Abstract

The maturation of genomic technologies has enabled new discoveries in disease pathogenesis as well as new approaches to patient care. In pediatric oncology, patients may now receive individualized genomic analysis to identify molecular aberrations of relevance for diagnosis and/or treatment. In this context, several recent clinical studies have begun to explore the feasibility and utility of genomics-driven precision medicine. Here, we review the major developments in this field, discuss current limitations, and explore aspects of the clinical implementation of precision medicine, which lack consensus. Lastly, we discuss ongoing scientific efforts in this arena, which may yield future clinical applications.

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, oncology, precision medicine, targeted therapy

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Medicine and society: the precision medicine era

Precision medicine is broadly defined by the National Institutes of Health as “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person.” The Obama administration’s January 2015 announcement of the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI) takes a step forward in efforts to move precision medicine into clinical practice.1 With $215 million in planned funding for fiscal year 2016, the PMI aims to leverage next-generation sequencing capabilities, improved biospecimen analytics, and tools for the management of large data sets to generate outcome data that will facilitate movement from the research realm into clinical care. Recently, the National Cancer Moonshot Initiative, announced by President Obama during the 2016 State of the Union address and motivated by the death of Vice President Joseph Biden’s son to brain cancer, has proposed expanding governmental involvement and financial support upwards of $4 billion.2

Indeed, across multiple disciplines, the widespread utilization of high-throughput genomic technologies has enabled more detailed clinical characterization and management according to genomic knowledge. In pulmonology, patients with cystic fibrosis having the pathogenic CFTR G551D mutation preferentially respond to the drug ivacaftor.3 Cardiovascular medicine has 12 drugs with pharmacogenetic labeling from the FDA, and genotype data are helping to better predict risk for cardiovascular disease and characterize disease subtypes. Identification of patients with mutations linked to familial hypercholesterolemia, arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathies creates opportunities for prevention of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death.4 Researchers in gastroenterology are using precision medicine tools to improve biomarkers for numerous diseases and are interrogating the microbiome environment in gastrointestinal disease. In the intensive care unit, researchers have begun to define clinically feasible assays to rapidly detect sepsis through accumulation of specific metabolites in blood.5

1.2 Precision medicine and cancer

While the tools of precision medicine are being applied broadly, cancer has been at the vanguard of these efforts (Fig. 1), and near-term goals of the PMI are most accessible in oncology. The emergence of biomarker-driven targeted therapies is already a reality for some oncology patients. Thus, patients with lung cancer having epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) alterations receive EGFR-targeting therapies,6 whereas those with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations receive ALK-targeting therapies.7 Furthermore, as molecular subclasses of cancer are established, clinical study design has adapted accordingly, moving toward umbrella designs or biomarker-driven study in which patients are enrolled based on molecular features. The National Cancer Institute (NCI), which is leading the Moonshot Initiative efforts, has outlined several areas of focus for ongoing oncology PMI research and implementation: expanding clinical study, enhancing drug discovery and development, developing new cell line models, furthering the promise of immunotherapy, and improving early detection and prevention through vaccines, chemoprevention, and biomarker discovery.2 Moreover, pediatric cancer has been emphasized as a specific target area for advancing precision medicine into clinical care.

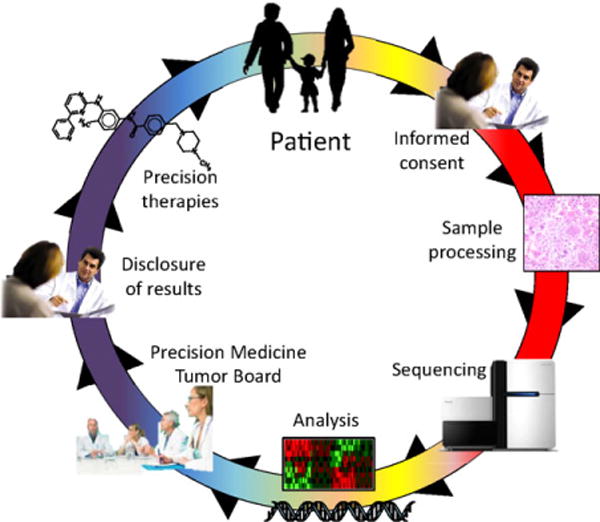

FIGURE 1.

An overview of precision medicine in oncology. Patients are enrolled for genomic profiling following informed consent. Tumor samples are then acquired, processed, molecularly profiled (typically through sequencing), and analyzed computationally. Molecular results are reviewed in a precision medicine tumor board prior to disclosure of selected, relevant results to the patient. Where available, targeted therapies may be initiated based on molecular findings

2 EARLY CLINICAL STUDIES IN PEDIATRIC ONCOLOGY

At diagnosis, patients with pediatric cancer tend to have lower rates of mutation across their genomes when compared against all adult cancers.8–10 By contrast, pediatric tumors that are treatment-refractory and recurrent, generally have higher mutation rates, more comparable to adult tumors.11–13 These data can be used to support claims that, at diagnosis, there may be less molecular complexity per individual cancer, which may enable efficacy for targeted agents by decreasing the number of altered cellular pathways, as well as the claim that there are generally few recurrently mutated targetable genes in pediatric cancers, which may limit the availability and use of some targeted agents. The relative paucity of targetable mutations in pediatrics is compounded by limited access to newer targeted therapeutic agents due to the availability of fewer pediatric clinical studies and smaller number of eligible patients for each study.

Despite these challenges, initial pilot studies of genomic medicine in pediatric oncology have been both fruitful and encouraging (Fig. 2), with several major conclusions. First, although pediatric tumors typically lack frequent targetable kinase alterations such as those in common adult cancers such as lung (EGFR) or breast cancer (HER2), pediatric tumors appear to be enriched for targetable gene fusions. Second, there has been a surprising frequency of rare mutations in actionable genes in unexpected tumor types.14 Third, the studies have reemphasized the importance of pathogenic germline mutations in pediatric cancers, even among patients lacking a notable family history of cancer. Finally, there have been notable cases of patients with a change in diagnosis or risk stratification due to genomic aberrations discovered on molecular testing.

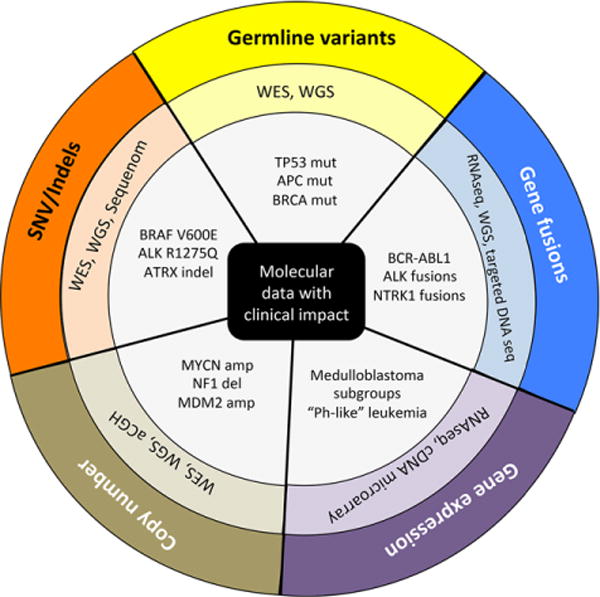

FIGURE 2.

Molecular data in precision oncology. Pediatric cancers may harbor clinically relevant germline and somatic variants, copy number aberrations, gene fusions, and gene expression patterns. Here, the outer circle indicates the type of molecular event. The middle circle indicates the various molecular assays used to profile a given molecular event. The inner circle provides several examples of clinically relevant findings enabled by molecular profiling. WES, whole exome sequencing; WGS, whole genome sequencing; cDNA, complementary DNA; Mut, mutation; Amp, amplification; Del, deletion; Indel, insertion/deletion; SNV, single-nucleotide variant; aCGH, array comparative genome hybridization

Next, we summarize the early findings from four key pediatric precision oncology studies, including two from the NHGRI and NCI-funded Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) program15–17 (Table 1). All of these studies are still ongoing and we will await the results of a larger, more definitive cohort in future. For readers less familiar with genome sequencing technologies, we have included Supplementary Appendix S1 that details the basic modalities, their pros and cons, and their compatibility with different biospecimen types.

TABLE 1.

Pilot studies of genomic medicine in pediatric oncology

| Institution | No. of patients enrolled |

No. of patients analyzed |

Tumor types included |

Types of patients enrolled |

Molecular profiling for somatic events |

Molecular profiling for transcrip- tional events |

Molecular profiling for germline events |

Profiling platform |

CLIA lab? |

Mean coverage |

Data reported |

No. of genes analyzed |

% with potentially actionable findings |

Patients treated based on actionable findings? |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASIC3 | Baylor College of Medicine | 150 | 150 (GL), 121 (tumor) | Solid | Newly diagnosed | WES | None | WES | Illumina HiSeq | Yes | WES: 272x | Somatic and germline SNVs | All | 39%, including 10% with GL finding | No |

| PEDS-MIONCOSEQ | University of Michigan | 102 | 91 | Solid, brain and liquid | Relapsed, high-risk newly diagnosed | WES, RNA-Seq | RNA-Seq | WES | Illumina HiSeq | Yes | WES: 150x | Somatic SNVs, germline SNVs, Gene expression, Gene fusions, Copy number | All | 46%, including 10% with GL finding | Yes |

| iCat | Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and others | 101 | 89 | Solid | Relapsed, high-risk newly diagnosed | Sequenom, aCGH, WES | None | Not done | Illumina HiSeq, Agilent | Yes | NR | Somatic SNVs, Gene fusions, Copy number | Sequenom 41, WES: 275, aCGH: 38 | 34% | Yes |

| INFORM | German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and others | 57 | 52 | Solid, brain and liquid | Relapsed, high-risk newly diagnosed | WES, WGS, RNA-Seq, methylation array, RNA GeneChip array | RNA-Seq, GeneChip array | WES, WGS | Illumina HiSeq, affymetrix GeneChip illumina methyl array | NA | WES: 155x; WGS: 3.4x | Somatic SNVs, germline SNVs, gene expression, gene fusions, copy number | All | 50%, including 4% with GL finding | Yes |

GL, germline; WES, whole exome sequencing; WGS, whole genome sequencing; Methyl array, methylation array; aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; SNV, single-nucleotide variant; CLIA, clinical laboratory improvements amendments; NR, not reported. Patient enrollment numbers refer to data reported in Refs. 15, 16, 19, and 20.

2.1 PEDS-MIONCOSEQ

The University of Michigan Pediatric Michigan Oncology Sequencing (PEDS-MIONCOSEQ) study15 is based on their earlier adult sequencing efforts.18 The results from the first 102 patients enrolled on PEDS-MIONCOSEQ have now been reported.15 Primary study population included pediatric and young adult patients with cancer having refractory, relapsed disease, while 20% cases included had newly diagnosed high-risk or rare disease, all of whom had undergone extensive testing by the available standard of care testing. Majority of these patients had either failed or had no proven therapeutic options available to them and were looking for novel therapies. This was one of two studies along with INFORM that included all subtypes of pediatric malignancies including hematopoietic, brain, and solid tumors. Ninety-one patients underwent genomic analyses with whole exome sequencing (WES) of tumor and germline DNA as well as RNA sequencing of tumor RNA. Clinical decision-making was made through a multidisciplinary tumor board, and patient follow-up was updated quarterly. Typical turnaround time and cost estimates were 54 days and $6,000, respectively. Overall, 42 patients (46%) had potentially actionable findings, most of which were not detected by standard diagnostic tests that did not include sequencing. The actionable findings included 9 patients with germline findings, 10 patients with an actionable gene fusion found via RNA-seq, and 2 patients who had their diagnosis changed. Twenty-three patients had an individualized care decision made based on sequencing results, which included 14 patients receiving different therapies, 9 patients with genetic counseling, and 1 patient with both. Nine of 14 patients with a change in management had a clinical response lasting more than 6 months in duration.

2.2 Basic3

Data have been reported for the first 150 children with solid and brain tumors enrolled on the Baylor College of Medicine Advancing Sequencing in Childhood Cancer Care (BASIC3) study.16 All patients underwent germline WES and those with available tumor (121/150; 81%) also underwent tumor WES. Unique among pediatric studies to date, the BASIC3 study included only newly diagnosed, untreated patients. The clinical relevance of sequencing findings was described using a standardized scale defined by the study investigators. In total 47 of 121 (39%) patients who underwent both tumor and germline sequencing were considered to have a potentially clinically relevant finding. Four of 121 (3%) patients harbored a category I somatic mutation (i.e., known pathogenic in that disease), and 29 of 121 (24%) had a category II somatic mutation (i.e., a gene of potential clinical relevance, including known targetable genes). Fifteen of 150 patients (10%) undergoing germline sequencing had a diagnostic germline finding related to their phenotype (cancer and/or other diseases), including 13 (8.6%) with pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations in known cancer susceptibility genes. No patients were treated with molecularly targeted agents based on study results.

2.3 iCat

The Individualized Cancer Therapy (iCat) study is a multi-institutional effort coordinated through Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Hospital,19 with the sequencing results of 101 extracranial patients with solid tumor reported, including 80% with recurrent or refractory disease looking for novel therapeutic options. Molecular profiling was completed on tumor tissue DNA for 89 patients. Molecular profiling was performed with a heterogeneous variety of techniques: 13 patients via OncoMap alone (a Sequenom assay for 41 genes), 27 patients by OncoMap and array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), 25 patients by OncoPanel (targeted Illumina sequencing for 275 genes and 91 introns for rearrangements) and aCGH, and 24 patients by OncoPanel alone. Clinical recommendations were based on consensus opinion with members of the multidisciplinary panel ranking potential findings on a 1 (strongest) to 5 (weakest) scale. In total, 31% of patients received iCat recommendations and 43% of patients were judged to have findings of clinical significance, including frequent focal copy number alterations (20 of 39 total clinically relevant findings), the majority of which were MYC/MYCN amplifications detectable by conventional methods. Three patients (3%) were treated with targeted therapies based on study findings, but there were no objective responses. Three patients had a change in disease diagnosis based on tumor profiling.

2.4 Inform

The Individualized Therapy for Relapsed Malignancies in Childhood (INFORM) study is a multi-institutional German effort coordinated through the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ).20 Fifty-seven patients were enrolled (50 relapsed/refractory and 7 primary patients), of whom 52 received molecular profiling. Molecular profiling was performed with WES and RNA-seq. Low-coverage whole genome sequencing (WGS) was used for copy number events; DNA methylation and gene expression microarrays were also performed. Typical turnaround time and cost estimates were 28 days and €7,000 (~$8,000), respectively. Clinical recommendations were based on a standardized, seven-step scoring algorithm to prioritize molecular targets. In total, 26 patients (50%) had a clinically relevant finding (limited to fusions, gene expression, copy number, and mutations/indels; DNA methylation was not directly used). Two (4%) patients had a germline finding that supported a cancer predisposition syndrome. Ten (19%) patients had treatments altered based on molecular findings, including two (4%) patients who had prolonged tumor response >6 months. Five (10%) patients had a change in diagnosis based on tumor profiling.

3 LESSONS FROM THE EARLY STUDIES

There are several important issues highlighted by these studies. First, clinical genomic analysis has the potential to identify potentially clinically relevant alterations in a substantial fraction of patients with pediatric cancer as demonstrated by all four studies. Second, both tumor and germline alterations identified in these studies target a diverse set of genes, including many that were not previously known to be associated with the patient’s cancer type or in pediatric cancer, emphasizing the potential yield of genome-scale testing for these patients.

Third, the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and INFORM studies demonstrate the utility of RNA-seq to identify actionable gene fusions. In the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ study, 33 of 91 patients had a driver gene fusion, 10 of which were actionable. In the INFORM study, 5 of 52 patients had an actionable gene fusion. While the iCat study attempted to identify translocations via DNA sequencing of targeted introns, this method was not particularly effective. Only one targetable translocation was found, which is surprising given that the iCat study had very high proportion of patients with sarcoma (n = 61). By contrast, the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and INFORM studies had directly targetable fusions in 5 of 44 patients with sarcoma. Fourth, there were 10 patients collectively in the iCat, PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, and INFORM studies whose diagnosis was changed by tumor profiling, which is significant given the detailed pathologic review each patient had as part of clinical evaluation, including many of the refractory patients being reviewed by more than one treating center before enrollment on these studies.

Fifth, the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, INFORM, and iCat studies demonstrated the potential utility of genomics to guide selection of targeted therapies. While the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and INFORM studies demonstrated that a small set of patients (n = 9 (10%) and 2 (4%), respectively) had a clinical response following initiation of a targeted therapy, iCat study failed to show objective responses in their patient population (n = 3). The difference is most likely due to the biological nature of malignancies and genomic lesion being targeted. PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and INFORM responders included patients with single-nucleotide variant or actionable fusion in hematological malignancies and actionable fusions in solid tumors, which historically have shown to be more responsive to single agent targeted therapy. In comparison, all three iCat patients who were treated based on study recommendations were patients with refractory solid tumor having mutations in FGF, PI3K, and ALK pathway and were treated with a single agent targeted therapy. These differential responses to single agent targeted therapy highlight the importance of optimal patient selection, role of RNA-Seq in genomic analysis of pediatric patients, and role of multiagent-targeted therapy for the hardest to treat refractory solid tumors. In contrast, the BASIC3 study highlights spectrum of genomic changes in newly diagnosed and untreated patients but did not require change in management based on the study results, as it would be ethically and logistically very challenging to integrate targeted therapy in combination with or instead of standard frontline therapy.

Lastly, these studies highlight the prevalence of pathogenic germline mutations: roughly 10% in both PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and BASIC3, and 4% in INFORM, while iCat study did not specifically address germline mutations. These data are consistent with the recent data from the Pediatric Cancer Genome Project (PCGP), a collaboration between St. Jude and Washington University with a goal to characterize pediatric cancer genomes.21 By analyzing germline sequencing data of 1,120 patients for 60 known cancer predisposition genes, the PCGP found that there was an overall 8.5% prevalence of likely pathogenic variants in the germline of patients with pediatric cancer.14 In addition, almost half of these patients with pathogenic variants in both PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and PCGP studies had no significant family history. This information is of great significance to providers caring for patients as well as for their families, as most of these parents and siblings are in relatively younger age group and would benefit from early screening.

4 MOLECULAR TARGETS IN PEDIATRIC CANCERS

While molecular targets in adult tumors have been the focus of most pharmaceutical efforts,22 pediatric patients have largely not yet benefited from these due to limited overlap with molecular events driving adult tumors, small number of patients, and safety concerns in young children. However, this is beginning to change as we start to catalogue actionable events driving pediatric tumors through precision oncology studies discussed earlier and other efforts.9,11,21,23 A selection of most common molecular events and targeted agents are detailed in Table 2.24–46

TABLE 2.

Targeted agents in pediatric cancers

| Inhibitor target | Example molecular biomarkersa | Example therapeutics | Example pediatric tumors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/mTOR | PIK3CA mutations PTEN loss TSC1/2 loss |

Everolimus Temsirolimus Rapamycin |

Sarcomas Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas |

24,25 |

| MEK | BRAF mutation BRAF tandem duplication N/KRAS mutation PTPN11 mutation NF1 loss |

Trametinib Selumetinib |

Melanoma Plexiform neurofibroma Glioblastoma Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia |

26,27 |

| BRAF | BRAF V600E/K BRAF fusions |

Vemurafenib Dabrafenib |

Melanoma Langerhans cell histiocytosis Glioma Pilocytic astrocytomas (2nd-generation inhibitors only) |

28–31 |

| ALK | ALK mutation/fusion NTRK1/2/3 fusion ROS1 fusion |

Crizotinib | Neuroblastoma Embryonal sarcomas |

32,33 |

| NTRK 1/2/3 | NTRK1/2/3 fusion | Crizotinib LOXO-101 |

Infantile fibrosarcomas Mesonephric blastoma |

34,35 |

| SMO | PTCH1 mutation SUFU mutations GLI1 amplification |

Vismodegib | Medulloblastoma | 36 |

| PARP1 | BRCA1/2 mutation EWSR1-FLI fusion ATM mutation |

Olaparib Rucaparib |

Ewing Sarcoma | 37,38 |

| CDK4/6 | CDK4/6 amplification CyclinD1 amplification | Palbociclib | Neuroblastoma Rhabdomyosarcoma ATRT |

39 |

| BET bromodomain | BRD-NUT fusions MYCN amplification MYC translocations |

JQ1, IBET726, OTX015 | NUT midline carcinomas Neuroblastoma Medulloblastoma Burkitt lymphoma |

40,41 |

| AURKA | MYCN amplification | Alisertib | Neuroblastoma | 46 |

| FGFR | FGFR1/2/3 fusion, amplification, mutation | Ponatinib Dovitinib |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | 42 |

| Multikinase inhibitors | FLT3 mutation or internal tandem duplication | Sorafenib | Acute myeloid leukemia | 43,44 |

| VEGFR, cKit, PDGFR expression | Pazopanib | Sarcomas | 45 |

Loss refers to genomic loss through either deletion or inactivating mutation.

Extending the utility of drugs initially developed for adult cancers and repurposing them for pediatric tumors sharing the same target have become a major source of new clinical studies for pediatrics, and there are several particularly notable examples. First, crizotinib, initially promoted in ALK fusion-positive lung cancers,47 has demonstrated impressive responses in patients with a variety of molecular aberrations (ALK, NTRK1/2/3, and ROS1 translocations) as well as in different tumor types, for example, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, neuroblastoma, and sarcomas.15,33 Second, for brain tumors, SMO inhibitors such as vismodegib, first developed for basal cell carcinoma,48 have demonstrated promise for medulloblastoma patients with PTCH1 mutations.36,49 Third, PARP1 inhibitors, which were initially applied to BRCA1/2 mutant breast and ovarian cancers,50 are being explored as a therapeutic strategy for patients with Ewing sarcoma having EWSR1-FLI1 fusions,37,38 although initial studies of olaparib monotherapy suggest that its activity as a single agent is limited.51,52 Lastly, a number of exciting molecular strategies for treating neuroblastoma are being investigated, such as CDK4/6 inhibitors and aurora kinase inhibitors, both of which have shown selectivity for MYCN-amplified cell lines in vitro.39

5 DRUG AVAILABILITY IN PEDIATRIC ONCOLOGY

Access to pediatric oncology drugs is unfortunately not a new problem. There have been prior issues with shortages in anticancer agents,53 which have prompted discussion by many institutions including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).54 For new discoveries, methods to incentivize pharmaceutical companies have been extensively discussed,55 and there are two existing laws that promote pediatric drug development—the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) and Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA). The BPCA offers additional patent exclusivity for on-patent drugs tested for pediatric use. The PREA enables the FDA to mandate pediatric drug studies as a last resort if other incentives do not succeed.

Recently, accelerated FDA approval of “breakthrough” drugs, such as crizotinib,56 has generated much interest and discussion.57,58 Because of such extraordinary examples of targeted agents, “seamless” or “first-in-human” studies, which are streamlined and do not employ traditional phase 1/phase 2/phase 3 paradigms, have been used on more than 40 oncologic therapies.59 These studies may provide a basis to test novel compounds in pediatric patients more quickly. However, accelerated study designs also have significant limitations when applied for pediatrics, including lack of control group and poor ability to identify toxicities, particularly in an age-dependent fashion. Ultimately, while modified study design may help, increased access to targeted therapies will also require greater collaboration with industry to move experimental therapeutics into the clinic for childhood cancers via traditional clinical studies as well.

6 LOGISTICAL CHALLENGES IN PRECISION ONCOLOGY

6.1 Cost

Genomic profiling of patients with pediatric cancer presents numerous challenges (Table 3)—the first challenge is cost. The PEDS-MIONCOSEQ study had a cost of $6,000 for WES and RNA-Seq with about half the amount spent for biochemical reagents and the other half for computational analyses, laboratory personnel, and capital depreciation.15,60 The INFORM study had a cost of €7,000 (~$8,000), which included WES, RNA-seq, low-coverage WGS, a gene expression array, and a DNA methylation array.20 However, these cost estimates are probably lower than the actual costs, as it does not include the time spent in clinical analysis, annotation, discussion, and deliberation on the results. On the other hand, traditional sequencing assays, such as BRCA gene sequencing, can cost up to $5,000 for a single gene or small panel of genes, thus making a genome-wide approach more cost-effective.61

TABLE 3.

Challenges in precision medicine

| Current Status | Considerations | Future possibilities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Costa | $6,000 |

|

|

| Turnaround timeb | 4–6 weeks |

|

Optimizing computational pipelines with targeted analyses for time reductions | |

| Lack of clinical trial availability | ~20–40% of patients with actionable targets lack access to drugs | Limited pediatric safety/efficacy data available for many experimental therapies | Multi-institutional umbrella trial protocols such as the MATCH | |

| Rational combination of therapies | Targeted agents typically initiated in the relapse setting mostly as a single agent after standard of care | Relapsed/refractory patients likely have multiple intrinsic resistance mechanisms |

|

|

| Incidental germline findings | ~8–10% of patients harbor likely pathogenic variants | Flexible default model of optional disclosure of germline findings to families |

|

The cost of reagents is going down, however the future cost of sequencing may not come down significantly due to rising bioinformatics costs deriving mainly from (i) data storage, (ii) computational pipeline generation, and (iii) data processing time.60,62,63 Indeed, data storage and processing time are increasingly facilitated through cloud computing, which is a pay-for-service paradigm.

In addition to the cost of reagents and computational resources, there are also considerable costs for a clinical genomic infrastructure, including increased personnel such as technologists, bioinformaticians, and genetic counselors. Building a genomics team to generate and analyze sequencing data therefore requires institutional support from the hospital or healthcare system. Likewise, there may be costs associated with training physicians to understand genomic data and reports through ongoing medical education.

6.2 Turnaround time

The median-reported turnaround time for PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and INFORM studies were 54 and 28 days, respectively, while other studies did not report the time.15,20 Reductions in turnaround time will likely result through streamlined computational analyses, which at present can take up to 4 weeks. This may be lessened through targeted analyses, which focus only on a limited set of genes. Ultimately, the most promising way to reduce turnaround time will likely stem from optimized computational pipelines that process data more quickly and in a parallelized fashion.62,63

6.3 Obtaining adequate tumor material

Genomic profiling requires sufficient tumor material from biopsy or resection. The tumor material also needs to be of sufficient quality (e.g., not fully necrotic tissue). Given these considerations, some children have undergone invasive procedures (e.g., biopsy) for the sole purpose of obtaining material for genomic testing. While there have been no major patient complications reported to date, there is a possibility of complications for any procedure. As sequencing methods improve, we anticipate that the need for additional biopsies will be low, due to improved ability to molecularly profile formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE)-archived tissue or by further optimization of liquid biopsy techniques.

6.4 Rational combination of targeted therapies

Even when a targeted therapy is potentially available for a particular patient, the optimal way to implement this treatment is unclear. For example, early lessons with the use of cytotoxic chemotherapy showed us the benefits of rationale combination in treatment of cancer and many in the scientific community assume the same with targeted agents. However, we need more rigorous preclinical and clinical testing to understand better, which are the optimal agents to combine for each molecular aberration and with least toxicity. The combination therapy is likely to include multiple targeted agents or targeted agents in combination with chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy, and it will most likely depend on the molecular aberration, tumor type being treated, and host immune response.

Recently, the SHIVA, a phase-II randomized study in adults with refractory solid tumors, offered a cautionary tale.64 All included patients harbored a molecular alteration within one of three pathways (hormone receptor, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and RAF/MEK). Eleven molecularly targeted agents for these pathways were available. Patients were randomized to receive a targeted agent as monotherapy or standard therapy via physician’s choice. With a median followup of 11 months, progression-free survival was not different between the two groups.

The SHIVA study has been cited by skeptics to argue that the efficacy of precision medicine may be low.65 However, the SHIVA study should be interpreted with caution due to multiple serious limitations. Perhaps most importantly, it is probably unrealistic to expect that multiply refractory metastatic cancers will respond to targeted agent monotherapy; these tumors have many different pathways dysregulated. In addition, their next-generation sequencing panel was very limited making it likely that a true driver molecular event was missed. Nonetheless, the SHIVA study does suggest that the patient selection, choice of sequencing panel, and available targeted agents will play an important role in practice of precision oncology. In addition, it is certainly possible that the populations most likely to benefit from targeted agents might be treatment-naïve tumors in which pathway addiction is likely stronger and we will need similar studies in newly diagnosed patients to test its clinical utility.

6.5 Defining pathogenic variants in pediatrics

Relatively few variants have been specifically characterized to validate their pathogenicity. This leads to a challenge when tumor profiling produces variants that have not been specifically tested experimentally. To address this, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) updated its terminology for sequence variants in 2015.66 The Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) similarly has guidelines for terminology.67 These guidelines distinguish criteria that are “pathogenic” compared to those that are “likely pathogenic,” “likely benign,” “benign,” or “uncertain significance.” Numerous efforts, including the Somatic Cancer working group of the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), are currently focused on the challenge of defining standards for interpretation of somatic changes and their clinical actionability.68

In practice, most clinical sequencing groups (BASIC3 and PEDS-MIONCOSEQ) employ centralized sequence variant databases, generally ClinVar,69 bioinformatics algorithms for prediction of pathogenic variants, such as PolyPhen-2,70 as well as expert opinion.15,16 One major challenge, both clinically and scientifically, is presented by variants of uncertain significance both for somatic and germline variants. For germline variants, there is no efficient way currently to interpret these variants, and they are generally discarded from clinical considerations unless so-called “trio” testing (mother, father, and affected child) is available, which may provide useful information for interpretation of a given variant in a pediatric patient. Recent challenges and scrutiny in cardiology, in which there are now doubts regarding the pathogenicity of germline variants in some inherited arrhythmia syndromes,4,71 highlight the unclear nature of many genomic variants.

6.6 Ethical challenges of germline findings

There have been many discussions of the ethical implications of germline genome profiling for pediatric cancers,72–75 as well as the discussion of how best to share genomic information with patients.76,77 The chance of finding incidental germline pathogenic variants, defined as a variant that was unrelated to cancer or other known patient phenotype creates an ethical challenge for these patients. Indeed, in the BASIC3 study, eight patients (5%) were found to have such a pathogenic germline variant. Similarly, a recent analysis of the 1000 Genomes Project, which sequenced 1,000 adult genomes, found a 2.3% prevalence for incidental findings.67 In response to this, some groups (e.g., PEDS-MIONCOSEQ) employ a flexible default consent model in which parents can decide whether they wish to receive results pertaining to pathogenic germline variants. In the case of PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, a majority of parents (>80%) did wish to receive these results.

Even so, there is a risk that germline discoveries in a child may enable a potential for genetic discrimination in future, particularly for germline variants not related to cancer or childhood disease generally. While genetic counselors are routinely involved with families and patients for whom a heritable cancer syndrome is suspected, it is not clear that genetic counselors should be involved in cases of incidental germline findings that do not pertain to cancer. At the same time, for a child with cancer, who also has a complex medical condition without a known underlying genetic diagnosis, it is possible that an incidental germline finding may elucidate a unifying genetic diagnosis for an underlying medical syndrome. Ultimately, it may be most prudent to leave the decision of disclosure of incidental germline findings to parents and patients, though explicit counseling on the risks of this decision must be addressed prospectively.

6.7 Universalization of practice

The implementation of precision medicine is currently uneven and lacks standardization. There are numerous aspects of healthcare infrastructure, which will ultimately impact the dissemination of precision medicine practices, including access to biomarker tests and therapies, integration with electronic healthcare records, establishment of national databases, and standardized regulatory and reimbursement processes, among others.78 While such topics are beyond the purview of this review, the National Academy of Sciences has been active in discussing mechanisms to expand and standardize precision medicine through a rational, best-practices perspective.78 Recently, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) assembled a Committee on Policy Issues in the Clinical Development and Use of Biomarkers for Molecularly Targeted Therapies.79 In their report, the Committee has advocated for increased involvement and regulation by the secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), in conjunction with the FDA, to standardize biomarker testing nationally.80

7 DEBATED TOPICS

7.1 Design and role of the precision tumor board

Although incorporated into all clinical sequencing efforts to date, the design of precision medicine tumor boards varies significantly. While all tumor boards have included clinical faculty in hematology/oncology and scientific experts in sequencing, the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and BASIC3 studies also incorporated clinical cancer geneticists upfront as core members of the tumor board.15,16 The PEDS-MIONCOSEQ study also has clinical ethicists as core members.15 Methods to interpret the data also vary. For example, in the iCat study, members of the expert panel rank each actionable alteration in each patient, using a formal system.19 By contrast, other groups (PEDS-MIONCOSEQ) discuss clinical sequencing findings, but do not have formal ranking systems.

7.2 Implementation of DNA sequencing

A version of DNA sequencing (e.g., WES or mutation panels) is an important component for any precision medicine sequencing panel. However, the precise implementation of DNA sequencing varies between groups, and which is the most optimal approach is still not clear. The BASIC3 study analyzed the entire exome for somatic and germline mutations. Other groups performed WES but focus computational analyses to a list of known cancer genes (PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, PCGP, INFORM). Lastly, some advocate for targeted sequencing of only cancer-relevant genes and not sequence the whole exome (the OncoMap and OncoPanel approaches in the iCat study).

7.3 RNAseq or no RNAseq?

The role of RNA sequencing is even less clear. The use of RNA is associated with additional challenges, including (i) technical difficulties in extracting high-quality RNA from tissue samples, (ii) analytical complexities of tumor–stroma mixtures in which the fraction of gene expression from each cell type is difficult to ascertain, and (iii) increased cost and time of the sequencing and computational analysis. Nevertheless, RNA sequencing also enables invaluable analyses. These include comprehensive gene fusion discovery, tumor expression subgroup analysis (e.g., medulloblastoma subgroups and Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia), and cell-of-origin gene expression analyses for tumors of unknown primary. Given the clinical benefit of the discovery of actionable gene fusions, especially in pediatric leukemias and sarcomas,15,20 we advocate for the inclusion of RNA sequencing in precision oncology for pediatric cases.

7.4 Standardizing the term “actionable findings or clinically relevant”

All the pediatric precision oncology studies reviewed here used the term “actionable findings” or findings of “clinical relevance” to measure the impact of the study. However, the definition of these terms was variable between studies. While all studies included “druggable” genomic alterations in these categories, only PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, iCat, and BASIC3 included alterations that are not druggable, but impacted diagnosis, prognosis, or risk stratification as actionable or clinically relevant. In addition, only PEDS-MIONCOSEQ and BASIC3 considered pathogenic germline variants as actionable findings, with only BASIC3 considering noncancer-related germline findings as actionable.

There is a definite need for standardizing the reporting on what are considered actionable or clinically relevant findings, both in somatic and germline sequencing. In addition, the somatic findings need further prioritization based on the strength of clinical evidence and germline findings needs subclassification into actionable (i) cancer-related, (ii) noncancer-related, and (iii) pharmacogenomics findings. Finally, we must recognize that as we identify new targets and develop new agents, the fraction of patients, which are considered actionable, is likely to change.

7.5 Subclone detection

Cancer is a multiclonal disease. Pediatric leukemias and sarcomas typically harbor at least two distinct genetic clones at diagnosis, with the dominant clone representing ~70–95% of tumor cells.81–83 Brain tumors, such as medulloblastoma, generally present with one overwhelming dominant clone (>95% prevalence), while posttreatment recurrence originate from distant minor subclones.13,84 The issue of multiple cancer clones raises several clinical and technical questions: How deep should sequencing be? What cut-offs should be used to detect clonal abundance? How prevalent should a clone be to impact patient care?

There are no established guidelines to answer these questions in the clinical context. Generally, WES aims for at least 100× coverage. To conceptualize what this means clinically, consider the following example: 100× coverage entails 100 reads at a given locus. If the tumor is 70% pure, then 70 of those reads represent tumor cells, and 30 reads would be stromal. Assuming one tumor clone, a homozygous mutation would therefore have 70 supporting reads and a heterozygous mutation would have 35 reads. If there are two clones, one that represents 80% of cancer cells and a second that represents 20%, then major clone would have 56 reads and the minor clone would have 14 reads. A heterozygous variant in the minor clone would therefore have seven supporting reads.

Although the importance of subclones is well established, it is not clear at what point subclones should be treated therapeutically. A targetable ALK mutation in a major clone will surely be a good candidate for an ALK inhibitor, but what about an ALK mutation that is at 1% prevalence? Indeed, new evidence of subclonal ALK mutations suggests that this question has growing importance for neuroblastoma.85 Furthermore, at 100× coverage, a heterozygous ALK mutation in 1% of neuroblastoma cells will likely be missed due to insufficient read coverage, but at 500× coverage, this same mutation may be detected. Ultimately, additional research in this area is needed to help guide precision medicine efforts.

7.6 Patient enrollment

Patient selection is critical for precision medicine. Patients for whom cure rates are extremely high (e.g., standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia) may benefit less from tumor sequencing. Initial efforts emphasized genomic profiling of multiply relapsed and refractory patients. However, highly refractory tumors are unlikely to exhibit single pathway addiction due to the development of multiple resistance pathways during the course of therapy. Thus, many advocate for genomic profiling early in disease course, ideally at diagnosis for cases with higher probability of relapse, and to incorporate targeted therapy (if appropriate) into the treatment regimen earlier as well, as tumors that are more naïve may respond better to pathway inhibition. Many groups are also repeating genomic analysis at the time of relapse to assess for clonal evolution and newly acquired molecular features.

8 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

8.1 NCI Pediatric MATCH study

The NCI Pediatric Molecular Analysis for Therapeutic Choice (MATCH) study, a collaborative effort between the Children’s Oncology Group and NCI, is an ongoing effort that aims to build on adult oncology study86,87 to develop a protocol for targeted therapy using an umbrella design. NCI Pediatric MATCH will use standardized DNA- and RNA-based biomarker profiling of patient tumor and blood samples to assign patients to phase-II studies of targeted therapies if one of a predefined set of actionable mutations is detected. A number of drug-biomarker pairs have been prioritized for inclusion on the study based on the factors including (i) prevalence of the genomic alteration in pediatric cancer, (ii) ability to detect the target using the study platform, (iii) evidence linking the target to activity of the agent, (iv) clinical and preclinical data for specific agents, and (v) other ongoing or planned biomarker-defined clinical studies. The study is anticipated to open with five to eight arms (molecularly targeted agents). Given the size of the NCI Pediatric MATCH study, the methods employed for genomic profiling are likely to inform precision oncology approaches for pediatric patients moving forward.

8.2 Liquid tumor biopsies

Currently, the clinical standard is to monitor genomic alterations via direct tumor biopsy or resection. However, there is abundant evidence that circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and/or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) present in blood offer an opportunity to evaluate tumor biology non-invasively, even for brain tumors.88–93 In pediatric cancers, most evidence for CTCs and cfDNA has been in neuroblastoma and other solid tumors.94–96

In addition to being noninvasive, CTCs and cfDNA enable frequent monitoring of tumor course during and after treatment. Technically, methods to isolate this genomic material are challenging, costly, and labor-intensive. However, they are increasingly clinically feasible.89 CTCs also entail single-cell sequencing, which if done for populations of tumor cells, may enable more direct quantification of tumor heterogeneity and clonal abundance. In future, methodological advances and decreasing sequencing costs may help advance clinical prospects for single-cell sequencing.

8.3 Tumor profiling at multiple time points

In addition to tumor profiling at diagnosis and relapse, some groups now advocate for molecular analyses at more regular intervals during treatment. Molecular assays for minimal residual disease (MRD) in leukemias, for example, now include both flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. Sequencing may ultimately fulfill this role too, and multiple groups are exploring the clinical feasibility and utility of sequencing for MRD.97–100

8.4 Expanding the landscape of sequencing

As knowledge of tumor biology advances and sequencing becomes more easily implemented, the range of clinically relevant genomic tools may expand (Fig. 3).101 DNA methylation sequencing, or other forms of epigenomics, may be appropriate for some tumors such as brain tumors. Here, recent elucidation of a CpG island methylator phenotype has advanced our understanding of tumor subgroups and may be relevant to understanding driver genomic alterations102,103 and patient disease course.104 Methylation sequencing may ultimately be possible from noninvasive sources as well.105

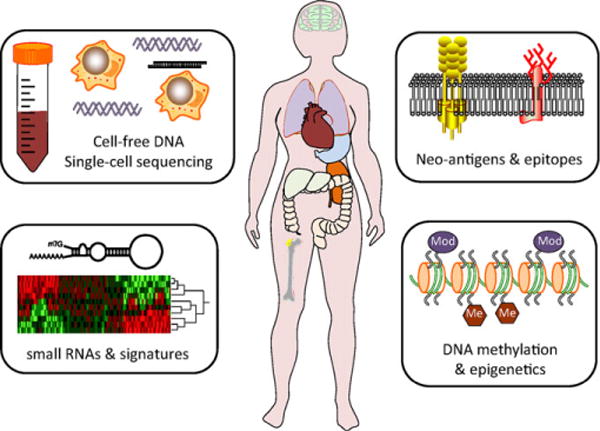

FIGURE 3.

Future directions in precision medicine. In upcoming years, further research may define clinical roles for multiple new areas of precision medicine. Four potential new areas include epigenomic profiling, small RNA profiling, neoantigens, and epitope profiling, and single cell sequencing and cell-free DNA (cfDNA)

Moreover, as immunotherapy and cancer immunology advance, clinical sequencing may incorporate efforts to decode tumor neoantigens and T-cell repertoires in patients. Such initiatives are already being explored in patient samples and in actively treated patients.106–108 Further efforts in patient care may expand into small RNA and microRNA sequencing.109

8.5 Rationally understanding drug metabolism

One of the biggest black boxes in medicine is how different patients metabolize medications, which can significantly impact effect dose, therapeutic levels, and side effects. This is particularly critical for cytotoxic chemotherapy (e.g., 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, and cisplatin) as well as specific toxicities associated with individual therapies (e.g., cardiomyopathy with anthracyclines and hearing loss with vincristine). The application of genomic technologies, especially metabolomics, may provide key insights as well as clinical tools to understand and rationally predict drug behavior and toxicity profiles in patients in vivo.110 Ultimately, patients may have individually tailored dosing regimens based on their specific physiology. Such prospects have the possibility of dramatically changing the way medicine is practiced.

9 CONCLUDING REMARKS

Precision medicine has rapidly become one of the most pursued research and clinical objectives over the past decade. The political landscape, including the PMI and Moonshot for cancer, indicates that funding and support for PMIs will continue to be robust. Early clinical evidence for pediatric precision medicine through the PEDS-MIONCOSEQ, BASIC3, INFORM, and iCat studies has been encouraging, with meaningful results for some patients. Yet, precision medicine still faces numerous challenges in its implementation, standardization, and feasibility across multiple institutions. In the near future, large-scale prospective consortia studies, such as the NCI Pediatric MATCH study, will further refine the implementation of precision medicine in pediatric oncology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karen Giles for administrative support and Kevin Frank for helping with formatting the manuscript, figures, and tables. The BASIC3 and PEDS-MIONCOSEQ studies are Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research program projects supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Cancer Institute (U01HG006485 and UM1HG006508, respectively). RJM is supported by the Hyundai Hope on Wheels Scholar Award. AMC is supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Award, Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute. AMC is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and a Taubman Scholar of the University of Michigan.

Grant sponsor: National Human Genome Research Institute; Grant number: U01HG006485; Grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute; Grant number: UM1HG006508.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

References

- 1.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy M. US president endorses “moonshot” effort to cure cancer. Bmj. 2016;352:i213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(18):1663–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyner MJ. Precision medicine, cardiovascular disease and hunting elephants. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antcliffe D, Gordon AC. Metabonomics and intensive care. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499(7457):214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pugh TJ, Morozova O, Attiyeh EF, et al. The genetic landscape of high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45(3):279–284. doi: 10.1038/ng.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, et al. Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations. Nature. 2012;488(7409):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eleveld TF, Oldridge DA, Bernard V, et al. Relapsed neuroblastomas show frequent RAS-MAPK pathway mutations. Nat Genet. 2015;47(8):864–871. doi: 10.1038/ng.3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schramm A, Koster J, Assenov Y, et al. Mutational dynamics between primary and relapse neuroblastomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47(8):872–877. doi: 10.1038/ng.3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrissy AS, Garzia L, Shih DJ, et al. Divergent clonal selection dominates medulloblastoma at recurrence. Nature. 2016;529(7586):351–357. doi: 10.1038/nature16478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(24):2336–2346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mody RJ, Wu YM, Lonigro RJ, et al. Integrative clinical sequencing in the management of refractory or relapsed cancer in youth. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(9):913–925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons DW, Roy A, Yang Y, et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):616–624. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green RC, Goddard KA, Jarvik GP, et al. Clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium: accelerating evidence-based practice of genomic medicine. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(6):1051–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roychowdhury S, Iyer MK, Robinson DR, et al. Personalized oncology through integrative high-throughput sequencing: a pilot study. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(111):111ra121. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris MH, DuBois SG, Glade Bender JL, et al. Multicenter feasibility study of tumor molecular profiling to inform therapeutic decisions in advanced pediatric solid tumors: the Individualized Cancer Therapy (iCat) Study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):608–615. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worst BC, van Tilburg CM, Balasubramanian GP, et al. Next-generation personalised medicine for high-risk paediatric cancer patients—the INFORM pilot study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downing JR, Wilson RK, Zhang J, et al. The Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):619–622. doi: 10.1038/ng.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roychowdhury S, Chinnaiyan AM. Translating genomics for precision cancer medicine. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2014;15:395–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090413-025552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janeway KA, Place AE, Kieran MW, et al. Future of clinical genomics in pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15):1893–1903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.8470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry JA, Kiezun A, Tonzi P, et al. Complementary genomic approaches highlight the PI3K/mTOR pathway as a common vulnerability in osteosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(51):E5564–E5573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419260111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Adjei AA. The clinical development of MEK inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(7):385–400. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang TY, Dvorak CC, Loh ML. Bedside to bench in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: insights into leukemogenesis from a rare pediatric leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(16):2487–2497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-300319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu C, Zhang J, Nagahawatte P, et al. The genomic landscape of childhood and adolescent melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(3):816–823. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):726–736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bautista F, Paci A, Minard-Colin V, et al. Vemurafenib in pediatric patients with BRAFV600E mutated high-grade gliomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):1101–1103. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sievert AJ, Lang SS, Boucher KL, et al. Paradoxical activation and RAF inhibitor resistance of BRAF protein kinase fusions characterizing pediatric astrocytomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(15):5957–5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219232110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosse YP, Laudenslager M, Longo L, et al. Identification of ALK as a major familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Nature. 2008;455(7215):930–935. doi: 10.1038/nature07261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosse YP, Lim MS, Voss SD, et al. Safety and activity of crizotinib for paediatric patients with refractory solid tumours or anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a Children’s Oncology Group phase 1 consortium study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):472–480. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT, et al. Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1469–1472. doi: 10.1038/nm.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doebele RC, Davis LE, Vaishnavi A, et al. An oncogenic NTRK fusion in a patient with soft-tissue sarcoma with response to the tropomyosin-related kinase inhibitor LOXO-101. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(10):1049–1057. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gajjar A, Stewart CF, Ellison DW, et al. Phase I study of vismodegib in children with recurrent or refractory medulloblastoma: a pediatric brain tumor consortium study. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(22):6305–6312. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483(7391):570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner JC, Feng FY, Han S, et al. PARP-1 inhibition as a targeted strategy to treat Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(7):1608–1613. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rader J, Russell MR, Hart LS, et al. Dual CDK4/CDK6 inhibition induces cell-cycle arrest and senescence in neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(22):6173–6182. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puissant A, Frumm SM, Alexe G, et al. Targeting MYCN in neuroblastoma by BET bromodomain inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(3):308–323. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bandopadhayay P, Bergthold G, Nguyen B, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition of MYC-amplified medulloblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(4):912–925. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li SQ, Cheuk AT, Shern JF, et al. Targeting wild-type and mutationally activated FGFR4 in rhabdomyosarcoma with the inhibitor ponatinib (AP24534) PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watt TC, Cooper T. Sorafenib as treatment for relapsed or refractory pediatric acute myelogenous leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(4):756–757. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarlock K, Chang B, Cooper T, et al. Sorafenib treatment following hematopoietic stem cell transplant in pediatric FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(6):1048–1054. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glade Bender JL, Lee A, Reid JM, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of pazopanib in children with soft tissue sarcoma and other refractory solid tumors: a children’s oncology group phase I consortium report. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(24):3034–3043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DuBois SG, Marachelian A, Fox E, et al. Phase I study of the aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib in combination with irinotecan and temozolomide for patients with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: a NANT (New Approaches to Neuroblastoma Therapy) Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1368–1375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Von Hoff DD, LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1164–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1173–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith MA, Hampton OA, Reynolds CP, et al. Initial testing (stage 1) of the PARP inhibitor BMN 673 by the pediatric preclinical testing program: PALB2 mutation predicts exceptional in vivo response to BMN 673. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(1):91–98. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choy E, Butrynski JE, Harmon DC, et al. Phase II study of olaparib in patients with refractory Ewing sarcoma following failure of standard chemotherapy. BMC cancer. 2014;14:813. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Decamp M, Joffe S, Fernandez CV, et al. Chemotherapy drug shortages in pediatric oncology: a consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e716–e724. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy D, Reaman G, Jensen CV. Pediatric oncology drug shortages: a multifaceted problem. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e728–e729. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Institute of Medicine. Addressing the Barriers to Pediatric Drug Development: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malik SM, Maher VE, Bijwaard KE, et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval: crizotinib for treatment of advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer that is anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(8):2029–2034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson JR, Ning YM, Farrell A, et al. Accelerated approval of oncology products: the food and drug administration experience. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(8):636–644. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, et al. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987–2014: cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4633. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prowell TM, Theoret MR, Pazdur R. Seamless oncology-drug development. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(21):2001–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1603747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muir P, Li S, Lou S, et al. The real cost of sequencing: scaling computation to keep pace with data generation. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0917-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porter PL, Malone KE, Heagerty PJ, et al. Expression of cell-cycle regulators p27Kip1 and cyclin E, alone and in combination, correlate with survival in young breast cancer patients. Nat Med. 1997;3(2):222–225. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schatz MC, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Cloud computing and the DNA data race. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):691–693. doi: 10.1038/nbt0710-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein LD. The case for cloud computing in genome informatics. Genome Biol. 2010;11(5):207. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le Tourneau C, Delord JP, Goncalves A, et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prasad V, Fojo T, Brada M. Precision oncology: origins, optimism, and potential. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(2):e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dorschner MO, Amendola LM, Turner EH, et al. Actionable, pathogenic incidental findings in 1,000 participants’ exomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(4):631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rehm HL, Berg JS, Brooks LD, et al. ClinGen–the clinical genome resource. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(23):2235–2242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1406261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Driest SL, Wells QS, Stallings S, et al. Association of arrhythmia-related genetic variants with phenotypes documented in electronic medical records. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(1):47–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scollon S, Bergstrom K, Kerstein RA, et al. Obtaining informed consent for clinical tumor and germline exome sequencing of newly diagnosed childhood cancer patients. Genome Med. 2014;6(9):69. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Everett JN, Mody RJ, Stoffel EM, et al. Incorporating genetic counseling into clinical care for children and adolescents with cancer. Future Oncol. 2016;12(7):883–886. doi: 10.2217/fon-2015-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCullough LB, Slashinski MJ, McGuire AL, et al. Is whole-exome sequencing an ethically disruptive technology? Perspectives of pediatric oncologists and parents of pediatric patients with solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(3):511–515. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parsons DW, Roy A, Plon SE, et al. Clinical tumor sequencing: an incidental casualty of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics recommendations for reporting of incidental findings. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2203–2205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roberts JS, Shalowitz DI, Christensen KD, et al. Returning individual research results: development of a cancer genetics education and risk communication protocol. J Empirical Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5(3):17–30. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henderson GE, Wolf SM, Kuczynski KJ, et al. The challenge of informed consent and return of results in translational genomics: empirical analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics. 2014;42(3):344–355. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.National Academies of Sciences. Biomarker Tests for Molecularly Targeted Therapies: Key to Unlocking Precision Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyman GH, Moses HL. Biomarker tests for molecularly targeted therapies—the key to unlocking precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(1):4–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1604033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Graig LA, Phillips JK, Moses HL, editors. Biomarker Tests for Molecularly Targeted Therapies: Key to Unlocking Precision Medicine. Washington, DC: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ma X, Edmonson M, Yergeau D, et al. Rise and fall of subclones from diagnosis to relapse in pediatric B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6604. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farrar JE, Schuback HL, Ries RE, et al. Genomic profiling of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia reveals a changing mutational landscape from disease diagnosis to relapse. Cancer Res. 2016;76(8):2197–2205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen X, Stewart E, Shelat AA, et al. Targeting oxidative stress in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(6):710–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu X, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, et al. Clonal selection drives genetic divergence of metastatic medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;482(7386):529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bellini A, Bernard V, Leroy Q, et al. Deep sequencing reveals occurrence of subclonal ALK mutations in neuroblastoma at diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(21):4913–4921. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McNeil C. NCI-MATCH launch highlights new trial design in precision-medicine era. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(7) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abrams J, Conley B, Mooney M, et al. National Cancer Institute’s Precision Medicine Initiatives for the New National Clinical Trials Network. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book/ASCO American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting. 2014:71–76. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra224. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M, et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(136):136ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leary RJ, Sausen M, Kinde I, et al. Detection of chromosomal alterations in the circulation of cancer patients with whole-genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(162):162ra154. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):366–377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Muller C, Holtschmidt J, Auer M, et al. Hematogenous dissemination of glioblastoma multiforme. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(247):247ra101. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Combaret V, Iacono I, Bellini A, et al. Detection of tumor ALK status in neuroblastoma patients using peripheral blood. Cancer medicine. 2015;4(4):540–550. doi: 10.1002/cam4.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kurihara S, Ueda Y, Onitake Y, et al. Circulating free DNA as noninvasive diagnostic biomarker for childhood solid tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(12):2094–2097. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kuroda T, Morikawa N, Matsuoka K, et al. Prognostic significance of circulating tumor cells and bone marrow micrometastasis in advanced neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(12):2182–2185. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klco JM, Miller CA, Griffith M, et al. Association between mutation clearance after induction therapy and outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(8):811–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kotrova M, Muzikova K, Mejstrikova E, et al. The predictive strength of next-generation sequencing MRD detection for relapse compared with current methods in childhood ALL. Blood. 2015;126(8):1045–1047. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-655159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pan X, Nariai N, Fukuhara N, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease in early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by next-generation sequencing. Br J Haematol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bjh.13948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stadt UZ, Escherich G, Indenbirken D, et al. Rapid capture next-generation sequencing in clinical diagnostics of kinase pathway aberrations in B-Cell precursor ALL. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(7):1283–1286. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Soon WW, Hariharan M, Snyder MP. High-throughput sequencing for biology and medicine. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:640. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jha P, Pia Patric IR, Shukla S, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling identifies an essential role of reactive oxygen species in pediatric glioblastoma multiforme and validates a methylome specific for H3 histone family 3A with absence of G-CIMP/isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation. Neuro-oncology. 2014;16(12):1607–1617. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature. 2012;483(7390):479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mack SC, Witt H, Piro RM, et al. Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. 2014;506(7489):445–450. doi: 10.1038/nature13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Legendre C, Gooden GC, Johnson K, et al. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of cell-free DNA identifies signature associated with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Epigenet. 2015;7(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gerlinger M, Quezada SA, Peggs KS, et al. Ultra-deep T cell receptor sequencing reveals the complexity and intratumour heterogeneity of T cell clones in renal cell carcinomas. J Pathol. 2013;231(4):424–432. doi: 10.1002/path.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gubin MM, Artyomov MN, Mardis ER, et al. Tumor neoantigens: building a framework for personalized cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3413–3421. doi: 10.1172/JCI80008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tran E, Ahmadzadeh M, Lu YC, et al. Immunogenicity of somatic mutations in human gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2015;350(6266):1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nair VS, Pritchard CC, Tewari M, et al. Design and analysis for studying microRNAs in human disease: a primer on -omic technologies. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(2):140–152. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Elie V, de Beaumais T, Fakhoury M, et al. Pharmacogenetics and individualized therapy in children: immunosuppressants, antidepressants, anticancer and anti-inflammatory drugs. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(6):827–843. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.