Abstract

Background:

Anti-IgE treatment represents a major breakthrough in the therapeutic management of severe allergic asthma. To date, omalizumab is the only biological drug currently licensed as add-on therapy in children aged > 6 years with moderate-to-severe and severe allergic asthma uncontrolled after treatment with high dose of inhaled corticosteroids plus long-acting inhaled beta2-agonist. The clinical efficacy and safety of omalizumab treatment in the pediatric population has been extensively documented in specific trials and consistently expanded from real-life studies. Our aim is to describe the impact of omalizumab on asthma management, by reporting the results of the first Italian multicenter observational study conducted in children and adolescents with severe allergic asthma.

Methods:

The study was a 1-year real-life multicenter survey conducted in 13 pediatric allergy and pulmonology tertiary centers in Italy. All patients with confirmed severe allergic asthma from whom Omalizumab add-on treatment was initiated between 2007 and 2015 were included in the study.

Results:

Forty-seven patients with severe allergic asthma were included in the study. A significant reduction in the number of asthma exacerbations was observed during treatment with omalizumab, when compared with the previous year (1.03 vs 7.2 after 6 months (p<0.001) and 0.8 after 12 months (p<0.001), respectively). Hospital admissions were reduced by 96%. At 12 months, forced expiratory volume in 1 s improved and a corticosteroid sparing effect was observed.

No serious adverse events were reported during the follow-up period of 12 months.

Conclusion:

The results of the first Italian multicenter observational study confirmed that omalizumab is an effective and safe add-on therapy in uncontrolled severe allergic asthma in children.

Keywords: Allergic asthma, anti-IgE, asthma therapy, monoclonal antibodies, omalizumab, severe asthma

1. INTRODUCTION

The discovery of immunoglobulin E (IgE) as a novel therapeutic target for allergic diseases has led to the develop-ment of anti-IgE treatment, which actually represents a major breakthrough in the therapeutic management of severe allergic asthma.

Omalizumab, the first biologic for treating allergic disease, is an advanced humanized IgG1 monoclonal anti-IgE antibody specifically designed to target circulating free IgE and prevent its interaction with the high- and low-affinity IgE receptors, thus interfering with cell activation and me-diator release and comprehensively reducing allergic inflam-mation [1, 2]. To date, omalizumab is the only biological drug currently licensed as add-on therapy in children aged > 6 years with moderate-to-severe and severe allergic asthma uncontrolled after treatment with high dose of inhaled cor-ticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting inhaled beta2-agonist (LABA) [3, 4]. The clinical efficacy and safety of omalizu-mab treatment in the pediatric population has been extensiv- ely documented in specific trials and consistently expanded from real-life studies [5-9]. These studies have shown that add on-therapy with omalizumab was significantly effective in reducing asthma exacerbations and hospitalizations rates with a steroid-sparing effect and improving health-related quality of life (QoL), asthma symptoms and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) [10-12].

In Italy, omalizumab is indicated as add-on therapy to improve asthma control in adolescents (aged >12 years) and children (aged 6 to <12 years) with severe persistent allergic asthma who have a positive skin test or in vitro reactivity (blood test) to a perennial aeroallergen and who have frequent daytime symptoms or night-time awakenings and who have had multiple documented severe asthma exacerbations despite daily high-dose ICS plus LABA.

Patients aged >12 years must also have reduced lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) less than 80% of normal) [13].

The aim of this study is to describe the impact of omalizumab on asthma management, by reporting the results of the first Italian multicenter observational study conducted in children and adolescents with severe allergic asthma.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was a 1-year real-life multicenter survey conducted in 13 pediatric allergy and pulmonology tertiary centers in Italy.

All patients with confirmed severe allergic asthma from whom omalizumab add-on treatment was initiated between 2007 and 2015 were included in the study.

Baseline characteristics were collected from patients’ clinical records: demographic data, asthma-related clinical history (age at diagnosis of asthma, ICS doses and medi-cations used, emergency department (ED) visits, hospita-lizations and/or intensive care unit (ICU) admissions for asthma ever) and asthma severity over the previous year assessed using rate of exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids, omalizumab dosing and period of treatment, lung function data, allergic sensitization assessed by skin prick test, specific and total IgE levels.

Omalizumab was administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 or 4 weeks. Dose and frequency of administration are guided by a nomogram that is derived from total serum IgE level at baseline (eligible between 30-1500 IU/ml) and patients’ weight.

The investigators conducted patients’ data collection on a standardised document at baseline, at 6 months and 12 months after beginning of treatment with omalizumab.

Exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids for at least 3 days were considered clinically significant. Healthcare utilization was estimated by the number of ED visits or hospitalizations for asthma exacerbations. ICS maintenance therapy was registered at each visit and ICS doses were standardised to fluticasone equivalent dose per day (g). PTFs consisted of a flow-volume curve pre- and post-inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists (SABA) adminis-tration and were routinely included in patients’ asthma evaluation. FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) were expressed as % predictive (pred) values, FEV1/FVC ratio was expressed as a percentage.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of clinically significant asthma exacerbations over a period of 12 months of treatment with omalizumab.

Secondary efficacy endpoints were the reduction of healthcare utilization in comparison with that registered during the previous year, the steroid-sparing effect, and the lung function improvement over the 12 months of treatment with omalizumab.

Safety data were collected at each visit. Significant and serious adverse events (AEs) were defined according to European Medicines Agency criteria.

2.1. Statistics

Data are presented as n (%) for qualitative variables and as mean (standard deviation) for quantitative variables. Com-parisons between asthma exacerbations and lung function between baseline and 6 months and between baseline and 12 months were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data. Changes in ICS administered dose along the first year were assessed using a one-way Anova test with repeated measures. A p-value of 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were run using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, Version 20.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Data

Forty-seven patients with severe allergic asthma were included in the study. Overall, no patient was lost to follow-up. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Asthma was diagnosed at a mean age of 7,4 years (1-18 years). At baseline they were aged 6-21 years (mean age 11,7 years), with 27 patients (57%) aged < 12 years. Four subjects older than 18 years were included in the study, as they have received long-term follow-up in tertiary care pediatric setting for their severe asthma. Enrolled subjects underwent a comprehensive allergy evaluation including skin prick tests (n=3), specific IgE dosage (n=4) or both (n=40), each of them sensitized to one or more perennial allergen. Total serum IgE level was between 46-1360 UI/ml (medium 625,2 UI/ml).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

|

Patients’ number (n)

Patients aged < 12 years |

47

27 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| male (n) | 31 | |

| female (n) | 16 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| current | 15,4 [8;26] | |

| at diagnosis | 7,4 [1;18] | |

| at baseline | 11,7 [6;21] | |

| Total serum IgE at baseline (UI/ml) | 625,2 [46;1360] | |

| Perennial antigen sensitization: positivity tested by (n) | ||

| prick test | 3 | |

| sIgE | 4 | |

| both | 40 | |

| Patients who suffered of asthma related adverse events during the past year (n) | ||

| At least > 1 exacerbation (total events) |

47 (320) |

|

| ED visits (total events) |

20 (53) |

|

| Hospitalizations (total events) |

17 (30) |

|

| Asthma maintenance therapy at baseline (n) | ||

| ICS | 47 | |

| LABA | 47 | |

| OCS | 9 | |

| LTRA | 27 | |

| Theophylline | 3 | |

| Lung function (FEV1) | ||

| Litres | 2,03 [0,81;5,9] |

|

| % of predicted | 79,02 [48,5; 114] |

n, number of patients; BMI, Body Mass Index; sIgE, serum IgE; ED, Emergency Department; ICS, Inhaled Corticosteroids; LABA, long‐acting β2‐agonist; OCS, Oral Corticosteroids; LTRA, Leukotriene Receptor Antagonist; FEV1, Forced Expiratory Volume in the 1st second.

At baseline, 42% of patients had been evaluated at the ED for asthma exacerbations during the previous year, with 15 children requiring more than one admission, leading to 30 hospital stays, none of which were in the ICU. To maintain asthma control, 9 patients (19%) required continuous oral corticosteroid therapy.

Omalizumab was administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks in 25 patients (53%), and the remaining 47% received omalizumab every 4 weeks.

3.2. Primary Efficacy Endpoint

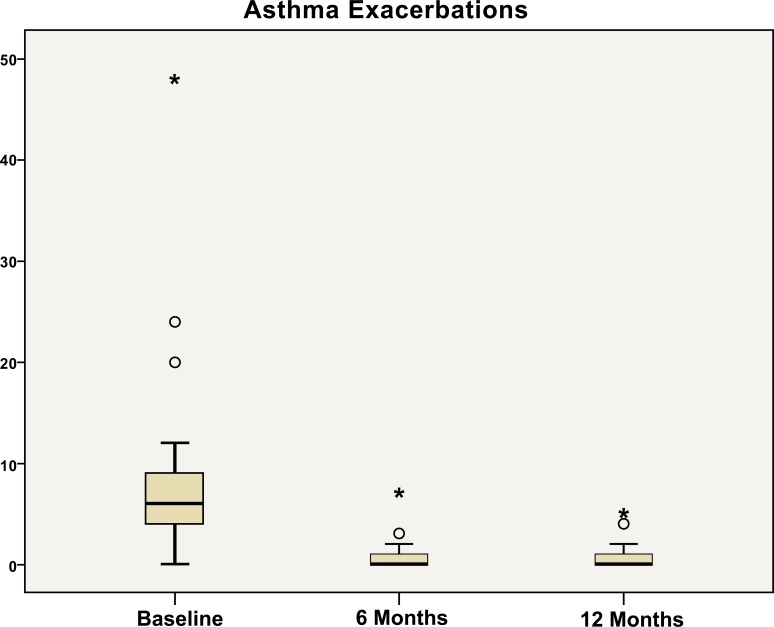

A significant reduction in the number of asthma exacer-bations was observed during treatment with omalizumab, when compared with the previous year (Fig. 1). In particular, the mean rate of clinically significant exacerbations decreased from 7.2 per patient during the previous year to 1.03 after 6 months (p<0.001) and to 0.8 per patient after 12 months of treatment (p<0.001). This represented a reduction of 91% over the year.

Fig. (1).

Number of asthma exacerbations at baseline, after 6 months, and after 12 months of treatment with omalizumab.

3.3. Secondary Efficacy Endpoints

The percentage of children requiring ED visits or hospi-talizations decreased, respectively, from 42% in the previous year to 4,2% under omalizumab therapy and from 36% to 2,1%, with none necessitating a stay in ICU during the year on treatment. Hospital admissions were reduced by 96%.

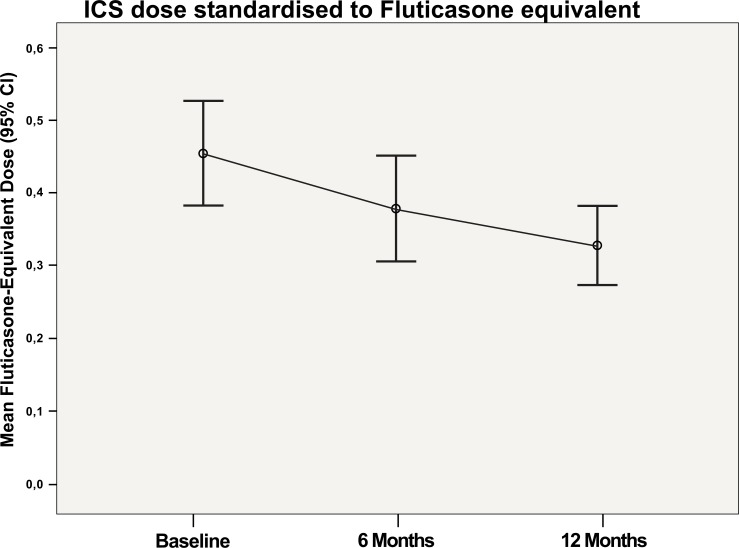

The mean ICS sparing effect per day was -153 μg after 12 months of treatment (Fig. 2). The mean administered dose of ICS standardised to fluticasone equivalent dose per day was 428 μg at baseline, 317 μg at 6 months and 275 μg at 12 months (p<0.001). Oral corticosteroids were withdrawn in all 9 children with this maintenance therapy at baseline.

Fig. (2).

Mean administered dose of ICS standardized to fluticasone equivalent dose per day at baseline, after 6 months, and after 12 months of treatment with omalizumab.

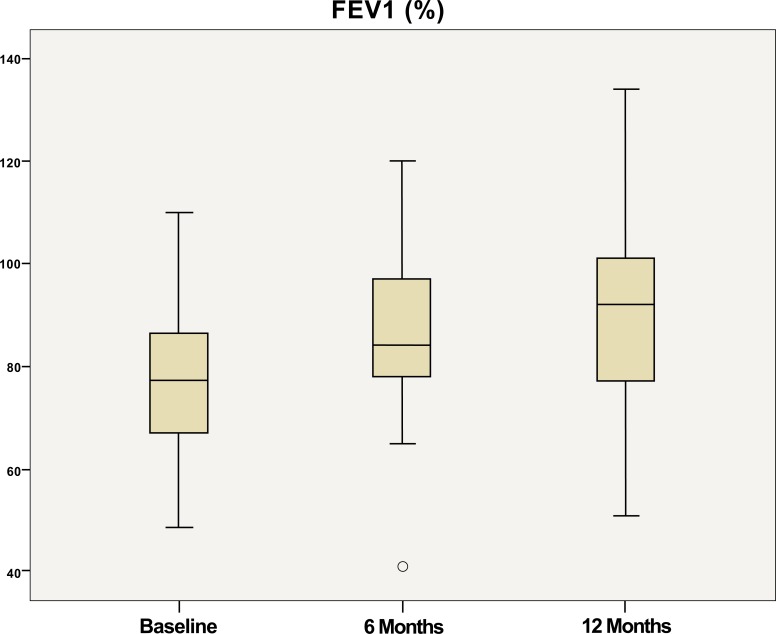

The lung function improved over the 12 months of treatment with omalizumab with FEV1 increasing from 79% pred at baseline to 90% pred and 91% pred at 6 and 12 months, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. (3).

FEV1distribution at baseline, after 6 months, and 12 months of treatment with omalizumab.

3.4. Safety

No serious AEs were reported during the follow-up period of 12 months; three significant mild adverse reactions were described: one patient had asthenia after the first administrations; one manifested hyperaemia and itching of chest and arms, reversible after antihistamine therapy, after the third administration; one had a mild local reaction in the injection site after the sixth administration. No AE led to discontinuation of therapy with omalizumab.

4. DISCUSSION

We describe the impact of omalizumab on childhood asthma management, by reporting the results of the first Italian multicenter observational study conducted in children and adolescents with severe allergic asthma. All 47 patients had received long-term follow-up in tertiary care pediatric centers in order to characterize their respiratory disease and to assess treatment efficacy and compliance. The advantage of observational studies is to provide real-life data, which might differ from that obtained in clinical trials.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the rate of clinically significant asthma exacerbations over a period of 12 months of treatment with omalizumab. We observed a 91% reduc-tion of exacerbations over the year. This result is in agree-ment with those observed in other observational studies and reinforced the previous 72% reduction reported in children and adolescents by Deschildre et al. [8]. Moreover, the effect on exacerbations was obtained during the first 6 months of treatment and is maintained over the year, in accordance with major literature data [5, 8]. By decreasing the number and severity of asthma exacerbations, omalizumab therapy reduced hospital admissions by 96% with none necessitating a stay in ICU during the year on treatment and, together with the reduction in exacerbations rate, significantly lightened the burden of healthcare utilization and improved patients’ QoL.

Another endpoint evaluated in this survey was the corti-costeroid-sparing effect. Oral corticosteroids were with-drawn in all 9 children with this maintenance therapy at baseline. ICS were reduced in all patients. However, ICS mean dose at baseline was not as high as observed in other studies. A possible explanation is the high number of patients < 12 years for whom a dosage of fluticasone propionate > 400 μg is already considered a high dose. The reduction of ICS therapy at 12 months is statistically significant and in line with previous published data [5-8]. These findings are of major importance considering the potential side effects of prolonged steroid therapy on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and on growth in pedi-atric patients with severe asthma and respiratory comor-bidities [14].

The lung function, evaluated with FEV1, improved over the first 6 months of treatment with omalizumab and this improvement is maintained at 12 months. However, it is important to highlight that FEV1 at baseline was > 80% in the majority of patients and this is due to the early age of patients whose lung function was not already reduced.

The safety profile of omalizumab therapy in children has been assessed in specific safety reviews [15]. Our patients reported no serious AEs during the follow-up period of 12 months and no AE led to discontinuation of therapy with omalizumab.

The major limitation of this study is the limited number of patients. We aim to enroll new patients and to continue the follow-up of enrolled patients beyond 1 year of administration of omalizumab therapy.

5. Standard Protocol on Approvals, Registrations, Patient Consents & Animal Protection

The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the code of ethics of the world medical association (declaration of helsinki). The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data. The authors have obtained the written informed consents from patients' parents and patients of age > 18 years for the use of clinical data for research purposes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our data are supportive of the existing evidence that omalizumab therapy reduces asthma exacer-bations and healthcare utilization, has a steroid-sparing effect and improves lung function. With the results of the first Italian multicenter observational study, we confirmed that omalizumab is an effective and safe add-on therapy in uncontrolled severe allergic asthma in children.

OMALIZUMAB IN CHILDHOOD ASTHMA ITALIAN STUDY GROUP

Members of the Omalizumab in Childhood Asthma Italian Study Group included as authors are: Elisa Anastasio (A.O. “Pugliese Ciaccio”, University of Catanzaro, Catan-zaro, Italy), Carlo Caffarelli (Pediatric Clinic, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Parma, Parma, Italy), Fabio Cardinale (Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Hospital “Giovanni XXIII”, University of Bari, Bari, Italy), Anastasia Cirisano (Pediatric Unit, San Giovanni di Dio Hospital, Crotone, Crotone, Italy), Giuseppe Crisafulli (Pediatric Allergy Unit, University of Messina, Messina, Italy), Renato Cutrera (Respiratory Unit, Depart-ment of Pediatric Medicine, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital, Rome, Italy), Giuseppe Di Cara (Institute of Paediatrics, Department of Biomedical and Surgical Specia-lties, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy), Antonio Di Marco (Respiratory Unit, Department of Pediatric Medicine, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital, Rome, Italy), Marzia Duse (Department of Pediatrics, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy), Cecilia Fabiano (Department of Pediatrics, University of L'Aquila, San Salvatore Hospital, L'Aquila, Italy), Alessandro Fiocchi (Division of Allergy, University Department of Pediatrics, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital, Rome, Italy), Maddalena Leone (Department of Pediatrics, AO Ospedale Civile di Legnano, Legnano-Milano, Italy), Giovanni Pajno (Pediatric Allergy Unit, University of Messina, Messina, Italy), Elisa Panfili (Institute of Paediatrics, Department of Biomedical and Surgical Specialties, University of Perugia, Perugia Italy), Guido Pellegrini (Department of Pediatrics, Sondrio Hospital, Sondrio, Italy), Alberto Verrotti (Department of Pediatrics, University of L'Aquila, San Salvatore Hospital, L'Aquila, Italy.), Alessandro Volpini (Pediatric Unit, Senigallia Hospital, Senigallia, Italy).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors would like to thank Dr. Cristina Torre (Department of Pediatrics, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy) for her help and fruitful assistance in all phases of this project design.

AL, RC and GLM made substantial contribution to conception and design of the study, and to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the final version of the manuscript; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CD, LR and MS made substantial contribution to acquisition of data; drafted the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. LS made substantial contribution to the statistical analysis of data collected; drafted the article and approved the final version of the manuscript. GT and MDA made substantial contribution to analysis and interpretation of data; drafted the article and approved the final version of the manuscript All members of the Omalizumab in Childhood Asthma Study Group made substantial contribution to the collection of data.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AEs

Adverse events

- ED

Emergency department

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroid

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- LABA

Long-acting inhaled 2-agonist

- Pred

Predicted

- PTFs

Pulmonary function tests

- QoL

Quality of life

- SABA

Short-acting 2-agonists

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Licari A., Marseglia G., Castagnoli R., Marseglia A., Ciprandi G. The discovery and development of omalizumab for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015;10(9):1033–1042. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1048220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciprandi G., Marseglia G.L., Castagnoli R., et al. From IgE to clinical trials of allergic rhinitis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2015;11(12):1321–1333. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.1086645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung K.F., Wenzel S.E., Brozek J.L., et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43(2):343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Asthma Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2016 www.ginasthma.com

- 5.Milgrom H., Berger W., Nayak A., et al. Treatment of childhood asthma with anti-immunoglobulin E antibody (omalizumab). Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanier B., Bridges T., Kulus M., Taylor A.F., Berhane I., Vidaurre C.F. Omalizumab for the treatment of exacerbations in children with inadequately controlled allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124(6):1210–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse W.W., Morgan W.J., Gergen P.J., et al. Randomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364(11):1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deschildre A., Marguet C., Salleron J., et al. Add-on omalizumab in children with severe allergic asthma: a 1-year real life survey. Eur. Respir. J. 2013;42(5):1224–1233. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deschildre A., Marguet C., Langlois C., et al. Real-life long-term omalizumab therapy in children with severe allergic asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;46(3):856–859. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Normansell R., Walker S., Milan S.J., Walters E.H., Nair P. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;(1):CD003559. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003559.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigo G.J., Neffen H. Systematic review on the use of omalizumab for the treatment of asthmatic children and adolescents. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(6):551–556. doi: 10.1111/pai.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Licari A., Marseglia A., Caimmi S., et al. Omalizumab in children. Paediatr. Drugs. 2014;16(6):491–502. doi: 10.1007/s40272-014-0107-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European public assessment report (EPAR) for Xolair. EMA http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/000606/WC500057293.pdf [cited: 3rd Dec 2016]

- 14.Marseglia G.L., Merli P., Caimmi D., et al. Nasal disease and asthma. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011;24(4) Suppl.:7–12. doi: 10.1177/03946320110240S402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milgrom H., Fowler-Taylor A., Vidaurre C.F., Jayawardene S. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab in children with allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2011;27(1):163–169. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.539502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]