Abstract

A large number of transcriptional activation domains (TADs) are intrinsically unstructured, meaning they are devoid of a three-dimensional structure. The fact that these TADs are transcriptionally active without forming a 3-D structure raises the question of what features in these domains enable them to function. One of two TADs in human glucocorticoid receptor (hGR) is located at its N-terminus and is responsible for ~70% of the transcriptional activity of hGR. This 58-residue intrinsically-disordered TAD, named tau1c in an earlier study, was shown to form three helices under trifluoroethanol, which might be important for its activity. We carried out heteronuclear multi-dimensional NMR experiments on hGR tau1c in a more physiological aqueous buffer solution and found that it forms three helices that are ~30% pre-populated. Since pre-populated helices in several TADs were shown to be key elements for transcriptional activity, the three pre-formed helices in hGR tau1c delineated in this study should be critical determinants of the transcriptional activity of hGR. The presence of pre-structured helices in hGR tau1c strongly suggests that the existence of pre-structured motifs in target-unbound TADs is a very broad phenomenon.

Keywords: Human glucocorticoid receptor (hGR), Intrinsically disordered protein (IDP), Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), Pre-structured motif (PreSMo)

INTRODUCTION

Although many globular proteins are three-dimensionally structured, they contain short flexible/disordered loops composed of less than 20 amino acid residues (1). This phenomenon of so-called protein disorder has been known for decades, but since the late 1990s, we have begun encountering some peculiar proteins that contain long unfolded/disordered regions (more than 40 and up to hundreds of residues) that do not form 3-D structures (2, 3). These proteins are now named as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (4, 5) and represent a special case of protein disorder. IDPs are highly unorthodox because even without three-dimensional structures, they are capable of performing specific biological functions (including transcription, translation, chaperoning, and cell cycle regulation) or are responsible for many fatal diseases (such as cancers, prion diseases, neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and so on) (6–9). Many viral proteins in HIV-1, HBV, HCV, SARS virus, and AI virus are also IDPs or contain intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) (4, 10–13).

The unexpected correlation between the “unstructured” nature of IDPs/IDRs and their functionality ended up nullifying the decades-old structure-function paradigm, 3-D structure = function, in protein science and structural biology. Approximately 40% of the entire protein kingdom is predicted to consist of IDPs/IDRs (11), and the proportion of IDPs/IDRs is much higher (~60%) in transcription factors (14). In the case of globular proteins, the collective structural features (secondary, tertiary and quaternary) provide a reasonable explanation of function. However, the absence of tertiary structures in IDPs makes it quite challenging to come up with an explanation on why and how they should function at all. For example, we still do not have a clear understanding on how IDPs bind to their targets.

Initially, IDPs/IDRs were erroneously thought to be completely unstructured (CU) without any trace of secondary structures (15, 16). In contrast to this early view, a more quantitative structural picture on IDPs/IDR has emerged from many high-resolution multi-dimensional NMR investigations conducted over the last two decades. These studies have revealed that at least ~70% of IDPs/IDRs are not fully “unstructured”, but contain transient local structural elements in their free state that mediate binding of IDPs to targets (4). The IDPs/IDRs containing transient local structural elements are therefore described to be in a mostly unstructured (MU) state (3) since they are not completely unstructured in terms of secondary structure. Although these transient secondary structures in IDPs, which were recently named in 2012 as pre-structured motifs (PreSMos) (4), were first noticed in the late 1990s (2, 3, 17, 18), they were not given the general name of PreSMos until structural details for a statistically significant number (~4 dozens) of MU type IDPs became available. Most well-known PreSMos are the amphipathic helix and two turns found in the 73-residue long transactivation domain (TAD) of tumor suppressor p53 (3). These PreSMos are the key determinants that enable binding of p53TAD to mdm2 (19), p62 (20), RPA (21) as well as the NCBD of CBP (22) and Bcl-2 (23). In other words, the PreSMos of p53 TAD are the “active sites” that are pre-populated transient secondary structures primed for target-binding. These PreSMos found in the p53 TAD, and other PreSMos observed in various IDPs/IDRs (4, 24–26) are likely to be at least part of the long-sought answer to the question of how IDPs/IDRs bind to various targets including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids and metals.

The glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the nuclear receptor family, contains independent domains for DNA-binding and transactivation (27). Human GR contains two transactivation domains (TADs), one at its N-terminus (tau1) and the other at its C-terminus (tau2) (28). The former consists of residues 77–262 (186-residues) and is responsible for the major transcriptional activity of hGR. We have previously shown that the minimal (“core”) domain of tau1 containing residues 187–244 (called tau1c hereafter) retained ~70% of the transactivation activity of the intact tau1 (29). hGR tau1c was one of the IDPs that was studied in the early days before the PreSMo concept was introduced. Since many transcription factors and TADs contain PreSMos, we wanted to learn whether tau1c also contains PreSMos. A previous NMR study on hGR tau1c indicated that it was largely unstructured in an aqueous solution, but it formed three helices under a helix-inducing solvent, trifluoroethanol (TFE) (30). To determine whether the helices observed under TFE may be considered as PreSMos, we performed multi-dimensional NMR experiments on hGR tau1c in aqueous solvents using a 15N/13C-double labeled hGR tau1c.

RESULTS

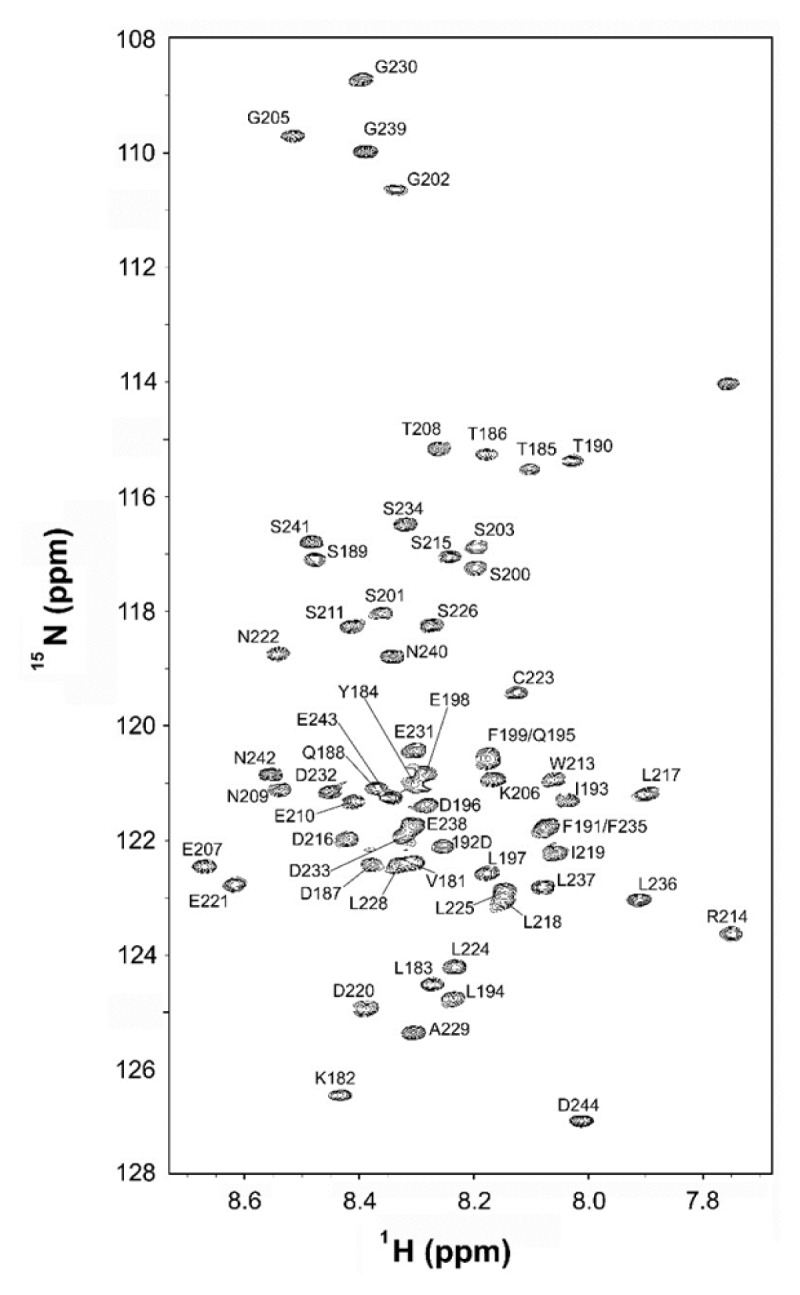

Fig. 1 shows a fingerprint region of an 15N-1H heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of hGR tau1c with resonance assignment. Based on the narrow chemical-shift dispersion in both 15N and 1H dimensions, we can confirm its overall unfolded/disordered nature in agreement with the bioinformatics prediction (Suppl. Fig. S1). Using the standard triple-resonance assignment procedure, we achieved a full NMR resonance assignment for the backbone 15N and the amide protons of the 64-residue hGR tau1c excluding the first two N-terminal residues, Met, and His, that originated from the N-terminal glutathione-S-transferase fusion linker. For 3 prolines which do not have backbone amide NH protons, their aliphatic protons were fully assigned. The resonance assignment of hGR tau1c summarized in Table S1 was sufficient for structural characterization of the hGR tau1c, i.e., delineation of the PreSMo-forming residues.

Fig. 1.

A fingerprint region in an 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of the N-terminal region of hGR tau1c (residues 181–244) obtained at 10°C and pH 6.5 on 90% H2O/10% D2O.

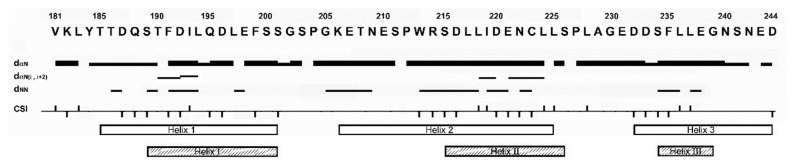

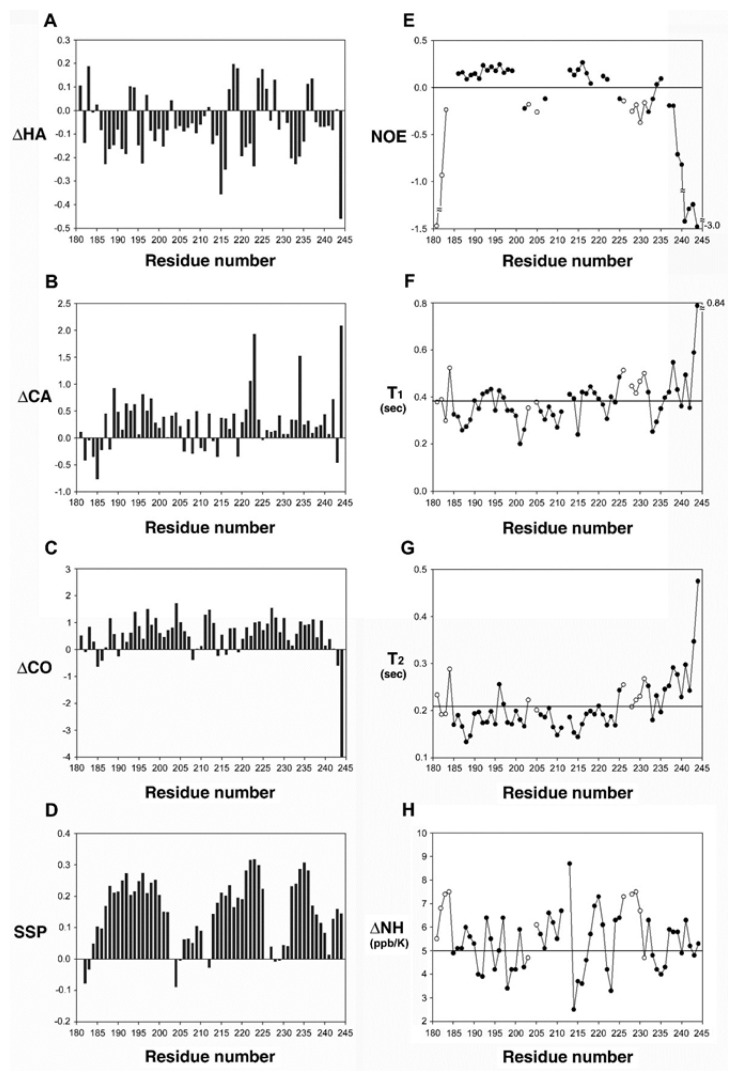

Fig. 2 shows the amino acid sequence of hGR tau1c along with the associated interproton NOEs and chemical shift indices (CSI). Continuous dNN interproton NOEs from a NOESY spectrum (a mixing time of 150 ms) and CSIs are observed for three regions of the hGR tau1c, indicating the pre-structured (non-random) nature of hGR tau1c with several helix-forming residues. A quick examination of Fig. 2 reveals that the location of the three helices detected in the current study mostly overlaps with those previously detected under TFE. Fig. 3 shows several NMR parameters measured for hGR tau1c. Whether a PreSMo exists or not is usually determined by a combination of all available NMR parameters (25, 31). The left panel in Fig. 3 shows a summary of the chemical shift and deviations from random chemical shift values and SSP (secondary structure propensity) scores. The SSP scores were obtained by combining various chemical shifts (Hα, Cα, Cβ) (32) to provide the degree of pre-population of a PreSMo. The SSP values are often more conclusive about the location of a PreSMo than individual chemical shift deviations. Positive SSP scores over 4 residues or more indicate the formation of a helix, whereas negative values suggest non-helical (β-type) secondary structures. Fig. 3d shows that hGR tau1c contains three helical PreSMos, the first (Helix 1) formed by residues 185–202, the second (Helix 2) by residues 206–225, and the third (Helix 3) by residues 232–244. All helices are ~20–30% pre-populated. For most PreSMos positive (0.0–0.5), heteronuclear NOEs were observed. However, some reported heteronuclear NOEs for PreSMos were non-positive, being zero or slightly negative (3, 31).

Fig. 2.

The amino acid sequence of hGR tau1c. tau1c is shown along with the associated interproton NOEs and chemical shift indices (CSI). Continuous dNN interproton NOEs and CSIs are observed for three PreSMo regions of hGR tau1c, indicating their pre-structured (non-random) nature with transient helices. See the text for details. The three helix PreSMos identified in this study and those reported previously are shown as open and hatched boxes.

Fig. 3.

Left panel: deviation of (A) 1Hα, (B) 13Cα, (C) carbonyl chemical shifts from random coil values and (d) the SSP (secondary structure propensity) scores of hGR tau1c (181–244). In (d), positive scores indicate helical propensity while negative values suggest formation of non-helical type PreSMos. Right panel: 1H-15N heteronuclear NOEs (E), backbone 15N relaxation times, T1 (F), T2 (G), and temperature coefficients of the backbone amide hydrogens (H). The horizontal lines in (F) and (G) indicate an average value. In (H), temperature coefficients less than 5 ppb/K suggests formation of a helix.

DISCUSSION

By definition, PreSMos are transient or nascent secondary structures (average population of ~30%) detected by NMR in aqueous solution (4). With the discovery of PreSMos, we can classify IDPs/IDRs into two subclasses, a CU type and an MU type. Although several NMR parameters are used in combination to accurately delineate the residues that form a PreSMo, the SSP scores alone allow one to quickly judge if any IDP/IDR is a CU type or an MU type (3, 25, 33, 34). The SSP scores of hGR tau1c clearly indicate that it is an MU type, and the combination of all NMR parameters show that it forms three helical PreSMos: the first helix (Helix 1) formed by residues 185–202, the second (Helix 2) by residues 206–225, and the third (Helix 3) by residues 232–244, respectively. The three helices previously observed under TFE were Helix I (189–201), Helix II (215–226) and Helix III (234–239), respectively (30). Even though the three helices delineated in this study reasonably overlap with the three helices observed under TFE, notable differences exist at the N-termini of Helix 1 and Helix 2 and at the C-terminus of Helix 3.

For example, the first residue of Helix 1 is 185T whereas the first one in Helix I is 189S. This difference can be ascribed to the fact that the starting residue of hGR tau1c is 181V while that in the previous work was 188Q. Thus, it was not possible to observe the potential helix formation by residues 181–187 in the previous work. Another significant difference is noted at the N-terminus of Helix 2. Helix 2 determined in the current study has a 9-residue longer N-terminal portion than Helix II, and its N-terminus starts at residue 206K instead of 215S. The previous work used only interproton NOEs since the SSP scores were introduced only in 2006. The usage of TFE must have generated helices in a higher population so that the interproton NOEs were stronger than those observed in the current study when we compare Fig. 2 of this report with Fig. 3 in the previous report (30). Previous data indicated that 213W is important for transcriptional activity (35). Even though this residue was not a part of Helix II, a thorough reexamination of the data insinuates that 213W may belong to Helix II. It would be interesting to see if the inclusion of this bulky hydrophobic residue in a helical conformation would better explain the activity of hGR tau1c. Since the residue at 212 is a proline in Helix 2, it might introduce a kink just prior to 213W. Another difference is that the C-terminus of Helix 3 is longer by 5 residues than Helix III. It also is very interesting to learn that two prolines, 204P and 226P, flank the C-termini of the two helices, Helix 1 and Helix 2. The helix-flanking prolines of helix PreSMos that might act as a subtle activity switch were described earlier (36).

Tau1c of hGR is one of the IDRs that was studied very early in IDP research when controversy was keen regarding the question of whether transactivation domains should contain some sort of specificity determinants that mediate target binding (3). Although hGR tau1c was shown to form three helices that might be important for transcriptional activity (30), this pioneering data was not considered when the PreSMo concept was formulated (4) since the observation of helices was made in TFE that may artificially induce helix formation. The current study was initiated to re-investigate this IDR in aqueous solvents in order to determine if it forms PreSMos and if it should be classified as an MU type. We confirmed that hGR tau1c is an MU type IDR. Our work demonstrated that the PreSMo concept is further expandable to other IDPs/IDRs, including the IDPs studied before the introduction of the PreSMos concept. Recent mutation studies on p53 TAD and CNBR (37, 38) have elegantley shown that the degree of pre-population of a helix PreSMo is critical for target binding, suggesting the degree of PreSMo pre-population is a variable inherent in the MU type IDPs/IDRs that is quite subtly tuned for target binding. It would be interesting to see if one can also establish such a correlation between the degree of helix pre-population and the activity of hGR tau1c.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed experimental and computational procedures are described in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Korea-Hungary and Pan EU collaborative project from the National Research Council of Science and Technology (NST) (NTC2251422) of Korea (to KH & AW) as well as grants from the Swedish Research Council and Swedish Cancer Society (to AW).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.The RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org)

- 2.Daughdrill GW, Chadsey MS, Karlinsey JE, Hughes KT, Dahlquist FW. The C-terminal half of the anti-sigma factor, FlgM, becomes structured when bound to its target, σ28. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 1997;4:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H, Mok KH, Muhandiram R, et al. Local structural elements in the mostly unstructured transcriptional activation domain of human p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29426–29432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S-H, Kim D-H, Han JJ, et al. Understanding pre-structured motifs (PreSMos) in intrinsically unfolded proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2012;13:34–54. doi: 10.2174/138920312799277974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunker AK, Babu MM, Barbar E, et al. What’s in a name? Why these proteins are intrinsically disordered. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. 2013;1:e24157. doi: 10.4161/idp.24157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: Introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tompa P, Han KH, Bokor M, et al. Wide-line NMR and DSC studies on intrinsically disordered p53 transactivation domain and its helically pre-structured segment. BMB Rep. 2016;9:497–501. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.9.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliezer D, Kutluay E, Bussell R, Jr, Browne G. Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1061–1073. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukrasch MD, Bibow S, Korukottu J, et al. Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi SW, Kim DH, Lee SH, Chang I, Han KH. Pre-structured motifs in the natively unstructured preS1 surface antigen of hepatitis B virus. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2108–2117. doi: 10.1110/ps.072983507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Lee SH, Nam KH, Chi SW, Chang I, Han KH. Multiple hTAFII31-binding motifs in the intrinsically unfolded transcriptional activation domain of VP16. BMB Rep. 2009;42:411–417. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2009.42.7.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, Cha EJ, Lim JE, et al. Structural characterization of an intrinsically unfolded mini-HBX protein from hepatitis B virus. Mol Cells. 2012;34:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue B, Blocquel D, Habchi J, et al. Structural disorder in viral proteins. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6880–6911. doi: 10.1021/cr4005692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C, Kim DH, Lee SH, Su J, Han KH. Structural investigation on the intrinsically disordered N-terminal region of HPV16 E7 protein. BMB Rep. 2016;49:431–436. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.8.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radhakrishnan I, Pérez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of CREB: A model for activator:coactivator interactions. Cell. 1997;91:741–752. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher CM, Wagner G. The interaction of eIF4E with 4E-BP1 is an induced fit to a completely disordered protein. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1639–1642. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramelot TA, Gentile LN, Nicholson LK. Transient structure of the amyloid precursor protein cytoplasmic tail indicates preordering of structure for binding to cytosolic factors. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2714–2725. doi: 10.1021/bi992580m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayers EW, Gerstner RB, Draper DE, Torchia DA. Structural preordering in the N-terminal region of ribosomal protein S4 revealed by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13602–13613. doi: 10.1021/bi0013391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chi SW, Lee SH, Kim DH. Structural details on mdm2-p53 interaction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38795–38802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lello Di P, Jenkins LMM, Jones TN, et al. Structure of the Tfb1/p53 complex: Insights into the interaction between the p62/Tfb1 subunit of TFIIH and the activation domain of p53. Mol Cell. 2006;22:731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bochkareva E, Kaustov L, Ayed A, et al. Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15412–15417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504614102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CW, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structure of the p53 transactivation domain in complex with the nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain of CREB binding protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9964–9971. doi: 10.1021/bi1012996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ha JH, Shin JS, Yoon MK. Dual-site interactions of p53 protein transactivation domain with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins reveal a highly convergent mechanism of divergent p53 pathways. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7387–7398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andresen C, Helander S, Lemak A, et al. Transient structure and dynamics in the disordered c-Myc transactivation domain affect Bin1 binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6353–6366. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim DH, Lee C, Cho YJ. A pre-structured helix in the intrinsically disordered 4EBP1. Mol BioSyst. 2015;11:366–369. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00532E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berlow RB, Dyson HJ1, Wright PE. Hypersensitive termination of the hypoxic response by a disordered protein switch. Nature. 2017;543:447–451. doi: 10.1038/nature21705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;240:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollenberg SM, Evans RM. Multiple and cooperative trans-activation domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell. 1988;55:899–906. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlman-Wright K, Almlöf T, McEwan IJ, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Delineation of a small region within the major transactivation domain of the human glucocorticoid receptor that mediates transactivation of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1619–1623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahlman-Wright K, Baumann H, McEwan IJ, et al. Structural characterization of a minimal functional transactivation domain from the human glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1699–1703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DH, Lee C, Lee SH, et al. The Mechanism of p53 Rescue by SUSP4. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:1278–1282. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh JA, Singh VK, Jia Z, Forman-Kay JD. Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between α- and γ-synuclein: Implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2795–2804. doi: 10.1110/ps.062465306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker JM, Hudson RP, Kanelis V, et al. CFTR regulatory region interacts with NBD1 predominantly via multiple transient helices. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:738–745. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X, Perugini MA, Yao S, et al. Solution conformation, backbone dynamics and lipid interactions of the intrinsically unstructured malaria surface protein MSP2. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almlöf T, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Role of hydrophobic amino acid clusters in the transactivation activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:934–945. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.2.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C, Kalmar L, Xue B, et al. Contribution of proline to the pre-structuring tendency of transient helical secondary structure elements in intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 20141840:993–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borcherds W, Theillet FX, Katzer A, et al. Disorder and residual helicity alter p53-Mdm2 binding affinity and signaling in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:1000–1002. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iešmantavičius V, Dogan J, Jemth P, Teilum K, Kjaergaard M. Helical propensity in an intrinsically disordered protein accelerates ligand binding. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:1548–1551. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.