Abstract

Background:

High blood pressure is the greatest risk factor of death, and patients should manage to control it. Peer support program is used to control chronic diseases. This study aims to determine the effect of peer support program on adherence to the regimen in patients suffering from hypertension.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a clinical trial conducted among 64 patients with hypertension referring to the Hypertension Research Center (Isfahan. Iran). The information was collected in three stages – before the start of intervention, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention using a questionnaire of adherence to the treatment regimen for high blood pressure. The questionnaires were filled using a questioning method by patients who were not aware of the study. The experimental group attended 6 sessions of the peer support program (1 hour), and the control group attended two sessions held by the researcher. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 18 software, and statistical tests were analyzed using independent t-test and analysis of variance with repeated measures.

Results:

Before the intervention, there was no significant difference in adherence to the treatment regimen score between the two groups regarding the three aspects of medication regimen, diet, and activity program. Increase in scores of control group immediately after and 1 month after peer support program was higher (p < 0.001) compared to before the intervention.

Conclusions:

This study showed that peer support programs had a positive impact on adherence to the treatment regimen in patients suffering from hypertension.

Keywords: Hypertension, Iran, peer group, support program

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of death in the world.[1] One of the most common causes of cardiovascular disease is hypertension.[2] Hypertension is one of the main problems in the world.[3] It has been announced as the most common cause of strokes and heart attack, as well as the second leading cause of death in Iran in 2013.[4] This disease is important due to its high prevalence, but the important concern is lack of disease control.[2] Hypertension is one of the diseases which its major control being the responsibility of patients.[5] On the other hand, one of the important factors in controlling hypertensive disease is adherence to the treatment regimen, which has not been satisfactory in patients with high blood pressure.[6] Lack of adherence to the treatment regimen has been reported as the main cause of treatment and control failures in many studies.[7] Using appropriate interventions is important to enhance the knowledge of patients in controlling this disease.[8] One of the low-cost interventions in this field is providing information to people suffering from this disease. Peer support group as the informants of the disease can help in providing information to patients.[9] Peer group has an empirical knowledge about the disease and can make it available to patients.[10] Although various studies confirm the effectiveness of this method in patients with chronic disorders in different aspects, some studies have reported an ineffectiveness of the peer support programs.[11] Nevertheless we did not find any studies regarding its impact on adherence to the treatment regimen of patients with high blood pressure. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of peer support training program on patients suffering from hypertension.

Materials and Methods

This is a clinical trial study conducted at the Isfahan Hypertension Research Center in 2015. The inclusion criteria for the patients being included in the study were willingness to participate in the study, being literate and fluent in Persian, having a history of hypertension, being treated with at least one antihypertensive medication, and being more than 18 years old. In this study, (registration number: IRCT2015112125161 N), the sample size was achieved at a 95% confidence level and power factor of 80% for each of the groups of 32 individuals; 10% was added to the sample size to account for sample loss. Convenient random sampling method was used and participants were assigned in into two groups of intervention and control. First, the questionnaire of adherence to the treatment regimen of high blood pressure was filled using a questioning method by patients who were unfamiliar with the study. Three individuals who had higher scores and were better educated and were also interested in their leadership of the group[12] and whose blood pressure was within normal limits over the past month were selected to take the lead of the group. The samples in the experimental group were divided in groups of 8–11. Before holding the sessions for the samples, three successful peers who were chosen as the leaders of the group attended two 1.5-hour sessions.[9] Six 60-minute sessions once a week were held for the members of the experimental group.[13] In addition, the phone numbers of peers were given to the members of the group. The researcher attended all the sessions as the observer. The control group participated in two 1-hour sessions held by the researcher. The sessions were about the general idea of hypertension disease, healthy nutrition, and the importance of exercise on health.[9] The questionnaire of adherence to the treatment regimen was filled immediately after the intervention and again 1 month later.[14] Instruments used were a two-part questionnaire that contained two parts – the first part of which included demographic characteristics of patients and their disease information. The second part of the questionnaire of adherence to the treatment regimen was in three axes. The first axis which reviewed the patient's diet contained 30 questions regarding their food basket. The second axis included 10 questions about the adherence to the medication regimen, and the third axis had 14 questions to assess the level of adherence to the program. For scoring, each item was rated from 0–100 (25, 50, 75, and 100). If the items selected by the samples were closer to health behaviors, the score will be higher; if the items were contrary to health behaviors, score will be lower.[7] Validity and reliability of the questionnaire were evaluated by Sanaee et al., and a test–retest reliability of r = 0.83 was achieved for the instrument; moreover, content validity was used to determine the scientific validity of this instrument.[7] The statistical analysis of data was performed using independent t-test, Chi-square, Mann-Whitney U test, and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The statistical analysis of data was performed using spss inc.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, with the ethical code of 394 268; the individuals were requested to fill in the written informed consent before beginning the study.

Results

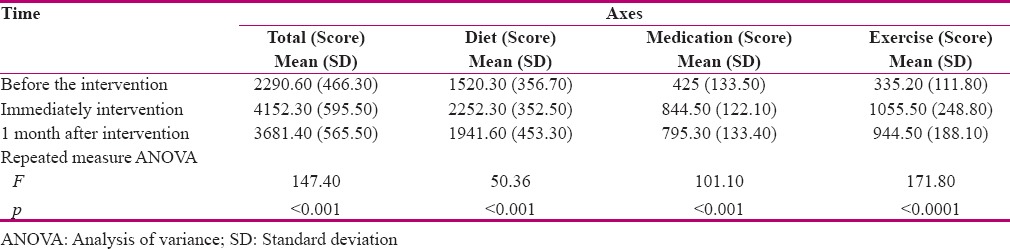

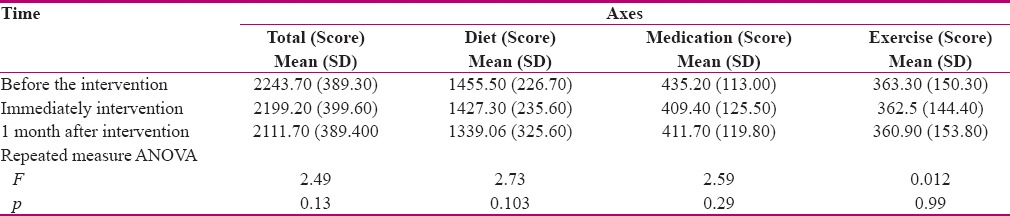

There were no significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding demographic variables (p > 0.05). In the experimental group, the overall score of adherence to the treatment regimen in three aspects of medication regimen, diet, and activity program was different before, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention (p < 0.001) [Table 1]; whereas, there was no significant difference in the control group regarding the overall mean score of adherence to the treatment regimen and in three aspects of medication regimen, diet, and activity program before, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention (p < 0.05) [Table 2]. The overall score of adherence to the treatment regimen and in three aspects before, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention was higher in the experimental group compared to the control group (p < 0.001). In addition, the increase in scores immediately after the intervention was higher than those 1 month later. The mean changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure immediately after and 1 month after the intervention improved in the control group (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean score of adherence to treatment in 3 axes in the experimental groups at different times

Table 2.

Comparison of the mean score of adherence to treatment in 3 axes in the control groups at different times

Discussion

The results of this study showed that the peer support program improved the overall score of adherence to the treatment regimen in the experimental group. Moreover, peer support program created significant differences in the mean change scores of the three aspects of medication regimen, diet, and activity program in the experimental group before, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention; however, there were no significant differences in the control group. Increase in scores of all aspects immediately and 1 month later was higher than that before the intervention.

In confirmation of the results of the present study, a study by Dehghani et al. in 2012 titled “The Effect of Peer Group Education on Anxiety of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis” in Isfahan showed that the mean change of depression score in the samples has been different before, immediately after, and 4 months after the intervention in the experimental group (p < 0.05); the depression score in the group that had used peer support program decreased compared to control group; whereas, the mean change of depression score in the samples before, immediately after, and 4 months after the intervention in the control group had no significant difference) (p > 0.05).[6]

Sharif et al. conducted a study to evaluate the effect of peer support group on the quality of life in patients suffering from breast cancer after performing mastoidectomy surgery. Their study did not show differences in the quality of life dimensions before intervention in patients suffering from breast cancer after surgery (p < 0.05); however, there was a difference immediately after the intervention in the life quality of patients in the experimental group (p < 0.001).[15] In line with the results of the present study, Baumann et al. conducted a study to evaluate the effect of peer group program on adult patients with type II diabetes in Angola. Their study showed that peer support group program had an effect on patients’ systolic blood pressure, patients following a diet, and HbA1c or glycated hemoglobin of samples (p < 0.05). Therefore, glycosylated hemoglobin decreased by 11.13% in the experimental group before the intervention and after the intervention of peer support group decreased by 2.83% and reached 8.30%, which represented a significant impact of peer support program.[8] Unlike the results of the present study, Mehr et al. study in California that aimed to determine the effects of phone calls program of peer group on the quality of life and the level of depression of patients with multiple sclerosis. In their study, there were significant differences in the quality of life of patients, for example, in the emotional, mental, physical aspects, and confidence level of the samples. Although this study was consistent with the study of Mehr et al. in terms of sample size, number, and duration of the sessions, holding meetings was not the same.[9] Therefore, in the present study, the sessions were administered in person and in the form of questions and answers and discussion groups as well as demonstrations; later also, if necessary, the samples could call the peers between the sessions. Mehr et al., however, conducted the sessions by phone and the groups had a 1-hour phone call within a week.

From the researcher's perspective, it seems that the sociocultural differences of research population in the two studies and type of the disease can also lead to different results in the two studies. Tang et al. (2014) conducted a study to compare the effect of peer support program and community health workers calls on glycosylated hemoglobin level in patients with diabetes for a year. Results of the study showed the positive impact of both studies [community health workers calls (p = 0.004) and peer group program (p < 0.001)] in control and experimental groups immediately after the intervention. Moreover, mean changes in the systolic and diastolic blood pressure in these patients 12 months after the study (p = 0.001) and 6 months (p = 0.002) were significantly different.[16] Johansson et al. (2014) conducted a study in Austria to investigate the effect of peer support group on metabolic values in patients with diabetes. Unlike the results of the present study, their study showed that, after the 24-month follow-up period, there were no significant differences in glycosylated hemoglobin values, level of serum lipids, high density lipoprotein (HDL), cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), and blood creatine (p > 0.05). In view of the researcher, the reason for the difference between the present study and the study conducted by Johansson et al. has been attributed to number of samples, longer follow-up time, and cultural differences of the populations studied. The present study was conducted among 64 samples in two groups for six 1-hour sessions and the questionnaires were completed immediately after and 1 month after intervention; the participants were suffering from hypertension and lived in Isfahan. While Johansson et al. study was conducted among 337 Austrian patients with diabetes with 12 months of intervention of monthly sessions of group discussion and weekly sports sessions and the results were evaluated 24 months later. It seems that time is an influencing factor on the results of the support program; perhaps in the present study if the questionnaires were filled later after the intervention, different results would have been noted.[17] Limitations of this study were to obtain information from other sources, and that information was gathered after a short-term period of 1 month after the intervention.

Conclusion

This study showed that peer support programs had a positive impact on adherence to the treatment regimen in patients with hypertension. Moreover, it showed that peer support programs had a positive impact on systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was derived from the Masters’ thesis with the research code of 394268 in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. The authors wish to thank the Research Deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan Center of hypertension, and the study participants.

References

- 1.Alidosti M, Hemati Z. Educational Intervention on Peers Knowledge and Behaviors of Students with Diabetes Type I. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J. 2013;3:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronish IM, Goldfinger JZ, Negron R, Fei K, Tuhrim S, Arniella G, et al. Effect of Peer Education on Stroke Prevention. Stroke. 2014;45:3330–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachmechi I, Wang A, Kim P, Reich D, Payne H, Salvador VB. Impact of diabetes education and peer support group on the metabolic parameters of patients with diabetes mellitus (type 1 and type 2) Br J Med Pract. 2013;6:635–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadeghi R, Mohseni M, Khanjani N. The effect of an educational intervention according to hygienic belief model in improving care and controlling among patients with hypertension. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2014;13:383–94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azizi K, Sharifi Rad Gh, Mahaki B, Iranpour S, Abdoli R, et al. Psychometric assessment of nutritional knowledge, illness perceptions and dietary adherence in hypertensive patients. J Health Syst Res. 2013;2:1774–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehghani A, Mohammadkhan Kermanshahi S, Memarian R, Baharlou R. The effect of peer group education on anxiety of patients with multiple sclerosis. Iran J Med Educ. 2012;12:249–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosack KE, Patterson L, Brouwer AM, Wendorf AR, Ertl K, Eastwood D, et al. Evaluation of a peer-led hypertension intervention for veterans: Impact on peer leaders. Health Educ Res. 2013;28:426–36. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann LC, Frederick N, Betty N, Jospehine E, Agatha N. A demonstration of peer support for ugandan adults with type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22:374–83. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohr DC, Burke H, Beckner V, Merluzzi N. A preliminary report on a skills-based telephone-administered peer support programme for patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:222–6. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1150oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heisler M, Halasyamani L, Cowen ME, Davis MD, Resnicow K, Strawderman RL, et al. Randomized Controlled Effectiveness Trial of Reciprocal Peer Support in Heart FailureClinical Perspective. Circulation Heart Fail. 2013;6:246–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghods R, Gharuni M, Amin Gh, Nazem E, Mokaberinejad R, Nikbakht Nasrabad A. A rapid overview on the causes of hypertension and relationship between Imtila and hypertension in Iranian Traditional Medicine. Journalssbmu. 2011;2:11–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masror Roudsari D, Dabiri Golchin M, Haghani H. Relationship between Adherence to Therapeutic Regimen and Health Related Quality of Life in Hypertensive Patients. Iran J Nurs. 2013;26:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan Q, Stamler J, Elliott P. Dietary factors and higher blood pressure in african-americans. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharif F, Abshorshori N, Hazrati M, Tahmasebi S, Zare N. The Effect of Peer Education on Quality of Life in Patient with Breast Cancer After Sergery. Payesh J. 2012;11:703–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daugherty SL, Powers JD, Magid DJ, Masoudi FA, Margolis KL, O’Connor PJ, et al. The Association Between Medication Adherence and Treatment Intensification With Blood Pressure Control in Resistant Hypertension Novelty and Significance. Hypertension. 2012;60:303–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.192096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang TS, Funnell M, Sinco B, Piatt G, Palmisano G, Spencer MS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of peer leaders and community health workers in diabetes self-management support: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1525–34. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson T, Keller S, Winkler H, Ostermann T, Weitgasser R, Sönnichsen AC. Effectiveness of a peer support programme versus usual care in disease management of diabetes mellitus type 2 regarding improvement of metabolic control: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Diabetes Res 2015. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/3248547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]