Abstract

This paper aims to study the dynamics of immune suppressors/checkpoints, immune system, and BCG in the treatment of superficial bladder cancer. Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) are some of the examples of immune suppressors/checkpoints. They are responsible for deactivating the immune system and enhancing immunological tolerance. Moreover, they categorically downregulate and suppress the immune system by preventing and blocking the activation of T-cells, which in turn decreases autoimmunity and enhances self-tolerance. In cancer immunotherapy, the immune checkpoints/suppressors prevent and block the immune cells from attacking, spreading, and killing the cancer cells, which leads to cancer growth and development. We formulate a mathematical model that studies three possible dynamics of the treatment and establish the effects of the immune checkpoints on the immune system and the treatment at large. Although the effect cannot be seen explicitly in the analysis of the model, we show it by numerical simulations.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a class of diseases characterized by out-of-control cell growth which affects and damages the DNA. Cancer prevalence is increasing in many countries [1]. Many treatment options of cancer exist, which include surgery, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, vaccine therapy, and hormonal therapy [1, 2]. The mode and type of treatment depend on the type, location, and grade of the cancer and the patient's body. The bladder is a hollow organ in the lower abdomen which collects urine produced by the kidneys. Bladder cancer is a growth of malignant cells initiating in the urinary bladder. It is common, with around 38,000 men and 15,000 women diagnosed every year in the United States. Approximately 400,000 new cases are diagnosed and about 150,000 die directly from the disease every year across the globe [3, 4].

The bladder wall is lined with cells called transitional and squamous cells. The most common type of bladder cancer is urothelial carcinoma or transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). It mostly originates from the transitional cells and further progresses and grows superficially on the inner surface of the bladder; as a result, it invades the bladder wall and vessels, dispersing into the neighboring organs as well as forming distant metastases [5–7].

One of the most effective ways of treating bladder cancer is immunotherapy. This is the process of stimulating, activating, and triggering the immune system to spread, locate, and kill cancer cells [8].

Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is an attenuated nonpathogenic strain of Mycobacterium bovis that was initially used as a vaccine against tuberculosis. The attenuation was reached via manipulation of the bacillus by serial growth on a culture medium. As a result, the genes causing virulence will be lost and inoculated into humans [9, 10]. It is undoubtedly the most efficient and successful immunotherapy of cancer [9]. BCG therapy is used for various types of cancers, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia and melanoma. The first report of successful use of BCG to treat patients with bladder cancer was in 1976 by Morales et al. They obtained the efficacy of BCG therapy and established it as the pillar for the treatment of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer after transurethral resection [5, 11].

Intravesical BCG is a type of immunotherapy that is also used to treat superficial bladder cancer [12, 13]. It is usually applied after local surgery to prevent tumor recurrence. It is given in 6-weekly intravesical instillation of 1.5 × 108 bacteria, which has been proven to be superior to chemotherapy in reducing recurrence rates of the tumor [12–14]. When the BCG is instilled and processed into the bladder, it creates an inflammatory environment which in turn stimulates an immune response, resulting in attacking the cancer cells. Therefore, many researchers believed that BCG reduces tumor progression and stated that the primary role of BCG treatment is to stimulate, trigger, and activate the immune effector cells in order to attack the cancer cells. In spite of the fact that BCG instillation is regarded as the “gold standard” treatment, it has many side effects which include hematuria, pain, dysuria, and fever, to mention a few [7–14].

Immune checkpoints are negative regulators of the immune system which play important roles in maintaining self-tolerance, preventing autoimmunity, and protecting tissues from immune collateral damage. These immune checkpoints are often hijacked by tumors to restrain the ability of the immune system to mount an effective antitumor response. The tumors neutralize some immune checkpoint pathways in order to maintain immune resistance, particularly against T-cells. The T-cells are specific tumor antigens. Examples of the aforementioned checkpoints are PD-1 and CTLA4 [15–17].

Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) is a protein that is encoded by the PDCD1 gene in humans. It is a cell surface receptor which belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily and is expressed on T-cells and pro-B-cells. PD-1 binds two ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. The PD-1 acts as an immune checkpoint, which plays an important role in downregulating the immune system by preventing the activation of the T-cells. Hence, it decreases autoimmunity and encourages self-tolerance [18, 19]. The immune system is directly affected by the activities of PD-1 in the sense that it suppresses, blocks, and deactivates the immune cells from spreading, fighting, and attacking the cancer cells. Therefore, PD-1 aids in growth, development, and progression of the cancer. In conclusion, it disrupts and affects immunotherapy [20–24].

Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) is a regulatory cytokine which suppresses immune function in cancers and in chronic viral infections. It inhibits the activation of the T-cells and subdues their proliferation. Hence, cancer cells take advantage of this immune checkpoint pathway as a way to escape and evade detection. This leads to the inhibition of antitumor immune response, resulting in cancer growth and development [25, 26].

Mathematical modeling and simulation helps in predicting treatments' outcome, as well as describing the behavior and complex dynamics involved. Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky et al. (2007, 2008, and 2011) modeled mathematically the use of BCG in noninvasive bladder cancer, where their study identified fixed points and conditions for stability of the dynamical system [6, 8, 14]. In 2016, Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky developed a new mathematical model for combined BCG and IL-2 bladder cancer treatment which introduces the effect of TAA T-cells. Furthermore, Starkov utilized a mathematical approach for bladder cancer treatment model in the derivation of ultimate upper and lower bounds. He also presented tumor clearance conditions for BCG treatment of bladder cancer [13].

In this research, we formulate a mathematical model to study the dynamics of immune checkpoints/suppressors, immune system, and the BCG immunotherapy of bladder cancer. Moreover, we highlight the effects of immune checkpoints/suppressors on the immune system and the treatment numerically.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 1 is the introduction. Section 2 is the formulation and presentation of our model. We give the stability analysis and numerical simulations in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. In the final section, we state our conclusions and discussions.

2. Formulation of the Model

The model consists of a system of four nonlinear differential equations, which characterize the dynamics of the interaction between cancer cells (C), different arms of the immune system regarded as effector cells (E), the BCG (B), and all categories of immune suppressors/checkpoints as (P).

2.1. Dynamics of Cancer Cells

The dynamics of cancer cells is given by

| (1) |

Here, we assume that, in the absence of the immune system, the cancer cells grow exponentially with growth rate r. The second term shows the elimination of cancer cells by the effector cells at the rate α1, while 1/(P + k) is the immunosuppressive factor by the immune checkpoints/suppressors, which interrupts the activities of the effector cells, with k being an inhibitory parameter.

2.2. Dynamics of the Effector Cells

The dynamics of the effector cells is given by

| (2) |

The first term here gives the recruitment of effector cells at the rate a1 which is directly proportional to the population of cancer cells (i.e., occurring due to the direct presence of cancer cells). a2BE shows the activation of effector cells by BCG at the rate a2. a1 is the antigenicity of cancer cells which triggers an immune response in the host. It is believed that the immune checkpoints will distort both the recruitment and the activation of effector cells; hence, 1/(P + k) is the immunosuppressive response which puts a limitation on the recruitment level and interrupts the activation of effector cells, with k here being an inhibitory parameter. The next term gives the elimination of effector cells by the cancer cells at the rate α2, and the last term describes the degradation of effector cells at the rate μ1.

2.3. Dynamics of BCG

The dynamics of BCG is given by

| (3) |

The first term b is the constant rate of introduction of BCG into the bladder, the second term describes the elimination of BCG by effector cells at the rate α3, and the third term gives the decay of BCG at the rate μ2.

2.4. Dynamics of Immune Suppressors/Checkpoints

The dynamics of the immune checkpoints is given by

| (4) |

The first term gives the source of immune checkpoints at a constant rate δ, and the second term is the degradation of the immune checkpoints at the rate μ3.

Finally, the interactions of the cancer cells, effector cells, BCG, and immune checkpoints together lead to the following nonlinear ordinary differential equations:

| (5) |

with initial conditions C(0) = C0 ≥ 0, E(0) = E0 ≥ 0, B(0) = B0 ≥ 0, and P(0) = P0 ≥ 0.

2.5. Invariance of Positive Orthant

We show that the system is positively invariant.

From the system, assume C(0) > 0, E(0) > 0, B(0) > 0, and P(0) > 0.

From dC/dt = rC − α1EC/(P + k), the solution is given by C(t) = C0exp(∫0t(r − α1E/(P + k))dt). This implies C(t) > 0 given that C0 > 0. Also, from dB/dt = b − α3EB − μ2B, if B = 0, then dB/dt = b > 0. Therefore, B(t) > 0 ∀t since B0 > 0. Moreover, if b = 0, then B(t) = B0exp(−∫0t(α3E + μ2)dt) implying B(t) > 0 ∀t since B0 > 0. Using dP/dt = δ − μ3P, if δ = 0, then P(t) = P0exp(−∫0tμ3dt) > 0 since P0 > 0.

Also, if P = 0 and δ > 0, then dP/dt = δ which implies P(t) > 0 ∀t given that P0 > 0. Now consider dE/dt = (a1C + a2B)E/(P + k) − α2EC − μ1E, E(t) = E0 exp(∫0t((a1C + a2B)/(P + k) − α2C − μ1)dt) > 0 given that E0 > 0.

This implies that E(t) > 0 ∀t if E0 > 0. Hence, the positive orthant R+4 is invariant and C(t) > 0, E(t) > 0, B(t) > 0, and P(t) > 0 ∀t.

3. Equilibrium and Stability Analysis

3.1. Model without Treatment (b = 0)

We first analyze our model in the absence of treatment (b = 0):

| (6) |

The equilibrium points of the model are obtained by equating the equations in (6) to zero and solving simultaneously for C, E, B, and P. They are as follows:

| (7) |

From the invariance of the positive orthant, we concentrate only on the nonnegative equilibria assuming all initial conditions are positive.

As a result, the equilibrium point U1 will not be considered. Moreover, U2 exists only if the following condition is satisfied:

| (8) |

The Jacobian matrix obtained from (6) is given by

| (9) |

3.2. Stability Analysis of Equilibria of Model (6)

3.2.1. Immune Checkpoints Equilibrium: U0 = {0,0, 0, δ/μ3}

The Jacobian matrix evaluated at U0 yields

| (10) |

The eigenvalues of are

| (11) |

Since one of the eigenvalues is always positive, then U0 is an unstable saddle point. Clinically, U0 is referred to as the death equilibrium.

3.2.2. BCG-Free Equilibrium: U2 = {μ1r(δ + kμ3)2/(α1a1μ32 − rα2(δ + kμ3)2), r(δ + kμ3)/α1α3, 0, δ/μ3}

Assume U2 exists; that is, a1μ3 > α2(δ + kμ3); then, substituting U2 in yields the following eigenvalues:

| (12) |

Two of the eigenvalues have a real part equal to zero, which signifies neutral stability. Therefore, the equilibrium point U2 is neutrally stable.

Conclusively, in the absence of treatment, none of the equilibrium points was found to be stable.

3.3. Model without Immune Checkpoints

Now, we analyze the model without any suppression on the immune system by the immune checkpoints. The model is given by

| (13) |

The equilibrium points are as follows:

| (14) |

The equilibrium point U1 exists only if ba2 ≥ μ1μ2. This means that the cancer cells will disappear if the constant rate of introduction of BCG and activation rate of BCG are bigger than the degradation rates of both the effector cells and the BCG.

The equilibrium point U2 also exists if

μ2α1μ1 + α3rμ1 ≥ a2bα1 and α3a1r + a1α1μ2 ≥ α3ra2 + μ2α1α2,

μ2α1μ1 + α3rμ1 ≤ a2bα1 and α3a1r + a1α1μ2 ≤ α3ra2 + μ2α1α2.

From model (13), we have the following Jacobian matrix:

| (15) |

3.4. Stability Analysis of Equilibria of Model (13)

3.4.1. BCG Equilibrium: U0 = {0,0, b/μ2}

The eigenvalues of evaluated at U0 are

| (16) |

The eigenvalue λ1 is always positive and the rest are negative. Therefore, the equilibrium point U0 is an unstable saddle point.

3.4.2. Cancer-Free Equilibrium: U1 = {0, (ba2 − μ1μ2)/μ1α3, μ1/a2}

Assume the equilibrium point U1 exists; then, substituting U1 in will give the following matrix:

| (17) |

The eigenvalues of are

| (18) |

Now, if

λ2 and λ3 are complex roots, then U1 is a stable fixed point if a1ba2 > μ1(rα3 + μ2);

λ2 and λ3 are real roots, then U1 is a stable fixed point if ba2 > μ1μ2 and a1ba2 > μ1(rα3 + μ2).

But since we already assume that the equilibrium point U1 exists, then ba2 > μ1μ2, and we can conclude that U1 is a stable fixed point if a1ba2 > μ1(rα3 + μ2).

This means that the effector cells activated by BCG will eradicate/destroy the cancer cells, if the constant rate of introduction of BCG, recruitment rate of effector cells, and the activation rate of effector cells by BCG are bigger than or can overcome the cancer growth rate, the rate of elimination of BCG by effector cells, and the degradation rates of effector cells and BCG altogether. Therefore, to eliminate the cancer, we increase the rate of introduction of BCG, rate of recruitment of effector cells, and activation rate of effector cells by BCG and at the same time decrease the rate of elimination of BCG by effector cells, degradation rates of both effector cells and BCG, and the cancer growth rate.

3.5. Model with Treatment and Immune Checkpoints

We now consider the dynamics of cancer cells, effector cells BCG, and immune checkpoints (see (5)).

The equilibrium points of model (5) are as follows:

| (19) |

| ∗ |

Also, U2 exists if

α3rδ2μ1 + 2α3rδμ1μ3k + α3rk2μ32μ1 + μ2α1μ32μ1k + μ2α1μ3μ1δ ≥ μ32a2bα1 and α3μ3rδa1 + α3rkμ32a1 + μ2μ32α1a1 ≥ rδ2α3α2 + 2α3rδα2kμ3 + α3rk2μ32α2 + μ2α1μ3α2δ + μ2α1μ32α2k;

α3rδ2μ1 + 2α3rδμ1μ3k + α3rk2μ32μ1 + μ2α1μ32μ1k + μ2α1μ3μ1δ ≤ μ32a2bα1 and α3μ3rδa1 + α3rkμ32a1 + μ2μ32α1a1 ≤ rδ2α3α2 + 2α3rδα2kμ3 + α3rk2μ32α2 + μ2α1μ3α2δ + μ2α1μ32α2k.

From model (5), we obtain the following Jacobian matrix:

| (20) |

3.6. Stability Analysis of Equilibria of Model (5)

3.6.1. BCG and Immune Checkpoints Equilibrium: U0 = {0,0, b/μ2, δ/μ3}

The eigenvalues of evaluated at U0 are

| (21) |

Since one of the eigenvalues is always positive, then U0 is an unstable saddle point.

3.6.2. Tumor-Free Equilibrium: U1 = {0, (bμ3a2 − μ2μ1δ − μ2μ1kμ3)/μ1α3(δ + kμ3), μ1(δ + kμ3)/μ3a2, δ/μ3}

Assume this equilibrium point exists; then, the eigenvalues of evaluated at U1 are as follows:

| (22) |

The equilibrium point U1 is a stable fixed point if

| (23) |

However, condition ∗ is already true; then, U1 is a stable fixed point if

| (24) |

3.6.3. Interior Equilibrium: U2 = {C∗, r(δ + kμ3)/μ3α1, bα1μ3/(α3r(δ + kμ3) + α1μ3μ2), δ/μ3}

The eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are very long, complicated, and difficult to analyze. Therefore, we use numerical simulations to show the stability of the equilibrium point U2.

4. Numerical Illustrations

In this section, the numerical simulations of the three models will be shown. The aim here is to show the effect of immune checkpoints on the effector cells. We use MATLAB version 2016b to plot the graphs with initial populations of the compartments involved taken to be equal. Other parameters used in the numerical simulations are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of all parameters used in numerical simulations.

| Parameter | Interpretation (units) |

Estimated value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| r | Tumor growth rate t−1 = day−1 |

0.0033 | Shochat et al., 1999 |

| α 1 | Rate of elimination of cancer cells by effector cells cell day−1 |

1.1 × 10−7 | Kuznetsov et al., 1994 |

| k | Inhibitory parameter | 2 × 103 | Not found |

| a 1 | Recruitment rate of effector cells t−1 = day−1 |

0.25 | Sud D. et al., 2006 |

| a 2 | Activation rate of effector cells by the BCG cells−1 day−1 |

0.052 | Wigginton and Kirschner, 2001 |

| δ | Internal production of immune checkpoints | 1.51932 × 105 | Sandip Banerjee et al., 2015 |

| α 2 | Elimination rate of effector cells by cancer cells cells−1 day−1 |

3.45 × 10−10 | Kuznetsov et al., 1994 |

| μ 1 | Degradation rate of effector cells t−1 = day−1 |

0.041 | Kuznetsov et al., 1994 |

| μ 2 | Rate of BCG decay t−1 = day−1 |

0.1 | Archuleta et al., 2002 |

| b | Bioeffective concentration of BCG c.f.u./day |

6.5 × 105 | Cheng et al., 2004 |

| α 3 | Destruction of BCG by effector cells cells−1 day−1 |

1.25 × 10−7 | Wigginton and Kirschner, 2001 |

| μ 3 | Degradation rate of immune checkpoints t−1 = day−1 |

166.32 | Sandip Banerjee et al., 2015 |

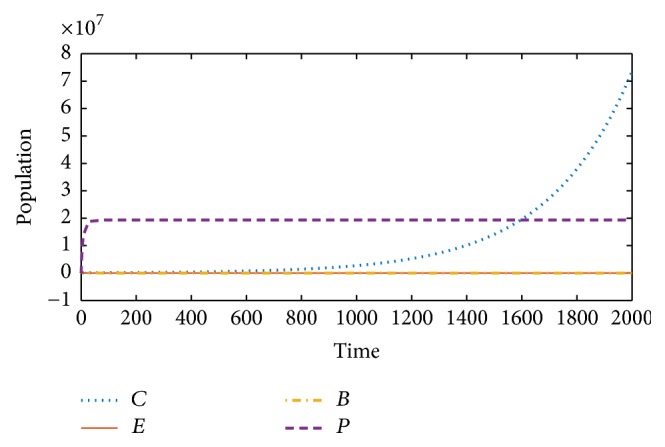

We first plot the graph of model (6) to illustrate what happens in the absence of treatment. As expected, the cancer cells develop with the help of suppression on the effector cells by the immune checkpoints, hence dominating the effector cells and resulting in the growth and maturation of the cancer. Therefore, the numerical simulations of model (6) support this notion as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model (6) (without treatment): cancer cells (C) grow exponentially, overcoming the effector cells (E), with the help of immune checkpoints (P).

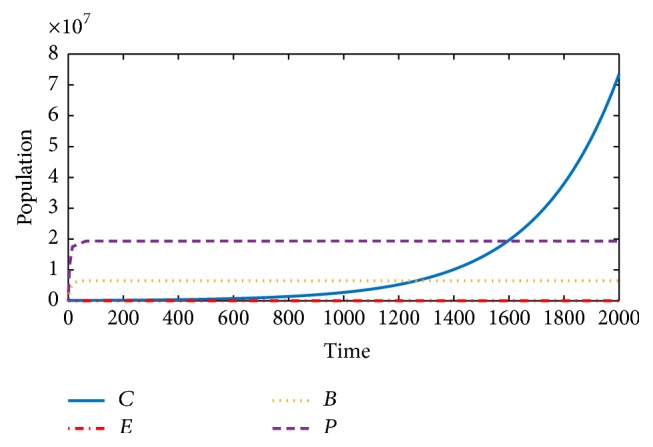

Next, we show the behavior of model (13) (i.e., without the immune checkpoints). Here, we will see how the effector cells attack and kill the cancer cells as a result of the stimulation/activation by the BCG. Unlike in Figure 1, Figure 2 shows how the growth of the cancer cells is restricted and eventually leads to their extinction by the effector cells.

Figure 2.

Model (13) (without immune suppressors): the effector cells (E) overcome the development of cancer cells (C) as a result of the stimulation and activation by the BCG (B).

The general model will now be considered. Despite stimulation and activation of the effector cells by the BCG, the immune suppressors block and deactivate their function; hence, this leads to the reduction of autoimmunity of the effector cells. Therefore, the cancer develops and grows exponentially as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Model (5): despite the stimulation of effector cells (E) by the BCG (B), the immune checkpoints (P) block and deactivate the activities of the effector cells, thereby leading to the development and progression of cancer cells (C).

Therefore, comparing Figures 2 and 3, we will notice the effect of immune checkpoints on the effector cells. In Figure 2, the effector cells in the absence of immune suppressors fight the cancer cells, resulting in stopping their development and progression, while Figure 3 shows the progression and development of the cancer cells as a result of the presence of immune suppressors.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

In this paper, we used a system of four nonlinear ordinary differential equations to model the dynamics of cancer cells, effector cells, BCG, and immune checkpoints/suppressors in the immunotherapy of bladder cancer. We derived three possible dynamics from our model. Firstly, the model was analyzed in the absence of treatment and we studied the stability analysis of the equilibria involved. Figure 1 shows how the cancer progressed in the absence of treatment and presence of immune checkpoints/suppressors.

Secondly, we study the model without the immune checkpoints/suppressors. Conditions for stability of the equilibria involved were also given. In the absence of immune checkpoints/suppressors, the activated-effector cells have unlimited freedom to roam about and detect the cancer cells; as a result, they kill them and stop the cancer from progressing. This was shown in Figure 2.

Thirdly, we considered the dynamics of the model with treatment and the immune checkpoints/suppressors. Conditions for stability of the equilibrium points were given, and Figure 3 shows how the cancer cells grow and develop despite the application of the treatment (BCG). This is believed to be as a result of the blockage and suppression that the effector cells suffered by the immune checkpoints.

Therefore, the figures used in this paper assist in showing the effect of immune checkpoints/suppressors on the effector cells and the treatment at large. To avoid cancer progression and advancement, there is a need for action to block or limit the production of the immune checkpoints. This will take the brakes off the immune system and thereby allow it to mount a stronger and more effective attack against cancer cells.

Nivolumab is a drug recently approved by the FDA to be used alone or with other drugs to treat cancer. It is a fully human immunoglobulin (Ig) G4 monoclonal antibody directed against the negative immunoregulatory human cell surface receptor programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) with immune checkpoint inhibitory and antineoplastic activities. Nivolumab binds to and blocks the activation or production of immune checkpoints like PD-1. This results in the activation of T-cells and cell-mediated responses against cancer cells. So, the primary role of nivolumab is to block the immune checkpoints from suppressing the immune systems. Hence, this helps in allowing the immune cells to rise against cancer cells without any interference [16, 17].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Böhle A., Brandau S. Immune mechanisms in bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. The Journal of Urology. 2003;170(3):964–969. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000073852.24341.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirschner D., Panetta J. C. Modeling immunotherapy of the tumo—immune interaction. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1998;37(3):235–252. doi: 10.1007/s002850050127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapoor R., Vijjan V., Singh P. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the management of superficial bladder cancer. Indian Journal of Urology. 2008;24(1):72–76. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.38608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky S., Halachmi S., Kronik N. Improving BCG immunotherapy for bladder cancer by adding interleukin-2 (IL-2): A mathematical model. Mathematical Medicine and Biology. A Journal of the IMA. 2016;33(2):159–188. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqv007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuge O., Vasdev N., Allchorne P., Green J. S. Immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Research and Reports in Urology. 2015;7:65–79. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S63447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky S., Shochat E., Stone L. Mathematical model of {BCG} immunotherapy in superficial bladder cancer. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2007;69(6):1847–1870. doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai K., Miyazaki J., Joraku A., Nishiyama H., Akaza H. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunotherapy for bladder cancer: Current understanding and perspectives on engineered BCG vaccine. Cancer Science. 2013;104(1):22–27. doi: 10.1111/cas.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky S., Byrne H., Stone L. Mathematical model of pulsed immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2008;70(7):2055–2076. doi: 10.1007/s11538-008-9344-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Askeland E. J., Newton M. R., O’Donnell M. A., Luo Y. Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy: BCG and Beyond. Advances in Urology. 2012;2012:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2012/181987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redelman-Sidi G., Glickman M. S., Bochner B. H. The mechanism of action of BCG therapy for bladder cancer-a current perspective. Nature Reviews Urology. 2014;11(3):153–162. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andius P., Holmäng S. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy in stage Ta/T1 bladder cancer: Prognostic factors for time to recurrence and progression. BJU International. 2004;93(7):980–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamm D. L., Thor D. E., Harris S. C., Reyna J. A., Stogdill V. D., Radwin H. M. Bacillus Calmette-guerin Immunotherapy of Superficial Bladder Cancer. The Journal of Urology. 1980;124(1):38–42. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)55282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starkov K. E., Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky S. Dynamical properties and tumor clearance conditions for a nine-dimensional model of bladder cancer immunotherapy. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 2016;13(5):1059–1075. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2016030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunimovich-Mendrazitsky S., Claude Gluckman J., Chaskalovic J. A mathematical model of combined Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) immunotherapy of superficial bladder cancer. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2011;277:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thibult M., Mamessier E., Gertner-Dardenne J., et al. PD-1 is a novel regulator of human B-cell activation. International Immunology. 2013;25(2):129–137. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pardoll D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postow M. A., Callahan M. K., Wolchok J. D. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(17):1974–1982. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.59.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paillard F. Commentary: Immunosuppression Mediated by Tumor Cells: A Challenge for Immunotherapeutic Approaches. Human Gene Therapy. 2000;11(5):657–658. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohaegbulam K. C., Assal A., Lazar-Molnar E., Yao Y., Zang X. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2015;21(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keir M. E., Butte M. J., Freeman G. J., Sharpe A. H. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annual Review of Immunology. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmeyer K. A., Jeon H., Zang X. The PD-1/PD-L1 (B7-H1) pathway in chronic infection-induced cytotoxic T lymphocyte exhaustion. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/451694.451694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latchman Y., Wood C. R., Chernova T., et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(3):261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y., Cao Y., Yang X., et al. Effect of TLR4 and B7-H1 on Immune Escape of Urothelial Bladder Cancer and its Clinical Significance. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014;15(3):1321–1326. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.3.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwai Y., Ishida M., Tanaka Y., Okazaki T., Honjo T., Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(19):12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshimura A., Muto G. TGF-beta function in immune suppression. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2011;350:127–147. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee S., Khajanchi S., Chaudhuri S., Alonso M. M. A Mathematical Model to Elucidate Brain Tumor Abrogation by Immunotherapy with T11 Target Structure. PLoS ONE. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]