Abstract

Background

Managed entry agreements (MEAs) are a set of instruments to facilitate access to new medicines. This study surveyed the implementation of MEAs in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) where limited comparative information is currently available.

Method

We conducted a survey on the implementation of MEAs in CEE between January and March 2017.

Results

Sixteen countries participated in this study. Across five countries with available data on the number of different MEA instruments implemented, the most common MEAs implemented were confidential discounts (n = 495, 73%), followed by paybacks (n = 92, 14%), price-volume agreements (n = 37, 5%), free doses (n = 25, 4%), bundle and other agreements (n = 19, 3%), and payment by result (n = 10, >1%). Across seven countries with data on MEAs by therapeutic group, the highest number of brand names associated with one or more MEA instruments belonged to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC)-L group, antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (n = 201, 31%). The second most frequent therapeutic group for MEA implementation was ATC-A, alimentary tract and metabolism (n = 87, 13%), followed by medicines for neurological conditions (n = 83, 13%).

Conclusions

Experience in implementing MEAs varied substantially across the region and there is considerable scope for greater transparency, sharing experiences and mutual learning. European citizens, authorities and industry should ask themselves whether, within publicly funded health systems, confidential discounts can still be tolerated, particularly when it is not clear which country and party they are really benefiting. Furthermore, if MEAs are to improve access, countries should establish clear objectives for their implementation and a monitoring framework to measure their performance, as well as the burden of implementation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40273-017-0559-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Budget impact was the main concern behind implementation of managed entry agreements (MEAs) among Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, and most agreements implemented were financial ones. |

| A high number of MEAs were implemented for oncology and diabetes medicines. |

| European citizens, authorities and industry should ask themselves whether, within publicly funded health systems, confidential discounts can still be tolerated. |

Introduction

Managed entry agreements (MEAs) are a set of instruments to facilitate access to new medicines, which are now relatively well-established in a number of OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. Their use has increased over time [1] in response to high prices for new medicines, particularly those for cancer and orphan diseases [2, 3]; the need for payers to work within finite budget limits; uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of new medicines in routine clinical care (real-life); and the willingness to address unmet need. Different names are used to define MEAs as a group in different countries, and there are different types of MEAs. Despite their diversity, all these agreements have a common objective—to facilitate access to new medicines in a context of uncertainty (around effectiveness and/or use in real-life) and high prices [1]. The different names used in different countries relate to the objectives they are trying to achieve (e.g. patient access schemes in the UK), the nature of the agreements (e.g. conventions in Belgium), and the type of agreement (e.g. special pricing arrangements in Australia) for example.

A variety of MEAs have been implemented worldwide. Authors have tried to classify them in different ways, notably dividing them into financial and health outcome-based agreements [4, 5]. The latter are also called performance-based agreements, although one could argue that most of the financial agreements (apart from simple discounts, for example) have a performance component (e.g. payback for overspending, or coverage of a defined number of doses after which the manufacturer takes over the cost). Financial agreements include discounts, price-volume agreements, payback agreement, free doses or dose-capping schemes [4, 5]. Health outcome-based agreements include different types of performance agreements whereby reimbursement is linked to the performance of the medicine in real-life or evidence development [4–6]. These MEAs have also been called performance-based risk-sharing arrangements (PBRSAs) [7, 8].

There is now a solid body of literature on the use, advantages and disadvantages of MEAs as implemented in Western Europe, North America and Australia [1, 4–15, 17]; however, less information is available on their impact [18–22]. Evidence on the use of MEAs in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where these agreements are increasingly being implemented, is much more limited [23-25]. This is a concern as resources are more constrained in these countries, as seen, for example, by limited utilisation of biological medicines for rheumatoid arthritis and bowel diseases compared with Western European countries [26, 27]. Consequently, there is a need to address this information gap to provide future direction.

To address this, we surveyed the implementation of MEAs in CEE among senior payers, their advisers and other senior stakeholders in these countries. In particular, we investigated the rationale for introducing MEAs in these countries, the types of agreement implemented, their therapeutic focus, what happens once these agreements come to an end, and other approaches to better manage the entry of new medicines. In addition, we reviewed what countries define as ‘risk’, ‘risk sharing’ and ‘high prices’. The findings were used to highlight challenges and suggest potential ways forward to improve access to new medicines in the CEE region and beyond.

Methods

We conducted a survey on the implementation of risk sharing and MEAs in CEE1 between January and March 2017. We developed a questionnaire (see electronic supplementary material) that we sent to key informants in the region. Key informants are co-authors (DA, TB, TC, DD, MD, JF, KG, IGK, IH, AJ, EL, OL, IM, VM-P, DM, TN, GP, MP, DT, LV) of this study and included senior staff in competent authorities for pricing and reimbursement, academics with expertise on national pharmaceutical issues and other national experts in pharmaceutical matters (e.g. head of country International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research [ISPOR] chapters). Most key informants were identified through the Piperska group [25, 28, 29]—a multidisciplinary network of professionals with interest in the quality use of medicines—either through its membership or extended network.

The information collected was of both a qualitative and quantitative nature. Qualitative questions included whether MEAs are implemented, the rationale for implementing them and what happens when an agreement comes to an end. Quantitative information focused on the number of agreements implemented, by type and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) group. The information provided by the key informants in each country was based on their knowledge of the national context, including where to find information on MEAs available online (which may not be simple to find due to language barriers, familiarity with the national authority’s websites), access to non-published information and a review of legislation relevant to MEAs. An intensive data-cleaning process was subsequently undertaken to harmonise the taxonomy used to classify MEAs in different countries. This was done in collaboration with the country experts to ensure the correct classification of the agreements according to a common taxonomy. The taxonomy used was based on previous literature [4, 5], with minor adaptation to reflect the nature of some agreements that would not have necessarily fitted into previously proposed taxonomies.

Definition of Managed Entry Agreements (MEAs) Used in this Study

In this study, we define MEAs as agreements made between payers and pharmaceutical companies to manage the impact of uncertainty around cost effectiveness and volume, and the impact of high prices on access [15, 16]. Uncertainties around the value of new medicines, high prices and the level of uptake of the new medicine can all influence budget impact and cost effectiveness, and are therefore key variables informing reimbursement decision [1].

Counting MEAs

There are different options for enumerating MEAs. For example, one can count:

The number of international non-proprietary names (INNs) associated with one or more MEA instruments.

The number of different trade names associated with one or more MEA instruments. This should, in principle, be similar to option 1, apart from different formulations of the same INN and ATC-5 group with different trade names, e.g. Xeplion (1-month injection) and Trevicta (3-monthly injection), same INN (paliperidone) and ATC-5 group (N05AX13), both marketed by Janssen-Cilag, which are counted separately under option 2.

The number of different medicine indications associated with one or more MEA instruments (one INN may have different MEAs for different indications).

The number of different MEA instruments implemented (e.g. one INN/trade name may be associated with different types of MEAs, such as a discount and a payback, and these are counted separately under option 4).

The number of different agreements signed.

In this study, we enumerated the types of MEAs implemented based on the number of different MEA instruments implemented (option 4), and the number of MEAs implemented in different therapeutic areas based on the number of different trade names associated with one or more MEA instruments (option 2). The choice of enumeration method was determined by data availability. Only these two options were available across all countries that submitted data on the number of agreements implemented, either by type, therapeutic group or both. We consequently used this approach.

Results

Sixteen CEE countries participated in this study by providing qualitative (16 countries) and quantitative information on the types and numbers of MEAs implemented (provided by eight countries; in four countries the number of MEAs and the medicines involved are confidential or was incomplete, three did not implement MEAs, and one country was currently discussing the legislation, which would enable their introduction at the time the survey was conducted).

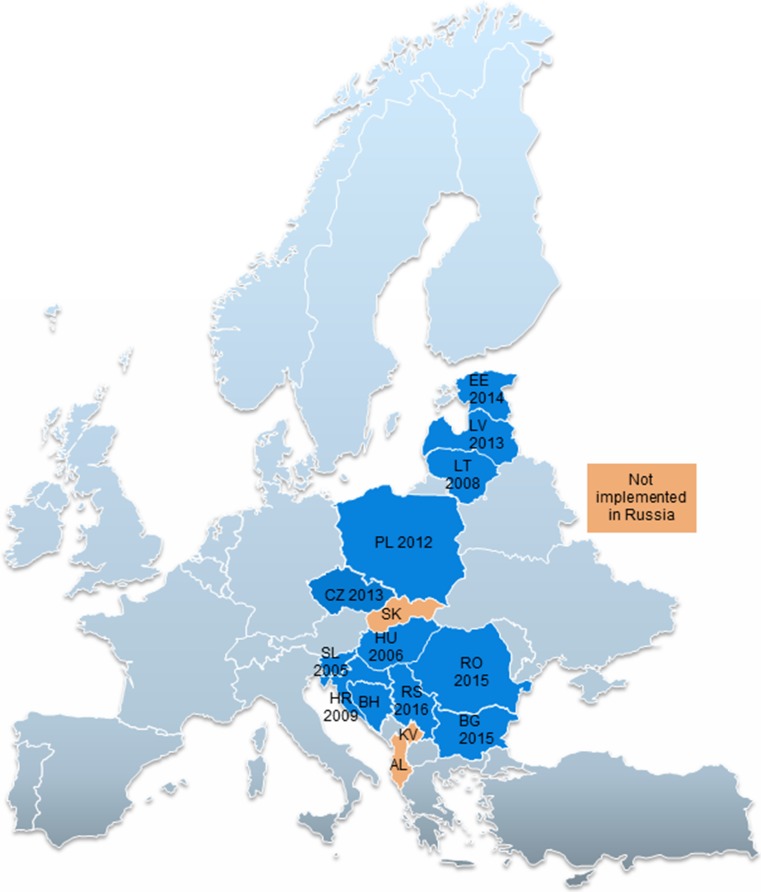

Use of MEAs

Most countries included in this study (n = 12) implemented MEAs as defined in this study (Fig. 1). Three countries, Albania, Kosovo and Russia, did not implement any MEAs. One country, Slovakia, is currently discussing the relevant legislation for implementing MEAs but, as of February 2017, no official MEAs were in place. The aim of the Ministry of Health in Slovakia is to increase access to innovative medicines by introducing changes in the pricing and reimbursement legislation, which would make it more flexible. Some of the proposals currently being discussed include the introduction of risk-sharing agreements, the negotiation of confidential price agreements (whose use is currently limited), higher willingness-to-pay thresholds, and additional criteria for including new medicines in the reimbursement list, including adopting a more societal perspective in health technology assessment.

Fig. 1.

Implementation of MEAs in Central and Eastern Europe as of February 2017. Countries coloured in blue implement MEAs. The years refer to the year the first MEA was introduced in a particular country. In some countries, for example Serbia, the legislation was introduced well before (2014) the first MEA was signed (2016). Countries coloured in orange did not implement MEAs as of February 2017, and countries coloured in grey were either not part of the study or we did not have any information on them. AL Albania, BG Bulgaria, BH Bosnia and Herzegovina, CZ Czech Republic, EE Estonia, LT Lithuania, LV Latvia, HR Croatia, HU Hungary, KV Kosovo, PL Poland, RO Romania, RS Serbia, SL Slovenia, SK Slovakia, MEAs managed entry agreements

Rationale for Introducing MEAs

Countries cited different reasons for implementing MEAs. These can be summarised in three main groups: working within finite resources (n = 10), enabling access (n = 6) and dealing with uncertainty around cost effectiveness and use in real-life (n = 6) (Table 1). In most countries, MEAs are enshrined in the legislation. Exceptions include Estonia, where MEAs can be made as a result of price negotiations with the manufacturer, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where, although not formally identified as MEAs, special financial agreements with manufacturers of on-patent medicines can be made to accelerate access for limited number of patients or specific patient groups.

Table 1.

Rationale for implementing MEAs and policy basis in Central and Eastern European countries

| Rationale | Policy basis | |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | Not implemented | NA |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Facilitating access to new medicines by reducing their price and budget impact Republika Srpska Facilitating access to new medicines while working within finite budgets |

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

There are special conditions for the financing of new patented medicines. These fit under the MEA definition used in this study but are not officially recognised as MEAs Republika Srpska (1) Decision of the Health Insurance Fund on the criteria for inclusion of medicines in the list of reimbursed medicines (2) Decision on the criteria for inclusion of medicines in the ‘List of cytotoxic, biological and related medicines’ in order to increase access and control expenses (3) For the entry of expensive medicines, the ‘List of medicines with the specific mode of acquisition’ |

| Bulgaria | Limiting expenditure on medicines by reducing the price of medicines reimbursed by the National Health Insurance Fund (since 2015). Addressing uncertainties around the cost effectiveness and value of the newly included INN (since 2016, in force 2017) | Law on Health Insurance Art. 45, paragraphs 10 and 19 |

| Croatia | Increasing access and controlling expenditure | Bylaw of the Croatian Health Insurance Fund reimbursement of medicines rules (criteria for inclusion of medicines in the basic and supplementary list) [49] |

| Czech Republic | Increasing access to new therapies while containing expenditure | Law 48/1997 on statutory health insurance, as amended notably in 2011. It does not contain specific provisions on MEAs, but recognises that sustainability of health care financing is an integral part of public interest in health care The same law introduces provisions on coverage with evidence development for ‘highly innovative medicinal products’ (‘VILPs) |

| Estonia | Various, examples include uncertainty about the cost effectiveness of the medicine in Estonia | No formal policy framework for MEAs, they are the result of price negotiations with the manufacturer |

| Hungary | (1) Mitigation of budget impact (2) Uncertainty about clinical value (3) Confidential way to manage price |

Law 198/2006, 26.§ |

| Kosovo | Not implemented | NA |

| Latvia | To mitigate the impact of high prices, uncertainties around cost effectiveness, and added value | MEAs are intended in Regulation No. 899 of the Cabinet of Ministers on Procedures for the reimbursement of expenditures for the acquisition of medicinal products and medicinal devices intended for outpatient medical treatment |

| Lithuania | High prices, balancing National Health Insurance Fund budget, patients‘ access to treatment, possibility to prove clinical and cost effectiveness, and addressing unmet medical need | Mandatory (legal act, Ministry of Health) for all new medicines that will increase budget impact in respect of current standard of care |

| Poland | (1) Enabling the introduction of new and costly medicines into the reimbursement system in a better-controlled way (2) Increasing and improving patients’ access to medicines and other products (3) Enhancing financial sustainability of the reimbursement system (4) Increasing flexibility of shaping the pricing and reimbursement policy |

Act of 12 May 2011 on reimbursement of medicines, food products for special dietary use and medical devices |

| Romania | Financial sustainability and cost predictability | Emergency Government Ordinance no. 69/2014 (‘Cost-volume/cost-volume-results contracts represent mechanisms that ensure financial sustainability and cost predictability in healthcare’) and Ministry of Health and National Health Insurance House Common Order no. 3/1/2015 |

| Russia | Not implemented | The implementation of MEAs is not possible due to Federal Law #44. According to this law, all public purchases shall be performed on the basis of tenders and the winner shall be determined based on the lowest price. Theoretically, the situation is different in private hospitals but they consider risk-sharing schemes too sophisticated compared with their routine needs. There were a number of announcements about implementation of ‘risk-sharing’ in the Moscow region in 2017–2019 (not clear whether it should be public or private hospitals). The key idea was to just pay for recovered patients with hepatitis C. The latest information as of January 2017 was that the region was looking for funding to implement such a programme |

| Serbia | To facilitate/enable inclusion of new medicines in the reimbursement list | Rule book on criteria for inclusion and exclusion medicines on the positive list |

| Slovakia | The possibility of introducing MEAs is currently being discussed as an instrument, together with other changes in the reimbursement legislation, to improve access to new medicines | |

| Slovenia | To address issues, high prices and low/uncertain cost effectiveness | Health insurance law |

Bosnia and Herzegovina is comprised of two constitutional and legal entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Srpska. Financing, management, organisation and provision of health care are the responsibilities of each entity

MEAs managed entry agreements, NA not applicable, INN international non-proprietary name, VILPs vysoce inovativní léčivý přípravek

Types of MEAs Implemented

All countries with MEAs in place (n = 12) implemented different types of financial agreements. Eight countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania) allowed for the implementation of health outcome-based MEAs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of MEAs implemented in Central and Eastern European countries

| Financial | Health outcome-based agreements | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discounts | Price-volume agreements | Free doses | Payback | Bundle agreements and other agreements | Payment by result | Coverage with evidence development | |

| Albania | Not implemented | ||||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina (applies to both The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska) | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Bulgaria | √ | √ | √ | √b | √ | ||

| Croatia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √d | √ | |

| Czech Republic | √ | √ | √ | √ | a | ||

| Estonia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Hungary | √ | c | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Kosovo | |||||||

| Latvia | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Lithuania | √ | √ | |||||

| Poland | √ | √ | √ | √e | √ | ||

| Romania | √ | √ | |||||

| Russia | Not implemented | ||||||

| Serbia | √ | √ | √f | ||||

| Slovakia | Not yet implemented | ||||||

| Slovenia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

Ticks (√) mean that the particular type of agreement is implemented in the country, with the exception of Croatia, Poland and the Czech Republic where, since the type and number of agreements implemented is confidential, it represents possible agreements according to the legislation or reported agreements based on information from key informants. Not all may be necessarily implemented

MEAs managed entry agreements

aCoverage with evidence development is implemented in the Czech Republic, however these do not fit the definition of MEAs used in this study as there is no agreement with industry. Information on coverage with evidence development is publicly available in the Czech Republic

bIn Bulgaria, bundle agreements were classified as those agreements covering, for example, the companion diagnostic of a medicine with MEA

cIn Hungary, relevant legislation uses the term ‘price-volume agreement’ (PVA) for managed entry agreements in general. However PVA’s in the strict sense are not used in Hungary

dIn Croatia, bundle agreements included agreements for different products of the same manufacturer and also agreements across a particular therapeutic area involving different manufacturers

eOther types in Poland include setting other conditions of reimbursement, which enhance availability of health services guaranteed by the compulsory health care insurance or diminish costs of these services

fAllowed by the legislation but not yet implemented in Serbia as of February 2017

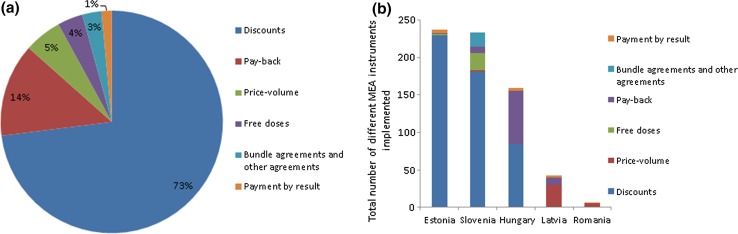

Across the five countries with available data on the number of different MEA instruments implemented by type (Slovenia, Hungary, Latvia, Estonia and Romania), the most common MEAs implemented were confidential discounts (n = 495, 73%), followed by payback (n = 92, 14%), price-volume agreements (n = 37, 5%), free doses (n = 25, 4%), bundle and other agreements (n = 19, 3%), and payment by result (n = 10, 1%) (Fig. 2a). Although the implementation of health outcome-based agreements is allowed in Estonia, Hungary, Latvia and Romania, most of the agreements implemented were financial (n = 668, 99% financial vs. n = 10, >1% health outcome-based agreements). While no data on the actual number of different MEA instruments implemented were available in the other countries, survey respondents reported that most agreements in Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (including both The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Republic of Srpska) were known to be financial ones. No country with available data on the type of MEAs implemented reported implementing coverage with evidence development. In the Czech Republic, a large number of innovative high-cost medicines have a special status of ‘highly innovative medicinal products’ (vysoce inovativní léčivý přípravek [VILP]) and, as such, are subject to coverage with evidence development. They can be reimbursed for a maximum of 3 years, although exceptional cases with temporary reimbursement beyond 3 years are also known. Manufacturers are required to set up monitoring systems, submit cost-effectiveness analysis, limit budget impact and pay for treatment of existing patients after the end of temporary reimbursement. As of March 2017, there were 19 VILPs (corresponding to six trade names) with temporary reimbursement and 22 (13 trade names) that have received permanent reimbursement. Approximately nine VILPs (five trade names) are currently without coverage. The conditions for obtaining VILP status are mandated by law and are determined by the regulator, rather than by a contract between manufacturers and payers, and as such they do not fit the MEA definition used in this study. However, in the past few years, payers have insisted on including clauses on future MEAs for new VILP medicines. Other high-cost medicines without VILP status can also be subject of MEAs in the Czech Republic, but information on their existence is limited and details are confidential.

Fig. 2.

Total number of different MEA instruments implemented in Slovenia, Hungary, Latvia, Estonia and Romania in 2016. a Overall. One trade name may be associated with one or more MEA instruments, e.g. discount and payback, and these were counted separately. b By country. If a trade name was associated with more than one MEA instrument, e.g. discount and payback, these were counted separately. Data for Hungary include the retail sector only. MEA managed entry agreement

By type, Estonia was the country with the highest number of MEA instruments implemented (n = 237), followed by Slovenia (n = 234), Hungary (n = 159), Latvia (n = 42), and Romania (n = 6). In Estonia, if the medicine is not cost effective at the given price and/or the budget impact is too high, confidential discounts are negotiated; these totalled 230, hence the high number of agreements (Fig. 2b). These discounts are only valid for use in general pharmacies (outpatient) and not for inpatient use (hospital pharmacies) in Estonia. In Slovenia, MEAs were introduced in 2005 and are mandatory for all new medicines included in the reimbursement list, which explains the high number of MEAs in place in this country.

Discounts were the most common type of MEA implemented in Estonia (230 out of 237 agreements implemented in the country), Slovenia (181 out of 234 agreements implemented in the country), and Hungary (84 out of 159 agreements implemented in the retail sector country followed by 72 payback agreements). There are approximately 40 MEAs in the hospital sector in Hungary embedded into supply contracts won in central tenders; however, no information is publicly available on the type of MEA implemented in the hospital sector. In Hungary, some MEAs are also in place for products accessible based on individual patient applications (name-the-patient programme) but no information was available on type of agreement and medicines involved. Price-volume agreements were the most common MEA instrument used in Latvia (29 of 34 agreements implemented).

Total Number of Trade Names with MEAs Implemented by Therapeutic Area

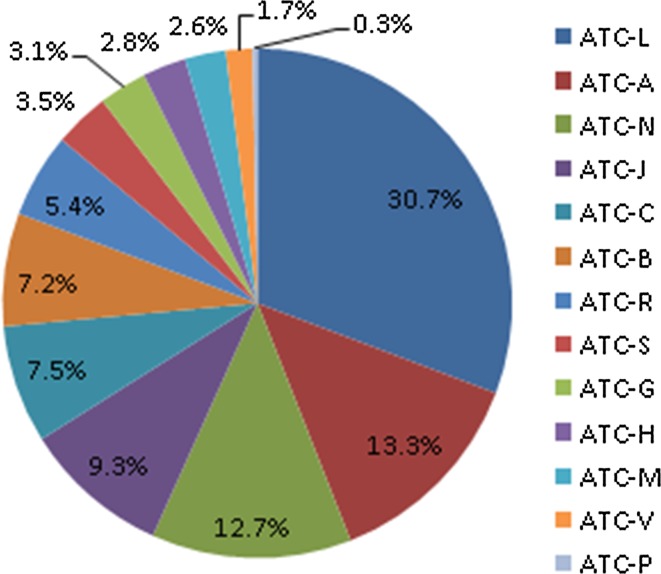

Across the seven countries with available data on the number of different MEA instruments implemented by therapeutic area (Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Serbia and Romania), the highest number of trade names associated with one or more MEA instruments belonged to the ATC-L group (n = 201, 31%); these were mostly for antineoplastic agents ATC-L01/02 (n = 103), and only a minority for immunomodulating agents ATC-L03/04 (n = 44)2. The second most frequent therapeutic group for MEA implementation was alimentary tract and metabolism, ATC-A (n = 87, 13%), most of which were implemented for medicines used in the treatment of diabetes ATC-A10 (n = 523), followed by nervous system ATC-N (n = 83, 13%), anti-infectives for systemic use ATC-J (n = 61, 9%), cardiovascular system ATC-C (n = 49, 7%), blood and blood-forming organs ATC-B (n = 47, 7%), respiratory system ATC-R (n = 35, 5%), sensory organs ATC-S (n = 23, 4%), genitourinary system and sex hormones ATC-G (n = 20, 3%), systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulin ATC-H (n = 18, 3%), musculoskeletal system ATC-M (n = 17, 3%), various ATC-V (n = 11, 2%), and antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents ATC-P (n = 2, 0.003%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of trade names with one or more MEAs, by therapeutic groups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Serbia, Estonia and Romania in 2015/16. The number of MEAs reported is by total number of trade names with one or more MEAs, while Fig. 2a, b present the total number of different MEA instruments implemented. The 230 discount agreements in the outpatient sector in Estonia were not included in Fig. 2 due to lack of data on the ATC group. The remaining agreements (n=6) with available ATC information in Estonia were included. MEA managed entry agreement, ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical, ATC-A alimentary tract and metabolism, ATC-B blood and blood-forming organs, ATC-C cardiovascular system, ATC-G genitourinary system and sex hormones, ATC-H systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulin, ATC-J anti-infectives for systemic use, ATC-L antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents, ATC-M musculoskeletal system, ATC-N nervous system, ATC-P antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents, ATC-R respiratory system, ATC-S sensory organs, ATC-V various. There are approximately 40 MEAs in the hospital sector in Hungary, approximately 25 of which were for oncology treatments (ATC-L01/02) and 15 were contracts for other therapeutic areas. Data for Hungary, Latvia, Serbia, Estonia and Romania refer to 2016, while data for Bulgaria and Lithuania refer to 2015

When counted by the number of different brand names associated with one or more MEA instruments, Bulgaria (n = 367) was the country with the highest number of different trade names associated with at least one MEA instrument, followed by Estonia (n = 236), Hungary (n = 134, retail sector only), Lithuania (n = 82), Latvia (n = 42), Serbia (n = 18), and Romania (n = 5) (Table 3). In Bulgaria since 2015, MEAs are required for all new medicines to be included in the reimbursement list and for on-patent medicines already included in the reimbursement list before 2015 to maintain coverage.

Table 3.

Number of trade names associated with one or more MEAs by therapeutic group in Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Serbia and Romania in 2015/16

| Bulgaria | Estonia | Hungary | Lithuania | Latvia | Serbia | Romania | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents (ATC-L) | 96 | 5 | 32 | 32 | 22 | 10 | 4 | 201 |

| Alimentary tract and metabolism (ATC-A) | 42 | 32 | 10 | 3 | 87 | |||

| Nervous system (ATC-N) | 51 | 18 | 9 | 5 | 83 | |||

| Anti-infectives for systemic use (ATC-J) | 35 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 61 |

| Cardiovascular system (ATC-C) | 36 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 49 | |||

| Blood and blood-forming organs (ATC-B) | 24 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 47 | ||

| Respiratory system (ATC-R) | 18 | 11 | 6 | 35 | ||||

| Sensory organs (ATC-S) | 19 | 3 | 1 | 23 | ||||

| Genitourinary system and sex hormones (ATC-G) | 13 | 7 | 20 | |||||

| Systemic hormonal preparations, excl. sex hormones and insulins (ATC-H) | 14 | 3 | 1 | 18 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal system (ATC-M) | 10 | 5 | 2 | 17 | ||||

| Various (ATC-V) | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||

| Antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents (ATC-P) | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Unknown | 230 | 230 | ||||||

| Total | 367 | 236 | 134 | 82 | 42 | 18 | 5 |

The number of MEAs reported is by total number of trade names with one or more MEAs. Data for Hungary cover the retail sector only. At hospital level, MEAs are embedded into supply contracts. There are approximately 40 MEAs in the hospital sector in Hungary, approximately 25 of which were for oncology treatments (ATC-L01/02) and 15 were contracts for other therapeutic groups. Data for Hungary, Latvia, Serbia, Estonia and Romania refer to 2016, while data for Bulgaria and Lithuania refer to 2015

MEAs managed entry agreements, ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

Termination of MEAs

The average duration of MEAs in the CEE countries included in this study is 2 years, ranging from 1 to 5 years, before the agreement is subject to re-negotiation (Table 4). In Latvia, the majority of agreements are open-ended. In most countries, either the agreement is renewed or a different agreement is signed (e.g. Slovenia). If the agreement is not renewed, the medicine may cease to be funded (e.g. Bulgaria and Romania). In Romania, after an agreement comes to an end and before a new one is negotiated, there can be a gap of 1–3 months. During this time period, the manufacturer takes over the cost of medicines for patients who have already started the treatment.

Table 4.

Duration of MEAs and next steps

| Duration | Possibility of renewal | |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | MEAs are not implemented | NA |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Not officially implemented as MEAs but discount arrangements are in place to facilitate access to new medicines by reducing their price and budget impact. Contract duration unknown Republika Srpska Discount agreements are linked to the tender process and are mostly valid for 1 year |

Yes |

| Bulgaria | One-year validity with annual renegotiation of discounts. If no discount is provided anymore, funding for the medicine stops | Yes |

| Croatia | 3 years, after which they are renegotiated, MEAs have to be renewed. The alternative would be delisting but this has not happened as of February 2017 | Yes |

| Czech Republic | MEAs between payers and manufacturers: unlimited with contractual notice terms, or for 3 years Coverage with evidence development (for highly innovative medicinal products, VILPs): 24 months, renewable for an additional 12 months, exceptionally renewable further if no alternative therapy exists. VILPs then either switch to permanent reimbursement, or are not reimbursed. In this case manufacturers are obliged to finance therapy for existing patients, unless they can receive alternative therapy |

Yes |

| Estonia | 1–2 years | Yes |

| Hungary | Retail sector: Contract duration can be 1–4 years by law; in practice, many schemes are for 2 years. Hospital sector: For contract-based schemes, the usual duration is 12 months, with some 24-month contracts | Yes |

| Kosovo | MEAs are not implemented | NA |

| Latvia | An MEA is a prerequisite for reimbursement for medicines with high budget impact and it is an agreement between the NHS and MAH. If the scheme comes to an end and no new agreement is reached, the medicine is no longer funded. The majority of these agreements are open-ended contracts | Yes |

| Lithuania | A minimum of 3 years | |

| Poland | Between 2 and 5 years before reassessment | Yes |

| Romania | 1 year, after which they may be renegotiated. To date, it seems that only one product was not renegotiated after the agreement came to an end | Yes |

| Russia | MEAs are not implemented | NA |

| Serbia | 3 years | Yes |

| Slovakia | Not yet implemented | NA |

| Slovenia | Initially 3 years. If the agreement is not prolonged, the medicine is included in the portfolio discount or another type of agreement | Yes |

MEAs managed entry agreements, NA not applicable, VILPs vysoce inovativní léčivý přípravek, NHS National Health Service, MAH marketing authorisation holder

Other Approaches to Managed Entry

MEAs are one set of instruments to improve access to new medicines, but they are not the only ones. For example, some countries allocate special funds to enable some patients to access new medicines. In the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (one of the two constitutional and legal entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina together with the Republic of Srpska), for instance, there is a special Solidarity Fund for the financing of so-called expensive medicines and services such as transplantation, oncology, biological therapies and HIV therapy following approval by a Committee (based on medical documentation and available budget). The list of medicines that may be eligible for reimbursement through the Solidarity Fund is available online [30]. The main problem with this approach are waiting lists to gain access to these medicines.

In the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the entry of new and expensive medicines is enabled through two lists of medicines reimbursed by the health insurance fund. These are the ‘List of medicines with the specific mode of acquisition’ and the ‘List of cytotoxic, biological and related medicines’; the latter came into effect in January 2016. The budget for these lists is planned annually and is funded from the overall budget of the health insurance fund. Medicines in these lists cover various therapeutic areas, including treatments for oncology, haemophilia, hepatitis B and C, cystic fibrosis, and multiple sclerosis. The lists specify the indication eligible for reimbursement.

Risk and Risk Sharing

Although these agreements are sometimes called risk-sharing agreements, only some of them have a true risk-sharing component (notably, paybacks and payment for performance). None of the countries included in this study specified in their legislation on MEAs what constitutes risk or risk-sharing, they only specify the types of agreements that may be implemented. Implicitly of course, the risk they are managing is the risk of overspending due to higher-than-forecasted volumes (addressed, for example, through paybacks) and paying high prices for medicines with limited added value in real-life or just unaffordable (addressed, for example, via payment for performance agreements.

Discussion

The extent of information available on MEAs varied substantially across the study countries. In Poland and Croatia, only the types of agreements allowed by the legislation are known, and some information is available on the submissions made but not on the approved agreements. In the Czech Republic, information about the existence of an agreement can, in principle, be extracted from the regulator’s public pricing and reimbursement decision (and since July 2017, also from a public sector contracts registry), but all details are confidential. While the details of the agreements (e.g. the level of discount) are in commercial confidence, the number of agreements implemented by the therapeutic group and type should be publicly available.

The experience in the CEE region in implementing MEAs was also very diverse. In Slovenia, MEAs have been implemented since 2006, while in Bulgaria and Romania they were introduced in 2015. They have not been (officially) implemented in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina (not formally identified as MEAs, but MEA-like agreements are in place), Kosovo, Russia and Slovakia (some confidential discounts are in place) as of March 2017. The types of agreements implemented were predominantly financial, with only very few health outcome-based agreements. A 2015–2016 study on MEAs in eight European countries and administrative areas showed that most of the agreements implemented for oncology medicines were financial [17]. Across all countries with data on the number of MEAs by therapeutic group, there was a strong focus on agreements for oncological and diabetes medicines, in line with findings from previous studies [1, 5, 8]. This is perhaps not surprising given the number of new oncology treatments launched (70 products for 20 uses between 2011 and 2015 [28]) and in clinical development (over 586 molecules in 2015, representing an increase of 63% over the past 10 years [31]) and their associated high entry prices, which can increase over the patent lifetime [2, 32, 33]. As for diabetes, the chronic nature of the disease, and the availability of effective generic alternatives, call for ways to reduce the budget impact of funding new patented medicines given concerns with their costs and side effects [3, 34]. In most cases, agreements are re-negotiated and funding for the medicine continues; however, there were exceptions. In Bulgaria and Romania, having an agreement in place is essential for reimbursement to be maintained. Consequently, if re-negotiations are not successful, funding for these medicines will be phased out.

Parallel trade can threaten medicines availability, which is an issue in various CEE countries. Simple direct discounts off the list price could make medicines attractive targets for parallel trade because these medicines could be sold in other countries at higher prices. Implementation of health outcome-based agreements, paybacks or price-volume agreements are less likely to make medicines more attractive targets for parallel trade (in comparison with medicines without an MEA) unless the list price is significantly lower than in other European countries.

Definition of MEAs

The understanding of what constitutes an MEA may differ across countries. For example, although its legislation does not officially permit MEAs, Slovakia implements some confidential discounts that would fit under the MEA definition used in this study. Some countries implement informal MEAs (in the sense that they do not classify them as MEAs). These include free doses, which have sometimes been used before formal MEA arrangements were put in place (e.g. Romania), as well as unofficial discounts in Slovakia. Coverage with evidence development (conditional/temporary reimbursement) in the Czech Republic and Slovakia is also functionally similar to MEAs, although in both countries it is determined by specific conditions defined by law, rather than contractually. However, the recent addition of MEAs to new temporarily reimbursed medicines in the case of the Czech Republic suggests that coverage with evidence development alone was not sufficient to mitigate the long-term financial risk for payers.

Differences in what is considered to be an MEA in one country versus what is considered to be an MEA in another country raises the question as to where the boundaries between MEAs and non-MEAs lie. In the end, what constitutes an MEA is a matter of definition. Consequently, when comparing MEA implementation across countries, it is therefore important to be aware that the understanding of what is classified as an MEA can differ between countries.

Administrative Burden

We found only a very small number of health outcome-based agreements involving monitoring of clinical outcomes in our study. This is likely to be in recognition that these agreements are resource intensive to implement and require good IT systems with electronic clinical records linked to reimbursement systems to be successfully enacted.

In most countries included in this study, the financial agreements in place need to be renegotiated on a regular basis (usually every 1–5 years). Depending on the effort required for their renegotiation, this can add administrative burden to MEA implementation, which needs to be considered when designing and implementing MEAs. For this reason, where MEAs cover a number of medicines, and where their duration is limited and their implementation is a precondition for reimbursement, authorities should consider whether the time invested in negotiation is not excessive and whether alternative options may prove less burdensome to administrate (e.g. negotiate the agreements for a longer period of time).

Beyond the frequency of re-negotiation, the type of agreement and the way it is implemented can have an important impact on the administration of the agreement. For example, payback agreements may involve a refund on overspending or the provision of free stock after an agreed threshold is reached. To keep the administrative burden to a minimum, countries implementing agreements involving refunds should consider whether obtaining the refund is labour intensive and whether it is effective (i.e. are refunds actually obtained and, if yes, are they obtained in a timely fashion?). In the case of free stock, is free stock promptly requested and provided after the agreed threshold is reached? Discounts were the most common type of agreement implemented in Slovenia, where only a limited number of payback agreements were in place. In a country such as Slovenia, where good treatment guidelines are in place and implemented [36], it may be easier to agree on the number of patients to be treated, along with a discount, rather than having payback agreements involving refunds in place.

Other Approaches to Improve Access

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, both The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Srpska, also have special funds and budgets in place for the financing of expensive medicines, which are innovative and under patent. Similar earmarked funds are available in Scotland (the New Medicines Fund funded by the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme [PPRS] rebates) [35] and England (the Cancer Drugs Fund) [36]. However, support for such earmarked funds is mixed. While they facilitate access, critics raised issues about fairness towards other disease areas and patient groups that are not eligible for special funding [3, 39]. Further, the views of a Patient and Clinician Engagement meeting in Scotland [37] and the end-of-life criteria in England [38] offer opportunities for special considerations affecting medicines for end-of-life and very rare conditions to be taken into account in the health technology assessment process.

Named-patient programmes, similar to the individual patient requests in the UK, have been implemented in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, but under different names. In Slovakia, for example, €32 million has been allocated for a population of 5.4 million inhabitants, totalling 4% of the pharmaceutical budget [40, 41]. In Hungary, €26 million was allocated for 2016 and €72 million was actually spent for a 9.9 million population. Overspending was due to delayed listing decisions for high-budget-impact medicines for the treatment of melanoma, prostate cancer and myeloma multiplex, among other therapeutic areas. Spending on exceptional reimbursement has also been increasing in the Czech Republic, where the largest health insurance fund alone spent €28.6 million in 2015, an almost threefold increase since 2013. New expensive medicines, which face the risk of being rejected on cost-effectiveness grounds, have been made available to some Slovak patients directly through the ‘system of exceptions’, without applying for regular reimbursement.

Definition of ‘Risk’, ‘Risk Sharing’ and High Prices

Considering how the agreements are implemented in European countries, risk seems to be implicitly defined as risk of excessive spending and/or spending on non-cost-effective medicines and/or use in patient groups for whom the medicine was not intended (quality use of medicines). What is defined as ‘risk sharing’ probably depends on what is considered to be ‘fair sharing’ between the payer and the manufacturer. In countries with hard incremental cost-effective ratio (ICER) thresholds, a fair level of ‘risk sharing’ could be defined as an agreement that reduces the actual price paid by the payer to a level that brings the medicine within the willingness-to-pay threshold of that country. We did not find any specific country definitions of what constituted ‘risk’ and ‘risk-sharing’, mainly because these agreements were not called risk-sharing agreements in national policy documents. The term ‘risk’ seems to have been used more in the literature [8, 12, 15, 42–48], particularly the theoretical literature, than in national policy documents, which could explain why the countries included in our study have not developed definitions for it.

Similarly, although the terms ‘high cost’ or ‘high priced’ are widely used in the literature and in policy discussion, there is no standardised definition of which medicines are classified as such. Again, implicitly, these medicines are broadly understood as being new medicines (i.e. still under patent), especially new biological medicines and targeted therapies, for the treatment of cancer, conditions affecting the immune system (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis), infectious diseases (hepatitis C), and rare conditions. For example, in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a list of expensive medicines eligible for funding through the Solidarity Fund is publicly available. While there is no definition of what an expensive medicine is, the list includes, not surprisingly, oncology, biological therapies and HIV medicines.

Limitations

Due to the confidentiality surrounding the agreements in place, only some of the countries were able to report quantitative informative on the type of agreements implemented and their therapeutic group.

Conclusions

We believe this is the first comprehensive comparative study on the implementation of MEAs in CEE involving key decision makers, their advisers and other senior personnel within these countries. While the information available on MEAs varied across countries, some preliminary conclusions and recommendations can be made. Experience in implementing MEAs varied substantially across the region and there is considerable scope for sharing experiences and mutual learning. To increase transparency, non-commercially sensitive information on the implementation of MEAs (type, therapeutic group) should be made publicly available. European citizens, authorities and the industry should ask themselves whether, within publicly funded health systems, confidential discounts can still be tolerated. This is all the more important given the lack of clarity as to which country and party are really benefiting from MEAs. Industry supports their implementation as a way to discriminate prices - and improve access in less resourced countries - in a system of international price referencing. The question is whether industry is best placed to ensure equity in access and whether it would offer larger discounts to countries that can least afford the new medicine and most need them. The lack of transparency is being allowed by the European Commission, but individual countries are finding price confidentiality increasingly unacceptable. This needs to be addressed.

The impact of MEAs on access to medicines should be monitored and evaluated. While a number of countries implement MEAs, strong budgetary pressures still apply, which limit the number of patients that can be treated with new expensive medicines, even in countries implementing MEAs. If MEAs are to improve access to medicines that bring meaningful added clinical value and are cost effective, countries should establish clear objectives for their implementation and a monitoring framework to measure their performance as well as the burden of implementation. In addition, they should look closely at issues of affordability among patients if this is a concern.

Overall, it appears unlikely that MEAs represent a sustainable solution to improving access to effective medicines that bring a meaningful added value to patients. If this was the case, countries implementing MEAs would not be struggling in balancing access and financial sustainability. In reality, MEAs seem to be a model that has been offered by the pharmaceutical industry and accepted by countries in the absence of a better alternative, which both parties are willing to implement. New models of financing research and development, and manufacturing and distributing medicines that address current unmet medical needs, are required to ensure sustainable and equitable access to new medicines.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jan Jones from the Scottish Medicines Consortium, Scotland, for contributing to the discussion with information on Scotland, Drs. Lyudmila Bezmelnitsyna and Anastasia Isaeva for contributing to data collection in Russia and Dr. Kateřina Podrazilová from SZP ČR for providing information on the Czech Republic.

Author contributions

AF and BG designed the study. AF compiled, cleaned and analysed the data collected by DA, TB, TC, DD, MD, JF, KG, IGK, IH, AJ, EL, OL, IM, VM-P, DM, TN, GP, MP, DT, LV. AF wrote the first draft of the manuscript and finalised it based on the comments received from DA, TB, TC, DD, MD, JF, KG, IGK, IH, AJ, EL, OL, IM, VMP, DM, TN, GP, MP, DT, LV, AH, PK, PVB and BG. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Data availability statement

Data on which this study was based are available in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and Table 3.

Funding

No sources of funding were used for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. However, Diāna Arāja, Maria Dimitrova, Jurij Fürst, Ieva Greičiūtė-Kuprijanov, Iris Hoxha, Arianit Jakupi, Erki Laidmäe, Vanda Markovic-Pekovic, Dmitry Meshkov, Guenka Petrova, Maciej Pomorski and Patricia Vella Bonanno work directly for national health authorities or are advisers to them. Alessandra Ferrario, Tomasz Bochenek, Ileana Mardare, Dominik Tomek, Luka Voncina, Alan Haycox, Panos Kanavos, Olga Löblová, and Brian Godman are academics and independent researchers also working with national and regional health authorities and others to improve the quality and efficiency of prescribing, and Tarik Catic, Dávid Dankó,and Tanja Novakovic are involved with pharmaceutical, pharmacoeconomics and outcomes research groups in their countries. Olga Löblová has also carried out remunerated consultancy activities for A&R Partners, Baxter AG and Instytut Arcana and Ileana Mardare has signed a consulting contract with Ewopharma A.G. Romania. The content of the paper and the conclusions are those of each author and may not necessarily reflect those of any organisation that employs them.

Footnotes

In January 2017, the United Nations (UN) has changed the status of Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) from Eastern Europe to Northern Europe. In this study, we consider them as part of CEE countries.

For 54 ATC-L agreements, the therapeutic group was only known at ATC-1 level, not ATC-2.

For 13 ATC-A agreements, the therapeutic group was only known at ATC-1 level, not ATC-2.

Alessandra Ferrario was a Research Officer at the LSE Health at the time this research was conducted. She is now a postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, USA. Email: Alessandra_Ferrario@harvardpilgrim.org

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40273-017-0559-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Alessandra Ferrario, Email: A.Ferrario@lse.ac.uk.

Diāna Arāja, Email: Diana.Araja@rsu.lv.

Tomasz Bochenek, Email: mxbochen@cyf-kr.edu.pl.

Tarik Čatić, Email: tarikcatic@bih.net.ba.

Dávid Dankó, Email: david.danko@uni-corvinus.hu.

Maria Dimitrova, Email: mia_dimitrova@yahoo.com.

Jurij Fürst, Email: Jurij.Furst@zzzs.si.

Ieva Greičiūtė-Kuprijanov, Email: Ieva.Greiciute-Kuprijanov@sam.lt.

Iris Hoxha, Email: iris.hoxha@umed.edu.al.

Arianit Jakupi, Email: arianiti@gmail.com.

Erki Laidmäe, Email: Erki.Laidmae@haigekassa.ee.

Olga Löblová, Email: olga.loblova@gmail.com.

Ileana Mardare, Email: ileana.mardare@umfcd.ro.

Vanda Markovic-Pekovic, Email: v.mpekovic@mzsz.vladars.net.

Dmitry Meshkov, Email: meshkovdo@nriph.ru.

Tanja Novakovic, Email: tanjabel@hotmail.com.

Guenka Petrova, Email: guenka.petrova@gmail.com.

Maciej Pomorski, Email: m.pomorski@aotm.gov.pl.

Dominik Tomek, Email: tdmia@slovanet.sk.

Luka Voncina, Email: Lvoncina@gmail.com.

Alan Haycox, Email: a.r.haycox@liverpool.ac.uk.

Panos Kanavos, Email: p.g.kanavos@lse.ac.uk.

Patricia Vella Bonanno, Email: patricia.vella-bonanno@strath.ac.uk.

Brian Godman, Phone: 0141 548 3825, Phone: +46 8 58581068, Email: Brian.godman@strath.ac.uk, Email: Brian.Godman@ki.se.

References

- 1.Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Dealing with uncertainty and high prices of new medicines: a comparative analysis of the use of managed entry agreements in Belgium, England, the Netherlands and Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 2014;124:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard DHBP, Berndt ER, Conti RM. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(1):139–162. doi: 10.1257/jep.29.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Access to new medicines in Europe: technical review of policy initiatives and opportunities for collaboration and research. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/306179/Access-new-medicines-TR-PIO-collaboration-research.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 4.Carlson JJ, Sullivan SD, Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Veenstra DL. Linking payment to health outcomes: a taxonomy and examination of performance-based reimbursement schemes between health care payers and manufacturers. Health Policy. 2010;96(3):179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrario A, Kanavos P. Managed entry agreements for pharmaceuticals: the European experience. Brussels, Belgium: EMiNet. 2013. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50513/1/__Libfile_repository_Content_Ferrario%2C%20A_Ferrario_Managed_%20entry_%20agreements_2013_Ferrario_Managed_%20entry_%20agreements_2013.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 6.Garrison LJ, Towse A, Briggs A, de Pouvourville G, Grueger J, Mohr P, et al. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements-good practices for design, implementation, and evaluation: report of the ISPOR good practices for performance-based risk-sharing arrangements task force. Value Health. 2013;16(5):703–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollis A. Sustainable financing of innovative therapies: a review of approaches. PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(10):971–980. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson J, Chen S, Garrison LP Jr. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements: an updated international review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017. doi:10.1007/s40273-017-0535-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lu C, Lupton C, Rakowsky S, Babar Z, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner A. Patient access schemes in Asia-pacific markets: current experience and future potential. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2015;8(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s40545-014-0019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarosławski S, Toumi M. Design of patient access schemes in the UK: influence of health technology assessment by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(4):209–215. doi: 10.2165/11592960-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaroslawski S, Toumi M. Market access agreements for pharmaceuticals in Europe: diversity of approaches and underlying concepts. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):259. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Towse A, Garrison LP. Can’t get no satisfaction? Will pay for performance help? toward an economic framework for understanding performance-based risk-sharing agreements for innovative medical products. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(2):93–102. doi: 10.2165/11314080-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrison LJ, Carlson J, Bajaj P, Towse A, Neumann P, Sullivan S, et al. Private sector risk-sharing agreements in the United States: trends, barriers, and prospects. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(9):632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrison LP, Towse A. Toward an economic framework for understanding performance-based risk-sharing agreements for innovative medical products. Value Health. 2009;12(7):A488. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3015(10)75309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adamski J, Godman B, Ofierska-Sujkowska G, Osinska B, Herholz H, Wendykowska K, et al. Risk sharing arrangements for pharmaceuticals: potential considerations and recommendations for European payers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:153. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klemp M, Frønsdal KB, Facey K. What principles should govern the use of managed entry agreements? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017;27(1):77–83. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauwels K, Huys I, Vogler S, Casteels M, Simoens S. Managed entry agreements for oncology drugs: lessons from the european experience to inform the future. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8(171):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garattini L, Casadei G. Risk sharing agreements: What lessons from Italy? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(2):169–172. doi: 10.1017/S0266462311000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garattini L, Curto A, van de Vooren K. Italian risk-sharing agreements on drugs: are they worthwhile? Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navarria A, Drago V, Gozzo L, Longo L, Mansueto S, Pignataro G, et al. Do the current performance-based schemes in Italy really work? “Success fee”: a novel measure for cost-containment of drug expenditure. Value Health. 2015;18(1):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon S, Clopes A, Gasol-Boncompte M, Cajal R, Segu J, Crespo R, et al. Evaluation of a payment by result scheme in a Catalan cancer centre: Gefitinib in EGFR mutation-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A492. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garattini L, Curto A. Performance-based agreements in Italy: ‘Trendy Outcomes’ or mere illusions? PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(10):967–969. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araja D, Kolves K. Managed entry agreements for new medicines in the Baltic countries. EuroHealth. 2016;22(1):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwong D, Ferrario A, Adamski J, Inotai A, Kalo Z. Managing the introduction of new and high-cost drugs in challenging times: the experience of Hungary and Poland. EuroHealth. 2014;20(2):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matusewicz W, Godman B, Pedersen HB, Furst J, Gulbinovic J, Mack A, et al. Improving the managed introduction of new medicines: sharing experiences to aid authorities across Europe. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(5):755–758. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1085803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK, Sokka T, Pavlova M, Uhlig T, et al. Inequities in access to biologic and synthetic DMARDs across 46 European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):198–206. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kostic M, Djakovic L, Sujic R, Godman B, Jankovic SM. Inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis): cost of treatment in Serbia and the implications. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(1):85–93. doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0272-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piperska. 2017. http://www.piperska.org/. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 29.Godman B, Paterson K, Malmstrom RE, Selke G, Fagot JP, Mrak J. Improving the managed entry of new medicines: sharing experiences across Europe. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(4):439–441. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health Insurance of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, list of decisions on medicines. http://www.fedzzo.com.ba/bs/dokument/odluka-o-listi-lijekova/215. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

- 31.IMS Institute. Global oncology trend report. A review of 2015 and outlook to 2020. 2016. http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/global-oncology-trend-report-a-review-of-2015-and-outlook-to-2020#. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 32.Tefferi A, Kantarjian H, Rajkumar SV, Baker LH, Abkowitz JL, Adamson JW, et al. In support of a patient-driven initiative and petition to lower the high price of cancer drugs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(8):996–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennette C, Richards C, Sullivan S, Ramsey S. Steady increase in prices for oral anticancer drugs after market launch suggests a lack of competitive pressure. Health Aff. 2016;35(5):805–812. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godman B, Malmstrom RE, Diogene E, Gray A, Jayathissa S, Timoney A, et al. Are new models needed to optimize the utilization of new medicines to sustain healthcare systems? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8(1):77–94. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.990380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery B. Review of access to new medicines independent review by Dr Brian montgomery. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. 2016. http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00511595.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 36.NHS England. Cancer drugs fund. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/cdf/. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 37.Scottish Medicines Consortium. Patient and clinician engagement. 2017. https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/About_SMC/Latest_news/News_Articles/Patient_and_Clinician_Engagement_Factsheet. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 38.NICE. Appraising life-extending, end of life treatments. Supplementary advice to the Appraisal Committees. London. 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-tag387/resources/appraising-life-extending-end-of-life-treatments-paper2. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 39.Haycox A. Why Cancer? PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34(7):625–627. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0413-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Černěnko M, Dančíková Z, Friedmanová M, Harvan P, Kišš Š, Laktišová M, et al. Revízia Výdavkov Na Zdravotníctvo. Záverečná Správa. Ministervo financií SR, Ministerstvo zdravotníctva SR. 2016.

- 41.Piško M. Drahá Liečba Závisí Aj Od Sily Hlasiviek. 2016.

- 42.Barros PP. The simple economics of risk-sharing agreements between the NHS and the pharmaceutical industry. Health Econ. 2011;20(4):461–470. doi: 10.1002/hec.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook JP, Vernon JA, Manning R. Pharmaceutical risk-sharing agreements. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(7):551–556. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonanzas F, Juarez-Castello C, Rodriguez-Ibeas R. Should health authorities offer risk-sharing contracts to pharmaceutical firms? A theoretical approach. Health Econ Policy Law. 2011;6(3):391–403. doi: 10.1017/S1744133111000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lilico A. Risk sharing pricing models in the distribution of pharmaceuticals. London: Europe Economics. 2003. http://www.europe-economics.com/publications/risk_sharing_al.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

- 46.Barros P, Levaggi R. Searching for approval: risk sharing as price discount? Mimeo; 2013. https://www.gate.cnrs.fr/IMG/pdf/EHEW_2013_Levaggi.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2017.

- 47.Zaric GS, O’Brien BJ. Analysis of a pharmaceutical risk sharing agreement based on the purchaser’s total budget. Health Econ. 2005;14(8):793–803. doi: 10.1002/hec.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaric GS, Xie B. The impact of two pharmaceutical risk-sharing agreements on pricing, promotion, and net health benefits. Value Health. 2009;12(5):838–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Croatian Health Insurance Fund, Pravilnik o mjerilima za stavljanje lijekova na osnovnu i dopunsku listu. http://www.hzzo.hr/zdravstveni-sustav-rh/pravilnik-o-mjerilima-za-stavljanje-lijekova-na-osnovnu-i-dopunsku-listu. Accessed 11 Aug 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data on which this study was based are available in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and Table 3.