Abstract

The much studied plant Arabidopsis thaliana has been reported recently to react to the sounds of caterpillars of Pieris rapae chewing on its leaves by promoting synthesis of toxins that can deter herbivory. Identifying participating receptor cells—potential “ears”—of Arabidopsis is critical to understanding and harnessing this response. Motivated in part by other recent observations that Arabidopsis trichomes (hair cells) respond to mechanical stimuli such as pressing or brushing by initiating potential signaling factors in themselves and in the neighboring skirt of cells, we analyzed the vibrational responses of Arabidopsis trichomes to test the hypothesis that trichomes can respond acoustically to vibrations associated with feeding caterpillars. We found that these trichomes have vibrational modes in the frequency range of the sounds of feeding caterpillars, encouraging further experimentation to determine whether trichomes serve as mechanical antennae.

Introduction

The recent discovery by Appel and Cocroft (1) that leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana respond meaningfully to the noises of Pieris rapae caterpillars feeding on them raises the questions of what cells participate in the receptor system or systems, how they operate, and how they initiate responses. In Appel and Cocroft’s study, synthesis of several toxins was promoted by the feeding caterpillars, and the caterpillar activity could be effectively replaced by appropriate application of acoustic vibration directly to a leaf.

In principle, there are two ways in which the acoustic vibrations caused by the feeding caterpillars might be transmitted. First, they might be carried through the leaf and stem tissue. This is the primary way envisioned by Appel and Cocroft (1) for transmission through the plant under attack. Second, as tentatively suggested by Appel and Cocroft (1), they might be carried through the air, and thus carry warning messages to neighboring plants.

We focused on a possible role for Arabidopsis trichomes (hair cells) as acoustic detectors, and asked whether they have the form of tiny mechanical antennae for acoustic waves arising from herbivory by Pieris caterpillars. Thus, in principle they might have a role, either exclusive or contributory, in detecting caterpillars on the identical plant, but perhaps an exclusive role in receiving warning sounds from adjacent plants if indeed this can occur. The latter situation is of special interest, because if verified the detection of aerial sound waves conjures the agricultural possibility of acoustic pest control. Although Arabidopsis itself is of little interest in this regard, it is nevertheless a member of a large family containing many food and oil plants. Moreover, diverse kinds of trichomes are widely distributed in the plant world.

In part, our interest was piqued by our recent discoveries, mostly unpublished, that Arabidopsis trichomes can serve several mechanosensory functions. Of special pertinence is the observation that brushing or bending a trichome causes Ca2+ oscillations and lowering of wall pH in the skirt cells developmentally linked to the trichome, which are especially well connected to their distal neighbors by plasmodesmata (2).

Accordingly, we asked: is it quantitatively reasonable to speculate that trichomes could respond to sound waves? Specifically, can it be determined by formal simulation analysis whether the primary modal vibration frequencies, as determined by the mass, stiffness, and geometry of the trichome (3, 4, 5), are tuned to resonate when exposed to acoustic waves corresponding to frequencies in the power spectral density of feeding Pieris caterpillars?

If so, it would seem worthwhile to carry out the somewhat elaborate experiments required to assess actual trichome vibrations and check for some of the possible biochemical effects that might, speculatively, be triggered. This would strengthen the basis for studying the broader web of cells and pathways involved in detecting and deterring predatory caterpillars.

Materials and Methods

To study whether Arabidopsis trichomes are capable of transducing mechanical stimuli such as subtle, repeated vibrations produced by Pieris, we evaluated using finite-element and closed-form modal analysis whether an archetypal Arabidopsis trichome is capable of transducing vibrations in the frequency range associated with herbivory. To this end, a series of numerical simulations were performed on an archetypal trichome to establish modal responses. Because the material parameters have yet to be determined definitively for the components of Arabidopsis trichomes, parametric studies were performed to check the sensitivity of predictions to all parameter choices.

Finite-element discretization of a trichome

Analyses were performed on idealized trichomes using standard procedures (e.g., Ginsberg (6)). The trichome studied was that discretized by Zhou et al. (2), from confocal and ultraviolet microscopy images (Fig. 1). The gross outline of the trichome studied was obtained from a smoothing of the confocal microscopy images (such as Fig. 1 b), whereas the inner boundaries were acquired from ultraviolet microscopy images that penetrated the cell to show the thickness of the wall (Fig. 1 a). From these images, a 3D CAD rendering of the trichome was generated (Fig. 1 C) that was subsequently discretized from plate elements using the software Abaqus (Dassault Industries, Paris, France). Finite-element meshes were refined to ensure convergence of the predicted mode shapes and natural frequencies (Fig. S2). Following Zhou et al. (2), the subsurface region of the podium was omitted from consideration; as is standard in vibrational analysis of structures, the subsurface region was replaced with an effective elastic foundation (7, 8).

Figure 1.

Structures of natural and simulated Arabidopsis trichomes. (a) Given here is a UV microscopy image, showing interior wall taper. The bar is 20 μm. (b) Given here is a confocal microscopy image of a trichome stained with a pH bioreporter, tilted by compression from above. This image illustrates some of the considerable morphological variation that occurs, which was compensated by evaluating image stacks of trichomes with differing shapes. (c) Given here is a 3D illuminated rendering of the aerial portion of a trichome. (a and b) Reprinted with permission from Zhou et al. (2). To see this figure in color, go online.

For the purpose of building the model, the trichome was divided into five parts: three branches, the stalk, and their junction. A callose ring near the swelling at the base is a variable feature (9) so was not incorporated in the model; instead, it and the adjacent pliant zone were considered as part of the taper. The part of the podium embedded in leaf tissue (compare to Zhou et al. (10)) was modeled as part of an elastic foundation, as described below. The first four parts each had a well-defined axis of symmetry along a unit vector , with the index i = {1, 2, 3, 4} representing the stalk (index 1) and the three branches (indices 2–4). The cutting planes were defined perpendicular to symmetry axes, defined by vectors such that

| (1) |

where is the intersection of symmetry axis i and the associated cutting plane. For the three branches, properties were interpolated as a function of position xi along each symmetry axis, with xi measured from . The outer radii Ri(xi) of the three branches decreased conically from the junction so that . The outer boundaries of the junction and stalk were contoured according to the confocal microscopy images.

The walls of the branches and junction were given a thickness of 6.0 μm. Three separate models were investigated for the effect of stalk thickness, which the images in Fig. 1 and replicates showed to be tapered. In the first, the walls were set to the minimum observed thickness, tmin = 1.5 μm. In the second, the walls were set to the maximum observed thickness: tmax = 6.0 μm. In the third, the thickness was set to the observed parabolic function of height x1 along the stalk’s axis from its base to the base of the junction t(x1) = −(0.25 μm−1) x12 + 0.07 x1 + 0.0015 μm.

Mechanical properties

Mechanical properties were assigned for the cytosol, cell wall, and foundation of the trichome. Parameters chosen for finite-element simulation are listed in Table 1, including a basal set of fixed values as well as reasonable ranges of variation and sources of data. None of these mechanical properties are known with certainty, and parametric studies were therefore performed. Note that in some cases, parameter studies were performed well beyond the range of data to enable identifications of trends.

Table 1.

Range of Mechanical Properties Studied for Model Trichomes

| Symbol | Variable | Range of Data | Baseline Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ρwall | density of cell wall | Characean internode: 1.4 g/cm3 (43) | 1 g/cm3 |

| wood: 0.1–3 g/cm3 (44) | |||

| ρcyto | density of cytosol | Characean internode: 1.0 g/cm3 (43) | 1 g/cm3 |

| pollen tube: 1 g/cm3 (45) | |||

| t(x1) | thickness of tapered stalk cell wall | 1.5–6.5 μm (2) | See Materials and Methods |

| Ewall | Young’s modulus of cell wall | 0.5–4 GPa (20, 44, 46) | 1 GPa |

| EL | Young’s modulus of trichome foundation | 0.035–35 GPa (44) | 1 GPa |

| k | foundation stiffness | animal cells: 10−5–10−2 MPa/μm (24) | 1 MPa/μm |

| plant cells: 1–30 MPa/μm (see Materials and Methods) | |||

| νL | Poisson’s ratio of trichome foundation | 0.30–0.49 (47) | 0.33 |

| κcyto | bulk modulus of cytosol | 2.15 GPa (48, 49) | 2.15 GPa |

| P0 | turgor pressure of cell | 0.8–1.4 MPa (50) | 0.5 MPa |

| guard cells 0.5–5 MPa (51) |

Cytosol. Following procedures that are standard for piping systems with low Reynolds number (11), the cytosol was treated as an incompressible void with no shear resistance, and its mass was distributed to the neighboring cell wall. More complicated procedures are available that involve interactions between flowing fluid and pipe walls (11, 12, 13), nonlinear deformations including buckling of the walls (14, 15, 16, 17), and nonlinearity of the fluid within the cytosol (18, 19), but these were not needed for cytosol contained in the relatively narrow channels of the trichome stalk and branches undergoing acoustic loading. The relative amounts of cytoplasm and cell wall material varied along the length of the roughly conical trichome arms and contoured trichome stalk. To account for this, the effective density of the arm, ρ, was varied with the position along the stalk or branches, as

| (2) |

where ρcyto is the effective density of the cell wall, and ρwall is that of the cell wall. For the junction between the branches and stalk, the effective wall density was amplified according to

| (3) |

where Vcyto ≈ 2.3 × 10−14 m3 and Vwall ≈ 7.8 × 10−15 m3 are the volumes enclosed within the CAD model of the junction and the volume of cell wall at the junction, respectively, with the latter estimated using a wall thickness of t = 1.5 μm.

The cytosol was pressurized with a baseline pressure of 0.5 MPa. Pressures in the range of 0.1–1.0 MPa were studied.

Cell wall. The cell wall was treated as linear elastic and isotropic with an elastic modulus of 1 GPa and a Poisson ratio of 0.33 (Table 1). The 1 GPa cell wall modulus of Characean algae cells was chosen as a reference modulus because the cells have a thick primary wall (20) that may be comparable to that of the trichome in several ways.

Foundation. The foundation of the trichome stalk was treated as deformable and linear elastic. The leaf was thus modeled with a Winkler-type foundation having an elastic stiffness k per unit area, so that the displacement Δx of a point on the base of the trichome was given by

| (4) |

where is the component of stress (force per unit area) on the basal plane of the model trichome that is directed parallel to the axis of the trichome stalk, at position and time t. The order of magnitude of k was estimated from the solution presented by Johnson (21) to the Love (22) problem of a uniform pressure σ0 distributed over a circular region on the free boundary of an elastic half-space of elastic modulus E and Poisson ratio ν. Considering the peak displacement in such a case, occurring at the center of the circular region, results in the estimate (23),

| (5) |

where EL and νL are the effective elastic modulus and Poisson ratio of the foundation, respectively; and R = 20 μm is the radius of the trichome. Taking EL ∼ 0.03–1 GPa and νL ∼ 0.33 and inserting R yields the order-of-magnitude estimate k ∼ 1–30 MPa/μm. Note that this is approximately four orders-of-magnitude greater than the foundation stiffness typical for an animal cell (24) because of the presence of cell walls in the ring of cells that surround the podium.

Finite element analysis

Modal analysis was performed using standard linear modal analysis. Briefly, finite-element modal analysis was performed to analyze free vibrations of the trichome structure. The generalized equation of motion for a discretized structure was analyzed:

| (6) |

where M is a matrix of effective nodal masses, U(t) is a vector of nodal displacements, K is a matrix of effective stiffnesses, F(t) is a vector of applied forces, and t is time. The patterns of free vibration that an acoustic wave would excite are the vectors U(t) that satisfy the homogenous version of the differential equation with the form U(t) = U0 exp(iωt), where , U0 represents mode shape, and ω represents the associated natural frequencies. Substituting these into the homogenous form of Eq. 6 results in the well-known modal analysis eigenvalue equation that can be solved to find U0 and ω:

| (7) |

These vibrational modes U0 represent the shapes of vibration that will be excited by acoustic loading transmitted through the air or the leaf. The trichomes were discretized into meshes of ∼14,000 linear quadrilateral shell elements, and vibrational modes were found. A typical simulation required 3 min of CPU time on a Core Duo (Intel, Santa Clara, CA) desktop computer with 8 GB of RAM.

Closed-form scaling laws

Although structures composed of multiple and branching vibrating elements have modal responses that differ substantially from those of the individual branches (25), two scaling laws for the vibration of simple structures proved useful for interpreting the natural frequencies of the trichomes. The first is the Wrinch (26) solution for free vibration of a conical beam that is clamped at the thick end and free at the pointed end. Wrinch showed that the natural frequency fi corresponding to the ith vibrational mode of such a beam is

| (8) |

where Ewall is the Young’s modulus, ρ is the effective density, R0 is the maximum radius of the trichome, L is the length of the trichome, and βi = {8.72, 21.2, 38.5, 60.7, 88.9…} are the roots of

| (9) |

in which Ji is the Bessel function of the first kind of order i, and Ii is the modified Bessel function of the first kind of order i.

The second is the classic solution for torsional oscillation of a rigid object at the end of a thin, torsional shaft (6). Approximating the trichome shaft as a uniform rod of height H, thickness t, outer radius R1, and shear modulus E/2(1 + ν), the torsional rigidity of the stalk can be approximated as

| (10) |

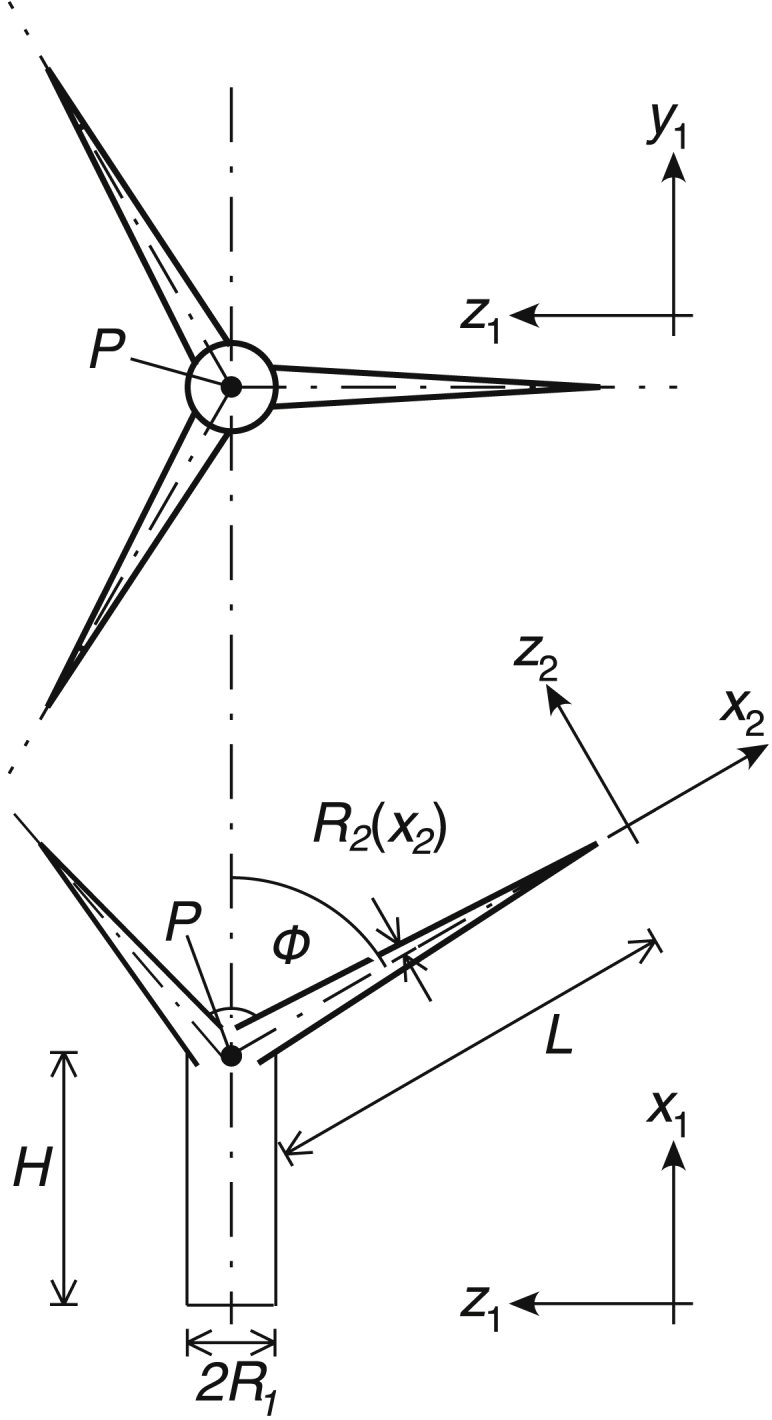

Idealizing a trichome branch as a solid, rigid cone as in Fig. 2, the inertia tensor about the vertex P, in the (x2, y2, z2) coordinate system, is (27)

| (11) |

where and , in which M = πρLR02/3 is the mass of a cone of density ρ. Transforming this tensor by an angle to the (x2, y2, z2) coordinate system (Fig. 2), adding the contributions of three branches, and finding the xx component of the resulting tensor, yields the moment of inertia of the branches about the stalk axis:

| (12) |

The natural frequency of the lowest torsional mode is

| (13) |

Figure 2.

Schematic of a model to predict the order of magnitude of the natural frequency for torsional oscillations occurring about the trichome stalk axis.

Spectral analysis of Pieris feeding noises

To determine the range of frequencies over which an acoustic response would be meaningful, we estimated the frequency-dependent power spectral density in four recordings of Pieris feeding upon Arabidopsis leaves, provided by Rex Cocroft (1). Periodogram estimates were made using a standard algorithm in the MATLAB computing environment (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Feeding sounds were sampled at 44.1 kHz and saved as .wav files.

Results

When receiving an acoustic stimulus, the first mode of vibration of the trichome with baseline parameters involved torsion of the stalk, with the branches rotating almost as a rigid body (Fig. 3; Movie S1). Higher modes involved rocking of the trichome (Fig. 3, mode 2; Movie S2) and various patterns of swinging branches (Fig. 3, higher modes; Movies S3, S4, and S5).

Figure 3.

The first eight mode shapes for an archetypal trichome. The lowest mode involved torsion about the stalk axis, and the next modes involved flexure and distension of the stalk. In higher modes, flexure of the branches was observed. Modal shapes are better visualized through animations provided in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5. To see this figure in color, go online.

The frequency of the first mode of vibration was a relatively weak function of the Young’s modulus of the wall. For the baseline case of Ewall = 1 GPa (Fig. 4 B), the first mode was excited at ∼6 kHz, well within the audible range (∼20–20,000 Hz), and well within the range for which Pieris feeding noises present substantial power (below ∼8 kHz, Fig. S3). The higher modes were much more sensitive to the choice of Ewall, with characteristic frequencies out of the human audible range for the baseline parameters (Table 1). This is consistent with the behavior of individual branches predicted from closed-form solutions, with characteristic frequencies in the tens of kHz range. For all choices of Ewall > 300 MPa, the first mode was the torsional mode. For a cell wall, 1/10th that of the baseline parameter choice (Fig. 4 A), the first mode was a rocking mode, and the first four modes all occurred at ∼10 kHz.

Figure 4.

The lowest vibrational mode was torsional for the baseline parameters of the archetypal trichome (dashed vertical line: baseline Young’s modulus). The character and natural frequency for the first mode were largely insensitive to Young’s modulus over approximately two orders of magnitude in the vicinity of the baseline Young’s modulus. For very low Young’s modulus, the first mode switched from the torsional mode to the flexural mode shown in position (A). To see this figure in color, go online.

The lowest natural frequency of the trichome depended strongly on the mechanics of the leaf foundation (Fig. 5). The torsional vibrational mode observed for trichomes with the baseline parameters switched to a rocking mode at sufficiently low foundation compliance.

Figure 5.

The mechanics of the leaf foundation was a strong determinant of the lowest natural frequency of the trichome. High compliance caused a switch from the torsional vibration mode to a rocking mode. The baseline parameters (dashed vertical line) provided a peak in the frequency, indicating that subtle changes such as pH-induced compliance could be used to trigger enhanced sensitivity to low frequency acoustic signals. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although higher modes were not sensitive to turgor pressure, the characteristic frequency of the first mode of vibration varied almost linearly with turgor pressure (Fig. 6). Note that the fourth and fifth modes are not visible on Fig. 6 because they occurred at frequencies above 100 kHz.

Figure 6.

The natural frequencies of the archetypal trichome decreased with decreasing turgor pressure. (Vertical dashed line) Baseline parameters. To see this figure in color, go online.

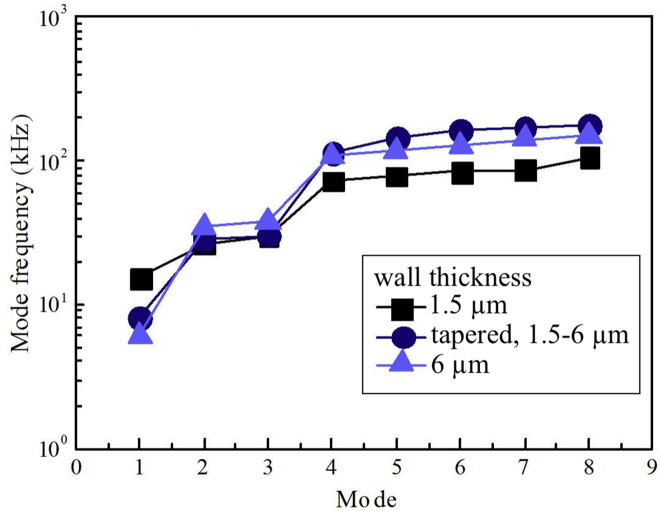

The choice of trichome stalk thickness model did not affect the trends or the magnitudes of the characteristic frequencies significantly (Fig. 6). In all cases, the first mode occurred well within the audible range, and the second mode at the upper extremity or just beyond the audible range. The choice of wall thickness profile did not affect the modal frequencies strongly (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effects of cell wall taper on the natural frequency of a trichome. The choice of model for the wall taper affected frequencies by up to a factor of 2, but did not affect trends. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Modeling an archetypal Arabidopsis trichome by both classical and finite-element analyses, we found that it has resonant modes responsive to acoustical waves in the range of insect feeding noise reported by Appel and Cocroft. For each vibration mode, Fig. 2 shows that trichomes respond in a characteristic way to vibrational stimulation. The first mode of vibration, a torsional mode in which the branches rotated around the axis of the stalk, was excited in the archetypal trichome at a frequency of ∼8 kHz. Within the range of parameters considered to be physiological, this frequency was accurate to within a tolerance on the order of 50%. Higher frequency modes involving rocking of the trichome stalk and waving of the trichome branches were excited toward the upper end of the audible range and beyond.

Comparison to closed-form estimates clarifies the nature of these mode shapes. For a torsional oscillator on a narrow stalk (R1 = 10 μm) of height H = 230 μm (adjusted to reach the center of the junction) connected to rigid conical branches of length L = 180 μm and maximum radius R0 = 10 μm, with all other parameters as in Table 1, torsional vibrations occurred on the order of 30 kHz for an angle ranging from 60° to 90°, indicating that additional aspects of the trichome contributed to the somewhat lower frequencies estimated by finite-element analysis. The transverse vibration frequency of the trichome branches occurred in frequency ranges on the order of MHz, also in agreement with finite-element prediction. This indicates that the motion of branches observed in lower frequency modes involved rocking of the trichome stalk rather than vibration of branches.

Although the shapes and walls of Arabidopsis trichomes can be quite variable, establishing baseline data in the simulations of Fig. 3 enables observing the consequences of varying the values of the baseline parameter set one at a time, and consideration of the extent to which evolution may have optimized the trichome for function as a mechanical antenna.

The same methodology was used to explore the consequences of each tested value; the Supporting Material illustrates how the parameters control movement patterns. One of the most distinctive properties of the wall of the trichome is its taper. Yet, untapered mutants have been identified (e.g., the EXO70H4-1 mutant, which lacks a secondary trichome wall and hence a taper in the trichome stalk (9)). The parametric study shown in Fig. 6 indicates that, although the taper affects the frequency response quantitatively, it does not affect trends and, over the range of limiting cases considered, cannot preclude the existence of a torsional vibrational mode within the range of frequencies that feature prominently in Pieris feeding noises.

Given on the one hand that the leaf as a whole can respond mechanically and physiologically to caterpillar feeding noise (1) and on the other hand that the trichome has the appearance of a mechanical antenna and is small in size, the finding that the archetypal trichome studied resonates in the audible range is perhaps unsurprising. Nevertheless, it has important implications.

One obvious implication is that the data warrant an experimental search for trichome vibration modes and biochemical consequences. Because these responses are extraordinarily complex, such a search must be carefully planned to discriminate between responses in the trichome itself and responses in the majority of the leaf tissue. In such planning, it must be recognized that, although the magnitudes of responses cannot be estimated from these analyses, any response by the leaf per se to air-borne sound will likely be small compared to possible response of the light-weight trichomes, even though response driven by piezoelectric actuators or by transmission via an aqueous path from another leaf (1) might be reasonably large.

Among responses observed within the somewhat similar trichome of bean plants to light brushing of its surface is production of (toxic) reactive oxygen species (W.Q. Gao and L. Zhou, personal communication); within the Arabidopsis trichome itself a rapid outward-moving acidification of the bulk of the wall and acidification of the thin papillae walls have been observed (unpublished). Stronger brushing can produce plastic deformation of the papillae, which could influence the behavior of their distinctive and likely toxic contents (unpublished). Among signaling consequences to surrounding cells from brushing a trichome stalk are acidification of cell walls and initiation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations in the skirt cells (2) and, for bean plants, the production of extractable anthocyanin in the bulk leaf (W.Q. Gao and L. Zhou, personal communication). On the other hand, responses described for acoustic stimulation of the entire leaf include increased anthocyanin and glucosinolate production (1), and doubtless a variety of volatiles ((1); see also (28)). The production of glucosinolate is reported to be primed rather than promoted directly (1). The complexity of interpreting glucosinolate levels is underlined by the observation they vary dramatically on a circadian basis that correlates with the timing of insect activity (29, 30).

Mechanoresponses such as gravitropism, thigmotropism, mechanotropism, gravinasty, thigmonasty, gravimorphogenesis, thigmomorphogenesis, mechanomorphogenesis, and mechanocontrol of biochemical pathways—somewhat overlapping terms among a plethora of such terms—are among the most-studied responses plants make to the environment (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37). The most popular comparisons to be made with the results of our acoustic assessments are probably those with functions of popular carnivores in the Droseraceae. Indeed, certain fascinating mechanosensory behaviors of conspicuously evolved Droseraceous trichomes were famously described over a century ago, such as the triggering of the rapid and slow leaf movements and glandular secretion by Dionaea or Venus flytrap (36, 37, 38) and the rapid tentacle movements followed by slower secretions and leaf movements by mechanically stimulated Drosera or sundew (38, 39). Action potentials were concurrently described as mediating these capturing and digesting behaviors in Dionaea (36, 37, 38) and later found to participate similarly in Drosera (38, 39, 40, 41, 42). Beyond such popular subjects, mechanostimulated secretions that attract pollinators or deter herbivores have been casually observed over the years in a variety of plants, but more critically, for Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) a recent detailed description (43, 44, 45) of mechanically induced secretion of defensive compounds by trichomes as well as changes mechanically elicited in leaf chemistry provides a welcome focus that should inspire further investigation, especially in view of more general earlier investigations on mechanical stimulation of tomato (35).

Perhaps most convincing that acoustic detection might have evolved in Arabidopsis trichomes, however, is our above-mentioned report of a variety of mechanoresponses by the Arabidopsis trichome itself (2), as well as our unpublished demonstrations of several kinds of signals elicited by brushing these trichomes. Such findings with Arabidopsis argue that its family might be more likely to evolve acoustic sensitivity than the Droseraceae, particularly because, in addition to sharing the general properties of mechanoresponse and secretory activity, the latter have elaborate electrical activities apparently absent in the former.

However, although responses to sound have been studied and speculated on sporadically over the past half century (33), attention to them has expanded slowly, and most studies concentrated on developmental effects rather than the acoustic response to detect and deter herbivory that was pioneered by Appel and Cocroft (31, 32, 33, 34, 35).

It may help in analyzing ultimate sequalae of caterpillar feeding noise to recognize that the transduction from mechanical distortion to chemical signal is likely accomplished by stretch-sensitive channels, as is often the case for plant mechanoresponses (31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38). We suspect the multimodally modulated mechanosensory Ca2+-selective ion channels described most extensively in cell membranes of onion bulb scale and leaf epidermis (39, 40, 41); apparently the same or closely similar channels exist in guard cells of bean leaves (42). For the vibrations studied by Appel and Cocroft, there is certainly heuristic evidence for participation of some kind of mechanosensory channel: noise was pulsed as caterpillars chewed, moved, rested, and resumed chewing. Stimulation by surrogate sound was defensively effective only if it was similarly pulsed. Quite generally, mechanosensitive channels are rapidly desensitized but soon resensitized by an interval of rest after stimulation.

Nonetheless, the elaborate structure and composition of the trichome wall (which we are currently studying) suggest some mechanotransductive activities elicited directly by papillar distortion, independent of channels. This possibility is underscored by our interpretation that the standard classification of the Arabidopsis trichome as nonsecretory overlooks the massive secretion by the wall system into its papillae concurrent with thinning of the papillar wall, and that the range of these papilla-specific secretions differ from the range of toxins measured in the experiments of Appel and Cocroft (1).

Finally, the results suggest what features of the leaf might be most effectively tuned to enable response to specific frequencies. Two features emerge as especially interesting when viewed through the lens of this study. First, it is interesting that the trichome wall has evolved specialized thickness and taper. As previously reported, the taper promotes force transfer and focusing to the skirt of cells surrounding the bulbous proximal end of the trichome, in which calcium and pH signaling are initiated (2). Given the torsional nature of the first mode, it is clear that the specialized outer contour is a simple factor that can be evolved to tune the torsional rigidity and hence frequency of response. Second, it is also noteworthy that the springiness of the trichome foundation is a key determinant of acoustic sensitivity (Fig. 5), suggesting that subtle changes such as pH-induced compliance could be used to trigger enhanced sensitivity to low frequency acoustic signals. Given that the bulk leaf is already known to vibrate at acoustic frequencies during caterpillar feeding (1), basal and trichome vibrations could work together to attune a plant to a specific acoustic signal.

We conclude by amplifying the idea that vibrational stimulation of Arabidopsis trichomes might combine with other stimuli associated with insect herbivory to trigger plant defenses. The sensitivity of the frequency response to the stiffness of the tissue beneath the trichome base provides a mechanism by which the plant can tune trichome acoustic response via stiffness altering factors such as Ca2+ concentrations, pH, and transmembrane voltage. Mechanical stimuli associated with herbivory begin with moths alighting and tapping the leaves with their antennae and tarsi, which doubtless stimulates both epidermal tissue and trichomes, and continue through the hatching of eggs and the onset of herbivory. Our earlier results (2) showing mechanoresponses including pH shifts in trichome and skirt cells abutting the trichome podium, and showing [Ca2+] oscillations in the skirt cells, indicate that perturbations during ovipositing might be capable of providing sensitizing signals to the trichomes or the bulk of the leaf. This work suggests that a broad study of integrated responses to vibration and allied stimuli should yield insight into the mechanisms by which Arabidopsis senses and distinguishes among sounds and then undertakes reactions to them.

Author Contributions

S.L. and J.J. performed mathematical simulations under the direction of T.J.L., F.X., B.G.P., and G.M.G. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under grant CMMI-1102803 to B.G.P. and G.M.G.; Glenn Allen through a gift to the Gladys Levis Allen Laboratory of Plant Sensory Physiology, by the China Scholarship Council to Study Abroad to S.L.; by the Chinese Ministry of Education through a Changjiang Scholar Award to G.M.G.; by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants 11372243, 11532009, and 11522219 to T.J.L. and F.X.; and by the National Science Foundation Center for Engineering Mechanobiology under grant CMMI 1548571.

Editor: Nathan Baker.

Footnotes

Three figures and nine movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30989-X.

Contributor Information

Barbara G. Pickard, Email: pickard@wustl.edu.

Guy M. Genin, Email: genin@wustl.edu.

Supporting Material

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For movies, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For movies, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

Vibration mode 1 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 10 GPa). Note that the mode shape was identical to the first mode shape of the baseline trichome shown in Movie S1.

Vibration mode 2 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 10 GPa). Note that the mode shape was identical to the second mode shape of the baseline trichome shown in Movie S2.

Vibration mode 1 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 0.1 GPa). Note that for these parameters, a flexural, rocking mode was mode 1, and a torsional mode was mode 2; this is in contrast to the baseline trichome shown in Movies S1 and S2, where the first mode was a torsional mode.

Vibration mode 2 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 0.1 GPa). Note that for these parameters, a flexural, rocking mode was mode 1, and a torsional mode was mode 2; this is in contrast to the baseline trichome shown in Movies S1 and S2, where the first mode was a torsional mode.

References

- 1.Appel H.M., Cocroft R.B. Plants respond to leaf vibrations caused by insect herbivore chewing. Oecologia. 2014;175:1257–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00442-014-2995-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou L.H., Liu S.B., Pickard B.G. The Arabidopsis trichome is an active mechanosensory switch. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;40:611–621. doi: 10.1111/pce.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsberg J.H. Springer; New York, NY: 2017. Acoustics—A Textbook for Engineers and Physicists. Volume I: Fundamentals. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsberg J.H. Springer; New York, NY: 2017. Acoustics—A Textbook for Engineers and Physicists. Volume II: Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xin F.X., Lu T.J. Analytical modeling of fluid loaded orthogonally rib-stiffened sandwich structures: sound transmission. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2010;58:1374–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginsberg J.H. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2001. Mechanical and Structural Vibrations: Theory and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacBain J.C., Genin J. Effect of support flexibility on the fundamental frequency of vibrating beams. J. Franklin Inst. 1973;296:259–273. [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacBain J.C., Genin J. Natural frequencies of a beam considering support characteristics. J. Sound Vibrat. 1973;27:197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulich I., Vojtíková Z., Žárský V. Cell wall maturation of Arabidopsis trichomes is dependent on exocyst subunit EXO70H4 and involves callose deposition. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:120–131. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou L.H., Weizbauer R.A., Pickard B.G. Structures formed by a cell membrane-associated arabinogalactan-protein on graphite or mica alone and with Yariv phenylglycosides. Ann. Bot. 2014;114:1385–1397. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesmez M.W., Wiggert D.C., Hatfield F.J. Modal analysis of vibrations in liquid-filled piping systems. J. Fluids Eng. 1990;112:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatfield F.J., Wiggert D.C., Otwell R.S. Fluid structure interaction in piping by component synthesis. J. Fluids Eng. 1982;104:318–325. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ting E.C., Hosseinipour A. A numerical approach for flow-induced vibration of pipe structures. J. Sound Vibrat. 1983;88:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonçalves P.B., Batista R.C. Non-linear vibration analysis of fluid-filled cylindrical shells. J. Sound Vibrat. 1988;127:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radwan H.R., Genin J. Nonlinear vibrations of thin cylinders. J. Appl. Mech. 1976;43:370–372. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radwan H.R., Genin J. Dynamic instability in cylindrical shells. J. Sound Vibrat. 1978;56:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moussaoui F., Benamar R. Non-linear vibrations of shell-type structures: a review with bibliography. J. Sound Vibrat. 2002;255:161–184. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xin F.X., Lu T.J. A nonlinear acoustomechanical field theory of polymeric gels. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2010;32:1374–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xin F., Lu T.J. Acoustomechanical constitutive theory for soft materials. Acta Mechanica Sinica. 2016;32:828–840. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Probine M.C., Preston R.D. Cell growth and the structure and mechanical properties of the wall in internodal cells of Nitella opaca: II. Mechanical properties of the walls. J. Exp. Bot. 1962;13:111–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson K.L. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. Contact Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love A.E.H. The stress produced in a semi-infinite solid by pressure on part of the boundary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A. 1929;228:377–420. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubarda V.A. Circular loads on the surface of a half-space: displacement and stress discontinuities under the load. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013;50:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deshpande V.S., McMeeking R.M., Evans A.G. A bio-chemo-mechanical model for cell contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14015–14020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605837103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genin J., Maybee J.S. Mechanical vibration trees. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1974;45:746–763. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrinch D. On the lateral vibrations of bars of conical type. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A. 1922;101:493–508. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsberg J.H., Genin J. Wiley; New York, NY: 1977. Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snoeren T.A.L., Kappers I.F., Bouwmeester H.J. Natural variation in herbivore-induced volatiles in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:3041–3056. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodspeed D., Chehab E.W., Covington M.F. Arabidopsis synchronizes jasmonate-mediated defense with insect circadian behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:4674–4677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116368109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodspeed D., Liu J.D., Braam J. Postharvest circadian entrainment enhances crop pest resistance and phytochemical cycling. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coutand C. Mechanosensing and thigmomorphogenesis, a physiological and biomechanical point of view. Plant Sci. 2010;179:168–182. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moulia B., Coutand C., Julien J.-L. Mechanosensitive control of plant growth: bearing the load, sensing, transducing, and responding. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:52. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telewski F.W. A unified hypothesis of mechanoperception in plants. Am. J. Bot. 2006;93:1466–1476. doi: 10.3732/ajb.93.10.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monshausen G.B., Haswell E.S. A force of nature: molecular mechanisms of mechanoperception in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:4663–4680. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chehab E.W., Wang Y., Braam J. Mechanical Integration of Plant Cells and Plants. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. Mechanical force responses of plant cells and plants; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton E.S., Schlegel A.M., Haswell E.S. United in diversity: mechanosensitive ion channels in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:113–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abeles F.B., Morgan P.W., Saltveit M.E. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. Ethylene in Plant Biology; pp. 264–296. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braam J. In touch: plant responses to mechanical stimuli. New Phytol. 2005;165:373–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding J.P., Pickard B.G. The 10th International Biophysics Congress. Biophysical Society of Canada; Vancouver, Canada: 1990. Ca2+ channel (from onion epidermis) sensitive to stretch and voltage, and regulated by mural Ca2+ levels; p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding J.P., Pickard B.G. Modulation of mechanosensitive calcium-selective cation channels by temperature. Plant J. 1993;3:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding J.P., Pickard B.G. Mechanosensory calcium-selective cation channels in epidermal cells. Plant J. 1993;3:83–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cosgrove D.J., Hedrich R. Stretch-activated chloride, potassium, and calcium channels coexisting in plasma membranes of guard cells of Vicia faba L. Planta. 1991;186:143–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00201510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wayne R., Staves M.P. The density of the cell sap and endoplasm of Nitellopsis and Chara. Plant Cell Physiol. 1991;32:1137–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson L.J. The hierarchical structure and mechanics of plant materials. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2012;9:2749–2766. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroeger J.H., Daher F.B., Geitmann A. Microfilament orientation constrains vesicle flow and spatial distribution in growing pollen tubes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nezhad A.S., Packirisamy M., Geitmann A. In vitro study of oscillatory growth dynamics of Camellia pollen tubes in microfluidic environment. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013;60:3185–3193. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2270914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chanliaud E., Burrows K.M., Gidley M.J. Mechanical properties of primary plant cell wall analogues. Planta. 2002;215:989–996. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0783-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorsey N.E. Reinhold; New York, NY: 1940. Properties of Ordinary Water Substance. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y., Thomopoulos S., Genin G.M. Modelling the mechanics of partially mineralized collagen fibrils, fibres and tissue. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2013;11:20130835. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Forouzesh E., Goel A., Turner J.A. In vivo extraction of Arabidopsis cell turgor pressure using nanoindentation in conjunction with finite element modeling. Plant J. 2013;73:509–520. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franks P.J., Buckley T.N., Mott K.A. Guard cell volume and pressure measured concurrently by confocal microscopy and the cell pressure probe. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1577–1584. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For movies, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For movies, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

The color scale shows normalized displacement; shadowing was added to aid interpretation of 3D motions. For Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5, the baseline parameters were used (please refer to Table 1), including a cell wall modulus of Ewall = 1 GPa.

Vibration mode 1 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 10 GPa). Note that the mode shape was identical to the first mode shape of the baseline trichome shown in Movie S1.

Vibration mode 2 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 10 GPa). Note that the mode shape was identical to the second mode shape of the baseline trichome shown in Movie S2.

Vibration mode 1 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 0.1 GPa). Note that for these parameters, a flexural, rocking mode was mode 1, and a torsional mode was mode 2; this is in contrast to the baseline trichome shown in Movies S1 and S2, where the first mode was a torsional mode.

Vibration mode 2 of a trichome with the baseline parameters used in Movies S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5 (please refer to Table 1), except with a cell wall modulus ten times stiffer (Ewall = 0.1 GPa). Note that for these parameters, a flexural, rocking mode was mode 1, and a torsional mode was mode 2; this is in contrast to the baseline trichome shown in Movies S1 and S2, where the first mode was a torsional mode.