Abstract

Evidence-based intervention (EBI) de–adoption and its influence on public health organizations are largely unexplored within public health implementation research. However, a recent shift in support for HIV prevention EBIs by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides an opportunity to explore EBI de–adoption. The current mixed-method study examines EBI de-adoption and the subsequent impact on a community-based organization (CBO) dedicated to HIV prevention. We conducted a case study with a CBO implementing RESPECT, an HIV prevention EBI, over 5 years (2010–2014), but then deadopted the intervention. We collected archival data documenting RESPECT implementation and conducted two semistructured interviews with RESPECT staff (N = 5). Using Fixsen and colleagues’ implementation framework, we developed a narrative of RESPECT implementation, delivery, and deadoption and a thematic analysis to understand additional consequences of RESPECT de-adoption. Discontinuation of RESPECT activities unfolded in a process over time, requiring effort by RESPECT staff. RESPECT deadoption had widereaching influences on individual staff, interactions between the staff and the community, the agency overall, and for implementation of future EBIs. We propose a revision of the implementation framework, incorporating EBI deadoption as a phase of the implementation cycle. Furthermore, EBI deadoption may have important, unintended consequences and can inform future HIV prevention strategies and guide research focusing on EBI de-adoption.

Keywords: De-adoption, De-implementation, HIV prevention, Evidence-based intervention, Dissemination and implementation, Complex adaptive system

Evidence-based interventions (EBIs), which demonstrate efficacy under research conditions, help to ensure that communities receive quality services. Considerable dissemination and implementation (D&I) research in public health has been dedicated to examining implementation of EBIs in practice settings [1]. EBIs are typically implemented in a series of stages, but there is a paucity of research on the end of the EBI life cycle—de-adoption of interventions [1, 2]. Also, sometimes described as de-implementation, misimplementation, exnovation, or disinvestment [3], de-adoption occurs when activities associated with an EBI conclude or are abandoned. Early evidence suggests interventions are frequently de-adopted [4], but it is unclear how EBIs are de-adopted within organizations or what the impact of de-adoption is on the public health system. We explore intervention de-adoption in the context of a recent policy shift by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), designed to promote uptake of a collection of HIV prevention EBIs. This policy shift provides the opportunity to understand how EBIs are de-adopted and the potential consequence of de-adoption for staff, agencies, and communities.

IMPLEMENTATIONOF EBIs

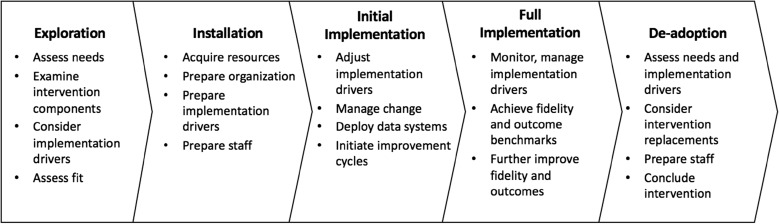

The implementation framework proposed by Fixsen and colleagues [2] describes EBI implementation as a process within organizations, which is influenced by implementation drivers, such as socioeconomic conditions, funding changes, or leadership. In the most recent iteration of the implementation framework, the implementation process is described as unfolding over time in a series of stages: exploration, installation, initial implementation, and full implementation [5]. Briefly, the exploration stage is characterized by an organization selecting and adopting an EBI. During the installation stage, organizations actively prepare and build the necessary infrastructure to implement an EBI, such as training needed staff and securing funding streams to support the EBI. In initial implementation, the organization makes any necessary adaptations to the EBI that might improve the fit between the EBI, existing organizational structure, and community needs. During the full implementation stage, the organization implements all aspects of the EBI. The organization delivers the prescribed activities of the EBI, and activities remain relatively stable. The full implementation stage may conclude if EBIs are de-adopted or abandoned, and activities associated with the EBI end because program services are inefficient, poorly executed, or ineffective. Throughout each stage, intervention sustainability is a necessary focus of implementation activities and is an indication of successful implementation. Although presented in a linear fashion, significant changes in implementation drivers may lead an organization to revisit earlier stages of the implementation process.

EBI de-adoption

Existing reviews of intervention de-adoption suggest interventions are frequently de-adopted for many reasons [3, 4]. An intervention may be de-adopted because the health issue of concern has dissipated and services are no longer needed to address this issue, a more efficient or effective approach replaces existing services, and/or policy supporting an intervention wanes. In cases where a health issue dissipates or a more effective approach becomes available, EBI de-adoption and redirection of efforts may be beneficial. However, in their seminal work on sustainability of interventions, Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone [6] outline three primary reasons why de-adopting EBIs (i.e., intervention discontinuation) can also be problematic. First, ongoing intervention may be especially valuable for chronic public health issues, like HIV, that require continued intervention and control over an extended period. Second, initial investments that help build needed capacity to implement interventions are lost (e.g., time, staff, collaborative relationships, physical infrastructure), leading to inefficient use of resources. Third, inconsistent policy and funding priorities can lead to reductions in support for EBIs, creating mistrust and frustration among local organizations and communities. These arguments suggest that EBI de-adoption may have substantial effects not only for the intended individuals of the intervention but also for the public health system in which interventions are de-adopted (e.g., staff, agencies, and communities).

Although the influence of de-adoption on the public health system has not been well documented, studies focusing on the influence of earlier EBI implementation stages demonstrate widespread influences across the public health systems in which EBIs are embedded. The various systems include aspects of the larger sociopolitical context, the local community, and the implementing organization. Variables characterizing these systems interact with each other, across systems, and with the innovation (i.e., the EBI) in complicated ways over time [1]. To better describe the nature of these complicated interactions, the public health system is increasingly conceptualized as a complex adaptive system (CAS) [7–9]. CAS are systems made up of many individual, often heterogeneous, components. Over time, the system changes per interactions of the individuals within the system, and the interaction of the system with the surrounding environment. For example, CAS principles suggest that EBI de-adoption may substantially influence individuals who deliver these EBIs directly to clients, agencies that provide these interventions, and communities that receive them. CAS principles also suggest EBI de-adoption may influence the nature of the relationships among these individuals and groups. Consideration of CAS in conjunction with existing EBI implementation frameworks may offer fresh insight into the relationship between the public health system and the EBIs.

De-adoption in public health settings

Despite the potential importance of de-adoption and its likely impact on the public health system, very little research has focused on this topic. One notable exception in public health is a study conducted by Freedman et al. [10] that examined shifting support for obesity prevention initiatives and the consequences of EBI de-adoption on agencies and staff. In their study, changes in policy led many state public health agencies to de-adopt interventions and reduce staffing. Remaining staff often expressed frustration and decreased morale. In alignment with the argument present by Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone [6] and CAS principles, results from this study suggested that EBI de-adoption had multiple consequences among agencies and staff.

Most existing research has been conducted in healthcare settings indicating that many interventions in medical care should be de-implemented [3]. A valuable product of this work has been the development of several frameworks for stakeholders within healthcare systems [3, 11]. These frameworks help identify and encourage de-adoption of practices that demonstrate either inert or harmful effects or de-adoption when there are more cost-effective interventions available. Efforts are currently underway to examine the impact of these frameworks [12]. However, differences between the health care and the public health systems make it difficult to generalize findings from health care to public health.

EBIs for HIV prevention

In the present study, we explore EBI de-adoption in the context of a recent policy shift by the CDC. In the early 2000s, the CDC developed the Diffusion of Evidence-Based Intervention (DEBI) project to disseminate a collection of HIV prevention EBIs nationally. These EBIs focused largely on behavior modification to reduce the risk of HIV infection. The CDC recommended a host of EBIs to departments of public health (DPH) and community-based organizations (CBOs) for delivery at the local level and facilitated dissemination through funding and training. Uptake of DEBI interventions was substantial. DEBIs have been disseminated to approximately 11,300 organizations including public health departments, community-based organizations, drug treatment facilities, and medical clinics in the last 15 years [13].

In 2012, the CDC formed the High-Impact Prevention Strategy (HIP) to align with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy [14] and incorporate innovative HIV prevention approaches developed since the initial formation of DEBI (e.g., pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP) [9]. Under HIP, support shifted toward more cost-effective strategies, including the expansion of HIV testing and the promotion of interventions to help HIV-positive individuals minimize the risk of transmitting HIV to uninfected partners. There was increased emphasis on interventions that help newly diagnosed individuals engage in care, prevent individuals from falling out of care, and encourage adherence to medications that decrease viral load. Some DEBI interventions were subsumed under HIP, but the CDC no longer financially supported many of these interventions, making de-adoption of DEBI interventions likely. The changes in CDC policy regarding HIV prevention provided a unique opportunity to study de-adoption in public health as it was occurring and to examine the broad reaching impact of these changes.

Research aims

Using frameworks of EBI implementation and principles of CAS, we examined EBI de-adoption to understand the potential consequences of these events for the HIV prevention system and communities at risk for HIV. To achieve this overarching goal, we conducted a case study with an agency that de-adopted RESPECT, an EBI widely implemented under the DEBI project. Specifically, we first examined the extent to which resources and capacity built over the course of RESPECT implementation may have been lost once RESPECT was de-adopted. Second, we explored how de-adopting RESPECT may have influenced the individual staff and clients, the agency, the community, and the relationships among these various entities.

METHODS

We conducted a mixed-method case study with an agency that implemented RESPECT as part of a continuum of services. Case studies offer the benefit of providing the rich contextual data needed to adequately examine whole systems, individuals within systems, and events over time that are difficult to achieve using other research designs [8, 15]. In addition, case studies are useful to inform existing theoretical frameworks by providing counter factual examples. With these benefits in mind, we collected qualitative and quantitative data from multiple sources at the agency to achieve the study aims. The Institutional Review Board at the lead author’s home institution at the time data were collected approved all research protocols.

The CBO

The case study agency was a well-established, non-profit CBO dedicated entirely to HIV prevention. The agency primarily targeted at-risk men who have sex with men and HIV-positive individuals, but offered services to all members of the community with sexual health concerns. The agency was structured into two divisions: one focusing on prevention and other services for individuals who are HIV negative (which we refer to as the Prevention Division), and another primarily serving and providing support for individuals who are HIV positive (which we refer to as the Support Division). We will describe the Prevention Division below in more detail. Briefly, the Support Division provided a variety of services including referral to health care, housing, and family and employment support for HIV-positive individuals and their families. The agency received financial support from a variety of sources including federal, state, and local government; donations from the public; and other non-profit organizations. The agency had an annual operating budget of approximately six million dollars at the time data were collected.

The Prevention Division and EBIs

The Prevention Division provided several evidence-based prevention services and interventions, including testing and counseling for HIV, referral services for STI testing, and behavioral risk-reduction interventions. We focused on RESPECT, a DEBI intervention that was implemented for 4 years, beginning in 2010, through the division. Over the 4 years that RESPECT was implemented, there was a general expansion of services across the agency. Testing numbers increased from approximately 2000 to 4000 with an annual seropositivity rate ranging from 1 to 1.4%. The division also experienced an increasing operating budget from approximately 1.4 million per year to approximately 1.8 million per year.

RESPECT is a brief counseling intervention primarily conducted in conjunction with HIV testing [16]. RESPECT is designed to target at-risk individuals for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Using theory-based counseling techniques, providers actively engage clients in identifying risk behaviors and developing a plan for risk reduction during either one or two counseling sessions. The CDC developed intervention protocols for RESPECT by outlining specific core components of the intervention, and making them available to agencies to help implement the intervention and maintain fidelity to the intervention’s protocols [14]. Training and certification in RESPECT were available through the CDC Prevention Training Centers. The initial randomized control trial demonstrated efficacy of a two-session version of RESPECT in reducing both risk behaviors and infection incidence rates [16]. However, a subsequent trial focused on the single-session version of RESPECT, which had been widely adopted by agencies after the development of the rapid HIV test, failed to reproduce these results [17].

Shortly thereafter, the CDC opted to redirect supporting funds for RESPECT toward other, more effective interventions as a cost saving measure.

The CBO eventually replaced RESPECT with the HIP intervention Antiretroviral Treatment and Access to Services, or ARTAS. ARTAS is an individual-level intervention designed to link recently diagnosed HIV-positive persons to medical care [18]. Also using theory-based techniques, providers encourage recently diagnosed individuals over multiple sessions to identify and use personal strengths to achieve goals and navigate the medical system to engage in routine care. Ideally, providers have experience as case managers, social workers, and/or HIV test counselors. Similar to RESPECT, the CDC developed and provided intervention protocols to agencies to help implement the intervention, and the CDC provided training for the intervention at Prevention Training Centers [14].

Recruitment and participation

We collaborated closely with the case study agency and staff for data collection and recruitment. The agency director released any restricted internal records and provided contact information for staff members involved with either supervising or delivering RESPECT for recruitment. All staff members involved with RESPECT were invited to participate (N = 7), including current and former employees. One individual declined to participate, and one individual was unavailable for interview. Five staff members, in both delivery and supervisory positions, participated in the study. Participants were provided a US$10 gift card for participation.

Data collection

We collected three primary sources of data: (1) existing archival reports of agency functioning and RESPECT delivery, (2) individual client records of RESPECT participation, and (3) interviews with RESPECT staff.

Existing archival records

We collected public and internal archival records from the agency. These documents span the time when RESPECT was first implemented, beginning in 2010, to its de-adoption at the end of 2014. Publicly available reports were collected via the agency website including annual fiscal and overall reports.

The agency also provided RESPECT reports generated for internal use and reporting to funding agencies. These reports provided detailed information about how the agency implemented RESPECT (e.g., how clients were referred, number of clients provided RESPECT). They also stated RESPECT outcome objectives (e.g., goals for how many individuals would be successfully enrolled in the intervention), any challenges meeting the stated objectives, systematic changes made to the intervention over time, and budget allocation.

The agency provided employee information for all staff members who were involved in the delivery of RESPECT in an aggregate, de-identified format. The information included job roles and descriptions, number of staff, educational level, training dates, and salary.

RESPECT client records

The agency provided individual records of all clients who received RESPECT in a de-identified format. Information collected on clients included basic demographic information, an assessment of HIV risk, HIV status and enrollment in care, and aspects of RESPECT delivery. Demographic characteristics, HIV status, and selected risk characteristics are provided in Table 1. Most participants were HIV negative, between the ages of 18 and 45, identified as white and male, and resided in the immediate county where the agency was located. The most commonly reported risk behavior among participants was engaging in unprotected sex within the last 12 months. In addition, many participants reported engaging in other high-risk behaviors including sexual behavior with someone of HIV-positive or unknown status, and/or injecting drugs intravenously.

Table 1.

RESPECT client characteristics (N = 396)

| Characteristic | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Residence | |

| Immediate county | 82 (325) |

| Adjacent county | 16 (63) |

| Another area | 2 (8) |

| Age (by category) | |

| 18–25 | 21 (83) |

| 26–35 | 28 (111) |

| 36–45 | 25 (99) |

| 46–55 | 20 (80) |

| 56+ | 5 (20) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 94 (373) |

| Female | 1 (4) |

| Transgender | 1 (4) |

| Other/declined | 3 (10) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 65 (257) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13 (51) |

| Black/African American | 7 (29) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 4 (17) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (17) |

| Other/declined | 4 (19) |

| HIV risk behaviors | |

| Unprotected sex | 78 (309) |

| Sex with person of HIV+ or unknown status | 68 (271) |

| Intravenous drug use | 13 (50) |

| HIV status | |

| HIV − | 64 (255) |

| HIV + | 30 (120) |

| Unaware of status | 4 (14) |

Participant interviews

We conducted two interviews with each participant (for a total of ten interviews). The first interview lasted approximately 90 min, and the second interview lasted approximately 30 min. Interviews were conducted either in person or through video conferencing using a semi-structured interview guide. The interview guide for the first interview was designed to elicit information about the participant’s experiences and opinions about implementing and delivering RESPECT; reasons why RESPECT may have been discontinued; and decision-making processes that informed RESPECT delivery, de-adoption, and replacement with ARTAS. The interview guide for the second interview was tailored to individual participants, and questions were designed to provide more detail about specific topics (e.g., what individuals did after RESPECT was de-adopted), and to collect additional information that emerged during initial interviews (e.g., follow up with one participant about an event discussed by another participant). Interviews were audio recorded, and consent was provided verbally at the time of the interview.

Data management and analysis

Interview audio was transcribed using a transcription service. All transcriptions were reviewed for accuracy. Qualitative data were analyzed using MAXQDA 11. Quantitative data were analyzed using Stata 14. All codes and code definitions were kept in a codebook.

First, we developed a case study analysis of initial RESPECT implementation and subsequent de-adoption using all available data (i.e., archival records, the clients’ records, and staff interviews). For the case study analysis, we used the propositional approach based on existing theory as described by Yin [15] and framed the narrative chronologically to align with the implementation framework (see Introduction) [5]. Archival data were synthesized to provide a chronology of RESPECT implementation from initial adoption, implementation, de-adoption, and replacement of RESPECT with ARTAS. Participant interviews were used to provide additional detail when reports were unclear, particularly in the early implementation and de-adoption stages.

Second, we thematically analyzed interviews with RESPECT staff to understand the impact of RESPECT de-adoption. Initially, we conducted a directed content analysis to identify discussions of RESPECT de-adoption and the impact of these events. Data were then thematically coded to identify influences of de-adoption on the staff, the agency, and the community at large. We conducted inter-coder reliability checks with a second coder to help ensure clear thematic code definitions and consistent application of thematic code. In cases of disagreement, coders held discussion until reaching consensus. Given the small number of participants in our study, all quotes are anonymous to protect the participants’ identities.

RESULTS

The life cycle of RESPECT

Initial selection/pre-implementation

Beginning in mid-2010, the agency was awarded a 5-year grant to implement a DEBI intervention. Among the options, RESPECT was specifically selected by the agency because it was an individual-level counseling intervention that could be delivered to both HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals. The agency had already implemented several DEBI interventions targeting couples and the community at large and had well-established existing services to help link HIV-positive individuals into care. The agency also had HIV testing routinely available with brief counseling. The director felt that RESPECT would help meet the demand for more intensive counseling and was considered a good fit with existing services.

The agency was allowed a 6-month period at the beginning of the grant to plan RESPECT implementation and develop the needed infrastructure for implementation. The agency created three new positions: two counselor positions and one evaluation position to implement, deliver, and evaluate RESPECT. Each of the RESPECT staff and the director traveled to a Prevention Training Center to receive training in RESPECT. The staff had to develop physical infrastructure and materials for the intervention, particularly a charting system for tracking clients, recruitment materials for the intervention, and quality assurance protocols. Including employee salary and benefits for the first 6 months, training expenses, equipment costs, and indirect costs (e.g., office space rental), the agency spent approximately US$60,000 in the first 6 months to get RESPECT up and running.

Initial implementation/full implementation

The agency targeted men who have sex with men, both HIV negative and positive, and began enrolling participants in the beginning of 2011. With permission from the CDC, and in line with publicly available guidance through the CDC Effective Interventions website [19], the agency opted to de-couple RESPECT from HIV testing and to provide the intervention to HIV-positive individuals and people unaware of their status who were interested in counseling but did not want to take an HIV test in addition to the standard target population. The agency also opted to lengthen counseling sessions to provide more intense counseling because the staff felt that their clients experienced challenging circumstances that made behavior change more difficult. The intervention was well received among staff working in both the Prevention and the Support Divisions. In these initial months, the agency experienced relatively few difficulties with implementing the intervention. However, one challenge the agency experienced was successfully enrolling the target number of clients into the intervention. The staff developed multiple strategies for improving enrollment and fit with existing services and clientele needs. For example, one key strategy was to strengthen collaboration with the Support Division of the agency. Staff within this division referred HIV-positive clients who would potentially benefit from risk-reduction counseling because the client exhibited risk behaviors for exposing his (or her) partners to HIV.

Once established, the agency and staff provided consistent services over the next 3 years. Three new counselors were hired and trained at different points because of staff turnover. On average, the agency reported spending US$106,500 per year on intervention expenses.

Enrollment and participation for RESPECT steadily increased. Table 2 provides details regarding RESPECT delivery with all clients who participated in the intervention. Many clients were referred from other services or interventions within the agency (e.g., from support services or from basic testing). The evaluator provided supervision and routine monitoring to ensure fidelity to the RESPECT protocols. Staff reported helping clients identify a risk behavior and develop a risk reduction step, which varied from small behavioral changes (e.g., carrying condoms or deleting a dating site account) to substantial behavioral changes (disclosing positive status with a partner or getting an HIV test). A large portion of clients reported accomplishing their risk reduction step. Approximately one third of clients who participated in RESPECT were referred to another service, primarily testing for HIV or another sexually transmitted infection. In short, RESPECT was an overall success within the agency and community.

Table 2.

RESPECT delivery to clients

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Referral into RESPECT | |

| Agency staff | 66 (263) |

| Friend/family member | 16 (63) |

| Public advertising | 14 (54) |

| Other | 4 (12) |

| Completed RESPECT sessions | 88 (348) |

| Risk reduction step | |

| Developed | 98 (391) |

| Achieved | 72 (286) |

| Referral to testing services | |

| HIV test | 20 (80) |

| STI test | 33 (130) |

De-adoption

In the spring of 2014, the agency was notified by the CDC that RESPECT was not going to be supported in the future, due to a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of a single-session RESPECT. The agency was allowed the option to either continue RESPECT or switch to another intervention for the final 9 months of the grant. Collectively, RESPECT staff decided to transition to ARTAS. The agency was allowed 3 months to plan and train for ARTAS and discontinue RESPECT. The counselors immediately began to communicate with collaborators, in and outside of the agency, that they were no longer offering RESPECT. Clients who had already completed the first RESPECT session could complete the intervention, but the agency stopped enrolling new participants. Clients seeking counseling were referred to brief counseling offered as part of testing if HIV negative (such as counseling, testing, and referral) or to group interventions if HIV positive. In addition, the agency and staff stopped many of the routine activities that were a part of RESPECT delivery (e.g., keeping client records or conducting monitoring and evaluation).

While staff engaged in activities to conclude RESPECT, the agency and staff prepared for ARTAS implementation. RESPECT counselors received training in ARTAS. Counselors reported having to work closely with the Support Division of the agency, which already provided an extensive and robust variety of services for HIV-positive individuals. Regardless of the effort invested in ARTAS, two of the three staff members involved most directly with providing RESPECT left the agency at the conclusion of the grant support. The agency simultaneously submitted a proposal to renew support through the same funder, but it did not opt to include ARTAS as part of its proposal. Instead, the agency opted to use funds to support its well-established and more comprehensive support services available for HIV-positive individuals through the Support Division.

Additional consequences of RESPECT de-adoption

Although the case study provides a general view of the RESPECT life cycle from adoption to abandonment, participant interviews provided more detail about RESPECT de-adoption. Four primary themes emerged: (1) strategic agency realignment with national policy, (2) disconnect among agency services, (3) feelings of frustration and concern among staff, and (4) community and client influences. These themes are organized loosely according to influences on the agency, individual staff, and clients and communities. We provide supporting quotes for each theme in Table 3.

Table 3.

De-adoption themes and supporting quotes

| Theme | Number | Supporting quote |

|---|---|---|

| Agency realignment | 3.1 | I knew that in order to be the most competitive for another five years that we should move in that direction. Once again, so we were the most competitive, but also so that we’re gonna be successful if awarded, right? Because we want to show we have quality programming. |

| 3.2 | It seemed like funding, the landscape, was absolutely shifting, and it seemed like our director’s proposal was a way to put us in a position so that we could receive funding in the future. | |

| Disconnect among services | 3.3 | We got a lot of referrals from case managers who knew that their clients needed to have those conversations ….We have definitely had case managers still coming to us, asking, like “Okay, well what do I do with this person now?” |

| 3.4 | Because our case managers are working to make sure that their housing’s table and they’re making their appointments…that they don’t really get that training on how to have these frank conversations. And some of them aren’t comfortable having those conversations. | |

| Frustration and concern | 3.5 | It’s just a frustrating place to be. Because does it work for every single person? No….But on a personal lower-level when you’re working with individuals who tell you how much the intervention has meant to them and how it’s made them think different [or], how it’s just been nice to have somebody who cares and listens to them without judging them….It’s not necessarily a measurable impact. |

| 3.6 | It doesn’t feel like it’s even a place that I belong anymore. And a lot of that was just a cultural shift. It’s disappointing. I think that I can do this work, and I continue to do work with people in helping them find resources and being a true navigator, but I don’t want to do it in that setting. | |

| Client/community | 3.7 | We’ve had a lot of people continue to ask for RESPECT… So that sucks to tell people whether its clients or staff that like, “Sorry, we can’t help you. We don’t have money to do that anymore.” |

| 3.8 | I think there’s always the consequence of damaging relationships of like offering some services [like RESPECT] and then pulling them out, and promoting X. | |

| 3.9 | For negative people they can still have those conversations as part of the HIV testing situation. But positive folks don’t have that. And so, if they’re not having those conversations with their doctor or their case manager, then they really [aren’t having the conversation]—it was a loss of that space. | |

| 3.10 | It removed completely those resources for folks who were in places where they were ready to have conversations about their risk to help reduce it. Now we’re just medicalizing, and I’m telling people to go onto [pre-exposure prophylaxis], and I don’t know that’s enough for folks. |

Strategic agency realignment with national policy

The agency had the option to continue RESPECT, but staff members reported choosing to de-adopt the intervention, and implement ARTAS, because of the larger shifts in CDC policy. Staff members were strategic about this decision even though ARTAS overlapped heavily with the Support Division services, suggesting that it was important for the agency to demonstrate competency at providing these kinds of services to secure continued funding in the future (Table 3, 3.1). Counselors also recognized the changing orientation that was ultimately going to influence financial support for the agency, services that the agency would be providing, and job roles for staff who would continue working for the agency (Table 3, 3.2). Although RESPECT was a better fit for the agency and the community, adopting ARTAS helped to ensure financial support for the agency in the future.

Disconnect among agency services

The agency also experienced disconnect, confusion, and lack of coordination among services while transitioning from RESPECT to ARTAS. Staff working with HIV-positive individuals in the Support Division continued to refer clients for RESPECT (Table 3, 3.3) despite repeated efforts to communicate within the agency that RESPECT was no longer being offered. The disconnect among services created a challenge for case managers who recognized the need for counseling, but were not able to refer their clients to counseling (Table 3, 3.4). The particular counselor in this example suggested that, in addition to not being comfortable having conversations with clients about risk, staff also may not have adequate training or time to appropriately converse with clients about risk reduction. In this way, discontinuation of RESPECT created a gap in services that was not mitigated by implementation of ARTAS.

Feelings of frustration and concern among staff

In addition to shifting roles for RESPECT staff, many expressed frustration with the changes in national policy, agency reorientation, and de-adoption of RESPECT. One explanation for this frustration was that staff developed relationships with clients and felt concern for the consequences of these changes on clients in the future, especially for clients interested in behavior change (Table 3, 3.5). As such, it was frustrating as a staff member to recognize a need among the client community, but lack the job flexibility to meet this need. Additionally, staff members expressed concern about whether they were valued or whether their skills were needed moving forward as the agency prepared for a larger change in national policy. As one counselor who ultimately left the agency suggested, these policies were going to shift how services were delivered on the ground, and felt that this would also change how certain skills among employees were valued (Table 3, 3.6).

Client and community influences

Lastly, staff frequently discussed how the de-adoption of RESPECT and implementation of ARTAS impacted relationships with clients and the community. Because the counselors spent a significant amount of time in the community recruiting participants for RESPECT, it had become common for many potential clients to be referred to the intervention by word of mouth. As a result, many members of the community and clients already receiving services from the agency, continued to request RESPECT, creating a disconnect between RESPECT staff and clients (Table 3, 3.7). Many staff members suggested that de-adoption of RESPECT had potentially strained relationships with the community because the community had come to rely on the service and explaining that the change in services were due to lack of evidence undermined the reputation of the agency (Table 3, 3.8).

Counselors described multiple consequences of RESPECT de-adoption on clients depending on their HIV status. As mentioned earlier, counselors felt that the lack of counseling opportunities for HIV-positive individuals was unfortunate because case managers recognized the benefit of risk reduction counseling for their clients, but did not feel comfortable or skilled at having the conversations themselves (Table 3, 3.9). However, some counselors suggested that RESPECT de-adoption and the general policy shift toward providing more services for HIV-positive individuals, would have slightly different, if not greater, consequences for HIV-negative clients (Table 3, 3.10). The concern among staff was that the focus on clinical services and medication, as a preventive measure in lieu of behavior modification, would not be adequate for many of their HIV-negative clients.

DISCUSSION

There are times when it may be appropriate and desirable to change public health policy to promote more effective or efficient interventions, leading to de-adoption of existing evidence-based practices. However, de-adoption of existing EBIs is a rarely examined component of the implementation process [4]. We address a critical gap in public health D&I research by describing activities that take place when an intervention is de-adopted and the outcomes of de-adoption for staff, agency, and community. Our findings have implications for D&I frameworks and policy efforts designed to encourage abandonment of low-value interventions and encourage uptake of more effective EBIs.

De-adoption in an HIV prevention setting

Much of the existing literature focuses on frameworks to identify interventions for de-adoption and encourage their abandonment [3, 11]. In contrast, the present study addressed an intervention already identified as low-value in light of more cost-effective EBIs and examined how de-adoption unfolded over a period of several months in an HIV prevention organization.

Our results describe how staff collectively decided to de-adopt RESPECT after being notified that the intervention was no longer going to be financially supported by the CDC. Once the staff agreed to de-adopt RESPECT, RESPECT staff gradually concluded activities associated with the intervention and communicated to other staff and clients that the intervention would be ending. Simultaneously, RESPECT staff prepared for implementation of a new intervention focused on linkage to care, ARTAS.

In line with prior work by Shediak-Rizkallah and Bone [6] and existing evidence [10], our findings support the general premise that de-adoption of an EBI may have consequences for organizations and staff. We captured several potential consequences of de-adoption for the case study organization and staff as well as the clientele and community. By incorporating CAS principles, which encourage consideration of the dynamic interaction between the interventions and the systems in which they are implemented over time [7], the results presented here also yield insights that may not be evident using EBI-focused implementation frameworks alone. For example, this work highlights how adaptation activities, often helpful in the early implementation stages to enhance fit and sustainability over time [2, 5], may make de-adoption more difficult. In the initial implementation of RESPECT, client recruitment was challenging for staff. To resolve this issue, staff opted to de-couple RESPECT from testing, offer the intervention to HIV-positive individuals, and leverage relationships with other staff to increase referral of HIV-positive individuals who would potentially benefit from intervention. Although it is likely that many agencies implementing RESPECT did not adapt the program in this way, a national-level study shows that other agencies delivered RESPECT to HIV-positive clients [20], and RESPECT was approved to be delivered without testing [19]. After RESPECT was de-adopted, however, staff from other programs at the agency continued to refer clients to RESPECT, leading to frequent negative interactions with misinformed clients and confused staff. In other words, the activities that were valuable for initial implementation of the EBI became problematic once the EBI was de-adopted.

Implications for D&I frameworks

We used Fixsen and colleagues’ implementation framework to guide our analyses. This framework implies that de-adoption may occur if implementation drivers are not favorable (e.g., inadequate funding) to sustain the intervention [5]. However, there is very little description in this framework overtly describing de-adoption, how de-adoption may take place, or potential outcomes of intervention de-adoption. We propose a revision to the implementation framework that posits EBI de-adoption as a distinct stage, separate from full implementation, occurring when agencies no longer offer an intervention (see Fig. 1). Our description of RESPECT de-adoption in the case study organization suggests that de-adoption is a process wherein administrators and staff actively engage in activities to conclude the intervention. During this stage, administrators and/or staff must make decisions about whether to maintain aspects of the intervention, replace the intervention, or completely redirect staff efforts toward another area of service delivery. Ideally, staff work to help smoothly conclude activities, for example, communicating to other staff and clients that the intervention is no longer available and why. If a new intervention has been selected for implementation, staff may simultaneously work to install the new intervention. In other words, agencies may be simultaneously engaging in the de-adoption stage for one intervention and in the exploration and installation stage for a replacement intervention. We place the de-adoption stage after the full implementation stage, but recognize that de-adoption may occur at any point within the implementation process. Implementation drivers like adequate funding, for example, may lead an organization to de-adopt an EBI before the intervention has reached the full implementation stage.

Fig 1.

The implementation framework with EBI de-adoption as a distinct stage

Furthermore, our findings suggest that de-adoption is not simply the converse of intervention sustainability, which should be considered throughout implementation [2]. Organizational consideration of intervention de-adoption may occur in several ways. For example, organizations may proactively choose to de-adopt EBIs for a variety of reasons (e.g., the intervention is inefficient, insufficient client demand, or the availability of more effective interventions). Alternatively, as was the circumstance for our case study, organizations may reactively de-adopt an intervention when it becomes clear that implementation drivers outside of the organization’s control will not support the intervention (e.g., policy changes). The decision to de-adopt a program is the first step in a process that was described in our case study. The process may unfold differently for agencies who proactively choose to de-adopt and those who feel compelled to end programs.

To our knowledge, very few implementation frameworks consider de-adoption in the context of the full life cycle of EBI implementation. We suggest that a focus on de-adoption will yield a more complete conceptualization of the EBI implementation process and outcomes. Furthermore, D&I frameworks will benefit by framing the impact that de-adoption has on organizations, staff, and communities by providing guidance on how to appropriately conclude interventions when there is a lack of evidence to support the intervention, or more effective or efficient EBIs are available.

Implications for de-adoption in HIV prevention and public health

There is limited evidence that directly addresses the effects of policy change and EBI de-adoption; yet, this is a key issue in public health practice. Assuming new interventions for HIV prevention will continue to be developed, and existing interventions might be discontinued, we discuss several practical implications of EBI de-adoption for HIV prevention. The movement toward HIP interventions represents continued prevention for the HIV epidemic in the USA (the first reason to sustain interventions) and an effort to incorporate advancements in HIV prevention [9], but the rapid shift away from previously supported DEBI interventions may have several unintended and concerning consequences. The case study organization lost many investments made in the early implementation of RESPECT, especially in terms of staff hiring and training and positive collaboration between divisions of the agency. It is unclear the extent to which other organizations have de-adopted DEBI interventions, either in favor of HIP interventions or for other reasons, but even if a few organizations de-adopted DEBI interventions, the lost investments represent a substantial inefficiency both in terms of resources (e.g., money invested in training, staff) and in time spent.

The case study also demonstrated the risk of damaging relationships with the community by withdrawing resources and services that the community has come to value. This is especially concerning given that many DEBI interventions were available to HIV-positive individuals, a primary target population of HIP policy and programs. It is important to pay close attention to how policies may directly or indirectly influence relationships with these communities, especially HIV-positive clients.

The points outlined previously suggest several ways that the HIP strategy or other policies designed to encourage intervention de-adoption might be improved [3, 11]. Our study highlights the potential value of targeted efforts to encourage and support successful de-adoption as others have done in healthcare settings [3, 11]. For example, providing support to organizations to help communicate with clients and the community as to why interventions are no longer available may help decrease the confusion and help protect relationships between organizations and local communities. Our study also highlights alternative points of intervention for improving the quality with which prevention services are delivered. CAS principles encourage consideration of how EBIs influence the overall quality of the public health system, the local agencies that provide the EBIs, and the experienced staff working in this field, not simply the intended effects of an intervention for a target population. Furthermore, the successful implementation and eventual de-adoption of EBIs likely influences the implementation and success of future EBIs [7–9]. Again, focusing on community relationships, the de-adoption and replacement process would be more smooth if thoughtful approaches, such as allowing adequate time to conclude intervention activities, were in place. To preserve valuable community relationships, agencies may need additional time to reorient and leverage these connections to enhance the success of new services supported by new policies.

Future directions for research on de-adoption

Replication and extension of our findings are essential given that the present study is largely exploratory and descriptive. The factors that precipitate de-adoption within an organization, the extent to which key stakeholders in organizations support EBI de-adoption, the similarity between de-adopted and replacement interventions, as well as other complexities of the implementation context likely influence both the de-adoption processes and the consequences. For example, it is likely that many interventions end abruptly with very little, if any effort, on the part of the organizations and staff. It is possible that abrupt abandonment of interventions may have a different set of consequences than instances in which staff work to smoothly conclude intervention activities. Moreover, initial negative consequences identified in this study may wane over time as staff and the community adjust to changes and find new ways to collaborate. Lastly, studies that examine the residual value of having implemented interventions (e.g., using skills learned from previous interventions while implementing new interventions) or the persistence of intervention components may have valuable implications for informing how the beneficial aspects of interventions might be maintained and the non-beneficial aspects of interventions might be successfully abandoned.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Participants may be subject to various types of reporting bias (e.g., desirability bias). The authors took steps to encourage truthful responses, and many participants offered both positive and negative opinions during interviews. Furthermore, the archival documents provided opportunities for triangulation of participant reports. The case study design limits the generalizability of the results to other public health contexts, such as other agencies, interventions, or communities. As such, the extent to which other agencies may have similar or different experiences with EBI de-adoption than those exhibited by this particular case study agency is difficult to determine. However, a strength of a single case study is the ability to contribute to existing theory by providing a valuable description of phenomena not currently captured in existing theoretical frameworks [15]. The results from this study support existing data and suggest how D&I frameworks might be improved.

CONCLUSIONS

Innovative EBIs will emerge as science advances, leading to de-adoption of existing interventions. However, there is limited evidence directly addressing EBI de-adoption. This case study suggests that EBI de-adoption is a distinct stage in the cycle of EBI implementation with consequences for agencies, staff, and communities. We propose de-adoption as a stage of the implementation framework, describe some of the potential outcomes of EBI de-adoption, and suggest how the results from our study might be replicated and extended. Further research on de-adoption is needed to inform policy, as well as to assist agencies in their efforts to end existing programs, and continue to work collaboratively to provide effective prevention services.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Ruth E. Warnke Graduate Fellowship and the Provost’s Distinguished Fellowship awarded to Virginia McKay by the College of Public Health and Human Sciences at the Oregon State University. This research was also supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health grant number T32 MH019960, awarded to Enola Proctor and the National Institute of Mental Health grant number R01 MH085502-01, awarded to M. Margaret Dolcini.

We would like to thank Chenoa Allen for reviewing qualitative codes and acting as a second coder. We would also like to thank Brian R. Flay and Joseph A. Catania for their feedback throughout the drafting of this manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Public health organizations that are de-adopting evidence-based interventions should plan carefully for this final stage of implementation, paying close attention to the impact of changes in staff and communities.

Policy: Policies designed to disseminate evidence-based interventions would benefit from allowing time and providing guidelines on how to successfully discontinue and replace interventions.

Research: Further exploration of intervention de-adoption is needed to understand the process and impact of de-adoption. Dissemination and implementation frameworks in public health would benefit from incorporating de-adoption as a distinct phase of the implementation process.

References

- 1.Ogden T, Fixsen DL. Implementation science: a brief overview and a look ahead. Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 2014;222(1):4–11. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network, 2005; Contract No.: FMHI Publication #231.

- 3.Niven DJ, Mrklas KJ, Holodinsky JK, et al. Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: a scoping review. BMC medicine. 2015;13(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0488-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownson RC, Allen P, Jacob RR, et al. Understanding mis-implementation in public health practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;48(5):543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertram RM, Blase KA, Fixsen DL. Improving programs and outcomes implementation frameworks and organization change. Research on Social Work Practice. 2015;25(4):477–487. doi: 10.1177/1049731514537687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Education Research. 1998;13(1):87–108. doi: 10.1093/her/13.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenhalgh T, Macfarlane F, Barton-Sweeney C, Woodard F. “If We Build It, Will It Stay?” A case study of the sustainability of whole-system change in London. The Milbank Quarterly. 2012;90(3):516–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aral SO, Blanchard JF. The program science initiative: Improving the planning, implementation and evaluation of HIV/STI prevention programs. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2012;88(3):157–159. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman AM, Kuester SA, Jernigan J. Evaluating public health resources: what happens when funding disappears? Preventing Chronic Disease. 2013;10:E190–E196. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aron DC, Lowery J, Tseng CL, Conlin P, Kahwati L. De-implementation of inappropriately tight control (of hypoglycemia) for health: protocol with an example of a research grant application. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins CB, Sapiano TN. Lessons learned from dissemination of evidence-based interventions for HIV prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;51:S140–S147. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High impact HIV prevention. 2015 [cited 4/11/2016]; Available from: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/docs/default-source/general-docs/15-1106-hip-overview-factsheet.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

- 15.Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE Publishing; 2009.

- 16.Kamb, M. L., Fishbein, M., Douglas, J. M., et al. (1998). Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280(13), 1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, et al. Effect of risk-reduction counseling with rapid HIV testing on risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections: the AWARE randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(16):1701–1710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craw, J. A., Gardner, L. I., Marks, G., et al. (2008). Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. Journal of Aquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47(5), 597–606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Frequently asked questions: CTR and RESPECT. [cited 02/01/17]; Available from: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/Files/RESPECT_FAQ.pdf

- 20.Dolcini MM, Catania JA, Gandelman A, Ozer EM. Implementing a brief evidence-based HIV intervention: a mixed methods examination of compliance fidelity. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2014;4(4):424–433. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0268-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]