Abstract

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is a rare cause of stroke, which is routinely treated with systemic heparin. Unfavourable outcome is often seen in severe cases. Therefore alternative treatment methods should be explored in these patients. Due to the risk of haemorrhagic complications, treatment without administration of thrombolytics is of particular interest. This report presents a case of successful mechanical thrombectomy, without the use of thrombolytics, in a comatose patient with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Keywords: Angiography, intervention, stroke, thrombectomy, vein

Introduction

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVT) is a rare cause of stroke with an incidence of 13–16 per million annually.1,2 Currently, most patients with CVT are treated with unfractioned or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) as recommended by international guidelines.3 However, incomplete recovery after CVT is observed in about 20% of patients despite optimal medical management with heparin. For severe CVT these numbers are even more striking since more than 55% of these patients did not reach functional dependence or died at a median follow-up of 2.5 years.4 Therefore the value of additional treatment such as systemic thrombolysis or endovascular treatment is currently being investigated.5,6 Endovascular treatment includes local administration of thrombolytic drugs and clot removal via aspiration catheters or stent-retrievers. Since intracerebral haemorrhages are commonly observed in patients with CVT,4 endovascular treatment without local administration of a thrombolytic agent is of particular interest. We present a case of successful mechanical thrombectomy, without the (local) use of thrombolytics, in a comatose patient with an intracerebral haemorrhage due to CVT.

Case report

A 32-year old male pianist, with a history of superficial venous thrombosis of the dorsal vein of the penis (Mondor’s disease), presented to our emergency department with a decreased level of consciousness and epileptic seizures. First symptoms had started a few days earlier with severe headache. Neurological examination at presentation showed a Glasgow Coma scale of E1M5V2, anisocoria, left-sided hemiparesis and bilateral Babinskis. His family history was positive for deep venous thrombosis of the leg in both his father and brother.

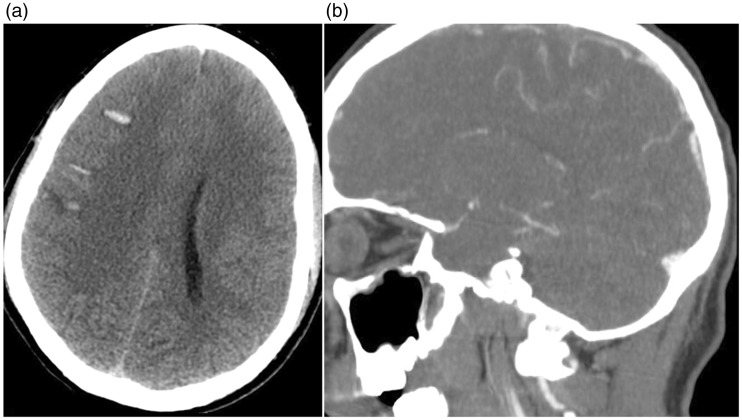

Non-contrast computed tomography showed both subarachnoid and intraparenchymal haemorrhage with mild midline shift (Figure 1(a)). CT angiography revealed a contrast filling defect in the superior sagittal sinus, indicating CVT (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Non-contrast computed tomography, axial view. Subarachnoid and intraparenchymal haemorrhage at the convexity of the brain on both sides, right more than left (a). Computed tomography angiography, sagittal view. Contrast filling defect in the superior sagittal sinus (b).

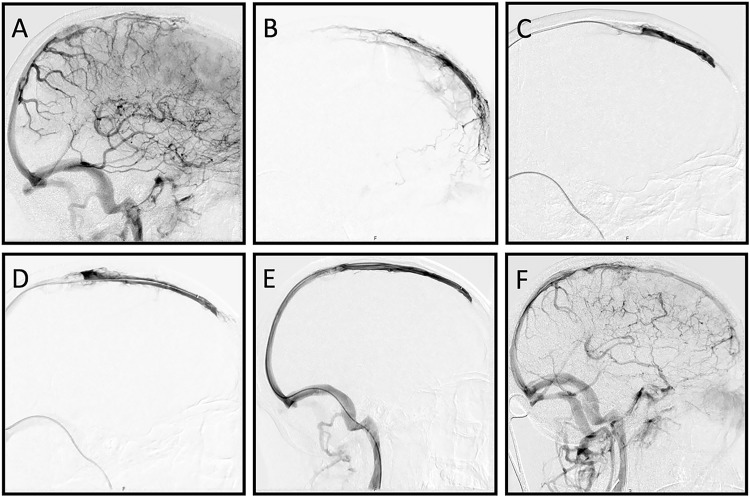

Immediate treatment with LMWH (in therapeutic dose) was started. Because of the severity of the neurological deficits subsequent mechanical thrombectomy was initiated approximately 24 h after onset of neurological deficits. Informed consent was obtained. A 4 French diagnostic catheter was placed in the right internal carotid artery. Digital subtraction angiography showed extensive thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) (Figure 2(a)). For intravenous treatment an 8 French sheath was placed in the right jugular vein, using the transfemoral route. Selective angiography showed patency of the anterior part of the SSS (Figure 2(b)). An attempt to remove the thrombus by aspiration, both manually and using an aspiration pump, was not successful. Subsequently mechanical thrombectomy with a 6 mm × 25 mm Trevo stentriever was performed. After three passes (Figure 2(c) to (e)) complete recanalization of the SSS was seen with normalization of the venous outflow (Figure 2(f)). Following mechanical thrombectomy an excellent clinical improvement was observed, with complete recovery of mental status and only mild paresis of the left arm. Factor II (prothrombin) mutation was later established. Ten days after mechanical thrombectomy our patient was discharged in good clinical condition and referred to an ambulant rehabilitation programme. After three weeks we switched LMWH to oral anticoagulant therapy (vitamin K antagonist). Anti-epileptic drugs were discontinued because no recurrent epileptic seizures had occurred.

Figure 2.

Digital subtraction angiography images, lateral views. After contrast injections in the right internal carotid artery (ICA) the venous phase confirms the occlusion of the mid to anterior part of the superior sagittal sinus (SSS) (a). A mild to moderate pseudo-phlebetic pattern of tortuous cortical veins as a response to venous congestion is also noted. Selective angiography of the SSS shows patency of the most anterior part of the SSS (b). Thrombectomy using a Trevo 6 mm × 25 mm stent retriever results in increasing recanalization after the first (c) and the second (d) stent pass. Complete recanalization is achieved after three passes (e). Contrast injection in the right ICA shows improved venous drainage through the SSS and diminished venous congestion (f).

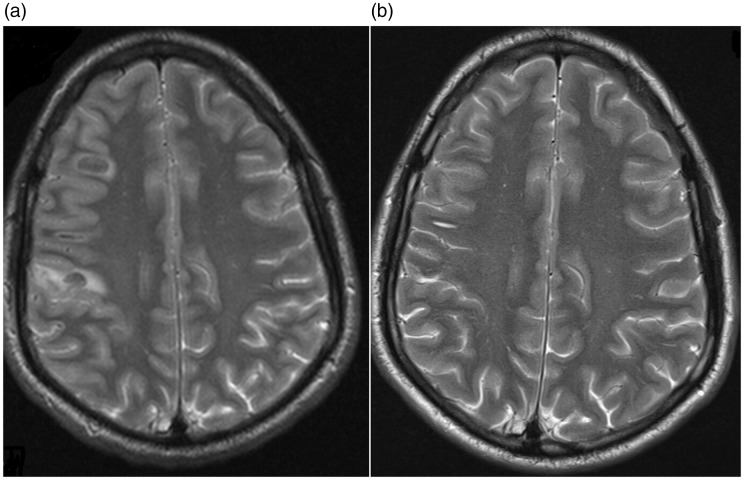

Good clinical outcome (modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 1) was observed at three-month follow-up. Despite slightly impaired fine motor skills of the left hand, our patient was able to resume his musical career. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging after six months showed normalization of the brain parenchyma (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging, axial views. Diffuse cortical swelling and intraparenchymal haemorrhage in right parietal lobe, January 2016 (a). Complete resorption of the haematoma and subarachnoid blood and normalization of gyral and sulcal pattern, June 2016 (b).

Discussion

This case report shows favourable clinical outcome after successful mechanical thrombectomy in a comatose patient with extensive CVT. In a recent study poor outcome (death or dependency) was observed in more than half of the patients with severe CVT treated in tertiary care hospitals. Midline shift, bilateral motor signs and clinical deterioration after admission were independent risk factors for poor outcome.7 In our opinion, subsequent endovascular treatment should be considered in this subgroup of CVT patients with overall poor prognosis despite optimal medical management. Current literature, mainly consisting of case reports and case series, shows promising results but does not allow firm conclusions about efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy in severe CVT.6,8 The available case reports indicate that the risk of harming a patient with mechanical thrombectomy is low, but the risk of publication bias should be taken into account. A systematic review showed similar outcome for endovascular treatment compared with standard treatment as reported by the ‘International Study on Cerebral Vein and dural sinus Thrombosis’ (unfavourable outcome defined as a mRS score of 3–6 in, respectively, 13% vs. 14% of the patients), despite a substantially higher percentage of comatose patients in the endovascular group (32% vs. 5%).9

In analogy to the shift from IA lytics to mechanical thrombectomy in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke, we expect a shift towards mechanical endovascular treatment of venous thrombosis. This is of particular interest because of the relatively high risk of intracranial haemorrhages witnessed in severe CVT.4 This risk led to recent reports describing mechanical treatment by aspiration only.10 In the case of aspiration being unsuccessful, subsequent thrombectomy via a stent-retriever could be an effective alternative endovascular treatment method, as demonstrated in this case report. The recent availability of larger sized stent-retrievers, more suited for the diameter of the dural sinuses, is expected to push this field further forward. However, wall imaging and pathology studies have demonstrated that stent retrievers could injure the arterial vessel wall when used for thrombectomy in arterial ischaemic stroke, and thrombectomy in CVT may damage the venous wall as well and thereby increase the complication risk. To further investigate the efficacy and safety of thrombectomy and thrombosuction in CVT, collaboration across institutes is needed. In conclusion, mechanical thrombectomy in CVT is a promising treatment that can be considered in patients who are at serious risk of incomplete recovery. Further investigation in a randomized trial is warranted.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Couthinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Aramideh M, et al. The incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis, a cross sectional study. Stroke 2012; 43: 3375–3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devasagaym S, Wyatt B, Leyden J, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis incidence is higher than previously thought: A retrospective population-based study. Stroke 2016; 47: 2180–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho JM, de Bruijn SF, de Veber G, et al. Anticoagulations for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2011; 8: CD002005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferro JM, Canhao P, Stam J, et al. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: Results of the international study on cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis. Stroke 2004; 35: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viegas LD, Stolz E, Canhao P, et al. Systemic thrombolysis for cerebral venous and dural sinus thrombosis: A systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 37: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stam J, Majoie CBLM, Delden van OM, et al. Endovascular treatment and thrombolysis for severe cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke 2008; 39: 1487–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kowoll CM, Kaminski J, Weiß V, et al. Severe cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis: Clinical course, imaging correlates, and prognosis. Neurocrit Care. Epub ahead of print 21 March 2016. DOI: 10.1007/s12028-016-0256-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Liao W, Liu Y, Gu W, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: Successful treatment of two patient using the penumbra system and review of endovascular approaches. Neuroradiol J 2015; 28: 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canhao P, Falcao F, Ferro JM. Thrombolytics for cerebral sinus thrombosis: A systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis 2003; 15: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bress A, Hurst R, Pukenas B, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis employing a novel combination of Angiojet and Penumbra ACE aspiration catheters: The Triaxial Angiojet Technique. J Clin Neurosci 2016; 31: 196–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]