Abstract

Background:

The cesarean section rate (CSR) has been a main concern worldwide. The present study aimed to investigate the CSR in Beijing, China, and to analyze the related factors of CS delivery.

Methods:

An observational study was conducted in 15 medical centers in Beijing using a systemic cluster sampling method. In total, 15,194 pregnancies were enrolled in the study between June 20, 2013 and November 30, 2013. Independent t-tests and Pearson's Chi-square test were used to examine differences between two groups, and related factors of the CSR were examined by multivariable logistic regression.

Results:

The CSR was 41.9% (4471/10,671) in singleton primiparae. Women who were more than 35 years old had a 7.4-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with women <25 years old (odd ratio [OR] = 7.388, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 5.561–9.816, P < 0.001). Prepregnancy obese women had a 2-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with prepregnancy normal weight women (OR = 2.058, 95% CI = 1.640–2.584, P < 0.001). The excessive weight gain group had a 1.4-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with the adequate weight gain group (OR = 1.422, 95% CI = 1.289–1.568, P < 0.001). Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) women and DM women had an increased risk of CS delivery (1.2- and 1.7-fold, respectively) compared with normal blood glucose women. Women who were born in rural areas had a lower risk of CS delivery than did those who were born in urban areas (OR = 0.696, 95% CI = 0.625–0.775, P < 0.001). The risk of CS delivery gradually increased with a decreasing education level. Neonates weighing 3000–3499 g had the lowest CSR (36.2%). Neonates weighing <2500 g had a 2-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with neonates weighing 3000–3499 g (OR = 2.020, 95% CI = 1.537–2.656, P < 0.001). Neonates weighing ≥4500 g had an 8.3-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with neonates weighing 3000–3499 g (OR = 8.313, 95% CI = 4.436–15.579, P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Maternal age, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, blood glucose levels, residence, education level, and singleton fetal birth weight are all factors that might significantly affect the CSR.

Keywords: Blood Glucose Levels, Cesarean Section Rate, Gestational Weight Gain, Prepregnancy Body Mass Index, Related Factors

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean section rate (CSR) has been a main concern worldwide in the recent decades. In 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested a CSR approximately 15% as being appropriate.[1] CSs can reduce maternal/neonatal mortality, but overuse may be associated with an increased risk of severe maternal outcomes, such as increased risk of death, Intensive Care Unit admission, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy.[2]

According to a large cross-sectional study conducted in 24 countries around the world between 2004 and 2008 by the World Health Organization Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health,[2] Chinese health facilities had the highest CSR of 46.2%, while the rate was 25.7% in Asia. A recent study showed that, between 2008 and 2014, the overall annual rate of cesarean deliveries increased in China, reaching 34.9%,[3] but there was major geographic variation in the rates and trends over time, with the rates declining in some of the largest urban areas.

Chinese health-care providers have recognized this problem and made great efforts in the recent years, the rate of CS has shown a downward trend in some hospitals.[4]

The purpose of this study was to investigate the CSR in Beijing, analyze the related factors, and attempt to identify ways to lower the CSR.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital (No. 2013[578]). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients prior to their enrollment in this study.

Study population

The sampling frame for this study consisted of all public hospitals that offer delivery services in Beijing. Random seed and sampling intervals were chosen and sorted by the number of deliveries in 2012; 15 hospitals in Beijing were chosen as clusters by a systemic cluster sampling method (listed in the acknowledgments). There were 2 specialist hospitals and 13 general hospitals as well as 8 tertiary hospitals and 7 secondary hospitals, which well represented the hospitals in Beijing. The eligibility criteria included all women delivering after 28 weeks of pregnancy between June 20 and November 30, 2013. The exclusion criteria were as follows: missing data on major items, such as 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) results, birth weight, gestational age, and delivery mode.

The study developed a questionnaire to collect and record the data, including the high risk factors of CS delivery, such as maternal age, prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), gestational weight gain (GWG), blood glucose levels, residence, average monthly income, education level, and fetal birth weight.

Definitions

Gestational diabetes mellitus

GDM is diagnosed when any one value met or exceeded 5.1 mmol/L at 0 h, 10.0 mmol/L at 1 h, or 8.5 mmol/L at 2 h in the OGTT at 24–28 weeks. The gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) diagnostic criteria followed the new guideline established from 2011 in China.[5]

Prepregnancy body mass index categories

According to the standard of the Working Group on Obesity in China,[6] the prepregnancy BMI categories were classified as follows: underweight, BMI <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, 18.5≤ BMI ≤23.9 kg/m2; overweight, 24≤ BMI ≤27.9 kg/m2; and obese, BMI ≥28 kg/m2.

Guidelines for excessive gestational weight gain during pregnancy

According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM),[7] underweight women (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) should gain 12.5–18 kg; normal weight women (18.5≤ BMI ≤24.9 kg/m2) should gain 11.5–16 kg; overweight women (25≤ BMI ≤29.9 kg/m2) should gain 7–11.5 kg; and obese women (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) should gain 5–9 kg. According to each BMI category, GWG less than the lower limit is defined as inadequate weight gain, more than the upper limit is defined as excessive weight gain, and within the limits is defined as adequate weight gain.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were tested by independent t-tests. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages; Pearson's Chi-square test was applied to examine differences between the groups. Related factors of the CSR were examined by multivariable logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Maternal characteristics

In this study, we enrolled 15,194 women in the initial sample, of which 14,941 women had singleton pregnancies and 253 women had multiple pregnancies; in addition, 10,824 were nulliparous and 4370 were multiparous. Compared with the singleton pregnancy group, the multiple birth group had a significantly higher risk of CSR (42.5% vs. 85.8%, P < 0.001). For the multiparous women, one of the main causes of CS was a history of CS, might have biased the conclusion. Therefore, we excluded the multiple birth group and the multiparous group and performed the following calculations for the 10,671 singleton primiparae.

In the 10,671 singleton primiparae, the mean age of the women was 27.6 ± 4.0 years, and the mean gestational age was 39.1 ± 1.6 weeks. Of the 4471 women who delivered their infants by CS, the CSR was 41.9%.

For the 10,671 singleton primiparae, the demographic data of continuous variables comparing the CS delivery and vaginal delivery groups are shown in Table 1, including maternal age, gestational weeks, prepregnancy BMI, GWG during pregnancy, and fetal birth weight. We found that the CS delivery group had a higher maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, GWG, and fetal birth weight, and that the vaginal delivery group had a higher gestational age.

Table 1.

Comparison of maternal age, gestational weeks, and other demographic data of the samples in CS delivery and vaginal delivery groups

| Variables | CS delivery (n = 4471) | Vaginal delivery (n = 6200) | t | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Values | n | Values | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 4471 | 28.4 ± 4.3 | 6200 | 27.0 ± 3.7 | −17.170 | <0.001 |

| Gestational weeks | 4471 | 38.9 ± 1.7 | 6200 | 39.2 ± 1.5 | 7.028 | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 4431 | 22.1 ± 3.5 | 6162 | 21.0 ± 2.9 | −17.308 | <0.001 |

| GWG (kg) | 4209 | 16.5 ± 5.6 | 5848 | 15.7 ± 5.0 | −7.476 | <0.001 |

| Fetal birth weight (g) | 4471 | 3401.5 ± 537.8 | 6200 | 3313.3 ± 413.6 | −9.183 | <0.001 |

Data were shown as mean ± SD. CS: Cesarean section; BMI: Body mass index; GWG: Gestational weight gain; SD: Standard deviation.

Risk factors for cesarean section delivery

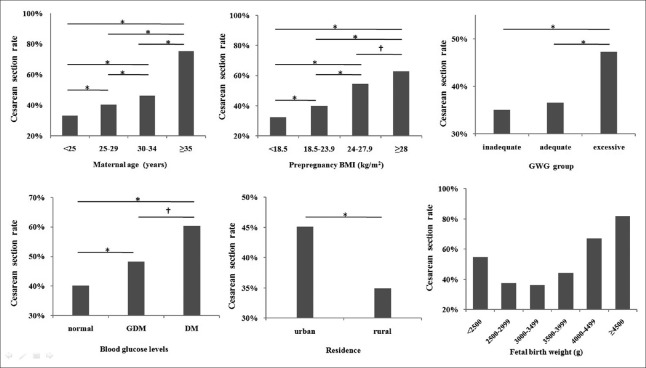

Data of the 10,671 singleton primiparae were used to analyze the related factors of CS delivery. We used CS delivery as the dependent variable and eight categorical variables as independent variables to perform the single-factor analysis. The eight categorical variables included were as follows: maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, GWG, blood glucose levels, residence, average monthly income, education level, and fetal birth weight [Figure 1 and Table 2]. Except for one variable (average monthly income) with no significant difference, all the other variables presented with P < 0.05. In total, 9453 cases without missing information were included in the logistic regression analysis. Using the enter method in the logistic regression, all seven variables were statistically significant. Hence, we considered the related factor of CS delivery to be maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, GWG, blood glucose level, residence, education level, and singleton fetal birth weight.

Figure 1.

Cesarean section rate and related factors in single-factor analysis. *P < 0.001; †P < 0.05. In the fetal birth weight (g) chart, except for group 2500–2999 g and group 3000–3499 g, all the other two groups had P < 0.05. BMI: Body mass index; GWG: Gestational weight gain; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; DM: Diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Single-factor analysis of the related factors of CSR

| Variables | Total number (missing) | CS delivery, n (%) | Vaginal delivery, n (%) | CSR (%) | Statistics | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | −14.688* | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 years | 10,671 (0) | 759 (17.0) | 1528 (24.6) | 33.2 | ||

| 25–29 years | 2052 (45.9) | 3055 (49.3) | 40.2 | |||

| 30–34 years | 1282 (28.7) | 1493 (24.1) | 46.2 | |||

| ≥35 years | 378 (8.5) | 124 (2.0) | 75.3 | |||

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | −14.969* | <0.001 | ||||

| <18.5 | 10,593 (78) | 514 (11.6) | 1074 (17.4) | 32.4 | ||

| 18.5–23.9 | 2839 (64.1) | 4256 (69.1) | 40.0 | |||

| 24–27.9 | 799 (18.0) | 666 (10.8) | 54.5 | |||

| ≥28 | 279 (6.3) | 166 (2.7) | 62.7 | |||

| GWG group | −11.094* | <0.001 | ||||

| Inadequate | 10,039 (632) | 530 (12.6) | 978 (16.8) | 35.1 | ||

| Adequate | 1245 (29.6) | 2158 (37.0) | 36.6 | |||

| Excessive | 2426 (57.7) | 2702 (46.3) | 47.3 | |||

| Blood glucose levels | 64.377† | <0.001 | ||||

| Normal | 10,671 (0) | 3405 (76.2) | 5092 (82.1) | 40.1 | ||

| GDM | 987 (22.1) | 1056 (17.0) | 48.3 | |||

| DM | 79 (1.8) | 52 (0.8) | 60.3 | |||

| Education | −2.561* | 0.010 | ||||

| Graduate and above | 10,012 (659) | 470 (11.1) | 690 (11.9) | 40.5 | ||

| College | 2703 (64.0) | 3470 (59.9) | 43.8 | |||

| High school | 617 (14.6) | 890 (15.4) | 40.9 | |||

| Junior school or lower | 433 (10.3) | 739 (12.8) | 36.9 | |||

| Residence | 95.935† | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban | 10,620 (51) | 3310 (74.3) | 4032 (65.4) | 45.1 | ||

| Rural | 1145 (25.7) | 2133 (34.6) | 34.9 | |||

| Average monthly income (RMB, Yuan) | −1.106* | 0.269 | ||||

| <1000 | 10,140 (531) | 2918 (68.3) | 4.65 (69.3) | 41.8 | ||

| 1000–2999 | 1268 (29.7) | 1686 (28.7) | 42.9 | |||

| 3000–4999 | 82 (1.9) | 107 (1.8) | 43.4 | |||

| ≥5000 | 6 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) | 42.9 | |||

| Fetal birth weight (g) | −10.969* | <0.001 | ||||

| <2500 | 10,671 (0) | 204 (4.6) | 168 (2.7) | 54.8 | ||

| 2500–2999 | 582 (13.0) | 976 (15.7) | 37.4 | |||

| 3000–3499 | 1681 (37.6) | 2969 (47.9) | 36.2 | |||

| 3500–3999 | 1447 (32.4) | 1831 (29.5) | 44.1 | |||

| 4000–4499 | 490 (11.0) | 241 (3.9) | 67.0 | |||

| ≥4500 | 67 (1.5) | 15 (0.2) | 81.7 |

*Statistics shown as Z; † Statistics shown as χ2. CS: Cesarean section; CSR: Cesarean section rate; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; DM: Diabetes mellitus; BMI: Body mass index; GWG: Gestational weight gain.

As shown in Table 3, we found that the CSR increased with age. Women who were more than 35 years old had a 7.4-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with women <25 years old (odds ratio [OR] = 7.388, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 5.561–9.816, P < 0.001). As the prepregnancy BMI increased, the CSR increased accordingly; prepregnancy obese women had a 2-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with prepregnancy normal weight women (OR = 2.058, 95% CI = 1.640–2.584, P < 0.001). When we divided the women by GWG group during pregnancy, the inadequate weight gain group had a similar CSR to the adequate weight gain group (OR = 0.926, 95% CI = 0.804–1.065, P = 0.281), but the excessive weight gain group had a 1.4-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with the adequate weight gain group (OR = 1.422, 95% CI = 1.289–1.568, P < 0.001). Compared with the normal blood glucose women, the GDM women and DM women had an increased risk of CS delivery (1.2- and 1.7-fold, respectively). Women who were born in rural areas had a lower risk of CS delivery than those who were born in urban areas (OR = 0.696, 95% CI = 0.625–0.775, P < 0.001). The risk of CS delivery gradually increased with the decrease in education level; women graduating from junior school or lower had a higher risk of CS delivery than did women graduating from graduate school and above (OR = 1.403, 95% CI = 1.380–1.729, P < 0.001). The relationship between fetal birth weight and CS delivery appeared to be like a “U shape”: neonates weighing 3000–3499 g had the lowest CSR, the farther away from this weight group (more or less), the higher the CSR was. Neonates weighing <2500 g had a 2-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with neonates weighing 3000–3499 g (OR = 2.020, 95% CI = 1.537–2.656, P < 0.001), and neonates weighing ≥4500 g had an 8.3-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with neonates weighing 3000–3499 g (OR = 8.313, 95% CI = 4.436–15.579, P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the related factors of CSR

| Variables | β | SE | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 years | 1.000 | ||||

| 25–29 years | 0.232 | 0.064 | <0.001 | 1.261 | 1.113–1.428 |

| 30–34 years | 0.507 | 0.073 | <0.001 | 1.660 | 1.440–1.913 |

| ≥35 years | 2.000 | 0.145 | <0.001 | 7.388 | 5.561–9.816 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | ||||

| <18.5 | −0.156 | 0.065 | 0.017 | 0.856 | 0.753–0.972 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 1.000 | ||||

| 24–27.9 | 0.449 | 0.065 | <0.001 | 1.567 | 1.380–1.780 |

| ≥28 | 0.722 | 0.116 | <0.001 | 2.058 | 1.640–2.584 |

| GWG group | <0.001 | ||||

| Inadequate | −0.077 | 0.072 | 0.281 | 0.926 | 0.804–1.065 |

| Adequate | 1.000 | ||||

| Excessive | 0.352 | 0.050 | <0.001 | 1.422 | 1.289–1.568 |

| Blood glucose levels | <0.001 | ||||

| Normal | 1.000 | ||||

| GDM | 0.187 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 1.206 | 1.079–1.348 |

| DM | 0.541 | 0.209 | 0.010 | 1.717 | 1.140–2.587 |

| Residence | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban | 1.000 | ||||

| Rural | −0.362 | 0.055 | <0.001 | 0.696 | 0.625–0.775 |

| Education | 0.005 | ||||

| Graduate and above | 1.000 | ||||

| College | 0.219 | 0.071 | 0.002 | 1.244 | 1.082–1.431 |

| High school | 0.290 | 0.093 | 0.002 | 1.336 | 1.112–1.605 |

| Junior school or lower | 0.338 | 0.107 | 0.002 | 1.403 | 1.138–1.729 |

| Fetal birth weight (g) | <0.001 | ||||

| <2500 | 0.703 | 0.140 | <0.001 | 2.020 | 1.537–2.656 |

| 2500–2999 | 0.094 | 0.067 | 0.163 | 1.098 | 0.963–1.253 |

| 3000–3499 | 1.000 | ||||

| 3500–3999 | 0.287 | 0.051 | <0.001 | 1.332 | 1.205–1.472 |

| 4000–4499 | 1.201 | 0.091 | <0.001 | 3.322 | 2.777–3.974 |

| ≥4500 | 2.118 | 0.320 | <0.001 | 8.313 | 4.436–15.579 |

| Constant | −1.246 | 0.099 | <0.001 | 0.288 |

BMI: Body mass index; GWG: Gestational weight gain; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; DM: Diabetes mellitus. CS: Cesarean section; CSR: Cesarean section rate; OR: Odd ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The rate of CS in this study was 41.9%, which was lower than that in other studies in urban areas, namely, 65.6% in a study in Tianjin[8] from 2009 to 2011 and 64.1% in 2008 in a national cross-sectional survey.[9] However, 41.9% was still a very high value. In the present study, we found some factors influencing the CSR. Maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, GWG, blood glucose levels, residence, education level, and singleton fetal birth weight were all factors that significantly affected the CSR.

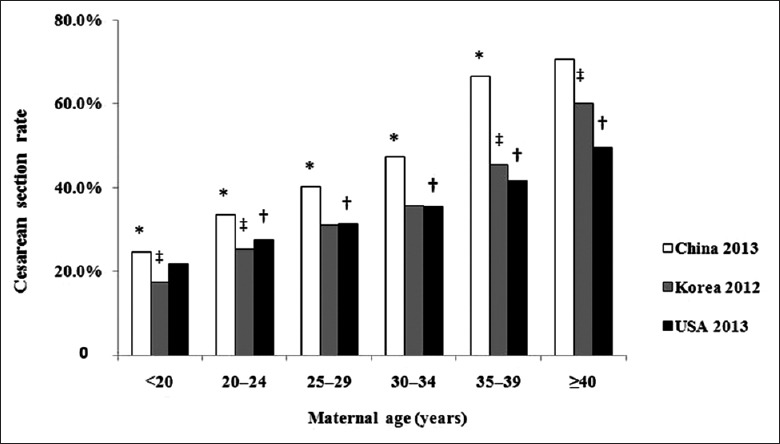

The CSR increased with maternal age, and the same trend has been found in Korea[10] and the USA[11] [Figure 2], as the total CSR was 36% in Korea in 2012 and 32.7% in the USA in 2013. Older maternal age was one of the reasons for the increased CSR because it increased the development of maternal diseases, which increased ante- and intra-partum complications. In a study in England,[12] there was an 80% increase in the number of women over the age of 40 years between 2006 and 2011, and the overall CSR increased from 34.6% in 2006 to 53.7% in 2011, comprising an increase in both elective and emergency cesarean sections. Subsequent to the implementation of the two-child policy in 2015 in China, we are facing the same problem now and must pay more attention to the complications of older maternal age, including the CSR.

Figure 2.

Relationship between cesarean section rate and maternal age in China, Korea, and the USA. *P < 0.05, China 2013 group versus Korea 2012 group; †P < 0.05, USA 2013 group versus China 2013 group; ‡P < 0.05, Korea 2012 group versus USA 2013 group.

Overweight people are at increased risk for chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Overweight or obesity before/during pregnancy might have an influence on both mother and child. Previous investigations have found a positive association between maternal prepregnancy BMI and cesarean delivery.[13,14,15] A study showed that a nulliparous woman with a BMI >30 kg/m2 is six times more likely to have a cesarean delivery than is a nulliparous woman whose BMI was <20 kg/m2;[16] the data showed that women whose BMI is ≥28 kg/m2 have a 2.1-fold increased risk of CS delivery compared with women whose BMI is between 18.5 and 24 kg/m2. Data of 292,568 cases from 1993 to 2005 in China reveal that maternal overweight and a high GWG or a GWG above the IOM recommendation is associated with adverse outcomes, such as hypertensive disorders complicating the pregnancy, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and large-for-gestational-age infants.[17] We also found that maternal obesity was closely related to the CSR; the excessive weight gain group had a much higher CSR than did the adequate weight gain group and the inadequate weight gain group. Health-care providers should inform women that maintaining a proper weight before pregnancy and achieving adequate weight gain during pregnancy will help to reduce the CSR.

Compared with normal blood glucose women, GDM women and DM women had a much higher CSR (40.1%, 48.3%, and 60.3%, respectively; all P < 0.001). It is well established that GDM is associated with a number of adverse outcomes;[18] CSR is just one of these. The incidence of GDM has risen from 2–6% to 15–20%;[19] how to maintain a proper blood glucose level during pregnancy has become more important,[20] as it will concurrently lower the CSR.

Some studies have shown that CSs without medical indications may have contributed to the high CSR,[21,22,23] and the introduction of the one-child policy in 1979 may be one of the reasons. Parents who expect to have only one child might prefer a CS to vaginal delivery because it is free from pain and anxiety. However, since 2015, in which the two-child policy was inducted, more parents are inclined to have two children, and thus, they prefer a vaginal delivery for their first child. In the recent years, the CSR in primiparae might be lower. However, there are still a considerable number of women with a CS history who want to have their second child, and most of them will again choose a CS. Therefore, reducing the primary CSR is the most important way of decreasing the CSR.[24]

Undoubtedly, there were some limitations in this study. In the multiparous women, one of the main reasons for a CS delivery was a previous CS delivery history, but this factor was not properly incorporated at the beginning of the study; consequently, we did not obtain accurate data regarding the previous CS delivery history. Hence, we only performed the analysis in singleton primiparae. This shortcoming will be rectified in future studies.

In conclusion, maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, GWG, blood glucose levels, residence, education level, and singleton fetal birth weight are all factors that might significantly affect the CSR. Maintaining a fetal birth weight from 3000–3499 g yielded the lowest CSR.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by grants from the World Diabetes Foundation (No. WDF 10-517 and No. WDF 14-908).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following 15 hospitals that participated in the study: Tongzhou Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Beijing, Peking University First Hospital, Peking University Third Hospital, Aviation General Hospital, Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital of the Beijing Military Region, Navy General Hospital, Beijing Hospital of Chinese Traditional and Western Medicine, Pinggu District Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Beijing, Beijing Daxing District Hongxing Hospital, Beijing Chuiyangliu Hospital, Miyunxian Hospital, Peking University Shougang Hospital, Changping District Hospital of Chinese Traditional Medicine, Beijing Jingmei Group General Hospital, and Beijing No. 6 Hospital.

Footnotes

Edited by: Peng Lyu

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;2:436–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92750-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: The WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet. 2010;375:490–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li HT, Luo S, Trasande L, Hellerstein S, Kang C, Li JX, et al. Geographic variations and temporal trends in cesarean delivery rates in China, 2008-2014. JAMA. 2017;317:69–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18663. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Wang X, Zou L, Ruan Y, Zhang W. An analysis of variations of indications and maternal-fetal prognosis for caesarean section in a tertiary hospital of Beijing: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5509. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005509. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang HX. Diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (WS 331-2011) Chin Med J. 2012;125:1212–3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.07.004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Lu FC Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004;17(Suppl):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain during Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li N, Liu E, Guo J, Pan L, Li B, Wang P, et al. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy outcomes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng XL, Xu L, Guo Y, Ronsmans C. Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:30–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.090399. 39A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.090399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung SH, Seol HJ, Choi YS, Oh SY, Kim A, Bae CW. Changes in the cesarean section rate in Korea (1982-2012) and a review of the associated factors. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:1341–52. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1341. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: Final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore EK, Irvine LM. The impact of maternal age over forty years on the caesarean section rate: Six year experience at a busy district general hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:238–40. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.838546. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.838546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahratian A, Siega-Riz AM, Savitz DA, Zhang J. Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity and the risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous women. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.02.005. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deruelle P, Servan-Schreiber E, Riviere O, Garabedian C, Vendittelli F. Does a body mass index greater than 25kg/m2 increase maternal and neonatal morbidity? A French historical cohort study. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.06.007. pii: S2468-784730152-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong C, Zhou A, Cao Z, Zhang Y, Qiu L, Yao C, et al. Association of pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain with cesarean section in term deliveries of China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37168. doi: 10.1038/srep37168. doi: 10.1038/srep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young TK, Woodmansee B. Factors that are associated with cesarean delivery in a large private practice: The importance of prepregnancy body mass index and weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:312–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126200. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Dai W, Dai X, Li Z. Prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy: A 13-year study of 292,568 cases in China. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:905–11. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2403-6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wendland EM, Torloni MR, Falavigna M, Trujillo J, Dode MA, Campos MA, et al. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes – A systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu WW, Yang HX, Wang C, Su RN, Feng H, Kapur A. High prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Beijing: Effect of maternal birth weight and other risk factors. Chin Med J. 2017;130:1019–25. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.204930. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.204930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song G, Wang C, Yang HX. Diabetes management beyond pregnancy. Chin Med J. 2017;130:1009–11. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.204938. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.204938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Liu Y, Meikle S, Zheng J, Sun W, Li Z. Cesarean delivery on maternal request in Southeast China. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1077–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816e349e. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816e349e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Landon MB, Cheng W, Chen Y. Cesarean delivery on maternal request in China: What are the risks and benefits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:817.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.043. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stützer PP, Berlit S, Lis S, Schmahl C, Sütterlin M, Tuschy B. Elective caesarean section on maternal request in Germany: Factors affecting decision making concerning mode of delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:1151–6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4349-1. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College); Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]