Abstract

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is considered the main etiological agent that causes acute hepatitis. It is estimated that 20 million cases occur annually worldwide, reaching mortality rates of 28% in pregnant women. To date, available treatments and vaccines have not been entirely effective. In this study, six antiviral peptides derived from the sequences of porcine Beta-Defensin-2 and bacteriocins Nisin and Subtilosin were generate using in silico tools in order to propose new antiviral agents. Through the use of molecular docking, interactions between the HEV capsid protein and the six new antiviral peptide candidates were evaluated. A peptide of 15 residues derived from Subtilosin showed the best docking energy (−7.0 kcal/mol) with the capsid protein. This is the first report to our knowledge involving a non-well study viral protein interacting with peptides susceptibles to being synthesized, and that could be subsequently evaluated in vitro; moreover, this study provide novel information on the nature of the dimerization pocket of the HEV capsid protein, and could help to understand the first steps in the viral replication cycle, needed for the virus entry to the host cell.

Keywords: Antiviral peptides, Hepatitis E virus, Bioinformatics tools

Introduction

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is considered the most common cause of acute hepatitis and jaundice, especially in developing countries, while in developed countries HEV infections are considered an emerging zoonosis [35]. HEV is a single stranded non-enveloped RNA virus of the Hepeviridae family and it is classified into four genotypes (genotype 1–4), and although it is known that can infect a wide range of vertebrate hosts, domestic pig is considered the main reservoir [18]; in Colombia, blood and feces from pig slaughterhouses were 100% IgG positives, and a 25% of pig livers sold in grocery stores were found positives for HEV [14, 15]. It is thought that consumption of virus contaminated water, animal products and manipulation of infected animals are the way that farm workers become the more susceptible population [3] reaching a 15.7% of anti-HEV antibodies in some regions of Colombia [16]. It is estimated that one-third of the world population is infected with the HEV and mortality rate is 1%, but the risk increases in pregnant women and immunocompromised patients, in which infection can reach up to 28 and 10%, respectively [11, 18].

In spite of the availability of a vaccine candidate for HEV, the safety of this vaccine is not fully understood, and it is not accessible worldwide; additionally, there is no specific treatment available [33], and treatments with Ribavirin and/or pegylated interferon, often administered to patients, have not been entirely effective (Price 2013), and these treatments are contraindicated in pregnant women and transplanted patients [11]. For these reasons, in its 2012 bulletin, the World Hepatitis Program of the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasized the need to maintain an active search for new therapeutic agents that would be easily accessible, and which could have greater efficacy and lower risk than current therapies, especially for patients at high risk.

In the search for new antiviral compounds, bioinformatic resources have become a powerful tool to optimize and to analyze interactions between target proteins and antiviral candidates [37], reducing time and costs involved in in vitro evaluation [7]. To date, databases that report, not only molecules with antiviral activity, but crystallized protein structures of great importance for viral replication (AVPdb database, PDB database) facilitates the search for therapeutic targets and leading antiviral compounds through molecular docking methods [10].

The HEV capsid protein is one of these targets, and it is also immunogenic. This protein is an essential dimer for interaction with the receptor in the host cell [42], facilitates the assembly of viral particles [1] and could be a good target to design and to evaluate antiviral molecules, because if an antiviral molecule blocks the capsid protein, infection could be inhibited. The HEV capsid protein monomer contains three domains, the Shell domain (amino acids 118–313), the Middle domain (amino acids 314–453) and the Protruding domain (amino acids 454–606) at the C-terminal end, which is considered the main antigenic domain [49]. In this region, amino acids 455–602 are well conserved among the four genotypes and it is the site of antibody binding [48]. The capsid protein gives the viral particle stability in both, alkaline and acidic environments, such as those of the gastrointestinal tract where the virus is exposed during its passage [50].

Antiviral peptides (AVPs), a special group of antimicrobial peptides, are considered as the main line of defense of innate immunity in many organisms [47]. Some of them, produced in most cases by the innate immune system and mainly in the gastrointestinal tract [41] like defensins [17], or produced as a bacterial metabolite mainly by lactic acid bacteria like bacteriocins [2], have demonstrated high activity against various groups of microorganisms, including important viral pathogens as Astrovirus [23] and Hepatitis B virus [26]. In a particular example, Subtilosin, a bacteriocin first obtained from Bacillus subtilis, inhibits in vitro replication of Herpes Simplex Virus [36, 44]. AVPs are indeed, a novel class of natural compounds, which have been proved to possess antiviral activity, thus becoming a new alternative for the design of new antiviral molecules [31].

Here we report six AVPs predicted from the sequence of bacteriocins and porcine Beta-Defensin-2, identified as antiviral candidates against HEV capsid protein through bioinformatic tools. Two virtual screening strategies for molecular docking were used, Autodock Vina and CABS-dock, in order to test the affinity between the six in silico predicted AVPs and the HEV capsid protein and to establish the best interactions between them and a potential antiviral agent derived from Subtilosin was selected. This is the first report involving Hepatitis E capsid protein and a new possible antiviral peptide, using computational methods.

Materials and methods

Search of target sequences

The structure of HEV capsid protein was selected based on its importance for virus entrance to the host cell [11] and was retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3RKC), taking into account that this structure have the highest resolution (1.79 Å) among all of the reported proteins of this virus. The structure was prepared with PMV-1.5.6 tools removing water molecules from the system, adding only polar hydrogens and computing Gasteiger charges for energy minimization. The minimized structure was saved as a PDBQT file for the docking experiments.

Antiviral peptide design and modeling

Six antiviral peptides were predicted based on the sequences of Nisin, Subtilosin and Porcine Beta-Defensin-2 reported in the DEFENSINS knowledgebase database (http://defensins.bii.a-star.edu.sg/). From these sequences, fragments of 12–15 residues in length were selected, overlapping each 5 residues, using the AVPpred tool of the Antiviral Peptides database [37]. The resulting AVPs candidates where then analyzed with the antiviral prediction tool of AVPdb and those with a probability higher than 50% of being antivirals were selected; additionally, physicochemical properties such as net charge and Grand Average of Hydropathy (GRAVY) were calculated using ProtParam from ExPASy portal [46] and absorption and toxicity profiles was investigated using admetSAR tool [8]. The 3D models of the selected peptides were obtained in the I-TASSER prediction server [39], and these structures were minimized adding charges with the default parameters in PMV-1.5.6 tools and saved as a PDBQT file format [45].

Molecular docking

Interactions studies of HEV capsid protein with the six potential AVPs predicted were carried out using AutoDock Vina [45] and CABS-Dock on line server [24]. For Autodock Vina analysis, the grid box was defined using the online tool PeptiMap [25], which predicts the “hot spots” or the best peptide-binding sites on the protein surface; all the docking assays were performed five times in a grid box with spacing of 1 Å and number of points in xyz = 24, the grid center was designated with the following dimensions, center x = −4.901, center y = −2.691 center z = 5.8, and with an exhaustiveness of 10. For CABS-Dock on line server, the binding pocket is restrained to only C-alpha atoms located within a 5–15 Å range from each other, allowing a first step with 10,000 models (10 trajectories by 1000 models) and filtering until the top 10 models. Binding affinity of the peptides to the surface of the HEV capsid protein was determined based on the affinity in terms of binding energy in Kcal/mol for five runs in Autodock Vina, and the RMSD value (root mean square deviation) in clustering tab for CABS-Dock. Analysis of all 3D structures generated, including the docking interactions were performed with the software Discovery Studio (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA).

Results

Antiviral peptide selection, physicochemical characteristics calculations and modeling of 3D structures

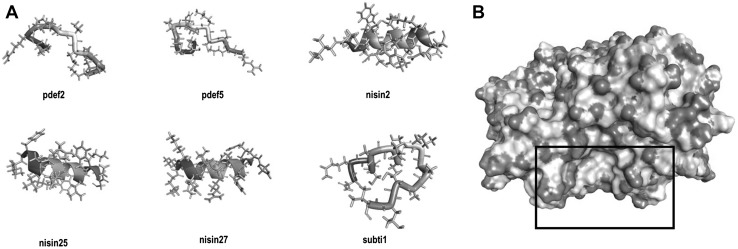

Bacteriocins, Nisin and Subtilosin were analyzed to find antiviral peptides using AVPpred tool; from the 41 fragments obtained from Nisin three, nisin2, nisin25 and nisin27, showed a probability higher than 50% of being antiviral. One of the three peptides obtained from Subtilosin (subti1) showed a 51.8% probability of being antiviral (Table 1). Using the sequence of Porcine Beta-Defensin-2, six possible antiviral peptides were generated with the AVPpred tool, but just two of the sequences, pdef2 and pdef5, showed a probability higher than 50% of being antiviral (Table 1). All of the predicted AVPs showed positive net charge and just subti1 showed tendency to be hydrophobic (GRAVY 1.05). Additionally, absorption parameters like aqueous solubility (logS values >−4.0) and Caco-2 permeability (>70%) were favorable for all AVPs selected. In silico toxicity profiles resulted in non-carcinogens, neither toxic at acute oral concentrations (category III includes compounds with LD50 values >500 mg/kg but <5000 mg/kg); on the other hand, pdef2, pdef5 and nisin27 showed a tendency to have a natural ability to biodegrade to their natural state (Table 1). 3D structures of nisin2, nisin25 and nisin27 showed a tendency to be alpha helix, and AVPs candidates, pdef2, pdef5 and subti1, tended to have a coiled conformation (Fig. 1a).

Table 1.

Physicochemical characteristics of predicted AVPs derived from porcine Beta-Defensin-2 and bacteriocins

| Antiviral peptide | Sequence | Length | Probability (%)a | Net chargeb | GRAVYc | Carcinogenesis | Acute oral toxicityd | Aqueous solubilitye | Biodegradation | Caco-2 permeability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pdef2 | CLRNKGVCMPGK | 12 | 50.1 | 3 | −0.28 | Non-carcinogens | III | −2.64 | Ready biodegradable | 70.9 |

| pdef5 | TCGMPQVKCCKR | 12 | 50.7 | 3 | −0.41 | Non-carcinogens | III | −2.42 | Ready biodegradable | 71.3 |

| nisin2 | IIAQWDERTRKNKEN | 15 | 50.0 | 1 | −1.91 | Non-carcinogens | III | −3.00 | Not ready biodegradable | 77.1 |

| nisin25 | KFELERKKQFLWKDG | 15 | 66.2 | 2 | −1.48 | Non-carcinogens | III | −3.64 | Not ready biodegradable | 78.7 |

| nisin27 | LKKEKVIREASFIRD | 15 | 68.1 | 2 | −0.69 | Non-carcinogens | III | −3.10 | Ready biodegradable | 70.3 |

| subti1 | NKGCATCSIGAACLV | 15 | 51.8 | 1 | 1.05 | Non-carcinogens | III | −3.78 | Not ready biodegradable | 71.1 |

a Probability based on AVPpred tool of antiviral peptide database. We considered either composition or physicochemical parameter higher than 50% as a good candidate

b Calculate using ExPASy http://web.expasy.org/protparam/

c Grand average of hydropathy, based on Kyte–Doolittle hydropathy plots, scores closer to −2 means hydrophilic molecule, meanwhile scores closer to +2 means hydrophobic molecule

d Category III includes compounds with LD50 values >500 mg/kg but <5000 mg/kg

e Calculate based on LogS value

Fig. 1.

Predicted antiviral peptides 3D structures and HEV capsid protein surface map. Antiviral peptides derived from Porcine beta-defensin-2 (pdef2 and pdef5), Nisin (nisin2, nisin25 and nisin27) and Subtilosin (subti1) were modeled using I-TASSER server; N-ter domain is shown in blue and C-ter domain in red (a). HEV capsid protein binding site (black square) is mainly a neutral region (white areas) surrounded mainly by positive regions (blue areas) and a few negative regions (red areas) (b). All images were prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio (colour figure online)

A bacteriocin derived peptide strongly interacts with Hepatitis E capsid protein

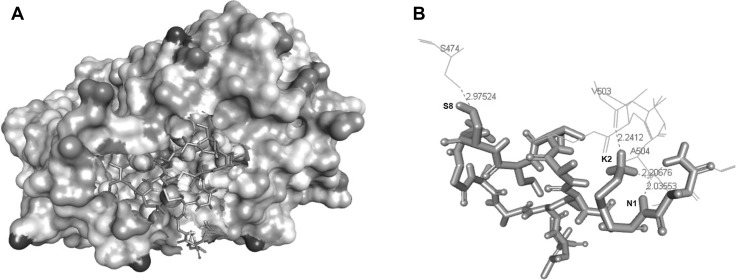

We examined the binding affinity of the six predicted peptides with Hepatitis E capsid protein using Autodock Vina and CABS-Dock web server. Five of the evaluated AVPs, pdef2, pdef5, nisin2, nisin25 and nisin27, showed binding energy values with the capsid protein above the threshold defined by Chang et al. of −7.0 kcal/mol [6], but the predicted AVP subti1, a 15 amino acid peptide derived from Subtilosin displayed a good docking score of −7.0 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (Table 2). The interaction of subti1 with the capsid protein was mediated by four hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) between K2-V503, K2-A504, N1-A504 in chain A, and S8-S474 in chain B of the target protein (Fig. 2; Table 2). Distances between atoms of subti1 and atoms of the target protein were <3.0 Å in all contacts (Fig. 2b), and the closer one, between K2 of subti1 and A504 of chain A of the HEV capsid protein, had a distance of 2.0 Å.

Table 2.

Docking scores obtained with AutoDock Vina of antiviral peptide candidates derived from porcine Beta-Defensin-2 and bacteriocins with HEV capsid protein

| Antiviral peptide | AutoDock Vina binding energy (Kcal/mol)* | Number of H-bonds | H-bonds lower average distance (Å) | Chain A residues forming H-bonds with APVs | Chain B residues forming H-bonds with APVs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pdef2 | −5.6 ± 01 | 9 | 2.9 | R460-P10, A467-K12, N468-K12 | S474-L2, S474-K5, T476-R3, T476-N4, T499-N4, S596-L2 |

| pdef5 | −4.7 ± 01 | 8 | 2.9 | R460-V7, N468-M4, D469-K8 | W472-T1, S474-T1, S474-C2, Q508-R12, S596-G3 |

| nisin2 | −4.3 ± 04 | 10 | 2.8 | R460-K13, R466-N12, N468-Q4, N468-N15, | G506-R10, G510-R10, Q508-I1, W548-Q4, G551-Q4, S596-Q4, |

| nisin25 | −4.6 ± 01 | 11 | 2.8 | R466-F10, R466-K13, A467-W12, N468-G15, R542-G15, A504-F10 | S474-K1, V503-R6, V503-F2, A504-R6, G506-R6, Q508-F2 |

| nisin27 | −4.5 ± 02 | 11 | 2.6 | R460-E4, N468-V6, N468-E9, D469-K5, T505-K2 | V503-K3, A504-K3, S474-E9, Q508-F12, Q508-D15, S596-E9, |

| subti1 | −7.0 ± 01 | 4 | 2.4 | V503-K2, A504-K2, A504-N1 | S474-S8 |

*Docking scores were calculated over 5 runs. Errors represent the standard error of the mean

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the interactions between the antiviral peptide subti1 with HEV capsid protein. Target protein surface with ligand Subti1 in the interaction defined pocket (a). Residues in the target protein are shown as lines, while residues in AVP are shown in solid tubes. All hydrogen bonds and their distances have been labeled. The greater distance was 2.9 Å and the lower one 2.0 Å. Interactions are denoted by red dotted lines. One letter code amino acids of subti1 and target protein are shown in black and red, respectively (b). Images were prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio (colour figure online)

Flexible docking shows high accuracy between the interaction of predicted AVPs and Hepatitis E capsid protein

In order to validate the interactions of the predicted AVPs and the target protein by other methods, we used the CABS-Dock online server. The results using CABS-Dock indicate cluster interactions for all AVPs at distances <4.5 Å (Table 3). However, the best docking interaction of nisin2 was found in the target protein close to the binding pocket defined for AutoDock Vina experiments (Table 3; RMSD 4.5 Å). The interactions of the remaining AVPs that occurred near the binding pocket defined for AutoDock Vina analysis showed low quality accuracy prediction with RMSDs >5.5 Å (Table 3).

Table 3.

CABS-Dock Cluster analysis of antiviral peptide candidates derived from porcine Beta-Defensin-2 and bacteriocins with HEV capsid protein

| Antiviral peptide | Best CABS-dock cluster average RMSD (Å) | CABS-dock cluster average RMSD (Å) near to the Autodock Vina defined binding pocket |

|---|---|---|

| pdef2 | 2.84 | 11.97 |

| pdef5 | 0.48 | 9.67 |

| nisin2 | 4.50 | 4.50 |

| nisin25 | 2.22 | 6.21 |

| nisin27 | 3.52 | 9.40 |

| subti1 | 1.31 | 6.14 |

Discussion

The design of new antiviral molecules is a worldwide priority, mainly for those viral diseases which have neither, specific vaccine nor treatment available. Acute hepatitis caused by Hepatitis E virus is one of them, because for pregnant women and immunocompromised patients, considered the major risk population, current therapies using ribavirin or interferon are not a solution for them, as reported by WHO in 2014; therefore, new antiviral strategies should be developed. To achieve this goal, computational methods could help improving the search for antiviral molecules.

Computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) methods could be based on both protein structure or ligand activity [9] and they are being used in new drug design, reducing the cost and time associated with conventional methods in which hundreds of candidate compounds are experimentally tested in cell culture systems [7]. Using CADD methods, six new antiviral candidates based on antimicrobial peptides were predicted using reported sequences of Porcine Beta-Defesin-2 and the bacteriocins, Nisin and Subtilosin. These antiviral candidates displayed low toxicity based on ADMET parameters and high probability of being antivirals according to AVPpred (Table 1). However, there is not a consensus about the best prediction method for in silico drug discovery, and it is also known that the use of one method does not guarantee success in later steps of in vitro drug discovery [9]. Therefore, the combination of AutoDock Vina and CABS-Dock prediction methods used in this study, showed similar high-scoring hits for target-ligand interactions, enhancing the accuracy of our results. We demonstrate for the first time, a reliable interaction between subti1, a possible antiviral peptide derived from Subtilosin, with Hepatitis E capsid protein.

Based on the electrostatic potential analysis of the predicted binding site of HEV capsid protein, the reactive site is mainly neutral, surrounded by positive regions due to the presence of R460 and R466 residues in chain B (Fig. 1b). Additionally, the possible reactive site is a well-defined pocket [27], which is considered a favorable region for an extensive contact between the HEV capsid protein and ligands [38], and has a core dominated by the hydrophobic residues W472, V501, V503 in chain A, and A467 and V470 in chain B, considered binding “hot spots” in protein–peptide interactions [27].

Due to the emergence of viral resistant phenotypes to conventional antiviral agents and the loss of effectiveness of current inhibitors [43], other viral proteins like proteases, helicase and capsid proteins have become antiviral targets. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a widely studied viral model, and using CADD methods a natural bicycle diterpene was evaluated by molecular docking. This diterpene interacts with both, the native and the mutated structures of the HCV NS3-4A protease, with a docking score of −15.1 kcal/mol, and this interaction was mediated mainly by the presence of hydrogen bonds between the ligand and S, A and H amino acids in the target protein [5]; in our study, the best interaction between subti1 and HEV capsid protein showed a docking score of −7.0 kcal/mol and was also mediated by the presence of A504 in chain A of the HEV capsid protein, forming two hydrogen bonds (Table 2). In a similar way, bioflavonoids showed a promissory anti-HCV helicase activity, with high docking scores and with residues D and S as the main amino acids participating in the interaction [13]; these residues were also mediating the interaction of HEV capsid protein and the AVPs designed in our study, suggesting that D and S could be crucial for AVPs interactions (Table 2). For HCV capsid protein a strongly interaction between natural-derived bioflavonoid has also been demonstrated; in this case, high docking scores according to Molegro Virtual Docker software were probably due to ten H-bonds involving three R residues [29], and in the same way, all the interactions between the six AVPs reported in this study involved R460 in both chains (Table 2).

The potential of antiviral peptides had been proved in vitro, for example, HCV core-derived peptides significantly reduced the number of infected cells with an EC50 of 3.2 µM [22]. In nonenveloped virus such as Enterovirus, the search for new antiviral molecules also remains as a priority, and a novel pocket-binding inhibitor was found during the course of computational and in vitro studies with a promising IC50 of 25 µM [21]. In spite that target proteins for enveloped virus are usually located in the envelope, new molecules had been evaluated against Dengue Virus (DENV) capsid protein. A small organic molecule inhibitor (ST-148) exhibited an in vitro antiviral activity against DENV with an IC50 of 10 µM, and molecular docking revealed that this inhibition was probably due to the interaction between the inhibitor and amino acid S34 of the DENV capsid protein [40]. Although docking scores of predicted APVs derived from Porcine Beta-Defensin-2 and Nisin did not reach the −7.0 kcal/mol threshold, all the interactions observed were mediated by S (Table 2); this finding could turn into a relevant fact, because it has been demonstrated, that some anti HIV antivirals with lower binding energies as −2.88 kcal/mol, exhibited high antiviral activity in vitro [10].

In other viral models, synthetic peptides with coiled conformation designed to interact with Hepatitis B core antigen, inhibited a crucial step in Hepatitis B virus morphogenesis, blocking binding of the envelope surface antigen to the core antigen with an IC50 of 30 µM [30], and similar to our results, where the best docking interaction occurred between subti1, a coiled peptide, and the target protein and where the interaction were also mediated mainly by S and R residues. Likewise, antiviral peptides designed using as models the N-term and C-term sequences of Influenza A Virus hemagglutinin displayed in vitro antiviral activity against different strains of Influenza A virus and the interaction between the designed peptides and the viral hemagglutinin was demonstrated by molecular docking strategies [28]. Other studies, also revealed that proline-rich peptides derived from venom toxins and insect antimicrobial peptides inhibit Influenza A virus replicon in more than 40%; and in vivo, those peptides protected mice from excessive body weight loss, a common clinical sign of the disease [20]. Jain and Piramanayagam, demonstrated that peptides derived from the sequence of commercial monoclonal antibodies, displayed high binding affinity (Zdock score > 900) with Human Respiratory syncytial virus surface glycoprotein [19]. Using an opposite approximation, a cell receptor as target, positively charged and alpha helical designed peptides, according the basic model KAQKAQA, reduced the infection of human cytomegalovirus in more than 90%, probably blocking viral absorption [12].

In this study, the interaction between HEV capsid protein and subti1 antiviral peptide candidate was mediated by four hydrogen bonds, one of them established with S474 in chain B of the target protein with a distance average between atoms of 2.4 Å, being the lowest compared to the other interactions (Table 2; Fig. 2b). Currently, commercial antivirals against Influenza virus such as Oseltamivir had been evaluated in silico in order to understand their inhibitory potential, and it has been shown that distances found experimentally for hydrogen bonds between the target protein and the ligand were between 2.71 and 2.81 Å, and the results of in silico studies indicate that these distances were between 2.79 and 2.90 Å [4], confirming the potential of in silico studies as a new antiviral prediction strategy. Subti1 also revealed a lower cluster average RMSD of 1.3 Å (Table 3), indicating a high accuracy prediction for protein–peptide interaction [24]. RMSD values around 1.2 Å could be considered as a favorable distance for pharmacophore interactions [34]. Protein–protein interactions mediated by hydrogen bonds could imply higher affinities, and could make the complex stable for longer [32], which indeed means, that the antiviral peptide subti1 could inhibit attachment of the HEV capsid protein to its cell receptor, indicating that this antiviral peptide, found by molecular docking, could be a promising candidate for in vitro assays.

In conclusion, bioinformatics tools have been widely used to discover new drugs, and are considered a powerful strategy for the pharmaceutical industry [31]. The docking strategy used in this study helped to identify a potential antiviral peptide with high affinity for HEV capsid protein; and revealed new data of possible binding pockets for drug design using the HEV capsid protein as a model. Further research will be conducted to evaluate the interaction between the HEV capsid protein and candidate peptides in vitro, to confirm their possible antiviral activity.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Project No. 25627; Ph.D. Scolarship from Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación COLCIENCIAS, Project No. 567-2012.

References

- 1.Ahmad I, Holla RP, Jameel S. Molecular virology of Hepatitis E virus. Virus Res. 2011;161:47–58. (cited 16 Sept 2014). http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168170211000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Al Kassaa I, Hober D, Hamze M, Chihib NE, Drider D. Antiviral potential of lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2014 (cited 30 Sept 2014); http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24880436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Andraud M, Dumarest M, Cariolet R, Aylaj B, Barnaud E, Eono F, et al. Direct contact and environmental contaminations are responsible for HEV transmission in pigs. Vet Res. 2013;44:102. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aruksakunwong O, Malaisree M, Decha P, Sompornpisut P, Parasuk V, Pianwanit S, et al. On the lower susceptibility of oseltamivir to influenza neuraminidase subtype N1 than those in N2 and N9. Biophys J. 2007;92:798–807. (cited 11 May 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1779986&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Chandramohan V, Kaphle A, Chekuri M, Gangarudraiah S, Bychapur Siddaiah G. Evaluating andrographolide as a potent inhibitor of NS3-4A protease and its drug-resistant mutants using in silico approaches. Adv Virol. 2015;2015:972067. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4637434&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chang MW, Lindstrom W, Olson AJ, Belew RK. Analysis of HIV wild-type and mutant structures via in silico docking against diverse ligand libraries. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1258–62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17447753. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen Q, Luo H, Zhang C, Chen Y-PP. Bioinformatics in protein kinases regulatory network and drug discovery. Math Biosci. 2015;262:147–56. (cited 22 July 2015). http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025556415000292. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cheng F, Li W, Zhou Y, Shen J, Wu Z, Liu G, et al. admetSAR: a comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J Chem Inf Model. American Chemical Society; 2012;52:3099–105. (cited 18 Dec 2015). doi: 10.1021/ci300367a. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Chiba S, Ikeda K, Ishida T, Gromiha MM, Taguchi Y-H, Iwadate M, et al. Identification of potential inhibitors based on compound proposal contest: tyrosine-protein kinase Yes as a target. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17209. (cited 16 Feb 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4660442&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cosconati S, Forli S, Perryman AL, Harris R, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. Virtual screening with AutoDock: theory and practice. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2010;5:597–607. (cited 23 Sept 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3083070&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Debing Y, Neyts J. Antiviral strategies for Hepatitis E virus. Antiviral Res. Elsevier B.V.; 2014;102:106–18. (cited 11 Sept 2014). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24374149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dogra P, Martin EB, Williams A, Richardson RL, Foster JS, Hackenback N, et al. Novel heparan sulfate-binding peptides for blocking herpesvirus entry. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126239. (cited 9 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4436313&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Fatima K, Mathew S, Suhail M, Ali A, Damanhouri G, Azhar E, et al. Docking studies of Pakistani HCV NS3 helicase: a possible antiviral drug target. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106339. (cited 7 Apr 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4154687&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Forero J, Gutiérrez C, Parra J, Correa G, Rodríguez B, Gutiérrez L, et al. Serological evidence of Hepatitis E virus infection in Antioquia, Colombia slaughtered pigs. MVZ Córdoba. 2015;20:4602–4613. doi: 10.21897/rmvz.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutiérrez C, Quintero J, Duarte JF. Detection of Hepatitis E virus genome in pig livers in Antioquia. Colombia. 2015;14:2890–2899. doi: 10.4238/2015.March.31.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutiérrez C, Rodríguez B, Suescún JP, Londoño GC, López LL, Herrera AL, et al. Determinación de anticuerpos totales (IgG/IgM) e IgM específicos para el virus de la Hepatitis E y detección molecular del virus en humanos con y sin exposición ocupacional a porcinos en 10 municipios de Antioquia. Iatreia. 2015;28:218–225. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwyer Findlay E, Currie SM, Davidson DJ. Cationic host defence peptides: potential as antiviral therapeutics. BioDrugs. 2013;27:479–93. (cited 10 Nov 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3775153&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Meng XJ. Hepatitis E virus: animal reservoirs and zoonotic risk. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:256–65. (cited 25 Aug 2014). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2814965&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jain R, Piramanayagam S. In silico approach towards designing virtual oligopeptides for HRSV. Sci World J. 2014;2014:613293. (cited 9 Mar 2016)http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4265542&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jiang H, Xu Y, Li L, Weng L, Wang Q, Zhang S, et al. Inhibition of influenza virus replication by constrained peptides targeting nucleoprotein. Antivir Chem Chemother. SAGE Publications; 2011;22:119–30. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://avc.sagepub.com/content/22/3/119.full. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kelly JT, De Colibus L, Elliott L, Fry EE, Stuart DI, Rowlands DJ, et al. Potent antiviral agents fail to elicit genetically-stable resistance mutations in either enterovirus 71 or Coxsackievirus A16. Antiviral Res. 2015;124:77–82. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4678291&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kota S, Takahashi V, Ni F, Snyder JK, Strosberg AD. Direct binding of a Hepatitis C virus inhibitor to the viral capsid protein. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32207. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3289641&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kreuzer S, Machnowska P, Aßmus J, Sieber M, Pieper R, Schmidt MFG, et al. Feeding of the probiotic bacterium Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 differentially affects shedding of enteric viruses in pigs. Vet Res. 2012;43:58. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-43-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurcinski M, Jamroz M, Blaszczyk M, Kolinski A, Kmiecik S. CABS-dock web server for the flexible docking of peptides to proteins without prior knowledge of the binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W419-24. (cited 6 Dec 2015). http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/43/W1/W419.full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Lavi A, Ngan CH, Movshovitz-Attias D, Bohnuud T, Yueh C, Beglov D, et al. Detection of peptide-binding sites on protein surfaces: the first step toward the modeling and targeting of peptide-mediated interactions. Proteins. 2013;81:2096–105. (cited 19 Jan 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4183195&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Lee DK, Kang JY, Shin HS, Park IH, Ha NJ. Antiviral activity of Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212 against Hepatitis B virus. Arch Pharm Res. 2013;36:1525–32. (cited 9 Oct 2014). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23657805. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.London N, Movshovitz-Attias D, Schueler-Furman O. The structural basis of peptide–protein binding strategies. Structure. 2010;18:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Martínez R, Ramírez-Salinas GL, Correa-Basurto J, Barrón BL. Inhibition of influenza A virus infection in vitro by peptides designed in silico. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76876. (cited 9 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3795628&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Mathew S, Faheem M, Archunan G, Ilyas M, Begum N, Jahangir S, et al. In silico studies of medicinal compounds against Hepatitis C capsid protein from north India. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2014;8:159–68. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4076477&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Muhamad A, Ho KL, Abdul Rahman MB, Tejo BA, Uhrin D, Tan WS. Hepatitis B virus peptide inhibitors: solution structures and interactions with the viral capsid. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:7780–7789. doi: 10.1039/C5OB00449G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulder KCL, Lima LA, Miranda VJ, Dias SC, Franco OL. Current scenario of peptide-based drugs: the key roles of cationic antitumor and antiviral peptides. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagasundaram N, Zhu H, Liu J, V K, C GP, Chakraborty C, Chen L. Analysing the effect of mutation on protein function and discovering potential inhibitors of CDK4: molecular modelling and dynamics studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133969. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pérez-Gracia MT, Suay B, Mateos-Lindemann ML. Hepatitis E: an emerging disease. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;22:40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poongavanam V, Kongsted J. Virtual screening models for prediction of HIV-1 RT associated RNase H inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73478. (cited 19 May 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3774690&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Price J. An update on Hepatitis B, D, and E viruses. Top Antivir Med. 2013;21:157–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quintana VM, Torres NI, Wachsman MB, Sinko PJ, Castilla V, Chikindas M. Antiherpes simplex virus type 2 activity of the antimicrobial peptide subtilosin. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;117:1253–9. (cited 9 Nov 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4198449&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Qureshi A, Thakur N, Tandon H, Kumar M. AVPdb: a database of experimentally validated antiviral peptides targeting medically important viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D1147–53. (cited 10 Oct 2014). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3964995&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Rigden D. From protein structure to function with bioinformatics. Springer Science & Business Media; 2009 (cited 3 Mar 2016). https://books.google.com/books?id=U94YCBvGe7MC&pgis=1.

- 39.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–38. (cited 15 July 2014). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2849174&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Scaturro P, Trist IML, Paul D, Kumar A, Acosta EG, Byrd CM, et al. Characterization of the mode of action of a potent dengue virus capsid inhibitor. J Virol. 2014;88:11540–55. (cited 3 Feb 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4178822&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Sekirov I, Russell S, Antunes L. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:859–904. http://physrev.physiology.org/content/90/3/859.short. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Tang X, Yang C, Gu Y, Song C, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Structural basis for the neutralization and genotype specificity of Hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10266–71. (cited 1 Oct 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3121834&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Tijsma A, Franco D, Tucker S, Hilgenfeld R, Froeyen M, Leyssen P, et al. The capsid binder Vapendavir and the novel protease inhibitor SG85 inhibit enterovirus 71 replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6990–2. (cited 17 Mar 2016). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4249361&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Torres NI, Noll KS, Xu S, Li J, Huang Q, Sinko PJ, et al. Safety, formulation, and in vitro antiviral activity of the antimicrobial peptide subtilosin against herpes simplex virus type 1. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2013;5:26–35. (cited 9 Nov 2015). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3637976&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–61. (cited 11 Jul 2014). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3041641&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Walker JM. The proteomics protocols handbook. Totowa: Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang G, Li X, Wang Z. APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D1087-93. (cited 27 Nov 2015)http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4702905&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Xing L, Wang JC, Li T-C, Yasutomi Y, Lara J, Khudyakov Y, et al. Spatial configuration of Hepatitis E virus antigenic domain. J Virol. 2011;85:1117–24. (cited 16 Sept 2014). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3020005&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Xu M, Behloul N, Wen J, Zhang J, Meng J. Role of asparagine at position 562 in dimerization and immunogenicity of the Hepatitis E virus capsid protein. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;37:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zafrullah M, Khursheed Z, Yadav S, Sahgal D, Jameel S, Ahmad F. Acidic pH enhances structure and structural stability of the capsid protein of Hepatitis E virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:67–73. (cited 16 Sept 2014). http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006291X03024604. [DOI] [PubMed]