; CI 1.05–3.00) or height (RR 2.00; CI 1.19–3.38). It was concluded that hypertension was a significant predictor of kidney stone disease. In a separate study, 381 male normotensive participants of the Olivetti Study, 15.2% with history of stone disease, were also evaluated after 8 years [16]. Patients with history of stones were more prone to develop hypertension (age-adjusted RR 1.96; 95% CI 1.25–3.07).

Health Professional Follow-up Study (HPFS), a longitudinal study of cardiovascular diseases, cancer and other diseases among 51,529 male health professionals aged 40–75 years followed for 8 years [17] indicated that nephrolithiasis can increase the risk of the development of hypertension. At baseline, 8% reported a history of nephrolithiasis and 22.6% reported hypertension. A positive association (age-adjusted OR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.30–1.32) was present between nephrolithiasis and hypertension. The OR for incident hypertension in men with a history of nephrolithiasis was 1.29 (95% CI 1.12–1.41) compared with those without nephrolithiasis. However, hypertensive patients did not have higher incidence of stone formation (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.82–1.12) compared with the normotensive men. A similar association between stone disease and hypertension was found in middle aged women. A prospective study of the relationship in 89,376 women aged 34–59 years, part of Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) over 12 years, showed an increased risk of developing hypertension by women with a history of nephrolithiasis [18]. The age-adjusted relative risk for developing hypertension by women with history of nephrolithiasis compared to those with no nephrolithiasis history was 1.36 (95% CI 1.20–1.43). Women with hypertension were not at greater risk for stone formation compared with those without incident hypertension (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.85–1.20).

The results of these two studies [17, 18] of large cohorts of US men and women did not agree with the previous Olivetti Study with respect to hypertension being a risk for incident nephrolithiasis. However, results of another study from Parma, Italy [19], confirmed earlier observations and showed that hypertensive males were at a significant risk of forming kidney stones. A prospective 8-year follow-up study of 132 hypertensive and 135 normotensive age-matched males showed that patients with hypertension had significantly higher stones episodes than the normotensive subjects (14.3 vs. 2.9%, p = 0.001, univariate OR 5.5; 95% CI 1.82–16.66).

Another population-based case–control study performed in US also suggested a link between hypertension and nephrolithiasis. There was a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension in people with nephrolithiasis compared with the age- and sex-matched controls (OR 1.19; 95% CI 1.04–1.35) in Olmsted County, MN [6]. Recent histological studies of human kidneys have also provided support for the association between hypertension and stone disease. The presence of Randall’s plaques in cadaveric kidneys correlated only with hypertension [20]. Animal model studies have also indicated a link between stone formation and hypertension. Strains of spontaneously hypertensive rats were found to be more susceptible to developing nephrolithiasis than the normal normotensive ones [21, 22].

Results of the Portuguese National Health Survey (PNHS) in a cross-sectional study also suggested an association between nephrolithiasis and hypertension [23]. Responses of 23,349 subjects to a questionnaire approved by WHO and EUROSTAT were analyzed and showed that after adjusting for age and body mass index kidney stone formers had a higher prevalence of hypertension (OR 1.841; 95% CI 1.651–2.053) than non-stone formers.

Hypertension was also associated with incident stone disease in white and African-American participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study [24]. Information on incident kidney stone diseases and co-morbidities was obtained between 1993 and 1995 from 9,541 white and 2,620 African-American middle aged men. Hypertension (multivariate adjusted hazard ratio 1.69; 95% CI 1.69) was significantly associated with hospitalization for incident kidney stone.

Analysis of the data from the 3rd National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in United States also provided support for a relationship between kidney stone disease and hypertension. Data collected from 919 stone formers and 19,120 control subjects indicated that female stone formers had 69% increase in the odds of developing hypertension (95% CI 1.33–2.17, p < 0.001) [25]. The difference in male stone formers was not significant.

Diabetes mellitus

Even though the existence of a link between diabetes and nephrolithiasis has been known for sometime [26, 27], it has only been in the last 15 years that detailed epidemio-logical studies have been performed (Table 2). In one of the first studies, performed in Turkey, 286 diabetic patients and 111 age-matched controls were examined for the history and presence of stone disease [28]. Stone disease was more prevalent in diabetic patients (21 vs. 8%, p < 0.05) and they had higher rate of recurrence (2.1 ± 2.2 vs. 1.3 ± 0.5, p < 0.05). A cross-sectional study of three large cohorts of more than 200,000 US participants: (1) the Nurses Health Study I (older women); (2) the Nurses Health Study II (younger women) and (3) Health Professional Follow-up Study (men) [29] found that diabetic patients are more prone to stone disease. The history of diabetes was independently associated with the history of stone disease in every cohort. Multivariate relative risk of kidney stone disease in diabetic subjects compared to the nondiabetics was 1.38 (95% CI 1.06–1.79) in older women, 1.67 (95% CI 1.28–2.20) in younger women, and 1.31 (95% CI 1.11–1.54) in men. Results of a prospective study showed that the history of diabetes was independently associated with the incidence of stone disease in both the younger and older women but not in men. The multivariate relative risk of stone formation in diabetic subjects compared to nondiabetics was 1.29 (95% CI 1.05–1.58) in older women, 1.60 (95% CI 1.16–2.21) in younger women, and 0.81 (95% CI 0.59–1.09) in men. Prospectively, the history of stone disease was independently associated with the risk of diabetes in both men and women. The multivariate relative risk of development of diabetes in patients with stone disease compared to non stone formers was 1.33 (95% CI 1.18–1.50) in older women, 1.48 (95% CI 1.14–1.91) in younger women, and 1.49 (95% CI 1.29–1.72) in men.

Table 2.

Association between nephrolithiasis and diabetes mellitus

| Study type | Patient population | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective | 286 DM | SP 21% in DM; 8% in CON | [28] |

| 111 CON | ST recurrence 2.1 ± 2.2 in DM vs. 1.3 ± 0.5 in NOR | ||

| Prospective | 121,700 women, 30–55 years | ST in DM vs. non-DM RR 1.38; 95% CI 1.06–1.79 | [29] |

| ST formation in DM RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.05–1.58 | |||

| DM development in ST PTs RR 1.33; 95% CI 1.18–1.50 | |||

| Prospective | 116,671 women, 25–42 years | ST in DM vs. non-DM RR 1.67; 95% CI 1.28–2.20 | [29] |

| ST formation in DM RR 1.60; 95% CI 1.16–2.21 | |||

| DM development in ST PTs RR 1.48; 95% CI 1.14–1.91 | |||

| Prospective | 51,529 men, 40–75 years | ST in DM vs. non-DM RR 1.31; 95% CI 1.11–1.54 | [29] |

| ST formation in DM RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.59–1.09 | |||

| DM development in ST PTs RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.29–1.72 | |||

| Retrospective cross-sectional | 23,349 cases | Higher prevalence DM in ST, OR 1.475; 95% CI 1.283–1.696 | [23] |

| Retrospective, population- based case control | 3,561 ST cases | Higher prevalence DM in ST, UV OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.09–1.53 | [6] |

| MV OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03–1.46 | |||

| Within ST PTs, DM prevalence 40% in UA vs. 9% all other ST types | |||

| Retrospective cross-sectional | 9,541 white, 2,620 African- American, men | DM associated with ST MV HR 1.98; 95% CI 1.20–3.28 | [24] |

| ST prevalence in DM MV RR 1.27; 95% CI 1.08–1.49 | |||

| Retrospective cross-sectional | 272 DM | UA ST 35.7% in DM vs. 11.3% in non-DM | [31] |

| 2,192 without DM | DM and UA stone, OR 6.9; 95% CI 5.5–8.8 |

Results of the cross-sectional PNHS study also suggested an association between nephrolithiasis and diabetes mellitus [23]. Responses of 23,349 to the questionnaire were analyzed and showed that after adjusting for age and body mass index kidney stone formers had higher prevalence of diabetes (OR 1.475; 95% CI 1.283–1.696) than non-stone formers.

A population-based case–control study in which electronic data and medical records of patients at Mayo or Olmsted Medical Center, MN, were analyzed, also showed a link between nephrolithiasis and diabetes mellitus. Analyses of the electronic data of 3,561 nephrolithiasis cases showed a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes in people with nephrolithiasis compared with the age- and sex-matched controls (univariate OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.53, p = 0.004; Multivariate OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03–1.46, p = 0.02) [6]. This association remained significant even after adjustment for age, sex, hypertension and obesity. However, when medical records of a subset of 260 nephrolithiasis patients were analyzed, the number of diabetics was higher in the nephrolithiasis group compared with the controls, but did not reach significant levels in both men (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.55–3.42, p = 0.49) and women (OR 1.50, 95% CI 0.61–3.67, p = 0.37). Within the stone group, significantly more uric acid stone formers had diabetes (40 vs. 9%, p = 0.02) compared to all other stone types. A number of studies have shown that diabetes is a risk factor for uric acid nephrolithiasis because patients with type II diabetes have persistently low pH, a key factor in uric acid crystallization [30–32]. The proportion of calcium stone formers was significantly lower in diabetic patients while that of UA stone formers was three times higher in patients with diabetes [31]. Interestingly stone formers with diabetes mellitus excrete significantly more oxalate in the urine than those without diabetes [33].

Diabetes (multivariate adjusted HR 1.98; 95% CI 1.20–3.28) was significantly associated with hospitalization for incident kidney stones in white and African-American participants of the prospective ARIC study [24]. Prevalent kidney stone disease was also significantly associated with diabetes (PR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08–1.49).

Cardiovascular diseases

Studies with small samples have occasionally been performed to assess the relationship between nephrolithiasis and cardiovascular disease [34, 35]; however, until recently (Table 3), systemic epidemiological studies have been lacking. A recent population based cross-sectional study from Olmsted County, MI, USA showed that stone formers were at significantly greater risk for coronary artery disease [36] and myocardial infarction [37] than non-stone formers. In one study, 4,564 stone formers were identified and age and gender matched with 10,860 non-stone formers [37]. Cases of incident myocardial infarction (MI) were similarly identified. During a mean 9-year follow-up period, stone formers had a 38% increased risk for MI, and the risk remained significantly high even after adjustment for various co-morbidities. Stone formers were at increased risk, unadjusted (HR 1.43; 95% CI 1.11–1.84), adjusted for age and gender (HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.07–1.77), adjusted for CKD (HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.07–1.77), and adjusted for all co-morbidities including, CKD, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, gout, tobacco use (HR 1.31; 95% CI 1.02–1.69). An association between stone formation and MI was also seen in the Portuguese National Health Survey. Stone formers had a higher prevalence of MI (OR 1.338, 95% CI 1.003–1.786, p < 0.05) and stroke (OR 1.330, 95% CI 1.015–1.743, p < 0.05) than the non-stone formers [23].

Table 3.

Association between nephrolithiasis and cardiovascular diseases

| Study type | Patient population | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective, 9 years follow-up | 4,564 ST PTs; 10,860 age- and gender- matched CON | ST PTs 38% increased risk for MI, adjusted for age and gender HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.07–1.77; adjusted for all co-morbidities HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.02–1.69 | [37] |

| Retrospective cross- sectional | 23,349 cases | ST PTs higher prevalence of MI, OR 1.338, 95% CI 1.003–1.786; and stroke, OR 1.330, 95% CI: 1.015–1.743 | [23] |

| Population based, 20 years observational | 5,115 white and African-American, men and women, 18–30 years | 3.9% participants formed stones, ST formation was associated with subclinical atherosclerosis, OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.3 | [38] |

Another recent study demonstrated the relationship between stone disease and subclinical atherosclerosis and kidney stone formation. In 1985–1986, 18- to 30-year-old white and African-American adults were recruited from four clinical sites in the US, for Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Participants were reexamined after 2, 5, 7, 10, 15 and 20 years. Data were collected on a variety of factors related to cardiovascular diseases. Incident kidney stones were reported by 200 participants by the end of year 20. Stone disease was associated with greater carotid wall thickness, specifically of the internal carotid/bulb region [38] (OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.1–2.3; <p = 0.01).

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

As we discussed above there is a significant association of kidney stone formation with hypertension and diabetes, which are also the main causes of CKD. Urinary stones have been known to cause mild to severe renal insufficiency in at least a subset of patients [39–41] but detailed studies have only recently been carried out (Table 4). To determine an association between kidney stone formation and CKD a case–control study of 30- to 79-year-old 548 hospital patients and 514 age-, gender- and race-matched community controls was conducted [42] in North Carolina between 1980 and 1982. Stone formers were at higher risk of developing CKD (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.4) after adjusting for age, race, gender, income, BMI, daily cola consumption, analgesic use, and history of hypertension, gout, multiple urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis. In addition, kidney stones were also significantly associated with interstitial nephritis (OR 3.4, 95% CI 1.5–7.4) and diabetic nephropathy (OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.87–7.0).

Table 4.

Association between nephrolithiasis and chronic kidney disease

| Study type | Patient population | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population based, cross-sectional | 4,774 ST PTs, 12,975 age and gender matched CON | SP in CKD 6.9% vs. 3.1% CON. ST PTs had higher risk of CKD, OR 2.32, 95% CI 2.00–2.7 | [36] |

| Retrospective case control | 548 CKD PTs, 524 age, gender, race matched community CON, 30–79 years | SP 16.8% CKD PTs vs. 6.4% CON. ST PTs had higher risk of CKD, OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.4 after adjusting for confounding factors and co-morbidities. CKD association with diabetic nephropathy OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.87–7.0 | [42] |

| Population based, cross-sectional | 3,459 subjects, mean age 45.2 years | Overall CKD prevalence 17.5%, SP 11.3% in CKD vs. 3.72% in control, ST PTs risk of CKD 2.7X, 95% CI 1.8–4.1 | [43] |

| Effect of ST treatment on CKD | 150 ST PTs | Significant reduction in serum creatinine and GFR < 60 ml/min, OR 5.36, 95% CI 1.95–14.8 | [44] |

Another population-based cross-sectional study of 4,774 stone formers and 12,975 age- and gender-matched control subjects was conducted in Olmsted County, MN, in 1985 through 2003 [36]. CKD was more common in kidney stone formers than in control subjects (6.9 vs. 3.1%; OR 2.32, 95% CI 2.00–2.7) after adjusting for age, gender, and co-morbidities including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, gout, coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebral infarct and peripheral vascular disease.

A population-based cross-sectional Screening and Early Evaluation of Kidney Disease (SEEK) study was performed between 2007 and 2008 in Thailand. A total of 3,459 subjects, mean age 45.2 years and 54.5% females were included. Overall CKD prevalence was 17.5%. Incident stone disease was higher in CKD patients (11.3% in CKD patients vs. 3.72% in subjects without CKD) [43]. Stone formers had 2.7 times higher risk of CKD (95% CI 1.8–4.1) compared with those that never formed kidney stones.

Recently a study was performed to determine whether treatment for kidney stones can decrease the risk for CKD [44]. Historical data of stone patients with a variety of disorders including hypercalciuria, hypocitraturia, hyper-oxaluria, hyperuricosuria, and hypomagnesuria were analyzed to determine the differences in renal function between those who followed required stone treatments versus those who did not. After 5 years there was a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in the number of stones/patient in those who adhered to the metaphylaxis. Serum creatinine was significantly lower (p < 0001) and significantly fewer numbers (4.89 vs. 21.95, p < 0.001) of those who adhered to treatments had GFR <60 ml/min (OR 5.36, 95% CI 1.95–14.8).

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome (MS) is defined as a group of factors including high blood pressure, insulin resistance, high blood glucose levels, obesity, large waist size, high triglycerides and low HDL which increase the risk for coronary artery disease, stroke and type II diabetes [45]. The existence of links between diabetes and hypertension with stone formation on the one hand and with causal relationship with obesity suggests that obesity may also be causally linked to stone formation. The association between height, weight and body mass index (BMI) and the risk of kidney stone formation was studied in two large US cohorts: the NHS (n = 89,376 women) and HPFS (n = 51,529 men). Information on factors of interest was obtained through a questionnaire. There were 1,078 cases of kidney stones during 14 years in the NHS study and 956 cases during 8 years in HPFS. The prevalence of kidney stones was directly correlated with weight and BMI in both the cohorts. The age-adjusted OR was 1.38 (95% CI 1.16–1.65) for men and 1.76 for women (95% CI 1.50–2.07) with BMI > 32 versus BMI < 21 kg/m2 suggesting a higher degree of association in females than in males [46]. The relative risk (RR) for stone formation in men weighing 220 lb versus those weighing 150 lb was 1.44 (95% CI 1.11–1.86). In same weight groups, RR for older women was 1.89 (95% CI 1.52–2.36) and for younger women 1.92 (95% CI 1.59–2.31) [47]. Weight gain of over 35 lb since age 21 in men and 18 lb since age 18 in women increased the risk of kidney stone formation in both men (RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.14–1.70) and women (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.40–2.05) [47].

Another cross-sectional study of a large US cohort, NHANES, found increased prevalence of self-reported history of kidney stones in 20 years or older adults with traits of MS [48]. MS features determined were hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, waist size, low HDL, and impaired glucose tolerance. There was a significant increase in odds of self-reported stone disease with increase in number of incident MS traits, increasing two folds with four or more traits present. A recent cross-sectional study in Korea of 34,895 subjects similarly showed significant association between MS and kidney stone formation [7] (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03–1.50). A smaller Japanese study (529 men and 507 women) found significant differences in insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), blood pressure, height, weight, and waist size between stone forming and non-stone forming women [49]. History of kidney stones was significantly correlated with insulin across the tertiles.

High fructose corn syrup used in a variety of soft drinks and fast foods is currently considered a major cause of obesity, hypertension and MS [50, 51]. A prospective analyses of large US cohorts, NHS I (93,730 older women), NHS II (101,824 younger women), and HPFS (45,984 men) with documented 4,902 incident kidney stones during combined 48 years of follow-up was conducted. Adjustments were made for age, BMI, total energy intake, percentage of energy from non-fructose carbohydrates and total proteins, use of thiazide diuretics, intake of fluids, caffeine, alcohol, calcium, oxalate, potassium, and sodium. Multivariate RR of kidney stones increased significantly in the highest compared to the lowest quintile of the fructose intake, both total fructose as well as free fructose [52] in the three cohorts. Age, multivariate RR for stone formation by older women in the highest quintile of free fructose consumption, compared to lowest quintile was 1.29 (95% CI 1.08–1.53), for younger women was 1.22 (95% CI 1.02–1.47) and men was 1.28 (95% CI 1.06–1.55). Multivariate RR for stone formation by older women in the highest quintile of total fructose consumption, compared to lowest quintile was 1.37 (95% CI 1.13–1.65), for younger women was 1.35 (95% CI 1.10–1.66) and men was 1.27 (95% CI 1.04–1.54). Non-fructose containing drinks, on the other hand did not show increased risk for stone formation.

Summary, epidemiological studies

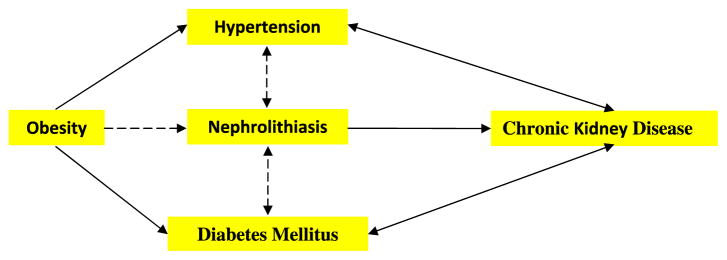

Figure 1 summarizes the links between nephrolithiasis and co-morbidities. Most epidemiological studies have shown that nephrolithiasis is a risk factor for the development of hypertension. Results of some studies have also demonstrated that hypertensive patients are at greater risk to develop nephrolithiasis. An association between stone disease and diabetes mellitus has also been shown. Kidney stone formers have a higher prevalence of diabetes while diabetic patients are prone to stone formation. Diabetics persistently produce acidic pH and are at greater risk to form uric acid stones. Kidney stone formers are also at greater risk for coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and chronic kidney disease. Not surprisingly, stone formation is prevalent in adults with metabolic syndrome and the frequency of stone formation is directly correlated with weight and BMI. Consumption of soft drinks made with corn syrup may be a risk factor for stone formation.

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic presentation of associations between nephrolithiasis and co-morbidities based upon epidemiological data. Dashed arrows indicate that links have been seen in specific stone types or relationships are weak

Physico-chemical aspects of pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis

Since crystals provide the stone mass, factors which influence crystallization are critical for stone formation. As a result, the majority of basic and clinical research has focused on examining the urinary risk factors for crystallization [53, 54], mainly those that determine supersaturation and promote or inhibit crystallization. Calcium oxalate (CaOx), calcium phosphate (CaP) and uric acid (UA) are the most common crystals in the stones. The most important determinants of urinary supersaturation and thus crystallization in urine are urinary calcium, oxalate, citrate, magnesium and pH. Crystallization is also modulated by a variety of macromolecules, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids, some acting as promoters of nucleation, growth or aggregation of crystals while others as inhibitors [55].

A number of studies have reported abnormal urinary pH [31, 33, 56] as well as urinary excretion of calcium [19, 57–62], oxalate [14, 19, 33, 59], and/or citrate [14, 59, 63] in patients with hypertension, diabetes and/or obesity. Compared to normal and non-stone forming diabetic patients, diabetic uric acid stone formers had significantly lower urinary pH, in addition, the stone formers excreted significantly lower citrate than normal and diabetic non-stone formers [56]. Net acid excretion was also increased in the diabetic patients when compared to normal age and BMI-matched subjects [64] and is considered, at least partially, responsible for lower urinary pH, predisposing the patients to UA nephrolithiasis.

In an Italian study of 132 patients with arterial hypertension and 135 normotensive controls, hypertensive males excreted significantly more calcium, magnesium, uric acid and oxalate and had significantly higher CaOx and CaP supersaturation [19]. Hypertensive females, on the other hand, excreted significantly more calcium, phosphorus, and oxalate and had significantly higher CaOx supersaturation. No significant differences were found in urinary pH or excretion of citrate. These patients and controls were followed up for an average of 7 years. Nineteen out of 132 hypertensive patients and 4 of the 135 normotensive subjects became stone formers, 12 producing CaOx stones and 4 UA stones. 16 out of 23 stone formers were overweight. Urinary supersaturation with respect to CaOx and UA correlated with the type of stone produced. Increased urinary excretion of oxalate was seen in people with higher BMI [59], obese hypertensive patients [14] as well people with diabetes [33]. Increased urinary oxalate, however, did not change urinary supersaturation for CaOx [59].

The results of the Olivetti Prospective Heart Study, which showed subjects with stone disease had significantly higher risk for developing hypertension, also demonstrated stone formers with significantly higher blood pressure and excretion of calcium [16]. A recent retrospective study of 462 stone patients to determine the relationship between hypertension and urinary composition found that in stone formers hypertension was significantly associated with urinary calcium which was 12% higher than in the normotensive stone formers [62]. There was a significant relationship between relative risk of hypertension with quintile of calcium excretion and not with citrate excretion. However, an analysis of HPFS and NHS I and II database did not show significantly increased urinary excretion of calcium by hypertensive patients. There was, however, an inverse relationship between hypertension and citraturia [63].

Crystallization is also dependent upon the macromolecular modulators present in the milieu; however, no large-scale study has been performed to determine the potential of urine from hypertensive or diabetic patients to crystallize.

Summary, physicochemical aspects in nephrolithiasis

Both hypertension and diabetes are associated with significant changes in the urinary chemistry which are known to have an effect on the crystallization of various stone forming salts. An association between diabetes and uric acid nephrolithiasis is especially strong because patients with type II diabetes produce acidic urine and are hypocitraturic. The association between idiopathic calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis and the other metabolic disorders is not as strong, not because an association does not exist but because most studies of large cohorts have included all stone types, mixing sexes, etc. diluting the effect of various risk factors. As a result, the data on urinary excretion of calcium, oxalate and citrate do show differences, but do not reach the high level of significance or demonstrate conflicting results.

Renal cellular and molecular events

Nephrolithiasis

Randall [65] suggested two pathways to the formation of kidneys stones. In his pathway 1, stones formed attached to subepithelial precalculus lesions, referred to as precalculus lesions 1, on the renal papillary surface. The precalculus lesion 1 or Randall’s Plaque Type 1 (RP1) started as poorly crystalline carbonate apatite in the papillary interstitium [66, 67]. Pathway 2 involved development of high urinary supersaturation leading to crystal deposition in lumens of the ducts of Bellini. This intratubular nidus was called precalculus lesion 2 or Randall’s Plaque Type 2 (RP2). Currently, Randall’s plaque generally refers to type 1 precalculus lesion. For the purpose of this review I will continue to use RP1 and RP2 as originally proposed. RP1 is suggested to start as laminated microspheres of poorly crystalline biological apatite in basement membrane of the loops of Henle [68, 69], or interstitium in association with vasa recta [70] or collecting ducts [20]. These microspheres are suggested to migrate to the subepithelial space, coalesce with others and materialize as RP1. Once exposed to the pelvic urine the plaque is overgrown by CaOx crystals and a stone is born [9].

Even though kidneys of most idiopathic stone formers have RP1s, and stones are formed connected to the plaques [71], most of the plaques are not attached to stones. Moreover, kidneys of non-stone formers are also plagued by plaques. It has been suggested that RP1s are formed without causing renal injury and inflammation [72, 73]. However, the presence of molecules generally involved in inflammatory pathways, such as osteopontin [74, 75], heavy chain of inter-alpha-inhibitor [76, 77], collagen [68, 78, 79], and zinc [80] in the interstitial plaques strongly suggest that inflammation may have been an early and local participant [81], which was resolved by the time the stone was discovered. Collagen is deposited during fibrosis and is an excellent nucleator of CaP [82, 83]. We have proposed that localized inflammation resulting from interstitial CaP deposition in the renal papilla promotes collagen formation which helps the propagation of CaP and growth of the RP1.

That renal cellular injury and inflammation are likely involved in the pathogenesis of idiopathic stone disease, is also suggested by analyses of stone patient’s urine. Higher than normal levels of renal enzymes, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP), angiotensin 1 converting enzyme (ACE), β-galactosidase (GAL), and N-acetyl-β-glucoseaminidase (NAG) were found in the urine of idiopathic CaOx stone formers [84]. Since elevation of these enzymes in the urine is considered an indication of renal proximal tubular injury, it was concluded that stone patients had damaged renal tubule. Results of recent studies indicate that renal epithelial injury may be a result of kidneys of idiopathic stone patients bring under oxidative stress [85, 86]. Urine from stone patients had increased NAG and significantly higher α-glutathione S-transferase (α-GST), malondialdehyde (MDA) and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS), indicating that CaOx kidney stone-associated renal injury was most likely caused by the production of reactive oxygen species. Urinary 8-hydrox-ydeoxyguanosine(8-OHdG), a marker of oxidative damage of DNA, was increased in stone patients and was positively correlated with tubular damage as assessed by urinary excretion of NAG [87]. All major markers of chronic inflammation including proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, microalbumin, myeloperoxidase, 8-OHdG, 3-nitrotyrosine and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) were detectable in patients with renal stones [88]. Yet another study reported urinary excretion of anti-inflammatory proteins calgranulin, α-defensin, and myeloperoxidase [89], by stone patients and the presence of these proteins in the inner core of the CaOx stones. It is interesting to note that consumption of DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, which reduces the risks for stroke and cardiovascular diseases, also reduces the risk for stone formation by up to 45% [90]. The authors assessed the relationship between DASH type diet and incident symptomatic kidney stones in a prospective analysis of data from HPFS and NHSI and II and found that men and women with higher DASH scores were significantly less likely to develop kidney stones than those with lower DASH scores.

Stones such as cystine, brushite, CaOx in primary hyperoxaluria and after bariatric surgery, and CaP in primary hyperparathyroidism were related to tubular crystal deposits in the ducts of Bellini [72], which were most likely formed as a result of higher supersaturation with respect to the precipitating salt. Crystal deposition was associated with renal cell injury, cell loss, inflammation and fibrosis [81, 91–96]. The inflammation was generally localized to areas around crystal deposits in the renal papillae. In brushite stone formers, however, inflammation and fibrosis reached the cortex showing widespread renal tubular atrophy and glomerular pathology [93]. These results should not come as a surprise because both animal model and tissue culture studies have consistently shown that cells, renal epithelial or others are provoked by exposure to CaOx, apatite and brushite crystals [81, 97–100] and produce pro- and anti-inflammatory molecule, such as osteopontin, MCP-1, bikunin and components of inter alpha inhibitor, α-1 microglobulin, CD-44, calgranulin, heparin sulfate, osteonectin, fibronectin and matrix-gla-protein (MGP). Many of these molecules, even though are integral to inflammation and fibrosis, are also modulators of biomineralization [55, 101].

In addition, exposure of renal epithelial cells to various crystals was associated with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [102–105]. The injured epithelium promotes crystal formation and retention within the kidneys [106]. It has also been suggested that ROS may damage the inhibitory molecules reducing their capacity to inhibit crystallization/and or their retention within the kidneys [107]. The injury could be ameliorated by anti-oxidants and free radical scavengers [98, 99, 104, 108–110]. Both mitochondria [81, 111–113] and NADPH oxidase [81, 99, 114] are involved in the production of ROS. NADPH oxidase is a major source of ROS in the kidneys [115, 116], particularly in the presence of angiotensin II [117]. Angiotensin II is implicated in causing oxidative stress by stimulating membrane bound NAD(P)H oxidase leading to increased generation of superoxide [118]. NADPH oxidase consists of six subunits, the two trans-membrane units, p22phox and gp91phox; and four cytosolic units, p47phox, p67phox, p40phox and the small GTPase rac1 or rac2. The two transmembrane units, gp91phox and p22phox associate with a flavin to make cytochrome b558. The gp91phox unit is the core catalytic component for the electron transfer activity while p22phox has regulatory and stabilizing functions. Cytosolic units translocate to the membrane and assemble with the cytochrome to activate the enzyme. Several homologues of gp91phox have been recognized. The NADPH oxidase enzyme transfers electrons to molecular O2 via the flavin-containing subunit. Gp91phox and the homologues Nox1 and Nox4 have been identified as the electron transferring subunit. Nox4 with 39% sequence identity to gp91phox, often called renal oxidase or renox, has high expression in various segments of the renal tubules and high constitutive activity [119].

Exposure of human renal epithelial-derived cell line, HK2 to Ox and CaOx crystals resulted in an increase in LDH release, production of 8-isoprotane, increased NADPH oxidase activity and production of superoxide [114]. Exposure to CaOx crystals resulted in significantly higher NADPH oxidase activity, production of superoxide and LDH release than Ox exposure alone. Exposure to Ox and CaOx crystals affected the expression of various subunits of NADPH oxidase. More consistent were increases in the expression of membrane-bound p22phox and cytosolic p47phox. Significant and strong correlations were seen between NADPH oxidase activity, the expression of p22phox and p47phox, production of superoxide and release of LDH when cells were exposed to CaOx crystals. The expressions of neither p22phox nor p47phox were significantly correlated with increased NADPH oxidase activity after the Ox exposure. Oxalate-induced injury is mediated by Rac-1 and PKC-α and PKC-δ dependent activation of NADPH-oxidase [120, 121].

We have demonstrated that inhibition of NADPH oxi-dase by diphenyleneiodium (DPI) reduced high oxalate, CaOx crystals and brushite crystal-induced injury and upregulation of OPN and MCP-1 in renal epithelial cells [99]. In addition, NADPH oxidase inhibition by apocynin treatment reduced the production of ROS, urinary excretion of kidney injury molecule and renal deposition of CaOx crystals in hyperoxaluric rats [122]. Atorvastatin, which has been shown to reduce the expression of Nox1 and p22phox subunits of NADPH oxidase [123], also inhibited crystal deposition in rats with experimentally induced hyperoxaluria [124].

Other animal model studies have provided evidence for the activation of the rennin angiotensin system (RAS) during the development of tubulointerstitial lesions of CaOx crystals [125, 126]. Reduction of angiotensin production by inhibiting the angiotensin converting enzyme as well as blocking the angiotensin receptor reduced crystal deposition and ameliorated the associated inflammatory response. We have shown that CaOx crystal deposition in rat kidneys activated the RAS and increased renin expression in the kidneys and serum [127], reduced OPN expression and CaOx crystal deposition in hyperoxaluric rats.

We examined kidneys at different times after induction of acute hyperoxaluria in male Sprague–Dawley rats, and found that crystals appeared first in the tubular lumen, then moved to inter- and intra-cellular locations, and eventually moved into the interstitium. After a few weeks, interstitial crystals disappeared, indicating the existence of a mechanism to remove the CaOx crystals [128]. Other studies showed that interstitial CaOx crystals resulting from experimental hyperoxaluria in rats caused inflammation and attracted many inflammatory cells including leukocytes, monocytes, and macrophages [105, 129–131] and multinucleated giant cells were also identified in the interstitium. These cells may play an important role in renal tissue damage through the production of proteolytic enzymes, cytokines, and chemokines. The mechanism by which inflammatory cells enter the renal interstitium is not known, but it is likely that chemotactic factors and adhesion molecules are involved.

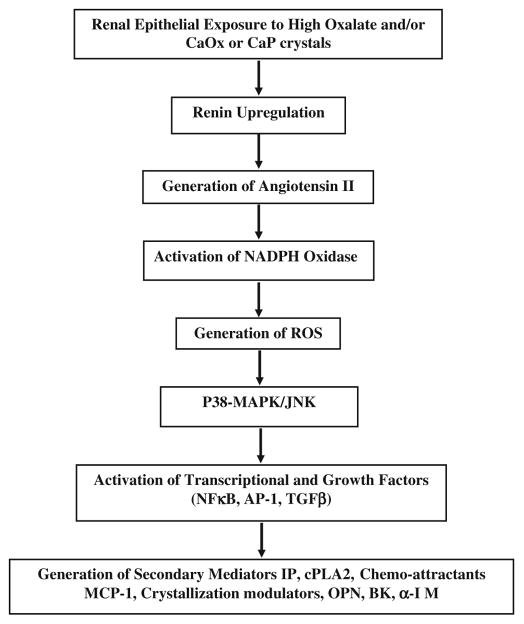

In summary (Fig. 2), experimental studies suggest that renal epithelial exposure to high oxalate and/or CaOx or CaP crystals results in rennin upregulation and generation of angiotensin II [127]. NADPH oxidase is activated [99, 120, 122, 132] leading to the production of ROS [104, 132, 133]. P-38 MAPK/JNK transduction pathway is turned on [134, 135]. A variety of transcriptional and growth factors including NFκB, AP-1, TGFβ become involved [125, 126, 136]. There is generation of secondary mediators such as isoprostanes, cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 and prostaglandins [81, 104, 137], increased production of chemoattractants such as MCP-1 [100, 138, 139], and crystallization modulators OPN [139], bikunin [140, 141], α1-microglobulin [142], inter-α-inhibitor [143], prothrombin fragment-1 [144].

Fig. 2.

Signalling pathways associated with nephrolithiasis as determined by animal model and tissue culture studies

CaOx crystals have been observed in the kidneys of patients with a variety of disorders in which production and excretion of oxalate is increased. In a biopsy from a patient with primary hyperoxaluria, crystals were seen within tubular epithelial cells as well as in the interstitium of the transplanted kidney [145]. Crystal endocytosis was associated with cell proliferation and the formation of multi-nucleated giant cells as well as with vascular and interstitial inflammation. Similar observations have been made in other cases of increased urinary excretion of Ox secondary to enteric hyperoxaluria, Crohn’s disease, and after intestinal bypass [146, 147].

Hypertension

Hypertension is generally identified by the elevation in blood pressure [148], but its association with arteriosclerosis and microscopic renal glomerular and tubular changes has long been known [149, 150]. Recent clinical as well as animal model studies have provided more evidence of renal involvement and participation of inflammatory processes in the pathogenesis of hypertension with rennin–angiotensin system (RAS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) playing significant roles. It is currently hypothesized that factors such as hyperactive sympathetic nervous system (SNS), nephron loss, hyperurecemia can induce renal vasoconstriction, ischemia, oxidative stress and injury prompting an immune response and infiltration of inflammatory cells [151–153]. A number of excellent reviews are available on this subject [151, 152, 154–158].

Cross-sectional as well as prospective studies have shown that levels of circulating C-reactive protein, the most commonly used marker of inflammation, are increased in hypertensive patients and can even predict the onset of hypertension [152, 159–161]. Circulating levels of osteopontin are also increased in essential hypertension [162]. An increase in the level of monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 MCP-1, an important modulator of inflammatory cells, has been shown in younger patients with arterial hypertension [163].

An increase in the production of ROS/RNS (reactive nitrogen species), and/or decrease in the extra and intra-cellular antioxidants has been demonstrated in both clinical and experimental hypertensions [164] and leads to oxidative stress. It may not only initiate hypertension but also be developed by the hypertensive state [118]. Major cellular ROS include superoxide anion ( ), nitric oxide radical (NO·), hydroxyl radical (OH·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which are generated by several pathways. anions are produced by NADPH oxidases, xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, hemeoxygenase and as a byproduct of mitochondrial respiratory chain. ROS/ RNS play significant roles in activating pro-inflammatory transcription factors and signaling pathways. In addition, NO and superoxide are important modulators of pressure-natriuresis [165]. Low NO levels are important in vasodilation while at higher levels NO interacts with superoxide and produces peroxynitrite which leads downstream to vasoconstriction. Hypertension is associated with reduced levels of nitrite/nitrate (Nox), in part due to enhanced nitric oxide (NO) inactivation [166]. Serum and urinary levels of Nox are significantly higher in normotensive subjects than in patients with essential hypertension, while, serum levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), an end product of lipid peroxidation, being higher in the hypertensive subjects [167]. Administration of antioxidants, or blocking of angiotensin receptors, results in improving or preventing the hypertension in a number of animal models [155, 157, 168].

NADPH oxidase is a major source of ROS in the kidneys [115, 116], particularly in the presence of Angiotensin II [117], which stimulates membrane-bound NAD(P)H oxidase leading to increased generation of superoxide [118]. NADPH oxidases are also the major source of ROS in the cardiovascular system [157] and animal models studies have provided experimental evidence of NADPH oxidase involvement in the development of hypertension. The kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) showed increased production of and upregulation of p47phox subunit [169]. Administration of SOD mimetic tempol produced a reduction of blood pressure and renal vascular resistance [170]. Significantly higher p22phox mRNA levels and NADPH oxidase driven production were found in the aorta of SHR which were ameliorated by treatment with irbesartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist [171]. The importance of p47phox is also shown by moderate hypertensive response to angiotensin II in mice lacking the p47phox [172, 173]. Inhibition by membrane permeable gp91ds-tat of p47phox assembly with gp91phox in Dahl salt sensitive (DS) rats fed a 4% salt diet, normalized ROS production and endothelium-dependent relaxation as well as expression of LOX-1 and MCP-1 [174]. Administration of apocynin, an antioxidant and an inhibitor of the p47phox assembly with gp91phox, to DS rats on high salt diet produced significant reductions in the mRNA expression of gp91phox, p47phox, p22phox, and p67phox subunits. Apocynin also reduced NADPH oxidase activity, renal cortical , monocyte/macrophage infiltration and glomerular and interstitial damage [175]. Direct administration of apocynin to the renal medulla of DS rats on 4% salt diet significantly reduced interstitial superoxide and mean arterial pressure [176]. Experimental studies involving other animal models of hypertension have similarly shown the involvement of NADPH oxidase in the development of hypertension [118, 155, 157].

Diabetes

Diabetic nephropathy, characterized by the accumulation of extracellular matrix in both the glomerulus and tubuloin-terstitium and by thickening and hyalinization of renal vasculature, is a recognized complication of diabetes [177]. Nephropathy begins with hyperglycemia. Glucose is metabolized though a variety of pathways producing molecules which in turn trigger other pathways [177–179]. Molecules such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are produced and protein kinase C (PKC) as well as RAS pathways are activated. Excessive production of ROS activates various cell signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), various chemokines such as MCP-1 and transcription factors such as nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). This leads to over expression of genes for extracellular matrix and its abnormal accumulation progressing to fibrosis. Urinary excretion of type IV collagen, α-1 microglobulin (A1MG), NAG, alanine ami-nopeptidase (AAP), 8-hydroxy-2′deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), c-reactive protein, interleukin-6 (IL-6), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), MCP-1 are significantly increased in type 2 diabetes [180]. Type IV collagen is the main component of glomerular basement membranes and increased urinary excretion is associated with mesangial expansion in type 2 diabetes [181]. Increased urinary excretion of A1MG, NAG, AAP indicate renal tubular damage. 8-OHdg is a marker of oxidative stress and damage to mitochondrial as well as nuclear DNA. C-reactive protein, IL-6, VEGF and MCP-1 are markers of inflammation.

Mitochondria are the major source of excess ROS but cell membrane-associated NaDPH oxidase also plays an important role [177, 182, 183], particularly in the presence of high glucose [177, 184] as well as the rat model of type 2 diabetes [185, 186]. Levels of Nox 4 as well as p22phox mRNA were increased in kidneys of rats with STZ-induced diabetes along with an increase in immunostaining of 8-OHdG [186]. Insulin treatment reduced them to control levels. STZ-induced diabetes also increased excretion of H2O2, lipid peroxidation products (LPO), and nitric oxide products (Nox) [185]. Kidneys showed increased expression of gp91phox and p47phox and endothelial eNOS, increased mesangial matrix, fibronectin and type I collagen. The treatment with apocynin, which inhibits assembly of the cytosolic p47phox with the membranous gp91phox, inhibited the increases in membrane fraction of p47phox, and excretion of H2O2, LPO and Nox.

Cardiovascular diseases

Both clinical and experimental investigations indicate that oxidative stress and inflammation play significant role in the development of cardiovascular diseases [187]. Reactive oxygen species causing inflammation is demonstrated by studies in which scavengers of ROS and inhibitors of various ROS-producing enzymes effectively drive down the inflammation and ameliorate cardiovascular pathology [188]. Evidence exists for proinflammatory genes, transcription factors, and pathways to be redox sensitive [189]. Data also support the concept that inflammation itself can promote the development of oxidative stress in which RAS and Nox enzymes play key roles [190].

Atherosclerosis involves expression of proinflammatory and prothrombic molecules, migration of inflammatory cells which produce chemokines, cytokines, transcription factors, and growth factors leading to proliferation of smooth muscle cells, foam cell formation and destabilization of extracellular matrix. It begins with production of ROS from various sources including Nox enzymes [187, 191, 192] and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide (eNOS). Accumulated low-density lipoproteins (LDL) are oxidized by the ROS. Oxidized LDLs are taken up by macrophages. That the NADPHs oxidase enzymes play key role in the pathogenesis of vascular diseases and stroke is evident from a variety of experimental investigations using transgenic and knockout mice models [193, 194] which showed amelioration of diseases including hypertension, atherosclerosis, restenosis after arterial injury and cerebral ischemia.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

Demonstration of constitutively expression of TNF-α by adipose tissue was one of the earliest indication of the possible association between obesity and inflammation [195]. Proinflammatory factors are increased in obesity while anti-inflammatory ones are decreased. Plasma concentrations of a number of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, interleukin 6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) are increased [45, 196, 197] while concentration of adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory cytokine is decreased. Increased levels of fatty acids stimulate production of ROS in adipocytes through the activation of NADPH oxidase and a decrease in expression of antioxidative enzymes [198]. Adipocyte exposure to ROS leads to an increase in pro-inflammatory adipocytokines [198] and decrease in anti-inflammatory adiponectin [199]. Recently, an increase in the expression of NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox has been demonstrated in vascular endothelium of overweight and obese adults compared to normal-weight controls [200] providing direct evidence of NADPH oxidase-induced endothelial oxidative stress in obese individuals. Obesity-associated oxidative stress eventually leads to systemic inflammation and endothelial cell dysfunction, central to the development of cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome [198, 201].

Summary, renal cellular and molecular events

Kidneys are involved or eventually become involved in all the cardiovascular diseases. Even though cardiovascular diseases are the result of endothelial dysfunction, other renal cells also play critical roles in the pathogenesis. Oxidative stress is a common feature in all cardiovascular disorders (CVD) including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarct. Proper endothelial performance requires NO which acts on pericytes, and is depleted during oxidative stress because of its inactivation by . Consequently, vascular relaxation is impaired, endothelial transcytosis is enhanced, pro-inflammatory molecules and signaling pathways such as MCP-1, NF-κB, TGF-β, MAPK, etc. are up-regulated. Oxidation of the NO also results in the formation of highly active ONOO− and enhancement of oxidative stress. In the kidneys NADPH oxidase is a major source of ROS and is activated by Ang II, mostly through the AT1 receptor. Both NO and are produced by the renal epithelial cells. NO is also produced by the endothelial cells. There is a tubulovascular cross talk, whereby NO produced by the epithelial cells of the medullary thick ascending limb affects the interstitial pericytes and endothelial cells.

There are two major pathways to the formation of kidney stones, both involving inner medulla. Stone formation in the idiopathic pathway begins with CaP deposition in the renal interstitium while in the other, it begins with crystallization of a variety of stone salts in the collecting ducts. There are overt signs of injury and inflammation in the second pathway where renal epithelial cells are directly exposed to crystals indicating that they are proinflammatory. Both in vitro cell culture experiments as well as animal model studies indicate that exposure to crystals, particularly CaOx and CaP, leads to the development of oxidative stress, upregulation of MAPK and production of inflammatory molecules including TGF-β, NFκB, prostaglandins, MCP-1, OPN, inter-α-inhibitor. NADPH oxidase appears to play a central role since inhibitors of the enzyme reduce the production of ROS as well as renal injury and crystal deposition. RAS pathway also appears to be critical because inhibition of angiotensin or blockage of angiotensin receptors reduced renal epithelial injury and crystal deposition in rat models of CaOx nephrolithiasis. That oxidative stress, renal epithelial injury and inflammation are also engaged in idiopathic stone formation is indicated by the urinary excretion of reactive oxygen species, products of lipid peroxidation, enzymes indicative of renal epithelial injury as well as many markers of chronic kidney disease. Interestingly, patients who consumed DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet were up to 45% less likely to develop kidney stones.

Concluding remarks

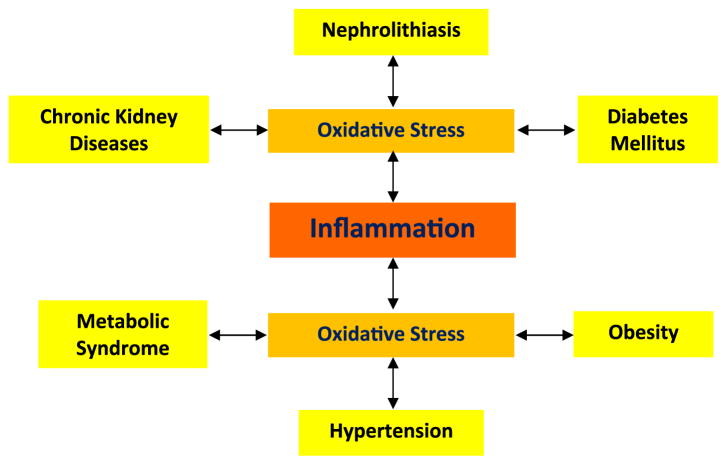

A review of published results indicates that oxidative stress and inflammation are associated with both nephrolithiasis and its co-morbidities (Fig. 3). It is also suggested that stone formation can lead to hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidneys disease and myocardial infarction. The reverse also appears to be true, in that hypertension and diabetes can also lead to stone formation. I agree with the proposal that stone formation is not just a physico-chemical event but a metabolic disorder. I propose that oxidative stress-associated disorders are a continuum. Stress introduced by one disorder can promote the other in the right circumstance. Both hypertension and diabetes not only lead to oxidative stress, renal injury and inflammation, but also bring about changes in the urinary environment which promote crystallization. In the case of diabetes, these changes specifically promote uric acid nephrolithiasis.

Fig. 3.

Nephrolithiasis and its co-morbidities lead to the development of oxidative stress which is considered a major cause of inflammation. It is our hypothesis that oxidative stress and inflammation produced by one disorder may under certain conditions lead to the development of the co-morbidity. For example, mildly high calcium or phosphate may promote deposition of calcium phosphate crystals in the renal interstitium with localized inflammation and deposition of collagen leading to the development of Randall’s plaque. Or mildly high calcium and phosphate or oxalate and low citrate or magnesium in the urine may lead to crystallization in the collecting ducts of kidney which is oxidatively stressed and injured

References

- 1.Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC. Urologic diseases in America project: urolithiasis. J Urol. 2005;173:848. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152082.14384.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976–1994. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1817. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soucie JM, Coates RJ, McClellan W, et al. Relation between geographic variability in kidney stones prevalence and risk factors for stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:487. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brikowski TH, Lotan Y, Pearle MS. Climate-related increase in the prevalence of urolithiasis in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709652105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obligado SH, Goldfarb DS. The association of nephrolithiasis with hypertension and obesity: a review. Am J Hyper-tens. 2008;21:257. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieske JC, de la Vega LS, Gettman MT, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of urinary tract stones: a population-based case–control study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:897. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong IG, Kang T, Bang JK, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and the presence of kidney stones in a screened population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:383. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saucier NA, Sinha MK, Liang KV, et al. Risk factors for CKD in persons with kidney stones: a case-control study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;55:61. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coe FL, Evan AP, Worcester EM, et al. Three pathways for human kidney stone formation. Urol Res. 2010;38:147. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johri N, Cooper B, Robertson W, et al. An update and practical guide to renal stone management. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:c159. doi: 10.1159/000317196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibblin G. A population study of 50-year-old men. An analysis of the non-participation group. Acta Med Scand. 1965;178:453. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1965.tb04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirillo M, Laurenzi M. Elevated blood pressure and positive history of kidney stones: results from a population-based study. J Hypertens Suppl. 1988;6:S485. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198812040-00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappuccio FP, Strazzullo P, Mancini M. Kidney stones and hypertension: population based study of an independent clinical association. BMJ. 1990;300:1234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6734.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YJ, Park MS, Kim WT, et al. Hypertension influences recurrent stone formation in nonobese stone formers. Urology. 2010;77:1059. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cappuccio FP, Siani A, Barba G, et al. A prospective study of hypertension and the incidence of kidney stones in men. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1017. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917070-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strazzullo P, Barba G, Vuotto P, et al. Past history of nephrolithiasis and incidence of hypertension in men: a reappraisal based on the results of the Olivetti Prospective Heart Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2232. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.11.2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madore F, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. Nephrolithiasis and risk of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:46. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madore F, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, et al. Nephrolithiasis and risk of hypertension in women. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:802. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borghi L, Meschi T, Guerra A, et al. Essential arterial hypertension and stone disease. Kidney Int. 1999;55:2397. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoller ML, Low RK, Shami GS, et al. High resolution radiography of cadaveric kidneys: unraveling the mystery of Randall’s plaque formation. J Urol. 1996;156:1263. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wexler BC, McMurtry JP. Kidney and bladder calculi in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Exp Pathol. 1981;62:369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koletsky S. Pathologic findings and laboratory data in a new strain of obese hypertensive rats. Am J Pathol. 1975;80:129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domingos F, Serra A. Nephrolithiasis is associated with an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;26:864. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akoudad S, Szklo M, McAdams MA, et al. Correlates of kidney stone disease differ by race in a multi-ethnic middle-aged population: the ARIC study. Prev Med. 2010;51:416. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillen DL, Coe FL, Worcester EM. Nephrolithiasis and increased blood pressure among females with high body mass index. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:263. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breslau NA, Pak CY. Endocrine aspects of nephrolithiasis. Spec Top Endocrinol Metab. 1982;3:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JG, Hu M, He XQ. Risk factors for the formation of urinary calcium-containing stones in diabetics. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 1989;28:649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meydan N, Barutca S, Caliskan S, et al. Urinary stone disease in diabetes mellitus. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37:64. doi: 10.1080/00365590310008730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pak CY, Sakhaee K, Moe O, et al. Biochemical profile of stone-forming patients with diabetes mellitus. Urology. 2003;61:523. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daudon M, Traxer O, Conort P, et al. Type 2 diabetes increases the risk for uric acid stones. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2026. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerer T, Weiss C, Hammes HP, et al. Evaluation of urolithiasis: a link between stone formation and diabetes mellitus? Urol Int. 2009;82:350. doi: 10.1159/000209371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisner BH, Porten SP, Bechis SK, et al. Diabetic kidney stone formers excrete more oxalate and have lower urine pH than nondiabetic stone formers. J Urol. 2010;183:2244. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamano S, Nakatsu H, Suzuki N, et al. Kidney stone disease and risk factors for coronary heart disease. Int J Urol. 2005;12:859. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ljunghall S, Hedstrand H. Renal stones and coronary heart disease. Acta Med Scand. 1976;199:481. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1976.tb06767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Kidney stones and the risk for chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:804. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05811108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rule AD, Roger VL, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Kidney stones associate with increased risk for myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1641. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010030253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiner AP, Kahn A, Eisner BH, et al. Kidney stones and subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults: the CARDIA study. J Urol. 2011;185:920. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta M, Bolton DM, Gupta PN, et al. Improved renal function following aggressive treatment of urolithiasis and concurrent mild to moderate renal insufficiency. J Urol. 1994;152:1086. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goel MC, Ahlawat R, Kumar M, et al. Chronic renal failure and nephrolithiasis in a solitary kidney: role of intervention. J Urol. 1997;157:1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillen DL, Worcester EM, Coe FL. Decreased renal function among adults with a history of nephrolithiasis: a study of NHANES III. Kidney Int. 2005;67:685. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vupputuri S, Soucie JM, McClellan W, et al. History of kidney stones as a possible risk factor for chronic kidney disease. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:222. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingsathit A, Thakkinstian A, Chaiprasert A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease in the Thai adult population: Thai SEEK study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1567. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meneses JA, Lucas FM, Assuncao FC, et al. The impact of metaphylaxis of kidney stone disease in the renal function at long term in active kidney stone formers patients. Urol Res. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00240-011-0407-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, et al. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111:1448. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, et al. Body size and risk of kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1645. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V991645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Obesity, weight gain, and the risk of kidney stones. JAMA. 2005;293:455. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West B, Luke A, Durazo-Arvizu RA, et al. Metabolic syndrome and self-reported history of kidney stones: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) 1988–1994. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:741. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ando R, Suzuki S, Nagaya T, et al. Impact of insulin resistance, insulin and adiponectin on kidney stones in the Japanese population. Int J Urol. 2011;18:131. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferder L, Ferder MD, Inserra F. The role of high-fructose corn syrup in metabolic syndrome and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:105. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jalal DI, Smits G, Johnson RJ, et al. Increased fructose associates with elevated blood pressure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1543. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Fructose consumption and the risk of kidney stones. Kidney Int. 2008;73:207. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robertson WG. A risk factor model of stone-formation. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1330. doi: 10.2741/1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kok DJ, Khan SR. Calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis, a free or fixed particle disease. Kidney Int. 1994;46:847. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan SR, Kok DJ. Modulators of urinary stone formation. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1450. doi: 10.2741/1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cameron MA, Maalouf NM, Adams-Huet B, et al. Urine composition in type 2 diabetes: predisposition to uric acid nephrolithiasis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1422. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strazzullo P, Mancini M. Hypertension, calcium metabolism, and nephrolithiasis. Am J Med Sci. 1994;307(Suppl 1):S102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Timio F, Kerry SM, Anson KM, et al. Calcium urolithiasis, blood pressure and salt intake. Blood Press. 2003;12:122. doi: 10.1080/08037050310001084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Body size and 24-hour urine composition. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:905. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mente A, Honey RJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. High urinary calcium excretion and genetic susceptibility to hypertension and kidney stone disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2567. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schleicher MM, Reis MC, Costa SS, et al. Patients with nephrolithiasis and blood hypertension have higher calciuria than those with isolated nephrolithiasis or hypertension? Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2009;61:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eisner BH, Porten SP, Bechis SK, et al. Hypertension is associated with increased urinary calcium excretion in patients with nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 2010;183:576. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor EN, Mount DB, Forman JP, et al. Association of prevalent hypertension with 24-hour urinary excretion of calcium, citrate, and other factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:780. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maalouf NM, Cameron MA, Moe OW, et al. Metabolic basis for low urine pH in type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1277. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08331109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Randall A. The origin and growth of renal calculi. Ann Surg. 1937;105:1009. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193706000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carpentier X, Bazin D, Jungers P, et al. The pathogenesis of Randall’s plaque: a papilla cartography of Ca compounds through an ex vivo investigation based on XANES spectroscopy. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2010;17:374. doi: 10.1107/S0909049510003791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khan SR, Finlayson B, Hackett R. Renal papillary changes in patient with calcium oxalate lithiasis. Urology. 1984;23:194. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(84)90021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, et al. Randall’s plaque of patients with nephrolithiasis begins in basement membranes of thin loops of Henle. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:607. doi: 10.1172/JCI17038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weller RO, Nester B, Cooke SAR. Calcification in the human renal papilla: an electron microscope study. J Pathol. 1971;107:211. doi: 10.1002/path.1711070308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stoller ML, Meng MV, Abrahams HM, et al. The primary stone event: a new hypothesis involving a vascular etiology. J Urol. 2004;171:1920. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000120291.90839.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller NL, Gillen DL, Williams JC, Jr, et al. A formal test of the hypothesis that idiopathic calcium oxalate stones grow on Randall’s plaque. BJU Int. 2009;103:966. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coe FL, Evan AP, Lingeman JE, et al. Plaque and deposits in nine human stone diseases. Urol Res. 2010;38:239. doi: 10.1007/s00240-010-0296-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evan AP, Lingeman JE, Coe FL, et al. Role of interstitial apatite plaque in the pathogenesis of the common calcium oxalate stone. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:111. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Evan AP. Physiopathology and etiology of stone formation in the kidney and the urinary tract. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;25:831. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1116-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evan AP, Coe FL, Rittling SR, et al. Apatite plaque particles in inner medulla of kidneys of calcium oxalate stone formers: osteopontin localization. Kidney Int. 2005;68:145. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]