Introduction

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is a fat-soluble steroid hormone obtained from food sources and produced locally in the skin from the ultraviolet radiation (UVR)-dependent conversion of cholesterol precursors to the inactive form of vitamin D3 (Bikle, 2011). In addition to its classically described functions related to the regulation of calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism, vitamin D3 has numerous nonclassical effects, including the ability to modulate immune responses (Mora et al., 2008; Wobke et al., 2014). Specifically, vitamin D3 induces monocyte to macrophage differentiation, enhances antimicrobial activity, stimulates autophagy, and suppresses the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Liu et al., 2006; Fabri et al., 2011; Di Rosa et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). However, it was previously unknown whether vitamin D3 was capable of modulating acute inflammation in humans. In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot study, our group recently demonstrated that vitamin D3 reduces skin inflammation when administered to humans 1 h after sunburn (Scott et al., 2017). This commentary will attempt to outline the major clinical and biologic implications of using vitamin D as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic agent.

Clinical Implications

In our pilot study, vitamin D3 administered one hour after sunburn reduced skin redness, as well as the levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the skin, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Scott et al., 2017). Moreover, subjects with the largest rise in serum vitamin D3 levels after intervention demonstrated consistent upregulation of genes involved in skin repair and wound healing (Scott et al., 2017).

Importantly, the results from our study do not imply that photoprotective behaviors should now be substituted for high-dose vitamin D3. The practice of strict photoprotection, including the regular use of sunscreen, remains essential in preventing the acute and chronic effects of UVR, including sunburn, photocarcinogenesis, and photoaging (Lim et al., 2017; Young et al., 2017). Moreover, while frequent sunscreen use does not appear to decrease serum vitamin D3 levels or lead to vitamin D3 deficiency, UVR-mediated vitamin D3 production in the skin is associated with DNA damage (Linos et al., 2012; Petersen et al., 2014). As such, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends obtaining adequate vitamin D3 through supplementation rather than unprotected exposure to UVR (AAD, 2009).

In addition, vitamin D3 was administered to subjects in our study after sunburn had already occurred (Scott et al., 2017). Whether vitamin D3 can act in an anti-inflammatory manner when given before the development of sunburn remains an unanswered question. Moreover, DNA damage would have already occurred in the skin by the time vitamin D3 was administered. Immune surveillance is critical in eliminating DNA-damaged keratinocytes during the early stages of photocarcinogenesis, as evidenced by the increased risk for skin cancer in immunosuppressed transplant recipients, as well as the efficacy of proinflammatory immune modifiers for the treatment of premalignant skin lesions (Euvrard et al., 2003; Ooi et al., 2006; Cunningham et al., 2017). Given that vitamin D3 suppresses inflammation following sunburn, it is theoretically plausible that vitamin D3 may also limit the immune-mediated clearance of DNA-damaged keratinocytes, thus allowing them to survive, proliferate, and ultimately confer a greater risk for developing skin cancer.

The optimal dose and dosing frequency for vitamin D3 supplementation are also unclear, with specific recommendations varying by professional society (Holick et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2011). Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated a clinical benefit of supplementing with up to 500,000 international units (IU) of vitamin D3 annually, and supplementation doses ranging from 400 to 4000 IU/day are generally considered safe (Dawson-Hughes et al., 2010; Sanders et al., 2010; van Groningen et al., 2010). However, these recommendations are extrapolated from the benefits of vitamin D3 supplementation on bone health, and the ideal dosing strategy required to achieve immunomodulatory effects in vivo is still unknown (Sohl et al., 2015). We administered a one-time, postexposure vitamin D3 dose ranging from 50,000 to 200,000 IU and observed no adverse events during the duration of the study period (Scott et al., 2017). Serum calcium and vitamin D3 levels remained within the recommended reference range for all subjects throughout the duration of the study, supporting that single high doses of vitamin D3 are both safe and well tolerated as therapeutic interventions.

Finally, the pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of vitamin D3 is complex. An individual's response to a large bolus of vitamin D3 will depend on several factors, including body mass index (BMI), genetic polymorphisms, and baseline vitamin D3 stores, among others (Ilahi et al., 2008; Didriksen et al., 2013). Our study was not statistically powdered to match subjects by their baseline vitamin D3 levels, and subjects' baseline serum vitamin D3 levels ranged widely from 18.4 to 36.5 ng/mL (Scott et al., 2017). As a result, it remains unclear whether individuals with lower baseline stores require higher vitamin D3 doses to achieve therapeutic effects. Similarly, as BMI also varied widely from 21.3 to 41.6, it also remains unclear whether individuals with higher BMI require higher vitamin D3 doses due to the potential for distribution in adipose tissue (Scott et al., 2017). Therefore, the results of our pilot clinical trial will need to be replicated in larger, diverse populations of subjects before vitamin D3 can be recommended for its anti-inflammatory properties in routine clinical practice.

Biologic Implications

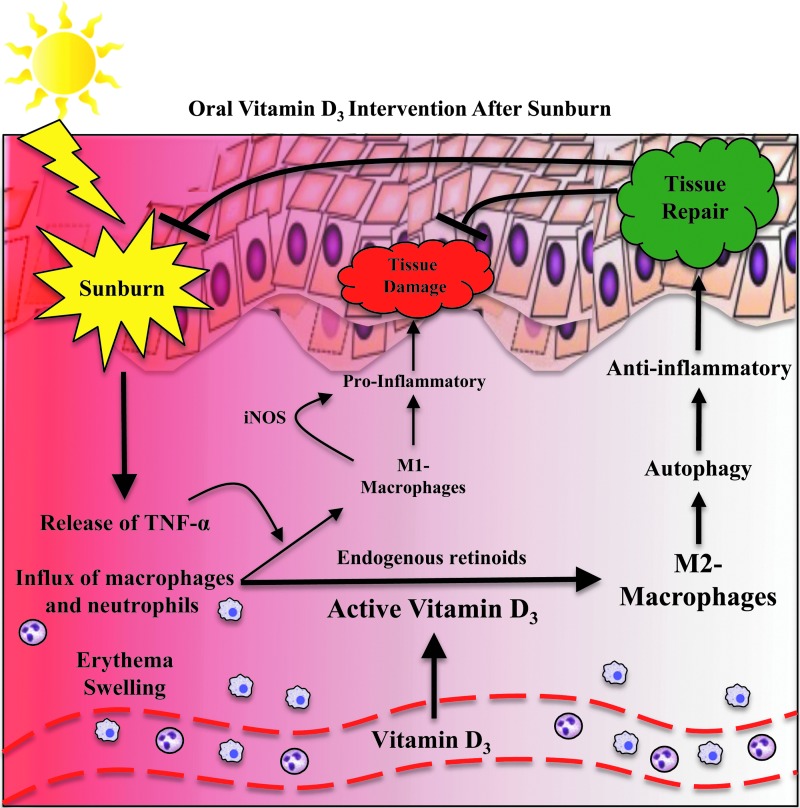

At the tissue level, sunburn results in vasodilation and dermal edema, which manifest clinically as erythema and swelling, respectively. At the cellular and molecular level, sunburn is characterized by an influx of neutrophils and macrophages into the skin, as well as the release of proinflammatory mediators, including TNF-α (Fig. 1) (Gilchrest et al., 1983; Cooper et al., 1993; Clydesdale et al., 2001). Moreover, when exposed to inflammatory mediators, skin-infiltrating macrophages differentiate into proinflammatory, M1-polarized macrophages (Sethi and Sodhi, 2004; Mills, 2012). M1-macrophages produce iNOS as part of an antimicrobial response during periods of skin inflammation (Mills, 2012). However, excessive production of iNOS increases tissue damage by prolonging inflammation and preventing tissue repair (Mills, 2012). In contrast to proinflammatory M1-macrophages, M2-polarized macrophages are anti-inflammatory and function to promote tissue repair and wound healing (Mills, 2012).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of vitamin D3 role in mediating anti-inflammation and tissue repair following ultraviolet injury of the skin.

Other groups have demonstrated in vitro that monocytes treated with vitamin D3 and retinoic acid differentiate into M2-macrophages (Di Rosa et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2014). Keratinocytes and macrophages both possess 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase (CYP27B1), an enzyme that allows these cells to convert vitamin D3 into its active form (Adams and Gacad, 1985). This conversion occurs extrarenally, which unlike the proximal tubule of the kidney, is not under feedback inhibition (Adams and Gacad, 1985; Zhang et al., 2012). A mechanism for locally producing active vitamin D3 suggests that vitamin D3 may signal in an autocrine or paracrine manner to modulate immune responses within the skin microenvironment. Moreover, endogenous retinoids, commonly found in the skin, are increased in the skin of mice following UVR exposure, and have also been shown to be required for skin repair following acute UVR exposure (Everts, 2012; Gressel et al., 2015).

We propose that administering a large bolus of vitamin D3 after sunburn increases the local concentration of inactive vitamin D3 within sunburned skin, which is then rapidly converted to active vitamin D3 by keratinocytes and skin-infiltrating macrophages (Fig. 1). Active vitamin D3, combined with endogenous retinoids generated from exposure to acute UVR, results in the preferential differentiation of anti-inflammatory M2-macrophages. The presence of M2-polarized macrophages within sunburned skin helps resolve inflammation, promote tissue repair, and restore homeostasis. In our study, M2-macrophages expressing arginase-1 and markers of autophagy were increased in sunburned skin following vitamin D3 intervention (Scott et al., 2017).

Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of autophagy increases apoptosis following acute UVR exposure, suppresses the recruitment of M2-macrophages into sunburned skin, and prevents the vitamin D3-dependent downregulation of proinflammatory mediators (article under review). Taken together, these data support a critical role for M2-macrophages with enhanced autophagy in mediating the anti-inflammatory and protective effects of vitamin D3 after sunburn. Interestingly, a similar protective role for M2-macrophages after treatment with vitamin D3 has been proposed in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy (Zhang et al., 2014). However, to validate this hypothesis, it will be important to determine if a rise in the serum vitamin D3 concentration following high-dose vitamin D3 intervention is associated with a concomitant rise in the local vitamin D3 concentration within the skin.

Multiple adaptations exist within mammalian skin to protect against the harmful effects of UVR that impair the barrier function of skin. These include a stratified squamous epithelium comprising keratinocytes linked together by desmosomes, multiple layers of anucleated corneocytes bound together tightly in the stratum corneum, melanin pigmentation, and immune surveillance in the form of antigen-presenting cells within the epidermis and dermis that recognize and respond to danger- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (Clydesdale et al., 2001). Interestingly, there is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for both generating inactive vitamin D3 within the skin, as well as a mechanism for rapidly activating vitamin D3 by skin-resident cells independent of systemic circulation and renal metabolism (Bikle, 2011). It is plausible that these mechanisms arose and persisted throughout our evolutionary history because of a critical role for vitamin D3 in maintaining skin homeostasis. By virtue of its exposed location, skin is constantly exposed to inflammatory environmental insults, and vitamin D3 may therefore function as a complementary defense mechanism to suppress low levels of skin inflammation and restore skin barrier function.

In summary, the results of our in vivo human study, combined with animal and in vitro models, suggest that vitamin D3 exerts immunomodulatory effects at the cellular and tissue level by selectively inducing the differentiation of anti-inflammatory, M2-macrophages. M2-macrophages, through the expression of arginase-1, downregulation of TNF-α and iNOS, and induction of autophagy, boost the resolution of inflammation, promote tissue repair, and enhance wound healing. Thus, vitamin D3 may serve a unique role in the skin, acting as an “endocrine barrier” to provide additional protection against environmental injury and effectively maintain skin barrier function.

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by two grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers U01-AR064144 and P30-AR039750.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Adams J.S., and Gacad M.A. (1985). Characterization of 1 alpha-hydroxylation of vitamin D3 sterols by cultured alveolar macrophages from patients with sarcoidosis. J Exp Med 161, 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Dermatology. (2009). American Academy of Dermatology Position Statement on Vitamin D. https://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Vitamin D.pdf (accessed September3, 2017)

- Bikle D.D. (2011). Vitamin D metabolism and function in the skin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 347, 80–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clydesdale G.J., Dandie G.W., and Muller H.K. (2001). Ultraviolet light induced injury: immunological and inflammatory effects. Immunol Cell Biol 79, 547–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper K.D., Duraiswamy N., Hammerberg C., Allen E., Kimbrough-Green C., Dillon W., et al. (1993). Neutrophils, differentiated macrophages, and monocyte/macrophage antigen presenting cells infiltrate murine epidermis after UV injury. J Invest Dermatol 101, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham T.J., Tabacchi M., Eliane J.P., Tuchayi S.M., Manivasagam S., Mirzaalian H., et al. (2017). Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest 127, 106–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Hughes B., Mithal A., Bonjour J.P., Boonen S., Burckhardt P., Fuleihan G.E., et al. (2010). IOF position statement: vitamin D recommendations for older adults. Osteoporosis Int 21, 1151–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rosa M., Malaguarnera G., De Gregorio C., Palumbo M., Nunnari G., and Malaguarnera L. (2012). Immuno-modulatory effects of vitamin D3 in human monocyte and macrophages. Cell Immunol 280, 36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didriksen A., Grimnes G., Hutchinson M.S., Kjaergaard M., Svartberg J., Joakimsen R.M., et al. (2013). The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response to vitamin D supplementation is related to genetic factors, BMI, and baseline levels. Eur J Endocrinol 169, 559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euvrard S., Kanitakis J., and Claudy A. (2003). Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med 348, 1681–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts H.B. (2012). Endogenous retinoids in the hair follicle and sebaceous gland. Biochim Biophys Acta 1821, 222–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabri M., Stenger S., Shin D.M., Yuk J.M., Liu P.T., Realegeno S., et al. (2011). Vitamin D is required for IFN-gamma-mediated antimicrobial activity of human macrophages. Sci Transl Med 3, 104ra2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrest B.A., Soter N.A., Hawk J.L., Barr R.M., Black A.K., Hensby C.N., et al. (1983). Histologic changes associated with ultraviolet A: induced erythema in normal human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 9, 213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressel K.L., Duncan F.J., La Oberyszyn T.M., Perle K.M., and Everts HB. (2015). Endogenous retinoic acid required to maintain the epidermis following ultraviolet light exposure in SKH-1 hairless mice. Photochem Photobiol 91, 901–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M.F., Binkley N.C., Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Gordon C.M., Hanley D.A., Heaney R.P., et al. (2011). Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 1911–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilahi M., Armas L.A., and Heaney R.P. (2008). Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr 87, 688–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.W., Arellano-Mendoza M.I., and Stengel F. (2017). Current challenges in photoprotection. J Am Acad Dermatol 76, S91–s99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos E., Keiser E., Kanzler M., Sainani K.L., Lee W., Vittinghoff E., et al. (2012). Sun protective behaviors and vitamin D levels in the US population: NHANES 2003–2006. Cancer Causes Control 23, 133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.T., Stenger S., Li H., Wenzel L., Tan B.H., Krutzik S.R., et al. (2006). Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science (New York, NY) 311, 1770–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills C.D. (2012). M1 and M2 Macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol 32, 463–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora J.R., Iwata M., and von Andrian U.H. (2008). Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol 8, 685–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi T., Barnetson R.S., Zhuang L., McKane S., Lee J.H., Slade H.B., et al. (2006). Imiquimod-induced regression of actinic keratosis is associated with infiltration by T lymphocytes and dendritic cells: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 154, 72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen B., Wulf H.C., Triguero-Mas M., Philipsen P.A., Thieden E., Olsen P., et al. (2014). Sun and ski holidays improve vitamin D status, but are associated with high levels of DNA damage. J Invest Dermatol 134, 2806–2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A.C., Manson J.E., Abrams S.A., Aloia J.F., Brannon P.M., Clinton S.K., et al. (2011). The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K.M., Stuart A.L., Williamson E.J., Simpson J.A., Kotowicz M.A., Young D., et al. (2010). Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 303, 1815–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.F., Das L.M., Ahsanuddin S., Qiu Y., Binko A.M., Traylor Z.P., et al. (2017). Oral vitamin D rapidly attenuates inflammation from sunburn: an interventional study. J Invest Dermatol 137, 2078–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi G., and Sodhi A. (2004). In vitro activation of murine peritoneal macrophages by ultraviolet B radiation: upregulation of CD18, production of NO, proinflammatory cytokines and a signal transduction pathway. Mol Immunol 40, 1315–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl E., de Jongh R.T., Heymans M.W., van Schoor N.M., and Lips P. (2015). Thresholds for serum 25(OH)D concentrations with respect to different outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100, 2480–2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Hatta Y., Iriyama N., Hasegawa Y., Uchida H., Nakagawa M., et al. (2014). Induced differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells into M2 macrophages by combined treatment with retinoic acid and 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. PLoS One 9, e113722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groningen L., Opdenoordt S., van Sorge A., Telting D., Giesen A., and de Boer H. (2010). Cholecalciferol loading dose guideline for vitamin D-deficient adults. Eur J Endocrinol 162, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobke T.K., Sorg B.L., and Steinhilber D. (2014). Vitamin D in inflammatory diseases. Front Physiol 5, 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A.R., Claveau J., and Rossi A.B. Ultraviolet radiation and the skin: photobiology and sunscreen photoprotection (2017). J Am Acad Dermatol 76, S100–S109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.L., Guo Y.F., Song Z.X., and Zhou M. (2014). Vitamin D prevents podocyte injury via regulation of macrophage M1/M2 phenotype in diabetic nephropathy rats. Endocrinology 155, 4939–4950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Leung D.Y., Richers B.N., Liu Y., Remigio L.K., Riches D.W., et al. (2012). Vitamin D inhibits monocyte/macrophage proinflammatory cytokine production by targeting MAPK phosphatase-1. J Immunol 188, 2127–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]