Abstract

Immunization with myelin components can elicit experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). EAE susceptibility varies between mouse strains, depending on the antigen employed. BL/6 mice are largely resistant to EAE induction with proteolipid protein (PLP), probably a reflection of antigen-specific tolerance. However, the extent and mechanism(s) of tolerance to PLP remain unclear. Here, we identified three PLP epitopes in PLP-deficient BL/6 mice. PLP-sufficient mice did not respond against two of these, whereas tolerance was “leaky” for an epitope with weak predicted MHCII binding, and only this epitope was encephalitogenic. In TCR transgenic mice, the “EAE-susceptibility-associated” epitope was “ignored” by specific CD4 T cells, whereas the “resistance-associated” epitope induced clonal deletion and Treg induction in the thymus. Central tolerance was autoimmune regulator dependent and required expression and presentation of PLP by thymic epithelial cells (TECs). TEC-specific ablation of PLP revealed that peripheral tolerance, mediated by dendritic cells through recessive tolerance mechanisms (deletion and anergy), could largely compensate for a lack of central tolerance. However, adoptive EAE was exacerbated in mice lacking PLP in TECs, pointing toward a non-redundant role of the thymus in dominant tolerance to PLP. Our findings reveal multiple layers of tolerance to a central nervous system autoantigen that vary among epitopes and thereby specify disease susceptibility. Understanding how different modalities of tolerance apply to distinct T cell epitopes of a target in autoimmunity has implications for antigen-specific strategies to therapeutically interfere with unwanted immune reactions against self.

Keywords: autoimmunity, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, central tolerance, antigen presentation, thymic epithelium, epitope, ignorance, myelin proteolipid protein

Introduction

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is an autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that develops in rodents after immunization with whole brain extract or purified myelin components (1, 2). It is characterized by infiltration of autoreactive CD4+ T cells and other inflammatory cells into the CNS. The pathophysiology and clinical symptoms of EAE, including various degrees of paralysis, to some extent resemble the human disease multiple sclerosis (MS) (3).

Depending on the CNS autoantigen employed for immunization, there is a considerable degree of variation between inbred mouse strains with regards to EAE susceptibility and disease course. For instance, B10.PL and PL/J mice are highly susceptible to disease induction with purified myelin basic protein (MBP) or particular MBP peptides, whereas many other mouse strains are resistant to MBP-induced EAE (4–6). The most commonly used encephalitogenic protocol for C57BL/6 (BL/6) mice relies on a particular myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide and results in a monophasic disease. Upon immunization with myelin proteolipid protein (PLP), SJL/J mice develop a fulminant form of relapsing-remitting EAE, whereas most other strains, including BL/6, are considered largely “resistant” to PLP-induced EAE (6–8).

Numerous genetic and non-genetic factors have been reported to modulate EAE susceptibility and disease severity in a complex fashion, but in many cases, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive (9, 10). Among the various inheritable traits that control the susceptibility to EAE in mice and MS in humans, the MHC is the by far most prominently associated genetic locus (9–11). Moreover, it is well established that the magnitude of the in vitro CD4 T cell response to myelin antigens in classical immunization recall experiments is a robust correlate of disease susceptibility. For instance, PLP-EAE susceptible SJL mice display a vigorous CD4 T cell response upon immunization with PLP protein or particular pools of PLP-peptides, whereas resistant strains such as BL/6, BALB/c, or CBA exhibit a much weaker response (7, 8). Although none of the strains that are susceptible to EAE induction with a given CNS protein develop spontaneous disease, it is undisputed that the composition and responsiveness of their CD4 T cell compartment is a critical determinant of disease susceptibility.

CD4 T cells reactive to MBP or PLP are constituents of the normal human T cell repertoire (12–14). Limitations inherent to human studies so far preclude a conclusive assessment whether this in fact indicates the absence of antigen-specific tolerance or whether these autoreactive cells represent a residual fraction of the repertoire that has escaped tolerance induction. However, a precise understanding of how different modalities of tolerance shape the T cell reactivity to CNS autoantigens and how recessive modes of tolerance, i.e., deletion and anergy, or dominant, i.e., Treg-mediated, tolerance cooperate and/or differentially apply to distinct T cell epitopes of a target in autoimmunity has implications for strategies that aim to therapeutically interfere with unwanted immune reactions against the CNS.

Mice lacking particular CNS autoantigens have been used to assess whether the magnitude and quality of the response to a given myelin protein is influenced by antigen-specific tolerance. MOG-specific CD4 T cell responses were found to be identical between Mog+/+ and Mog–/– mice, and it was suggested that this apparent lack of tolerance to MOG explains the high pathogenicity of the anti-MOG immune response in several mouse strains (15). By contrast, Mbp+/+ mice on the C3H or BALB/c background displayed a substantially weaker CD4 T cell response to MBP immunization than MBP-deficient mice, indicating that their T cell repertoire is somehow curtailed by endogenously expressed MBP (16, 17). Using PLP knockout mice, we demonstrated that the relatively moderate response of PLP-sufficient BL/6 mice to immunization with PLP is a consequence of specific tolerance rather than the reflection of an inherently low responsiveness (8).

The evidence for specific tolerance to the myelin antigens MBP and PLP is at odds with the originally held view that CNS proteins are topologically sequestered from the immune system. However, the idea that myelin antigens are exclusively expressed behind the blood–brain barrier, and thereby excluded from tolerance induction, has been largely abandoned (1). In case of PLP, mRNA transcripts are readily detectable in primary and secondary lymphoid organs (18, 19), and thymus chimeras revealed that the physiological expression of PLP in thymic epithelial cells (TECs) was sufficient to recapitulate the diminished CD4 response of PLP-sufficient BL/6 mice (8).

CD4 T cell tolerance to PLP in the “PLP-EAE-resistant” BL/6 strain has so far only been “operationally” defined as a reduced polyclonal CD4 T cell recall response upon immunization compared to PLP-deficient mice. However, it was unclear through which cellular mechanism(s), that is, clonal deletion and/or diversion into the Foxp3+ Treg lineage, tolerance is achieved, and whether these modes of tolerance similarly apply to distinct epitopes of PLP. Furthermore, it remained open whether intrathymic PLP expression was “essential” for tolerance to PLP, both in terms of its impact on the fate of PLP-specific CD4 T cells as well as disease susceptibility. In the present study, we employed two novel strains of TCR transgenic mice in conjunction with strategies to selectively interfere with PLP expression or presentation in distinct cellular compartments to obtain a comprehensive view of the modalities of CD4 T cell tolerance to PLP.

Results

PLP Epitopes and Epitope-Specific EAE Susceptibility in BL/6 Mice

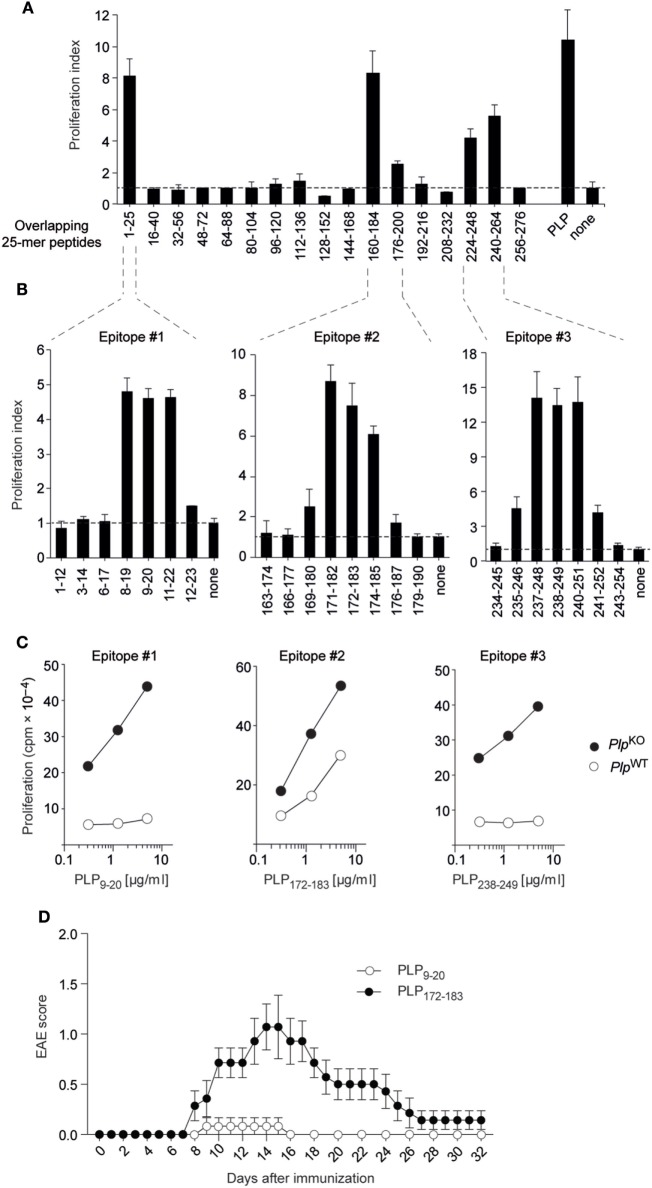

We initially broadly defined the targets of CD4 T cell reactivity to PLP in “non-tolerant” PlpKO BL/6 mice through re-stimulating lymph node T cells from immunized mice with a set of overlapping 25-mer peptides corresponding to the entire PLP protein (Figure 1A) (8). The PLPko mouse used in our study has been characterized extensively with regards to a verification of the absence of PLP protein or any truncated version thereof (20). Overlapping 12-mer peptides spanning these regions were then used to precisely fine-map the respective I-Ab-restricted epitopes (Figure 1B). This revealed three core 9-mer epitopes spanning amino acids 11–19, 174–182, and 240–248, in the following referred to as epitopes #1, #2, and #3, respectively. The experimental epitope definition was retrospectively combined with an in silico prediction of T cell epitopes using the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (IEDB) (21, 22). The IEDB algorithm predicts and ranks the relative binding strengths of all 15-mer peptides that can be generated from a given protein. For PLP, the seven 15-mer peptides containing epitope #3 were among the top eight predicted I-Ab binders, and all of the 15-mers harboring epitope #1 were ranked between positions 10 and 20 (Figure S1 in Supplementary Material). Epitope #2-containing 15-mers had the weakest binding scores and ranked between positions 33 and 57. Consistent with this relative ranking, an in silico prediction of MHC-binding affinities using the SSM-align algorithm (23) yielded mean IC50 values of 168 ± 61 nM for epitope #3-containing peptides and 715 ± 262 or 1,533 ± 498 nM for peptides containing epitopes #1 or #2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Proteolipid protein (PLP) epitopes and epitope-specific experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) susceptibility in BL/6 mice. (A) PlpKO BL/6 mice were immunized with PLP protein. Nine days later, draining lymph node cells were re-stimulated in vitro with overlapping 25-mers spanning the entire PLP protein. Responses to peptides are shown as proliferation indices. (B) Fine mapping of epitopes with overlapping 12-mer peptides. (C) CD4 T cell recall response of PlpKO or PlpWT mice upon immunization with 12-mer peptides containing the core epitopes #1, #2, and #3. (D) EAE symptoms in PlpWT mice upon immunization with the 12-mer peptides PLP9–20 (n = 6) or PLP172–183 (n = 7) together with administration of pertussis toxin on days 0 and 2. Data in panels (A–C) are from individual mice representative for n ≥ 5 each.

Compared to the pronounced CD4 T cell responses to all three epitopes in PlpKO mice, there was essentially no recall response to epitopes #1 and #3 with cells from immunized PlpWT mice (Figure 1C). However, a robust response to epitope #2 was observed, although the magnitude of this response was somewhat attenuated as compared to PlpKO mice. To assess how the absence or presence of CD4 T cell responsiveness to these PLP epitopes correlated with EAE susceptibility, we immunized PlpWT mice with epitopes #1, #2, or #3 according to the EAE protocol. Whereas “EAE-immunization” with epitope #1 and epitope #3 failed to promote disease symptoms, epitope #2 elicited EAE with a typical acute disease course, that is, onset of symptoms at around day 8, followed by a disease peak at days 14–16 and subsequent remission (Figure 1D, and data not shown).

Together, these observations reveal a differential impact of self-tolerance on CD4 T cell responses to three distinct epitopes of PLP in BL/6 mice. Tolerance was “leaky” for the epitope with the lowest predicted MHC II-binding capacity. Moreover, the absence or presence of recall responsiveness to a given epitope tightly correlated with resistance or susceptibility to EAE, respectively.

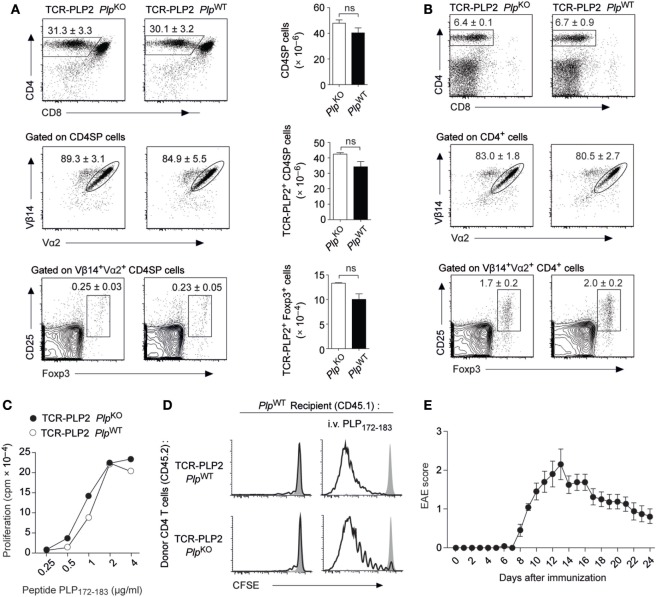

“Ignorance” toward PLP Epitope #2

In order to follow the fate of epitope #2-specific CD4 T cells and characterize the apparent “failure” of tolerance induction to this epitope, we generated transgenic mice (TCR-PLP2) expressing a PLP172–183-specific TCR that was derived from immunized PlpKO mice. In TCR-PLP2 PlpKO mice, i.e., in the absence of cognate self-antigen, there was a pronounced skewing toward the CD4 lineage in the thymus, and the vast majority of CD4 single-positive (SP) thymocytes expressed the transgenic TCR chains (Vα2 and Vβ14) (Figure 2A). A very small fraction of Vα2+Vβ14+ CD4 SP cells expressed Foxp3. Importantly, none of these parameters was altered in TCR-PLP2 PlpWT mice, indicating that PLP epitope #2-specific CD4 T cells were not subject to central tolerance induction (Figure 2A). Also in the periphery, neither the frequency of CD4 T cells nor their expression of Vα2+Vβ14+ was different between TCR-PLP2 mice on Plp-deficient or -sufficient background, suggesting that epitope #2-specific T cells in both settings persisted as naïve cells (Figure 2B). Consistent with this, purified CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP2 PlpWT displayed an identical in vitro proliferative response to stimulation with titrated amounts of PLP172–183 as cells from TCR-PLP2 PlpKO controls (Figure 2C). Adoptively transferred naïve TCR-PLP2 cells from PlpKO mice persisted in a non-dividing state in PlpWT recipients, whereas cells from both TCR-PLP2 PlpKO or TCR-PLP2 PlpWT origin proliferated upon challenge with cognate peptide, irrespective of being parked in a Plp-deficient or -sufficient recipient (Figure 2D). These findings further substantiated the idea that PLP epitope #2 of natural origin is not sufficiently processed and presented from physiological sources to become “visible” to peripheral CD4 T cells. However, “EAE-immunization” with peptide PLP172–183 elicited EAE in TCR-PLP2 PlpWT mice, suggesting that these TCR transgenic cells can turn into pathogenic effectors upon appropriate stimulation and recognize the physiologically processed epitope (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

“Ignorance” toward proteolipid protein (PLP) epitope #2 in TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice. (A) Thymocyte subset composition of TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP2+ cells (Vα2+Vβ14+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle), and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP2+ CD4SP cells is indicated (n ≥ 8 per genotype). The bar diagrams on the right show absolute cell numbers of the respective subsets. (B) Peripheral phenotype of TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4 T cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP2+ cells (Vα2+Vβ14+) among gated CD4 T cells (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP2+ CD4 T cells (lower) are indicated (n ≥ 8 per genotype). (C) Proliferation of purified CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background upon in vitro stimulation with PLP172–183. Data are from individual mice representative for n ≥ 3 each. (D) CFSE-labeled CD4 T cells from PlpKO or PlpWT TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice (CD45.2) were i.v. injected into PlpWT recipients (CD45.1) that had (right) or had not (left) been immunized with PLP172–183 the day before. Four days later, lymph node cells were harvested and analyzed by FACS. Histograms show the CFSE intensity of gated CD4+CD45.2+ cells. The filled histogram overlay is from undivided control cells in a PlpKO recipient. Data are representative of three experiments with n = 5 each. (E) Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) disease course in TCR-PLP2 PlpWT mice upon immunization with the 12-mer peptide PLP172–183 together with administration of pertussis toxin on days 0 and 2 (n = 14).

Thus, PLP172–183-specific TCR transgenic CD4 T cells with encephalitogenic potential were not subject to tolerance induction. Instead, they persisted in a state of “ignorance” that was broken upon immunogenic delivery of cognate antigen, in line with the capacity of PLP172–183 immunization to elicit EAE in a polyclonal setting.

Spontaneous EAE in TCR-PLP2 Rag1–/– Mice

The expression of an endogenously rearranged TCRα chain together with the transgenic TCR elements may result in a dual specificity and thereby complicate the interpretation of TCR instructed cell fate decisions. For instance, the emergence of a small population of Foxp3+ cells among Vα2+Vβ14+ cells in both thymus and periphery of TCR-PLP2 mice was PLP independent, and thus likely to reflect a “cryptic autoreactivity” conveyed by endogenous TCR rearrangements. To assess the consequences of excluding endogenous TCR rearrangements, we generated Rag1-deficient TCR-PLP2 mice. Irrespective of an intact Plp gene, this resulted in the virtual absence of Foxp3+ cells from thymus and periphery. Importantly, as in Rag1+/+ mice, the frequency and absolute number TCR-PLP2+ cells was indistinguishable between Plp-deficient or –sufficient mice, confirming that their cognate antigen PLP172–183 is essentially “invisible” to these cells (Figures 3A,B). However, in contrast to mice on Rag1+/+ background, PLP-sufficient TCR-PLP2 Rag1–/– mice developed “spontaneous” EAE starting at around 5 weeks of age (Figures 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice on Rag1-deficient background. (A) Thymocyte subset composition of TCR-PLP2 transgenic Rag1–/– mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP2+ cells (Vα2+Vβ14+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP2+ CD4SP cells (lower) is indicated (n ≥ 9 each). The bar diagrams on the right show absolute cell numbers of the respective subsets. (B) Peripheral phenotype of TCR-PLP2 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4 T cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP2+ cells (Vα2+Vβ14+) among gated CD4 T cells (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP2+ CD4 T cells (lower) are indicated (n ≥ 9 each per genotype). (C,D) Cumulative incidence and maximum disease score of spontaneous EAE in TCR-PLP2 Rag1–/– (n = 21) and TCR-PLP2 Rag1+/+ mice (n = 6).

These observations confirmed that TCR-PLP2+ CD4 T cells can be pathogenic, yet do not encounter cognate antigen during thymic differentiation or in the periphery, so that they initially remain in a state of “ignorance.” However, in a truly monoclonal setting their latent autoimmune potential can with increasing age be “spontaneously” unleashed, possibly facilitated by the lack of Treg cells.

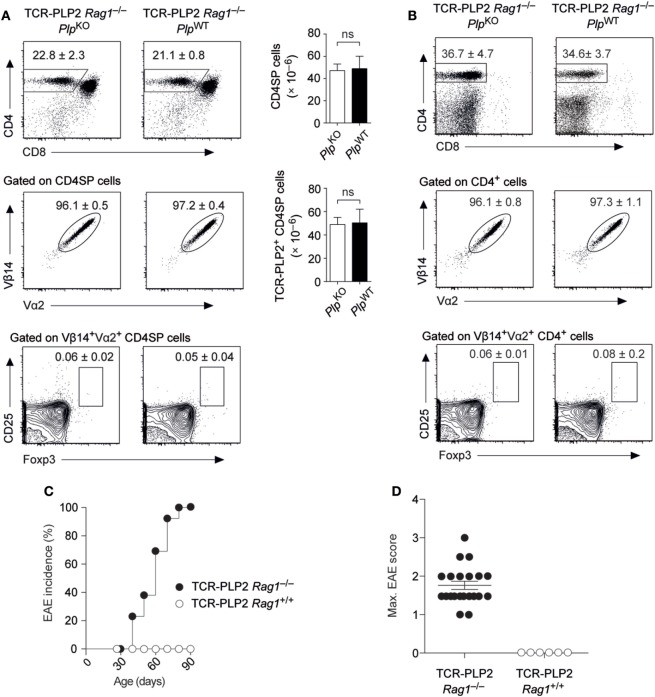

Central Tolerance toward PLP Epitope #1

In contrast to our observations with the “EAE-susceptibility-associated” epitope #2, BL/6 mice did not display a CD4 T cell recall response to epitope #1 and were resistant to EAE induction by immunization with this peptide (see Figure 1). In order to characterize the mode of CD4 T cell tolerance induction to the “EAE-resistance-associated” epitope #1, we generated a PLP11–19-specific TCR transgenic mouse strain (TCR-PLP1). Compared to TCR-PLP1 PlpKO controls, the frequency and number of CD4 SP cells in the thymus of TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice were strongly diminished (Figure 4A). Moreover, whereas in PLP-deficient mice, around 85% of CD4 SP cells expressed both transgenic TCR chains, only about 50% of CD4 SP cells were Vα3.2+Vβ6+ in PLP-sufficient mice. Among the remaining TCR-PLP1+ CD4 SP cells in PLPWT mice, an elevated frequency of cells was Foxp3+, whereby in terms of absolute numbers, this reflected an only moderate, yet significant, increase (Figure 4A). In peripheral lymphoid organs of TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice, the proportion of CD4+ T cells was reduced by about fourfold when compared to PlpKO controls (Figure 4B). Whereas in PLP-deficient mice, around 75% of peripheral CD4 T cells expressed the transgenic TCR, less than 10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells did so in TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice. TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells contained only a minute fraction of Foxp3+ cells in PLP-deficient mice, while Foxp3+ cells constituted more than a third of TCR-PLP1+ cells in PlpWT mice (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Central tolerance to proteolipid protein (PLP) epitope #1 in TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice. (A) Thymocyte subset composition of TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4SP cells is indicated (n ≥ 8 mice per genotype). The bar diagrams on the right show absolute cell numbers of the respective subsets. (B) Peripheral phenotype of TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice on PlpKO or PlpWT background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4 T cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4 T cells (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells (lower) are indicated (n ≥ 8 mice per genotype). (C) Purified naïve TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice were labeled with CFSE and cultured in vitro with irradiated splenoctyes and peptide PLP9–20 in the presence or absence of titrated numbers of TCR-PLP1+CD25+ CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice. The histogram overlay shows a representative CFSE profile on day 3 of cells when cultured alone (gray histogram) or with an equal number of Treg cells (open histogram). The diagram on the right shows the dose/response curve with different ratios of Treg cells. (D) Purified TCR-PLP1+CD25– CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpWT (CD45.2) or PlpKO background (CD45.1/2) were labeled with CFSE and co-injected i.v. into PlpWT (CD45.1) recipients. Three days after transfer, lymph node cells were harvested and stained for CD45.1 and CD45.2. The dot plot on the left shows the relative abundance of cells of PlpWT (CD45.2; red gate) or PlpKO origin (CD45.1/2; blue gate). The histogram overlay on the right shows the CFSE profile of the respective cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments with n ≥ 3 each. (E) Disease course of “adoptive” experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in Rag1–/– recipients after transfer of Th1- or Th17-polarized TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice.

To ask whether the segregation of peripheral TCR-PLP1+ cells in PLP-sufficient mice into Foxp3+ and Foxp3– cells reflected the co-existence of Treg cells and bona fide naïve cells, we assessed the functional properties of both subsets. Purified CD25+ cells indeed suppressed the proliferation of naïve TCR-PLP1 Tconv cells in an antigen-specific manner (Figure 4C). However, whereas naïve TCR-PLP1 cells from PLP-deficient donors vigorously proliferated upon adoptive transfer into PlpWT recipients, illustrating that I-Ab/PLP11–19 ligands of physiological origin are constitutively “visible” in peripheral lymphoid tissues, co-transferred CD25– TCR-PLP1+ cells from TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice did not proliferate, indicating that these cells were in a cell intrinsic refractory state of anergy (Figure 4D).

We did not observe spontaneous EAE in TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice. In order to assess the “autoimmune potential” of TCR-PLP1 CD4 T cells, we generated TCR-PLP1 Rag1–/– PlpKO mice. Monoclonal TCR-PLP1 CD4 T cells from these donors were differentiated in vitro into Th1 or Th17 effectors and subsequently transferred into Rag1–/– PlpWT recipients, revealing that both Th1- or Th17-polarized cells induced EAE, albeit with a slightly lower maximal disease score in the case of Th1 cells (Figure 4E).

In sum, these data showed that PLP epitope #1-specific CD4 T cells bear autoimmune potential, which was at least in part harnessed through tolerance induction during intrathymic T cell differentiation. The predominant mode of central tolerance induction among TCR-PLP1 CD4 T cells appeared to be clonal deletion. At the same time, a fraction of cells differentiated into Treg cells and efficiently seeded peripheral lymphoid organs, were they co-existed with anergic Foxp3–CD25– TCR-PLP1 cells.

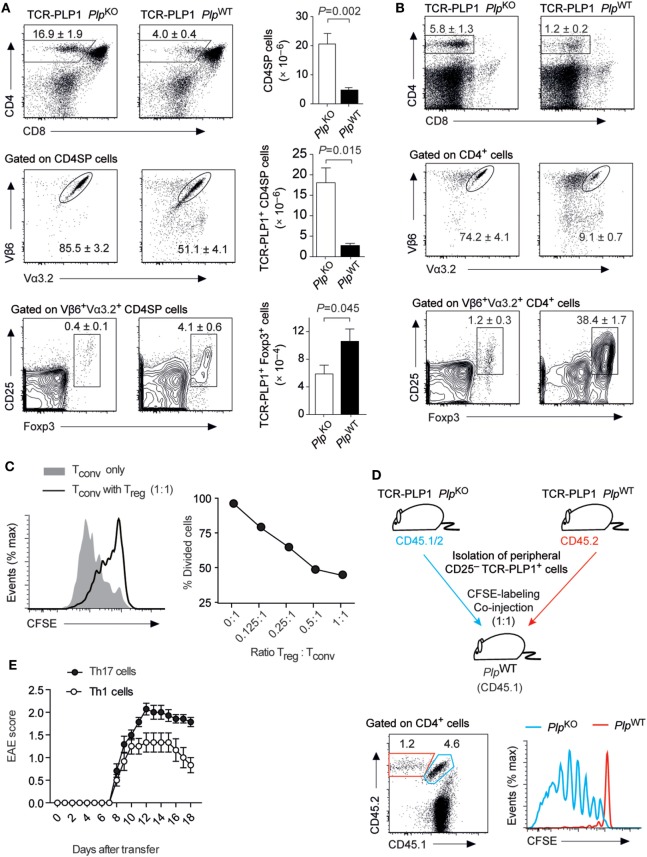

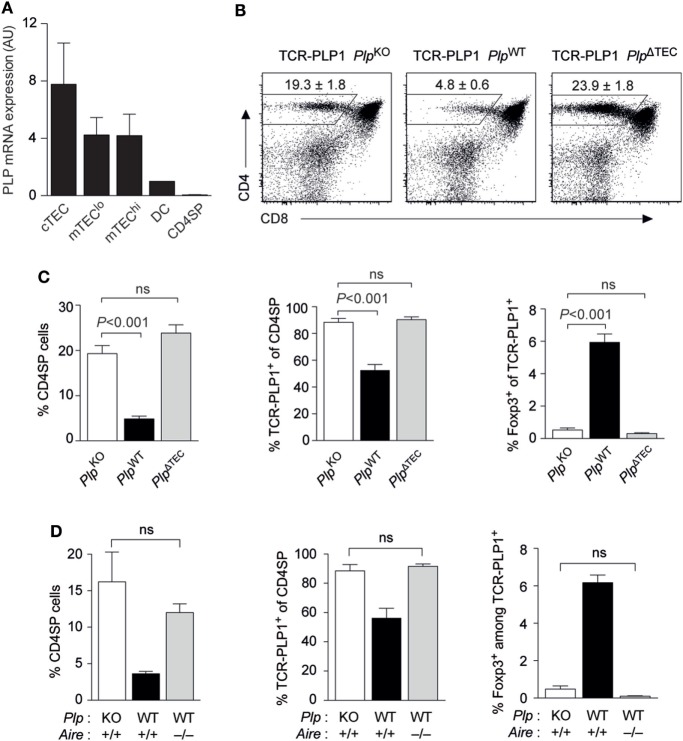

TEC-Derived PLP and Autoimmune Regulator (Aire) Are Crucial for Central Tolerance to Epitope #1

We previously reported that PlpWT → PlpKO thymus chimeras, where TECs are the sole potential source of tolerizing antigen, recapitulated the “operational tolerance” of PlpWT mice, as evident from a similar reduction of the CD4 T cell recall response after immunization compared to PlpKO mice (8). This indicated that PLP expression in TECs was sufficient for CD4 T cell tolerance. Given that PLP transcripts are also detectable in dendritic cells (DCs), albeit at substantially lower levels (Figure 5A), we wondered whether TEC-derived PLP was in fact essential for central tolerance, or whether there was a degree of redundancy with other potential intra- or extrathymic sources of tolerizing antigen. To address this, we generated mice with a conditional deletion of the Plp gene in TECs (Foxn1-Cre Plpfloxed), in the following referred to as PlpΔTEC. Strikingly, all manifestations of central tolerance in the TCR-PLP1 system were abolished in PlpΔTEC mice (Figures 5B,C). Thus, both the frequency of CD4 SP cells as well as the proportion of Vα3.2+Vβ6+ among CD4 SP cells were indistinguishable from those observed in the complete absence of PLP in PlpKO mice. In the same vein, the frequency of Foxp3+ cells among TCR-PLP1 CD4 SP cells of PlpΔTEC mice was identical to that in “antigen-free” PlpKO mice.

Figure 5.

Thymic epithelial cell (TEC)-derived proteolipid protein (PLP) and autoimmune regulator (Aire) are crucial for central tolerance to epitope #1. (A) Relative abundance of PLP mRNA in different subsets of TECs, thymic dendritic cells (DCs), and CD4 single-positive (SP) cells. Values are indicated as arbitrary units (AU) normalized to expression in DCs. Data are representative of two independent experiments with pooled cells from ≥3 mice. (B) CD4 versus CD8 staining of thymus cells from TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice on PlpKO, PlpWT, or PlpΔTEC background. (C) Average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (left), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4SP cells (right) in TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO, PlpWT, or PlpΔTEC background (n = 4 each). (D) Average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (left), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle), and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4SP cells (right) in TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO (n = 3), PlpWT (n = 3), or PlpWT Aire–/– (n = 6) background.

The “promiscuous” transcription of peripheral antigens in the thymus is mostly confined to “mature” medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) expressing high levels of MHCII, and this reflects the predominant expression of the transcriptional activator Aire in this cell type. PLP’s intrathymic expression pattern is rather untypical for a promiscuously expressed tissue-restricted antigen in that it is also detectable in “immature” (MHCIIlo) mTECs and at comparable levels also in cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) (Figure 5A). Since MHCIIlo mTECs and cTECs barely, or not at all, express Aire, respectively, we hypothesized that central tolerance to PLP was Aire independent. However, both negative selection and Treg induction were abrogated in Aire-deficient TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice, so that the thymocyte composition in these mice phenocopied that in TCR-PLP1 PlpKO and TCR-PLP1 PlpΔTEC mice (Figure 5D).

Together, these data showed that PLP expression in TECs was necessary and sufficient for central tolerance induction in PLP epitope #1-specific CD4 T cells. Intriguingly, although PLP transcripts were not confined to Aire-expressing mTEChi cells, intrathymic tolerance induction to PLP depended upon Aire.

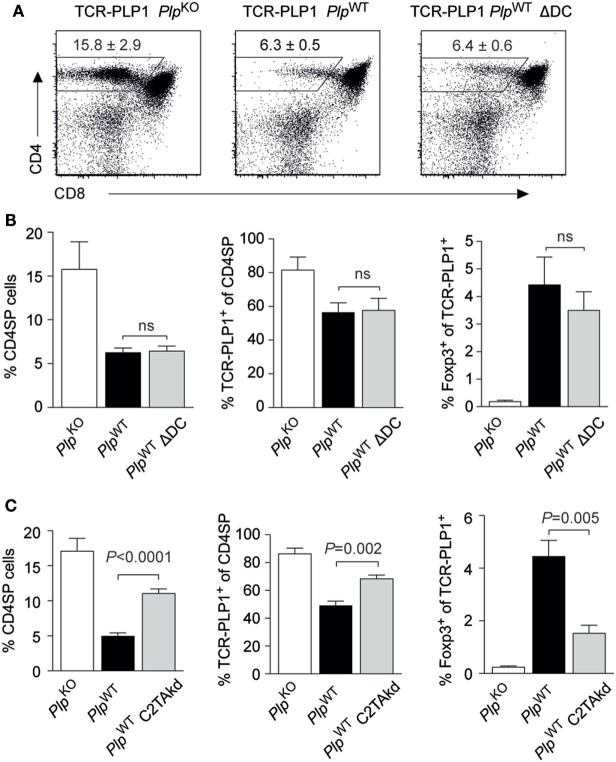

Central PLP-Tolerance Is DC Independent and Requires Presentation by mTECs

Self-antigens that are expressed in TECs may be presented to developing CD4 T cells via two distinct, yet mutually not exclusive routes (24). On the one hand, tolerogenic encounter of such antigens by CD4 T cells may depend upon “antigen handover” and presentation by thymic DCs. On the other hand, mTECs, or TECs in general, may autonomously present endogenously expressed antigen to CD4 T cells via unconventional MHC class II-loading pathways (25).

Two experimental systems were employed to address this issue in the TCR-PLP1 model. First, we generated TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice lacking DCs as a result of diphtheria toxin expression in CD11c+ cells (“ΔDC” mice) (26). Despite the lack of DCs, the thymic phenotype of these mice was essentially identical to that of DC-sufficient TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice (Figures 6A,B). Second, we generated TCR-PLP1 mice with an impaired capacity to directly present antigen on mTECs as a consequence of mTEC-specific knock-down of MHC class II (“C2TAkd” mice) (27). All manifestations of central tolerance induction to PLP epitope #1 were significantly attenuated in these mice. Specifically, the proportion of CD4 SP cells, the percentage of Vα3.2+Vβ6+ among CD4 SP cells and the relative abundance of TCR-PLP1+ Foxp3+ CD4 SP cells were all partially “rescued,” i.e., they ranged in between TCR-PLP1 PlpWT and TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Central proteolipid protein (PLP) tolerance is dendritic cell (DC) independent and requires direct presentation by medullary thymic epithelial cells. (A) CD4 versus CD8 staining of thymus cells from TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice on PlpKO, PlpWT, or PlpWT ΔDC background. (B) Average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (left), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4SP cells (right) in TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO (n = 3), PlpWT (n = 7), or PlpWT ΔDC (n = 7) background. (C) Average frequency ± SEM of CD4SP cells (left), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4SP thymocytes (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4SP cells (right) in TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO (n = 6), PlpWT (n = 8), or PlpWT C2TAkd (n = 5) background.

Collectively, these findings documented a non-redundant role of mTECs for central tolerance induction to PLP epitope #1 through direct presentation of endogenously derived antigen. Intrathymic presentation by DCs, if occurring at all, was dispensable for central tolerance.

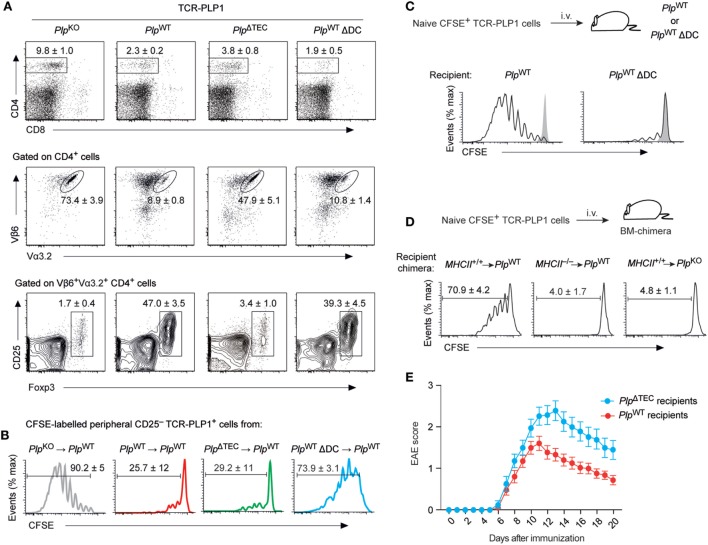

Peripheral Tolerance in PlpΔTEC Mice

Although the conditional deletion of PLP in TECs abolished central tolerance to PLP epitope #1, neither PlpΔTEC mice nor TCR-PLP1 transgenic PlpΔTEC mice developed spontaneous EAE (data not shown). Even the active immunization of these mice with the epitope #1-containing peptide PLP11–20 according to the “EAE protocol” failed to promote disease symptoms (data not shown), suggesting that peripheral tolerance mechanisms were able to compensate for the absence of intrathymic censorship.

Indeed, the CD4 T cell compartment in secondary lymphoid tissues of TCR-PLP1 PlpΔTEC mice exhibited clear indications of peripheral antigen encounter. Thus, despite an identical thymocyte composition as in TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice (see Figures 5B,C), there was a marked reduction in the overall size of the peripheral CD4 T cell population in TCR-PLP1 PlpΔTEC mice (Figure 7A). Although this resembled a similar CD4 T cell reduction in TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice, PlpΔTEC mice had a substantially higher percentage of TCR-PLP1+ cells among peripheral CD4 T cells (47.9 ± 5.1 versus 8.9 ± 0.8%; P < 0.001). The proportion of Foxp3+ Treg cells among TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells in PlpΔTEC mice was as low as in fully PLP-deficient mice, suggesting that PLP expression in TECs was crucial for the establishment of the prominent peripheral TCR-PLP1+Foxp3+ Treg population in TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice. By contrast, the CD25– subset of TCR-PLP1+ cells from PlpΔTEC mice functionally resembled the corresponding population in PlpWT mice with respect to being refractory to antigenic stimulation in vivo (Figure 7B), indicating that anergy induction occurred independent of thymic PLP encounter. Consistent with this, the anergy marker FR4 was similarly elevated on Foxp3–CD25–TCR-PLP1+ cells from both PlpΔTEC and PlpWT mice (Figure S2 in Supplementary Material). These data showed that in the absence of PLP expression in TECs, peripheral tolerance toward PLP epitope #1 appeared to operate via deletional mechanisms and anergy induction rather than Treg conversion.

Figure 7.

Phenotype and functionality of TCR-PLP1 cells in PlpΔTEC and Δdendritic cell (DC) mice. (A) Peripheral phenotype of TCR-PLP1 transgenic mice on PlpKO (n = 8), PlpWT (n = 9), PlpΔTEC (n = 3), or PlpWT ΔDC (n = 7) background. The average frequency ± SEM of CD4 T cells (upper plot), TCR-PLP1+ cells (Vα3.2+Vβ6+) among gated CD4 T cells (middle) and CD25+Foxp3+ cells among gated TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells (lower) are indicated. (B) Purified TCR-PLP1+CD25– CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO, PlpWT, PlpΔTEC, or PlpWT ΔDC background (all CD45.2) were labeled with CFSE and injected i.v. into PlpWT (CD45.1) recipients. Three days after transfer, lymph node cells were harvested and CFSE dilution was assessed on gated CD45.2+ cells. Data are representative of n ≥ 4. (C) Purified TCR-PLP1+CD25–CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO background (CD45.1) were labeled with CFSE and injected i.v. into PlpWT or PlpWT ΔDC recipients (CD45.2). Three days after transfer, lymph node cells were harvested and CFSE dilution was assessed on gated CD45.2+ cells. The gray histogram shows the CFSE-intensity of cells transferred into control PlpKO recipients. Data are representative of n ≥ 6. (D) Purified TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cells from TCR-PLP1 mice on PlpKO background (CD45.1) were labeled with CFSE and i.v. injected into bone marrow (BM)-chimeric recipients (MHCII+/+ → PlpWT controls, MHCII–/– → PlpWT, and MHCII+/+ → PlpKO) (CD45.2). Three days after transfer, lymph node cells were harvested and CFSE dilution was assessed on gated CD45.2+ cells. (E) Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) disease course in male PlpWT or PlpΔTEC mice (non-TCR-transgenic) that had been injected i.v. with 5 × 106 TCR-PLP1+ T cells from TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice 6 h before administration of PLP9–20 in CFA. Data are from n ≥ 14 each.

Peripheral Tolerance Induction through Presentation of “Non-Hematopoietic” PLP by DCs

Ablation of thymic PLP expression in PlpΔTEC mice revealed that “downstream” of the thymus, peripheral antigen encounter could shape the fate of TCR-PLP1 CD4 T cells. To ask whether presentation of I-Ab/PLP11–19 ligands in the periphery was DC dependent, we transferred CFSE-labeled TCR-PLP1 cells into DC-sufficient or DC-deficient PlpWT mice. Whereas transferred cells vigorously proliferated in control recipients, they failed to do so in ΔDC mice, indicating that antigen presentation by DCs was crucially involved (Figure 7C).

To address whether the display of PLP epitope #1 by peripheral DCs reflected the presentation of endogenously derived PLP or required the uptake and presentation of PLP from a non-hematopoietic source, we performed analogous experiments with bone marrow (BM) chimeric recipients (Figure 7D). Whereas TCR-PLP1 cells underwent proliferation when transferred into MHCII+/+ → PlpWT control chimeras, they remained quiescent in MHCII–/– → PlpWT chimeras, consistent with a requirement for antigen presentation by DCs. Importantly, transferred cells likewise failed to proliferate in MHCII+/+ → PlpKO chimeras, establishing that PLP from a non-hematopoietic source was crucially required.

Considering that in PlpWT mice, PLP was concomitantly presented intrathymically by mTECs as well as in the periphery by DCs, we wondered in how far the peripheral composition and functionality of TCR-PLP1+ cells was shaped by thymic output versus peripheral tolerance induction. The striking phenotypic similarity between DC-sufficient and DC-deficient TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice (compare Figures 6A,B) also applied to the periphery (Figure 7A). Specifically, total CD4 cells were reduced to the same extent, and the comparably small populations of TCR-PLP1+ cells in both genotypes similarly segregated into Foxp3+ Tregs and Foxp3–CD25– cells, suggesting that the overall composition of the TCR-PLP1+ CD4 T cell pool was mostly shaped by thymic output. Interestingly, though, CD25– cells from ΔDC mice proliferated upon adoptive transfer into PlpWT mice (Figure 7B), indicating that the anergic state of these cells in DC-sufficient mice is induced and/or maintained by peripheral antigen encounter on DCs.

Our findings suggested that the lack of thymic negative selection in TCR-PLP1 PlpΔTEC mice could be largely compensated by DC-mediated peripheral deletion and anergy induction, while the “normal” formation of a PLP-specific peripheral Treg compartment appeared to depend on thymic Treg induction by mTECs. Given this differential degree of redundancy between thymic and peripheral antigen encounter with respect to recessive versus dominant tolerance mechanisms (deletion and anergy versus Treg induction, respectively), we sought evidence for a defect in dominant tolerance to PLP in the polyclonal repertoire of non-TCR transgenic PlpΔTEC mice. To do so, we adoptively transferred naïve TCR-PLP1 cells into PlpΔTEC or PlpWT mice simultaneously to “EAE-immunization” with PLP11–20. This resulted in the development of EAE in both genotypes. However, the disease course was more severe in mice lacking thymic PLP expression, consistent with a “less robust” state of tolerance, possibly owing to lack or diminution of PLP-specific Treg cells (Figure 7E).

Discussion

The present study establishes a number of salient features of tolerance to PLP in BL/6 mice. The fine mapping of the protein domains against which the uncensored CD4 T cell repertoire of PLP-deficient mice reacts identified three core I-Ab-restricted epitopes. PLP-sufficient mice failed to mount a response against epitopes #1 and #3, yet reacted toward epitope #2. This correlated tightly with the encephalitogenic potential of the respective peptides when administered according to the standard EAE protocol, indicating that the extent of CD4 T cell tolerance varied between epitopes. Interestingly, epitope #2 overlaps with a peptide that is commonly used to elicit EAE in SJL/J (H-2s) mice, but was shown to bear encephalitogenic potential also in BL/6 mice (28, 29).

The precise determinants underlying the differential degree of tolerance of BL/6 mice to the I-Ab restricted epitopes #1 (PLP11–19) and #3 (PLP240–248) on the one hand and epitope #2 (PLP174–182) on the other hand remain to be established. In SJL mice, a similar lack of tolerance to the I-As-restricted encephalitogenic peptide PLP139–151, at least as far as central tolerance induction is concerned, is readily explained by the fact that expression of PLP in TECs is confined to the DM20 splice variant that lacks the amino acid residues 116–151 (8, 30). However, such a splicing-related “hole in the proteome” cannot account for the leakiness of central tolerance to epitope #2, since all three I-Ab-restricted PLP epitopes are contained within the intrathymically expressed DM20 protein isoform and should therefore be available for processing and presentation in stoichiometric amounts. Hence, the most likely explanation for the lack of central tolerance to epitope #2 might be that this peptide is a weaker I-Ab binder than epitopes #1 and #3. A scenario whereby escape from central tolerance due to weak or unfavorable MHCII binding explains the autoimmune association of a given self-epitope is reminiscent of what has been suggested regarding the major insulin-epitope recognized by diabetogenic CD4 T cells in NOD mice (H-2q7) (31, 32) and the encephalitogenic MBP epitope MBP1–11 in H-2u mice (33). An experimental verification of the predicted I-Ab-binding hierarchy of PLP epitopes will be necessary to further substantiate this notion.

Weak I-Ab binding would also offer an explanation why epitope #2 appears to be insufficiently presented in the periphery and therefore “ignored” by specific CD4 T cells, whereas epitope #1 is constitutively available for T cell recognition and, under steady state conditions, peripheral tolerance induction. Despite the caveat that our study is limited to the fate of individual transgenic TCRs, we deem it likely that escape from thymic censorship and “ignorance” in the periphery is representative of the fate of a sizeable fraction of epitope #2-specific CD4 T cells in the polyclonal repertoire. Thus, despite intrathymic expression of PLP, EAE can be elicited in BL/6 mice by immunogenic delivery of this determinant, indicating that a sufficiently large pool of “naïve” epitope #2 reactive CD4 T cells exists.

Breeding onto a Rag-deficient background, although only modestly increasing the frequency of clonotype-positive cells, rendered TCR-PLP2 mice susceptible to spontaneous EAE development. This is reminiscent of a similar phenomenon in H-2u mice carrying an MBP1–11-specific TCR (34). In the latter model, it was shown that Treg cells, whose differentiation requires endogenous TCRα rearrangements conferring specificity to unknown self-antigens in addition to the MBP-specificity, are crucial to prevent disease (35–37). Where and how TCR-PLP2 cells are primed at the onset of EAE in TCR-PLP2 Rag1–/– mice remain to be established. Yet, the spontaneous occurrence of disease in these animals illustrates that the presumed “invisibility” of PLP epitope #2 and the ensuing “ignorance” of specific CD4 T cells reflects a rather fragile tolerance state that may depend upon a delicate balance of active control mechanisms.

In contrast to the observations with epitope #2, immunization with epitopes #1 or #3 failed to promote a recall response and lacked encephalitogenic potential, and epitope #1 reactive TCR transgenic CD4 T cells were subject to central tolerance induction in the thymus. We consider it likely that central tolerance induction generally applies to epitope #1-specific CD4 T cells exceeding a certain affinity threshold and by inference also to epitope #3 reactive T cells. To which extent this occurs through clonal deletion or clonal diversion into the Treg lineage for a given epitope remains to be established. In this regard, the precise mapping of I-Ab restricted epitopes paves the way for future investigations at the polyclonal repertoire level with MHCII-tetramer reagents.

Our findings establish several molecular and cellular details of how PLP is expressed and presented for central tolerance. First, the conditional ablation of PLP in TECs unequivocally established that intrathymic expression by epithelial cells was essential, excluding a scenario whereby extrathymically derived PLP may reach the thymus as blood-borne antigen or through import by migratory DCs (38–40). Second, Aire was crucially required for central tolerance induction in TCR-PLP1 cells. This was somewhat unexpected, given that intrathymic PLP transcription, in contrast to “canonical” promiscuous gene expression, is not confined to Aire+ MHCIIhi mTECs, but occurs at comparable levels also in their Aireneg/lo MHCIIlo immature precursors as well as in cTECs (8, 41). In Aire–/– mTECs, PLP transcripts are reduced by about fivefold (41), possibly falling below a critical threshold for central tolerance induction. However, tolerogenic functions of Aire beyond the promotion of promiscuous gene expression, for instance through regulation of chemokine expression, cellular differentiation, or antigen presentation may also contribute (42–46). These considerations notwithstanding, the “late” deletion of TCR-PLP1 cells at the CD4 SP stage is consistent with PLP expression in cTECs being irrelevant. Third, endogenously expressed PLP is directly presented by TECs, indicating that there is no requirement for “antigen handover” from expressing TECs to thymic DCs (24). The latter has not only been reported for certain “neo-antigens” expressed in mTECs (47) but was also suggested to occur for physiologically expressed self-antigens (48, 49). However, ablation of DCs did not interfere with central tolerance induction in the TCR-PLP1 model, whereas conversely, reduced direct presentation by mTECs in the C2TAkd system had a significant effect. Of note, the direct presentation of TEC-derived PLP contrasts with what has been reported for an epitope of another Myelin autoantigen, MBP, whose tolerogenic display in the thymus required hematopoietic APC-mediated presentation of MBP of non-hematopoietic origin (50). Direct MHCII-restricted presentation of endogenous antigens by TECs can be facilitated through routing of intracellular material into autophagosomes (25, 51, 52), but whether this pathway is involved in central tolerance to PLP remains to be addressed.

Bypassing or eliminating the thymic checkpoint through adoptive transfer of TCR-PLP1 cells or conditional deletion of PLP in TECs, respectively, revealed that PLP epitope #1 is constitutively “visible” to specific CD4 T cells in the periphery. Intriguingly, whereas DCs were dispensable for central tolerance, the presentation of PLP in the periphery critically involved DCs, as evident from the failure of adoptively transferred TCR-PLP1 cells to proliferate in ΔDC recipients or MHCII–/– → PlpWT BM chimeras. The exact source of PLP that is presented by DCs in the periphery remains to be identified, but the lack of proliferation of adoptively transferred TCR-PLP1 cells in MHCII+/+ → PlpKO BM chimeras indicates a non-hematopoietic origin. Along these lines, it will be interesting to establish the anatomical location and exact identity of the DC subset(s) by which PLP is peripherally acquired and presented; these cells obviously lack the capacity to efficiently migrate to the thymus and induce central tolerance.

A general defect in intrathymic expression of tissue-restricted antigens, for instance in Aire- or Fezf2-deficient mice (53, 54), or the selective interference with intrathymic expression of individual genes, as is the case for the eye autoantigen IRBP (55), can precipitate spontaneous autoimmunity. By contrast, the deficiency in central tolerance to epitope #1 in PlpΔTEC mice neither resulted in spontaneous EAE nor increased the susceptibility to “induced” EAE, irrespective of whether or not these mice were TCR transgenic. This suggests a substantial degree of “functional” redundancy between mTEC-mediated central tolerance and DC-mediated peripheral tolerance to PLP. At the mechanistic level, however, our data point toward a differential contribution of central and peripheral tolerance induction to recessive versus dominant modes of tolerance, that is, clonal deletion and anergy versus Treg induction, respectively. On the one hand, there was a similar peripheral CD4 T cell reduction in TCR-PLP1 mice on both PlpWT as well as PlpΔTEC background, indicating that deletional tolerance mechanisms also operate in the periphery. Likewise, the anergic state of the Foxp3– subset of TCR-PLP1+ cells in the periphery was independent of thymic PLP expression. On the other hand, however, the “normal” formation of a PLP-specific peripheral Treg compartment appeared to depend upon thymic Treg induction by mTECs. Consistent with impaired dominant tolerance to PLP in the absence of central tolerance induction, PlpΔTEC mice exhibited a more severe EAE course than PlpWT mice when receiving adoptively transferred naïve TCR-PLP1 at the time of “active EAE immunization” with PLP9–20.

TCR-PLP1 ΔDC mice represent an informative model regarding the question to which extent the PLP-specific CD4 T cell repertoire is shaped by thymic output as opposed to peripheral encounter of self-antigen: regardless of the absence of DCs, the peripheral CD4 T cell pool in these mice essentially phenocopied that of DC-sufficient mice, arguing for a prevailing influence of intrathymic tolerance induction. However, the maintenance and/or induction of the anergic state of the Foxp3– subset of TCR-PLP1+ cells in the periphery required antigen (re-)encounter on peripheral DCs.

In sum, our work provides a comprehensive analysis of the cellular and molecular determinants that specify self-tolerance to PLP, the major myelin protein, in BL/6 mice. Our findings reveal distinct levels of redundancy or non-redundancy in terms of central versus peripheral tolerance induction and how these relate to EAE susceptibility. The definition of the I-Ab-restricted CD4 T cell epitopes of PLP in conjunction with the comprehensive analysis of the tolerance modes that apply to these epitopes will lead the way to a deeper understanding of how repertoires directed against different epitopes of the very same CNS autoantigen may cooperate during disease induction and resolution.

Materials and Methods

Mice

MHC class II–/– (H2-Ab1–/–) (56), C2TAkd (27), ΔDC (26), PlpKO (20), and Aire–/– (57) mice have been described previously. The gene encoding for PLP is located on the X chromosome. We did not observe any differences in the composition and phenotype of lymphoid compartments between TCR-PLP1 or TCR-PLP2 transgenic PLP-sufficient females (Plp+/+) and males (Plp+/y) or between PLP-deficient females (Plp–/–) or males (Plp–/y). Therefore, female and male mice were included into the PLP-sufficient or -deficient groups and their genotype indicated as PlpWT or PlpKO. PlpΔTEC mice were obtained by crossing Foxn1-Cre (58) mice to mice carrying a conditional Plp allele in which exon 3 is flanked by loxP sites (Plpfl) (59). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in individually ventilated cages. All phenotypic analyses were performed in young adult mice at 4–5 weeks of age. Animal studies and procedures were approved by local authorities (Az 7-08 and 142-13).

To generate TCR transgenic mice, we used rearranged V(D)J regions of TCRs from PLP epitope #1 or #2-specific T cell hybridomas (D9-119-2 or A43-11-5, respectively). Hybridoma D9-119-2 (TCR-PLP1) was obtained by immunizing PlpKO mice with peptide PLP1–25, repeated re-stimulation of draining LN cells with PLP9–20 and subsequent fusion with BW5147 cells. Its TCRα chain contains a rearrangement of Trav9d-3.201 (Vα3.2) and Traj34-201, the TCRβ chains harbors a Trbv19-201 (Vβ6), Trbd1, and Trbj1-1 rearrangement. Hybridoma A43-11-5 (TCR-PLP2) was obtained by immunizing PlpKO mice with peptide PLP160–184, repeated re-stimulation of draining LN cells with PLP172–183, and subsequent fusion with BW5147 cells. Its TCRα chain contains a Trav14-1-201 (Vα2) and Traj23-201 rearrangement, the TCRβ chain harbors a Trbv31-01 (Vβ14), Trbd1, and Trbj1-1 rearrangement. TCRα and TCRβ rearrangements from the D9-119-2 and A43-11-5 hybridomas were PCR amplified and cloned into the cassette vectors pTαcass and pTβcass as described before (60). Transgenic mice were generated by injection of linearized DNA into pronuclei of C57BL/6 zygotes.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to Vα3.2 (RR3-16); PE-conjugated mAbs to Vβ6 (RR4-7), Vα2 (B20.1), and Vβ14 (14-2); CyChrome-conjugated mAbs to CD8 (53-6.7), PE-Cy7-conjugated streptavidin and mAbs to CD25 (PC61) and FR4 (12A5); APC-Cy7-conjugated mAbs to CD4 (GK1.5); biotin-conjugated mAbs to CD8 (53-6.7), CD4 (GK 1.5), B220 (RA3-6B2) and Vα2 (B20.1); APC-conjugated mAbs to Foxp3 (FJK-16s), CD45.2 (104); Pacific Blue-conjugated mAbs to CD45.1 (A20) were from BioLegend or eBiosciences, respectively; flow cytometric analyses were performed on a FACSCanto II (BD) using FACSDiva (BD) and FlowJo (Tree Star) software.

Peptides and Antigens

Purified human PLP (100% identical to mouse PLP) was prepared as described (7). 25-mer peptides were synthesized in the central core facility of the DKFZ (8). 12-mer peptides were synthesized in the central core facility of the DKFZ or purchased from BioTrend.

Epitope Prediction and In Silico Analysis

The IEDB tool (http://www.iedb.org/) combines various machine learning algorithms for peptide epitope prediction in the context of a given MHC haplotype. The full-length PLP amino acid sequence was analyzed using the IEDB tool in the default “consensus” setting for prediction methods (21, 22). A lower score indicates better binding to MHCII. The theoretical IC50 values were obtained with the SMM-align predictor (23).

Immunization and T Cell Proliferation Assays

Mice were immunized with 100 µg purified PLP or 50 µg peptide emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (volume/volume, 1/1). After 9 days, popliteal and inguinal lymph node cells were harvested and cultured for 72 h in triplicate at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells/well in round-bottomed, 96-well plates in serum-free medium (HL-1; BioWhittaker) in the presence or absence of titrated amounts of peptide or 5 µg/ml of the respective peptide for epitope mapping. Proliferation was measured by incorporation of 3H-thymidine, added for the last 24 h of culture at a concentration of 1 μCi/well. Only mice with comparable control responses to the complete Freund’s adjuvant component PPD were included in the analyses. Proliferation indices were calculated as 3H-Thymidin-incorporation in the presence of specific peptide divided by background proliferation w/o peptide. For direct ex vivo proliferation assays, 4 × 105 T cells and 3 × 104 irradiated (3,000 rad) BM-derived DCs were cultured in the presence of increasing peptide concentrations.

BM Chimeras

Bone marrow was depleted of B and T cells using biotinylated mAbs to B220, CD8, and CD4 and streptavidin MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotech). Female recipient mice were irradiated with 2 × 550 rad and reconstituted with 5 × 106 BM cells.

Adoptive T Cell Transfer

TCR-PLP1 or TCR-PLP2 CD4+ T cells were isolated from pooled lymph nodes and spleen by cell sorting or by depletion of CD25+ cells with biotin-conjugated anti-CD25 and anti-SAV MicroBeads followed by positive enrichment with anti-CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). T cells were labeled with CFSE (Life Technologies) and 5 × 106 T cells were injected i.v. into the lateral tail vein of congenic recipient mice. After 4 days, spleen or lymph node cells of recipient mice were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Th1 and Th17 Polarization

Naive CD4+ T cells were prepared from TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice using the mouse CD4 T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech). For Th1 polarization, cells were incubated for 5 days in anti CD3 (2C11) (5 µg/ml) coated 12-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) in the presence of recombinant IL-2 (5 ng/ml), recombinant IL-12 (10 ng/ml), anti-CD28 mAb (37.51) (3 µg/ml), and anti-IL-4 mAb (11B11) (10 µg/ml). For Th17 polarization, cells were stimulated in the presence of IL-6 (50 ng/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), TGF-β1 (1 ng/ml), anti-CD28 (5 µg/ml), anti-IL-4 (10 µg/ml), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2) (10 µg/ml), and anti-IL-2 (JES6-1A2) (10 µg/ml). To verify successful polarization, cells were re-stimulated on day 5 with PMA and ionomycin for 5 h and stained intracellularly for expression of lineage-specific effector cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-17).

In Vito Suppression Assay

TCR-PLP1+CD25+ cells were sorted from TCR-PLP1 PlpWT mice (CD45.2) and co-cultured at different ratios with 2 × 104 CFSE-labeled TCR-PLP1+CD25– responder cells (CD45.1) from TCR-PLP1 PlpKO mice in the presence of 2 × 105 irradiated spleen APCs and 5 µg/ml peptide PLP9–20. After 4 days, CFSE dilution in gated CD45.1+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

For “active EAE” induction, mice were immunized subcutaneously at three sites on the flanks with 200 µg peptide PLP9–20, PLP172–183, or PLP238–249 in a total of 200 µl PBS/CFA emulsion (1:1). Pertussis toxin (400 ng) was given on days 0 and 2. In some experiments, mice received 5 × 106 naïve TCR-PLP1 cells 6 h prior to the immunization. Signs of EAE were scored as follows: 0, none; 0.5, partial loss of tail tonus; 1, limp tail; 1.5, wobbly gait and limb tail; 2.5, paralysis of one hind leg; 3, hind-limb paralysis on both sides; 3.5, hind-limb and partial front limbparalysis; 4, complete hind-limb and forelimb paralysis; 5, moribund. Disease incidence and scores were measured daily. For “passive EAE” induction with Th1 or Th17 cells, Rag1–/– PlpWT recipients were injected i.v. with 5 × 106 in vitro polarized TCR-PLP1 cells. Scoring was carried out as described above.

Preparation of Thymic Stromal Cells and Quantitative PCR

Thymic stromal cells were isolated as described (61). TEC subtypes were classified according to the following surface phenotypes: cTECs, CD45−EpCAM+Ly51+CD80−; mTEChi, CD45−EpCAM+Ly51−CD80hiMHCIIhi; mTEClo, and CD45−EpCAM+Ly51−CD80loMHCIIlo. RNA was isolated from sorted cells using the miRNAeasy kit including a DNase digest (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). PCR reactions were performed in duplicates on a CFX96 real-time thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) using the Ssofast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Fluorescence was recorded at the annealing step and relative expression levels were calculated with the comparative Ct method, using HPRT as housekeeping gene for normalization. Primers: Plp-forward, GGGCTTGTTAGAGTGTTGTGC; Plp-reverse, GAAGAAGAAAGAGGCAGTTCCA; Hprt-forward, TGAAGAGCTACTGTAATGATCAGTCAAC; Hprt-reverse, AGCAAGCTTGCAACCTTACCA.

Statistical Analysis

Unless indicated otherwise, statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction for unequal variances.

Ethics Statement

Animal studies and procedures were approved by local authorities (Az 7-08, 142-13, 88-17).

Author Contributions

MH and LK designed experimental strategies. LK and BK mapped PLP epitopes. JW and MH generated and analyzed TCR-PLP1 mice. LW, MH, and CF generated and analyzed TCR-PLP2 mice. GJ performed mRNA expression analyses. K-AN and HW provided PlpKO and Plpfloxed mice. LK and MH wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

LW, JW, MH, and LK were supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (SFB1054, project part A01 and IRTG). LW received a PhD-fellowship from the China Scholarship Council (CSC). BK was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2012-AdG).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01511/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1.Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC, Waldner H, Munder M, Bettelli E, Nicholson LB. T cell response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): role of self and cross-reactive antigens in shaping, tuning, and regulating the autopathogenic T cell repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol (2002) 20:101–23. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081701.141316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(6):393–407. 10.1038/nri2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol (2016) 36(2):115–27. 10.1055/s-0036-1579739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zamvil SS, Mitchell DJ, Moore AC, Kitamura K, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. T-cell epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein that induces encephalomyelitis. Nature (1986) 324(6094):258–60. 10.1038/324258a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wekerle H, Kojima K, Lannes-Vieira J, Lassmann H, Linington C. Animal models. Ann Neurol (1994) 36(Suppl):S47–53. 10.1002/ana.410360714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritz RB, Zhao ML. Active and passive experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in strain 129/J (H-2b) mice. J Neurosci Res (1996) 45(4):471–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuohy VK, Sobel RA, Lees MB. Myelin proteolipid protein-induced experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Variations of disease expression in different strains of mice. J Immunol (1988) 140(6):1868–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein L, Klugmann M, Nave KA, Tuohy VK, Kyewski B. Shaping of the autoreactive T-cell repertoire by a splice variant of self protein expressed in thymic epithelial cells. Nat Med (2000) 6(1):56–61. 10.1038/71540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teuscher C, Bunn JY, Fillmore PD, Butterfield RJ, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP. Gender, age, and season at immunization uniquely influence the genetic control of susceptibility to histopathological lesions and clinical signs of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: implications for the genetics of multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol (2004) 165(5):1593–602. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63416-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blankenhorn EP, Butterfield R, Case LK, Wall EH, del Rio R, Diehl SA, et al. Genetics of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis supports the role of T helper cells in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Ann Neurol (2011) 70(6):887–96. 10.1002/ana.22642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gourraud PA, Harbo HF, Hauser SL, Baranzini SE. The genetics of multiple sclerosis: an up-to-date review. Immunol Rev (2012) 248(1):87–103. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01134.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Markovic-Plese S, Lacet B, Raus J, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Increased frequency of interleukin 2-responsive T cells specific for myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med (1994) 179(3):973–84. 10.1084/jem.179.3.973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markovic-Plese S, Fukaura H, Zhang J, Al-Sabbagh A, Southwood S, Sette A, et al. T cell recognition of immunodominant and cryptic proteolipid protein epitopes in humans. J Immunol (1995) 155(2):982–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wekerle H, Bradl M, Linington C, Kaab G, Kojima K. The shaping of the brain-specific T lymphocyte repertoire in the thymus. Immunol Rev (1996) 149:231–43. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1996.tb00907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delarasse C, Daubas P, Mars LT, Vizler C, Litzenburger T, Iglesias A, et al. Myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-deficient (MOG-deficient) mice reveal lack of immune tolerance to MOG in wild-type mice. J Clin Invest (2003) 112(4):544–53. 10.1172/JCI15861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Targoni OS, Lehmann PV. Endogenous myelin basic protein inactivates the high avidity T cell repertoire. J Exp Med (1998) 187(12):2055–63. 10.1084/jem.187.12.2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshizawa I, Bronson R, Dorf ME, Abromson-Leeman S. T-cell responses to myelin basic protein in normal and MBP-deficient mice. J Neuroimmunol (1998) 84(2):131–8. 10.1016/S0165-5728(97)00205-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voskuhl RR. Myelin protein expression in lymphoid tissues: implications for peripheral tolerance. Immunol Rev (1998) 164:81–92. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derbinski J, Schulte A, Kyewski B, Klein L. Promiscuous gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells mirrors the peripheral self. Nat Immunol (2001) 2(11):1032–9. 10.1038/ni723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klugmann M, Schwab MH, Puhlhofer A, Schneider A, Zimmermann F, Griffiths IR, et al. Assembly of CNS myelin in the absence of proteolipid protein. Neuron (1997) 18(1):59–70. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)80046-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, Sidney J, Dow C, Mothe B, Sette A, Peters B. A systematic assessment of MHC class II peptide binding predictions and evaluation of a consensus approach. PLoS Comput Biol (2008) 4(4):e1000048. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Sidney J, Kim Y, Sette A, Lund O, Nielsen M, et al. Peptide binding predictions for HLA DR, DP and DQ molecules. BMC Bioinformatics (2010) 11:568. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O. Prediction of MHC class II binding affinity using SMM-align, a novel stabilization matrix alignment method. BMC Bioinformatics (2007) 8:238. 10.1186/1471-2105-8-238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein L, Hinterberger M, von Rohrscheidt J, Aichinger M. Autonomous versus dendritic cell-dependent contributions of medullary thymic epithelial cells to central tolerance. Trends Immunol (2011) 32(5):188–93. 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nedjic J, Aichinger M, Mizushima N, Klein L. Macroautophagy, endogenous MHC II loading and T cell selection: the benefits of breaking the rules. Curr Opin Immunol (2009) 21(1):92–7. 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohnmacht C, Pullner A, King SB, Drexler I, Meier S, Brocker T, et al. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. J Exp Med (2009) 206(3):549–59. 10.1084/jem.20082394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinterberger M, Aichinger M, Prazeres da Costa O, Voehringer D, Hoffmann R, Klein L. Autonomous role of medullary thymic epithelial cells in central CD4(+) T cell tolerance. Nat Immunol (2010) 11(6):512–9. 10.1038/ni.1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tompkins SM, Padilla J, Dal Canto MC, Ting JP, Van Kaer L, Miller SD. De novo central nervous system processing of myelin antigen is required for the initiation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (2002) 168(8):4173–83. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuerten S, Lichtenegger FS, Faas S, Angelov DN, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. MBP-PLP fusion protein-induced EAE in C57BL/6 mice. J Neuroimmunol (2006) 177(1–2):99–111. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson AC, Nicholson LB, Legge KL, Turchin V, Zaghouani H, Kuchroo VK. High frequency of autoreactive myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cells in the periphery of naive mice: mechanisms of selection of the self-reactive repertoire. J Exp Med (2000) 191(5):761–70. 10.1084/jem.191.5.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stadinski BD, Zhang L, Crawford F, Marrack P, Eisenbarth GS, Kappler JW. Diabetogenic T cells recognize insulin bound to IAg7 in an unexpected, weakly binding register. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2010) 107(24):10978–83. 10.1073/pnas.1006545107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohan JF, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Register shifting of an insulin peptide-MHC complex allows diabetogenic T cells to escape thymic deletion. J Exp Med (2011) 208(12):2375–83. 10.1084/jem.20111502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington CJ, Paez A, Hunkapiller T, Mannikko V, Brabb T, Ahearn M, et al. Differential tolerance is induced in T cells recognizing distinct epitopes of myelin basic protein. Immunity (1998) 8(5):571–80. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80562-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lafaille JJ, Nagashima K, Katsuki M, Tonegawa S. High incidence of spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in immunodeficient anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic mice. Cell (1994) 78(3):399–408. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90419-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olivares-Villagomez D, Wang Y, Lafaille JJ. Regulatory CD4(+) T cells expressing endogenous T cell receptor chains protect myelin basic protein-specific transgenic mice from spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med (1998) 188(10):1883–94. 10.1084/jem.188.10.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van de Keere F, Tonegawa S. CD4(+) T cells prevent spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic mice. J Exp Med (1998) 188(10):1875–82. 10.1084/jem.188.10.1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hori S, Haury M, Coutinho A, Demengeot J. Specificity requirements for selection and effector functions of CD25+4+ regulatory T cells in anti-myelin basic protein T cell receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99(12):8213–8. 10.1073/pnas.122224799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonasio R, Scimone ML, Schaerli P, Grabie N, Lichtman AH, von Andrian UH.Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat Immunol (2006) 7(10):1092–100. 10.1038/ni1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atibalentja DF, Byersdorfer CA, Unanue ER. Thymus-blood protein interactions are highly effective in negative selection and regulatory T cell induction. J Immunol (2009) 183(12):7909–18. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadeiba H, Lahl K, Edalati A, Oderup C, Habtezion A, Pachynski R, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells transport peripheral antigens to the thymus to promote central tolerance. Immunity (2012) 36(3):438–50. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sansom SN, Shikama-Dorn N, Zhanybekova S, Nusspaumer G, Macaulay IC, Deadman ME, et al. Population and single-cell genomics reveal the Aire dependency, relief from Polycomb silencing, and distribution of self-antigen expression in thymic epithelia. Genome Res (2014) 24(12):1918–31. 10.1101/gr.171645.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Benoist C, Mathis D. The cellular mechanism of Aire control of T cell tolerance. Immunity (2005) 23(2):227–39. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yano M, Kuroda N, Han H, Meguro-Horike M, Nishikawa Y, Kiyonari H, et al. Aire controls the differentiation program of thymic epithelial cells in the medulla for the establishment of self-tolerance. J Exp Med (2008) 205(12):2827–38. 10.1084/jem.20080046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laan M, Kisand K, Kont V, Moll K, Tserel L, Scott HS, et al. Autoimmune regulator deficiency results in decreased expression of CCR4 and CCR7 ligands and in delayed migration of CD4+ thymocytes. J Immunol (2009) 183(12):7682–91. 10.4049/jimmunol.0804133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishikawa Y, Hirota F, Yano M, Kitajima H, Miyazaki J, Kawamoto H, et al. Biphasic Aire expression in early embryos and in medullary thymic epithelial cells before end-stage terminal differentiation. J Exp Med (2010) 207(5):963–71. 10.1084/jem.20092144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lei Y, Ripen AM, Ishimaru N, Ohigashi I, Nagasawa T, Jeker LT, et al. Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. J Exp Med (2011) 208(2):383–94. 10.1084/jem.20102327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J Exp Med (2004) 200(8):1039–49. 10.1084/jem.20041457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koble C, Kyewski B. The thymic medulla: a unique microenvironment for intercellular self-antigen transfer. J Exp Med (2009) 206(7):1505–13. 10.1084/jem.20082449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taniguchi RT, DeVoss JJ, Moon JJ, Sidney J, Sette A, Jenkins MK, et al. Detection of an autoreactive T-cell population within the polyclonal repertoire that undergoes distinct autoimmune regulator (Aire)-mediated selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(20):7847–52. 10.1073/pnas.1120607109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huseby ES, Sather B, Huseby PG, Goverman J. Age-dependent T cell tolerance and autoimmunity to myelin basic protein. Immunity (2001) 14(4):471–81. 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00127-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nedjic J, Aichinger M, Emmerich J, Mizushima N, Klein L. Autophagy in thymic epithelium shapes the T-cell repertoire and is essential for tolerance. Nature (2008) 455(7211):396–400. 10.1038/nature07208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aichinger M, Wu C, Nedjic J, Klein L. Macroautophagy substrates are loaded onto MHC class II of medullary thymic epithelial cells for central tolerance. J Exp Med (2013) 210(2):287–300. 10.1084/jem.20122149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, Chen Z, Berzins SP, Turley SJ, et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science (2002) 298(5597):1395–401. 10.1126/science.1075958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takaba H, Morishita Y, Tomofuji Y, Danks L, Nitta T, Komatsu N, et al. Fezf2 orchestrates a thymic program of self-antigen expression for immune tolerance. Cell (2015) 163(4):975–87. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeVoss J, Hou Y, Johannes K, Lu W, Liou GI, Rinn J, et al. Spontaneous autoimmunity prevented by thymic expression of a single self-antigen. J Exp Med (2006) 203(12):2727–35. 10.1084/jem.20061864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cosgrove D, Gray D, Dierich A, Kaufman J, Lemeur M, Benoist C, et al. Mice lacking MHC class II molecules. Cell (1991) 66(5):1051–66. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90448-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramsey C, Winqvist O, Puhakka L, Halonen M, Moro A, Kampe O, et al. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune response. Hum Mol Genet (2002) 11(4):397–409. 10.1093/hmg/11.4.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rossi SW, Jeker LT, Ueno T, Kuse S, Keller MP, Zuklys S, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) enhances postnatal T-cell development via enhancements in proliferation and function of thymic epithelial cells. Blood (2007) 109(9):3803–11. 10.1182/blood-2006-10-049767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luders KA, Patzig J, Simons M, Nave KA, Werner HB. Genetic dissection of oligodendroglial and neuronal Plp1 function in a novel mouse model of spastic paraplegia type 2. Glia (2017) 65(11):1762–76. 10.1002/glia.23193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kouskoff V, Signorelli K, Benoist C, Mathis D. Cassette vectors directing expression of T cell receptor genes in transgenic mice. J Immunol Methods (1995) 180(2):273–80. 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00002-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.von Rohrscheidt J, Petrozziello E, Nedjic J, Federle C, Krzyzak L, Ploegh HL, et al. Thymic CD4 T cell selection requires attenuation of March8-mediated MHCII turnover in cortical epithelial cells through CD83. J Exp Med (2016) 213(9):1685–94. 10.1084/jem.20160316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.