Abstract

Background

As there is little data on vector-borne diseases of cats in the Caribbean region and even around the world, we tested feral cats from St Kitts by PCR to detect infections with Babesia, Ehrlichia and spotted fever group Rickettsia (SFGR) and surveyed them for antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii and Ehrlichia canis.

Results

Whole blood was collected from apparently healthy feral cats during spay/ neuter campaigns on St Kitts in 2011 (N = 68) and 2014 (N = 52). Sera from the 52 cats from 2014 were used to detect antibodies to Ehrlichia canis and Rickettsia rickettsii using indirect fluorescent antibody tests and DNA extracted from whole blood of a total of 119 cats (68 from 2011, and 51 from 2014) was used for PCRs for Babesia, Ehrlichia and Rickettsia. We could not amplify DNA of SFG Rickettsia in any of the samples but found DNA of E. canis in 5% (6/119), Babesia vogeli in 13% (15/119), Babesia gibsoni in 4% (5/119), mixed infections with B. gibsoni and B. vogeli in 3% (3/119), and a poorly characterized Babesia sp. in 1% (1/119). Overall, 10% of the 52 cats we tested by IFA for E. canis were positive while 42% we tested by indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) for R. rickettsii antigens were positive.

Conclusions

Our study provides the first evidence that cats can be infected with B. gibsoni and also indicates that cats in the Caribbean may be commonly exposed to other vector-borne agents including SFGR, E. canis and B. vogeli. Animal health workers should be alerted to the possibility of clinical infections in their patients while public health workers should be alerted to the possibility that zoonotic SFGR are likely circulating in the region.

Keywords: Babesia, Cat, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, Vector-borne

Background

Feral cats are common on Caribbean islands in the West Indies where they are valued by local residents due to their role in controlling rodents and rodent-associated diseases [1]. While feral cats in the region are known to be commonly infected with external and internal parasites [2–5], haemoplasmas [6] and feline immunodeficiency virus [7–9], there is very little data on vector-borne agents. Although studies on dogs have shown vector-borne diseases are very common in the Caribbean region [10–13], there have been only few studies on these infections in cats. Bartonella spp. have been shown to occur on three Caribbean islands [7, 9, 14, 15], cats seropositive against Rickettsia rickettsii have been identified on St Kitts [16], and DNA of Ehrlichia canis and Babesia vogeli have been found in cats in Trinidad [6]. As studies from southern Africa [17], China [18], Italy [19], Japan [20], Portugal [21], Spain [22], Tasmania [23], and the United States of America [24] have shown cats can be infected with a number of vector-borne agents, we carried out a serology and PCR survey to determine exposure of cats on St Kitts to the more important vector-borne agents, mainly Ehrlichia, Babesia and spotted fever group Rickettsia (SFGR).

Methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ross University School of veterinary Medicine (RUSVM).

The Feral Cat Project (FCP) of RUSVM traps, neuters or spays, and releases feral cats on St Kitts as a welfare and disease control initiative. Whole blood was collected from a convenience sample of 52 cats trapped in and around Basseterre, the capital of the island, between September and November 2014. Although no blood work was performed on the cats, all appeared normal on physical examination and during the 3 to 4 days they were in captivity. Immediately following collection, sera were separated and stored at −80 °C until serology was performed. For PCR, the buffy coat and superficial erythrocyte layers of centrifuged ETDA whole blood were collected and frozen at −80 °C until thawed for DNA extraction as described below. One cell sample was lost meaning there were 52 sera available for analysis and 51 DNA samples.

We also used archived DNA which had been extracted from buffy coats and superficial erythrocytes collected from 68 feral cats trapped and neutered as part of the FCP in 2011. Sera were not available from these cats. As above, although no routine laboratory health screens were performed, these cats also appeared healthy on physical examination and during their captivity.

Indirect fluorescent antibody assay

Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) testing was performed using E. canis (Oklahoma strain) and R. rickettsii (both kindly supplied by Dr. G Dasch, Centers for Disease Control, Georgia, Atlanta, USA) and commercial fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-cat IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) as described previously [18, 25]. Sera were initially screened at a 1:80 dilution in PBS (pH 7.4) and positive reactors were examined again at a 1:640 dilution.

DNA extraction

The DNA was extracted from aliquots (200 μL) of buffy coats using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was eluted in 200 μL elution buffer and shipped to Yangzhou University College of Veterinary Medicine of Jiangsu province, China at room temperature where it was frozen at −80 °C until PCRs were performed.

PCRs

A conventional PCR was used as described previously [26] to detect DNA of SFGR using primers ompB-forward (5′-CGACGTTAACGGTTTCTCATTCT-3′) and ompB-reverse (5′-ACCGGTTTCTTTGTAGTTTTCGTC-3′) that amplify a 252 bp portion of the outer membrane protein B.

The Ehrlichia FRET-PCR [27] and pan-Babesia FRET-PCR [28] used in this study were performed in a LightCycler 480-II real-time PCR platform as described before. The Ehrlichia FRET-PCR amplifies a 210 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA and can detect the five well recognized Ehrlichia species with a detection sensitivity of 5 copies per PCR reaction [27].

The Babesia spp. FRET-PCR amplifies a 282 to 293 bp segment of the 18S rRNA of 22 Babesia spp. with of a sensitivity of as low as 2 copies of the 18S rRNA per reaction [28]. To further confirm the identification of Babesia species, species-specific PCRs for B. vogeli (upstream primer: 5′-TTHGCGATGKWACCATTCAAGTTTCTG-3′; downstream primer: 5′-CCCAACCGTTCCTATTAACCATTACT-3′) and B. gibsoni (upstream primer: 5′-TTHGCGATGKWACCATTCAAGTTTCTG-3′; downstream primer 5′-CGTTCCTATTAACCATTACTAAGGTTCACA-3′) were established which targeted a hyper-variable region of the 18S rRNA (about 540 bp). These PCRs were performed under the same conditions as described above for the Babesia spp. FRET-qPCR.

All PCR products obtained were further verified by electrophoresis through 2% agarose gels (BIOWEST1, Hong Kong, China) before being purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), and sent for sequencing with forward and reverse primers (BGI, Shanghai, China).

Phylogenetic analysis

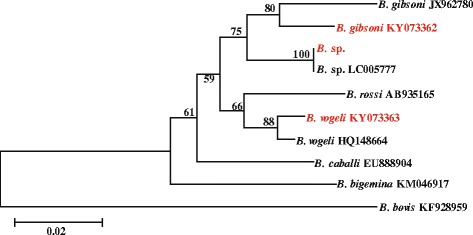

Phylogenetic analysis was performed based on the variable region of the Babesia 18S rRNA gene. Sequences identified in this study and obtained from GenBank were aligned using the Clustalx 1.83 alignment software. Based on these alignments, phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method using the Kimura 2-parameter model with MEGA 6.0. Bootstrap values were calculated using 500 replicates (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogeny of 18S rRNA of Babesia species. The variable region of the 18S rRNA (540 bp) of Babesia strains identified in this study (in red font) are compared with those of other Babesia sequences deposited in GenBank (in black font). Branch lengths are measured in nucleotide substitutions and numbers show branching percentages in bootstrap replicates. Scale bar represents the percent sequence diversity

Results

PCRs for Rickettsia, Ehrlichia and Babesia

The PCRs for SFGR were negative with DNA extracted from the 68 feral cats trapped in 2011 and the 51 cats trapped in 2014 (Table 1). Although all 68 DNA samples from cats trapped in 2011 were negative in the Ehrlichia FRET-PCR, six of 51 samples (12%) from 2014 were positive. Sequencing of the amplicons of the positive PCRs showed all had identical sequences with 28 E. canis strains in GenBank. Five of the samples were from cats that were positive by IFA for antibodies to E. canis and one cat was seronegative.

Table 1.

Serology and PCR results for blood samples collected from feral cats on St Kitts in 2011 and 2014

| Collection date | Test performed | % positive (N) | Species identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Ehrlichia FRET-PCR | 0% (0/68) | None |

| Babesia FRET-PCR | 32% (22/68) | 4 B. gibsoni

14 B. vogeli 3B. vogeli and B. gibsoni 1 Babesia sp. |

|

| Rickettsia PCR | 0% (0/68) | Not applicable | |

| 2014 | IFA for Ehrlichia | 10% (5/52) | Not applicable |

| IFA for SFG Rickettsia | 42% (22/52) | Not applicable | |

| Ehrlichia FRET-PCR | 12% (6/51) | 6 E. canis | |

| Babesia FRET-PCR | 2% (1/51) | 1 B. gibsoni | |

| Rickettsia PCR | 0% (0/51) | Not applicable |

Twenty-two of the 68 samples (31%) collected in 2011 were positive in the pan-Babesia FRET-PCR while only one of the 51 samples (2%) collected in 2014 was positive. Sequencing of the positive amplicons from the pan-Babesia FRET-PCR and those of the specific B. vogeli and B. gibsoni PCRs revealed one B. gibsoni-positive sample in 2014 (Table 1). The 21 positive samples from 2011 were mainly B. vogeli (67%; 14/21) with three samples (14%; 3/21) having evidence of a mixed infection with B. gibsoni and B. vogeli and one sample being a poorly characterized Babesia sp. (Fig. 1). The sequences of the amplicons we identified as B. vogeli in our study were all identical, as was the case with the amplicons we identified as B. gibsoni. They have been deposited in GenBank (B. vogeli accession #: KY073363; B. gibsoni accession #: KY073362) and are identical to 19 B. vogeli and identical to 37 B. gibsoni sequences (100% cover and 100% ident) recorded in GenBank, respectively.

Serology for Rickettsia and Ehrlichia

Of the 52 stray cats sampled in 2014, only 10% (5/52) had antibodies to E. canis in the IFAs and all were at low titer, arbitrarily defined as 1:80 to 1:320. More of these cats were seropositive for SFGR (42%; 22/52) with 5 (10%) having high titers, arbitrarily defined as 1:640 or greater (Table 1).

Discussion

Our results show feral cats on St Kitts are not uncommonly exposed to a variety of vector-borne agents. In a report from 2010 on feral cats from St Kitts [29], 66% of cats were seropositive for SFGR and our later studies confirm exposure to SFGR is common in cats on the island with 42% of the cat samples collected in 2014 being positive. These levels of SFGR seropositivity are somewhat higher than those reported elsewhere, mainly southern Africa (29%) [17], China (21%) [18], Italy (55%) [19], Japan (1%) [20], Portugal (19%) [21], Spain (28%) [22], Tasmania (59%) [23], and the US (11%-17%) [24, 30]. We suspect this is most likely due to the warm and humid tropical conditions on the island throughout the year which promotes the survival of ticks and fleas which are the main vectors of the SFGR.

As there is considerable cross-reactivity between the numerous SFGR in IFA tests [31] we could not determine the species infecting the cats we studied. Although cats have been found to be PCR positive for Rickettsia conorii and Rickettsia masilliae in Spain [22], animals [32–34] and people [35] infected with SFGR are generally only rickettsemic for very short periods and it was not unexpected that our PCR assays for Rickettsia were negative.

A number of SFGR have been shown to be present in ticks and fleas on St Kitts, mainly Rickettsia felis [29], Rickettsia africae [7], the Israeli tick typhus group rickettsia, R. rickettsii and Rickettsia rhipicephali [36]. Of these, R. felis and R. africae are found most commonly but, as R. africae is found in Amblyomma variegatum, the tropical bont tick, which mainly feeds on large ruminants and only very infrequently on cats, it seems most likely the seroconversions we recorded were due to exposure to R. felis which has been found in 19% of cat fleas on the island [29]. Rickettsia felis is a recently described SFGR that is an emerging pathogen causing flea-borne spotted fever in people [37]. The cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis, is considered to be its major reservoir and biological vector [38]. Cats seem unlikely to be important vertebrate reservoirs [39] as they are rickettsemic for only short periods after infection [40] and, in PCR surveys, they are mostly found to be PCR negative [18, 22, 24] although sometimes PCR positive animals have been reported [41]. There is little information on the pathogenicity of R. felis in cats but most infections appear subclinical with a brief rickettsemia before reactive antibodies develop and clear infections [40].

Although the SFGR identified on St Kitts to date, with the exception of R. rhipicephali, are human pathogens there is little data on these zoonoses in the Caribbean. Infections with R. africae have been described in tourists to the region [42] and a small serosurvey showed 34% of people from 10 islands had serological evidence of a previous infection [43]. Further studies are needed to determine the extent of SFG rickettsioses in the Caribbean and the role cats might play in these infections.

Previous studies have reported a variety of Babesia in wild and domestic cats from around the world [44–53]. The poorly characterized Babesia sp. we found was most closely related (99.3%; 281/283 matches) to a Babesia (KP221651) identified in a sheep from St Kitts (Fig. 1) in a previous study [28]. Further studies are needed to further characterize this organism and identify its vector.

The Babesia we identified most commonly in our Caribbean cats was B. vogeli which has also been found in apparently healthy cats in Brazil [48, 54], Thailand [46] and Portugal [51]. B. vogeli commonly infects dogs in tropical and subtropical areas with prevalences of 4 to 60% [55] and studies in St Kitts have found 7% and 12% of dogs were PCR positive [11, 56]. The organism is transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato and infections are mostly subclinical in dogs with most infected animals becoming subclinical carriers [16]. Although R. sanguineus s. l. is common on St Kitts and in the Caribbean and is essentially the only tick found on dogs in the region [11, 56], it has a near-strict host preference for dogs. The only ectoparasites we identified on the cats we studied were cat fleas (C. felis) and the fur mite (Lynxacarus radovskyi), both of which were common. We did not find ticks on any of the cats we tested and while there was relatively high prevalence of B. vogeli in our study. The reason that ticks were infrequently found on cats is due to that they are such efficient groomers.

To the best of our knowledge, the other Babesia we found to occur commonly, B. gibsoni, has not previously been described in cats. The organism, however, is encountered relatively frequently (5%) in healthy dogs on St Kitts and also in dogs with a suspected vector-borne disease (15%) and clinical and laboratory abnormalities [11, 56]. The cats we found infected in our study were all apparently normal on physical examination and therefore seem to have had subclinical infections. It is known that infections with other Babesia, mainly B. felis [55], B. canis presentii [44] and B. lengau [50], can be associated with laboratory abnormalities and clinical signs and further studies are underway in our laboratories to determine the effects of infections in cats with the Babesia we identified in our study.

The third most prevalent vector-borne agent we detected in our cats was E. canis. This is an agent of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis which is transmitted by the brown dog tick, R. sanguineus. Infections in dogs are very common around the world and on St Kitts infection levels of 12 to 27% have been reported [11, 56]. There are relatively few studies on E. canis in cats but seropositive animals have been described from around the world, for example 6% in southern Africa [25], 6 to 45% in Brazil [57], 10% in Spain [58] and 82% in the US [59]. Elsewhere, seroprevalence studies have tended to overestimate infection rates demonstrated by positive PCR [60], but in our study all seropositive animals were also PCR positive. This might indicate the cats in our study were relatively recently infected and had not had time to self-cure as has been shown to occur in dogs [61]. Although all the cats in our study appeared healthy on physical examination, cats infected with E. canis have been reported to suffer from fever, lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly, polyarthritis, bone marrow hypoplasia and anemia [60, 62].

Conclusions

Our study shows feral cats on St Kitts are relatively commonly exposed and infected with a variety of vector-borne agents. In many cases the effects of infection on cats is unknown and potentially treatable conditions might be going undiagnosed. Also, many of the agents can infect dogs and people which live in close proximity to the cats and share their ectoparasites. Animal health workers should be alerted to the possibility of clinical infections in their feline and canine patients while public health workers should be alerted to the possibility that cats may play a role in the epidemiology of zoonotic vector-borne diseases in the region.

Acknowledgements

We thank the RUSVM FCP TNR program for providing access to samples and A Daffara, M Henderson, C Mitchell, S Manning, A Shliselberg, and J Wright for technical assistance.

Funding

This project was funded by the Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine, the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, P. R. China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO: 31,272,575).

Availability of data and materials

The genomic sequences obtained in this study were deposited in GenBank.

Authors’ contributions

PJK, LK and CW designed the study. LK, JL, JZ, KH, GCB, SM and MV conducted the experiments. PJK, LK and CW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Please find the detailed author information in the title page of this MS.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine (RUSVM).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Patrick John Kelly, Email: pkelly@rossvet.edu.kn.

Liza Köster, Email: lizakoster@gmail.com.

Jing Li, Email: lijing900401@163.com.

Jilei Zhang, Email: zhangjilei0103@163.com.

Ke Huang, Email: huangke126@126.com.

Gillian Carmichael Branford, Email: gcarmichaelbranford@rossvet.edu.kn.

Silvia Marchi, Email: smarchi@rossvet.edu.kn.

Michel Vandenplas, Email: mvandenplas@rossvet.edu.kn.

Chengming Wang, Phone: +1-334-844-2601, Email: wangche@auburn.edu.

References

- 1.Moura L, Kelly P, Krecek RC, Dubey JP. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in cats from St. Kitts, West Indies. J Parasitol. 2007;93:952–953. doi: 10.1645/GE-1195R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Headley SA, Gillen MA, Sanches AW, Satti MZ. Platynosomum fastosum-induced chronic intrahepatic cholangitis and Spirometra spp. infections in feral cats from grand Cayman. J Helminthol. 2012;86:209–214. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X11000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez C, Chikweto A, Mofya S, Lanum L, Flynn P, Burnett JP, et al. A serological study of Dirofilaria immitis in feral cats in Grenada, West Indies. J Helminthol. 2010;84:390–393. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X10000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krecek RC, Moura L, Lucas H, Kelly P. Parasites of stray cats (Felis domesticus L., 1758) on St. Kitts, West Indies. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moura L, Miller T, Thurk J, Kelly PJ, Krecek T. Animal ownership and attitudes to feral cats on St Kitts, West Indies. West Indian Vet J. 2007;7:3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georges K, Ezeokoli C, Auguste T, Seepersad N, Pottinger A, Sparagano O, et al. A comparison of real-time PCR and reverse line blot hybridization in detecting feline haemoplasmas of domestic cats and an analysis of risk factors associated with haemoplasma infections. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly P, Mahan S, Lucas H, Yowell C, Beati L, Dame J. Survey for Rickettsia africae in Amblyomma variegatum and domestic ruminants on seven Caribbean islands. J Parasitol. 2010;96:1086–1088. doi: 10.1645/GE-2552.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly PJ, Stocking R, Gao D, Phillips N, Xu C, Kaltenboeck B, et al. Identification of feline immunodeficiency virus subtype-B on St. Kitts, West Indies by quantitative PCR. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:480–483. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubey JP, Lappin MR, Kwok OC, Mofya S, Chikweto A, Baffa A, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and concurrent Bartonella spp., feline immunodeficiency virus, and feline leukemia virus infections in cats from Grenada, West Indies. J Parasitol. 2009;95:1129–1133. doi: 10.1645/GE-2114.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanza-Perea M, Zieger U, Qurollo BA, Hegarty BC, Pultorak EL, Kumthekar S, et al. Intraoperative bleeding in dogs from Grenada seroreactive to Anaplasma platys and Ehrlichia canis. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28:1702–1707. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loftis AD, Kelly PJ, Freeman MD, Fitzharris S, Beeler-Marfisi J, Wang C. Tick-borne pathogens and disease in dogs on St. Kitts, West Indies. Vet Parasitol. 2013;196:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yabsley MJ, McKibben J, Macpherson CN, Cattan PF, Cherry NA, Hegarty BC, et al. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, Babesia canis vogeli, Hepatozoon canis, Bartonella vinsoniiberkhoffii, and Rickettsia spp. in dogs from Grenada. Vet Parasitol. 2008;151:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei L, Kelly P, Ackerson K, Zhang J, Sayed H, El-Mahallawy HS, et al. First report of Babesia gibsoni in central America and survey for vector-borne infections in dogs from Nicaragua. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:126. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messam LL, Kasten RW, Ritchie MJ, Chomel BB. Bartonella henselae and domestic cats, Jamaica. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1146–1147. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.050115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rampersad JN, Watkins JD, Samlal MS, Deonanan R, Ramsubeik S. Ammons DR. a nested-PCR with an internal amplification control for the detection and differentiation of Bartonella henselae and B. clarridgeiae: an examination of cats in Trinidad. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly PJ, Moura L, Miller T, Thurk J, Perreault N, Weil A, et al. Feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus and Bartonella species in stray cats on St Kitts, West Indies. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12:447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthewman LA, Kelly PJ, Hayter D, Downie S, Wray K, Bryson N, et al. Domestic cats as indicators of the presence of spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:109–111. doi: 10.1023/A:1007375718204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Lu G, Kelly P, Zhang Z, Wei L, Yu D, et al. First report of Rickettsia felis in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:682. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0682-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persichetti MF, Solano-Gallego L, Serrano L, Altet L, Reale S, Masucci M, et al. Detection of vector-borne pathogens in cats and their ectoparasites in southern Italy. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:247. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1534-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabuchi M, Jilintai, Sakata Y, Miyazaki N, Inokuma H. Serological survey of Rickettsia japonica infection in dogs and cats in Japan. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1526–1528. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00333-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alves AS, Milhano N, Santos-Silva M, Santos AS, Vilhena M, Sousa R. Evidence of Bartonella spp., Rickettsia spp. and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in domestic, shelter and stray cat blood and fleas, Portugal. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl 2):1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segura F, Pons I, Miret J, Pla J, Ortuno A, Nogueras MM. The role of cats in the eco-epidemiology of spotted fever group diseases. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:353. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izzard L, Cox E, Stenos J, Waterston M, Fenwick S, Graves S. Serological prevalence study of exposure of cats and dogs in Launceston, Tasmania, Australia to spotted fever group rickettsiae. Aust Vet J. 2010;88:29–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2009.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayliss DB, Morris AK, Horta MC, Labruna MB, Radecki SV, Hawley JR, et al. Prevalence of Rickettsia species antibodies and Rickettsia species DNA in the blood of cats with and without fever. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:266–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Matthewman LA, Kelly PJ, Wray K, Bryson N, Rycroft A, Raoult D, et al. Antibodies in cat sera from southern Africa react with antigens of Ehrlichia canis. Vet Rec. 1996;138:364–365. doi: 10.1136/vr.138.15.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billeter SA, Metzger ME. Limited evidence for Rickettsia felis as a cause of zoonotic flea-borne rickettsiosis in Southern California. J Med Entomol. 2017;54(1):4–7. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjw179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Kelly P, Guo W, Xu C, Wei L, Jongejan F, et al. Development of a generic Ehrlichia FRET-qPCR and investigation of ehrlichioses in domestic ruminants on five Caribbean islands. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:506. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Kelly P, Zhang J, Xu C, Wang C. Development of a pan-Babesia FRET-qPCR and a survey of livestock from five Caribbean islands. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:246. doi: 10.1186/s12917-015-0560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly PJ, Lucas H, Eremeeva ME, Dirks KG, Rolain JM, Yowell C, et al. Rickettsia felis, West Indies. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:570–571. doi: 10.3201/eid1603.091431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Case JB, Chomel B, Nicholson W, Foley JE. Serological survey of vector-borne zoonotic pathogens in pet cats and cats from animal shelters and feral colonies. J Feline Med Surg. 2006;8:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beati L, Kelly PJ, Mason PR, Raoult D. Species-specific BALB/c mouse antibodies to rickettsiae studied by western blotting. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:339–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly PJ, Mason PR. Role of cattle in the epidemiology of tick-bite fever in Zimbabwe. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:256–259. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.256-259.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly PJ, Mason PR, Rhode C, Dziva F, Matthewman L. Transient infections of goats with a novel spotted fever group rickettsia from Zimbabwe. Res Vet Sci. 1991;51:268–271. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(91)90076-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly PJ, Matthewman LA, Mason PR, Courtney S, Katsande C, Rukwava J. Experimental infection of dogs with a Zimbabwean strain of Rickettsia conorii. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;95:322–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, Drexler NA, Dumler JS, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Tick borne Rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever and other spotted fever group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis - United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–44. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly PJ, Dirks KG, Eremeeva ME, Zambrano ML, Krecek T, Dasch GA: Detection of Rickettsia and Ehrlichia in ticks and fleas from the island of St. Kitts. In Proceeding of the 23rd Meeting of the American Society for Rickettsiology, Abstract #108: 2009.

- 37.Parola P. Rickettsia felis: from a rare disease in the USA to a common cause of fever in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:996–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reif KE, Macaluso KR. Ecology of Rickettsia felis: a review. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:723–736. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hii SF, Kopp SR, Thompson MF, O’Leary CA, Rees RL, Traub RJ. Molecular evidence of Rickettsia felis infection in dogs from northern territory, Australia. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:198. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wedincamp J, Jr, Foil LD. Infection and seroconversion of cats exposed to cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis Bouche) infected with Rickettsia felis. J Vector Ecol. 2000;25:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed R, Paul SK, Hossain MA, Ahmed S, Mahmud MC, Nasreen SA, et al. Molecular detection of Rickettsia felis in humans, cats, and cat fleas in Bangladesh, 2013-2014. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:356–358. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2015.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly PJ. Rickettia africae in the West Indies. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:224–226. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wood H, Drebot MA, Dewailly E, Dillon L, Dimitrova K, Forde M, et al. Seroprevalence of seven zoonotic pathogens in pregnant women from the Caribbean. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:642–644. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baneth G, Kenny MJ, Tasker S, Anug Y, Shkap V, Levy A, et al. Infection with a proposed new subspecies of Babesia canis, Babesia canis subsp. presentii, in domestic cats. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:99–105. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.99-105.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suliman EG. Detection the infection with Babesia spp. Cytauxzoon felis and Haemobaronella felis in stray cats in Mosul. Iraqi J Vet Sci. 2009;23:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simking P, Wongnakphet S, Stich RW, Jittapalapong S. Detection of Babesia vogeli in stray cats of metropolitan Bangkok, Thailand. Vet Parasitol. 2010;173:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solano-Gallego L, BanethG Babesiosis in dogs and cats-expanding parasitological and clinical spectra. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.André MR, Herrera HM, Fernandes Sde J, de Sousa KC, Gonçalves LR, Domingos IH, et al. Tick-borne agents in domesticated and stray cats from the city of Campo Grande, state of Mato Grosso do Sul, midwestern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong SS, Poon RW, Hui JJ, Yuen KY. Detection of Babesia hongkongensis sp. nov. in a free-roaming Felis Catus cat in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2799–2803. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01300-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bosman AM, Oosthuizen MC, Venter EH, Steyl JC, Gous TA, Penzhorn BL. Babesia lengau associated with cerebral and haemolytic babesiosis in two domestic cats. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:128. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vilhena H, Martinez-Díaz VL, Cardoso L, Vieira L, Altet L, Francino O, et al. Feline vector-borne pathogens in the north and centre of Portugal. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:99. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly P, Marabini L, Dutlow K, Zhang J, Loftis A, Wang C. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens in captive wild felids, Zimbabwe. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:514. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0514-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spada E, Proverbio D, Galluzzo P, Perego R, De Giorgi G B. Frequency of piroplasms Babesia microti and Cytauxzoon felis in stray cats from northern Italy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:943754. doi: 10.1155/2014/943754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malheiros J, Costa MM, do Amaral RB, de Sousa KC, André MR, Machado RZ, et al. Identification of vector-borne pathogens in dogs and cats from southern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taboada J, Lobetti R. In: Babesiosis. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Greene CE, editor. Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 722–736. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly PJ, Xu C, Lucas H, Loftis A, Abete J, Zeoli F, et al. Ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, anaplasmosis and hepatozoonosis in dogs from St Kitts, West Indies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braga IA, dos Santos LG, de Souza Ramos DG, Melo AL, da Cruz Mestre GL, de Aguiar DM. Detection of Ehrlichia canis in domestic cats in the central-western region of Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;45:641–645. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822014000200036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ayllon T, Diniz PP, Breitschwerdt EB, Villaescusa A, Rodriguez-Franco F, Sainz A. Vector-borne diseases in client-owned and stray cats from Madrid, Spain. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:143–150. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bouloy RP, Lappin MR, Holland CH, Thrall MA, Baker D, O'Neil S. Clinical ehrlichiosis in a cat. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994;204:1475–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braga IA, dos Santos LG, Melo AL, Jaune FW, Ziliani TF, Girardi AF, et al. Hematological values associated to the serological and molecular diagnostic in cats suspected of Ehrlichia canis infection. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2013;22:470–474. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612013000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Breitschwerdt EB, Hegarty BC, Hancock SI. Doxycycline hyclate treatment of experimental canine ehrlichiosis followed by challenge inoculation with two Ehrlichia canis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:362–368. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breitschwerdt EB, Abrams-Ogg AC, Lappin MR, Bienzle D, Hancock SI, Cowan SM, et al. Molecular evidence supporting Ehrlichia canis-like infection in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16:642–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2002.tb02402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The genomic sequences obtained in this study were deposited in GenBank.