Abstract

MicroRNAs are small, noncoding RNAs that posttranscriptionally regulate gene expression. The discovery of this relatively new mode of gene regulation as well as studies showing the prognostic value of viral and cellular miRNAs as biomarkers, such as in cancer progression, has stimulated the development of many methods to characterize miRNAs. EBV encodes 25 viral precursor microRNAs within its genome that are expressed during lytic and latent infection. In addition to viral miRNAs, EBV infection induces the expression of specific cellular oncogenic miRNAs, such as miR-155, miR-146a, miR-21, and others, that can contribute to the persistence of latently infected cells. This chapter describes several current techniques used to identify and detect the expression of viral and cellular miRNAs in EBV-infected cells.

Keywords: BHRF1, BART, MicroRNA, RISC, RNA isolation, Deep sequencing, RIP-seq, Primer extension, Stem-loop qRT-PCR, Luciferase assay

1 Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important regulators of many, if not most, biological processes, including homeostasis, cell growth and differentiation, and responses to stimuli such as viral infection. These ~22 nt small, noncoding RNAs posttranscriptionally regulate gene expression by guiding the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to sequence-specific sites on target mRNAs, thereby repressing translation and/or inducing mRNA degradation. Virus infection can trigger dramatic changes in the host miRNA repertoire which consequently alters the host transcriptional and translational environment [1–7]. In B cells, for example, EBV induces high levels of oncogenic miR-155 which is required for the growth of these cells [1, 3, 8], while in EBV-positive epithelial cells, many tumor suppressor miRNAs are downregulated [4]. Notably, miRNA signatures have been linked to EBV status in B-cell lymphomas [6, 9, 10]. Given the many studies associating miRNA expression patterns with disease states [5–6, 9–12], miRNAs have significant value as biomarkers. Techniques such as miRNA profiling by deep sequencing and stem-loop qRT-PCR, described here, have been applied to a variety of cell types and tumors to investigate cellular and viral miRNAs during lytic and latent EBV infection.

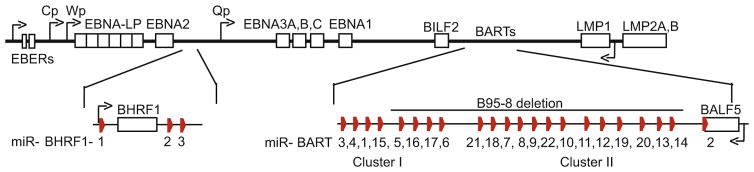

Viral miRNAs were first identified in 2004 in EBV-infected cells [13]; initially, the expression of five EBV miRNAs (miR-BHRF1-1,miR-BHRF1-2,miR-BHRF1-3, miR-BART1, and miR-BART2) was demonstrated by cloning of small RNAs (18–24 nt) from EBV B95-8-infected BL41 cells and confirmed by Northern blot analysis. Over the last 10 years, additional EBV miRNAs have been identified by sequencing studies [15–17], and there is now evidence for >300 viral miRNAs expressed by herpesviruses and other DNA and RNA tumor virus families (reviewed in [5] and mirbase.org). At least 44 mature miRNAs arise from the 25 EBV precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs): three miRNAs flank the BHRF1 ORF encoding a viral Bcl2 homolog, and two large clusters of miRNAs arise from introns within the BART region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Genomic locations of the EBV miRNA clusters

EBV miRNAs, like the majority of their cellular counterparts, are expressed from RNA polymerase II-driven long primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) transcripts which undergo multiple biogenesis steps in the nucleus and cytoplasm to generate a mature, RISC-associated miRNA [18]. Pri-miRNAs fold into long hairpins which are cleaved by nuclear Drosha into ~60 nt pre-miRNAs. Following nuclear export, the pre-miRNA is cleaved by cytoplasmic Dicer, and one strand of the ~22 nt miRNA duplex becomes associated with an Argonaute (Ago) protein and incorporated into RISC as the mature miRNA [5, 18–20]. An understanding of these biogenesis steps has significantly aided in developing experimental strategies to identify and detect novel viral miRNA species [13–16], ectopically express miRNAs ([21–23] and described in [24]), and isolate miRNA-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes to determine miRNA targets [21–23, 25–27]. High-throughput methods aimed at identifying miRNA targets in EBV-infected cells, such as PAR-CLIP [21–23, 27] and HITS-CLIP [26] (the PAR-CLIP protocol is described in detail elsewhere [28]), have benefited from this knowledge and led to the direct identification of hundreds of EBV miRNA targets related to cell survival, apoptosis, signaling, and immune evasion.

Broken into two major sections, this chapter describes current protocols (1) to identify and characterize miRNAs, including RISC-associated miRNAs, in EBV-infected cells using deep sequencing and bioinformatics tools and (2) to detect the expression of individual miRNAs using primer extension, stem-loop qRT-PCR, and luciferase assays.

2 Materials and Reagents

All reagents, tubes, pipette tips, and work areas should be RNase-free. Solutions should be prepared with ultrapure, nuclease-free water. Appropriate work practices and institutional disposal guidelines must be followed for working with phenol (TRIzol® Reagent), chloroform, and radioactivity.

2.1 RNA Isolation from EBV-Infected Cell Lines

TRIzol® Reagent (Life Technologies).

Chloroform.

Isopropanol (isopropyl alcohol).

Glycogen or GlycoBlue (optional).

95 % ethanol (optional).

Nuclease-free water.

2.2 RISC Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP lysis buffer: 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 0.5 % NP40, 0.5 mM DTT, and EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). For 50 mL of RIP lysis buffer, combine 2.5 mL 1 M HEPES, pH 7.5, 1.875 mL 4 M KCl, 0.2 mL 0.5 M EDTA, 50 μL 1 M NaF, 50 μL NP40 (or IGEPAL), 25 μL 1 M DTT, and 45.3 mL nuclease-free water. Dissolve protease inhibitor tablets according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Citrate-phosphate buffer: To prepare 1 L, combine 4.7 g citrate phosphate and 9.32 g Na2HPO4. Bring volume up to 1 L with ultrapure water. The pH should be pH 5.0.

Dynabeads®, Protein G (Life Technologies) and magnetic bead separator (i.e., DynaMag).

Anti-Ago2 (clone 9E8.2, Millipore) or pan-Ago antibody (Abcam ab57113 recognizes Ago1, Ago2, and Ago3; Diagenode 2A8 recognizes all four human Ago proteins) [29]. Alternatively, a FLAG-tagged Ago2 can be introduced into cells, and RISC-miRNAs can be immunoprecipitated with monoclonal antibodies to FLAG (i.e., clone M2, Sigma) [21].

RNase inhibitor (i.e., RNaseOUT Recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitor, Life Technologies).

NT2 buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.05 % NP40. To prepare 50 mL of NT2 buffer, combine 2.5 mL 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 7.5 mL 1 M NaCl, 50 μL 1 M MgCl2, 25 μL NP40 (or IGEPAL), and 40 mL nuclease-free water.

Proteinase K, PCR grade.

2.3 Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs

Total or RIP RNA (up to 1 μg).

Illumina TruSeq small RNA kit (or kit compatible with the platform of choice).

Thermocycler and nuclease-free 0.2 μL tubes.

10 % Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE) polyacrylamide gel, 1× TBE buffer, and electrophoresis apparatus.

0.3 M NaCl, glycogen, and 100 % ice cold ethanol for precipitation.

2.4 Primer Extension

Total RNA (5–10 μg, in water).

Primer design: DNA oligonucleotides used for miRNA detection by primer extension should be ~14–17 nt in length and perfectly complementary to the 3′-end of the miRNA of interest to allow extension of 5–7 nt.

Size markers: DNA or RNA oligonucleotides of discrete sizes (i.e., 18 and 24 nt in length) can be radiolabeled for use as size markers. Alternatively, the Decade Marker System (Life Technologies) can be used. Label according to manufacturer’s instructions.

[γ-32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/mL).

MicroBioSpin6 columns (BioRad).

-

The following reagents are included within the Primer Extension System (Promega):

T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) (NEB).

T4 PNK 10× buffer.

2× AMV primer extension buffer.

40 mM sodium pyrophosphate.

AMV reverse transcriptase (RT).

Nuclease-free, ultrapure water.

2× loading dye.

15 % TBE-Urea polyacrylamide gel, 1× Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer, and electrophoresis apparatus.

2.5 Stem-Loop qRT-PCR

For detection of many EBV and human miRNAs, predesigned assays are commercially available. Commercial miRNA PCR arrays are also available for profiling large sets of known miRNAs. For custom assays, design the following:

-

miRNA-specific stem-loop RT primer, where NNNNNN is complementary to the miRNA 3′-end:

5′-GTC GTA TCC AGT GCA GGG TCC GAG GTA TTC GCA CTG GAT ACG CAN NNN NN-3′.

miRNA-specific forward PCR primer, where NNN NNN NNN NNN NNN N is equivalent to the first 16 nt of the miRNA: 5′-GCG CNN NNN NNN NNN NNN NN-3′.

Reverse PCR primer: 5′-GTG CAG GGT CCG AGG T-3′.

miRNA-specific TaqMan® MGB-labeled probe, where NNN NNN is complementary to the 3′-end of the miRNA: 5′-TGG ATA CGA CNN NNN N-3′.

Reagents for the RT reaction (performed on a thermocycler): 5 μM annealed miRNA-specific stem-loop RT primer, 10 mM dNTPs, MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), RNase inhibitor, RNA template (50 ng/μL) (see Subheading 3.1), nuclease-free water, and 10× RT buffer, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 500 mM KCl, and 5.5 mM MgCl2.

Reagents for the qPCR reactions (performed on a real-time PCR machine): 2× Universal PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) or comparable, 50 μM forward and reverse PCR primers, 10 μM TaqMan® MGB probe, nuclease-free water, and 96-well optical plates suitable for real-time PCR.

2.6 Luciferase Indicator Assays

HEK293T cells, grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and antibiotics.

Dual-luciferase reporter vector such as psiCHECK-2 (Promega) with two perfectly complementary binding sites for a miRNA of interest cloned into the 3′-UTR of either renilla or firefly luciferase.

Source of viral or cellular miRNA with appropriate negative controls. This can be a miRNA expression vector such as pcDNA3 or lentiviral vector [21, 23, 24] containing ~200 nt of the primary miRNA cloned downstream of a promoter OR miRNA mimics (see [30] for custom design).

Transfection reagent such as Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) and Opti-MEM I reduced serum media.

Black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well tissue culture plates for transfections. Alternatively, transfections can be performed in 12-, 24-, or 48-well plates and lysates transferred to appropriate tubes/plates prior to addition of DLR substrate.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter (DLR) Assay System (Promega).

Luminometer capable of reading 96-well plates.

3 Methods

3.1 Identifying miRNAs in EBV-Infected Cells Using Small RNA Deep Sequencing

3.1.1 Isolating RNA from EBV-Infected Cells

Pellet suspension cells (~1000 × g for 5 min) and wash once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For adherent cells, remove media and wash 1× PBS. Add 1 mL TRIzol® per 1×107 cells and pipette up and down to lyse cells (see Note 1).

Perform phenol-chloroform extraction to isolate RNA from TRIzol®. Add 0.2 mL chloroform per 1 mL TRIzol. Vortex or invert to mix, and then centrifuge at >10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min to separate the aqueous (top) and organic (bottom) layers. Transfer aqueous layer to a new tube (if 1 mL TRIzol® was used, this volume should be about 0.5 mL). Optional: Perform additional chloroform extraction by adding one-volume chloroform to the aqueous layer, vortex or invert to mix, and centrifuge 10 min >10,000 × g to separate the layers. Transfer top layer to a new tube.

Precipitate RNA by adding 0.75 volumes of isopropanol to the aqueous layer, and incubate for >15 min at −80 °C or >30 min at −20 °C. For isolation of RNA from low cell numbers (<1×106), add 1 μL of glycogen during this step. Pellet RNAs at >15,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min. Remove all liquid and allow RNA pellet to air-dry for 2–3 min. Resuspend RNA in 50 μL nuclease-free water. Optional: The RNA pellet can be washed one to two times with ice cold 95 % ethanol prior to resuspension in water (see Note 2).

3.1.2 Isolating RISC-Associated miRNAs by Ago Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

The majority of assays to investigate miRNA levels use total RNA or size-fractionated RNA as input. Recent studies have demonstrated that the level of a miRNA in total RNA fractions does not accurately predict its inhibitory potential; rather, the level of RISC association is a more accurate indicator for miRNA activity [29]. The RIP protocol below is modified from a protocol by Keene et al. [31] to isolate RISC-associated RNAs using antibodies against Ago2, a key RISC component. This RIP method, following by deep sequencing (RIP-seq), has been used recently to interrogate RISC-associated miRNAs in lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) [22]:

Grow enough cells to obtain ~1 mL dry cell pellet (~50–100×106 cells or ~1–1.5 L of EBV B95-8 LCLs). Pellet cells by centrifugation at ~1000 × g for 5 min and wash two times with PBS (see Note 3). Resuspend pellet in three volumes of RIP lysis buffer and incubate on ice for 10 min. Clear lysate by centrifugation at >10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. Transfer lysate to a new tube (see Note 4).

Prepare magnetic Dynabeads (protein G) by transferring 30 μL beads to 1.5 mL tube and washing two times with 0.5 mL citrate-phosphate buffer. Resuspend beads in 60 μL of RIP lysis buffer and add 10 μL of anti-Ago2 antibody. Incubate on rotator for 45 min at room temperature.

Remove unbound antibody using the magnetic separator and wash beads one time with 1 mL of RIP lysis buffer. Resuspend beads in 60 μL RIP lysis buffer and add in full to cell lysate (see Note 5). Incubate at 4 °C on a rotator for 2–18 h.

Collect beads on ice using the magnetic separator and discard supernatant. Wash beads ten times in NT2 buffer (see Note 6).

Resuspend beads in 300 μL NT2 buffer (see Note 7). Add 10 μL RNase inhibitor and 30 μL (~25–30 μg) proteinase K to the bead mixture. Incubate at 55 °C for 30 min to release antibody/RISC-bound RNAs. Flick the tube every 5–10 min to mix.

Add 1 mL TRIzol® to the bead mixture to isolate RNAs. Proceed to the chloroform extraction and steps 2 and 3 in Subheading 3.1.1 above. Addition of glycogen is necessary during RNA precipitation and recovery. Resuspend RNA pellet in 10 μL nuclease-free water (see Note 8).

3.1.3 Deep Sequencing of Small RNAs

Among the most commonly used platforms for high-throughput sequencing of RNAs are 454 (Roche), SOLiD (Life Technologies/ Applied Biosystems), and Illumina. SOLiD and Illumina are preferred for small RNAs since both technologies yield millions of short reads. Two to five million reads generally provide enough complexity to have coverage of all miRNA isoforms in a given sample. Using the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (50 cycle, single-end reads), we generally multiplex 10–12 samples in a sequencing lane. This yields about 300 million reads total, with at least 25 million high-quality reads per sample. Sequencing library preparation kits are commercially available for each platform. When comparing multiple biological samples, it is highly recommended to use the same sequencing platform.

We have previously used the Illumina TruSeq small RNA kit with either 0.5–1 μg total RNA (see Subheading 3.1.1) or 0.2–0.5 μg RIP RNA as input (see Subheading 3.1.2) [22, 29]. RNAs are sequentially ligated to Illumina adapter sequences. Following adapter ligation, RNAs are reverse transcribed using primers complementary to the 3′-adapter, and cDNAs are PCR amplified with bar-coded primers for multiplexing. Importantly, a pilot PCR should be performed for each library to ensure that amplification occurs within the linear range. The pilot PCR is necessary to maintain library complexity and avoid over-amplifying highly expressed miRNAs. This can be set up using 15 % of the cDNA mixture and amplifying for 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18 cycles using the conditions outlined in the Illumina TruSeq manufacturer’s protocol. cDNAs are gel purified using a 10 % TBE polyacrylamide gel run at 200 V in 1× TBE buffer. Following staining with ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe, excise the ~145 nt cDNA band, place the gel slice in a 1.5 mL tube with 0.5 mL 0.3 M NaCl, and passively elute on a rotator at 4 °C for 16 h. The eluted cDNA is precipitated by transferring the 0.5 mL supernatant to a clean tube and adding 1 μL glycogen and two volumes of 100 % ethanol. Incubate at 20 °C for 30 min and pellet by centrifugation at >10,000 × g.

3.1.4 Bioinformatics Analysis of Sequencing Reads

Sequences should be obtained in fastq format (see Note 9). A number of open source tools are available for filtering and aligning reads:

Preprocessing the reads

For command-line users, the fast-x toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) provides scripts to remove adapter sequences and filter out low-quality and short reads <15 nt. A web-based version, Galaxy (www.usegalaxy.org), is available for those requiring access to resources for computationally intensive analyses.

Aligning reads and determining miRNAs

Strategy I: Using Bowtie [32] (or comparable alignment tool), align reads concurrently to the human (HG19) and appropriate EBV (i.e., AJ507799) genomes. For Bowtie or Bowtie2 alignments, we allow up to two mismatches and up to 25 unique locations for miR-seq and RIP-seq alignments (-v 2 -m 25). Genomic locations with reads falling into the best stratum (--best --strata) are kept for further analysis. To annotate miRNAs, compare read locations to the coordinates/sequences of the human and EBV miR-NAs from the most current version of miRBase (www.mir-base.org).

Strategy II: Use Perl-based scripts from miRDeep2 [33] to align reads and quantify miRNA read counts. miRDeep2 has dependencies on Bowtie and also requires miRNA sequences from the most current version of miRBase.

Identifying differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs

Once read counts per miRNA are obtained, we use the Bioconductor software package edgeR [34, 35] to normalize libraries and define DE miRNAs.

3.2 Detecting Individual miRNAs in EBV-Infected Cell Lines and Tissue Samples

Primer extension analysis is an effective method to identify 5′-end variations in viral and cellular miRNAs [36, 37] and often has a better sensitivity than Northern blotting to detect miRNAs. Unlike

3.2.1 Primer Extension

Northern blotting which allows for detection of both the precursor and mature miRNA, only the mature miRNA isoforms can be detected by primer extension:

Label the probe. Set up the following reaction in a nuclease-free, sterile 1.5 mL tube: 2 μL (10 pmol) primer (5 μM stock), 1 μL 10x T4 PNK buffer, 5 μL nuclease-free water, 1 μL T4 PNK, and 1 μL [γ-32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/mL). Incubate at 37 °C for 10–30 min. To remove unincorporated radionucleotides, add 90 μL of nuclease-free water to the labeling reaction, and pipette the entire volume onto prepared MicroBioSpin column. Spin for 2 min at 800 × g and collect labeled probe into a new tube (see Note 10).

Perform primer extension (see Note 11). Set up the following reaction in a nuclease-free 1.5 mL tube: 5 μg total RNA (see Note 12), 1 μL labeled primer probe, 5 μL 2× AMV PE buffer, and nuclease-free water to 11 μL. Incubate at 95 °C for 2min to denature RNA and then, anneal at 37 °C for 20 min.

At room temperature, set up the following: 11 μL annealed primer/RNA from step 2, 1.4 μL sodium pyrophosphate, 5 μL 2× AMV PE buffer, 1.6 μL nuclease-free water, and 1 μL AMV RT (should be added last). Pipette up and down to mix. Incubate for 5 min at room temperature, and then extend for 30 min at 42 °C. To terminate reaction, add 20 μL 2× formamide loading buffer and heat inactivate at 95 °C for 10 min.

Analyze primer extension products on a 15 % TBE urea gel (see Note 13). Prepare a vertical gel containing 15 % acrylamide (19:1 acrylamidebis), 7 M urea, and 1× TBE buffer. Boil samples (including negative control reaction) and size markers briefly prior to loading. Run at 250 V in 1× TBE buffer until the bromophenol blue dye is within 1 cm of the bottom. Expose gel to X-ray film overnight at −80 °C or to a phosphorimaging screen.

3.2.2 Stem-Loop qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR-based assays are perhaps the most widely used method for detecting individual miRNAs due to their relative ease and little hands-on time. miRNA stem-loop qRT-PCR relies on knowing the precise 3′-end of a miRNA. Several studies have profiled miRNAs in EBV-infected cells using deep sequencing [16, 17, 21–23, 26, 38]; thus, the 3′-ends of these miRNAs are generally known:

Set up the following for reverse transcription by preparing master mix for multiple samples: 0.2 μL dNTPs, 2 μL 10× RT buffer, 0.2 μL RNase inhibitor, 0.3 μL stem-loop RT primer (5 μM stock), 1 μL MultiScribe RT, 100 ng RNA, and nuclease-free water to 20 μL (see Note 14).

Incubate at 16 °C for 30 min to anneal RT primer and then at 42 °C for 30 min. Heat inactivate at 85 °C for 10 min.

Set up the following for TaqMan® qPCR (prepare master mixes for multiple samples): 10 μL 2× Universal PCR Master Mix, 0.3 μL each forward and reverse PCR primer (50 μM stock), 0.3 μL TaqMan® MGB probe (10 μM stock), and nuclease-free water to 18 μL. Pipette 18 μL of the PCR mix into each well of a 96-well qPCR plate. Add 2 μL cDNA (10 % of RT reaction from above) to each well. At minimum, technical duplicates should be set up for each experiment.

Perform qPCR using the following conditions: 40 cycles each consisting of (step 1) 2 min at 50 °C, (step 2) 10 min at 95 °C, and (step 3) 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C.

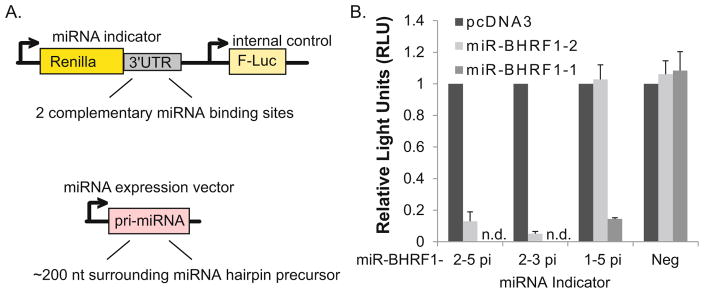

3.3 Detecting EBV miRNA Activity Using Luciferase Indicator Assays

Luciferase reporter assays are commonly used to measure miRNA activity following ectopic miRNA expression (i.e., for miRNA target validation, when a 3′-UTR of a gene of interest is cloned behind luciferase) or following disruption of miRNA function (i.e., to demonstrate inhibition in cells containing a sponge inhibitor, decoy, or locked nucleic acid inhibitor directed against a specific miRNA) [21–24, 30]. miRNA luciferase indicators are highly effective at demonstrating miRNA activity from miRNA expression plasmids (Fig. 2) as well as in infected cells [21, 23, 27]:

Fig. 2.

(a) Example of luciferase reporter (miRNA indicator) and miRNA expression vector design. (b) EBV BHRF1 miRNAs inhibit luciferase expression from miRNA indicators. HEK293T cells, plated in 96-well black, clear-bottom plates, were co-transfected with 20 ng miRNA indicator and 250 ng miRNA expression vector using Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer’s protocol. 48 h post-transfection, cells were lysed in 1× passive lysis buffer and analyzed on a luminometer using the DLR (Dual-Luciferase Reporter) Assay System. Light values are relative to an internal control and normalized to empty vector (pcDNA3). A luciferase vector lacking miRNA-binding sites is used as a negative control (Neg). Shown is the average of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. n.d. = not determined for miR-BHRF1-1

Plate HEK293T cells (1 × 106 cells per plate) in 96-well black-well plates in complete media one day prior to transfection.

Per well, combine 20 ng luciferase indicator vector (i.e., psi-Check2 containing two tandem miRNA-binding sites within the luciferase 3′-UTR), 250 ng miRNA expression plasmid (or control) (see Note 15), Opti-MEM reduced serum media, and transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s protocol, and add dropwise onto cells.

Incubate for 48–72 h to allow for miRNA expression. Lyse cells in 1× passive lysis buffer, and analyze luciferase activity using the DLR system and luminometer (see Note 16).

Acknowledgments

R.L.S. is supported by NIH grant K99-CA175181. The author thanks the current and former members of Dr. Bryan Cullen’s laboratory at Duke University, the members of Dr. Jack Keene’s lab at Duke University, and the members of Dr. Jay Nelson’s laboratory at Oregon Health and Science University for the discussions, troubleshooting, and optimizing protocols over the years.

Footnotes

Lysate can be stored at −80 °C for several weeks or placed on ice prior to step 2.

The use of <95 % ethanol (i.e., 70 % ethanol) is not recommended for washing as this can partially elute small RNAs from the RNA pellet.

The pellet can be stored at −80 °C for several months. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

25 μL of cleared lysate can be saved for Western blot (WB) analysis.

The slurry can be spiked with 1–2 μL RNase inhibitor to prevent RNA degradation.

Washing is critical to eliminate background. 25 μL of the supernatant following IP as well as portions of the wash steps can be saved for WB analysis.

25 μL of resuspended beads can be saved and boiled in Laemmli buffer for WB analysis along with other saved samples (see Notes 3 and 5) to ensure adequate Ago2 IP.

Recovered RNA can be used directly for qRT-PCR analysis or to generate deep-sequencing libraries (RIP-seq). 0.5–2 μg of RNA is a common yield from ten million cells.

The Illumina platform provides reads in basespace format (fastq). For SOLiD users, reads are in colorspace format (csfasta) and require alternate workflows other than described here. Note that for either platform sequencing files are several gigabytes in size and require appropriate computational resources for storage and manipulation.

Purified probe for primer extension can be stored at −80 °C or used immediately. Measuring radionucleotide incorporation on a scintillation counter is recommended.

Master mixes for the primer mixture and extension mixture should be prepared when analyzing multiple RNA samples. Additionally, a negative control reaction should be prepared for each primer probe containing water in place of RNA template.

At least 5–10 μg of high-quality, total RNA is recommended for detection of most miRNAs. This amount can be increased to 15 μg for lowly expressed miRNAs.

Due to the small size of the primer extension product (~15 nt probe, ~22 nt product), a 15 % denaturing polyacrylamide gel is recommended. Wells of the gel should be rinsed with 1× TBE buffer to remove urea prior to loading samples.

Appropriate controls for assaying viral miRNAs include RNA from uninfected cells or from cells infected with a miRNA knockout virus (i.e., EBV BHRF1 miRNA mutant viruses [40, 21, 39]). Standard curves can be generated using RNA oligonucleotides that match the specific miRNA sequence. Separate RT reactions need to be set up for each standard curve dilution.

Suggested controls include additional miRNA expression plasmids that should not interact with the luciferase indicator vector as well as a control luciferase vector lacking miRNA-binding sites (“Neg” in Fig. 2). Technical replicates, i.e., triplicates, should be set up for each condition. psiCheck2 expresses both Renilla and firefly luciferase. If another type of luciferase vector is used, an internal control luciferase plasmid should be spiked into the transfections.

The level of luciferase indicator knockdown via a miRNA with perfect complementarity to the inserted binding sites should be in the range of >75–90 %. The 25–75 % inhibition is normally observed for luciferase 3′-UTR reporters with mismatches to the miRNA of interest, i.e., a 3′-UTR containing a miRNA seed match or an indicator with imperfect sites.

References

- 1.Cameron JE, Fewell C, Yin Q, et al. Epstein-Barr virus growth/latency III program alters cellular microRNA expression. Virology. 2008;382:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron JE, Yin Q, Fewell C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces cellular MicroRNA miR-146a, a modulator of lymphocyte signaling pathways. J Virol. 2008;82:1946–1958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02136-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang J, Lee EJ, Schmittgen TD. Increased expression of microRNA-155 in Epstein-Barr virus transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:103–106. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marquitz AR, Mathur A, Chugh PE, et al. Expression profile of microRNAs in Epstein-Barr virus-infected AGS gastric carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2014;88:1389–1393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02662-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:123–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forte E, Luftig MA. The role of microRNAs in Epstein-Barr virus latency and lytic reactivation. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrazek J, Kreutmayer SB, Grasser FA, et al. Subtractive hybridization identifies novel differentially expressed ncRNA species in EBV-infected human B cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linnstaedt SD, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, et al. Virally induced cellular miR-155 plays a key role in B-cell immortalization by EBV. J Virol. 2010;84:11670–11678. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01248-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarro A, Gaya A, Martinez A, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:2825–2832. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leucci E, Onnis A, Cocco M, et al. B-cell differentiation in EBV-positive Burkitt lymphoma is impaired at posttranscriptional level by miRNA-altered expression. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1316–1326. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, et al. A MicroRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang G, Zong J, Lin S, et al. Circulating Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs miR-BART7 and miR-BART13 as biomarkers for nasopharyngeal carcinoma diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E301–E312. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304:734–736. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA. 2006;12:733–750. doi: 10.1261/rna.2326106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai X, Schafer A, Lu S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e23. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen SJ, Chen GH, Chen YH, et al. Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus miRNAome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu JY, Pfuhl T, Motsch N, et al. Identification of novel Epstein-Barr virus microRNA genes from nasopharyngeal carcinomas. J Virol. 2009;83:3333–3341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01689-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skalsky RL, Corcoran DL, Gottwein E, et al. The viral and cellular microRNA targetome in lymphoblastoid cell lines. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002484. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skalsky RL, Kang D, Linnstaedt SD, et al. Evolutionary conservation of primate lymphocryptovirus microRNA targets. J Virol. 2014;88:1617–1635. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02071-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottwein E, Corcoran DL, Mukherjee N, et al. Viral microRNA targetome of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell lines. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottwein E, Cullen BR. Protocols for expression and functional analysis of viral microRNAs. Methods Enzymol. 2007;427:229–243. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)27013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolken L, Malterer G, Erhard F, et al. Systematic analysis of viral and cellular microRNA targets in cells latently infected with human gamma-herpesviruses by RISC immunoprecipitation assay. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley KJ, Rabinowitz GS, Yario TA, et al. EBV and human microRNAs co-target oncogenic and apoptotic viral and human genes during latency. EMBO J. 2012;31:2207–2221. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang D, Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. EBV BART MicroRNAs target multiple pro-apoptotic cellular genes to promote epithelial cell survival. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004979. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, et al. PAR-CliP-a method to identify transcriptome-wide the binding sites of RNA binding proteins. J Vis Exp. 2010;41 doi: 10.3791/2034. pii: 2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores O, Kennedy EM, Skalsky RL, et al. Differential RISC association of endogenous human microRNAs predicts their inhibitory potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:4629–4639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hook LM, Landais I, Hancock MH, et al. Techniques for characterizing cytomegalovirus-encoded miRNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1119:239–265. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-788-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keene JD, Komisarow JM, Friedersdorf MB. RIP-Chip: the isolation and identification of mRNAs, microRNAs and protein components of ribonucleoprotein complexes from cell extracts. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:302–307. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedlander MR, Mackowiak SD, Li N, et al. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:37–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anders S, McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, et al. Count-based differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data using R and Bioconductor. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1765–1786. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manzano M, Forte E, Raja AN, et al. Divergent target recognition by coexpressed 5′-isomiRs of miR-142-3p and selective viral mimicry. RNA. 2015;21:1606–1620. doi: 10.1261/rna.048876.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzano M, Shamulailatpam P, Raja AN, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a mimic of cellular miR-23. J Virol. 2013;87:11821–11830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01692-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motsch N, Alles J, Imig J, et al. MicroRNA profiling of Epstein-Barr virus-associated NK/T-cell lymphomas by deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feederle R, Haar J, Bernhardt K, et al. The members of an Epstein-Barr virus microRNA cluster cooperate to transform B lymphocytes. J Virol. 2011;85:9801–9810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05100-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feederle R, Linnstaedt SD, Bannert H, et al. A viral microRNA cluster strongly potentiates the transforming properties of a human herpesvirus. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]