Abstract

There remains a need for new non-ionic detergents that are suitable for use in biochemical and biophysical studies of membrane proteins. Here we explore the properties of n-dodecyl-β-melibioside (β-DDMB) micelles as a medium for membrane proteins. Melibiose is D-galactose-α(1→6)-D-glucose. Light scattering showed the β-DDMB micelle to be roughly 30kD smaller than micelles formed by the commonly used n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (β-DDM). β-DDMB stabilized diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK) against thermal inactivation. Moreover, activity assays conducted using aliquots of DAGK purified into β-DDMB yielded activities that were 40% higher than for DAGK purified into β-DDM. β-DDMB yielded similar or better TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra for two single pass membrane proteins and the tetraspan membrane protein peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22). β-DDMB appears be a useful addition to the toolbox of non-ionic detergents available for membrane protein research.

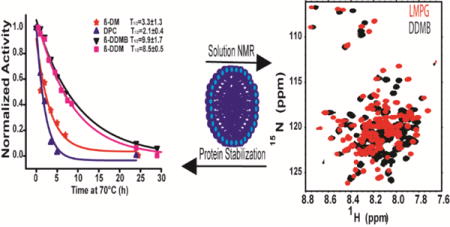

TOC image

Spectacular advances in membrane protein structural biology over the past 20 years have been enabled, in part, by the development of new and improved model membranes for solubilizing and stabilizing these difficult-to-study biomolecules.1–9 Such media include nanodiscs, bicelles, new classes of detergents, and lipidic cubic phases. Despite these advances, there remains room for innovation. For example, there are few examples of successful use of non-ionic detergents in NMR studies of membrane proteins. Given the widespread use of uncharged detergents such as n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (β-DDM) in crystallization/diffraction studies of many different membrane proteins, the fact that β-DDM, lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (MNG), and other uncharged detergents have thus far been of limited use for NMR has been vexing. This paper was originally motivated by the desire to find an uncharged detergent that can be used to solubilize membrane proteins for NMR studies. This led one of the authors of this work to recall an alkyl glycoside first synthesized and subjected to preliminary characterization many years ago, n-dodecyl-β-melibioside (β-DDMB, Figure S1).10 The disaccharide melibiose is distinct from maltose and most other disaccharide in that its galactose and glucose units are connected by an α(1➔6) glycosidic linkage, conferring a much higher conformation freedom between the two sugar groups than is possible for non-1➔6 glycosides. We hypothesized that this enhanced conformational flexibility might attune its micelle properties and interactions with membrane proteins in a way that would promote its utility in both biochemical and biophysical studies, including solution NMR spectroscopy. Preliminary testing of this hypothesis is presented herein.

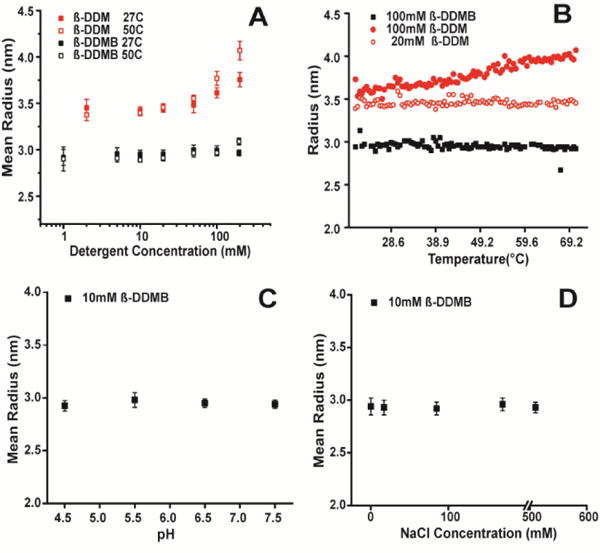

DDMB was synthesized and purified as described in the Supporting Materials and Methods and Figure S2. Using an ANS dye-based fluorescence method11 the critical micelle concentration of β-DDMB at 25 °C was determined to be 0.3 mM. This is higher than for β-DDM (0.2 mM12) and matches the value previously determined for an unresolved mixture of α and β mixtures of DDMB.13 Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed to assess the size and aggregation number of β-DDMB micelles based on the assumption that they are spherical. Our DLS measurements for micelles of pure β-DDMB at 25°C and at concentrations <100 mM (Figure 1) indicate that the radius of hydration (Rh) for β-DDMB micelles is 2.9 nm and the aggregation number is roughly 84, corresponding to an aggregate molecular weight of 42 kDa. These results are similar to those previously reported for an α + β anomeric mixture of DDMB in the 20–40 mM concentration range.13 Multi-angle light scattering (MALS) was used to confirm the DLS result. MALS determines the molecular weight of particles without needing a shape factor or modeling. The MALS result of 46 kDa for the β-DDMB micelle (Table S1) was in good agreement with the value determined by DLS.

Figure 1.

Use of DLS to characterize the mean radius of hydration (Rh) of β-DDMB and β-DDM micelles. A) 10mM DDMB (black) or 10mM DDM (red) detergent was dissolved in water and subjected to a 1°C/min temperature ramp. B) Example of a temperature ramp used in panel A. C) β-DDMB micelle size as a function of pH. The buffer was either 25mM imidazole buffered at either pH 7.5 or 6.5, or 25mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 or 4.5. D) β-DDMB micelles as a function of salt concentration.

β-DDM14 has previously been shown to form micelles in the range of 69–76 kDa15, significantly larger than the ca. 42 kDa micelles formed by β-DDMB (see also the Rh comparisons in Fig. 1A–B). β-DDM micelles also exhibited a linear temperature-dependent increase in size at higher concentrations (i.e. 100mM) not seen for β-DDMB micelles at 100 mM (Fig. 1B). The Rh of β-DDMB micelles was also independent of both pH and ionic strength (Figs. 1C and 1D). The constancy of the properties of β-DDMB micelles across a wide range of relevant pH, temperatures, concentrations, and ionic strengths is useful because β-DDMB micelles can be employed in a wide range of conditions without concern about major changes in micellar properties.

To test whether β-DDMB micelles are smaller than those of β-DDM in the presence of a membrane protein we used SEC-MALS to examine the sizes of micelles containing E. coli diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK), a 42 kDa homotrimeric mostly-helical protein with three transmembrane segments per subunit. The β-DDMB/DAGK complex is roughly 30kD smaller than the βDDM/DAGK complex (Table S2), indicating that the smaller micelle size of β-DDMB extends to its complex with DAGK.

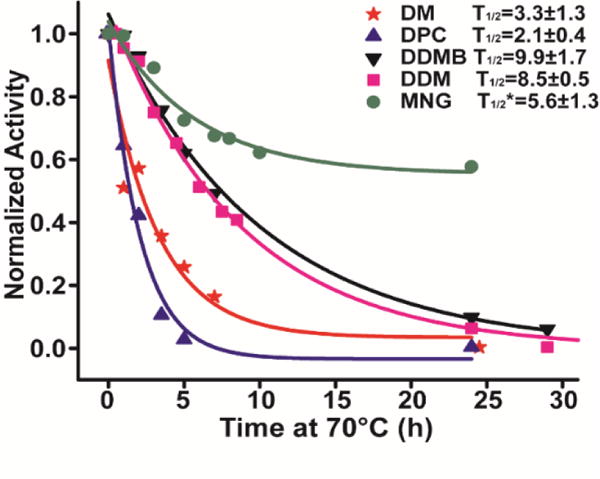

We next tested the ability of β-DDMB to maintain the stability of a membrane protein. DAGK was purified into β-DDMB and into each of four commonly used detergents (n-dodecylphosphocholine: DPC, n-decyl-β-maltoside: β-DM, MNG, and β-DDM) and incubated at 70°C. Aliquots were removed as a function of time and subjected to the standard DAGK activity assay (in DM/cardiolipin mixed micelles) to determine t1/2 values for irreversible inactivation of the enzyme—a measure of thermostability.16 As shown in Figure 2, DAGK is much more stable in β-DDM and β-DDMB (T1/2 of 8.5±0.5 h and 9.9±1.7 h respectively) than in DPC or β-DM, where T1/2 in both cases was < 4 hours. In the case of MNG there seem to be two populations of DAGK-MNG mixed micelles: a ca. 40% population in which DAGK is sensitive to thermal degradation (T1/2 of 5.6 hours), while the other 60% population appears to be resistant to thermal degradation over a period of many hours. This heterogeneity may reflect the fact that the properties of MNG are close to the borderline between being detergent-like and being lipid-like, such that MNG may be able to form more than one type of kinetically stable complexes with some membrane proteins. In any case, these results indicate that β-DDMB is similar to β-DDM in terms of its ability to suppress irreversible thermal inactivation of DAGK and much better than DPC or β-DM.16

Figure 2.

Thermal stability of DAGK in β-DDMB and other detergents. DAGK samples (0.2 mg/ml) were incubated at 70°C, with aliquots being removed at time points and assayed in the standard β-DM/cardiolipin mixed miceller DAGK activity assay.17 T1/2* of MNG represents the DAGK population that sensitive to thermal inactivation in MNG/DAGK mixed micelles.

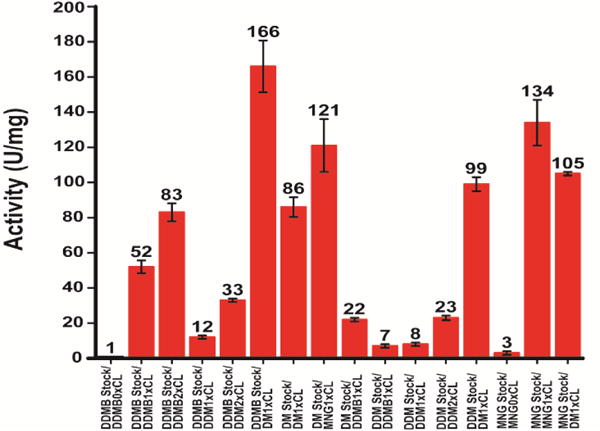

We next tested the degree to which β-DDMB can serve as a medium that supports the native functionality of a membrane protein. We again employed DAGK, which was purified into lipid-free β-DDMB, MNG, β-DDM, and β-DM. Aliquots from these stock solutions were then transferred into DAGK assay mixtures prepared using several different types of micelles or detergent-cardiolipin mixed micelles, including β-DM/cardiolipin mixed micelles (the traditional standard assay condition17). As can be seen in Figure 3, DAGK has only low activity (ca. 1 unit/mg) when assays are carried out in lipid-free β-DDMB micelles, as is also the case for lipid-free β-DM, MNG, and β-DDM. However, the presence of cardiolipin (CL) in the assay mixtures as a lipid activator dramatically enhances DAGK activity in β-DDM, MNG, and β-DDMB. The activities observed in β-DDMB/CL and β-DDM/CL are not as high as for the corresponding reactions carried out in β-DM/CL or MNG/CL, suggesting subtle differences in DAGK structure and/or dynamics that result in sub-optimal catalytic properties in β-DDMB/CL and β-DDM/CL mixed micelles relative to β-DM/CL and MNG/CL conditions. When the same DAGK stock is used MNG with cardiolipin gives a higher activity compared to DM with cardiolipin. A surprising observation is that DAGK prepared in β-DDMB and then aliquoted (≥250-fold diluted) into either β-DM/CL, β-DDM/CL, or β-DDMB/CL mixed micelle assay mixtures yielded higher activities than the corresponding assays initiated using small aliquots of DAGK prepared in β-DM, β-DDM, or MNG micelles and then transferred to these same detergent/CL mixtures. Indeed, the observed specific activity of 166±15 U/mg for DAGK purified into β-DDMB and the aliquoted into β-DM/CL mixed micelles is much higher than the highest previously reported 30°C mixed micellar specific activity for DAGK, which is 120 U/mg.18, 19 This suggests that DAGK prepared in β-DM (and, most likely, many other detergent types) micelles is susceptible to irreversible misfolding, a problem that is avoided when the enzyme is prepared in β-DDMB. Indeed, DAGK has long been known to be prone to misfold in detergent micelles.20, 21 These results show that not only does β-DDMB provide a medium that supports the thermal stability of DAGK, but it also seems to enhance its efficiency of folding during and following purification (see Supporting Materials and Methods). On the other hand, β-DDMB is typical of most detergents22, 23 in that it cannot itself satisfy the requirement of DAGK requirement for the presence of a lipid cofactor for maximal catalytic activity.24, 25

Figure 3.

DAGK activity assays started with detergent aliquots of DAGK diluted various micelle and mixed micelle assay mixtures. DAGK was purified into β-DDMB, β-DM, β-DDM, or MNG micelles (stock) and then assayed using reaction mixtures at 30°C. The “standard” assay condition is labeled DM1×CL. “1×CL” refers to the fact that the mole fraction of CL in the mixture is the same (1×) as in the standard assay procedure.17

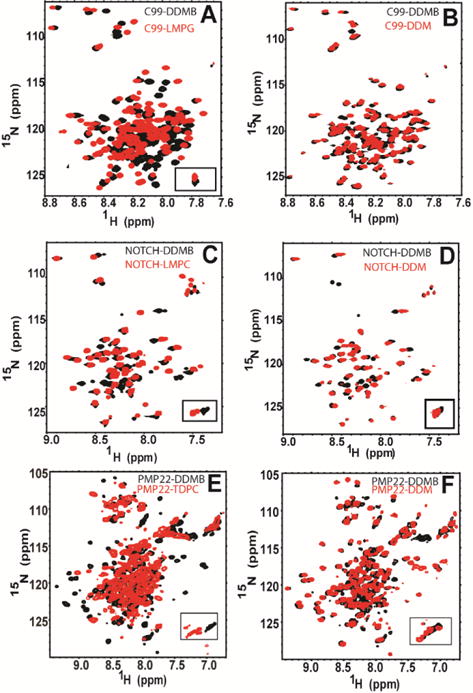

We next examined β-DDMB micelles as a medium for NMR studies of membrane proteins. TROSY-HSQC were collected for three different membrane proteins: (i) the human Notch1 transmembrane domain (Notch-TMD) residues 1721–1771 (a single span protein), (ii) the 99-residue C99 domain of the human amyloid precursor protein, the immediate precursor of the amyloid-β polypeptide (also with single transmembrane segment), and (iii) the 160 residue human peripheral myelin protein 22 (a mostly helical protein with 4 transmembrane segments). Each of these proteins was purified into β-DDMB micelles, into β-DDM micelles, and into the micelle type previously observed to yield the most favorable NMR spectra for each protein following extensive screening.26, 27,28 A TROSY-HSQC spectrum was collected for each sample. Figure 4 shows that β-DDMB yields spectra for C99 and the Notch-TMD that are comparable in quality with the detergents previously shown to yield the best spectra for these proteins (lyso-myristoylphosphatidylglycerol, LMPG, for C99 and lyso-myristoylphosphatidylcholine, LMPC, for the Notch-TMD). Fig. 4 also shows that β-DDMB also yields better spectra for C99 and the Notch-TMD than β-DDM. In both cases certain peaks observed when the proteins are in β-DDMB are too broad to detect in β-DDM. For example, there are a pair of black peaks near 111 PPM in the 15N dimension for the Notch-TMD in β-DDMB for which there are no corresponding red peaks from β-DDM. The average 15N linewidths for Notch in the β-DDM micelle are ~32% larger than the linewidths for Notch in β-DDMB, most likely reflecting the significantly larger size of β-DDM micelles compared to β-DDMB micelles (see Table S2). The 15N linewidths of C99 in a β-DDM micelle were ~12% larger than the linewidths in the β-DDMB micelle.

Figure 4.

NMR spectra of single span membrane proteins in β-DDMB and in other detergents. A) 400μM C99 in 9% β-DDMB (black) and 400μM C99 in 9% LMPG (red). B) 400μM C99 in 9% β-DDMB (black) and 300 μM C99 in 9% β-DDM (red). C) 230μM Notch-TMD in 5% β-DDMB (black) and 300μM Notch-TMD in 1% LMPC (red). D) 230μM Notch-TMD in 5% β-DDMB (black) and 300μM Notch-TMD in 4.5% β-DDM (red). E) 350μM PMP-22 in 20% β-DDMB (black) and 700μM PMP-22 in 20% TDPC (red). F) 350μM PMP-22 in 20% β-DDMB (black) and 400μM PMP-22 in 20% β-DDM (red).

A more demanding test case for NMR is provided by the human PMP22, a tetraspan membrane protein. Despite over a decade of effort to optimize NMR conditions for this disease-linked protein the best NMR spectra acquired to date have been in tetradecylphosphocholine (TDPC) micelles and these are highly unsatisfactory, characterized by the absence of many peaks and considerable heterogeneity of linewidths among the peaks that can be observed.28, 29 As shown in Fig. 4E, PMP22 presents an improved spectrum when purified in β-DDMB relative to TDPC. The quality of the spectrum from β-DDM and β-DDMB are more similar (Fig. 4F), however, the β-DDMB spectrum exhibits more peaks in the crowded region between 8.5 and 7.5 H ppm.

To conclude, detergents remain a nearly ubiquitous tool in biochemical and biophysical studies of membrane proteins, usually being employed during purification and reconstitution, as well as often being a component of the final model membrane system in which the membrane protein is characterized. Here, studies of β-DDMB that show that it forms smaller micelles than the commonly used β-DDM, even though both detergents have n-dodecyl tails and disaccharide head groups. β-DDMB is just as good as β-DDM at maintaining the thermal stability of a complex membrane enzyme, DAGK. Moreover, β-DDMB is better than any detergent yet tested as a medium in which to purify DAGK in a way that avoids misfolding. Finally, for three different membrane proteins β-DDMB was seen to yield NMR spectra of similar or even higher quality than previously observed for the best of the previously tested detergents. This is an important development for non-ionic detergents, which have rarely been used as membrane-mimetic media in previous NMR studies. We hope these observations will encourage both further characterization of β-DDMB and exploration of applications for which it may be uniquely well suited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

JMH was supported by US NIH T32 CA00958229. The NMR instrumentation used in this work was supported by NIH S10 RR026677 and NSF DBI-0922862. This work was supported by US NIH grants RO1 GM106672, RO1 AG056147 and RO1 NS095089.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Materials and methods, Figures S1 and S2, Extended Figure Captions, Tables S1 and S2, Supporting References

Notes

It is declared that Anatrace (the employer of authors BT and RM) is a producer and vendor of β-DDMB and the other detergents employed in this work.

References

- 1.Seddon AM, Curnow P, Booth PJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorr JM, Scheidelaar S, Koorengevel MC, Dominguez JJ, Schafer M, van Walree CA, Killian JA. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45:3–21. doi: 10.1007/s00249-015-1093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warschawski DE, Arnold AA, Beaugrand M, Gravel A, Chartrand E, Marcotte I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808:1957–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raschle T, Hiller S, Etzkorn M, Wagner G. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffrey M, Cherezov V. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:706–731. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae PS, Rasmussen SGF, Rana RR, Gotfryd K, Chandra R, Goren MA, Kruse AC, Nurva S, Loland CJ, Pierre Y, Drew D, Popot JL, Picot D, Fox BG, Guan L, Gether U, Byrne B, Kobilka B, Gellman SH. Nat Methods. 2010;7:1003–1008. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durr UHN, Gildenberg M, Ramamoorthy A. Chem Revs. 2012;112:6054–6074. doi: 10.1021/cr300061w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32403–32406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders CR, Prestegard JH. Biophys J. 1990;58:447–460. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82390-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miguel MD, Eidelman O, Ollivon M, Walter A. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8921–8928. doi: 10.1021/bi00448a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VanAken T, Foxall-VanAken S, Castleman S, Ferguson-Miller S. Meth Enzymol. 1986;125:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)25005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kegel LL, Szabo LZ, Polt R, Pemberton JE. Green Chem. 2016;18:4446–4460. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosevear P, VanAken T, Baxter J, Ferguson-Miller S. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4108–4115. doi: 10.1021/bi00558a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver RC, Lipfert J, Fox DA, Lo RH, Doniach S, Columbus L. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou YF, Lau FW, Nauli S, Yang D, Bowie JU. Prot Sci. 2001;10:378–383. doi: 10.1110/ps.34201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czerski L, Sanders CR. Anal Biochem. 2000;284:327–333. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koehler J, Sulistijo ES, Sakakura M, Kim FJ, Ellis CD, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7089–7099. doi: 10.1021/bi100575s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Horn WD, Kim HJ, Ellis CD, Hadziselimovic A, Sulistijo ES, Karra MD, Tian CL, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Horn WD, Kim HJ, Ellis CD, Hadziselimovic A, Sulistijo ES, Karra MD, Tian C, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorzelle BM, Nagy JK, Oxenoid K, Lonzer WL, Cafiso DS, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16373–16382. doi: 10.1021/bi991292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QX, Mittal R, Huang LJ, Travis B, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11606–11608. doi: 10.1021/bi9018708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinogradova O, Sonnichsen F, Sanders CR. J Biomol Nmr. 1998;11:381–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1008289624496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh JP, Bell RM. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6239–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh JP, Bell RM. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5062–5069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beel AJ, Mobley CK, Kim HJ, Tian F, Hadziselimovic A, Jap B, Prestegard JH, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9428–9446. doi: 10.1021/bi800993c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deatherage CL, Lu ZW, Kim JH, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2015;54:3565–3568. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakakura M, Hadziselimovic A, Wang Z, Schey KL, Sanders CR. Structure. 2011;19:1160–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobley CK, Myers JK, Hadziselimovic A, Ellis CD, Sanders CR. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11185–11195. doi: 10.1021/bi700855j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.