Abstract

Background:

Cerebral arteriovenous malformation (cAVM) is a type of vascular malformation associated with vascular remodeling, hemodynamic imbalance, and inflammation. We detected four angioarchitecture-related cytokines to make a better understanding of the potential aberrant signaling in the pathogenesis of cAVM and found useful proteins in predicting the risk of cerebral hemorrhage.

Methods:

Immunohistochemical analysis was conducted on specimens from twenty patients with cAVM diagnosed via magnetic resonance imaging and digital subtraction angiography and twenty primary epilepsy controls using antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Western blotting and real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed to determine protein and mRNA expression levels. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS expression levels increased in patients with cAVM compared with those in normal cerebral vascular tissue, as determined by immunohistochemical analysis. In addition, Western blotting and real-time PCR showed that the protein and mRNA expression levels of VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS were higher in the cAVM group than in the control group, all the differences mentioned were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS are upregulated in patients with cAVM and might play important roles in angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, and migration in patients with cAVM. MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS might be potential excellent group proteins in predicting the risk of cerebral hemorrhage at arteriovenous malformation.

Keywords: Angioarchitecture-related Factors, Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase, Matrix Metalloproteinase-9, Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2

INTRODUCTION

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) are important factors involved in vascular construction, vascular remodeling, and inflammation. Here, we investigated the expression and activation of these proteins in cerebral arteriovenous malformation (cAVM).

cAVM is a congenital vascular malformation in which arterial blood flow is directly connected to veins without a normal intervening capillary bed. These shunt vessels have very low resistance and thus lead to altered cerebral hemodynamics, which might cause hemorrhagic stroke, epilepsy, focal neurological deficit, and other symptoms. Intracranial hemorrhage is the most common clinical presentation of cAVM. Moreover, hemorrhage is associated with long-term neurological morbidity and mortality rates as high as 35% and 29%, respectively.[1,2] However, few studies have evaluated the mechanisms underlying the development of cAVM.

The occurrence, development, and spontaneous regression of cAVM are related to vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and remodeling of cerebral blood vessels.[3,4] Thus, the expression of cytokines associated with vascularization may be critical for the disease progression.[5,6] In the central nervous system, angiogenesis-related factors are involved in various pathophysiological processes, for example, cerebral ischemia, vascular malformation, and brain tumors. More than 19 angiogenesis-related factors and 300 angiogenesis inhibitory factors have proven to control the three mechanisms of vascularization (i.e., vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and arteriogenesis).[7,8,9] Recent achievements in vascular biology have revealed that some bioactive substances are critical for angiogenesis, vascular construction, proliferation, and degeneration.

Accordingly, in this study, we evaluated the expression levels of these substances in patients with cAVM to determine their roles in the pathogenesis of cAVM and to develop the improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for cAVM.

METHODS

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained for human sample collection from the Ethics Committee at our hospital (No. 2014200H [R2]) on March 6, 2015. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Tissue sample collection

Twenty arteriovenous malformation specimens from 12 men and 8 women with an average age of 36.8 years (19–55 years) were collected in two hospitals (Guangdong General Hospital and Nan Fang Hospital) from September 2013 to July 2015. None were treated previously by endovascular intervention, microsurgery, or radiation therapy. Hemorrhage, repeated epilepsia, and headache were the first signs of these patients who were diagnosed via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, Netherlands) and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). All patients had Spetzler-Martin Grade I-III lesion and the diagnosis was confirmed with MRI (Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, Netherlands) and DSA (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Control specimens were vascular tissues obtained from twenty patients undergoing surgery for primary epilepsy. The control patients included 13 men and 7 women with ages between 13 and 58 years and a mean age of 31.6 years. No tumor, cavernous hemangioma, hippocampal sclerosis, and inflammation were detected by enhanced magnetic resonance scans for these primary temporal epilepsy patients. All specimens collected were immediately frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen until use. All experiments were performed at medical research center of Guangdong General Hospital.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were fixed with immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature. Tissue samples were then paraffin embedded and deparaffinized in xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and hydrated in a series of the graded alcohol. The sections were then immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 20 min at room temperature to abolish endogenous peroxidase activities, and then antigen was retrieved undering microwave for 15 min before they were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C for 20 min. Slides were incubated with various primary antibodies including anti-VCAM-1 (Abcam, CA, USA), anti-VEGFR-2 (Abcam, CA, USA), anti-eNOS (Abcam, CA, USA), and anti-MMP-9 (Abcam, CA, USA). These antibodies were the same as those used in Western blotting. Two experienced pathologists assessed the immunostaining in a blinded fashion. Immunohistochemical staining was evaluated semiquantitatively by measuring the extent of staining (0, 0; 1, 6–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%, and 4, >75%) as well as the intensity of staining (0, no staining; 1, yellow; 2, brown to yellow; and 3, brown). Five ×400 visual fields were randomly selected from each immunohistochemical staining section, and the scores for each case according to the intensity and extent of staining were multiplied to obtain weighted scores (0, negative [−]; 1–4, weakly positive [+]; 5–8, moderately positive [++]; and 9–12, strongly positive [+++]). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted from tissues of twenty cAVM patients and twenty controls with a lysis buffer on ice. Of 50 μg protein extracts of each tissue sample was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12–15% acrylamide) and then electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated with VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, eNOS, and MMP-9 antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. Specific protein bands were visualized with the SuperSignal chemiluminescence system (Promega, WI, USA) and imaged by autoradiography. The quantitative analysis of band intensities was performed using Photoshop software (Adobe, CA, USA). Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from the tissues of twenty cAVM patients and twenty controls using TRIZOL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 1.0 ml of TRIZOL reagent and 200 μl of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to the sample, and the mixture was vortexed for 60 s and allowed to stand at 25°C for 5 min. After the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and 500 μl of isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added. After incubation at −20°C overnight, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the supernatant, and the RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol. After ethanol removal by centrifugation at 10,000 ×g for 10 min at 4°C, the RNA was air-dried for 5 min and then dissolved in 20 μl of RNase-free water.

Real-time fluorescent quantitative-polymerase chain reaction

Single-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using 2 mg of total RNA via reverse transcription (RT) reaction according to the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Promega, WI, USA). Real-time quantitative-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) in an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The assays were performed on forty samples (twenty cAVM and twenty controls) for four genes (VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, eNOS, and MMP-9) that met the defined criteria. Each reaction was performed in a 20 μl volume system containing 5 μl of cDNA, 0.5 μl of each primer, 10 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, and 4.0 μl of RNase-free water. The PCR program consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles each of denaturation for 15 s at 95°C and annealing and extension for 30 s at 60°C. The β-actin gene was used as a stable endogenous control for normalization. Average CT values for VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, eNOS, and MMP-9 were calculated and normalized to that for β-actin, and the normalized values were subjected to a 2−ΔΔCT formula to calculate the fold change between the control and experiment groups. All reactions were performed in triplicates. Primer sequence for real-time fluorescent quantitative-PCR analysis is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for real-time fluorescence quantitative-PCR analysis

| Gene | Forward and reverse primer sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| MMP-9 | TTCAGGGAGACGCCCATTTC |

| AAACCGAGTTGGAACCACGA | |

| VCAM-1 | GTCTCATTGACTTGCAGCACC |

| AGATGTGGTCCCCTCATTCGT | |

| VEGFR-2 | ACCCACGATCACAGGAAACC |

| ACATGATCTGTGGAGGGGGA | |

| eNOS | TGAGACCTTCTGTGTGGGAGAG |

| CGCTTCCAGCTCCGTTTGG |

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; MMP-9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9; VCAM-1: Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1; VEGFR-2: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Statistical analysis

Data explored the distribution and homogeneity of variance. If the data followed normal distribution with homogeneous variance, we used mean ± standard deviation (SD) to describe the data; otherwise, we used median (interquartile range) to describe the data. If the data followed normal distribution, independent t-test was performed in data analysis; otherwise, Wilcoxon t-test was used in data analysis. All statistical analyses of data were performed by SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, NY, USA). The significant level was set as 0.05 (α = 0.05), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

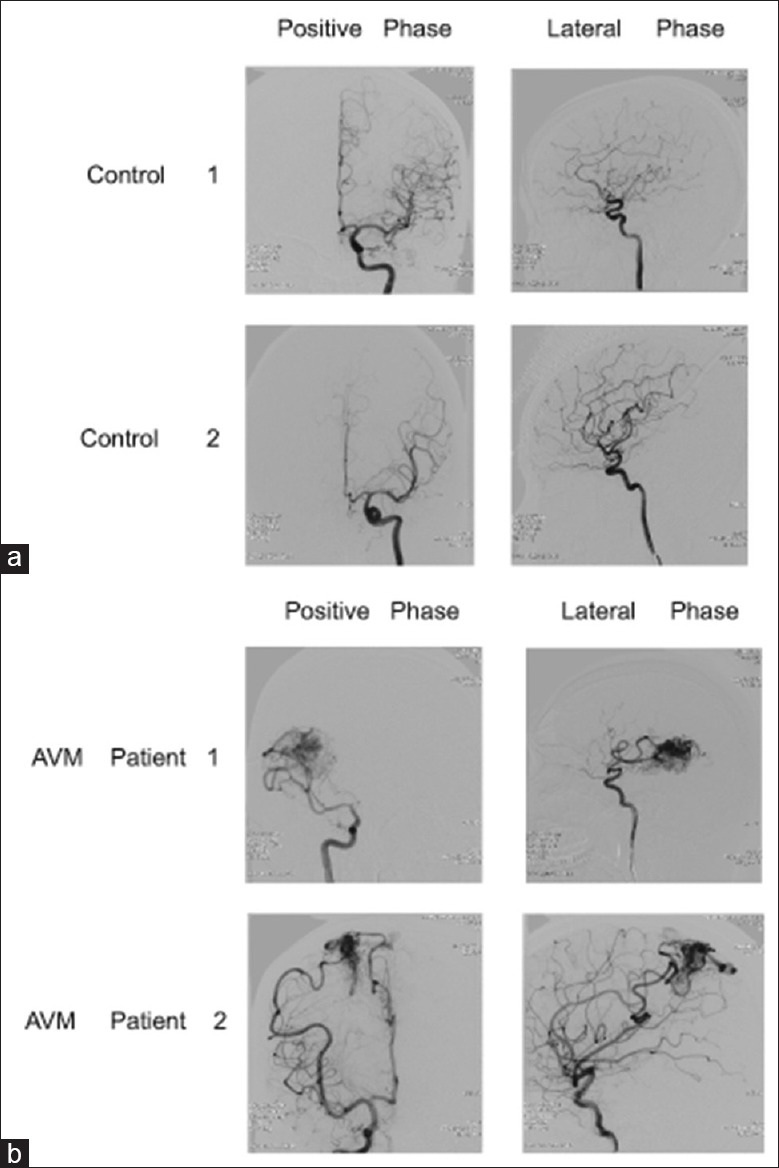

Clinical characteristics of the patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformation

All patients were diagnosed with cAVM based on DSA results [Figure 1] and clinical signs, including cerebral hemorrhage, epilepsy, headache, and localized nerve dysfunction. MRI and DSA images illustrated the location and size of the nidus, feeding arteries, and drainage veins. The nidus might be located in any part of the brain, for example, supratentorial, subtentorial, deep, or superficial. Moreover, the feeding arteries were dilated tortuously, and there were no capillary networks between the feeding arteries and drainage veins. Direct shunting from arteries to veins can lead to arterial steal syndrome, which might cause nerve dysfunction and headache. Among the initial clinical symptoms of these patients, nine patients had ruptured cAVM, five patients presented with seizures, and five with headaches. One patient had an incidental finding of cAVM. Clinical information of twenty cAVM patients is listed in Table 2. There were nine cases with bleeding, five cases with seizures, five cases with headache, and one case by chance. Clinical information of twenty cAVM patients is listed in Table 2. All patients were diagnosed with cAVM based on DSA results [Figure 1] and clinical signs, including cerebral hemorrhage, epilepsy, headache, and localized nerve dysfunction. MRI and DSA images illustrated the location and size of the nidus, feeding arteries, and drainage veins. The nidus may be located in any part of the brain, for example, supratentorial, subtentorial, deep, or superficial. Moreover, the feeding arteries were dilated tortuously, and there were no capillary networks between the feeding arteries and drainage veins. Direct shunting from arteries to veins can lead to arterial steal syndrome, which might cause nerve dysfunction and headache. Among the initial clinical symptoms of these patients, there were nine cases with bleeding, five cases with seizures, five cases with headache, and 1 case by chance. Clinical information of twenty cAVM patients is listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

DSA images of two patients with cAVM and two patients in the control group. (a) The anteroposterior view and lateral view of DSA imaging from two patients in the control group showed normal ACAs and MCAs. (b) The anteroposterior view and lateral view of DSA imaging from two patients with cAVM. In patient 1, the cAVM nidus located at the parietal lobe received blood supply from the right MCA branches. In patient 2, the nidus located at the frontal and parietal lobes received blood supply from the right MCA and ACA branches. ACAs: Anterior cerebral arteries; MCAs: Middle cerebral arteries; DSA: Digital subtraction angiography; cAVM: Cerebral arteriovenous malformation.

Table 2.

Clinical information of BAVM patients

| Patients | Gender | Age (years) | Clinical symptoms | Diagnosis and location | Spetzler-Martin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 51 | Sudden headache, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days | Left cerebellum AVM with bleeding | II |

| 2 | Male | 33 | Twitch repeatedly for 1 year | Right temporal AVM | II |

| 3 | Female | 49 | Headache and dizzy repeatedly for 2 years | Left parieto-occipital AVM | III |

| 4 | Male | 41 | Sudden headache for 3 days | Left occipital AVM with bleeding | II |

| 5 | Male | 29 | Twitch repeatedly for 2 months | Right temporal pole AVM | III |

| 6 | Female | 19 | Sudden headache for 1 days | Right frontal AVM with bleeding | III |

| 7 | Male | 38 | Recurrent seizures for 3 years | Left temporal AVM | I |

| 8 | Male | 34 | Headache for 6 years | Left occipital AVM | IV |

| 9 | Male | 24 | Sudden headache for 7 days | Right frontal AVM with bleeding | II |

| 10 | Female | 42 | Headache for 3 months | Left frontal AVM | II |

| 11 | Female | 26 | Sudden headache for 1 day | Right temporal AVM with bleeding | III |

| 12 | Male | 55 | Headache and dizzy for 6 months | Right frontal AVM | IV |

| 13 | Male | 27 | Headache for 5 days | Left cerebellum AVM with bleeding | II |

| 14 | Male | 33 | Sudden headache for 10 days | Left occipital AVM with bleeding | III |

| 15 | Female | 25 | No symptom | Right frontal AVM | III |

| 16 | Male | 44 | Recurrent seizures for 1 year | Left temporal AVM | I |

| 17 | Male | 39 | Sudden headache for 2 days | Right parietal AVM with bleeding | I |

| 18 | Female | 50 | Sudden headache for 5 days | Left temporal AVM with bleeding | III |

| 19 | Female | 37 | Headache for 2 months | Right cerebellum AVM | II |

| 20 | Male | 40 | Recurrent seizures for three times | Right frontal AVM | II |

AVM: Arteriovenous malformation; BAVM: Brain arteriovenous malformation.

Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2, matrix metalloproteinase-9, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase

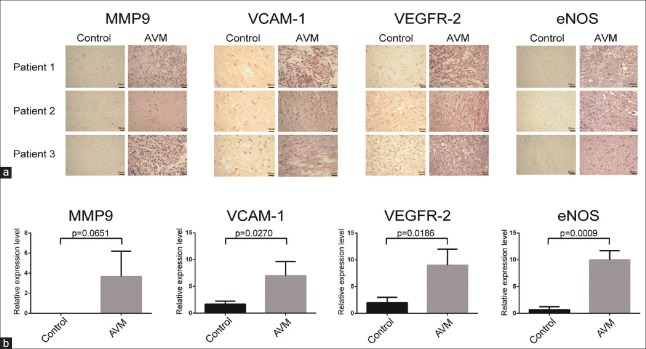

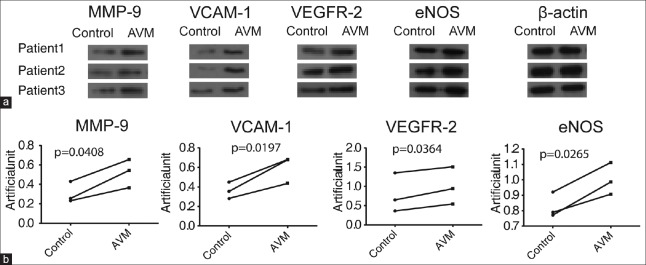

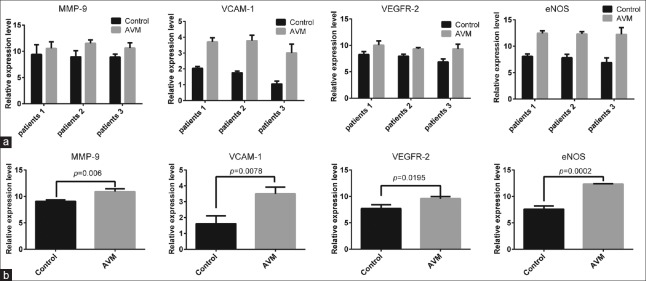

The immunohistochemical analysis showed that VEGFR-2 was expressed in the cell membrane and cytoplasm. In the normal cerebral tissue, the expression of VEGFR-2 was low in the artery endothelium, media, and adventitia. In the cAVM samples, similar low expression was observed in the vascular media and adventitia; however, the expression was high in the vascular endothelial tissues [Figure 2, t = 3.834, P = 0.0186]. Western blotting results confirmed that the expression level of VEGFR-2 was higher in the cAVM group than in the control group [Figure 3, t = 5.095, P = 0.0364]. Quantitative RT-PCR results showed that VEGFR-2 mRNA expression levels were significantly higher in the cAVM group than in the control group [Figure 4, t = 3.807, P = 0.0195].

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS in tissue samples from patients with cAVM. (a) The representative immunohistochemistry of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS in tissue samples from twenty patients with cAVM and twenty controls. (b) The relative expression level of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS protein. The scores for each case in A according to the intensity and extent of staining were multiplied to obtain weighted scores and t-test was used for statistical analysis. The four proteins (MMP-9, VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, and eNOS) were validated in twenty group samples (one control sample and one cAVM sample per group) by immunohistochemistry, and the same trend was observed in each group. Three of the twenty validated groups are shown. MMP-9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9; VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1;VEGFR-2: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; AVM: Arteriovenous malformation.

Figure 3.

Expression of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS proteins in tissue samples from patients with cAVM, as determined by Western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal loading control. (a) The representative Western blots of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS in tissue samples from twenty patients with cAVM and twenty controls. (b) The relative expression level of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS. T-test analysis of the band intensities in A. Band intensities in the same patient are linked. The four proteins (MMP-9, VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, and eNOS) were validated in twenty group samples (one control sample and one cAVM sample per group) by Western blotting, and similar trends were observed in each group. Three of the twenty validated groups are shown. MMP-9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9; VEGFR-2: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

Figure 4.

Expression of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS in tissue samples from patients with cAVM in mRNA levels. (a) The representative mRNA levels of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS in tissue samples from twenty patients with CAVM and twenty controls. (b) The relative mRNA level of MMP-9, VEGFR-2, VCAM-1, and eNOS. β-actin was used as a reference gene. mRNA expression was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCT method, and t-tests were used for statistical analysis. The four mRNAs (MMP-9, VCAM-1, VEGFR-2, and eNOS) were validated in twenty group samples (one control sample and one cAVM sample per group) by real-time quantitative PCR, and similar trends were observed in each group. Three of the twenty validated groups are shown. MMP-9: Matrix metalloproteinase-9; VEGFR-2: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2; VCAM-1: Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

The expression of MMP-9 was low in the endothelium, media, and adventitia of normal cerebral artery tissue. In cAVM samples, MMP-9 was expressed at low levels in the media but at higher levels in the vascular endothelium and adventitia [Figure 2, t = 2.524, P = 0.0651], similar to the results of Western blotting [Figure 3, t = 4.801, P = 0.0408] and qRT-PCR analysis [Figure 4, t = 5.151, P = 0.006].

Low levels of VCAM-1 expression were observed in the adventitia of microvessels and neovascularization. VCAM-1 expression was higher in cAVM tissues than in control tissues [Figure 2, t = 3.411, P = 0.027]. These results were also confirmed by Western blot analysis [Figure 3, t = 7.02, P = 0.0197] and qRT-PCR [Figure 4, t = 4.943, P = 0.0078].

Endothelial NOS was expressed in the cytomembrane, and minimal eNOS was detected in the endothelium, vascular media, and adventitia of normal cerebral artery tissue. In cAVM samples, the expression was low in the vascular media and adventitia, but high in the vascular endothelium [Figure 2, t = 8.854, P = 0.0009]. Western blot analysis also revealed a higher level of eNOS expression in cAVMs than in controls [Figure 3, t = 6.017, P = 0.0265], consistent with qRT-PCR results [Figure 4, t = 13.09, P = 0.0002].

DISCUSSION

cAVM is a congenital cerebrovascular disease caused by the abnormal cerebrovascular differentiation of the primeval embryo during early embryonic development. Normal capillaries between arteries and veins are insufficient, which can lead to varicose and complex cluster vessels with different vessel wall thicknesses. Other histopathological features include the deficient elastic fiber layer and varying degrees of hyaline degeneration and calcification as the pathological basis of cerebral cAVM hemorrhage.[10,11,12] The occurrence and remodeling of blood vessels are essential for the development and repair of the brain, which is controlled by the balance between angiogenic and anti-angiogenic pathways.

In this study, we demonstrated that cAVM might be related to abnormal regulation of the genes encoding VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS during the formation of the blood vessels. Recent studies investigating the biology of cAVM have focused on VEGF and its receptors.[13,14,15] Other cytokines, adhesion molecules, and glycoproteins, including transforming growth factor-β, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, angiopoietin, epidermal growth factor, and ephrins, are vital for the occurrence, development, and recurrence of cAVMs.[6,16] Since cAVM is caused by pathological cerebrovascular regulatory mechanisms, the main solution to prevent the formation of cAVM is the modulation of gene expression, leading to abnormal levels of angiogenesis-related factors.[17,18] In this study, we demonstrated that cerebral cAVM may be related to abnormal regulation of the genes encoding VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS during the formation of the blood vessels.

VEGF is a major modulator of angiogenesis and promotes the endothelial cell migration through the hypoxic environment in tumors.[19] Overexpression or exogenous administration of VEGF stimulates the synthesis of eNOS in a dose-dependent manner and hence results in a persistent increase in nitric oxide (NO) formation and vascularization with an increased vascular density.[20,21] Moreover, VEGF induces the production of proteases by the endothelial cells, resulting in blood vessel degradation, monocyte migration, and neutrophil-dependent artery formation.[22] The importance of VEGF in embryonic vascular development has been assessed by disrupting the VEGF gene, thereby impairing angiogenesis and blood island formation.[23,24] VEGF enhances vessel (mainly small capillary and vein) permeability to plasma protein without damaging endothelial cells or inducing mast cell degranulation and inflammatory reactions.[25,26] In our study, VEGFR-2 was considered the main transducer of VEGF-mediated angiogenic signals that promoted the permeability and dilation of blood vessels as well as the proliferation, invasion, migration, and survival of endothelial cells.[27,28] The expression of VEGFR-2 has been reported to be increased significantly in patients with cAVM compared with that in control brain tissues.[29]

MMP-9 is a Zn2+-dependent protease that functions in the degradation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. MMP-9 is responsible for cleaving and activating certain growth factors, such as VEGF.[30,31] High expression of MMP-9 results in a damage to the stability and integrity of blood vessels and a weakened blood-brain barrier, increasing the risk of hemorrhage.[32,33] Excessive expression of MMP-9 causes the connection between vascular endothelial cells to be too loose, resulting in a damage to the vascular adventitia and smooth muscle.[32,33] Moreover, MMP-9 increases the risk of cAVM hemorrhage because it is activated in cAVM tissues and causes the degradation of the abnormal vascular extracellular matrix.[34,35,36]

VCAM-1 is an Ig-superfamily type I transmembrane protein expressed mainly in endothelial cells during inflammation. VCAM-1 mediates leukocyte rolling and adhesion to the endothelium and promotes the transendothelial migration of leukocytes and vasculogenesis.[37] VCAM-1 is upregulated in cAVM, and the lesions being embolized appear to show stronger expression of VCAM-1 than the nonembolized lesions.[38] Modulation of the inflammatory response by VCAM-1 plays an important part in various processes, including endothelial cell death, cellular proliferation, and thrombosis in cAVM vessels.

NOS is a family of enzymes functioning to synthesize NO from l-arginine,[39] a powerful metabolite involved in vascular smooth muscle cell function, cerebral blood circulation, and edema induction. eNOS is expressed constitutively in endothelial cells and has key roles in angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Production of NO by eNOS inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, regulates blood vessel tone and hemodynamics, and modulates the interaction of the endothelium with leukocytes.[40] Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of eNOS protein was significantly increased in the endothelial cells from patients with cAVM compared with that in the normal subcutaneous skin tissues.[41]

The occurrence of cAVM may be related to some hemodynamic factors, such as pressure, increased flow velocity, or venous outflow obstruction.[42,43,44] The study showed that VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS were expressed at higher levels in cAVM patients than the controls. Therefore, we presumed that the increased expression of VEGFR-2, MMP-9, and VCAM-1 can destroy the stability and integrity of blood vessels. In addition, NO produced by eNOS might enhance the vasodilation and further increase the risk of hemorrhage. We tested the vascular tissues of twenty cAVM patients and found that the expression level of MMP-9 and VCAM-1 was higher in patients with cerebral hemorrhage compared with the patients without hemorrhage, which was consistent with our hypothesis. VCAM-1 and eNOS might also modulate the interaction between the endothelium and leukocytes, and stimulate excessive inflammation, causing perturbation of the stability and integrity of blood vessels.

In conclusion, VEGFR-2, MMP-9, VCAM-1, and eNOS were expressed at higher levels in cAVM patients than the normal cerebral vascular tissues. These four angioarchitecture-related cytokines have important roles in the angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, and migration in cAVM. They might represent the potential aberrant signaling in the pathogenesis of cAVM and might function as potential group proteins in predicting the risk of cerebral hemorrhage; however, the relationship of these factors is scarcely comprehensively evaluated. Our study revealed the expression level of the four factors based on the twenty patients with cAVM. More samples from the patients with and without hemorrhage will be collected to detect the expression of the four cytokines in further study, with a final aim to determine the correlation between the protein expression and cAVM with hemorrhage.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (No. 2014J4100042) and Science and Technology project of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2013B021B00179, 2015A020212025).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

REFERENCES

- 1.Gross BA, Du R. Natural history of cerebral arteriovenous malformations: A meta-analysis. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:437–43. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS121280. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.JNS121280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Costa L, Wallace MC, Ter Brugge KG, O’Kelly C, Willinsky RA, Tymianski M, et al. The natural history and predictive features of hemorrhage from brain arteriovenous malformations. Stroke. 2009;40:100–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524678. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Shahi R, Warlow C. A systematic review of the frequency and prognosis of arteriovenous malformations of the brain in adults. Brain. 2001;124:1900–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.1900. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdulrauf SI, Malik GM, Awad IA. Spontaneous angiographic obliteration of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:280–7. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199902000-00021. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James F, Thomas G, Robert D. Genetics of cerebrovascular disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:122–32. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)62969-8. doi: 10.4065/80.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buschmann I, Heil M, Jost M, Schaper W. Influence of inflammatory cytokines on arteriogenesis. Microcirculation. 2003;10:371–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800199. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zadeh G, Guha A. Angiogenesis in nervous system disorders. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1362–74. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000093425.98136.31. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000093425.98136.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neyazi B, Tanrikulu L, Wilkens L, Hartmann C, Stein KP, Dumitru CA, et al. Procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 expression in brain arteriovenous malformations and its association with brain arteriovenous malformation size. World Neurosurg. 2017;102:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.116. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu HZ, Qin ZY, Gu YX, Zhou P, Xu F, Chen XC, et al. Increased expression of osteopontin in brain arteriovenous malformations. Chin Med J. 2012;125:4254–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.23.017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donnell JM, Morgan MK, Heller GZ. The risk of seizure following surgery for brain arteriovenous malformation: A prospective cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2017 doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx101. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrigan MR. Angiogenic factors in the central nervous system. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:639–61. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000079575.09923.59. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000079575.09923.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gault J, Sarin H, Awadallah NA, Shenkar R, Awad IA. Pathobiology of human cerebrovascular malformations: Basic mechanisms and clinical relevance. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1–17. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000440729.59133.c9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sure U, Battenberg E, Dempfle A, Tirakotai W, Bien S, Bertalanffy H. Hypoxia-inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are expressed more frequently in embolized than in nonembolized cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:663–70. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000134556.20116.30. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000134556.20116.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koizumi T, Shiraishi T, Hagihara N, Tabuchi K, Hayashi T, Kawano T. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factors and their receptors in and around intracranial arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:117–26. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00020. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali C, Docagne F, Nicole O, Lesné S, Toutain J, Young A, et al. Increased expression of transforming growth factor-beta after cerebral ischemia in the baboon: An endogenous marker of neuronal stress? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:820–7. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00007. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, et al. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2626–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarençon F, Maizeroi-Eugène F, Bresson D, Maingreaud F, Sourour N, Couquet C, et al. Elaboration of a semi-automated algorithm for brain arteriovenous malformation segmentation: Initial results. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:436–43. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3421-5. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uranishi R, Nakase H, Sakaki T. Expression of angiogenic growth factors in dural arteriovenous fistula. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:781–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.5.0781. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.5.0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Berendsen AD, Jia S, Lotinun S, Baron R, Ferrara N, et al. Intracellular VEGF regulates the balance between osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3101–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI61209. doi: 10.1172/JCI61209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouloumié A, Schini-Kerth VB, Busse R. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates nitric oxide synthase expression in endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:773–80. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00228-4. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrigan MR, Ennis SR, Masada T, Keep RF. Intraventricular infusion of vascular endothelial growth factor promotes cerebral angiogenesis with minimal brain edema. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:589–98. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00030. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TH, Avraham H, Lee SH, Avraham S. Vascular endothelial growth factor modulates neutrophil transendothelial migration via up-regulation of interleukin-8 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10445–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107348200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–9. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–42. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Hollinger LA, Wolpert EB, Gardner TW. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces rapid phosphorylation of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occluden 1. A potential mechanism for vascular permeability in diabetic retinopathy and tumors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23463–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negrão R, Costa R, Duarte D, Gomes TT, Azevedo I, Soares R, et al. Different effects of catechin on angiogenesis and inflammation depending on VEGF levels. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:435–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.12.011. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cébe-Suarez S, Zehnder-Fjällman A, Ballmer-Hofer K. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:601–15. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5426-3. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K, Rossant J. Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature. 2005;438:937–45. doi: 10.1038/nature04479. doi: 10.1038/nature04479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uranishi R, Baev NI, Ng PY, Kim JH, Awad IA. Expression of endothelial cell angiogenesis receptors in human cerebrovascular malformations. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:359–67. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00024. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loftus IM, Naylor AR, Goodall S, Crowther M, Jones L, Bell PR, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity in unstable carotid plaques. A potential role in acute plaque disruption. Stroke. 2000;31:40–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.40. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feiler S, Plesnila N, Thal SC, Zausinger S, Schöller K. Contribution of matrix metalloproteinase-9 to cerebral edema and functional outcome following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:289–95. doi: 10.1159/000328248. doi: 10.1159/000328248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Zhu W, Bollen AW, Lawton MT, Barbaro NM, Dowd CF, et al. Evidence of inflammatory cell involvement in brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1340–9. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000333306.64683.b5. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000333306.64683.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Wang R, Wang X, Xue X, Ran D, Wang S, et al. Relevance of IL-6 and MMP-9 to cerebral arteriovenous malformation and hemorrhage. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:1261–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1332. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starke RM, Komotar RJ, Hwang BY, Hahn DK, Otten ML, Hickman ZL, et al. Systemic expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:343–8. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000363599.72318.BA. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000363599.72318.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alon R, Kassner PD, Carr MW, Finger EB, Hemler ME, Springer TA, et al. The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1243–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1243. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storer KP, Tu J, Karunanayaka A, Morgan MK, Stoodley MA. Inflammatory molecule expression in cerebral arteriovenous malformations. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.10.013. doi: 10.1016/S0924-4247(01)00719-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeishi Y. The nitric oxide synthase family and left ventricular diastolic function. Circ J. 2010;74:2556–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1069. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang PL. eNOS, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.005. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ying L, Hofseth LJ. An emerging role for endothelial nitric oxide synthase in chronic inflammation and cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1407–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shakur SF, Liesse K, Amin-Hanjani S, Carlson AP, Aletich VA, Charbel FT, et al. Relationship of cerebral arteriovenous malformation hemodynamics to clinical presentation, angioarchitectural features, and hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2016;63(Suppl 1):136–40. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001285. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spetzler RF, Hargraves RW, McCormick PW, Zabramski JM, Flom RA, Zimmerman RS, et al. Relationship of perfusion pressure and size to risk of hemorrhage from arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:918–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.6.0918. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.6.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kader A, Young WL, Pile-Spellman J, Mast H, Sciacca RR, Mohr JP, et al. The influence of hemodynamic and anatomic factors on hemorrhage from cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:801–7. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199405000-00003. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]