Abstract

Stromatolites are the oldest evidence for life on Earth, but modern living examples are rare and predominantly occur in shallow marine or (hyper-) saline lacustrine environments, subject to exotic physico-chemical conditions. Here we report the discovery of living freshwater stromatolites in cool-temperate karstic wetlands in the Giblin River catchment of the UNESCO-listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, Australia. These stromatolites colonize the slopes of karstic spring mounds which create mildly alkaline (pH of 7.0-7.9) enclaves within an otherwise uniformly acidic organosol terrain. The freshwater emerging from the springs is Ca-HCO3 dominated and water temperatures show no evidence of geothermal heating. Using 16 S rRNA gene clone library analysis we revealed that the bacterial community is dominated by Cyanobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and an unusually high proportion of Chloroflexi, followed by Armatimonadetes and Planctomycetes, and is therefore unique compared to other living examples. Macroinvertebrates are sparse and snails in particular are disadvantaged by the development of debilitating accumulations of carbonate on their shells, corroborating evidence that stromatolites flourish under conditions where predation by metazoans is suppressed. Our findings constitute a novel habitat for stromatolites because cool-temperate freshwater wetlands are not a conventional stromatolite niche, suggesting that stromatolites may be more common than previously thought.

Introduction

Stromatolites are a form of microbialite with repetitive, laminated structures of biologically (typically cyanobacteria) mediated mineral precipitation1,2. These microbial accretions are the oldest evidence for life on Earth2–6 and debates continue on whether they evolved first on land or in the ocean4,7–10. Fossilized stromatolites and similar accretionary microbial mats have provided intriguing microbial archives for over a century11,12, revealing that microbialites were abundant in the shallow late-Archean and Proterozoic oceans, but declined with the emergence of multicellular life in the Cambrian2,13. The evolution of grazing metazoans has therefore been suggested as a primary cause of stromatolite decline during the history of life on Earth. However, the role of metazoans in limiting stromatolite formation has been questioned14,15, and a living example for the co-occurrence of stromatolites and benthic macroinvertebrates has recently been reported16. Evidence from gene sequencing also suggests that microbialites support diverse and distinct active eukaryotic communities which may influence microbialite structure17.

Modern living stromatolites are rare but occur in diverse habitats which are often subject to extreme conditions inhospitable to other life forms1,12,18,19. Well-known living examples are shallow marine stromatolites in Hamelin Pool, Shark Bay, Western Australia2–6, and the shallow subtidal stromatolites in Highborne Cay, Bahamas4,7–10. Other occurrences include (hyper-) saline lacustrine environments such as Storr’s Lake, Bahamas11,12, a hyper-saline lake of the Kiritimati Atoll, Central Pacific2,20, high-altitude Lake Socompa, Argentina14,15, and supratidal pools along the coastline of South Africa16,21. However, stromatolites growing in low-salinity, low-temperature freshwaters have also been recognized at localities such as: Ruidera Pools Natural Park, Spain22, Pavilion Lake, British Columbia, Canada23, karst-water creeks in Germany and France24,25, cenote lakes in south-eastern mainland Australia26, and tufa depositing streams in SW Japan27.

The Giblin River catchment and certain others in south-west Tasmania, Australia, contain significant concentrations of unusual wetlands comprising poorly drained, sparsely vegetated sandy to gravelly flats of variable size and shape (Fig. 1, SI Fig. 1). Older literature refer to these features as ‘alkaline pans’28, because the water is neutral to mildly alkaline (pH ~7–8), creating exceptional pH gradients across the boundary between the wetlands and surrounding acidic blanket bogs (pH ~4–5). This is striking because the majority of surface waters in south-west Tasmania are strongly acidic due to the high humic content of the soil29. We refer to these features as ‘peat-bound karstic wetlands’, because they comprise ‘islands’ of peat-free ground within otherwise monotonous organosol terrain of karstic limestone and dolomite valleys (the term alkaline pan is conventionally reserved for dryland evaporite features). Previously interpreted as ephemeral disturbance features due to burning of the peat with resultant exposure of underlying alkaline substrates, water chemistry data lead us to re-interpret the peat-bound karstic wetlands as spring-fed groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

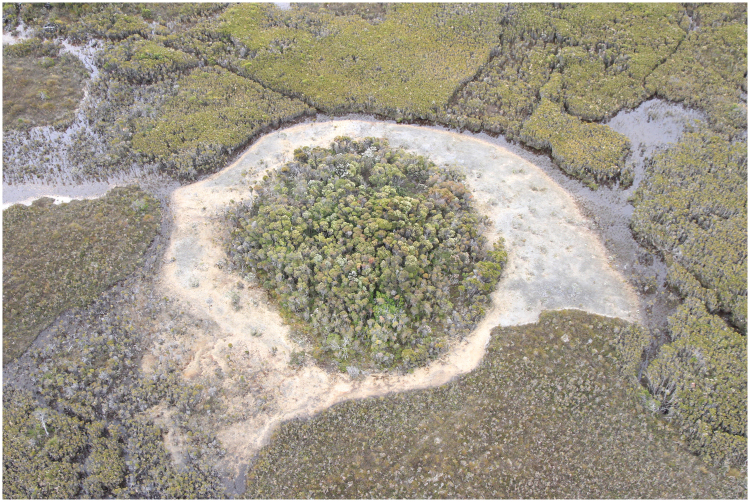

Figure 1.

Aerial view of a prominent Giblin River spring mound (site GR5 and transect). The shrubby centre conceals marshy ground and shallow ponds which discharge groundwater. The pale outer band is calcareous mud and tufa colonized by stromatolites. This example is 60 m in diameter.

Recent visits to peat-bound karstic wetlands in the Giblin River catchment revealed that their surfaces are colonized by aggregations of stromatolites (Fig. 2A). There are no previous records of stromatolites in Tasmania, except as Ordovician and Precambrian fossils30. We have studied the microbial structure of the Giblin River stromatolites and characterize the physico-chemical conditions of their habitat to determine environmental parameters that control and allow modern freshwater stromatolite formation in this region.

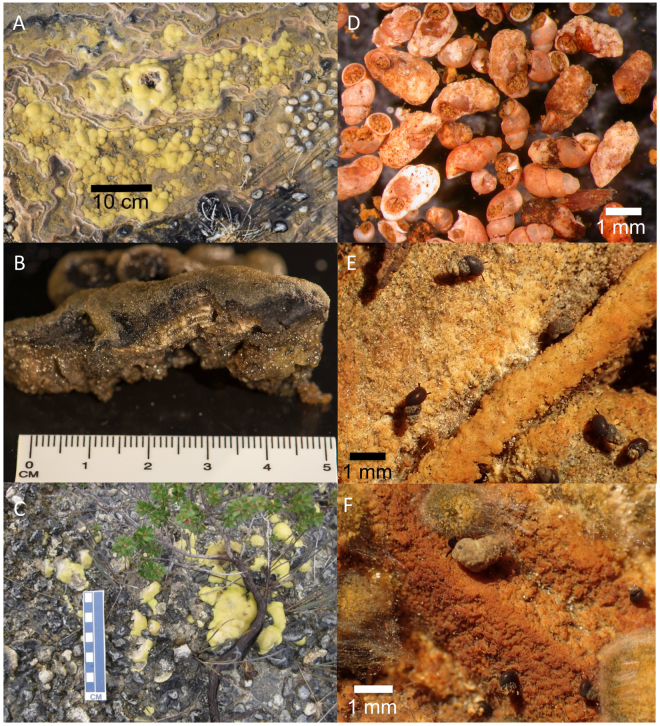

Figure 2.

Giblin River stromatolites and macroinvertebrates: stromatlites in growth position (A,C); sectioned sample with calcite laminations (B), photograph taken by R. Wiltshire; dead and calcified snail shells from mound slopes (D) and live grazing snails (Austropyrgus pisinnus.) with light (E) and heavy (F) Ca-encrustations.

Results and Discussion

Stromatolites colonize the lower, peripheral slopes of the Giblin River spring mounds, forming smooth mats of yellowish and greenish, globular structures growing on the wetted surface of tufa barriers (Fig. 2A,B and C). The stromatolites are not fully submerged in water and almost appear as a ‘terrestrial’ variant rising several centimeters above the wet surface (Fig. 2C). The high amount of precipitation in this area (~2500 mm) may therefore contribute to stromatolite survival at this site. The largest examples are ~10 cm in diameter but most are considerably smaller. Internally, the structure of the stromatolites presents a regular layered succession of pale and dark laminae, each about a millimeter thick in cross section (Fig. 2B). Raman spectroscopy of the pale layers showed distinct peaks at around 288, 719 and 1090 cm−1 (SI Fig. 2), revealing that they are crystalline calcite (CaCO3).

Water Chemistry

Water chemistry data corroborates our interpretation of the Giblin River wetland as a class of groundwater-dependent ecosystem. Water from the spring mounds (GR2, GR5) is mildly alkaline freshwater with a pH of 7.5–7.6, zero salinity, and electrical conductivity of 618–640 µS cm−1. The temperature indicates negligible geothermal heating (10.6–14.4 °C). These waters are Ca-HCO3 dominated, followed by Cl, Mg, Na and SO4 (SI Fig. 3, SI Table 1). In contrast, soil water from the surrounding blanket bog is Na-Cl dominated and acidic (pH 5.3), whereas the water of the peat-bound karstic wetland is of intermediate character consistent with mixing of bog and spring waters (Fig. 3). Water isotope analysis revealed this water is meteoric in origin, and has undergone negligible evaporation (SI Fig. 4).

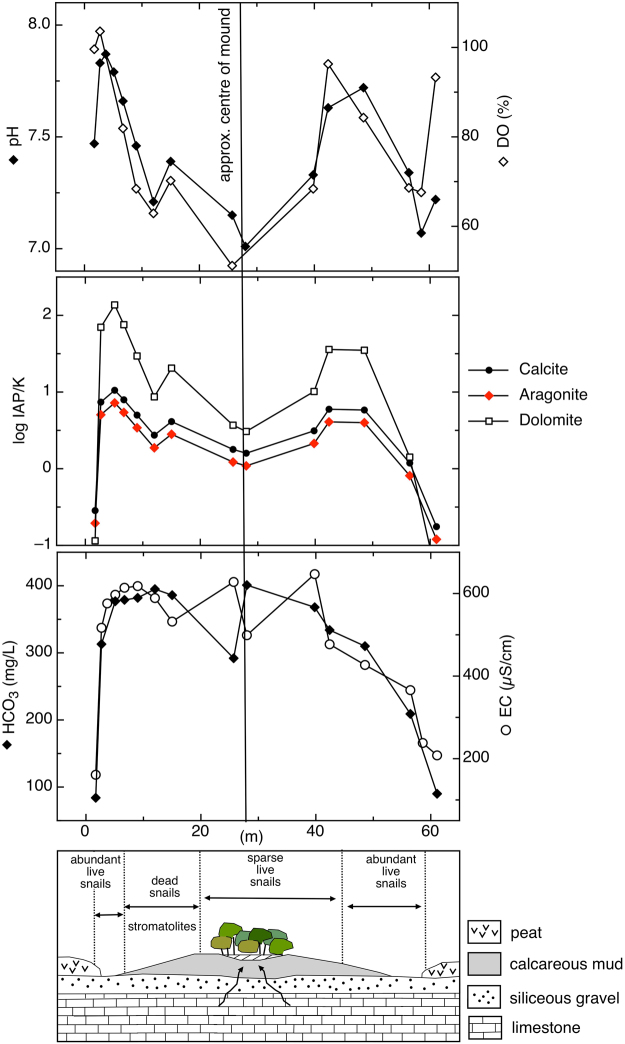

Figure 3.

pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), saturation indices (logIAP/K), bicarbonate (HCO3) and electrical conductivity (EC) results along transect across the mound. Concentrations of dead Ca-encrusted snails on the middle slopes are associated with a shift towards higher pH and SI, as shown in the lower schematic. In fact, most parts of the mound, except the central pond and mixing zone on the periphery, show evidence of active calcite deposition.

The transect across the largest mound revealed a distinct pattern of physical and chemical water properties from the centre of the mound towards the peatland (Fig. 3). The spring at the centre of the mound discharges slightly super-saturated water with respect to calcite and aragonite, representative of groundwater in close equilibrium with CaCO3 under conditions of elevated pCO2. As the water flows downslope towards the edge of the mound, it equilibrates with atmospheric pCO2 (degasses) resulting in increasing saturation indices (SI), causing precipitation of CaCO3. As Ca precipitates and the water mixes with acidic peat water (pH 5.3) towards the margin of the mound, saturation indices decrease markedly and waters are under-saturated with respect to calcite, aragonite, and dolomite. We also noted that dolomite saturation features a similar behavior compared to calcite and aragonite SI across the mound, but indices are twice as high towards the slopes of the mound (SI > 2) (Fig. 3). However, Raman spectroscopy of the precipitates indicate calcite, not dolomite, in line with the ‘dolomite problem’31 (that is, whereas basic chemical principles appear to allow crystallization of dolomite under common earth surface conditions, this does not occur in nature and instead dolomite precipitation appears to require either geological timescales or other special conditions). Aragonite or biologically formed amorphous calcium carbonate would result in different Raman spectra compared to crystalline calcite32. Our findings are consistent with the observed behavior of typical tufa-depositing springs elsewhere in the world33, although biotic processes (e.g. microbial metabolism) may contribute at some level to the observed chemical evolution of the water flowing across the mound.

Stromatolite Composition

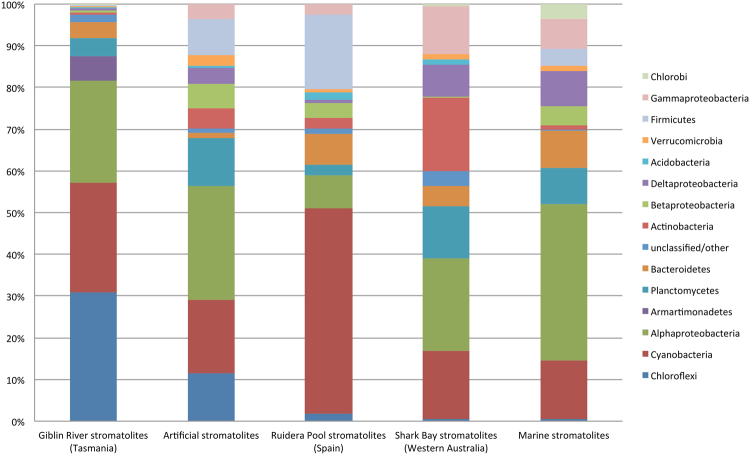

16 S rRNA gene sequence analysis of the bacteria from two representative stromatolite samples revealed that the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of the Giblin River stromatolite bacterial community belonged mainly to Cyanobacteria, Chloroflexi, Armatimonadetes, Alphaproteobacteria and Planctomycetes (Fig. 4). Cyanobacterial diversity (26.4% of reads) was extensive (113 OTUs) and OTUs found are largely distinct from cultured taxa, with the main phylotypes most similar to cyanobacteria from soil crust and freshwater lake and biofilms samples34–37. Chloroflexi phylotypes formed two major clades (30.8% of reads, 131 OTUs), including one that branched within class Chloroflexia and another that represented a branch within the class Anaerolineae. The latter clade was distant from the cultured representatives of the Anaerolineaceae 38, but were most similar to taxa from biofilms of rock surfaces and mineral springs such as those described by Tomcyzk-Zak et al.39 and Headd & Engel40. The community composition data also implied the presence of a wide diversity of heterotrophic species normally found in abundance in oligotrophic freshwater ecosystems including microbial mats and stromatolites41,42. These taxa include members of the genera Caulobacter, Hyphomicrobium, families Hyphomonadaceae, Sphingomondaceae, Cytophagaceae, Saprospiraceae, and the phyla Planctomycetes and Armatimonadetes. Potentially these bacteria may depend on carbon derived from cyanobacterial primary production or could assist in decomposition of the cyanobacterial mats. Overall, based on the OTUs detected, there was limited evidence of strictly anaerobic bacteria being also present in the samples, which is consistent with the samples analysed being derived from a largely active photosynthetic mat growing on tufa. Overall, the OTUs detected were generally distinct from cultured and uncultured bacterial taxa and showing no close correspondence to OTUs detected in other stromatolite systems, including freshwater stromatolites22 and lake microbialites23,43 (Fig. 4). In this respect very few of the Giblin River OTUs displayed >98% similarity to known sequences on the database, indicating a comparatively unique community. This could partly reflect a general lack of data on microbial communities associated with freshwater spring-type ecosystems.

Figure 4.

Bacterial diversity present in stromatolites defined by the proportion of 16 S rRNA gene sequences for each given taxonomic group present. The Tasmanian data is from the Giblin River (this study); artificial stromatolites derived from Type 2 Highborne Cay stromatolites57; freshwater stromatolites from Ruidera Pool, Spain22; stromatolites from Shark Bay, Western Australia3,5,56; marine water derived Highborne Cay stromatolites7,10,56; and Pavilion Lake, Canada, lake microbialites23.

Given the uniqueness of the microbial community composition within Giblin River spring mound stromatolite formations, they could derive from local species present in adjacent spring water, soil and rock biofilms. However, to date, none of these ecosystems have received any detailed microbiological study and thus a complete comprehension of the microbiology of the stromatolites will require analysis of the surrounding Giblin River spring and wetland system.

Macroinvertebrates

The rapid evolution of multicellular life in the Cambrian is believed to have caused the decline of stromatolite abundance15. We have therefore investigated macroinvertebrate abundance at the Giblin River spring mounds. Macroinvertebrate sampling indicates that the Giblin River spring mounds host a sparse assemblage of invertebrate taxa most of which are not yet identifiable to known, described species (SI Table 2). These include a planarian (Platyhelminthes), nematodes, oligochaetes in the Naiididae and Tubificidae, and juvenile specimens of a stonefly (Plecoptera: Gripopterygidae). A small number of microcrustacea were found (Ostracoda, harpacticoid and calanoid Copepoda), but the most prominent crustaceans were specimens of Paraleptamphopus spp., an amphipod genus previously regarded as endemic to New Zealand44. Molluscan diversity is comparable with surrounding catchments45,46 with 7 species or forms recorded: a bivalve (Pisidium sp.), the Planorbidae Glyptophysa gibbosa, and 5 Hydrobiidae: Phrantela singularis, Phrantela angulifera, Austropyrgus pisinnus and 2 unidentified Phrantela spp., with A. pisinnus and P. singularis being most abundant. The relative abundance of other snail species is low. Many snails, both live and deceased, were affected by carbonate encrustations on the shell – in some cases the original form of dead shells were entirely obscured by bulbous masses of accreted minerals (Fig. 2E,F). The attendant increase in mass implies increased energy consumption during movement and, ultimately, the shell may become too cumbersome or heavy for the animal to maintain mobility (Fig. 2F). Even if calcification does not actually kill affected snails, it likely has a debilitating effect which increases their susceptibility to risk factors, such as disease, predation or desiccation. Ca-encrustation was observed profiling all age stages of the snails.

We hypothesize that the mortality rate is higher amongst calcified snails and that this is responsible for suppressing snail abundance on the spring mounds. This is supported by observed mass mortality of snails in the form of dense accumulations of empty shells on the slopes of the spring mounds (Fig. 2D) and sparse live snails subject to Ca-encrustation (Fig. 2E and F). It appears that snails are particularly disadvantaged on the middle and lower slopes of the spring mounds where our data indicate conditions of increasing pH and carbonate saturation, with attendant potential for mineral precipitation downslope of the mound (Fig. 3). Elevated snail mortality implies periods of reduced predation on microbial films, the food source of the aquatic snails47. The coexistence of macroinvertebrates and marine stromatolites has recently been reported for a site in South Africa16, suggesting that metazoan co-occurrence may play a reduced role in limiting stromatolite growth48,49. However, we observed that areas with abundant living snails, including Phrantela, the largest of the gastropod species that could potentially cause significant damage by grazing, did not coincide with patches of stromatolite occurrence. We therefore suggest that Ca-precipitation and encrustation of live snails regulate metazoan abundance at this site, and infer that this mechanism has contributed to the suitability of the Giblin River spring mounds as a stromatolite habitat.

Conclusion

The discovery of stromatolites growing on spring mounds in the Giblin River catchment provides an exciting, novel example of the range of habitats known to support this ancient life form. The comparatively benign physico-chemical conditions of this habitat contrasts with the more typically extreme conditions normally associated with stromatolites. This raises the possibility that stromatolites colonize a broader range of temperate freshwater environments than presently recognized. We anticipate our findings will be a starting point for new investigations and models on modern stromatolite formation in temperate freshwater habitats.

Methods

Study Site

The Giblin River catchment is located in south-west Tasmania, Australia (−42°56′S, 145°45′E), and lies within the UNESCO-listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. This region experiences cool temperate maritime conditions dominated by ‘roaring forties’ weather off the Southern Ocean (mean annual air temperature: 13 °C; mean annual rainfall: 2512 mm; Australian Bureau of Meteorology 1981–2010 data). The Giblin River occupies a broad syncline where dissolution of Ordovician limestone has produced an undulating, low-relief surface a few tens of metres above sea level. This surface is largely covered by Tertiary siliceous alluvial gravels and Holocene blanket bogs, a form of ombotrophic peatland which mantles large tracts of western Tasmania. The vegetation is dominated by grassy to shrubby moorland, generally considered a successional disclimax related to earlier indigenous burning. The catchment is isolated from settled areas to the east (>100 km) by rugged topography and its natural values are poorly documented.

Within the Giblin River catchment occur peat-bound karstic wetlands that are regionally distinctive due to the presence of prominent spring mounds (Fig. 1). The mounds are up to 60 m in diameter with densely vegetated marshy tops, but only rise up to approximately 0.5 m above surrounding wetlands. This study site was visited twice by helicopter, on 4 December 2015 and 18 August 2016.

Raman spectroscopy

A cross-section of a representative stromatolite sample collected near site GR2 during the first visit (December 2015, Fig. 2B) was examined by Raman point analyses at the Central Science Laboratory, University of Tasmania. The Raman spectrum was recorded on a Renishaw inVia Raman spectrometer with StreamlineHR using a laser diode excitation at 785 nm with a power output of 55 mW at the sample, 20x (NA 0.40) objective, 10 s exposure and a grating of 1200 l/mm resulting in a spectral resolution of about 1.2 cm−1 between 220 and 1200 cm−1. The spectrum was baseline corrected to remove the background fluorescence.

Water sampling and analyses

Water sampling was undertaken at four locations within the wetland (GR1 to GR4) in December 2015 and at two locations in August 2016 (GR5 and GR6, SI Fig. 1). GR1, GR3 and GR4 are samples from within the wetland, GR2 and GR5 at locations where water flow was visible and likely to present spring water outflow. Sample GR6 was taken well within the peatland underlain by Tertiary siliceous gravel surrounding the site. During the second visit in August 2016, we also conducted water sampling along a 61.7 m long transect through the largest mound (Fig. 1, and near GR5 in SI Fig. 1). Electrical conductivity (EC), pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen (DO) were measured in situ using a HACH multiprobe (HQ40d), and salinity using a salinity refractometer. Samples for ion chemistry were collected in 50 ml centrifuge tubes after 0.45 µm filtration. Samples for bicarbonate titrations were not filtered. All water samples were stored below 4 °C until further analyses. Major anions and cations were analysed by ion chromatography (Dionex ICS-3000) at the Australian Centre for Research on Separation Science (ACROSS), University of Tasmania. Bicarbonate and total alkalinity were determined by titration with HCl. Water samples were also analysed for water isotopes (δ18O and δ2H) using a Picarro Laser Cavity Ringdown Spectrometer at the Australian Antarctic Division, Hobart.

Saturation indices (SI) were calculated using the software Geochemist’s Workbench® and are defined as SI = logIAP/K, where IAP is the ion activation product and K the equilibrium constant.

Stromatolite sampling, sequence analysis, and community composition

Two microbial samples of stromatolitic smooth mats were collected in 50 ml centrifuge tubes near site GR2 during the first visit (December 2015), and stored below 4 °C until further analysis. DNA extraction was performed on both samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 16 S rRNA gene sequence analyses were subsequently performed using services and facilities at the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF). PCR primers used were for the V1 to V3 domain regions of the 16 S rRNA gene including 27 F (AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG) and 519 R (GWA TTA CCG CGG CKG CTG). Following purification of the amplicons dual indices and adapter primers were added to the amplicons using the Nextera XT Library Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Following denaturation and pooling the libraries were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform according to standard protocols generating 300 bp pairended reads. Sequence processing and assessment was performed by joining FastQ files using FastX (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html). Reads were then quality filtered and denoised in Mothur v. 1.35.150,51. Sequences with a mean PHRED score of >30 and containing bases of scores <8 were discarded. Alignment, clustering and chimera removal was then performed using UPARSE52. After manual inspection there was still potential evidence of chimeras amongst OTUs despite use of UCLUST as a result clusters were further checked for chimeras using DECIPHER in short sequence mode53. This approach was useful in flagging potential chimeras for assessment. Singleton reads were excluded from further analysis. The remaining OTUs were classified using PyNAST 1.154 against the Greengenes database (March 2013 version)55. From the two samples 152145 and 127009 reads were obtained after filtration and grouped collectively into 1063 OTUs at the 97% level. Both samples were highly similar sharing 61.4% of the OTUs. Of the OTUs 208 were designated unclassified. Manual alignments were performed to assess their phylogenetic placement by utilizing a combination of Greengenes database and a custom NCBI 16 S rRNA gene sequence database. Of these OTUs 21 were found to be chimeric and thus culled. This polished dataset was then used to compare the taxonomic makeup with other stromatolite data available in the NCBI database3,5,7,10,22,23,56,57.

Macroinvertebrate sampling

Invertebrate sampling was conducted in August 2016. Six samples were taken at points 0–5 m from the tape along the transect line. An additional three opportunistic samples targeting the surrounding streams and a dense patch of live and dead snails were also taken. Three sampling methods (core, sweep and hand collection) were applied, depending on the substrate conditions. Core sampling consisted of applying a 50 ml syringe (top removed to form a cylinder) to the substrate within a 20 cm2 quadrat to extract 150 ml of sandy substrate; the contents were then immediately placed into a jar and preserved in 70% ethanol. Sweep netting was used in wetter areas where core samples could not be retained. An aquarium net of 15 × 10 cm and 300 µm mesh size was used to collect substrate samples by placing the net downstream of an area 40 × 40 cm disturbed by hand to a depth of 1 cm. Finally, the hand collection method was used to collect a cross section of observable snails at various locations across the mound.

Samples were all preserved and sorted to family (or genus) under a dissection microscope. Mollusca were further identified to species using microscopy and dissection, current keys and descriptions45,46.

Data availability

Representative OTU sequence data were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers KX903306-KX904341.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service for permission to sample; Associate Professor Alastair Richardson (Bookend Trust) for confirming amphipod identifications; Robert Wiltshire (University of Tasmania) for photographic assistance; Andrew Moy (Australian Antarctic Division, Hobart) for water isotope analysis; Paul Boland (Boland Surveying) for geodetic services; Dave Paton (Helicopter Resources Pty Ltd) for expert piloting.

Author Contributions

R.S.E., B.C.P. and M.C. coordinated the field work, sampling and laboratory analyses; C.S. mapped the geology; J.P.B. was responsible for RNA interpretation; K.R. sampled macroinvertebrates, and K.R. and L.A.B. identified species. B.C.P and R.S.E. equally led manuscript writing, and all authors contributed to the interpretation of data and gave final approval for submission and publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15507-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Riding R. The term stromatolite: towards an essential definition. Lethaia. 1999;32:321–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00550.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riding R. Microbial carbonates: the geological record of calcified bacterial-algal mats and biofilms. Sedimentology. 2000;47:179–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3091.2000.00003.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns BP, Goh F, Allen M, Neilan BA. Microbial diversity of extant stromatolites in the hypersaline marine environment of Shark Bay, Australia. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;6:1096–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutman, A. P., Bennett, V. C., Friend, C. R. L., Van Kranendonk, M. J. & Chivas, A. R. Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Papineau D, Walker JJ, Mojzsis SJ, Pace NR. Composition and structure of microbial communities from stromatolites of Hamelin Pool in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4822–4832. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4822-4832.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagès A, et al. Characterizing microbial communities and processes in a modern stromatolite (Shark Bay) using lipid biomarkers and two-dimensional distributions of porewater solutes. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:2458–2474. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgartner LK, et al. Microbial diversity in modern marine stromatolites, Highborne Cay, Bahamas. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;11:2710–2719. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid RP, Visscher PT, Decho AW, Stolz JF, Bebout BM. The role of microbes in accretion, lamination and early lithification of modern marine stromatolites. Nature. 2000;406:989–992. doi: 10.1038/35023158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djokic T, Van Kranendonk MJ, Campbell KA, Walter MR, Ward CR. Earliest signs of life on land preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga hot spring deposits. Nature Comm. 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-016-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster JS, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of cyanobacterial diversity in the stromatolites of Highborne Cay, Bahamas. ISME J. 2009;3:573–587. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul VG, Wronkiewicz DJ, Mormile MR, Foster JS. Mineralogy and microbial diversity of the microbialites in the hypersaline Storr’s Lake, the Bahamas. Astrobiology. 2016;16:282–300. doi: 10.1089/ast.2015.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riding, R. Microbialites, stromatolites, and thrombolites. Encyclopedia of Geobiology, Encyclopedia of Earth Science Series, Springer, Heidelberg, 635–654 (2011).

- 13.Mata SA, Bottjer DJ. Microbes and mass extinctions: paleoenvironmental distribution of microbialites during times of biotic crisis. Geobiology. 2012;10:3–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2011.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farías ME, et al. The discovery of stromatolites developing at 3570 m above sea level in a high-altitude volcanic Lake Socompa, Argentinean Andes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riding R. Microbial carbonate abundance compared with fluctuations in metazoan diversity over geological time. Sediment. Geol. 2006;185:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2005.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rishworth GM, Perissinotto R, Bird MS. Coexisting living stromatolites and infaunal metazoans. Oecologia. 2016;182:539–545. doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edgcomb VP, et al. Active eukaryotes in microbialites from Highborne Cay, Bahamas, and Hamelin Pool (Shark Bay), Australia. ISME J. 2014;8:418–429. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coman C, et al. Structure, mineralogy, and microbial diversity of geothermal spring microbialites associated with a deep oil drilling in Romania. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:253. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noffke N, Awramik SM. Stromatolites and MISS – Differences between relatives. Gsa Today. 2013;23:4–9. doi: 10.1130/GSATG187A.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider D, Arp G, Reimer A, Reitner J, Daniel R. Phylogenetic analysis of a microbialite-forming microbial mat from a hypersaline lake of the Kiritimati Atoll, Central Pacific. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perissinotto R, et al. Tufa stromatolite ecosystems on the South African south coast. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2014;110:1–8. doi: 10.1590/sajs.2014/20140011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos F, et al. Bacterial diversity in dry modern freshwater stromatolites from Ruidera Pools Natural Park, Spain. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;33:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan OW, Bugler-Lacap DC, Biddle JF. Phylogenetic diversity of a microbialite reef in a cold alkaline freshwater lake. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014;60:391–398. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2014-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bissett A, et al. Microbial mediation of stromatolite formation in karst-water creeks. Limnol. Oceangr. 2008;53:1159–1168. doi: 10.4319/lo.2008.53.3.1159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freytet P, Plet A. Modern freshwater microbial carbonates: the Phormidium stromatolites (tufa-travertine) of southeastern Burgundy (Paris Basin, France) Facies. 1996;34:219–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02546166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurgate ME. The stromatolites of the cenote lakes of the lower south east of South Australia. Helictite. 1996;34:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiraishi F, Okumura T, Takahashi Y, Kano A. Influence of microbial photosynthesis on tufa stromatolite formation and ambient water chemistry, SW Japan. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2010;74:5289–5304. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown MJ, Crowden RK, Jarman SJ. Vegetation of an alkaline pan - acidic peat mosaic in the Hardwood River Valley, Tasmania. Australian Journal of Ecology. 1982;7:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1982.tb01295.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckney RT, Tyler PA. Chemistry of Tasmanian inland waters. Int, Rev. Hydrobiol. 1973;58:61–78. doi: 10.1002/iroh.19730580105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin BJ, Preiss WV. The significance and provenance of stromatolitic clasts in a probable Late Precambrian diamictite in northwestern Tasmania. Papers & Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania. 1976;10:111–127. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arvidson RS, Mackenzie FT. The dolomite problem: Control of precipitation kinetics by temperature and saturation state. Am. J. Sci. 1999;299:257–288. doi: 10.2475/ajs.299.4.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiner S, Levi-Kalisman Y, Raz S, Addadi L. Biologically formed amorphous calcium carbonate. Connect. Tissue Res. 2003;44:214–218. doi: 10.1080/03008200390181681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford TD, Pedley HM. A review of tufa and travertine deposits of the world. Earth-Science Reviews. 1996;41:117–175. doi: 10.1016/S0012-8252(96)00030-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redfield E, Barns SM, Belnap J, Daane LL, Kuske CR. Comparative diversity and composition of cyanobacteria in three predominant soil crusts of the Colorado Plateau. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002;40:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eiler A, Bertilsson S. Composition of freshwater bacterial communities associated with cyanobacterial blooms in four Swedish lakes. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;6:1228–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loza V, Perona E, Mateo P. Molecular fingerprinting of cyanobacteria from river biofilms as a water quality monitoring tool. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:1459–1472. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03351-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhan J, Sun Q. Diversity of free-living nitrogen-fixing microorganisms in wastelands of copper mine tailings during the process of natural ecological restoration. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2011;23:476–487. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun L, et al. Isolation and characterization of Flexilinea flocculi gen. nov., sp. nov., a filamentous anaerobic bacterium belonging to the class Anaerolineae in the phylum Chloroflexi. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:988–998. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomczyk-Za k, et al. Bacteria diversity and arsenic mobilization in rock biofilm from an ancient gold and arsenic mine. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;461–462:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Headd B, Engel AS. Biogeographic congruency among bacterial communities from terrestrial sulfidic springs. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:473. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster, J. S. & Green, S. Microbial diversity in modern stromatolites in Stromatolites: Interaction of microbes with sediments Vol. 18 Cellular origin, life in extreme habitats and astrobiology 18 (eds Tewari, V. C. & Seckbach, J.) 383–405 (Springer, 2011).

- 42.Pajares S, Souca V, Eguiarte LE. Multivariate and phylogenetic analyses assessing the response of bacterial mat communities from an ancient oligotrophic aquatic ecosystem to different scenarios of long-term environmental disturbance. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham LE, et al. Lacustrine Nostoc (Nostocales) and associated microbiome generate a new type of modern clotted microbialite. J. Phycol. 2014;50:280–291. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fenwick GD. Ringanui, a new genus of stygobitic amphipod from New Zealand (Amphipoda: Gammaridea: Paraleptamphopidae) Zootaxa. 2006;1148:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ponder WF, Clark GA, Miller AC, Toluzzi A. On a major radiation of freshwater snails in Tasmania and eastern Victoria: a preliminary overview of the Beddomeia group (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae) Invertebrate Taxonomy. 1993;7:501–750. doi: 10.1071/IT9930501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark, S. A., Miller, A. C. & Ponder, W. F. Revision of the snail genus Austropyrgus (Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae): a morphostatic radiation of freshwater gastropods in southeastern Australia. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 28 (2003).

- 47.Schössow M, Hartmut A, Becker G. Response of gastropod grazers to food conditions, current velocity, and substratum roughness. Limnologica – Ecology and Management of Inland Waters. 2016;58:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2016.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters SE, Husson JM, Wilcots J. The rise and fall of stromatolites in shallow marine environments. Geology. 2017;G38931:1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rishworth, G. M. et al. Non-reliance of metazoans on stromatolite-forming microbial mats as a food resource. Nature Sci. Rep. 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Schloss PD, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaspar JM, Thomas WK. Assessing the consequences of denoising marker-based metagenomic data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wright ES, Yilmaz LS, Noguera DR. DECIPHER, a search-based approach to chimera identification for 16S rRNA sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:717–725. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06516-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caporaso JG, et al. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:266–267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goh F, et al. Determining the specific microbial populations and their spatial distribution within the stromatolite ecosystem of Shark Bay. ISME J. 2008;3:383–396. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havemann SA, Foster JS. Comparative characterization of the microbial diversities of an artificial microbialite model and a natural stromatolite. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:7410–7421. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01710-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Representative OTU sequence data were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers KX903306-KX904341.