Abstract

Transcription factor MEF2C regulates multiple genes linked to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and human MEF2C haploinsufficiency results in ASD, intellectual disability, and epilepsy. However, molecular mechanisms underlying MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome remain poorly understood. Here we report that Mef2c +/−(Mef2c-het) mice exhibit behavioral deficits resembling those of human patients. Gene expression analyses on brains from these mice show changes in genes associated with neurogenesis, synapse formation, and neuronal cell death. Accordingly, Mef2c-het mice exhibit decreased neurogenesis, enhanced neuronal apoptosis, and an increased ratio of excitatory to inhibitory (E/I) neurotransmission. Importantly, neurobehavioral deficits, E/I imbalance, and histological damage are all ameliorated by treatment with NitroSynapsin, a new dual-action compound related to the FDA-approved drug memantine, representing an uncompetitive/fast off-rate antagonist of NMDA-type glutamate receptors. These results suggest that MEF2C haploinsufficiency leads to abnormal brain development, E/I imbalance, and neurobehavioral dysfunction, which may be mitigated by pharmacological intervention.

Human MEF2C haploinsufficiency results in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), but it is unclear if the same is true in mice. Here, the authors show that Mef2c +/−mice have behavioral defects and neuronal abnormalities similar to ASD, and symptoms can be ameliorated with the new drug, NitroSynapsin.

Introduction

Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) transcription factors belong to the MADS (MCM1-agamous-deficiens-serum response factor) gene family1,2. In brain, MEF2C is critical for neuronal differentiation, synaptic formation, and neuronal survival3–7. Recent gene expression analyses and genetic linkage experiments identified MEF2C as a convergent point in multiple regulatory pathways involved in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)8,9. We previously showed that conditional knockout of Mef2c in nestin-expressing neural progenitor cells produced mice with impaired electrophysiological network properties and behavioral deficits reminiscent of Rett syndrome, a neurological disorder related to autism spectrum disorder (ASD)10. Subsequent to our study, human geneticists mapped the overlapping regions of chromosome 5q14.3q15 microdeletions that cause neurological deficits in children, and identified MEF2C haploinsufficiency as the cause. These patients exhibit signs and symptoms that include ASD, intellectual disability (ID), poor reciprocal behavior, lack of speech, stereotyped and repetitive behavior, and epilepsy11–22. The disorders caused by MEF2C haploinsufficiency have been collectively termed MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome (MCHS)22. In addition, multiple MEF2 target genes have been identified as autism-related genes in human pedigrees with shared ancestry23.

One emerging mechanism for ASD pathogenesis is excitation/inhibition (E/I) imbalance in synaptic transmission, which may occur via several molecular pathways24–27. In MeCP2-deficient mice, a model of human Rett syndrome, impaired synaptic function and E/I imbalance lead to hyperexcitability in the hippocampus28. Furthermore, MeCP2 has been shown to influence the expression of MEF2C29. Interestingly, the N-methyl-d-aspartate-type glutamate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist memantine has been reported to improve hippocampal E/I imbalance in experimental models30. Memantine is an uncompetitive/fast off-rate NMDAR antagonist, which predominantly inhibits extrasynaptic receptors31; it has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Administration (EMA) for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease31. However, to date, despite initial enthusiasm32, memantine has not been found to be effective for ASD in advanced human clinical trials, and in fact, at least one of these trials has been terminated due to lack of efficacy33. Thus, it appears that improved drugs may be needed if NMDAR antagonism is going to prove worthwhile for the treatment of ASD and related conditions. Along these lines, we recently synthesized an improved series of drugs based on dual memantine-like action and redox-based inhibition of extrasynaptic NMDARs; initially, these compounds were called “NitroMemantines,” but recently the lead compound, YQW-036/NMI-6979, was designated NitroSynapsin because of its ability to restore synaptic number and function in the face of multiple insults34–36.

In the present study, we develop Mef2c +/− (Mef2c-het) mice as a model for the human MEF2C haploinsufficiency form of ASD. We show that Mef2c-het mice display neuronal and synaptic abnormalities, decreased inhibitory and increased excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, suppressed long-term potentiation (LTP), and MCHS-like behavioral phenotypes. Importantly, we found that nearly all of these phenotypes are rescued or mitigated by chronic treatment with NitroSynapsin. This study therefore suggests that MEF2C haploinsufficiency induces neuronal and synaptic abnormalities that play an important role in ASD/MCHS-like behavioral phenotypes, which can be improved with pharmacological treatment.

Results

Mef2c-hets display autistic behavior and reduced viability

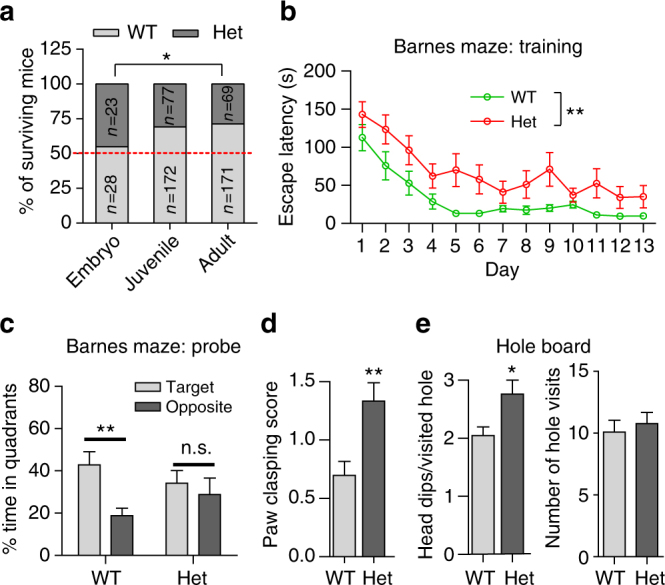

MEF2C protein expression is significantly lower (P < 0.01) in Mef2c-het mice than in wild-type (WT) littermates (Supplementary Fig. 1), and we observed a significant number of early deaths in theMef2c-het mice (Fig. 1a).We counted the number of viable animals from crosses between WT and Mef2c-het parents. While the number of WT and Mef2c-het offspring were approximately equal on embryonic day (E)18 (28 vs. 23, respectively), the ratio of surviving Mef2c-het to WT mice was 44% and 40% by postnatal day (P)21 and 90, respectively. The difference between survival at E18 and adult was significant (P < 0.05 by χ 2). In addition to reduced viability, Mef2c-het mice that survived to 3 months of age exhibited a decrease (~14%) in body weight compared to their WT counterparts (31.9 ± 1.0 g for WT vs. 27.4 ± 0.8 g for Mef2c-het; P < 0.001 by Student’s t test).

Fig. 1.

Mef2c-het mice display MCHS-like phenotypes. a Mef2c-het mice die prematurely. The number of Mef2c-het compared to WT mice was nearly equal at E18, but ~45% that of WT by adulthood (~3 months) (*P < 0.05 by χ 2). b, c Impaired spatial learned and memory in the Barnes maze of Mef2c-het mice during training (b) and on subsequent probe tests (c). d, e Increased paw clasping (d) and repetitive head dipping (e) of Mef2c-het mice in hole-board exploration. Data are mean ± s.e.m.; n = 9–11 mice per genotype in b, c, and e; n = 30 (WT) and 21 (het) in d; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test (c–e) or ANOVA (b). n.s. not significant

To determine whether adult Mef2c-het mice display MCHS-like phenotypes, we performed behavioral tests on male Mef2c-het mice and their WT littermates (≥3 months of age). Similar to human patients showing cognitive impairment, Mef2c-het mice performed poorly in the Barnes maze, a test that measures spatial learning and memory function. Mef2c-het mice took a significantly longer time to find the escape tunnel during training sessions (Fig. 1b). In subsequent probe tests,WT mice, but not Mef2c-het mice, showed a preference for the target quadrant compared to the opposite quadrant (Fig. 1c), suggesting impaired spatial memory in the Mef2c-het mice. Mef2c-het mice manifested stereotypies, including abnormal paw-clasping behavior10,37 (Fig. 1d) and repetitive head dipping on the hole-board exploration test38 (Fig. 1e). Taken together, these results suggest that Mef2c-het mice display a wide range of MCHS-like phenotypes and thus represent a potentially useful animal model for MCHS.

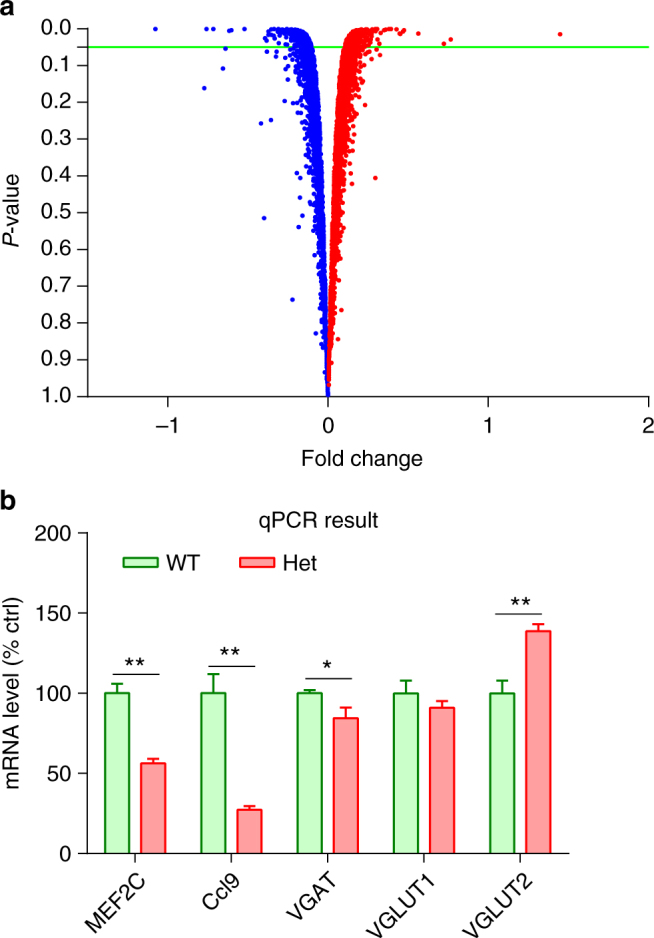

Downregulated neurogenesis and synaptic genes in Mef2c-hets

To identify molecular pathways underlying the pathogenesis of MCHS, we examined gene expression of Mef2c-het mice vs. WT littermates by microarray. We identified a total of 783 genes whose expression levels were significantly altered in the hippocampus, including 394 downregulated and 389 upregulated in Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 2a, above green line; Supplementary Data 1).With these data, using NextBio pathway analysis, we identified the top neuronal biogroups that were downregulated by Mef2c haploinsufficiency in mice, including biogroups for neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic function (Table 1). Concurrently, the biogroup for regulation of neuronal cell death was upregulated (Table 1). We confirmed the microarray results by quantitative PCR using RNAs extracted from 3-month-old mice (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the NextBio analysis, we found that the messenger RNA (mRNA) level of vesicular γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter VGAT (encoded by Slc32a1), representing an inhibitory presynaptic marker, was significantly decreased in Mef2c-het mice. We also examined the mRNA level of vesicular glutamate transporters 1/2 (VGLUT1/2), representing excitatory synaptic markers, and found that the level of VGLUT2, but not VGLUT1, was significantly increased in Mef2c-het mice. These results suggest possible dysfunction of both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in these mice.

Fig. 2.

Downregulation of neurogenic and synaptic genes in Mef2c-het mice by microarray analysis. a Volcano plot shows RNA expression profiling in P30 Mef2c-het and WT hippocampus (red = up, blue = down, P < 0.05 indicated by green line). b Graph of qPCR experiments showing expression levels of mRNA (relative to 18S) in Mef2c-het mice as percentage of WT control (% ctrl; n = 4 per group). Data are mean ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test

Table 1.

Pathway analysis of all genes with altered expression in Mef2c-het mice

| Dysregulated biogroups in Mef2c-het mice | # of genes dysregulated | Direction | Score | P-value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurogenesis | 33 | Down | 34.31 | 1.30E−15 | GO |

| Neuron differentiation | 23 | Down | 27.51 | 1.10E−12 | GO |

| Synapse | 18 | Down | 24.04 | 3.60E−11 | GO |

| Regulation of neuron death | 5 | Up | 9.29 | 9.30E−05 | GO |

Pathway-enrichment analysis was performed using NextBio and gene-ontology (GO-term) filtering

Excitatory/inhibitoryneuronal deficits in Mef2c-hets

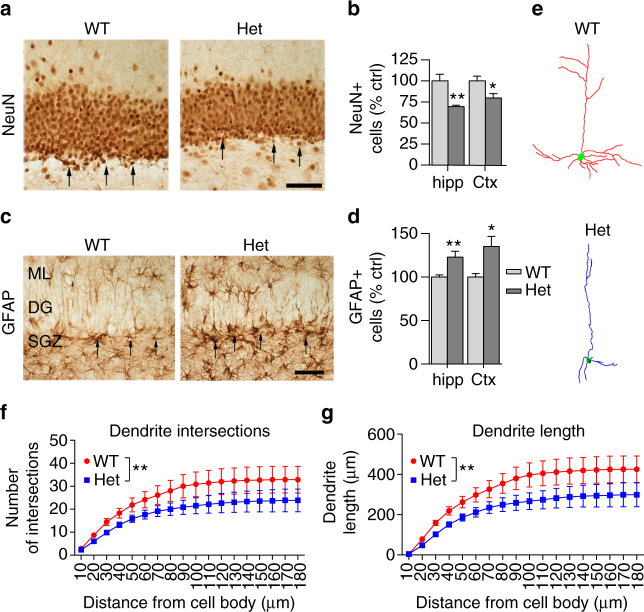

In histological experiments using the optical dissector as an unbiased stereological counting method, the total number of NeuN+ cells (i.e., neurons) was significantly decreased in Mef2c-het mice compared to WT in the hippocampus (69.5 ± 1.6% of WT control value, P < 0.01 by Student’s t test) and frontal cortex (79.8 ± 5.1% of WT control, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast to NeuN+ cells, the number of glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP)+ cells was significantly increased in Mef2c-het mice compared to WT in both the hippocampus (123.0 ± 6.8% of WT control, P < 0.01) and frontal cortex (135.16 ± 11.70% of WT control, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Mef2c-het mice exhibit abnormal neuronal properties. a Immunohistochemistry showing NeuN+ cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) of WT and Mef2c-het mice. b Quantification showing decreased NeuN+ cell counts in hippocampus (hipp) and cortex (Ctx) in Mef2c-het mice relative to WT. Hippocampal measurements were obtained on granule cells in the molecular layer of the DG, and the cortical measurement on frontal lobe layers IV and V. c, d Increased number of GFAP+ cells consistent with astrocytosis in Mef2c-het mice. e Neurolucida drawing of representative dendrites visualized by Golgi staining in V1 (primary visual cortex), M2ML (secondary visual cortex mediolateral area), and LPtA (lateral parietal association cortex) of the visual cortex of WT and Mef2c-het mice. f, g Summary graphs of Sholl analysis showing reduction in cumulative number of dendritic intersections (f) and dendritic lengths (g) in Mef2c-het neurons. Scale bar: 50 µm. Data are mean ± s.e.m.; n = 4 per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test in a–d and ANOVA in f, g

We next performed Golgi staining in both Mef2c-het and WT brains to determine dendritic branching patterns of pyramidal cells in layer V of the cerebrocortex using Neurolucida software on three-dimensional (3D) montage images (Fig. 3e). Our Sholl analyses39 indicated that the dendritic complexity of Mef2c-het neurons was significantly reduced, as demonstrated by decreased dendritic interactions (Fig. 3f) and decreased total dendritic lengths (Fig. 3g).

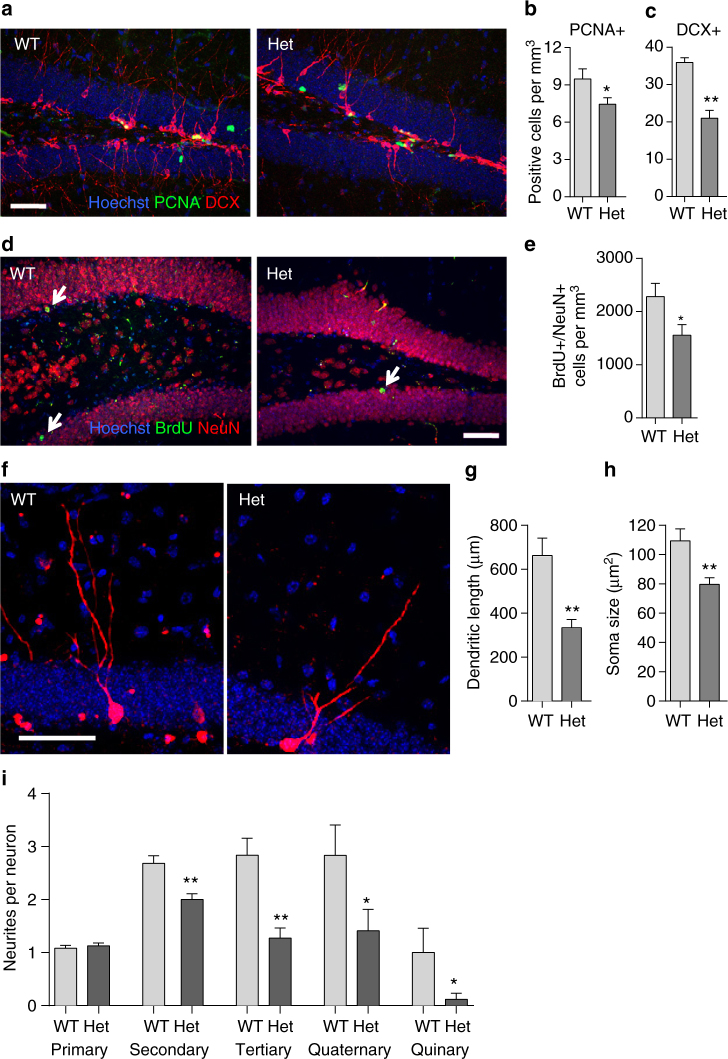

To further account for the decrease in neuronal number, in addition to the known reduction in embryonic neurogenesis mediated by MEF2C deficiency10, we characterized adult neurogenesis in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (DG) of 2–3 month-old Mef2c-het mice and found a decrease in both the number of proliferating cells (PCNA+, Fig. 4a, b) and developing neurons (DCX+, Fig. 4a, c). The number of BrdU-labeled NeuN+ cells was also reduced in the DG (Fig. 4d, e). These results suggest that reduced adult neurogenesis in Mef2c-het mice contributes to the reduction in neurons. In addition, the development and complexity of newly formed neurons, visualized via retroviral-mediated gene transduction of mCherry, were also decreased in the Mef2c-het DG, as indicated by decreased somal size and dendritic length (Fig. 4f–i). Therefore, Mef2c haploinsufficiency results in decreased neuronal number, impaired adult neurogenesis, and decreased dendritic complexity in mice.

Fig. 4.

Mef2c-het mice exhibit abnormal adult neurogenesis. a Confocal images showing PCNA (green) and DCX (red) double staining in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the DG in 8-week-old WT and Mef2c-het mice. b, c Quantification of PCNA+ and DCX+ cells revealed reduction in the number of proliferating cells (b) and developing neurons (c) in Mef2c-het DG. d BrdU (green) and NeuN (red) double staining 4 weeks after BrdU injection in 8-week-old WT and Mef2c-het mice revealed newly born DG neurons (arrows: BrdU+/NeuN+). e Reduction in BrdU+/NeuN+ cells in Mef2c-het DG; n = 4 mice per genotype in a–e. f Examples of morphological development of neurons born in adult Mef2c-het and WT mice. Dividing cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) were labeled with mCherry via retroviral-mediated gene transduction. Mice were killed 4 weeks later. g Quantification of total dendritic length of 4-week-old neurons revealed reduced dendritic length in Mef2c-het mice (n = 17) compared to WT mice (n = 12). h Quantification showed reduced somal size in Mef2c-het mice (n = 71) compared to WT mice (n = 28). i Quantification of neurite number showed normal number of primary neurites (n WT = 25, n Het = 55), but reduced number of secondary (n WT = 25, n Het = 55), tertiary (n WT = 25, n Het = 55), quaternary (n WT = 12, n Het = 17), and quinary (n WT = 12, n Het = 17) neurites of 4-week-old neurons in Mef2c-het compared to WT brain. Section thickness: 40 µm. Scale bar: 50 µm. Values are mean ± s.e.m., *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t test

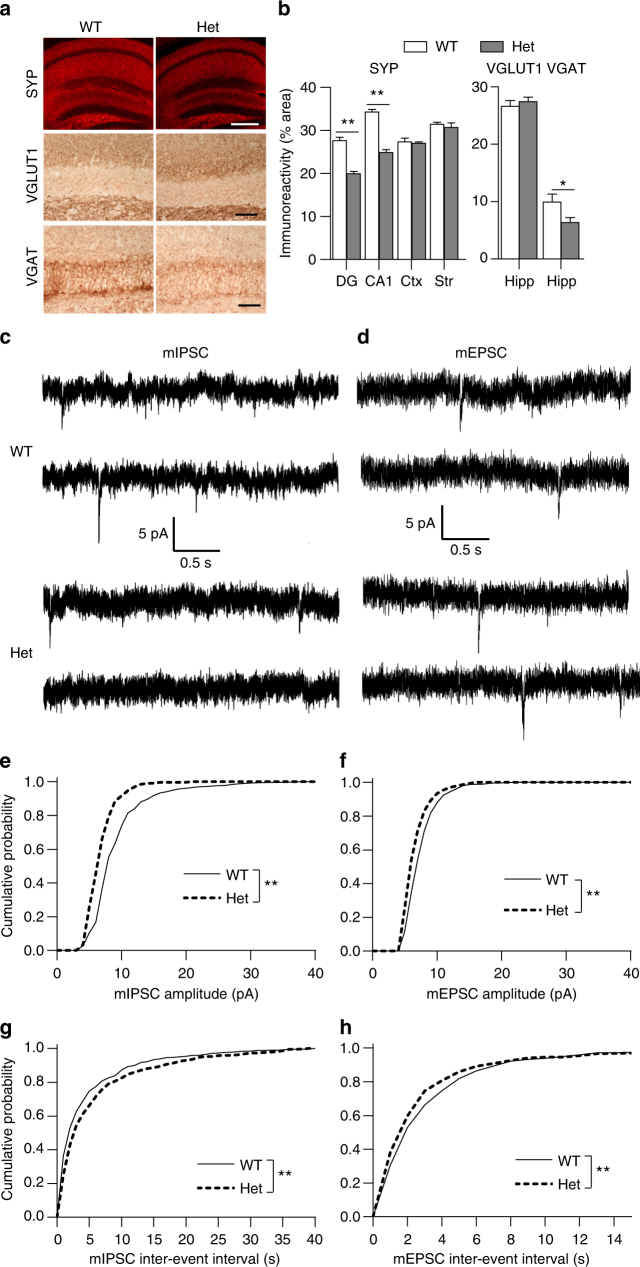

We subsequently examined synapses in Mef2c-het mice. Consistent with the microarray analysis predicting an alteration in synaptic proteins, quantitative confocal immunohistochemistry showed that expression of synaptophysin (SYP), a presynaptic marker, was significantly decreased in the hippocampus of Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 5a, b). To better define the synaptic deficit, we examined expression levels of the predominant excitatory synaptic protein VGLUT1 and the inhibitory synaptic protein VGAT by quantitative confocal immunohistochemistry in the hippocampus (Fig. 5a). We found that expression of VGAT, but not VGLUT1, was significantly decreased in Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 5b). In addition, we performed immunoblot experiments on hippocampal synaptosome-enriched lysates and found that the levels of SYP and GAD65 (another inhibitory neuronal marker), but not VGLUT1, were downregulated in Mef2c-het mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The ratio of VGLUT1 (excitatory neurons) to GAD65 (inhibitory neurons) was significantly increased in Mef2c-het mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b), a sign of E/I imbalance. Moreover, in contrast to VGLUT1 and in line with our mRNA findings, VGLUT2 protein, which is normally expressed only at very low levels in adult hippocampus40,41, was significantly upregulated in Mef2c-het vs. WT (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Taken together, these findings indicate aberrant excitatory and inhibitory synaptic protein expression in Mef2c-het hippocampus.

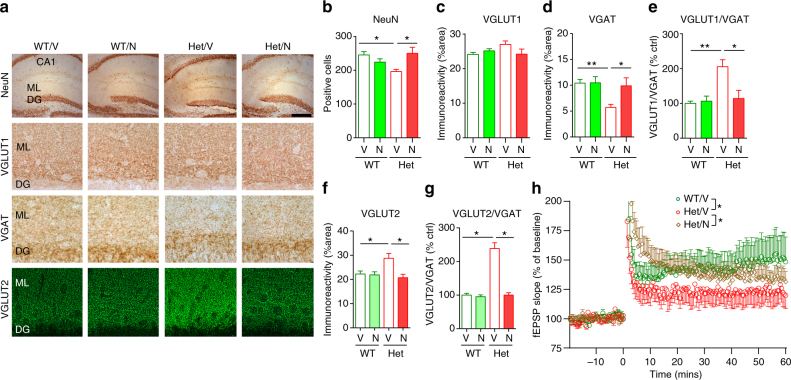

Fig. 5.

Mef2c-het mice exhibit altered synaptic properties and E/I imbalance in synaptic neurotransmission. a Immunohistochemistry of synaptophysin (SYP), VGLUT1, and VGAT in WT and Mef2c-het hippocampus. Scale bars: 500 µm (top panel), 50 µm (middle and bottom panels). b Reduced immunoreactivity of SYP in the dentate gyrus (DG) and CA1 regions of Mef2c-het hippocampus but not cortex (Ctx) or striatum (str, left). DG measurements were performed in the molecular layer, CA1 in the pyramidal cell layer, Ctx in frontal cortical layers IV and VI, and str in the putamen at the level of the nucleus accumbens. Reduced expression of VGAT but not VGLUT1 in Mef2c-het hippocampus (right). Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test. c, d Representative traces of mIPSCs (c) and mEPSCs (d) from slice recordings of DG neurons of WT and Mef2c-het mice. e–h Cumulative plots of mIPSC and mEPSC amplitude and inter-event intervals. n = 7–9 per genotype; **P < 0.01 by two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test

To determine whether these alterations in E/I marker expression are accompanied by abnormalities in functional synaptic transmission, we recorded spontaneous miniature excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs/mIPSCs) from hippocampal slices of Mef2c-het and WT mice. From the theory of quantal release, a change in miniature frequency reflects a change in presynaptic neurotransmitter release or in the number of synapses, while a change in miniature amplitude is thought to represent a change in postsynaptic function, e.g., the number of post synaptic receptors. Mef2c-het mice displayed decreased mIPSC frequency (manifested as increased inter-event interval in Fig. 5c, g), in line with the overall reduction in presynaptic VGAT, dendrites and synapses. Reduced mIPSC amplitude was also observed (Fig. 5c, e), possibly reflecting the fact that MEF2 levels are known to correlate with the expression of specific GABA receptor subunits42,43. Interestingly, these mice also showed an increase in mEPSC frequency (manifested as decreased inter-event interval, Fig. 5d, f), similar to a previous report of increased mEPSC frequency in brain-specific Mef2c-KO mice7. This result is also consistent with our finding of increased expression of presynaptic VGLUT2 in theMef2c-het hippocampus. The slight reduction in mEPSC amplitude (Fig. 5d, h) may reflect the fact that MEF2 transcriptionally normally upregulates glutamate receptor expression44. The overall change in mIPSCs and mEPSCs would be expected to result in an elevated E/I ratio in Mef2c-het mice. Indeed, as determined by the quotient of mean mEPSC to mIPSC values, Mef2c-het mice manifested a 116.2% increase in the E/I frequency ratio and a 25.7% increase in E/I amplitude ratio compared to WT mice, confirming the existence of functional E/I imbalance.

To determine if these neuronal and synaptic defects have a deleterious effect on synaptic plasticity and neuronal circuitry, we recorded hippocampal LTP. Mef2c-het mice exhibited reduced LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Paired pulse facilitation (PPF) represents short-term enhancement of presynaptic function in response to the second of two paired stimuli caused by residual Ca2+ in the presynaptic terminal after the first stimulation. For example, decreased PPF is associated with increased probability of neurotransmitter release. We observed a statistical decrease in PPF in Mef2c-het vs. WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 3b), consistent with our observed small increase in mEPSC frequency (Fig. 5d, f). Collectively, our results show that Mef2c-het mice manifest a reduced number of neurons, accompanied by synaptic deficits with decreased inhibitory and increased excitatory synaptic neurotransmission, thus leading to E/I imbalance.

NitroSynapsin rescues autistic behaviors in Mef2c-het mice

In other mouse models of ASD, decreased GABAergic neurotransmission has been reported to contribute to E/I imbalance, leading to autistic-like social and cognitive deficits that parallel those found in humanautism27. Therefore, it is possible that the autistic/MCHS-like behavioral deficits in Mef2c-het mice may also be triggered, in part, by reduced inhibitory neurotransmission, as well as by the increased excitatory synaptic activity found here. In this regard, aminoadamantane drugs like the FDA-approved drug memantine have been reported to restore altered E/I balance30. Thus, we reasoned that chronic treatment with NitroSynapsin34–36, an aminoadamantane nitrate displaying increased efficacy at the NMDAR compared to memantine, might mitigate MCHS-like phenotypes in Mef2c-het mice via its ability to restore E/I balance. To test this hypothesis, we treated male Mef2c-het or WT mice with NitroSynapsin or PBS vehicle for 3 months. We then performed behavioral, electrophysiological, and histological analyses to determine the effects of this drug. Importantly, NitroSynapsin treatment of WT mice showed no effects on the Morris water maze, EPSCs, or LTP36.

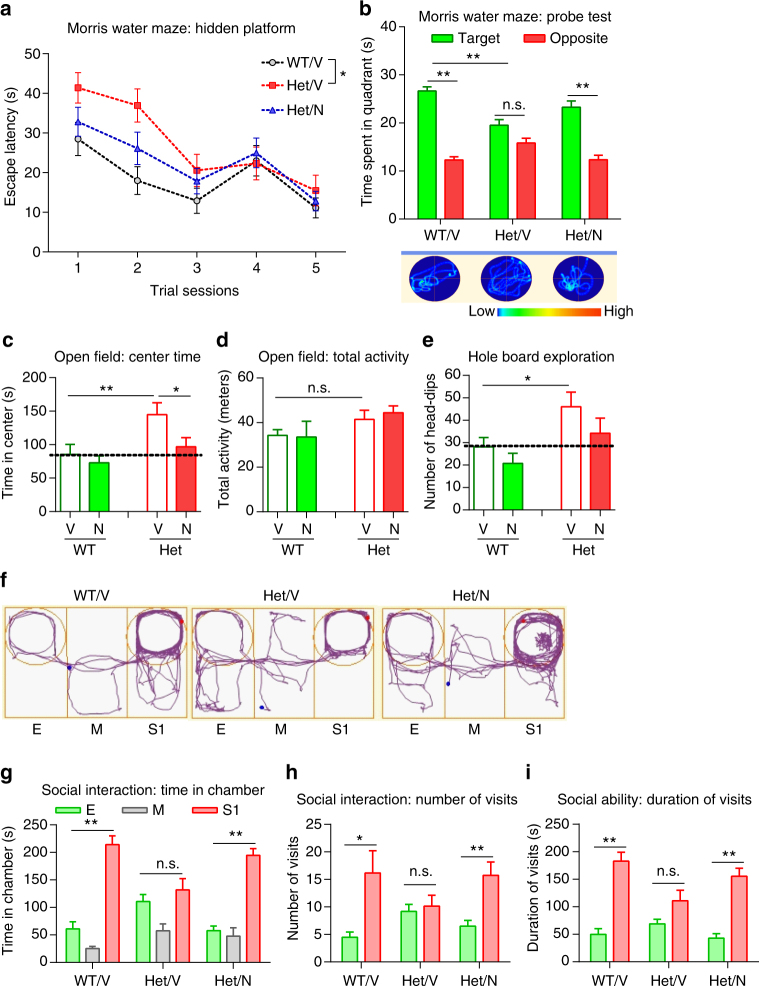

Neurobehavioral tests were used to determine whether treatment of Mef2c-het mice with NitroSynapsin could rescue autistic/MCHS-like behavioral phenotypes. We first performed the Morris water maze to test the effecton spatial learning and memory (Fig. 6a, b). During hidden platform training sessions, vehicle-treated Mef2c-het (Het/V) mice showed impaired spatial learning in the first 2 days by taking longer to find the hidden platform than vehicle-treated WT (WT/V) mice (Fig. 6a). However, Mef2c-het mice treated with NitroSynapsin (Het/N) showed improved performance relative to vehicle during these tests. This improvement cannot be attributed to an increase in swimming speed per se, neither Mef2c heterozygosity nor NitroSynapsin treatment affected swimming speed (Supplementary Fig. 4). Twenty-four hours after all groups of mice reached the criteria (20 s to find the hidden platform), we performed probe tests to examine memory retention. As shown in Fig. 6b, WT/V mice displayed normal memory retention by spending a significantly longer time in the target quadrant, where the hidden platform was previously located. In contrast, Het/V mice displayed impaired memory by not showing a preference to the target quadrant over the opposite quadrant. Interestingly, Het/N mice spent significantly more time in the target quadrant than in the opposite quadrant, suggesting that NitroSynapsin treatment normalized memory function (Fig. 6a, b). We next performed an open field test, a 30-min test to assay general locomotor activity. Het/V mice showed enhanced center activity (Fig. 6c), but not total activity (Fig. 6d).This abnormal behavior was rescued by chronic treatment with NitroSynapsin. The drug also corrected the abnormal repetitive behavior of increased head dipping of Mef2c-het mice in the hole-board exploration test (Fig. 6e). Finally, we performed a social interaction behavioral test. WT/V mice spent significantly more time in a chamber with a stranger mouse 1 (S1) than in a chamber with a similar but empty cage (E). However, Het/V mice showed no preference for time spent in either chamber (Fig. 6f, g), a sign of impaired social ability. In addition, Het/V mice paid significantly fewer visits to S1 and for shorter times per visit than WT/V mice(Fig. 6h, i). Treatment with NitroSynapsin improved this abnormal social behavior. Importantly, initial feasibility experiments, in which we had treated Mef2c het mice with equimolar memantine or NitroSynapsin in a head-to-head comparison, demonstrated the superiority of NitroSynapsin in these behavioral paradigms (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In addition, NitroSynapsin treatment did not significantly alter the social behavior of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

NitroSynapsin rescues MCHS-like phenotypes in Mef2c-het mice. a Latency of finding hidden platform during training sessions in the Morris water maze. b In the probe test, vehicle-treated Mef2c-het mice (Het/V) showed no preference between target and opposite quadrants, suggesting impaired memory. Treatment with NitroSynapsin (N) rescued this effect (Het/N). Representative swim patterns shown at bottom. c, d In the open field test, Het/V mice exhibited increased center time that was rescued by treatment with N (c). In contrast, Het/V mice displayed normal total activity (d). e Het/V mice displayed increased head-dips per hole, suggesting repetitive behavior. Treatment with N rescued. f–i N treatment rescued aberrant social ability in Mef2c-het mice. f Representative traces of mouse movement in the three-chamber social ability test. g–i Mef2c-het mice (Het/V) exhibit abnormalities in social interaction measured by time spent in each chamber (g), number of visits (h), and duration of visits (i) to E (empty) or S1 (stranger mouse 1) chambers. N treatment ameliorated this deficit (Het/N). Data are mean ± s.e.m. n = 7–9 per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by ANOVA. M middle chamber

Taken together, these results show that chronic treatment of Mef2c-het mice with NitroSynapsin significantly improved cognitive deficits, repetitive behavior, impaired social interactions, and possibly altered anxiety. Of note, Mef2c-het mice did not exhibit aberrant motor behaviors except for paw clasping (Supplementary Fig. 7a–e). However, NitroSynapsin treatment did not improve the paw clasping phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 7f).

NitroSynapsin effect on E/I neuronal markers and LTP

We performed immunohistochemistry to determine the effects of drug treatment on neuronal loss and altered expression of VGAT or VGLUT2 in the hippocampus of Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 7a–g). Specifically, monitored by stereology using the optical dissector method, the total number of NeuN+ cells in the hippocampus of Het/N mice was significantly greater than in Het/V mice (Fig. 7b), consistent with the efficacy of NitroSynapsin in the prior behavioral experiments. In addition, in our initial feasibility experiments, we found a significantly greater effect of NitroSynapsin over memantine on NeuN+ cell counts (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Fig. 7.

NitroSynapsin rescues abnormal neuronal and synaptic properties in Mef2c-het mice. a Immunohistochemical images of NeuN, VGLUT1, VGAT, and VGLUT2 in the molecular layer (ML) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of WT and Mef2c-het mice treated with vehicle (V) or NitroSynapsin (N). Scale bars: 500 µm (top panel), 25 µm (middle panels), 40 µm (bottom panel). b–f Summary graphs showing rescue by NitroSynapsin of decreased number of total NeuN+ cell counts (b), reduced immunoreactivity of VGAT (d) and VGLUT2 (f), and increased ratio of VGLUT1/VGAT (e) or VGLUT2/VGAT (g) in the hippocampus of Mef2c-het mice. h Impaired LTP in Mef2c-het mice was also rescued by NitroSynapsin. Data are mean ± s.e.m., n = 4–5 per group in a–g and 7–9 in h. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, by ANOVA

We found that the reduction in NeuN+ cells in Mef2c-het mice could be accounted for at least in part by apoptotic cell loss because the number of neurons staining for active caspase-3 and for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) in the CA3 region of the hippocampus was significantly increased in Mef2c-het mice compared to WT (P < 0.012, Supplementary Fig. 8). Moreover, while the number of activated caspase 3-positive and TUNEL-positive cells was increased in Het/V, it was reduced back to normal in Het/N mice (Supplementary Fig. 8). This result is consistent with the notion that apoptotic neurons observed in Mef2c-het mice were significantly rescued by NitroSynapsin. Moreover, treatment with NitroSynapsin also normalized the number of GFAP+ cells with astrocytic morphology in Mef2c-het mice (Supplementary Fig. 9).

We next determined the effect of NitroSynapsin on altered expression of E/I markers in Mef2c-het mice by quantitative confocal immunohistochemistry. While the level of VGLUT1 immunoreactivity was unaltered by NitroSynapsin treatment, VGAT and VGLUT2 levels as well as the ratio of VGLUT1/VGAT or VGLUT2/VGAT were normalized by NitroSynapsin treatment in Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 7c–g). We also found that the numbers of both parvalbumin (PV)-expressing basket-interneurons and PV-positive synapses were significantly reduced in Mef2c-het mice (Supplementary Fig. 10), while NitroSynapsin significantly increased PV+ synapses (% area) (Supplementary Fig. 10). These results suggest that NitroSynapsin can restore E/I balance in Mef2c-het mice. Finally, chronic treatment with NitroSynapsin also significantly rescued impaired hippocampal LTP in Mef2c-het mice (Fig. 7h, Supplementary Fig. 11).

Discussion

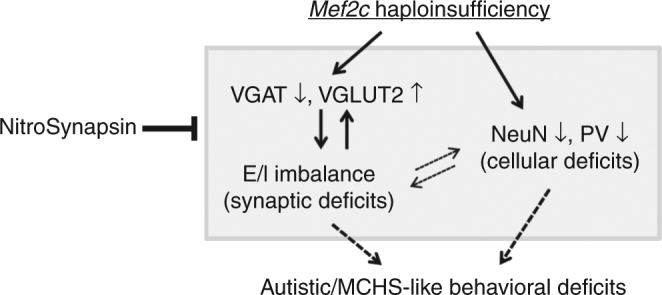

Genetic evidence has documented the role of MEF2C in multiple forms of human ASD, including MCHS11–22. In the current study (as summarized in Fig. 8), we provide evidence that Mef2c-het mice display MCHS-like behavioral deficits and thus represent a model for studying disease pathophysiology. Mef2c-het mice show reduced viability, the cause of which is currently unknown. Prior work has shown that systemic Mef2c-KO mice are embryonic lethal by E10.5 due to incomplete cardiac morphogenesis45; in contrast, nestin-cre-driven brain-specific Mef2c-KO mice exhibit reduced viability similar to that observed in the present study in Mef2c-hetmice10. It is thus possible that dysregulation of MEF2C activity in the central nervous system (CNS) is at least partially responsible for the increased lethality of Mef2c-het mice. The Mef2c-het mice that survive to adulthood exhibit a reduced number of neurons and synaptic impairment, specifically E/I imbalance caused by reduced inhibitory and enhanced excitatory neurotransmission. Importantly, treatment of Mef2c-het mice with the new, improved NMDAR antagonist NitroSynapsin34–36 not only corrects E/I imbalance, but also improves autistic/MCHS-like behavioral deficits, thus providing target validation and potential disease treatment.

Fig. 8.

Summary diagram of Mef2c haploinsufficiency leading to E/I imbalance and MCHS-like phenotypes that are rescued by NitroSynapsin. Mef2c haploinsufficiency leads to decreased VGAT and increased VGLUT2 protein levels, resulting in E/I imbalance (overexcitability) and synaptic dysfunction. Mef2c haploinsufficiency also causes neuronal loss, notably a reduced number of PV+ inhibitory interneurons. These synaptic and cellular abnormalities are likely the underlying cause of the MCHS-like behavioral phenotypes observed in Mef2c-het mice. The histological and behavioral phenotypes are ameliorated by chronic treatment with NitroSynapsin

We recently described the dual-functional mechanism of action of the drug NitroSynapsin36. Although originally termed a “NitroMemantine,” the drug is not strictly a derivative of memantine, but rather a novel aminoadamantane nitrate. The dual-functional drug acts both as an NMDAR open-channel blocker and redox modulator; in fact, the aminoadamantane moiety targets the nitro payload to the second site of action, the redox modulatory sites of the NMDAR, composed of critical regulatory cysteine residues. Recent publications have discussed the excellent CNS permeation of the drug, and its very good pharmacokinetic and phamacodynamic parameters34–36. Interestingly, aminoadamantane compounds like memantine have been previously shown to improve E/I imbalance30. In the case of NitroSynapsin, its improved action over previous aminoadamantanes at inhibiting hyperfunctioning extrasynaptic NMDARs is thought to represent the mechanism for regrowth of functional synapses that were compromised35, with resultant correction of E/I imbalance in the Mef2c-het model mice. One panoptic explanation for this effect based on our prior findings34–36 is that NitroSynapsin treatment, by protecting synapses, may indirectly increase excitatory input onto compromised inhibitory neurons in Mef2c-hets, thus enhancing their activity in order to compensate for the E/I imbalance.

Our results also show that VGAT was substantially reduced in Mef2c-het mouse hippocampus. In accord with this finding, functional inhibitory synaptic transmission was reduced, as demonstrated in recordings of spontaneous mIPSCs. In addition, VGLUT2 was aberrantly upregulated, consistent with an increase in excitatory neurotransmission, as documented by increased mEPSC frequency. Consequently, dysfunctional inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission contribute to E/I imbalance in the hippocampus of Mef2c-het mice. This pathophysiology may contribute eventually to both synapse elimination, loss of LTP, and neuronal loss. Importantly, NitroSynapsin substantially improved all three parameters in Mef2c-het mice, with increases in synaptic markers, LTP, and neuronal number. Moreover, NitroSynapsin significantly improved autistic/MCHS-like behaviors in Mef2c-het mice. In conclusion, we demonstrate that Mef2c-het mice represent a useful model for human MCHS. We further show that E/I imbalance may play a role in the pathogenesis of MCHS. Restoring synaptic plasticity and preventing neuronal loss with an appropriate NMDAR antagonist can rescue or ameliorate autistic/MCHS-like phenotypes in Mef2c-het mice.These results may thus have implications for the treatment of human MCHS and other forms of ID and ASD.

Methods

Mice and drug treatments

Mef2c heterozygous knockout (Mef2c-het) mice were created on the C57BL/6J background by crossing mice carrying the conventional exon 2-deleted allele of Mef2c (Mef2c Δ2)45 with their WT littermates. All procedures for maintaining and using these mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute. In this study, only male mice were used for thebehavioral assays to insure uniformity (either with or without drug treatment). Chronic treatment with memantine46, NitroSynapsin (both at 4.6 µmol/kg body weight)35,47 or vehicle (PBS) was administered via i.p. injection, twice a day for at least 3 months, starting at ~2.5 weeks of age. This age was chosen because mice are still juveniles and thus treatment could begin in human at an equivalent stage. We chose the dose and duration of drug treatment based on previous studies in which NitroSynapsin exhibited significant protective effects on neurons and synapses35,47.

Mice were randomly distributed to memantine, NitroSynapsin, or vehicle groups before being genotyped. Laboratory workers performing the i.p. injections and behavioral tests were blinded to genotypes. After behavioral tests, mice were used for either immunohistochemistry or electrophysiology, as described below, and studied in a blinded fashion.

Locomotor activity

Locomotor activity was measured in polycarbonate cages (42 × 22 × 20 cm) placed into frames (25.5 × 47 cm) mounted with two levels of photocell beams at 2 and 7 cm above the bottom of the cage (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). These two sets of beams allowed recording of both horizontal (locomotion) and vertical (rearing) behavior. A thin layer of bedding material was applied to the bottom of the cage. Mice were tested for 30 or 120 min depending on the exact test.

Paw clasping

For the paw clasping test10,37, mice were picked up by the distal third of their tails and observed for 10 s. They were rated in a blinded fashion with regard to genotype based on clasping of the front and/or back paws: 0—no paw clasping, 1—occasional clasping of front paws, and 3—constant clasping of front paws and occasional clasping of back paws.

Barnes maze

The Barnes maze consisted of an opaque Plexiglas disc 75 cm in diameter, elevated 58 cm above the floor by a tripod. Twenty holes, 5 cm in diameter, were located 5 cm from the perimeter, and a black Plexiglas escape box (19 × 8 × 7 cm) was placed under one of the holes. Distinct spatial cues were located all around the maze and kept constant throughout the study. On the first day of testing, a training session was performed, which consisted of placing the mouse in the escape box and leaving it there for 1 min. One minute later, the first session was started. At the beginning of each session, the mouse was placed in the middle of the maze in a 10-cm high cylindrical black start chamber. After 10 s, the start chamber was removed, a buzzer (80 dB) and a light (400 lux) were turned on, and the mouse was set free to explore the maze. The session ended when the mouse entered the escape tunnel or after 3 min had elapsed. When the mouse entered the escape tunnel, the buzzer was turned off and the mouse allowed to remain in the dark for 1 min. When a mouse did not enter the tunnel by itself, it was gently put into the escape box for 1 min. The tunnel was always located underneath the same hole (stable within the spatial environment), which was randomly determined for each mouse. Mice were tested once a day for 12 days for the acquisition portion of the study. Note, in general, the Barnes maze is often preferred in mice over the Morris water maze because it is less stressful. However, since we had tested rodents with NitroSynapsin for other indications using the Morris water maze36, it was also used here for drug testing to afford comparison.

Morris water maze

We tested spatial reference learning and memory using a version of the conventional Morris water maze48. The mice were trained to swim to a platform 14 cm in diameter and submerged 1.5 cm beneath the surface of the water. The platform was invisible to the mice while swimming. If a mouse failed to find the platform within 60 s, it was manually guided to the platform and allowed to remain there for 10 s. Mice were given four trials a day for as many days as necessary to reach the criterion (<20 s mean escape latency). Retention of spatial training was assessed 24 h after the last training trial. Both probe trials consisted of a 60-s free swim in the pool without the platform. The ANY-maze video tracking system (Stoelting Co.) was used to videotape all trials for automated analysis.

Three chamber social interaction

This test was originally developed by the Crawley group49 for an animal model of autism. Autistic individuals show aberrant reciprocal social interaction, including low levels of social approach and unusual modes of interaction. We used a social interaction apparatus consisting of a rectangular, three chambered Plexiglas box, with each chamber measuring 20 cm (length) × 40.5 cm (width) × 22 cm (height).Walls dividing the chamber were clear with small semicircular openings (3.5 cm radius), allowing access into each chamber. The middle chamber was empty and the two outer chambers contained small, round wire cages (Galaxy Cup, Spectrum Diversified Designs, Inc., Streetsboro, OH). The mice were habituated to the entire apparatus for 5 min. To assess social interaction, mice were returned to the middle chamber, this time with a stranger mouse (C57BL/6J of the same sex tethered to the wire cage). Time spent in the chamber with the stranger mouse and time spent in the empty wire cage-containing chamber were each recorded for 5 min, as was the number of entries into each chamber. Experimental mice were tested once, and the stranger C57BL/6J mice were used for up to six tests.

Hole board exploration

The apparatus consisted of a Plexiglas cage (32 × 32 × 30 cm) with 16 holes in a format of 4 × 4 (each 3 cm in diameter) equally spaced on an elevated floor. The explorative activity including the number of head-dips and the time spent head-dipping were measured for 5 min50.

Motor behavioral tests

Balance was measured by the latency to fall off the elevated (40 cm) horizontal rod (50 cm long) in four 20 s trials. A flat wooden rod (9 mm wide) was used in trials 1–2 and a cylindrical aluminium rod (1 cm diameter) was used in trials 3–4. In each trial, the animals were placed in a marked central zone (10 cm) on the elevated rod. A score of 0 was given if the animal fell within 20 s, 1 if it stayed within the central zone for 20 s, 2 if it left the central zone, and 3 if it reached one of the ends of the bar.Traction capacity was measured over three 5-s trials as the ability of the animal to raise the hind limbs while remaining suspended by the forepaws grasped around an elevated horizontal bar (2 mm diameter). A score of 0 was given if the animal raised no limbs, 1 if it raised one limb, and 2 it raised the two limbs. Muscle Strength was determined by one trial of 60 s in which the mice were placed in the middle of the horizontal bar in an upside-down position and the latency until falling down was measured. For the vertical pole test, mice were placed with heads pointing upwards on a vertical wooden pole covered with cloth tape (1 cm diameter; height: 75 cm in trial 1, 55 cm trials 2–3). The latency to turn downward and the total time to descend to the floor over three trials was recorded. If the mouse did not turn downwards, dropped or slipped down, a default value of 60 s was recorded.

Hippocampal slice preparation and electrophysiology

One to six-month-old mice were anesthetized with isoflurane overdose and decapitated. The brain was rapidly dissected, and hippocampal slices (350 µm in thickness) were collected in ice-cold dissection buffer containing the following (in mM): 212 sucrose, 3 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 1 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). The CA3 region was cut to avoid epileptiform activity. Slices were placed at 30 °C in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing the following (in mM): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). ACSF and dissection buffer were bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Before recordings, slices were placed in a submersion-recording chamber, maintained at 30 °C, and perfused with ACSF for ≥1 h.

For extracellular field recordings, concentric, bipolar tungsten electrodes were used to activate Schaffer collateral/commissural (SC) fibers in the hippocampal CA1 region. Extracellular glass microelectrodes filled with ACSF (resistance ~1–3 MΩ) were placed in the stratum radiatum to measure field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs). For baseline recordings, slices were stimulated at 0.033 Hz for 20 min at stimulation intensities of 30–40% of those used to elicit the largest measured fEPSP amplitude. LTP was induced by applying high-frequency stimulation consisting of three 100 Hz pulses (duration: 1 s, interval: 20 s). PPF was tested by applying two pulses with interstimulus intervals ranging from 20 to 200 ms. A Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) was used for experiments. Data were sampled at 5 kHz and analyzed using the Clampfit 10 program (Molecular Devices).

Synaptic activity was recorded from DG granule neurons using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. Data were acquired using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and Clampex 10.2 software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were sampled at 200 µs and filtered at 2 kHz. ACSF was used as the external bath solution, with 50 µM picrotoxin and 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX) to isolate spontaneous mEPSCs, or 10 µM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 50 µM (2R)-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate(AP5), and 1 µM TTX to isolate spontaneous mIPSCs. All solutions were allowed to equilibrate for at least 20 min prior to initiating recording. The pipette internal solution for the voltage-clamp experiments contained the following (in mM): 120 K-gluconate, 15 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, pH 7.4 (300 mOsm). mEPSCs and mIPSCs were typically recorded for at least 3–5 min and analyzed using the Mini Analysis Program version 6.0.3 (Synaptosoft).

Immunohistochemistry and unbiased stereological counting

Mice were perfused with PBS buffer and then 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS (PFA). After perfusion, brains were removed, and placed into 2% PFA overnight for post-fixation and then sunk in 30% sucrose in PBS prior to freezing. Cryostat sections were cut at a thickness of 15 µm. Sections were soaked in Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector) and microwaved for 30 s, followed by permeabilization with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. Primary antibodies were incubated for 16 h at 4 °C and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at 25 °C. Numerous unstained cells in each field served as an internal control for staining specificity. Primary antibodies included: NeuN (1:1000, mouse, EMD Millipore), activated caspase-3 (1:500, rabbit, Cell Signaling), VGLUT1 (1:200, guinea pig, Synaptic Systems (SYSY)), VGLUT2 (1:200, rabbit, SYSY), VGAT (1:250, mouse, SYSY), synaptophysin (1:200, mouse, Sigma), GFAP (1:500, mouse, Sigma), PCNA (1:100, mouse, Santa Cruz), and DCX (1:250, goat, Santa Cruz). TUNEL assay was performed to assess apoptosis using the Roche in situ cell death detection Kit per vendor’s instruction. The number of cells positive or percent area occupied by NeuN, activated caspase-3, TUNEL, GFAP, PCNA, or DCX was counted in specific brain regions using an optical dissector, or estimated by quantitative confocal immunohistochemistry or optical density10,35,46.

Preparation of brain lysates and western blotting

Brain tissue was homogenized in 10 volumes of cold sucrose buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 25 mM HEPES, pH7.4). After a brief centrifugation at 3000×g for 5 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 12 min at 4 °C. The outer three-fourths of the pellet was collected and re-suspended using the same sucrose buffer by gentle pipetting, while the dark center containing mitochondria was avoided. After a second centrifugation at 10,000×g for 12 min at 4 °C, the pellet without a dark center was collected in cold HBS (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) as the synaptosome-enriched brain lysate and used for western blot experiments51. Primary antibodies for immunoblotting included: VGLUT1 (1:1000, guinea pig, SYSY), VGLUT2 (1:1000, rabbit, SYSY), GAD65 (1:1000, rabbit, Millipore), synaptophysin (1:1000, mouse, Millipore), MEF2C (1:500, rabbit, Proteintech), α-tubulin (1:20,000, mouse, Sigma), and β-actin (1:10,000, mouse, Sigma) and followed by appropriate secondary antibodies52. Note that GAD65 was used instead of VGAT for immunoblotting because the former antibody proved superior forwestern blots. The immunosignals were captured on Kodak x-ray film and quantified using ImageJ version 1.45s (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). All uncropped western blots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 12.

Golgi staining and Sholl analysis

Standard Golgi-Cox impregnation was performed with WT and Mef2c-het brains using the FD Rapid GolgiStain kit (FD NeuroTechnologies, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After a 3D montage of an entire cell was taken at ×40 by deconvolution microscopy and reconstructed with SlideBook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations), Neurolucida neuron tracing software (MBF Bioscience) was used to delineate the whole cell profile and Sholl analysis was performed, as described in detail elsewhere39. Cumulative dendritic intersections and dendritic lengths were analyzed.

Adult neurogenesis

To study adult neurogenesis, 8-week-old mice were injected i.p. twice daily for 5 consecutive days with BrdU (50 mg/kg body weight) and perfused with 4% PFA 4 weeks after the last injection. Brains were then dissected and fixed overnight in 4% PFA, rinsed, cryoprotected, and frozen in liquid N2. Cryosections (30 or 40 µm in thickness) were sliced on a cryostat. Standard immunostaining procedures were used for primary antibodies with appropriate conjugated secondary antibodies. For BrdU immunostaining, sections were pretreated in 2 N HCL for 30 min. Cells positive for PCNA, DCX, BrdU, NeuN, or mCherry were analyzed in serial sections through the hippocampal DG of Mef2c-het and WT mice. We counted positive cells under a ×63 objective using SlideBook software. The total number of cells was counted using an optical dissector technique. Pictures were taken with the same exposure time and contrast/brightness parameters. The mean intensity for a particular marker was determined using ImageJ software and normalized to the average intensity of DG granule neurons. A minimum of six pictures containing at least 40 cells was analyzed for each marker.

Microarray and NextBiogene network analysis

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues prepared from the hippocampi of WT and Mef2c-het mice at postnatal day 30, using the Qiagen miRNA kit. RNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer. All RNA samples included in the expression analysis had an RNA integrity number (RIN) >8. MouseRef-8 v2 expression beadchip (Illumina) was used for the gene-expression microarray. Microarray data analysis was performed using the R software and Bioconductor packages. Raw expression data were log2 transformed and normalized by quantile normalization. Data quality control criteria included high inter-array correlation (Pearson correlation coefficients >0.85) and detection of outlier arrays based on mean inter-array correlation and hierarchical clustering.

For pathway enrichment analysis, all genes whose expression was statistically altered (P < 0.05) in Mef2c-het mice relative to WT mice were clustered for GO terms using the pathway enrichment application of NextBio (Illumina, Inc.). The background set of genes used was the entire human genome. Rank scores were assigned by NextBio53. Genes clustered to GO terms related to neuronal development were prioritized for validation of changes in gene expression.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical tests in each experiment are listed here, in figure legends, or in the text. All data were analyzed using the Prism 6 program (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For data with a normal distribution, statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test for pairwise comparisons. An ANOVA with Tukey’s, Dunnett’s, or Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis was used for multiple comparisons. For categorical data, a χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test on a 2 × 2 contingency table was employed. For data not fitting a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The raw data for the microarray (presented in Supplementary Data 1) have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database under accession code GSE103298.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants P01 HD029587, R01 NS086890, R01 AG056259, RF1 AG057409, DP1 DA041722, and P30 NS076411, by Department of Defense (Army) grant W81XWH-13-0053, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (to S.A.L.); and by Department of Defense (Army) grant W81XWH-09-1-0229 (to N.N. and S.A.L.); and by NIH grants R43 AG052233 and R43 AG055208 (to S.T.), R21 AG048519 (to S.T. and H.X.). R.M.E. received a fellowship from the Generalitat de Catalunya (AGAUR, 2010 BE1 00954).

Author contributions

S.T., H.X., S.A.L. and N.N. designed the experiments, performed data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. M.A. and X.Z. performed electrophysiology and data analysis. S.T., R.M.E., T.H., K.L., A.S. and A.J.R. performed behavioral tests. S.T., A.A-A., J.P., J.D.Z., N.B., D.R.H., S.F.C., L.Y., S.R.M., R.A., Y.W., A.V.T. and E.M. performed molecular/biochemical experiments and data analysis. V.S., S.D.R., X.H. and D.H.G. performed gene expression analysis. X.H. performed statistical analyses.

Competing interests

The authors declare that S.A.L. is the inventor on worldwide patents for the use of memantine and NitroSynapsin for neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders. Per Harvard University guidelines, S.A.L. participates in a royalty-sharing agreement with his former institution Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, which licensed the drug memantine (Namenda®) to Forest Laboratories, Inc./Actavis/Allergan, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01563-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shichun Tu, Email: shichuntu@scintillon.org.

Stuart A. Lipton, Email: slipton@scripps.edu

Nobuki Nakanishi, Email: nnakanishi@scintillon.org.

References

- 1.Leifer D, et al. MEF2C, a MADS/MEF2-family transcription factor expressed in a laminar distribution in cerebral cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:1546–1550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin JF, Schwarz JJ, Olson EN. Myocyte enhancer factor (MEF) 2C: a tissue-restricted member of the MEF-2 family of transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:5282–5286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto S, Krainc D, Sherman K, Lipton SA. Antiapoptotic role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-myocyte enhancer factor 2 transcription factor pathway during neuronal differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7561–7566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130502697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shalizi A, et al. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science. 2006;311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flavell SW, et al. Activity-dependent regulation of MEF2 transcription factors suppresses excitatory synapse number. Science. 2006;311:1008–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1122511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, et al. Myocyte enhancer factor 2C as a neurogenic and antiapoptotic transcription factor in murine embryonic stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6557–6568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0134-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbosa AC, et al. MEF2C, a transcription factor that facilitates learning and memory by negative regulation of synapse numbers and function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802679105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikshak NN, et al. Integrative functional genomic analyses implicate specific molecular pathways and circuits in autism. Cell. 2013;155:1008–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilissen C, et al. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, et al. Transcription factor MEF2C influences neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and maturation in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9397–9402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802876105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardoso C, et al. Periventricular heterotopia, mental retardation, and epilepsy associated with 5q14.3-q15 deletion. Neurology. 2009;72:784–792. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336339.08878.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engels H, et al. A novel microdeletion syndrome involving 5q14.3-q15: clinical and molecular cytogenetic characterization of three patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;17:1592–1599. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berland S, Houge G. Late-onset gain of skills and peculiar jugular pit in an 11-year-old girl with 5q14.3 microdeletion including MEF2C. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2010;19:222–224. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32833dc589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bienvenu T, Diebold B, Chelly J, Isidor B. Refining the phenotype associated with MEF2C point mutations. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:71–75. doi: 10.1007/s10048-012-0344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Meur N, et al. MEF2C haploinsufficiency caused by either microdeletion of the 5q14.3 region or mutation is responsible for severe mental retardation with stereotypic movements, epilepsy and/or cerebral malformations. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:22–29. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novara F, et al. Refining the phenotype associated with MEF2C haploinsufficiency. Clin. Genet. 2010;78:471–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowakowska BA, et al. Severe mental retardation, seizures, and hypotonia due to deletions of MEF2C. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. 2010;153B:1042–1051. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikhail FM, et al. Clinically relevant single gene or intragenic deletions encompassing critical neurodevelopmental genes in patients with developmental delay, mental retardation, and/or autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A:2386–2396. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zweier M, et al. Mutations in MEF2C from the 5q14.3q15 microdeletion syndrome region are a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and diminish MECP2 and CDKL5 expression. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:722–733. doi: 10.1002/humu.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr CW, et al. 5q14.3 neurocutaneous syndrome: a novel continguous gene syndrome caused by simultaneous deletion of RASA1 and MEF2C. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155:1640–1645. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonk V, Kyhm JH, Gibson CE, Wilson GN. Interstitial deletion 5q14.3q21.3 with MEF2C haploinsufficiency and mild phenotype: when more is less. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155:1437–1441. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paciorkowski A, et al. MEF2C haploinsufficiency features consistent hyperkinesis, variable epilepsy, and has a role in dorsal and ventral neuronal developmental pathways. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrow EM, et al. Identifying autism loci and genes by tracing recent shared ancestry. Science. 2008;321:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1157657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao H-T, et al. Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature. 2010;468:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nature09582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penagarikano O, et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell. 2011;147:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han K, et al. SHANK3 overexpression causes manic-like behaviour with unique pharmacogenetic properties. Nature. 2013;503:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S, Tai C, Jones CJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Enhancement of inhibitory neurotransmission by GABAA receptors having α2,3-subunits ameliorates behavioral deficits in a mouse model of autism. Neuron. 2014;81:1282–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz DM, et al. Preclinical research in Rett syndrome: setting the foundation for translational success. Dis. Model. Mech. 2012;5:733–745. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chahrour M, et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martina M, Comas T, Mealing GAR. Selective pharmacological modulation of pyramidal neurons and interneurons in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. Front. Pharmacol. 2013;4:24. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia P, Chen HX, Zhang D, Lipton SA. Memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptor currents in hippocampal autapses. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:11246–11250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chez MG, et al. Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. J. Child Neurol. 2007;22:574–579. doi: 10.1177/0883073807302611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fung LK, Hardan AY. Developing medications targeting glutamatergic dysfunction in autism: progress to date. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, et al. The pharmacology of aminoadamantane nitrates. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:201–204. doi: 10.2174/156720506777632808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talantova M, et al. A β induces astrocytic glutamate release, extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation, and synaptic loss. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E2518–E2527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306832110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahashi H, et al. Pharmacologically targeted NMDA receptor antagonism by NitroMemantine for cerebrovascular disease. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14781. doi: 10.1038/srep14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lalonde R, Strazielle C. Brain regions and genes affecting limb-clasping responses. Brain Res. Rev. 2011;67:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makanjuola RA, Hill G, Maben I, Dow R, Ashcroft G. An automated method for studying exploratory and stereotyped behaviour in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1977;52:271–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00426711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, et al. Nna1 mediates Purkinje cell dendritic development via lysyl oxidase propeptide and NF-κB signaling. Neuron. 2010;68:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herzog E, et al. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneko T, Fujiyama F, Hioki H. Immunohistochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;444:39–62. doi: 10.1002/cne.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin X, Shah S, Bulleit RF. The expression of MEF2 genes is implicated in CNS neuronal differentiation. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;42:307–316. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(96)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shalizi AK, Bonni A. Brawn for brains: the role of MEF2 proteins in the developing nervous system. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2005;69:239–266. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)69009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krainc D, et al. Synergistic activation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit 1 promoter by myocyte enhancer factor 2C and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26218–26224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin Q, Schwarz J, Bucana C, Olson EN. Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C. Science. 1997;276:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okamoto S, et al. Balance between synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity influences inclusions and neurotoxicity of mutant huntingtin. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nm.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakanishi N, et al. Differential effects of pharmacologic and genetic modulation of NMDA receptor activity on HIV/gp120-induced neuronal damage in an in vivo mouse model. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2016;58:59–65. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0651-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal Aβ causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moy SS, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.File SE, Wardill AG. The reliability of the hole-board apparatus. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;44:47–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00421183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakanishi N, et al. Synaptic protein α1-takusan mitigates amyloid-β-induced synaptic loss via interaction with tau and postsynaptic density-95 at postsynaptic sites. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:14170–14183. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4646-10.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tu S, et al. Takusan: a large gene family that regulates synaptic activity. Neuron. 2007;55:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kupershmidt I, et al. Ontology-based meta-analysis of global collections of high-throughput public data. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. The raw data for the microarray (presented in Supplementary Data 1) have been deposited in the NCBI GEO database under accession code GSE103298.