Abstract

Background

Intracranial wide-neck aneurysms at the arterial bifurcations, especially in the aneurysms where the bifurcating branches emanate directly from the base of the aneurysm, have been particularly difficult on which to perform endovascular treatment. The ‘Y’-configuration, double stent-assisted coil embolization is an option for the treatment of these difficult aneurysms, allowing the closure of the aneurysm, preserving the parent arteries.

Material and methods

In a nine-year period, 546 intracranial aneurysms in 493 patients were treated at our center by endovascular approach. We have reviewed the medical records and arteriographies from November 2007 to January 2017 of 45 patients who were treated using ‘Y’-configuration double Neuroform® stent-assisted coil embolization.

Results

All patients were successfully treated.

The location of the aneurysms were: middle cerebral artery (MCA) 20 (44.4%), anterior communicating artery (AComA) 17 (37.7%), basilar four (8.9%), internal carotid artery (ICA) bifurcation three (6.6%) and posterior communicating artery (PComA) one (2.2%).

The mRS at hospital discharge was: mRS 0: 42 (93.3%), mRS 1: 1 (2.2%), mRS 2: 1 (2.2%) and mRS 5: 1 (2.2%).

The Modified Raymond-Roy Occlusion Classification, in the control at six months, was: Class I: 41 (91.1%), Class II: 2 (4.4%), Class IIIa: 1 (2.2%) and Class IIIb: 1 (2.2%).

Forty-four (97.8%) patients had a good outcome (mRS < 2) at six months. One (2.2%) patient had a poor outcome (mRS > 2) at six months that was due to sequelae of SAH.

There was no mortality at six months.

Conclusions

This technique is safe and effective for the endovascular treatment of difficult wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms, allowing the stable closure of the aneurysm, preserving the parent arteries.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, bifurcation aneurysm, intracranial stent, Neuroform, ‘Y’ stenting, ‘Y’-configuration stenting, coils

Introduction

The use of self-expanding neurovascular stents solely or in combination with endosaccular coiling has been reported to be feasible and effective in endovascular treatment of wide-neck or fusiform intracranial aneurysms.1–11

However, wide-neck aneurysms located at the arterial bifurcations, especially in aneurysms that have bifurcating branches emanating directly from the base of the aneurysm, have been particularly difficult to treat using coil embolization and may still not be amenable to being treated by using a single stent.

The introduction of intracranial flexible self-expanding stents has provided a great advantage to this dilemma by forming a bridge across the aneurysm neck and allowing the packing of coils. ‘Y’-configuration, double-stent-assisted coil embolization has been reported to be a safe and effective option for the endovascular treatment of these difficult bifurcation aneurysms, allowing the closure of the aneurysm and preserving the permeability of the afferent and efferent arteries.12–15

We present our experience with the endovascular treatment of intracranial complex wide-neck aneurysms in arterial bifurcations by embolization with coils, assisted by the double-stent technique with the ‘Y’-configuration, over a period of nine years.

Material and methods

In a nine-year period, 546 intracranial aneurysms in 493 patients were treated at our center by the endovascular approach. The authors retrospectively reviewed the medical records and angiographic data from November 2007 to January 2017 of 45 patients who were diagnosed as having cerebral aneurysms and subsequently treated using ‘Y’-configuration double Neuroform® stent-assisted coil embolization. Records of patients who were treated with a single-stent-assisted coil embolization (45) or with ‘X’-configuration double-stent-assisted coil embolization (two) or ‘Y’-configuration, double-stent (Neuroform® + LEO®)-assisted coil embolization (one) were discarded.

Patients were studied with cerebral angiography and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction, biplane flat-panel state-of-the-art angiographic systems having 3D and intraoperative angiographic XperCT scanners (Allura FD20/20; Philips, the Netherlands), which determine the anatomical and hemodynamic characteristics of the afferent and efferent arteries, the aneurysmal sac, the neck of the aneurysm and the relationship between them.

Aneurysm sizes were classified as small (<1 cm), large (1–2.5 cm), and giant (>2.5 cm).

This treatment was always performed electively. In the cases of ruptured aneurysms, they were treated with coils with the “balloon remodeling technique” in the acute phase, and those that could not be completely closed, or showed recanalization in the control angiography, were treated with this technique a second time, after the first month until six months after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Figure 1).

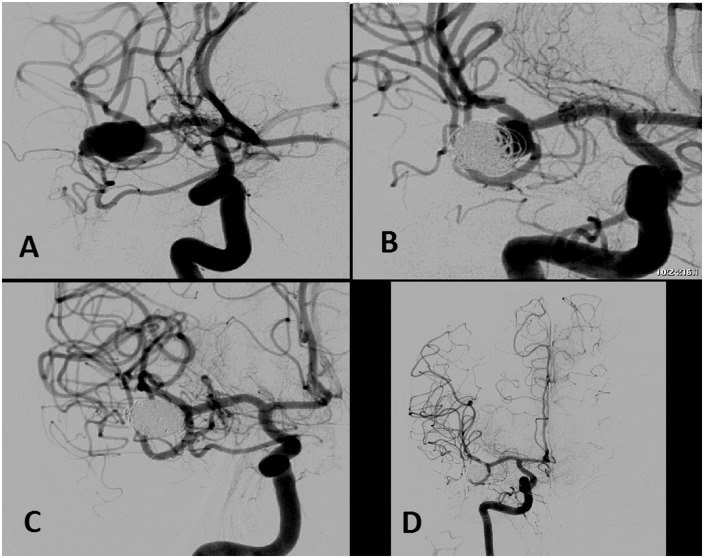

Figure 1.

Middle cerebral artery bifurcation wide-neck aneurysm diagnosed by subarachnoid hemorrhage (a). Initially, the aneurysm was embolized with coils with the balloon remodeling technique. The control angiography at six months showed an aneurysmal remnant (b). It was decided to treat the aneurysm with ‘Y’-configuration, double Neuroform® stent-assisted coil embolization. A complete packaging of the aneurysm was obtained with Microsphere® microcoils and Target® detachable coils, preserving the afferent and efferent arteries (c). One-year follow-up angiographic study showed complete closure of the aneurysm and remodeling of the arteries (d).

One week before embolization, patients were treated with aspirin 300 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day. We investigated the clopidogrel and aspirin response; all patients were submitted to aggregometry by using the Multiplate® analyzer (Roche Basilea, Switzerland). If no correct antiplatelet (usually clopidogrel) was detected (for the treatment with aspirin the aggregation of arachidonic acid <40 U was used. For treatment with P2Y2 receptor inhibitors, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) platelet aggregation was used, as follows: <19 U: low platelet reactivity, increased hemorrhagic risk; 19–46 U: optimal platelet reactivity; > 46 U: high platelet reactivity, increased thrombotic risk), the medication was switched to aspirin 300 mg/day and ticlopidine 250 mg/twice daily, or aspirin 100 mg/day and prasugrel 10 mg/day. The aggregometry study was repeated to confirm that these medications work correctly. Following the control angiogram obtained at six months, clopidogrel was discontinued and lifelong use of aspirin was prescribed.

Anticoagulation protocol during the procedure consisted of intravenous administration of heparin with close monitoring of blood activated clotting time (ACT) and Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) levels, and the ACT level was kept between 2 and 2.5 times that of the basal level. Heparin was discontinued after the procedure.

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia.

In all cases, a triaxial system was used, with an introducer 7F (Flexor Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA), guide catheter 6F (Navien (Covidien Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA)) or Envoy (Codman Neuro Division, Raynham, MA, USA) or Neuron (Penumbra Inc, Alameda, CA, USA)) introduced into the internal carotid artery (ICA) for anterior communicating artery (AComA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation aneurysms or ICA bifurcation, and into the vertebral artery (VA) for basilar bifurcation aneurysms (if VA is small, a 5F guide catheter was used).

Using 3D rotational angiography with reconstruction images and the working projections obtained from these, and under roadmap guidance, an Excelsior® XT-27 Flex microcatheter with a Synchro® 0.014-inch microwire (Boston Scientific for Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) was used. Two Neuroform® stents (Boston Scientific for Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) were deployed in the efferents and the afferent cerebral arteries, one passing through the interstices of the other in a ‘Y’-configuration, thereby recreating an aneurysm neck and enabling safe coil delivery while preserving the parent vessels. From 2009 to 2010 we used the third-generation Neuroform® stent, from 2010 until 2017 we used the Neuroform EZ® (fourth generation), and since May 2016 we have used the new Neuroform Atlas™ (fifth generation); we have used this device only in some patients with very tortuous arteries because it is more expensive than the Neuroform EZ®. It is important to note that when the Neuroform Atlas™ was used an Excelsior® SL-10® microcatheter (Boston Scientific for Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) was used instead of the Excelsior XT-27 Flex. We released the stents slowly and carefully, making pauses between the release of each circumferential ring of the stent, allowing each ring, and its struts, to open and position themselves properly and progressively adapt to the anatomy of the artery, trying to avoid strut overlapping or fish scaling.

The first Neuroform® stent was deployed on the more challenging bifurcating branch (i.e. the branch with a more acute angle relative to the main trunk); it was selected to be catheterized first by using a technique described previously.16 The microwire was then partially withdrawn to the level of the other branch origin, and, through the interstices of the stent, the other branch was catheterized with the same microcatheter and microwire. A second Neuroform® stent was then deployed with half of the stent in the other branch and the other half within the lumen of the previously placed stent. The microwire was then used to select the dome of the aneurysm, and with an Excelsior® SL-10® Microcatheter catheterized the aneurysm. The Excelsior® SL-10® microcatheter was subsequently used to deliver the following bare platinum coils, until a complete packaging of the aneurysm. We used Micrusphere® microcoils (Codman Neuro Division, Raynham, MA, USA) and Target® detachable coils (Boston Scientific for Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) (Figures 2 and 3).

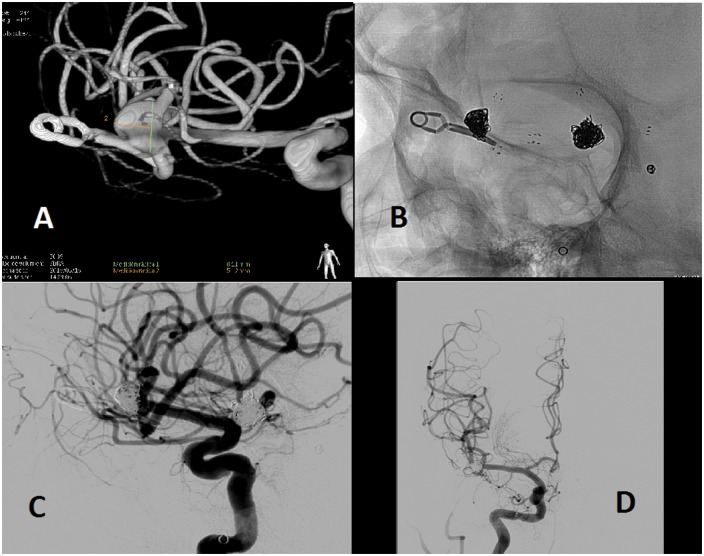

Figure 2.

Aneurysm of the middle cerebral artery that had been clipped in another hospital several years ago (1999), and in the angiographic study by a new subarachnoid hemorrhage, due to rupture of another aneurysm, a repermeabilization of this aneurysm was appreciated (a). It was decided to treat the aneurysm with ‘Y’-configuration, double Neuroform® stent-assisted coil embolization. A complete packaging of the aneurysm was obtained with Microsphere® microcoils and Target® detachable coils preserving the afferent and efferents arteries ((b), (c), (d)). In images (b) and (c), we appreciate the surgical clip and the Neuroform® stents in a configuration in ‘Y’, which keep the coils inside the aneurysmal sac, keeping the afferent and efferent arteries patent. It is important to mention that in (b), (c) and (d), other embolized aneurysms can be seen, one with only coils (left posterior communicating artery) and another with coils assisted with one stent (anterior communicating artery).

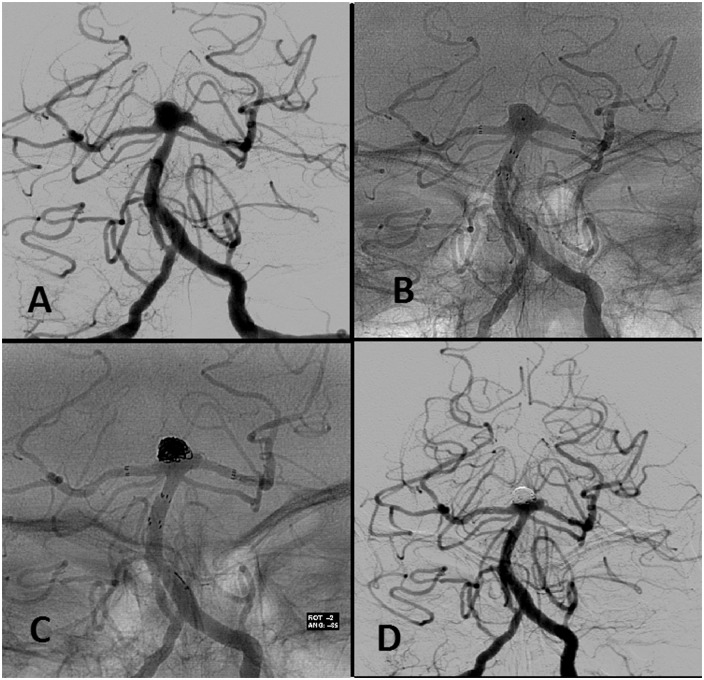

Figure 3.

Basilar tip bifurcation wide-neck aneurysm (a). The first Neuroform® stent was deployed. Through the interstices of the first stent, a second Neuroform® stent was then deployed with half of the stent in the left posterior cerebral artery and the other half within the lumen of the previously placed stent in a ‘Y’-configuration, thereby recreating an aneurysm neck and enabling safe coil delivery while preserving the parent vessels. With an Excelsior SL-10® microcatheter the aneurysm is catheterized through the interstices of the two stents (b). Microcatheter was subsequently used to deliver the following bare platinum coils (Microsphere® microcoils and Target® detachable coils), until a complete packaging of the aneurysm (c) was achieved. One-year follow-up angiographic study showing complete closure of the aneurysm (d).

The femoral access sites were closed with Perclose ProGlide®, 6F Suture-Mediated Closure (SMC) System (Abbott, IL, USA).

All patients underwent angiographic follow-up with controls at six months and a year to determine aneurysm closure, stents permeability, treatment stability and possible complications.

A Modified Raymond-Roy Occlusion Classification (RROC)17,18 was used for evaluating coiled aneurysms (Class I: complete obliteration; Class II: residual neck; Class III: residual aneurysm; Class IIIa designates contrast within the coil interstices and Class IIIb contrast along the aneurysm wall).

In case of recurrence, a re-embolization of the aneurysmal remnant with coils was performed.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 55.6 years. 28 (62.2%) were women and 17 (37.8%) were men.

Regarding the personal history of the patients: 23 (51.1%) had arterial hypertension (blood pressure >140/90); 12 (26.7%) had hypercholesterolemia; 14 (31.1%) were smokers; four (8.9%) had ischemic heart disease; three (6.7%) had diabetes mellitus (DM) and two (4.4%) had alcoholism (>40 g/day).

The symptomatology for which the aneurysm was diagnosed: aneurysm rupture with SAH nine (20.0%), headache eight (17.8%), incidental finding eight (17.8%), another neurological focal deficit eight (17.8%), repermeabilized six (13.3%), seizures two (4.4%), thrombosis and stroke two (4.4%), cranial nerve involvement one (2.2%) and rupture of another aneurysm one (2.2%).

The patient condition before procedure (previous modified Rankin Scale (mRS)) was: mRS 0: 42 (93.3%), mRS 1: 1 (2.2%), mRS 2: 1 (2.2%) and mRS 5: 1 (2.2%).

The antiplatelet treatment they received was: 34 (75.5%) aspirin + clopidogrel; six (13.3%) aspririn + prasugrel; five (11.1%) aspirin + ticlopidine.

Regarding antiplatelet resistance: six (13.3%) patients were resistant to clopidogrel, and one (2.2%) was resistant to clopidogrel and ticlopidine.

Twenty-five (56.6%) patients had only one aneurysm and 20 (44.4%) patients had multiple aneurysms, with a mean of 1.81 aneurysms.

The location of the aneurysms was: MCA 20 (44.4%), AComA 17 (37.7%), basilar 4 (8.9%), ICA bifurcation three (6.6%) and PComA one (2.2%).

Regarding the aneurysm size: 33 (73.3%) were small, 12 (26.6%) were large and none giant. The mean aneurysmal sac size was 11.9 mm (SD 3.3). The mean of the neck size was 4.64 mm (SD 2.9). The sac-to-neck ratio was 1.58.

According to the type of aneurysm: 44 (97.8%) were saccular and one (2.2%) was fusiform.

All patients were successfully treated by using this technique.

Only one (2.2%) patient had a complication during the procedure for acute stents thrombosis that was resolved by mechanical thrombectomy with the A Direct Aspiration First Pass Technique (ADAPT) performing aspiration with the ACE™ 64 microcatheter (Penumbra Inc, Alameda, CA, USA), and additionally with the intra-arterial administration of 10 mg abciximab (ReoPro®). It was a patient with an elective aneurysm on the top of the basilar artery that had not been prepared with double antiaggregation, because it was treated in a scheduled treatment using the balloon remodeling technique; at the end of the procedure a migration of a coil loop urgently forced placement of stents.

The mRS at hospital discharge or at day 7 was: mRS 0: 42 (93.3%), mRS 1: 1 (2.2%), mRS 2: 1 (2.2%), and mRS 5: 1 (2.2%).

Modified RROC in the control at six months was: Class I: 41 (91.1%), Class II: 2 (4.4%), Class IIIa: 1 (2.2%) and Class IIIb: 1 (2.2%).

Forty-four (97.8%) patients had a good outcome (mRS < 2) at six months.

Only one (2.2%) patient had a poor outcome (mRS > 2) at six months. It was a patient with a ruptured aneurysm that remained with neurological sequelae caused by the SAH with a gradation of 4 in the mRS at one-year follow-up (improved one point). This patient was treated with ‘Y’-configuration, double-stent-assisted coil embolization at one month of SAH.

There was no mortality at six months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the study.

| Mean age | 55.6 years old |

| Sex | 28 (62.2%) women |

| 17 (37.8%) men | |

| Symptomatology for which the aneurysm was diagnosed | 9 (20.0%) aneurysm rupture with SAH 8 (17.8%) headache |

| 8 (17.8%) incidental finding | |

| 8 (17.8%) neurological focal deficit | |

| 6 (13.3%) recurrent aneurysm | |

| 2 (4.4%) seizures | |

| 2 (4.4%) thrombosis and stroke | |

| 1 (2.2%) cranial nerve involvement | |

| 1 (2.2%) rupture of another aneurysm | |

| Number of aneurysms | 25 (56.6%) only one aneurysm |

| 20 (44.4%) multiple aneurysms | |

| Location of the aneurysms | 20 (44.4%) MCA |

| 17 (37.7%) AComA | |

| 4 (8.9%) basilar | |

| 3 (6.6%) ICA bifurcation | |

| 1 (2.2%) PComA | |

| Aneurysm size | 33 (73.3%) small |

| 12 (26.6%) large | |

| 0 giant | |

| Mean aneurysmal sac size | 11.9 mm |

| Mean of the neck size | 4.64 mm |

| Sac-to-neck ratio | 1.58 |

| The modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at hospital discharge or at day 7 | mRS 0: 42 (93.3%) |

| mRS 1: 1 (2.2%) | |

| mRS 2: 1 (2.2%) | |

| mRS 5: 1 (2.2%) | |

| Modified Raymond-Roy Occlusion Classification (RROC) in the control at six months | Class I: 41 (91.1%) |

| Class II: 2 (4.4%) | |

| Class IIIa: 1 (2.2%) | |

| Class IIIb: 1 (2.2%) | |

| Good outcome (mRS < 2) at six months | 44 (97.8%) |

| Poor outcome (mRS > 2) at six months | 1 (2.2%). Due to sequelae of SAH |

| Mortality at six months | None |

SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; MCA: middle cerebral artery; AComA: anterior communicating artery; ICA: interior carotid artery; PComA: posterior communicating artery.

Discussion

Large series have addressed the impact of neck size and complex anatomic features of aneurysms on two major drawbacks of endovascular coiling, defined as “incomplete initial occlusion rate” and “relatively less long-term durability.”19,20

The use of self-expanding neurovascular stents solely or in combination with endosaccular coiling has been reported to be feasible and effective in endovascular treatment of wide-neck or fusiform intracranial aneurysms.1–11 In addition to their role in supporting aneurysm packing, they produce flow redirection, disruption of intra-aneurysmal flow pattern, resulting in turbulence and production of blood stasis within the aneurysm, resulting in aneurysmal thrombosis, and stent-induced endothelialization, providing reconstruction of the diseased parent artery,21 achieving more durable long-term results.22

However, wide-neck aneurysms located at the arterial bifurcations, especially in the aneurysms where the bifurcating branches emanate directly from the base of the aneurysm, have been particularly difficult to treat using coil embolization and may still not be amenable to being treated by using a single stent.

The problem posed by a wide-necked bifurcation aneurysm is different from that of a wide-necked, sidewall aneurysm. Stent-assisted coiling of aneurysms involved deploying a stent into only one branch, with the proximal end in the parent artery thereby “jailing” the contralateral branch. This technique provides only partial protection from coil herniation into the parent vessel or into the other branch. Another hypothetical concern regarding this asymmetric stent deployment would be the alteration of flow favoring the artery in which the distal end of the stent was deployed. To solve the problem of partial protection, with the ‘Y’-configuration, double-stent-assisted coil embolization we were able to reconstruct the bifurcation by deploying a second stent through the interstices of the first stent.

In this fashion, all of the major parent vessels were favorably reconstructed and the entire aneurysm neck was protected from coil herniation. A technical caveat in achieving this configuration involves deploying the more challenging stent first. For instance, depending on the particular anatomy of each bifurcation, one of the arteries may originate at a more acute angle relative to the parent trunk and thus be more difficult to catheterize selectively. This artery should be stented first, if possible. Once a stent is deployed, it would have the effect of slightly straightening the angle of the artery relative to the parent artery. The interstices of the stent could make subsequent selection of the contralateral artery that much more difficult. In addition, we chose to deploy our second stent so that its proximal end coincided with the proximal end of the first stent. Theoretically, this would minimize disruption of laminar blood flow at the bifurcation. For instance, if the second stent was too short and was left abutting the sidewall of the first stent, turbulent flow could potentially lead to thrombus formation with the stent configuration.

In the literature the use of closed-cell stents has been published,16,21 but we believe that to make the configuration in ‘Y’ it is better to use two open-cell stents. The reasons are: Open-cell stents are better suited to tortuous anatomies; minor rectification of vessel anatomy; do not fold into closed curves; do not move because each struts acts as an anchor (which is very important when trying to catheterize the other branch and pass the microcatheter through the mesh of the first stent); with two closed cell stents it is advisable to use the “jailed” technique, while with open-cell stents this is not necessary; allow a correct expansion of the second stent when passing through the cell, contrary to what happens with the closed cell stents, in which the cell of the first stent through which the second stent passes, constricts the wall of the second stent, acting like a belt; however, some authors16 speculate that the closed-cell design of the stents may result in flow diversion at the intersection point, possibly due to the slight narrowing of the second stent while crossing.

On the other hand, the biggest problem with the use of open-cell stents is the impossibility of repositioning them, while the possibility of repositioning is the major advantage of the closed-cell stents.

Another potential advantage of redirecting the laminar blood flow pattern is that, theoretically, the incidence of coil compaction might be reduced. Many investigators believe that incompletely coiled bifurcation terminus aneurysms are particularly prone to re-canalization secondary to the hemodynamics of the parent artery and the resultant high-pressure pulsatile flow directly at the coil mass.23

Although the stents for intracranial use were originally designed for mechanical scaffolding purposes, recent laboratory and clinical reports on their hemodynamic effects by alteration of intra-aneurysmal flow velocity are attracting increasing interest.24 Only the placement of two stents in the ‘Y’-configuration without coiling, leads to important hemodynamic changes within the aneurysm. An experimental study designed to assess the changes in the hemodynamic forces acting on a bifurcating aneurysm model after stent placement with a ‘Y’-configuration showed that the effect of placing the Neuroform® stent across the neck of a bifurcating intracranial aneurysm was shown to reduce the magnitude of the velocity of the jet entering the sac by as much as 11%. Nevertheless, the effect of the stents was particularly noticeable at the end of the cardiac cycle, when the residual vorticity and shear stresses inside the sac were decreased by more than 40%.25 These findings have inspired some authors with the possibility of the use of stents, without endosaccular coil packing, as a viable therapy for some aneurysms; these authors published the ‘Y’ stent flow diversion technique for management of eight bifurcation aneurysms without endosaccular coiling, with good results.21

For this hemodynamic effect of the ‘Y’ stents, we add the aneurysmal sac packet with coils; it is expected that the complete aneurysm closure rate will increase and the frequency of recurrences will be reduced.

A very important aspect of this technique is to be very rigorous with the preparation and the study of aggregometry of the drugs used, having to take special care with the activity of clopidogrel. Resistance rates to clopidogrel may be as high as 39.7%26 or 51.2%27 and have been associated with the development of multiple diffusion-positive lesions.26 Hypercholesterolemia has been found to be an independent risk factor for clopidogrel resistance.27 Of the 273 patients of our hospital in whom we performed the aggregometry study, 50 (18.3%) had a low response to clopidogrel, three (1.09%) had a low response to aspirin and clopidogrel, four (1.46%) were allergic to clopidogrel, and one (0.36%) was allergic to aspirin. The non-responders and patients allergic to clopidogrel were switched to prasugrel or ticlopidine, and the aspirin-allergic patient received desensitizer treatment.

The only complication we had with this technique was directly related to the non-administration of double antiaggregation prior to stent placement.

The ‘Y’-configuration, double stent-assisted coil embolization was reported to be a safe and effective option for the endovascular treatment of these difficult bifurcation aneurysms, allowing the closure of the aneurysm and preserving the permeability of the afferent and efferent arteries.12–15

With our evolving experience, more meticulous technique, more rigorous preoperative antiaggregation preparation and assessment, the ‘Y’-configured, dual-stent placement has been part of our routine practice in complex bifurcation aneurysms. Our experience with long-term follow-up of 45 patients suggests very good and durable results.

An important aspect to keep in mind is that MCA bifurcation aneurysms, which have long been considered by many to be primarily surgical lesions, can be safely treated by endovascular means by using the ‘Y’-configuration, double-stent technique.12

The technological advancement that has allowed the development of the new Neuroform Atlas™ Stent (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA), the fifth generation of this stent featuring an innovative adaptive-cell architecture that is designed to optimize conformation and stability when treating wide-neck intracranial aneurysms, and that can deliver all sizes of the Neuroform Atlas™ Stent, from 3.0 mm up to 4.5 mm in diameter, through a low-profile 1.7-inch (0.56 mm) microcatheters such as the Excelsior SL-10® microcatheter, shows a promising future, as it will be able to treat much more complex aneurysms with more difficult vascular anatomy.

Conclusions

The ‘Y’-configuration, double Neuroform® stent-assisted coil embolization is a safe and effective technique for the endovascular treatment of difficult wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms, allowing the stable closure of the aneurysm and preserving the permeability of the afferent and efferent arteries.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work and cooperation of vascular neurologists, residents, anesthetists and neurointerventional nurses in the management of these patients.

All the co-authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. All co-authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author contributions are as follows: Carlos Castaño: Conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Treating patients. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Mikel Terceño: Substantial contributions to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Sebastián Remollo: Substantial contributions to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Ma Rosa García-Sort: Substantial contributions to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Carlos Domínguez: Substantial contributions to analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. Revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Fiorella D, Albuquerque FC, Deshmukh VR, et al. Usefulness of the Neuroform stent for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms: Results at initial (3–6 mo) follow-up. Neurosurgery 2005; 56: 1191–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lylyk P, Ferrario A, Pasbón B, et al. Buenos Aires experience with the Neuroform self-expanding stent for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubicz B, Leclerc X, Levivier M, et al. Retractable self-expandable stent for endovascular treatment of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: Preliminary experience. Neurosurgery 2006; 58: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pumar JM, Blanco M, Vázquez F, et al. Preliminary experience with Leo self-expanding stent for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 2573–2577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higashida RT, Halbach VV, Dowd CF, et al. Initial clinical experience with a new self-expanding nitinol stent for the treatment of intracranial cerebral aneurysms: The Cordis Enterprise stent. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 1751–1756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber W, Bendszus M, Kis B, et al. A new self-expanding nitinol stent (Enterprise) for the treatment of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: Initial clinical and angiographic results in 31 aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2007; 49: 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebig T, Henkes H, Reinartz J, et al. A novel self-expanding fully retrievable intracranial stent (SOLO): Experience in nine procedures of stent-assisted aneurysm coil occlusion. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yavuz K, Geyik S, Pamuk AG, et al. Immediate and midterm follow-up results of using an electrodetachable, fully retrievable SOLO stent system in the endovascular coil occlusion of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2007; 107: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yavuz K, Geyik S, Saatci I, et al. WingSpan stent system in the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: Clinical experience with midterm follow-up results. J Neurosurg 2008; 109: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zenteno MA, Santos-Franco JA, Freitas-Modenesi JM, et al. Use of the sole stenting technique for the management of aneurysms in the posterior circulation in a prospective series of 20 patients. J Neurosurg 2008; 108: 1104–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pumar JM, Lete I, Pardo MI, et al. LEO stent monotherapy for the endovascular reconstruction of fusiform aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1775–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow MM, Woo HH, Masaryk TJ, et al. A novel endovascular treatment of a wide-necked basilar apex aneurysm by using a Y-configuration, double-stent technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 509–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorell WE, Chow MM, Woo HH, et al. Y-configured dual intracranial stent-assisted coil embolization for the treatment of wide-necked basilar tip aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2005; 56: 1035–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sani S, Lopes DK. Treatment of a middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysm using a double Neuroform stent “Y” configuration and coil embolization: Technical case report. Neurosurgery 2005; 57(1 Suppl): E209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lozen A, Manjila S, Rhiew R, et al. Y-stent-assisted coil embolization for the management of unruptured cerebral aneurysms: Report of six cases. Acta Neurochir 2009; 151: 1663–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saatci I, Geyik S, Yavuz K, et al. X-configured stent-assisted coiling in the endovascular treatment of complex anterior communicating artery aneurysms: A novel reconstructive technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: E113–E117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy D, Milot G, Raymond J. Endovascular treatment of unruptured aneurysms. Stroke 2001; 32: 1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mascitelli JR, Moyle H, Oermann EK, et al. An update to the Raymond-Roy Occlusion Classification of intracranial aneurysms treated with coil embolization. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murayama Y, Nien YL, Duckwiler G, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms: 11 years’ experience. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond J, Guilbert F, Weill A, et al. Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils. Stroke 2003; 34: 1398–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cekirge HS, Yavuz K, Geyik S, et al. A novel “Y” stent flow diversion technique for the endovascular treatment of bifurcation aneurysms without endosaccular coiling. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1262–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fargen KM, Hoh BL, Welch BG, et al. Long-term results of enterprise stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2012; 71: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mericle RA, Wakhloo AK, Lopes DK, et al. Delayed aneurysm regrowth and recanalization after Guglielmi detachable coil treatment: Case report. J Neurosurg 1998; 89: 142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tateshima S, Tanishita K, Hakata Y, et al. Alteration of intraaneurysmal hemodynamics by placement of a self-expanding stent. J Neurosurg 2009; 111: 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canton G, Levy DI, Lasheras JC. Hemodynamic changes due to stent placement in bifurcating intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2005; 103: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim B, Kim K, Jeon P, et al. Thromboembolic complications in patients with clopidogrel resistance after coil embolization for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1786–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rho GJ, Shin WR, Kong TS, et al. Significance of clopidogrel resistance related to the stent-assisted angioplasty in patients with atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2011; 50: 40–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]