Abstract

For research to be useful, trustworthy, and ultimately lead to greater dissemination of findings to patients and communities, it is important to train and mentor academic researchers to meaningfully engage community members in patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR). Thus, it is necessary for research institutions to strengthen their underlying infrastructure to support PCOR. PATIENTS—PATient-centered Involvement in Evaluating effectiveNess of TreatmentS—at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, focuses on improving PCOR methods and addressing health disparities. It relies on evidence-based engagement methods to sustain and leverage innovative partnerships so patients, health care providers, and academic partners are motivated to participate in the conduct and dissemination of PCOR. Program components address training needs, bi-directional engagement, cultural competency, and dissemination and implementation. Activities (guided by community representatives, leadership from university schools, patient advocates, and PCOR experts) include providing resources, conducting PCOR projects, engaging community members, and disseminating PCOR findings. With its emphasis on the broad range of PCOR topics and methods, and through fostering sustainable relationships with community members and researchers, PATIENTS has successfully cultivated bi-directional partnerships and provided operational and scientific support for a new generation of skilled PCOR researchers. Early evidence of effectiveness includes progress in training and mentoring students and investigators, an increase in submission of PCOR proposals, and community-informed strategies for dissemination. Programs such as PATIENTS reinforce the value of bridging the traditional divide between academia and communities to support patient- and community-engaged dissemination and implementation research and foster sustainable PCOR infrastructure.

Keywords: Community-engagement, Patient-centered outcomes, Dissemination research, Comparative effectiveness research

BACKGROUND

Despite important breakthroughs and advances, communities with disparities in health outcomes have not received the full benefits of clinical research, even among subgroups with equal access to care [1]. One reason for persistent health inequities may be the use of research methods that traditionally distance the researcher from communities of interest, decreasing the likelihood that outcomes are relevant to patients or that findings will be effectively disseminated or implemented [2]. Indeed, the rate of translating research findings into community settings has been “inefficient and disappointing” when utilizing the traditional research model [3]. This paradigm’s lack of success in addressing complex health disparities is linked to researchers’ lack of understanding of the social and economic realities that motivate individuals’ and families’ behaviors, and to inadequate study designs that fail to incorporate multi-level explanations of health or perspectives of all stakeholders. When researchers have incorporated the community, it is often not truly participatory, but rather “community-placed” research, with community members as passive participants [1].

A shift in paradigm is required to foster research that serves the needs of patients, builds on the strengths of people and their communities, and draws on their capacity for problem solving. The onus is on researchers to gain trust and acceptance within the community and to demonstrate commitment to collaboration and shared decision-making. Unfortunately, due to entrenched and traditional research approaches, there is a lack of infrastructure to train researchers in methods for meaningful engagement to incorporate the voices of the patient, community, and other healthcare stakeholders. In response, the field of patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) seeks to identify and reinforce patient and stakeholder engagement throughout the research continuum, including the prioritization of research questions, study design and implementation, verification of results, and translation of findings.

To address the lack of research infrastructure and insufficient PCOR skills, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) established a 5-year effort to enhance and expand the existing capacity of emerging academic and applied research organizations, under Section 6301(b) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Initiated in 2013, the overarching goal of this initiative was to strengthen researchers’ methodological expertise in comparative effectiveness research (CER) through the conduct of research projects and other professional development activities, and to reinforce the underlying institutional infrastructure needed to support PCOR, particularly in regions that serve predominantly minority populations. In this paper, we describe the context and design of PATIENTS (PATient-centered Involvement in Evaluating the effectiveNess of TreatmentS), an awardee under this initiative, and introduce the reader to methods and activities to build a skilled PCOR community. We reflect on experiences implementing this innovative capacity building project, and present preliminary evidence of success. Discussion of preliminary findings is coupled with observations on lessons learned in developing innovative research partnerships, expanding PCOR capacity, and disseminating findings, for potential application to future projects of a similar nature.

The PATIENTS program

The University of Maryland, Baltimore, established PATIENTS (PI:C. Daniel Mullins), with a broad focus on building institutional and community capacity to address research topics relevant to reducing health disparities. PATIENTS is implemented in West Baltimore, Maryland, one of Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods, which has faced historical injustice, economic and health disparities, and is the scene of recent political and social unrest. This community is predominantly African-American (94%), bears a disproportionate burden of chronic illness, and its residents die from nearly every major disease at substantially higher rates than the city as a whole—nearly double the rate from heart disease, more than double the rate from prostate cancer, and triple the rate from AIDS. Life expectancy for residents is 68 years, more than 10 years below the state average [4, 5]. These persistent disparities underscore the importance of collaborating with local partners who can best represent the cultural, social, and health concerns and priorities of West Baltimore residents. Four individual investigator sub-projects related to the applicant’s thematic research focus were also funded through this grant.

PATIENTS seeks to accomplish its capacity building aims through community engagement methods that leverage innovative partnerships among academic researchers, patient communities, and healthcare systems. Partnerships are further reinforced by providing CER/PCOR training and resources to both academic and community members to foster co-learning and capacity building. As such, PATIENTS augments the goals of the AHRQ initiative by incorporating community and multi-stakeholder engagement principles to bring patients, communities, and other stakeholders from the margin to the center of the research enterprise. The program accomplishes this by employing the 10-step CER/PCOR framework [6], which illustrates how patient engagement can be applied throughout the research continuum, from topic solicitation and framing of the research question to translation and dissemination of Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) findings. By implementing the 10-step framework in the PATIENTS infrastructure and supported studies, academic researchers embrace the role of patients and other stakeholders as co-developers.

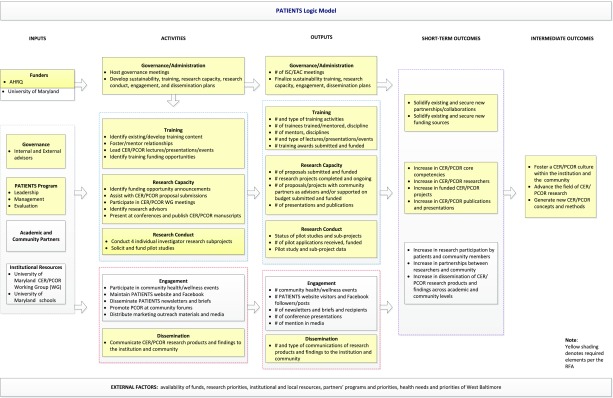

In addition to the program components required under the grant (governance and administration, training, research capacity building, conduct of research, and dissemination), PATIENTS’ vision that “Patients and stakeholders are heard, inspired, and empowered to co-develop patient-centered outcomes research” led to inclusion of engagement as the sixth core component (see Fig. 1, PATIENTS Program Logic Model). Community engagement is “a process of inclusive participation that supports mutual respect of values, strategies, and actions for authentic partnership of people affiliated with or self-identified by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of the community of focus” [7]. These engagement methods require authentic, bi-directional partnerships to gain trust and build mutual interest in improving the research process, and to make dissemination and implementation strategies more effective by helping researchers understand the needs, priorities, values, and assets of the community [8, 9].

Fig 1.

PATIENTS Program Logic Model

METHODS

Below, we describe PATIENTS’s governance and administrative structure, evaluation, activities to build PCOR capacity, and approach to community-based outreach and dissemination.

Governance/administration

The PATIENTS governance structure, under the direction of C. Daniel Mullins, PhD, at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, includes two leadership committees. The Internal Steering Committee (ISC) is comprised of 20 individuals who are leaders from seven University of Maryland Schools and representatives of partner organizations (faith-based organizations, healthcare systems, and research practitioners) with a successful record of collaboration in prior projects who could potentially reach out to their constituent community for members interested in participating in the research planning process. A second group of external advisors includes three PCOR experts and three patients representing health conditions of interest (multiple chronic conditions, diabetes, and impairment). Leadership members are not asked to sign a confidentiality agreement as that is typically unenforceable, nor are they required to demonstrate training in research ethics. Each member is paid equally and expected to attend quarterly meetings and one annual in-person meeting. During these meetings, patients and community partners share insights and perspectives on PCOR, provide updates on the program’s progress, and advise on future plans. A mediation consultant, who provided training for staff and partners, has been retained in the event of partner dispute; however, none has arisen to date. The program activities are developed and coordinated by a dedicated team of experts in training, stakeholder engagement, health disparities, cultural competency, and dissemination and implementation, with support from university-based administrative and project management staff.

Evaluation

PATIENTS is also committed to engaging in evaluation activities to monitor and improve processes and programmatic outcomes, guide strategic planning efforts, and provide evidence to inform development of a sustainability plan. An independent evaluation team conducts these activities through a combination of mixed methods, including a needs assessment survey, annual semi-structured interviews with program leadership members and trainees, and the collection of process data, such as the number and type of grant proposals awarded and the collection of training resources. To produce evidence that resources are perceived as helpful and effective, staff are exploring options for collecting data on utilization and application of training resources. These data are presented to the program leaders to help inform plans for prioritization of program activities and resource allocation. Evaluation data have been used to assess and describe the evolution of PATIENTS; roles played by partners, advisors, investigators, and community members; progress toward meeting annual objectives; and to inform strategic planning. The annual evaluation report is shared with PATIENTS program staff and advisory boards for their feedback. The evaluation team has also developed a logic model, in collaboration with program leadership, to delineate the processes, activities, outputs and expected outcomes of PATIENTS.

PCOR capacity building approach

As part of its mission to improve PCOR, PATIENTS has conducted several activities to improve the capacity of researchers and community members to conduct this area of research. PATIENTS identifies existing training materials and resources and disseminates them across the institution and the community, provides lectures and presentations for faculty and students, mentors researchers, provides training seminars, and conducts partner site visits. These training materials were obtained from a review of resources available from agencies that fund CER/PCOR projects (e.g., AHRQ, PCORI), universities that conduct CER/PCOR projects, and the Patient-Centered Research for Outcomes, Effectiveness, and Measurement (PROEM), a training center of excellence designed to expand and improve training in CER and PCOR methods. The project team shares information about Funding Opportunity Announcements (FOAs) identified by members of the University of Maryland CER/PCOR Work Group, collaborates with community and research partners on proposals and provides guidance on proposal submissions. Providing input during proposal writing is a component of the program’s efforts to build CER/PCOR research capacity at the university and among community partners. PATIENTS offers support on several levels, including facilitating partnerships among researchers and community partners, mentoring junior investigators or those new to CER/PCOR, reviewing preliminary study aims, and providing assistance with navigating the proposal application process. PATIENTS community partners are also involved in the proposal process by reviewing proposals and providing input from a community stakeholder perspective.

Table 1 presents the four sub-projects funded under the infrastructure grant that address the program’s health disparities focus. PATIENTS also supports a pilot studies program for University of Maryland researchers to apply for one-time, non-renewable awards of up to US$5000 per application, intended to support the development of methods for sustainable patient engagement, or for small PCOR projects such as focus groups or interviews that may yield pilot data to guide future research. The merit of the pilot proposals is evaluated by four reviewers: two internal and two external to PATIENTS.

Table 1.

PATIENTS research sub-projects

| Study title/start date/P.I. | Research/community partners | Objectives | Design/aims | Preliminary results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improving heart failure (HF) outcomes (2013) Robin Newhouse, PhD, RN |

• Riverside Health System rural hospitals • Rural nurses and providers • Rural patients |

Build infrastructure to implement evidence-based interventions in health systems (rural hospitals) to improve patient outcomes | 1. Test if an intervention (standardized patient education, post discharge appointment, calling patient to reinforce HF education) improves patient outcomes (lower readmissions, better knowledge and self-care) 2. Identify hospital and provider characteristics associated with better implementation of heart failure patient care processes 3. Determine which healthcare processes and outcomes are most important to heart failure patients |

• 22% of patients readmitted (compared to national rate of 25%) • No relationship between 7 days post discharge self-care subscales and readmission • Improvements in pre- and post-maintenance and management changes in self-care |

| Methods for selecting comparator interventions (2014) Susan dosReis, PhD |

• Maryland Coalition of Families • Alzheimer’s Association of Greater Maryland • Alzheimer’s Association of the National Capital Area |

Develop methods to help surrogates make treatment decisions; investigate methods to match surrogates’ health outcome preferences with the best available evidence-based treatment | 1. To quantify joint process of selecting and prioritizing key attributes of comparator interventions and preferred health outcomes 2. To create a framework to match surrogate preferences for preferred health outcomes with selection of comparator interventions 3. To validate the framework across age, race/ethnicity, and SES that may contribute to potential disparities in patient-centered care |

• Caregivers felt most concepts presented were relevant now or in the past in care management • Most (75%) of the concepts were validated by focus group participants • Priorities for caregivers in care management approaches are presented as two distinct sets: (1) health system decisions and (2) outcomes or goals for care |

| Personalized strategies to activate and empower patients in health and health care (2015) Jie Chen, PhD |

• Montgomery County DHHS Asian American, African-American, and Latino Health Initiatives • Cynthia Chauhan (patient) • Westat |

To provide a comprehensive assessment of effective patient activation and empowerment strategies (PAES) for diverse patient populations | To develop culturally designed personalized PAES that sustain patients’ involvement, develop abilities to manage their health, help patients express treatment concerns and preferences, empower patients to ask questions about treatment options; and build up strategic patient-physician partnership through shared decision-making | • Depressed patients seen in a physician’s office have significantly higher patient activation levels than those with a usual source of care in the ER or hospital outpatient clinics • The primary care setting may be critical to sustain patient-physician relationships that enhances patient engagement in mental health care • People with mental illness and co-occurring physical conditions were significantly less likely to be engaged in health care |

| Patient perspectives on hospital discharge planning and transitions to home (2016) Eberechukwu Onukwugha, PhD |

• Union Regional Medical Center • University of Maryland Medical Center • MedStar Franklin Square Hospital Center |

Examine how to improve hospital discharge planning and transitions to home from the patient perspective | 1. To elicit patients’ and healthcare providers’ perspectives on post-hospital discharge outcomes and components of a patient-centered discharge plan. 2. To elicit patients’ perspectives on the multi-level factors that prevent individuals from managing their own health following hospital discharge 3. To compare findings by setting (urban, suburban, and rural) |

TBD |

Outreach and dissemination activities

Community-based activities include participating in community health and wellness events and identifying members of the community to participate in PATIENTS activities, including discussion of health issues most relevant to West Baltimore and participating in the investigator-initiated research sub-projects funded under the initiative (see Table 1). The program maintains a website, disseminates newsletters and briefs, and has a social media presence (Facebook). These outreach activities will help ensure that research supported by the PATIENTS infrastructure and dissemination of findings will be useful and applicable and thus have a greater likelihood of improving the health of the community.

RESULTS: PROGRAM ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND LESSONS LEARNED

Findings and lessons learned address building community-academic research partnerships, conducting and expanding PCOR, and community and university outreach and dissemination.

Fostering sustainable community-academic partnerships

The governance structure adopted by PATIENTS, coupled with effective engagement and communication strategies, has established a productive, bi-directional exchange regarding program priorities and PCOR training needs among both academic and community stakeholders. Infrastructure-building activities in the first year included a communication plan, a needs assessment of partners and advisors, and launch of the first of four research sub-projects. As of the third year, all but one of the original leadership members remained on the project team; sub-projects and pilot studies have been conducted, and the volume of research proposal productivity continues to increase.

Lesson learned #1: to bridge the expanse from research to dissemination requires relationships built on ongoing engagement and mutual respect

PATIENTS has confirmed that commitment to community engagement is not a “one-off” approach, but instead requires significant and sustained investment of effort and time to keep stakeholders informed and to build a foundation of mutual respect [10, 11] that can facilitate dissemination and implementation. Other inherent challenges in developing a productive PCOR agenda include the need to balance the interests of the community and researchers, building dissemination and implementation strategies into the research design, and addressing ethical concerns such as perceived power differentials and misunderstanding related to the insider/outsider status of research team members [12]. In addition to participatory best practices such as soliciting partner input on decisions and including presentations from advisors and community members on in-person agendas, members of the PATIENTS team hold individual monthly meetings with each partner, and conduct several “reverse” site visits to partner organizations per year, to “meet them where they are,” learn more about their organizational priorities, how PATIENTS can serve their organization, and to disseminate information about PCOR within their settings.

Lesson learned #2: clarification and refinement of program mission and activities matters to stakeholders

Sustaining enthusiasm and support for collaborative programs often requires strategic self-assessment regarding priorities and expectations. Several strategic planning activities, leading to the development of a Program Logic Model (Fig. 1), were conducted in the second year of the program to critically examine progress, generate ideas for the collection of program-related data for evaluation, and to more fully incorporate the inputs and activities of the community. The logic model is a dynamic, graphical depiction of the relationships between the inputs (resources), activities (program actions or events), outputs (what is produced through activities), and how these components are intended or assumed to produce outcomes (changes or benefits that result from the program); unique contextual information and external factors that may influence implementation of program activities are also identified. The PATIENTS logic model delineates program theory components required by the AHRQ grant (governance/administration, training, research capacity, research conduct, and dissemination), as well as the engagement component unique to the PATIENTS design (distinguished in white) to demonstrate the role, activities, and expected outcomes related to CER/PCOR dissemination. The draft Logic Model was further refined with input from two PCOR experts on the external advisory board, and following presentation at the September 2015 in-person project meeting. These activities also culminated in the formulation of PATIENTS mission and vision statements (http://patients.umaryland.edu/about), restructuring of the PATIENTS staffing and resources plan to accommodate the volume of requests for proposal assistance and for community outreach activities, and a new focus on developing a business plan as a part of sustainability.

Conducting and expanding PCOR capacity

Bridging the traditional divide between community and academia to improve PCOR capacity requires identifying common and unique training needs, and implementing strategies to advance the research portfolio, in addition to conducting the research. Addressing the training needs of all stakeholders is an essential component of the strategy to build capacity to conduct quality research and to contribute to advancing the CER/PCOR and health disparities research fields.

Lesson learned #3: determining whether training resources are utilized and effective is challenging

A key element in building an effective learning healthcare community, as expressed in PATIENTS’ mission statement, is to “train patients, stakeholders, and researchers to become co-developers of PCOR.” PATIENTS has made considerable progress in identifying the knowledge and skills gaps of academic researchers and community members, including developing 26 videos between May and September 2016 that were published on the PATIENTS YouTube channel, and cataloging on the PATIENTS website almost 50 training resources (e.g., webinars, case studies, guidelines), with topics ranging from patient/stakeholder engagement and community-based research to guidance on collecting qualitative data and on grant administration. However, this repository of resources is largely passive. Several gaps in the evaluation of the training program remain to be addressed, including assessment of the utilization and value of the resources, particularly for community members. Future evaluation efforts will focus on learning how community members have applied the information, and whether it has contributed to building CER/PCOR capacity.

Lesson learned #4: mentoring is a key component of capacity building

The importance of mentoring has emerged as critical to building a cadre of qualified and successful PCOR investigators. Investigators are provided with assistance in developing proposals, including feedback on research methods, population-specific engagement strategies, the development and conduct of patient advisory committees, and securing appropriate letters of support. Based on the grant writing assistance received from PATIENTS, for example, one community member expects to be able to independently submit a proposal in the future. Mentoring and networking with investigators with experience engaging patients throughout the research process was also recommended by an interviewee, “This would keep the mentor/trainee relationship, and trainees can provide advice for future trainees … I learned on the job, and it was time consuming. It would be nice to pass along this information.” A supportive CER/PCOR Work Group for trainees, students, and junior investigators potentially interested in a PCOR career was another suggestion, as one stakeholder explained, “the CER/PCOR Work Group is intimidating for trainees. A Work Group with just trainees that is more interested in methodology, implementation of projects, career. CER/PCOR [existing] Work Group is more interested in the big picture, conceptual [aspects of research].”

Lesson learned #5: expanding a PCOR research portfolio that fully engages the community is difficult

To date, the program has supported over 40 proposals, most submitted to federal agencies including the Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (close to 60%) and AHRQ (15%), with an approximately 25% success rate. Seven community organizations submitted letters of intent (LOIs) to PCORI’s Pipeline to Proposal Awards initiative, which aims to establish and strengthen PCOR infrastructure for patients, caregivers, and other stakeholders. Of these LOI submissions, three were invited to submit full proposals and one was funded. Despite this early evidence of success, the program plans to continue to engage, mentor, and train non-academic partners with the objective of an increase in community involvement in upcoming proposals. Activities to address this need include targeted mentoring related to the proposal application process and PCOR requirements, and community outreach about PATIENTS, patient-centered research, and health conditions most salient to minority and underserved populations. PATIENTS will continue to encourage academic partners to co-develop proposals with community partners, especially pertaining to health disparities.

Lesson learned #6: conducting PCOR strengthens skills while advancing patient-centered outcomes

The opportunity to conduct small research projects and apply for pilot funds is essential to building the PCOR infrastructure by reinforcing the skills and multidisciplinary partnerships necessary to generate high-quality, translatable findings. Preliminary findings from the four sub-projects (Table 1) help to build evidence regarding interventions to improve rural patients’ hospital heart failure outcomes, methods to assist caregivers in making care management decisions for others, and patient activation and empowerment among subgroups with mental or physical illness; these findings and methodological “lessons learned” are shared with internal and external advisors. Seven University of Maryland researchers have been awarded Pilot Funds; as shown in Table 2, the topics range from medication management, engaging patients with lupus and with mild cognitive impairment in their healthcare, and psychological needs of community adolescents. Pilot funds have been used to support the collection and analysis of data, as well as to compensate participants. As one pilot funds recipient reported during an interview conducted for the evaluation, “Pilot grants are a good resource for trainees interested in PCOR … when trying to recruit patients, researchers need to provide compensation. [It’s a] good use of the Pilot grant.” PATIENTS is monitoring the dissemination activities of sub-projects and pilot studies to ensure they continue to involve community member input and to assess whether they lead to additional funding. Although findings from research funded through the PATIENTS infrastructure have not yet been widely disseminated, the research sub-projects and pilot studies continue to advance the field by providing valuable research experiences for awardees.

Table 2.

PATIENTS Pilot Studies

| Title | Phase | Purpose of funds |

|---|---|---|

| Assessing the psychological needs for well-being in adolescents residing in southwest Baltimore | Data analysis | Transcription, supplies honoraria, meeting space, AV equipment |

| Integrating the voices of individuals with mild cognitive impairment in healthcare decisions | Data collection | Transcription, travel, honoraria, supplies |

| Undergraduate students’ perspectives on how to develop meaningful interventions to curb nonmedical use of prescription stimulants | Data collection | Transcription, supplies, honoria, meeting space, transportation |

| Patient experience, work tasks, and desired outcomes associated with pharmacotherapy self-management in older multimorbid patients | Data collection | Transcription, participant payments, stakeholder compensation |

| Engaging patients with systemic lupus erythematosus to elicit meaningful treatment outcomes | Data collection | Compensation, transportation, printing service |

| Patient, pharmacist, and physician perspectives on atrial fibrillation risk stratification schemes and shared decision-making | Awaiting IRB approval | Compensation, gift cards, travel, software |

| Patient-centered approach to developing a plan to achieve blood pressure control while on medication for hypertension | Awaiting IRB approval | Coordinator, gift cards, interviews, software |

Community and institutional outreach and dissemination and implementation strategies

Improving the rate of culturally appropriate translation of findings that matter to patients and providers requires multi-modal outreach and dissemination approaches and a commitment to identification of factors most likely to contribute to program sustainability.

Lesson learned #7: Engaging senior-level leadership within partner organizations is important for awareness and sustainability

In addition to including representatives from seven university schools on the ISC, PATIENTS staff meet regularly with school deans to personally inform them about the program’s goals and accomplishments, learn more about their priorities, and to make them aware of PCOR training opportunities for students and junior investigators within their departments. This strategy has also been effective at maintaining buy-in of community-level partners. While time-consuming, these efforts to engage senior leadership has been critical to build awareness and regard for the program and to identify important factors related to sustainability. Additionally, although it is important to have a community leader’s support as a portal to a community, the leader often provides the commitment to the partnership, but assigns others to assist with implementation. Thus, it is equally imperative to involve these members from each partner organization.

Lesson learned #8: explaining PCOR, PATIENTS and disseminating relevant health information entails meeting the community “where they are.”

In addition to the reverse site visits to partner organizations, the program employed several communication strategies to reach its outreach objectives, including a program website, and e-mail newsletters and briefs. When communicating findings to the community, partners suggest prioritizing select findings that are most relevant and most likely to impact decision-making. Furthermore, community partners recommend that PATIENTS participate in community outreach activities, which have been valuable for informing community members about PATIENTS, PCOR, and health-related information in ways that are most meaningful and resonant for them. These activities include participating in local community health fairs sponsored by PATIENTS’ faith-based partner and health walks in Druid Hill Park, showing support for these partners, promoting the program within the community and disseminating information to improve health and quality of life. In year 2, PATIENTS staff participated in 95 health fairs, with 385 community members signing up to receive newsletters. To celebrate the program and learn about the work of PATIENTS-affiliated researchers and opportunities to participate, the first annual PATIENTS Day was held on the Baltimore campus in spring 2016. The day-long event included health-oriented vendors from around the city, free health screenings, refreshments, and representatives from local organizations such as the American Cancer Society of MD, the National Kidney Foundation of MD, and the National Diabetes Association of MD, as well as the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and the Black Mental Health Alliance. PATIENTS will continue to evaluate the effectiveness of these strategies as the program matures, particularly to disseminate PCOR research findings supported by the infrastructure and capacity building activities.

The PATIENTS website (http://patients.umaryland.edu/), launched in mid-June 2014 (year 1), includes information about PCOR, PATIENTS governance and partnerships, PATIENTS sub-projects, training materials, resources for pilot funding and CER/PCOR proposals, and findings from relevant, recently published articles. In collaboration with community partners, the PATIENTS leadership identified chronic illnesses about which members of their communities are most concerned, such as cancer, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, and mental health; behavioral health topics such as exercise and nutrition; and information on assistance to help pay for medications. Quarterly newsletters distributed via e-mail and received by almost 300 individuals describe program activities and accomplishments and include an article featuring a PATIENTS member. E-mail briefs present program news and updates to advisors and project members on a monthly basis.

PATIENTS academic and community partners have also disseminated findings in scientific publications and conferences, including comparing traditional and technology-based engagement methods [13], effective use of CBPR principles to engage patients [14], considerations for designing more patient-centered clinical trials [15], implementation of engagement methods throughout the research process [16], and incorporating the views of patients in clinical trials [17], authored by a PATIENTS community partner.

Lesson learned #9: it is never too early to focus on sustainability

At program mid-point, and given early evidence of program success, attention and resources have been applied to identifying and reinforcing factors associated with sustainability of the infrastructure to support CER/PCOR. The logic model framework continues to serve as a guiding framework for data collection and evaluation efforts, essential for demonstrating to sponsors and stakeholders the impact of the program, the link between program activities and outcomes, and the appropriate allocation of resources. Contextual factors, such as institutional support for the program, availability of funds to conduct PCOR, alignment with partners’ priorities, and the development of new partnerships, are also expected to influence the trajectory of the program and the likelihood that current activities can be maintained or scaled up throughout the institution and the community.

CONCLUSIONS

The gap between evidence-based health interventions and actual health care delivery, particularly among communities with persistent disparities in health outcomes, underscores the need to develop and support methods that meaningfully engage and incorporate patients, community, and other stakeholders throughout the research continuum. In this article, we describe a PCOR infrastructure program that is building a skilled PCOR community by providing researchers with methodological expertise through training, mentoring, and the conduct of research projects, and by utilizing culturally appropriate community engagement approaches to build collaborative, reciprocal, respectful partnerships aimed at addressing this gap. These activities also build PCOR capacity, allowing the future development and conduct of projects and activities with diverse funding sources and partners.

Findings suggest that PATIENTS has achieved its foundational aim of fostering sustainable partnerships with diverse patients and healthcare systems. ISC members and external advisors meet with the project team to share insights and perspectives on PCOR and community health concerns, respond to PATIENTS progress and updates, advise on future plans, and participate in evaluation activities to inform the evolution of the program. Program staff have also implemented engagement, outreach, and communication strategies to establish and sustain bi-directional interaction, and to strengthen the underlying institutional infrastructure for PCOR. There is also early evidence that PATIENTS has shown progress toward achieving its second aim (one of AHRQ’s overall goals under this FOA), to provide faculty and staff with methodological expertise in CER/PCOR, and to conduct and expand PCOR by leveraging these partnerships. PATIENTS has been able to increase the capacity to conduct PCOR by providing CER/PCOR-related materials and resources, supporting CER/PCOR proposal submissions, advising on building and maintaining patient advisory boards, and establishing partnerships between academic and community members. Although the majority of submissions to date were led by academic researchers, PATIENTS expects an increase in submissions co-developed by community members. PATIENTS has also been able to build PCOR capacity by funding pilot projects through a competitive review process.

Future efforts will address the program’s third aim to advance dissemination and implementation strategies for PCOR findings, particularly those related to health disparities from studies supported by the PCOR infrastructure. Current engagement strategies, such as the program website, e-mail newsletters and briefs, PATIENTS Day, and community outreach activities, will continue to inform partners and increase awareness of PATIENTS and PCOR within the community. As the program matures, continues to build trust, and balances the priorities of the community and researchers, appropriate dissemination strategies will be developed in conjunction with community members. The mid-point of the program’s funding period also presents a critical time to focus on sustainability beyond the AHRQ funding period. The PATIENTS leadership will consider the evolution of the program, desired outcomes, and the sustainability factors that are necessary to reach these outcomes. These factors will include solidifying existing funding sources and partners, as well as diversifying and securing new funding and partnerships. The roles and responsibilities of the ISC and advisors beyond the program’s funding period will be revisited and reassessed to best support the program. Findings from PATIENTS-supported projects and dissemination strategies will be used to demonstrate the impact of the program and the importance of sustaining PATIENTS beyond the current funding mechanism.

Programs such as PATIENTS have the potential to reinforce the value of bridging the traditional divide between academia and communities to support patient- and community-engaged dissemination and implementation research and foster sustainable PCOR infrastructure. Early evidence demonstrates that investments in community-engaged and PCOR infrastructure should be considered by academic institutions to improve dissemination and implementation of evidence-based advances and practices.

Acknowledgments

Westat serves on the PATIENTS internal steering committee and as the internal evaluators of the program. The authors gratefully acknowledge Liz Jansky for her feedback and Nora Dluzak for manuscript preparation. They would also like to thank the community partners and trainees who participated in the interviews as well as the staff and partners of the PATIENTS program.

Compliance with ethical standards

Reported findings and data

The findings reported have not been previously published and the manuscript is not being simultaneously submitted elsewhere. These data have not been reported elsewhere. Authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review these data if requested.

Funding

This study was funded by AHRQ Grant Number: R24 HS022135.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

IRB

The described study has received IRB approval from University of Maryland, Baltimore and Westat.

Footnotes

Implications

Policy: Investment and support from funders and policymakers can strengthen institutional infrastructure to train and mentor researchers in patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR).

Practice: Healthcare delivery systems are critical partners for dissemination and implementation of findings emerging from research that engages patients and communities.

Research: For research to be useful, trustworthy, and lead to greater dissemination of findings, academic researchers must partner with patients and communities in PCOR.

References

- 1.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Sarena S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119:2633–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartwig K, Calleson D, Williams M. Unit 1: Community-based participatory research: getting grounded. In: The examining community-institutional partnerships for prevention research group. Developing and sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: a skill-building curriculum. www.cbprcurriculum.info. 2006. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 3.Minkler M. Using participatory action research to build health communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115(2–3):191–197. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavernise S. Health problems take root in a west Baltimore neighborhood that is sick of neglect. The New York Times. April 29, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/30/us/health-problems-take-root-in-a-west-baltimore-neighborhood-that-is-sick-of-neglect.html?emc=eta1&_r=1 Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 5.McDaniels, A.K. Collateral damage: advocates aim to save Baltimore children from impact of violence. The Baltimore Sun., 2014. http://www.baltimoresun.com/health/bs-md-health-violence-121114-story.html. Accessed May 31, 2016.

- 6.Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(15):1587–1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed SM, Palermo AG. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380–1387. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter-Edwards L, Cook JL, McDonald MA, Weaver SM, Chukwuka K, Eder MM. Report on CTSA consortium use of the community engagement consulting service. Clinical and Translational Science. 2013;6(1):34–39. doi: 10.1111/cts.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handley M, Pasick R, Potter M, Oliva G, Goldstein E, Nguyen T. Community engaged research: a quick-start guide for researchers. From the Series: UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) resource manuals and guides to community-engaged research, P. Fleisher, ed. Published by Clinical Translational Science Institute Community Engagement Program, University of California San Francisco. https://accelerate.ucsf.edu/files/CE/guide_for_researchers.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2016.

- 10.Kauffman K, dosReis S, Ross M, Barnet B, Onukwugha E, Mullins CD. Engaging hard-to-reach patients in patient-centered outcomes research. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2013;2(3):313–324. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: necessary next steps. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4(3):A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadem P, Minkler M, Perry M, Blum K, Moore I, Rogers J. Ethical challenges in community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 242–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavallee DC, Wicks P, Alfonso CR, Mullins CD. Stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research: high-touch or high-tech? Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2014;14(3):335–344. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.901890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofolahan-Oladeinde Y, Mullins CD, Baquet CR. Using community-based participatory research in patient-centered outcomes research to address health disparities in under-represented communities. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. 2015;4(5):515–523. doi: 10.2217/cer.15.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullins CD, Vandigo J, Zheng Z, Wicks P. Patient-centeredness in the design of clinical trials. Value in Health. 2014;17(4):471–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mullins CD, Chiauzzi E, Frye D, Mack M. Continuous patient engagement: how do we partner with patients throughout the research life cycle? Issues Panel, ISPOR 20thInternational Annual Meeting. Philadelphia. 2015.

- 17.Chauhan, C. (2016). Patients’ views can improve clinical trials for participants. BMJ, 353. [DOI] [PubMed]