Abstract

Objective

To compare antiphospholipid antibodies in deliveries with and without stillbirth using a multicenter, population-based case-control study of stillbirths and live births.

Methods

Maternal sera were assayed for IgG and IgM anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies. Assays were performed in 582 stillbirth deliveries and 1,547 live birth deliveries.

Results

Elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin and IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were associated with an approximate threefold increased odds of stillbirth; crude odds ratio (OR) 3.43 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.79, 6.60) (3.8% versus 1.1%) and OR 3.17 (95% CI 1.30, 7.72) (1.9% versus 0.6%), respectively when all deliveries with stillbirth were compared with all deliveries with live birth. When the subset of stillbirths not associated with fetal anomalies or obstetric complications were compared with term live births, elevated IgG anticardiolipin antibodies were associated with stillbirth (5.0% versus 1.0%) (OR 5.30, 95% CI 2.39–11.76); IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies (1.9% versus 0.6%) had an OR of 3.00 (95% CI 1.01–8.90) and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (6.0% versus 3.0%) had an OR of 2.03 (95% CI 1.09–3.76). Elevated levels of anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were associated with a threefold to fivefold increased odds of stillbirth.

Conclusions

Our data support consideration of testing for antiphospholipid antibodies in cases of otherwise unexplained stillbirth.

Introduction

Antiphospholipid antibodies are a heterogeneous group of autoantibodies that have been associated with thromboembolism and obstetric complications including stillbirth (1 – 3). Numerous antiphospholipid antibodies have been described but the best characterized, most widely recognized, and most strongly associated with clinical problems are the lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies (1, 4). Obstetric complications associated with antiphospholipid antibodies are thought to be due in part to placental insufficiency, either from abnormal placental development or placental damage from inflammation, thrombosis, and infarction (5). Patients with clinical problems, such as thrombosis (arterial, venous or small vessel) and obstetric complications (unexplained fetal death, three or more unexplained early pregnancy losses, or severe placental insufficiency), as well as specified levels of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, greater than 99% of anticardiolipin, greater than 99% of anti-β2-glycoprotein-I) are considered to have antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) (2).

Most studies of APS and pregnancy loss have focused on recurrent early pregnancy loss since the vast majority of pregnancy losses occur during the preembryonic and embryonic periods (6–8). Nonetheless, many experts consider antiphospholipid antibodies to be more strongly associated with fetal loss occurring during the fetal period (after 10 weeks of gestation) (9). Many, if not most studies of antiphospholipid antibodies do not provide details regarding the gestational age of pregnancy loss. Some studies have included some fetal losses, typically during the second trimester (4,9,10). However, the association between antiphospholipid antibodies and stillbirth has not been systematically assessed (11). Thus, our objective was to compare maternal levels of antiphospholipid antibodies in women with and without stillbirth in a large, population based, geographically and ethnically diverse cohort.

Materials and Methods

A population-based case-control study of stillbirth was conducted by the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Women were enrolled at the time of delivery between March 2006 and September 2008. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each clinical site and the data-coordinating center, and all participants gave written informed consent. Details of methods and study design have previously been published (12).

Stillbirth was defined as Apgar scores of 0 at 1minute and 5 minutes and no signs of life by direct observation at 20 or more weeks of gestation. However, fetal deaths at 18 weeks or 19 weeks without good dating were also included in the study so as to not miss any potential cases at or beyond 20 weeks of gestation (12). Gestational age was determined by the best clinical estimate using multiple sources including assisted reproductive technology with documentation of the day of ovulation of embryo transfer (if available), first day of the last menstrual period, and results of obstetric ultrasonography (13). Deliveries resulting from the termination of a live fetus were excluded.

The sample size considerations for the study have been described previously (14). Attempts were made to enroll all deliveries with stillbirth (cases) and a contemporaneous representative sample of deliveries with live birth (controls) to women residing in SCRN catchment areas during the enrollment period. The catchment areas included 59 tertiary care and community hospitals in portions of 5 states: Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Georgia, Texas and Utah. The areas were defined by state and county boundaries, and the 59 hospitals within the catchment areas deliver a combined total of over 80,000 infants per year. Some subgroups of live births were “oversampled” to ensure adequate numbers for stratified analyses (12).

All cases and controls had a standardized maternal interview during the delivery hospitalization and detailed chart abstraction of prenatal office visits, antepartum hospitalizations, and the delivery hospitalization. Maternal race was self-reported. Cases and controls also had a uniform placental pathology evaluation, and cases had a comprehensive standardized fetal postmortem examination (15,16). Both were performed by a perinatal pathologist. Treating physicians were advised to obtain clinically recommended tests (17) including anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant in cases of stillbirth. However, such testing was performed at the discretion of the clinicians and was not done in each case. In addition, attempts were made to collect maternal blood for serum and DNA, fetal blood from the umbilical cord (when available), placental tissue in cases and controls, and fetal tissue in cases around the time of delivery or enrollment. Maternal serum was stored at −80°C for 2–5 years prior to assay.

Maternal serum samples in all cases (regardless of whether or not they had clinically indicated antiphospholipid antibody testing) and all controls (with adequate sample) were tested for antiphospholipid antibodies in the Branch Perinatal Laboratory (University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, UT). Serum samples were tested for anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I IgG and IgM antibodies using kits from INOVA Diagnostics (San Diego, CA). Testing was performed in duplicate by experienced laboratory personnel blinded to patients’ clinical diagnosis using procedures recommended by the manufacturer. The thresholds to define elevated values for the anti-β2-glycoprotein-I and anticardiolipin assays were determined by the manufacturer (INOVA) using a percentile-based method (99 % or more of a healthy population) as previously described (18,19). Positive results were defined as 20 or more units IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies, and 20 or more units IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies.

The Initial Causes of Fetal Death (INCODE) system developed by the SCRN was used to assign causes of death to each case (20). Each case of stillbirth was reviewed by two physicians, and difficult cases were evaluated and adjudicated by a multidisciplinary panel with expertise in genetics and perinatal pathology (21). Some analyses were performed on subsets of cases and controls, including nonanomalous stillbirths and stillbirths without obstetric complications as previously described (14). Nonanomalous stillbirths excluded those stillbirths with possible or probable causes of stillbirth that included fetal genetic, structural and karyotypic abnormalities (20). Cases with possible or probable causes of stillbirth including fetal–maternal hemorrhage, cervical insufficiency, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes, clinical chorioamnionitis, intrapartum death, abruption, complications of multiple gestation, and uterine rupture were excluded in the subset of stillbirths without obstetric complications (20).

The delivery, defined as a case if there were any stillbirths delivered and as a control if all live births were delivered, was the unit of analysis. The analyses were weighted for oversampling and other aspects of the study design as well as for differential consent using SUDAAN software, Version 10.0 (22). Construction of the weights has been previously described (12). Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from univariate and multivariable logistic regression models. All tests were performed at a nominal significance level of α=0.05. All single degree of freedom tests were 2-sided.

The adjusted ORs account for stillbirth risk factors known at pregnancy confirmation (baseline) using a modification to a risk factor score for stillbirth that was developed on the logit scale using the coefficients from a logistic regression model. The model used data on all SCRN deliveries where a maternal interview was conducted and a prenatal chart was abstracted. Variables contributing to the baseline risk factor score were those described previously (14) and included the following maternal characteristics: age, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, pregnancy history, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, illicit drug use, hypertension, diabetes, seizure disorder, blood type, Rh factor, and multiple gestation in current pregnancy; as well as paternal age, family income, insurance and method of payment, and clinical site. All variables included in the score were categorical and a weighted average of the regression coefficients associated with the categories was used when a variable was missing for an observation. The weights were taken as the sample weighted proportion of live births by category. There were very few missing values, as previously noted (14). The modification to the risk factor score for this analysis was to exclude coefficients associated with pregnancy history.

Results

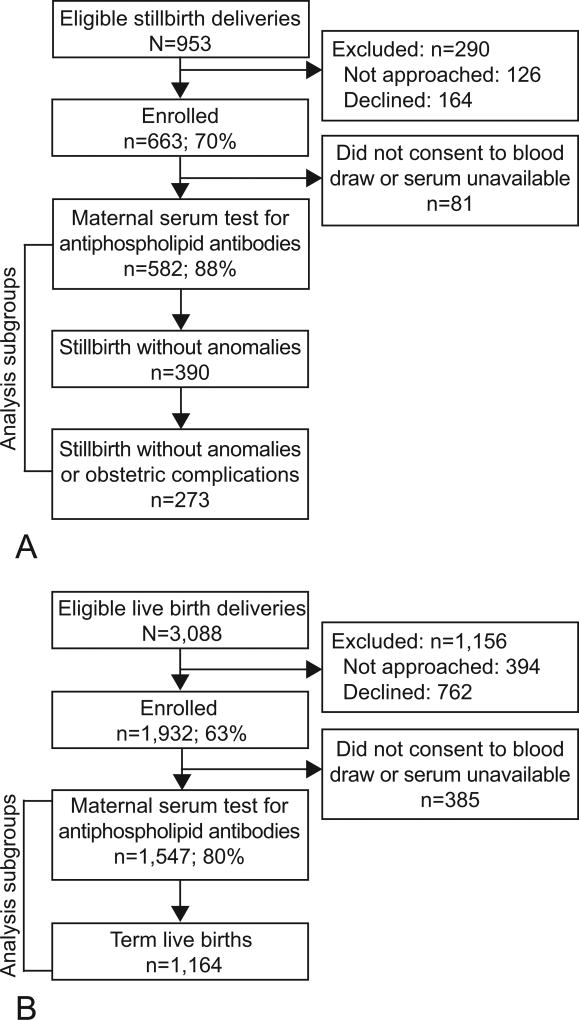

Figure 1 depicts enrollment to the SCRN and inclusion in this analysis. A total of 582 deliveries with stillbirth and 1,547 with live births had blood available and assessment of anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibody levels. Cases that did and did not enroll in the SCRN were similar with regard to maternal age, maternal race and ethnicity, insurance and method of payment, and gestational age at delivery. Controls that did not enroll differed from those who enrolled by maternal race and ethnicity and gestational age at delivery (21). The demographic characteristics of the SCRN study participants have been published (14,21). Among women with stillbirth, those women refusing blood draw were more likely to be non-Hispanic black and nulliparous than those consenting (Table 1). Women with live births who were non-Hispanic black, younger than 20 years or 40 years and older, and did not receive early prenatal care were more likely to refuse blood draw (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and inclusion in antiphospholipid antibody analysis for A. stillbirth deliveries, B. live birth deliveries. A pregnancy was categorized as a stillbirth pregnancy if there were any stillbirths delivered and as a live birth pregnancy if all live births were delivered. A fetal death was defined by Apgar scores of 0 at 1 and 5 minutes and no signs of life by direct observation. Fetal deaths were classified as stillbirths if the best clinical estimate of gestational age at death was 20 weeks or more. Fetal deaths at 18 weeks and 19 weeks without good dating were also included as stillbirths. The analysis includes comparison of all stillbirths to all live births, all stillbirths to term live births, nonanomalous stillbirths to term live births, and nonanomalous stillbirths without obstetric complications to term live births.

Table 1.

Comparison of Women Who Were Tested For Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Serum and Those Who Were Not Tested by Pregnancy Outcome

| Characteristic | Stillbirths | Live Births | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Antibody Testing | Antibody Testing | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Yes | No | P | Yes | No | P | |

| Unweighted sample size, n | 582 | 81 | 1,547 | 385 | ||

| Weighted sample size, n | 579 | 84 | 1,184 | 255 | ||

| Maternal age at delivery, years | ||||||

| Younger than 20 | 13.0% | 14.5% | 0.731 | 9.5% | 13.9% | 0.024 |

| 20–34 | 70.1% | 66.9% | 76.5% | 71.7% | ||

| 35–39 | 12.0% | 15.4% | 12.3% | 10.2% | ||

| 40 and older | 4.9% | 3.3% | 1.7% | 4.1% | ||

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 35.7% | 17.7% | <0.001 | 47.4% | 38.6% | <.001 |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 20.7% | 41.6% | 9.4% | 22.6% | ||

| Hispanic | 37.0% | 31.5% | 36.0% | 29.4% | ||

| Other | 6.6% | 9.1% | 7.2% | 9.4% | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Not married or cohabitating | 25.0% | 27.7% | 0.648 | 14.9% | 17.3% | 0.454 |

| Cohabitating | 25.5% | 29.1% | 23.7% | 25.2% | ||

| Married | 49.5% | 43.2% | 61.4% | 57.5% | ||

| Maternal education, years | ||||||

| 0–11 (none, primary, some secondary) | 23.5% | 25.8% | 0.669 | 18.3% | 18.5% | 0.816 |

| 12 (completed secondary) | 29.2% | 33.0% | 25.5% | 27.4% | ||

| 13 or more (college) | 47.3% | 41.2% | 56.2% | 54.1% | ||

| Insurance and method of payment | ||||||

| No insurance | 5.3% | 10.1% | 0.238 | 3.6% | 3.2% | 0.439 |

| Any public or private assistance | 53.8% | 51.8% | 47.9% | 52.3% | ||

| VA, commercial health insurance, or HMO | 40.9% | 38.2% | 48.5% | 44.6% | ||

| Income | ||||||

| Only public or private assistance | 9.3% | 3.7% | 0.356 | 5.9% | 5.9% | 0.704 |

| Assistance and personal income | 38.0% | 36.8% | 37.0% | 39.8% | ||

| Only personal income | 52.7% | 59.5% | 57.1% | 54.2% | ||

| No first or second trimester prenatal care | 7.3% | 12.7% | 0.120 | 2.5% | 4.7% | 0.031 |

| Gestational age, weeks | ||||||

| 18–19 | 2.3% | 3.8% | 0.137 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.253 |

| 20–23 | 32.0% | 46.8% | 0.4% | 0.3% | ||

| 24–27 | 15.9% | 15.6% | 0.7% | 1.0% | ||

| 28–31 | 13.1% | 10.3% | 1.0% | 1.2% | ||

| 32-26 | 19.8% | 11.7% | 8.2% | 10.6% | ||

| 37 or more | 16.9% | 11.9% | 89.8% | 86.9% | ||

| Nulliparous | 43.3% | 56.7% | 0.029 | 34.6% | 38.9% | 0.213 |

| Multifetal pregnancy | 6.5% | 4.3% | 0.421 | 1.7% | 2.9% | 0.240 |

VA, Veterans Affairs;. HMO, health maintenance organization

Results are weighted for the study design and differential consent based on characteristics recorded in the screened population. Overall sample sizes are given, unweighted and weighted. Sample sizes for the weighted percentages vary slightly by characteristic.

Abnormal levels of anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies in all stillbirths compared with all live births are shown in Table 2. The proportion of deliveries with elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin antibodies was higher in cases compared with controls (3.8% versus 1.1%; (OR 3.43, 95% CI 1.79, 6.60). The same was true for IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies (OR 3.17; 95% CI 1.30, 7.72). However, similar proportions of deliveries with stillbirth and with live births had elevated levels of IgM anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies. The OR for at least one positive antibody test was 1.63 (95% CI 1.13, 2.35). Results were similar for adjusted odds ratios (Table 2).

Table 2.

Abnormal Antiphospholipid Antibody Levels in All Stillbirths, All Live Births, and in Term Live Births

| Antibody | Stillbirths | Live Births |

Term Live Births* |

Stillbirths vs Live Births OR (95% CI) |

Stillbirths vs Term Live Births OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Crude | Adjusted† | Crude | Adjusted† | ||||

| Unweighted sample size, n | 582 | 1,547 | 1,164 | ||||

| Weighted sample size, n | 579 | 1,184 | 1,063 | ||||

| IgG anticardiolipin | 3.8% | 1.1% | 1.0% | 3.43 (1.79, 6.60) | 3.02 (1.47, 6.21) | 3.98 (1.96, 8.07) | 3.57 (1.64, 7.74) |

| IgM anticardiolipin | 3.4% | 3.1% | 3.0% | 1.10 (0.63, 1.92) | 1.16 (0.63, 2.11) | 1.13 (0.64, 2.00) | 1.17 (0.62, 2.21) |

| IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I | 1.9% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 3.17 (1.30, 7.72) | 3.04 (1.13, 8.19) | 3.03 (1.20, 7.62) | 2.91 (1.03, 8.25) |

| IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I | 2.7% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.42 (0.73, 2.76) | 1.07 (0.51, 2.21) | 1.45 (0.73, 2.89) | 1.06 (0.49, 2.29) |

| Abnormal level of one or more antibody | 9.6% | 6.1% | 5.9% | 1.63 (1.13, 2.35) | 1.54 (1.04, 2.29) | 1.68 (1.15, 2.45) | 1.60 (1.06, 2.43) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Abnormal antibody levels are defined as 20 or more units of IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units of IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units of IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies and 20 or more units of IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies.

Results shown are weighted for the study design and differential consent based on characteristics recorded on all eligible pregnancies that were screened for the study. Overall sample sizes are given, un-weighted and weighted.

Defined as gestational age of 37 weeks or more at time of birth

The adjusted odds ratios account for pre-pregnancy risk factors for stillbirth using a modification to a score developed on the logit scale and using data on all participants to the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Variables contributing to the baseline risk factor score included the following maternal characteristics: age, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, pregnancy history, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, illicit drug use, hypertension, diabetes, seizure disorder, blood type, Rh factor, and multiple gestation in current pregnancy; as well as paternal age, family income, insurance and method of payment and clinical site. The modification to the risk factor score for this analysis is to exclude coefficients associated with pregnancy history. The score is available on 553 of the 582 stillbirth pregnancies, 1,499 of the 1,547 live birth pregnancies, and 1,132 of the 1,164 term live birth pregnancies.

Table 2 also shows levels of anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies in all stillbirths compared with term live births. Results were similar to the comparison between all stillbirths and all live births. Women having a stillbirth were more likely to have elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies than women having a term live birth.

Similar results also were noted when the subset of nonanomalous stillbirths was compared with term live births (Table 3). A greater percentage of women with nonanomalous stillbirths had elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin antibodies (4.8%) compared with those with term live births (1.0%; OR 5.09 (2.44, 10.65). A positive test for IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies yielded an OR of 2.87 (95% CI 1.05, 7.88) for stillbirth. Positive tests for IgM anticardiolipin and IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were similar between groups. Having 1 or more positive test for an antibody was associated with a 2.02 OR (95% CI 1.34, 3.05) for stillbirth.

Table 3.

Abnormal Antiphospholipid Antibody Levels in Nonanomalous Stillbirths, Nonanomalous Stillbirths Without Obstetric Complications, and Term Live Births

| Antibody | Nonanomalous Stillbirths |

Nonanomalous Stillbirths Without Complications |

Term Live Births* |

Nonanomalous Stillbirths vs Term Live Births OR (95% CI) |

Nonanomalous Stillbirths Without Complications vs Term Live Births OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Crude | Adjusted† | Crude | Adjusted† | ||||

| Unweighted sample size, n | 390 | 273 | 1,164 | ||||

| Weighted sample size, n | 387 | 268 | 1,063 | ||||

| IgG anticardiolipin | 4.8% | 5.0% | 1.0% | 5.09 (2.44, 10.65) | 4.16 (1.84, 9.40) | 5.30 (2.39, 11.76) | 3.96 (1.74, 8.98) |

| IgM anticardiolipin | 5.0% | 6.0% | 3.0% | 1.66 (0.93, 2.97) | 1.68 (0.88, 3.21) | 2.03 (1.09, 3.76) | 1.99 (1.01, 3.94) |

| IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I | 1.8% | 1.9% | 0.6% | 2.87 (1.05, 7.88) | 2.88 (0.99, 8.35) | 3.00 (1.01, 8.90) | 2.84 (0.93, 8.66) |

| IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I | 3.1% | 2.5% | 1.9% | 1.68 (0.79, 3.56) | 1.31 (0.59, 2.89) | 1.32 (0.54, 3.25) | 1.12 (0.43, 2.92) |

| Abnormal level of one or more antibody | 11.3% | 11.7% | 5.9% | 2.02 (1.34, 3.05) | 1.93 (1.24, 2.99) | 2.11 (1.33, 3.33) | 1.95 (1.21, 3.15) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Abnormal levels are defined as 20 or more units of IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units of IgM anticardiolipin antibodies, 20 or more units of IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies and 20 or more units of IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies.

Results shown are weighted for the study design and differential consent based on characteristics recorded on all eligible pregnancies that were screened for the study. Overall sample sizes are given, un-weighted and weighted.

Defined as gestational age of 37 weeks or more at time of birth

The adjusted odds ratios account for pre-pregnancy risk factors for stillbirth using a modification to a score developed on the logit scale and using data on all participants to the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Variables contributing to the baseline risk factor score included the following maternal characteristics: age, race and ethnicity, marital status, education, pregnancy history, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol use, illicit drug use, hypertension, diabetes, seizure disorder, blood type, Rh factor, and multiple gestation in current pregnancy; as well as paternal age, family income, insurance and method of payment and clinical site. The modification to the risk factor score for this analysis is to exclude coefficients associated with pregnancy history. The score is available on 377 of the 390 nonanomalous stillbirth pregnancies, 262 of the 273 nonanomalous stillbirth pregnancies without obstetric complications, and 1,132 of the 1,164 term live birth pregnancies.

Table 3 also depicts antibody results in women with stillbirth not associated with fetal anomalies or obstetric complications compared with women with term live births. IgG anticardiolipin antibodies were associated with a fivefold odds of stillbirth and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies were associated with a twofold odds of stillbirth. IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were associated with a threefold odds of stillbirth, but IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were not associated with stillbirth. Of these specific stillbirth deliveries, 11.7% had at least one positive test for antiphospholipid antibodies compared with 5.9% of those with term live births (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.33, 3.33).

We explored whether a threshold of 40 or more units of IgG or IgM anticardiolipin or anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies was more strongly associated with stillbirth than using a threshold of 20 or more units. For each of the four antibodies and in each of the subgroups of stillbirth and live birth analyzed, a threshold of 40 units was not more strongly associated with stillbirth than a threshold of 20 units (data not shown).

We then assessed the clinical characteristics of the cases with positive tests for antiphospholipid antibodies in hopes of identifying specific scenarios that merit testing. Details for each case are shown in Table 4. In this study, there were 56 deliveries with stillbirth (including three sets of twins, one with two stillbirths and two with a live birth and a stillbirth) and at least one positive test for antiphospholipid antibodies. In these cases, a history of thrombosis was noted in one (1.8%) and none had systemic lupus erythematosus. Pregnancy complications included preeclampsia in six of 53 (11.3%), small-for-gestational-age (SGA) fetus in 20 of 54 (37.0%), and clinical or histologic evidence of abruption in 14 of 56 (25.0%). Of the 50 stillbirths with a complete postmortem examination, 7 (14%) had APS as a probable cause of death based on INCODE criteria. It is noteworthy that many other cases in this subset of 57 stillbirths had a likely cause of death other than APS. One case of interest was congenital syphilis, which is known to cause antiphospholipid antibody production. In this cohort of 56 women with positive tests for antiphospholipid, 22 (39.3%) had no history of (prior) pregnancy loss, thrombosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, SGA fetus or preeclampsia. Thus, we were unable to ascertain clinical features that would allow testing only a subset of patients with stillbirth for antiphospholipid.

Table 4.

Stillbirths With Positive Antiphospholipid Antibody Results

| Ca se ID |

Pregn ancy Outc omes |

IgG Anticard iolipin Antibod ies (Units) |

IgM Anticard iolipin Antibod ies (Units) |

IgG Anti- β2- glycopr otein-I Antibo dies (Units) |

IgM Anti- β2- glycopr otein-I Antibo dies (Units) |

Gestat ional Age Repor ted at Scree ning (wk) |

SG A |

Pregna ncy Histor y |

Throm bosis (chart review ) |

Preecla mpsia or Gestati onal HTN (chart review) |

Place ntal Abru ption (chart revie w) |

Retro - place ntal Hema toma (place nta pathol ogy) |

Lupus Anticoa gulant (chart review) |

Cause of Death : Possi ble or Proba ble APS (INC ODE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LB/SB | 23 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 36 | Yes/Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | Yes | No | ND | ND | No |

| 2 | SB/SB | 8 | 6 | 24 | 9 | 22 | No/No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | ND | ND | No/No |

| 3 | SB | 10 | 7 | 21 | 5 | 26 | Yes | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | SB | 12 | 26 | 4 | 5 | 38 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 5 | SB | 7 | 11 | 23 | 5 | 23 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | SB | 6 | 14 | 33 | 17 | 20 | No | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 7 | SB | 6 | 13 | 5 | 24 | 23 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 8 | SB | 101 | 10 | 63 | 6 | 29 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | Yes | No | No | No | ND | Probable cause |

| 9 | SB | 4 | 13 | 5 | 22 | 40 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | Yes | Yes | ND | No |

| 10 | SB | 6 | 57 | 5 | 6 | 39 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | Possible cause |

| 11 | SB | 8 | 24 | 4 | 108 | 32 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | Yes | No | No | ND | No |

| 12 | SB | 8 | 11 | 5 | 20 | 20 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | ND |

| 13 | SB | 4 | 32 | 3 | 3 | 36 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 14 | SB | 7 | 15 | 4 | 26 | 23 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 15 | SB | 22 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 20 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 16 | SB | 23 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 22 | Yes | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | No | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 17 | SB | 6 | 25 | 3 | 22 | 22 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | Yes | No | ND | No |

| 18 | SB | 42 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 21 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | Yes | ND | Possible cause |

| 19 | SB | 7 | 30 | 61 | 12 | 21 | DK | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 20 | SB | 20 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 23 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | Yes | Yes | ND | No |

| 21 | SB | 5 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 21 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 22 | SB | 11 | 11 | 5 | 28 | 21 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | ND | ND | No |

| 23 | SB | 21 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 20 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | ND | ND | ND |

| 24 | SB | 66 | 19 | 29 | 24 | 20 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | No | ND | Possible cause |

| 25 | SB | 20 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 28 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 26 | SB | 24 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 21 | No | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | No | No | No | ND | ND |

| 27 | SB | 5 | 16 | 3 | 23 | 20 | No | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 28 | SB | 32 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 33 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 29 | SB | 7 | 12 | 4 | 23 | 27 | Yes | Muliparous with stillbirth | No | Yes | No | DK | No | No |

| 30 | SB | 151 | 56 | 111 | 5 | 27 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | Yes | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 31 | SB | 6 | 42 | 3 | 9 | 27 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | Possible cause |

| 32 | SB | 28 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 26 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | Yes | ND | No |

| 33 | SB | 4 | 7 | 28 | 3 | 23 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | ND |

| 34 | SB | 8 | 25 | 4 | 13 | 35 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 35 | SB | 28 | 29 | 4 | 6 | 31 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 36 | SB | 6 | 25 | 3 | 10 | 35 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 37 | SB | 6 | 11 | 4 | 49 | 33 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | ND | ND | No |

| 38 | SB | 5 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 38 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 39 | SB | 23 | 15 | 12 | 54 | 23 | No | Nulliparous with previous losses | No | DK | Yes | Yes | ND | No |

| 40 | SB | 24 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 37 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

| 41 | SB | 6 | 14 | 31 | 6 | 27 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | Yes | DK | No | ND | No |

| 42 | SB | 42 | 31 | 25 | 73 | 22 | Yes | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | No | Yes | Probable cause |

| 43 | SB | 7 | 20 | 4 | 3 | 37 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 44 | SB | 6 | 71 | 3 | 4 | 38 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | ND |

| 45 | SB | 8 | 10 | 15 | 24 | 36 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | DK | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 46 | SB | 22 | 23 | 4 | 10 | 20 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | ND | No | No |

| 47 | SB | 6 | 14 | 45 | 5 | 26 | No | Muliparous with stillbirth | No | No | No | No | ND | ND |

| 48 | LB/SB | 5 | 21 | 3 | 14 | 24 | No/DK | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | ND | No | No |

| 49 | SB | 9 | 23 | 3 | 7 | 39 | No | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 50 | SB | 7 | 12 | 4 | 137 | 20 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 51 | SB | 9 | 15 | 4 | 36 | 26 | Yes | Nulliparous; never pregnant or only elective terminations | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 52 | SB | 6 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 23 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 53 | SB | 35 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 34 | No | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | No | No | Possible cause |

| 54 | SB | 20 | 18 | 7 | 4 | 23 | Yes | Multiparous with stillbirth | No | DK | Yes | No | No | No |

| 55 | SB | 34 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 20 | Yes | Multiparous with no previous losses at < 20 wk or stillbirths | No | No | No | ND | No | No |

| 56 | SB | 21 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 30 | No | Multiparous with no stillbirth but previous losses at < 20 wk | No | No | No | No | ND | No |

SGA, small for gestational age; HTN, hypertension; APS, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; INCODE, Initial Causes of Fetal Death; LB, live birth; SB, stillbirth; ND, not done; DK, don’t know.

These cases include 56 pregnancies with 57 stillbirths. Among these were 3 sets of twins.

Another important question is whether it is necessary to test for all four antibodies assessed in this study. Forty-six of the 56 (82.1%) women having a positive test result tested positive for only one of the four antibodies. Thus, not testing for any one of the antibodies would have potentially missed some cases. Only 19 patients with stillbirth had clinically-indicated testing for lupus anticoagulant, and two of these were positive.

Discussion

Elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were associated with an approximate threefold increased odds of stillbirth when all stillbirth deliveries are compared with all live birth deliveries. However, levels of IgM anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies were similar among groups. Women with stillbirth had an approximately 1.6-fold risk for having at least one positive antibody compared with those with live births.

When the subset of stillbirths not associated with fetal anomalies or obstetric complications was compared with term live births, elevated IgG anticardiolipin antibodies were associated with an OR of 5.30 (95% CI 2.39, 11.76) for stillbirth. The OR for IgM anticardiolipin antibodies was 2.03 (95% CI 1.09, 3.76) and the OR for IgG anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies was 3.00 (95% CI, 1.01, 8.90). Stillbirth was not significantly associated with IgM anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies. The OR for stillbirth among women with 1 or more positive antibody test versus none was 2.11 (95% CI 1.33, 3.33).

These data confirm and quantify the previously suspected association between antiphospholipid antibodies and stillbirth. A meta-analysis of 25 studies noted an OR for late recurrent fetal loss of 3.57 (95% CI 2.26, 5.65) for any positive test for anticardiolipin antibodies (23). The OR for recurrent pregnancy loss in women with medium-to-high titer IgG anticardiolipin antibodies was 4.68 (95% CI 2.96, 7.40) (23). Although some women with stillbirth were included in these studies, most pregnancy losses were prior to 20 weeks of gestation, and all were less than 24 weeks of gestation (23).

In addition, the women in the meta-analysis had recurrent, rather than sporadic pregnancy loss. In contrast, our study is one of the few to address sporadic stillbirth. It is noteworthy that antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with recurrent early pregnancy loss (23) but not sporadic early pregnancy loss (24). This is expected since sporadic early pregnancy loss is common and usually due to genetic abnormalities. In contrast to early pregnancy loss, even a single fetal death after 20 weeks of gestation is considered to be clinical evidence of APS. Thus, our data support the Sapporo obstetric criteria for APS that include sporadic fetal death.

It is noteworthy that 56 of 582 (9.6 %) women with stillbirth had positive tests for antiphospholipid antibodies. It is unclear that all of these cases will prove to have APS since antibody levels in many cases were lower than those considered diagnostic of APS and they were not systematically assessed 12 weeks after the initial assay. Some cases had other potential causes of stillbirth, and many had only modestly elevated levels of antibodies. There were many cases wherein the only clinical evidence of APS was unexplained stillbirth. Fourteen of these cases had very high levels (greater than 40 units) of antibodies. Thus, it seems as though testing all women with unexplained stillbirth is a reasonable approach to the workup of stillbirth. Also, although IgG anticardiolipin antibodies were most strongly associated with stillbirth, testing for all four antibodies assessed in this study can identify additional women with potential APS compared with testing for IgG anticardiolipin antibodies alone.

It is important for clinicians to be aware that 6% of live births had at least one positive test for antiphospholipid antibodies. Thus, a positive test is not diagnostic of APS. It is critical to be sure that the stillbirth is otherwise unexplained when considering a diagnosis of APS. It is also imperative to repeat testing since positive tests may be transient. Finally, it should be understood that low positive test results (eg, levels between 20 units and 40 units) are not diagnostic of APS and that treatment is not proven to be efficacious in such cases (2).

There were several weaknesses of our study. We did not assess lupus anticoagulant in each patient since we did not have available plasma. Second, women did not have serial assessment of antiphospholipid antibodies. These autoantibodies may fluctuate over time, and it is necessary to have elevated levels persist on two occasions at least 12 weeks apart to be considered diagnostic of APS (2). Third, we did not have detailed information regarding the possible influence of treatment for APS as we might be able to obtain in a longitudinal cohort study. Finally, the slight differences in women who did and did not agree to blood draw may limit the generalizability of our data.

The study also had numerous strengths. It is one of the few studies of antiphospholipid that was population based, providing reliable estimates of the association of stillbirth with antiphospholipid antibodies. It also involved a geographically, racially, and ethnically diverse population, enhancing the generalizability of the results. In addition, it is one of the largest studies of antiphospholipid antibodies and stillbirth, including almost 600 cases. Importantly, participants underwent an extensive evaluation for other potential causes of stillbirth. Finally, the laboratory performing the antiphospholipid antibody assays was blinded to clinical status of the samples.

In summary, elevated levels of IgG anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein-I antibodies are associated with a threefold to fivefold increased odds of stillbirth. IgG anticardiolipin antibodies are more strongly associated with stillbirth than IgM antibodies. Almost 10% of participants with stillbirth had positive tests for antiphospholipid antibodies, and several had APS as a possible or probable cause of death. Our data support consideration of testing for antiphospholipid in cases of otherwise unexplained stillbirth.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Scientific Advisory and Safety Monitoring Board for their review of the study protocol, materials, and progress: Reverend Phillip Cato, Ph.D.; James W. Collins Jr., M.D., M.P.H.; Terry Dwyer, M.D., M.P.H.; William P. Fifer, Ph.D.; John Ilekis, Ph.D.; Marc Incerpi, M.D.; George Macones, M.D., M.S.C.E.; Richard M. Pauli, M.D., Ph.D.; Raymond W. Redline, M.D.; Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D. (chair), as well as all of the other physicians, study coordinators, research nurses, and patients who participated in the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. For a list of centers participating in the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. The authors also thank Dr. Huixia Yu for assistance in performing the assays and Susan Fox for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: U10-HD045953 Brown University, Rhode Island; U10-HD045925 Emory University, Georgia; U10-HD045952 University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas; U10-HDO45955 University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Texas; U10-HD045944 University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Utah; and U01-HD045954 RTI International, RTP.

Appendix

List of Centers in the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) is as follows: University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio — Donald J. Dudley, Deborah Conway, Josefine Heim-Hall, Karen Aufdemorte, Angela Rodriguez; University of Utah School of Medicine and Intermountain Health Care — Robert M. Silver, Michael W. Varner, Kristi Nelson; Emory University School of Medicine, the Rollins School of Public Health, and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta — Carol J. Rowland Hogue, Barbara J. Stoll, Janice Daniels Tinsley, Bahig Shehata, Carlos Abramowsky; Brown University — Donald Coustan, Halit Pinar, Marshall Carpenter, Susan Kubaska; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: George R. Saade, Radek Bukowski, Jennifer Lee Rollins, Hal Hawkins, Elena Sbrana; RTI International — Corette B. Parker, Matthew A. Koch, Vanessa R. Thorsten, Holly Franklin, Pinliang Chen; Pregnancy and Perinatology Branch, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health — Marian Willinger, Uma M. Reddy; and Columbia University School of Medicine — Robert L. Goldenberg.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors provided this information as a supplement to their article.

References

- 1.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 118: Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:192–199. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820a61f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branch DW, Silver RM, Blackwell JL, Reading JC, Scott JR. Outcome of treated pregnancies in women with antiphospholipid syndrome: an update of the Utah experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lima F, Khamashta MA, Buchanan NM, et al. A study of sixty pregnancies in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996;14:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi D, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meroni PL, Tedesco F, Locati M, et al. Antiphospholipid antibody mediated fetal loss: still an open question from a pathogenic point of view. Lupus. 2010;19:453–456. doi: 10.1177/0961203309361351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:189–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein SR. Embryonic death in early pregnancy: a new look at the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver RM, Branch DW, Goldenberg R, Iams JD, Klebanoff MA. Nomenclature for pregnancy outcomes. Time for a change. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1402–1408. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182392977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oshiro BT, Silver RM, Scott JR, Yu H, Branch DW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and fetal death. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockwood CJ, Romero R, Feinberg RF, Clyne LP, Coster B, Hobbins JC. The prevalence and biologic significance of lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies in a general obstetric population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:369–373. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Report of the Obstetric Task Force, 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid antibodies. Lupus. 2011;20:158–164. doi: 10.1177/0961203310395054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker CB, Hogue CJR, Koch MA, Willinger M, Reddy U, Thorsten VR, Dudley DJ, Silver RM, Coustan D, Saade GR, Conway D, Varner MW, Stoll B, Pinar H, Bukowski R, Carprenter M, Goldenberg R for the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network: Design, methods and recruitment experience. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2011;25:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Metranidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatoc bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:534–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing group. Bukowski Radek, MD, Carpenter Marshall, MD, Conway Deborah, MD, Coustan Donald, MD, Dudley Donald J, MD; MD, Koch Matthew A, MD, PhD, Goldenberg Robert, MD, Hogue Carol J Rowland, PhD, Parker Corette B, DrPH, Pinar Halit, MD, Reddy Uma M, MD, MPH, Saade George R, MD, Silver Robert M, MD, Stoll Barbara, MD, Varner Michael W, MD, Willinger Marian., PhD Association between stillbirth and risk factors known at pregnancy confirmation. JAMA. 2011;306:2469–2479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinar H, Koch MA, Hawkins H, Heim-Hall J, Shehata B, Thorsten VR, Carpenter MW, Lowichik A, Reddy UM. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) Placental and Umbilical Cord Examination. Am J Perinatol. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281509. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinar H, Koch MA, Hawkins H, Heim-Hall J, Abramowsky CR, Thorsten VR, Carpenter MW, Zhou HH, Reddy UM. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) Postmortem Examination Protocol. Am J Perinatol. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284228. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:748–761. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819e9ee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis S, Keil LB, Binder WL, DeBari VA. Standardized measurement of major immunoglobulin class (IgG, IgA, and IgM) antibodies to beta2glycoprotein I in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal. 1998;12(5):293–297. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1998)12:5<293::AID-JCLA8>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tebo AE, Jaskowski TD, Hill HR, Branch DW. Clinical relevance of multiple antibody specificity testing in antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrent pregnancy loss. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154(3):332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley DJ, Goldenberg R, Conway D, Silver RM, Saade G, Varner MV, Pinar H, Coustan D, Bukowski R, Stoll B, Koch M, parker C, Willinger M, Reddy UM. Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network: Initial Causes of Fetal Death (INCODE) Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:254–260. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e7d975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing group. Bukowski Radek, MD, Carpenter Marshall, MD, Conway Deborah, MD, Coustan Donald, MD, Dudley Donald J, MD; MD, Koch Matthew A, MD, PhD, Goldenberg Robert, MD, Hogue Carol J Rowland, PhD, Parker Corette B, DrPH, Pinar Halit, MD, Reddy Uma M, MD, MPH, Saade George R, MD, Silver Robert M, MD, Stoll Barbara, MD, Varner Michael W, MD, Willinger Marian., PhD Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011;306:2459–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 10.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opatrny L, David M, Kahn SR, Rey E. Association between antiphospholipid antibodies and recurrent fetal loss in women without autoimmune disease: a metaanalysis. J Rhematol. 2006;33:2214–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Infante-Rivard C, David M, Gauthier R, Rivard GE. Lupus anticoagulants, anticardiolipin antibodies, and fetal loss. A case-control study. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(15):1063–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110103251503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]