Abstract

We report the discovery in space of methyl silane, CH3SiH3, from observations of ten rotational transitions between 80 and 350 GHz (Ju from 4 to 16) with the IRAM 30 m radio telescope. The molecule was observed in the envelope of the C-star IRC +10216. The observed profiles and our models for the expected emission of methyl silane suggest that the it is formed in the inner zones of the circumstellar envelope, 1–40 R*, with an abundance of (0.5–1) × 10−8 relative to H2. We also observed several rotational transitions of silyl cyanide (SiH3CN), confirming its presence in IRC +10216 in particular, and in space in general. Our models indicate that silyl cyanide is also formed in the inner regions of the envelope, around 20 R*, with an abundance relative to H2 of 6×10−10. The possible formation mechanisms of both species are discussed. We also searched for related chemical species but only upper limits could be obtained.

Keywords: stars: individual: IRC+10216, stars: carbon, astrochemistry, stars: AGB and post-AGB

1. Introduction

CW Leo, located ~120 pc from us, is a carbon-rich asymptotic giant branch (AGB) variable star with a period of 630–670 days and an amplitude of ~1 mag in the K band (Menten et al. 2012, and references therein). Due to its close proximity, IRC +10216, the circumstellar envelope of CW Leo, is one of the brightest infrared (IR) sources in the sky; its exceptionally rich molecular content has led several authors to study it in detail (see Cernicharo et al. 2000, and references therein). Nearly 50% of the known interstellar species have been observed in this C-rich envelope. Many of them were discovered in space for the first time there. The silicon-carbon species SinCm, which are abundant in IRC+10216, could play an important role as gas-phase precursors of SiC dust grains. The simplest members of this family, SiC (Cernicharo et al. 1989) and SiC2 (Thaddeus et al. 1984), are known to be present in this circumstellar envelope. Recently, the first species with two Si atoms (Si2C) has also been discovered there (Cernicharo et al. 2015a). Other Sibearing species found in IRC +10216, c-SiC3 and SiC4, show line profiles that indicate that they are formed in the external regions of the envelope where other radicals are formed under the action of the galactic ultraviolet field (Guélin et al. 1993).

The formation of dust grains can be simplified as a two-step process: formation of a nucleation seeds close to the AGB star, and grain growth through the addition of species containing refractory elements at high temperature and other species at lower temperature and larger distances from the star. There are, however, many unknowns in this picture of events, starting from the fundamental step of the formation of the nucleation seeds, which are essentially refractory compounds (Gail 2010). The presence of SiC grains in C-rich AGB stars was confirmed by the detection of an emission band at ~11.3 µm (Treffers & Cohen 1974), which has been found towards several C-rich evolved stars with the IRAS and ISO satellites (Yang et al. 2004). Unfortunately, the molecular precursors of SiC dust grains have not yet been identified. SiC molecules are detected in the external regions of IRC +10216, but not in the inner zones (Cernicharo et al. 1989; Patel et al. 2013; Velilla Prieto et al. 2015). As discussed by Cernicharo et al. (2015a), among the silicon-carbon species SinCm, SiC2, and Si2C could play an important role in the formation of SiC dust grains in C-rich envelopes. These species have large abundances in the inner zones of the envelope (Cernicharo et al. 2010, 2015a; Velilla Prieto et al. 2015). Other Si-bearing species studied recently in IRC +10216 with ALMA and at mid-IR wavelengths are SiS and SiO (Velilla Prieto et al. 2015; Fonfría et al. 2015), which, together with SiC2 and Si2C, account for a significant fraction of the available silicon (Agúndez et al. 2012; Velilla Prieto et al. 2015). SiCN and SiNC have been also detected in the external layers of the envelope by Guélin et al. (2000, 2004), but with much lower abundances than c-SiC3 and SiC4.

Other potential Si-bearing species involved in the growth of dust grains could be silane, SiH4, the first hydrogenated Si-bearing species detected in IRC+10216 and in space (Goldhaber & Betz 1984). However, it is unclear where in the envelope this species is formed. Keady & Ridgway (1993) suggest a formation region at ~40 stellar radii, based on the analysis of the line profiles of several ro-vibrational lines. However, Monnier et al. (2000) claims that the formation of silane occurs at ~80 R* based on interferometric observations of one of its ro-vibrational lines. The derived abundance of silane, ~2 × 10−7 relative to H2, is larger than predicted by thermochemical equilibrium by several orders of magnitude and thus it has been suggested that SiH4 could be formed by catalytic reactions at the surface of dust grains (Keady & Ridgway 1993).

The presence of SiH4 could lead to the formation of species containing the groups SiH3 and SiH2. Recently, Agúndez et al. (2014) have presented the tentative detection of three rotational lines of silyl cyanide (SiH3CN). In this letter we present the discovery of methyl silane (CH3SiH3) in IRC +10216, based on the detection of ten rotational lines with the IRAM 30 m telescope. We also report the detection of six rotational lines of SiH3CN, confirming the presence of silyl cyanide in this source and in space. Organosilicon molecules are widely used in terrestrial chemistry applications. The detection of the two organosilicon molecules CH3SiH3 and SiH3CN might help the understanding of silicon-carbon chemistries in the inner envelope of AGB stars. We have also searched for transitions of CH2SiH2 and H2CSi, but only upper limits have been obtained.

2. Observations and results

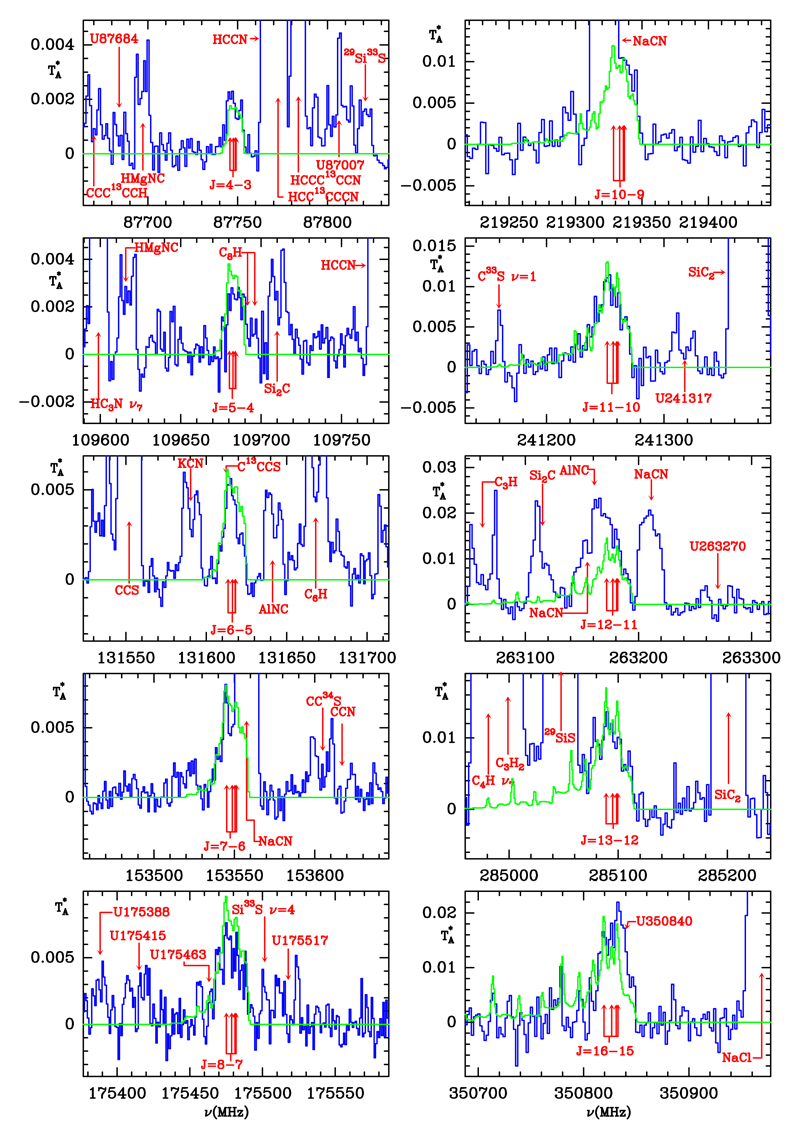

Data for this work have been acquired over the last 30 years and the observations are described in detail in Appendix A. These data have revealed several hundreds of spectral lines which cannot be assigned to any known molecular species collected in the public spectral databases CDMS (Müller et al. 2005) and JPL (Pickett 1998), and in the MADEX code (Cernicharo 2012). Most of these lines show the characteristic U-shaped emission arising from the external layers, or flat-topped emission from the middle and external layers. All lines, except the narrow features arising from the dust formation zone, have linewidths of 29 km s−1 (Cernicharo et al. 2000, 2015a). At frequencies above 250 GHz a significant number of lines are very narrow and come from the dust formation zone of IRC +10216 (see, e.g., Patel et al. 2011; Cernicharo et al. 2013, 2015a). Among the unidentified lines observed with the IRAM 30m telescope, we have been able to assign ten harmonically related lines (see Fig. 1) with profiles showing line broadening that increases with frequency (thereby eliminating the possibility of hyperfine structure as the source of line broadening). The most obvious source of this behavior is the presence of several K components for a given J → (J – 1) rotational transition, i.e., the carrier must be a symmetric top. The rotational quantum numbers are integers and the derived rotational constant is around 10 970 MHz. A quick look through the MADEX code allows these features to be assigned to methyl silane (CH3SiH3), a derivative of methane (CH4) and silane (SiH4), both of which are abundant species in IRC +10216.

Fig. 1.

Observed rotational lines of methyl silane, CH3SiH3, towards IRC+10216 in antenna temperature (in K). The spectral resolution is 1 MHz for lines below 200 GHz, and 2 MHz above that frequency. Rest frequencies are indicated for an assumed LS R velocity of the source of −26.5 km s−1. The arrows indicate the position of the K = 0, 1, 2, and 3 components of each J → (J – 1) rotational transition. In most cases the K = 0 and 1 components appear superposed. The identification of other features found in the spectra is indicated. Some of the CH3SiH3 lines are partially blended, but their red or blue parts are still clearly visible in the spectra. Green lines correspond to the emerging line profiles calculated with the model discussed in the text.

The rotational spectrum of CH3SiH3 was implemented in MADEX from a fit to the rotational lines of the ground vibrational state reported by Meerts & Ozier (1982) and Wong et al. (1983), which cover frequencies up to 285.1 GHz and transitions with Jmax = 13 and Kmax = 12. The standard deviation of the fit is 70 kHz, and thus frequencies can be predicted with an uncertainty below 0.3 MHz up to the transition J = 25 → 24 (K = 012), whose frequency is around 547 GHz. The dipole moment of the molecule is µ = 0.7346 D (Ozier & Meerts 1982). The K ladders of each J → (J – 1) rotational transition in methyl silane are more tightly spaced in frequency than those of other symmetric rotors such as CH3CN. This peculiarity, together with the fact that lines in IRC +10216 have widths of ~29 km s−1, results in severe blending of the K = 0–3 components of each J → (J – 1) rotational transition in the spectra in IRC+10216 (see Fig. 1).

The J = 4→3, 5→4, 8→7, 11→10, 12→11, 13→12, and 16→15 lines are free of blending, or only slightly blended with the features of other species, as indicated in Fig. 1. The J = 6→5 (K = 0 is at 131618.485 MHz) line is blended on its red wing with the J = 23→22 line of C13CCS at 131612.142 MHz, for which we expect an intensity of 2 mK from the observation of the adjacent J = 22→21 and J = 24→23 lines. The J = 7→6 line is blended at its blue edge with a strong line of NaCN and this same species also affects the J = 10→9 line of methyl silane at its red edge. In any case, these two lines of CH3SiH3 can be clearly distinguished in the spectra. The J = 14→13 line is fully blended with the strong J = 17→16 emission line of SiS in its ν = 1 state. No data are available for the J = 9→8 and J = 15→14 transitions.

The similarity of the line profiles of the ten observed transitions provides very strong evidence in support of the identification of this species in IRC +10216. Additional evidence comes from the comparison between the observed line profiles with those calculated with a non-LTE excitation radiative transfer model. The derived rotational temperatures for the low-J lines are ≃40–50 K, while for higher J and K lines the derived values for Trot are 100–200 K. Non-LTE calculations were performed using MADEX (Cernicharo 2012) and are based on a multi-shell large velocity gradient (LVG) method, in which we adopted the rate excitation coefficients through inelastic collisions of CH3CN (Green 1986) and the physical structure of the envelope of Agúndez et al. (2012) with the downward revision of the density profile by Cernicharo et al. (2013). The inner radius of the CH3SiH3 spatial distribution was initially taken as 40 R*, the same derived for SiH4 by Keady & Ridgway (1993). The best fit to the low–J lines corresponds to an abundance of methyl silane of 5 × 10−9 relative to H2 from 40 to 600 R*, with a vanishing abundance beyond 600 R* due to photodissociation. This model, however, does not reproduce the high-J lines correctly. A much better fit for all lines is obtained if the abundance relative to H2 is 10−8 from the photosphere to 40 R*. We note, however, that the regions inwards of 20 R* are poorly traced by the observations and, in addition, the intensities of the high-J lines could be affected by infrared pumping (methyl silane has various strong bands at mid-IR wavelengths; Randić 1962). The line profiles resulting from this latter model (X(CH3SiH3) = 10−8 for 1 < r < 40 R* and 5 × 10−9 for 40 < r < 600 R*), shown in green in Fig. 1, are in excellent agreement with the observed lines, including the high-K components of high-J transitions. The high abundance inferred for methyl silane, in layers inner to those of SiH4, indicates that the molecule is formed in a warm dense environment by thermochemical equilibrium, by chemical reactions involving abundant radicals, or by reactions at the surface of the grains (see below).

Silyl cyanide, SiH3CN, was tentatively identified in IRC +10216 by Agúndez et al. (2014) through three rotational transitions lying in the λ = 3 mm band. In Fig. A.1 we show the six rotational transitions of SiH3CN lying in spectral regions of the λ = 2 and 3 mm bands in which we have sensitive data. The J = 8→7 line is not shown because it is blended with a line of C7H. The J = 9→8 and J = 10→9 lines were reported by Agúndez et al. (2014), but since then new data have been added (see Fig. A.1) and now both lines emerge more clearly above the noise. The J = 11→10 line is not shown here because it is blended with a line of C3N in the ν5 = 1 vibrational state (see spectrum in Agúndez et al. 2014). The J = 13→12 line, not shown, is fully blended with lines of Si2C, C3N ν5 = 1, and C6H ν11 = 1. The J = 14→13 through J = 17→16 lines are not blended and are clearly detected. Higher J lines have expected intensities below the sensitivity of our data. Hence, for SiH3CN, a total of six unblended rotational lines showing the K–ladder structure are detected in IRC +10216. Consequently, our new data confirm the presence of silyl cyanide in IRC+10216. We have used a model similar to that of methyl silane and the best fit (green lines in Fig. A.1) is obtained if SiH3CN is present with an abundance relative to H2 of 6 × 10−10 between 20 and 700 R*. The calculated line profiles show a remarkable agreement with the observations in terms of both intensity and line shape.

3. Discussion

Methyl silane could be formed in the inner envelope where C2H2, C2H4, methane, and silane are formed. Formation under thermochemical equilibrium in the surroundings of the star is unlikely because the abundance of CH3SiH3 predicted with data from Allendorf & Melius (1992), is vanishingly small within the first stellar radii of the star.

Formation of methyl silane in the outer layers could be driven by reactions involving the silyl and silylene radicals, SiH3 and SiH2, and the methyl and methylene radicals, CH3 and CH2, which could be produced by photodissociation of silane and methane, respectively. The radicals SiHn and CHn (with n = 2–3) react slowly with H2, and hence these species are potential precursors of CH3SiH3. The kinetics of the reaction between SiH3 and CH4 have not been studied, but it is endothermic by 64 kJ mol−1 in the channel yielding CH3SiH3 + H. The reaction of CH3 with SiH4 has a barrier of ~3500 K to produce CH4 and SiH3 by H abstraction (Arthur & Bell 1978). This reaction is nearly thermoneutral in the formation of CH3SiH3, although it is not known whether this channel has a substantial energy barrier. Including this reaction in a chemical model of IRC +10216 (Agúndez et al. 2017) with a rate constant of 10−10 cm3 s−1 results in a CH3SiH3 abundance of a few 10−10 relative to H2, i.e., lower than that observed by more than one order of magnitude.

Methyl silane has been observed in a laboratory cold plasma of SiH4/CH4/He by Catherine et al. (1981), who suggested that the three-body association reactions SiH2 + CH4, SiH3 + CH3, and CH2 + SiH4 are the main pathways to CH3SiH3 in their experiment. These reactions, however, are spin forbidden and thus would need to have an intersystem crossing to proceed as radiative associations. In any case, even if we adopt a very optimistic rate of 10−12 cm3 s−1 for these three reactions, the chemical model predicts that methyl silane is produced with an abundance of only ~10−11 relative to H2.

Agúndez et al. (2014) have suggested that SiH3CN could be formed by a route similar to that of CH3CN, i.e., involving the precursor ion SiH3CNH+ instead of CH3CNH+. A similar way to produce methyl silane could involve the ion However, more recent ALMA observations, which put the inner radius of CH3CN in IRC +10216 at only 1–2″, probably rule out these ionic pathways (Agúndez et al. 2015). An alternative formation mechanism for methyl silane and silyl cyanide are catalytic reactions on the surface of dust grains by hydrogenation of silicon-carbon species. We could expect significant abundances of SinCm, Cn, and Si-bearing species on grain surfaces in C-rich envelopes, although their relative abundances and their potential to be hydrogenated are poorly known.

The detection of CH3SiH3 and SiH3CN suggests that other Si-bearing species could be present in the envelope. For example, the reaction of C(3Π) with SiH4 produces SiCH3 and SiCH2 without an entrance barrier (Sakai et al. 1989; Lu et al. 2008). However, the analogous reaction of Si with CH4 could have a large activation barrier (Sakai et al. 1989). SiCH2 has been observed in the laboratory and searched for towards IRC +10216 by Izuha et al. (1996). They derived an upper limit to the column density of 5.8 × 1013 cm−2. With our new data this upper limit is reduced by a factor of 3. This molecule has a very low dipole moment, ~0.3 D (Izuha et al. 1996), which makes it difficult to detect. The H2SiC isomer has a larger dipole moment (2.7 D), but it lies ~88 Kcal mol−1 above H2CSi. Another species that could be produced in reactions of SiHn and CHn is H2CSiH2. Its rotational spectrum has been measured by Bailleux et al. (1997) and it has a dipole moment of 0.66 D (Maroulis 2011). We searched for it and derive an upper limit to its column density of 4 × 1012 cm−2. SiH3 itself has some rotational lines in the submillimeter domain, but the rotational frequencies can only be roughly estimated from the infrared observations of Yamada & Hirota (1986). We searched for ro-vibrational lines of the SiH3 ν2 band in the mid-IR data (720–820 cm−1) published by Fonfría et al. (2008) and found no significant absorption features at the positions of the strongest lines where the rms noise of the data was 0.2% of the continuum level.

Note added in proof

The rotational spectrum of SiH3NC, an isomer of silyl cyanide, was recently measured in the laboratory by K. L. K. Lee, M. C. McCarthy, and C. A. Gottlieb. Details will be presented elsewhere, and an astronomical search is underway.

Appendix

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding support from Spanish MINECO under grants AYA2012-32032, AYA2016-75066-C2-1-P, and CSD2009-00038, and from the European Research Council under grant ERC-2013-SyG 610256 (NANOCOSMOS).

References

- Agúndez M, Fonfría JP, Cernicharo J, et al. A&A. 2012;543:A48. [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez M, Cernicharo J, Guélin M. A&A. 2014;570:A45. [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez M, Cernicharo J, Quintana-Lacaci G, et al. ApJ. 2015;814:143. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/814/2/143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez M, Cernicharo J, Quintana-Lacaci G, et al. A&A. 2017;601:A4. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf MD, Melius CF. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:428. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur NL, Bell TN. Rev Chem Intermed. 1978;2:37. [Google Scholar]

- Bailleux S, Bogey M, Demaison J, et al. J Chem Phys. 1997;106:10016. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine Y, Turban G, Grolleau B. Thin Solid Films. 1981;76:23. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J. Internal IRAM report. Granada: IRAM; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J. In: Stehl C, Joblin C, d’Hendecourt L, editors. EAS Pub Ser; ECLA-2011: Proc. of the European Conference on Laboratory Astrophysics; Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2012. p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Gottlieb CA, Guélin, et al. ApJ. 1989;341:L25. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Guélin M, Kahane C. A&AS. 2000;142:181. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Guélin M, Agúndez M, et al. ApJ. 2008;688:L83. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Waters LBFM, Decin L, et al. A&A. 2010;521:L8. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Daniel F, Castro-Carrizo A, et al. ApJ. 2013;778:L25. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Teyssier D, Quintana-Lacaci G, et al. ApJ. 2014;796:L21. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/796/1/L21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, McCarthy MC, Gottlieb CA, et al. ApJ. 2015a;806:L3. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/806/1/L3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo J, Marcelino N, Agúndez M, Guélin M. A&A. 2015b;575:A91. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfría JP, Agúndez M, Tercero B, et al. ApJ. 2006;646:L127. [Google Scholar]

- Fonfría JP, Cernicharo J, Richter M, et al. ApJ. 2008;673:445. [Google Scholar]

- Fonfría JP, Cernicharo J, Richter M, et al. MNRAS. 2015;453:439. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail HP. Lect Notes Phys. 2010;815:61. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber DM, Betz AL. ApJ. 1984;279:L55. [Google Scholar]

- Green S. ApJ. 1986;309:331. [Google Scholar]

- Guélin M, Lucas R, Cernicharo J. A&A. 1993;280:L19. [Google Scholar]

- Guélin S, Muller S, Cernicharo J, et al. A&A. 2000;363:L9. [Google Scholar]

- Guélin S, Muller S, Cernicharo J, et al. A&A. 2004;426:L49. [Google Scholar]

- Izuha M, Yamamoto S, Saito S. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:4923. [Google Scholar]

- Keady JJ, Ridgway ST. ApJ. 1993;406:199. [Google Scholar]

- Lu I-C, Chen W-K, Huang W-J, Lee S-H. J Chem Phys. 2008;129:164304. doi: 10.1063/1.3000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroulis G. Chem Phys Lett. 2011;505:5. [Google Scholar]

- Menten KM, Reid MJ, Kaminski T, Claussen MJ. A&A. 2012;543:A73. [Google Scholar]

- Meerts WL, Ozier I. J Mol Spectr. 1982;94:38. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier JD, Danchi WC, Hale DS, et al. ApJ. 2000;543:868. [Google Scholar]

- Müller HSP, Schlöder F, Stutzki J, Winnewisser G. J Mol Struct. 2005;742:215. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo JR, Cernicharo J, Serabyn E. IEEE Trans Antennas and Propagation. 2001;49:12. [Google Scholar]

- Patel NA, Young KH, Gottlieb CA, et al. ApJS. 2011;193:17. [Google Scholar]

- Patel NA, Gottlieb CA, Young KH. ApJS. 2013;193:17. [Google Scholar]

- Ozier I, Meerts WL. J Mol Spectr. 1982;93:164. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett HM, Poynter RL, Cohen EA, et al. J Quant Spectr Rad Transf. 1998;60:883. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana-Lacaci G, Agúndez M, Cernicharo J, et al. A&A. 2016;592:A51. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randić M. Spectrochim Acta. 1962;18:115. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Deisz J, Gordon MS. J Phys Chem. 1989;93:1888. [Google Scholar]

- Thaddeus P, Cummins SE, Linke RA. ApJ. 1984;283:L45. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers R, Cohen M. ApJ. 1974;188:545. [Google Scholar]

- Velilla Prieto L, Cernicharo J, Quintana-Lacaci G, et al. ApJ. 2015;805:L13. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/805/2/L13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Ozier I, Meerts WL. J Mol Spectr. 1983;102:89. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada C, Hirota E. Phys Rev Lett. 1988;56:923. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Chen P, He J. A&A. 2004;414:1049. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.