Abstract

National implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides important lessons on the barriers and facilitators to implementation in a large healthcare system. Little is known about barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a complex EBP for emotional and behavioral dysregulation—dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). The purpose of this study was to understand VHA clinicians’ experiences with barriers, facilitators, and benefits from implementing DBT into routine care. This national program evaluation survey measured site characteristics of VHA sites (N = 59) that had implemented DBT. DBT was most often implemented in general mental health outpatient clinics. While 42% of sites offered all four modes of DBT, skills group was the most frequently implemented mode. Fifty-nine percent of sites offered phone coaching in any form, yet only 11% of those offered it all the time. Providers were often provided little to no time to support implementation of DBT. Barriers that were difficult to overcome were related to phone coaching outside of business hours. Facilitators to implementation included staff interest and expertise. Perceived benefits included increased hope and functioning for clients, greater self-efficacy and compassion for providers, and ability to treat unique symptoms for clinics. There was considerable variability in the capacity to address implementation barriers among sites implementing DBT in VHA routine care. Mental health policy makers should note the barriers and facilitators reported here, with specific attention to phone coaching barriers.

Keywords: US Department of Veterans Affairs, Dialectical behavior therapy, Implementation, Barriers, Phone coaching

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has made large investments in disseminating and implementing mental health evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) across the nation’s largest integrated healthcare system. To date, VHA has rolled out 15 EBPs nationally, including treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, sleep problems, chronic pain, and substance use [1]. Evaluation of the implementation of EBPs in VHA has identified barriers and facilitators. Provider attitudes influenced implementation; EBPs were delivered more often when clinicians perceived them as effective [2–4] and were delivered less frequently when clinicians believed that the treatments were ineffective or perceived clients would not tolerate them, such as with PTSD treatment [5]. The structure or characteristics of a clinic were also at times barriers to implementation, such as not being highly organized and structured [6], having a long waiting list [3], or being unable to schedule appointments for the necessary time frame [5, 7]. Facilitators to implementation included dedicated time, resources, sufficient staff, and mandates to deliver the EBP [2, 8]. As demonstrated in previous training literature, consultation (defined as ongoing feedback generally lasting 3 to 6 months, usually on taped clinical interactions, from an expert consultant) was key to changing provider behavior [1, 6, 9].

A number of these implementation barriers and facilitators are likely generalizable across EBPs as evidenced by their frequency in the literature, such as number of providers, time and resources, and training and consultation. Less is known about implementation barriers and facilitators in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) [10], a complex EBP with multiple treatment modes. DBT consists of four modes of treatment; these include weekly individual therapy, weekly skills group, weekly therapist consultation team meetings, and as needed phone coaching that can occur any time of day (including outside of business hours). The functions of phone coaching are to reduce suicidal behavior, increase skill generalization, and repair therapeutic relationship problems [10]. Treatment generally lasts 1 year (resulting in approximately 182 h of individual and group treatment per client) [10, 11].

Developed to treat severe emotion dysregulation and suicidal behavior, research has demonstrated DBT to be an effective treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD) [12]. In studies primarily with clients with suicidal behavior and BPD, DBT has also been proven to lead to a reduction in suicide attempts, non-suicidal self-injury, drug use, symptoms of eating disorders, and improvements in psychosocial adjustment and treatment retention [13]. To date, at least 11 randomized controlled trials have yielded evidence pointing to its effectiveness at reducing depression, hopelessness, anger, and impulsiveness (see summary in Landes and Linehan) [14]. There is emerging evidence that DBT skills group only (as opposed to full DBT that includes all four treatment modes) may be effective for treating individuals with BPD traits [15] and those with emotion dysregulation problems [16, 17].

Addressing impulsive behavior and suicidal behavior is critical in a veteran population where the prevalence rate of suicide is estimated to be higher than the general population [18]. DBT is effective at reducing suicidal ideation, hopelessness, depression, and anger expression with female veterans with BPD [19]. DBT is also helpful in decreasing male and female veterans’ utilization and cost of mental health services, including hospitalizations [20]. The most recent revision of the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense clinical practice guidelines for the assessment and management of clients at risk for suicide included DBT as a treatment recommendation [13].

Unlike treatments for disorders that are more prevalent in VHA such as depression and PTSD, DBT has not yet been disseminated nationally across VHA. The complexity and intensity of DBT does not fit easily into the routine VHA clinic structure and settings that are already understaffed to address more common mental health diagnoses. In a healthcare system working to increase veteran access to care, a more complex treatment that addresses a fewer number of clients may have lower priority with decision makers/clinical administrators. These important and well-known contextual issues in the VHA may impact decision making about DBT implementation and present additional barriers. However, DBT can be utilized for treating a smaller number of clients who require more intensive services or who may be utilizing a greater percentage of emergency and mental health resources [20, 21].

Current knowledge regarding the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of DBT are based on studies focusing only on providers who have received intensive training—a resource-intensive endeavor that is not always feasible in large healthcare settings [12] and who have implemented full DBT (e.g., all modes of DBT). Carmel et al. [22] interviewed 19 clinicians involved in a system-wide rollout of DBT in a public behavioral health system. Herschell et al. [23] interviewed 13 administrators from nine community-based mental health agencies involved in a county-wide implementation of DBT. Barriers identified in these two studies included personnel problems, issues related to program development, insufficient administrative support, and fit of DBT with established attitudes and practices.

Ditty and colleagues [24] surveyed 79 intensively trained providers in the community and interviewed a subset of 20 of those providers. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [25], they sought to identify inner setting constructs that appeared to be related to implementation of DBT. Inner setting constructs are the “structural, political, and cultural contexts” of the setting where implementation will occur. Ditty and colleagues found the following inner setting constructs to be possible facilitators to implementing DBT: stand-alone program settings, large size of treatment team, sufficient office space, high team cohesion and communication, culture/climate, and DBT supervision. In other words, settings with adequate resources and a relatively unified perspective to treating BPD were able to implement DBT. Through qualitative interviews with DBT team leaders from 68 teams across the UK, Swales and colleagues [26] identified barriers and facilitators contributing to DBT program sustainability. Much like the above, the primary barrier reported was lack of organizational support and, not surprisingly, the primary facilitator was organizational support.

While there is evidence available regarding clinic- and client-level benefits of DBT via clinical outcome and cost effectiveness studies (e.g., reduction in service utilization and cost and effectiveness data indicating symptom improvement), limited research has discussed benefits of DBT implementation at the provider level. Swales and colleagues [26] found that providers reported benefits such as personal utilization of DBT skills, improved team support, and increased respect from coworkers. In summary, some of the barriers, facilitators, and benefits of DBT are similar to themes seen in the general implementation research and VHA EBP rollouts described above, such as administrative support and access to training.

Given the sampling of intensively trained providers in the studies above, less is known about the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of DBT in routine care settings where there are often limited to no resources available for intensive training. Intensive training generally includes two 1-week trainings separated by a 6-month self-study and implementation period. In addition, existing research has only examined the presence or absence of barriers. One study was conducted with college counseling center staff who either were interested in or had implemented DBT. The authors found lack of individual therapists, productivity demands, limited time for team consultation, and lack of willingness to offer phone coaching to be the most highly endorsed barriers [27].

Less is also known about settings that have only implemented some of the modes of DBT. For example, some sites implement only the DBT skills group, which has increasing evidence to support its use as a stand-alone modality [15–17]. More information is also needed about implementation of another mode of DBT, phone coaching, when implementing a full program. Phone coaching in DBT is often a controversial topic, as it was designed to be offered outside of business hours (based on the therapist’s personal limits), with many providers offering access to phone coaching at all hours of the day (often referred to as 24/7) [10]. Instructional guidance is available to assist therapists in providing phone coaching [28–30] and yet, limited research on both the effectiveness and implementation of phone coaching is available. One study [31] found that more frequent calls were associated with a reduction in psychological symptoms and an increase in client and therapist satisfaction in a full DBT program with clients with BPD.

More research is needed to determine the value added of phone coaching to the full program of DBT. Ben-Porath [28] identified myths, fears, and anxieties that may prevent individual providers from using phone coaching and discussed solutions to these issues. Training evaluation data indicate that this mode of DBT may either be more difficult or take more time to implement. Data from one intensive training cohort of 14 teams from different settings (e.g., private practice and hospitals) in 2000, showed that only 29% of teams offered phone coaching at the end of intensive training and 43% offered it the following year (compared with skills group, where 79% offered it at the end of training and 86% offered it the following year) [32]. Data from more recent training cohorts including 52 teams suggests that more sites are implementing phone coaching following training, as one of the two DBT training companies reported that 75% of teams were offering all four modes of DBT following training [33].

In summary, there is existing evidence for intensively trained, highly resourced teams who provide full DBT and some emerging evidence that DBT is effective in decreasing treatment costs for veterans, skills group may be a stand-alone modality of treatment, and there remain ongoing challenges to phone coaching in routine care. However, relatively little is known about the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of DBT in VHA routine care settings.

Study aims

The current study aimed to identify VHA clinics’ experience implementing DBT in routine care settings and to describe sites’ experience with barriers, facilitators, and benefits of implementation. Identifying barriers and facilitators is an intermediate goal for a future aim of determining what implementation strategies should be used to address barriers and enhance facilitators.

METHODS

Study design

The quantitative data presented here is derived from a national program evaluation self-report survey. For a full description of methods for this study, see Landes et al. [34]; however, a brief overview is provided. This study was approved and monitored by the institutional review boards for the Palo Alto VA Health Care System and Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System.

Sample and procedures

A two-step purposive sampling process identified sites providing modes of DBT in the VHA healthcare system. First, the research team used a list of the clinical sites’ points of contact on a DBT resource Intranet website available to all VHA employees that included 60 contacts. The first author compiled the list prior to the study for practical purposes of increasing communication between sites offering DBT and aiding in making referrals for DBT within VHA. The list includes VHA sites offering any modes of DBT and includes VA medical centers, community-based outpatient clinics, and Vet Centers. Sites were identified for inclusion on the list by contacting known DBT providers in VHA, soliciting information about existing sites on the VHA national listserv for EBP coordinators, presenting at a VHA psychology leadership conference, and asking the two DBT training companies to share information about the VHA Intranet site with any of the VHA teams they trained. Instructions for how to get a site added to the list on the Intranet site accompanied the list. When adding a site, the person providing the information and/or the team at the site identified a point of contact to be listed. All 60 of these points of contact received an invitation to participate in this study. Next, in an effort to capture sites not listed on the Intranet website, using snowball sampling among their professional networks within VHA, the research team requested each of these individuals listed as points of contact to share the invitation with others known to use DBT to participate in the national program evaluation.

The research team sent potential respondents an e-mail invitation to participate in the survey that included an embedded link to the survey website. The survey was housed on a commercial web-based platform (i.e., Qualtrics Survey Software) [36]. The survey was voluntary and non-incentivized. The institutional review board approved a waiver of documentation of informed consent for this survey. Data collection occurred between July 2013 and May 2014.

The final sample size was 59 sites. There were a total of 67 unique survey responses; this included eight sites with more than one respondent. Sites were asked to have one survey completed for their site. When there were multiple surveys completed per site, data were combined so that each site had only one entry. Data combination was completed by a team of two raters and rules included averaging data when appropriate and when only one respondent completed an item, using that respondent’s data (data combination further described in Landes et al. [29]. Throughout this manuscript, when reporting what “clinical sites” reported, we are referring to either the survey responses from an individual at one site or, when there were multiple survey responses, the aggregate responses from each site.

VHA facility types included VA medical centers (VAMCs) that are large local or regional healthcare systems that may have multiple locations in a geographic area (e.g., in the New York City area, there are medical centers in the Bronx, Manhattan, etc., that are all part of one healthcare system) and community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) that are smaller satellite clinics to their affiliated VAMCs to increase access to care in surrounding areas. Vet Centers are community-based outpatient-counseling centers that are organizationally and physically separate from VHA facilities where eligible combat veterans and their families can go for a range of psychosocial services, to include readjustment counseling, military sexual trauma counseling, and bereavement counseling. At the time of data collection in 2013, VHA had a total of 168 VA medical centers and 1053 outpatient sites, which included both community-based outpatient clinics and Vet Centers. The 59 sites in this study included 53 VA medical center locations, six community-based outpatient clinics, and no Vet Centers. These sites represented 21 of the 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs; regions of care that include multiple medical centers, often spanning multiple states).

The training experience and training needs data collected in this survey have been previously reported [34]. Survey respondents completed a checklist of training activities completed by any member of their DBT team. Training activities were categorized as high (e.g., intensive training), medium (e.g., 1–2-day workshop), and low intensity (e.g., reading DBT books). Most sites reported engaging in low-intensity training activities. See Landes for more detail [34].

Measures

The survey included 81 items end-employed multiple formats including multiple choice (n = 22), Likert scaling (n = 42), ranking (n = 1), and check all that apply response options (n = 16). Open-ended text box responses were also provided for some items (n = 9) in order to solicit more descriptive information or comments from participants. The estimated time to complete the survey was 15–20 min based on user testing with VHA clinicians familiar with DBT.

Clinical site characteristics were assessed via questions about primary modes of DBT implemented, provider and mental health setting characteristics, including clinic type (response options included general outpatient mental health clinic, PTSD care team, inpatient, residential (defined as longer-term inpatient treatment), domiciliary (defined as residential rehabilitation and treatment services for homeless veterans with multiple and severe medical conditions, mental illness, addiction, or psychosocial deficits), and other), number of providers and full-time equivalent positions (FTE) available, the types of client problems and diagnoses for which DBT is used (see Table 1), and the approximate number of veterans and percentage of their client population receiving DBT in their setting.

Table 1.

Percentage of sites that endorsed each patient problem or diagnosis as appropriate for DBT in their setting (N = 59)

| Patient problems | Percent |

|---|---|

| Borderline personality disorder | 97 |

| Emotion regulation problems | 97 |

| Interpersonal difficulties | 95 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | 92 |

| Suicidal behavior | 90 |

| Impulsive behaviors | 88 |

| PTSD | 86 |

| Military sexual trauma (MST) | 85 |

| Depression | 80 |

| Bipolar disorder | 66 |

| Substance abuse | 63 |

| Disruptive behavior | 59 |

| Chronic pain | 39 |

| Eating disorder symptoms | 39 |

| Othera | 20 |

Note: Response options included check all that apply. Percentages do not add up to 100

aDescriptions of “other” patient problems included: anger (n = 2), anxiety disorder symptoms (n = 2), adult ADHD, chronic therapy interfering behavior (n = 1), homicidal ideation (n = 1), other cluster B pathology (n = 1), traumatic brain injury (n = 1), dissociative identity disorder (n = 1), other traumas (non-sexual and non-military) (n = 1), and veterans for whom other groups or treatments have not been successful previously (n = 1)

Barriers to implementation were assessed using a modified version of the DBT barriers to implementation (BTI) questionnaire [37], a checklist of commonly reported barriers created to assist trainers in understanding barriers faced by teams attending DBT trainings (α = .94). In trainings using the BTI, we received feedback that the questionnaire did not allow respondents to account for the dynamic change in barriers to DBT over the course of implementation. We modified the BTI to better capture clinicians’ experience in dealing with barriers by changing the response options from “yes” and “no” to “not a barrier/problem,” “a problem we overcame,” “a problem we are currently working on,” “a problem we could not overcome,” or “not applicable.” We removed items not relevant to VHA settings (e.g., problems with reimbursement) and added items that matched anecdotal reports of barriers in VHA (e.g., lack of resources for training; this was missing as the BTI was created for use at trainings). We also added four items specifically related to the availability of phone coaching when providers were willing; the original version had one item related to phone coaching and providers being “not willing to take phone calls or extend limits when needed.” New items addressed not being allowed to take calls during business hours, outside of business hours due to use of personal resources (e.g., phone), and outside of business hours due to use of personal time. A final item addressed lack of funding for calls. The final version of the BTI had 37 items.

Facilitators to implementation were assessed using a checklist developed for this study, based on previous DBT research (α = .82); 20 possible facilitators were listed. The response option for the facilitator checklist asked respondents to “check all that apply.” Benefits of implementation, also developed for use in this study, used a checklist of possible benefits of implementing DBT, including benefits to the client, provider, and clinic or system derived from the DBT literature and DBT training experience (α = .70); 21 possible benefits were listed. The response option for the benefits was check all that apply.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0 for Windows. We calculated descriptive statistics to include frequencies and means for the clinical sites, barriers, facilitators, and benefits to implementation. Clinical sites were divided into two groups, as either high adopters (implementing three or four modes of DBT) or low adopters (implementing one or two modes of DBT), for comparison. In order to determine whether these high and low adopting sites differed in their report of the number of difficult barriers, facilitators, and benefits based on the number of modes implemented, we conducted a one-way ANOVA. Some sites did not complete the entire survey; for items not completed by all 59 sites, the number of respondents was reported.

RESULTS

Modes of DBT implemented

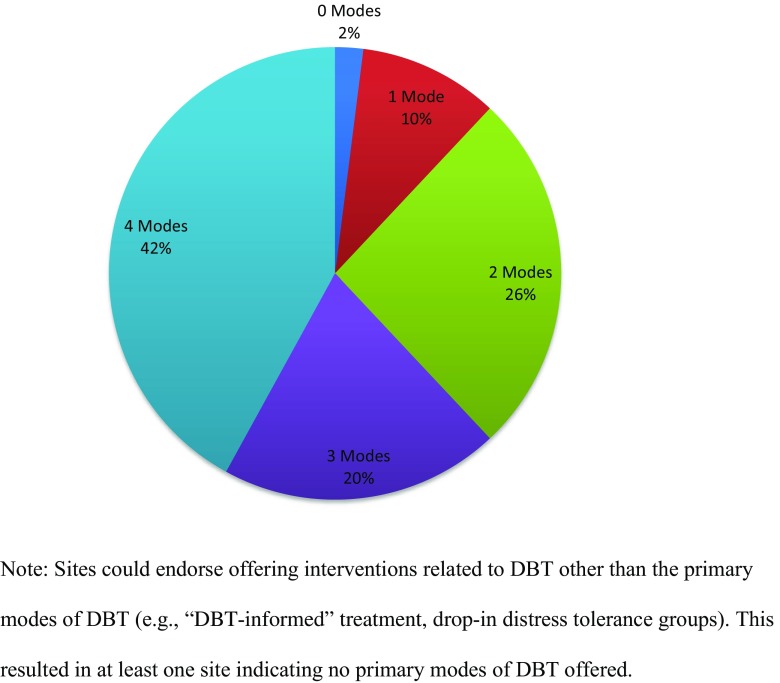

Skills group was the most commonly endorsed mode of treatment offered in VHA, with 98% of sites offering DBT skills group. This was followed by individual DBT therapy (75%), phone coaching (in any form or amount; 61%), and therapist consultation team (56%). Figure 1 presents the percentage of sites offering each total number of primary modes of DBT (e.g., the percentage offering all four primary modes versus those offering some of the primary modes). Less than half of the sites that completed the survey (42%) offered all four modes of DBT.

Fig 1.

Percentage of sites offering primary modes of DBT (skills group, individual therapy, therapist consultation team, and phone coaching)

Of the 35 sites that endorsed providing phone coaching in any form or amount, four endorsed offering it 24/7, 25 endorsed offering it during business hours, 10 endorsed that it depends on the provider’s personal limits, and three endorsed “others.”

Provider and setting characteristics

The number of VHA providers at each clinical site ranged from one to 20 (M = 5.18, SD = 3.77) and the modal number of providers per site was two (24% of the sites reported having two providers). Of those who answered the question about full-time equivalent positions (FTE; n = 50), the majority (63%) did not have any FTE allotted specifically for DBT. Of those who did report having dedicated FTE for DBT, the amount of FTE ranged from .10 to 3.0 (i.e., 1.0 FTE is the equivalent of one 40-h/week employee). The majority of sites identified as general outpatient mental health clinics (N = 38, 64%). Treatment setting of the remaining sites included the PTSD care team (n = 5, 9%), residential (e.g., trauma recovery program; n = 1, 2%), domiciliary (n = 1, 2%), and others (n = 13, 22%). Data were missing for one site. For those sites that chose others for treatment setting, text responses included the following types of settings: multiple settings (e.g., outpatient and inpatient mental health) (n = 8), mental health team in primary care (n = 2), women’s clinics (n = 2), and intensive outpatient for serious mental illness (n = 1).

Client population

Sites identified to whom they offer DBT or what types of client problems or diagnoses are appropriate for DBT in their setting. Table 1 presents the percentage of sites that endorsed each type of client problem or diagnosis; the most frequently endorsed problem or diagnosis included borderline personality disorder, emotion regulation problems, interpersonal problems, non-suicidal self-injury, and suicidal behavior.

Sites provided data on approximately how many veterans received DBT in their setting and the percentage of their client population that this figure represented. The number of veterans ranged from five to 80, and the average was 21.07 (SD = 14.35). The site with the highest number of veterans served (80) and was as a healthcare system with three clinic settings offering DBT. The percentage of sites’ clinic populations receiving DBT (e.g., for a mental health clinic, what percentage of the clinic population was receiving DBT) ranged from one to 75 and the average was 14.96% (SD = 20.42%). Given the skew of the data for the percentage of veterans, the mode may be most representative and was 1%.

Barriers to implementation

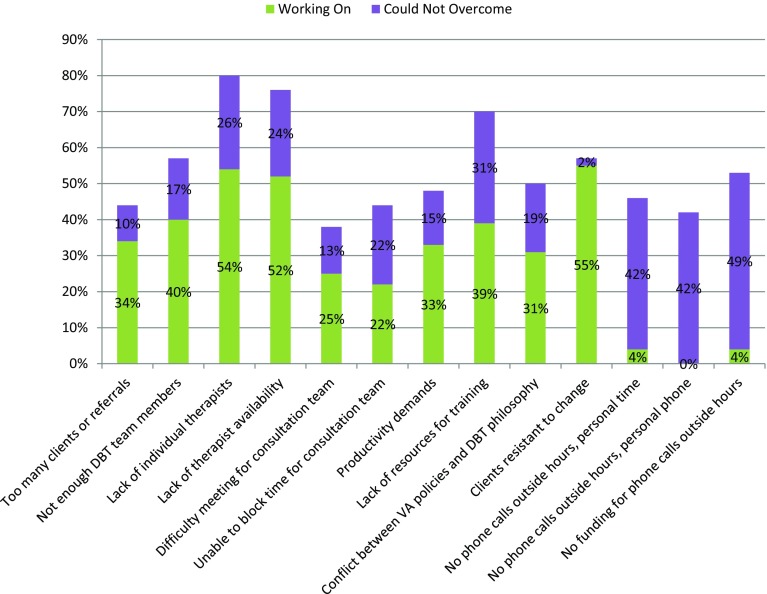

Table 2 lists each of the 37 DBT barriers and the percentage of sites that endorsed each as not a barrier, a barrier we overcame, a barrier we are working on, a barrier we could not overcome, and not applicable. To further investigate the most frequently endorsed difficult barrier items, we selected all items that were endorsed as either a barrier they were “working on” or “could not overcome” by at least one-third of the sample; this resulted in identification of 13 barriers (see Fig. 2). These 13 most difficult barriers were grouped into themes of number or availability of therapists or the ability to meet as a team (n = 7), difficulty with policies and/or lack of resources (n = 5), and clients’ expectations (n = 1). Of note, the three barriers rated as unable to overcome by the highest percentage of sites were all related to implementing phone coaching.

Table 2.

Barriers to implementing DBT collected using a revised barriers to implementation (BTI)

| Barriers | Not a barrier (%) | Overcame (%) | Working on (%) | Could not overcome (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team barriers | ||||

| Not enough DBT team members (n = 53) | 32 | 6 | 40 | 17 |

| DBT team members left (n = 52) | 44 | 17 | 19 | 4 |

| DBT team members did not get along (n = 52) | 64 | 10 | 8 | 0 |

| Conflict about leadership (n = 52) | 69 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| No designated DBT team leader (n = 52) | 56 | 8 | 14 | 6 |

| No formal commitment to learning, implementing DBT from some team members (n = 53) | 43 | 17 | 13 | 9 |

| Mandated rather than voluntary participation in training and program development (n = 53) | 60 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Difficulty meeting with each other/sporadic attendance at consultation meetings (n = 53) | 28 | 15 | 25 | 13 |

| Administrative barriers | ||||

| Change in administrator (from supportive to non-supportive) (n = 52) | 50 | 6 | 12 | 2 |

| Funding cut (n = 52) | 39 | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| Staff cut (n = 52) | 44 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Productivity demands (n = 52) | 29 | 10 | 33 | 15 |

| Lack of resources for training (n = 52) | 8 | 12 | 39 | 31 |

| Theoretical/philosophy barriers | ||||

| Difficulty adopting DBT assumptions (n = 52) | 46 | 14 | 27 | 0 |

| Difficulty adopting DBT team agreements (n = 52) | 50 | 12 | 15 | 6 |

| Problems buying into DBT biosocial theory (n = 52) | 69 | 2 | 19 | 0 |

| Discrepant theoretical orientations (n = 51) | 49 | 16 | 24 | 0 |

| Non-behavioral orientation (n = 52) | 46 | 15 | 27 | 0 |

| Non-dialectical orientation (n = 52) | 48 | 12 | 29 | 2 |

| Mindfulness viewed negatively or not adopted (n = 52) | 73 | 6 | 10 | 0 |

| Conflict between VA policies and DBT philosophy (n = 52) | 31 | 8 | 31 | 19 |

| Structural barriers | ||||

| Lack of individual therapists (n = 50) | 10 | 4 | 54 | 26 |

| Lack of therapist availability to take on enough patients (n = 50) | 12 | 6 | 52 | 24 |

| Lack of clients or referrals (n = 50) | 78 | 6 | 12 | 0 |

| Too many clients or referrals (n = 50) | 48 | 2 | 34 | 10 |

| Clients accustomed to treatment they have had and are resistant to change (n = 49) | 27 | 8 | 55 | 2 |

| Not a match for client problems or needs (n = 50) | 80 | 8 | 10 | 0 |

| Lack of physical space (e.g., group room with a table) (n = 49) | 65 | 16 | 12 | 4 |

| Lack of materials (e.g., binders for handouts) (n = 50) | 50 | 20 | 20 | 6 |

| Only one group leader allowed (n = 50) | 68 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Unable to schedule a 2-h group (n = 50) | 49 | 16 | 16 | 8 |

| Unable to have time blocked out for DBT consultation team (n = 50) | 32 | 18 | 22 | 22 |

| Phone coaching barriers | ||||

| Not willing to take phone calls or extend limits when needed (n = 50) | 36 | 6 | 14 | 12 |

| Not allowed or able to take phone calls for coaching during business hours (n = 50) | 50 | 4 | 16 | 6 |

| Not allowed or able to take phone calls for coaching outside business hours due to using personal time (n = 50) | 14 | 8 | 4 | 42 |

| Not allowed or able to take phone calls for coaching outside business hours due to using personal phone/physical resources (n = 50) | 18 | 6 | 0 | 42 |

| No funding available for phone calls for coaching outside business hours (n = 47) | 13 | 6 | 4 | 49 |

Indicate no for VA, yes generally for other settings. All barriers add up to 100% including N/A responses not included in the table above

Fig 2.

Most difficult to overcome DBT barriers endorsed by VHA clinical sites (N = 59) collected using a revised barriers to implementation (BTI)

The five barrier items related to phone coaching included one item related to providers not willing to take calls, three items related to providers not being able or allowed to take calls, and one item related to lack of funding for calls. Two of these barriers, provider unwillingness and not being able or allowed during business hours to take calls, were rated as not a problem for many of the sites (36 and 50%, respectively). In contrast, the barriers related to taking calls outside of business hours (due to using personal time and due to using personal phone/physical resources) and the barrier of lack of funding available for phone consultation calls outside business hours were all identified by many of the sites as barriers they were unable to overcome (42, 42, and 49%, respectively).

Nine barriers were rated as not a problem for at least 60% of sites. For example, “not a match for client problems or needs” was not endorsed as a barrier by 80% of sites, and “lack of clients or referrals” was not endorsed as a barrier by 78% of sites. Nine barriers were rated as a barrier that had been overcome by at least 15% of the sites. For example, the barriers “lack of materials (e.g., binders for handouts)” and “unable to have time blocked out for consultation team” were endorsed as barriers that had already been overcome by many sites (20 and 18%, respectively).

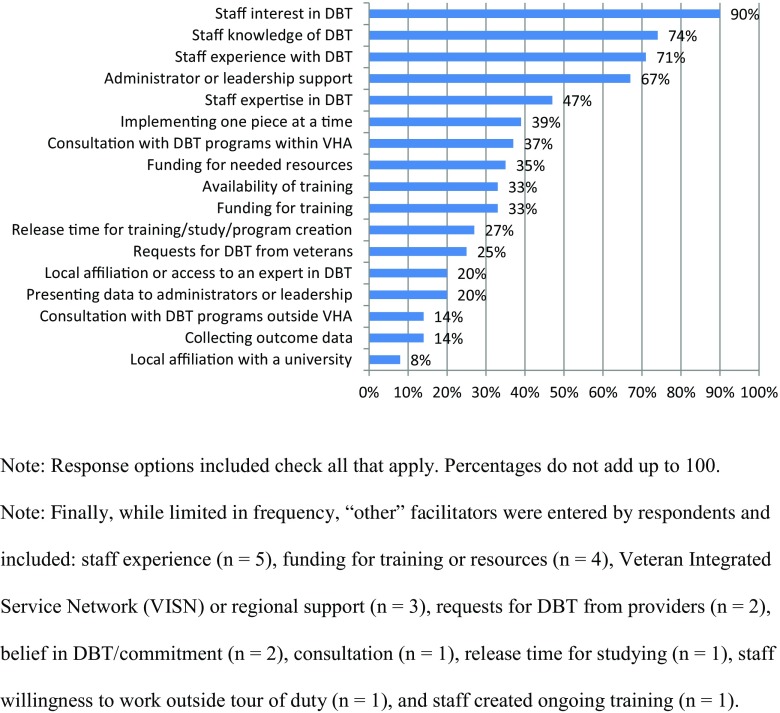

Facilitators to implementation

Figure 3 presents the assessed facilitator items and the percent (n = 49) of sites that endorsed each. Overall, the most frequently endorsed facilitators were staff interest (90%), knowledge (74%), and experience (71%) in DBT, followed by administrative or leadership support (67%).

Fig 3.

Percentage of DBT facilitators endorsed by VHA clinical sites (N = 49) collected using a checklist of possible facilitators created for this study

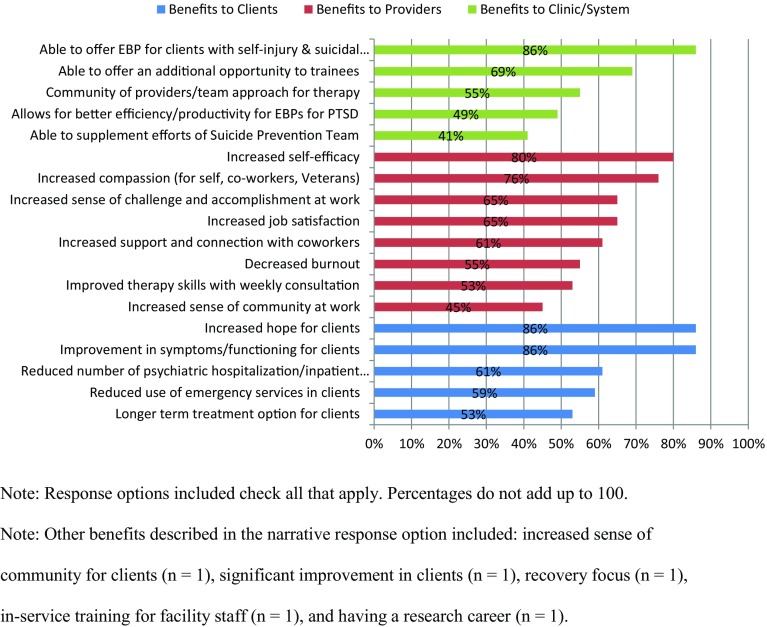

Benefits of implementing DBT

Figure 4 presents the benefits and percent of sites (n = 49) that endorsed experiencing benefits at the client, provider, and clinic/system levels due to implementing DBT. Overall, the most frequently endorsed benefits were improvement in symptoms or functioning for clients (86%), increased hope for clients (86%), and able to offer an EBP for clients with self-injury and suicidal behavior (86%).

Fig 4.

Percentage of DBT benefits endorsed by VHA clinical sites (N = 49) collected using a checklist of possible benefits created for this study

There were statistically significant differences between high and low adopting sites in terms of the number of barriers sites endorsed as difficult (F = 4.87, p = 0.03), how many facilitators they endorsed (F = 6.89, p = 0.01), and how many benefits they endorsed (F = 7.12, p = 0.01). Low adopters endorsed more barriers as difficult (M = 13.07) than high adopters (M = 9.05). High adopters endorsed a greater number of both facilitators (M = 8.18) and benefits (M = 13.27) than did low adopters (M = 5.78 and M = 10.15, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to describe the informal implementation of DBT in routine care across the VHA healthcare system. In contrast to previous literature on DBT implementation, this study was conducted in routine care settings and did not exclude sites with providers who had not received intensive training [22–24, 26]. While some sites did report having intensively trained providers, most sites endorsed low-intensity training activities such as reading the DBT manual or other related books [34].

This study found that DBT in the VHA is implemented most often in general mental health clinics, yet a number of sites reported that DBT is offered across a number of settings or teams (e.g., outpatient mental health and a substance abuse clinic or outpatient and inpatient mental health). This expansion to other clinics may be to address a shortage of staff members available to implement DBT in a single clinic or to enhance continuity of care across clinics through collaboration. Most sites reported that they had little to no provider time allotted specifically for DBT in terms of dedicated FTE; however, this finding was expected for an EBP implemented at a grassroots level. With regard to the type of veteran client populations receiving DBT in these settings, the most frequently endorsed clinical issues were the types of problems that DBT was designed to treat, including BPD, emotion regulation problems, and suicidal behavior. Overall study findings indicated that DBT was used for the appropriate populations and that these types of client problems are present in the participating VHA clinics.

Forty-two percent of sites endorsed offering all four primary modes of DBT. Of the primary modes, skills group was the most frequently implemented. This may be because therapy groups are common in VHA or because skills group can be the easiest mode to implement with limited resources (e.g., one or two interested clinicians with limited time can facilitate a group). Given recent data on the effectiveness of DBT skills group as a stand-alone treatment [15–17], more evaluation of client and systems level or implementation outcomes at VHA sites offering skills group only or not offering full DBT would be helpful to further extrapolate the client-, provider-, and clinic-level barriers and facilitators to implementing DBT within specific VHA clinics or outside traditional acute care hospital settings (e.g., CBOCs or Vet Center community settings).

With regard to another mode of DBT, our survey asked whether or not sites offered phone coaching in any amount or form (as opposed to 24/7 availability of phone coaching suggested by Linehan [10]). Subsequent questions further clarified when phone coaching was available and allowed for collection of information on the variability of how phone coaching was implemented in VHA. Results indicated that only 11% of sites with phone coaching offered it 24/7 and 29% reported offering based on the provider’s personal limits (e.g., outside of business hours, but not between midnight and 6 am). The majority (71%) offered phone coaching during business hours.

Results of the study also provide more detailed information on sites’ experience with barriers and their ability to overcome barriers, as they were able to rate barriers as not a problem or as a problem we overcame. The barriers identified as difficult (rated as a problem we are working on or a problem we could not overcome) could be areas that require additional support. These might be issues that could be addressed by changes in policy (e.g., regarding use of phone coaching outside of business hours, cost of overtime, and workload credit) that could be addressed in possible future national rollouts of DBT. Future research should focus on the longitudinal experience of dealing with barriers; this could inform future implementation plans and possibly highlight areas in need of additional implementation supports or clarify expectations on the length of time needed to address barriers.

The current survey highlighted a number of barriers related to a specific mode of DBT, phone coaching. As described above, 35 sites offer phone coaching in any form or amount, but only four sites offer phone coaching with fidelity to the treatment protocol. To our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically focused on barriers related to phone coaching when providers are willing to do phone coaching. Provider unwillingness and not being able or allowed to do phone coaching during business hours were not a problem for many sites. During business hours, client phone calls are documented and coded as a clinical activity, resulting in providers receiving productivity credit. This may reduce barriers to receiving or returning calls during business hours. The most difficult barriers to phone coaching involved policies (working outside of business hours and using personal resources such as a phone) and funding. Funding is defined here in two ways, funds for salary to pay providers for offering phone coaching outside of their normal business hours (e.g., overtime pay) or as funding for tangible resources (e.g., a VHA-provided cell phone). Implementation strategies to address these barriers likely require leadership support, such as a medical center’s chief of staff for mental health or even at a higher level (e.g., at a regional level or VHA wide), and need to address more system-level issues. When moving toward policies or system-level changes, it may be helpful to consider phone coaching as care management that improves client care and reduces the need for emergency services. Additional research on VHA-specific barriers, the generalizability of these barriers to other non-VHA sites, and the impact of the absence of phone coaching on clinical outcomes is greatly needed.

A number of previously identified barriers to implementing DBT in other settings were confirmed in VHA routine care settings, such as personnel problems [22, 23, 26], insufficient administrative support or resources [22, 23, 26], referral problems, and fit of DBT with existing attitudes and practices [23, 26]. Barriers not previously identified in DBT research included those related to inability to incorporate DBT modes such as consultation team and phone coaching with policies and clinical procedures. Similarly, some previously identified facilitators were reinforced in the current study (e.g., sufficient staff, sufficient resources [24]). Lastly, three new facilitators were identified in this study (i.e., gradual implementation, consultation with other existing DBT programs, and client requests for DBT). Future research on barriers and facilitators to EBP implementation may benefit from examining them on a continuum (e.g., leadership support is a variable that impacts implementation and lack of it would be rated as a barrier and presence of it would be rated as a facilitator) as opposed to examining them via two separate measures.

With regard to the benefits of providing DBT, these results confirm previous findings that DBT providers report both perceived personal and professional benefits to implementing DBT (e.g., increased support from team) [26]. The results further describe the client-level (e.g., improvement in symptoms and reduced use of emergency services) [13, 19, 20] and provider-level (e.g., decreased burnout) [26] benefits that are demonstrated in clinical efficacy and effectiveness studies and cost-effectiveness studies. In addition to providing information on the benefits of DBT implementation at the VHA, these data also have the potential to serve as preliminary evidence for other VHA sites by identifying what benefits might be expected from the delivery of this intervention. This information may be especially useful to decision makers, as it provides a fuller picture of the impacts of implementation and may offer information to justify costs needed to implement DBT.

When comparing high adopters (those sites that had implemented at least three of the four modes of DBT) to low adopters (those that had implemented only one or two modes), there were significant differences in the number of difficult barriers, facilitators, and benefits. High adopter sites endorsed fewer barriers as difficult and endorsed a greater number of facilitators and benefits of implementation than low adopter sites. Given the lack of longitudinal data, it is possible that high adopter sites have been implementing DBT for a longer period and therefore have overcome more barriers, resulting in fewer barriers rated as working on or could not overcome. It is reasonable that sites offering more modes of the treatment (and therefore implementing the program with fidelity to the model) would endorse more benefits of implementation. Overall, this study offered a number of client-, provider-, and clinic or system-level experiences and actionable recommendations for overcoming barriers, increasing facilitators, and the benefits of implementing DBT in VHA routine care settings.

Future directions

A few models of implementation demonstrate how to use implementation information such as barriers strategically. These include the availability, responsiveness, and continuity [38] model; getting to outcomes [39]; and the evidence-based quality improvement model [40]. However, many published studies have not clearly described the process of how barrier data is used and how it may be maximized to address barriers, to identify appropriate implementation strategies, and to move a system to implementation [41]. The next needed step following this national program evaluation is to systematically identify a limited number of implementation strategies best suited to address the barriers identified, especially those rated as difficult to overcome. The research team plans to use the methodology from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project [42, 43] to match barrier and facilitator data to implementation strategies and create a list of relevant implementation strategies to be provided to and discussed with our DBT key stakeholders and policy makers. This method allows for consideration of such factors as setting and context, constructs important in a number of theoretical frameworks, including the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [25] and the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (iPARIHS) framework [43].

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. First, the study sample may not capture a comprehensive and current view of DBT implementation in VHA. At the time of recruitment, 60 sites had been identified in VHA as offering modes of DBT. However, sites who have faced more barriers or who were unable to overcome barriers and no longer offer modes of DBT would not have been identified, and therefore, not invited to participate. Second, data were collected for each site based on one survey (e.g., one person reported for an entire site). This may have resulted in biased or incomplete data, given that others at the same site may have different perspectives. Third, the results of the current analyses are based on survey response, and therefore they are susceptible to the limitations associated with self-report data. In addition, the measures used in the survey were either created as practical tools for trainers or for the purpose of this study and may not be psychometrically sound. Work is currently underway to further examine the psychometric properties and to improve the BTI based in part on these results (Chugani, personal communication, 21 August 2016). The BTI was originally created by a training company that trains teams primarily working with civilian populations; future work should examine possible differences between settings and the barriers that should be assessed. Fourth, since barriers were assessed in a one-time survey format, they are limited in complexity, as we have no data about how the barriers changed over time or how long it took for a site to overcome a barrier. Finally, more sites at VHA medical centers participated than did those located in outpatient clinics or Vet Centers. While this may limit the generalizability of the findings to sites at community-based outpatient clinics or Vet Centers, it makes sense that not many sites participated, as many do not have specialty mental health services available and/or have few mental health staff.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study is the first known study to examine barriers, facilitators, and benefits of implementing DBT in routine care settings across the national VHA healthcare system. Participants were not limited to intensively trained providers or sites only implementing all modes of DBT, which may have allowed for a fuller picture of what occurs in real-world implementations. In VHA, not all sites offering DBT had implemented all four modes of treatment; skills group was the only mode of treatment implemented in the majority of sites (98%). Of sites offering phone coaching, only 11% were offering it as intended (24/7). In VHA, DBT was most often implemented in general mental health outpatient clinics with little to no time allocated specifically for providers to implement DBT for clients with symptoms appropriate for DBT. VHA clinical sites reported varying ability to overcome barriers related to implementing DBT. The barriers rated as difficult to overcome were related to being allowed to or having the funds to implement phone consultation outside of the provider’s normal business hours. Future research on DBT is needed not only on the specific modes of treatment but also system-level implementation over time that strategically addresses barriers and accentuates benefits for the healthcare system, providers, and ultimately provides quality, accessible, and timely mental healthcare services to all veterans who could benefit from this complex EBP.

Acknowledgements

The results described are based on data analyzed by the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Veterans Health Administration (VHA), or the US Government.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Mental Health Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (MH QUERI) QLP 55-055 awarded to the first author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The findings reported in this manuscript have not been previously published and the manuscript is not being simultaneously submitted elsewhere during the Translational Behavioral Medicine review process. Portions of the data reported in this manuscript have previously been presented at conferences for the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration in September 2015 and the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies in November 2015. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested and will do so in accordance with data sharing guidelines within the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Implications

Policy: Mental health leaders who have the ability to impact and inform policy should consider policy changes that would help address the barriers rated as difficult to overcome by clinical sites.

Research: Additional work is needed to systematically identify implementation strategies best suited to address the barriers identified, especially those rated as difficult to overcome.

Practice: Clinic administrators and clinical providers can use the barriers and facilitators described here to plan for implementing dialectical behavior therapy in their setting.

References

- 1.Karlin BE, Cross G. From the laboratory to the therapy room: national dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. Am Psychol. 2014;69:19–33. doi: 10.1037/a0033888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finley EP, Garcia HA, Ketchum NS, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Stirman SW, et al. Utilization of evidence-based psychotherapies in Veterans Affairs posttraumatic stress disorder outpatient clinics. Psychol Serv. 2015;12:73–82. doi: 10.1037/ser0000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osei-Bonsu PE, Bolton RE, Wiltsey Stirman S, Eisen SV, Herz L, Pellowe ME. Mental Health providers’ decision-making around the implementation of evidence-based treatment for PTSD. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11414-015-9489-0. Accessed 11 Feb 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ruzek JI, Eftekhari A, Crowley J, Kuhn E, Karlin BE, Rosen CS. Post-training beliefs, intentions, and use of prolonged exposure therapy by clinicians in the Veterans Health Administration. Adm. Policy Ment. Health. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hamblen JL, Bernardy NC, Sherrieb K, Norris FH, Cook JM, Louis CA, et al. VA PTSD clinic director perspectives: how perceptions of readiness influence delivery of evidence-based PTSD treatment. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46:90–96. doi: 10.1037/a0038535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts BV, Shiner B, Zubkoff L, Carpenter-Song E, Ronconi JM, Coldwell CM. Implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies for posttraumatic stress disorder in VA specialty clinics. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2014;65:648–653. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen CS, Crowley J, Eftekhari A, Kuhn E, Smith BN, Trent L, et al. Sustained use of evidence-based psychotherapy by graduates of the prolonged exposure training program. Philadelphia, PA; 2015.

- 8.Cook JM, Dinnen S, Thompson R, Ruzek J, Coyne JC, Schnurr PP. A quantitative test of an implementation framework in 38 VA residential PTSD programs. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015;42:462–473. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlin BE, Ruzek JI, Chard KM, Eftekhari A, Monson CM, Hembree EA, et al. Dissemination of evidence-based psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:663–673. doi: 10.1002/jts.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993.

- 11.Landes SJ, Garovoy ND, Burkman KM. Treating complex trauma among veterans: three stage-based treatment models: complex trauma. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:523–533. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landes SJ, Linehan MM. Dissemination and implementation of dialectical behavior therapy—an intensive training model. Dissem. Implement. Evid.-Based Psychol. Interv. Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 187–208.

- 13.Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. The clinical practice guideline for the assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide [Internet]. 2013. Available from: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/suicideRisk.asp.

- 14.SAMHSA. National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices [Internet]. 2013. Available from: http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/.

- 15.Chugani CD, Ghali MN, Brunner J. Effectiveness of short term dialectical behavior therapy skills training in college students with cluster B personality disorders. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2013;27:323–336. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2013.824337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neacsiu AD, Eberle JW, Kramer R, Wiesmann T, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy skills for transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2014;59:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uliaszek AA, Wilson S, Mayberry M, Cox K, Maslar M. A pilot intervention of multifamily dialectical behavior group therapy in a treatment-seeking adolescent population: effects on teens and their family members. Fam J. 2014;22:206–215. doi: 10.1177/1066480713513554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Veterans Affairs. Suicide among veterans and other Americans 2001–2014 [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf.

- 19.Koons CR, Robins CJ, Lindsey Tweed J, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, Morse JQ, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. 2001;32:371–390. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80009-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers LL, Landes SJ, Thuras P. Veterans’ service utilization and associated costs following participation in dialectical behavior therapy: a preliminary investigation. Mil Med. 2014;179:1368–1373. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amner K. The effect of DBT provision in reducing the cost of adults displaying the symptoms of BPD: Karen Amner. Br J Psychother. 2012;28:336–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0118.2012.01286.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmel A, Rose ML, Fruzzetti AE. Barriers and solutions to implementing dialectical behavior therapy in a public behavioral health system. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. [Internet]. 2013. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10488-013-0504-6. Accessed 19 May 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Herschell A, Kogan J, Celedonia K, Gavin J, Stein B. Understanding community mental health administrators’ perspectives on dialectical behavior therapy implementation. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:989–992. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ditty MS, Landes SJ, Doyle A, Beidas RS. It takes a village: a mixed method analysis of inner setting variables and dialectical behavior therapy implementation. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10488-014-0602-0. 16 Apr 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swales MA, Taylor B, Hibbs RA. Implementing dialectical behaviour therapy: programme survival in routine healthcare settings. J Ment Health. 2012;21:548–555. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2012.689435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chugani CD, Landes SJ. Dialectical behavior therapy in college counseling centers: current trends and barriers to implementation. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2016;30:176–186. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2016.1177429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ben-Porath DD. Intersession telephone contact with individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder: lessons from dialectical behavior therapy. Cogn Behav Pract. 2004;11:222–230. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80033-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Porath DD, Koons CR. Telephone coaching in dialectical behavior therapy: a decision-tree model for managing inter-session contact with clients. Cogn Behav Pract. 2005;12:448–460. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80072-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manning SY. Common errors made by therapists providing telephone consultation in dialectical behavior therapy. Cogn Behav Pract. 2011;18:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chalker SA, Carmel A, Atkins DC, Landes SJ, Kerbrat AH, Comtois KA. Examining challenging behaviors of clients with borderline personality disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796715300437. Accessed 22 Oct 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Landes SJ, Linehan MM, DuBose AP, Comtois KA. Dialectical behavior therapy intensive training model & initial data. Presentation at the Seattle Implementation Research Conference. Seattle, WA; 2011.

- 33.Harned M. Current trends in DBT research. Presentation at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Improvement and Training of DBT. New York City, NY; 2016.

- 34.Landes, S. J., Matthieu, M. M., Smith, B. N., Trent, L. R., Rodriguez, A. L., Kemp J., & Thompson, C. (2016). Dialectical behavior therapy training and desired resources for implementation: results from a national program evaluation in the veterans health administration. Mil Med, 181, 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Qualtrics Software [Internet]. Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2015. Available from: http://www.qualtrics.com.

- 36.Behavioral Tech, LLC. (n.d.). DBT barriers to implementation survey. Unpublished instrument. Behavioral Tech, LLC.

- 37.Glisson C, Schoenwald SK. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Ment Health Serv Res. 2005;7:243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinman M, Imm P, Wandersman A, RAND Corporation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Getting to outcomes 2004: promoting accountability through methods and tools for planning, implementation and evaluation [Internet]. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corp. 2004. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/TR101CDC. Accessed 29 Apr 2016

- 39.Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, Altschuler A, DePillis E, Hernandez J, et al. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1009–1029. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.63.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, et al. Expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC): protocol for a mixed methods study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement. Sci. [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.implementationscience.com/content/10/1/109. Accessed 7 Dec 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Harvey G, Kitson AL. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. 2015.