Abstract

CLB2.0, a constituent of PM, induces secretion of multiple cytokines and chemokines that regulate airway inflammation. Specifically, IL-6 upregulates CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 expression. Interestingly, of the tight junction proteins examined, claudin-1 expression was inhibited by CLB2.0. While the overexpression of claudin-1 decreased CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC expression, it increased the expression of the anti-inflammatory mucin, MUC1. CLB2.0-induced IL-6 secretion was mediated by ROS. The ROS scavenger N-acetylcysteine inhibited CLB2.0-induced IL-6 secretion, thereby decreasing the CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC expression, whereas CLB2.0-induced MUC1 expression increased. CLB2.0 activated the ERK1/2 MAPK via a ROS-dependent pathway. ERK1/2 downregulated the claudin-1 and MUC1 expressions, whereas it dramatically increased CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC expression. These findings suggest that CLB2.0-induced ERK1/2 activation acts as a switch for regulating inflammatory conditions though a ROS-dependent pathway. Our data also suggest that secreted IL-6 regulates CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 expression via ROS-mediated downregulation of claudin-1 expression to maintain mucus homeostasis in the airway.

Keywords: Airway inflammation, Claudin-1, IL-6, MUC1, MUC5AC, PM

INTRODUCTION

The respiratory track in the human body has been highly exposed to extra-stimuli, such as air pollutants, viruses, bacteria, and microbes (1). Industrial development has induced a number of respiratory diseases. Now, many reports suggested that airborne particulate matter (PM) as important environmental pollutants induced many different diseases (2). PM is composed of transition metals, ions (sulfate, nitrate), quinoid stable radicals of carbonaceous material, minerals, reactive gases, and materials of biologic origin (2). Toxicological studies have indicated that PM induces many mechanisms of harmful cellular effects, such as radical-generating activity, activation of proinflammatory factors, DNA oxidative damage, and cytotoxicity (2). Airway mucus has an important factor to maintain the mucociliary clearance in the trachea and bronchi and acts to protect the lower airways and alveoli from PM and pathogens (3). Mucin hyperproduction and hypersecretion are frequently detected in many respiratory diseases such as airway infection, rhinitis, sinusitis, and otitis media (4). Mucin hyperproduction leads to decreased mucociliary clearance, increasing the chance of secondary infection because of other diseases in the airway (5, 6). Identifying the molecular mechanism underlying PM-induced mucin hyperproduction will enhance our understanding of mucin hypersecretion during PM-induced inflammation and provide the negative regulatory mechanism to develop novel therapeutic anti-PM reagents.

Tight junction proteins are expressed on the apical membrane of epithelia and play the critical roles of the barrier function and cell polarity. They consist of three groups of proteins: transmembrane proteins (occludin, Claudin, and junctional adhesion molecules); peripheral membrane proteins [ZO (Zonula occludens)-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, MUPP-1], which have PDZ (PSD95-Dlg-ZO1) domains and bind to transmembrane proteins, and cytoplasmic proteins (cingulin, 7H6 antigen, etc.) (7). The Claudin proteins are a family of major membrane proteins (24 identified), fundamental to the construction of tight junctions (8). By controlling the transfer of small ions and nutrients between cells, they keep cell-cell communication and homeostasis (9). Additionally, the Claudin are important for the preservation of differentiation, proliferation, cellular polarity, and so on (10). Even though they expressed throughout the lateral intercellular junction and nearby the basal cells that anchor the columnar epithelium to the basal lamina, expression of Claudin-1 and -4 could activate increased localization to the apical tight junction region (11). So far, the relationship between Claudin, PM, and airway mucins has not been studied.

Expose of airway epithelium to PM induces cytokine/chemokine gene expression and increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines (12, 13). PM induces the increase in vascular permeability via the ROS-mediated calcium leakage via activated transient receptor potential cation channel M2 and via ZO-1 degradation by activated calpain (14). Although PM increased airway mucin expression and secretion (15, 16), the precise relationship between Claudin-1 and PM-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 during the airway inflammation and the mechanisms by which cytokines affect PM-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 expression have not been identified.

In this study, the effect of Claudin-1 on PM-induced mucin expression was investigated, and the relationship between Claudin-1 and airway inflammation in human airway epithelial cells was also established.

RESULTS

CLB2.0 secretes IL-6 extracellulary in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHNE) cells

Although collected PM2.5 was utilized at the top of some building at Dong-A university (Busan, Korea), the composition of PM2.5 is very variable depending on weather, skill, and so on. Indeed, Carboxyl Latex Beads (CLB) 2 μm (# C37278; ThermoFisher Scientific) should be used to get the same results. In addition, because PM contains so many heavy metals, the effect of heavy metals cannot be ruled out. CLB comprises carboxyl charge-stabilized hydrophobic polystyrene microspheres, and CLB2.0 has several different size beads with size ranging from 0.02 to 2.0 μm (3).

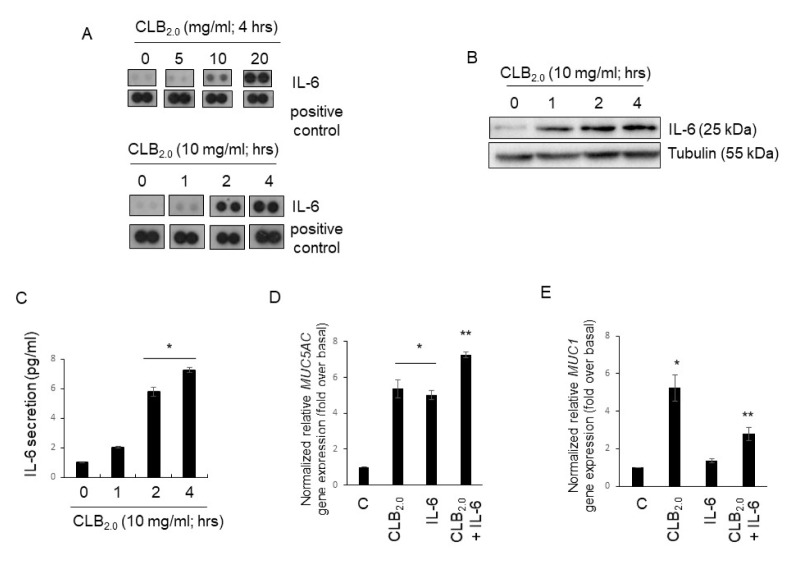

To determine whether CLB2.0 treatment controls the secretion of cytokines extracellularly that may regulate the respiratory microenvironment and affect tight junction proteins (TJs), we performed the cytokine array with cell culture medium after the treatment of NHNE cells with CLB2.0 for 4 h in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). The secretion of IL-6 increased dramatically in the cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A, upper panel). In addition, the extracellular secretion of IL-6 reached its maximum level after 4 h of treatment with CLB2.0 (Fig. 1A, lower panel). To examine whether CLB2.0 stimulation is essential for IL-6 secretion and overproduction, IL-6-specific Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B) and ELISA (Fig. 1C) were performed. CLB2.0 did induce IL-6 secretion and overproduction in a time-dependent manner.

Fig. 1.

CLB2.0 induces IL-6 secretion and overexpression in NHBE cells. (A) Cells were treated with CLB2.0 for 4 h, and a cytokine assay was performed in a dose- and time-dependent manner. (B) After the treatment of CLB2.0 for 4 h, the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis with specific anti-IL-6 antibody. (C) The cells were then treated with CLB2.0 for 4 h, and their supernatants were collected. The levels of IL-6 in the cell supernatants were measured by ELISA. *P < 0.05 compared with control. Values shown represent the means ± SDs of three technical replicates from a single experiment. Cells were treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml), IL-6 (30 ng/ml) and both CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) and IL-6 (30 ng/ml) for 24 h and their total RNA were collected, and then qRT-PCR for MUC5AC (D) and MUC1 (E) transcript were performed. *P < 0.05 compared to the control, **P < 0.05 compared to CLB2.0 only.

MUC5AC was known to the inflammatory mucin, but MUC1 was recognized as anti-inflammatory mucin (17–20). Interestingly, MUC5AC gene expression increased significantly by the cotreatment of CLB2.0 and IL-6 compared to CLB2.0 alone (Fig. 1D), but the MUC1 gene expression dramatically decreased by the cotreatment of CLB2.0 and IL-6 (Fig. 1E). Therefore, IL-6 secreted by the CLB2.0 can control CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 gene expression in the airway epithelial cells. Therefore, the cells activated by CLB2.0 could promote the secretion and overproduction of IL-6, which may trigger signal transduction pathways to regulate the inflammatory microenvironment by either an autocrine or paracrine manner in airway epithelial cells.

Overexpressed Claudin-1 decreases CLB2.0 and IL-6-induced MUC5AC gene expression, but increases MUC1 gene expression

When the same experiments (Fig. 1) were carried out using human lung mucoepidermoid carcinoma cell line, NCI-H292 cells, we got the same results as in the normal cells (Supplement Fig. 1). Unfortunately, because primary cells have technical limitations, NCI-H292 cells were used.

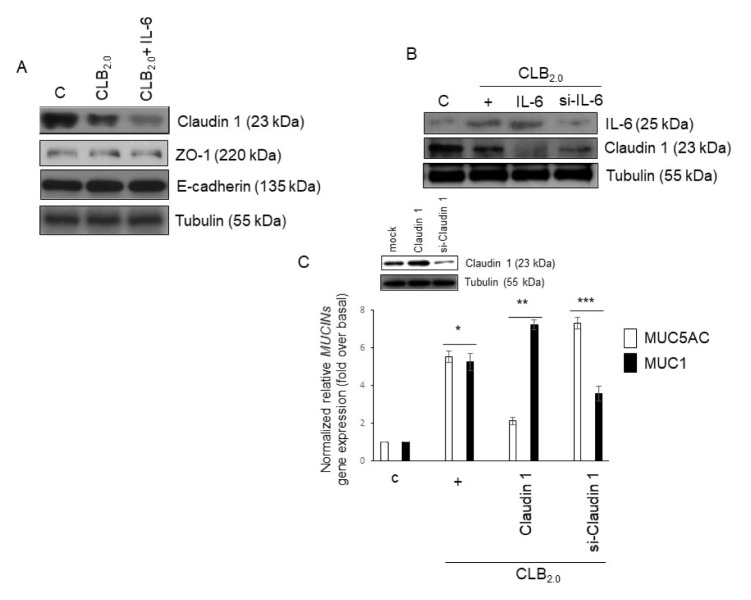

We hypothesized whether CLB2.0 could affect tight junction proteins to invade airborne PM across airway epithelium. First, TJs such as Claudin-1, ZO-1, and E-cadherin were investigated. Claudin-1 expression was inhibited by CLB2.0, and the cotreatment of CLB2.0 and IL-6 dramatically inhibited Claudin-1 expression, but not ZO-1 and E-cadherin expression (Fig. 2A). To investigate whether secreted IL-6 could affect Claudin-1 expression, specific siRNA-IL-6 was used. Both recombinant IL-6 and CLB2.0 completely diminished Claudin-1 expression, whereas siRNA-IL-6 partially inhibited Claudin-1 expression, suggesting that both CLB2.0 and secreted IL-6 could completely decrease Claudin-1 expression (Fig. 2B). Next, in order to investigate whether decreased Claudin-1 expression might affect airway inflammation, qPCR for MUC5AC (inflammatory mucin) and MUC1 (anti-inflammatory mucin) in NCI-H292 cells was performed. Interestingly, ectopic overexpressed Claudin-1 dramatically inhibited MUC5AC gene expression, but siRNA-Claudin 1 increased the CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC gene expression. In addition, the overexpressed Claudin-1 increased CLB2.0-induced MUC1 gene expression, but siRNA-Claudin-1 decreased significantly MUC1 gene expression (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that CLB2.0 could decrease Claudin-1, and thus the diminished Claudin-1 could not play its own physiological functions during CLB2.0-induced airway inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Claudin-1 on CLB2.0-induced MUC5AC and MUC1 gene expression. (A) After the cells were treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) or CLB2.0 and IL-6 (30 ng/ml) for 24 h, Western blot analysis was performed with specific Claudin-1, ZO-1, and E-cadherin antibodies. Tubulin was used as the loading control. (B) Cells were transfected with either a construct driving the expression of wild-type IL-6 or siRNA specific for IL-6. Cells were then treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) for 4 h prior to the generation of total cell lysates, and then Western blot analysis for Claudin-1 was performed. (C) Cells were transfected with either a construct expressing of wild-type Claudin-1 or siRNA specific for Claudin-1, followed by treating with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) for 24 h prior to the generation of total cell lysates, and then qRT-PCR for MUC5AC and MUC1 mucin genes were performed. *P < 0.05 compared to control, **P < 0.05 compared to CLB2.0-treated cells, and ***P < 0.05 compared to CLB2.0/wild-type Claudin-1-treated cells.

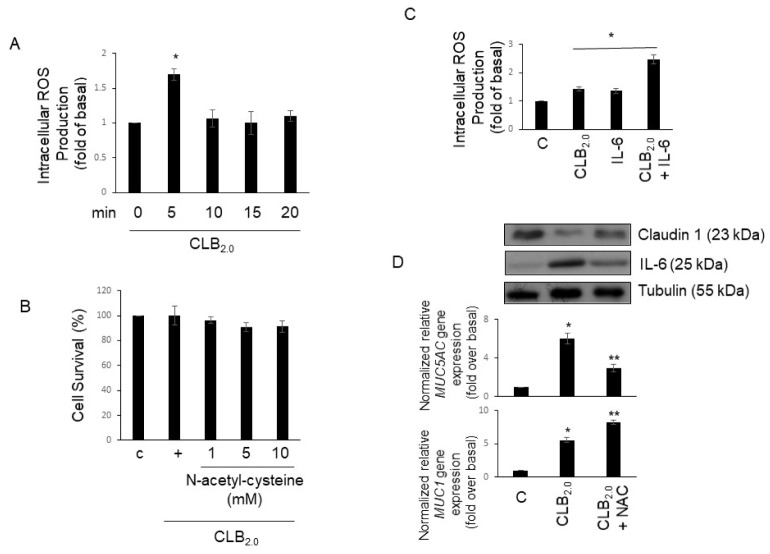

ROS production by CLB2.0 is mediated for inhibiting Claudin-1 expression in the airway epithelial cells

The PM could induce cytokine and chemokine expression to alter the inflammatory microenvironment. However, little is known about an intracellular mechanism of PM in regulating inflammation in airway epithelial cells. Accordingly, to investigate whether CLB2.0-induced could control inflammatory cytokine gene expression in the airway, ROS production was investigated. Cells were treated with CLB2.0 in a time-dependent manner, and ROS production was measured using DCF. ROS production picked at 5 min and then decreased at 10 min (Fig. 3A). In addition, ROS production was unaffected cell viability (Fig. 3B). Moreover, cotreatment of CLB2.0 and IL-6 increases the ROS production much more than CLB2.0 alone (Fig. 3C). Next, to check whether ROS might mediate Claudin-1, IL-6, and MUC5AC gene expression, NAC was used. Inhibition of ROS production increased Claudin-1 expression, but decreased IL-6 and MUC5AC gene expression. Interestingly, the cotreatment of CLB2.0 and NAC increased MUC1 gene expression. These results suggest that ROS production is not only critical for the inhibition of Claudin-1 and the activation of MUC5AC gene expression in response to CLB2.0, but also essential for CLB2.0-induced secretion extraracellularly of IL-6.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ROS produced by CLB2.0 on Claudin-1 and mucin genes expression. (A) The cells were pre-incubated in the presence of 50 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min, and then exposed to CLB2.0 for the indicated times. Cell-associated DCF fluorescence levels were analyzed by flow cytometry. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. (B) The cells were pre-incubated in the presence of N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) for 1 h in a dose-dependent manner, and then treated CLB2.0 for 1 h. Cell proliferation assay was performed with CCK-8 (Dojindo; Rockville, MD). (C) After the cells were treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) or CLB2.0 and IL-6 (30 ng/ml) for 5 min, flow cytometry was analyzed to measure the ROS production. *P < 0.05 compared to the control. (D) After the cells were treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) or CLB2.0 and NAC (1 mM; pretreatment for 1 h) for 24 h, Western blot anlaysis (upper panel) and qRT-PCR for MUC5AC and MUC1 (lower panel) mucin genes were performed. *P < 0.05 compared to the control, **P < 0.05 compared to the CLB2.0-treated cells.

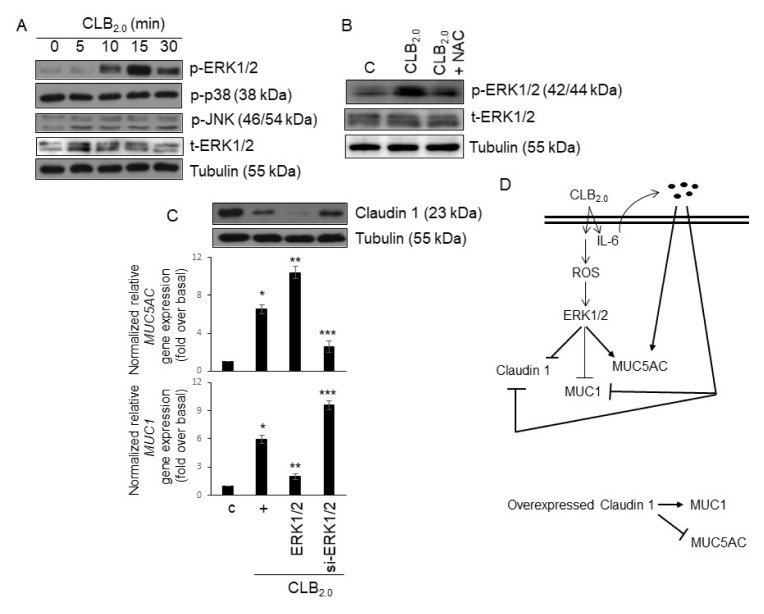

CLB2.0-induced activation of ERK1/2 is mediated by ROS and plays as a switch molecule to regulate the inflammatory condition

To examine which molecule is involved in the downstream signaling protein of ROS production within the signaling pathway of Claudin-1 and mucins gene expression induced by CLB2.0, the phosphorylation of MAPKs by phospho-specific antibodies was investigated. MAPKs are widely distributed in mammalian cells and can be activated by ROS. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by CLB2.0 reached a maximum at 15 min and decreased at 30 min after the CLB2.0 treatment, but not p38 and JNK MAPKs (Fig. 4A). To check whether ERK1/2 activation is related to the ROS production after the treatment of CLB2.0, NAC was used (Fig. 4B). NAC dramatically decreased CLB2.0-induced ERK1/2 activation, suggesting that ROS might be critical for CLB2.0-induced ERK1/2 activation. Interestingly, the treatment with wild-type ERK1/2 inhibited CLB2.0-induced Claudin-1 and MUC1 expression, but increased MUC5AC gene expression. However, siRNA-ERK1/2 significantly increased CLB2.0-induced Claudin-1 and MUC1 expression and dramatically decreased MUC5AC gene expression (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

ERK1/2 plays as a switch molecule to regulate the inflammatory condition. (A) After the cells were treated with CLB2.0 in a time-dependent manner, Western blots were performed to detect MAPK activation. Tubulin was used as the loading control. (B) After the cells were treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) or CLB2.0 and NAC (1 mM; pretreatment for one hour) for 15 mins, Western blot for ERK1/2 phosphorylation was performed. (C) Cells were transfected with either a construct expressing of wild-type ERK1/2 or siRNA specific for ERK1/2. The cells were then treated with CLB2.0 (10 mg/ml) for 24 h prior to the generation of total cell lysates, and then qRT-PCR for MUC5AC and MUC1 mucin genes were performed. *P < 0.05 compared to the control, **P < 0.05 compared to the CLB2.0-treated cells, and ***P < 0.05 compared to the CLB2.0/wild-type ERK1/2-treated cells. (D) A schematic diagram is presented to show the potential mechanisms for secretion of IL-6, and their physiological roles during the inflammatory responses.

DISCUSSION

Inhalation of approximately 12,000 L of air a day passing through the airway epithelium results in the accumulation of up to 25 million particles an hour (21). The first defense line against inhaled harmful particles on damaging the airway epithelium is the mucus overproduction and hypersecretion. Airway mucus is a critical element of the mucociliary clearance system in the respiratory track, and thus plays to defend the lower airways and alveoli from exposure/infection of PM and pathogens (3). However, there is no evidence that mucus hypersecretion and overproduction may affect PM-induced airway inflammation in the human respiratory track. MUC5AC has been considered inflammatory mucin because many inflammatory mediators, air pollutants, and pathogens increased MUC5AC overproduction and hypersecretion to progress inflamed microenvironment (22–24), whereas MUC1 has been considered anti-inflammatory mucin to maintain homeostasis (17–20). In this study, we suggest that CLB2.0 disrupts the balance between the inflammatory condition and homeostasis to make inflamed condition in the airway. Thus, it is critical to understand the regulatory mechanism by which negative regulatory proteins/molecules decreasing the MUC5AC overexpression and hypersecretion in the airway epithelium are cleared and stimulants (chemical compounds) increase the MUC1 overproduction to maintain (restore) homeostasis in the respiratory track.

Recently, Wang et al. reported that PM could disrupt endothelial cell barrier via TJs degradation, thus increases vascular permeability (14). The same group also reported that PM disrupted human lung endothelial barrier via ROS- and p38 MAPK-dependent pathway (25). Furthermore, Caraballo et al. reported PM altered alveolar epithelial barrier via a decrease in occludin (26). Consequently, PM should disrupt the barrier to invade into cells via inhibiting TJs. Accordingly, we hypothesized that overexpressed TJs protein in the human airway epithelium might prevent the weakness of the membrane permeability. According to the result of cytokine array, concentrated IL-6 secreted extracellularly at early time by CLB2.0 (Fig. 1C). Extracellular IL-6 could transfer inflammatory singling to the nearby cells and the cells secreting IL-6, up-take IL-6 again (autocrine manner). In fact, Gao et al. suggested the importance of autocrine IL-6 signaling in lung cancer (27). The cotreatment of CLB2.0 and IL-6 significantly disrupted Claudin-1 compared to CLB2.0 only (Fig. 2A). This result provides very important evidence for TJs, because of the following reasons 1) CLB2.0 could secrete several cytokines/chemokines to completely disrupt TJs, 2) IL-6 could transfer inflammatory signaling to the nearby cells and synergistically amply CLB2.0 signaling, and 3) if impaired TJs were restored by genetic method (gene-delivery system; e.g., transfection or viral infection), restored TJs could prevent CLB2.0 invasion because of much rigid membrane.

Oxidative stress has provided the important mechanisms for PM-induced pro-inflammatory responses in the airway (28). Both primary ROS generation by PM and PM components could generate ROS production, as well as PM-exposed cells formed ROS and reactive nitrogen species via a secondary pathway (29). Short-term exposure to PM2.5 causes lung inflammation and mucus hypersecretion in mice, in a study that implicated EGFR signaling pathway activation (16). Similarly, ROS produced by CLB2.0 was strongly related to CLB2.0 functions that decreased the Claudin-1 and MUC1 gene expression in the airway epithelial cells. In addition, CLB2.0-induced ERK1/2 activation was mediated by ROS, and then plays a switch molecule to progress either inflamed condition or homeostasis. This is an important finding, because ERK1/2 is critical signaling protein to increase the MUC5AC gene expression. In our previous reports, negative regulatory proteins (SHP-2 and IL-1ra) attenuate ERK1/2 activation to abolish MUC5AC gene expression in inflamed cells (24). Thus, understating the effects of ERK1/2 and Claudin-1 function is expected to provide effective information of the working mechanism of CLB2.0 toxicity, as well as for the development of innovative therapeutic medication against destructive human health roles of air pollution inhalation.

In summary, the results of this study support a novel working hypothesis in which CLB2.0 induces the intracellular secretion of IL-6 in the airway epithelial cells, primarily through autocrine or paracrine manner. This activation results in a CLB2.0/IL-6/ROS/ERK1/2-dependent increase in the MUC5AC gene expression, which in turn activates the expression/secretion of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines (Fig. 4D). In contrast, overexpressed Claudin-1 may overcome CLB2.0-induced toxicity/airway inflammation because of increased MUC1 gene expression and dampens the inflammatory response to enhance anti-inflammation in the airway microenvironment. This study suggests an anti-inflammatory role of Claudin-1 during the airway inflammation and provides the molecular mechanisms of CLB2.0-mediated immune responses in air pollutants inhalation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Carboxyl latex beads (4% w/v, 2 μm) were purchased from Thermo Fisher (C37278). The ELISA kit and purified cytokine of IL-6 were purchased from R&D Systems. The ROS inhibitor was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cytokine assay

The cytokine assay was performed using a Human Cytokine Array Panel A kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, serum-starved cells were treated with CLB2 for 4 h. After the treatment, the supernatant was assayed according to the kit instructions.

RT-PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using a BioRad iQ iCycler Detection System (BioRad Laboratories; Hercules, CA) with iQ SYBR Green Supermix. Reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μl - including 10 μl 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 300 nM of each primer, and 1 μl of the previously reverse-transcribed cDNA template.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Where appropriate, statistical differences were assessed by the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (NRF-2016R1D1A1B03932521 for K.S.S.)

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Song KS. KATP channel controls LPS-induced MUC5AC overexpression in vivo. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;8:248–252. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valavanidis A, Fiotakis K, Vlachogianni T. Airborne particulate matter and human health: toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev. 2008;26:339–362. doi: 10.1080/10590500802494538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Li Q, Kolosov VP, et al. Regulation of particulate matter-induced mucin secretion by transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptors. Inflammation. 2012;35:1851–1859. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song KS, Lee TJ, Kim K, et al. cAMP-responding element-binding protein and c-Ets1 interact in the regulation of ATP-dependent MUC5AC gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26869–26878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose MC, Nickola TJ, Voynow JA. Airway mucus obstruction: mucin glycoproteins, MUC gene regulation and goblet cell hyperplasia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:533–537. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.f218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida Y, Ban Y, Kinoshita S. Tight junction transmembrane protein Claudin subtype expression and distribution in human corneal and conjunctival epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2103–2108. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escudero-Esparza A, Jiang WG, Martin TA. The Claudin family and its role in cancer and metastasis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2011;16:1069–1083. doi: 10.2741/3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, et al. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from Claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1099–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morin PJ. Claudin proteins in human cancer: promising new targets for diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9603–9606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coyne CB, Gambling TM, Boucher RC, et al. Role of Claudin interactions in airway tight junctional permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L1166–L1178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00182.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker S, Mundandhara S, Devlin RB, et al. Regulation of cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells in response to ambient air pollution particles: further mechanistic studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Usatyuk PV, Gorshkova IA, et al. Regulation of COX-2 expression and IL-6 release by particulate matter in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:19–30. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0105OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang T, Wang L, Moreno-Vinasco L, et al. Particulate matter air pollution disrupts endothelial cell barrier via calpain-mediated tight junction protein degradation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwanaga K, Elliott MS, Vedal S, et al. Urban particulate matter induces pro-remodeling factors by airway epithelial cells from healthy and asthmatic children. Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25:653–660. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2013.827283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Val S, Belade E, George I, et al. Fine PM induce airway MUC5AC expression through the autocrine effect of amphiregulin. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86:1851–1859. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi S, Park YS, Koga T, et al. TNF-α is a key regulator of MUC1, an anti-inflammatory molecule, during airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:255–260. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0323OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KC. Role of epithelial mucins during airway infection. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato K, Uchino R, Lillehoj EP, et al. Membrane-Tethered MUC1 Mucin Counter-Regulates the Phagocytic Activity of Macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:515–523. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0177OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi IW, Ahn DW, Choi JK, et al. Regulation of Airway Inflammation by G-protein Regulatory Motif Peptides of AGS3 protein. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27054. doi: 10.1038/srep27054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers DF. Physiology of airway mucus secretion and pathophysiology of hypersecretion. Respir Care. 2007;52:1134–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groneberg DA, Eynott PR, Oates T, et al. Expression of MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins in normal and cystic fibrosis lung. Respir Med. 2002;96:81–86. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson L, Shah I, Loh AX, et al. MUC5AC and inflammatory mediators associated with respiratory outcomes in the British 1946 birth cohort. Respirology. 2013;18:1003–1010. doi: 10.1111/resp.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong JY, Kim J, Kim B, et al. IL-1ra Secreted by ATP-Induced P2Y2 Negatively Regulates MUC5AC Overproduction via PLCβ 3 during Airway Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 20162016:7984853. doi: 10.1155/2016/7984853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang T, Chiang ET, Moreno-Vinasco L, et al. Particulate matter disrupts human lung endothelial barrier integrity via ROS- and p38 MAPK-dependent pathways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:442–449. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0402OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caraballo JC, Yshii C, Westphal W, et al. Ambient particulate matter affects occludin distribution and increases alveolar transepithelial electrical conductance. Respirology. 2011;16:340–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao SP, Mark KG, Leslie K, et al. Mutations in the EGFR kinase domain mediate STAT3 activation via IL-6 production in human lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3846–3856. doi: 10.1172/JCI31871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, et al. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Øvrevik J, Refsnes M, Låg M, et al. Activation of proinflammatory responses in cells of the airway mucosa by particulate matter: Oxidant- and non-oxidant-mediated triggering mechanisms. Biomolecules. 2015;5:1399–1440. doi: 10.3390/biom5031399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.