Abstract

The three essential branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), leucine, isoleucine and valine, share the first enzymatic steps in their metabolic pathways, including a reversible transamination followed by an irreversible oxidative decarboxylation to coenzyme-A derivatives. The respective oxidative pathways subsequently diverge and at the final steps yield acetyl- and/or propionyl-CoA that enter the Krebs cycle. Many disorders in these pathways are diagnosed through expanded newborn screening by tandem mass spectrometry. Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is the only disorder of the group that is associated with elevated body fluid levels of the BCAAs. Due to the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation step distal enzymatic blocks in the pathways do not result in the accumulation of amino acids, but rather to CoA-activated small carboxylic acids identified by gas chromatography mass spectrometry analysis of urine and are therefore classified as organic acidurias. Disorders in these pathways can present with a neonatal onset severe-, or chronic intermittent- or progressive forms. Metabolic instability and increased morbidity and mortality are shared between inborn errors in the BCAA pathways, while treatment options remain limited, comprised mainly of dietary management and in some cases solid organ transplantation.

Keywords: Branched-chain, amino acid, organic acidemia, maple syrup urine disease, isovaleric, methylmalonic, propionic, mitochondria

1. Clinical presentations, genetics and pathology

1.1. Overview of branched chain amino acids metabolism and regulation

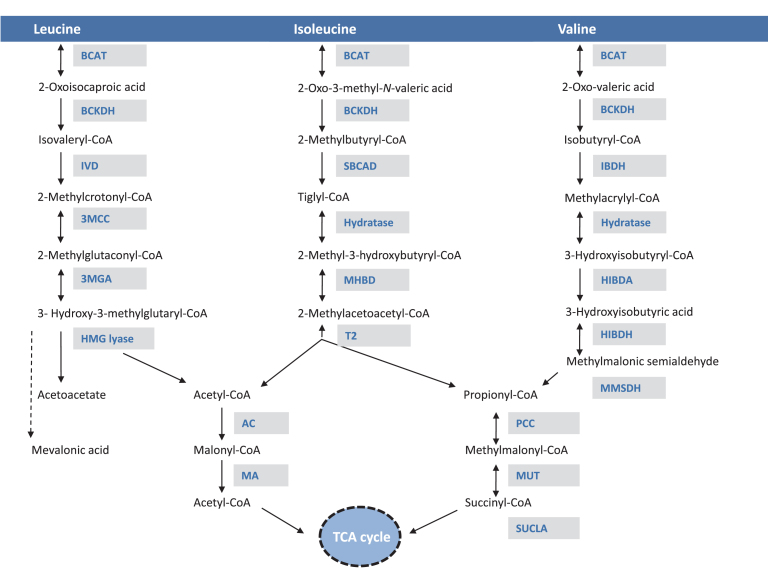

Branched chain amino acids (BCAAs), leucine, isoleucine and valine, are three of the nine essential amino acids and account for 35–40% of the dietary indispensable amino acids in body protein and 14% of the total amino acids in skeletal muscle. They share common membrane transport systems and enzymes for their transamination and irreversible oxidation. A detailed biochemical pathway is provided in Fig. 1. They can be glucogenic (valine), ketogenic (leucine and isoleucine) or both (isoleucine), since their end products, succinyl-CoA and/or acetyl-CoA can enter the Krebs cycle for energy generation and gluconeogenesis or act as precursors for lipogenesis and ketone body production through acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate [1].

Fig.1.

Biochemical pathway of branched chain amino acid metabolism. The enzymatic steps for the metabolism of leucine, isoleucine and valine are provided. Shaded boxes include the acronyms of the enzymes. Abbreviations: BCAT = branched chain amino acid aminotransferase; BCKDH: branched chain α-keto-acid dehydrogenase; IVD: isovaleryl CoA dehydrogenase; 3-MCC = 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase; 3-MGA = 3-methylglutaconic-CoA hydratase; HMGL = 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-CoA lyase; SBCAD = methylbutyryl CoA dehydrogenase; MHBD = 2-methyl-3-hydroxyisobutyric dehydrogenase; BKT = mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase; IBDH = isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase; HIBDA: 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA deacylase (hydrolase); HIBDH: 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase; MMSDH = methylmalonic semialdehyde dehydrogenase; PCC: propionyl-CoA carboxylase; MUT: methylmalonyl-CoA mutase; SUCLA: succinyl-CoA ligase; TCA cycle: tricarboxylic acid cycle (Krebs).

BCAAs first undergo a reversible transamination by BCAA aminotransferases (BCAT), a pyridoxal-phosphate dependent enzyme with cytosolic (BCATc) and mitochondrial (BCATm) isoforms, followed by the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation and coupled thioesterification of the respective ketoacids by the single mitochondrial branched chain keto-acid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex to form coenzyme A derivatives. The BCKDH multienzyme complex consists of E1, a thiamine pyrophosphate-dependent decarboxylase; E2, a lipoate-dependent transacylase; and E3, a dehydrogenase, the subunit of which is shared by pyruvate and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenases. The oxidation of BCAAs and branched chain keto-acids (BCKAs) is tightly regulated primarily at the BCKD step [1–3], which commits BCAAs to oxidative metabolism.

The next step in the BCAA metabolic pathway is dehydrogenation of the activated ketoacid by either isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (leucine metabolism) or the α-methyl-branched chain dehydrogenase (isoleucine and valine metabolism). After these first three steps, the metabolism of each of the BCAAs diverges and eventually yields acetyl-CoA and/or propionyl-CoA. Terminal valine metabolism is unique because a free acid, 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid forms after the hydrolysis of the corresponding thioester. 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid is dehydrogenated, then reacylated to complete metabolism.

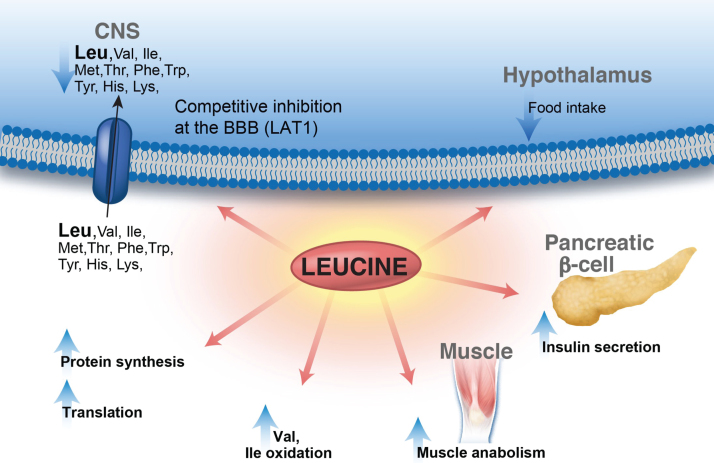

Similar to other large neutral amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, leucine, methionine, isoleucine, tyrosine, histidine, valine, and threonine), they are transported into the brain and other organs primarily by the L1-neutral amino acid transporter (LAT1). Therefore, the relative concentrations of each amino acid and their competition for the same transporter affect brain amino acid uptake and the downstream synthesis of various neurotransmitters [4], an effect with significant pathophysiological and therapeutic implications for the diseases in the BCAA metabolic pathway. Moreover, leucine plays a central role in metabolism and participates in numerous signaling pathways, as summarized in Fig. 2. It is a potent stimulator of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and downstream targets that enhance translation elongation and protein synthesis [5–7]. In addition, leucine may act as an inhibitor of muscle protein breakdown, via interactions with the ubiquitin-proteasome and the autophagy-lysosome system [8]. Furthermore, leucine stimulates insulin secretion from the pancreatic β-cell serving as metabolic fuel as well as an allosteric activator of glutamate dehydrogenase [9–13]. Lastly, it also plays a role in central nervous system food intake regulatory circuits and feeding behavior [14, 15].

Fig.2.

Leucine metabolic effects in multiple organ systems. Leucine displays a multitude of effects in various organs: enhances protein synthesis, inhibits muscle protein breakdown, stimulates insulin secretion and plays a role in central nervous system food intake regulatory circuits and feeding behavior. Leucine is transported via the large neutral amino acid transporter LAT1 at the blood–brain barrier, among other transporters, and can compete with other large neutral amino acids for uptake/transport affecting neurotransmitter biosynthesis. Lastly, leucine-derived α-ketoisocaproate is a potent inhibitor of the branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase-kinase resulting in activation of branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase and increased BCAA (valine and isoleucine) oxidation.

MSUD is the only one of the BCAA disorders that can be detected by plasma amino acid analysis, as it is caused by a defect in the second step of BCAA metabolism, resulting in massive plasma elevations of primarily leucine, but also isoleucine and valine, as well as their BCKAs, α-ketoisocaproic (KIC), α-keto-β-methylvaleric (KMV) and α-ketoisovaleric acid (KIV), respectively. For the rest of the BCAA metabolism disorders, the defect lies distal to the non-reversible BCKD reaction, and therefore amino acids and 2-oxo-acids do not accumulate. Each of the blocks in the subsequent steps leads to the accumulation of intermediates in the respective pathway, resulting in unique, identifiable patterns for each enzyme defect. Only few relatively more common inborn errors, such as MSUD, IVA, 3MCC, 3MGA, PA and MMA, will be described in some detail, while descriptions of the clinical presentation, outcomes and treatment for all other disorders are listed briefly in Table 1.

Table 1.

Disorders of the branched chain amino acid metabolic pathway. Clinical presentation, outcomes and therapeutic approaches

| Disorder | Clinical presentation | Outcome | Treatment |

| Maple syrup urine disease | Classic: Lethargy/irritability, progressive encephalopathy, opisthotonus, coma | Intellectual disability depending on age at diagnosis and metabolic control | Leucine restriction, high-caloric BCAA-free formulas |

| Intermediate: Metabolic encephalopathy with stress, anorexia, growth failure | ADHD, anxiety, depression | Valine and isoleucine, glutamine/alanine supplementation (as needed) | |

| Intermittent: Normal early development, episodic crises associated with stress | Transient encephalopathy, | Thiamine (according to genotype) | |

| Thiamine responsive: similar to intermediate, improved biochemical profile with thiamine | hyperactivity, focal dystonia, choreoathetosis, ataxia | Multivitamin, minerals | |

| Type III, E3 deficient: Leigh-type encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, often lethal | Amino acid or other nutritional deficiencies | Liver transplantation (classic patients) | |

| Osteoporosis | |||

| Isovaleric acidemia | Acute presentation: | Failure to thrive | Leucine restriction |

| Metabolic ketoacidosis | Pancytopenia with acidotic episodes | Glycine supplementation | |

| Hyperammonemia | Myeloproliferative syndrome | L-Carnitine | |

| Bone marrow failure | Pancreatitis | Multivitamin, minerals | |

| Poor feeding, vomiting | Fanconi syndrome | ||

| Encephalopathy | Cardiac arrhythmias | ||

| “Sweaty feet” odor | Intellectual disability | ||

| Chronic intermittent presentation: | |||

| Exacerbations during periods of stress | |||

| Asymptomatic, common missense mutation 932C>T (A282V), with only partial reduction in IVD activity | |||

| 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency | Acute hypoglycemia, episodic metabolic acidosis, severe neurological symptoms in neonates (seizures, hypotonia, coma, developmental delay) | Completely asymptomatic adults (i.e. affected mothers detected through newborn screening) | Fasting avoidance |

| L-Carnitine | |||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type I | Intellectual disability, seizures, hepatomegaly, hypotonia | Optic atrophy, dysarthria, ataxia, | Leucine restriction |

| adult onset progressive leukoencephalopathy | L-Carnitine | ||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type II: | X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy, cyclic neutropenia, skeletal myopathy, and mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction | Growth retardation | |

| Barth syndrome | |||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type III: | Infantile optic atrophy, extrapyramidal signs, spasticity, ataxia, dysarthria, | ||

| Costeff optic atrophy | |||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type IV: “unclassified” | Encephalomyopathic, hepatocerebral, cardiomyopathic, myopathic forms with mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction | Cataracts, cardiomyopathy, deafness, lactic acidosis | |

| Facial dysmorphism | |||

| Intellectual disability | |||

| 3-Hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency | Non-ketotic hypoglycemia, metabolic acidosis | Hepatomegaly | Leucine and fat restriction |

| Sensitivity to dietary leucine | Early death | L-Carnitine | |

| 2-methyl-3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria | Static or progressive encephalopathy, | Seizures, optic atrophy, retinopathy, deafness, ataxia, di or tetraplegia, cardiomyopathy, facial dysmorphism | Isoleucine restriction |

| Few cases with acute metabolic decompensation | Antioxidant therapy | ||

| Milder phenotype in female patients | |||

| Methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase def. | Acute neonatal acidosis, MRI abnormalities | Intellectual disability, seizures in few symptomatic patients | Protein restriction |

| Hmong decent: transient hypotonia, or mostly completely asymptomatic | L-Carnitine | ||

| No treatment for Hmong patients | |||

| Mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase deficiency | Acute intermittent ketoacidosis, | Intellectual disability (small percent of patients) | Protein restriction |

| vomiting, coma | Mostly excellent outcome with dietary restriction | ||

| Isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | Anemia | Dilated cardiomyopathy | L-Carnitine |

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyryl- CoA deacylase deficiency | Congenital malformations, failure to thrive, developmental delay | Failure to thrive | Protein restriction |

| L-Carnitine | |||

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyric aciduria | Brain dysgenesis, multiple congenital malformations, acute ketoacidosis | Failure to thrive, | Protein restriction |

| Intellectual disability | L-Carnitine | ||

| Methylmalonic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency | Mild clinical symptoms | Asymptomatic | Protein restriction |

| L-Carnitine | |||

| Propionic acidemia | Recurrent ketoacidosis | Cardiomyopathy | Protein restriction |

| Hyperglycinemia, Hyperammonemia, Coma | Seizures | Valine, isoleucine, methionine, threonine free formula | |

| Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | Osteoporosis | L-Carnitine, (biotin) | |

| Hypotonia | Pancreatitis | Bicarbonate or citrate replacement | |

| Intellectual disability | Reduction of propiogenic gut flora (metronidazole or neomycin) | ||

| Liver transplantation | |||

| Methylmalonic acidemia | Recurrent ketoacidosis | Chronic renal failure | Protein restriction |

| Anorexia, failure to thrive | Renal tubular acidosis | Valine, isoleucine, methionine, threonine free formula | |

| Hepatomegaly | Recurrent pancreatitis | L-Carnitine | |

| Hyperglycinemia, Hyperammonemia, Coma | Osteoporosis | Bicarbonate or citrate replacement | |

| Pancytopenia | Metabolic stroke of the globus pallidus, spastic quadriparesis, choreoathetosis, dystonia | Reduction of propiogenic gut flora (metronidazole or neomycin) | |

| Hypotonia | Intellectual disability | OHCbl (cblA, mut- responsive patients) | |

| Bulls’ eye maculopathy and blindness (CblC disease) | Liver and/or kidney transplant (selected patients) | ||

| Seizures, intellectual disability | OHCbl and betaine (in cblC disease) |

1.2. Clinical presentation and disease pathophysiology

Detection of classic MSUD infants through newborn screening, comprising about 80% of the MSUD cases, has led to markedly improved treatment and neurological outcomes [16–18]. These early-detected patients have significantly lower concentrations of leucine at presentation and require less extracorporeal detoxification methods for initial treatment [18, 19]. It is possible though that newborn screening is missing milder variants of the disease, due to insufficient accumulation of toxic metabolites in the immediate neonatal period [20–22]. An increased ratio of Leu/Phe or Leu/Ala and second tier testing for allo-isoleucine have been proposed to increase sensitivity, but some of the intermediate and intermittent variants of MSUD are expected to escape detection, and serve to emphasize the limitations of expanded newborn screening in the diagnosis of all affecteds. Patients with IVA or beta-ketothiolase deficiency can be detected by newborn screening prior to the onset of symptoms. For both disorders, early initiation of appropriate preventative therapy is expected to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

The situation is more complicated for the disorders in the propionate pathway, where newborn screening may help change the course in the milder patients with methylmalonic (mut- MMA, cobalamin A and B of isolated MMA or other types of combined MMA and homocystinuria of the cobalamin metabolism pathways) and propionic acidemia, but will have little effect on the most severe end of the spectrum. Early onset MMA and PA patients may present before screening is initiated in the immediate neonatal period with massive metabolite elevations and hyperammonemia resulting in demise or significant brain damage [23, 24]. Milder variants can be missed by newborn screening (false negatives) and efforts to develop methods that improve sensitivity and specificity, and integrate secondary markers into screening are underway [23, 25, 26].

In MSUD, the acute elevations of leucine and alpha-ketoisocaproic (αKIC) during intercurrent illness or other physiologic stress can cause severe acute metabolic encephalopathy and life-threatening cerebral edema, while chronic imbalance in the plasma levels of branched chain amino acids or protein over-restriction can lead to abnormal brain amino acid uptake with subsequent decreased myelin and neurotransmitter synthesis, causing further brain damage manifesting as chronic encephalopathy [27].

One hypothesis about the metabolism of leucine in the CNS is that leucine is transaminated in the astrocytes with α-ketoglutarate to α-ketoisocaproate and glutamate (Glu) via the mitochondrial BCAA transaminase reaction. Glutamate is subsequently converted to glutamine (Gln). The glutamine and α-ketoisocaproate (KIC) are released from the astrocytes and taken up in the neurons, where glutamine is converted to glutamate via phosphate-dependent glutaminase and α-ketoisocaproate is converted back to leucine and pyruvate by reversal of a cytosolic, in this case, BCAA transamination reaction, which is released and transported back to astrocytes, completing the so-called “leucine-glutamate cycle” [28–31]. Glutamine produced in glia is thus an essential precursor for the production of glutamate and GABA in the glutamate/GABAergic neurons.

In MSUD accumulation of branched-chain ketoacids (αKIC) within astrocytes and neurons may drive the reverse transamination toward α-ketoglutarate, resulting in increased αKG/glutamate ratios. This mechanism may underlie the deficiencies in cerebral glutamate, GABA, glutamine and aspartate that have been described in MSUD mouse models, as well as post-mortem brain of an infant with MSUD [32, 33]. This can also inhibit the malate/aspartate shuttle and result in an increased NADH/NAD+ ratio and impaired conversion of lactate to pyruvate [34], while high αKIC can inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH) resulting in Krebs cycle dysfunction [35, 36]. Defective oxidative phosphorylation is consistent with the high cerebral lactate levels observed in mice and humans during a metabolic crisis [32, 37].

High plasma levels of leucine result in competitive inhibition of the transport of other large neutral amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, isoleucine, valine, histidine, methionine, glutamine and threonine) across the blood-brain-barrier through their shared transporter (LAT1) [32, 38, 39]. Reduced levels of these essential amino acids inhibit protein and neurotransmitter synthesis, such as dopamine, serotonin, histamine and S-AdoMet, by limiting available precursors. Furthermore, deficiency of branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase impairs the production of ketone bodies from leucine that are essential for myelin synthesis. Combined with impaired protein synthesis this leads to severe dysmyelination [40, 41].

The illustration of the above mechanisms for the pathogenesis of acute and chronic brain injury in MSUD, and more importantly the implementation of that knowledge for the development of improved special metabolic formulas has yielded evidence-based guidelines for the management of this challenging condition. [16, 42, 43]

In contrast to the “intoxication” from excess leucine that plays a primary role in the pathogenesis of MSUD, the pathophysiology of each of the subsequent blocks in the BCAA metabolic pathways is less well characterized. Following the same paradigm, initial studies have focused on establishing the effects of the accumulation of toxic metabolites proximal to the block in many of the remaining disorders.

In methylmalonic acidemia, deficient activity of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase results in significant accumulation of methylmalonic acid, as well as of propionyl-CoA derived metabolites, such as 3-OH-propionate, 2-methylcitrate (product of the reaction of propionyl-CoA with oxaloacetate), and propionylglycine. Original studies focused on methylmalonic acid as the primary toxin, while subsequent studies suggested a key role for 3-OH-propionate and 2-methylcitrate for the various secondary biochemical alterations seen in MMA, including lactic acidosis, hyperglycinemia, hyperammonemia and hypoglycemia. It has been proposed that methylmalonyl-CoA a known inhibitor of pyruvate carboxylase, blocks the formation of oxaloacetate and phosphoenolpyruvate, an important substrate for gluconeogenesis in the liver, thereby increasing lipid catabolism resulting in hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis [44]; MMA has structural similarities to malonate, a known inhibitor of complex II of the respiratory chain (succinate dehydrogenase) and was shown to induce neuronal damage in vitro, as well as striatal lesions and seizures after intrastriatal administration in rats [45–49]; MMA was also shown to impair the transmitochondrial malate shuttle, another key step in gluconeogenesis, while the formation of methylcitrate disrupts the Krebs cycle, further contributing to the bioenergetic problems that manifest in MMA patients [50–52]. Propionyl-CoA accretion leads to a competitive inhibition of NAGS through the excess production of N-propionylglutamate, which in turn leads to the failure of CPS-1 to synthesize carbamoylphosphate, the first step in the urea cycle. Furthermore, Krebs cycle dysfunction caused by a) the decreased production of succinate due to the block and b) the depletion of oxaloacetate via the formation of 2-methylcitrate, may result in insufficient α-ketoglutarate (glutamate precursor) production and underlie the paradoxical hyperammonemia in the presence of low glutamate/glutamine that is observed in propionic and methylmalonic acidemia patients during metabolic crises [53–55]. Toxic metabolites also cause decreased H-protein activity resulting in inhibition of the glycine cleavage system and hyperglycinemia [56, 57].

Based on the “toxic metabolite” hypothesis, treatment with protein restriction to reduce the load of the offensive metabolites, as well as supplementation with glycine and /or carnitine to promote the synthesis and excretion of less toxic conjugates have been the mainstay of treatment for organic acidemias. Disorders for which such conjugation occurs more efficiently, like isovaleric acidemia, are therefore more biochemically responsive compared to defects like propionic or methylmalonic acidemia.

It seems though that deficiencies of intermediates downstream the metabolic block, as well as other secondary effects on associated pathways, like the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, may have a more significant role in the pathogenesis of these group of disorders. Moreover, although they are often grouped together and managed in a similar fashion, it is obvious that they are very different diseases with unique characteristics distinguishing even defects in nearby metabolic steps, such as propionic and methylmalonic acidemia. Despite the similarities in their clinical phenotypes, propionic and methylmalonic acidemia patients have notable differences, with propionic acidemia commonly associated with dilated cardiomyopathy and methylmalonic acidemia with early onset chronic kidney failure characterized by tubulointerstitial nephritis, both not as common occurrences in the other disorder. The difference in the renal phenotype has led to theories about more nephrotoxic effects of MMA compared to the other metabolic intermediates shared by the two diseases, or effects involving antagonism and inhibition of glutathione uptake by MMA via the dicaboxyclic acid transporter in the proximal tubules leading to glutathione depletion in the mitochondria and increased oxidative stress [58–60].

Intracellular CoA ester accumulation is considered a key pathogenetic mechanism for many of the organic acidemias and other disorders leading to Coenzyme A Sequestration, Toxicity or Redistribution (CASTOR) [61]. The high concentration of the acyl-CoA substrate of the respective enzyme and/or the subsequent depletion of acetyl- or CoA-SH species may lead to detrimental effects that are primarily localized inside the mitochondria and are characterized by cell-autonomy and organ specificity [61].

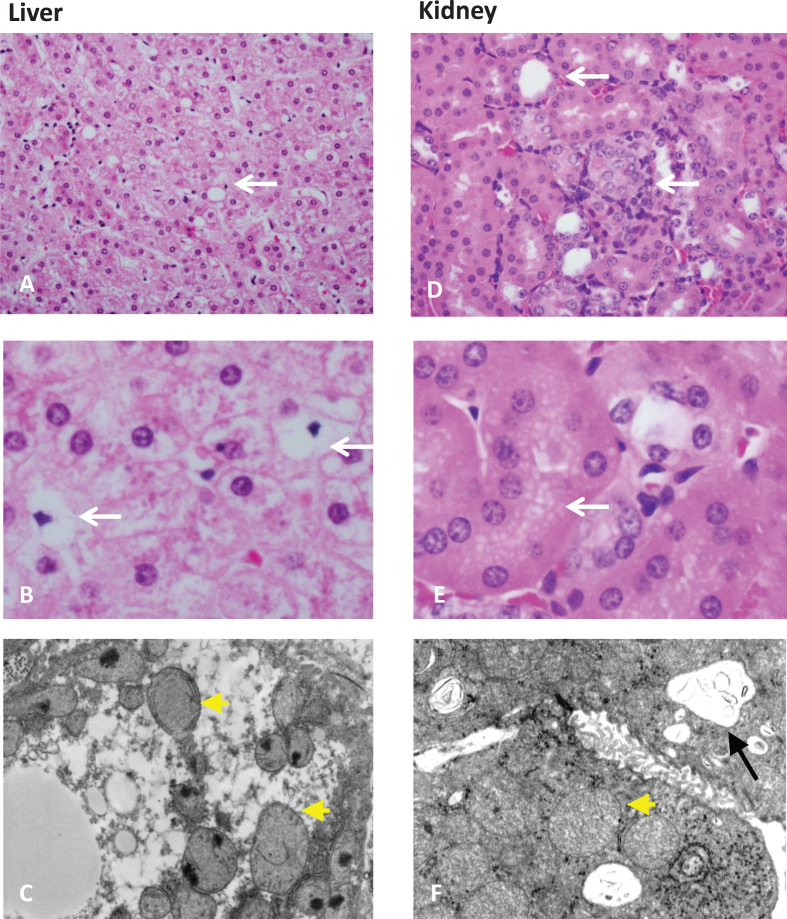

Studies in the Mut–/– knock-out and transgenic mice have established that cell-specific mitochondrial ultrastructural changes in the liver, the proximal tubules and the pancreas are present. Moreover, structural pathology was associated with decreased complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) enzymatic activity in the liver or the proximal tubules, and increased serum and/or urine markers of oxidative stress, both in mice and patients with MMA [60, 62, 63]. Subsequent studies confirmed increased oxidative stress (decreased glutathione levels in tissue and plasma levels), decreased OXPHOS enzymatic activities and mtDNA levels in patients with propionic or mut0 methylmalonic acidemia [64–68] and suggested a benefit of antioxidants or other mitochondria-targeted therapies in these patients (Fig. 3).

Fig.3.

Organ pathology in methylmalonic acidemia. Liver and kidney pathology from patients with mut0 methylmalonic acidemia are presented. Mild steatosis (A), lipid-laden stellate cells (white arrows) (B), with abnormal mitochondrial ultrastructure on transmission electron microscopy (EM) (pale mitochondria with absent or disorganized cristae, yellow arrowheads) are observed in patient livers. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with patchy interstitial chronic inflammation and tubular dilation (A), proximal tubule vacuolization (B) (white arrows), and enlarged mitochondria with disorganized cristae (yellow arrowhead) along with large remnant vacuoles that contained amorphous membranous inclusions (black arrow) on transmission EM are present in patient kidneys. Pathology was obtained from explanted organs after a combined liver and kidney transplantation procedure. Patients were enrolled in the clinical study: NCT00078078.

A similar picture, where secondary mitochondrial dysfunction is considered a key player in the pathophysiology of the disorder, is observed in the late defects of each of the three biochemical pathways of BCAA metabolism, including 3-MGA, MHBD, HIBCH and HIBA, suggesting a need to study these disorders outside the classic biochemical pathway of BCAA metabolism and rather focus on the intramitochondrial effects caused by the metabolic block. This would also move the treatment target away from dietary modifications and cofactors, and into mitochondria-targeted therapeutic approaches.

3-methylglutaconic aciduria caused by a deficiency in 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase, the enzyme converting 3-methylglutaconyl–CoA to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA in the last step of leucine metabolism, is the cause for 3-MGA type I. Four more types of 3-MGA have been described and are characterized by various degrees of mitochondrial dysfunction and are very remotely if at all linked to leucine metabolism [69, 70]. How mitochondrial dysfunction leads to increased 3-MGA is also unclear. Type I 3-MGA presents with non-specific symptoms, such as seizures and mental retardation in childhood, while recently an adult onset slowly progressive leukoencephalopathy was added to the clinical manifestations of this poorly defined entity [71]. 3-MGA type II or Barth syndrome is an X-linked recessive form of the disease, caused by mutations in the TAZ gene, encoding the protein taffazin. The pathognomonic finding in the disease is the abnormal cardiolipin profile in the patient’s cells. Clinical symptoms include cardiomyopathy, cyclic neutropenia, skeletal myopathy associated with mitochondrial OXPHOS dysfunction, increased 3-MGA excretion and low plasma cholesterol levels [72]. In these patients, 3-MGA excretion is not related to protein loading and it is thought to derive through a mevalonate shunt [73].

3-MGA type III or Costeff syndrome is characterized by infantile bilateral optic nerve atrophy, dysarthria, ataxia, extrapyramidal signs and is caused by mutations in OPA3, a protein localized in the outer membrane of the mitochondrion with critical role in mitochondrial fission and apoptosis [74]. 3-MGA type V is caused by mutations in a mitochondrial inner membrane translocase, DNAJC19, and presents as dilated cardiomyopathy with ataxia and in the Canadian Dariusleut Hutterite population, with testicular dysgenesis and growth failure. The remaining undefined cases with 3-MGA secretion are classified as type IV, and encompass a variety of disorders affecting mitochondrial function that have as a secondary marker increased 3-MGA. Mutations in POLG1, SUCLA2, DNAJC19, TMEM70, and mtDNA have all been described to cause elevated 3-MGA in the urine organic acid analysis.

2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MHBG) is a newly identified enzyme defect in the pathway of isoleucine metabolism, caused by an interesting enzyme with different substrates besides short-branched chain acyl-CoAs. These include 17β/ 3α-hydroxysteroids, compounds that play a role in sex hormone and neurosteroid metabolism, and is therefore also referred to as 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD10). It also shows affinity for amyloid-β-peptide and has the additional designation of endoplasmic reticulum-associated amyloid-β-binding protein (ERAB or ABAD) [75]. The disease presentation is that of a mitochondrial disorder with progressive neurodegeneration in the more severely affected males. More studies are needed to investigate the role of isoleucine restriction or antioxidant therapies in the management of these patients [76–78].

3-Hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase deficiency is a very rare disease described in three families in the literature. The first patient presented with congenital malformations, including vertebral abnormalities, tetralogy of Fallot, and agenesis of the cingulate gyrus and corpus callosum, poor feeding, gross motor delay, and neurological regression in infancy [79]. The subsequent cases displayed progressive infantile neurodegeneration as well as episodes of ketoacidosis and Leigh-like changes in the basal ganglia associated with a combined deficiency of multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes and pyruvate dehydrogenase in one set of sibs [80, 81]. This defect involves an exceptional step in valine metabolism where free acids are generated in contrast to all other intermediates that are CoA thioesters. Patients had increased secretion of S-2-carboxypropyl-cysteamine and S-2-carboxypropyl-cysteine, and persistently elevated C4-OH acylcarnitine, that led to the identification of mutations in the HIBCH gene [81]. Methacrylyl-CoA formed because of the block is a highly reactive compound that reacts with thiol groups, such as glutathione, cysteine or cysteamine, causing significant oxidative stress.

The last enzymatic steps in the valine degradation pathway convert 3-hydroxyisobutyrate to (S)-methylmalonic semialdehyde (MMSA) by 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase and (S)-methylmalonic semialdehyde to propionyl-CoA by the methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase enzyme (MMSDH). Thymine metabolism on the other hand generates (R)-aminoisobutyric acid (AIBA), which is then deaminated to (R)-methylmalonic semialdehyde. Both S- and R-methylmalonic semialdehyde are then handled by MMSDH, which catalyzes their oxidative decarboxylation to propionyl-CoA, suggesting that a single enzyme is involved in the catabolism of valine, thymine as well as uracil. Pathogenic mutations in the gene encoding MMSDH (ALDH6A1) have been identified in patients that displayed 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria [82], while others also manifested transient methylmalonic acidemia/uria [83].

Over the years, 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria and methylmalonic semialdehyde deficiency have been recognized as heterogenous conditions, both clinically and biochemically. The small number of patients with 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria described presented with dysmorphic features including a triangular face, low set ears, long philtrum and microcephaly and widely different phenotypes ranging from mild vomiting attacks with normal cognitive development, to profound intellectual impairment and early death [84–86]. Enzymatic or molecular testing of the predicted human cDNA for 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase (HIBADH) were negative in some of these patients [87]. Whether previously described but untested patients will harbor mutations in ALDH6A1 or other gene(s) remains unknown.

Methylmalonyl semialdehyde deficiency can present at newborn screening as hypermethioninemia and is associated with developmental delay, hypotonia and dysmorphic features [88, 89]. The urine metabolic pattern is variable, including beta-alanine, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, both isomers of3-amino- and 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid, and mild methylmalonic aciduria. Mutations in ALDH6A1, have been identified only in a subset of patients with these biochemical findings [90].

1.3. Molecular genetics

All disorders in the BCAA metabolic pathway follow autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, with the exception of Barth syndrome that is X-linked.

Table 2 lists the gene loci and genes identified for the enzymatic defects in this pathway.

Table 2.

Molecular genetics of disorders in the BCAA metabolic pathway

| Disorder | MIM # | Gene | Locus |

| Phenotype/Locus | |||

| Maple syrup urine disease | |||

| Type Ia | 248600, 608348 | BCKDHA | 19q13.1-13.2 |

| Type Ib | 248600, 248611 | BCKDHB | 6q14.1 |

| Type II | 248600, 248610 | DBT | 1p21.2 |

| ?mild variant | 615135, 611065 | PPM1K | 4q22.1 |

| Isovaleric acidemia | 243500, 607036 | IVD | 15q15.1 |

| 3-Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency | 210200, 609010 | MCCC1 | 3q27.1 |

| 210210, 609014 | MCCC2 | 5q13.2 | |

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type I | 250950, 600529 | AUH | 9q22.31 |

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type II: | 302060, 300394 | TAZ | Xq28 |

| Barth syndrome | |||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type III: | 258501, 606580 | OPA3 | 19q13.32 |

| Costeff optic atrophy | |||

| 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type IV: “unclassified” | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| type V | 610198, 608977 | DNAJC19 | 3q26.33 |

| type VI: deafness, encephalopathy, Leigh-like syndrome | 614739, 614725 | SERAC1 | 6q25.3 |

| type VII: cataracts, neurological involvement and neutropenia | 616271, 616254 | CLPB | 11q13.4 |

| 3-Hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency | 246450, 613898 | HMGCL | 1p36.11 |

| Methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 610006, 600301 | ACADSB | 10q26.13 |

| Mitochondrial acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase deficiency | 203750, 607809 | ACAT1 | 11q22.3 |

| Isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency | 611283, 604773 | ACAD8 | 11q25 |

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyryl- CoA deacylase deficiency | 250620, 610690 | HIBCH | 2q32.2 |

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyric aciduria | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Methylmalonic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency | 614105, 603178 | ALDH6A1 | 14q24.3 |

| Propionic acidemia | 606054, 232000 | PCCA | 13q32.3 |

| 606054, 232050 | PCCB | 3q22.3 | |

| Methylmalonic acidemia, isolated | |||

| Mut subtype | 251000, 609058 | MUT | 6p12.2 |

| Cobalamin A | 251100, 607481 | MMAA | 4q31.21 |

| Cobalamin B | 251110, 607568 | MMAB | 12q24.11 |

| Cobalamin D | 277410, 611935 | C2orf25 | 2q32.2 |

2. Therapeutic approaches

In general, early detection and vigilant metabolic control maximizes the chances to avoid significant insults to the developing brain and achieve an optimal outcome for each patient. General measures for all the disorders in this pathway include: a) fasting avoidance with scheduled frequent feeds to ensure the daily requirements for calories and nutrients are met. For the most severe patients this is often achieved with continuous overnight feeding regimens through gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes; b) a high calorie – low protein diet is prescribed to limit the BCAA load, often accompanied by specific amino acids mixtures deficient in selected BCAA; c) conjugation agents, such as L-carnitine and glycine are provided to enable excretion of toxic metabolites; d) hemodialysis for hyperammonemia during acute metabolic decompensations and e) multidisciplinary care to account for the multi-organ manifestations and specific complications associated with each of the disorders.

2.1. Dietary management

Therapy of all the disorders in these biochemical pathways is based on dietary restriction of protein and particularly the offensive amino acids, leucine for IVA or valine and isoleucine for PA and MMA among the other less frequent disorders in the respective pathways, with regular clinical assessments of growth and monitoring of specific biochemical biomarkers. Primary goals of dietary management include: 1) the promotion of growth and anabolism, avoiding fasting or energy imbalance that may result in metabolic decompensation. This is achieved by providing a high caloric intake, continuous feeds through gastrostomy tube, and hospitalization for parenteral nutrition during intercurrent illness; 2) the reduction of toxic intermediates through the provision of medical foods deficient in the offensive amino acids or antibiotics to reduce precursor generation from propiogenic gut flora; 3) the enhancement of excretion of toxic metabolites through the provision of substrates for conjugation, such as carnitine for the acyl-CoA species or glycine in the case of IVA to form isovalerylglycine; 3) the administration of cofactors where indicated, such as thiamine in thiamine-responsive MSUD or hydroxocobalamin in MMA; 4) vigilant monitoring for nutritional deficiencies, such as micronutrients, vitamins and essential amino- and fatty- acids.

There are no evidence-based guidelines for each of the above therapeutic measures employed. This is reflected in the wide range of practices recorded in multicenter studies and the controversies surrounding even the few available therapeutic measures, such as carnitine supplementation. Furthermore, there are only few carefully conducted studies that document the actual dietary requirements and outcomes for these patients [91–95].

The experience gained in MSUD in recent years from clinical and animal studies has led to the design of improved formulas, which are enriched in amino acids that compete with leucine for brain uptake (such as Tyr, Trp, Phe, Met, Thr, His), and in essential fatty acids and micronutrients observed to be deficient with current management (omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, zinc and selenium). Use of this modified formula resulted in improved metabolic control and biochemical parameters, fewer hospitalizations and normal growth and development of the patients [96]. Based on the same pathophysiological paradigm, a synthetic analog of leucine, norleucine, was shown to compete effectively for brain uptake of leucine, improving survival and biochemical aberrations and delaying the encephalopathy symptoms of different mouse models for classic and intermediate MSUD [32], making this an interesting candidate treatment option for the patients.

Similar principles guide the dietary management of MMA/PA. Natural protein needs to be carefully titrated to allow for normal growth, while avoiding an excessive propiogenic amino acid load (isoleucine, valine, methionine and threonine) into the pathway. Adjustment of dietary whole (complete)-protein intake will depend on growth parameters, metabolic stability, stage of renal failure, and other factors [97]. A propiogenic amino acid-deficient- and/or protein-free-formula are given to some individuals to provide extra fluid and calories. In patients with low protein tolerance, severe restriction of propiogenic amino acid precursors (isoleucine, valine, methionine, and threonine) can produce a nutritional deficiency state. Moreover, a severe iatrogenic essential amino acid deficiency can be induced by the relatively high leucine intake through the MMA/PA formulas [98, 99]. Ketoisocaproic acid derived from the supplemented leucine can inhibit the BCKDH kinase and thereby increase the oxidation rates of valine and isoleucine resulting in very low plasma levels of these essential amino acids and negatively affect long-term growth and possibly other outcomes. Moreover, leucine can compete for the uptake of methionine through the blood brain barrier, an effect that can be detrimental for patients with methionine synthetic defects, like cobalamin C disease [99]. These observations further highlight the tight interconnections between the three BCAAs.

Carnitine supplementation has been widely accepted as a means to restore the depleted intramitochondrial free CoA pool and help excrete toxic acyl-CoA compounds in the urine as carnitine esters, for example propionyl-CoA in the form of the less toxic propionylcarnitine, and thereby also prevent secondary carnitine deficiency [100–102]. The efficacy of this approach given the renal handling of supplemental carnitine has been debated [103]. However, a combination of L-carnitine with glycine conjugation in severe forms of isovaleric acidemia was found to provide an efficient means to eliminate isovaleryl-CoA [104, 105]. More recently treatment with phenylbutyrate was shown to increase the de-phosphorylated active form of the E1a subunit, by preventing its phosphorylation by the BCKD kinase. This results in reduced BCAA and BCKA levels in cases with iMSUD [106].

2.2. Mitochondria-targeted therapies

Given the secondary mitochondrial dysfunction affecting various aspects of mitochondrial metabolism that has been documented in an increasing number of disorders in the BCAA metabolic pathway, agents targeting the mitochondria could hold significant therapeutic benefit for these patients.

The use of antioxidants has been evaluated mainly in experimental animal models of organic acidemias, including maple syrup disease [107], isovaleric academia [108], 3-hydroxyisobutyric academia [109], 3 MGA [110] and methylmalonic academia [60, 111], among others. Glutathione deficiency was documented during a metabolic crisis in a patient with isolated MMA, who responded to ascorbate therapy [112], while a regimen including coenzyme Q10 and vitamin E has been shown to prevent progression of acute optic nerve involvement in a different MMA patient [113]. Despite these encouraging case reports, systematic randomized multicenter studies addressing the role of antioxidants in the acute or chronic management of MMA or other disorders in these pathways are currently lacking. This is a well-recognized shortcoming in treatment studies for mitochondrial disorders of all principles, where only very few well-conducted randomized controlled studies were able to convincingly show benefit of such therapeutic interventions [114–117].

The expectation from ongoing research studies on animal models is that gaining better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying the mitochondrial involvement of each of these disorders, we will be able to design better disease-specific therapies.

2.3. Organ transplantation

Liver transplantation has been used to cure different inborn errors of metabolism, including urea cycle defects, tyrosinemia, familial hypercholesterolemia, primary hyperoxaluria, Wilson’s disease, Criggler-Najar syndrome and others. Among the BCAA metabolism disorders, classic MSUD is probably the only condition where liver transplantation has been shown to have a significant therapeutic, though not completely curative effect.

MSUD: Liver transplantation has been reported to improve the metabolic instability greatly and allow protein intake liberalization in MSUD patients [118, 119]. It is suggested that the donor liver introduces sufficient BCKD activity in the body that is also subject to physiologic regulation, resulting in the maintenance of near-normal plasma BCAA and αKIC levels through various dietary and physiological challenges. Patients can liberalize their protein intake and are less vulnerable during intercurrent illnesses, although significant leucinosis can occur during periods of stress. Although there is no further deterioration, existing neurocognitive dysfunction or behavioral problems cannot bereversed.

There have been a number of cases where classical MSUD patient livers were successfully transplanted into a recipient (‘domino’ transplantation) with no adverse consequences for peripheral amino acid homeostasis on unrestricted protein intake [118, 120]. Such a utilization of explanted organs from patients with MSUD or other organic acidurias may alleviate some of the ethical controversies surrounding allograft distribution.

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) has been offered to patients with PA who suffer frequent metabolic decompensations, recurrent hyperammonemia, and/or restricted growth. There have been several reported cases of successful liver transplantation in PA [121–123]. Furthermore, it has been shown that transplantation can restore cardiac function in cases with PA complicated by dilated cardiomyopathy [124]. However, the procedure is not curative and is still associated with significant morbidity and mortality. It does not completely protect against a metabolic stroke, hyperammonemia or metabolic decompensations, while in a number of patients the renal disease, as well as cardiac manifestations, have progressed despite the procedure [125]. There have been fewer cases of early elective transplants in this disorder to address its effects prospectively on neurological and other disease-related outcomes.

Although renal transplant has an absolute indication for patients with MMA in end-stage renal failure, the benefits of elective liver, kidney or combined liver and kidney transplantation are less conclusive [126–132]. Although organ transplant stabilizes the patients and decreases the frequency of admissions associated with metabolic decompensations, it does not completely prevent devastating neurological complications, such as the metabolic stroke [133]. Levels of plasma MMA post-transplantation remain significantly elevated, most likely due to extra-hepatorenal MMA production from tissues such as the muscle and brain [63]. Continued dietary restriction and vigilant metabolic follow-up is therefore recommended post transplant.

References

- [1]. Harper A.E., Miller R.H. and Block K.P., Branched-chain amino acid metabolism, Annu Rev Nutr 4 (1984), 409–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Chuang D.T., Wynn R.M. and Shih V.E., Maple Syrup Urine Disease (Branched-Chain Ketoaciduria, , (McGraw Hill, New York, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Shimomura Y., Obayashi M., Murakami T. and Harris R.A., Regulation of branched-chain amino acid catabolism: Nutritional and hormonal regulation of activity and expression of the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase kinase, Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 4 (2001), 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Hargreaves K.M. and Pardridge W.M., Neutral amino acid transport at the human blood-brain barrier, J Biol Chem 263 (1988), 19392–19397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kimball S.R., Shantz L.M., Horetsky R.L. and Jefferson L.S., Leucine regulates translation of specific mRNAs in L6 myoblasts through mTOR-mediated changes in availability of eIF4E and phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6, J Biol Chem 274 (1999), 11647–11652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Beugnet A., Tee A.R., Taylor P.M. and Proud C.G., Regulation of targets of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signalling by intracellular amino acid availability, Biochem J 372 (2003), 555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Gingras A.C., Raught B. and Sonenberg N., Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR, Genes Dev 15 (2001), 807–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Frost R.A. and Lang C.H., mTor signaling in skeletal muscle during sepsis and inflammation: Where does it all go wrong? Physiology (Bethesda) 26 (2011), 83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Malaisse W.J., Hutton J.C., Carpinelli A.R., Herchuelz A. and Sener A., The stimulus-secretion coupling of amino acid-induced insulin release: Metabolism and cationic effects of leucine, Diabetes 29 (1980), 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Sener A. and Malaisse W.J., L-leucine and a nonmetabolized analogue activate pancreatic islet glutamate dehydrogenase, Nature 288 (1980), 187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Henquin J.C., Dufrane D. and Nenquin M., Nutrient control of insulin secretion in isolated normal human islets, Diabetes 55 (2006), 3470–3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Gao Z., et al. , Distinguishing features of leucine and alpha-ketoisocaproate sensing in pancreatic beta-cells, Endocrinology 144 (2003), 1949–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Patti M.E., Brambilla E., Luzi L., Landaker E.J. and Kahn C.R., Bidirectional modulation of insulin action by amino acids, J Clin Invest 101 (1998), 1519–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Ropelle E.R., et al. , A central role for neuronal AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in high-protein diet-induced weight loss, Diabetes 57 (2008), 594–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Cota D., et al. , Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake, Science 312 (2006), 927–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Morton D.H., Strauss K.A., Robinson D.L., Puffenberger E.G. and Kelley R.I., Diagnosis and treatment of maple syrup disease: A study of 36 patients, Pediatrics 109 (2002), 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Kaplan P., et al. , Intellectual outcome in children with maple syrup urine disease, J Pediatr 119 (1991), 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Simon E., et al. , Maple syrup urine disease: Favourable effect of early diagnosis by newborn screening on the neonatal course of the disease, J Inherit Metab Dis 29 (2006), 532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Heldt K., Schwahn B., Marquardt I., Grotzke M. and Wendel U., Diagnosis of MSUD by newborn screening allows early intervention without extraneous detoxification, Mol Genet Metab 84 (2005), 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Puckett R.L., et al. , Maple syrup urine disease: Further evidence that newborn screening may fail to identify variant forms, Mol Genet Metab 100 (2010), 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Oglesbee D., et al. , Second-tier test for quantification of alloisoleucine and branched-chain amino acids in dried blood spots to improve newborn screening for maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), Clin Chem 54 (2008), 542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Fingerhut R., Simon E., Maier E.M., Hennermann J.B. and Wendel U., Maple syrup urine disease: Newborn screening fails to discriminate between classic and variant forms, Clin Chem 54 (2008), 1739–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Leonard J.V., Vijayaraghavan S. and Walter J.H., The impact of screening for propionic and methylmalonic acidaemia, Eur J Pediatr 162(Suppl 1) (2003), S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Dionisi-Vici C., Deodato F., Roschinger W., Rhead W. and Wilcken B., ’Classical’ organic acidurias, propionic aciduria, methylmalonic aciduria and isovaleric aciduria: Long-term outcome and effects of expanded newborn screening using tandem mass spectrometry, J Inherit Metab Dis 29 (2006), 383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Lindner M., et al. , Newborn screening for methylmalonic acidurias–optimization by statistical parameter combination, J Inherit Metab Dis 31 (2008), 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Turgeon C.T., et al. , Determination of total homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, and 2-methylcitric acid in dried blood spots by tandem mass spectrometry, Clin Chem 56 (2010), 1686–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Strauss K.A., Puffenberger E.G. and Morton D.H., Maple Syrup Urine Disease. in GeneReviews [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; (Pagon RA, Bird TC, Dolan CR, Stephens K, 2006 Jan 30 [updated 2009 Dec 15]). [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Yudkoff M., et al. , Astrocyte leucine metabolism: Significance of branched-chain amino acid transamination, J Neurochem 66 (1996), 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Yudkoff M., et al. , Brain amino acid requirements and toxicity: The example of leucine, J Nutr 135 (2005), 1513S–1538S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Yudkoff M., Brain metabolism of branched-chain amino acids, Glia 21 (1997), 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Hutson S.M., Lieth E. and LaNoue K.F., Function of leucine in excitatory neurotransmitter metabolism in the central nervous system, J Nutr 131 (2001), 846S–850S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Zinnanti W.J., et al. , Dual mechanism of brain injury and novel treatment strategy in maple syrup urine disease, Brain 132 (2009), 903–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Prensky A.L. and Moser H.W., Brain lipids, proteolipids, and free amino acids in maple syrup urine disease, J Neurochem 13 (1966), 863–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. McKenna M.C., et al. , Alpha-ketoisocaproate alters the production of both lactate and aspartate from [U-13C]glutamate in astrocytes: A 13C NMR study, J Neurochem 70 (1998), 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Shestopalov A.I. and Kristal B.S., Branched chain keto-acids exert biphasic effects on alpha-ketoglutarate-stimulated respiration in intact rat liver mitochondria, Neurochem Res 32 (2007), 947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Amaral A.U., et al. , Alpha-ketoisocaproic acid and leucine provoke mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction in rat brain, Brain Res 1324 (2010), 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Jan W., et al. , MR diffusion imaging and MR spectroscopy of maple syrup urine disease during acute metabolic decompensation, Neuroradiology 45 (2003), 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Smith Q.R., Takasato Y., Sweeney D.J. and Rapoport S.I., Regional cerebrovascular transport of leucine as measured by the in situ brain perfusion technique, J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 5 (1985), 300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Smith Q.R. and Takasato Y., Kinetics of amino acid transport at the blood-brain barrier studied using an in situ brain perfusion technique, Ann N Y Acad Sci 481 (1986), 186–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Schonberger S., Schweiger B., Schwahn B., Schwarz M. and Wendel U., Dysmyelination in the brain of adolescents and young adults with maple syrup urine disease, Mol Genet Metab 82 (2004), 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Treacy E., et al. , Maple syrup urine disease: Interrelations between branched-chain amino-, oxo- and hydroxyacids; implications for treatment; associations with CNS dysmyelination, J Inherit Metab Dis 15 (1992), 121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Strauss K.A., et al. , Classical maple syrup urine disease and brain development: Principles of management and formula design, Mol Genet Metab 99 (2010), 333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Strauss K.A. and Morton D.H., Branched-chain ketoacyl dehydrogenase deficiency: Maple syrup disease, Curr Treat Options Neurol 5 (2003), 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Utter M.F., Keech D.B. and Scrutton M.C., A possible role for acetyl CoA in the control of gluconeogenesis, Adv Enzyme Regul 2 (1964), 49–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. McLaughlin B.A., Nelson D., Silver I.A., Erecinska M. and Chesselet M.F., Methylmalonate toxicity in primary neuronal cultures, Neuroscience 86 (1998), 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Kolker S., Ahlemeyer B., Krieglstein J. and Hoffmann G.F., Methylmalonic acid induces excitotoxic neuronal damage in vitro, J Inherit Metab Dis 23 (2000), 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. de Mello C.F., et al. , Intrastriatal methylmalonic acid administration induces rotational behavior and convulsions through glutamatergic mechanisms, Brain Res 721 (1996), 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Malfatti C.R., et al. , Intrastriatal methylmalonic acid administration induces convulsions and TBARS production, and alters Na+, K+-ATPase activity in the rat striatum and cerebral cortex, Epilepsia 44 (2003), 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Malfatti C.R., et al. , Convulsions induced by methylmalonic acid are associated with glutamic acid decarboxylase inhibition in rats: A role for GABA in the seizures presented by methylmalonic acidemic patients? Neuroscience 146 (2007), 1879–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Cheema-Dhadli S., Leznoff C.C. and Halperin M.L., Effect of 2-methylcitrate on citrate metabolism: Implications for the management of patients with propionic acidemia and methylmalonic aciduria, Pediatr Res 9 (1975), 905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Halperin M.L., Schiller C.M. and Fritz I.B., The inhibition by methylmalonic acid of malate transport by the dicarboxylate carrier in rat liver mitochondria. A possible explantation for hypoglycemia in methylmalonic aciduria, J Clin Invest 50 (1971), 2276–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Okun J.G., et al. , Neurodegeneration in methylmalonic aciduria involves inhibition of complex II and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and synergistically acting excitotoxicity, J Biol Chem 277 (2002), 14674–14680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Oberholzer V.G., Levin B., Burgess E.A. and Young W.F., Methylmalonic aciduria. An inborn error of metabolism leading to chronic metabolic acidosis, Arch Dis Child 42 (1967), 492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Coude F.X., Sweetman L. and Nyhan W.L., Inhibition by propionyl-coenzyme A of N-acetylglutamate synthetase in rat liver mitochondria. A possible explanation for hyperammonemia in propionic and methylmalonic acidemia, J Clin Invest 64 (1979), 1544–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Filipowicz H.R., Ernst S.L., Ashurst C.L., Pasquali M. and Longo N., Metabolic changes associated with hyperammonemia in patients with propionic acidemia, Mol Genet Metab 88 (2006), 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Hayasaka K., et al. , Glycine cleavage system in ketotic hyperglycinemia: A reduction of H-protein activity, Pediatr Res 16 (1982), 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Hayasaka K. and Tada K., Effects of the metabolites of the branched-chain amino acids and cysteamine on the glycine cleavage system, Biochem Int 6 (1983), 225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Kolker S. and Okun J.G., Methylmalonic acid–an endogenous toxin? Cell Mol Life Sci 62 (2005), 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Morath M.A., et al. , Neurodegeneration and chronic renal failure in methylmalonic aciduria–a pathophysiological approach, J Inherit Metab Dis 31 (2008), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Manoli I., et al. , Targeting proximal tubule mitochondrial dysfunction attenuates the renal disease of methylmalonic acidemia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (2013), 13552–13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Mitchell G.A., et al. , Hereditary and acquired diseases of acyl-coenzyme A metabolism, Mol Genet Metab 94 (2008), 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Chandler R.J., et al. , Mitochondrial dysfunction in mut methylmalonic acidemia, FASEB J 23 (2009), 1252–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63]. Chandler R.J., et al. , Metabolic phenotype of methylmalonic acidemia in mice and humans: The role of skeletal muscle, BMC Med Genet 8 (2007), 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Schwab M.A., et al. , Secondary mitochondrial dysfunction in propionic aciduria: A pathogenic role for endogenous mitochondrial toxins, Biochem J 398 (2006), 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Atkuri K.R., et al. , Inherited disorders affecting mitochondrial function are associated with glutathione deficiency and hypocitrullinemia, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (2009), 3941–3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66]. de Keyzer Y., et al. , Multiple OXPHOS deficiency in the liver, kidney, heart, and skeletal muscle of patients with methylmalonic aciduria and propionic aciduria, Pediatr Res 66 (2009), 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Valayannopoulos V., et al. , Multiple OXPHOS deficiency in the liver of a patient with CblA methylmalonic aciduria sensitive to vitamin B(12), J Inherit Metab Dis 32 (2009), 159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68]. Mc Guire P.J., Parikh A. and Diaz G.A., Profiling of oxidative stress in patients with inborn errors of metabolism, Mol Genet Metab 98 (2009), 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69]. Gunay-Aygun M., 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria: A common biochemical marker in various syndromes with diverse clinical features, Mol Genet Metab 84 (2005), 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70]. Wortmann S.B., Kluijtmans L.A., Engelke U.F., Wevers R.A. and Morava E., The 3-methylglutaconic acidurias: What’s new? J Inherit Metab Dis, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71]. Wortmann S.B., et al. , 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type I redefined: A syndrome with late-onset leukoencephalopathy, Neurology 75 (2010), 1079–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72]. Kelley R.I., et al. , X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy with neutropenia, growth retardation, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, J Pediatr 119 (1991), 738–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73]. Di Rosa G., et al. , Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cataract, developmental delay, lactic acidosis: A novel subtype of 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 29 (2006), 546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74]. Ryu S.W., Jeong H.J., Choi M., Karbowski M. and Choi C., Optic atrophy 3 as a protein of the mitochondrial outer membrane induces mitochondrial fragmentation, Cell Mol Life Sci 67 (2010), 2839–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75]. Lustbader J.W., et al. , ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease, Science 304 (2004), 448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76]. Zschocke J., et al. , Progressive infantile neurodegeneration caused by 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: A novel inborn error of branched-chain fatty acid and isoleucine metabolism, Pediatr Res 48 (2000), 852–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77]. Perez-Cerda C., et al. , 2-Methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (MHBD) deficiency: An X-linked inborn error of isoleucine metabolism that may mimic a mitochondrial disease, Pediatr Res 58 (2005), 488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78]. Korman S.H., Inborn errors of isoleucine degradation: A review, Mol Genet Metab 89 (2006), 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79]. Brown G.K., et al. , beta-hydroxyisobutyryl coenzyme A deacylase deficiency: A defect in valine metabolism associated with physical malformations, Pediatrics 70 (1982), 532–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80]. Ferdinandusse S., et al. , HIBCH mutations can cause Leigh-like disease with combined deficiency of multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes and pyruvate dehydrogenase, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 8 (2013), 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81]. Loupatty F.J., et al. , Mutations in the gene encoding 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase results in progressive infantile neurodegeneration, Am J Hum Genet 80 (2007), 195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82]. Sass J.O., et al. , 3-Hydroxyisobutyrate aciduria and mutations in the ALDH6A1 gene coding for methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, J Inherit Metab Dis 35 (2012), 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83]. Marcadier J.L., et al. , Mutations in ALDH6A1 encoding methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase are associated with dysmyelination and transient methylmalonic aciduria, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 8 (2013), 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84]. Ko F.J., Nyhan W.L., Wolff J., Barshop B. and Sweetman L., 3-Hydroxyisobutyric aciduria: An inborn error of valine metabolism, Pediatric Research 30 (1991), 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85]. Chitayat D., et al. , Brain dysgenesis and congenital intracerebral calcification associated with 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria, The Journal of Pediatrics 121 (1992), 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86]. Boulat O., Benador N., Girardin E. and Bachmann C., 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria with a mild clinical course, Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 18 (1995), 204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87]. Loupatty F.J., et al. , Clinical, biochemical, and molecular findings in three patients with 3-hydroxyisobutyric aciduria, Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 87 (2006), 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88]. Pollitt R.J., Green A. and Smith R., Excessive excretion of beta-alanine and of 3-hydroxypropionic, R- and S-3-aminoisobutyric, R- and S-3-hydroxyisobutyric and S-2-(hydroxymethyl)butyric acids probably due to a defect in the metabolism of the corresponding malonic semialdehydes, Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 8 (1985), 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89]. Gibson K.M., Lee C.F., Bennett M.J., Holmes B. and Nyhan W.L., Combined malonic, methylmalonic and ethylmalonic acid semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiencies: An inborn error of beta-alanine, L-valine and L-alloisoleucine metabolism? Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 16 (1993), 563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90]. Chambliss K.L., Gray R.G., Rylance G., Pollitt R.J. and Gibson K.M., Molecular characterization of methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, J Inherit Metab Dis 23 (2000), 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91]. Yannicelli S., et al. , Improved growth and nutrition status in children with methylmalonic or propionic acidemia fed an elemental medical food, Mol Genet Metab 80 (2003), 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92]. Hauser N.S., Manoli I., Graf J.C., Sloan J. and Venditti C.P., Variable dietary management of methylmalonic acidemia: Metabolic and energetic correlations, Am J Clin Nutr 93 (2011), 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93]. Touati G., et al. , Methylmalonic and propionic acidurias: Management without or with a few supplements of specific amino acid mixture, J Inherit Metab Dis 29 (2006), 288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94]. de Baulny H.O., et al. , Methylmalonic and propionic acidaemias: Management and outcome, J Inherit Metab Dis 28 (2005), 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95]. Zwickler T., et al. , Diagnostic work-up and management of patients with isolated methylmalonic acidurias in European metabolic centres, J Inherit Metab Dis 31 (2008), 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96]. Strauss K.A., et al. , Classical maple syrup urine disease and brain development: Principles of management and formula design, Mol Genet Metab 99 (2010), 333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97]. Baumgartner M.R., et al. , Proposed guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic and propionic academia, Orphanet J Rare Dis 9 (2014), 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98]. Manoli I., Myles J.G., Sloan J.L., Shchelochkov O.A. and Venditti C.P., A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 1: Isolated methylmalonic acidemias, Genet Med 18 (2016), 386–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99]. Manoli I., et al. , A critical reappraisal of dietary practices in methylmalonic acidemia raises concerns about the safety of medical foods. Part 2: Cobalamin C deficiency, Genet Med 18 (2016), 396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100]. Roe C.R., Millington D.S., Maltby D.A., Bohan T.P. and Hoppel C.L., L-carnitine enhances excretion of propionyl coenzyme A as propionylcarnitine in propionic acidemia, J Clin Invest 73 (1984), 1785–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101]. Chalmers R.A., Roe C.R., Stacey T.E. and Hoppel C.L., Urinary excretion of l-carnitine and acylcarnitines by patients with disorders of organic acid metabolism: Evidence for secondary insufficiency of l-carnitine, Pediatr Res 18 (1984), 1325–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102]. Sauer S.W., Okun J.G., Hoffmann G.F., Koelker S. and Morath M.A., Impact of short- and medium-chain organic acids, acylcarnitines, and acyl-CoAs on mitochondrial energy metabolism, Biochim Biophys Acta 1777 (2008), 1276–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103]. Stanley C.A., et al. , Renal handling of carnitine in secondary carnitine deficiency disorders, Pediatr Res 34 (1993), 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104]. Chalmers R.A., et al. , L-carnitine and glycine therapy in isovaleric acidaemia, J Inherit Metab Dis 8(Suppl 2) (1985), 141–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105]. de Sousa C., et al. , The response to L-carnitine and glycine therapy in isovaleric acidaemia, Eur J Pediatr 144 (1986), 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106]. Brunetti-Pierri N., et al. , Phenylbutyrate therapy for maple syrup urine disease, Hum Mol Genet 20 (2011), 631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107]. Mescka C., et al. , In vivo neuroprotective effect of L-carnitine against oxidative stress in maple syrup urine disease, Metab Brain Dis 26 (2011), 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108]. Ribeiro C.A., et al. , Creatine administration prevents Na+, K+-ATPase inhibition induced by intracerebroventricular administration of isovaleric acid in cerebral cortex of young rats, Brain Res 1262 (2009), 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109]. Viegas C.M., et al. , Evidence that 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid inhibits key enzymes of energy metabolism in cerebral cortex of young rats, Int J Dev Neurosci 26 (2008), 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110]. Ribeiro C.A., Hickmann F.H. and Wajner M., Neurochemical evidence that 3-methylglutaric acid inhibits synaptic Na+, K+-ATPase activity probably through oxidative damage in brain cortex of young rats, Int J Dev Neurosci 29 (2011), 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111]. Fernandes C.G., et al. , Experimental evidence that methylmalonic acid provokes oxidative damage and compromises antioxidant defenses in nerve terminal and striatum of young rats, Cell Mol Neurobiol 31 (2011), 775–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112]. Treacy E., et al. , Glutathione deficiency as a complication of methylmalonic acidemia: Response to high doses of ascorbate, J Pediatr 129 (1996), 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113]. Pinar-Sueiro S., Martinez-Fernandez R., Lage-Medina S., Aldamiz-Echevarria L. and Vecino E., Optic neuropathy in methylmalonic acidemia: The role of neuroprotection, J Inherit Metab Dis (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114]. Kerr D.S., Treatment of mitochondrial electron transport chain disorders: A review of clinical trials over the past decade, Mol Genet Metab 99 (2010), 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115]. Klopstock T., et al. , A randomized placebo-controlled trial of idebenone in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, Brain (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116]. Glover E.I., et al. , A randomized trial of coenzyme Q10 in mitochondrial disorders, Muscle Nerve 42 (2010), 739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117]. Tarnopolsky M.A., Roy B.D. and MacDonald J.R., A randomized, controlled trial of creatine monohydrate in patients with mitochondrial cytopathies, Muscle Nerve 20 (1997), 1502–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118]. Mazariegos G.V., et al. , Liver transplantation for classical maple syrup urine disease: Long-term follow-up in 37 patients and comparative united network for organ sharing experience, J Pediatr (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119]. Strauss K.A., et al. , Elective liver transplantation for the treatment of classical maple syrup urine disease, Am J Transplant 6 (2006), 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120]. Barshop B.A. and Khanna A., Domino hepatic transplantation in maple syrup urine disease, N Engl J Med 353 (2005), 2410–2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121]. Vara R., et al. , Liver transplantation for propionic acidemia in children, Liver Transpl 17 (2011), 661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122]. Saudubray J.M., et al. , Liver transplantation in propionic acidaemia,S65–S, Eur J Pediatr 158 (1999)(Suppl 2), 69–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123]. Barshes N.R., et al. , Evaluation and management of patients with propionic acidemia undergoing liver transplantation: A comprehensive review, Pediatr Transplant 10 (2006), 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124]. Romano S., et al. , Cardiomyopathies in propionic aciduria are reversible after liver transplantation, J Pediatr 156 (2010), 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125]. Charbit-Henrion F., et al. , Early and late complications after liver transplantation for propionic acidemia in children: A two centers study, Am J Transplant 15 (2015), 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126]. Leonard J.V., Walter J.H. and McKiernan P.J., The management of organic acidaemias: The role of transplantation, J Inherit Metab Dis 24 (2001), 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127]. Nyhan W.L., Gargus J.J., Boyle K., Selby R. and Koch R., Progressive neurologic disability in methylmalonic acidemia despite transplantation of the liver, Eur J Pediatr 161 (2002), 377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128]. Kasahara M., et al. , Current role of liver transplantation for methylmalonic acidemia: A review of the literature, Pediatr Transplant 10 (2006), 943–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129]. Kaplan P., Ficicioglu C., Mazur A.T., Palmieri M.J. and Berry G.T., Liver transplantation is not curative for methylmalonic acidopathy caused by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency, Mol Genet Metab 88 (2006), 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130]. Mc Guire P.J., et al. , Combined liver-kidney transplant for the management of methylmalonic aciduria: A case report and review of the literature, Mol Genet Metab 93 (2008), 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131]. Sloan J.L., Manoli I. and Venditti C.P., Liver or combined liver-kidney transplantation for patients with isolated methylmalonic acidemia: Who and when? J Pediatr 166 (2015), 1346–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132]. Niemi A.K., et al. , Treatment of methylmalonic acidemia by liver or combined liver-kidney transplantation,–e, J Pediatr 166 (1461), 1–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133]. Chakrapani A., Sivakumar P., McKiernan P.J. and Leonard J.V., Metabolic stroke in methylmalonic acidemia five years after liver transplantation, J Pediatr 140 (2002), 261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]