Abstract

To further develop therapeutic strategies targeting the proteasome system, we studied the antitumor activity and mechanisms of action of MLN2238, a reversible proteasome inhibitor, in preclinical lymphoma models. Experiments were conducted in rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines, rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (RRCL), and primary B-cell lymphoma cells. Cells were exposed to MLN2238 or caspase-dependent inhibitors, and differences in cell viability, alterations in apoptotic protein levels, effects on cell cycle, and the possibility of synergy when combined with chemotherapeutic agents were evaluated. MLN2238 showed more potent dose-dependent and time-dependent cytotoxicity and inhibition of cell proliferation in lymphoma cells than bortezomib. Our data suggest that MLN2238 can induce caspase-independent cell death in RRCL. MLN2238 (and to a much lesser degree bortezomib) reduced RRCL S phase and induced cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. Exposure of rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines and RRCL to MLN2238 potentiated the cytotoxic effects of gemcitabine, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel and overcame resistance to chemotherapy in RRCL. MLN2238 is a potent proteasome inhibitor active in rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive and rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell models and potentiates the antitumor activity of chemotherapy agents and has the potential of becoming an effective therapeutic agent in the treatment of therapy-resistant B-cell lymphoma.

Keywords: B-cell lymphoma, bortezomib, MLN2238, proteasome inhibition, rituximab resistance, ubiquitin–proteasome system

Introduction

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is essential to the tightly regulated process of intracellular protein degradation and impacts several cellular pathways. The UPS targets and catabolizes proteins that are damaged, miss-folded, or selectively tagged for degradation, including those involved in cell growth and proliferation, cell cycle regulation, gene transcription, and programmed cell death [1–3]. Deregulation of the UPS has been implicated in the development, sustenance, and progression of neoplastic cells that lack cell cycle checkpoints and are highly susceptible to proteasome inhibition [4].

Bortezomib (BTZ) is the first-in-class of two proteasome inhibitors already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat multiple myeloma (MM) (i.e. BTZ and carfilzomib) and relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) (i.e. BTZ). Pharmacological inhibition of the UPS by BTZ has resulted in improved clinical outcomes in patients with MM and, to a lesser degree, in relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma. Despite this observed clinical activity, BTZ-associated cytotoxic activity in B-cell lymphoma has been hindered by treatment-related toxicities preventing further dose escalation and the emergence of acquired resistance. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) requiring dose reduction or treatment discontinuation is a major barrier for the optimal cytotoxic dosing of BTZ in the treatment of patients with B-cell lymphoma. Grade 3 or 4 BIPN has been reported in 37–44% of patients exposed to the drug either as a single agent or in combination with systemic chemotherapy [5–10]. Ongoing efforts have been allocated in evaluating alternative routes of administration (e.g. subcutaneous) and/or dose schedules in an attempt to decrease the incidence and/or the severity of BIPN. Alternatively, novel proteasome inhibitors with a more favorable therapeutic index are being developed and are entering clinical trials.

MLN9708, an investigational small-molecule proteasome inhibitor, is a boronic acid analogue that selectively and reversibly inhibits the β5 subunit sites of the 20S proteasome. Structurally, MLN9708 (ixazomib citrate) is an orally administered drug that is hydrolyzed into its active form, MLN2238 (ixazomib). Compared with BTZ, MLN2238 has a shorter proteasome dissociation half-life and improved antitumor activity in human cancer xenograft models [11,12]. MLN9708 is the first oral proteasome inhibitor that has entered into phase I/II/III clinical studies. The results of early MLN9708 clinical studies suggest that it has a lower incidence and severity of peripheral neuropathy compared with BTZ. Grade 1–2 peripheral neuropathy has been reported in 7–17% of patients treated in phase I/II studies. No grade 3–4 peripheral neuropathy has been observed to date [13–17].

Given its favorable toxicity profile observed in MM and relapsed/refractory lymphoma clinical trials and the need to develop alternative strategies to block the UPS in relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma, MLN9708 is an attractive therapeutic agent to evaluate in lymphoid malignancies. In this study, we focused on evaluating and comparing the cytotoxic activity of MLN2238 to BTZ in rituximab-sensitive and rituximab-resistant lymphoma preclinical models. Our results support the further investigation of MLN9708 in patients with refractory B-cell lymphoma.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive Raji cell lines (RSCL) (Burkitt’s lymphoma) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Maryland, USA). Rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (RRCL) were generated and characterized in our laboratory as described previously [18]. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Grand Island, New York, USA), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

MLN2238 was provided by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). BTZ, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and doxorubicin were obtained from the Pharmacy Department at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (Buffalo, New York, USA). Primary antihuman antibodies against Bak, Bax, and actin were obtained from Sigma Chemicals; PARP-1, Bcl-2, and Mcl-1 from BD Pharmigen (San Jose, California, USA); Noxa from Calbiochem (San Diego, California, USA); and p53 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Barbara, California, USA). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA).

Patient samples

Neoplastic or normal B-cells were isolated on biopsy material obtained from lymphoma patients treated at Roswell Park Cancer Institute by negative selection using magnetic beads. Briefly, tissue was disrupted mechanically and cells were passed through a 100 μm cell strainer. Subsequently, lymphocytes were enriched by density centrifugation. B-cells were then isolated from enriched lymphocytes by MACS separation using a human B-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, California, USA).

In-vitro effects of MLN2238 in lymphoma cell lines and primary tumor cells isolated from lymphoma patients

RSCL and RRCL as well as primary cells isolated from lymphoma patients were resuspended in RPMI media and seeded into 384-well plates at a density of 5 × 105/ml and exposed to BTZ or MLN2238 at escalating doses. Following a 24- and 48-h period of incubation, cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The ATP content (viability) was determined as a percentage of the luminescence produced compared with the control cells.

Changes in Bcl-2 family members and other programmed cell death-regulatory proteins

RSCL and RRCL were exposed to MLN2238 or BTZ (10 nmol/l) for 48 h. Subsequently, cells were collected by centrifugation and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors (Cocktail Set 1; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gels. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% milk for 1 h, incubated overnight with primary antibodies of interest (Bax, Bak, PARP, Mcl-1, etc.), followed by appropriate secondary antibodies (alkaline phosphatase-conjugated) at a dilution of 1: 5000, followed by detection by Western Lightening Plus-ECL (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and exposed on a Kodak-XAR film (Kodak, Rochester, New York, USA).

Effect of caspase inhibition on MLN2238 cytotoxic activity

RSCL and RRCL were exposed to the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh (5 μmol/l) (MBL International, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) for 1 h and subsequently exposed to MLN2238 (5, 10, 25 nmol/l) or vehicle (control) for 48 h. Differences in cell viability following caspase inhibition were determined using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay.

Cell cycle analysis

RSCL and RRCL were treated with MLN2238 or BTZ 10 nmol/l for 24 h. Cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 70% ethanol at −20°C for 30 min, incubated with 100 μg/ml RNase for 30 min (Sigma Chemicals), and stained with 50 μg/ml PI (Sigma Chemicals). DNA contents were analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSC-Calibur (BD Biosciences) and FCS express software (DeNovo Software, Los Angeles, California, USA).

Statistical analysis

In-vitro experiments were repeated in triplicate and the results are reported as the SD. Statistical differences between treatment groups and controls were determined using the χ2-test (SPSS version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences were considered significant when the P-value was less than 0.05.

Results

MLN2238 is more potent than BTZ in inducing cell death and inhibiting proliferation in RSCL and RRCL

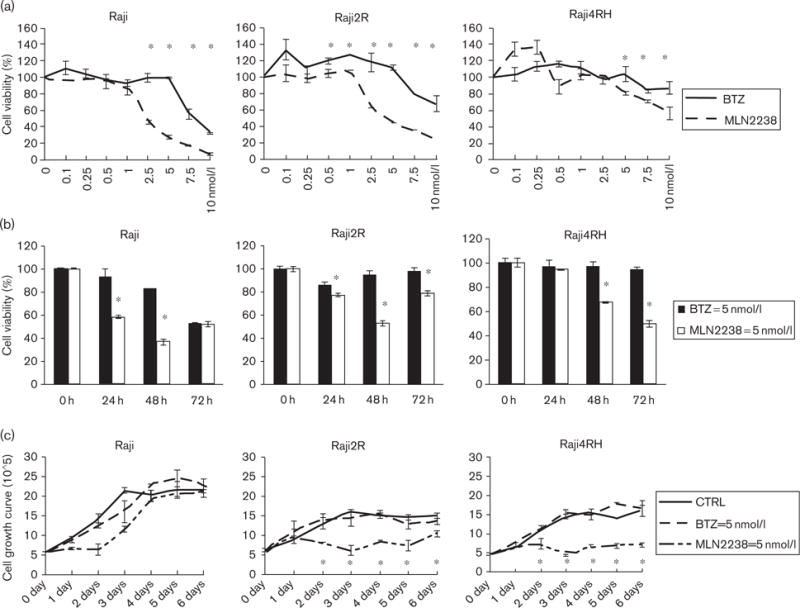

To evaluate and compare the cytotoxic activity of MLN2238 to BTZ, we used a cell line model of therapy-resistant B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) characterized previously by our group [18,19]. RSCL (Raji) and RRCL (Raji2R and Raji4RH) were exposed to various concentrations of MLN2238 or BTZ for up to 48 h and changes in cell viability were assessed using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay. There were significant dose-dependent and time-dependent differences in the viability of Raji versus RRCL in response to exposure to MLN2238 or BTZ (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1a and 1b). In addition, prolonged exposure of RSCL and RRCL to MLN2238 but not BTZ resulted in significant cell growth inhibition (Fig. 1c). Together, these in-vitro data suggest that MLN2238 appears to be more potent inducing cell death and antiproliferation in B-cell NHL than BTZ.

Fig. 1.

MLN2238 induces a dose-dependent and time-dependent reduction in cell viability and cellular growth in Raji, Raji2R, and Raji4RH. (a) Dose-dependent effects of MLN2238 and bortezomib (BTZ) in rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines (RSCL) and rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (RRCL). Raji and RRCL (Raji2R and Raji4RH) were exposed to MLN2238 or BTZ at the indicated concentrations in RPMI in 386-well plates for 48 h and cell viability was assessed using a CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay. The data were presented as the mean and SD of three independent experiments. (b) Time-dependent effects of MLN2238 and BTZ on cell viability. MLN2238 induced statistically significant killing of Raji resistant cells, but not the parental Raji cells. (c) Raji family cells (RSCL and RRCL) were incubated in 5 nmol/l of MLN2238 or BTZ, followed by viable cell count every day. Mean±SD from three independent experiments are shown. There were no statistically significant differences between BTZ-treated cells and controls in Raji parental cells, but MLN2238 induced antiproliferation in the RRCL. *P ≤ 0.05 comparing MLN2238 versus BTZ.

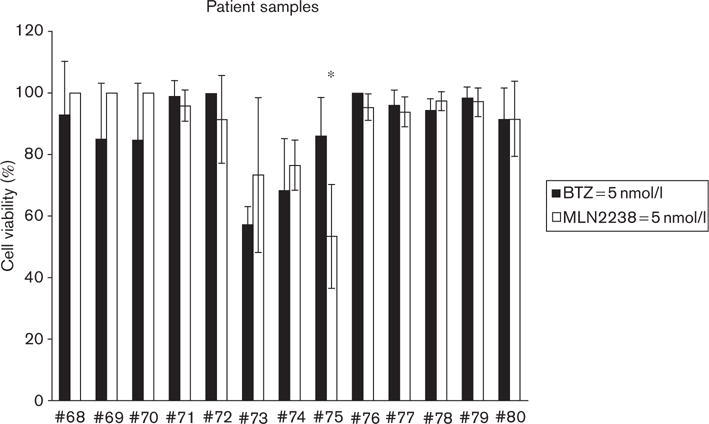

Ex-vivo effects of MLN2238 in primary tumor cells isolated from lymphoma patients

To evaluate differences in the biological activity between MLN2238 and BTZ in a more clinically relevant lymphoma model, we exposed primary tumor cells isolated from B-cell lymphoma patients (n = 13) to either agent for up to 48 h (Fig. 2) In contrast to what we observed in cell lines, MLN2238 was equivalent in terms of cytotoxic activity to BTZ in the limited number of available primary tumor cells tested. At the dose examined (5 nmol/l), MLN2238 and BTZ had similar cytotoxic activity, with the exception of one case (patient #75, Hodgkin’s lymphoma).

Fig. 2.

Primary lymphoma patient samples are sensitive to MLN2238. Variable cytotoxic activity of MLN2238 was found against primary tumor cells isolated from patients with B-cell lymphomas (n = 13). In one case of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (*), MLN2238 induced better cytotoxic activity than bortezomib (BTZ) (*P < 0.05). In general, MLN2238 had similar ex-vivo cytotoxic activity as BTZ when primary cells were exposed to 5 nmol/l of drug for 48 h.

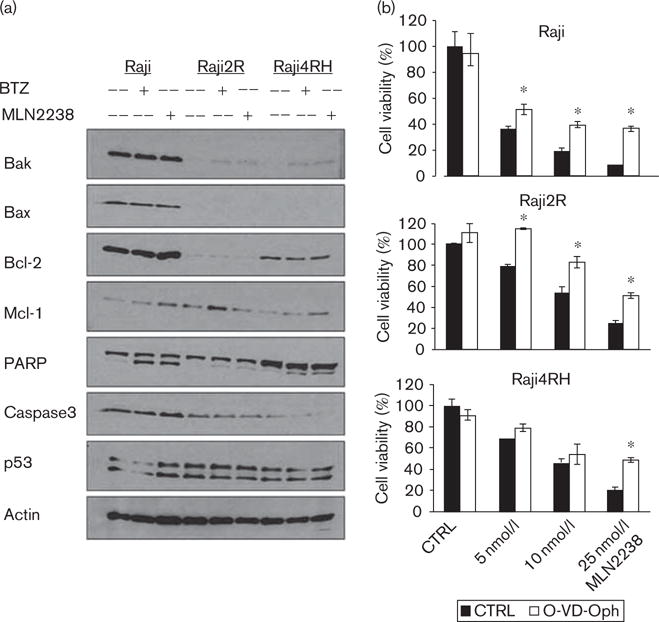

MLN2238 cytotoxic activity is partially abrogated by caspase inhibition in RSCL and to a lesser degree in RRCL

Preclinical studies have reported that BTZ shows several mechanisms of cytotoxic activity. We have reported previously that BTZ could induce cell death primarily through caspase-dependent programmed cell death (apoptosis) by increasing the expression of the proapoptotic proteins Bak, Bik, and Noxa in RRCL. However, BTZ also triggers cell death by a caspase-independent pathway(s), such as autophagy, irreversible cell cycle arrest, senescence, or mitotic catastrophe [18,20]. Therefore, we examined the cellular pathways responsible for MLN2238 cytotoxic activity. In-vitro exposure of RSCL and RRCL to MLN2238 resulted in induction of Bak, downregulation of Mcl-1, and induction of PARP cleavage (Fig. 3). Furthermore, caspase inhibition partially rescued RSCL and to a lesser degree RRCL exposed to MLN2238 (Fig. 3b). These findings were similar to BTZ, suggesting that both proteasome inhibitors have similar mechanisms of action. Caspase inhibition does not fully reverse MLN2238-associated cytotoxicity; caspase-independent mechanisms of cell death likely contribute toward its cytotoxic activity.

Fig. 3.

MLN2238 induces caspase-dependent cell death. (a) Western blotting showed altered proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins in rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines (RSCL) and rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (RRCL) after exposure to MLN2238 (10 nmol/l) or bortezomib (BTZ) (10 nmol/l) for 24 h. (b) Caspase inhibition by Q-VD-OPh partially reversed MLN2238-induced cell death. RSCL and RRCL were exposed in vitro to different doses of MLN2238 with or without a pan-caspase inhibitor (Q-VD-OPh 5 μmol/l). Cell viability was detected after 48 h of incubation. Data shown were the average of three independent experiments±SD *Significant difference (P < 0.05) between the O-VD-Oph treatment and the control (CTRL) group.

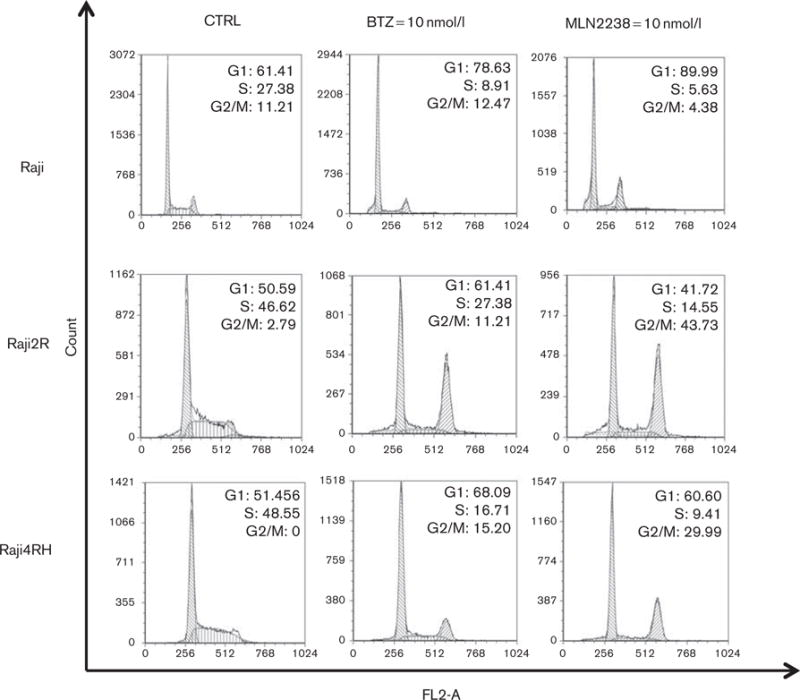

MLN2238 induces a G2/M cell cycle arrest in RRCL

BTZ is known to induce cell cycle arrest in solid tumors (e.g. prostate or lung cancer) and B-cell lymphoma preclinical models [21,22]. To determine whether MLN2238 has similar effects on the cell cycle of additional lymphoma cell lines, we exposed RSCL and RRCL to BTZ or MLN2238 and evaluated changes in cell cycle progression (Fig. 4). RSCL and RRCL had shown differences in cell cycle pattern after BTZ or MLN2238 exposure. In RSCL, an increased G1 phase and a decreased S phase were found following in-vitro exposure to BTZ or MLN2238. In contrast, in-vitro exposure of RRCL to either MLN2238 or BTZ resulted in an increase of cells in the G2/M phase. The percentage of change in the cell cycle was more pronounced in MLN2238-exposed lymphoma cells.

Fig. 4.

MLN2238 induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in rituximab-resistant but not rituximab-sensitive cells. Rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines and rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines were exposed to MLN2238 (10 nmol/l) or bortezomib (BTZ) (10 nmol/l) for 24 h. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry and differences in cell cycle between treated versus untreated cells were analyzed using the FCS express software.

MLN2238 resensitizes RRCL to the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy agents

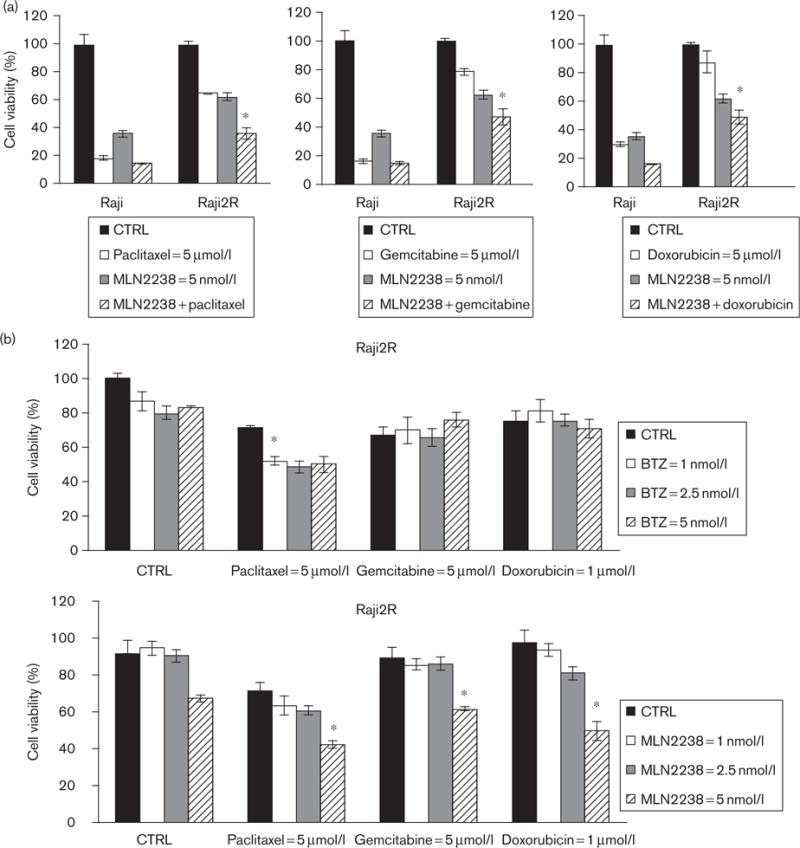

We have shown previously that repeated exposure of lymphoma cells to rituximab resulted not only in rituximab resistance but also cross-resistance to multiple chemotherapy agents, suggesting the existence of shared pathways of resistance [18]. In addition, there is emerging information from clinical trials suggesting that diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients failing or relapsing after standard rituximab-based immunochemotherapy induction (e.g. R-CHOP) show a higher degree of chemotherapy resistance in the salvage setting [23,24]. Preclinical studies suggested that BTZ can reduce the apoptotic threshold to chemotherapy agents and provided the basis for clinical trials combining BTZ with systemic chemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients [25,26]. Given the cellular effects observed in RSCL and RRCL exposed to MLN2238, we tested whether MLN2238 could decrease the apoptotic threshold to chemotherapy agents in RRCL. We selected chemotherapy agents that affect various phases of the cell cycle: paclitaxel (M phase) and gemcitabine (S phase), or that are non-cell cycle specific (doxorubicin) (Fig. 5). Of interest, MLN2238 enhanced the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy agents only in RRCL but not in RSCL.

Fig. 5.

Pretreatment of rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant cell lines (RRCL) with MLN2238 enhances the cytotoxic activity of chemotherapy agents. Cells were pre-exposed to MLN2238 or bortezomib at 1–5 nmol/l for 24 h; cells were then treated with paclitaxel (5 μmol/l), gemcitabine (5 μmol/l), or doxorubicin (1 μmol/l) for an additional 48 h. Cell viability was quantified. RRCL appears to be chemosensitized by MLN2238 at a 5 nmol/l preincubation dose; chemosensitization was not shown in rituximab-chemotherapy-sensitive cell lines (RSCL) (data not shown). Values represent the means of three independent experiments on three separate occasions±SD. Statistical significant indicated (*P < 0.05). CTRL, control.

Discussion

The UPS plays a pivotal role in the regulation of multiple cellular functions including cell death, cell proliferation, and differentiation. Deregulation of the UPS had been shown in numerous cancers and, more importantly, it has been shown to play a significant role in the development of rituximab-chemotherapy resistance in B-cell lymphoma [18].

The concept of targeting the UPS in lymphoid malignancies as therapeutic strategies has been partially hindered by drug-associated toxicities precluding the dose escalation of BTZ. Although BTZ has single-agent activity in MCL and a subset of follicular lymphoma patients, it appears less active as monotherapy in other NHL subtypes [27–29]. On the basis of preclinical models and early clinical trials, BTZ lowers the apoptotic threshold of chemotherapy drugs particularly and resensitizes lymphoma cells to the cytotoxic activity of chemotherapy agents. Ongoing clinical studies are aimed to further support the use of BTZ in combination with rituximab and chemotherapy agents in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. However, BTZ’s toxicity profile, especially BIPN, may be a major obstacle in the further clinical development of BTZ-chemotherapy-based regimens in aggressive lymphoma and underlying the necessity to develop proteasome inhibitors with better therapeutic indices.

MLN9708 is the first oral proteasome inhibitor to enter clinical studies and has shown antitumor activity in solid tumors and hematological malignancies [11,12,30]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first preclinical evaluation of its hydrolyzed form, MLN2238, in rituximab-sensitive and rituximab-resistant lymphoma cells. Our data show that MLN2238 has potent cytotoxic activity against RSCL and RRCL in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner. In contrast to BTZ, protracted exposure of MLN2238-induced cell growth arrest in RSCL and RRCL. In addition, MLN2238 appears to enhance the cytotoxic effects of both cell cycle-specific and nonspecific chemotherapy agents in RRCL.

At the cellular level, MLN2238 appears to have multiple mechanisms of action. Similar to BTZ, MLN2238 induces cell death by both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell pathways. MLN2238 induces caspase-dependent apoptosis, likely by upregulating Bak and decreasing Mcl-1 levels. In addition, MLN2238 induces cell cycle arrest in lymphoma cells. The effect of MLN2238 on the cell cycle of lymphoma cells was different between RSCL and RRCL, indicating the complexity of its mechanism(s) of action. Ongoing efforts are aimed to further characterize the effects of UPS inhibition following MLN2238 exposure and to determine the difference in the expression levels of key regulatory proteins of the cell cycle between RSCL and RRCL exposed to MLN2238.

When compared with BTZ in a preclinical model, MLN2238 has been reported to have better pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and antitumor activity properties in both plasma cell and lymphoid malignancy models [11,30]. Although BTZ and MLN2238 have similar reversible proteasome inhibition, the proteasome dissociation half-life (t1/2) of MLN2238 was found to be approximately six-fold faster than BTZ (t1/2 of 18 vs. 110 min, respectively). Cell viability studies have shown that MLN2238 has LD50 values similar to BTZ in a variety of cultured mammalian cancer cell lines (LD50 range 4–58 nmol/l) [12]. Our work shows that single-agent MLN2238 is approximately two to three times more potent than BTZ in lymphoma cell models. The IC50 of MLN2238 was 2.5 nmol/l in contrast to 7.5 nmol/l of BTZ in Raji parental cells. In addition, at 5 nmol/l preincubation dose of MLN2238 (but not BTZ) showed the ability to sensitize RRCL to various chemotherapy agents.

Besides the emergence of pharmacological resistance to BTZ, significant BIPN limits further dose escalation of BTZ. BIPN has been reported in at least 37% of patients treated with BTZ at maximum tolerated dose (MTD) 1.3 mg/m2 [31]. In early clinical trials, MLN9708 shows a lower incidence of peripheral neuropathy than BTZ controls. The results of the phase I study that aimed to define the MTDs of MLN9708, the precursor of MLN2238, in patients with relapsed and/or refractory MM were reported recently [32]. Lonial et al. [32] evaluated the MTD of MLN9708 administered orally twice a week in 57 patients with relapsed/refractory MM. In this particular study, the MTD of MLN9708 was 2.0 mg/m2 in a twice-weekly oral schedule and no dose limiting toxicities were observed. Moreover, peripheral neuropathy was observed only in 6% of the patients. In addition, pharmacokinetic studies indicated that MLN9708 showed linear plasma pharmacokinetic (0.8–2.23 mg/m2), Tmax of 0.5–1.25 h, and a terminal half-life of 4–6 days. Similar results were reported by Kumar et al. [33] in 36 patients with relapsed/refractory MM. In this study, the MTD of MLN9708 as a single agent administered weekly was 2.97 mg/m2. Only three patients reported drug-related peripheral neuropathy; all were grade 1 or 2. Data from the aforementioned clinical trials suggest that MLN2238 is well tolerated and has a lower incidence of neuropathy when compared with BTZ [32,33].

In summary, our results indicate that MLN2238 has significant cytotoxic activity in RSCL and RRCL preclinical models. MLN2238 is active in sensitizing RRCL to a variety of chemotherapy agents used commonly in the salvage therapy setting. Given the improved therapeutic index of MLN9708 on the basis of preclinical and data from phase I myeloma studies, it may be suitable for use in combination therapy regimens in relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Our observations provide in-vitro evidence for further evaluation of MLN9708 in combination with chemotherapy agents in relapsed/refractory lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

J.G., C.M., N.M.C., and R.P. performed the research; F.J.H.-I., J.G., M.S.C. designed the research study; J.G., J.J.S., and G.B. contributed essential reagents or tools; J.G., F.J.H.-I. analyzed the data; J.G., F.J.H.-I., M.S.C. wrote the paper.

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (targeting the proteasome to overcome therapy resistance; sponsor award number 5RO1CA136907-02) and the Eugene and Connie Corasanti Lymphoma Research Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

M.S.C. has served on an advisory board for Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc. For the remaining authors there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. EMBO J. 1998;17:7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams J. The proteasome: a suitable antineoplastic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:349–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeBlanc R, Catley LP, Hideshima T, Lentzsch S, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, et al. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits human myeloma cell growth in vivo and prolongs survival in a murine model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4996–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullard A. Next-generation proteasome blockers promise safer cancer therapy. Nat Med. 2012;18:7. doi: 10.1038/nm0112-7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer P, Hallek M. Hematological cancer in 2011: new therapeutic targets and treatment strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cvek B, Dvorak Z. The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) and the mechanism of action of bortezomib. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1483–1499. doi: 10.2174/138161211796197124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen D, Frezza M, Schmitt S, Kanwar J, Dou QP. Bortezomib as the first proteasome inhibitor anticancer drug: current status and future perspectives. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:239–253. doi: 10.2174/156800911794519752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argyriou AA, Iconomou G, Kalofonos HP. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Blood. 2008;112:1593–1599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavaletti G, Jakubowiak AJ. Peripheral neuropathy during bortezomib treatment of multiple myeloma: a review of recent studies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1178–1187. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.483303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EC, Fitzgerald M, Bannerman B, Donelan J, Bano K, Terkelsen J, et al. Antitumor activity of the investigational proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in mouse models of B-cell and plasma cell malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7313–7323. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupperman E, Lee EC, Cao Y, Bannerman B, Fitzgerald M, Berger A, et al. Evaluation of the proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in preclinical models of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1970–1980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assouline S, Chang J, Rifkin R, Hui AM, Berg D, Gupta N, et al. MLN9708, a novel, investigational proteasome inhibitor, in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma: results of a phase 1 dose-escalation study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts; December 2011; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 2672. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berdeja JG, Richardson PG, Lonial S, Niesvizky R, Hui AM, Berg D, et al. Phase 1/2 study of oral MLN9708, a novel, investigational proteasome inhibitor, in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma (MM). ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts; December 2011; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 479. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta N, Saleh M, Venkatakrishnan K. Flat-dosing versus BSA-based dosing for MLN9708, an investigational proteasome inhibitor: population pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis of pooled data from 4 phase-1 studies. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts; December 2011; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 1433. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Bensinger WI, Reeder CB, Zimmerman TM, Berenson JR, Berg D, et al. Weekly dosing of the investigational oral proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma: results from a phase 1 dose-escalation study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2011; December 2011; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 816. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson PG, Baz R, Wang L, Jakubowiak AJ, Berg D, Liu GH, et al. Investigational agent MLN9708, an oral proteasome inhibitor, in patients (PTS) with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM): results from the expansion cohorts of a phase 1 dose-escalation study. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts; December 2011; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olejniczak SH, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Clements JL, Czuczman MS. Acquired resistance to rituximab is associated with chemotherapy resistance resulting from decreased Bax and Bak expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1550–1560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czuczman MS, Olejniczak S, Gowda A, Kotowski A, Binder A, Kaur H, et al. Acquirement of rituximab resistance in lymphoma cell lines is associated with both global CD20 gene and protein down-regulation regulated at the pretranscriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1561–1570. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olejniczak SH, Blickwedehl J, Belicha-Villanueva A, Bangia N, Riaz W, Mavis C, et al. Distinct molecular mechanisms responsible for bortezomib-induced death of therapy-resistant versus -sensitive B-NHL cells. Blood. 2010;116:5605–5614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canfield SE, Zhu K, Williams SA, McConkey DJ. Bortezomib inhibits docetaxel-induced apoptosis via a p21-dependent mechanism in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2043–2050. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denlinger CE, Rundall BK, Keller MD, Jones DR. Proteasome inhibition sensitizes non-small-cell lung cancer to gemcitabine-induced apoptosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.029. discussion 1207–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thieblemont C, Briere J, Mounier N, Voelker HU, Cuccuini W, Hirchaud E, et al. The germinal center/activated B-cell subclassification has a prognostic impact for response to salvage therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a bio-coral study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4079–4087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagberg H, Gisselbrecht C. Randomised phase III study of R-ICE versus R-DHAP in relapsed patients with CD20 diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) followed by high-dose therapy and a second randomisation to maintenance treatment with rituximab or not: an update of the CORAL study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(Suppl 4):iv31–iv32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy N, Czuczman MS. Enhancing activity and overcoming chemoresistance in hematologic malignancies with bortezomib: preclinical mechanistic studies. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1756–1764. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright JJ. Combination therapy of bortezomib with novel targeted agents: an emerging treatment strategy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4094–4104. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coiffier B. Is bortezomib an effective treatment for indolent or mantle-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:388–389. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goy A, Younes A, McLaughlin P, Pro B, Romaguera JE, Hagemeister F, et al. Phase II study of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:667–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor OA, Wright J, Moskowitz C, Muzzy J, MacGregor-Cortelli B, Stubblefield M, et al. Phase II clinical experience with the novel proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:676–684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chauhan D, Tian Z, Zhou B, Kuhn D, Orlowski R, Raje N, et al. In vitro and in vivo selective antitumor activity of a novel orally bioavailable proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 against multiple myeloma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5311–5321. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broyl A, Jongen JL, Sonneveld P. General aspects and mechanisms of peripheral neuropathy associated with bortezomib in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:249–257. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lonial S, Baz RC, Wang M, Talpaz M, Liu GH, Berg D, et al. Phase I study of twice-weekly dosing of the investigational oral proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in patients (pts) with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM) [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:8017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Bensinger W, Reeder C, Reeder CB, Berenson JR, Berg D, et al. Weekly dosing of the investigational oral proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM): a phase I study [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:8034. [Google Scholar]