Abstract

The germplasm collection of 87 wheat-wheatgrass hybrids developed in Tsitisin Main Botanical Garden (Russia, Moscow) was evaluated for resistance to pre-harvest sprouting (PHS) by spike sprouting (SS) and germination index (GI) assays as well as for spike and grain features. The PHS resistance variation and haplotype polymorphism of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 and wheat TaVp-1B genes orthologues of Vp-1 was revealed in the studied collection. Four haplotypes of ThVp-1 were revealed: ThVp-1a (41% of the entries), ThVp-1b (13%), ThVp-1c (29%), and ThVp-1d (15%). The association between the allelic state of ThVp-1 and PHS resistance in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids was shown: haplotype ThVp-1d of the wheatgrass Vp-1 gene is significantly associated with reduced PHS in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids (mean SS 0.33, mean GI 0.64). The resistant entries may be perspective as a source of PHS resistance in the development of commercial cultivars of perennial wheat.

Introduction

Wheat-wheatgrass hybrids are partial amphidiploids produced by crossing Trtitcum species and various wheatgrass species. Bread wheat (T. aestivum L., 2n = 6x = 42, genome composition BBAADD) and intermediate wheatgrass (Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey, 2n = 6x = 42, genome composition JvsJvsJrJrStSt) or tall wheatgrass (Th. ponticum (Podp.) Z.-W. Liu & R.-C. Wang, 2n = 10x = 70, genome composition JJJJJJJsJsJsJs) are the most commonly used for the development of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids. The genetically stable wheat-wheatgrass hybrids are mainly octaploid (2n = 56), carrying 42 chromosomes of wheat and 14 chromosomes from various subgenomes of wheatgrass. Different wheat-wheatgrass amphidiploids carry various combinations of wheatgrass chromosomes [1–5].

The wheat-wheatgrass hybrids were developed in many countries, including Russia, USA, Germany, Canada and China. N. V. Tsitsin was the first who crossed wheat and wheatgrass (Thinopyrum sp.) in order to obtain perennial wheat in the 1920s and whose cultivars of partial amphiploid wheat-wheatgrass hybrids were recommended for cultivation at an industrial scale in the former USSR in the 1970s [6]. The aim of the development of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids was to combine the quality of bread wheat with economically beneficial properties of wheatgrass, such as perennial life, winter hardiness and frost resistance, resistance to diseases and pests, and tolerance to abiotic stresses (cold, drought, salinity, etc.). Despite the great potential as a grain or forage crop, wheat-wheatgrass hybrids are currently not cultivated at an industrial scale. However, recently, wheat-wheatgrass hybrid once again attracted attention as a perspective crop [4, 5, 7, 8]. Perennial wheat is an example of a transformative technology, having a number of technological and economic advantages over annual crops: perennial wheat is able to reduce the impact on the environment, is less expensive to manage and can provide stable yields on marginal lands [9, 10]. Wheat-wheatgrass hybrids differ in resistance to diseases and pests [11, 12]. Several resistance genes to fungal, viral diseases and pests were transferred from the genomes of intermediate and tall wheatgrasses into wheat genome [13, 14]. Thus, wheat-wheatgrass hybrids can be used as a breeding bridge between wheat and wheatgrass as a source of valuable traits genes for wheat improvement.

Pre-harvest sprouting (PHS) poses a serious problem for production of cereals including wheat in many grain-producing regions of Russia, Canada, USA and China and needs improvement by breeding [15–17]. PHS occurs in response to heavy rains and dew during harvest and can lead to serious yield losses and reduced grain quality. Flour produced from sprouted grain has a low falling number because of high activity of alpha-amylases that breaks down starch and reduces baking quality [18, 19].

The germination of grain is influenced by a large number of environmental and inherited genetic factors, among the latter the most important are spike morphology and seed dormancy. PHS resistance is influenced by such inherited spike features as spike shape, presence of awns, openness of florets, glume rigidity and germination inhibitors in husks [20], epicuticular wax of glumes, glume adherence, spike inclination and others [21]. Seed dormancy is determined by seed coat and embryo features [22]. Seed coat determines the rate of moisture penetration into the seed. In addition, the seed coat may contain germination inhibitors. The red color of wheat grain is associated with dormancy provided by seed coat and determined by gene R mapped to distal region of homeological group 3 [16, 22, 23–28]. The effect of the red color of seed coat may be explained by a genetic linkage between PHS resistance genes and the R gene or it may be due to a pleiotropic effect of the R gene [23]. Later it was shown that the R genes for grain color are transcriptional activators of the flavonoid synthesis genes TaMyb10 [27].

A total of 110 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) or loci associated with PHS resistance in wheat have been mapped to all wheat chromosomes [29–32], the majority of them are located on the group three chromosomes [33–38] and chromosome 4A [30, 39–41]. Consequently, genes underlying these QTLs were identified such as TaPHS1 for Qphs.pseru-3AS on 3AS [42] and most likely TaMKK3-A for Phs-A1 on 4AL [43]. There is increasing evidence that epigenetic changes through DNA and histone methylation may play a role in seed dormancy and, therefore, may determine the PHS resistance of cultivars [44, 45]. In cereals, the role of ARGONAUTE4_9 class genes in wheat and barley PHS resistance was explored recently and the correlation between DNA methylation status, polymorphism in AGO802B and PHS resistance was demonstrated in wheat [46, 47].

The Viviparous-1 (Vp-1) gene is an important regulator of late embryogenesis in maize and a regulator of late embryo development in bread wheat [48]. Vp-1 plays an important role in processes of seed maturation, such as dehydration and the transition to dormancy in various plant species [49–52]. The Vp-1 gene encodes an important dormancy-related transcription factor that is involved in the abscisic acid (ABA) signal transduction: a positive correlation was observed between seed dormancy and embryo sensitivity to ABA [53, 54].

The Vp-1 genes of wheat, TaVp-1, are localized on the long arms of the homeologous group 3 chromosomes. Six alleles of TaVp-1B were identified and designated as TaVp-1Ba, TaVp-1Bb, TaVp-1Bc, TaVp-1Bd, TaVp-1Be, and TaVp-1Bf [28, 55–57]. The alleles TaVp-1Bb and TaVp-1Bc detected by an STS molecular marker are associated with higher seed dormancy and PHS resistance [28]. For the TaVp-1A gene, also some allelic variations associated with PHS resistance were detected [58]. In general, allelic variants of Vp-1 affect PHS resistance in white-grained wheat. However, the effect of the allelic state of the Vp-1 gene on PHS resistance was shown in red-grained triticale depending on the intensity of the grain color [59].

At the present time, two molecular markers based on the sequences of the orthologous Vp-1 genes of Thinopyrum intermedium, Th. ponticum, Th. bessarabicum (Savul. & Rayss) and Pseudoroegneria spicata (Pursh) have been developed. These markers allow for the identification of various alleles of the Vp-1 gene orthologue of wheatgrass (ThVp-1) in a wheat background [60, 61]. The primers for the markers were designed on the conservative regions while the sequence between them is highly polymorphic and can be distinguished directly by PCR using the STS marker Vivip [61] or with preliminary restriction endonuclease digestion using the CAPS marker Vp1BB4_HaeIII [60]. The effect of ThVp-1 on seed dormancy has never been explored.

Although PHS resistance is important for both the development of commercial cultivars of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids and for wheat breeding using wheat-wheatgrass germplasm, this trait has not been studied yet in wheat-wheatgrass hybrids. The aim of this work is to study the germplasm collection of the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids for PHS resistance using different assays, and to assess the effect of grain color, spike parameters and Vp-1 of wheat and wheatgrass on PHS resistance.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The wheat-wheatgrass hybrid germplasm collection includes 87 entries bred by N.V. Tsitsin, V.F. Lyubimova, V.I. Belov et al. (Department of Distant Hybridization, Tsitsin Main Botanical Garden, Russian Academy of Sciences) (Table 1). Bread wheat cv. Nota and Th. intermedium accession PI 401200 (Germplasm Research International Network) were used as controls for the TaVp-1 and ThVp-1 genes, respectively, in PCR experiments.

Table 1. Characteristics of the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection.

| Entry | Wheatgrass ThVp-1 haplotype | Wheat Vp-1 allele | GI | SS* | Grain color | Glume color | Awn presence (+) / absence (–) |

Threshability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.69 | 0.56 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 33 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.94 | 0.48 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 49 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.81 | 0.51 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 90 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.74 | 0.58 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 166 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.71 | 0.33 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 168 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.62 | 0.51 | dark red | red | – | easy |

| 186 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.85 | 0.52 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 192 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.91 | 0.55 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 237 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.89 | 0.5 | light red | white | + | hard |

| 243 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.68 | 0.45 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 249 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.73 | 0.61 | dark red | white | + | easy |

| 548 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.75 | 0.66 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1375 | ThVp-1d | hg | 0.78 | 0.42 | dark red | white | – | hard |

| 1382 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.86 | 0.36 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1451 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.87 | 0.01 | blue | white | – | hard |

| 1512 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.64 | 0.49 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1514 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Bc | 0.95 | 0.5 | dark red | red | – | easy |

| 1533 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.54 | 0.04 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1546 | ThVp-1c | hg | 0.77 | 0.54 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1626 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.76 | 0.41 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1646 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.90 | 0.40 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1654 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.62 | 0.01 | blue | white | – | hard |

| 1674 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.78 | 0.44 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 1689 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.73 | 0.44 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1690 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.78 | 0.66 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1692 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.60 | 0.62 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1735 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.42 | 0.08 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1737 | ThVp-1a | hg | 0.61 | 0.48 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1744 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.73 | 0.12 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1745 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.61 | 0.09 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1748 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.72 | 0.07 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1755 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.90 | 0.45 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1761 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.91 | n/a | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1770 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Ba | 0.99 | 0.58 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1772 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.94 | 0.81 | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1774 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.45 | 0.12 | dark red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1777 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.60 | 0.29 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1780 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.61 | 0.01 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1783 | ThVp-1a | hg | 0.71 | 0.33 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1784 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.95 | 0.81 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1788 | ThVp-1a | hg | 0.93 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1792 | ThVp-1c | hg | 0.93 | 0.89 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1803 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.97 | 0.86 | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1805 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.92 | 0.65 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1842 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.87 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1866 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.74 | 0.52 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1868 | ThVp-1c | hg | 0.85 | 0.46 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1869 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.87 | 0.29 | dark red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1872 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.99 | 0.69 | dark red | red | + | easy |

| 1874 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.86 | 0.09 | dark red | red | – | easy |

| 1876 | ThVp-1d | hg | 0.52 | 0.25 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1877 | ThVp-1a | hg | 0.81 | 0.51 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1878 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.68 | 0.45 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 2087 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.73 | 0.41 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 3215 | ThVp-1c | hg | 0.85 | 0.44 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 3240 | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.80 | 0.54 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 4015 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.68 | 0.64 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 4023 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.80 | 0.59 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 4044 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.98 | 0.86 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 4056 | hg | hg | 0.74 | 0.89 | n/a | white | – | easy |

| 4061 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Ba | 0.83 | 0.64 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 4082 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.74 | 0.89 | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 5156 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Bc | 0.64 | 0.47 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 5542 | ThVp-1a | hg | 0.82 | n/a | light red | – | easy | |

| 5795 | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.77 | 0.43 | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1416-bo | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.42 | 0.15 | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1416-o | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.84 | 0.92 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 150-b | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.75 | 0.63 | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 150-k | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.41 | 0.2 | light red | red | small awns | easy |

| 1665-o | ThVp-1c | hg | 0.75 | 0.65 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 1665-h | ThVp-1c | hz | 0.67 | n/a | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1765-b | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.71 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1765-k | ThVp-1d | Vp-1Ba | 0.15 | 0.02 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1795-so | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.69 | n/a | dark red | white | + | easy |

| 1795-slo | hg | Vp-1Ba | 0.66 | 0.47 | dark red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1804-b | ThVp-1a | hz | 0.87 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1804-k | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.82 | 0.43 | light red | red | – | easy |

| 1807-o | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.81 | 0.57 | light red | white | + | easy |

| 1807-h | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Ba | 0.85 | n/a | light red | white | small awns | easy |

| 1861-bo | ThVp-1a | hz | 0.82 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| 1865-bkbk | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.94 | n/a | dark red | white | – | easy |

| 1865-bkk | ThVp-1c | Vp-1Bc | 0.97 | n/a | dark red | red | – | easy |

| 1870-bo | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.80 | n/a | light red | white | – | easy |

| ZP26 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.86 | 0.60 | light red | white | – | easy |

| M169 | ThVp-1b | Vp-1Bc | 0.70 | 0.44 | light red | white | – | easy |

| M3202 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Ba | 0.84 | 0.65 | light red | white | – | easy |

| Otrastayushchaya 38 | ThVp-1a | Vp-1Bc | 0.79 | 0.45 | light red | white | small awns | easy |

GI—germination index.

SS–spike sprouting.

hz–heterozygote.

hg–heterogeneous entry.

n/a–not available.

*—SS was assessed in 74 out of 87 entries due to the lack of plant material.

Assay of germination index (GI) and spike sprouting (SS)

The entries were grown in the fields of the Department of Distant Hybridization (Tsitsin Main Botanical Garden, Russian Academy of Sciences) at the Snegiri settlement, Istrinsky district of Moscow region (55°51'32"N 37°1'54"E). Germination index was determined according to Walker-Simmons method [62]. The spikes were harvested at full ripeness and threshed manually. 25 seeds in four replicates were placed crease down on moist filter paper in Petri dishes, which were then placed in lit climatic chamber (12 hours day, 12 hours night) at +20°C. The number of germinated seeds was counted daily and removed after counting during 7 days. The seeds were taken as germinated at radical emergence. Water was added to Petri dishes as needed using a sprayer. The remaining seeds were left to germinate for one month to determine their viability. Seeds that did not sprout within a month were excluded from further calculations. The germination index (GI) was calculated according to the formula:

where TG were total grains, n1, n2,… n7 were the numbers of seeds germinated on the first, second, and subsequent days until the seventh day.

Spike sprouting assay (SS) of the wheat-wheatgrass entries was conducted in moist chamber on the shelves wrapped in plastic film. The spikes were harvested at full ripeness, steeped in distilled water for an hour, five spikes per each entry were bound into sheaves and placed on the shelves in an upright position. The sheaves were placed into a chamber and sprayed three times a day for 5 minutes each time. Visual counting of clearly sprouted grains was performed at the third day of sprouting provocation. Then, the spikes were dried and threshed to determine the total number of grains in them. The SS value was calculated as a ratio of sprouted grains to the total number of grains.

In addition, the spike morphology was estimated–presence of awns, glume color, grain color, and threshability.

DNA extraction and molecular markers

The DNA of the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids was extracted from seedlings using CTAB protocol [63].

The PCR analysis was performed using markers Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip for the wheatgrass ThVp-1 genes and Vp-1B3 for the wheat TaVp-1B gene.

The primers Vp1BB4 were developed by Yang et al. (2007) [28] (Vp-1BB4F: 5ʹ-CAATGAGCTGCAGGAGGGTGA-3ʹ, Vp-1BB4R: 5ʹ-ATCATCCCTAACTAGGGCTACG-3ʹ) and converted by us into the CAPS marker Vp1BB4_HaeIII [60]. The conditions for PCR amplification were 94○C for 1 min; followed by 35 cycles of 95○C for 1 min; 64○C for 1 min; 72○C for 1 min, with a final extension of 72○C for 10 min. The PCR products were digested using the HaeIII endonuclease for 12 h at 37○C.

The STS marker Vivip was designed by Kocheshkova et al. (2014) [61] (VivipF: 5ʹ- GGGTGATTTCATCGTGCTT-3ʹ, VivipR: 5ʹ-TCTCCAACACTTGATTTTGACC-3ʹ). The conditions for PCR amplification were 95°C for 7 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, with the final extension of 72°C for 10 min.

The primers and conditions for PCR amplification of Vp-1B3 are described in Yang et al. (2007) [28].

The PCR fragments were separated on 2% agarose gel with TBE buffer at 6 V/cm field strength with GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a size marker, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized using UV light.

Statistical analysis

The grouping of the data was carried out using Sturges’ rule [64, 65]. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed in the ‘Statistica 6.0’ program. The differences in GI and SS among genotypes with different PCR profiles were tested using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test as in Chang et al. (2010 a,b) [57, 66].

Results

PHS resistance is determined by two groups of traits: spike morphology (presence of awns, glume adherence, spike inclination, etc.) and grain characteristics (color, germination inhibitors in seed coat, hormonal status, etc.) [15, 16, 62, 67–71]. The effect of the first group can be reflected by evaluating spike sprouting (SS) in intact spikes in moist chamber, and the second group by germination index (GI) of the threshed grains in Petri dishes.

Spike sprouting assay (SS)

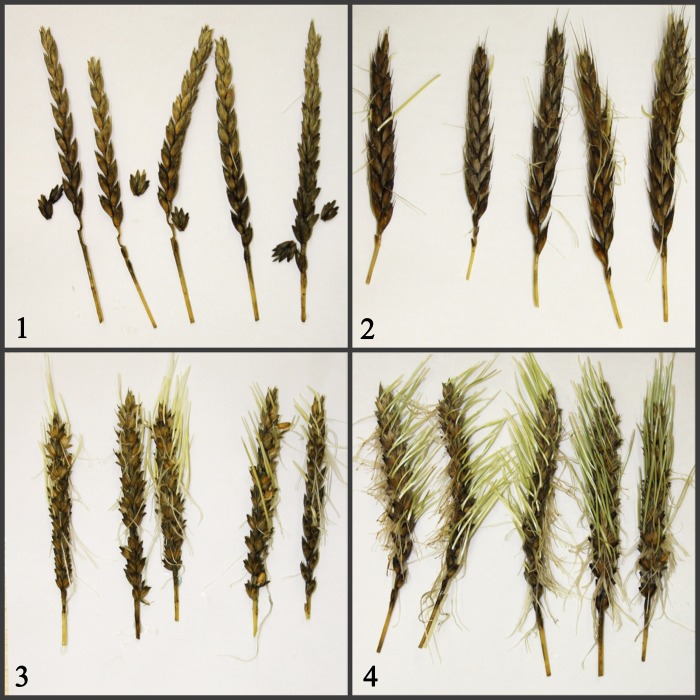

For a set of 74 entries spike sprouting (SS) was estimated (Fig 1, Table 1). The proportion of germinated seeds was determined visually on the third day of spikes wetting.

Fig 1. Estimation of the PHS resistance by spike sprouting assay.

1–1451; 2–150-k; 3–1626; 4–4044.

Using the Sturges’ rule, a set of 74 entries was divided into 8 clusters with the corresponding SS ranges. The most resistant entries sorted to cluster 1 were 1451, 1654, 1780, 1765-k, 1533, 1748, 1735, 1745, 1874, 1744, 1774 (Table 2).

Table 2. Classification of the wheat-wheatgrass collection entries based on the results of the SS assay.

| Cluster | Range of SS | Number of entries | Wheat-wheatgrass entries |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,01–0,12 | 11 | 1451, 1654, 1780, 1765-k, 1533, 1748, 1735, 1745, 1874, 1744, 1774 |

| 2 | 0,13–0,24 | 2 | 1416-bo, 150-k |

| 3 | 0,25–0,36 | 6 | 1876, 1777, 1869, 166, 1783, 1382 |

| 4 | 0,37–0,48 | 19 | 1646, 1626, 2087, 1375, 1804-k, 5795, 1674, 1689, 3215, M169, 1755, 1878, 243, Otrastayushchaya 38, 1868, 1795-slo, 5156, 1737, 33 |

| 5 | 0,49–0,60 | 17 | 1512, 1514, 237, 168, 1877, 49, 186, 1866, 1546, 3240, 192, 12, 1807-o, 1770, 90, 4023, ZP26 |

| 6 | 0,61–0,72 | 11 | 249, 1692, 150-b, 4015, 4061, 1665-o, 1805, 1690, M3202, 548, 1872 |

| 7 | 0,73–0,84 | 2 | 1772, 1784 |

| 8 | 0,85–0,97 | 6 | 1803, 4044, 1792, 4056, 4082, 1416-o |

Germination index (GI)

For a set 87 entries the germination index (GI) was evaluated. Using the Sturges’ rule, the set was divided into 8 clusters with the corresponding GI ranges (Table 3).

Table 3. Classification of wheat-wheatgrass entries by germination index (GI).

| Cluster | Range of GI | Number of entries | Wheat-wheatgrass entries |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0,15–0,25 | 1 | 1765-k |

| 2 | 0,26–0,35 | 0 | — |

| 3 | 0,36–0,46 | 4 | 150-k, 1416-bo, 1735, 1774 |

| 4 | 0,47–0,56 | 2 | 1876, 1533 |

| 5 | 0,57–0,67 | 11 | 1777, 1692, 1780, 1745, 1737, 1654, 168, 5156, 1512, 1795-slo, 1665-h |

| 6 | 0,68–0,78 | 27 | 243, 1878, 4015, 12, 1795-so, M169, 166, 1783, 1765-b, 1748, 1744, 2087, 1689, 249, 1866, 90, 4056, 4082, 150-b, 1665-o, 548, 1626, 5795, 1546, 1375, 1674, 1690 |

| 7 | 0,79–0,88 | 24 | Otrastayushchaya 38, 3240, 4023, 1870-bo, 49, 1877, 1807-o, 1804-k, 5542, 1861-bo, 4061, M3202, 1416-o, 3215, 1868, 186, 1807-h, 1874, 1382, ZP26, 1451, 1869, 1842, 1804-b |

| 8 | 0,89–0,99 | 18 | 237, 1646, 1755, 192, 1761, 1805, 1792, 1788, 33, 1772, 1865-bkbk, 1514, 1784, 1803, 1865-bkk, 4044, 1770, 1872 |

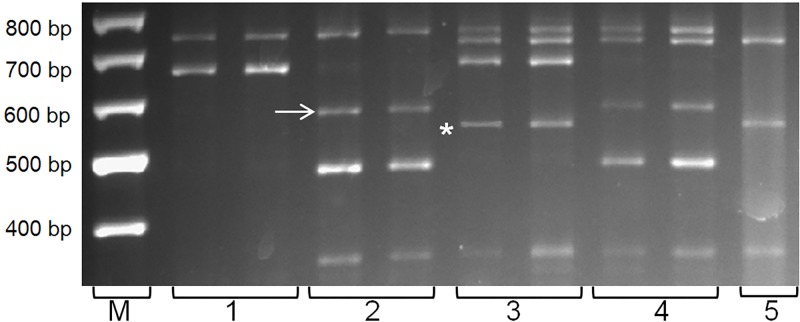

The entries of different clusters are characterized by different dynamics of germination (Fig 2). The immediate germination of the majority of grains on the 1st day is represented by 1761 (cluster 8). ZP26 (cluster 7) and 4082 (cluster 6) showed the peak on the 2nd day, 1777 (cluster 5) and 1876 (cluster 4) on the 3rd day, 1735 (cluster 3) on the 5th day. Extended dynamics of germination is intrinsic for 1765-k, the most PHS resistant entry. Therefore, the lower GI value, the more delayed and faint peak of germination can be observed.

Fig 2. Example of dynamics of grain germination of various wheat-wheatgrass entries in Petri dishes.

Entry 1451 showed both minimum SS value (0.01) and a high GI value (0.87). As 1451 is extremely hard to thresh and has rigid glumes adherent to the caryopsis, its high PHS resistance in the spike is determined primarily by the spike architecture, and the seeds themselves have a low dormancy level. The spike architecture, apparently, also explains PHS resistance in 1748 and 1874 (SS 0.07 and 0.09), which possess low seed dormancy (GI 0.72 and 0.86). 1765-k has low SS (0.02) and low GI (0.15), hence its PHS resistance can be explained equally by the seed and spike characteristics. 1735, 1774 and 150-k showed high resistance in the SS and GI assays, which allows us to consider them as generally resistant to PHS. 4044, 1416-o, 1792, 1803 showed high SS and GI, and thus can be considered as susceptible to PHS. Therefore, the spike features of these entries are unable to provide PHS resistance and to compensate for the low seed dormancy. The entries with low GI and high SS were not revealed (Table 4). That indicates that a high level of seed dormancy is enough for providing acceptable PHS resistance.

Table 4. Classification of entries based on the results of germination index (GI) and spike sprouting (SS) assays.

| Low GI | High GI | |

|---|---|---|

| Low SS | 1765-k, 1735, 1744, 150-k. | 1451, 1748, 1874 |

| High SS | Not found | 4044, 1416-o, 1792, 1803 |

Distribution of wheatgrass ThVp-1 haplotypes

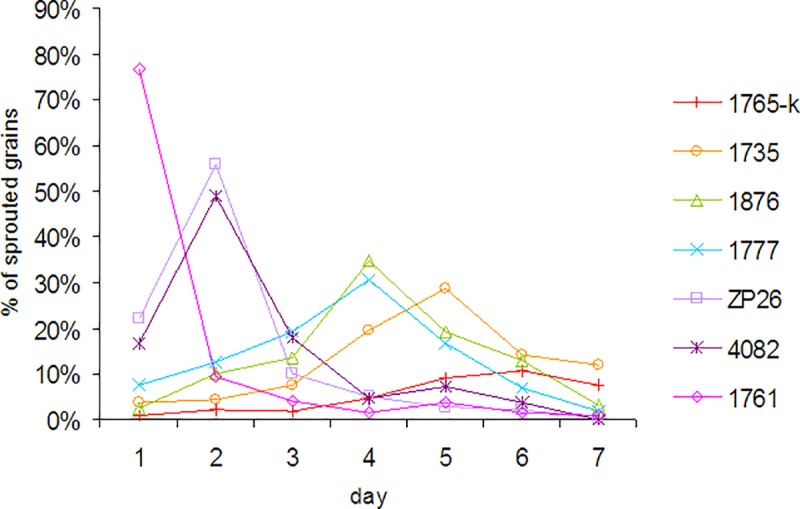

Markers Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip allow the identification of various alleles of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 gene in a wheat background [60, 61]. The DNA fragments of Vp1BB4_HaeIII produced by PCR and subsequent restriction endonuclease digestion were analyzed in all entries. Vp1BB4_HaeIII enables the identification of additional fragments different from wheat after restriction of the PCR product. Such additional bands were interpreted as fragments amplified from ThVp-1 [60].

In our study, the analysis of 87 entries using Vp1BB4_HaeIII revealed two sizes of additional fragments of ThVp-1, namely, approximately 600 bp and approximately 550 bp (Fig 3, Table 5). Consequently, Vp1BB4_HaeIII can distinguish three possible ThVp-1 states: presence of the ~600 bp fragment, presence of the ~550 bp fragment and absence of both fragments. No entry with simultaneous presence of both the ~550 and ~600 bp fragments was found.

Fig 3. Electrophoresis of the CAPS-marker Vp1BB4_HaeIII fragments.

The ~600 bp (arrow) and ~550 bp (*) are diagnostic fragments for the wheatgrass ThVp1 gene. M—size standard (100 bp DNA Ladder), 1 –Triticum aestivum cv. Nota, 2–90, 3–150 k., 4–168, 5 –Th. intermedium PI 401200.

Table 5. The combined results of application of the Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip markers in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids.

| Wheatgrass ThVp-1 haplotypes | Marker results | Wheat-wheatgrass entries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vp1BB4_HaeIII | Vivip | ||

| ThVp-1a | No specific fragments | No specific fragments | 49, 150-b, 166, 186, 192, 1382, 1416-bo, 1416-o, 1533, 1646, 1689, 1690, 1737, 1744, 1748, 1755, 1761, 1777, 1783, 1788, 1795-so, 1804-b, 1804-k, 1842, 1861-bo, 1866, 1870-bo, 1874, 1877, 1878, 4044, 4082, 5542, ZP26, M3202, Otrastayushchaya 38 |

| ThVp-1b | ~600 bp | No specific fragments | 90, 168, 1512, 1674, 1692, 1770, 2087, 4015, 4023, 4061, M169 |

| ThVp-1c | ~550 bp | ~370 bp | 33, 150-k, 237, 243, 249, 1451, 1546, 1654, 1665-h, 1665-o, 1772, 1774, 1784, 1792, 1803, 1805, 1807-o, 1807-h, 1865bkbk, 1865-bkk, 1868, 1869, 1872, 3215, 3240 |

| ThVp-1d | No specific fragments | ~350 bp | 12, 548, 1375, 1514, 1626, 1735, 1745, 1765-k, 1765-b, 1780, 1876, 5156, 5795 |

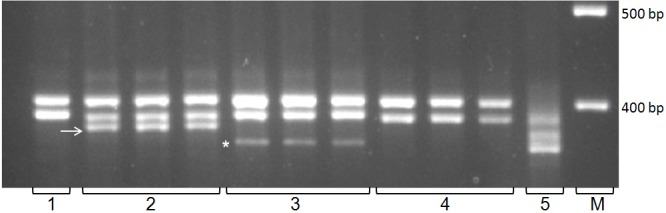

The Vivip marker was designed based on sequences of another polymorphic regions of the orthologous Vp-1 genes of Th. intermedium, Th. ponticum, Th. bessarabicum, and P. spicata. The results of the identification of the ThVp-1 polymorphism using Vivip are independent from Vp1BB4_HaeIII [61]. In our study, the PCR analysis of 87 entries using Vivip allowed the identification of two additional amplified DNA fragments of wheatgrass origin, namely, approximately 350 bp, and approximately 370 bp (Fig 4). In the studied collection of the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids three possible states of Vivip were revealed: absence of both fragments, presence of the ~350 bp fragment, and presence of the ~370 bp fragment (Fig 4, Table 5).

Fig 4. An example of electrophoresis of PCR products of the STS marker Vivip.

The DNA fragments indicating the presence of wheatgrass ThVp-1 are ~350 bp and ~370 bp. 1 –Triticum aestivum cv. Nota; 2–1665, 3–5156, 4 –ZP26, 5 –Th. intermedium PI 401200, M–size standard, 100 bp DNA Ladder.

The analysis of the results of two molecular markers have revealed that the 370 bp fragment detected by Vivip occurs in the same wheat-wheatgrass entries as the 550 bp fragment, which is detected by Vp1BB4_HaeIII. Thus, fragments ~550 bp of Vp1BB4_HaeIII and ~370 bp of Vivip detect the same allele of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 gene.

1795-slo and 4056 showed heterogeneity for the allelic state of ThVp-1, so, they were excluded from the further statistical analysis.

The analysis of 87 entries using both markers Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip showed four possible haplotypes of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 gene that are present in the studied wheat-wheatgrass hybrids (Table 5). These four variants are characterized by the molecular markers, as follows: 1) Absence of the specific wheatgrass DNA fragments of both markers (designated ThVp-1a, 36 entries); 2) Presence of the ~600 bp fragment detected by Vp1BB4_HaeIII and absence of specific fragments of Vivip (desisgnated ThVp-1b, 11 entries); 3) Presence of the ~550 bp fragment of Vp1BB4_HaeIII and presence of the ~370 bp fragment Vivip (desisgnated ThVp-1c, 25 entries); 4) Absence of specific fragments for Vp1BB4_HaeIII and presence of the ~350 bp fragment revealed by Vivip (desisgnated ThVp-1d, 13 entries).

Thus, we have identified a polymorphism of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 gene in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection and they were grouped into 4 classes (haplotypes) depending on the results of the combined use of Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip. The distribution of haplotypes in the collection is as follows: the predominant haplotype is ThVp-1a (41%), second place is allele ThVp-1c (29%), followed by haplotypes ThVp-1d (15%) and ThVp-1b (13%).

The association between ThVp-1 haplotypes and PHS resistance based on GI in the entire germplasm collection was evaluated statistically using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Table 6).

Table 6. Association between ThVp-1 haplotypes and GI values in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection.

| ThVp-1 haplotype | Number of entries | Mean GI* | Standard deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThVp-1a | 36 | 0.78b | 0.12 | 0.42–0.98 |

| ThVp-1b | 11 | 0.74ab | 0.11 | 0.60–0.99 |

| ThVp-1c | 25 | 0.82b | 0.15 | 0.41–0.99 |

| ThVp-1d | 13 | 0.64a | 0.20 | 0.15–0.95 |

* Fobserved = 4.635 > Fcritical = 2.717; p = 0.0048.

Different letters in this column indicate significant differences (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) among different ThVp-1 haplotypes

The ANOVA indicated significant GI differences between the groups of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids with various ThVp-1 haplotypes. Statistically significant differences were observed between haplotypes ‘a’ and ‘d’ and between haplotypes ‘c’ and ‘d’. Thus, entries with the ThVp-1d haplotype had significantly lower average GI than ThVp-1a and ThVp-1c genotypes confirming the association of ThVp-1 and seed dormancy.

The ANOVA conducted after arcsin√x transformation of the SS values and Fisher’s F-test revealed no significant differences between the groups of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids with different ThVp-1 haplotypes. However, LSD test showed that the group of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids with ThVp-1d haplotype gave lower value of SS than groups with haplotypes ‘b’ and ‘c’ (Table 7).

Table 7. Association between ThVp-1 haplotypes and SS values in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection.

| ThVp-1 haplotype | Number of entries | Mean SS arcsin√x transformed* | Mean SS reverse transformed | Standard deviation (for arcsin√x transformed means) | Range (non- transformed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThVp-1a | 28 | 0.73ab | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.04–0.92 |

| ThVp-1b | 11 | 0.83b | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.41–0.64 |

| ThVp-1c | 21 | 0.77b | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.01–0.89 |

| ThVp-1d | 12 | 0.57a | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.01–0.66 |

* Fobserved = 2.13 < Fcritical = 2.74; p = 0.104.

Different letters in this column indicate significant differences (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) among different ThVp-1 haplotypes

Distribution of wheat TaVp-1 haplotypes

As wheat-wheatgrass hybrids combine wheat and wheatgrass genomes, our collection was also evaluated for the allelic state of the wheat TaVp-1 gene using the STS marker developed by Yang et al. (2007) [28] (Table 1). The structure of the studied germplasm collection was as follows: 51% of the entries carried allele TaVp-1Ba, 31% carried allele TaVp-1Bc, 15% showed heterogeneity, 3% were heterozygotes (the latter two groups were not involved in the statistical analysis).

The GI differences between groups of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids with different allelic state of wheat TaVp-1B were not significant with similar mean GI values (Table 8).

Table 8. Association between TaVp-1B alleles (of wheat origin) and GI values in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection.

| Allele of wheat Vp-1B | Number of entries | Mean GI* | Standard deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vp-1Bc | 27 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.41–0.97 |

| Vp-1Ba | 44 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.15–0.99 |

* Fobserved = 0.003 < Fcritical = 3,982; p = 0.959

No significant differences of SS between groups of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids with different TaVp-1B alleles were revealed (Table 9).

Table 9. Association between TaVp-1B alleles (of wheat origin) and SS values in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection.

| Allele of wheat Vp-1B |

Number of entries | Mean SS arcsin√x transformed | Mean SS reverse transformed* | Standard deviation (for arcsin√x transformed means) |

Range (non- transformed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vp-1Bc | 23 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.01–0.92 |

| Vp-1Ba | 40 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.01–0.89 |

* Fobserved = 0.21376 < Fcritical = 1.74; p = 0.64519

In addition, no statistically significant association was revealed between PHS resistance measured by SS and GI and the presence of awns, glumes color, and grain color (data not shown).

Discussion

In our work for the first time, the PHS resistance polymorphism in wheat-wheatgrass hybrids was revealed by GI and SS evaluation. In our study, the wheat-wheatgrass hybrids significantly differ from each other in PHS resistance. Similarly, wheat-wheatgrass hybrids are also highly polymorphic in other traits such as diseases resistance, grain yield, post-harvest regrowth ability, forage biomass [4, 5, 72–74]. Among the resistant entries with low GI we identified two types of germination dynamics, namely, an extended germination and delayed peak. In general, the majority of the entries were susceptible to PHS (92% are susceptible to PHS, classes 5–8, Table 3). It may be a serious problem for the introduction of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids as a cereal crop in regions where climate favors PHS. Currently, the main attempts to develop perennial wheat-wheatgrass hybrids as a crop are being made in Australia [4, 5, 72], where PHS is not a relevant problem and probably that is why it receives little attention.

PHS resistance in grasses is controlled by multiple factors. QTLs for PHS resistance have been found on all chromosomes of wheat in different studies [23, 29, 34–36, 75–90]. Many studies of the PHS resistance in wheat is focused on TaVp-1, the polymorphism of its haplotypes and its effect on PHS [28, 57–59, 66, 91–94]. In the majority of them the influence of different alleles of TaVp-1B and TaVp-1A was shown primarily in white-grained wheat, though in some studies the effect of TaVp-1 was found in red-grained wheat and triticale as well [59, 93]. Given the fact that all wheat-wheatgrass entries possess red or blue grain, which is usually associated with resistance, the absence of resistance in the majority of entries is apparently a result of the negative impact of the wheatgrass genome. For example, a negative effect of chromosome 6Agi of intermediate wheatgrass on PHS resistance was revealed in the studies of the recombinant inbred substitution lines of wheat [21]. This should be considered in breeding and development of cultivation technology of commercial wheat-wheatgrass cultivars. In addition, one should note, that the proportion of entries demonstrating resistance to sprouting in intact spikes is higher than the proportion of entries demonstrating seed dormancy in the evaluation of GI. Apparently, this is due to the spike architecture of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids. Spikes of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids are generally more dense and hard to thresh in comparison to bread wheat. Four entries (237, 1375, 1654, 1451) differ from others by rough glumes, which adhere very closely to the grain. This feature significantly hardens the process of threshing, and, on the other hand, contributes to the delay of water uptake [40, 95].

Apparently, the variability of PHS resistance of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids in our case is mainly due to diversity in the wheatgrass genetic component. We found only two alleles of wheat TaVp-1, namely TaVp-1Bc and TaVp-1Ba, the most common for different wheat cultivars [28, 57–59, 66, 91–94]. We did not reveal any significant differences in PHS resistance between wheat-wheatgrass entries with wheat gene alleles TaVp-1Bc and TaVp-1Ba. As relatively few wheat cultivars were used for the development of the studied wheat-wheatgrass entries, we can hardly expect a wide genetic variability of wheat genes controlling PHS in a wheat-wheatgrass hybrid genome [6, 96]. On the other hand, the probability of high polymorphism of wheatgrass genes affecting PHS in different wheat-wheatgrass hybrids is strong, because most of the partial amphiploids carry a synthetic mixed extra genome which has a different combination of chromosomes each time a partial amphiploid is produced [1–5].

Wheat-wheatgrass hybrids carry individual composition of wheatgrass chromosomes, inherited from Th. intermedium and/or Th. ponticum and derived from different subgenomes [1–5]. We may suggest that the recombination between different homeological chromosomes of wheatgrass in the genome of a wheat-wheatgrass hybrid is a rare event. Despite the PCR-based markers Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip applied in our study were developed on the basis of the Vivparous-1 sequence, we may have estimated not only the effect of ThVp-1 but also the effect of the linkage group 3 of Thinopyrum in the present study. The role of Thinopyrum chromosomes 3 may be similar to chromosomes 3 of wheat that harbor the majority of QTLs associated with PHS resistance [34–38, 75], transcriptional factor TaVp-1 [28, 57–59, 66, 91–94], TaMyb10 responsible for seed color [27] and epigenetic factors of DNA methylation AGO802 [46]. PHS resistance can also be regulated not only by polymorphism in DNA sequence but also by epigenetic factors through DNA and histone methylation [46, 47] that have not been studied in wide hybrids yet and can have its own specificity. As PHS resistance is a complex trait regulated by multiple factors molecular makers Vp1BB4_HaeIII and Vivip cannot be used as the only diagnostic tool in marker-assisted selection of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids or perennial wheat. However, they can be efficiently applied in breeding process after additional exploration and validation in complex with other molecular and phenotypic estimation methods to select PHS resistant wheat-wheatgrass entries and perennial wheat.

We have shown that the studied entries are diverse in wheatgrass component and that this diversity is associated with PHS resistance. The differences in PHS resistance between wheat-wheatgrass hybrids can be explained by genetic variations and/or epigenetic modifications. Genetic variations may represent variations in different levels: different combinations of wheatgrass chromosomes (the genome level), differences in the chromosomes of the homeologous group 3, where genes Vp-1 and R are localized (the chromosome level) or structural and functional differences in the Vp-1 genes (the gene level). Along with that, we have shown that the greatest resistance to PHS is innate to the entries of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids bearing haplotype ThVp-1d of the wheatgrass Vp-1 gene (mean SS is 0.33, and mean GI is 0.64).

Conclusion

We, for the first time, demonstrated the variability of wheat-wheatgrass hybrids in resistance to PHS. Most entries showed susceptibility that may pose a serious problem in wheat-wheatgrass hybrid either as a source of genetic variability in wheat breeding or as a crop in regions with conditions favorable to PHS. Interestingly, although all estimated entries have red grain associated with high seed dormancy, only few showed relatively low GI. Using PCR-based markers we demonstrated the polymorphism of the haplotypes of the wheatgrass ThVp-1 gene in the wheat-wheatgrass hybrid collection and have revealed the significant effect of the ThVp-1 gene on the PHS resistance. The further study may help to shed the light on the role of ThVp-1 gene and its interaction with TaVp-1 in regulation of seed dormancy.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

Financial support from the Russian Science Foundation, Russia, Project Number 16-16-00097 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Banks PM, Xu SJ, Wang RR, Larkin PJ. Varying chromosome composition of 56-chromosome wheat x Thinopyrum intermedium partial amphiploids. Genome. 1993. April;36(2):207–15. doi: 10.1139/g93-029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fedak G, Han F. Characterization of derivatives from wheat-Thinopyrum wide crosses. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;109(1–3):360–7. doi: 10.1159/000082420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroupin PY, Divashuk MG, Belov VI, Glukhova LI, Aleksandrov OS, Karlov GI. Comparative molecular cytogenetic characterization of partial wheat-wheatgrass hybrids. Russ J Genet. 2011. April;47(4):432–7. doi: 10.1134/S1022795411040077 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes RC, Newell MT, DeHaan LR, Murphy KM, Crane S, Norton MR, et al. Perennial cereal crops: An initial evaluation of wheat derivatives. Field Crops Res. 2012. July 11;133:68–89. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.03.014 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin PJ, Newell MT, Hayes RC, Aktar J, Norton MR, Moroni SJ, et al. Progress in developing perennial wheats for grain and grazing. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014. November 20;65(11):1147–64. doi: 10.1071/CP13330 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsitsin N V. Mnogoletnyaya pshenitsa. Moscow: Nauka; 1987. (In Russian).

- 7.Gazza L, Galassi E, Ciccoritti R, Cacciatori P, Pogna NE. Qualitative traits of perennial wheat lines derived from different Thinopyrum species. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2016. February;63(2):209–19. doi: 10.1007/s10722-015-0240-8 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marquardt K, Vico G, Glynn C, Weih M, Eksvärd K, Dalin P, et al. Farmer perspectives on introducing perennial cereal in Swedish farming systems: a sustainability analysis of plant traits, farm management, and ecological implications. Agroecol Sust food. 2016. May 27;40(5):432–50. doi: 10.1080/21683565.2016.1141146 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd S. Perennial wheat [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Mar 31]. Available from: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se/7778/

- 10.Adebiyi J, Olabisi LS, Snapp S. Understanding perennial wheat adoption as a transformative technology: evidence from the literature and farmers. Renew Agr Food Syst. 2016. April;31(2):101–10. doi: 10.1017/S1742170515000150 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner MK, DeHaan LR, Jin Y, Anderson JA. Wheatgrass–wheat partial amphiploids as a novel source of stem rust and Fusarium head blight resistance. Crop Sci. 2013. September;53(5):1994–2005. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2012.10.0584 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruppa K, Molnár-Láng M. Simultaneous visualization of different genomes (J, JSt and St) in a Thinopyrum intermedium × Thinopyrum ponticum synthetic hybrid (Poaceae) and in its parental species by multicolour genomic in situ hybridization (mcGISH). Comp Cytogenet. 2016. June 17;10(2):283–93. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i2.7305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Wang X. Thinopyrum ponticum and Th. intermedium: the promising source of resistance to fungal and viral diseases of wheat. J Genet Genomics. 2009. September;36(9):557–65. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60147-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salina EA, Adonina IG, Badaeva ED, Kroupin PY, Stasyuk AI, Leonova IN, et al. A Thinopyrum intermedium chromosome in bread wheat cultivars as a source of genes conferring resistance to fungal diseases. Euphytica. 2015. July;204(1):91–101. doi: 10.1007/s10681-014-1344-5 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin M, Zhang D, Liu S, Zhang G, Yu J, Fritz AK, et al. Genome-wide association analysis on pre-harvest sprouting resistance and grain color in U.S. winter wheat. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:794 doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3148-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Wang XL, Meng JY, Zhang YJ, He ZH, Yang Y. Characterization of Tamyb10 allelic variants and development of STS marker for pre-harvest sprouting resistance in Chinese bread wheat. Mol Breed. 2016;36(11). doi: 10.1007/s11032-016-0573-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shorinola O, Bird N, Simmonds J, Berry S, Henriksson T, Jack P, et al. The wheat Phs-A1 pre-harvest sprouting resistance locus delays the rate of seed dormancy loss and maps 0.3 cM distal to the PM19 genes in UK germplasm. J Exp Bot. 2016. July;67(14):4169–78. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gale MD, Lenton JR. Pre-harvest sprouting in wheat: a complex genetic and physiological problem affecting breadmaking quality in UK wheat. Asp Appl Biol. 1987;15:115–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphreys DG, Noll J. Methods for characterization of preharvest sprouting resistance in a wheat breeding program. Euphytica. 2002. July;126(1):61–5. doi: 10.1023/A:1019671622356 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imtiaz M, Ogbonnaya FC, Oman J, van Ginkel M. Characterization of quantitative trait loci controlling genetic variation for preharvest sprouting in synthetic backcross-derived wheat lines. Genetics. 2008. March;178(3):1725–36. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krupnov VA, Antonov GY, Druzhin AE, Krupnova OV. Preharvesting sprouting resistance of spring bread wheat carrying the 6Agi(6D) chromosome from Agropyron intermedium. Russ J Genet Appl Res. 2012. November;2(6):467–72. doi: 10.1134/S2079059712060093 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Miao X, Xia X, He Z. Cloning of seed dormancy genes (TaSdr) associated with tolerance to pre-harvest sprouting in common wheat and development of a functional marker. Theor Appl Genet. 2014. April;127(4):855–66. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2262-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flintham JE. Different genetic components control coat-imposed and embryo-imposed dormancy in wheat. Seed Sci Res. 2000. March;10(1):43–50. doi: 10.1017/S0960258500000052 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warner RL, Kudrna DA, Spaeth SC, Jones SS. Dormancy in white-grain mutants of Chinese Spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Seed Sci Res. 2000. March;10(1):51–60. doi: 10.1017/S0960258500000064 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himi E, Mares DJ, Yanagisawa A, Noda K. Effect of grain colour gene (R) on grain dormancy and sensitivity of the embryo to abscisic acid (ABA) in wheat. J Exp Bot. 2002. July;53(374):1569–74. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park H, Kreunen SS, Cuttriss AJ, DellaPenna D, Pogson BJ. Identification of the carotenoid isomerase provides insight into carotenoid biosynthesis, prolamellar body formation, and photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2002. January 2;14(2):321–32. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Himi E, Noda K. Red grain colour gene (R) of wheat is a Myb-type transcription factor. Euphytica. 2005. September;143(3):239–42. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-7854-4 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Zhao XL, Xia LQ, Chen XM, Xia XC, Yu Z, et al. Development and validation of a Viviparous-1 STS marker for pre-harvest sprouting tolerance in Chinese wheats. Theor Appl Genet. 2007. November;115(7):971–80. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0624-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan A, Kulwal P, Singh R, Kumar V, Mir RR, Kumar J, et al. Genome-wide QTL analysis for pre-harvest sprouting tolerance in bread wheat. Euphytica. 2009. August;168(3):319–29. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-9935-2 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabral AL, Jordan MC, McCartney CA, You FM, Humphreys DG, MacLachlan R, et al. Identification of candidate genes, regions and markers for pre-harvest sprouting resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2014. November 29;14:340 doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0340-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao L, Hayashi K, Tokui M, Mori M, Miura H, Onishi K. Detection of QTLs for traits associated with pre-harvest sprouting resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Breed Sci. 2016. March;66(2):260–70. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.66.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fakthongphan J, Graybosch RA, Baenziger PS. Combining ability for tolerance to pre-harvest sprouting in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Crop Sci. 2016. May;56(3):1025–35. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2015.08.0490 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato K, Nakamura W, Tabiki T, Miura H, Sawada S. Detection of loci controlling seed dormancy on group 4 chromosomes of wheat and comparative mapping with rice and barley genomes. Theor Appl Genet. 2001. May;102(6–7):980–5. doi: 10.1007/s001220000494 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osa M, Kato K, Mori M, Shindo C, Torada A, Miura H. Mapping QTLs for seed dormancy and the Vp1 homologue on chromosome 3A in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2003. May;106(8):1491–6. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1208-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulwal PL, Kumar N, Gaur A, Khurana P, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK, et al. Mapping of a major QTL for pre-harvest sprouting tolerance on chromosome 3A in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2005. October;111(6):1052–9. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0021-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori M, Uchino N, Chono M, Kato K, Miura H. Mapping QTLs for grain dormancy on wheat chromosome 3A and the group 4 chromosomes, and their combined effect. Theor Appl Genet. 2005. May;110(7):1315–23. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1972-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Bai G. Dissection and fine mapping of a major QTL for preharvest sprouting resistance in white wheat Rio Blanco. Theor Appl Genet. 2010. November;121(8):1395–404. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1396-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Tang H, Cheng M-P, Dankwa KO, Chen Z-X, Li Z-Y, et al. Genome-wide association study for pre-harvest sprouting resistance in a large germplasm collection of Chinese wheat landraces. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:401 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mares D, Mrva K, Cheong J, Williams K, Watson B, Storlie E, et al. A QTL located on chromosome 4A associated with dormancy in white- and red-grained wheats of diverse origin. Theor Appl Genet. 2005. November;111(7):1357–64. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0065-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C-X, Cai S-B, Bai G-H. A major QTL controlling seed dormancy and pre-harvest sprouting resistance on chromosome 4A in a Chinese wheat landrace. Mol Breed. 2008. April;21(3):351–8. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9135-5 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh R, Matus-Cádiz M, Båga M, Hucl P, Chibbar RN. Identification of genomic regions associated with seed dormancy in white-grained wheat. Euphytica. 2010. August;174(3):391–408. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0137-8 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S, Sehgal SK, Li J, Lin M, Trick HN, Yu J, et al. Cloning and characterization of a critical regulator for preharvest sprouting in wheat. Genetics. 2013. September;195(1):263–73. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shorinola O, Balcárková B, Hyles J, Tibbits JFG, Hayden MJ, Holušova K, et al. Haplotype analysis of the pre-harvest sprouting resistance locus Phs-A1 reveals a causal role of TaMKK3-A in global germplasm. Front Plant Sci. 2017. September 13;8:1555 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng J, Chen F, Wang Z, Cao H, Li X, Deng X, et al. A novel role for histone methyltransferase KYP/SUVH4 in the control of Arabidopsis primary seed dormancy. New Phytol. 2012. February;193(3):605–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Koornneef M, Soppe WJJ. The absence of histone H2B monoubiquitination in the Arabidopsis hub1 (rdo4) mutant reveals a role for chromatin remodeling in seed dormancy. Plant Cell. 2007. February;19(2):433–44. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh M, Singh S, Randhawa H, Singh J. Polymorphic homoeolog of key gene of RdDM pathway, ARGONAUTE4_9 class is associated with pre-harvest sprouting in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh M, Singh J. Seed development-related expression of ARGONAUTE4_9 class of genes in barley: possible role in seed dormancy. Euphytica. 2012. November;188(1):123–9. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0624-1 [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarty DR, Hattori T, Carson CB, Vasil V, Lazar M, Vasil IK. The Viviparous-1 developmental gene of maize encodes a novel transcriptional activator. Cell. 1991. September 6;66(5):895–905. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90436-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nambara E, Keith K, McCourt P, Naito S. Isolation of an internal deletion mutant of the Arabidopsis thaliana ABI3 gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994. January;35(3):509–13. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones HD, Peters NC, Holdsworth MJ. Genotype and environment interact to control dormancy and differential expression of the VIVIPAROUS 1 homologue in embryos of Avena fatua. Plant J. 1997. October;12(4):911–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12040911.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bailey PC, McKibbin RS, Lenton JR, Holdsworth MJ, Flintham JE, Gale MD. Genetic map locations for orthologous Vp1 genes in wheat and rice. Theor Appl Genet. 1999. February;98(2):281–4. doi: 10.1007/s001220051069 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y-W, Nie L-N, Ma Y-Z, Xiu Z, Xia L-Q. Cloning and functional analysis of Viviparous-1 promoter in wheat. Acta Agron Sin. 2011;37(10):1743–51. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2011.01743 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura S, Toyama T. Isolation of a VP1 homologue from wheat and analysis of its expression in embryos of dormant and non-dormant cultivars. J Exp Bot. 2001. April;52(357):875–6. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.357.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKibbin RS, Wilkinson MD, Bailey PC, Flintham JE, Andrew LM, Lazzeri PA, et al. Transcripts of Vp-1 homeologues are misspliced in modern wheat and ancestral species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002. July 23;99(15):10203–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152318599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia LQ, Ganal MW, Shewry PR, He ZH, Yang Y, Röder MS. Exploiting the diversity of viviparous-1 gene associated with pre-harvest sprouting tolerance in European wheat varieties. Euphytica. 2008. February;159(3):411–7. doi: 10.1007/s10681-007-9576-2 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang Y, Chen XM, He ZH, Röder M, Xia LQ. Distribution of Vp-1 alleles in Chinese white-grained landraces, historical and current wheat cultivars. Cereal Res Comm. 2009;37(2):169–77. doi: 10.1556/CRC.37.2009.2.3 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang C, Feng JM, Si HQ, Yin B, Zhang HP, Ma CX. Validating a novel allele of viviparous-1 (Vp-1Bf) associated with high seed dormancy of Chinese wheat landrace, Wanxianbaimaizi. Mol Breed. 2010a. March;25(3):517–25. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9350-3 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang Y, Zhang CL, Liu SX, Sun YQ, Meng JY, Xia LQ. Characterization of the rich haplotypes of Viviparous-1A in Chinese wheats and development of a novel sequence-tagged site marker for pre-harvest sprouting resistance. Mol Breed. 2014. January;33(1):75–88. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9935-8 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Divashuk M, Mayer N, Kroupin P, Rubets V, Pylnev V, Lin NTT, et al. The association between the allelic state of Vp-1B and pre-harvest sprouting tolerance in red-seeded hexaploid triticale. Open J Genet. 2012. March 2;02(01):51 doi: 10.4236/ojgen.2012.21006 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Divashuk MG, Krupin PY, Fesenko IA, Belov VI, Razumova OV, Korotaeva AA, et al. About possible use of Agropyron Vp-1 (Viviparous-1) gens-homolog for improvement of soft wheat. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biologiya [Agricultural Biology]. 2011;(5):40–4. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kocheshkova AA, Divashuk MG, Kroupin PYu., Karlov GI. Development of PCR-based STS marker for identification of Viviparous-1 gene of Thinopyrum species in wheat background. Izv timiryazevskoi sel'skokhozyaistvennoi akademii. 2014; (5):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker-Simmons M. Enhancement of ABA responsiveness in wheat embryos by high temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 1988. November;11(8):769–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1988.tb01161.x [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saghai-Maroof MA, Soliman KM, Jorgensen RA, Allard RW. Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984. December;81(24):8014–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sturges HA. The choice of a class interval. J Am Stat Assoc. 1926. March;21(153):65–6. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1926.10502161 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee H-Y, Ro N-Y, Jeong H-J, Kwon J-K, Jo J, Ha Y, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis to construct a core collection from a large Capsicum germplasm. BMC Genetics. 2016. November 14;17:142 doi: 10.1186/s12863-016-0452-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang C, Zhang HP, Feng JM, Yin B, Si HQ, Ma CX. Identifying alleles of Viviparous-1B associated with pre-harvest sprouting in micro-core collections of Chinese wheat germplasm. Mol Breed. 2010b. March 1;25(3):481–90. doi: 10.1007/s11032-009-9346-z [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walker-Simmons M. ABA Levels and sensitivity in developing wheat embryos of sprouting resistant and susceptible cultivars. Plant Physiol. 1987. January 5;84(1):61–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Craig F, Paulsen M. Localization and physical properties of endogenous germination inhibitors in white wheat grain. Cereal Chem. 1988;65(5):404–8. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zanetti S, Winzeler M, Keller M, Keller B, Messmer M. Genetic analysis of pre-harvest sprouting resistance in a wheat × spelt cross. Crop Sci. 2000;40(5):1406–17. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2000.4051406x [Google Scholar]

- 70.King RW, Wettstein-Knowles P von. Epicuticular waxes and regulation of ear wetting and pre-harvest sprouting in barley and wheat. Euphytica. 2000. March;112(2):157–66. doi: 10.1023/A:1003832031695 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kato T, Saito N, Kashimura K, Shinohara M, Kurahashi T, Taniguchi K. Germination and growth inhibitors from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) husks. J Agric Food Chem. 2002. October 23;50(22):6307–12. doi: 10.1021/jf0204755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bell LW, Wade LJ, Ewing MA. Perennial wheat: a review of environmental and agronomic prospects for development in Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 2010. September 30;61(9):679–90. doi: 10.1071/CP10064 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cox TS, Tassel DLV, Cox CM, DeHaan LR. Progress in breeding perennial grains. Crop Pasture Sci. 2010. July 27;61(7):513–21. doi: 10.1071/CP09201 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murphy KM, Lyon SR, Balow KA, Jones SS. Post-sexual cycle regrowth and grain yield in Thinopyrum elongatum × Triticum aestivum amphiploids. Plant Breed. 2010. October;129(5):480–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2009.01712.x [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kato K, Nakamura W, Tabiki T, Miura H, Sawada S. Detection of loci controlling seed dormancy on group 4 chromosomes of wheat and comparative mapping with rice and barley genomes. Theor Appl Genet. 2001. May;102(6–7):980–5. doi: 10.1007/s001220000494 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flintham J, Adlam R, Bassoi M, Holdsworth M, Gale M. Mapping genes for resistance to sprouting damage in wheat. Euphytica. 2002. July;126(1):39–45. doi: 10.1023/A:1019632008244 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Groos C, Gay G, Perretant M-R, Gervais L, Bernard M, Dedryver F, et al. Study of the relationship between pre-harvest sprouting and grain color by quantitative trait loci analysis in a white×red grain bread-wheat cross. Theor Appl Genet. 2002. January;104(1):39–47. doi: 10.1007/s001220200004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lohwasser U, Röder MS, Börner A. QTL mapping of the domestication traits pre-harvest sprouting and dormancy in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica. 2005. September;143(3):247–9. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-7858-0 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kottearachchi NS, Uchino N, Kato K, Miura H. Increased grain dormancy in white-grained wheat by introgression of preharvest sprouting tolerance QTLs. Euphytica. 2006. December;152(3):421–8. doi: 10.1007/s10681-006-9231-3 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ogbonnaya FC, Imtiaz M, Ye G, Hearnden PR, Hernandez E, Eastwood RF, et al. Genetic and QTL analyses of seed dormancy and preharvest sprouting resistance in the wheat germplasm CN10955. Theor Appl Genet. 2008. May;116(7):891–902. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0712-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ren X, Lan X, Liu D, Wang J, Zheng Y. Mapping QTLs for pre-harvest sprouting tolerance on chromosome 2D in a synthetic hexaploid wheat x common wheat cross. J Appl Genet. 2008;49(4):333–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03195631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kumar A, Kumar J, Singh R, Garg T, Chhuneja P, Balyan HS, et al. QTL analysis for grain colour and pre-harvest sprouting in bread wheat. Plant Sci. 2009. August;177(2):114–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.04.004 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munkvold JD, Tanaka J, Benscher D, Sorrells ME. Mapping quantitative trait loci for preharvest sprouting resistance in white wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2009. November;119(7):1223–35. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1123-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fofana B, Humphreys DG, Rasul G, Cloutier S, Brûlé-Babel A, Woods S, et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci controlling pre-harvest sprouting resistance in a red × white seeded spring wheat cross. Euphytica. 2009. February;165(3):509–21. doi: 10.1007/s10681-008-9766-6 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mares D, Rathjen J, Mrva K, Cheong J. Genetic and environmental control of dormancy in white-grained wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica. 2009. August;168(3):311–8. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-9927-2 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chao S, Xu SS, Elias EM, Faris JD, Sorrells ME. Identification of chromosome locations of genes affecting preharvest sprouting and seed dormancy using chromosome substitution lines in tetraploid wheat (Triticum turgidum L.). Crop Sci. 2010. July;50(4):1180–7. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.10.0589 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhu Z, Tian B, Liu B, Xie Q, Tian J. Quantitative trait loci analysis for pre-harvest sprouting using intact spikes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Shandong Agric Sci. 2010;6:19–23. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang HP, Feng JM, Chang C, Ma CX, Zhang XY, Yan CS, et al. Investigation of main loci contributing to strong seed dormancy of Chinese wheat landrace. J Agric Biotech. 2011;19(2):270–7. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 89.Knox RE, Clarke FR, Clarke JM, Fox SL, DePauw RM, Singh AK. Enhancing the identification of genetic loci and transgressive segregants for preharvest sprouting resistance in a durum wheat population. Euphytica. 2012. July;186(1):193–206. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0557-0 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gao X, Hu C, Li H, Yao Y, Meng M, Dong J, et al. Factors affecting pre-harvest sprouting resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): a review. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23:556–65. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xia LQ, Yang Y, Ma YZ, Chen XM, He ZH, Röder MS, et al. What can the Viviparous-1 gene tell us about wheat pre-harvest sprouting? Euphytica. 2009. August;168(3):385–94. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-9928-1 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chang C, Zhang H-P, Zhao Q-X, Feng J-M, Si H-Q, Lu J, et al. Rich allelic variations of Viviparous-1A and their associations with seed dormancy/pre-harvest sprouting of common wheat. Euphytica. 2011. May;179(2):343–53. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0348-7 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang J, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chen Z, Dai S, Cao W, et al. Genetic variation of Vp1 in Sichuan wheat accessions and its association with pre-harvest sprouting response. Genes Genom. 2011. April;33(2):139 doi: 10.1007/s13258-010-0125-3 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sun YW, Jones HD, Yang Y, Dreisigacker S, Li SM, Chen XM, et al. Haplotype analysis of Viviparous-1 gene in CIMMYT elite bread wheat germplasm. Euphytica. 2012. July;186(1):25–43. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0482-2 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kong L, Wang F, Si J, Feng B, Li S. Water-soluble phenolic compounds in the coat control germination and peroxidase reactivation in Triticum aestivum seeds. Plant Growth Regul. 2008. December;56(3):275 doi: 10.1007/s10725-008-9307-2 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsitsin NV, Lubimova VF. New species and forms of cereals derived from hybridization between wheat and couch grass. The American Naturalist. 1959. May;93(870):181–91. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.