Abstract

Objective

This article summarizes the literature on obstetric and gynecologic complications associated with eating disorders.

Method

We performed a comprehensive search of the current literature on obstetric and gynecologic complications associated with eating disorders using PubMed. More recent randomized-controlled trials and larger data sets received priority. We also chose those that we felt would be the most relevant to providers.

Results

Common obstetric and gynecologic complications for women with eating disorders include infertility, unplanned pregnancy, miscarriage, poor nutrition during pregnancy, having a baby with small head circumference, postpartum depression and anxiety, sexual dysfunction and complications in the treatment for gynecologic cancers. There are also unique associations by eating disorder diagnosis, such as earlier cessation of breastfeeding in anorexia nervosa; increased polycystic ovarian syndrome in bulimia nervosa; and complications of obesity as a result of binge eating disorder.

Discussion

We focus on possible biological and psychosocial factors underpinning risk for poor obstetric and gynecological outcomes in eating disorders. Understanding these factors may improve both our understanding of the reproductive needs of women with eating disorders and their medical outcomes. We also highlight the importance of building multidisciplinary teams to provide comprehensive care to women with eating disorders during the reproductive years.

Keywords: obstetrics, gynecology, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, perinatal mood disorders, pregnancy, postpartum, fertility, multidisciplinary

Introduction

Eating disorders including anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), or eating disorder not otherwise specified (now Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders or OSFED in DSM-5)1 are increasingly recognized as an international problem with eating disorder rates increasing in Asia and the Arab region and rates of BN and BED increasing in Hispanic and Black American minority groups in North America.2 Given the disproportionate number of women affected by an eating disorder, obstetric and gynecologic problems are important for medical providers who treat women to understand. Although OB/GYNs provide a significant amount of primary care to women of reproductive age, a majority of OB/GYNs report that their residency training in diagnosing and treating eating disorders was barely adequate or less.3 Furthermore, eating disorder patients are also more likely to seek treatment for comorbid psychiatric illness such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) rather than for their eating disorder.4 Therefore, it is critical that specialized psychiatric providers who commonly diagnose and treat eating disorders form collaborative multidisciplinary teams with obstetrical and gynecologic providers as well as general psychiatrists to improve the care for women presenting for obstetrical and gynecologic concerns and/ or psychiatric comorbidity in the context of an eating disorder.

This article summarizes the literature on obstetric and gynecologic problems associated with eating disorders. As the female reproductive system and the systems that regulate appetite and eating behavior are closely related,5 an improved understanding of how these systems work in concert may lead to improved and targeted treatments for women with eating disorders. We also discuss the importance of multidisciplinary teams in the comprehensive care of women with eating disorders.

Method

Data Sources

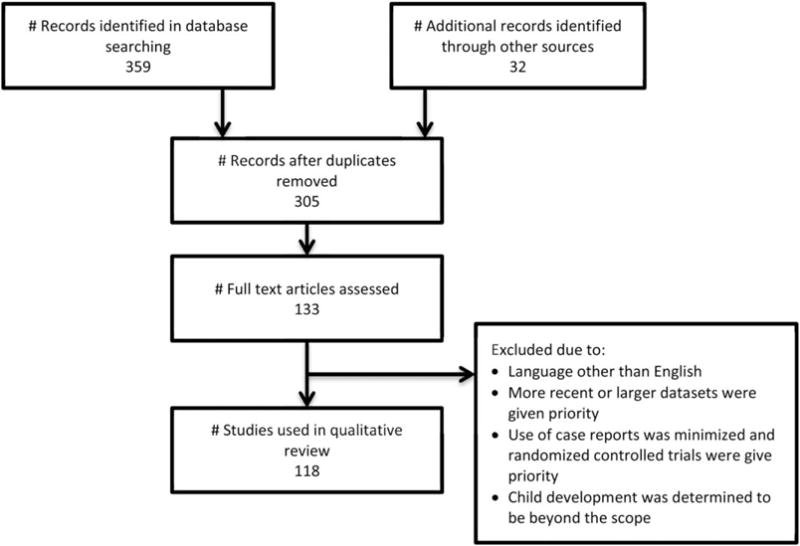

We performed a comprehensive search of the current literature on obstetric and gynecologic complications associated with eating disorders using PubMed with the following search terms: “binge eating,” “bulimia,” “anorexia,” “sexual problems,” “gynecologic problems,” “pregnancy,” “birth outcomes,” “hyperemesis,” “breast feeding,” “lactation,” “postpartum depression,” “postpartum anxiety,” “fetal development,” “feeding behavior infant,” postpartum weight loss,” “postpartum weight retention,” “perinatology,” “perinatal,” “menstrual disturbance,” “infertility,” “fertility,” “conception,” or “conceive.” We deleted duplicates and then abstracts were chosen that were felt to be the most relevant to providers. We only reviewed articles in English. No restrictions were made on date, but those published more recently were given priority. Articles from larger data sets and randomized controlled trials were also given priority. See Figure 1 for more details. We strove to include some of the possible biologic and psychosocial underpinnings between eating disorders and obstetric and gynecologic problems.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of the review.

Results

We organized the literature by grouping studies on the basis of the following medical concerns for women with eating disorders: (1) fertility concerns; (2) course during pregnancy and pregnancy concerns; (3) postpartum concerns, and (4) other gynecologic concerns. Please see Tables 1–4 for a summary of results.

TABLE 1.

During pregnancy

| Unplanned Pregnancy | Negative Emotions about Pregnancy | Eating Behaviors during Pregnancy | Gestational Weight Gain | Nutrition during Pregnancy | Hyper-emesis Gravidarum | Birth Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | |||||||

| Anorexia Nervosa | Twofold higher risk6–8 | Mixed feelings about the pregnancy persist6,7 | Remission but as high as 60% with some eating disordered behaviors9–13 | Average weight gain meets IOM guidelines14,15 | More likely vegetarian16 No vitamin or mineral deficiencies16 |

Contradictory evidence for higher risk14,17–27 | |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Markedly elevated risk28 | Negative feelings upon discovering pregnant and persist through 18 weeks6,7 | Highest rates of remission10,12 | Excessive weight gain29 | Remitted BN did not have higher odds of consuming artificial sweeteners30 | Increased risk of pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting31 Worsening of eating disorders is associated32 |

Increased odds of premature contractions, resuscitation of the neonate and very low Apgar scores at 1 minute23 Associated with preterm birth28 |

| Binge Eating Disorder | Negative feelings upon discovering pregnant6,7 | Vulnerability for onset and continuation10,12 | Excessive weight gain29 | Higher intakes of total energy, total fat, mono-saturated fat and saturated fat30 Lower intakes of folate, potassium and vitamin C30 |

Maternal hypertension, prolonged labor, LGA infant23 May be mediated by higher pre-pregnancy weight and higher gestational weight gain14 |

TABLE 4.

Treatment of amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea

| Recommendation for Weight Gain | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | Oral contraceptive pills and estrogen supplementation not found to be helpful69 Leptin may be a treatment with further study70,71 |

|

| Anorexia Nervosa | Weight gain to obtain 90% of ideal body weight versus weight gain to obtain weight at time of cessation of menses60, 65–67 Reach and maintain a target weight between the 15th and 20th BMI percentile68 |

|

| Bulimia Nervosa | No evidence found supporting amount of weight change but weight loss has been shown to improve PCOS symptoms | If patient has PCOS, treatments such as metformin and diet may be helpful72 |

| Binge Eating Disorder | No evidence found supporting amount of weight change but weight loss has been shown to improve PCOS symptoms | If patient has PCOS, treatments such as metformin and diet may be helpful72 |

Fertility Concerns

Menstrual Disturbance

Although amenorrhea was removed as a criterion in DSM-5,73 amenorrhea (absence of menstruation for >3 months) occurs in an estimated 66–84% of women with anorexia nervosa (AN),39–42 with an additional 6–11% reporting oligomenorrhea.40,41 Approximately 7–40% of patients with BN report amenorrhea and 36–64% report oligomenorrhea, while 77% of the subgroup of women with BN who had a history of AN report amenorrhea.40 The strongest predictors of amenorrhea in women with eating disorders include low BMI, low caloric intake, and higher level of exercise.40,41 However, binge eating is also associated with menstrual disturbances. Even after controlling for compensatory behaviors such as purging, PCOS, BMI and age, lifetime binge eating was significantly associated with a report of amenorrhea or oligoamenorrea compared to women who did not report lifetime binge eating.59

The mechanism for amenorrhea in patients with AN is thought to be hypothalamic in origin, specifically functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, in which there is disruption of pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus during periods of increased stress and negative energy balance.43 A drop in leptin, a hormone important for adaptation during starvation, triggers the reduction of the secretion of GnRH.44 Leptin also regulates the minute-to-minute oscillations in luteinizing hormone (LH) and the change in nocturnal rise in leptin determines the release LH before ovulation.44 Leptin is in low levels in AN due to caloric restriction and low fat mass.44 Leptin levels below 2 μg l−1 are thought to be the threshold for developing amenorrhea.45,46 Functionally, this results in dysfunction in ovulation, endometrial development, menstruation, and bone growth.4 In contrast, the mechanism for amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea in patients with BN is unclear. One small study, demonstrated that all patients with threshold or sub-threshold BN had pathologically low FSH and LH hormone levels and oligomenorrhea.55 A number of hypotheses are suggested for the increase in menstrual disturbances with BED. Hormonal dys-regulation may be the etiological root of both binge eating and menstrual disturbance.59 Binging behaviors may lead to increases in insulin, and insulin’s resultant affects on testosterone, could influence follicular maturation and ovulation.59

Weight restoration is the mainstay of treatment for amenorrhea in the setting of AN, although amenorrhea may persist even after weight has been restored.60,63 The literature regarding the degree of weight restoration needed for resumption of menses is conflicting; some experts advocate a goal of reaching ninety percent of ideal body weight and others recommend a goal of the weight at which cessation of menses occurred.60, 65–67 Reaching and maintaining a target weight between the 15th and 20th BMI percentile is recommended as a favorable treatment goal for resumption of menses within 12 months as found in a study of 172 adolescent patients with first-onset AN.68 Of note, patients with higher BMI prior to onset of AN were not as likely to resume menstruation, which provides further evidence for reaching the weight at which the cessation of menses occurred at least in some subgroups of patients.68 In one small study of adolescents with AN, when compared with those who had persisting amenorrhea, those that had resumption of menses had a significantly higher mean weight (48.4 kg v 43.8 kg), mean weight per height (96.5% vs. 87.5%), mean ovarian volume (6.2 mL vs. 4.9 mL), and mean uterine volume (14.6 mL vs. 10.8 mL).74 The authors indicate that in addition to targeting weight and weight per height in AN, pelvic ultrasound to assess ovarian and uterine volume may also be useful in assessment and management.74

Additionally, there is a small literature on using hormones levels to predict recovery. For example, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), inhibin B, and anti-mullerian hormone predicted successful recovery of ovarian function in AN patients undergoing inpatient treatment to gain weight.75 Other work has shown resumption of menses in AN patients with higher estradiol and leptin levels compared to those with prolonged amenorrhea who had higher serum cortisol levels.76

Estrogen containing pills such as oral contraceptive pills have been used to treat women with AN and menstrual loss, particularly to try to reverse effects on bone density.69 However, research to date has demonstrated that estrogen replacement and use of oral contraceptive pills is not beneficial and for example did not lead to improvement in bone density when the patient did not gain weight.69 In fact, oral contraceptive pills may mask an amenorrhea that can be an important symptom of AN.69

The role of leptin administration to assist in the resumption of menses outside of AN has been explored. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of human recombinant leptin (metreleptin) in replacement doses over 36 weeks in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea found leptin replacement resulted in resumption of menstruation and resulted in normalization in the gonadal, thyroid, growth hormone and adrenal axes including increases in estradiol and progesterone, decreases in cortisol, increases in free triiodothyronine, and a higher ratio of IGF1 to IGF binding protein 3.70 However, the average BMI for the leptin replacement group was 21.1 versus 19.8 kg m−2 for the control group, so it remains unclear whether leptin replacement will be helpful in treating patients with AN with lower BMIs. Therefore, there is a strong need for additional studies in patients with AN.71

Infertility and Miscarriage

Despite speculation that women with histories of AN will have difficulty conceiving even when in remission, many studies [including two large, population-based cohort studies.6,7] have demonstrated no differences in rates of pregnancy,17,47 reported infertility,7,18 or infertility treatment6,7, 61 for women with histories of AN compared with the general population. Furthermore, subanalyses comparing those with active versus remitted AN did not identify differences in fertility measures.17 However, two studies have suggested lower prevalence of pregnancy in women with histories of AN.18,61 Brinch et al.18 included only women who had a history of inpatient hospitalization for AN, which may represent a more medically-compromised sample. One study, which calculated fecundity ratios (number of offspring to individuals in group of interest compared with number of offspring to individuals in general population) in individuals with AN did find a significantly lower fecundity ratio in women with histories of AN (0.8); however, this measurement only accounts for live births (does not consider all gestations as in other studies, such as miscarriages or induced abortions).48 The large cohort study, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), found women with history of AN were more likely to see a doctor due to a fertility problem, but were ultimately no more likely to receive treatment for infertility than women in the general population.7 Thus, women with AN may be more likely to seek professional consultation prior to conception (one could hypothesize due to history of menstrual irregularities) even though they do not ultimately appear to be at greater risk of infertility.

Women with BN and BED may also struggle with fertility. Using data from ALSPAC, Easter et al. reported that women who had both histories of AN and BN were more likely to take longer than 6 months to conceive and to have conceived the current pregnancy with the aid of fertility treatment.6,7 In a small study of patients recruited from a freestanding infertility clinic, an academic medical center infertility center, and a academic medical center’s internal medicine practices, women seeking treatment for infertility had significantly greater scores on measures of drive for thinness and bulimic symptoms than the women recruited while attending routine primary care.77 Higher prevalence of fertility treatment may account for higher odds of twin births for those with both BN and AN and BN alone.6 Women with active BN are also at increased risk of miscarriage.19,28 However, this finding has not been universally replicated for either AN or BN.78,79 BED has been associated with greater risk of miscarriage.61 Women with BED are at higher risk of obesity, which is also associated with infertility and higher risk of miscarriage, so it is not clear if this is driving the increased risk.62

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a common cause of menstrual irregularities and fertility problems and has been associated with BN. The literature suggests that 75% of patients with BN had polycystic ovaries and ~33% of women with PCOS report bulimic eating patterns.56 PCOS is also associated with BED.59 The prevalence of EDNOS and BN is elevated above population levels in women with hirsutism, and hirsute women with eating disorders have higher levels of psychiatric comorbidity [including major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders including panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)] and suffer from lower self-esteem and poorer social adjustment.80 All participants in the study about hirsutism who were diagnosed with an eating disorder were diagnosed with PCOS.80 Interestingly, daughters of mothers who had lifetime BN had a lower ratio of the second and fourth digits of the hand (2D:4D), which is associated with high levels of fetal testosterone relative to fetal estradiol and indicates the daughters had had higher testosterone exposure.57 This may indicate androgens as a link between BN, PCOS, menstrual disturbances, and fertility issues. There is evidence that testosterone stimulates appetite, high circulating levels of this testosterone in women have been associated with impaired impulse control, irritability and depression, and antiandrogenic treatment reduces bulimic behaviors.5 If PCOS is diagnosed, metformin and diet changes increase the likelihood of having regular menses.72

Unplanned Pregnancy

In contrast to misconceptions about infertility in AN, multiple large cohort studies (from the UK, The Netherlands, and Norway) have demonstrated that women with histories of AN are actually at significantly greater risk (up to twofold) of unplanned pregnancy than women in the general population.6–8 Although periods of amenorrhea are common in women with AN, ovulation can still occur in the absence of menstruation.

Similar to patients with AN, women with active BN versus remitted BN, unplanned pregnancy was also markedly elevated compared to those with remitted BN and to have conceived with oligomenorrheic menstrual status.28

Unplanned pregnancy can increase the likelihood that a woman is unaware of her pregnancy, delay prenatal care, may engage in risky behaviors for the fetus (e.g., drinking alcohol) or fail to nourish herself adequately (e.g., consuming prenatal vitamins with needed micronutrients). The documented increased risk for unplanned pregnancy in women with eating disorders has implications for both gynecologic and primary care: discussion about the desire and options for contraception, education about the risk of pregnancy, and prevention of an unplanned pregnancy is vital for provider-patient, especially in the face of menstrual disturbances.

Course during Pregnancy and Pregnancy Concerns

Negative Emotional Experiences during Pregnancy

The perinatal time period is a time of tremendous physical and psychosocial change and must be recognized as a highly vulnerable time by those who provide perinatal care for women with eating disorders.

Women in all eating disorder groups more frequently experienced negative feelings upon discovering they are pregnant, and these feelings appear to persist in women with AN and BN through 18 weeks gestation and perhaps even longer.6,7 Data from qualitative interviews of women with eating disorders and from a systematic review of the literature documented the following themes, mothers with eating disorder histories reported: (1) Significant personal conflict in putting their child’s needs first over their desire to engage in their eating disorder, (2) Difficulties in dealing with feelings about their self-worth due to body image, (3) Concerns about their child’s health, and (4) Worry about others’ responses to their eating and weight control practices.81,82 Additional themes included fear of failure, transformation of their body and eating behaviors, and uncertainties about the child’s shape and emotional regulation.82 Clearly, sensitive and thoughtful care is necessary to adequately address concerns unique to women who suffer from an eating disorder during the perinatal period.

Eating Behaviors during Pregnancy

Studies combining eating disorders (AN, BN, and BED) into one group have found between 29 and 78% of women with eating disorders report remission of symptoms during pregnancy with decreased weight and shape concern, restrictive eating, binging, and purging.9–12

Two prospective studies in the US and UK found that women with active eating disorder symptoms before pregnancy reported a decrease in weight and shape concerns during pregnancy, although levels of concern still remained higher than women without eating disorders.79,83

A qualitative study investigating possible factors responsible for the remission of eating disorder symptoms seen during pregnancy in women with AN concluded that there are likely three main categories of influence; psychological, social, and biological.84 Psychologically, women with AN reported a sense of maternal responsibility for recovery, a changed perception of their body during pregnancy, and an ability to separate their pregnancy from the eating disorder (i.e., reporting a sense that “I’m supposed to gain weight”).84 Socially, they reported greater support during pregnancy from the father of their child, family, friends, and health care providers.84 Lastly, biological neuroendocrine changes during pregnancy [such as increased production of dihydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) by the placenta in patients with AN, which may counteract the adverse effects of cortisol] are hypothesized to play a role in increasing the likelihood of high remission rates during pregnancy.84

Several other studies suggest that the pregnancy can trigger relapse for women in recovery from eating disorders.9,20,83 One study reported that 33% of women with histories of AN experienced a relapse of symptoms during pregnancy requiring contact with a mental health professional (though none required hospitalization).20 Another also reported an increase in weight and shape concerns and eating disorder behaviors (restrictive eating, high level of exercise) during pregnancy in women with past eating disorders.83

Pregnancy was found to be a window of remission for patients with BN, but a window of vulnerability for onset and continuation of BED.10,12 A retrospective study revealed that BN behaviors improved during pregnancy, but that the number of women who were completely abstinent from bulimic symptoms did not change during pregnancy.13 In a sample of subjects who participated in a large randomized controlled trial evaluating cognitive behavior therapy for BN and then followed, childbirth was not associated with increased eating disorder symptomatology when it occurred in the 5 years following treatment for BN.85 However, individuals who responded better to treatment might be more likely to attempt pregnancy.

In a study of pregnant women seen in primary care who were >16 weeks pregnant, the prevalence of binge eating was 17.3% (of note, 26.7% of the sample reported binge eating behavior before pregnancy but only 0.6% presented a possible diagnosis of an eating disorder).86 The prevalence of BED has been thought to be rising in parallel with the rising incidence of obesity over the past 20 years.87 It is estimated up to 46% of adults with weight in the obese range may be affected by BED.88 Orloff and Hormes reviewed the evidence regarding the factors that underlie food cravings during pregnancy and noted the prominent role of cultural and psychosocial factors in addition to other factors such as hormonal influences and nutritional deficiencies.89 Further supporting the role of psychosocial factors, women with lifetime and current self-reported psychosocial adversities were at much higher risk for BN during pregnancy.90 Additionally, incident BN during the first trimester was significantly associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and low life satisfaction, whereas remission of BED symptoms was significantly associated with higher self-esteem and greater life satisfaction.91 Those with onset of BED during pregnancy are more likely to have remission, but higher BMI and psychological distress were associated with continuation of BED and from crossing over from BED to BN.38

In sum, pregnancy is a period of significant change for hormones important in appetite regulation such as leptin and cortisol. In addition, psychosocial factors warrant further study to better understand how these factors affect eating behavior, especially binge eating, during pregnancy. Pregnancy can be a vulnerable time because women with histories of eating disorders may find the physiologic changes occurring during pregnancy particularly triggering. Pregnancy also can be a time of heightened motivation and important time to address eating disorder behaviors.

Gestational Weight Gain

Large cohort studies in both Norway and the Netherlands have demonstrated greater gestational weight gain and faster rates of weight gain in women with eating disorders compared with women without eating disorders.14,21,29,33

The mean weight gain for women with AN in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) was within the appropriate range based on Institute of Medicine guidelines for a woman underweight.15 Conversely, a smaller Swedish study found that women recovered from AN prior to pregnancy had significantly lower gestational weight gain than women without histories of eating disorders (10.4 kg compared with 12.1 kg).20 This Swedish sample differed from the larger cohorts above in that all participants were recovered from eating disorders at the time of entry into the study with higher prepregnancy BMI (mean BMI 20.5 for all eating disorders). It is also notable that 33% of those with histories of AN in the Swedish study were found to relapse during pregnancy, which could explain lower rates of gestational weight gain on average in the sample.

Although greater gestational weight gain in women with AN is considered to be protective, patients with BN and BED were more likely to gain excessive gestational weight.29 Increased gestational weight gain for women with BN, EDNOS-purging type, and BED in the MoBa study may reflect ongoing binge eating, but in women with ENDOS-purging type and BN, it could also reflect better control of purging behaviors.33 Interestingly, women with BED who reported greater worry over gestational weight gain also experienced higher weight gain during pregnancy.92

Nutrition during Pregnancy

Nutrition during pregnancy is important and can vary by eating disorder. The Institute of Medicine guidelines recommend a weight gain of 28–40 lbs (12.7–18 kg) for women with a BMI of <18.5, 25–35 lbs (11.5–16 kg) for women with normal BMI, 15–25 lbs (7–11.5 kg) for women with BMI over 25 and 11–20 lbs (5–9 kg) for women with BMI over 30.93 Energy needs during pregnancy are currently estimated to be the sum of total energy expenditure of a non-pregnant woman plus the median change in total energy expenditure of 8 kcal day−1 with approximately an additional 340 and 450 kcal recommended during the second and third trimesters, respectively, for all pregnant women.94 Women with AN and low BMIs may need additional calories to ensure adequate weight gain. However, pregnant women with AN, BN or both, were not found to have significantly different energy intake compared to pregnant women without eating disorders.16 While we were unable to find specific guidelines for refeeding pregnant women with AN, based on our extensive clinical experience, we recommend starting with usual protocols for refeeding and then adapting based on pregnancy weight targets. As stated, underweight women are recommended to gain 28–40 lbs throughout their pregnancy. When setting target weights, it is important to note that the targets in pregnancy are increasing over time. Thus, the target for 20 weeks is different than the target at 30 weeks (i.e., less energy requirements are required in the first trimester compared to the second trimester compared to the third trimester). Treatment recommendations must be individualized and it is vital to discuss with all women the importance of healthy nutrition and recommended pregnancy weight gain based on prepregnancy weight.

In addition to tailoring energy to ensure appropriate weight gain, it is also essential to monitor for appropriate micro- and macro-nutrient intake. For example, all women including women with eating disorders need to ensure they get an additional estimated 21 g day−1 of protein during pregnancy.94 A UK study evaluated detailed dietary patterns and micro- and macro-nutrient intake during pregnancy in women with eating disorders.16 In this UK cohort, women with lifetime histories of AN were more likely to report vegetarian dietary patterns than women without eating disorders. However, no deficiencies were found for vitamin and mineral intake for women with AN or in any other eating disorder subgroups.16 Another study found women with BED before and during pregnancy had higher intakes of total energy, total fat, monosaturated fat, and saturated fat and lower intakes of folate, potassium, and vitamin C.30 Those with incident BED during pregnancy reported a higher intake of total energy and saturated fat.30 Additionally, women with eating disorders, with the exception of those with BN that remitted during pregnancy, had higher odds of consuming artificial sweeteners.30 which may negatively impact metabolism.95

Regarding caffeine intake during pregnancy, women with AN were more than twice as likely to consume >2,500 mg of caffeine per week than women without eating disorders, which is significantly greater than American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation of <200 mg day−1.96 Women with BED during pregnancy had higher coffee intake while women with BED that remitted during pregnancy had lower coffee consumption.30 Although the evidence remains mixed, high caffeine intake may mediate an association between AN and BED and spontaneous miscarriage, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

As studied in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, women with BN, purging type have increased risk of pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting.31 However, the prevalence of hyperemesis gravidarum did not differ between those with and without an eating disorder.31 Lingam and McCluskey noted development or worsening of eating disorders during pregnancy is associated with hyperemesis gravidarum.32 Of note, psychiatric factors such as anxiety and depression did not increase the risk of recurrence of hyperemesis gravidarum in a second pregnancy.97 The etiologies behind the development of hyperemesis gravidarum are poorly understood and it is unclear how psychological factors play a role. A group in Australia has reported they will begin to study possible genetic and environmental risk factors. Regardless, the symptoms of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy may be triggering for some patients with a history of BN, purging type.

Birth Outcomes

Studies evaluating birth outcomes and pregnancy complications in smaller clinical samples of women with AN were found to have increased risk of preterm birth,17,18,22,23 Cesarean section,17,24 low birth weight infants,17,20,22,23,25,26 small for gestational age infants (SGA),20,22,23 infants with microcephaly,20 and infants with decreased Apgar scores at 5 min,26 and greater risk of perinatal mortality.18,23 BN was associated with increased odds of premature contractions, resuscitation of the neonate and very low Apgar scores at 1 minute.23 Other work has found that BN is associated with preterm birth.28 A study of the relationship between AN and BN and obstetrical complications from delivery in the hospital from 1994 to 2004 found women with eating disorders were significantly more likely to have fetal growth restriction, preterm labor, anemia, genitourinary tract infections, and labor induction.98 Moreover, a recent study of 2,257 women with eating disorders treated clinically found that maternal eating disorders were associated with anemia, slow fetal growth, premature contractions, short duration of first stage of labor, very premature birth, small for gestational age, low birth weight, and perinatal death.23

In contrast, larger population-based cohort studies in Sweden, Norway, UK, and the Netherlands have consistently demonstrated no significant difference in adverse perinatal outcomes in women with histories of eating disorder compared with women with no history of eating disorder.14,19,21,27 Two cohort studies did find that history of AN was associated with lower mean birth weight (but not SGA)19,27 and that this effect was largely accounted for by lower pre-pregnancy BMI.19 None of the above population-based or clinical studies found any significant difference in risk of pregnancy complications of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, breech presentation, induction of labor, need for instrumental delivery, or postpartum bleeding in women with AN.

One potential explanation for the inconsistency in findings is the difference in severity of illness between clinical versus population-based samples. Many of the women in clinical samples were selected based on previous requirement of hospitalization for AN, whereas inclusion in most population-based studies required only self-reported lifetime history of AN, irrespective of treatment [with exception of Ekeus et al.27]. Therefore, adequacy of gestational weight gain may play a role; women with histories of AN in Norwegian and Dutch cohorts demonstrated faster and greater gestational weight gain than the general population,21,33 whereas some of the clinical samples reporting poor pregnancy outcomes found lower gestational weight gain among women with AN which may mediate outcomes.20,24

BED has been associated with maternal hypertension, long duration of the first and second stages of labor, and birth of large-for-gestational-age infants.23 Mothers with BED have higher birth weight babies and higher risk for large for gestational age and cesarean section than the referent group without an eating disorder. This effect may be direct or via higher maternal weight and gestational weight gain.14 Although binge eating was not significantly associated with adverse birth outcomes, gestational weight gain was higher for those with binge eating behaviors.99 As noted, PCOS is associated with BN and BED. Given insulin resistance affects 50–70% of women with PCOS,100 patients with BN or BED and PCOS may also be more likely to present with GDM. In a study from 1999 of patients with BN, 17% of pregnant women with active BN suffered from GDM.101 GDM affects 9.2% of pregnancies in the US in 2010102 and has increased over the past 20103 so GDM is more common in women with BN and the percent of women with BN and GDM may have even increased from 17% in 1999. Because macrosomia is the most common complication of GDM,104 future research should continue to study the separate and combined affects of BN or BED and GDM on the child’s development. Because lifestyle intervention is effective at delaying Type 2 diabetes in women with histories of GDM,105 women with BN or BED who develop GDM or have a history of PCOS should be counseled about the ability to decrease their risk of Type 2 diabetes with lifestyle interventions.

Postpartum Concerns

Breastfeeding

Results from population-based studies of breastfeeding in women with eating disorders are mixed, with few studies with adequately large sample sizes to permit subgroup analyses. A Swedish study of women with eating disorders106 found increased risk of cessation of breastfeeding at 6 and at 3 months postpartum, compared with the general population, with no differences found prevalence of breastfeeding initiation. A population-based study (MoBa) investigated breastfeeding practices in women with AN separated from other eating disorder subgroups and found that although there was no difference in likelihood of initiating breastfeeding in women with AN, women with AN and women with EDNOS-purging type were at increased risk of cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months.37 Older studies did not find women with eating disorders to be at increased risk for early cessation of breastfeeding107,108 even when including women with AN specifically.18

The etiology of earlier breastfeeding cessation for women with AN is not fully clear. Smaller clinical and qualitative studies have found that women with eating disorders report difficulty with breastfeeding due to insufficient milk supply25,108; concerns about insufficient milk production; and feelings of embarrassment related to potential self-exposure.25 Women with AN were more likely to report difficulties with infant feeding such as slow feeding, low milk supply or concern that their baby was not satisfied or hungry after feeding than women without eating disorders.109 Information gathering about women’s thoughts and concerns about breastfeeding should be conducted by providers during both the prenatal and postpartum periods.

Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

Women with histories of eating disorders (all subtypes) report greater depressive and anxiety symptoms both during and after pregnancy compared to women with no history of an eating disorder.9,34,35 The prevalence of postpartum depression in women with histories of any eating disorder has been estimated at 35%.24 Women with histories of eating disorders report more difficulty with adjustment postpartum than women with no history, irrespective of eating disorder subtype or length of recovery, with 50% of women with eating disorders reporting they had sought mental health care in the postpartum period.110 Both past history of depression and presence of eating disorder symptoms during pregnancy were found to confer risk for postpartum depression and anxiety for women with histories of eating disorders in ALSPAC.34 Perfectionism (specifically, concern over mistakes), has also been found to be a strong predictor of severity of postpartum depression symptoms in women with eating disorder histories.35

With respect to women with AN histories, one study found that 40% of women with AN reported feeling depressed during their pregnancy and 35% exceeded cut-off of 12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, suggesting a high probability of diagnosis of postpartum depression.35 These estimates are similar to those of Franko et al.24 for prevalence of postpartum depression across all eating disorder subgroups.24 Other work has also found that 10% of women seeking psychiatric care for peripartum depression at a tertiary care center had a past diagnosis of AN; these women were also much more likely to report past history of sexual trauma (62.5%) than controls (29.3%).36 These findings again support the interplay of eating disorder symptoms and past history of mood and/or anxiety disorders as strong predictors of depression and anxiety in the postpartum period.24,34

Women with BN and BED are at particular risk of developing postpartum depression.35 Interestingly, eating disorder histories were present in over 1/3 of admissions to a perinatal psychiatry clinic and women with BN reported more severe depression and histories of physical and sexual trauma.36 It is important for those who care for women with perinatal depression or anxiety to carefully review for a history of eating disorders. In addition, just as a self-reported history of adversity increases risk of BN during pregnancy, history of trauma is associated with higher risk of patients with BN developing perinatal depression. These associations are important not only for developing targeted treatment, but also may point to changes in the stress system that affect eating behaviors; both of which are more prevalent during the perinatal period when all these biological systems are in flux.

Postpartum Course and Weight Change

The postpartum period can be a challenging time for many women due to dissatisfaction with weight and shape and negative attitudes toward food and eating.111,112 Although many women with eating disorders experience a remission or decrease in eating disorder symptoms during pregnancy, symptoms often worsen during the postpartum period.9,11,79 While portions of women remitting at 18 and 36 months postpartum (50% and 59% for AN, 39% and 30% for BN, 46% and 57% for EDNOS, and 45% and 42% for BED) disordered eating persisted in a substantial proportion of women.38

Postpartum women with AN were found to have a greater decreases in BMI over the first 6 months postpartum compared with those women without eating disorders in a Norwegian birth cohort (MoBa).33 Although women with AN had BMIs in the underweight range prior to pregnancy for women, and experienced more rapid weight loss postpartum, they remained in the normal BMI range up to 36 months postpartum, suggesting that pregnancy may provide some sustained benefit for weight restoration.33 Further research is required to better understand factors associated with eating disorders remission after pregnancy.

Mothers with BN, BED, and EDNOS also had greater decreases in BMI over the first 6 months postpartum. Weight for all groups including those without an eating disorder remained relatively stable with small steady increases from 6 months to 3 years postpartum.33 Although those with BED experience the same steady slow increase in weight after 6 months, it is a slower weight than women with eating disorders indicating they may be more mindful of trying to maintain postpartum weight loss.33 The postpartum time period provides challenges in keeping women engaged in their own healthcare; however, it also provides opportunities to improve nutrition and weight management for women with all subtypes of eating disorders.

Other Gynecologic Concerns

Sexual Dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is common across AN and BN eating disorder subtypes.113 While most individuals with eating disorders report having had some physical intimacy with a partner, women with AN report sexual dysfunction across a variety of domains including decreased libido,49–51 higher sexual anxiety,50 and decreased self-focused sexual activity.52 An increase in sexual drive has been found to accompany weight restoration for those with AN.53 Shape concerns were associated with sexual dysfunction in patients with AN restricting type patients whereas emotional eating and subjective binge eating were associated with lower sexual functioning in patients with AN binge/purging type and BN patients.49 Women with AN or BN reporting childhood sexual abuse did not have significant improvement in sexual functioning after individualized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) while women without histories of childhood sexual abuse did show improvements.114 Quadflieg and Fichter reviewed the literature on BN and determined that while social adjustment and sexuality normalized in a number of women, there was still a large Group (40%) that continued to chronically suffer from social and sexual impairment.58 BED patients have worse sexual functioning in comparison to obese non-BED patients and controls and emotional eating, impulsivity, and shape concerns are associated with worse sexual functioning.115 Given that female sexuality involves biological, social, and psychological factors, the impact that eating disorders have on sexuality is also complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach and additional study to understand how to provide individualized care across these domains that improves quality of life around sexuality.

Gynecologic Cancers

Although women with AN do not appear to differ from the general population in the incidence of breast or female genital cancers,54 their risk of mortality from gynecologic cancers is twice as high as the general population (uterine and ovarian cancers in this sample; standardized mortality ratio = 2.7).54 The authors hypothesize that this increase in mortality could be due to delay in diagnosis and treatment of gynecologic malignancies in individuals with AN as well as decreased effectiveness of treatments due to malnutrition. Women with BED may be at increased risk of developing endometrial cancer, given that BED is associated with obesity and obese women are at increased risk of endometrial cancers.64 However, no studies studying a direct association could be found. It is important that psychiatric providers recognize the importance of encouraging their patients with eating disorders to get routine gynecologic care.

Conclusions

It is important for providers who care for women must understand the unique reproductive needs of women with eating disorders and the gynecological and obstetrical complications that may arise. For example, a female patient with an eating disorder may have irregular menses, a belief that pregnancy is unlikely or impossible, and as a result, may be less vigilant about contraception. Failure to use contraception may lead to sexually transmitted infections in addition to unplanned pregnancy. Additionally, if a patient does become pregnant when struggling with an active eating disorder, she may be at higher risk for complications during pregnancy with consequent negative impact on her child’s development both in utero and in the postpartum time period. Patients with eating disorders may also report poorer sexual functioning that further affects her quality of life and her romantic relationships. An eating disorder can also lead to higher morbidity associated with gynecologic cancers.

However, many women with an eating disorder will not disclose their disordered eating behaviors to their primary care and OB/GYN providers for fear of stigmatization or lack of empathy and understanding. A multidisciplinary approach including ongoing open communication between patients and providers is critical to treating women with eating disorders and preventing possible OB/ GYN complications. This review of the literature highlights the complexities of treating women with eating disorders and the need for OB/GYNs, pediatricians, perinatal psychiatrists, therapists, and dietitians to work together to best support the mother through reproductive transitions. Therapy may need to be focused on poor self-esteem, coping with the transitions in body shapes, support around becoming a parent as well as support around trauma histories.

Future Research Directions

Future research should clarify the unique needs of each diagnosis but also since many women who suffer from an eating disorder can exhibit multiple symptoms of different diagnoses and can crossover from one diagnosis to another.116 Future research should focus on specific behaviors (e.g., binge eating behavior, purging behavior, and restricting behavior) that exist across diagnoses. Additionally, as the prevalence of obesity continues to increase, it will be important to identify those eating behaviors associated with obesity in addition to being underweight.

Utilizing research techniques such as imaging, epigenetics or metabolomics will allow for improved understanding of the biological underpinnings of different behaviors. For example, brain imaging has demonstrated that appetite and eating pattern fluctuations are associated with menstrual cycle and may be due to hormonal influences on neural networks that both determine and respond to mood, pleasure, desire, experience and self-recognition.117

Just as the care of women with eating disorders should be multidisciplinary, research should also be multidisciplinary. The recent NURTURE (Networking, Uniting, and Reaching Out to Upgrade Relationships and Eating) study provided a parenting intervention for mothers with histories of eating disorders and serves as a model for how a multidisciplinary team can improve outcomes for patients with eating disorders and their families.118 This preliminary study found the intervention was well accepted with a 100% retention rate and documented improvements in maternal self-efficacy and competence with parenting, although there were no notable changes in maternal feeding styles or psychopathology.118 However, NURTURE serves as a model for future research that strives to address obstetric and gynecologic problems for women with eating disorders through collaboration. It also highlights the need for continued collaboration to determine how to address complicating factors such as perinatal depression or anxiety. The perinatal period provides a unique opportunity to engage women with eating disorders in treatment and help initiate behavior changes to improve their own health and the health of their children.

Future research on the relationship between eating disorders and obstetrical and gynecologic problems will not only improve treatment for women and will lead to better understanding of the complex mix of biological and psychosocial factors that underlie eating disorders as well as obstetrical and gynecologic concerns.

TABLE 2.

The postpartum time period

| Course and Weight Gain | Perinatal Depression and Anxiety | Breastfeeding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | |||

| Anorexia Nervosa | More rapid weight loss but remained normal weight up to 36 months postpartum33 | Higher risk9,34,35 Those with perinatal depression and AN more likely to report past history of sexual trauma36 |

No difference in initiating from those without eating disorders37 Increased risk of cessation before 6 months37 |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Relatively stable with small steady increase from 6 months to 3 years33 | Higher risk9,34, 35 More severe depression and higher rates of past trauma36 |

No difference in initiating from those without eating disorders37 |

| Binge Eating Disorder | Slower steady increase from 6 months to 3 years33 | Higher risk9,34, 35 Psychological distress associated with continuation and crossing over to BN38 |

No difference in initiating from those without eating disorders37 |

TABLE 3.

Gynecologic problems associated with eating disorders

| Menstrual Disturbance | Infertility | Miscarriage | Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome | Sexual Dysfunction | Gynecologic Cancers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder | ||||||

| Anorexia Nervosa | Amenorrhea predominates (even with the new definition)39–42 Functional hypogonadotropic Hypo-gonadism43 Low leptin levels below 2 μg/l associated with amenorrhea44–46 |

No differences in rates of pregnancy6,7, 17,47 | Lower fecundity ratio but did not include miscarriages so may be due to increased miscarriages48 | Decreased libido, higher sexual anxiety, decreased self-focused sexual activity49–52 Increase in sexual drive with weight restoration53 |

Higher mortality114 | |

| Bulimia Nervosa | Oligo-amenorrhea predominates46 Possible disruption in FSH and LH55 |

Possible higher rates of fertility treatment6 | Higher rates of miscarriage19,28 | Associated with PCOS56 Daughters of mothers with BN have higher fetal testosterone exposure57 |

Still a large group that suffer chronic sexual impairment58 | |

| Binge Eating Disorder | More likely to report amenorrhea or oligo-amenorrhea despite controlling for compensatory behaviors, PCOS, BMI, and age59,60 Possible association with insulin and testosterone affects60 |

Higher rates of miscarriage61 Obesity may be part of the higher rates of miscarriage62 |

Associated with PCOS60 | Worse sexual functioning even compared to obese patients without BED63 | Endometrial cancer is a risk of obesity64 |

References

- 1.Mancuso SG, Newton JR, Bosanac P, Rossell SL, Nesci JB, Castle DJ. Classification of eating disorders: Comparison of relative prevalence rates using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Br J Psychiatry J Mental Sci. 2015;206:519–520. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pike KM, Hoek HW, Dunne PE. Cultural trends and eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:436–442. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leddy MA, Jones C, Morgan MA, Schulkin J. Eating disorders and obstetric-gynecologic care. J Women’s Health. 2009;18:1395–1401. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen AE, Ryan GL. Eating disorders in the obstetric and gynecologic patient population. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1353–1367. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c070f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschberg AL. Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women. Maturitas. 2012;71:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Micali N, dos-Santos-Silva I, De Stavola B, Steenweg-de Graaf J, Jaddoe V, Hofman A, et al. Fertility treatment, twin births, and unplanned pregnancies in women with eating disorders: Findings from a population-based birth cohort. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:408–416. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Easter A, Treasure J, Micali N. Fertility and prenatal attitudes towards pregnancy in women with eating disorders: Results from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118:1491–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulik CM, Hoffman ER, Von Holle A, Torgersen L, Stoltenberg C, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Unplanned pregnancy in women with anorexia nervosa. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f7efdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Easter A, Solmi F, Bye A, Taborelli E, Corfield F, Schmidt U, et al. Antenatal and postnatal psychopathology among women with current and past eating disorders: longitudinal patterns. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2015;23:19–27. doi: 10.1002/erv.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson HJ, Von Holle A, Hamer RM, Knoph Berg C, Torgersen L, Magnus P, et al. Remission, continuation and incidence of eating disorders during early pregnancy: A validation study in a population-based birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1723–1734. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crow SJ, Agras WS, Crosby R, Halmi K, Mitchell JE. Eating disorder symptoms in pregnancy: A prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:277–279. doi: 10.1002/eat.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulik CM, Von Holle A, Hamer R, Knoph Berg C, Torgersen L, Magnus P, et al. Patterns of remission, continuation and incidence of broadly defined eating disorders during early pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Psychol Med. 2007;37:1109–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crow SJ, Keel PK, Thuras P, Mitchell JE. Bulimia symptoms and other risk behaviors during pregnancy in women with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:220–223. doi: 10.1002/eat.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bulik CM, Von Holle A, Siega-Riz AM, Torgersen L, Lie KK, Hamer RM, et al. Birth outcomes in women with eating disorders in the Norwegian Mother and Child cohort study (MoBa) Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:9–18. doi: 10.1002/eat.20578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines Weight Gain during Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micali N, Northstone K, Emmett P, Naumann U, Treasure JL. Nutritional intake and dietary patterns in pregnancy: A longitudinal study of women with lifetime eating disorders. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:2093–2099. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Fear JL, Pickering A, Dawn A, McCullin M. Fertility and reproduction in women with anorexia nervosa: A controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:130–135. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0212. quiz 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinch M, Isager T, Tolstrup K. Anorexia nervosa and motherhood: Reproduction pattern and mothering behavior of 50 women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micali N, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Risk of major adverse perinatal outcomes in women with eating disorders. Br J Psychiatry J Mental Sci. 2007;190:255–259. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.020768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koubaa S, Hallstrom T, Lindholm C, Hirschberg AL. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in women with eating disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:255–260. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000148265.90984.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micali N, De Stavola B, dos-Santos-Silva I, Steenweg-de Graaff J, Jansen PW, Jaddoe VW, et al. Perinatal outcomes and gestational weight gain in women with eating disorders: A population-based cohort study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:1493–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sollid CP, Wisborg K, Hjort J, Secher NJ. Eating disorder that was diagnosed before pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:206–210. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(03)00900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linna MS, Raevuori A, Haukka J, Suvisaari JM, Suokas JT, Gissler M. Pregnancy, obstetric, and perinatal health outcomes in eating disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:392 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franko DL, Blais MA, Becker AE, Delinsky SS, Greenwood DN, Flores AT, et al. Pregnancy complications and neonatal outcomes in women with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1461–1466. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waugh E, Bulik CM. Offspring of women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:123–133. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199903)25:2<123::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart DE, Raskin J, Garfinkel PE, MacDonald OL, Robinson GE. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1194–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ekeus C, Lindberg L, Lindblad F, Hjern A. Birth outcomes and pregnancy complications in women with a history of anorexia nervosa. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113:925–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan JF, Lacey JH, Chung E. Risk of postnatal depression, miscarriage, and preterm birth in bulimia nervosa: Retrospective controlled study. Psychosomatic Med. 2006;68:487–492. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221265.43407.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siega-Riz AM, Von Holle A, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Hamer R, Torgersen L, et al. Gestational weight gain of women with eating disorders in the Norwegian pregnancy cohort. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:428–434. doi: 10.1002/eat.20835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siega-Riz AM, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Von Holle A, Hamer R, Torgersen L, et al. Nutrient and food group intakes of women with and without bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1346–1355. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torgersen L, Von Holle A, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Berg CK, Hamer R, Sullivan P, et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in women with bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:722–727. doi: 10.1002/eat.20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lingam R, McCluskey S. Eating disorders associated with hyperemesis gravidarum. J Psychosomatic Res. 1996;40:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zerwas SC, Von Holle A, Perrin EM, Cockrell Skinner A, Reba-Harrelson L, Hamer RM, et al. Gestational and postpartum weight change patterns in mothers with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2014;22:397–404. doi: 10.1002/erv.2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micali N, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Pregnancy and post-partum depression and anxiety in a longitudinal general population cohort: The effect of eating disorders and past depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzeo SE, Slof-Op’t Landt MC, Jones I, Mitchell K, Kendler KS, Neale MC, et al. Associations among postpartum depression, eating disorders, and perfectionism in a population-based sample of adult women. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:202–211. doi: 10.1002/eat.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meltzer-Brody S, Zerwas S, Leserman J, Holle AV, Regis T, Bulik C. Eating disorders and trauma history in women with perinatal depression. J Women’s Health. 2011;20:863–870. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torgersen L, Ystrom E, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Von Holle A, Berg CK, et al. Breastfeeding practice in mothers with eating disorders. Maternal Child Nutr. 2010;6:243–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knoph C, Von Holle A, Zerwas S, Torgersen L, Tambs K, Stoltenberg C, et al. Course and predictors of maternal eating disorders in the postpartum period. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:355–368. doi: 10.1002/eat.22088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El Ghoch M, Milanese C, Calugi S, Pellegrini M, Battistini NC, Dalle Grave R. Body composition, eating disorder psychopathology, and psychological distress in anorexia nervosa: A longitudinal study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:771–778. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.078816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poyastro Pinheiro A, Thornton LM, Plotonicov KH, Tozzi F, Klump KL, Berrettini WH, et al. Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. Int J Eating Disorder. 2007;40:424–434. doi: 10.1002/eat.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham SF, Pettigrew B, Boyd C, Russell J, Taylor A. Usefulness of amenorrhoea in the diagnoses of eating disorder patients. J Psychosomatic Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;26:211–215. doi: 10.1080/01674820500064997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson TL, Andersen AE. A critical examination of the amenorrhea and weight criteria for diagnosing anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:175–182. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singhal V, Misra M, Klibanski A. Endocrinology of anorexia nervosa in young people: Recent insights. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabet Obes. 2014;21:64–70. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hebebrand J, Muller TD, Holtkamp K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. The role of leptin in anorexia nervosa: Clinical implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:23–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Audi L, Mantzoros CS, Vidal-Puig A, Vargas D, Gussinye M, Carrascosa A. Leptin in relation to resumption of menses in women with anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:544–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopp W, Blum WF, von Prittwitz S, Ziegler A, Lubbert H, Emons G, et al. Low leptin levels predict amenorrhea in underweight and eating disordered females. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:335–340. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wentz E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C, Rastam M. Fertility and history of sexual abuse at 10-year follow-up of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:294–298. doi: 10.1002/eat.20093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Power RA, Kyaga S, Uher R, MacCabe JH, Langstrom N, Landen M, et al. Fecundity of patients with schizophrenia, autism, bipolar disorder, depression, anorexia nervosa, or substance abuse vs. their unaffected siblings JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:22–30. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castellini G, Lelli L, Lo Sauro C, Fioravanti G, Vignozzi L, Maggi M, et al. Anorectic and bulimic patients suffer from relevant sexual dysfunctions. J Sexual Med. 2012;9:2590–2599. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinheiro AP, Raney TJ, Thornton LM, Fichter MM, Berrettini WH, Goldman D, et al. Sexual functioning in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:123–129. doi: 10.1002/eat.20671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raboch J, Faltus F. Sexuality of women with anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiederman MW, Pryor T, Morgan CD. The sexual experience of women diagnosed with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:109–118. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:2<109::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan JF, Lacey JH, Reid F. Anorexia nervosa: Changes in sexuality during weight restoration. Psychosomatic Med. 1999;61:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karamanis G, Skalkidou A, Tsakonas G, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Ekselius L, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in women with anorexia nervosa. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1751–1757. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resch M, Szendei G, Haasz P. Eating disorders from a gynecologic and endocrinologic view: Hormonal changes. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1151–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCluskey SE, Lacey JH, Pearce JM. Binge-eating and polycystic ovaries. Lancet. 1992;340:723. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92257-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kothari R, Gafton J, Treasure J, Micali N. 2D:4D ratio in children at familial high-risk for eating disorders: The role of prenatal testosterone exposure. Am J Hum Biol Off J Hum Biol Council. 2014;26:176–182. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quadflieg N, Fichter MM. The course and outcome of bulimia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;12(Suppl 1):I99–I109. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-1113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Algars M, Huang L, Von Holle AF, Peat CM, Thornton LM, Lichtenstein P, et al. Binge eating and menstrual dysfunction. J Psychosomatic Res. 2014;76:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mehler PS, Krantz MJ, Sachs KV. Treatments of medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Eating Disord. 2015;3:15. doi: 10.1186/s40337-015-0041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Linna MS, Raevuori A, Haukka J, Suvisaari JM, Suokas JT, Gissler M. Reproductive health outcomes in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:826–833. doi: 10.1002/eat.22179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Group ECW. Nutrition and reproduction in women. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:193–207. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kohmura H, Miyake A, Aono T, Tanizawa O. Recovery of reproductive function in patients with anorexia nervosa: A 10-year follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1986;22:293–296. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(86)90117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khaodhiar L, McCowen KC, Blackburn GL. Obesity and its comorbid conditions. Clin Cornerstone. 1999;2:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(99)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Golden NH, Jacobson MS, Schebendach J, Solanto MV, Hertz SM, Shenker IR. Resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:16–21. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170380020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swenne I. Weight requirements for return of menstruations in teenage girls with eating disorders, weight loss and secondary amenorrhoea. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:1449–1455. doi: 10.1080/08035250410033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faust JP, Goldschmidt AB, Anderson KE, Glunz C, Brown M, Loeb KL, et al. Resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa during a course of family-based treatment. J Eating Disord. 2013;1:12. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dempfle A, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Timmesfeld N, Schwarte R, Egberts KM, Pfeiffer E, et al. Predictors of the resumption of menses in adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergstrom I, Crisby M, Engstrom AM, Holcke M, Fored M, Jakobsson Kruse P, et al. Women with anorexia nervosa should not be treated with estrogen or birth control pills in a bone-sparing effect. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:877–880. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chou SH, Chamberland JP, Liu X, Matarese G, Gao C, Stefanakis R, et al. Leptin is an effective treatment for hypothalamic amenorrhea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6585–6590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015674108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hebebrand J, Albayrak O. Leptin treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa? The urgent need for initiation of clinical studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:63–66. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glueck CJ, Aregawi D, Winiarska M, Agloria M, Luo G, Sieve L, et al. Metformin-diet ameliorates coronary heart disease risk factors and facilitates resumption of regular menses in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19:831–842. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2006.19.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lai KY, de Bruyn R, Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R, Hankins M. Use of pelvic ultrasound to monitor ovarian and uterine maturity in childhood onset anorexia nervosa. Arch Dis Childhood. 1994;71:228–231. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Elburg AA, Eijkemans MJ, Kas MJ, Themmen AP, de Jong FH, van Engeland H, et al. Predictors of recovery of ovarian function during weight gain in anorexia nervosa. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:902–908. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arimura C, Nozaki T, Takakura S, Kawai K, Takii M, Sudo N, Kubo C. Predictors of menstrual resumption by patients with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord EWD. 2010;15:e226–e233. doi: 10.3275/7039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cousins A, Freizinger M, Duffy ME, Gregas M, Wolfe BE. Self-report of eating disorder symptoms among women with and without infertility. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nursing. 2015;44:380. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchell JES, Glotter HC, Soll D, Pyle EARL. A retrospective study of pregnancy in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1991;10:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Blais MA, Becker AE, Burwell RA, Flores AT, Nussbaum KM, Greenwood DN, et al. Pregnancy: Outcome and impact on symptomatology in a cohort of eating-disordered women. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:140–149. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<140::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morgan J, Scholtz S, Lacey H, Conway G. The prevalence of eating disorders in women with facial hirsutism: An epidemiological cohort study. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:427–431. doi: 10.1002/eat.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tierney S, McGlone C, Furber C. What can qualitative studies tell us about the experiences of women who are pregnant that have an eating disorder? Midwifery. 2013;29:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tierney S, Fox JR, Butterfield C, Stringer E, Furber C. Treading the tightrope between motherhood and an eating disorder: A qualitative study. Int J Nursing Stud. 2011;48:1223–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Micali N, Treasure J, Simonoff E. Eating disorders symptoms in pregnancy: A longitudinal study of women with recent and past eating disorders and obesity. J Psychosomatic Res. 2007;63:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Madsen IR, Horder K, Stoving RK. Remission of eating disorder during pregnancy: Five cases and brief clinical review. J Psychosomatic Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;30:122–126. doi: 10.1080/01674820902789217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carter FA, McIntosh VV, Joyce PR, Frampton CM, Bulik CM. Bulimia nervosa, childbirth, and psychopathology. J Psychosomatic Res. 2003;55:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Soares RM, Nunes MA, Schmidt MI, Giacomello A, Manzolli P, Camey S, et al. Inappropriate eating behaviors during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors among pregnant women attending primary care in southern Brazil. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:387–393. doi: 10.1002/eat.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity: Facts. 2015 cdcgov. [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Raymond NC, Spitzer RL. Binge eating disorder: Clinical features and treatment of a new diagnosis. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1994;1:310–325. doi: 10.3109/10673229409017098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orloff NC, Hormes JM. Pickles and ice cream! Food cravings in pregnancy: Hypotheses, preliminary evidence, and directions for future research. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1076. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Watson HJ, Von Holle A, Knoph C, Hamer RM, Torgersen L, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with bulimia nervosa during pregnancy: An internal validation study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:654–662. doi: 10.1002/eat.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knoph Berg C, Bulik CM, Von Holle A, Torgersen L, Hamer R, Sullivan P, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with broadly defined bulimia nervosa during early pregnancy: Findings from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Aust N Zealand J Psychiatry. 2008;42:396–404. doi: 10.1080/00048670801961149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Swann RA, Von Holle A, Torgersen L, Gendall K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM. Attitudes toward weight gain during pregnancy: Results from the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa) Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:394–401. doi: 10.1002/eat.20632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Council IoMaNR. Leveraging Action to Support Dissemination of Pregnancy Weight Gain Guidelines: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Medicine IO. DRI Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Protein and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swithers S. Artificial sweeteners are not the answer to childhood obesity. Appetite. 2015;93:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.ACOG Committee. Opinion No. 462: Moderate caffeine consumption during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2, Part 1):467–468. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb2a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Magtira A, Paik Schoenberg F, MacGibbon K, Tabsh K, Fejzo MS. Psychiatric factors do not affect recurrence risk of hyperemesis gravidarum. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:512–516. doi: 10.1111/jog.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bansil P, Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Kourtis AP, Posner SF, Johnson CH, et al. Eating disorders among delivery hospitalizations: Prevalence and outcomes. J Women’s Health. 2008;17:1523–1528. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nunes MA, Pinheiro AP, Camey SA, Schmidt MI. Binge eating during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A cohort study in a disadvantaged population in Brazil. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:827–831. doi: 10.1002/eat.22024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;6:1–13. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morgan JF, Lacey JH, Sedgwick PM. Impact of pregnancy on bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry J Mental Sci. 1999;174:135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ. Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prevent Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E104. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: A public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S141–S146. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mitanchez D, Yzydorczyk C, Simeoni U. What neonatal complications should the pediatrician be aware of in case of maternal gestational diabetes? World J Diabet. 2015;6:734–743. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Larsson G, Andersson-Ellstr€om A. Experiences of pregnancy-related body shape changes and of breast-feeding in women with a history of eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord RevJ Eat Disord Assoc. 2003;11:116–124. [Google Scholar]