Abstract

How calmodulin (CaM) acts in KRAS-driven cancers is a vastly important question. CaM binds to and stimulates PI3Kα/Akt signaling, promoting cell growth and proliferation. Phosphorylation of CaM at Tyr99 (pY99) enhances PI3Kα activation. PI3Kα is a lipid kinase. It phosphorylates PIP2 to produce PIP3, to which Akt binds. PI3Kα has two subunits: the regulatory p85 and the catalytic p110. Here, exploiting explicit-solvent MD simulations we unveil key interactions between phosphorylated CaM (pCaM) and the two SH2 domains in the p85 subunit, confirm experimental observations, and uncover PI3Kα’s mechanism of activation. pCaMs form strong and stable interactions with both nSH2 and cSH2 domains, with pY99 being the dominant contributor. Despite the high structural similarity between the two SH2 domains, we observe that nSH2 prefers an extended CaM conformation, whereas cSH2 prefers a collapsed conformation. Notably, collapsed CaM is observed after binding of an extended CaM to K-Ras4B. Thus, the more populated extended pCaM conformation targets nSH2 to release its autoinhibition of p110 catalytic sites. This executes the key activation step of PI3Kα. Independently, K-Ras4B allosterically activates p110. These events are at the cell membrane, which contributes to tighten the PI3Kα Ras binding domain/K-Ras4B interaction, to accomplish K-Ras4B allosteric activation, with a minor contribution from cSH2.

Introduction

Calcium is a versatile ion that contributes to cross talk among cellular signaling pathways to accomplish multiple biological functions including cellular differentiation (1), proliferation (2), and apoptosis (3). Disruption of intracellular calcium homeostasis promotes diseases, including diabetes (4), cardiovascular diseases (5), and cancers (6, 7). The primary mediator and signaling messenger of calcium in eukaryotic cells is calmodulin (CaM) (8, 9). CaM is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells, regulating inflammation (10), metabolism (11), apoptosis (12), smooth muscle contraction (13), cellular movement (14), memory (15, 16), and immune response (17). Calcium activates PI3K by converting CaM (and phosphorylated CaM, pCaM) from an inactive to an active state. Elevated calcium levels in cells increase the population of activated CaM, thereby contributing to PI3K activation. Without calcium ions, apo-CaM exhibits a bent conformation with the hydrophobic cores buried. Upon binding to calcium, CaM undergoes a conformational change to an extended state and gets activated (holo-CaM), exposing the hydrophobic cores in the C- and N-lobes. Extended CaM has a symmetric conformation, with two lobes (the N-lobe and C-lobe) connected by the flexible linker. Each lobe has two EF-hand motifs that individually load one calcium ion. A total of four calcium ions are bound by each CaM at residues 21–32, 57–68, 94–105, and 130–141, respectively. The flexible linker is crucial for CaM to accommodate a wide range of target proteins, making CaM capable of wrapping around target proteins (18, 19) and establishing strong interactions to mediate signaling pathways (20). Upon binding to specific target proteins, CaM can also adopt a collapsed conformation as has been observed in many crystal structures (19). In collapsed CaM, the linker region usually exhibits a twist, leading to additional interactions between the two lobes, making CaM more compact.

Recent literature pointed out that CaM is involved in tumorigenesis by promoting phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt proliferative signaling pathways (21, 22, 23). PI3K is a key signal transducer enzyme in the cell (24), controlling cell proliferation in response to growth factors, cytokines, and other stimuli (25). Activated PI3Kα triggers cell proliferation signaling pathways by producing phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-tris-phosphate (PIP3) in plasma membranes (26, 27, 28, 29). With CaM’s assistance (30), PIP3 stimulates the translocation of Akt from solution to the plasma membrane (31). PIP3 binding elicits a conformational change that exposes the phosphorylation sites (S473 and T308). Phosphorylation by PDK (or other) kinases promotes proliferation and decreases apoptosis (32). Overactivation of PI3Kα leads to abnormal cellular proliferation, which can result in cancer (33, 34), pointing to PI3Kα activation as a key point in the cellular proliferation cascade. By incubating CaM-sepharose with glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins containing separated domains of PI3Kα, Joyal et al. (35) found that unphosphorylated CaM binds to the p85 N-terminal (nSH2) and C-terminal (cSH2) domains of PI3Kα in a way similar to insulin receptor substrate 1. Similar to insulin receptor substrate 1 activating PI3Kα through SH2 binding (36), CaM is capable of activating PI3Kα via interaction with the SH2 domains. CaMs are also required for production of PIP3 on phagosomes in vivo (37) and are important in overactivation of PI3Kα/Akt in Alzheimer’s disease patients (38), implying that activation of PI3Kα by CaM is a general molecular event in the cell.

Earlier, we proposed a mechanism for the role of CaM binding to K-Ras4B in full activation of PI3Kα (39, 40). In those works, we recapitulated the established mechanism that under physiological conditions, PI3Kα is fully activated through the binding of active, GTP-bound K-Ras4B, and the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) phosphorylated C-terminal motif. The RTK motif released the autoinhibition exerted by the nSH2 domain on the p110 catalytic domain. In addition, it allosterically helped activate the PI3Kα by binding to its cSH2 domain. We then went on to question how oncogenic Ras signals in the absence of a signaling cue from RTK. With the autoinhibition in place, on its own, Ras is not able to fully activate PI3Kα. This led us to contend that under such conditions, CaM, which is known to be capable of activating PI3Kα by binding to its SH2 domains, can substitute for the RTK motif. Because only K-Ras4B (and K-Ras4A (41, 42)) can bind to CaM, but not H-Ras nor N-Ras (43, 44), this can explain CaM’s role in KRAS-driven cancers. However, recent works revealed that phosphorylation of CaM promotes its interaction with PI3Kα and thus the activation of the PI3Kα/Akt signaling pathway (45). CaM can be phosphorylated by multiple kinases, including insulin receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor, Src family kinases, Janus kinases 2, p38Syk, and protein tyrosine kinases-III (c-Fyn and c-Fgr) (46). The phosphorylation of CaM occurs mainly at Y99 (46, 47), and to a lesser extent at Y138 (46). It has further been observed that when phosphorylation at Y99 was inhibited, the interaction of CaM with PI3Kα and subsequent CaM-driven PI3Kα activation decreased, indicating that phosphorylation of CaM at Y99 directly regulates PI3Kα activation (45). This led us to propose that CaM phosphorylation at Y99 forms a motif similar to the pYXXM segment in RTK (48, 49), resulting in higher affinity to nSH2 and cSH2 domains of the p85 subunit than the unphosphorylated state (35, 48). Superimposition of the pY99 region on the crystal structure of the phosphorylated RTK segment complexed with PI3Kα SH2 domain showed a good agreement. This led us to explore the mechanism of exactly how phosphorylation of CaM promotes its binding to p85 and how activation of PI3Kα takes place.

In this work, we performed explicit-solvent MD simulations combined with dihedral rotation surface scanning to model and systematically study the interactions between pCaM and the nSH2 and cSH2 domains of PI3Kα. Our results show that pCaM forms strong interactions with both nSH2 and cSH2 domains, with the pY99 in pCaM exhibiting the dominant contribution to the interfaces. Notably, although nSH2 and cSH2 have very similar overall structures, they present entirely different binding surfaces toward pCaM. This makes the bindings of nSH2 and cSH2 sensitive to the conformation of pCaM. nSH2 prefers to interact with pCaM with an extended linker, whereas cSH2 favors to bind to pCaM with a collapsed linker. Given that the extended CaM conformation is more populated in solution and the collapsed CaM conformation can emerge upon binding a partner—as in the case of K-Ras4B hypervariable region (19)—our data suggest that pCaM may activate PI3Kα via two independent steps. pCaM with the extended conformation targets the nSH2 domain to release the autoinhibition. This is the critical step in full PI3Kα activation. The collapsed pCaM can activate PI3Kα allosterically through binding to cSH2 domain. The collapsed CaM emerges from K-Ras4B binding. The contribution of this step is minor. A major allosteric contribution comes from K-Ras4B binding to PI3Kα. The affinity of PI3Kα Ras binding domain (RBD) to Ras is in the high micromolar range; but the interaction can gain higher affinity due to the proximal plasma membrane contribution. This mechanism, uncovered through the simulations, provides clues to CaM’s involvement in KRas4B-driven cancer.

Materials and Methods

pCaM/SH2 complexes

The initial coordinates of CaM and the SH2 domains were obtained from the protein data bank (PDB: 1CLL for extended CaM; PDB: 1CDL for collapsed CaM; PDB: 2IUI for nSH2; and PDB: 1H9O for cSH2). The phosphorylated Y99 was established by the standard parameter in the CHARMM force field. Based on the parameter in the patch of TP2, we generated the topology for the phosphorylated tyrosine with two negative charges. Ca2+-loaded pCaMs with both extended and collapsed conformations were selected to individually bind to nSH2 and cSH2 domains. Thus, four pCaM/SH2 complexes were modeled. To establish the initial interfaces between pCaM and SH2 domains, a dihedral-rotating surface scanning was performed. The crystal structures of nSH2 and cSH2 binding to pYXXM peptides derived from platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) (PDB: 2IUI for nSH2 and PDB: 1H9O for cSH2) were firstly taken as the reference for the superimposition. The superimposition was based on the phosphorylated residues in the pYXXM peptides and pY99 in pCaM (49). Fixing the pY99 residue in pCaM and the SH2 domains, pCaMs were rotated along with the dihedral angle of CG-CB-CA-N atoms in pY99. Rotation of 10° per step was made, in total generating 36 conformers for each system that generally covers the possible interfaces between pCaM and SH2 domains. All the generated pCaM-SH2 complexes were submitted to 1) minimization of 5000 steps, 2) MD simulation of 2 ps, and 3) a minimization of 5000 steps in the generalized Born implicit solvent model. Such a protocol ensured considerable flexibility of both protein partners to relax and optimize their interfaces. The scanned pCaM/SH2 complexes with the lowest energies were selected to run the simulations to further evaluate their structural and dynamical properties. Each system was solvated in the cubic water box with NaCl concentration of 0.15 M. The distance between the edge of box to the proteins was set to 15 Å. A minimization of 5000 steps and a short NPT MD simulation of 1 ns were performed to relax the systems, removing the unreasonable atom contacts. For comparison, we also modeled unphosphorylated CaM/SH2 complexes based on the pCaM/SH2 models by removing the phosphorylation at Y99. Taken together, four independent trajectories were run for each CaM/SH2 system. Each trajectory was run for 500 ns.

Molecular simulation protocols

All-atom MD simulations were performed by the NAMD package (50) using the updated CHARMM all-atom additive force field (version C36) (51). Simulations were carried out according to our previously published protocol (52). The NPT simulations were run at the temperature of 310 K and pressure of 1 atm. The RATTLE algorithm was used to constrain the covalent bonds with hydrogen atoms. Short-range van der Waals interactions were calculated by the switch function with the twin-range cutoff at 12 and 14 Å. Long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the force-shift methods with the cutoff of 14 Å. The velocity Verlet integration was used to generate the time step of 2 fs. A total of 4.0 μs simulations was conducted for eight systems. All the analysis was performed using the tools in CHARMM, VMD, and in-house TCL scripts.

Results

Modeling of pCaM-SH2 interfaces

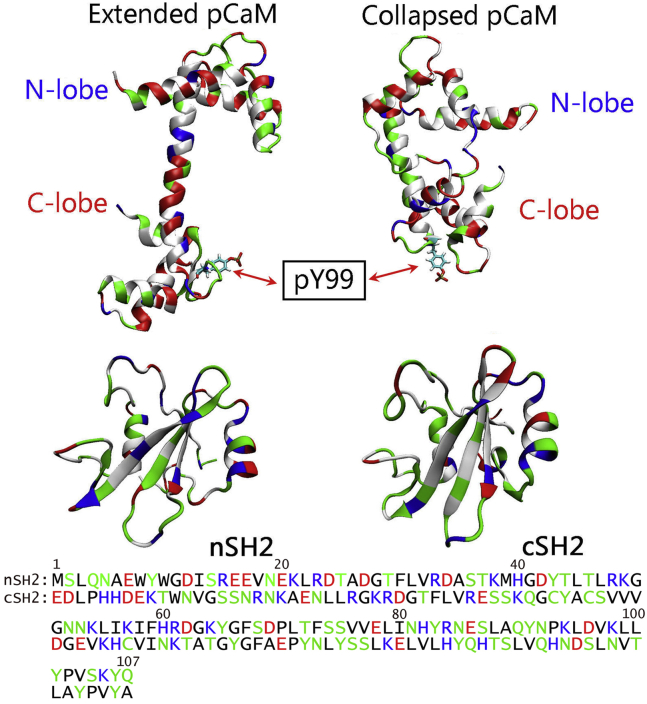

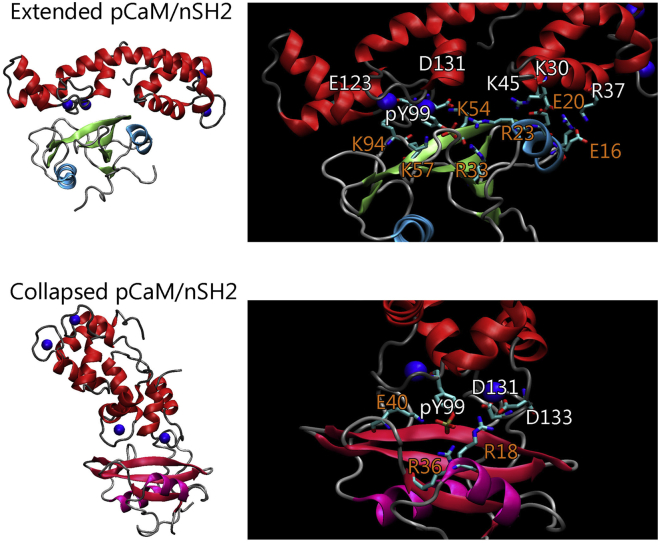

Currently there are many (>500) crystal structures for CaM. The crystal structure of Ca2+-loaded CaM shows that CaM has two symmetric lobes connected by a straight linker (Fig. 1). CaM can yield a compact conformation when bound to its binding partner, leading to the association between the N- and C-lobes. The nSH2 and cSH2 present very similar overall structures, but with different sequences. We modeled pCaMs interacting with both the nSH2 and cSH2 domains of PI3Kα. We phosphorylated CaM at Y99 using two different CaM topologies from the crystal structures with extended and collapsed linkers. In CaMs with both extended and collapsed conformations, Y99 locates at the C-lobe regions of CaM and remains exposed to the solvent. Thus, pCaM binds to SH2 domains via the C-lobes. Upon phosphorylation, the phenol group of Y99 is substituted by the phosphoric acid group, making Y99 charged with two negative charges. Such a change in Y99 is expected to promote electrostatic interactions between CaM and PI3Kα SH2 domains. PI3Kα consists of a p110 catalytic subunit and a p85 regulatory subunit with two SH2 domains (nSH2 and cSH2).

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of pCaM with the extended (PDB: 1CLL) and collapsed (PDB: 1CDL) conformations. The pCaM has N-lobe and C-lobe domains connected by a flexible linker. Shown here are crystal structures and sequences of nSH2 and cSH2 domains. In the protein structures and sequences, hydrophobic, hydrophilic, positively charged, and negatively charged residues are colored white/black, green, blue, and red, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

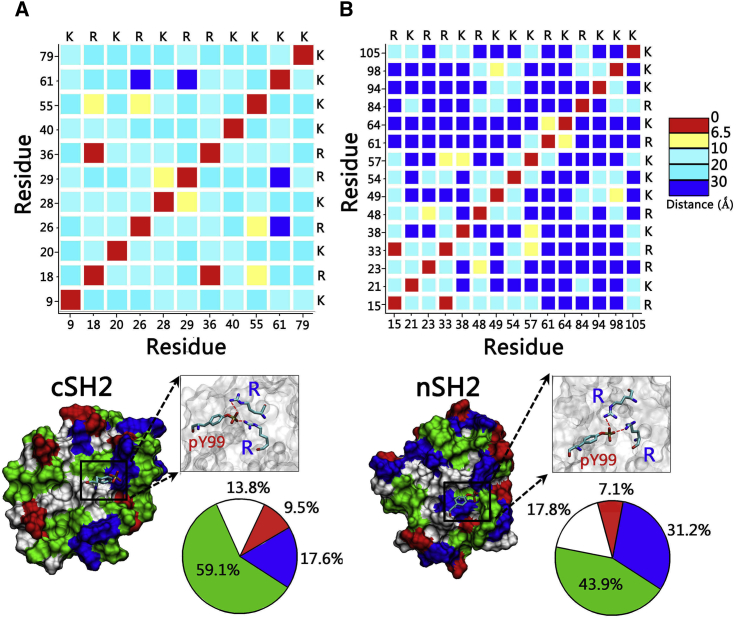

To characterize the binding surface of the SH2 domain for the pCaM interaction, we measured the residue-residue distance matrix of solvent-exposed positively charged amino acids in nSH2 and cSH2. It is interesting to observe that two arginine residues are very close to each other with the distance <6.5 Å, whereas other positively charged residues generally separate to a distance >8.0 Å (Fig. 2). Neighboring arginine residues form a condensed cation surface with two positive charges, which may compensate for the two negative charges of pY99 in CaM by forming salt bridges. In the crystal structures of nSH2 and cSH2 binding to phosphorylated peptides (pYXXM) of PDGFR, the phosphorylated tyrosine residues also bind to the areas with two neighboring arginine residues in nSH2 and cSH2 domains (53, 54). Sequence comparison of pCaM (residues 96–106) with PDGFR (residues 748–758) containing the pYXXM motif shows that 73% of these residues are similar, implying that pCaM may bind to SH2 domains in a way similar to pYXXM motif. The neighboring arginine residues would be the binding sites for the phosphorylated motifs in pCaM.

Figure 2.

Characterization of pCaM binding surfaces of SH2 domains. Shown here is the residue-residue distance matrix for negatively charged residues and surface properties of (A) cSH2 and (B) nSH2 domains. In the protein structures, hydrophobic, hydrophilic, positively charged, and negatively charged residues are colored white, green, blue, and red, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

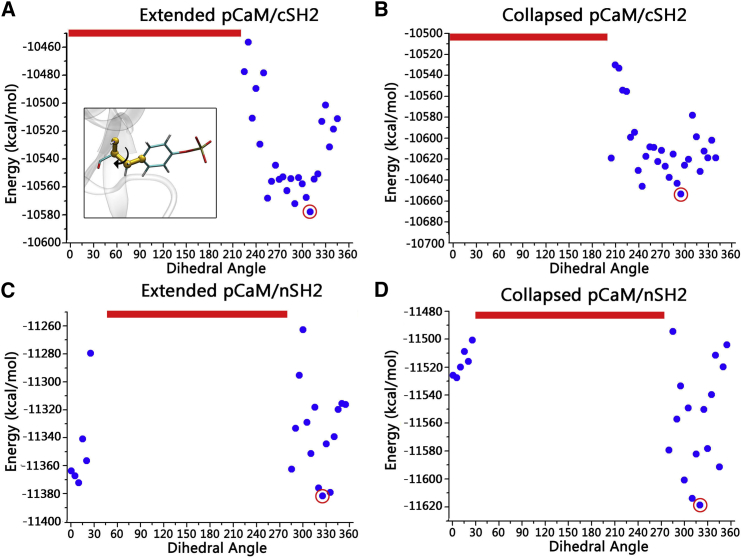

Taking the crystal structures of SH2-pYXXM as the structural reference, multistep superimpositions were made to model the initial binding sites for pY99 residues of pCaM on the nSH2 and cSH2 surface. Fixing the pY99 and SH2 domains, the pCaM was rotated to systematically scan the optimal interfaces in the complexes, generating a total of 144 conformers. The minimization-MD simulation-minimization cycles in the implicit solvent model were performed (details in Materials and Methods) to optimize the interfaces for individual systems and calculate their energies for comparisons. Such a protocol is expected to secure the flexibility for the proteins, balance the computational efficiency, and cover the most likely interfaces in the scanning. The energy profiles show that pCaMs with both extended and collapsed conformations produce similar interfaces while binding to either nSH2 or cSH2 domains (Fig. 3), suggesting that pCaM exhibits similar binding surfaces toward SH2 domains regardless of the conformations. nSH2 and cSH2 have similar overall structures, but entirely different sequences. Although the percentages of hydrophobic residues are similar (32.7% for nSH2 and 34.5% for cSH2), nSH2 has more charged residues (28.0%) than cSH2 (21.4%). Thus, they present different exposed surfaces to bind pCaM. nSH2 (43.9% hydrophilic, 17.8% hydrophobic, 31.2% positively charged, and 7.1% negatively charged surfaces) exhibits different surface properties compared to cSH2 (59.1% hydrophilic, 13.8% hydrophobic, 17.6% positively charged, and 9.5% negatively charged surfaces) (Fig. 2). Thus, pCaM binds to nSH2 and cSH2 in different ways with varied energy profiles (Fig. 3, A and B, versus Fig. 3, C and D). Four structures with the lowest energies, as highlighted by the red circle in the figure, were selected to further evaluate their interactions in the MD simulations (Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Modeling of initial pCaM/SH2 surfaces by dihedral rotation surface scanning. Given here are energy profiles for (A) extended pCaM/cSH2, (B) collapsed pCaM/cSH2, (C) extended pCaM/nSH2, and (D) collapsed pCaM/nSH2. The red lines denote the conformers with the unreasonable atom contacts. To see this figure in color, go online.

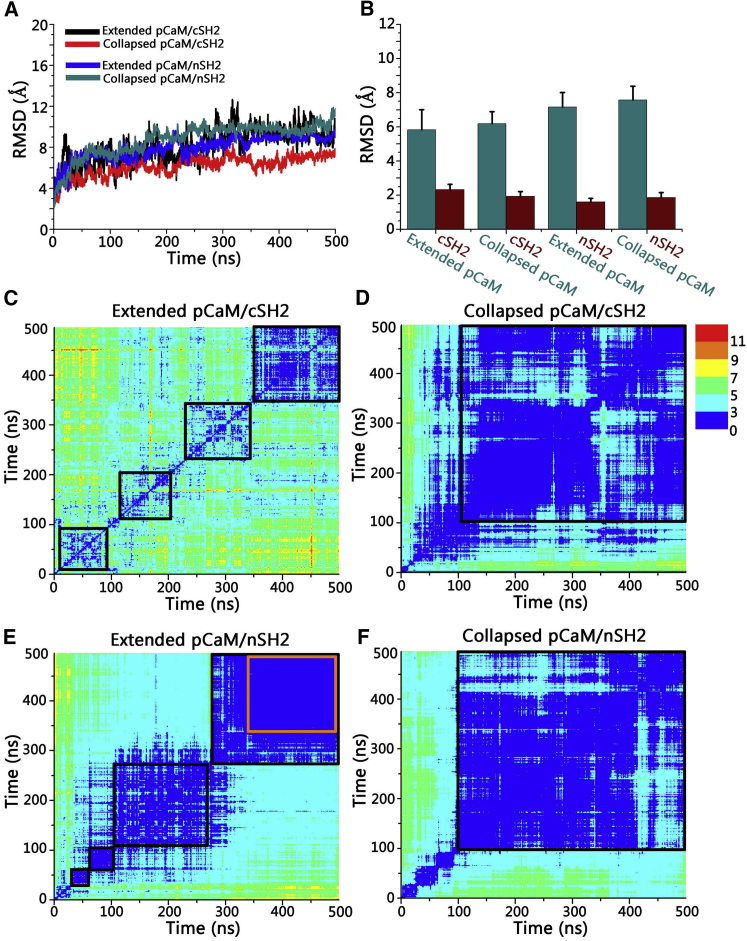

Interactions between pCaM and SH2 domains

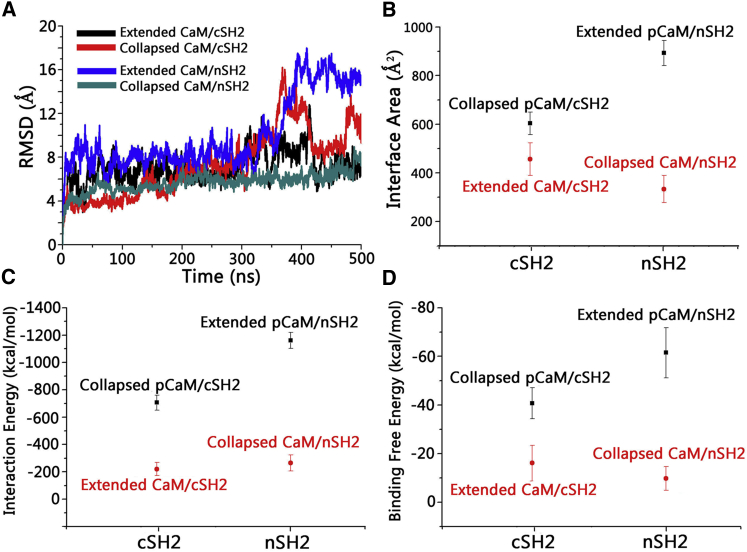

We carried out 500-ns explicit-solvent all-atoms simulations on the eight systems described in the Materials and Methods. The time-dependent root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) profiles show that after structural adjustments in the initial 200 ns, the systems achieved equilibrium (Fig. 4 A). The final structures of pCaM-SH2 complexes illustrate that there are significant conformational evolutions toward the solvent-relaxed complex conformations (Fig. S2). The decomposition of the total RMSD profiles shows that pCaMs present much higher RMSD values in the range of 5.8–7.6 Å than both nSH2 (1.6–1.8 Å) and cSH2 (1.9–2.3 Å) domains (Fig. 4 B). Visual inspection of the trajectory confirms that the structural changes of the complex mainly derive from the pCaM, whereas the SH2 domains remain stable throughout the simulations. To further characterize the dynamics of pCaM in the complexes, the 2D RMSD matrices were calculated (Fig. 4, C–F). The continuous local minima areas in Fig. 4 C indicate that the extended pCaM binding to cSH2 is flexible, presenting the obvious conformational changes through the simulations. The unbound N-lobe domain swung around the cSH2 surface through the flexible linker regions, failing to form stable contacts with cSH2. Such high structural fluctuations made the interface between the extended pCaM and cSH2 unstable, with the interface areas only ∼370 Å2. Due to the compact structure, the collapsed CaM binding to cSH2 presents higher stability in the simulations with an overall RMSD of ∼3 Å (Fig. 4 D). The interfaces between collapsed pCaM and cSH2 exhibit interface areas of ∼620 Å2, which is 67.5% larger than extended pCaM/cSH2 complex.

Figure 4.

Dynamic properties of pCaM/SH2 complexes in solution. (A) Given here are time-dependent total RMSD profiles, (B) decomposed RMSD profiles for individual pCaM and SH2 domains in pCaM/SH2 complexes, and 2D RMSD matrix for (C) extended pCaM/cSH2, (D) collapsed pCaM/cSH2, (E) extended pCaM/nSH2, and (F) collapsed pCaM/nSH2. The color-code dot at position (i,j) denotes the RMSD value between the superimposed conformer i and j of the trajectory. The orange box in (E) highlights the stability of extended pCaM/NSH2 in the last 150 ns. To see this figure in color, go online.

To quantify the binding interface in the complex, we calculated the binding free energies of the complex using molecular mechanics combined with the generalized Born and surface area continuum solvation. The average binding free energy is calculated as a sum of the gas phase contribution, the solvation energy contribution, and the entropic contribution,

| (1) |

where 〈…〉 denotes an average along the MD trajectory. The gas phase contribution to the binding free energy is a sum of the internal energy, the van der Waals interaction, and the electrostatic energy. The solvation free energies include a nonpolar part and an electrostatic part obtained from the GB calculation. The entropic term is a sum of the translational, rotational, and vibrational contributions. The translational and rotational contributions were obtained from the principal moment of inertia calculation, and the vibrational entropy is calculated from the quasiharmonic mode in the VIBRAN module of the CHARMM program. The change in binding free energy due to the complex formation was calculated using

| (2) |

where we followed the protocol of our previous studies (19, 55, 56). The details of the decomposition of each term are in Table 1. The results show that upon binding to cSH2, pCaM with the collapsed conformation produced much lower binding free energy (−40.7 ± 6.4 kcal/mol) than the extended pCaM (−5.5 ± 5.9 kcal/mol), indicating that cSH2 prefers to bind to collapsed pCaM. The opposite trend was observed for pCaM binding to the nSH2 domain. The binding preference of the nSH2 domain is the extended pCaM. The extended pCaM binding to nSH2 presented a dynamic behavior similar to that with cSH2 in the first 280 ns, with the N-lobe region fluctuating around. However, after 300 ns, the extended pCaM twisted and wrapped around the nSH2 domain, successfully establishing strong interfacial contacts between the N-lobe domain of pCaM and one N-terminal α-helix (residue 15–25) of the nSH2 domain (Fig. 5), making the complexes extremely stable with RMSD < 2 Å (Fig. 4 E). Although the collapsed pCaM binding to nSH2 is stable as well, with an RMSD of ∼2.5 Å (Fig. 4 F), the interface area between the collapsed pCaM and nSH2 (∼520 Å2) is much smaller than that of the extended pCaM/nSH2 complex (∼815 Å2). The extended pCaM has binding free energy (−61.5 ± 10.3 kcal/mol), which is 55.7% lower than the collapsed pCaM (−39.5 ± 10.2 kcal/mol), demonstrating that nSH2 prefers to bind to pCaM with the extended conformation. Notably, further analysis of binding free energies indicates that the binding of pCaM to nSH2 is more energetically favorable than binding to cSH2. The extended pCaM/nSH2 complex presents much lower binding free energy (−61.5 ± 10.3 kcal/mol) than collapsed pCaM/cSH2 (−40.7 ± 6.4 kcal/mol), in line with this step being critical in PI3Kα activation.

Table 1.

Binding Free Energies for pCaM/SH2 Complexes

| Systems | 〈ΔGgas〉 (kcal/mol) | 〈ΔGsol〉 (kcal/mol) | −TΔS (kcal/mol) | 〈ΔGb〉 (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extended pCaM/cSH2 | −408.3 ± 66.1 | 371.4 ± 64.3 | 31.3 | −5.5 ± 5.9 |

| Collapsed pCaM/cSH2 | −562.6 ± 62.9 | 490.9 ± 61.8 | 31.0 | −40.7 ± 6.4 |

| Extended pCaM/nSH2 | −1193.1 ± 84.9 | 1100.3 ± 80.3 | 31.3 | −61.5 ± 10.3 |

| Collapsed pCaM/nSH2 | −1264.7 ± 160.9 | 1194.1 ± 157.2 | 31.2 | −39.5 ± 10.2 |

The energies are calculated by the MM-GBSW methods and quasi-harmonic analysis in CHARMM.

Figure 5.

Structures and key interfacial residues for extended pCaM/nSH2 and collapsed pCaM/cSH2 complexes. Shown here are snapshots and interface highlights for extended pCaM/nSH2 and collapsed pCaM/cSH2 complexes. Color codes: pCaM (red), calcium (blue), nSH2 (lime and cyan), and cSH2 (purple and dark red). To see this figure in color, go online.

Interfaces between pCaM and SH2 domain

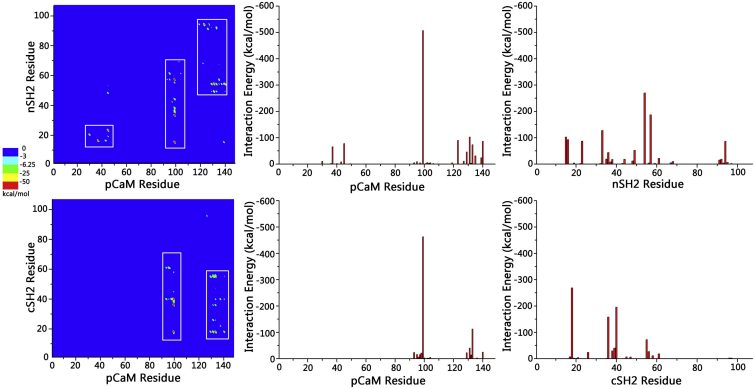

The association between pCaM and SH2 domains is governed by the interfacial residues of both partners. To identify the key residues stabilizing the pCaM/SH2 interfaces, the residue-residue interaction energy matrix and residue-based interaction energies were calculated. The interactions of pCaMs with nSH2 and cSH2 present distinct residue-residue contacting matrices (Fig. 6). The extended pCaM/nSH2 complex mainly contains three binding areas between pCaM and the nSH2 domain: (residues 30–44)pCaM/(residues 15–23)nSH2, (residues 90–110)pCaM/(residues 15–70)nSH2, and (residues 118–140)pCaM/(residues 45–70 and 90–98)nSH2. The collapsed pCaM/cSH2 complex presents two binding areas: (residues 90–110)pCaM/(residues 10–70)cSH2 and (residues 128–140)pCaM/(residues 10–55)cSH2. The major difference in residue contacts between pCaM/nSH2 and pCaM/cSH2 complexes is the binding of the pCaM N-lobe domain with one N-terminal α-helix of nSH2 in pCaM/nSH2, which is absent in pCaM/cSH2. It is very interesting to observe that although the α-helical structures are conserved, nSH2 and cSH2 present different solvent-exposed residues at this region (Fig. S3). The nSH2 domain has one positively charged and two negatively charged residues (E16, E20, and R23) exposed to the solvent, whereas those in cSH2 are mainly hydrophilic (N19, N23, and L25). The exposed charged residues in nSH2 facilitated the formation of four salt bridges between the N-lobe domain of pCaM and nSH2, explaining the preference of nSH2 toward extended pCaM. Although pCaM/nSH2 and pCaM/cSH2 differ in their specific residue contacts, their interfaces are formed and stabilized by several salt bridges at distinct binding areas. Hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts are rarely detected at the interfaces. Similarly, the salt bridges between the phosphorylated tyrosine and the arginine residues of SH2 domains are also the dominant interactions at the interfaces of pYXXM/SH2 complexes, whereas only one hydrophobic contact forms between L755 with SH2 domains. In both nSH2 and cSH2, pY99 of CaM forms triple salt bridges with nSH2 at R15, R33, and K57, and with CSH2 at R18, R36, and K40, respectively (Fig. 5), leading to the dominant energy contribution of the pY99 at the interface (−506.8 kcal/mol for pCaM/nSH2 and −463.3 kcal/mol for pCaM/cSH2). This highlights the importance of phosphorylation in pCaM/SH2 interactions. pCaM/nSH2 exhibits five salt bridges, E123–K94, K45–R23, K30–E20, D131–K54, and R37–E16 at contacting areas, whereas pCaM/cSH2 has two salt bridges, D133–R18 and D131–R18. These residues cooperatively contribute to the interfaces.

Figure 6.

Residue-based analysis on the interfaces of extended pCaM/nSH2 and collapsed pCaM/cSH2 complexes. Given here is the residue-residue contacting matrix (left), and the residue contact number profiles for pCaM (middle) and SH2 domains (right) in extended pCaM/nSH2 (upper row) and collapsed pCaM/cSH2 (lower row) complexes. To see this figure in color, go online.

To further explore the importance of pY99 for the interaction between CaM and SH2 domains, we also carried out 500-ns simulations on unphosphorylated CaM binding to nSH2 and cSH2 domains with the initial interfaces identical to pCaM-SH2 complexes. Because the phosphorylation of Y99 in CaM was removed, the interfaces between CaM and the SH2 domains become weak and unstable (Fig. S4). As indicated by the RMSD profiles, CaM/cSH2 and CaM/nSH2 failed to stably form the interfacial contacts throughout the 500-ns simulations (Fig. 7 A). Although CaM/cSH2 and CaM/nSH2 exhibited relatively stable interfaces, they present much lower interface areas, interaction energies, and binding free energies compared to pCaM/SH2 complexes (Fig. 7, B–D). The absence of pY99 in CaM decreased the interface areas, interaction energies, and binding free energies for CaM/cSH2 and CaM/nSH2 by 26.2 and 64.8%, 70.4 and 79.3%, and 62.5 and 83.6%, respectively, confirming the importance of phosphorylated Y99 for the interaction between CaM and SH2 domains.

Figure 7.

Structural and dynamic properties of CaMs binding to nSH2 and cSH2 domains. (A) Given here are time-dependent RMSD profiles for CaM/SH2 complexes, (B) interface areas, (C) interaction energies, and (D) binding free energies for pCaM/SH2 and CaM/SH2 complexes. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

PI3Kα catalytic efficiency reflects the binding of ATP and the substrate PIP2, the transfer of the phosphoryl group from ATP to PIP2, and finally, the release of the ADP and PIP3 products. This catalytic reaction is in the membrane, not in solution. Under these conditions, the rate constant of the phosphate transfer is inversely proportional to the free energy barrier of the transition state, and the equilibrium constant of the substrate binding is inversely proportional to the affinity of PIP2 to PI3Kα.

PI3Kα is an obligate dimer, with two subunits, the catalytic p110 and the regulatory p85, which contains the two SH2 domains. Binding of the nSH2 and cSH2 to signaling proteins is a central molecular event in PI3Kα activation. When nSH2 binds strongly to p110, it suppresses its catalytic activity. Some proteins, especially those with phosphorylated motifs, may competitively target the interface between the nSH2 domain and the p110, releasing its autoinhibition (57). By contrast, the cSH2 domain presents high fluctuations in the inactive PI3Kα, loosely or not binding to the p110 catalytic subunit. Binding of cSH2 domains to target proteins allosterically helps activate PI3Kα. The key step in activation of PI3Kα is executed by the release of the inhibition of the nSH2 (39, 40). By contrast, the contribution of cSH2 is relatively minor.

Oncogenic hot-spot mutations can also activate PI3Kα (58, 59, 60) either by releasing the autoinhibition of the nSH2 or by obviating the necessity of binding of signaling proteins, such as Ras, to the RBD of PI3Kα. For the first, the E542 and E454K mutations create electrostatic repulsion between the p110 helical domain and nSH2 instead of the salt-bridge interactions in the wild-type (61); for the second, the H1047R mutation in the kinase domain (60) points toward the plasma membrane, perpendicular to the orientation of the wild-type H1047, inducing a conformational change in the C-lobe of the lipid kinase domain at the membrane interface. This mutation mimics Ras action (61). The binding site of RTK’s pYXXM motif (62) or associated adaptor proteins (36) on nSH2 overlaps with its interaction site to p110, explaining why it relieves the autoinhibition similar to the E542K and E454K mutations (63). Binding of the RBD to Ras-GTP allosterically promotes PI3Kα catalytic activity (64, 65). PI3Kα activation requires the synergistic albeit independent events of inhibition release and allosteric activation. PI3Kα catalysis is governed by its ability to bind the plasma membrane and the population of phosphate transfer transition complexes at the p110 active site (66, 67, 68).

The question of how calmodulin acts in KRAS-driven cancers captured the attention of the community decades ago. Early on it was believed that CaM acts to inhibit cancer. That belief rested on the observations that calmodulin is essential in the downregulation of the Raf and the MAPK pathways in cultured fibroblasts, where it exerted an inhibitory effect on Ras activation (43). Further, CaM’s inhibition was observed to synergize with various stimulation factors to induce ERK activation. Even in the absence of stimuli, Ras was shown to be inhibited by CaM. The interaction between CaM and K-Ras4B was shown to be inhibited by the calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) calmodulin-binding domain. These observations indeed confirmed that CaM can inhibit the Raf/Mek/Erk (MAPK) signaling; however, they did not test for signaling through the second major pathway, PI3Kα/Akt, or through tumor cell proliferation. Both pathways are essential in cancer initiation (69, 70). Thus, a reasonable explanation is that CaM’s binding extracts K-Ras4B from the plasma membrane, which would downregulate Raf’s activation and MAPK signaling. Subsequently CaMKII was taken up again, this time as an agent whose CaM binding activates cancer. The underlying thesis was that K-Ras binding to CaM reduces the activity of CaMKII and expression of frizzled-8 precursor protein, and that depletion of frizzled-8 precursor in H-RasG12V-transformed cells stimulates cancer initiation (71). However, in the tumor cell the effective local concentration of CaM is likely to be much higher than that of K-Ras, questioning the extent to which K-Ras/CaM binding would deplete cellular CaM, and thus CaMKII activation.

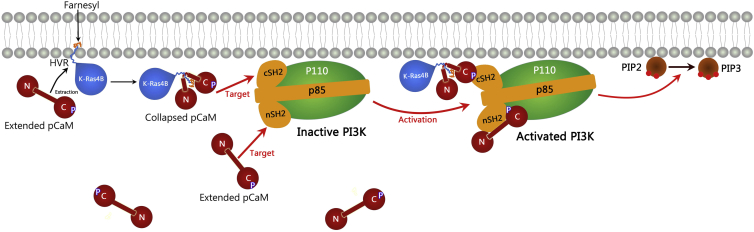

In this work, we observed that 1) pCaM forms a strong and stable interaction with both nSH2 and cSH2 domains, and the binding of pCaM to nSH2 is more energetically favorable than to cSH2; 2) nSH2 prefers to bind to pCaM with an extended conformation that is highly populated in solution in the absence of other partner proteins; and 3) cSH2 prefers to bind to the pCaM with the collapsed conformation that appears upon binding to the partner proteins (19). These results not only reveal pCaM’s mechanism, but provide a mechanistic outline of how oncogenic K-Ras4B can collaborate with pCaM to achieve full activation of PI3Kα. Fig. 8 provides a schematic illustration of the mechanism of the PI3Kα activation, including K-Ras4B.

Figure 8.

The mechanism of pCaM activating PI3Kα. Given here is a schematic illustration of PI3Kα activation by pCaMs with extended and collapsed conformations. pCaM with the populated extended conformation targets the nSH2 domain, releasing its autoinhibition. Extended pCaM extracts K-Ras4B from membranes and undergoes a conformational change into collapsed conformation. The collapsed state is the favored conformation for cSH2, allosterically activating PI3Kα. Upon the activation by pCaM, PI3K binds to membranes and catalyzes the PIP2 to PIP3, to which Akt binds to execute the proliferation pathway. K-Ras4B binds phospholipids selectively. The inner plasma membrane leaflet is enriched with anionic phospholipids such as phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol. K-Ras4B activation level in cancer cells has been linked to phosphatidylserine (79). To see this figure in color, go online.

In the absence of other partner proteins, pCaM with the populated extended conformation mainly targets the nSH2 domain, releasing its autoinhibition. An extended conformation is also the one that is preferred by K-Ras4B, and presumably K-Ras4A, which has similar properties (41, 42, 72). The farnesylated, positively charged, and disordered hypervariable region (HVR) of K-Ras4B interacts strongly with CaM. The binding involves CaM’s two lobes and the linker connecting them. The HVR’s lysine-rich region near the farnesyl interacts tightly with CaM’s negatively charged linker, stably wrapping around it (19). The binding is further stabilized by the hydrophobic farnesyl group, docking into CaM’s hydrophobic pockets present at both lobes. The involvement of the three CaM domains in the interaction with the HVR results in CaM’s undergoing a conformational change into a collapsed compact state. The collapsed state is the favored conformation for cSH2. At the same time, K-Ras4B catalytic domain binds to the p110 catalytic domain of PI3Kα. Together, with a more minor contribution from the pCaM’s cSH2 interaction, it allosterically activates PI3Kα, whose autoinhibition was released by a second pCaM binding to the nSH2.

This mechanism provides a more complete and in-depth view of how oncogenic K-Ras4B acts to fully activate PI3Kα through pCaM. It clarifies why CaM is essential in K-Ras4B-driven PI3Kα/Akt signaling (39). Our previous works pointed out that pCaM may help K-Ras4B to fully activate PI3Kα (39, 40); however, key mechanistic details were missing. CaM specifically targets the HVR of K-Ras4B in the active GTP-bound state. Upon binding the HVR, CaM may undergo a conformational change toward the collapsed conformation, suggesting that the K-Ras4B HVR serves as the typical binding partner for CaM in the K-Ras4B-driven PI3Kα/Akt pathway. The catalytic domain of K-Ras4B binds to the RBD of PI3Kα. The RBD domain is in close proximity to the cSH2 domain. The affinity of RBD to K-Ras4B is not high (in the high micromolar range). The multiple bindings between K-Ras4B and pCaM, pCaM and cSH2, and the K-Ras4B and RBD domain of PI3Kα, as well as the critical proximity (27) of the acidic membrane with which the basic HVR interacts electrostatically, strengthen the PI3Kα/K-Ras4B interaction to facilitate the allosteric activation of PI3Kα, and full signaling in the PI3Kα/Akt/mTOR pathway.

Obtaining the experimental structure of K-Ras4B with CaM has been fraught with hurdles. Despite intensive efforts and years of trying, to date no structure has been obtained. We suggested that the reason is the conformational flexibility of the assembly (19). We hope that obtaining the structure of the pCaM/K-Ras4B/PI3Kα ternary complex will be more constrained to permit such an ultrasignificant endeavor. We expect that the modeling accomplished here, along with its underlying theoretical mechanistic basis, would provide important clues toward unveiling the action of calmodulin in KRAS-driven cancers. Notably, CaM acts on additional important nodes in the major Ras pathways, including Akt, and the scaffolding protein IQGAP1. Importantly, in PI3Kα activation CaM is phosphorylated. Its interaction surfaces may be considered as a potential drug target.

To summarize, CaM is a primary actor in cell signaling. In KRAS-driven cancers, it is involved in cell proliferation via the PI3Kα/Akt signaling pathway. Already two decades ago it was shown experimentally that unphosphorylated CaM activates PI3Kα by directly binding to the nSH2 and cSH2 domains (35). Recently, it was demonstrated that phosphorylation of CaM at Y99 promotes the activation of PI3Kα (45). However, the underlying mechanism has not been well understood, nor was it put in the framework of KRAS-driven cancers. Our modeling and simulations explore the interactions between pCaM and SH2 domains. Our results demonstrate that pCaM presents strong interactions and forms stable interfaces with both nSH2 and cSH2 domains, with pTyr99 in pCaM exhibiting the dominant contributions by forming triple salt bridges. The binding of pCaM to nSH2 is stronger than to cSH2. This is the critical interaction in PI3Kα activation. Further, due to the different binding surfaces, nSH2 and cSH2 have distinct binding preference toward the pCaM conformations. nSH2 prefers to bind to extended pCaM, which is more populated in solution, whereas cSH2 can only form a stable complex with the collapsed pCaM. Collapsed pCaM only appears upon binding to partner proteins, notably K-Ras4B (19). These results unravel the mechanism of PI3Kα activation by pCaM. Pure pCaM with the populated extended conformation targets the nSH2 domain to activate PI3Kα by releasing the autoinhibition of p85 regulatory subunit on the kinase domain of the p110 catalytic subunit. pCaM may also collaborate with partner proteins to interact with cSH2 domains, activating the PI3Kα by the allosteric effects, with a more minor contribution. Such mechanism not only helps to explain the role of CaM in K-Ras4B-driven PI3Kα/Akt signaling pathway; it also organizes available experimental data in KRAS cancer initiation. It emphasizes the presence of two major pathways (MAPK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR) and the effective high local concentration of CaM and Ca2+ in adenocarcinoma cells, where oncogenic K-Ras4B is especially abundant.

Conclusions

Finally, the mechanism of PI3Kα activation by pCaM may be a general protein-protein recognition and activation event in cells. The model of pCaM binding to the PI3Kα regulatory subunit has broad similarity to other systems, such as Protein Kinase A (PKA) activation by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (73). PKA has a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit (74). The PKA regulatory subunit is composed of two cAMP binding domains linked by a flexible linker, analogous to p85 domains in PI3K. Further, the activation of PKA is achieved by the interactions between the phosphate groups of cAMP and the conserved arginine residues in the PKA regulatory domain, which is also highly similar to PI3K activation by pCaM (75, 76, 77). Thus, the mechanism that we suggest here appears general in two respects: first, both kinases have a regulatory subunit whose autoinhibition is released via binding to a phosphate group; and second, in both cases the phosphates (in our case phosphor-tyrosine 99 on calmodulin; in PKA two cAMP molecules) interact with two arginines (in our case in the SH2 domains; in PKA two cAMP binding sites on its regulatory subunit). This analogy also raises the possibility of adopting for CaM-PI3Kα a similar concept in drug discovery as suggested for PKA (78).

Author Contributions

M.Z., H.J., V.G., and R.N. conceived and designed the study. M.Z. and H.J. performed MD simulations. M.Z., H.J., and R.N. prepared and wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

All simulations were performed using the high-performance computational facilities of the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov).

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under contract HHSN261200800001E. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research.

Editor: David Sept.

Footnotes

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)31019-6.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Toufighi K., Yang J.S., Kiel C. Dissecting the calcium-induced differentiation of human primary keratinocytes stem cells by integrative and structural network analyses. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capiod T. Cell proliferation, calcium influx and calcium channels. Biochimie. 2011;93:2075–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orrenius S., Zhivotovsky B., Nicotera P. Regulation of cell death: the calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:552–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pittas A.G., Lau J., Dawson-Hughes B. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:2017–2029. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolland M.J., Avenell A., Reid I.R. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz E.C., Qu B., Hoth M. Calcium, cancer and killing: the role of calcium in killing cancer cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:1603–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wactawski-Wende J., Kotchen J.M., Manson J.E., Women’s Health Initiative Investigators Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:684–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Johny M., Yue D.T. Calmodulin regulation (calmodulation) of voltage-gated calcium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014;143:679–692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grabarek Z. Structure of a trapped intermediate of calmodulin: calcium regulation of EF-hand proteins from a new perspective. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1351–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlton S.M. Localization of CaMKIIα in rat primary sensory neurons: increase in inflammation. Brain Res. 2002;947:252–259. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02932-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S., Xie L., Zhang R. Cloning and expression of a pivotal calcium metabolism regulator: calmodulin involved in shell formation from pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;138:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Høyer-Hansen M., Bastholm L., Jäättelä M. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-β, and Bcl-2. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson D.P., Sutherland C., Walsh M.P. Ca2+ activation of smooth muscle contraction: evidence for the involvement of calmodulin that is bound to the triton insoluble fraction even in the absence of Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2186–2192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Means A.R. Calmodulin: properties, intracellular localization, and multiple roles in cell regulation. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 1981;37:333–367. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571137-1.50011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei F., Qiu C.S., Zhuo M. Calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV is required for fear memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:573–579. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi T. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II—discovery, progress in a quarter of a century, and perspective: implication for learning and memory. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28:1342–1354. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Racioppi L., Means A.R. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV in immune and inflammatory responses: novel routes for an ancient traveller. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erwin N., Patra S., Winter R. Probing conformational and functional substates of calmodulin by high pressure FTIR spectroscopy: influence of Ca2+ binding and the hypervariable region of K-Ras4B. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:30020–30028. doi: 10.1039/c6cp06553h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang H., Banerjee A., Nussinov R. Flexible-body motions of calmodulin and the farnesylated hypervariable region yield a high-affinity interaction enabling K-Ras4B membrane extraction. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12544–12599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.785063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tidow H., Nissen P. Structural diversity of calmodulin binding to its target sites. FEBS J. 2013;280:5551–5565. doi: 10.1111/febs.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.House S.J., Ginnan R.G., Singer H.A. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-Δ isoform regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C2276–C2287. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00606.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berchtold M.W., Villalobo A. The many faces of calmodulin in cell proliferation, programmed cell death, autophagy, and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:398–435. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Si J., Collins S.J. Activated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIγ is a critical regulator of myeloid leukemia cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3733–3742. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelman J.A. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantley L.C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harriague J., Bismuth G. Imaging antigen-induced PI3K activation in T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1090–1096. doi: 10.1038/ni847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siempelkamp B.D., Rathinaswamy M.K., Burke J.E. Molecular mechanism of activation of class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) by membrane-localized HRas. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:12256–12266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.789263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lien E.C., Dibble C.C., Toker A. PI3K signaling in cancer: beyond AKT. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017;45:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kriplani N., Hermida M.A., Leslie N.R. Class I PI 3-kinases: function and evolution. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2015;59:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agamasu C., Ghanam R.H., Saad J.S. The interplay between calmodulin and membrane interactions with the pleckstrin homology domain of Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:251–263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.752816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calleja V., Laguerre M., Larijani B. Role of a novel PH-kinase domain interface in PKB/Akt regulation: structural mechanism for allosteric inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng C.K., Fan Q.W., Weiss W.A. PI3K signaling in glioma—animal models and therapeutic challenges. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:112–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martini M., De Santis M.C., Hirsch E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: an updated review. Ann. Med. 2014;46:372–383. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.912836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo J., Manning B.D., Cantley L.C. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joyal J.L., Burks D.J., Sacks D.B. Calmodulin activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28183–28186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Backer J.M., Myers M.G., Jr., Schlessinger J. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase is activated by association with IRS-1 during insulin stimulation. EMBO J. 1992;11:3469–3479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vergne I., Chua J., Deretic V. Tuberculosis toxin blocking phagosome maturation inhibits a novel Ca2+/calmodulin-PI3K hVPS34 cascade. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:653–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteras N., Muñoz Ú., Martín-Requero Á. Altered calmodulin degradation and signaling in non-neuronal cells from Alzheimer’s disease patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:267–277. doi: 10.2174/156720512800107564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nussinov R., Muratcioglu S., Keskin O. The key role of calmodulin in KRAS-driven adenocarcinomas. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015;13:1265–1273. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nussinov R., Muratcioglu S., Keskin O. K-Ras4B/calmodulin/PI3Kα: a promising new adenocarcinoma-specific drug target? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2016;20:831–842. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1135131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J., Jang H. A new view of Ras isoforms in cancers. Cancer Res. 2016;76:18–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakrabarti M., Jang H., Nussinov R. Comparison of the conformations of KRAS isoforms, K-Ras4A and K-Ras4B, points to similarities and significant differences. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:667–679. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villalonga P., López-Alcalá C., Agell N. Calmodulin binds to K-Ras, but not to H- or N-Ras, and modulates its downstream signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:7345–7354. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7345-7354.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez-Moya B., Barceló C., Agell N. CaM interaction and Ser181 phosphorylation as new K-Ras signaling modulators. Small GTPases. 2011;2:99–103. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.2.2.15555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhuri P., Rosenbaum M.A., Graham L.M. Membrane translocation of TRPC6 channels and endothelial migration are regulated by calmodulin and PI3 kinase activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:2110–2115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600371113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benaim G., Villalobo A. Phosphorylation of calmodulin. Functional implications. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:3619–3631. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stateva S.R., Salas V., Villalobo A. Characterization of phospho-(tyrosine)-mimetic calmodulin mutants. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nussinov R., Wang G., Gaponenko V. Calmodulin and PI3K signaling in KRAS cancers. Trends Cancer. 2017;3:214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nussinov R., Jang H., Zhang J. Intrinsic protein disorder in oncogenic KRAS signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:3245–3261. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2564-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M., Zheng J., Ma B. Release of cytochrome c from Bax pores at the mitochondrial membrane. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:2635. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02825-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nolte R.T., Eck M.J., Harrison S.C. Crystal structure of the PI 3-kinase p85 amino-terminal SH2 domain and its phosphopeptide complexes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:364–374. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pauptit R.A., Dennis C.A., Murshudov G.N. NMR trial models: experiences with the colicin immunity protein Im7 and the p85α C-terminal SH2-peptide complex. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1397–1404. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang H., Muratcioglu S., Nussinov R. Membrane-associated Ras dimers are isoform-specific: K-Ras dimers differ from H-Ras dimers. Biochem. J. 2016;473:1719–1732. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muratcioglu S., Jang H., Nussinov R. PDEδ binding to Ras isoforms provides a route to proper membrane localization. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:5917–5927. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b03035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shoelson S.E., Sivaraja M., Weiss M.A. Specific phosphopeptide binding regulates a conformational change in the PI 3-kinase SH2 domain associated with enzyme activation. EMBO J. 1993;12:795–802. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miled N., Yan Y., Williams R.L. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang C.H., Mandelker D., Amzel L.M. The structure of a human p110α/p85α complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kα mutations. Science. 2007;318:1744–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao L., Vogt P.K. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110α of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mandelker D., Gabelli S.B., Amzel L.M. A frequent kinase domain mutation that changes the interaction between PI3Kα and the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16996–17001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carpenter C.L., Auger K.R., Cantley L.C. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase is activated by phosphopeptides that bind to the SH2 domains of the 85-kDa subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9478–9483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carson J.D., Van Aller G., Luo L. Effects of oncogenic p110α subunit mutations on the lipid kinase activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 2008;409:519–524. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kodaki T., Woscholski R., Parker P.J. The activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by Ras. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:798–806. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gupta S., Ramjaun A.R., Downward J. Binding of Ras to phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110α is required for Ras-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Cell. 2007;129:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gabelli S.B., Echeverria I., Amzel L.M. Activation of PI3Kα by physiological effectors and by oncogenic mutations: structural and dynamic effects. Biophys. Rev. 2014;6:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s12551-013-0131-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burke J.E., Perisic O., Williams R.L. Oncogenic mutations mimic and enhance dynamic events in the natural activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110α (PIK3CA) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15259–15264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205508109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao L., Vogt P.K. Class I PI3K in oncogenic cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2008;27:5486–5496. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J., Csermely P. Oncogenic KRAS signaling and YAP1/β-catenin: similar cell cycle control in tumor initiation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;58:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J., Jang H. A new view of pathway-driven drug resistance in tumor proliferation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;38:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang M.T., Holderfield M., McCormick F. K-Ras promotes tumorigenicity through suppression of non-canonical Wnt signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Z.L., Buck M. Computational modeling reveals that signaling lipids modulate the orientation of K-Ras4A at the membrane reflecting protein topology. Structure. 2017;25:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsai C.J., Nussinov R. The molecular basis of targeting protein kinases in cancer therapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013;23:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim C., Cheng C.Y., Taylor S.S. PKA-I holoenzyme structure reveals a mechanism for cAMP-dependent activation. Cell. 2007;130:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diller T.C., Madhusudan N.H., Taylor S.S. Molecular basis for regulatory subunit diversity in cAMP-dependent protein kinase: crystal structure of the type II β-regulatory subunit. Structure. 2001;9:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berman H.M., Ten Eyck L.F., Taylor S.S. The cAMP binding domain: an ancient signaling module. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:45–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bubis J., Neitzel J.J., Taylor S.S. A point mutation abolishes binding of cAMP to site A in the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:9668–9673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nussinov R., Tsai C.J. Unraveling structural mechanisms of allosteric drug action. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Banerjee A., Jang H., Gaponenko V. The disordered hypervariable region and the folded catalytic domain of oncogenic K-Ras4B partner in phospholipid binding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;36:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.