Abstract

Empirical evidence demonstrates myriad benefits of breastfeeding for mother and child, along with benefits to businesses that support breastfeeding. Federal and state legislation requires workplace support for pumping and provides protections for public breastfeeding. Yet, many are unaware of these laws, and thus, support systems remain underdeveloped. We used a community-based approach to spread awareness about the evidence-based benefits of breastfeeding and breastfeeding support. We worked to improve breastfeeding support at the local hospital, among local employers, and throughout the broader community. Our coalition representing the hospital, the chamber of commerce, the university, and local lactation consultants used a public deliberation model for dissemination. We held focus groups, hosted a public conversation, spoke to local organizations, and promoted these efforts through local media. The hospital achieved Baby-Friendly status and opened a Baby Café. Breastfeeding support in the community improved through policies, designated pumping spaces, and signage that supports public breastfeeding at local businesses. Community awareness of the benefits of breastfeeding and breastfeeding support increased; the breastfeeding support coalition remains active. The public deliberation process for dissemination engaged the community with evidence-based promotion of breastfeeding support, increased agency, and produced sustainable results tailored to the community’s unique needs.

Keywords: Public deliberation, Breastfeeding, Community-based participatory research, Health communication

Although breastfeeding is associated with a host of positive health outcomes for babies and mothers [1], rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration have risen in recent years but still fall significantly below US national goals [2]. Breastfeeding reduces the risk of infant mortality; rates of respiratory and ear infections; and risk for chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cancer. In addition, mothers who breastfeed have lower risks of breast and ovarian cancer [1]. Many health organizations recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of a baby’s life [3–5]. The US federal-level initiative, “Healthy People 2020,” has set goals for breastfeeding rates at 81.9% of babies being breastfed at any point, and 25.5% exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months. In South Dakota, 77% of mothers initiate breastfeeding, but only 15.9% exclusively breastfeed at 6 months [4].

Breastfeeding initiation and duration improve when women have comprehensive breastfeeding support in their communities [6]. A supportive community culture acts synergistically with other efforts to increase breastfeeding rates [7]. The sense of support is driven by specific types of community interaction such as facilitative dialogue and authentic support clearly communicated to all stakeholders [8]. Public deliberation is a process that engages community members to identify community needs, assets, and goals; it encourages dialogue between stakeholders and helps local communities generate unique and sustainable actions for enhancing breastfeeding support, and then prioritizing those approaches [9].

Public deliberation for breastfeeding support

Public deliberation is a unique way to disseminate research about a health issue. It dynamically shares highly tailored information with a community in order to produce actions that generate sustainable change. In this article, we report on the process and outcomes of conducting a public deliberation for the health issue of workplace breastfeeding support within a small, Midwestern community in South Dakota.

Breastfeeding support in the workplace

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life and continued breastfeeding up to a year [3, 4]. The World Health Organization and UNICEF also recommend continued breastfeeding up to 2 years or beyond [5]. Because of these recommendations, the US Affordable Care Act includes a provision to support working mothers who breastfeed, by requiring employers to provide adequate time and space to pump breast milk for up to a year after the baby is born [10]. However, even with this federal law, many women still face challenges combining breastfeeding and work. For example, employers may be unaware of the law or unwilling to provide accommodations [11]. It may also not be socially normative to combine breastfeeding and work, so breastfeeding mothers may not feel supported [12]. Breastfeeding initiation and duration improve when women have comprehensive breastfeeding support in their communities, including the workplace [6]. Thus, increasing community support—especially at work—is essential to improving breastfeeding outcomes. However, since breastfeeding is still sometimes considered a taboo topic of conversation, particularly at work [13, 14], dissemination of information about breastfeeding must be sensitive to respect and incorporate the perspectives of community members, even while encouraging the community to make or adopt changes related to the health issue. A public deliberation can work well for a taboo issue, because it prioritizes the issue for the community and provides a collaborative space to gather and work through the issue, without taking a pre-determined stance on the best way for the community to approach the issue [9].

Public deliberation

Public deliberation is a communication process that empowers community members to identify and frame a problem of shared concern, and then discuss that problem through an organized process, with a focus on acknowledging different perspectives, benefits and tradeoffs of potential approaches, and values that may be in tension [9]. Ultimately, public deliberation seeks to work through the problem and potential actions, equipping the public to choose pathways forward. Public deliberation processes recognize that there may be deep differences between participants, leading some to frame public deliberation as “a rowdy affair” [15, 16]. Public deliberation events typically use some sort of neutral facilitator or moderator to encourage deeper, more robust conversation around a particular problem and potential approaches [9, 17].

Public deliberation can be more effective for disseminating health information than traditional approaches to dissemination [18]. Often, health communication or public health interventions for dissemination draw upon community perspectives in order to guide message design for predetermined health behavior changes [19], e.g., smoking cessation. Dissemination through a public deliberation approach differs from these approaches in two important ways. First, a public deliberation approach adds an emphasis on a deep understanding of the disseminated information, achieved through dynamic deliberative processes. Second, it leaves the end-goal of the dissemination open-ended but focuses on actions that are dependent on the deliberative choices of the community and their agency to enact those changes.

Public deliberation encourages the public to deeply understand information related to complex public health issues, or “wicked problems,” which are challenging, important, public concerns that impact many stakeholders [20]. With that understanding, participants can then determine together how to respond to that issue. Examples of wicked problems in healthcare may include issues such as the growth of obesity, increased rates of HIV infection, mental health concerns, or how to care for the elderly. In public deliberation, the entire community can engage with the process and together work through the major challenges around the issue and consider various approaches to overcoming those challenges [9, 21]. This collaborative process requires the research team to build community relationships with diverse stakeholders prior to, during, and after the public deliberation event that encourage lateral participation in the process. Relationship-building requires interpersonal communication, which thrives when both parties have shared interests, honestly share their experiences with each other, and are willing to listen to other points of view [22]. Community members build and strengthen relationships through interactions at a public deliberation; research team members draw upon relationships to engage opinion leaders and diverse stakeholders throughout the public deliberation event process.

Public deliberation also emphasizes decision-making and actions that further disseminate the information from the event. Moving beyond understanding, public deliberation prioritizes public choice-work [23]. This distinguishes public deliberation from similar approaches like participatory communication that foreground creating connections and coalitions [24] but emphasize dialogue, rather than public deliberation, as the central communication process that facilitates decision-making [25]. Additionally, public deliberation focuses on generating collective and individual actions to address health concerns, unlike similar “communities of practice” that also use dialogue to seek to understand complex issues but stop short of committing to action [26]. Commitment to action continues after the event and again highlights the importance of relationships to a public deliberation model for dissemination. Following the diffusion of innovation model [27], community members who attend the public deliberation serve as innovators and early adopters who interpersonally communicate through their social networks to further disseminate new information about an important health topic [28].

To successfully conduct a public deliberation event about a “wicked” health problem that is also a taboo topic of communication, research teams must carefully prepare for, plan, organize, and follow-up on the public deliberation event. The planning and preparation process typically takes 6 months to 1 year prior to the scheduled event. Execution of each public deliberation event takes about 2–3 days (encompassing training facilitators and hosting the event). Follow-up takes about 2 months for initial follow-up and then continues indefinitely. This type of approach is greatly aided by securing financial support to cover the materials, supplies, and human resources needed to accomplish such an event. In our case, we received a Community Innovation grant from the Bush Foundation to support planning and executing the event.

Method

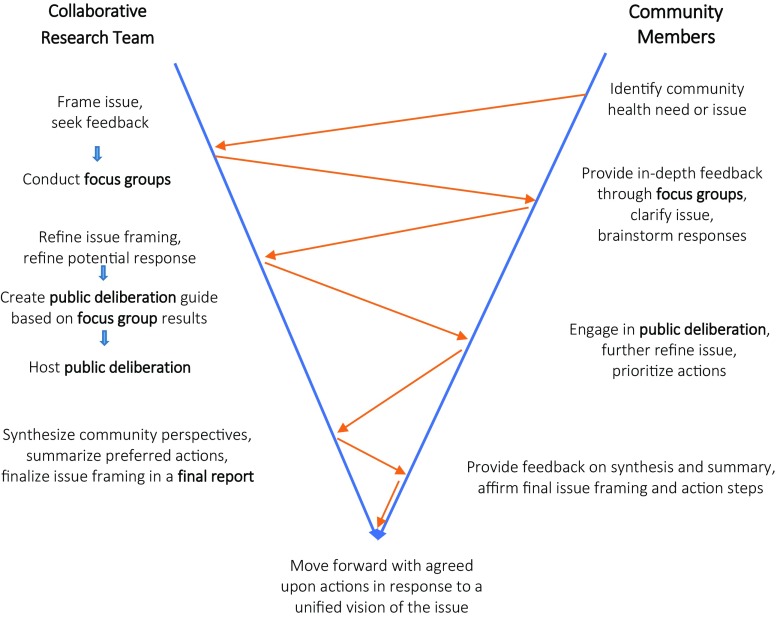

In the next two sections, we provide in-depth details about how practitioners can plan, organize, and follow-up with a public deliberation event. Public deliberation is an important way to disseminate health information to a community to encourage collective and individual health-related actions (see Fig. 1). A simplified review of this methodology is already published [29].

Fig. 1.

Iterative process of using public deliberation for dissemination. Note: This figure appears in Anderson, Kuehl, and Drury (2017) [29]

Plan for the deliberation

Build a coalition

Our grant team included individuals with a wide range of areas of expertise, including faculty researchers from disciplines such as communication and nursing, health practitioners and leaders such as the director of public relations and marketing and the director of the obstetrics (OB) unit, community members who were certified lactation consultants, and community members who were affiliated with the local chamber of commerce. These grant team members’ diverse experiences with breastfeeding support—especially across the different contexts of the university, hospital, and community—reinforced the complexity of the issue and emphasized how important it was to include myriad stakeholders across the development of the entire project. The connections between the university, the chamber of commerce, and the hospital were vital to being able to reach the desired stakeholders for our public deliberation event, including groups such as business leaders, human relations professionals, breastfeeding employees, and community health advocates.

Conduct formative research

Before planning and hosting the public deliberation event, however, we conducted focus groups to hear about community members’ experiences with breastfeeding support in our community. Focus groups offer a space for participants to share common experiences, piggy-back off of others’ ideas, build relationships, and—because we held separate groups for mothers and business representatives—feel more comfortable talking about a taboo topic [30]. With assistance from our grant team members affiliated with the area chamber of commerce, as well as our community lactation consultants and health practitioners, we recruited participants and held six focus groups in our community—three with breastfeeding mothers (n = 28) and three with business representatives (n = 23). Community members completed informed consent prior to participation. Some of the shared focus group topics discussed by both breastfeeding mothers and business representatives included breastfeeding experiences, challenges to breastfeeding support in the workplace, ideas for community actions, and community assets to enhance breastfeeding support [13, 29].

Create a public deliberation guide

The results from the formative research were used to develop a public deliberation guide, which defines and frames the health issue for the public deliberation event. To develop the guide, the entire team used the focus group transcripts and informal field notes to generate themes that represented community experiences with the issue. To formalize the themes, the expert moderator (see below) led the entire research team through a half-day data conference, where the team ultimately articulated the major aspects of the problem and the three major approaches to the issue that were then used at the public deliberation event. We use the language of “approaches” rather than solutions, because the term “solutions” may connote that a solution offers a quick “fix” to the issue, whereas the term “approach” emphasizes potential actions that can improve a complex issue but will not entirely fix it.

Organize the deliberation event

Hire an expert moderator

An expert moderator is an important asset for a public deliberation. Our moderator worked with the coalition team to frame the public issue through analyzing formative research, trained facilitators for the event, and led the public deliberation event as a whole while facilitators guided conversations at smaller tables. At the event, the moderator provides a roadmap and instructions for participants and facilitators to know where the conversation will go next. As tables deliberate, the moderator walks around the room and seeks feedback from different tables, summarizing and paraphrasing participants’ contributions to share with the entire group at various points during the public deliberation. Our group hired a moderator without ties to the community, so that the moderator had distance from the community and felt comfortable articulating potentially unpopular or uncommon perspectives that may not have appeared in formative research or may not have been represented at the event.

Train facilitators

The outside moderator trained facilitators who would lead the discussions at the individual tables at the public deliberation event. For our public deliberation, the outside moderator held a 3-hour training session that covered the basics of public deliberation, how to address wicked community problems that do not have simple answers, how to encourage participation from diverse stakeholders, and how to take notes that would be useful for reporting on the public deliberation. Facilitators observed and participated in a mock public deliberation. Approximately 25 students and community members participated in the training.

Publicize the event

With assistance from the director of public relations and marketing at the hospital, two communication faculty spoke to eight different community organizations about the upcoming public deliberation event during the couple of months prior to the event [31]. Additionally, these presentations received a wide range of media coverage through radio, television, print, and online news, including in local, state, and regional outlets [29]. Beyond news coverage, the project was also featured on each of the community partner’s websites and social media pages, through a TEDx talk, as well as on various breastfeeding-related websites [31].

Provide participants with information

Each participant received a folder with information on the issue that included general information and information tailored to the community. For example, each participant received a bookmark detailing the benefits of business support for breastfeeding. The folders also contained an event schedule, the entire public deliberation guide created by the team for the event, with an overview of the results from the focus group, and information about the follow-up event to be held within 6 weeks of the event. On the cover of the guide, we included the overarching question for the public deliberation: “How can our community support the breastfeeding experience in Brookings businesses?” On the tables, each participant also received a one-page overview of the aspects of and approaches to the problem; these were the topics of discussion at the event.

Collect information

At the event, n = 38 participants completed informed consent, then completed pre- and post-test surveys measuring perceptions of breastfeeding support and intentions to enact change. Ten tables participated in the public deliberation. Participants also recorded commitments to individual actions on post-it notes. At each table, notetakers recorded major points of discussion on large poster boards during the event; at the conclusion of the event, facilitators and notetakers completed brief questionnaires to summarize themes in the conversations. These data were used to generate the final event report, on which the event outcome results section is based. After the event, field notes were used to record changes in breastfeeding support in our community.

To determine outcomes from the event, the researchers used data from the participant surveys, transcripts of the table conversations, responses on the notetaker questionnaires, notes from the tables’ large poster boards, participants’ individual post-it notes, and the researchers’ own field notes. It is important to gather various forms of data for two reasons. First, multiple data points allow for triangulation of results, improving the validity of the conclusions. Second, many times, the people attending a public deliberation are already invested enough in the issue that a pre- and post-event survey may not show significant changes in knowledge, attitudes, or intentions. Thus, it becomes imperative to use other types of data, like field notes and other artifacts from the event. But, the most important thing to analyze is the interactions that occur at the public deliberation. Within these conversations is evidence of subtler changes in deep understanding or capacity-building.

Changes in understanding are often observed when participants make comments such as “Now I understand what people mean when they talk about…” or “I had never thought of it that way.” Capacity-building can be observed when analyzing conversations between different types of stakeholders; it often occurs when participants share information that can lead to actions. For example, one employer might talk about a policy they enacted. Then, another participant says, “Can I have a copy of that to share with my employer?” Or, a lactation consultant explains the physical demands of pumping breast milk and returning to work. Then, a human resources representative says, “that information will help me make a case for creating a lactation room at our company.” The interactions at the public deliberation event provide evidence of key outcomes.

Results

By using an expert moderator and trained facilitators to guide the discussion, the public deliberation event successfully disseminated information about the state of breastfeeding support in the community, the specific challenges related to it, and potential approaches. Our results demonstrate event and post-event outcomes.

Event outcomes

Understanding the issue

During the event, facilitators led participants in dynamic, interactive conversations at each table. Participants spent considerable time and energy unpacking the problem itself and considering different specific approaches to it (see Fig. 2). The participants used the public deliberation guide—based on formative research in the community—to unpack the problem, even challenging or refining results from formative research, similar to the process of member-checking [30]. The descriptions in the guide generally resonated with participants’ experiences and knowledge. In particular, they felt that the problem of a lack of breastfeeding support boiled down to problems with dissemination of information about breastfeeding challenges and supports. They specifically noted that businesses are unaware of the benefits of breastfeeding; employers, friends, and families do not understand the challenges of breastfeeding; and there is limited public awareness of general breastfeeding benefits.

Fig. 2.

Community members discuss breastfeeding at the public deliberation event

Next, the outside moderator and table facilitators led participants through each of the three approaches on the public deliberation guide. The three approaches emphasized the importance of disseminating accurate information to the right audiences. The first approach prioritized education specifically for business owners and managers who may be unaware of the federal guidelines for workplace breastfeeding support. The participants brainstormed options for dissemination, such as billboards, workshops, trainings, and a repository for businesses to share model policies. In addition, participants felt that government support for this approach would increase its potential success. However, participants highlighted funding concerns, a difficulty in knowing how to reach the right audience, and uncertainty regarding who would be responsible for creating and delivering content.

The second approach focused specifically on developing business resources. Participants prioritized top-down approaches to building business support in this community, noting that if a few larger or influential businesses could get on board as innovators, then other, smaller businesses might follow suit as early adopters [27, 28]. However, they noted that not all businesses prioritize this issue, and noted a lack of incentive for creating or sharing policies. Finally, the third approach aimed at broader culture change, so that the community would have a supportive culture. Actions related to this approach included educating businesses; normalizing breastfeeding through increased visibility and discussions; and having comprehensive, collaborative, and continuous breastfeeding support. Challenges to this approach included determining the right pace, finding leadership to implement these changes, and being sensitive to those who do not breastfeed, because they may be unintentionally alienated or stigmatized.

Participants were then encouraged not only to brainstorm actions but to consider who might implement them and whether those actions were short- or long-term approaches to the problem. In this way, participants were required to apply the information they had gained from the early part of the public deliberation, so that they could better act upon that information in the future. This personalization of disseminated research increases participants’ involvement with the issue [32] and enhances their ability to act on this information by adapting their health behaviors or becoming advocates for this taboo issue. A greater understanding of the issue also led many participants to describe feeling more comfortable talking about breastfeeding in mixed company or at work; after the public deliberation event, the subject seemed less taboo.

Prioritized community actions

After the small groups at the tables discussed each approach, the moderator reconvened participants as a large group and asked each table to prioritize one short-term and one long-term action and identify who in the Brookings community could lead that action. The actions might not have represented each participant’s first choice, but they were actions that had broad agreement (although not necessarily consensus) at the table. Each table had a large poster with possible community actions, and then noted their prioritized actions during this step. These posters, with prioritized actions noted, were then hung on the wall of the event for all participants to view (see Fig. 3). The prioritized actions fell into two major themes: business-related actions and public/community-related actions.

Fig. 3.

Prioritized approaches from each table discussion at the public deliberation event

Participants prioritized three specific business-related actions: (1) developing and disseminating tools for mothers and employees, (2) helping businesses create policy regarding lactation rooms, and (3) establishing a permanent group to provide education and support to businesses and the community. Participants also prioritized three specific community-related actions: (1) creating a logo and designation for “breastfeeding-friendly businesses,” (2) creating a visual breastfeeding campaign, and (3) providing individualized support to breastfeeding mothers. These actions represented careful, thoughtful responses to a very difficult problem that is often considered a taboo subject for conversation. This topic required intensive communication-based efforts in order for the dissemination of information to be highly impactful.

Personal commitments to action

Similar to the prioritized community actions, each participant committed to an individual action. Participants wrote this action on a post-it note and could share it with their table. Then, participants publicly committed to this action by placing their post-its on the wall for other participants to see as they left the event. One of the most common actions was interpersonal-level dissemination; in other words, participants committing to sharing the information from the event with their friends, family, and co-workers. Participants were especially keen to share information via “word-of-mouth” or simply talking more about this issue with others in the community. For a taboo topic like breastfeeding, commitments to increasing communication about the issue are an extremely important outcome that can lead to the type of culture change that participants discussed during the public deliberation. Many participants also expressed a desire to provide direct support to breastfeeding mothers, whether as a spouse, a co-worker, a friend, or simply a community member who notices and encourages a breastfeeding mother. Public deliberation is a form of dissemination that sparks further dissemination through informal, interpersonal channels that are essential to the long-term success of community-based health initiatives [27].

Post-event outcomes

Following the event, many collective and individual changes took place in the community. Perhaps the most striking health-related outcome to occur during this time was the increase in breastfeeding rates observed at the hospital. In conjunction with the public deliberation event and other community changes during this time, the hospital achieved important milestones related to the prioritized community-based action of “providing individualized support to breastfeeding mothers.” Without any external funding for their maternity care initiatives, the hospital achieved the Baby-Friendly Hospital designation and started a Baby Café, which provides no-cost breastfeeding support from nurses who are certified lactation consultants. As a result of these synergistic efforts, the OB director at the hospital (M. Schwaegerl, written communication, June 2016) reported the rates of breastfeeding initiation jumped from 87 (in 2012) to 95% (in 2015). An even larger improvement was observed for the 2-day post-discharge rate of exclusive breastfeeding, which jumped from 68 (in 2012) to 95% (in 2015). This improvement over a short time span speaks to not only the hospital’s efforts to improve breastfeeding support but also to the improved climate of community support that is crucial to continued breastfeeding.

Follow-up event

About 6 weeks after the public deliberation event, our team held a follow-up event for community members interested in carrying out the prioritized actions. The event was attended by a small number of committed community members who reviewed the final report, created plans to achieve actions, and designated specific community members to lead different efforts. However, after the follow-up event, the bulk of the responsibility for carrying out actions remained with the community coalition members who had planned and executed the public deliberation. Community members who were enthusiastic at the follow-up event, and continue to show informal support through social media or interpersonal interactions, nevertheless did not commit to the continued action needed to achieve the goals. The coalition, representing leaders across the community on the issue, continues to work to implement the community-prioritized action plans to support breastfeeding practices.

Community coalition activity

The prioritized action of “establishing a permanent group to provide education and support to businesses and the community” has been largely realized through the “Brookings Supports Breastfeeding” community coalition. The coalition began as a research team formed to plan and execute the public deliberation. Now in its third year, the group has shifted both in membership and responsibilities, although it retains representation from the university, the hospital, and the chamber of commerce. It now functions as a vital force in organizing and executing breastfeeding support in the community. Specifically, the team maintains a Facebook page which allows for continued dissemination of information about breastfeeding support to about 500 followers. For example, when a local grocery store put in a new mother’s room for employees and customers, we shared pictures from their Facebook page to ours. We also shared the 2015 state legislation protecting women who breastfeed in public. In addition, community members reach out to our team directly through Facebook with questions about breastfeeding support in their organizations, and we are able to provide them with information and direct them to additional resources.

The coalition, and particularly its online presence, also shapes cultural norms for breastfeeding support. Members of our coalition routinely meet with local businesses to provide feedback on their policies or procedures related to breastfeeding support for employees and customers, especially regarding lactation rooms. Additionally, promotion for the event and related social media activities has also increased media coverage about breastfeeding. As the public conversation has shifted, community members—even those who did not participate in the event—remark that the community seems more supportive of breastfeeding than a few years ago.

Local business changes

In the year following the public deliberation, many businesses and organizations made strides in their breastfeeding support. A local mother who attended the public deliberation immediately installed a breastfeeding area for the bi-monthly meeting of Mothers of Preschoolers (MOPS). Another public deliberation attendee, the South Dakota State University Vice President for Human Resources, took personal action by revising the employee breastfeeding policy and increasing the availability of lactation rooms on campus.

Sometimes, business changes after the event were prompted by personal relationships with coalition members within the context of a shifting community culture. For example, one coalition member’s spouse works for a large manufacturer, who had become aware of the need for breastfeeding support due to the publicity around the event. The coalition member shared information with the manufacturer, which led to the creation of a lactation room for employees. Another coalition member disseminated information about lactation rooms to a friend that runs a local business, that business put in a lactation room. That business owner then spoke with the architect who was responsible for building the new university football stadium; her advocacy prompted the architect to include a lactation room in the stadium. Thus, personal relationships were central to larger-scale changes; the public deliberation provided coalition members with specific information to disseminate and gave them specific actions to take to improve support.

Breastfeeding-friendly business initiative

A representative from the South Dakota State Health Department (SDDOH) attended the public deliberation and shared with her colleagues the prioritized actions of “helping businesses crate policy regarding lactation rooms,” “developing and disseminating tools for mothers and employees,” “creating a logo and designation for ‘breastfeeding-friendly businesses,” and “creating a visual breastfeeding campaign.” About 6 months after the public deliberation event, the SDDOH piloted a breastfeeding-friendly business initiative, which addressed these prioritized actions, with our community. We decided to partner with the SDDOH, because the initiative aligned with our community’s prioritized actions and because the leadership of the SDDOH addressed the challenges of a lack of funding, materials, and human resources to accomplish this task.

The initiative took about 10 months to develop and 2 months to execute. We invited businesses to become “breastfeeding-friendly,” meaning that they would provide breastfeeding support for employees and customers in accordance with state and federal laws. They are also encouraged to display a window cling with a visual logo that designates the business as breastfeeding-friendly with the international breastfeeding symbol (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Breastfeeding-friendly business initiative window cling

At a pledge signing event, representatives from the three major industries represented on the coalition signed the breastfeeding-friendly pledge (see Fig. 5). Five additional businesses that are community opinion leaders also signed the pledge at this event. Then, students canvassed local businesses and had a 73.4% success rate. Businesses could also take the pledge online. As a result of the initiative, over 100 businesses are now breastfeeding-friendly. The SDDOH has begun implementing a similar initiative in other communities across the state.

Fig. 5.

Breastfeeding-friendly business initiative pledge signing event

Conclusions

Public deliberation is a unique way to disseminate research about a health issue that creates a dynamic opportunity for community members to engage with health information in ways that improve understanding and encourage action. In this case, the public deliberation’s emphasis on the wicked problem of breastfeeding support improved community understanding about workplace breastfeeding support—both generally and specifically in our community. The public deliberation guide, based on the results of formative research, allowed the research team to punctuate general information about breastfeeding support with specific anecdotes and narrative evidence from the community. Grappling with the problem through public deliberation produced deep, personal involvement with the issue, which generates action. The conversations at the public deliberation event helped diminish the taboo of talking about breastfeeding, because they focused on clear, honest communication in a setting that fostered interpersonal relationships. The relationships built at the event continued to exert influence as opinion leaders connected with social networks to diffuse the information from the event and enact change.

Limitations

A successful public deliberation is not without limitations. First, with this dynamic approach, community involvement will ebb and flow, and the coalition’s composition will change over time, which can challenge the continuity of efforts. One way to address this challenge is to establish a smaller core of team members who are committed to long-term engagement and to welcome involvement from new team members. Second, a public deliberation event requires a major investment of time and energy. These events are best suited for communities where there are already some passionate individuals or groups who serve as “resources for collaborative action” and would be willing to assist the deliberation conveners in planning, promoting, and executing the event [9]. Similarly, public deliberation planning should draw upon the resources of the community to plan and execute the event. For planning, it is important to build a coalition with diverse expertise and strong community connections. A strong coalition will include a public deliberation expert. Many universities now have centers for public deliberation and dialogue; these centers can provide expert moderators and many other resources for teams new to the process of public deliberation. For execution, draw upon local advocates and/or local students (high school or university students) to serve as facilitators or notetakers at the event.

Third, while event promotion is crucial for attracting participation from diverse stakeholders, it may have unanticipated consequences [29]. In our case, promotional efforts were so comprehensive that many community members felt informed about the issue prior to the event; some even began to enact changes without attending. This decreases the quality of the public deliberation conversations, because those engaged community members’ voices were not present at the event. One way to address this challenge is to focus promotional efforts on the necessity of community involvement with the public deliberation—rather than focusing on the health issue or event itself. This could be done through marketing efforts that emphasize (a) the multi-faceted nature of the issue, (b) the need to hear input from various stakeholders, (c) the information-sharing that occurs between stakeholders, and (d) the opportunity for networking with stakeholders that have the power to drive community action on the issue.

Best practices

Based on this study’s findings, we offer three strategies for successfully using public deliberation to disseminate health information: (1) plan, (2) organize, and (3) follow-up. First, a successful planning phase begins with creating a community coalition, then involves the community through formative research that will guide the event, and ends with comprehensive promotion that invites diverse stakeholders to attend the event. Second, to successfully organize the event, create a conversation guide that integrates formative research from the community with more general evidence-based information about the topic, train facilitators to guide the conversation at the event, and hire an expert moderator who can smoothly manage the entire event. Third, since public deliberation is designed to produce action, following-up on the event is crucial. Successful follow-up must include creating an accessible final report on the event’s outcomes, careful record keeping of the changes enacted in response to the event, and maintaining multiple outlets for communication between the community and the coalition.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics statement

All research procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the local university and were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This project was supported by a 2014 Community Innovation grant from the Bush Foundation (no grant number available).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Community-based efforts to address complex health issues need to engage community members in meaningful conversations to build understanding and create the relationships needed to generate and sustain positive change.

Policy: Funders and policymakers need to allocate resources and seek partnerships to support ongoing public deliberations that address complex health concerns at a community level, to create unique, sustainable solutions.

Research: Researchers should give greater attention to the communicative processes that drive community-level change for health behaviors, like breastfeeding, which require community support to be successful.

Contributor Information

Jenn Anderson, Phone: 605-688-6131, Email: Jennifer.Anderson@sdstate.edu

Charlotte Bachman, Email: njoy2day@swiftel.net.

Marilyn Hildreth, Email: Marilyn.Hildreth@gmail.com.

References

- 1.León-Cava N, Lutter C, Ross J, Martin L. Quantifying the benefits of breastfeeding: 2012 a summary of the evidence. PAHO Document Reference Number HPM/66/2. 2016. Available at http://www.ennonline.net/quantifyingbenefitsbreastfeeding2. Accessibility verified June 27, 2016.

- 2.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention. 2016 Healthy People 2020 Breastfeeding Objectives; 2010 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/policy/hp2020.htm. Accessibility verified June 27, 2016.

- 3.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence R, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Ped. 2005;115(2):496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016 Breastfeeding report card: United States 2014. 2015. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm. Accessibility verified June 27, 2016.

- 5.World Health Organization. 2016 Exclusive breastfeeding for six months best for babies everywhere. 2011. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/. Accessibility verified June 27, 2016.

- 6.Kornides M, Kitsantas P. Evaluation of breastfeeding promotion, support, and knowledge of benefits on breastfeeding outcomes. J of Child Health Care. 2013;17:264–273. doi: 10.1177/1367493512461460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sikorski J, Renfrew MJ, Pindoria S, Wade A. Support for breastfeeding mothers: a systematic review. Ped & Peri Epi. 2003;17:407–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmied V, Beake S, Sheehan A, McCourt C, Dykes F. Women’s perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support: a metasynthesis. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care. 2011;38:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carcasson M, Sprain L. Beyond problem solving: reconceptualizing the work of public deliberation as deliberative inquiry. Commun Theory. 2016;26(1):41–63. doi: 10.1111/comt.12055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division. 2016 Section 7(r) of the Fair Labor Standards Act—break time for nursing mothers protection. Available at http://www.dol.gov/whd/nursingmothers/Sec7rFLSA_btnm.htm. Accessibility verified June 27, 2016.

- 11.Chow T, Fulmer IS, Olson BH. Perspectives of managers toward workplace breastfeeding support in the state of Michigan. J Hum Lact. 2011;27(2):138–146. doi: 10.1177/0890334410391908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koerber A. Breast or bottle? Contemporary controversies in infant-feeding policy and practice. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson J, Kuehl RA, Drury SAM, et al. Policies aren’t enough: the importance of interpersonal communication about workplace breastfeeding support. J Hum Lact. 2015;31(2):260–266. doi: 10.1177/0890334415570059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatrell CJ. Secrets and lies: breastfeeding and professional paid work. Soc Sci & Med. 2007;65(2):393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivie R. Rhetorical deliberation and democratic politics in the here and now. Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 2002;5(2):277–285. doi: 10.1353/rap.2002.0033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asen R. Deliberation and trust. Argumentation and Advocacy. 2013;50:2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillard K. Envisioning the role of facilitation in public deliberation. J of Applied Communication Research. 2013;41:217–235. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2013.826813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abelson J, Eyles J, McLeod CB, Collins P, McMullan C, Forest PG. Does deliberation make a difference? Results from a citizens panel study of health goals priority setting. Health Policy. 2003;66(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho H, editor. Health communication message design: Theory and practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, McGivern G, Dopson S, Bennett C. Making wicked problems governable? The case of managed networks in health care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabatchi T. An introduction to deliberative civic engagement. In: Nabatchi T, Gastil J, Weiksner GM, Leighninger M, editors. Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCornack S. Reflect & Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication. 4. Bedford/St. Martin’s: Boston, MA; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makau JM, Marty DL. Dialogue & Deliberation. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao HA. Toward an epistemology of participatory communication: a feminist perspective. Howard J Commun. 2006;17(2):101–118. doi: 10.1080/10646170600656854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsen TL. Participatory communication for social change: the relevance of the theory of communicative action. Communication Yearbook. 2003;27:87–124. doi: 10.1207/s15567419cy2701_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boster FJ, Kotowski MR, Andrews KA, Serota K. Identifying influence: development and validation of the connectivity, persuasiveness, and maven scales. J of Communication. 2011;61(1):178–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01531.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson J, Kuehl RA, Drury SAM. 2017 Blending qualitative, quantitative, and rhetorical methods to engage citizens in public deliberation to improve workplace breastfeeding support. In SAGE Research Methods Cases Part 2. doi:10.4135/9781473953796

- 30.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuehl RA, Drury SAM, Anderson J. Civic engagement and public health issues: Community support for breastfeeding through rhetoric and health communication collaborations. Commun Q. 2015;63(5):510–515. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2015.1103598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson BT, Eagly AH. Effects of involvement on persuasion: a meta-analysis. Psyc Bull. 1989;106(2):290–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]