Abstract

In this study, electrolytically deposited strongly adherent silver nanoparticles on stainless steel (SS) implants were used for in situ osteomyelitis treatment. Samples were heat treated to enhance adhesion of silver on 316L SS. Ex vivo studies were performed to measure silver release profiles from the 316L SS screws inserted in equine cadaver bones. No change in the release profiles of silver ions were observed in vitro between the implanted screws and the control. In vivo studies were performed using osteomyelitic rabbit model with 3 mm diameter silver deposited 316L SS pins at two different doses of silver - high and low. Infection control ability of the pins for treating osteomyelitis in a rabbit model was measured using bacteriologic, radiographic, histological and scanning electron microscopic studies. Silver coated pins, especially high dose, offered a promising result to treat infection in animal osteomyelitis model without any toxicity to major organs.

Keywords: Silver nanoparticle, osteomyelitis, stainless steel implants, fracture management, infection control

1.0 Introduction

Osteomyelitis, an infective condition of the bone or bone marrow, is a severe and challenging setback in bone surgery. Various factors that can adversely influence osteomyelitis include poor surgical conditions that are typically seen in trauma cases, patient's habits such as smoking and drug addiction and patients' health such as malnutrition and other immune deficiency disorders.1,2 Further, it has been observed that incidence of infection rate is between 5 to 10% of all inserted internal fixation devices; generally minor, between 0.5 to 2%, in closed fractures but as high as 30% for fixation of grade 3 open fractures.3 Children mostly suffer from acute haematogenous osteomyelitis involving metaphysis of long 4 whereas adults are the victim of subacute and chronic forms of osteomyelitis. Generally, osteomyelitis is commonly seen secondary to an open wound, most frequently an open injury to bone and surrounding soft tissues. 5,6 The incidence of deep musculoskeletal infection is reported to be as high as 23 % from open fractures. 7 Patient related factors than can further complicate this challenge include altered neutrophil defence, humoral and cell-mediated immunity. In a recent study, S. aureus was concluded to be the most common organism isolated (43%) for osteomyelitis followed by P. aeruginosa (10%), Proteus spp. (6%), Klebsiella spp. (5%), E.coli (5%), Enterobacter spp. (3%), S. epidermidis (4%), Streptococcus pyogenes (2%) and Enterococcus spp. (2%).8 Removal of the implant and dead tissue management are really the only satisfactory treatment options available at present in a clinical setting.

Antibiotics have been the go to remedy for such infections, but the use of antibiotics to prevent orthopaedic surgical infections has been met with limited success over the years. Limited success has also been seen with non-antibiotic remedies such as chlorohexidine or nitrofurazone.9 As an alternative therapy, use of silver as an antibiotic has come into wide use particularly in topical treatments. The use of silver has been seen for over thousands of years in many different civilizations. The effectiveness of silver relates to its broad spectrum of activity and its high chemotherapeutic ratio which is defined by the ratio of toxic dose to effective dose. Silver is biocidal in the ionic form.10,11 Also, silver tends to show toxic effects towards microorganisms as compared to normal human cells and tissues.12-15 Silver has also been used in FDA approved devices, but mostly for short term use in medical devices such as catheters. The key challenges to such an idea relates to maintaining effective silver concentration that is toxic to microorganisms but safe to normal healthy tissues, and long term site-specific delivery. Over the years, use of silver directly or indirectly using various technologies have been researched upon showing the prevention of bacterial adhesion and emphasizing on its antimicrobial properties.16-18 Previously, research has been performed in our group showing the effects of silver in various forms by directly depositing it on the surface as a strong adherent antimicrobial coating.1,13,19,20,21 Recently, we have received our patent focusing on this technology from the United States Patent and Trademark Office.22

Due to its good mechanical properties, corrosion resistance and low cost, stainless steel is commonly used as standard implant material for fracture management. 316L SS, where “L” stands for extra low carbon, composition in particular is widely used for fracture management devices as it does not bond with the bone which is an important factor taken into consideration.1 Once a fracture is healed, many times the fracture management device such as a plate or nail needs to be taken out without damaging the fracture site.1 However, for longer term implants that stay in the body such as hip and knee implants, typically titanium (Ti) and its alloys or CoCrMo are used in which good bone bonding ability is must to prevent implant loosening.

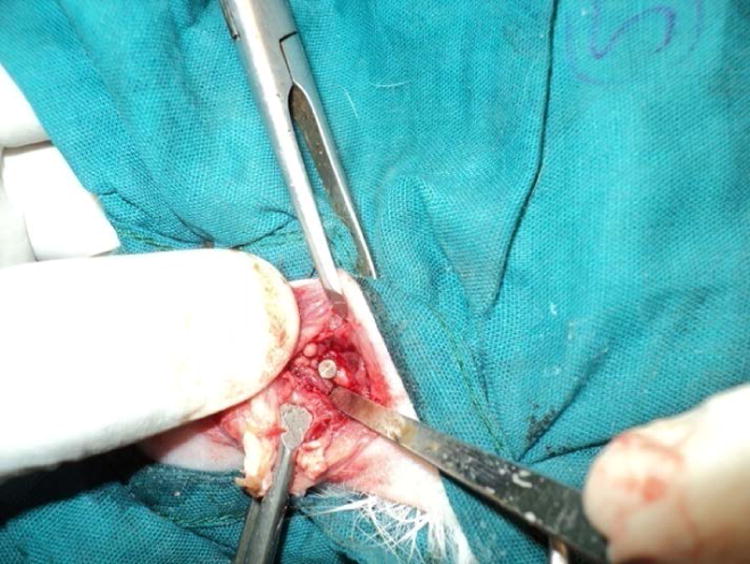

The current work emphasises on silver nanoparticle deposited 316L SS implants for in situ treatment of osteomyelitis in vivo. Nanoparticulate silver coatings were applied to 316L SS devices using an electrodeposition process. It should be taken into consideration that a wide range of experiments were performed during this process to find a suitable parameter for the silver deposition process. The adherence of silver to SS substrate was tested ex vivo by carrying out a silver release study with and without implantation into cadaver bone for a period of 7 days. The influence of silver coating for treating osteomyelitis in a rabbit model, shown in Fig 1, was evaluated by implanting samples into osteomyelitic rabbit femurs for a period of 42 days. Infection control ability of the silver coated pins was measured using bacteriologic, radiographic, histological and scanning electron microscopic studies. The main focus of this work demonstrates how strongly adherent nanoparticulate silver coatings can be added to an orthopaedic device which when placed in an infected site can still prevent infection. Our emphasis is based on our recently patented work which focuses on this technology22 and not to demonstrate the antimicrobial nature of silver which has been well established through many previous works.16-20 In our case, in a rabbit model, within 42 days, such infection was cured, with high dose of silver showing good signs of curing infection as early as 21 days which is certainly not trivial.23-26

Figure 1.

Photograph showing implantation of implant in distal femur of rabbit.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Nanoparticulate silver deposition on 316L SS

Commercially available medical grade 316L SS screws of 2.7mm in diameter and 16mm in length were used for the ex vivo study. Samples were cleaned with DI water and ethanol prior to electrodeposition. An aqueous solution of 0.1M AgNO3 was used as an electrolyte for the process of electrodeposition and platinum foil was used as the anode material with the sample being the cathode. The electrodeposition was performed using a DC power supply (Hewlett Packard 0–60 V/0–50 A, 1000 W) maintaining the voltage constant at 5V for 40-45sec at room temperature which resulted in a DC current in the range of 0.01-0.05A. Post deposition, the excessively loose silver particles resulting from the coating were gently wiped off from the surface using a tissue and DI water. Heat treatment at 500°C for 7 min under air atmosphere was performed using a vertical tube furnace and then the samples were cooled naturally at room temperature1,21. The process parameters were optimized after several experiments by varying the electrolyte concentration, electrodeposition time, and heat treatment conditions to achieve a nano-particulate silver coating strongly adherent to the 316L SS surface1,13. Silver dose can be controlled varying electrodeposition time. For 316L SS pins for in vivo rabbit studies, 45 sec (low dose) and 2 minutes (high dose) of electrodeposition times were used.

Characterization of the samples was performed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200, FEI Inc., OR, USA) held at an operating voltage of 20 kV. SEM images of the silver deposited samples were taken at regular intervals to optimize silver deposition parameters. Post heat treatment samples were cleaned with DI water before microscopic analysis. To confirm the coating is in nanoparticle range particle size analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

2.2 Ex vivo silver release study in DI water

Nano-particulate silver deposited 316L SS screws were placed in DI water for 7 days to study the release kinetics of silver upon implantation and cumulative silver release profiles were measured using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS, Shimadzu AA-6800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Fresh DI water was replaced after each time point. Silver deposited screws (performed under similar conditions) were studied under two different conditions only for low dose concentration– 1) screws implanted into an equine cadaver bone mimicking the surgical implantation procedure and 2) screws without the implantation, which was used as a control. Upon completion, the solution was analysed for Ag+ content using the AAS. The samples were tested in “Flame Mode” using air and acetylene (C2H2) fuel, and data collection was carried out using Shimadzu WizAArd software. The machine was calibrated using Ag+ standards (High-Purity Standards, Charleston, SC, USA) of known concentrations from 0 to 5μg/ml. During testing a pre-spray time of 30s and an integration time of 10s were used. A release study of low and high dose of silver was also performed in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) solution to identify the release profiles of both the doses. The release study was performed in a similar manner as mentioned above and at each point fresh solution was replaced.

2.3 In vivo study in a rabbit model

Bacterial Isolate

Staphylococcus aureus was used for experimental model in rabbit. ATCC S. aureus culture (ATCC 29213) of 1 ml (5×106 CFU/mL) was injected into the medullary cavity of rabbit femur for successful induction of osteomyelitis and colony of the Staphylococcus aureus was confirmed by growth in manitol salt agar and other biochemical tests. Construction of successful osteomyelitic rabbit model using similar methods has been performed before and can be verified from our previous work.52, 53

In vivo study

All animal experimentations were performed in accordance to the standards of the Institutions Animal Ethical Committee of the West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences, India. Bone infection was induced in the femur (bilaterally) of fifteen rabbits of 2-2.5 kg body weight under xylazine and ketamine hydrochloride anaesthesia. Under strict aseptic measures, the medullary cavity of femurs was approached by a small incision followed by drilling using a 1.2 mm diameter drill and 1 ml of bacterial suspension (approximately 3 × 106 CFU) Staphylococcus aureus was injected. The opening of drilled hole was closed using bone wax to prevent leakage of bacterial suspension into surrounding soft tissues. All the animals were observed for 3 weeks for development of osteomyelitis. Carprofen (4 mg/kg of body weight), a standard postoperative pain medication was used for 3 days. The development of osteomyelitis was confirmed by random radiography and selective histology and microbiological examination of swab from bone specimens of sacrificed rabbits (3 animals). After confirmation, a second surgery was done maintaining all standard formalities of surgery and silver-coated (both low and high dose) and uncoated stainless steel implants were placed in the osteomyelitic bone, shown in Fig 1. All the samples were properly sterilized by autoclaving them at 121°C for 1 hr. The detailed experimentation with these animals has been shown in Table 1. The study samples were retrieved on days 21 and 42 post osteomyelitis development. Bone specimens containing the implants were decalcified in Goodling and Stewart's fluid-containing formic acid 15 ml, formalin 5 ml and distilled water 80 ml solution. Histological examinations were carried out using haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections. Sequential radiographs (X-rays) from the infected bone were taken after osteomyelitis development and also from control and treated bone at 3 weeks and 6 weeks. Implanted bones were also collected for SEM analysis from all the three groups (control, low and high dose silver coating) after 21 and 42 days. The specimens were first fixed in E. M. grade 5% glutaraldehyde phosphate solution followed by washing twice for 30 min. with PBS (pH 7.4) and distilled water. Dehydration of the samples was performed using a series of graded ethanol and finally with hexamethyldisilizane (HMDS) for final drying. Gold sputtered coating (JEOL ion sputter, Model JFC 1100, Japan) was performed on samples to make it conductive. The samples were then mounted into the resin and its surfaces were then examined under SEM (JEOL JSM 5200 model, Japan). After 21 days of post-induction of osteomyelitis, swab samples were also taken for microbiological examination for confirmation of osteomyelitis. Toxicological study of silver concentrations in major organs like heart, kidney and liver was carried out at day 42 only.

Table-1. Design of Experiment for In Vivo Animal Experimentation.

| Groups | No of animals | Implant | Days of experiment | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 3 | No implants | 3 weeks | Three animals were sacrificed for histological, radiographic and microbiological examination to confirm development of osteomyelitis |

| Group II | 6 | Uncoated metal implants (control) in one femur and low dose silver coating pin in another femur |

After 3 weeks | Three animals were sacrificed for post-operative characterization |

| After 6 weeks | Three animals were sacrificed for post-operative characterization | |||

| Group III | 6 | Uncoated metal implants (control) in one femur and high dose silver coating pin in another femur |

After 3 weeks | Three animals were sacrificed for post-operative characterization |

| After 6 weeks | Three animals were sacrificed for post-operative characterization |

3.0 Results

3.1 Characterization of nano-particulate silver deposited 316L SS

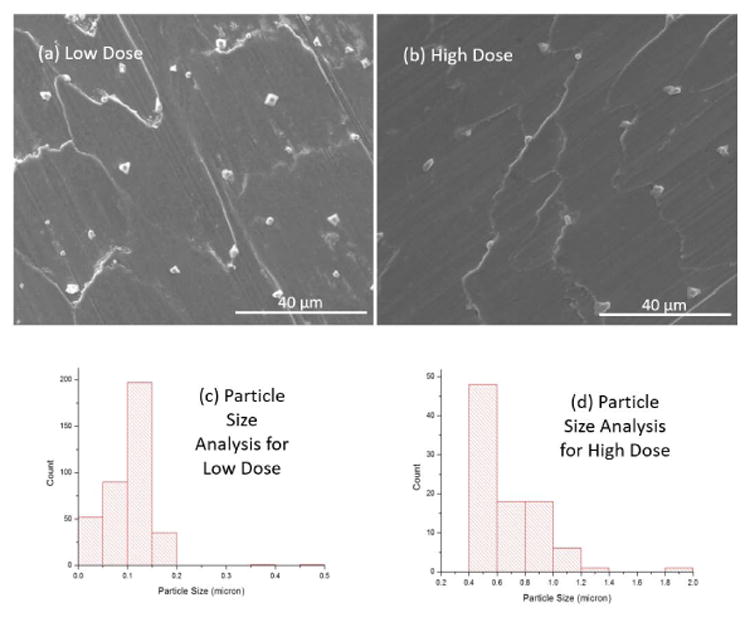

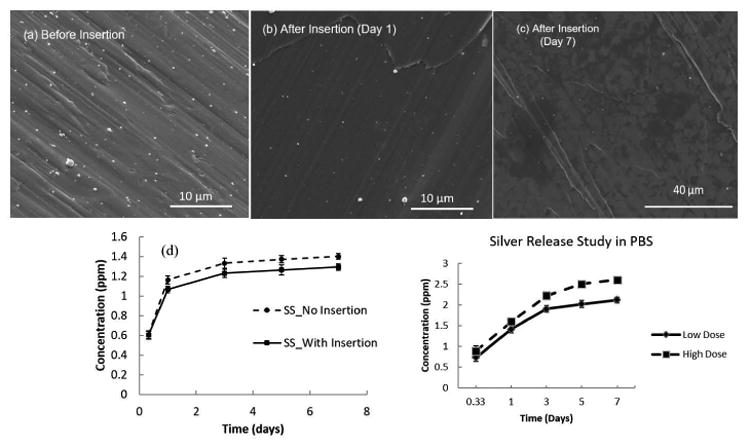

Fig. 2a and b show scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of deposited silver on the surface of 316L SS screws using low and high dose of silver. The deposition resulted in a range of silver particles from nano to micro-meter sizes and proper measures were taken to remove the loosely adhered large particles on the surface by cleaning with DI water. Electrodeposition parameters were optimized to ensure that the deposition resulted with majority of the particles in the nanometer range. No significant differences can be seen in terms of silver particle size and distribution after the implantation due to strong adhesion of silver particles on 316L SS surface. Such result is important to alleviate the concerns related to dislodging of silver particles due to friction and wear at the bone-SS screw interphase during surgical procedure. In order to confirm the nanoparticle coating of silver particle size analysis of the coating was performed for low and high dose of silver as shown in Fig. 2c and d. Fig. 3a and b shows the before and after implantation SEM images of silver deposited 316L SS screw surface.

Figure 2.

SEM images showing the electrodeposition of silver particles (a) before insertion to equine cadaver bone; (b) after insertion and (c) After 7 days in media. Presence of silver particles on the surface can be seen in all the cases. (d) Cumulative release profiles from silver electrodeposited 316L SS screws for 7 days with insertion and without insertion into the equine cadaver bone.

Figure 3.

SEM images showing the electrodeposition of silver particles (a) before insertion to equine cadaver bone; (b) after insertion and (c) After 7 days in media. Presence of silver particles on the surface can be seen in all the cases. (d) Cumulative release profiles from silver electrodeposited 316L SS screws for 7 days with insertion and without insertion into the equine cadaver bone performed in DI water. (e) Cumulative silver release profiles of stainless steel screws with low and high dose silver deposition for 7 days without insertion in PBS (Phosphate Buffer Saline).

3.2 Silver release study

Silver deposited screws were implanted into the equine cadaver bone and the release of silver ions in DI water before and after implantation were studied for 7 days. Only screws with low dose concentration was considered for the ex vivo release study. Fig. 3c shows the SEM image of the 316L SS surface after 7 days of release study, clearly showing the presence of nano-scale silver particles on the surface. This image strong adhesion of particles to the surface as well as long term silver release ability from the device. Fig. 3d shows the release profiles of the silver ions when implanted into the cadaver bone ex vivo, and without implantation i.e., as control. No significant changes in the release profiles can be seen due to ex vivo implantation. Also, an initial fast release rate in the first 3 days can be observed after which silver release rate gradually decreases in both cases. The total cumulative release observed for silver ions in both cases are within the potential toxic limit of 10 ppm (μg/ml) mentioned for the human cells1, a key factor dealing with silver technologies. Similar 7-day release study was performed for low and high dose coated silver in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) solution to get an idea of both the doses of release profiles in buffered saline environment. The cumulative release of silver ions in both doses was within the toxic limit mentioned for human cells i.e. 10 ppm (μg/ml) as shown in Fig. 3e.1

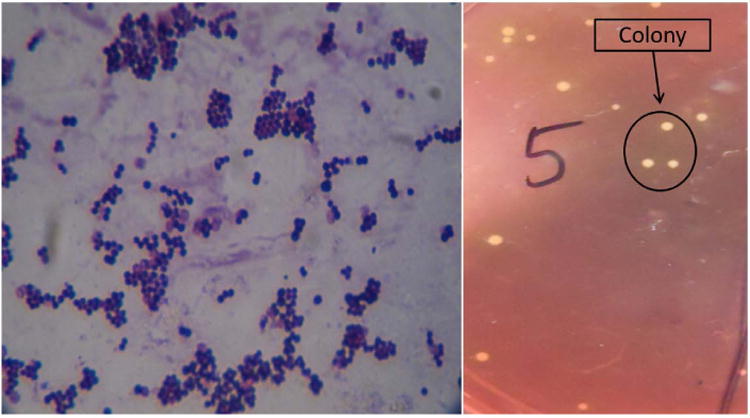

3.3 Microbiological examination

The swab specimens collected from the bone specimens of group I animals after 21 days were streaked on Mannitol 10% salt agar slant and incubated at 37°C for overnight. Observations showed characteristic bacterial growth, sample was collected from a single colony bacterial growth which was stained by Gram's staining method. The organisms were gram (+) coccoid and arranged in single or diploid similar to the organism inoculated (Fig. 4). The swab specimens were also collected from the implanted site of bone in all the groups at day 21 and 42 and inoculated to Mannitol 10% salt agar and incubated at 37°C for overnight. No bacterial growth of Staphylococcus aureus was found except in control group where such growth was seen.

Figure 4.

Photograph showing characteristic morphology of Staphylococcus (left) and characteristic colony of Staphylococcus in Mannitol agar 10% slant after overnight incubation (right).

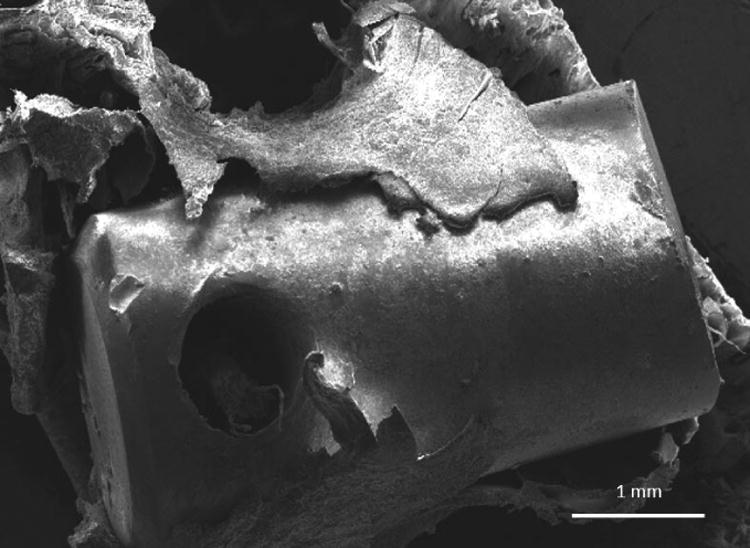

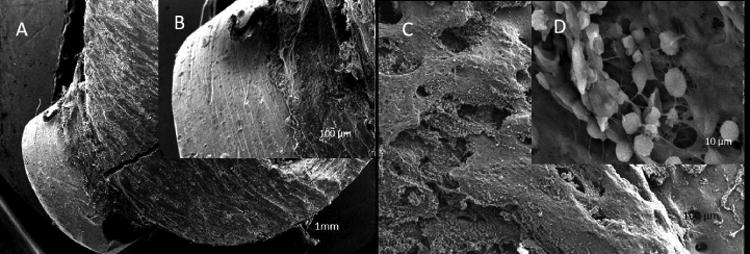

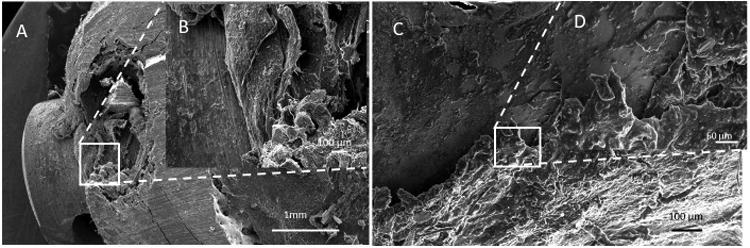

3.4 Scanning electron microscopy of cortical bone

Microstructures of bone defect sites for all the groups of animals are shown in Fig. 5 to Fig 7. Control pin implanted bone sample shows no appreciable bone formation due to presence of infection. There is decalcification of the bony matrix with osteolytic activity and insignificant presence of bridging callus and fibro cartilaginous tissues in Fig. 5. Low dose silver deposited sample after 21 days shows initiation of bone apposition around the surface of pin as observed by newly formed collagen fibrils. Whereas in 42 days, collagen fibril formation vis-à-vis new bone formation is more compared to earlier day i.e., day 21 and shown in Fig. 6. High dose silver deposited pins implanted bone after 21 days shows more bone formation around the pin surface as observed by better communication of collagen fibrils although some interfacial gap is there. At 42 days, there is presence of abundant collagenous tissue around the pin surface along with formation of matured bone and shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 5.

SEM microstructure of bone defect site for control groups of animals taken after 42 days.

Figure 7.

SEM microstructures of bone defect sites for high dose silver coated implants of animals taken after: (A) and (B) 21 days and (C) & (D) 42 days.

Figure 6.

SEM microstructures of bone defect sites for low dose silver coated implants of animals taken after: (A) and (B) 21 days and (C) & (D) 42 days.

3.5 Radiological examinations

Fig. 8 shows radiographs of all three groups at different times. Typical radiographic evidences of osteomyelitis in animals of all groups are presence of severe periosteal reaction in the distal femur with lytic changes and thinning. In some places of distal femur, spongy bone appearance was not clearly visible. Radiodensity of bone marrow appeared to be in excess with mild endosteal reaction in Fig. 8A1. Radiographically control sample at day 21 and 42 shows increased radiodensity along with loss of characteristics of cancellous bone in distal femur and presence of both the phytic and lytic changes. Endosteal reaction was moderate and clearly visible. Interruption of cortical border of distal femur is evident in some places along with secondary osteophytic changes of epiphyseal cartilage, as shown in Fig. 8 C21 and C42. The radiograph on 21 days in low dose silver coated bone sample shows discontinuation of cortex in few places with mild endosteal reaction. Presence of mild radiolucent zones in metaphyseal region of femur is characteristic of osteoclastic changes. At day 42 the radiograph shows absence of periosteal reaction and discontinuation of cortex as observed in earlier days. Restoration of the medullary cavity and remodeling of cortex is prominent although there is presence of few radiolucent zones in epiphysis, as shown in Fig. 8 L21 and L42. In high dose silver deposited pins at day 21 and 42 show lack of periosteal and endosteal reaction, clear medullary cavity along with cortical continuation as observed from the radiographs, shown in Fig. 8 H21 and H42.

Figure 8.

Radiographic pictures of distal femur showing: A1-Development of osteomyelitis after 21 days-The osteophytic and lytic changes are show osteomyelitis.

C21 and C42- control sample at 21 and 42 days showing osteophytic and lytic changes along with discontinuation of cortical border of distal femur.

L21 and L42- Low dose silver coated sample showing discontinuation of cortex in few places with mild endosteal reaction at day 21 and absence of periosteal reaction and discontinuation of cortex at day 42.

H21 and H42- High dose silver coated sample at 21 and 42 days showing recovery from the osteomyelitis changes at the adjacent area of implant.

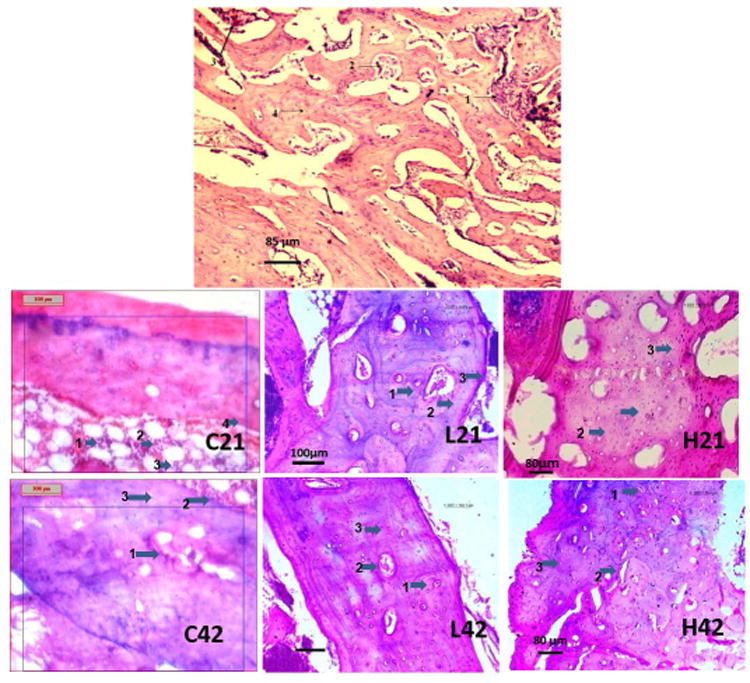

3.6 Histological examination

Fig. 9 shows histological evaluation at the bone-implant interface for all groups. Histological section of femur bone in group I revealed bony degeneration of haversian plates with infiltration of mononuclear cells and few osteoblasts in medullary sinuses. There is evidence of osteoclastic activity in some interstitial spaces and the margin of sinuses is getting worn out in some places. The total phenomena were indicative of osteomyelitis and shown in Fig. 9A1. In control group with no silver coating, osteomyelitic changes are seen at day 21 and 42 characterized by degenerative changes of haemopoigenesis centre, osteophytes, fat cells along with mild fibro vascular proliferation of connective tissues. Bone marrow in the peripheral region showed penetration with mononuclear cells and osteoclasts penetration was observed in the bone marrow peripheral region which is shown in Fig. 9C21 and C42. As shown in Fig. 9L21 with low dose silver coated samples at day 21, presence of haversian canal along with sinusoidal spaces filled with red blood cells (RBC), mononuclear cells and mucin threads. Infiltration of osteoblast along with mononuclear cells is seen at some places. Fibrovascular reaction is seen all throughout the parenchymatous region. At day 42, as shown in Fig. 9L42, section depicted a well-developed vascular stroma of bony plates characterized by newly formed haversian canals tightly all throughout the structure. Osteoblastic and osteoclastic activities are moderate to severe. Fibrosis in sub-cortical area is also evident indicating a good response to healing. Histological sections of high dose silver coating at day 21, Fig. 9H21, shows well defined haversian system along with canalicular structure and formation of osteoclastic foci with infiltration of mononuclear cells. There was mucinious degeneration at the central level of haversian canal. Vascularization at few points was suggestive of angiogenesis which indicated a tendency to repair the parenchymatous mass. Some of the inner lining of canaliculi reveal acellular cystic lining along with void mass in their lumina. Collagen fibers and immature fibroblast run in few places. There is tendency to extravasations of RBC in pericortical zone of Fig. 9H21. At day 42, section shows a multiple number of haversian canals tightened by a delicate bundle of fibrous tissue. Vascular proliferation is prominent particularly to the periphery of canal and inner side of medullary region. Mucin secretion is seen in few places. Proliferation of mononuclear cells is low although the structure is tightly embedded by osteoblast and osteoclast cells. Thickening of vessel wall due to good proliferation of osteoblast cell causes partial compression of sinusoidal places, and shown in Fig. 9H42.

Figure 9.

A1-Histological section of development of osteomyelitis after 21 days (1-Clusters of osteoblast and osteoclast; 2- R.B.C. and mononuclear cell; 3-Medullary cavity; 4-Intraosseous septa)

C21 and C42 – Histology of control sample after 21 and 42 days after development of osteomyelitis (C21- 1-Clumping of R.B.C. and mononuclear cell; 2- mononuclear cell and osteoclast; 3-Fat cells; 4-Blood vessels and fibroblast, C42- 1-Fibroblastic proliferation; 2-Aggregation of mononuclear cell and osteoclast; 3-Degenerative changes in bony lamellae)

L21 and L42 - Histology of bone section of Ag coated low dose implant at 21 and 42 days - (L21 and L42- 1- Haversian canal; 2- Fibrovascular proliferation; 3-mononuclear cell and osteoblast).

H21 and H42 - Histology of bone section of Ag coated high dose implant at 21 and 42 days – (H21- 1- haversian canal; 2-Fibrovascular lamellae; 3- 3-mononuclear cell and osteoblast, H42- 1- Haversian canal; 2-Sinusoidal space; 3-Fibrovascular proliferation)

3.7 Toxicological examination

Toxicological study of silver concentrations in major organs like heart, kidney and liver was carried out at day 42 only. Based on high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) estimation of silver concentration on day 42, it has been measured that the concentration of silver in high dose pin in Heart-BDL (below detection limit), Kidney- 0.53ppb, liver-1.02ppb and in low dose pin Heart- BDL (below detection limit), Kidney-0.41ppb, liver-0.38ppb. All concentrations were below the toxicity levels advised for silver. At the time of sacrifice, the animals were healthy and fit without any undesirable side effects.

4.0 Discussions

Due to lack of treatment options, osteomyelitis patients become disappointed to the therapeutic outcomes. Typically, early antibiotic therapy is the ideal option that must be administered for at least four to six weeks or more to achieve an acceptable rate of cure.5,27 However, if antibiotic therapy fails, adequate debridement, drainage of pus and prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics for another four- to six-week course is needed. 27,28 The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis is more complex and generally requires approaches such as combination of infection control and radical debridement29, fracture stabilization in case of non-union or bone segment excision, antimicrobial therapy, dead space and wound management, and provision of bone graft substitutes especially in the case of large bone defects.30,31 Conventional antimicrobial therapy fails to provide satisfactory results in many cases due to physiological differences in blood supply, local vascularization, and the presence of “blood–bone” barrier.32 The limitations of systemic antibiotic therapy include prolonged treatment due to being unable to create a high local concentration and the consequential risk of toxicity.33-36 Moreover, impaired vascularity of osteomyelitis bone requires the use of higher doses of antibiotics due to poor antibiotic penetration and the difficulty in eradicating organisms when they are in a biofilm phase.36 In spite of standard care, therapeutic failures and reappearances are common, sometimes as high as 30%.36-40

Control of infection on and around SS implants is usually difficult and may lead to ultimate implant migration.41,42 Preventive measures are sought by the researchers to overcome implant-related infection vis-à-vis to give relief to the ailing patient. Various approaches have been attempted to make SS implant surface antibacterial either by impregnation of the surface with antibiotics43 or coating of the surface with silver that may cause sustained release of drugs during application.44-47 We hypothesized that strongly adherent silver nanoparticles on the stainless steel implant will have in situ antibacterial properties as a treatment option for osteomyelitis for an extended period of time in vivo. The antibacterial activity of silver is well established45,46 and mostly relies on the silver cation Ag+, which has a property to bind to electron donor groups of sulphur, oxygen or nitrogen in biological molecules. Generally, oxidation of metallic silver to the active state (Ag+) occurs via an interaction of the silver in aqueous setting.48 Silver has broad spectrum antibacterial properties against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and even in some drug-resistance bacteria at very low concentrations (ppb level).49 Silver coatings have been made in many clinical contexts like heart valves, central venous catheters, urinary catheters and have proved to minimize infection rate towards short term use of medical devices.50,51 However, to the best of our knowledge, scanty in-depth published data available on silver deposited stainless steel implants for the in situ treatment of osteomyelitis.

We developed low and high concentration of silver deposited 316L SS implants and compared with control sample without silver. The minimum requirement of an implant to be bactericidal is steady and continuous release of silver ions at concentration levels of at least 0.1 ppb.52 For ex vivo characterization, only low dose/concentration was used as both the doses resulted in coatings with similar particle range. The silver deposition was carried out using electrodeposition process which is a cost effective method. The electrodeposition resulted in a coating ranging from micro to nano particles. Efforts were taken to ensure the resulting coating contains mostly nanoparticle by cleaning them with DI water. But electro-deposition of silver nanoparticles on SS surface can led to poor adhesion, and required further heat treatment which was performed at 500°C. The cumulative release of silver ions is found to be well below the toxic limit specified for the human tissue. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends no observable adverse effect level (NOAEL) of Silver up to 10 gm for a normal human being.53 The most serious concern for silver toxicity is Argyria, which is not found at or below 1.7 gm total silver in vivo. Researchers have reported that silver intake from the diet can be between 27 and 88 μg/day.11

To test antibacterial properties of silver deposited 316L SS, Staphylococcus aureus, the commonly involved bacteria in development of osteomyelitis was chosen.54,55 Amid the animal trial results, histopathological and microbiological findings are the most important tools for detection of the efficiency of treatment of osteomyelitis and implant-host bone reaction56 Based on the histological analysis, the tendency of alleviating infection as well as intramedullary new bone formation was higher in high dose silver deposited implants followed by low dose implant when compared to control samples. In low dose samples, mild infective changes were noticed at day 21 but subsided gradually with the passage of time at day 42. Whereas high dose sample showed complete eradication of infection at day 21 and 42 with development of multiple number of haversian canals, vascular proliferation and tightly embedding by osteoblast and osteoclast cells with no periosteal reaction in and around the osteomyelitis area. These findings confirm a better efficacy of these implants to resist the injected S. aureus. The silver ions may be released in sufficient concentration from the implants, which combines to membranes, enzymes and to nucleic acid leading to a variety of reversible and irreversible cellular intervention.46,57 Moreover, presence of silver ions may hinder the respiratory chain vis-a-vis the aerobe metabolism of causative microorganisms.58 High dose silver has the capacity to inhibit bacterial adhesion and growth without altering the activity of osteoblasts and epithelial cells.59 In low dose samples, the efficacy of silver ions in treating osteomyelitis in day 21 was less due to low silver concentrations available in the area. This may be due to interference of mode of action of silver ions with the murein of the bacterial cell wall as reported earlier.60 Microbiological examinations was also carried out in each time point. The minimum concentration of 10 to 40ppb of silver ion is necessary to kill the most pathologic microorganisms and 60ppb to eliminate the most resistant strains including methicillin-resistant S. aureus.61 In the present study, it is expected that this minimum concentration was available at the surface of the implants.

Radiological findings of osteomyelitis show presence of severe periosteal reaction with lytic changes, absence of spongy bone appearance with more radiodensity of bone marrow.62 With the passage of time, these findings are completely absent in high dose silver samples both at day 21 and 42; however, in low dose sample, initially there was presence of osteomyelitis signs of mild endosteal reaction along with presence of mild radiolucent zones which subsided gradually at day 42. It has been reported that silver coated prostheses show lower infection rates against Staphylococcus aureus, without any undesirable side effects on the surrounding tissues.47 Silver coated polymer and stainless steel pins also confirmed similar results without any cytotoxicity.4,6 Microstructure of bone-biomaterial interfaces of uncoated implants show no appreciable bone formation due to presence of infection. Low dose samples show less bone apposition around the surface in earlier days that increases gradually with the passage of time. This may be due to presence of residual infection in earlier days. High dose sample shows bone formation around the implant surface as observed by better communication of collagen fibrils both at day 21 and 42, which shows the potentiality of silver ions in eradicating the infection in osteomyelitis site.

Finally, silver concentrations in the vital organs like heart, kidney and liver were within the normal range both in low and high dose silver coated implants. Silver levels below 10 ppb were regarded as normal.63 Toxicological side effects are noticed for silver when blood concentration is more than 300 ppb in the form of argyrosis, leukopenia, liver and kidney damage.64 However, in the present study, silver concentrations were well below the critical concentration, and no such toxicological side effects were observed.

5.0 Conclusions

316L SS implants were coated with silver nanoparticles via electrodeposition for 45 secs (low dose) and 2 min (high dose) in 0.1M silver nitrate solution as an electrolyte. Post deposition heat treatment was done at 500 °C for 7 minutes to increase adhesion of silver nanoparticles on the 316L SS surface per our patented technology. Ex vivo implantation on equine cadaver bone followed by silver release study in DI water and microscopic analysis confirm that no measurable degradation on the surface to dislodge the silver particles during surgical procedure.

Direct ability to treat osteomyelitis using strongly adherent nanoparticulate high and low dose silver deposited nails was studied using a rabbit model followed by bacteriologic, radiographic, histological and scanning electron microscopic study. Silver deposited pins, especially high dose, offered a promising result in terms of eradication of infection in rabbit osteomyelitis model without any toxicity in major organs like heart, kidney and liver at both 21 and 42 day points. Based on our findings, we can conclude that strongly adherent nanoparticles silver on 316L SS surface can effectively treat osteomyelitis. Such findings are especially important because apart from removal of implant or dead tissue management, there are no satisfactory treatment option available at present for osteomyelitis in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

SN would also like to thank Vice Chancellor of West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences for support during the animal research work. Authors would like to thank financial support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR067306-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Samit Kumar Nandi, Department of Veterinary Surgery and Radiology, West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences, India.

Anish Shivaram, W. M. Keck Biomedical Materials Research Laboratory, School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, 99164-2920, USA.

Susmita Bose, W. M. Keck Biomedical Materials Research Laboratory, School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, 99164-2920, USA.

Amit Bandyopadhyay, W. M. Keck Biomedical Materials Research Laboratory, School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, 99164-2920, USA.

References

- 1.Devasconcellos P, Bose S, Beyenal H, Bandyopadhyay A, Zirkle LG. Mater Sci Eng C. 2012;32:1112–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malizos KN, Gougoulias NE, Dailiana ZH, Varitimidis S, Bargiotas KA, Paridis D. Injury. 2010;41:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Megas P, Saridis A, Kouzelis A, Kallivokas A, Mylonas S, Tyllianakis M. Injury. 2010;41:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carek PJ, Dickerson LM, Sack JL. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2413–2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas DW, McAndrew MP. Am J Med. 1996;101:550–561. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:999–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustilo RB. Management of infected fractures. In: Evarts CM, editor. Surgery of the musculoskeletal system. 2. Vol. 5. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. pp. 4429–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaur J, Gulati VL, Aggarwal A, Gupta V. Indian Journal for the Practising Doctor. 2008;4 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prince HN, Prince DL. Orthopedic Design & Technology. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tripton IH, Cook JM. Health Phys. 1963;9:103–145. doi: 10.1097/00004032-196302000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton EI, Minski MJ, Cleary JJ. Sci Total Environ. 1972;1:341–374. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(72)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schierholz J, Lucas L, Rump A, Pulverer G. J Hosp Inf. 1998;40:257–62. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das K, Bose S, Bandyopadhyay A, Karandikar B, Gibbins BL. J Biomed Matl Res Part B. 2008;87:455–460. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokubo T, Kushitani H, Sakka S, Kitsugi T, Yamamuro T. J Biomed Matl Res. 1990;24:721–734. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820240607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohtsuki C, Kokubo T, Neo M, Kotani S, Yamamuro T, Nakamura T, Bando Y. Phosphorus Res Bull. 1991;1:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthew ED, Luckarift HR, Johnson GR. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;1(7):1553–1560. doi: 10.1021/am9002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollini M, Paladini F, Catalano M, Taurino A, Licciulli A, Maffezzoli A, Sannino A. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2011;22(9):2005–2012. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao A, Hang R, Huang X, Zhao L, Zhang X, Wang L, Tang B, Ma S, Chu PK. Biomaterials. 2014;35(13):4223–4235. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy M, Fielding GA, Beyenal H, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4(3):1341–1349. doi: 10.1021/am201610q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fielding GA, Roy M, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Acta biomaterialia. 2012;8(8):3144–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shivaram A, Bose S, Bandyopadhyay A. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;59:508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Materials with modified surface and methods of manufacturing. US Patent 9,440,002

- 23.Brennan SA, et al. Bone Joint J. 2015;97(5):582–589. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B5.33336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kose N, et al. Injury. 2016;47(2):320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin H, et al. Biomaterials. 2014;35(33):9114–9125. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrasser N, et al. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2016;17(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mader JT, Shirtliff ME, Bergquist SC, Calhoun J. Clin Orthop. 1999;360:46–65. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199903000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mader JT, Mohan D, Calhoun J. Drugs. 1997;54:253–64. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetsworth K, Cierny G. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;360:87–96. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199903000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandi SK, Mukherjee P, Roy S, Kundu B, De DK, Basu D. Mater Sci Eng C-Mater Biol Appl. 2009;29:2478–85. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazzarini L, Mader TT, Calhoun JH. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(10):2305–2318. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200410000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walenkamp GH, Vree TB, van Rens TJ. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;205:171–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naraharisetti PK, Lew MDN, Fu YC, Lee DJ, Wang CH. J Control Release. 2005;102:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billon A, Chabaud L, Gouyette A, Bouler JM, Merle C. J Microencapsul. 2005;22:841–52. doi: 10.1080/02652040500162790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu QG, Czemuszka JI. J Control Release. 2008;127:146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Husseini M, Patel S, MacFarlane RJ, Haddad FS. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:151–157. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B2.24933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnieders J, Gbureck U, Thull R, Kissel T. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4239–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanellakopoulou K, Thivaios GC, Kolia M, Dontas I, Nakopoulou L, Dounis E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Andreopoulos A, Karagiannakos P, Giamarellou H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2335–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01360-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, Embil JM, Joseph WS, Karchmer AW, Lefrock JL, Lew DP, Mader JT, Norden C, Tan JS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. 2004;39:885–910. doi: 10.1086/424846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tice AD, Hoaglund PA, Shoultz DA. Am J Med. 2003;114:723–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Respet PJ, Kleinman PG, Meinhard BP. J of Ortho Research. 1987;5:600–603. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhattacharyyra M, Bradley H. Wounds. 2006;2:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parvizi J, Wickstrom E, Zeiger AR, Adams CS, Shapiro IM, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Hickok NJ. Clin Orth Rel Res. 2004;429:33–38. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150116.65231.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Böswald M, Lugauer S, Regenfus A, Greil J, Guggenbichler JP. Infection. 1999;27:24–29. doi: 10.1007/BF02561614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson ME, Harmon BG, Kollef MH. CHEST Journal. 2002;121:863–870. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brutel de la Riviere A, Dossche KM, Birnbaum DE, Hacker R. J Heart Valve Dis. 2000;9:123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bosetti M, Massè A, Tobin E, Cannas M. Biomaterials. 2002;23:887–892. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melaiye AYW. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2005;15:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook G, Costerton JW, Darouiche RO. Int J Antimicr Agents. 2000;13:169–173. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davenport K, Keeley FX. J Hosp Infect. 2005;60:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar R, Munstedt H. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2081–2088. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kundu B, Nandi SK, Roy S, Dandapat N, Soundrapandian C, Datta S, Mukherjee P, Mandal TK, Dasgupta S, Basu D. Ceram Int. 2012;38:1533–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kundu B, Soundrapandian C, Nandi SK, Mukherjee P, Dandapat N, Roy S, Datta BK, Mandal TK, Basu D, Bhattacharya RN. Pharm Res. 2010;27:1659–1676. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joosten U, Joist A, Frebel T, Brandt B, Diederichs S, Von Eiff C. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hollinger MA. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26:255–260. doi: 10.3109/10408449609012524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bragg PD, Rainnie DJ. Can J Microbiol. 1974;20:883–889. doi: 10.1139/m74-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen W, Liu Y, Courtney HS, Bettenga M, Agrawal CM, Bumgardner JD, Ong JL. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5512–5517. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Modak K, Fox C. Biochem Pharm. 1973;22:2392–2404. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burrell RE. Silver release in simulated wound fluids from silver containing dressings; 2nd Meeting of World Wound Healing Societies; Paris. 2004. Abs Z.042. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nandi SK, Kundu B, Mandal TK, De DK, Basu D. Ceram Int. 2009;35:1367–1376. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gosheger G, Hardes J, Ahrens H, Streitburger A, Buerger H, Erren M, Gunsel A, Kemper FH, Winkelmann W, von Eiff C. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5547–5556. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greil J, Spies T, Böswald M, Lugauer S, Regenfus A, Guggenbichler JP. Infection. 1999;27:34–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02561615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chambers C, Proctor C, Kabler P. J Am Water Works Association. 1962;54:208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 64.World Health Organisation. Silver in drinking water: Background document for the development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 1996. WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/14. [Google Scholar]