Abstract

Women who have sex with women (WSW) have long been considered at low risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, limited research has been conducted on WSW, especially those living in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). We reviewed available research on sexual health and risk behaviors of WSW in LMICs. We searched CINAHL, Embase, and PubMed for studies of WSW in LMICs published between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2013. Studies of any design and subject area that had at least two WSW participants were included. Data extraction was performed to report quantifiable WSW-specific results related to sexual health and risk behaviors, and key findings of all other studies on WSW in LMICs. Of 652 identified studies, 56 studies from 22 countries met inclusion criteria. Reported HIV prevalence among WSW ranged from 0% in East Asia and Pacific and 0%–2.9% in Latin America and the Caribbean to 7.7%–9.6% in Sub-Saharan Africa. Other regions did not report WSW HIV prevalence. Overall, many WSW reported risky sexual behaviors, including sex with men, men who have sex with men (MSM), and HIV-infected partners; transactional sex; and substance abuse. WSW are at risk for contracting HIV and STIs. While the number of research studies on WSW in LMICs continues to increase, data to address WSW sexual health needs remain limited.

Key words: : lesbian and bisexual women (LB), low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), sexual health, risk behaviors, women who have sex with women (WSW)

Introduction

Female-to-female sexual contact has long been assumed to comprise low-risk behavior for contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV-1 infection. This assumption has contributed to the exclusion of lesbian and bisexual women, broadly identified as women who have sex with women (WSW), from the overall HIV/STI prevention discourse.1 As their sexual health concerns are commonly dismissed, many WSW believe they are at low risk of acquiring STIs.2 Contrary to this perception, research suggests that WSW engage in high-risk sexual behavior with both male and female partners.3–5 In addition, recent data indicate that female-to-female sexual contact can transmit STIs such as human papillomavirus,6 genital herpes,7 and syphilis.8 In March 2014, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the first confirmed case of HIV transmission by female-to-female sexual contact.9 These studies demonstrate that regardless of sexual orientation, the sexual health risks of WSW are not negligible.

Research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health has been an emerging area of study since the HIV epidemic began in the 1980s. However, the pace of this research has not been equal across countries with different economic statuses, particularly low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), nor has it been equal among LGBT subgroups. Although the men who have sex with men (MSM) population is well studied in the United States, a systematic review by Baral and colleagues found only 83 published studies from 2000–2006 that reported HIV prevalence among MSM living in 38 LMICs.10 A review of epidemiological studies on WSW living in LMICs suggests that research in this population is even scarcer. With the limited research on WSW in LMICs, the assumption that current HIV/STI prevention strategies are adequately serving this population is not valid.

To address this concern, we conducted a systematic review of studies published between 1980 and 2013 that reported the experience of WSW living in LMICs. Our goal was to quantify research output in this area by World Bank geographic region and year of publication. In addition, we systematically collected and collated the major reported findings in the areas of sexual health and risk behaviors.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for studies published between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2013. We chose 1980 as our start date to capture research on WSW populations since the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. We used Endnote version X7 to organize and review articles and citations.

The search included LMIC keywords and terms associated with WSW: (homosexuality, female Medical Subject Headings [MeSH]) OR (“bisexuality” [MeSH] OR “same sex partner”*) AND female [MeSH]) OR “lesbian”* OR “bisexual women” OR “homosexual women” OR “homosexual female”* OR “female homosexual”* OR “women who have sex with women” OR “WSW”). LMICs were those countries with a gross national income per capita of less than US$12,746 in 2013.11

Studies of any design were included if the study population had two or more WSW or women who self-identified as lesbian or bisexual. Studies with small sample sizes were included to ensure we did not lose insights from exploratory studies. Reviews and case studies of a single individual were excluded from our analysis. We also excluded articles that studied transgender persons and their partners.

Screening and data extraction

After removal of duplicates, publications from all three databases were screened by two independent reviewers (Susana A. Tat [SAT], and either Susan M. Graham [SMG] or Jeanne M. Marrazzo [JMM]). Reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of each publication and identified those that potentially met our selection criteria. Full-text copies of these studies were obtained and reviewed in detail. When two reviewers disagreed on inclusion of an article, the third reviewer made the final decision.

Data were extracted by one reviewer (SAT) using two data extraction forms: one for articles with quantifiable findings on WSW-specific sexual health and behavioral risks (Form 1), and the other for findings not specifically related to sexual health or risk behavior (Form 2). Both forms included details on author, year, geographic setting, sample size, and data collection method. Findings abstracted using Form 1 included WSW-specific HIV and STI prevalence, male sexual partners, forced sex, and substance use (alcohol, tobacco, and/or illicit drugs). All studies not reporting any of these findings were extracted using Form 2.

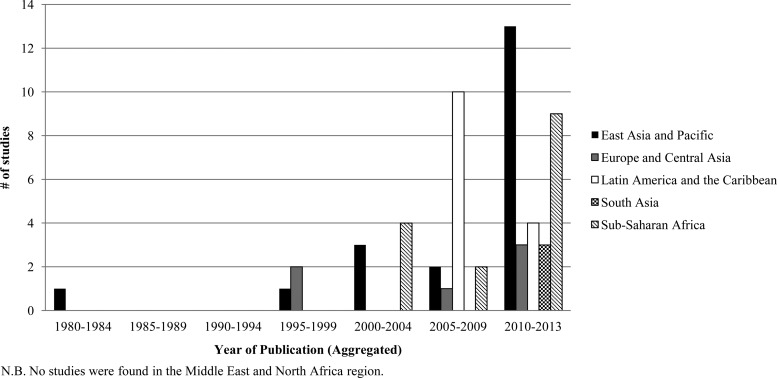

The included publications were sorted into the following World Bank geographic regions: East Asia and Pacific; Europe and Central Asia; Latin America and the Caribbean; Middle East and North Africa; South Asia; and Sub-Saharan Africa. We tallied and graphed the number of publications in each region categorized by publication year. If a study had participants from more than one region, it was counted in the tally for each region. If a study had participants from several countries within the same region, it was only counted once for that region.

Results

Studies identified

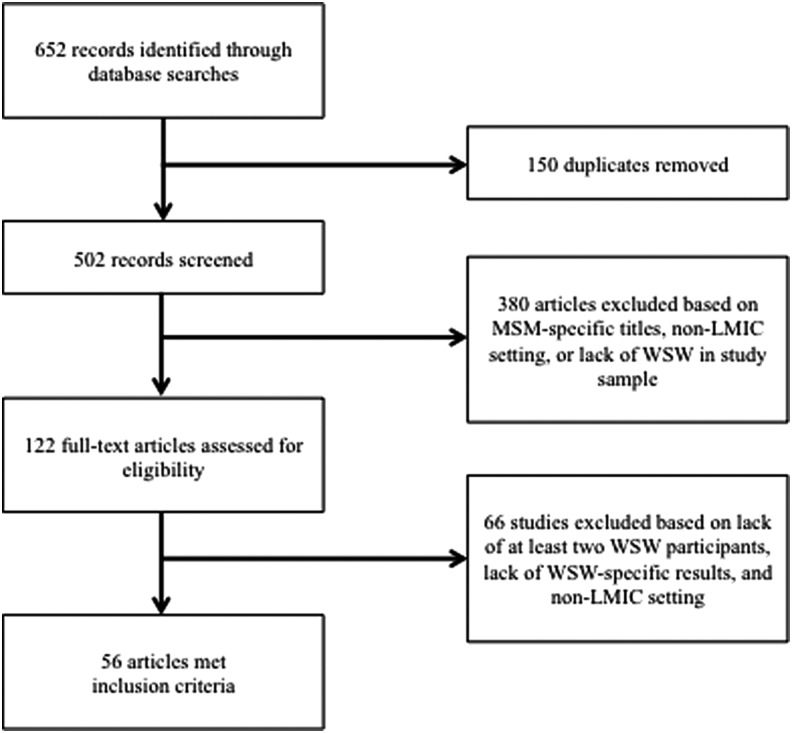

Our search identified 652 potentially eligible studies related to WSW in LMICs, of which 502 were unique publications (Figure 1). We excluded 380 articles based on ineligible population (e.g., MSM only), setting, or article type (e.g., reviews or case studies). We obtained 122 full-text articles to assess in detail for eligibility and further excluded 66 articles that did not study at least two WSW. Fifty-six articles from 22 different countries meeting our inclusion criteria reported data on WSW from East Asia and Pacific (20 articles), Europe and Central Asia (4 articles), Latin America and the Caribbean (16 articles), South Asia (3 articles), and Sub-Saharan Africa (15 articles). No publications were identified from the Middle East and North Africa region. A graph of these studies by year and by region shows an increase in the number of publications in all five regions over time (Figure 2), with more than half of all included articles (32) published between 2010 and 2013.

FIG. 1.

Literature selection flow chart.

FIG. 2.

Publications with two or more women who have sex with women (WSW) in study sample by region over time. Of note, no original research studies from the Middle East and North Africa region were found.

Sexual Health and Risk Behaviors

Of the 56 articles included in our review, 24 reported quantitative results on the sexual health and risk behaviors of WSW. These 24 articles were from the following regions: East Asia and Pacific; Latin America and the Caribbean; and Sub-Saharan Africa (Table 1).

Table 1.

Women Who Have Sex with Women Sexual Health and Risk Behaviors

| Author (Year) setting | Sample size | Data collection method | HIV+ rate | STI rate | Had male partners | Experienced forced sex | Drug use | Other key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and Pacific | ||||||||

| Lau (2006)12 China |

1,571 men; 3,257 women age 18–59 years: 95 women w/same-sex partner in last 12 months | Telephone Survey | - | - | 76.6% were married | - | 1.1% had illicit substance use in past year; 1.1% had 11+ cigarettes/day; 0% drinks 5+ servings every time | 75.6% had at least one sexual problem; 28.4% perceived adequacy of sexual knowledge. |

| Lieh-Mak (1983)13 China |

15 married heterosexual women; 15 lesbians | Semi-Structured Interview | - | - | 40.0% had sex w/ men in lifetime; 26.7% were married | - | - | 60.0% of lesbians had first same-sex physical experience at ages 15–19 years. |

| Liu (2012)14 China |

150 WSW | Questionnaire; Clinical samples | 0% | 16.1% gonorrhea; 4.0% chlamydia; 0.7% syphilis; 0.7 % HBV; 0.7% HCV; 8.7% candidiasis; 0.7% trichomoniasis; 34.7% overall rate | 12.0% had sex w/ men in past year; 46.0% were married | - | - | 50.0% (9/18) used condoms during last sexual act w/ men; 33.0% had STI symptoms in past year but only 36.8% sought medical care. |

| Patel (2013)15 Thailand |

121 women age 18–24 years: 37 self-identified as LB | Questionnaire | - | - | 27.0% reported bisexual behavior | - | 32.0% ever used methamphetamine; 57.0% classified as harmful drinkers | LBs had higher number of lifetime sexual partners; more harmful drinking; earlier sexual debut; higher alcohol expectancy scores. |

| Tangmunkongvorakul (2010)48 Thailand |

1,750 adolescents aged 17–20 | Questionnaire/Interview | - | - | - | - | - | 9.2% females self-identified as tom (female homosexual w/ masculine traits), dii (feminine homosexual female), or bisexual; 5.7% were questioning; tom/dii females learned about female-female sexual practices via porn, and magazines. |

| Van Griensven (2004)16 Thailand |

1,725 vocational school students age 15–21 years: 93 of 857 females self-identified as LB | Audio-Computer Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) | - | - | 81.8% had first sexual contact with men; 56.4% had steady male partner | 32.2% were sexually coerced | 78.5% had 3+ drinks at least 5 times in past 3 months; 31.2% ever used methamphetamine; 8.6% marijuana; 2.2% opiates; 3.2% injected drugs | 14.1% of LBs provided sex for money, gifts or favors. |

| Wang (2012)18 China |

224 WSW | Survey; Clinical samples | 0% | 15.8% gonorrhea; 3.5% chlamydia; 0.5% syphilis; 0.9% HBV; 0.5% HCV; 6.9% candidiasis; 14.4% bacterial vaginosis; 26.8% overall rate | 2.2% married to men (2/5 married to MSM) | - | - | G-spot seeking during sex bleeding was associated w/ STI in univariable analysis. |

| Wang (2012)17 China |

224 WSW | Survey; Interview | - | - | 10.7% in past year; 1.8% married to men | - | In the past year, 79.5% drank alcohol; 46.6% drank before sex; 3.6% ever used drugs | 54.2% (13/24) used condom during last sexual act w/ men; 34.3% had 1+ sex partner in past year; 13.5% used sex toy w/ female partner in past year; 43.3% had consistent condom use w/ sex toys w/ female partners; 65.2% (120/184) had G-spot stimulation and 49.2% (59/120) bled during/after sex. |

| Whitam (1998)19 Philippines (Brazil; Peru; U.S.) |

49 heterosexual women and 55 lesbians | Questionnaire | - | - | 5.7% of lesbians had first sexual contact with men | - | - | Lesbians had earlier sexual contact than heterosexual women. |

| Author (Year) setting | Sample size | Data collection method | HIV+ rate | STI rate | Had male partners | Experienced forced sex | Drug use | Other key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||||||||

| Barbosa (2006)49 Brazil |

3,600 households - representing 76% of Brazilian population in urban areas | Population-Based Survey | - | - | - | - | - | Proportion of female population who reported same-sex relations during their lifetime remained constant at 1.7% from 1997 to 1998, but had declined from 3.0% in the previous 5 years. |

| Caceres (1997)21 Peru |

611 adolescents age 16–17 years; 607 young adults age 19–30 years | Questionnaire; Serologic Test | 0% | - | 0.3% adolescent and 3.7% young adult females ever had both heterosexual and homosexual sexual experiences | - | - | 3.0% adolescent and 4.3% young adult females had had homosexual sex. Female homosexuality might have protective effect from sexual problems and lower risk of STIs. |

| Cardoso (2006)33 Brazil |

478 injection drug users: 102 women | Structured Interview; Questionnaire | - | - | - | - | - | 14.7% of the female injection drug users reported any lifetime same-sex relations. |

| Ortiz-Hernandez (2005)22 Mexico | 506 LGBs: 188 LB women | Questionnaire | - | - | - | 3.0% were raped | 21.0% prevalence of alcoholism | 44.0% of LBs had suicidal ideation; 21.0% attempted suicide; 33.0% with mental disorders. |

| Ortiz-Hernandez (2006)23 Mexico |

506 LGBs: 188 LB women | Questionnaire | - | - | - | 3.0% LB were raped in past year; 8.0% raped in adult life age 18+. | - | 22.0% of LBs were sexually harassed and 16.0% were sexually molested as adults. |

| Ortiz-Hernandez (2009)34 Mexico |

12,795 youths ages 12–29 years: 80 of 7,245 females self identify as LB | Questionnaire/Interviews | - | - | - | - | Cigarette use: 48.4% lifetime; 30.9% current; 23.9% greater than 6 cigarettes/day; Alcohol use: 55.9% lifetime; 44.0% current; 1.1% greater than six drinks/week | 1.1% of females ever had sexual experience w/ same-sex. LB women have higher prevalence of cigarette and alcohol use than heterosexual women. |

| Pinto (2005)20 Brazil |

145 WSW ages 18+ years | Questionnaire; Clinical Samples | 2.9% | 33.8% bacterial vaginosis; 3.8% trichomonas; 25.6% fungi; 1.8% chlamydia; 7.0% HBV; 2.1% HCV; 6.2% HPV | 66.2% had first sexual contact with men; 23.4% sex with men in past year; 36.6% in the past 3 years, of those, 32.0% had MSM partners | - | 74.2% overall drug use; 40.2% used marijuana in past year; 16.1% used cocaine in past year; 46.9% cigarette use; 62.1% alcohol use | 38.6% had previous STI; 54.5% used condoms when sharing sex toys w/ females; 12.4% had sex with known HIV+ partners; 7.6% exchanged sex for money or goods; 45.5% (n=22) used condoms w/ males in past 3 months. |

| Traeen (2005)50 Cuba (India, Norway, South Africa) |

339 university students in Havana: 132 heterosexual women, 16 self-identified LB | Questionnaire | - | - | - | - | - | 81.0% of LBs and 3.0% of heterosexual women had same-sex sexual experience; LB women scored significantly lower on the subjective happiness scale; reported being more fearful and more angry than heterosexual women |

| Whitam (1998)19 Brazil; Peru (Philippines; U.S.) |

Brazil: 61 lesbians and 61 heterosexual women; Peru: 42 lesbians and 49 heterosexual women | Questionnaire | - | - | 36.1% Brazilian and 57.4% Peruvian lesbians had first sexual contact with men | - | - | Lesbians had earlier sexual contact than heterosexual women. Social norms affect lesbian sexuality and identity. |

| Author (Year) Setting | Sample Size | Data Collection Method | HIV+ Rate | STI Rate | Had Male Partners | Experienced Forced Sex | Drug Use | Other Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||||

| Dingeta (2012)51 Ethiopia |

1272 undergraduate students | Questionnaire | - | - | - | - | - | 1.2% (5/417) of females reported sex with same-sex. |

| Ephrem (2011)24 Ethiopia |

5 self-identified lesbians | Semi-Structured Questionnaire | - | - | 80.0% ever had sex with men | - | - | Ethiopian anti-gay laws negatively impact lives, experienced sexual agency despite repression, and sexual fluidity. |

| Graziano (2004)28 South Africa |

4 WSW and 3 MSM, age 18–32 years | Photovoice; Interview | - | - | - | 100% of WSW were raped | - | Participants desired health and sexuality education but thought healthcare workers lack training and acceptance of LBs. |

| Matebeni (2013)25 Namibia; South Africa; Zimbabwe |

24 WSW self-identified lesbians, age 18+ living with HIV, and had female sexual partner in past year | Semi-Structured Interview | 100% | - | 79.2% had sex with men ever; 8.3% were married | 33.3% were raped | - | 37.5% reported HIV infection through their former male partners; 66.7% have children; 20.8% never had a male partner; 37.5% of those who were raped attribute HIV positivity to rape. |

| Nicholas (2004)52 South Africa |

1,292 first year university students | Questionnaire | - | - | - | - | - | 3.5% (27/775) females participated in mutual masturbation; 3.0% (23/775) females participated in oral sex with other females. |

| Poteat (2013)27 Lesotho |

250 WSW age 18+ with female sexual contact in past 12 months | Survey; Focus Groups; Interview | 7.7% | 4.0% diagnosed w/ a STI at clinic in past year | 43.0% had regular male partner; 12.2% had 3+ male partners in past year; 26.3% ever married | - | - | 40.0% had both male and female partners in past year; 48.0% used condom with men at last sex; 13.4% used dental dam with women at last sex; 63.0% tested for HIV; 12.4% had STI symptoms. |

| Sandfort (2013)26 Botswana; Namibia; South Africa; Zimbabwe |

591 WSW age 18+ | Questionnaire | 9.6% | - | 47.2% ever had consensual sex with men; nearly 20% had sex with men in past year; 8.1% ever married | 31.1% experienced forced sex by men or women | 50.1% had lifetime recreational drug use; 2.1% had lifetime intravenous drug use | 18.6% had transactional sex; 23.7% have children; forced sex is risk factor for HIV infection. |

| Traeen (2009)50 South Africa (Cuba; India; Norway) |

182 university students in Cape Town: 83 heterosexual women, 34 self-identified LB women | Questionnaire | - | - | - | - | - | 9.0% of LB women and 7.0% of heterosexual women had same-sex sexual experience. No significant difference of reported quality of life between heterosexual women and LB women. |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infections; LB, lesbian and/or bisexual (women); MSM, men who have sex with men; WSW, women who have sex with women.

East Asia and Pacific

Eight of nine studies from China, Thailand, and the Philippines asked whether WSW had had male partners.12–19 From 1.8%–76.6% of WSW were married to men.12–14,17,18 In two Chinese studies, 10.7%17 and 12.0%14 reported sexual contact with a man in the past year. In another from Thailand, 81.8% had had their first sexual contact with men and 32.2% had ever experienced sexual coercion.16 These studies also reported the following HIV risk factors: low condom use at last sexual encounter with a man (50.0%–54.2%);14,17 transactional sex (14.1%);16 and bleeding during or after sex with female partners (49.2%).17 In one Thai study, WSW reported more lifetime sexual partners and earlier sexual debut than heterosexual women.15 Two Chinese studies collected clinical samples for STI and HIV testing.14,18 Both tested for gonorrhea, chlamydia, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and vulvovaginal candidiasis. One study also tested for bacterial vaginitis18 and the other for trichomoniasis.14 The prevalence of any of these STI ranged from 26.8%–34.7%; HIV prevalence was 0% in both studies.14,18

Latin America and the Caribbean

Three studies from Brazil and Peru surveyed WSW about male partners: 36.1%–66.2% reported first sexual contact with a man;19,20 23.4% had had sex with one or more men in the past year;20 and 0.3% of adolescent and 3.7% of young adult females reported both heterosexual and homosexual experiences.21 In one Brazilian study, 32.0% of the participants who reported sex with a man in the past 3 years had had male partners who were homosexual or bisexual.20 Two Mexican studies reported that 3.0% of WSW had been raped in the past year,22,23 while 8.0% had ever been raped in adult life.23 Data on the following risk factors were also reported: transactional sex (7.6%); sex with HIV-positive partners (12.4%); and condom use with male partners in the past 3 months (45.5%).20 HIV prevalence was 2.9% among Brazilian WSW.20 In a Peruvian study, HIV prevalence was 0% among adolescent and young adult females.21

Sub-Saharan Africa

Despite having the majority of the world's people living with HIV, only eight studies from this region reported data on sexual health and risk behaviors of WSW. Four studies surveyed WSW about male partners: 47.2%–80.0% had ever had sex with men;24–26 nearly 20% reported sex with a man in the past year;26 and 8.1%–26.3% had ever been married.25–27 Three studies reported data on forced sex. All four WSW in a participatory action research project in South Africa had been raped,28 while from 31.1%–33.3% of WSW in two multi-national studies reported forced sex by men or women.25,26 WSW who had experienced forced sex were more likely to be HIV-positive.26 Data on the following risk behaviors were also reported: transactional sex (18.6%);26 condom use in last sexual encounter with male partners (48.0%);27 and having both male and female partners in the past year (40.0%).27 Among 591 WSW participants from Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, reported HIV prevalence was 9.6%.26 In Lesotho, reported HIV prevalence was 7.7% and was associated with reporting ≥3 male partners or partners of both sexes in the past year, and with a history of STIs.27 In a multinational study of self-identified lesbians living with HIV, more than one third of participants thought they had acquired HIV through male partners.25

Substance Abuse

Alcohol consumption and illicit drug use are a cause for concern among WSW, as both behaviors are associated with acquisition of STIs and HIV.29–32 Eight studies presented quantitative results on WSW substance use.

East Asia and Pacific

In one Chinese study, 1.1% of WSW reported illicit substance use in the past year.12 In another Chinese study, 79.5% of WSW reported alcohol consumption in the past year, of whom 46.6% drank alcohol before engaging in sex.17 In two Thai studies, 31.2%–32.0% of WSW reported ever using methamphetamine, versus 13.0%–16.7% of heterosexual women.15,16 In one study, 57.0% of WSW were classified as harmful drinkers according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).15 In the other study, 78.5% of WSW reported consumption of ≥3 drinks at least five times in the last three months.16

Latin America and the Caribbean

In one Brazilian study, 14.7% of female injection drug users (IDU) reported ever having same-sex relations.33 In another Brazilian study, WSW reported frequent use of substances in the past year: alcohol (62.1%), cigarettes (46.9%), marijuana (40.2%), and cocaine (16.1%).20 In a Mexican study, alcoholism was identified by AUDIT in 21.0% of WSW participants.22 In a national survey of Mexican youth, WSW reported a higher prevalence of current alcohol use than heterosexual females, at 44.0% versus 15.7%.34

Sub-Saharan Africa

Among 591 South African WSW, 50.1% had ever used recreational drugs, while 2.1% had ever used intravenous drugs.26

Other Findings

Many of the articles that did not report quantitative results were exploratory, covering topics such as social pressures, stigma, and discrimination; gender and sexual identity; mental health and well-being; knowledge of sexual health risk; healthcare access; and intimate partner violence (Table 2). Some WSW postpone coming out to their families due to social and familial pressures and expectations of heterosexuality.35–40 Some feel pressured to marry men, while others hide their sexual identity due to fear of social exclusion, discrimination, and violence.41–44 Anti-gay laws negatively affect homosexuals and put them under distress.24,45 Moreover, WSW desire sexual health education, but feel uncomfortable reporting their sexual practices and revealing their sexual identities to healthcare providers.45–47 They also think healthcare providers lack training to work with non-heterosexual populations.28

Table 2.

Other Studies on Women Who Have Sex with Women

| Author (Year) setting | Sample size | Data collection method | Subject area | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and Pacific | ||||

| Baba (2001)35 Malaysia |

1 lesbian couple and 2 gay couples | Interview | Social Stigma; Sexual Identity | Gay and lesbian are not socially accepted. They feel societal pressure to hide their sexuality and to marry the opposite sex. |

| Chong (2013)53 China |

306 LGB who had been in a same-sex relationship in the past 2 years for at least 2 weeks: 192 LB women | Web-Based Questionnaire | Intimate Partner Violence | Relationship conflict and poor anger management were risk factors for psychological/physical perpetration of intimate partner violence. |

| Chow (2010)37 China |

224 WSW from Mainland China and 234 WSW from Hong Kong | Questionnaire | Social Stigma; Sexual Identity | Shame is related to internalized heterosexism and devaluation of lesbian identity. Lesbians are unlikely to come out to their parents, but are more willing to disclose to friends. |

| Ding (2013)54 China |

276 nightclub drug users | Questionnaire/Interview | Drug Use; Sexual Behavior | 20.7% self-identified as LGB. Self-identity of LGB is significantly associated with having multiple sex partners in past 30 days. |

| Hu (2013)38 China |

149 LGB age 15–24 years: 51 lesbians, 28 bisexual females, 38 females not sure | Questionnaire | Familial Pressure; Sexual Identity | Perceived parental attitude toward marriage and participants' endorsements of filial piety are associated with negative LGB identity. |

| Lo Kam (2006)39 China |

20 self-identified lesbians | Interview | Familial Pressure | Coping with family and marriage is biggest challenge for non-heterosexual women because of social stigma. |

| Mak (2010)55 China |

398 same-sex adults | Questionnaire | Intimate Partner Violence | 79.1% of participants have experienced IPV. 74.6% of participants received psychological aggression, 38.9% experienced physical assault, 23.3% experienced sexual coercion, and 10.0% were injured. |

| Ofreneo (2010)56 Philippines |

2 gay and 2 lesbian couples | Semi-structured Interview | Intimate Partner Violence | Physical violence as retributive justice ensued after the initiator of violence has claimed innocence or positioned partner as guilty. |

| Thaweesit (2004)44 Thailand |

80 female factory workers | Semi-structured Interview | Workplace Discrimination | Tom (female homosexual w/ masculine traits) face workplace discrimination and are likely denied of jobs for their masculine appearance. |

| Wong (2012)57 Malaysia |

15 Pengkids (masculine-looking Malay-Muslim lesbians) | Interview | Sexual/Gender Identity | Many Pengkids have histories of drug use. Their girlfriends were usually involved with both men and women. Pengkid identity allows freedom from and transgression of feminine and heterosexual social expectations. |

| Zheng (2011)58 China |

554 heterosexual men/women and 435 homosexual men/women, age 16+ years | Web-Based Questionnaire | Sexual Identity; Personality | Heterosexual women are more feminine and reported lower emotional stability than homosexual women. |

| Europe and Central Asia | ||||

| Beres-Deak (2011)36 Hungary |

21 same-sex couples: 11 male and 10 female | Semi-Structured Interview | Family Relations | Women in same-sex relationships postpone coming out to their family until they can no longer conceal their sexual orientation, such as when one moves in with their same-sex partner. |

| Bilgehan Ozturk (2011)42 Turkey |

20 LGBs: 7 lesbians, 11 gay males, 2 bisexual males | Unstructured Interview | Workplace Discrimination | Most participants were not “out” for fear of becoming a victim of verbal abuse or violence (such as honor killings). Those who are out faced severe discrimination and possibility of job termination. |

| Dioli (2011)59 Serbia; Bosnia and Herzegovina |

30 activists from feminist, LGBT, and queer organizations | Interview | Human Rights; Transnational Organizations | Activists are concerned that international organizations regard local counterparts solely as implementers of a project rather than involving local partners in planning process. Southeast Europe activists adopt a human-rights framework in their advocacy work, which causes conflict when cooperating with international organizations that adopt Western identity politics. |

| Turan (2006)60 Turkey |

161 LGBs | Questionnaire | Demographics | 14.0% self-identified lesbians; 36.4% of lesbians have “come out” to their social environment. |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||||

| Barbosa (2009)46 Brazil |

30 WSW age 18–45 years | Ethnographic Observation; Interview | Healthcare Access | Low-income women, women with no prior sex with men, and women with masculine body language have greater difficulty accessing healthcare. Reporting of sexual practices and preferences at health services was an impediment to seek care. |

| Bertolin (2010)61 Brazil |

31 WSW | Structured Questionnaire | STI Risk | 68.0% of WSW did not know significance of HPV; 58.0% believed condoms provide full protection from STIs; 45.0% thought Pap smears should be performed twice a year. |

| De Souza (2006)62 Brazil |

Homosexuals: 42 men, 35 women Heterosexuals: 68 men, 72 women | Questionnaire | Psychology; Jealousy | Jealousy is no less intense among homosexual partners, compared to their heterosexual counterparts. |

| Ghorayeb (2011)63 Brazil |

Homosexuals: 31 women, 29 men Heterosexuals: 31 women, 28 men |

Interview | Mental health; Well-Being | Homosexuals have higher prevalence of mental disorders than heterosexual counterparts. |

| Maria Gomes de Carvalho (2013)47 Brazil |

7 lesbians, 2 bisexual women | Semi-structured interview | STI Risk; Healthcare Access | LBs feel uncomfortable disclosing sexual orientation to healthcare providers. LBs are aware of STIs but believe that STI risk is lower with sexual partners they know. |

| Mora (2010)64 Brazil |

18 self-identified LB ages 18–26 | Ethnographic Observation; Interview; Questionnaire | STI/HIV risk | Perception of STI and HIV risk was greatest when WSW were having sex with bisexual female partners and men. Self-identified lesbians have occasional sex with men. |

| White (2005)65 Jamaica |

33 MSM, WSW, people living with HIV/AIDS, health care workers | Focus Groups; Interview | Social Stigma | Anti-gay laws do not directly target homosexual/bisexual females; anti-gay aggression is mostly directed towards men. |

| South Asia | ||||

| Creating Resources for Empowerment in Action (2012)41 Bangladesh; India; Nepal |

1,600 disabled women, lesbian women, and female sex workers | Survey; Interview | Sexuality; Disability; Violence; Discrimination | Lesbian women reported experiencing violence, discrimination and social exclusion due to their sexual orientation. |

| Kuru-Utumpala (2013)66 Sri Lanka |

12 self-identified homosexual women/lesbians/queer/women-loving-women with non-feminine outward appearance | Semi-Structured Interview | Sexual Identity | All 12 reported tomboyish behavior as children. 66.7% of respondents usually prefer feminine women. More than 50% adhere to male masculinity norms but also include some femininity in their behavior. |

| Pathak (2010)43 Nepal |

15 lesbians | Semi-Structured Interview | Sexual Identity; Discrimination | Participants faced discrimination more often in public and administrative places than in religious places. Most do not disclose sexual identity for fear of social exclusion and discrimination from health care providers. |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||

| Arndt (2011)67 South Africa |

578 university students: 157 men, 421 women; 20 homosexual, 32 bisexual, 14 asexual | Questionnaire | Attitudes Toward Homosexuality/Bisexuality | Bisexual students had the least negative attitudes toward bisexual men and women compared to heterosexual, homosexual, and asexual students. |

| Butler (2008)68 South Africa |

18 LGB youth age 16–21 years | Semi-Structured Interview | Psychology; Coping | LGB youth use defense mechanisms during their coming out process to reduce stress. |

| Ehlers (2001) Botswana45 |

47 self-identified LGBs aged 15+ years: 5 females | Questionnaire | Psychology; Well-being | Only 1 female reported positive well-being. LGBs experience distress due to anti-gay laws, social isolation, and unmet healthcare needs. |

| Gibson (2012)40 South Africa |

8 female university students | Semi-Structured Interview | Sexual Identity | Desire for familial belonging affect timing of “coming out” to family members; More White lesbians voiced feeling of acceptance at the university than Black lesbians. |

| Miller (2013)69 South Africa |

830 adolescents age 14–19 years: 29 identify as LGB | Cross-Sectional Survey | HIV | 13.8% (3 females and 1 male) of self-identified LGBs reported living with HIV, versus 2.3% (8/350) of self-identified heterosexual youth. |

| Morgan (2003)70 South Africa |

7 same-sex oriented female sangomas (traditional healers) | Semi-Structured Interview | Sexual Identity | Sangomas have fluid gender and sexual identities depending on the presence of ancestral spirits. They attribute their same-sex desires to a combination of personal agency and presence of dominant male ancestral spirits. |

| Nkala (2011)71 South Africa |

294 adolescents age 14–19 years: 87 identify as LGB | Survey | HIV Knowledge | 50.0% of adolescents ever had an HIV test. 21.8% believed HIV originated in primates; others were unsure or believed other theories. |

LGB, lesbian, gay, bisexual.

Discussion

We sought to compile articles published since 1980 on WSW living in LMICs, assess research trends, and synthesize the data related to sexual health. To our knowledge, ours is the first systematic review of health outcomes for WSW living in LMICs. Based on the evidence gathered, we highlight the importance of research related to sexual risk behavior, substance abuse, and related outcomes in this population and make recommendations for future research and practice.

Like the MSM population, WSW living in developing countries are often difficult to recruit for research because of criminalization (where this exists), social stigma, fear of discrimination, and desire to hide their sexual identity. Thus, most of the studies in our analysis relied on snowball sampling to recruit participants. As a result, many of them have small sample sizes, limiting the generalizability of their findings. Despite this, our review is consistent with existing literature on risk behaviors of WSW in high-income countries.

WSW engage in sexual behaviors involving exchange of bodily fluids that could transmit HIV or STIs to female partners. These behaviors include oral sex, receptive vaginal or anal activity with fingers, genital-to-genital rubbing, and sharing of sex toys.72 While protective barriers such as gloves, condoms, and dental dams might potentially limit exchange of bodily fluids, there are no standards for safer sex among WSW. In these cited surveys from around the world, WSW report infrequent use of these potentially protective measures with female partners.17,20,27,73 This may be due, in part, to their perceived low risk for contracting STIs, including HIV,73 despite evidence demonstrating that some WSW may have higher STI rates than heterosexual women.5,74 Up to one third of WSW participants had at least one STI in the studies we identified.14,18,20 Although HIV prevalence among WSW in two small Chinese studies was 0%,75 HIV prevalence is likely higher in many areas, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the study with the largest sample size of African WSW, nearly 10% of participants reported living with HIV.26

WSW also reported inconsistent use of protection during sex with men: only 48.0%–54.2% of participants had used a condom during the last sexual encounter with a male partner.14,17,27 Although some WSW self-identify as lesbians, the majority of WSW had had sex with men.3,76 Moreover, more WSW report sex with MSM and IDU than do heterosexual women.4,20 Theoretically, WSW who have MSM and IDU sexual partners could serve as a bridge between very high-risk (MSM and IDU) and lower risk (women who only have sex with women) populations.

Our analysis also showed that 7.6%–18.6% of WSW had had transactional sex.16,20,26 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Baral and colleagues found that the burden of HIV remains disproportionately high among female sex workers (FSW) in LMICs, with an overall HIV prevalence of 11.8%.77 WSW who engage in transactional sex could act as a bridging population and increase overall HIV risk in the WSW population.

Forced sex can also put WSW at risk for HIV and STIs. Studies from Thailand and Sub-Saharan Africa reported that nearly one-third of WSW participants had experienced coerced or forced sex.16,25,26 In a global literature review, Stockman and colleagues documented that 5.3%–46.0% of women in LMICs had experienced forced sexual initiation, which was associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV/STI prevalence to a greater extent in LMICs than in the United States.78 In African countries, masculine-appearing women and women perceived to be lesbians have been targeted for corrective rape to “cure” their homosexuality.79

Our analysis has several implications. First, interactions with health care practitioners are an opportunity for WSW to receive tailored sexual health education. However, many WSW in LMICs28,45–47 and in the United States80,81 have difficulties accessing services and communicating their needs to providers. Providers in LMICs, no less than in other settings, should be trained to obtain a complete sexual history, provide relevant sexual health education, screen for alcohol and other substance abuse problems that increase HIV/STI risk, and encourage WSW to have routine gynecological visits with HIV/STI screening.

Second, global HIV surveillance efforts should be expanded to include WSW. HIV prevention researchers should collect data on sexual orientation and disaggregate results for WSW in their analyses. Future research on WSW in LMICs should use population-based sampling methods to assess HIV and STI prevalence, risk behaviors, risk perception, sexual partner networks (including concurrency), and the associations of substance use, transactional sex, and forced sex with HIV risk among WSW. While current-funding mechanisms may not provide a strong base for WSW-specific research, researchers could integrate research on WSW health and behavior into HIV prevention and reproductive health research for the general population in LMICs. In LMICs that criminalize homosexuality, donors and researchers could help local organizations to advance the sexual health rights of WSW as part of the efforts aimed at women in general.

Our analysis has limitations. To avoid missing studies, we included several with small sample sizes; results from these studies may not be generalizable. We excluded studies that focused on transgendered individuals because they are a unique population with health needs that differ from WSW; additional work is needed to address this group. We searched three major electronic databases, but excluded conference proceedings due to lack of detail. Due to extreme heterogeneity of these studies and very limited biologic testing, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis of sexual risk behavior or of HIV, STIs, or any other health indicator among WSW. Finally, although we did not discuss the evidence related to mental health and intimate partner violence in this population, we recognize that these are important issues that researchers should explore.

Conclusion

WSW living in LMICs engage in a range of behaviors that can increase their risk of HIV and STI transmission to and from both female and male partners. Despite emerging evidence of these risks, WSW have been largely left out of the global HIV prevention discourse. Researchers, health care providers, international donors, human rights advocates, and governments should work together to address the sexual health needs of this understudied population.

Contributors

SMG and JMM conceptualized the review and provided overall guidance. SAT compiled literature, extracted data, and wrote the first draft. All authors reviewed articles and edited the review.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Juan Nie (University of Washington Master of Public Health student), Carly Rintisch (Modo Group), and Dr. Ileana Marin (University of Washington Ellison Center for Russian, Eastern European and Central Asian Studies) for reviewing and summarizing the key points of foreign language articles in Chinese, Portuguese, and Romanian. We appreciated the help from Daren Wade, Julie Brunett, and Jennifer Tee of the University of Washington's Department of Global Health for connecting us with foreign language speakers to review the articles. SAT and JMM were supported by CDC Cooperative Agreement #PS5U62PS003298. SMG was supported by NIMH 1R34MH099946. Our funding sources did not have a role in the development of this Review.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Richardson D: The social construction of immunity: HIV risk perception and prevention among lesbians and bisexual women. Cult Health Sex 2000;2:33–49 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Power J, McNair R, Carr S: Absent sexual scripts: Lesbian and bisexual women's knowledge, attitudes and action regarding safer sex and sexual health information. Cultur Health Sex 2009;11:67–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamant AL, Schuster MA, McGuigan K, Lever J: Lesbians' sexual history with men: Implications for taking a sexual history. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2730–2736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koh AS, Gómez CA, Shade S, Rowley E: Sexual risk factors among self-identified lesbians, bisexual women, and heterosexual women accessing primary care settings. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:563–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh D, Fine DN, Marrazzo JM: Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women reporting sexual activity with women screened in Family Planning Clinics in the Pacific Northwest, 1997 to 2005. Am J Public Health 2011;101:128–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrazzo JM, Stine K, Koutsky LA: Genital human papillomavirus infection in women who have sex with women: A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:770–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Markowitz LE: Women who have sex with women in the United States: Prevalence, sexual behavior and prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection-results from national health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2006. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos-Outcalt D, Hurwitz S: Female-to-female transmission of syphilis: a case report. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2002; 29(2):119–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan SK, Thornton LR, Chronister KJ, et al. : Likely female-to-female sexual transmission of HIV–Texas, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:209–212 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, Beyrer C: Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: A systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The World Bank Group: Country and lending groups, 2014. Available at http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups (accessed October24, 2014)

- 12.Lau JT, Kim JH, Tsui HY: Prevalence and factors of sexual problems in Chinese males and females having sex with the same-sex partner in Hong Kong: A population-based study. Int J Impot Res 2006;18:130–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieh-Mak F, O'Hoy KM, Luk SL: Lesbianism in the Chinese of Hong Kong. Arch Sex Behav 1983;12:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu YJ, Wang XF, Song L, et al. : [The sexual behavior characteristics and STD infection status of women who have sex with women in Beijing]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine] 2012;46:627–630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel SA, Bangorn S, Aramrattana A, et al. : Elevated alcohol and sexual risk behaviors among young Thai lesbian/bisexual women. Drug and Alcohol Depend 2013;127:53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Griensven F, Kilmarx PH, Jeeyapant S, et al. : The prevalence of bisexual and homosexual orientation and related health risks among adolescents in northern Thailand. Arch Sex Behav 2004;33:137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Norris JL, Liu Y, et al. : Risk behaviors for reproductive tract infection in women who have sex with women in Beijing, China. PloS One 2012;7:e40114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang XF, Norris JL, Liu YJ, et al. : Health-related attitudes and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections of Chinese women who have sex with women. Chin Med J 2012;125:2819–2825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitam FL, Daskalos C, Sobolewski CG, Padilla P: The emergence of lesbian sexuality and identity cross-culturally: Brazil, Peru, the Philippines, and the United States. Arch Sex Behav 1998;27:31–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto VM, Tancredi MV, Tancredi Neto A, Buchalla CM: Sexually transmitted disease/HIV risk behaviour among women who have sex with women. AIDS 2005;19:S64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cáceres CF, Marin BV, Hudes ES, et al. : Young people and the structure of sexual risks in Lima. AIDS 1997;11:S67–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz-Hernández L, García Torres MI: [Effects of violence and discrimination on the mental health of bisexuals, lesbians, and gays in Mexico City]. Cad Saude Publica 2005;21:913–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortiz-Hernández L, Granados-Cosme JA: Violence against bisexuals, gays and lesbians in Mexico City. J Homosex 2006;50:113–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ephrem B, White AM: Agency and expression despite repression: A comparative study of five Ethiopian lesbians. J Lesbian Stud 2011;15:226–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matebeni Z, Reddy V, Sandfort T, Southey-Swartz I: “I thought we are safe”: Southern African lesbians' experiences of living with HIV. Cult Health Sex 2013;15:34–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandfort TG, Baumann LR, Matebeni Z, et al. : Forced sexual experiences as risk factor for self-reported HIV infection among southern African lesbian and bisexual women. PloS One 2013;8:e53552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poteat T, Logie C, Adams D, et al. : Sexual practices, identities and health among women who have sex with women in Lesotho - a mixed-methods study. Cult Health Sex 2014;16:120–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graziano KJ: Oppression and resiliency in a post-apartheid South Africa: Unheard voices of Black gay men and lesbians. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 2004;10:302–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook RL, Clark DB: Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:156–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman SR, Ompad DC, Maslow C, et al. : HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, and high-risk sexual and injection networks among young women injectors who have sex with women. Am J Public Health 2003;93:902–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, et al. : Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci 2007;8:141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pithey A, Parry C: Descriptive systematic review of Sub-Saharan African studies on the association between alcohol use and HIV infection. SAHARA J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance/SAHARA, Human Sciences Research Council 2009;6:155–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardoso MN, Caiaffa WT, Mingoti SA: AIDS incidence and mortality in injecting drug users: The AjUDE-Brasil II Project. Cad Saude Publica 2006;22:827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortiz-Hernandez L, Gomez Tello BL, Valdes J: The association of sexual orientation with self-rated health, and cigarette and alcohol use in Mexican adolescents and youths. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:85–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baba I: Gay and lesbian couples in Malaysia. J Homosex 2001;40):143–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Béres-Deák R: “I was a dark horse in the eyes of her family”: The relationship of cohabiting female couples and their families in Hungary. J Lesbian Stud 2011;15:337–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chow PKY, Cheng ST: Shame, internalized heterosexism, lesbian identity, and coming out to others: A comparative study of lesbians in mainland China and Hong Kong. J Couns Psychol 2010;57:92–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu X, Wang Y: LGB identity among young Chinese: The influence of traditional culture. J Homosex 2013;60:667–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo Kam LY: Noras on the road: Family and marriage of lesbian women in Shanghai. J Lesbian Stud 2006;10:87–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson A, Macleod C: (Dis)allowances of lesbians' sexual identities: Lesbian identity construction in racialised, classed, familial, and institutional spaces. Fem Psychol 2012;22:462–481 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creating Resources for Empowerment in Action (CREA): Count me IN!: Research report on violence against disabled, lesbian, and sex-working women in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Reprod Health Matter 2012;20:198–206 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozturk MB: Sexual orientation discrimination: Exploring the experiences of lesbian, gay and bisexual employees in Turkey. Hum Relat 2011;64:1099–1118 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pathak R: Gender identity: Challenges to accessing social and health care services for lesbians in Nepal. GJHS 2010;2:207–214 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thaweesit S: The fluidity of Thai women's gendered and sexual subjectivities. Cult Health Sex 2004;6:205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehlers VJ, Zuyderduin A, Oosthuizen MJ: The well-being of gays, lesbians and bisexuals in Botswana. JAN 2001;35:848–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbosa RM, Facchini R: [Access to sexual health care for women who have sex with women in Sao Paulo, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica 2009;25:S291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomes de Carvalho PM, Martins Nóbrega BS, Lima Rodrigues J, et al. : Prevention of sexually transmitted diseases by homosexual and bisexual women: A descriptive study. Online Braz J Nurs 2013;12:931–941 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tangmunkongvorakul A, Banwell C, Carmichael G, et al. : Sexual identities and lifestyles among non-heterosexual urban Chiang Mai youth: Implications for health. Cult Health Sex 2010;12:827–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barbosa RM, Koyama MAH: [Women who have sex with women: Estimates for Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica 2006;22:1511–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traeen B, Martinussen M, Vittersø J, Saini S: Sexual orientation and quality of life among university students from Cuba, Norway, India, and South Africa. J Homosex 2009;56:655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dingeta T, Oljira L, Assefa N: Patterns of sexual risk behavior among undergraduate university students in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J 2012;12:33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicholas LJ: The association between religiosity, sexual fantasy, participation in sexual acts, sexual enjoyment, exposure, and reaction to sexual materials among black South Africans. J Sex Marital Ther 2004;30:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chong ES, Mak WW, Kwong MM: Risk and protective factors of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. J Interpers Violence 2013;28:1476–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding Y, He N, Zhu W, Detels R: Sexual risk behaviors among club drug users in Shanghai, China: Prevalence and correlates. AIDS Behav 2013;17:2439–2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mak WW, Chong ES, Kwong MM: Prevalence of same-sex intimate partner violence in Hong Kong. Public Health 2010;124:149–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ofreneo MAP, Montiel CJ: Positioning theory as a discursive approach to understanding same-sex intimate violence. Asian J Soc Psychol 2010;13:247–259 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong Y: Islam, sexuality, and the marginal positioning of Pengkids and their girlfriends in Malaysia. J Lesbian Stud 2012;16:435–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng L, Lippa RA, Zheng Y: Sex and sexual orientation differences in personality in China. Arch Sex Behav 2011;40:533–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dioli I: From globalization to Europeanization-and then? Transnational influences in lesbian activism of the Western Balkans. J Lesbian Stud 2011;15:311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turan N, Dokgoz H, Birincioglu I, Oghan F: Evaluation of demographic findings of people with different sexual orientation in Istanbul, Turkey. Neurol Psychiat BR 2006;13:181–187 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertolin DC, Ribeiro RdCHM, Cesarino CB, et al. : Knowledge of women who have sex with women about human papillomavirus [Portuguese]. Cogitare Enfermagem 2010;15:730–735 [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Souza AAL, Verderane MP, Taira JT, Otta E: Emotional and sexual jealousy as a function of sex and sexual orientation in a Brazilian sample. Psychol Rep 2006;98:529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghorayeb DB, Dalgalarrondo P: Homosexuality: Mental health and quality of life in a Brazilian socio-cultural context. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2011; 57(5): 496–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mora C, Monteiro S: Vulnerability to STIs/HIV: Sociability and the life trajectories of young women who have sex with women in Rio de Janeiro. Cult Health Sex 2010;12:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White RC, Carr R: Homosexuality and HIV/AIDS stigma in Jamaica. Cult Health Sex 2005;7:347–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuru-Utumpala J: Butching it up: An analysis of same-sex female masculinity in Sri Lanka. Cult Health Sex 2013;15:S153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arndt M, de Bruin K: Measurement of attitudes toward bisexual men and women among South African university students: The validation of an instrument. J Homosex 2011;58:497–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butler AH, Astbury G: The use of defence mechanisms as precursors to coming out in post-apartheid South Africa: A gay and lesbian youth perspective. J Homosex 2008;55:223–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller CL, Dietrich J, Nkala B, et al. : Implications for HIV prevention: Lesbian, gay and bisexual adolescents in urban South Africa are at increased risk of living with HIV. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:e263–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan R, Reid G: “I've got two men and one woman”: Ancestors, sexuality and identity among same-sex identified women traditional healers in South Africa. Cult Health Sex 2003;5:375–391 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nkala B, Dietrich J, Miller C, et al. : Knowledge on the origin of HIV/AIDS among South African adolescents. CJIDMM 2011;22:77B–78B [Google Scholar]

- 72.Women's Institute: HIV Risk for Lesbians, Bisexuals & Other Women Who Have Sex With Women. New York: Gay Men's Health Crisis, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marrazzo JM, Coffey P, Bingham A: Sexual practices, risk perception and knowledge of sexually transmitted disease risk among lesbian and bisexual women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2005;37:6–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McNair R: Risks and prevention of sexually transmissible infections among women who have sex with women. Sex Health 2005;2:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zeng CE, Huang SQ, Tian LG, et al. : [AIDS relative risk behaviors among women who have sex with women]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2007;28:294–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bailey JV, Farquhar C, Owen C, Mangtani P: Sexually transmitted infections in women who have sex with women. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:244–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. : Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:538–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC: Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: A global review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2013;17:832–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mkhize N, Moletsane R, Reddy V, Bennett J: The Country We Want To Live In: Hate Crimes and Homophobia In the Lives of Black Lesbian South Africans. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heck JE, Sell RL, Sheinfeld Gorin SS: Health care access among individuals involved in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1111–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kurth AE, Martin DP, Golden MR, et al. : A comparison between audio computer-assisted self-interviews and clinician interviews for obtaining the sexual history. Sex Transm Dis 2004;31:719–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]