Abstract

Water and oxygen are ubiquitous present in ambient conditions. This work studies the unique oxygen, trace water and a volatile organic compound (VOC) acetaldehyde redox chemistry in a hydrophobic and aprotic ionic liquid (IL), 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([Bmpy] [NTf2]) by cyclic voltammetry and potential step methods. One electron oxygen reduction leads to superoxide radical formation in the IL. Trace water in the IL acts as a protic species that reacts with the superoxide radical. Acetaldehyde is a stronger protic species than water for reacting with the superoxide radical. The presence of trace water in the IL was also demonstrated to facilitate the electro-oxidation of acetaldehyde, with similar mechanism to that in the aqueous solutions. A multiple-step coupling reaction mechanism between water, superoxide radical and acetaldehyde has been described. The unique characteristics of redox chemistry of acetaldehyde in [Bmpy][NTf2] in the presence of oxygen and trace water can be controlled by electrochemical potentials. By controlling the electrode potential windows, several methods including cyclic voltammetry, potential step methods (single-potential, double-potential and triple-potential step methods) were established for the quantification of acetaldehyde. Instead of treating water and oxygen as frustrating interferents to ILs, we found that oxygen and trace water chemistry in [Bmpy][NTf2] can be utilized to develop innovative electrochemical methods for electroanalysis of acetaldehyde.

Keywords: Ionic liquid, acetaldehyde, oxygen reduction, water, electrochemical gas sensors

1. Introduction

Room-temperature ionic liquids (ILs) are organic salts that are liquid at room temperature [1,2]. Due to their high ion concentration, negligible volatility, high heat capacity and good electrochemical stability, they have been demonstrated as highly efficient heat transfer fluids [3] as well as electrolytes for electrochemical applications such as super capacitors, fuel cells, lithium batteries, photovoltaic cells, electrochemical mechanical actuators and electroplating [2,4–6]. In the past decade, our lab has systematically characterized the redox chemistry of a broad range of gaseous species (e.g. oxygen [7], methane [8], TDI [9]) in ILs for developing IL-based electrochemical gas sensors. We and others have discovered new electrochemical reactions in the IL that are not feasible in conventional solvents [10–12]. For example, in traditional aqueous based electrochemical systems, oxygen is removed by purging with inert gas such as nitrogen or argon to avoid interference from oxygen reduction reactions (i.e. O2 + 4H+ + 4e− → 2H2O or O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH−) [13]. However, in the anhydrous aprotic IL, oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) is a simple one electron reduction process (O2 + e− → O2·−) [14,15] instead of a complicated four electron reduction process shown in aqueous electrolyte. Rather than acting as an interferent as in aqueous systems, oxygen reduction in an IL is able to be quantified and utilized, which beneficially allows calibration of the quasi-reference electrode potential [16], and serving as an internal standard for quantification of other gaseous analytes [8]. Because the simple one electron reduction of oxygen forms the superoxide radical that is stable in the IL (i.e [Bmpy][NTf2]), this reaction has been successfully utilized for an amperometric oxygen sensor [7,17–21]. However, ILs for electrochemical gas sensor applications are challenged by the varying ambient conditions particularly humidity. Many literature reports have shown that water can strongly affect the physical and chemical properties of ILs such as viscosity, electrical conductivity, and reactivity, as well as solvation and solubility properties [22–24]. The effects of water depend on the amount of water present in the IL system. Water is a proton source. The oxygen reduction product superoxide radical is very reactive with water [25]. In the presence of some volatile organic compounds (VOCs), the protonation reaction between superoxide radicals and VOCs have also been observed [26]. Thus, fundamental understanding of the redox reactions of gaseous analytes in the IL in conditions closely related to real world ambient situations where oxygen and water co-exist is essential for the design and development of the IL based electrochemical sensors.

In this report, rather than treating water and oxygen as frustrating interferents in the IL electrochemical systems, we systematically studied the unique oxygen, trace water and their coupling chemistry in an ionic liquid in the presence of volatile organic compound (VOC). Since water is shown to have a much more dramatic acceleration effect on the diffusion of the ionic compounds compared to its effect on neutral species in the ILs, we select a neutral analyte, “acetaldehyde”. We also select aprotic 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([Bmpy][NTf2]) IL since it is stable in the presence of superoxide radical. Thus, it will be inert and do not act as a proton source [14,27–29]. [Bmpy][NTf2] is also hydrophobic which keeps the level of the water in the system at trace level. So the special ‘[Bmpy] [NTf2]-trace water’ system, which behaves as both non-aqueous solvent, where one electron reduction of oxygen [14,15] is dominant, and aqueous solvent, where water can be treated as a proton source [30–32] can be utilized to our advantages. By utilizing cyclic voltammetry or potential step methods, we could explore the water and oxygen coupling electrochemistry in the IL system so that the overall electrochemical reactions are balanced, i.e. the total amount of water and oxygen initially present at the IL system will be equal to the total amount of water produced as a product. This will ensure the ‘IL-trace water’ system remain constant during the quantitative analysis. We studied the electrode reactions coupled with chemical reactions of oxygen, water and acetaldehyde at two conditions by cyclic voltammetry and potential step methods. In one, the redox reactions of the acetaldehyde as well as water and oxygen could allow a mass balance of water and oxygen to be maintained by using cyclic voltammetry and triple potential step methods. In another, by selecting the potential window, we limit the redox reaction of acetaldehyde to occur without the presence of redox reactions of oxygen. In both conditions, linear relationships between current signals and the acetaldehyde concentrations were obtained, which supports the feasibility of the quantification of acetaldehyde in the ‘[Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water’ system.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals, reagents and acetaldehyde vapor sample preparation

1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide ([Bmpy][NTf2]) ionic liquid from Io-Li-Tech Inc. with 99% purity was used. The amount of water in it was 90 ppm determined by Karl-Fischer Titration, which is detailed in supporting information. High-purity liquid acetaldehyde (anhydrous, ≥99.5% (GC purity)) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pure N2 and the air containing 19.5 ~ 23.5 vol% O2 were obtained from PRAXAIR Inc.

The acetaldehyde has a boiling point of 20.1 °C with a high vapor pressure (902 mmHg at 25 °C). As shown in Fig. S1, in order to generate a gaseous sample of acetaldehyde at various low concentrations, the liquid acetaldehyde is preserved by storing it in a cold bath. The cold bath is made with mixtures of ethanol and dry ice, which can generate a low temperature of −72 °C. On the other hand, the gaseous air-acetaldehyde mixture is maintained by keeping the temperature of outside gas pipeline at 25 °C, a temperature higher than acetaldehyde boiling point. Digital mass flow controller (MKS Instruments Inc.) was used to control the flow rate (1 mL/min to 100 mL/min) of the carrier gases (nitrogen or air gas tanks) to a low-temperature bubbler filled with liquid acetaldehyde maintained at low temperature. Thereafter, the carrier gas with or without the acetaldehyde vapor were flown to a sealed flat bottom glass flask with fan inside for gas mixing. The low concentrations of acetaldehyde gas were generated by purging the carrier gas to liquid acetaldehyde stored in a cold bath. The required acetaldehyde vapor concentrations that entered into the electrochemical cell were prepared by adjusting the ratio of carrier gas volume and diluting gas volume. Note that all concentrations of acetaldehyde in this work are volume concentrations in gas phase not the absolute concentrations in the IL.

2.2. Electrochemical experimental details

The electrochemical cell set-up has been described in our previous work [7] detailed in Fig. S1 of supporting information. The working electrode is a Pt gauze cut into a circle with a geometric area of 1.1 cm2, counter electrode (platinum wire, with a diameter of 0.5 mm, Sigma-Aldrich), and Ag quasi-reference electrode (diameter of 0.5 mm, an area of 0.1 cm2, Sigma-Aldrich). The [Bmpy][NTf2] ionic liquid of 150 μL was added into the electro-chemical cell. The temperature and humidity in our lab is relative constant during the experiments. The electrochemical cell was put in a sealed glass container to further minimize the temperature and the humidity change in our laboratory.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Water and its coupling reaction with oxygen in [Bmpy][NTf2]

3.1.1. Oxygen reduction reaction in the presence of trace water

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was used to study the electrode reaction in [Bmpy][NTf2] containing trace water. The amount of water was determined by Karl-Fischer Titration to be 90 ppm (~6.8 mM). We defined the IL electrolyte used in this work as the “[Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water” electrolyte and all experiments were performed in this condition unless specially noted otherwise.

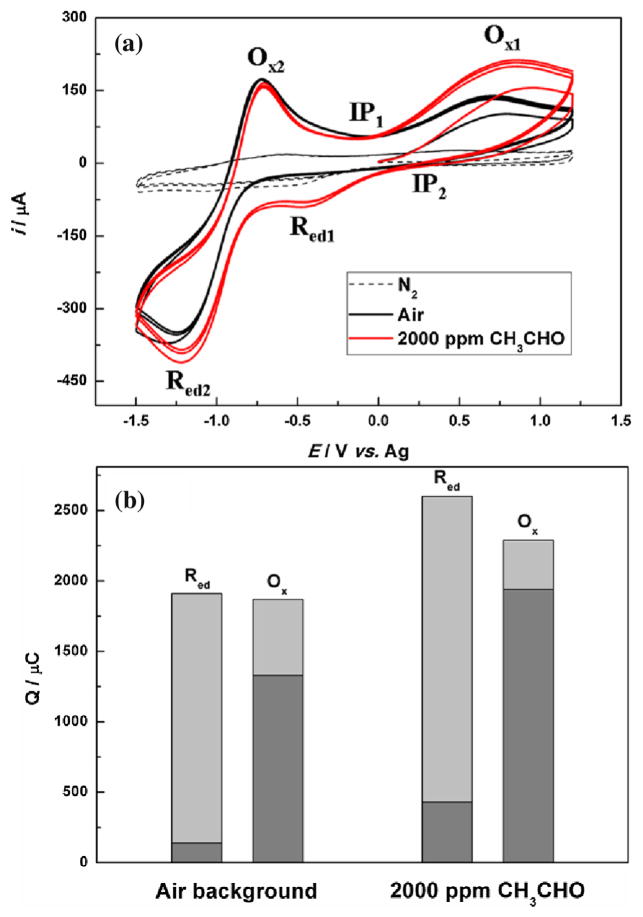

Fig. 1(a) shows the multiple cycle CV curves in nitrogen, air and acetaldehyde (2000 ppm concentration in gas phase with air as background gas). The oxygen concentration when air is used was determined to be (~3.5 mM in IL) using potential step chronoamperometry and Shoup and Szabo equation [33]. Compared to the CV in the nitrogen background, a pair of redox peaks (Red2 at −1.2 V and Ox2 at −0.7 V) were seen in the air condition. These redox peaks are consistent with the reported oxygen redox processes [7,14], in which the Red2 peak is attributed to the reduction of oxygen to superoxide radical (O2•−) and the corresponding Ox2 peak is the oxidation of the O2•− as shown in Eq. (1). The peak separation for Red2 and Ox2 is about 0.5 V which is much larger than those observed in traditional non-aqueous solvents (acetonitrile, dimethylformamide etc.) [25]. This is due to the large difference of diffusion coefficients of O2 and O2•− species in the more viscous ionic liquid systems [11,14,34].

Fig. 1.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms (multiple cycles) of Pt gauze working electrode in pure nitrogen, air and 2000 ppm (v/v) acetaldehyde in air (scan rate: 100 mV/s), conditioning potential is at zero volt; (b) Integrated charges of the redox peaks in the 3rd cycle of the cyclic voltammograms in air and 2000 ppm CH3CHO (Ox: oxidation process; Red: reduction process; dark gray: Red1 or Ox1; gray: Red2 or Ox2) (For interpretation of the references to colour in the text, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.).

| (1) |

Without the presence of acetaldehyde, when CV is performed at potential window in which oxygen reduction occur first to form superoxide radical O2•−. The high reactivity of O2•− could abstract proton from any proton source if its pKa is less than 24[26] including the cations of ionic liquid with α-proton or β-proton [14,35]. Since [Bmpy]+ cation has saturated 1-butyl and 1-methyl groups that is quite stable towards O2•−, water (pKa = 15.7) and/or acetaldehyde (pKa = 13.57) are the dominant proton source in our system. The O2•− can abstract a proton from water and form HO2• and OH− (Eq. (2)). Hydrogen peroxide (HO2•) can react with another superoxide to form HO2− (Eq. (3)). Combination of Eqs. (2) and (3) results in the net coupling reaction between superoxide and water, as shown in Eq. (4). The equilibrium constant of this reaction (Eq. (4)) is about 0.91 × 109, which indicates that this process goes to completion (Sawyer, D. T. et al. [26]). HO2− is a very reactive species and often it can form H2O2 in the presence of proton. However, in the presence of OH−, this reaction will not occur and the HO2− is the final product as summarized in Eqs. (2) and (3). The formed hydroperoxyl anion (HO2−) by the coupling reaction between superoxide radicals and water could be stabilized in the [Bmpy][NTf2] as no active protons in the structure of [Bmpy][NTf2] are available to further protonate HO2−. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the peak current ratio of oxygen redox reaction Ipa (Ox2)/Ipc (Red2) is 0.62 and the ratio of the charge (Q(Ox2)/Q(Red2)) under the peak is 28%, confirming above coupling reactions of superoxide with water.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

In order to clarify the role of water, the [Bmpy][NTf2] ionic liquid was dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C overnight and the water content was reduced to be ~5 ppm. Then the oxygen redox processes were studied and shown in Fig. S2. Obviously, compared to Fig. 1(a), the electrochemical reversibility for oxygen redox process (Red2 and Ox2) in Fig. S2 has been significantly improved. The peak current ratio of Red2 (248 μA) and Ox2 (226 μA) in Fig. S2 was much closer to 1 than that shown in Fig. 1(a) and the charge ratio (Q(Ox2)/Q(Red2)) was up to 91%, indicating the negligible coupling reaction between the superoxide radical and water in dried ionic liquid. At the same time, a wider potential window up to 1.5 V was studied in Fig. S2 to evaluate the potential window of [Bmpy][NTf2] on platinum electrode. The anodic potential window should be limited to less than 1.5 V since oxidation of the cation to form NTf2 radicals occurs at Pt electrode[12]. The anodic potential window in the current study was limited to be 1.2 V.

The effect of water was further studied by introducing additional small amount of water into the [Bmpy][NTf2]. As shown in Fig. S3, the reduction peak current (Red2) significantly increased. It is known that water could decrease the viscosity of the IL, thus increase the diffusion coefficients of electroactive species (e.g. O2). This can result in the increase of the peak current. The increase of conductivity of the IL due to the addition of water can reduce the IR drop and results in the smaller peak separation of oxygen redox peaks. Uwe Schröder et al. also observed this phenomenon[24]. The charge ratio of the oxygen redox reactions (Q(Ox2)/Q(Red2)) were only 6.1% and 5.2% when additional 0.5% (w/w) and 1.0% (w/w) water were added, respectively. This result supports that more superoxide radicals were consumed with the higher concentrations of water.

3.1.2. Recycle of water and oxygen by oxidation process

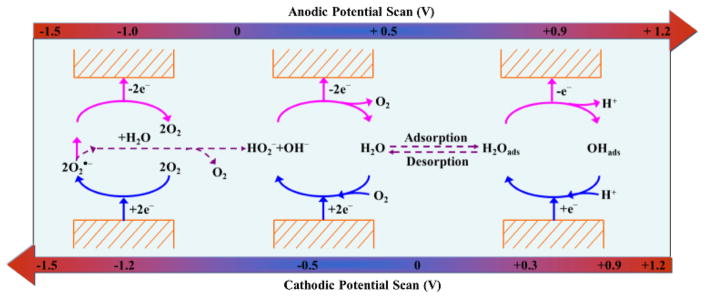

The product HO2− can be oxidized back to oxygen and proton during the oxidation cycle in CV shown in Eq. (5) reported by Pozo-Gonzalo, C. et al. [36,37] and René et al. [38]. Thus, during the complete potential cycle, the proton generated in the oxidation cycle combined with hydroxide generated in the reduction cycle will form water again. Thus the overall mass balance of water is maintained during cyclic voltammetry.

| (5) |

As shown in Fig. 1(a), an oxidation peak (Ox1) centered at ~0.7 V was observed in the air condition which is likely due to the oxidation process of HO2− as shown in Eq. (6). HO2− anion has high Bronsted basicity (pKa(HO2−) = 12)[26] and was shown to be easily electro-oxidized at a potential <0.5 V (vs. Ag/Ag+)[35,36]. Therefore, Eq. (5) can only contribute partially to Ox1 peak, namely the shoulder peak (0 ~ 0.5 V) of the Ox1 peak. Compared with Pozo-Gonzalo’s results[37], however, the Ox1 peak is much broader, almost starting from 0.0 V and ending at 1.2 V. This suggests the multiple oxidation processes involved in this Ox1 peak. The main reason for the difference (peak broadening) between Pozo-Gonzalo’s results and our results is that platinum electrode, not glassy carbon electrode, was used as the working electrode in our study. Based on Eq. (5), water could be re-generated at the electrode-electrolyte interface. We rationalize that the trace amount of water could be adsorbed and further electro-oxidized on the platinum surface to form platinum oxides (Pt-OHads) which results a much broad peak of Ox1. This is consistent with the report by Silvester, D. S. et al. [39] and Johnson, L. et al. [40] in aprotic and protic ionic liquids containing 100 ~ 300 ppm water, respectively. The oxidation potential for electro-oxidation of water at platinum in their study is found to be around 0.8 V ~ 1.2 V (vs. Ag or Pt wire), which coincides with the potential range in our results.

| (6) |

As seen from Fig. 1(a), the oxidation peak (Ox1) centered at 0.7 V and extended to 1.2 V, indicating that the process shown in Eq. (6) also involved in the main peak of Ox1. What’s more, as seen from Fig. S3, this Ox1 peak increased and especially centered at more negative potential when more water was introduced, which supports the process of platinum oxidation reaction facilitated by water. Further evidence can be seen from Fig. 2(a) and will be discussed below. In particular, the reduction peak of Pt-OHads could be identified in Fig. 3(c) (peak Red1‴), which could confirm that this process (Eq. (6)) occurs in [Bmpy][NTf2] even if the amount of water is in trace amount. So reactions shown in Eq. (5) together with Eq. (6) contribute to the broad oxidation peak (Ox1). Fig. 1(b) shows that the total charge for the overall reduction and oxidation processes between 1.2 V to −1.5 V is almost equal. This supports that the EC coupling reactions between oxygen reduction process and the trace water (summarized in Scheme 1). And both the oxygen and water equilibrium was maintained in CV experiments.

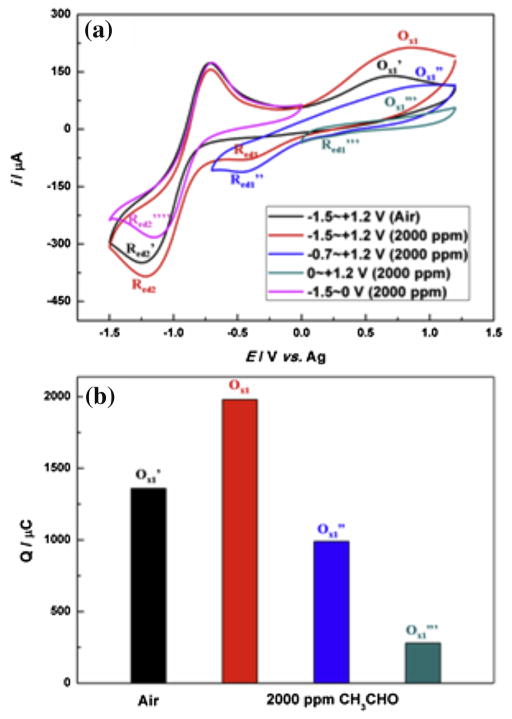

Fig. 2.

(a) Cyclic voltammograms (3rd cycle) of Pt gauze working electrode at different potential windows in air and 2000 ppm acetaldehyde (scan rate: 100 mV/s), conditioning potential is at zero volt; (b) Integrated charges of different oxidation peaks in the 3rd cycle of the cyclic voltammograms at different potential windows.

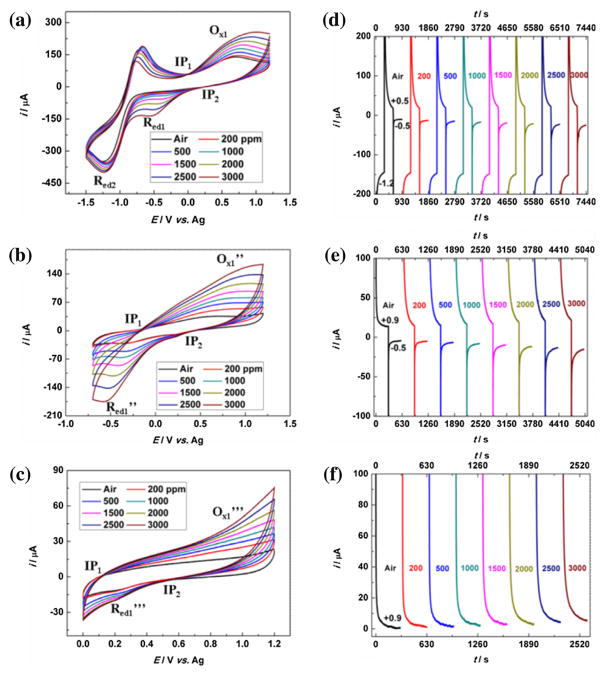

Fig. 3.

(a)–(c) cyclic voltammogramms at different CH3CHO gas phase concentrations and within different potential windows (scan rate: 100 mV/s); (d)–(f) chronoamperometric curves of platinum gauze exposing to different CH3CHO concentrations based on triple-potential step (−1.2 V → +0.5 V → −0.5 V) (d), double-potential step (+0.9 V → −0.5 V) (e) and single-potential step (f) (step to +0.9 V) methods.

Scheme 1.

Redox mechanisms of oxygen in the presence of trace water on platinum electrode surface in [Bmpy][NTf2] (potential range: −1.5 V ~ + 1.2 V).

3.2. Electrode Reactions Coupled with Chemical Reactions of Oxygen, Water and Acetaldehyde

Besides the EC reactions of water and oxygen, in the presence of acetaldehyde, the superoxide radicals can abstract protons from acetaldehyde (CH3CHO) which is a stronger acid (pKa = 13.57) [41] than water (pKa = 15.7). Therefore, the coupling reaction between acetaldehyde and superoxide radicals should be more thermodynamically favored than that of water. As seen from the CV curves (red line) in Fig. 1(a), the reduction peak (Red2) current further increased and the current of the oxidation peak Ox2 further decreased compared to that in air condition without acetaldehyde. As shown in Eq. (7), one mole of CH3CHO will theoretically consume two moles of superoxide radicals similar to Eq. (4).

| (7) |

Above EC reaction allows the acetaldehyde concentration to be indirectly related to the oxygen reduction peak at E = −1.2 V. Since both acetaldehyde and water could protonate the superoxide radicals, more HO2− could be generated in the system. Therefore, in the oxidation cycle of CV, the peak current of the Ox1 peak due to the oxidation of HO2− product should increase in the presence of acetaldehyde compared to that in the absence of acetaldehyde. As seen from Fig. 1(a), the oxidation current for Ox1 peak does significantly increase. At same time, more protons could be produced from Eq. (5) and thus water could be subsequently regenerated and form Pt-OH adsorbate at higher potential (> 0.5 V). The Pt-OH adsorbate at electrode surface has been demonstrated to facilitate the electro-oxidation of CH3CHO [30,32]. As a consequence, the follow-up electrochemical oxidation reactions can occur around the Ox1 peak potential in the presence of CH3CHO.

| (8) |

| (9) |

As seen from Eqs. (8) and (9), water and carbon dioxide are produced after the electro-oxidation of CH3CHO. To verify the products, FT-IR absorbance spectra of [Bmpy][NTf2] in air and after electrochemical reactions of acetaldehyde in the IL by cyclic voltammetry were obtained and compared (shown in Fig. S4). In order to avoid the interfering of the water and carbon dioxide in the ambient atmosphere, the air background has been subtracted to calibrate all the data. Apparently, comparing with the IL in the background air, an increase of the absorbance intensity in the range of wavenumber of 3600 ~ 3900 cm−1 and new absorption peaks in the range of wavenumber of 2300 ~ 2400 cm−1 were observed. These IR spectra change can be attributed to the vibration of C=C double bond [42] and O-H bond [43] respectively. FT-IR study supports that carbon dioxide and water formed after the redox reactions of CH3CHO.

Additionally, compared with the air background in Fig. 1(a), an obvious reduction peak (Red1) at −0.46 V could be observed in the presence of CH3CHO. Actually, in air background, there is also a similar but very minute peak at this potential shown in Fig. 1(b). The study by Switzer et al. [38] also observed this peak on the platinum electrode in the presence of protic species (phenol) in [Bmim][NTf2]. Moreover, as shown in Fig. S4, this process was significantly enhanced when additional water was intentionally introduced. It indicates that the Red1 peak is closely related to water. According to the Pourdaix diagram [44], another oxygen reduction process promoted by H2O shown in Eq. (10) should mainly contribute to the Red1 peak. The formal potential for this process in aqueous system is −0.07 V vs. SHE and −0.43 V vs. Ag, which is very close to our results (Red1 at −0.45 V vs. Ag). It indicates that Eq. (10) describes the process occurred around the reduction peak Red1. This process could further continue to form into other products, such as hydroxyl anion, which is designated in Eq. (11) [45]. That’s why this peak is broad observed in a wide potential range between −0.20 V and −0.60 V. Since more water could be formed during the electro-oxidation of acetaldehyde at Ox1 peak (Eqs. (8) and (9)), more water could be then reduced at Red1 peak. Thus, this peak shows larger current and is more apparent at higher acetaldehyde concentrations.

| (10) |

| (11) |

The multiple processes in both Red1 and Ox2 peaks also support the observation of two obvious isopotential points (IP1 and IP2) in Fig. 1(a). Isopotential point [46] is an indication that at least two processes occur at electrode surface such as one species is adsorbed or desorbed on the surface of the electrode at the beginning of the applied potential. The appearance of isopotential points (IP1 and IP2) is an evidence to support our rationalization about the absorption of hydroxyl and acetaldehdye on Pt into Pt-OHads and Pt-HBads (Eqs. (6) and (8)) as well as the multiple-step reactions of oxygen and water on Pt (Eqs. (10) and (11)) according to the report by Ramaswamy, N [45].

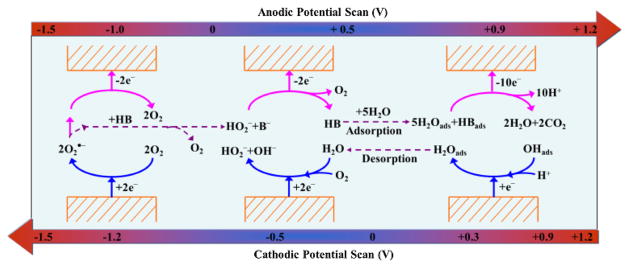

In summary, the Red2 and Ox2 peaks represent the typical redox process for oxygen and superoxide radical; however, there is chemical reaction coupled with the Red2 process; the broad oxidation peak Ox1 includes two main processes: the oxidation of hydroperoxyl anions (HO2−) at lower potential (< 0.5 V) and the oxidation of platinum and acetaldehyde at higher potential (0.5 ~ 1.0 V). And Red1 peak is the results of co-reduction of oxygen and water. The special ‘[Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water’ medium behaves both as a non-aqueous solvent that allows the existence of superoxide radicals and as an aqueous solvent in which trace water acts as a proton source that facilitates the formation of Pt-OH adsorbate. Thus, both reduction and oxidation processes of acetaldehyde are simultaneously observed in one system, which is impossible in traditional solvents system. The redox processes of acetaldehyde on platinum electrode surface in [Bmpy][NTf2] with air balanced gas and trace water are also summarized in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Redox mechanisms of trace water, oxygen and acetaldehyde (simplified as HB) on platinum electrode surface in [Bmpy][NTf2] (potential range: −1.5 V ~ + 1.2 V).

3.3. Scan rates and potential window study of acetaldehyde in [Bmpy] [NTf2] with oxygen and water: fundamental theory for developing electroanalytical methods for acetaldehyde analysis

3.3.1. Scan rates study

CVs at different scan rates were performed in the presence of acetaldehyde. As shown in Fig. S5(b), both the Ox1 peak current and Red1 peak current exhibit linear relationship to the square root of scan rates. Even for the reduction peak Red2, although there is coupling reaction between acetaldehyde and superoxide radicals, a linear relationship could still be obtained as the reaction rate is extremely fast (~1 ×1011), which is estimated by the reaction rate (0.91 ×109) [26] of Eq. (4) and the difference between pKa(H2O, 15.7) and pKa(CH3CHO, 13.57) [41]. Thus, the processes involved in peaks Ox1 and Red1 as well as Red2 are diffusion-controlled. Accordingly, Cottrell Equation could be applied for the determination of diffusion coefficient (DCH3CHO). Based on the chronoamperometric curves in the following Fig. 3(f), the curves for the current vs. t−1/2 were plotted and linearly fitted in Fig. S6. Then the slopes vs. CH3CHO concentrations were fitted in the inset of Fig. S6. As a result, DCH3CHO was calculated to be 9.3E–6 cm2/s (electron transfer number n = 10), which is close to the diffusion coefficients of oxygen [15,34], carbon dioxide [47] and hydrocarbons [48] in IL. These three diffusion-controlled processes, which are all related to acetaldehyde, enable the quantification of acetaldehyde with each peak leading to three calibration equations that can be utilized to cross-validate the measurement results as detailed in following discussion.

3.3.2. Potential window study

We studied the redox reactions of water, oxygen and acetaldehyde by CV at three potential windows as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. At potential window of −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V (Figs. 2 and 3b), the formation of superoxide radicals due to oxygen reduction reaction at −1.2 V will not occur. An oxidation process (Ox1″) could still be observed compared to the results observed in larger potential window within −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V (Figs. 2 and 3a). However, the Ox1″ peak centered at +0.85 V, which is more positive than that of Ox1. The reason is that there is no contribution from the electro-oxidation of coupling reaction products (hydroperoxyl anions (HO2−)) when no superoxide radicals are present in the system. Thus Ox1″ peak should be mainly attributed to the electrode-oxidation shown in Eqs. (8) and (9) (3Pt − OHads + CH3CHO → Pt + 2Pt − CO + 2H2O + 3H+ + 3e−an-d2Pt − OHads + 2Pt − CO → 4Pt + 2CO2 + 2H+ + 2e−). As discussed earlier, the oxidation potential for the electro-oxidation of CH3CHO by Pt-OHads is more positive than that for the electro-oxidation of hydroperoxyl anions (HO2−). That’s why the peak centered at higher potential in the narrower potential window of −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V compared with that in the wider potential window of −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V. Furthermore, the peak current for Ox1″ significantly decreased when the potential window was narrow at −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V. The charge for peak Ox1 in Fig. 2b is approximately two times of that for peak Ox1″, indicating that the Ox1″ peak is only contributed by the electro-oxidation of CH3CHO, while for Ox1 peak, it did consist of two processes: oxidation of HO2− and oxidation of CH3CHO. As discussed earlier, the HO2− also comes from the CH3CHO due to coupling reaction between CH3CHO and superoxide radicals. Therefore, the reactants concentration involved in Ox1 peak is doubled compared to Ox1″ peak.

For the reduction process, Red1″, it showed a higher peak current in the narrow potential window of −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V than that of Red1 in wider potential window between −1.5 V and +1.2 V. The reason is that no superoxide radicals are formed at potential window of −0.7~ +1.2 V and thus the protonation reaction of superoxide by water is not present. Thus, more water is available for the reduction process (Eqs. (10) and (11)) at Red1″ peak. The redox processes of acetaldehyde in [Bmpy][NTf2] within the potential window of −0.7 V ~ + 1.2 V can be simplified as shown in Scheme 2 (the two redox cycles shown in right), but without the contribution of HO2− due to absence of superoxide radicals.

Actually, the trace amount of water could independently promote the electro-oxidation of CH3CHO without oxygen. When potential window was set at 0 ~ + 1.2 V, small anodic current could still be observed. Also from Fig. 2(b), although the charge for peak Ox1‴ is much smaller than those for Ox1″ within −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V and for Ox1 within −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V, it is certain that some electro-oxidation processes occurred within 0 ~ + 1.2 V and contributed to the charge transfer. Moreover, it is noticeable that a reduction process Red1‴ around 0.3 V could be distinguished. Zhao, C. et al. [49] also observed this peak around 0.3 ~ 0.4 V (vs. Ag) on platinum surface in aprotic ionic liquids. They rationalized this peak to be related to the reduction of Pt-OHads, which is generated from the water existing in the ILs. Therefore, the electrochemical reaction shown in Equation (6) (Pt + H2O → Pt − OHads + H+ + e−) is completely possible. The hydroxyl formed at the electrode surface could significantly promote the electro-oxidation process of hydrocarbons [50–52] which should be beneficial for the electrochemical gas sensor development as described in latter sections. Therefore, the processes shown in Eqs. (8) and (9) should take place around the Ox1‴ peak. Additional evidence is shown in the experiments shown in Fig. 3, in which the cyclic voltammetric curves and chronoamperometric curves of Pt electrode exposing to different concentrations of CH3CHO were tested. Therefore, the redox processes of acetaldehyde in [Bmpy][NTf2] at potential window within 0 V ~ + 1.2 V are the simplest and was described in Scheme 2. As summarized in Scheme 2, the entire redox process is closely connected by the water. It further supports that trace water plays an extremely important role in the redox reactions of acetaldehyde in a hydrophobic and aprotic ionic liquid system.

Compared the CV curve at potential window of −1.5 ~ 0 V vs. −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V in Fig. 2, the reduction peak (Red1) is negligible at −1.5 ~ 0 V potential window and the peak current for Red2⁗ is considerably smaller. At potential window of −1.5 ~ 0 V, the coupling reaction products (HO2−) are not oxidized and could adsorbed at the electrode surface, thus resulting in less available electrode surface for the following reactions. At same time, the trace water could be consumed, thus resulting into the disappearance of Red1 peak that is related to water. Below we describe our experimental results by controlling the electrochemical potential window to develop several electroanalytical methods for quantification of acetaldehyde.

Fig. 3(a)–(c) summarized the cyclic voltammogramms at different potential windows in the presence of different CH3CHO concentrations in air. As seen, two isopotential points could be observed in all potential windows, supporting the multiple-step electrode reaction shown in Schemes 1 and 2. Moreover, it is obvious to see that peak Ox1, peak Red1 as well as peak Red2 become bigger with increasing concentrations of CH3CHO confirming these three peaks are all associated with CH3CHO. This result coincides with the scan rate experiment, where all these three processes have been demonstrated to be diffusion-controlled and related to acetaldehyde. Additionally, the enhancement of current signals shows linear relationship to the acetaldehyde concentrations, which has been plotted in Fig. S7(a). For Ox1, the current at +0.5 V was used for quantification based on the complete oxidation of HO2− at +0.5 V, which was shown in Schemes 1 and 2 (middle section). Obviously, three linear calibration curves (shown in Table 1) could be obtained, which is consistent with the three redox cycles shown in Scheme 2 and indirectly supports the proposed reaction mechanisms. Furthermore, the slopes (at −1.2 V, it is −16.8 nA/ppm; at +0.5 V, it is 20.6 nA/ppm) representing the sensitivity for these two redox processes are very close, which is a strong evidence that the Ox1 is directly correlated to Red2. As discussed in the early sections, if the anodic potential is limited to +0.5 V, the electron-transfer number of Ox1 peak is two as shown in Eq. (5). Without regard to the differences of the diffusion coefficients of the reactants involved in these two processes, the close sensitivities suggest that the electron-transfer number for Red2 peak should also be two, which is consistent with above conclusion about Eq. (7), where the electron-transfer number is two in the presence of acetaldehyde (1 mole of acetaldehyde vs. two moles of superoxide radical (that is formed by one mole of electrons and oxygen)). Therefore, the EC coupling reactions did take place in Red2 peak when acetaldehyde is introduced. Regarding to the relationship between Red1 and Ox1, the sensitivity of Red1 (−37.8 nA/ppm) is approximately two times of Ox1 (−20.6 nA/ppm). It is reasonable as the Red1 is an electrochemical reaction with up to four electrons transfer as shown in Eqs. (10) and (11).

Table 1.

Comparisons of electroanalytical methods based on CV and potential step methods.

| Potential windows (V) | Epeak (V) | Calibration curves based on CV curves i (nA)∝CCH3CHO (ppm) | Amperometric sensor methods | Eapplied (V) | Calibration curves based on potential steps i (nA)∝CCH3CHO (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ~ + 1.2 | +0.9 (Ox1‴) | i = 6.54*C + 2.26E4 | Single-potential step | +0.9 | i = 1.42*C + 7.06E2 |

| −0.7 ~ + 1.2 | +0.9 (Ox1″) | i = 34.6*C + 4.88E4 | Double-potential step | +0.9 | i = 2.68*C + 1.35E4 |

| −0.5 (Red1″) | i = −42.1*C − 2.15E4 | −0.5 | i = −3.21*C − 4.86E3 | ||

| −1.5 ~ + 1.2 | −1.2 (Red2) | i = −16.8*C − 3.49E5 | Triple-potential step | −1.2 | i = −1.95*C − 1.45E5 |

| +0.5 (Ox1) | i = 20.6*C + 1.23E5 | +0.5 | i = 1.86*C + 1.81E4 | ||

| −0.5 (Red1) | i = −37.8*C − 9.73E3 | −0.5 | i = −4.18*C − 1.26E4 |

3.4. Chronoamperometry and electroanalytical method characterization

Potential-step method has been used to understand the electrode reactions and especially it is preferred in practical electroanalytical sensors due to its simple operation and low cost electrochemical instrumentation [8,53]. Due to the multiple EC reactions, triple-potential step chronoamperometry methodology was firstly tested in our study to confirm the correlation of the three redox peaks (Red2 → Ox1 → Red1) and to establish new analytical methods for the ionic liquid based acetaldehyde gas sensor. Based on the above discussion, Ox1 (oxidation of HO2− and regeneration of O2 and H2O) is resulted from the products formed at Red2 (coupling reaction between O2·− and CH3CHO to generate HO2−); while the products generated at Ox1 resulted into the Red1 (reduction between O2 and H2O). And combined with the CV results of −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V in Table 1, −1.2 V, +0.5 V and +0.5 V were chosen as the step potentials and the currents of the potential steps were continuously measured. And a current sampling time of 300 s (50 times of time constant (τ), τ for [Bmpy][NTf2] is ~6 s [8]) was used at each potential step. The corresponding chronoamperometry curves (i–t curves) at different CH3CHO concentrations are shown in Fig. 3(d). As seen in Fig. S7(d) and Table 1, all three processes show excellent linearity. Moreover, relative magnitudes of the slopes for these three potentials are consistent with that of the calibration curves based on CV data, indicating that these three processes are mutually dependent, which further confirmed our proposed reaction mechanisms shown in Scheme 1 and 2. Therefore, triple-potential step method is feasible to develop IL-based acetaldehyde gas sensor. Three calibration curves could be utilized together for calibration, allowing the enhanced accuracy of the measurement by cross-validation.

In the early section, we show that by controlling the electrochemical potential windows, we can also restrict the electrode reactions. When the potential window was limited to −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V, same phenomenon that peak current is linearly increased with the acetaldehyde concentrations as the case in wider potential window (Fig. 3(a)) could be observed in Fig. 3(b). In particular, the similar slopes of the calibration curves (Fig. S7(b)) for Ox1″ and Red1″, as shown in Table 1, provide another evidence to demonstrate that these two processes are also correlated. In order to further verify the correlation of Ox1″ and Red1″ and simultaneously identify the possible sensor method, double potentials (+0.9 V and −0.5 V) chronoamperometry technique was applied. The chronoamperometric curves are shown in Fig. 3(e). From Fig. S7(e) and Table 1, it is clear to see that the currents at both potentials also linearly related to acetaldehyde concentration change. Almost equal sensitivity is found at both potentials, suggesting the mutual dependence of Ox1″ and Red1″. So, double-potential step method could be another choice for sensor methods in quantifying acetaldehyde vapor.

With regard to the potential window of 0 ~ + 1.2 V shown in Fig. 3(c), firstly, the reduction peak (Red1‴) representing the reduction of hydroxyl adsorbate based on above discussion is more clear to be differentiated, which further proved the important role of trace water in this case. Secondly, although the amount of water is trace, it is enough to facilitate the electro-oxidation of acetaldehyde since the Ox1‴ peak current increases with the acetaldehyde concentrations. Compared to previous current peaks in the other two potential windows, this pair of peaks (Ox1‴ and Red1‴) does not have very well peak shape. But there is current increase when acetaldehyde concentration increases, indicating some electrochemical processes related to acetaldehyde are involved in this pair of peaks. The reasons for the not well-shaped peaks: 1) water content in ionic liquid is trace and then the intermediate product (Pt-OH) that could promote the electrochemical oxidation of acetaldehyde is very small; 2) multiple electrochemical reactions are involved, thus the peak becomes very broad; 3) the high viscosity of ionic liquid caused the slow kinetics and also broadness of peaks. From Fig. S7(c) and Table 1, the current at +0.9 V shows a linear relationship to acetaldehyde concentration. Therefore, the corresponding single-potential step chronoamperometry should be possible for determining the existence of water and the concentration of acetaldehyde. As demonstrated in Fig. 3(f) and S7(f), the current at +0.9 V did exhibit excellent linear relationship to the CH3CHO concentrations. It illustrates that due to the presence of trace water, a simple single-potential step method can be developed for acetaldehyde sensing.

In summary, when water is absent, triple-potential step method is still applicable; when water exists, single- and double-potential step method could also be used to realize the VOC detection. Therefore, the detection of acetaldehyde is not determined by the existence or inexistence of water or the amount of water in the environment. ‘[Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water’ system significantly extends the application scope of traditional solvent system and provides more detection methods. Table 1 summarized the calibration curves based on the CV and three potential step methods. All of them show good linearity, which indicates IL-based acetaldehyde gas sensor can be calibrated with multiple calibration curves, allowing the selectivity and accuracy enhancement by cross-validation. In contrast to the ethylene oxidation at Au electrode which requires the presence of water in the IL [54], we expect the quantification of acetaldehyde can still be obtained in dry IL. By performing the experiments at various potential windows using CV and potential step methods, a total of six calibration curves could be obtained. Taking together of all the measurement results with these multiple methods could lead to a recognition pattern of acetaldehyde similar to that of electronic nose[55–57]. Pooling the multiple parameters can significantly increase the measurement accuracy.

4. Conclusions

In real world condition, the accurate amount of water content will be fluctuating depending on the temperature and humidity. Thus, it will be hard to control/measure the exact amount of water and oxygen in the IL electrolyte in a real environment. Our work elucidates that the unique water and oxygen redox chemistry in the [Bmpy][NTf2] is beneficial for the electrochemical VOC sensor development. Trace water promotes the hydrophobic [Bmpy] [NTf2] IL to maintain it as non-aqueous solvent but also to exhibit certain properties of aqueous solvents. The adsorption of trace water on platinum electrode into Pt-OH adsorbate could facilitate the oxidation of acetaldehyde in the special ‘[Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water’ system in ambient condition. Different electrochemical behaviors of acetaldehyde could be controlled by judiciously setting the electrode potentials to control the reactions of oxygen and water in IL. The characteristics of the acetaldehyde redox mechanisms in [Bmpy][NTf2]-trace water-oxygen system allow three chronoamperometry methods to be established (i.e. by restricting the potential window at 0 ~ + 1.2 V, the electro-oxidation of acetaldehyde occurs in a similar manner to that in aqueous solvent. This process can be used to develop a single-potential step chronoamperometry for acetaldehyde detection. If the potential window was widened to −0.7 ~ + 1.2 V, a double-potential step method can be established for an acetaldehyde gas sensor. When reduction of oxygen process was included at the potential window of −1.5 ~ + 1.2 V, the oxygen reduction into superoxide radicals in nonaqueous solvent could couple with protic analyte (acetaldehyde) to enable a triple-potential step method). By rationally utilizing the chemistry of real world environment species (water and oxygen) and the unique characteristics of hydrophobic aprotic IL, we have shown an innovative approach to solve the lingering issues of water and oxygen interference in the IL-based gas sensor development, laying down the foundation for developing new electroanalytical methods for sensing important VOCs at real world conditions and with appreciable sensitivity and selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Zeng likes to thank the support of National Institute of Health (NIH-NIEHS, R01ES022302). The authors also like to thank the helpful discussions with Dr. Michael Sevilla. We like to thank Dr. Carl Lira’s lab at Michigan State University’s help for Karl-Fischer titration experiments.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Experimental set-up, FT-IR, partial CV data and calibration curves are shown in Supplementary data. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.08.108.

References

- 1.Earle MJ, Seddon KR. Ionic liquids. Green solvents for the future. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2000;72:1391–1398. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galinski M, Lewandowski A, Stepniak I. Ionic liquids as electrolytes. Electrochimica Acta. 2006;51:5567–5580. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Valkenburg ME, Vaughn RL, Williams M, Wilkes JS. Thermochemistry of ionic liquid heat-transfer fluids. Thermochimica Acta. 2005;425:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Bostrom T. Application of Ionic Liquids in Solar Cells and Batteries: A Review. Current Organic Chemistry. 2015;19:556–566. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mousavi MPS, Wilson BE, Kashefolgheta S, Anderson EL, He S, Buehlmann P, Stein A. Ionic Liquids as Electrolytes for Electrochemical Double-Layer Capacitors: Structures that Optimize Specific Energy. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2016;8:3396–3406. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeck R. Application potentials of ionic liquids based electrolytes in electroplating. Materialwissenschaft Und Werkstofftechnik. 2008;39:901–906. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Lin P, Baker GA, Stetter J, Zeng X. Ionic Liquids as Electrolytes for the Development of a Robust Amperometric Oxygen Sensor. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83:7066–7073. doi: 10.1021/ac201235w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Guo M, Baker GA, Stetter JR, Lin L, Mason AJ, Zeng X. Methane-oxygen electrochemical coupling in an ionic liquid: a robust sensor for simultaneous quantification. Analyst. 2014;139:5140–5147. doi: 10.1039/c4an00839a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin L, Rehman A, Chi X, Zeng X. 2,4-Toluene Diisocyanate Detection in Liquid and Gas Environments Through Electrochemical Oxidation in an Ionic Liquid. Analyst. 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5an02220g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Mahony AM, Silvester DS, Aldous L, Hardacre C, Compton RG. Effect of Water on the Electrochemical Window and Potential Limits of Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data. 2008;53:2884–2891. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzzeo MC, Evans RG, Compton RG. Non-haloaluminate room-temperature ionic liquids in electrochemistry – A review. Chemphyschem. 2004;5:1106–1120. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200301017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y, Wang Z, Chi X, Sevilla MD, Zeng X. In Situ Generated Platinum Catalyst for Methanol Oxidation via Electrochemical Oxidation of Bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide Anion in Ionic Liquids at Anaerobic Condition. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2016;120:1004–1012. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b09777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarasevich MR, Korchagin OV. Electrocatalysis and pH (a review) Russian Journal of Electrochemistry. 2013;49:600–618. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans RG, Klymenko OV, Saddoughi SA, Hardacre C, Compton RG. Electroreduction of oxygen in a series of room temperature ionic liquids composed of group 15-centered cations and anions. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2004;108:7878–7886. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang XJ, Rogers EI, Hardacre C, Compton RG. The Reduction of Oxygen in Various Room Temperature Ionic Liquids in the Temperature Range 293–318 K: Exploring the Applicability of the Stokes-Einstein Relationship in Room Temperature Ionic Liquids. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:8953–8959. doi: 10.1021/jp903148w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Huang Y, Jin X, Mason AJ, Zeng X. Ionic liquid thin layer EQCM explosives sensor. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical. 2009;140:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buzzeo MC, Hardacre C, Compton RG. Use of Room Temperature Ionic Liquids in Gas Sensor Design. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:4583–4588. doi: 10.1021/ac040042w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong SQ, Wei Y, Guo Z, Chen X, Wang J, Liu JH, Huang XJ. Toward Membrane-Free Amperometric Gas Sensors: An Ionic Liquid–Nanoparticle Composite Approach. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2011;115:17471–17478. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toniolo R, Dossi N, Pizzariello A, Doherty AP, Susmel S, Bontempelli G. An oxygen amperometric gas sensor based on its electrocatalytic reduction in room temperature ionic liquids. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2012;670:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gębicki J, Kloskowski A, Chrzanowski W. Effect of oxygenation time on signal of a sensor based on ionic liquids. Electrochimica Acta. 2011;56:9910–9915. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang R, Okajima T, Kitamura F, Ohsaka T. A Novel Amperometric O2 Gas Sensor Based on Supported Room-Temperature Ionic Liquid Porous Polyethylene Membrane-Coated Electrodes. Electroanalysis. 2004;16:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köddermann T, Wertz C, Heintz A, Ludwig R. The Association of Water in Ionic Liquids: A Reliable Measure of Polarity. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006;45:3697–3702. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid JESJ, Walker AJ, Shimizu S. Residual water in ionic liquids: clustered or dissociated? Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2015;17:14710–14718. doi: 10.1039/c5cp01854d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroder U, Wadhawan JD, Compton RG, Marken F, Suarez PAZ, Consorti CS, de Souza RF, Dupont J. Water-induced accelerated ion diffusion: voltammetric studies in 1-methyl-3-[2, 6-(S)-dimethylocten-2-yl] imidazolium tetrafluoroborate, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate and hexafluorophosphate ionic liquids. New Journal of Chemistry. 2000;24:1009–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chin DH, Chiericato G, Nanni EJ, Sawyer DT. PROTON-INDUCED DISPROPORTIONATION OF SUPEROXIDE ION IN APROTIC MEDIA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1982;104:1296–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawyer DT, Valentine JS. HOW SUPER IS SUPEROXIDE. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1981;14:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayyan M, Mjalli FS, Hashim MA, AlNashef IM, Tan XM. Electrochemical reduction of dioxygen in Bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide based ionic liquids. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2011;657:150–157. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayyan M, Mjalli FS, Hashim MA, AlNashef IM, Al-Zahrani SM, Chooi KL. Long term stability of superoxide ion in piperidinium, pyrrolidinium and phosphonium cations-based ionic liquids and its utilization in the destruction of chlorobenzenes. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 2012;664:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan XZ, Alzate V, Xie Z, Ivey DG, Qu W. Oxygen Reduction Reaction in 1-Butyl-1-methyl-pyrrolidinium Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide: Addition of Water as a Proton Species. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 2014;161:A451–A457. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia G, Silva-Chong J, Rodriguez JL, Pastor E. Spectroscopic elucidation of reaction pathways of acetaldehyde on platinum and palladium in acidic media. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry. 2014;18:1205–1213. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai SCS, Koper MTM. Electro-oxidation of ethanol and acetaldehyde on platinum single-crystal electrodes. Faraday Discussions. 2008;140:399–416. doi: 10.1039/b803711f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou ZL, Kang TF, Zhang Y, Cheng SY. Electrochemical sensor for formaldehyde based on Pt-Pd nanoparticles and a Nafion-modified glassy carbon electrode. Microchimica Acta. 2009;164:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoup D, Szabo A. Chronoamperometric current at finite disk electrodes. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry. 1982;140:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katayama Y, Sekiguchi K, Yamagata M, Miura T. Electrochemical behavior of oxygen/superoxide ion couple in 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide room-temperature molten salt. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 2005;152:E247–E250. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Islam MM, Imase T, Okajima T, Takahashi M, Niikura Y, Kawashima N, Nakamura Y, Ohsaka T. Stability of Superoxide Ion in Imidazolium Cation-Based Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 2009;113:912–916. doi: 10.1021/jp807541z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pozo-Gonzalo C, Torriero AAJ, Forsyth M, MacFarlane DR, Howlett PC. Redox Chemistry of the Superoxide Ion in a Phosphonium-Based Ionic Liquid in the Presence of Water. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2013;4:1834–1837. doi: 10.1021/jz400715r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pozo-Gonzalo C, Virgilio C, Yan Y, Howlett PC, Byrne N, MacFarlane DR, Forsyth M. Enhanced performance of phosphonium based ionic liquids towards 4 electrons oxygen reduction reaction upon addition of a weak proton source. Electrochemistry Communications. 2014;38:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rene A, Hauchard D, Lagrost C, Hapiot P. Superoxide Protonation by Weak Acids in Imidazolium Based Ionic Liquids. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113:2826–2831. doi: 10.1021/jp810249p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silvester DS, Aldous L, Hardacre C, Compton RG. An electrochemical study of the oxidation of hydrogen at platinum electrodes in several room temperature ionic liquids. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2007;111:5000–5007. doi: 10.1021/jp067236v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson L, Ejigu A, Licence P, Walsh DA. Hydrogen Oxidation and Oxygen Reduction at Platinum in Protic Ionic Liquids. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2012;116:18048–18056. [Google Scholar]

- 41.https.//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

- 42.Sun SG, Lin Y. Kinetics of isopropanol oxidation on Pt(111), Pt(110) Pt(100), Pt (610) and Pt(211) single crystal electrodes – Studies of in situ time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy. Electrochimica Acta. 1998;44:1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soria J, Sanz J, Sobrados I, Coronado JM, Maira AJ, Hernandez-Alonso MD, Fresno F. FTIR and NMR study of the adsorbed water on nanocrystalline anatase. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2007;111:10590–10596. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pourbaix MJN. Atlas of electrochemical equilibria in aqueous solutions. National Association of Corrosion Engineers; Houston: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramaswamy N, Mukerjee S. Fundamental Mechanistic Understanding of Electrocatalysis of Oxygen Reduction on Pt and Non-Pt Surfaces: Acid versus Alkaline Media. Advances in Physical Chemistry. 2012;2012:17. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Untereker DF, Bruckenstein S. Interpretation of isopotential points. Common intersection in families of current-potential curves. Analytical Chemistry. 1972;44:1009–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moganty SS, Baltus RE. Diffusivity of Carbon Dioxide in Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2010;49:9370–9376. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camper D, Becker C, Koval C, Noble R. Diffusion and solubility measurements in room temperature ionic liquids. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2006;45:445–450. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao C, Bond AM, Lu X. Determination of Water in Room Temperature Ionic Liquids by Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry at a Gold Electrode. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84:2784–2791. doi: 10.1021/ac2031173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tapan NA. A mechanistic approach to elucidate ethanol electro-oxidation. Turkish Journal of Chemistry. 2007;31:427–443. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ide MS, Davis RJ. The Important Role of Hydroxyl on Oxidation Catalysis by Gold Nanoparticles. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2014;47:825–833. doi: 10.1021/ar4001907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Zou S, Cai WB. Recent Advances on Electro-Oxidation of Ethanol on Pt- and Pd-Based Catalysts: From Reaction Mechanisms to Catalytic Materials. Catalysts. 2015;5:1507–1534. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans RG, Klymenko OV, Price PD, Davies SG, Hardacre C, Compton RG. A comparative electrochemical study of diffusion in room temperature ionic liquid solvents versus acetonitrile. Chemphyschem. 2005;6:526–533. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zevenbergen MAG, Wouters D, Dam VAT, Brongersma SH, Crego-Calama M. Electrochemical Sensing of Ethylene Employing a Thin Ionic-Liquid Layer. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83:6300–6307. doi: 10.1021/ac2009756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaffer RE, Rose-Pehrsson SL, McGill RA. A comparison study of chemical sensor array pattern recognition algorithms. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1999;384:305–317. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L, Tian F, Pei G. A novel sensor selection using pattern recognition in electronic nose. Measurement. 2014;54:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lipatov A, Varezhnikov A, Wilson P, Sysoev V, Kolmakov A, Sinitskii A. Highly selective gas sensor arrays based on thermally reduced graphene oxide. Nanoscale. 2013;5:5426–5434. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00747b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.