Abstract

The current study aims to assign and estimate the total creatine (tCr) signal contribution to the Z-spectrum in mouse brain at 11.7 Tesla. Creatine (Cr), phosphocreatine (PCr) and protein phantoms were used to confirm presence of a guanidinium resonance at this field strength. Wild type (WT) and knockout mice with Guanidinoacetate N-Methyltransferase deficiency (GAMT−/−) that have low Cr and PCr concentrations in the brain were used to assign the tCr contribution to the Z-spectrum. To estimate the total guanidinium concentrations, two pools for the Z-spectrum around 2 ppm were assumed: (i) a Lorentzian function representing the guanidinium CEST at 1.95 ppm in the 11.7 T Z-spectrum; (ii) a background signal that can be fitted by a polynomial function. Comparison between the WT and GAMT−/− mice provided strong evidence for three types of contributions to the peak in the Z-spectrum at 1.95 ppm, namely proteins, Cr and PCr, the latter fitted as tCr. A ratio of 20±7% (Protein) and 80±7% tCr was found in brain with 2 μT and 2 s saturation. Based on phantom experiments, the tCr peak was estimated to consist of about 83±5% Cr and 17±5% PCr. Maps for tCr of mouse brain were generated based on the peak at 1.95 ppm after concentration calibration with in vivo MRS.

Keywords: Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST), Creatine, Phosphate Creatine, Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS), Guanidinoacetate N-Methyltransferase deficiency (GAMT−/−), Magnetization Transfer, Lorentzian Line-shape Fitting

Graphical Abstract

Comparison between the CEST Z-spectra recorded on the wild type (WT) mice and one knockout mouse model (GAMT−/−), that has low creatine (Cr) and phosphocreatine (PCr) concentrations in the brain, provided strong evidence for three types of contributions to the peak in the Z-spectrum at 1.95 ppm, namely proteins, Cr and PCr.

INTRODUCTION

CEST MRI, as a novel molecular imaging technique, has drawn great attention in recent years due to its potential to detect low concentration proteins and metabolites in vivo 1-3. The technique has been successfully applied to detect pathological chemical changes in many diseases, such as neurological disorders in human brain 4, animal models of cerebral ischemia 5-7, cancer in both animal models and human 8-14. CEST MRI detects the exchangeable protons present in proteins, and metabolites in vivo, whose chemical shifts are mainly in the offset range of 0 to 5 ppm with respect to the water resonance, such as amide protons around 3.6 ppm, amine groups around 1.5-3 ppm, and hydroxyl groups around 1 ppm 15. The abundant exchangeable protons in tissues cause significant overlap in the Z-spectrum between 0-5 ppm. The situation worsens for the fast-exchanging (exchange rate k >1 kHz) amine and hydroxyl protons, the lines of which broaden and may even coalesce with the water proton resonance at lower fields. In the chemical shift offset range between 0 to 5 ppm, it has been found that non-exchangeable aromatic protons also contribute to the Z-spectra through a relayed Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (rNOE) CEST effect 1,16. Together these factors cause a lack of specificity in the Z-spectrum of endogenous exchanging protons. To date, efforts have been made towards separating amide and aliphatic protons from other contributions by exploiting foremost the abundance of proteins in tissues and the slower exchange rates of amides and rNOEs 5,6,8,17,18. There are several CEST techniques that can detect amide protons and aliphatic protons with reasonable specificity, such as frequency-labeled exchange transfer (FLEX) 19, the three point fitting method 20,21, and the variable delay multi-pulse (VDMP) 22,23 techniques.

Despite significant efforts, the assignment and selective detection of endogenous metabolites in tissue with CEST is still challenging. A rough selectivity can sometimes be achieved by tuning the labeling RF power, frequency, and duration 24-27 for particular metabolites, such as glycogen 28, glycosaminoglycan 29, glutamate 26,30, creatine 27,31, and lactate 32. However, contamination from lipids, proteins, semisolid macromolecules and other metabolites complicate this simplified approach. The chemical exchange rotation transfer (CERT) technique is capable of measuring the creatine (Cr) CEST signal in phantoms at 9.4 Tesla 33-35. Recently, a CEST method that fits the in vivo Z-spectrum using a group of Lorentzian line-shapes 12,13,36 has been proposed, which achieves improved selectivity by partially fitting out the semi-solid tissue component and direct water saturation (DS) 7,12 and avoiding asymmetry analysis based contamination with aliphatic CEST signals.

The CEST Z-spectra recorded on the brain and muscles at low magnetic fields (3T and 7T MRI) and typical B1 values (1 µT or more) are broad and featureless, but estimated maps of changes in Cr concentration in tissue have been published using asymmetry analysis on the CEST Z-spectra 27. However, high-field Z-spectra of the healthy brain show a well-defined peak at 1.95 ppm on top of a broad background 12,13, which offers an opportunity to estimate the contributions from tCr in the CEST Z-spectrum. The broad background is considered to be a combination of DS, semi-solid magnetization transfer contrast (MTC), and several metabolites with fast-exchanging amine protons such as glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), taurine (Tau), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), while the sharper peak in this frequency range has been thought to be mainly from the guanidinium protons of creatine 7,12, considering that the exchange rate of these protons is in the intermediate range in vivo 37,38. One recent study on brain tumors concluded that a significant part of the CEST peak at 1.95 ppm originates from Cr 12. However, it is well known that the metabolites and macromolecules in tumors are significantly different from those of healthy brain tissue 39-41, which complicates the CEST signal detected at 1.95 ppm. Except from comparison studies with phantoms or ex vivo tissue homogenates 42, assignment of Cr has not been validated in vivo and other contributions to the peak may be present.

In this paper, the contribution to the well-defined CEST signal at 1.95 ppm in the Z-spectrum was investigated by comparing wild type (WT) mice with a knockout mice having Guanidinoacetate N-Methyltransferase deficiency (GAMT−/−), which are known to have very low creatine (Cr) and phosphate creatine (PCr) concentrations 43-47. This allowed the total Cr contribution (tCr = Cr + PCr) to be separated out. Assuming the residual stems from guanidinium in mobile proteins (based on phantom data) and using a polynomial background removal method 48 combined in vivo MRS calibration, we derived a quantitative estimation of tCr concentration.

METHODS

MR experiments

All MRI experiments were performed on a horizontal bore 11.7 T Bruker Biospec system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). A 23 mm volume transceiver coil was used for phantom experiments, and MRI images on animals were acquired using a 72 mm quadrature volume resonator as a transmitter, and a four-element (2×2) phased array coil as a receiver. The CEST experiments were performed using continuous wave (CW) CEST saturation pulses with a length of 2 seconds. The saturation offset sweeps were from 1 to 5 ppm at 0.1 ppm increments for both phantoms and mouse brain. In mouse brain study, a 0.05 ppm increment between 1.6 ppm and 2.4 ppm was added, which leads to a scan time of 5 minutes per Z-spectrum. MR images were acquired using a Turbo Spin Echo (TSE) sequence with TR/TE=5 s/3.7 ms, TSE factor=23, slice thickness=2 mm, a matrix size of 64×64 and a resolution of 0.25×0.25 mm2. The B0 field over the mouse brain was adjusted using field-mapping and second-order shimming. A water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) method was applied to check the B0 map after the shimming 49. For the phantom studies, the Z-spectra was adjusted based on the position of the guanidinium peak with respect to the B0 map determined by WASSR. The B0 map on mouse brain is not necessary since the concentration was obtained by the magnitude of the peak at 1.95 ppm. The R1 relaxation times of the mouse brain and phantoms were measured using variable TR (TR = 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3.5, 5, 8 s) with the aforementioned imaging parameters. The in vivo MRS experiments were acquired on a voxel of 2×2×2 mm3 using a STEAM sequence (TE= 3 ms, TM=10 ms, TR=2.5 sec) with outer volume suppression (OVS). Unsuppressed water signal was acquired prior to each MRS experiment with the same parameters as the MRS experiment except that the number of averages was one. First- and second-order shims were adjusted for each VOI using a field-mapping method. The water signal was suppressed by the variable power RF pulses and optimized relaxation delays (VAPOR) method 50. Phantoms with Cr, GABA, Glu, PCr, eggwhite, and hair conditioner (Suave) were selected to represent metabolites found in brain tissue with exchanging protons around 1.95 ppm, as well as mobile protein and semisolid MTC pools 51-53, respectively. Except for the hair conditioner and eggwhite, phantoms were prepared in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), titrated to pH 7.3 (typical brain cellular pH), and transferred to 5 mm NMR tubes. The phantoms were maintained at 37°C during MRI experiments by an air heater.

Animal Studies

The institutional animal care and use committee approved this study. Three adult female BALB/c mice (6 months) as wild type (WT) mice and three GAMT−/− mice (8-12 weeks) were used for the experiments. 1H MRS spectra of both the brain and muscle of GAMT−/− mice have been reported to have greatly reduced levels of tCr compared to WT animals 43-47. While the age is different, the GAMT−/− mice were used to have a model with reduced tCr levels, for which this age group sufficed. The experiments on the brain of WT mice were performed on midbrain and cerebellum. These two brain regions were chosen due to the significantly different tCr concentrations (12.5-13.5 μmol/g for cerebellum, 9-11 μmol/g for midbrain) previously reported 54,55. All animals were induced using 2 % vaporized inhaled isoflurane, followed by 1.5% isoflurane during the MRI scan.

CEST and MRS Quantification

At 1.95 ppm, the water proton Z-spectrum has contributions from DS, and saturation transfer (ST) signal from CEST effects from guanidinium protons, other exchanging protons, and semisolid macromolecules. These contributions add up non-linearly, and to make matters worse, their relative contribution changes with B1 strength and length. In the current study, we employed inverse metric evaluation 20,56-59 to extract the contribution from guanidinium proton CEST signals. In the framework of this method, the CEST effect under a continues wave saturation can be treated as a relaxation process similar to experiments 24,56. Then, the normalized saturation signal Z (i.e. the water saturation signal S normalized by the signal without saturation S0) at each offset is given by 24,56,57

| (1) |

| (2) |

where is the steady state Z-spectrum, is the longitudinal relaxation time of water, is the saturation time, and is the tilt angle of the effective magnetization with respect to the z-axis due to the RF saturation with a nutation frequency of and an offset of . is the water relaxation time under the RF saturation, which has contributions from the effective water relaxation that accounts for the direct saturation effect in Z-spectra and an apparent relaxation term due to all saturation transfer processes in the tissue 57.

| (3) |

where is the measured longitudinal relaxation time of water in the rotating frame without additional solution components. Equation (3) can be correlated with the observed Z-spectrum using Eqs.1–2. When the saturation time is long enough to reach the steady-state condition, the can be calculated from the steady-state CEST signal ( ) using a simple analytical equation resulting from combining equations (2) and (3):

| (4) |

The steady-state condition is determined by , which is usually much faster than the water relaxation rate in the tissue due to the presence of a large MTC pool and the abundant exchanging protons. The of mouse brain was measured at 11.7 T, and was found to be 1.6±0.1 s−1 for 2 μT saturation power at 1.95 ppm offset, which indicates that a saturation time of two seconds is enough to be considered a steady-state condition in mouse brain. As a comparison, the of mouse brain was determined to be 0.55±0.03 s−1 at 11.7 T.

The steady-state Z-spectrum is modulated by the water longitudinal relaxation time R1, and not be linearly dependent on the concentration of exchanging protons 20,56-59. These limitations can be addressed by using Another great advantage of using is that it is a linear superposition for all saturation transfer components when multiple exchanging proton pools are present. For the two-pool situation used in current study, i.e. a guanidinium pool and one background pool that includes all other contributing protons at that frequency in the Z-spectrum, is given by

| (5) |

Importantly, and not fully intuitively, to calculate individual component apparent rate contributions, Eq. 4 has to be applied to each individual component to fulfill the conditions of addition of inverse spectral intensities. Thus

| (6) |

| (7) |

where and are the steady-state CEST signals when only single background or guanidinium pool is present, respectively. Combing Eqs. 4–7, the guanidinium CEST signal can be extracted by fitting the steady-state guanidinium Z-spectrum using

| (8) |

Eq. 8 can be easily extended to the situation with more than two exchanging proton pools. Because of this somewhat complicated arithmetic for spectral intensities, is a better option for the quantification of CEST signals than . Therefore, in the current study, is adopted for the quantification of the guanidinium protons by combing Eqs. 7&8.

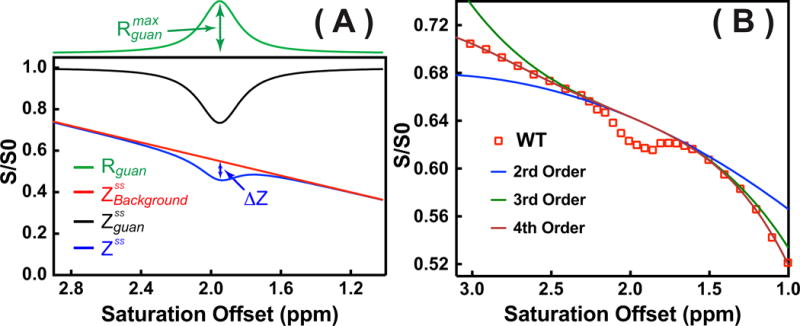

An an example of the observed steady-state Z-spectrum based on assuming two contributions, and , is simulated in Fig. 1. The observed guanidinium CEST signal as well as the maximum , , are indicated in the figure. With the assumption that and , the analytical equation of can be derived from Eq. 8, and is given by

| (9) |

When strong background saturation transfer effects ( ) are present, which is the case for the in vivo CEST experiments, the observed guanidinium peak will be scaled down significantly from the guanidinium Z-spectrum alone ( ) (see Fig.1), which is called a spillover effect. The Z-spectra between 1 - 3 ppm were fitted by assuming two saturation components: a well-defined peak, assigned to guanidinium protons ( ), and the broad background signal including DS and saturation transfer effects from MTC, aromatic protons and other metabolites ( ). These components were fitted using a Lorentzian and a fourth-order polynomial function 48, respectively.

| (10) |

| (11) |

where is the peak full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the Lorentzian line-shape in ppm. is the true apparent relaxation rate contribution of the guanidinium protons. The pure guanidinium state-state CEST signal can be calculated from using the Eq. 7. is the chemical shift of the guanidinium peak, which is around 1.95 ppm in vivo; to terms are the zero to fourth-order polynomial coefficients. A lower order polynomial function (< 4) was not able to fit the in vivo broad spectral background around 2 ppm with enough accuracy as demonstrated in the fitting on a typical Z-spectrum on a mouse brain plotted in Fig. 1B, while a higher order polynomial function may cause over-fitting.

Figure 1.

(A) Example of fitting the Z-spectrum (blue line) consisting of two contributions (Rguan and ) simulated using Eqs. 7,8,10–11. The corresponding calculated from the Rguan using Eq. 7 with R1=0.5 s−1 was also plotted (black line). In the fitting, = 0.2 s−1, w = 0.250 ppm, and 1.95 ppm were used for the Lorentzian line-shape (Rguan), while C0 =0.55, C1=-0.2 were applied for the broad background signal ( ). Other polynomial terms were assumed to be zero in ). ΔZ is the observed pure guanidinium CEST signal. (B) One typical Z-spectrum recorded in WT mouse with 1 μT saturation power and two-second saturation length (Open Square) was plotted together with the fitting using several polynomial functions with different orders (solid lines) defined by Eq. 11.

The fitting of the guanidinium peak was performed by two steps. Firstly, the component was fitted by excluding the CEST data points between 1.6 ppm and 2.4 ppm and varying the parameter . Then, the Z-spectral data points between 1.6-2.4 ppm were fitted by varying the parameters , , and to superimpose the and components using Eqs. 7&8.

Brain tCr concentrations from the in vivo 1H MRS spectra were estimated using LCModel 60,61 analysis. The unsuppressed water signal measured from the same VOI was used as an internal reference for the quantification (assuming 80% brain water content). The following 16 compounds were used for a basis set: alanine (Ala); aspartate (Asp); Cr; GABA; Glu; Gln; glutathione (GSH); glycerophosphorylcholine (GPC); phosphorylcholine (PCho); myo-inositol (Ins); Lac; NAA; phosphorylethanolamine (PE); scyllo-inositol (Si); serine (Ser); and taurine (Tau). The model spectrum of PCr was not included in the fitting and the resulting Cr concentration thus represented tCr. Due to the overlap of Cr and PCr signal in the proton spectrum, the concentration ratio between them is hard to determine by high-resolution in vivo MRS, even with small voxel at high field. In the literature an approximate ratio of 1:1 has been reported for Cr/PCr ratio 54,62-65, which could be used for extracting Cr or PCr concentration in mouse brain. The metabolite concentrations were obtained from the ratio of the metabolite peak area from the LCModel to that of the unsuppressed water signal.

RESULTS

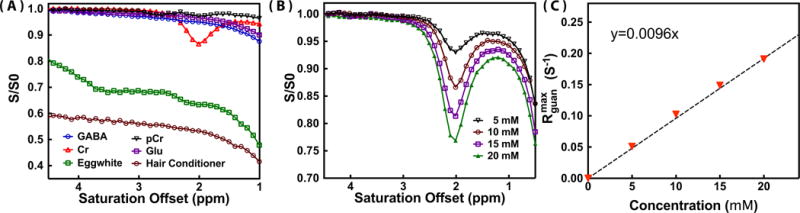

Phantom Experiments

Fig. 2A shows phantom Z-spectra measured for several abundant mouse brain metabolites with CEST signal around 1.95 ppm using a CW-CEST sequence with 2 μT saturation field (tsat = 2 s). The results are similar to previously reported Z-spectra 25,31. At the resonance of 1.95 ppm, Glu, GABA, Cr, MTC (hair conditioner), and mobile protein (egg white) give strong CEST signal, However, most of the metabolites have broad line-shapes, except Cr, PCr and protein guadinium protons, all showing a well-defined resonance at 1.95 ppm. PCr has an additional CEST signal around 2.6 ppm. The values for tCr and PCr CEST at 1.95 ppm were 0.102±0.009 s−1 and 0.020±0.003 s−1 for 10 mM concentration respectively, which translate to 83±5% and 17±5% contributions to tCr under these saturation conditions and a 1:1 Cr/PCr concentration ratio. The values were calculated using Eq. 1 with the measured water longitudinal relaxation time s−1. In the phantoms, the CEST signal can not reach steady-state with two second saturation time. Therefore, the non steady-state equation (Eq. 1) was used for the calculation of . The concentration-dependence of the signal is illustrated in Fig. 2B. For these concentration studies in vitro, the Cr CEST effect ( ) depended linearly on concentration up to about 20 mM (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Z-spectra of (A) Glu (10 mM), PCr (10 mM), Cr (10 mM), GABA (10 mM) solutions, hair conditioner (MTC phantom), and eggwhite (protein phantom) (B) Cr solutions with different concentrations (5, 10, 15 and 20 mM). All data recorded using CW-CEST with a saturation power of 2 μT (tsat = 2 s) for offsets from 1 to 4.5 ppm at 37°C degree. (C) The concentration dependence of the Cr CEST signal . The values were obtained from peak intensities of the guanidinium CEST Z-spectra ( ) and the measured R1 values using Eq. 1. A dashed line (y = 0.0096×) is drawn for visual guidance of the linear dependence range.

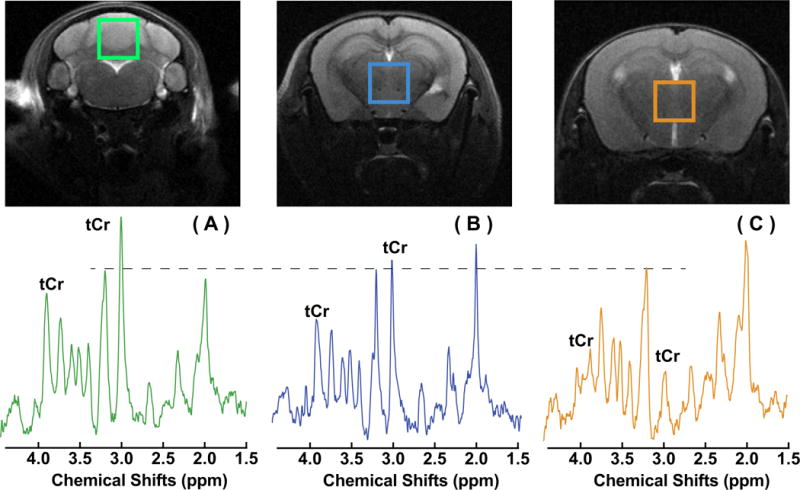

MR of the Mouse Brain

In vivo 1H MR spectra of the WT mouse brain (cerebellar and midbrain regions) and the midbrain of a GAMT−/− mouse are shown in Fig. 3. The high-resolution T2 weighted images acquired with a RARE sequence are also shown for anatomical guidance for reproducible placement of a volume of interest (VOI). The tCr signal in the midbrain of the GAMT−/− mouse shows striking differences with respect to the spectra of the WT mouse, being significantly reduced, both at 3 ppm (p < 0.001) and 3.9 ppm (p < 0.001). Notice that the residual peak at 3.0 ppm is not tCr but due to mobile macromolecules, as resulting from taken these into account in the LC model fitting. On the other hand, LC model based concentrations of GABA and Glu/Gln (Glx) at this frequency did not show significant difference (p=0.93 for Glx, p=0.32 for GABA) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

in vivo 1H NMR spectra measured from regions of the cerebellum in a WT mouse (A), the midbrain in a WT mouse (B), and the midbrain in a GAMT−/− mouse. The peak intensities were normalized to the Cho peak and a dashed line was drawn for visual guidance of the relative peak intensities. The corresponding T2-weighted images of the mouse brain with a RARE sequence with the volumes of interest (VOIs) are plotted on the top of the spectra. RARE MRI: in-plane resolution 100 × 100 μm2, slice thickness 1 mm.

Table 1.

LC_model based tissue concentrations (mM) of brain metabolites with exchangeable protons at 1.95 ppm. Wild type (WT) n=3, GAMT−/− n=3.

| Cerebellum (WT) |

Midbrain (WT) |

Midbrain (GAMT−/−) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Glu+Gln | 19.2±1.3 | 19.5±1.6 | 18.6±0.4 |

| GABA | 3.3±0.6 | 4.3±0.6 | 3.4±0.7 |

| tCr | 17.6±1.9 | 13.7±1.5 | 0.7±0.6*** |

Statistical significance P<0.001

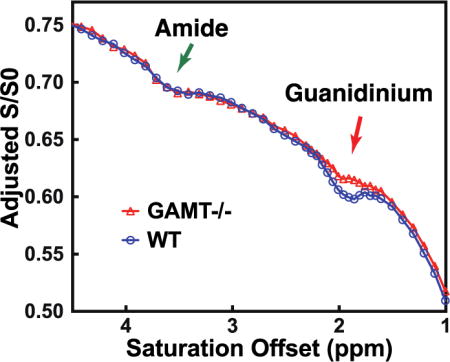

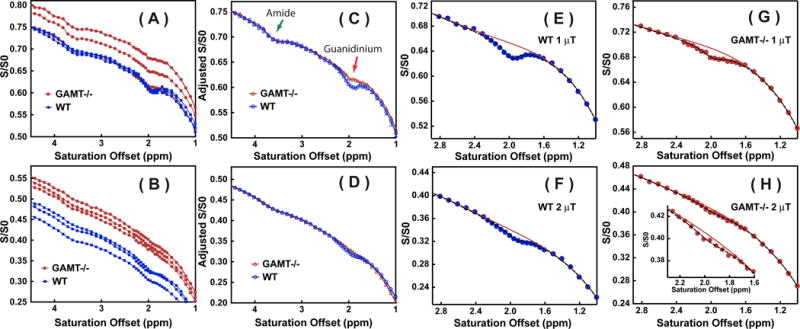

Typical Z-spectra recorded in comparable VOIs are shown for WT and GAMT−/− mouse in Figs. 4A,B. The intensity of the broad background signal differed slightly between the two types of mice, possibly due to different MTC and DS values in the slightly mismatched brain locations. Therefore, Z-spectra were aligned on the intensity scale using the CEST signal from amide protons (3.5 ppm) by translation along the intensity axis. In principle, other offsets far away from 1.95 ppm can also be used for the alignment. The amide proton peak at 3.5 ppm was selected since the peak is helpful in identifying not only the mismatch in intensity between two Z-spectra but also any frequency shift cause by differences in B0 inhomogeneity. The alignment is of high quality visually for the saturation power of 1 μT, as seen from the Z-spectra. But the alignment was more difficult at high saturation power (2 μT), and a slight mismatch was found between the WT and GAMT−/− mice for the 1-1.5 ppm range. Comparison between the two types of mice shows some residual signal at 1.95 ppm in the GAMT−/− mice, while we know from the MRS experiments that there is minimal tCr remaining. This indicates that an appreciable portion of the guanidinium peak at 1.95 ppm is from a different source for the Z-spectra recorded at 1 μT, which, based on the egg white phantom results, we tentatively assign to mobile protein signal. This contribution should not change between mouse types, in line with the similar peak intensity found at the amide proton offset (3.5 ppm) for the WT and GAMT mice (Fig. 4C). However, the protein contribution to the guanidinium peak at the higher saturation power of 2 μT is suppressed significantly as seen from the Z-spectrum on the GAMT mice (Fig. 4H), with tCr thus becoming the dominant component for the peak at 1.95 ppm in the WT mice at such high saturation power (Fig. 4F). The Z-spectra (1-3 ppm) of the brain of WT and GAMT−/− mice together with the fitted Z-spectra using Eqs.7,8,10–11, are plotted in Figs. 4E–H. With a fourth-order polynomial function, the broad background Z-spectra can be well fitted between 1 to 3 ppm.

Figure 4.

Z-spectra recorded in WT mice (n = 3) and GAMT−/− mice (n = 3) for the midbrain VOI in Fig. 3 using CW-CEST with saturation powers of 1 μT (A) and 2 μT (B). The Z-spectra collected at 1 μT (C) and 2 μT (D) aligned with the Z-spectrum of one of the WT mice using the signal at 3.5 ppm as a reference for translation along the intensity scale. Fitted Z-spectra (1-3 ppm range, dashed line) for the brain of a WT (E, F) and a GAMT−/− mouse (G, H) with saturation powers of 1 μT (E, G) and 2 μT (F, H), respectively. The inset in Fig. 4H shows the fitting of the small residual. The solid curves are the polynomial fits of signal around 1.95 ppm.

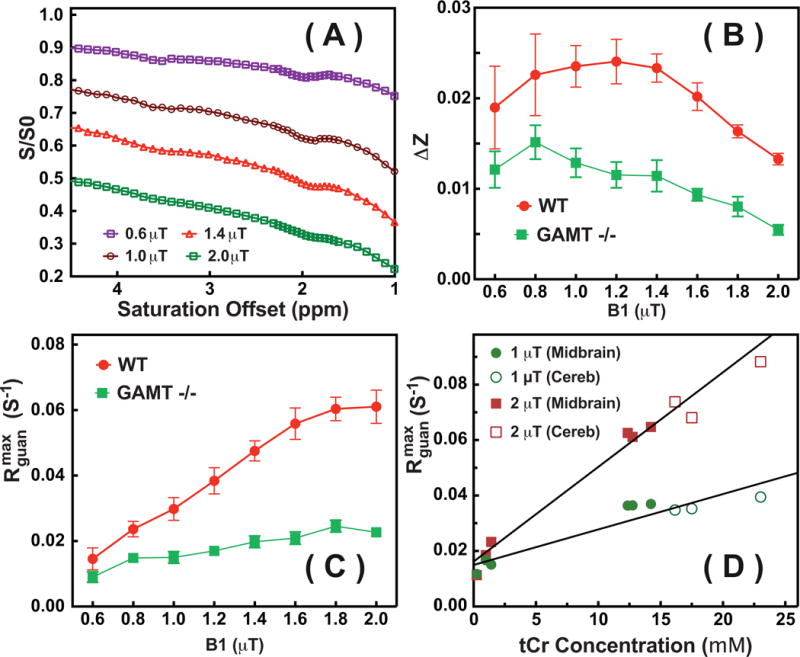

When multiple saturation transfer contributions are present, such as is the case in brain tissues, observation and separation of the guanidinium peak as a function of the saturation power is complicated, because the observed CEST spectrum is not a simple zero-order superposition of all saturation contributions (Eq. 8) 38. The tCr CEST contrast will be scaled down by the spillover effect from the strong background signals from DS and MTC(Eq. 9). In order to determine the optimal saturation power for the in vivo CW-CEST experiments, a series of experiments with different saturation powers were performed on both WT and GAMT −/− mouse brains. Typical Z-spectra of a WT mouse brain as a function of saturation power are plotted in Fig. 5A, while the observed guanidinium CEST signal difference (ΔZ) and calculated results are presented both in Tabl. 2 and Figs. 5B,C. An average relaxation time of R1=0.55±0.03 s−1 for the mouse brain was used in calculating the . The guanidinium CEST signal difference (ΔZ) for WT mouse, which is defined by the difference between the guanidinium maximum signal and the background signal at 1.95 ppm (Fig. 1), increases slightly with saturation power before reaching a maximum around 1.2 μT, and dropping rapidly at higher powers (Fig. 5B), presumably due to the spill-over effect prohibiting accurate quantification. The observed guanidinium CEST signal (ΔZ) was significantly lower for the brains of GAMT−/− mice, and the values predominantly decreased as a function of saturation power. This apparent drop is again due to the dominance of the broad background, similar tot he WT mice at higher power. The results in Fig. 4 clearly show that the component of the guanidinium peak for GAMT−/− mice is much smaller than that of the WT mouse brain. The guanidinium CEST signal peaks obtained by fitting the Z-spectra using Eqs. 7,8,10–11 are presented in Fig. 5C. After spillover correction, this fitted shows a strong increase with respect to saturation power, which is as expected due to higher labeling efficiency.

Figure 5.

(A) Typical Z-spectra on WT mouse brain for the VOIs at midbrain shown in Fig. 3 recorded with different saturation powers (0.6 μT, 1 μT, 1.4 μT and 2 μT). (B) The observed guanidinium CEST difference signal ΔZ and (C) the guanidinium CEST signal ( ) with respect to the saturation power for a WT and a GAMT −/− mouse. The error bar represents the standard deviations over the midbrain region. (D) The fitted peak intensities of the guanidinium CEST signals from the midbrain (solid circles and squares) and cerebellum (open circles and squares) of WT mice (n=3) and from the midbrain region of GAMT−/− mice (n=3) with their corresponding tCr concentrations quantified relative to MRS. Lines are the linear least squares fitted curves, leading to = 0.015 s−1 and s−1mM−1 (R2=0.87) for 1 μT and = 0.016 s−1 and s−1mM−1 (R2=0.94) for 2 μT, respectively.

The fitted can be correlated to the Cr and PCr concentrations from MRS by the relationship:

| (12) |

with the protein signal in (intercept of the curve in Fig. 5D) and and are the apparent relativities that have to be multiplied with the concentrations of Cr and PCr in brain (slope of the curve in Fig. 5D) to get the apparent relaxation contributions. Assuming the PCr to Cr concentration ratio to be constant, Eq. 12 can be simplified to

| (13) |

Using the data in Fig. 5D, = 0.015 s−1 and s−1mM−1 were determined for the 1 μT saturation power, while = 0.016 s−1 and s−1mM−1 were obtained for the 2 μT saturation power. The value of is determined by the protein concentration and saturation power.

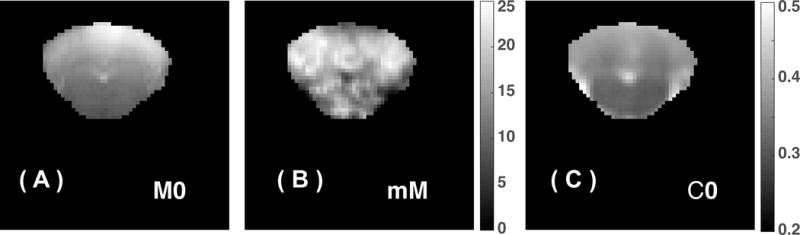

We calculated tCr maps for the cerebellum of the WT mouse brain using Eqs. 7,8,10–11,13, which are shown in Figs. 6. The tCr concentration in the cerebellum region is about 18.7±4 mM, while the tCr concentration is much lower for the medulla (14.1±3 mM). The tCr concentration measured by CEST is slightly higher than the values, 15.5-16.8 mM, determined by MRS technique 54,55. The corresponding C0 maps are also presented. As we discussed in Eq. 11, the C0 map is a combined effect mainly from DS and MTC plus all other saturation transfer processes.

Figure 6.

(A) M0 images, (B) tCr maps, and (C) C0 maps (the zero order coefficient for the polynomial function to fit the CEST background) for the cerebellum of a WT mouse. The maps were calculated pixel-by-pixel by fitting the Z-spectra between 1-3 ppm, recorded using a CW-CEST with a 2 μT saturation power. C0 maps contain contributions mainly from DS and MTC and clearly show strong WM and GM contrast similar to MTC maps.

DISCUSSION

Based on the comparison of brain Z-spectra recorded on the brain of WT mice and mice with GAMT deficiency, this study provides strong evidence that the peak of tCr is the major contributor to the well-defined guanidinium peak at 1.95 ppm in the Z-spectrum. However, there is a significant part of the guanidinium peak from another source, which we attribute to mobile proteins in line with a similar resonance found in egg white phantoms. The ratio between the protein and tCr peak contributions varies with different experimental conditions. The tCr contribution from PCr is expected to be small compared to Cr due to the much slower exchange rate, but could still contribute 17±5% of tCr signal at 2 μT saturation power, as based on our phantom studies under physiological conditions for brain.

The guanidinium peak does not completely arise from tCr, as shown by a small residual guanidinium peak in the Z-spectra from GAMT −/− mouse brains (Fig. 4C) and the non-zero intercept of the correlation analysis between MRS and guanidinium peak (Fig. 5D). The residual may contain signal from the guanidinium, amine or aromatic protons of mobile proteins as confirmed by the Z-spectra of the egg white phantom (Fig. 2A) and a previous study on tumors and tissue homogenates 12,42. The relative contribution of the tCr signal to the guanidinium peak depends on the saturation power. At a saturation power of 1 μT (for the current saturation time of 2 s), the tCr signal was derived to be 65% of the total signal. The tCr contribution to the guanidinium peak increased to 80 ± 7% with 2 μT saturation power, in which Cr contributed 83±5% and PCr contributes 17±5%. Thus, the guanidinium peak of WT mice is dominated by tCr signal at 2 μT saturation power. Therefore, a 2 μT saturation power is suggested for the future studies to have a relatively clean (80%) tCr signal. The current study suggests that the detection of Cr in the brain has to take into account the contributions from the mobile proteins. During the time of revising the current paper, a comparison study on the tissue homogenates of rat brain was published, and suggested that the protein contributions about 34% to the peak at 1.95 ppm (1 μT and 5 s CW-CEST), which perfectly matches with our finding at 1 μT (35%) 42. This study thus verifies our quantification method and results. Our results also show that the CEST signal of the guanidinium protons in the protein increases much less as a function of saturation power than that of tCr as judged from Fig. 5C. This suggests that the exchange rates of the guanidinium protons in the proteins are much lower than those in creatine. This property is helpful for us to design methods to suppress the protein contamination in the tCr mapping. The contributions of mobile protein and tCr to the CEST signal depend on pH, temperature and saturation parameters used as discussed above. Therefore, the calibration of tCr by MRS using Eq. 13 may not be valid when the ratio PCr and Cr changes during energy use such as for brain activity or, in muscle, for exercise.

The extraction of the total creatine signal in the current study provides an opportunity to estimate the contribution of tCr in the conventional asymmetry analysis method, i.e. where are the saturated signal intensities at ±2 ppm 27,31,35. The CEST contrast due to tCr at 1.95 ppm is measured to be about 1.3±0.1 % of the water signal in the WT mouse brain (2 μT and 2 s length, Fig. 5B). The majority of the saturation effects at 1.95 ppm (about 77 % of the signal) derives from DS, aromatic protons and amine/guanidinium protons of proteins, and MTC. When performing an asymmetry analysis on the CEST Z-spectra, the was found to be 5.2±0.5 % (2 μT and 2 s length), while the tCr signal is not reduced by the asymmetry analysis. Therefore, the conventional MTRasym is an efficient way to remove DS and the symmetric part of MTC, which constitute the majority of the contaminations to the tCr signal in brain, but still relatively large contributions exist on the order of magnitude of the tCr signal.

Compared to the conventional Lorentzian line-shape fitting method or asymmetry analysis method, the current simple approach not only provides a cleaner tCr mapping, but also shortens the total experimental time by acquiring a small portion of the full Z-spectra (1-4.5 ppm). When acquiring the concentration map of tCr, a B0 map on mouse brain is not necessary since the concentration was obtained from the extracted guanidinium peak at 1.95 ppm ( ) based on the maximum of the peak fit on the observed guanidinium CEST signal (ΔZ). Although the calibration method was demonstrated only for brain, it is expected that it could also be used to estimate and map tCr in muscle 38. In the skeletal muscle the concentrations of Cr and PCr are on the order of 7 mM 66 and 20-30 mM 67, respectively, and thus tCr is significantly higher than in brain. Furthermore, the MTC is close to symmetric in the muscle, which is different from the line-shape of the MTC in the brain68. Then, the conventional MTRasym method may be a simple and valid approximation to suppress the majority of the DS and MTC contaminations. However, there is a large signal contribution from the OH groups of glycogen and it is unclear how much signal from mobile protein would be there. The exchange rate of OH is however much higher and it may be possible to separate guanidinium protons and OH protons using rate-based editing approaches.

The current approach is ready to be transferred to high-field clinical scanners, such as 7T scanners. When the magnetic field is reduced to 3T, the exchange rate of creatine can no longer be considered to be in the intermediate exchange range. The guanidinium peak of Cr coalesces with water peaks due to reduced shift difference at these lower fields, and overlaps with many other exchanging protons. Then, the separation of the Cr signal will be very challenging, but the extraction of PCr may still be feasible due to its much slower exchange rate25.

CONCLUSION

In this work, a peak-fitting scheme assuming a two-pool model was used to estimate the Cr/PCr contributions to the CEST Z-spectra of mouse brain at 11.7T. CEST spectra from WT and GAMT deficient mouse brain revealed that the guanidinium peak at 1.95 ppm is from both tCr and a residual, assigned to mobile proteins. The ratio of these contributions depends on the saturation power. Quantitative tCr maps may be generated using the fitted peak of the guanidinium signal in the CEST spectrum after calibration using in vivo MRS.

Table 2.

The and at 1.95 ppm for the midbrain of GAMT and WT mice measured with different saturation powers. The calculated values using Eqs.7&8 are also listed.

| Power (μT) | WT | GAMT−/− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

|

|

(10−2) | (10−2) |

|

(10−2) | (10−2) | ||

|

| |||||||

| 0.6 | 0.804±0.02 | 1.9±0.5 | 1.6±0.4 | 0.821±0.02 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 | |

| 0.8 | 0.718±0.02 | 2.3±0.5 | 2.4±0.4 | 0.736±0.02 | 1.5±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | |

| 1.0 | 0.659±0.02 | 2.4±0.2 | 3.0±0.4 | 0.665±0.02 | 1.3±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | |

| 1.2 | 0.608±0.03 | 2.4±0.3 | 3.6±0.4 | 0.569±0.03 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.7±0.1 | |

| 1.4 | 0.536±0.03 | 2.3±0.2 | 4.5±0.3 | 0.505±0.03 | 1.1±0.2 | 2.2±0.2 | |

| 1.6 | 0.473±0.04 | 2.0±0.2 | 5.0±0.5 | 0.435±0.04 | 0.9±0.1 | 2.3±0.2 | |

| 1.8 | 0.409±0.04 | 1.6±0.1 | 5.4±0.4 | 0.391±0.04 | 0.8±0.1 | 2.6±0.2 | |

| 2.0 | 0.364±0.04 | 1.3±0.1 | 5.5±0.4 | 0.351±0.04 | 0.5±0.1 | 2.3±0.2 | |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01EB015032, P41EB015909, R01EB019934 and R01HL63030; National Natural Science Foundation of China 11474236.. Lin Chen thanks the China Scholarship Council (201506310130) for financial support. The authors thank Dirk Isenbrandt for creating and providing the GAMT−/− mice, and Mary McAllister for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- CEST

chemical exchange saturation transfer

- MTC

magnetization transfer contrast

- rNOE

relayed nuclear Overhauser enhancement

- FLEX

frequency-labeled exchange transfer

- VDMP

variable delay multi-pulse sequence

- ppm

parts per million

- CERT

chemical exchange rotation transfer

- RF

radiofrequency

- DS

direct water saturation

- FOV

field of view

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- WASSR

water saturation shift referencing

- ROI

region of interest

- GAMT−/−

Guanidinoacetate N-Methyltransferase deficiency

- OVS

outer volume suppression

- VAPOR

variable power RF pulses and optimized relaxation delays

- ST

saturation transfer

- WT

wild type mouse

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

References

- 1.van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): What is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(4):927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherry AD, Woods M. Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2008;10(1):391–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu G, Song X, Chan KW, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(7):810–828. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Peng S, Wang R, et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer MR imaging of Parkinson’s disease at 3 Tesla. European radiology. 2014;24(10):2631–2639. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3241-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou J, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PC. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med. 2003;9(8):1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Sun W, Huang J, van Zijl PCM. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;27(6):1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin T, Wang P, Zong X, Kim S-G. Magnetic resonance imaging of the Amine–Proton EXchange (APEX) dependent contrast. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1218–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PCM. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(6):1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia G, Abaza R, Williams JD, et al. Amide proton transfer MR imaging of prostate cancer: a preliminary study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(3):647–654. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan KWY, McMahon MT, Kato Y, et al. Natural D-glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(6):1764–1773. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue MJ, Donahue PC, Rane S, et al. Assessment of lymphatic impairment and interstitial protein accumulation in patients with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema using CEST MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai K, Singh A, Poptani H, et al. CEST signal at 2ppm (CEST@2ppm) from Z-spectral fitting correlates with creatine distribution in brain tumor. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desmond KL, Moosvi F, Stanisz GJ. Mapping of amide, amine, and aliphatic peaks in the CEST spectra of murine xenografts at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(5):1841–1853. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen LQ, Pagel MD. Evaluating pH in the Extracellular Tumor Microenvironment Using CEST MRI and Other Imaging Methods. Adv Radiol. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/206405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Zijl PCM, Sehgal AA. Proton Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) MRS and MRI. eMagRes. 2016;5(2) doi: 10.1002/9780470034590.emrstm9780470031482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaiss M, Windschuh J, Goerke S, et al. Downfield-NOE-suppressed amide-CEST-MRI at 7 Tesla provides a unique contrast in human glioblastoma. Magn Reson Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou J, Tryggestad E, Wen Z, et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat Med. 2011;17(1):130–134. doi: 10.1038/nm.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones CK, Huang A, Xu J, et al. Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in the human brain at 7T. NeuroImage. 2013;77C:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yadav NN, Jones CK, Hua J, Xu J, van Zijl PC. Imaging of endogenous exchangeable proton signals in the human brain using frequency labeled exchange transfer imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(4):966–973. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J, Zaiss M, Zu Z, et al. On the origins of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast in tumors at 9.4 T. NMR Biomed. 2014 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zong X, Wang P, Kim SG, Jin T. Sensitivity and source of amine-proton exchange and amide-proton transfer magnetic resonance imaging in cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):118–132. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Yadav NN, Bar-Shir A, et al. Variable delay multi-pulse train for fast chemical exchange saturation transfer and relayed-nuclear overhauser enhancement MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(5):1798–1812. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Yadav NN, Zeng H, et al. Magnetization transfer contrast–suppressed imaging of amide proton transfer and relayed nuclear overhauser enhancement chemical exchange saturation transfer effects in the human brain at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(1):88–96. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin T, Autio J, Obata T, Kim S-G. Spin-locking versus chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI for investigating chemical exchange process between water and labile metabolite protons. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1448–1460. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JS, Xia D, Jerschow A, Regatte RR. In vitro study of endogenous CEST agents at 3 T and 7 T. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):302–306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haris M, Singh A, Cai K, et al. A technique for in vivo mapping of myocardial creatine kinase metabolism. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):209–214. doi: 10.1038/nm.3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(7):2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis KA, Nanga RP, Das S, et al. Glutamate imaging (GluCEST) lateralizes epileptic foci in nonlesional temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(309):309ra161. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haris M, Nanga RP, Singh A, et al. Exchange rates of creatine kinase metabolites: feasibility of imaging creatine by chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(11):1305–1309. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeBrosse C, Nanga RP, Bagga P, et al. Lactate Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (LATEST) Imaging in vivo A Biomarker for LDH Activity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19517. doi: 10.1038/srep19517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zu Z, Janve VA, Li K, Does MD, Gore JC, Gochberg DF. Multi-angle ratiometric approach to measure chemical exchange in amide proton transfer imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(3):711–719. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zu Z, Janve VA, Xu J, Does MD, Gore JC, Gochberg DF. A new method for detecting exchanging amide protons using chemical exchange rotation transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(3):637–647. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zu Z, Louie EA, Lin EC, et al. Chemical exchange rotation transfer imaging of intermediate-exchanging amines at 2 ppm. NMR Biomed. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou IY, Wang E, Cheung JS, Zhang X, Fulci G, Sun PZ. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI of glioma using Image Downsampling Expedited Adaptive Least-squares (IDEAL) fitting. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):84. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goerke S, Zaiss M, Bachert P. Characterization of creatine guanidinium proton exchange by water-exchange (WEX) spectroscopy for absolute-pH CEST imaging in vitro. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(5):507–518. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rerich E, Zaiss M, Korzowski A, Ladd ME, Bachert P. Relaxation-compensated CEST-MRI at 7 T for mapping of creatine content and pH--preliminary application in human muscle tissue in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(11):1402–1412. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu J, Li K, Zu Z, Li X, Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of rodent glioma using selective inversion recovery. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(3):253–260. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dowling C, Bollen AW, Noworolski SM, et al. Preoperative proton MR spectroscopic imaging of brain tumors: correlation with histopathologic analysis of resection specimens. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(4):604–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Majos C, Julia-Sape M, Alonso J, et al. Brain tumor classification by proton MR spectroscopy: comparison of diagnostic accuracy at short and long TE. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(10):1696–1704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang XY, Xie J, Wang F, et al. Assignment of the molecular origins of CEST signals at 2 ppm in rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renema WK, Schmidt A, van Asten JJ, et al. MR spectroscopy of muscle and brain in guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT)-deficient mice: validation of an animal model to study creatine deficiency. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(5):936–943. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skelton MR, Schaefer TL, Graham DL, et al. Creatine transporter (CrT; Slc6a8) knockout mice as a model of human CrT deficiency. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulze A. Creatine deficiency syndromes. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;113:1837–1843. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stockler S, Holzbach U, Hanefeld F, et al. Creatine deficiency in the brain: a new, treatable inborn error of metabolism. Pediatr Res. 1994;36(3):409–413. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199409000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kan HE, Meeuwissen E, van Asten JJ, Veltien A, Isbrandt D, Heerschap A. Creatine uptake in brain and skeletal muscle of mice lacking guanidinoacetate methyltransferase assessed by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102(6):2121–2127. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01327.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lauzon CB, van Zijl P, Stivers JT. Using the water signal to detect invisible exchanging protons in the catalytic triad of a serine protease. J Biomol NMR. 2011;50(4):299–314. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9527-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tkac I, Starcuk Z, Choi IY, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain at 1 ms echo time. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(4):649–656. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<649::aid-mrm2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varma G, Duhamel G, de Bazelaire C, Alsop DC. Magnetization transfer from inhomogeneously broadened lines: A potential marker for myelin. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malyarenko DI, Zimmermann EM, Adler J, Swanson SD. Magnetization transfer in lamellar liquid crystals. Magn Reson Med. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu J, Chan KW, Xu X, Yadav N, Liu G, van Zijl PC. On-resonance variable delay multipulse scheme for imaging of fast-exchanging protons and semisolid macromolecules. Magn Reson Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tkac I, Henry PG, Andersen P, Keene CD, Low WC, Gruetter R. Highly resolved in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the mouse brain at 9.4 T. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):478–484. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cudalbu C, Craveiro M, Mlynarik V, Bremer J, Aguzzi A, Gruetter R. In Vivo Longitudinal (1)H MRS Study of Transgenic Mouse Models of Prion Disease in the Hippocampus and Cerebellum at 14.1 T. Neurochem Res. 2015;40(12):2639–2646. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Exchange-dependent relaxation in the rotating frame for slow and intermediate exchange – modeling off-resonant spin-lock and chemical exchange saturation transfer. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(5):507–518. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaiss M, Bachert P. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and MR Z-spectroscopy in vivo: a review of theoretical approaches and methods. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58(22):R221–269. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/22/R221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zaiss M, Xu J, Goerke S, et al. Inverse Z-spectrum analysis for spillover-, MT-, and T1 -corrected steady-state pulsed CEST-MRI--application to pH-weighted MRI of acute stroke. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(3):240–252. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryoo D, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Detection and Quantification of Hydrogen Peroxide in Aqueous Solutions Using Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer. Anal Chem. 2017;89(14):7758–7764. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):672–679. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(4):260–264. doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mlynarik V, Cudalbu C, Xin L, Gruetter R. 1H NMR spectroscopy of rat brain in vivo at 14.1Tesla: improvements in quantification of the neurochemical profile. J Magn Reson. 2008;194(2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duarte JM, Lei H, Mlynarik V, Gruetter R. The neurochemical profile quantified by in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy. Neuroimage. 2012;61(2):342–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kulak A, Duarte JM, Do KQ, Gruetter R. Neurochemical profile of the developing mouse cortex determined by in vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy at 14.1 T and the effect of recurrent anaesthesia. J Neurochem. 2010;115(6):1466–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lei H, Poitry-Yamate C, Preitner F, Thorens B, Gruetter R. Neurochemical profile of the mouse hypothalamus using in vivo 1H MRS at 14.1T. NMR Biomed. 2010;23(6):578–583. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kushmerick MJ, Moerland TS, Wiseman RW. Mammalian skeletal muscle fibers distinguished by contents of phosphocreatine, ATP, and Pi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(16):7521–7525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallimann T, Wyss M, Brdiczka D, Nicolay K, Eppenberger HM. Intracellular compartmentation, structure and function of creatine kinase isoenzymes in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands: the ‘phosphocreatine circuit’ for cellular energy homeostasis. Biochem J. 1992;281(Pt 1):21–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2810021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu J, DeMarco V, Pokkali S, et al. In situ pH effects within Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infected Mice revealed by UTE-CEST MRI; Paper presented at: ISMRM2015; Singapore. [Google Scholar]