Abstract

Hair loss is a common medical problem. In this study, we investigated the proliferation, migration, and growth factor expression of human dermal papilla (DP) cells in the presence or absence of treatment with mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs). In addition, we tested the efficacy of MSC-EV treatment on hair growth in an animal model. MSC-EV treatment increased DP cell proliferation and migration, and elevated the levels of Bcl-2, phosphorylated Akt and ERK. In addition; DP cells treated with MSC-EVs displayed increased expression and secretion of VEGF and IGF-1. Intradermal injection of MSC-EVs into C57BL/6 mice promoted the conversion from telogen to anagen and increased expression of wnt3a, wnt5a and versican was demonstrated. The first time our results suggest that MSC-EVs have a potential to activate DP cells, prolonged survival, induce growth factor activation in vitro, and promotes hair growth in vivo.

Introduction

Hair loss (alopecia) is a very common medical problem affecting both males and females, which can have negative psychological impacts on affected individuals. There are many potential causative factors, including nutritional deficiencies, hormonal changes, treatment with a variety of medications, and surgery1,2. Hair follicles are epidermal appendages that contain both epithelial and mesenchymal compartments; the dermal papilla (DP) is located at the base of hair follicle and is thought to be fundamental for hair follicle morphogenesis and cycling3. The hair follicles cycle through various stages in hair growth with active hair growth occurring during the anagen phase4. The hair growth cycle involves three different stages anagen, catagen and telogen. Anagen involves the rapid proliferation of follicular epithelial cells known as matrix cells in the hair bulb which then differentiate to make the hair fiber and follicular root sheath cells. Bulb matrix cells are under the control of specialized mesenchymal cells in the dermal papilla. Catagen involves apoptosis leading to regression of the lower two thirds of the follicle, preserving the stem cell region and telogen is a relatively inactive period between the growth phases5. Currently, many cosmetic products and dermatological medicines are available or being developed to overcome hair loss6, including oral and topical medicines, as well as surgical management. However, drug treatment (finasteride, minoxidil) provides only short-term improvement, and discontinuing treatment may result in rapid hair loss7,8. Autologous single follicle and follicular unit transplantation is a reliable surgical option, but the number of donor follicles is limited. Therefore, novel strategies with long term efficacy are needed for hair loss treatment9.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membranous nanovesicles (30–1000 nm in diameter) that are released by most cell types into the extracellular space in body fluids and cell culture media10. EVs are composed of exosomes and microvesicles. Exosomes form intracellularly through inward budding of the limiting membrane of endocytic compartments, forming vesicle-containing endosomes called multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs). MVBs eventually fuse with the plasma membrane, thus releasing their internal vesicles; microvesicles are outward budding, which directly release into extracellular medium. EVs act as natural nano-sized membrane particles, containing proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids10,11. Studies have shown that exosomes play a critical role in cell–cell communication. Recently, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been extensively investigated in the area of regenerative medicine, and the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived EVs has attracted attention in various medical fields11,12. MSC-EVs have been shown to have anti-cancer effects11, and can promote angiogenesis, improving recovery from ischemic diseases13 and brain injury14. However, the effects of MSC-EVs on DP cell activation and hair regrowth is unknown. In this study, we are first to investigate the effects of EVs from the supernatant of cultured MSCs on DP cell activation and promotion of hair follicle conversion from telogen to anagen in mice.

Results

Characterization of MSC-EVs

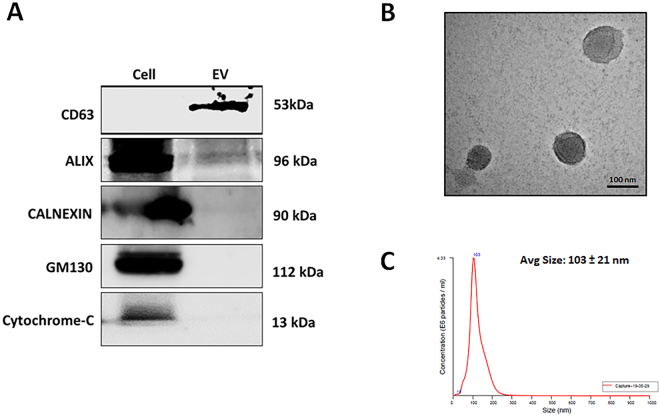

To examine the purity of the extracted MSC-EVs, we probed for several well-characterized positive and negative protein markers of EVs, using western blot analysis15. As expected, CD63 (a membrane bound protein) and ALIX (a cytoplasmic protein) were detected in the EV fraction, but not in the cellular fraction. Conversely, GM130, cytochrome c, and calnexin (markers of the Golgi, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum, respectively) were present in the cellular fraction and not in the EVs, indicating that the EVs were not contaminated with cells or apoptotic bodies (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, TEM revealed the presence of round EVs, as well as the presence of EV membrane. By nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), the diameter of the MSC-EVs ranged from 30–250 nm, with an average diameter of 103 ± 21 nm (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these observations indicate that MSCs release membrane vesicles with features of EVs, which were successfully isolated and characterized.

Figure 1.

Characterization of MSC-EVs. (A) Western blot analysis of cell compartment markers in MSCs (Cell) and MSC-EVs (EV). (B) Transmission electron microscopy images of MSC-EVs (scale bar, 100 nm). (C) MSC-EV size distribution as determined by NTA.

Cellular uptake of MSC-EVs into DP cells

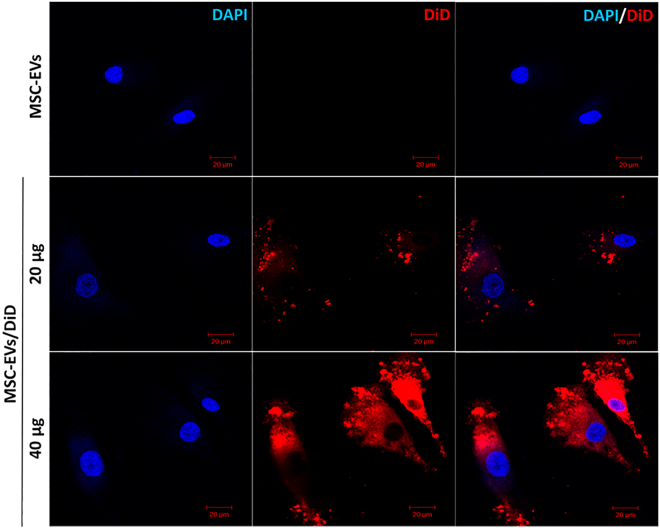

To analyze the uptake of MSC-EVs into DP cells, the MSC-EVs were labeled with the fluorescent dye DiD, and the MSC-EVs/DiD were incubated with DP cells for 4 h. MSC-EV uptake by DP cells increased in a dose-dependent manner, as visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). Our results suggest that MSC-EVs can be efficiently internalized into DP cells.

Figure 2.

Uptake of MSC-EVs by DP cells. Confocal images of DP cells incubated with either PBS, unlabeled MSC-EVs (MSC-EVs), or 20 or 40 μg of DiD-labeled MSC-EVs (MSC-EV-DiD). Scale bar, 20 μm.

MSC-EV treatment increases DP cell proliferation, survival, migration, and activates the Akt/ERK pathways

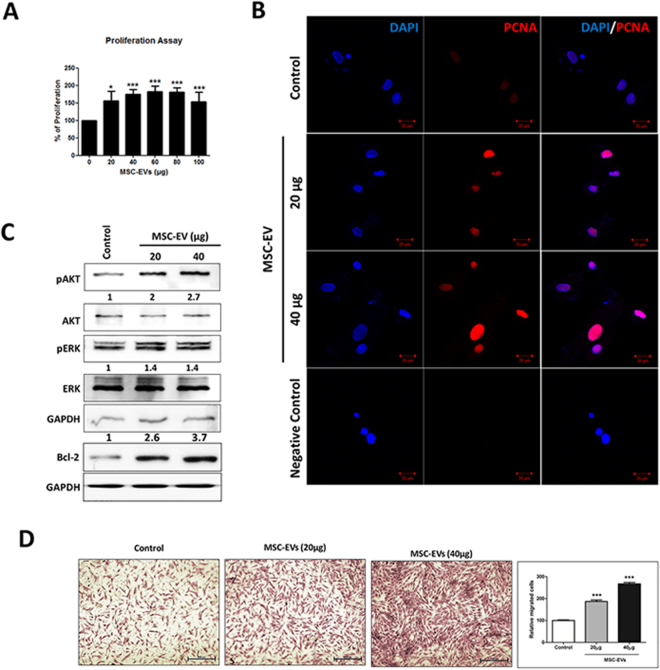

DP cells play an important role in regulating hair growth; therefore, we determined the effects of MSC-EVs on DP cell proliferation and migration. After incubation with every concentration of MSC-EVs, DP cell proliferation increased significantly. At 20 µg MSC-EVs, proliferation increased 1.5-fold (p < 0.05), and highly significant changes (p < 0.001) were observed at 40 to 100 µg compared to the untreated control (Fig. 3A). To confirm the increase in proliferation, DP cells were immunostained for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; a proliferative marker) after treatment with MSC-EVs. Immunofluorescence results confirmed that PCNA was increased in DP cells treated with MSC-EVs compared to untreated control cells (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that MSC-EVs induce DP cell proliferation.

Figure 3.

Effects of MSC-EVs on DP cell proliferation and migration. (A) Histogram showing cell proliferation as determined by a CCK8 assay, 24 h after treatment with 0–100 µg MSC-EVs. The mean and SD of triplicate experiments are plotted. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. (B) Fluorescent images of DP cells immunostained for PCNA 24 h after either no treatment or treatment with 20 or 40 µg MSC-EVs (scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Western blot analysis of Akt, ERK, Bcl-2 and GAPDH levels in DP cell lysates 24 h after either no treatment or treatment with 20 or 40 µg MSC-EVs. (D) Representative images of migrated cells (scale, 500 pixels) are shown, as well as a quantified bar diagram of migrated cells. The mean and SD of triplicate experiments are shown. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Student t-test was used.

We also examined whether MSC-EV treatment modulates DP cell signaling pathways using western blot analysis. We observed significant increases in both Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in MSC-EV-treated DP cells compared to control cells (Fig. 3C). To investigate the probable association between MSC-EV induced human DP cell proliferation and prolonged DP cell survival, the levels of the anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) was determined in DP Cells after the treatment. The western blot analysis showed that the expression of Bcl-2 increased in response to MSC-EV treatment. To determine if MSC-EV treatment affected DP cell migration, trans-well migration assays were performed. MSC-EV treatment caused a 3-fold increase in DP cell migration rate (p > 0.001 at both 20 and 40 µg) compared to the control (Fig. 3D). These data together suggest that MSC-EVs induce DP cell migration. The increased phosphorylation of Akt, ERK and Bcl-2 is consistent with the increased cell proliferation, migration and survival after MSC-EV treatment.

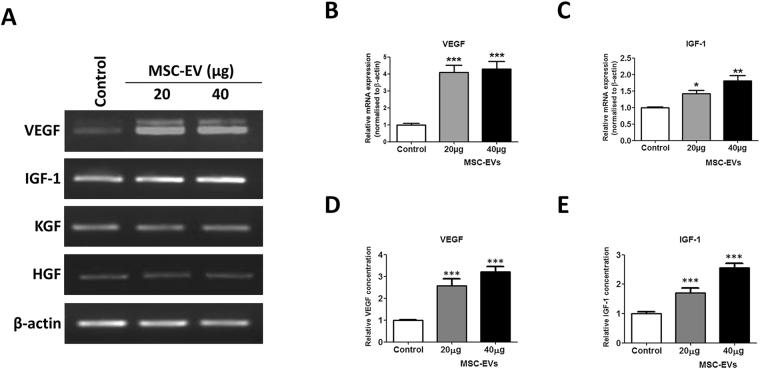

MSC-EV treatment activates DP cell growth factor expression and release

Numerous studies have implicated DP-derived growth factors and cytokines in the regulation of hair growth16. Therefore, we investigated the mRNA expression of VEGF, IGF-1, KGF, and HGF in DP cells after MSC-EV treatment. While KGF and HGF levels did not change after MSC-EV treatment, VEGF and IGF-1 both increased in expression (Fig. 4A). VEGF mRNA expression increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.001 at both 20 and 40 µg) compared to the untreated control (Fig. 4B). Similarly, IGF-1 mRNA expression was also significantly increased (p < 0.05 with 20 µg, p < 0.01 with 40 µg) compared to the control (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, ELISA results demonstrated that the increased VEGF and IGF-1 were released into the cell culture supernatant at significantly higher levels than from the untreated controls (p < 0.001 at both 20 and 40 µg; Fig. 4D,E). Taken together, these data suggest that MSC-EV treatment increases the expression and release of growth factors by DP cells. We examined weather MSC-EV have growth factor proteins/mRNAs. Our RT-PCR results showed MSC cells expresses VEGF and no expression of IGF-1, whereas MSC-EV does not contain any of the mRNAs in its compartment. Furthermore, western blot results revealed that VEGF protein is enriched in MSC-EV compare to MSC cells. (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of MSC-EVs on growth factor expression in DP cells. (A) Cultured DP cells were treated with MSC-EVs for 24 h, and gene expression was examined by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (B,C) The relative levels of VEGF and IGF-1 mRNA were quantitated from three independent experiments each. (D,E) VEGF and IGF-1 concentrations in conditioned media after 24 h of MSC-EV treatment were measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Student t-test was used.

Determination of MSC-EV treatment intervals in C57BL/6 mice

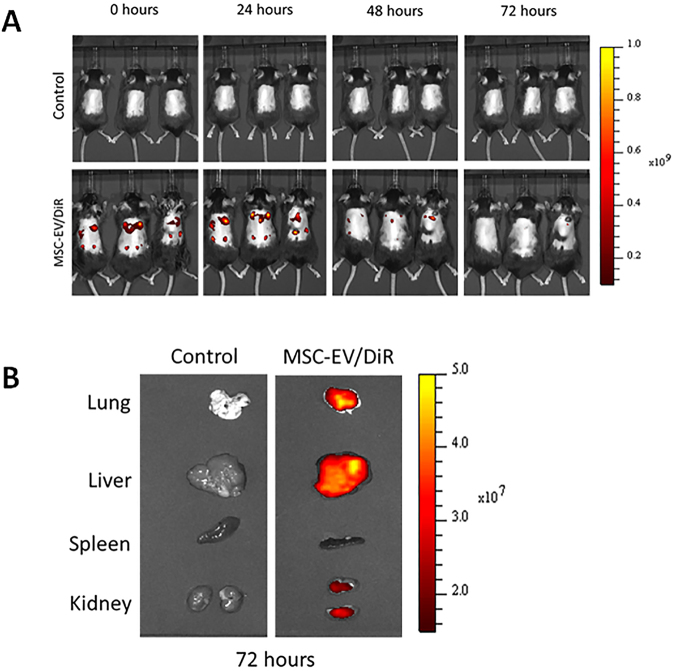

We examined MSC-EV retention in mice using DiD-labeled MSC-EVs (MSC-EVs/DiD) and in vivo fluorescence imaging. Mice whose dorsal hair had been removed with an electric shaver were injected Intradermally with MSC-EVs/DiD under the dorsal skin in multiple regions, then imaged at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. At 0 and 24 h, strong fluorescent signals were observed in the dorsal sides of mice. The signals were reduced after 48 h, and almost undetectable at 72 h. This suggests that the MSC-EVs were retained in the mice dorsal skin up to 48 h and were cleared or internalized by surrounding cells after 72 h (Fig. 5A). In addition, we examined whether injected MSC-EVs were distributed to major organs (lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys) using ex vivo organ fluorescent imaging 72 h after MSC-EVs/DiD injection, and observed MSC-EVs in the lungs, liver, and kidneys (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Determination of MSC-EV treatment intervals in C57BL/6 mice. (A) Time-based in vivo fluorescent imaging of MSC-EVs/DiD in C57BL/6 mice. MSC-EVs/DiD or PBS (control) was administered intradermally 2 d after hair was clipped. (B) Representative in vivo fluorescent imaging of dissected organs from mice injected with MSC-EVs/DiD or PBS (control). Mice were euthanized 72 h after injection.

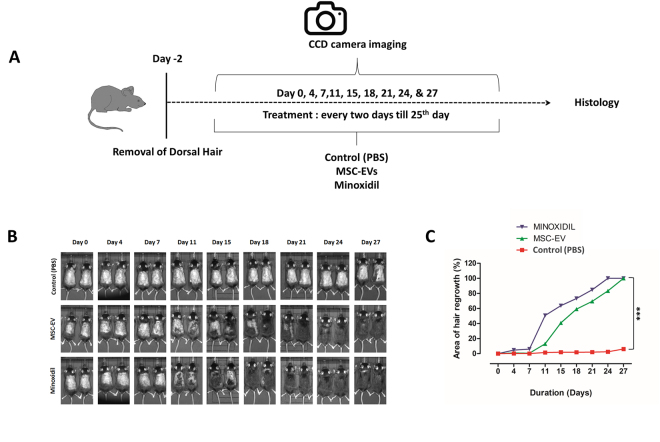

Hair regeneration effects of MSC-EVs in C57BL/6 mice

To determine whether MSC-EVs could induce hair regrowth in mice, we examined the effect of MSC-EV treatment in C57BL/6 mice, since the dorsal hair in these mice has a time-synchronized growth cycle5. We clipped the dorsal hair of C57BL/6 mice two days before treatment. We compared the in vivo hair regrowth results of MSC-EV treatment with 3% minoxidil, which is considered the current gold standard for hair regrowth treatment, as well as an untreated control group (Fig. 6A). Usually, the shaved skin of C57BL/6 mice is pink during the telogen phase, and darkens with anagen initiation17. As shown in Fig. 6B, by 11 d, both the MSC-EV and minoxidil treatments resulted in diffuse darkening of the dorsal skin, indicating that hair follicles were in the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle. The untreated control group displayed no significant changes. By day 18, the MSC-EV and minoxidil groups displayed more than 60% hair regrowth, and after 27 d, the dorsal hair of mice in the MSC-EV and minoxidil groups had fully regrown, while in control mice, only faint regrowth was observed (Fig. 6B). Overall, these findings indicate that MSC-EVs, like minoxidil, can induce earlier conversion of the hair cycle and stimulate hair growth in a murine model. The quantified results revealed that MSC-EVs and minoxidil groups showed significantly increase (p > 0.05) in the hair growth from day 11 and higher significant increase (p > 0.001) was measured at day 27.

Figure 6.

MSC-EVs induce the anagen stage in C57BL/6 mice. (A) After shaving, the dorsal skin was treated with MSC-EVs (n = 6), PBS (negative control, n = 5), or 3% minoxidil (positive control, n = 6) every 2 d for 28 d. (B) The dorsal skin was photographed at 0, 4, 11, 15, 18, 21, 24, and 28 days. (C) Quantification of area of hair regrowth quantified by imageJ software, values are represented in percentage. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001. Student t-test was used.

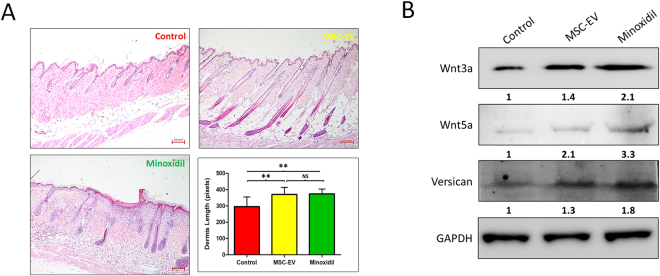

Histological findings

The effect of MSC-EVs on hair regrowth was assessed by H&E staining. Sections of the dorsal skins after 27 d demonstrated that the application of MSC-EVs significantly promote conversion from telogen to anagen compared to the control group, at equal levels to those observed in the minoxidil group, (Fig. 7A) suggesting that MSC-EVs promote hair regrowth by promoting conversion from telogen to anagen of hair follicles. MSC-EV and minoxidil treatments significantly increased thickness of dermis (p > 0.01) compared to control group, and there was no significant difference of the thickness (P = 0.443) between MSC-EV and minoxidil treatments. When the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys from all groups were examined by H&E staining, no significant differences were seen between any of the groups (Supplementary Figure 2), indicating that repeated MSC-EV injection was not toxic to these organs.

Figure 7.

MSC-EVs promotes the conversion from telogen to anagen in C57BL/6 mice. After clipping of hair, MSC-EVs, PBS (negative control), or 3% minoxidil (positive control) was administered to the dorsal skin every 2 days for 28 days, followed by H&E staining; (A) Sections of the dorsal skin. Sections were examined under and imaged under upright digital microscope (Nikon) (scale bar: 100 pixels). Graph represents thickness of dermis of the visible microscopic field (5 fields) with at-least 5 measurements was taken using ZEN lite microscopic software (ZEN lite 2.3- Carl Zeiss, Germany) in all 3 groups, values are represented in pixels. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01. Student t-test was used. (B) Western blot analysis of the expression of the indicated proteins (50 µg) in dorsal skin of C57BL/6 mice treated with PBS (control), MSC-EV and Minoxidil. Wnt3a, Wnt5a, Versican, and GAPDH were used as internal loading controls.

MSC-EV treatment leads to increase Wnt signaling and Versican expression in C57BL/6 mice dorsal skin

Hair follicle morphogenesis depends on Wnt, Shh, Notch, BMP and other signaling pathways interplay between epithelial and mesenchymal cells. The Wnt pathway plays an essential role during hair follicle induction18. We examined whether MSC-EV treatment modulates Wnt signaling pathways using western blot analysis. MSC-EV treatment lead to significant increased expression of Wnt3a (1.4 fold) and Wnt5a (2.1 fold) when compare to control. Minoxidil treatment showed slightly higher expressions of these proteins compared to MSC-EV treatment. Previous studies suggest versican expression plays an essential role in hair follicle formation and its function is dose-dependent to some degree19. Our western blot results showed substantial increase of versican expression in MSC-EV and minoxidil treatment mice compared to control mice (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

Cell-cell communication is required for various physiological and pathological processes. Numerous studies suggest that, apart from releasing soluble factors, cells can communicate both nearby and at a distance through EVs20,21, which can directly transfer various biological molecules including mRNAs, microRNAs, and proteins from donor cells to recipients22–24. Stem cell transplantation has great potential to treat diseases and MSCs have been widely explored for use in regenerative therapies25. In the stem cell therapeutics field, adult MSCs have been extensively studied due to their high self-renewal capacity, differentiation capacity, and low immunogenicity26,27. Among multi-potent MSCs, those derived from bone marrow have recently emerged as an attractive cell type for the treatment of various diseases28–30. Similarly, MSC-EVs have produced encouraging outcomes on a wide range of diseases12, with results demonstrating that they can modulate immune responses31, reduce the size of myocardial infarctions32, facilitate the repair of traumatic brain injury14, and stimulate angiogenesis and blood vessel regeneration13.

Hair regeneration is controlled by the DP cells, which manage hair follicle cycling through secreted signaling factors9. Generally, human hair follicles affected by androgenetic alopecia contain a largely intact population of hair follicle stem cells and are mainly deficient in DP signaling, resulting in an inability to stimulate the beginning of the hair cycle33. The restoration of DP cell hair induction ability, therefore, is a promising potential therapy for hair loss. However, to date, the application of bone marrow-derived MSC-EVs to activate DP cells for in vitro and in vivo hair regeneration has not been reported.

In this study, we have successfully isolated EVs from MSC cell culture media, which are consistent with the reported size and shape of EVs in previous studies11,15,34. EVs expressed the EV-specific surface markers ALIX and CD63, and cell compartment markers like GM130, cytochrome c and calnexin were not detected in EVs, confirming the isolation of pure EVs without contamination with cell organelles and apoptotic bodies11,35. EV interaction and uptake, which is necessary for the delivery of biomaterials to recipient cells, involves direct fusion to the plasma membrane via ligand-receptor interactions or lipids such as phosphatidylserine36, followed by release of EV contents into the cytoplasm. Using fluorescently labeled MSC-EVs, we confirmed that MSC-EV uptake into DP cells occurred readily, within 4 h of treatment, in a dose-dependent manner11,37.

DP cell proliferation is necessary for the morphogenesis and growth of the hair follicle. MSC-EVs were found to induce significant proliferation of DP cells, at rates as robust as those reported for minoxidil38. Akt plays a critical role in mediating survival signals39,40 and Whether a cell should live or die is largely determined by the Bcl-2 an anti-apoptotic regulator38,41. Our results suggest that MSC-EVs lead to activation of Akt phosphorylation and increased Bcl-2 in DP cells. Taken together, activation of Akt and increase in Bcl-2, by MSC-EVs might prolong the survival of DP cells. The Akt pathway may also be involved in regulating DP cell proliferation. During the initial stage of hair follicle morphogenesis, DP cells self-aggregate in the dermis, where they play a vital role in guiding the epidermal placode to develop into follicular structures42,43, Young et al. showed that microtissues are formed through the active migration and self-aggregation of DP cells44. We also investigated the effect of MSC-EVs on DP cells migration using trans-well assays, and showed that MSC-EV treatment significantly enhanced DP cell migration. Rapid division of DP cells by MSC-EV treatment may have partially contributed to the enhanced migration, however, previous studies suggested that cells stop proliferation when the cells are going to migrate45 and a low proliferation rate in the migrating cells of human cancer cell has been reported as well46.

DP cells are capable of releasing growth factors that direct epithelial cells to proliferate, leading to hair shaft growth and acceleration of hair regeneration47,48. Our results revealed that VEGF and IGF-1 gene expression and release were significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner by MSC-EV treatment. Several studies have shown that VEGF can promote hair growth, enlarge follicle size, and increase hair thickness47,49. In the skin, IGF-1 is expressed by cells of the dermis and the DP of hair follicles50, and hair growth from human follicles can be achieved by stimulating IGF-1 induction in DP cells. Therefore, the induced secretion of VEGF and IGF-1 from DP cells after MSC-EVs treatment may play a positive role in promoting the growth of hair follicles. Although the HGF mediated signaling has been noted to promote cell migration51–53, however, MSC-EV treatment increased migration of DP cells but there was lack of HGF expression, which shows that migration of DP cells here is not depend on HGF expression.

In this study, the MSC-EV distributed to major internal organs, which is not unusual since EVs are nano size membrane vesicles which is easy reaches systemic circulation. Other studies showed distribution of EVs to major organs such as lung, liver, spleen and kidney via different routes of injection (Intravenous, intraperitoneal and intramuscular)10,54, but we used intradermal injection which has not been reported yet to our knowledge.

In this study, we combined mouse MSC-EVs to human DP cells, previous study reported that mouse cell EVs could be transferred to human cells (mast cells), and the transferred mouse exosomal RNAs could translate and synthesize new mouse proteins in these human recipient cells55. Another study proved that exosomes released by cows in the milk could be taken up by human being56. However there is still lack of intensive studies on transfer of exosomes between different species. Further studies are needed to uncover mechanisms of the interaction among different species. We hypothesis that EV from human MSCs may possess a same hair growth promoting effects on human DP cells because other separate studies using mouse or human MSC-EV showed a tumor inhibiting effect on breast cancer cells57,58. Furthermore, the mouse or human MSC-EV demonstrated a ischemic recovery effect in ischemic mouse models32,59.

Using C57BL/6 mice to evaluate the in vivo effects of MSC-EVs on induction of the anagen phase, we demonstrated that MSC-EV treatment induced hair regrowth comparably to minoxidil, the current gold standard. Minoxidil treatment can cause irritation and allergic contact dermatitis on the scalp60. In addition, measurable hair growth disappeared within months after discontinuation of minoxidil treatment61. Long-term effects of MSC-EV treatment on hair regeneration remain to be investigated. Consistently, MSC-EV treatment significantly promoted telogen to anagen conversion, comparably to the minoxidil group. Thickness of dermis was also increased which indirectly reflecting enhancement of hair growth by MSC-EV treatment. Furthermore, no damage to the major organs was observed, indicating that MSC-EV might be a non-toxic treatment option.

Wnt signaling is involves in the maintenance of hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) through their entire life-cycle, including during resting (telogen) phase of the growth cycle62,63. Our results suggested that MSC-EV treatment leads to increased Wnt3a and Wnt5a, so the treatment might be helpful for activating human hair follicle stem cell resulting in anagen onset. Previous studies showed that Wnt signaling is active in the hair follicle during both embryonic hair morphogenesis and anagen phase64,65. Furthermore, treatment with MSC-EV showed higher expression of versican than in control. Other studies clearly showed specific and higher versican expression in the DP cells of anagen phase, which apparently decreased in DP cells of catagen phase66,67, which admits that MSC-EV treatment leads to transformation of DP cells into anagen phase. Many signaling pathways involved in telogen to anagen transition, which includes estrogen receptor pathway68, BMP signaling69, mTOR signaling70, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathways71, so further future investigations are warranted for better understanding of MSC-EV effects on hair regrowth.

Future perspectives: For patients with hair loss, EV derived from autologous MSCs may be one of excellent candidates for stimulating hair regrowth in human subjects. Several critical issues should be investigated before clinical use of the MSC-EV for management of hair loss, including the best cell type for EV isolation, the optimal concentration and administrating route (intradermal or topical) of the EV, and initiation timing, frequency and duration of the EV treatment

Overall, in vitro experiments demonstrated that MSC-EVs induce proliferation and migration to accelerate the hair induction ability of follicular DP cells. Further experiments revealed that MSC-EV promotes hair growth through stimulation of VEGF and IGF-1 in DP cells. In vivo results revealed that MSC-EVs accelerate the biological progression of hair regeneration and transforms hair follicles from telogen to anagen phase. These results suggest that MSC-EVs can induce hair regrowth by actively facilitating the induction ability of DP cells in mice. Thus, our findings suggest that, if reproducible in humans, MSC-EV treatment could be clinically exploited as a powerful anagen inducer and could represent a promising strategy for the treatment of hair loss.

Methods

MSC cell culture

Mouse bone marrow-derived MSCs (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were cultured in DMEM-F12 (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% EV-depleted fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) (18 h at 120,000 g at 4 °C) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Primary culture of DP cells

The medical ethics committee of Kyungpook National University and Hospital (Daegu, Republic of Korea) approved the use of samples from patients undergoing hair transplantation surgery, and the study followed the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from all patients, and hair follicles were isolated and cultured as described72. DP cells were isolated from the bulbs of dissected hair follicles, transferred to tissue culture dishes coated with bovine type I collagen, and cultured in DMEM (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 1 × Antibiotic-Antimycotic, 1 ng/mL bovine fibroblast growth factor, and 20% heat inactivated FBS at 37 °C. The explants were cultured for 7 d, and the medium was changed every 3 d. Once cultures reached near-confluence, the cells were harvested with 0.25% trypsin, and sub-cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. In this study, cells were used up to passage 372.

Isolation and purification of EVs from MSCs

MSC cells were cultured as described above, and EVs were isolated as previously described15. Briefly, the supernatant was centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, at 1,500 g for 20 min, and finally at 2,500 g for 20 min, to remove cells and debris. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filter, and ultra-centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min. Pellets were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and ultra-centrifuged again. The final pellet was resuspended in 50–100 µL PBS and stored at −80 °C. All ultra-centrifugation steps were performed at 4 °C using an SW28 rotor and Ultra-Clear tubes in an Optima L-100XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described73. Whole-cell or EV or dorsal skin tissue lysates were prepared in SDS lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, USA). Equal amounts of protein were loaded and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), probed first with the primary antibody, and then with the secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The antibodies used are listed in Table S1.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The EV pellets were resuspended in 100 µL of 2% paraformaldehyde, and 5 µL was added to Formvar/Carbon TEM grids, then covered with absorbent membranes for 20 min in a dry environment. Grids were washed with 100 µL PBS, and then incubated in 50 µL 1% glutaraldehyde for 5 min. The grids were then washed 7 times with distilled water for 2 min and observed on HT 7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan)) to view the size of the EVs15.

Nano-particle tracking analysis (NTA)

MSC-EV size and concentration measurements were performed by nanoparticle tracking analysis using a NanoSight LM10 (Malvern Instruments), equipped with a sample chamber with a 640 nm laser and a Viton fluoroelastomer O-ring. EVs resuspended in PBS were diluted 500-fold in Milli-Q water. The samples were injected into the sample chamber with sterile syringes. All measurements were performed at room temperature, and three measurements of each sample were performed. The particle size values were obtained by the NTA software correspond to the arithmetic values calculated with the sizes of all the particles analyzed by the software.

EV labeling and uptake assay

EVs were incubated with Vybrant DiD Cell-Labeling Solution (Molecular Probes) for 20 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and then ultra-centrifuged as above. The DiD-labeled EVs (20 and 40 µg) were incubated with human DP cells for 4 h at 37 °C before fixation with methanol. Coverslips were mounted using anti-quenching agent (VECTASHIELD, Burlingame, CA, USA) and sealed. Cellular internalization of EVs was observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 780, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

In vitro proliferation assay

DP cells (5,000 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with MSC-EVs for 24 h at 37 °C. Proliferation was measured using the CCK-8 Kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunofluorescence

Human DP cells grown on cover slips for 24 h with or without MSC-EVs (20 and 40 µg) were treated with 0.03% Triton X-100 in chilled methanol for 90 sec. Permeabilized cells were then further fixed in chilled methanol for 10 min at −20 °C. Immunostaining was performed as previously described73. Confocal images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 780 microscope.

In vitro migration assay

Assays were performed in 24-well cell culture inserts with an 8.0-µm pore size transparent PET membrane (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Human DP Cells (5 × 104) were plated in each upper insert in 0.5 mL of serum-free medium with 20 or 40 µg MSC-EVs. DP cells treated with no MSC-EVs served as a control. Medium supplemented with 10% FBS was placed in the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 24 h, cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and counted as previously described74.

Isolation of RNA and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was isolated with the TRI reagent and cDNA was prepared using high capacity cDNA Synthesis Kit (ABI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR were performed as previously described75, using the primers listed in Table S2.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

VEGF and IGF-1 ELISAs were performed using kits (R&D Systems) using the manufacturer’s supplied protocols. The experiments were performed in titer plates coated with VEGF or IGF-1 antibodies. Cultured conditioned media (200 or 50 µL for VEGF and IGF-1, respectively) was added and incubated at either room temperature (for VEGF) or 4 °C (for IGF-1) for 2 h. After washing, the plates were incubated with VEGF or IGF-1 conjugates for 2 h at room temperature or 4 °C, respectively. Substrate solution (200 µL) was added, and after 20 min incubation at room temperature, 50 µL of stop solution was added and the optical density was measured at 450 nm.

In vivo experiments

All described procedures were reviewed and approved by the Kyungpook National University (KNU-2012-43) Animal Care and Use Committee, and performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male 5.5-week C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Hamamatsu (Shizuoka). Two d before the experiment, hair was clipped from the dorsal surface of each mouse with an electric shaver under anesthesia, without causing damage or injury to the skin76. To determine the optimal time interval between doses of MSC-EVs, we assayed MSC-EV retention in mice (n = 3) with DiD-labeled MSC-EVs (MSC-EVs/DiD) by fluorescence imaging on an IVIS Lumina III In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer). The animals were divided into control (PBS; n = 5), treatment (200 µg MSC-EVs; n = 6), and positive control (3% Minoxidil; n = 6) groups. Animals were intradermally injected with either 200 µL PBS or 200 µg MSC-EVs in 200 µL PBS. Minoxidil (200 µL) was applied to the dorsal skin twice in a week. Mice were imaged immediately following treatment and Quantification of hair growth was performed using ImageJ.

Histological assessments

Animals were euthanized at the end of experiment and the dorsal skins were harvested. Major organs were also harvested and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as previously described73. Thickness of dermis of the visible microscopic field (5 fields) with at-least 5 measurements was taken using ZEN lite microscopic software (ZEN lite 2.3- Carl Zeiss, Germany). Dorsal skins were processed for western blotting.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between pairs of groups were analyzed statistically by Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 5 software v5.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc. USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or from the corresponding author upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI16C1501); by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI15C0001). This work was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant, funded by the Korean government (MSIP; no. NRF- 2015M2A2A7A01045177) and by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1A02936968). Rajendran RL and Gangadaran P were supported by Kyungpook National University International Graduate Scholarships (KINGS) from Kyungpook National University, Republic of Korea.

Author Contributions

R.R.L. (first author) conceived, designed, and performed the experiments, as well as analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. P.G. performed the experiments, as well as analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.S.B., J.M.O., S.K., H.W.L., S.H.B. and L.Z. performed the experiments. Y.K.S., S.Y.J., S.-W.L. and J.L. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and revised the manuscript. B.-C.A. (corresponding author) contributed to the study by conceiving and designing experiments, revising the manuscript, and approving the final version. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15505-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gordon KA, Tosti A. Alopecia: evaluation and treatment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2011;4:101–106. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotsarelis G, Millar SE. Towards a molecular understanding of hair loss and its treatment. Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7:293–301. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paus R, Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:491–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paus R. Principles of hair cycle control. J. Dermatol. 1998;25:793–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller-Röver S, et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McElwee KJ, Shapiro JS. Promising therapies for treating and/or preventing androgenic alopecia. Skin Ther. Lett. 2012;17:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004;150:186–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C, Messenger AG. Improvement in scalp hair growth in androgen-deficient women treated with testosterone: a questionnaire study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166:274–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, L. et al. Treatment of MSCs with Wnt1a-conditioned medium activates DP cells and promotes hair follicle regrowth. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gangadaran P, Hong CM, Ahn B-C. Current Perspectives on In Vivo Noninvasive Tracking of Extracellular Vesicles with Molecular Imaging. BioMed Res. Int. 2017;2017:9158319. doi: 10.1155/2017/9158319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalimuthu S, et al. In Vivo therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles with optical imaging reporter in tumor mice model. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30418. doi: 10.1038/srep30418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsuda T, Kosaka N, Takeshita F, Ochiya T. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Proteomics. 2013;13:1637–1653. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu G, et al. Exosomes secreted by human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate limb ischemia by promoting angiogenesis in mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015;6:10. doi: 10.1186/scrt546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Emerging potential of exosomes for treatment of traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2017;12:19–22. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.198966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Théry, C., Amigorena, S., Raposo, G. & Clayton, A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 3, Unit 3.22 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tang L, et al. The expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 in follicular dermal papillae correlates with therapeutic efficacy of finasteride in androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;49:229–233. doi: 10.1067/S0190-9622(03)00777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato N, Leopold PL, Crystal RG. Induction of the hair growth phase in postnatal mice by localized transient expression of Sonic hedgehog. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:855–864. doi: 10.1172/JCI7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rishikaysh P, et al. Signaling Involved in Hair Follicle Morphogenesis and Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:1647–1670. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, et al. Versican gene: regulation by the β-catenin signaling pathway plays a significant role in dermal papilla cell aggregative growth. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012;68:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tetta C, Ghigo E, Silengo L, Deregibus MC, Camussi G. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Endocrine. 2013;44:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9839-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pegtel, D. M., Peferoen, L. & Amor, S. Extracellular vesicles as modulators of cell-to-cell communication in the healthy and diseased brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Simpson, R. J., Kalra, H. & Mathivanan, S. ExoCarta as a resource for exosomal research. J. Extracell. Vesicles1 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.van der Grein, S. G. & Nolte-’t Hoen, E. N. M. “Small Talk” in the Innate Immune System via RNA-Containing Extracellular Vesicles. Front. Immunol. 5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Fujita Y, Yoshioka Y, Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicle transfer of cancer pathogenic components. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:385–390. doi: 10.1111/cas.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varghese, J., Griffin, M., Mosahebi, A. & Butler, P. Systematic review of patient factors affecting adipose stem cell viability and function: implications for regenerative therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Lin, H.-T., Otsu, M. & Nakauchi, H. Stem cell therapy: an exercise in patience and prudence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.El-Badawy A, et al. Adipose Stem Cells Display Higher Regenerative Capacities and More Adaptable Electro-Kinetic Properties Compared to Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37801. doi: 10.1038/srep37801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peister A, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai M, et al. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BM-MSCs) Improve Heart Function in Swine Myocardial Infarction Model through Paracrine Effects. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28250. doi: 10.1038/srep28250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Z, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells as a therapeutic treatment for ischemic stroke. Neurosci. Bull. 2014;30:524–534. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1431-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo S-C, et al. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma promote the re-epithelization of chronic cutaneous wounds via activation of YAP in a diabetic rat model. Theranostics. 2017;7:81–96. doi: 10.7150/thno.16803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai RC, et al. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos R, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Plikus MV. Hair follicle signaling networks: a dermal papilla-centric approach. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2013;133:2306–2308. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindoso RS, et al. Extracellular vesicles released from mesenchymal stromal cells modulate miRNA in renal tubular cells and inhibit ATP depletion injury. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:1809–1819. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeurissen S, et al. The isolation of morphologically intact and biologically active extracellular vesicles from the secretome of cancer-associated adipose tissue. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2017;11:196–204. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2017.1279784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Escrevente C, Keller S, Altevogt P, Costa J. Interaction and uptake of exosomes by ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan, Z., Kolluri, K. K., Gowers, K. H. C. & Janes, S. M. TRAIL delivery by MSC-derived extracellular vesicles is an effective anticancer therapy. J. Extracell. Vesicles6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Han JH, et al. Effect of minoxidil on proliferation and apoptosis in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicle. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2004;34:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmad S, Singh N, Glazer RI. Role of AKT1 in 17beta-estradiol- and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)-dependent proliferation and prevention of apoptosis in MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:425–430. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alam H, et al. Fascin overexpression promotes neoplastic progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cory S, Huang DCS, Adams JM. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millar SE. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002;118:216–225. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenn KS, Cotsarelis G. Bioengineering the hair follicle: fringe benefits of stem cell technology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005;16:493–497. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young T-H, Lee C-Y, Chiu H-C, Hsu C-J, Lin S-J. Self-assembly of dermal papilla cells into inductive spheroidal microtissues on poly(ethylene-co-vinyl alcohol) membranes for hair follicle regeneration. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3521–3530. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2005;132:3151–3161. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung A, et al. The invasion front of human colorectal adenocarcinomas shows co-localization of nuclear beta-catenin, cyclin D1, and p16INK4A and is a region of low proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yano K, Brown LF, Detmar M. Control of hair growth and follicle size by VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:409–417. doi: 10.1172/JCI11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balañá ME, Charreau HE, Leirós GJ. Epidermal stem cells and skin tissue engineering in hair follicle regeneration. World J. Stem Cells. 2015;7:711–727. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i4.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozeki M, Tabata Y. Promoted growth of murine hair follicles through controlled release of vascular endothelial growth factor. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2367–2373. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tavakkol A, et al. Expression of growth hormone receptor, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and IGF-1 receptor mRNA and proteins in human skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1992;99:343–349. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usatyuk PV, et al. Role of c-Met/PI3k/Akt Signaling in HGF-mediated Lamellipodia Formation, ROS Generation and Motility of Lung Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. jbc. 2014;M113:527556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsou, H.-K. et al. HGF and c-Met Interaction Promotes Migration in Human Chondrosarcoma Cells. PLoS ONE8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Kim, C. H., Moon, S. K., Bae, J. H., Lee, J. H. & Choi, E. C. Effect of HGF in Proliferation, Dispersion and Migration of Hypopharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 48, 208–215 (2005).

- 54.Wiklander OPB, et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;4:26316. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munagala R, Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Gupta RC. Bovine milk-derived exosomes for drug delivery. Cancer Lett. 2016;371:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee, J.-K. et al. Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Suppress Angiogenesis by Down-Regulating VEGF Expression in Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Ono M, et al. Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells contain a microRNA that promotes dormancy in metastatic breast cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gangadaran, P. et al. Extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells activates VEGF receptors and accelerates recovery of hindlimb ischemia. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.022 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Aktas H, Alan S, Türkoglu EB, Sevik Ö. Could Topical Minoxidil Cause Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy? J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR. 2016;10:WD01-02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19679.8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossi A, et al. Minoxidil use in dermatology, side effects and recent patents. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2012;6:130–136. doi: 10.2174/187221312800166859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Millar SE, et al. WNT signaling in the control of hair growth and structure. Dev. Biol. 1999;207:133–149. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen D, Jarrell A, Guo C, Lang R, Atit R. Dermal β-catenin activity in response to epidermal Wnt ligands is required for fibroblast proliferation and hair follicle initiation. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2012;139:1522–1533. doi: 10.1242/dev.076463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, et al. Reciprocal requirements for EDA/EDAR/NF-kappaB and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways in hair follicle induction. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang C-C, Cotsarelis G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2010;57:2. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soma T, Tajima M, Kishimoto J. Hair cycle-specific expression of versican in human hair follicles. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2005;39:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oh HS, Smart RC. An estrogen receptor pathway regulates the telogen-anagen hair follicle transition and influences epidermal cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12525–12530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kulessa H, Turk G, Hogan BL. Inhibition of Bmp signaling affects growth and differentiation in the anagen hair follicle. EMBO J. 2000;19:6664–6674. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castilho RM, Squarize CH, Chodosh LA, Williams BO, Gutkind JS. mTOR mediates Wnt-induced epidermal stem cell exhaustion and aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Plikus MV. New Activators and Inhibitors in the Hair Cycle Clock: Targeting Stem Cells’ State of Competence. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132:1321–1324. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kwack MH, Kang BM, Kim MK, Kim JC, Sung YK. Minoxidil activates β-catenin pathway in human dermal papilla cells: a possible explanation for its anagen prolongation effect. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011;62:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dmello C, et al. Vimentin regulates differentiation switch via modulation of keratin 14 levels and their expression together correlates with poor prognosis in oral cancer patients. PloS One. 2017;12:e0172559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li XJ, et al. Role of pulmonary macrophages in initiation of lung metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;139:2583–2592. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu L, et al. Exosomes Derived From Natural Killer Cells Exert Therapeutic Effect in Melanoma. Theranostics. 2017;7:2732–2745. doi: 10.7150/thno.18752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aldhalimi MA, Hadi NR, Ghafil FA. Promotive effect of topical ketoconazole, minoxidil, and minoxidil with tretinoin on hair growth in male mice. ISRN Pharmacol. 2014;2014:575423. doi: 10.1155/2014/575423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all the relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or from the corresponding author upon request.