Abstract

Phospholipase A2-like (PLA2-like) proteins contribute to the development of muscle necrosis in Viperidae snake bites and are not efficiently neutralized by current antivenom treatments. The toxic mechanisms of PLA2-like proteins are devoid of catalytic activity and not yet fully understood, although structural and functional experiments suggest a dimeric assembly and that the C-terminal residues are essential to myotoxicity. Herein, we characterized the functional mechanism of bothropic PLA2-like structures related to global and local measurements using the available models in the Protein Data Bank and normal mode molecular dynamics (NM-MD). Those measurements include: (i) new geometric descriptions between their monomers, based on Euler angles; (ii) characterizations of canonical and non-canonical conformations of the C-terminal residues; (iii) accessibility of the hydrophobic channel; (iv) inspection of ligands; and (v) distance of clustered residues to toxin interface of interaction. Thus, we described the allosteric activation of PLA2-like proteins and hypothesized that the natural movement between monomers, calculated from NM-MD, is related to their membrane disruption mechanism, which is important for future studies of the inhibition process. These methods and strategies can be applied to other proteins to help understand their mechanisms of action.

Introduction

Phospholipase A2-like (PLA2-like) proteins, also known as homologue-phospholipase A2 or K49-PLA2s, are widespread in the snake venom of Viperidae family members. PLA2-like proteins conserve the general phospholipase A2 scaffold, but they possess natural mutations in the calcium binding loop that preclude phospholipid hydrolysis1. Despite not being enzymes, PLA2-like proteins disrupt sarcolemma integrity by disrupting ionic homeostasis2. As a consequence, calcium influx induces hypercontraction of myofilaments, mitochondrial damage and activation of cytosolic enzymes, which increase cell damage and lead to muscle necrosis2,3. In Viperidae snake bites, muscle necrosis occurs due to PLA2-like proteins, phospholipases A2 and metalloproteinases, which is a problem with current antivenom treatment, as this injury is not easily reversed4. This is particularly alarming in Central and South America, where most accidents are caused by snakes from the Bothrops genus (American lance heads)5.

PLA2-like proteins are myotoxic, and the broad spectrum of toxicity observed in in vitro experiments impacts different human cells, bacteria, fungi and parasitic organisms6. Understanding these molecular mechanisms may lead to the development of molecules against pathogenic agents7. With regard to human diseases, inflammation, autoimmune disorders and cancer have been correlated with excess of endogenous phospholipases A2; therefore, understanding the associated activities of snake venom toxins may also support the development of strategies to suppress this hyperactivity8.

The disturbance of membranes by PLA2-like proteins has been associated with C-terminal residues9,10 and is enhanced if the quaternary structure is a homodimeric assembly11,12. Under physiological conditions, dimers are observed by dynamic light scattering13–15, non-reducing SDS-PAGE results16–20, and SAXS experiments21. Two different dimers have been proposed according to crystallography experiments: a large dimer with an interface composed of β-wings and a compact dimer with an interface composed of calcium binding loops. In this article, we assume that the former dimeric assembly is the biologically relevant configuration based on SAXS experiments21.

Based on the compact dimer and PLA2-like dimeric structures, dos Santos et al. proposed a PLA2-like interface binding surface (iFace)22. This proposition was inspired by a picture proposed by Bahnson23 in which sulphates ions form a plane in PLA2 dimeric crystal structures and mimic the phosphate head groups of membrane phospholipids. In the PLA2-like models, these sulphates interact with a cluster of basic residues on the C-terminus, called the membrane docking site (MDoS)14. The PLA2-like iFace is formed after these protein monomers are reoriented due to the entrance of hydrophobic molecules into the toxin hydrophobic channel14,22,24. With this allosteric activation, a cluster of hydrophobic residues is rearranged in both monomers to form the membrane disruption site (MDiS)24, which interacts with phospholipids and perturbs membrane integrity14.

Independent research groups characterized the different states of PLA2-like crystal structures by measuring the angles between their monomers. Da Silva-Giotto et al. and Magro et al. hypothesized that the flexibility observed in the different arrangements of monomers, characterized by a single angle measurement, is related to the disruption of the membrane25,26. Dos Santos et al. characterized allosteric activation by the toxin by classifying models into either inactive or active states based on a two-angle description22. This quaternary structural flexibility and its relationship to function can be evaluated using molecular dynamics (MD) with normal mode (NM) analysis, since low-frequency NM can describe real-world protein motions and relate them to fundamental biological properties27,28.

Herein, we characterize allosteric activation of PLA2-like proteins and the membrane disruption mechanism using global and local measurements of the available bothropic PLA2-like structures and corresponding MD-NM analyses. These measurements include: (i) new geometric descriptions of monomer orientation based on Euler angles; (ii) characterizations of canonical and non-canonical conformations of the C-terminal residues; (iii) accessibility of the hydrophobic channel; (iv) inspection of ligands; and (v) distance of clustered residues to the toxin interface to the membrane. By using these integrated analyses, we expand the description of the PLA2-like protein action mechanism, which may be important in understanding the inhibition process.

Results and Discussion

Tertiary structure variability: local measurement using the Cα and Cβ distances

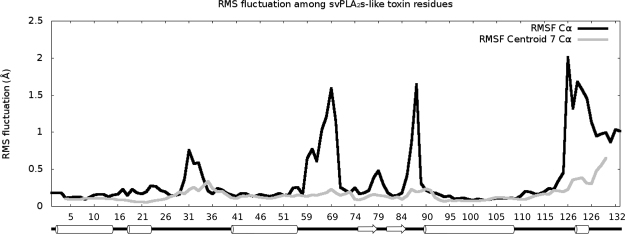

PLA2-like proteins are small (molecular weight of approximately 14 kDa), with seven disulfide bridges and the following secondary structural elements: a N-terminal helix, putative calcium binding loop residues, two long antiparallel α-helices at the core of the protein that make up the hydrophobic channels, two antiparallel β-sheets known as β wings, one short 310 helix and C-terminal loop region. Among the PLA2-like models, two specific regions have greater variation, with root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of Cα values (calculation description is provided in Material and Methods - geometrical description between identical monomers) above 1.5 Å (black line in Fig. 1). Flexible regions are usually related to functions, as dynamic structural alterations are part of substrate binding and enzymatic actions or interactions29. First, the labile region at residues 86 and 87 (with 2.2 and 1.6 Å variations, respectively) was previously reported as a region that oscillates between two metastable conformations25. A second region, which contains the most variable residues, is in the C-terminal region of the toxin (black line in Fig. 1), where two residues (121 and 125) were suggested to be responsible for toxin-induced membrane disruption and named MDiS14.

Figure 1.

Graph of the RMSF in Å by residues of available bothropic PLA2-like crystallographic structures. The RMSF values of Cα and centroid of 7 consecutive Cα are coloured in black and grey, respectively. Secondary structure is shown below residue numbers with helices and sheets represented by cylinders and arrows, respectively (extracted from PDB).

MDiS is composed of residues 121 and 125, which are hydrophobic and exposed to the solvent in a short 310 helix, together with residues 122 and 12324. This secondary structure is stabilized by one hydrogen bond between the main chain atoms of residues 121 and 12524. K122 is the only conserved C-terminal residue among PLA2-like proteins, although the hydrophobic character of residues 121 and 125 is also conserved14. MDiS is characterized by a Cβ distance between residues 121 and 125 (dMDiS) below 5.5 Å. In active state structures, both monomers are similar with this canonical conformation of MDiS (Tables 1 and 2). In inactive state structures, monomers are asymmetrical, with one in a non-canonical conformation and a dMDiS higher than 9 Å, as these residues are in an extended loop structure (Tables 1 and 2)24. Inact is the only inactive state structure with a non-canonical conformation, with a dMDiS of 8.5 Å; MDiS is in an intermediate state24.

Table 1.

Summary of local and global measurements of PLA2-like crystallographic models.

| State | PDBs | Ligands | Angles (°) | dMDiS (Å) | Tunnel (Å3) | toxin | Res | SG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CanMon | N-CanMon | Monomer | |||||||||||

| Sp | Ts | Ap | A | B | A | A | B | ||||||

| Inactive | 1PA0* | — | 141 | 26 | 54 | — | 4.8 | 10.8§ | 0 | 331 | Bnsp-VII | 2.2 | P3121 |

| 2Q2J | 1 sulfate/2 TRIS | 141 | 27 | 53 | — | 4.9 | 10.9 | 0 | 267 | PrTX-I | 1.65 | P3121 | |

| 3 HZD | — | 141 | 27 | 54 | — | 4.8 | 11.2 | 0 | 270# | BthTX-I | 1.91 | P3121 | |

| 3I3H | — | 140 | 27 | 53 | — | 4.6 | 9.3 | 0 | 251 | BthTX-I | 2.17 | P3121 | |

| 4K09 | — | 142 | 27 | 52 | — | 4.5 | 10.8 | 0 | 233 | BbTX-II | 2.11 | P3121 | |

| 4WTB* | 3 zinc/2 sulfates | 141 | 27 | 54 | — | 4.7 | 10.3 | 0 | 265 | BthTX-I | 2.16 | P3121 | |

| 2H8I (inact) | 1 PEG | 141 | 27 | 55 | — | 4.9 | 8.5 | 0 | 242# | BthTX-I | 1.9 | P3121 | |

| Active | 1QLL (acti3) | 2 n -tridecanoic acids | 163 | 20 | 81 | 5.2 | 5.2 | — | 241 | 206 | PrTX-II | 2.04 | P21 |

| 4KF3 | 4 PEGs/6 isopropanol | 169 | 24 | 47 | 4.4 | 4.4 | — | 385 | 405 | MjTX-II | 1.92 | P212121 | |

| 1XXS* (acti2) | 4 stearic acids/5 sulfate | 170 | 25 | 45 | 4.7 | 4.4 | — | 405 | 446 | MjTX-II | 1.8 | P212121 | |

| 4YV5* | 2 suramin/3 PEGs/7 sulfates | 170 | 24 | 47 | 4.9 | 5 | — | 408 | 406 | MjTX-II | 1.9 | P212121 | |

| 1Y4L* | 1 suramin/2 PEGs/5 isopropanol | 167 | 23 | 43 | 4.6 | 4.8 | — | 483 | 471 | BaspTX-II | 1.7 | P212121 | |

| 3QNL | 1 rosmarinic acid/1 PEG/8 isopropanol | 173 | 24 | 34 | 4.8 | 5.2 | — | 459 | 484 | BthTX-I | 1.77 | P212121 | |

| 4YZ7 | 1 aristolochic acid/1 PEG/5 sulfates | 181 | 28 | 27 | 4.7 | 4.8 | — | 364 | 417 | PrTX-I | 1.95 | P21212 | |

| 4YU7 | 4 caffeic acids/3 PEGs/1 sulfate | 177 | 27 | 27 | 4.7 | 5 | — | 509 | 433 | PrTX-I | 1.65 | P21 | |

| 2OK9 | 2 BPBs/2 isopropanol | 180 | 29 | 25 | 4.5 | 5.3 | — | 458 | 387 | PrTX-I | 2.34 | P21 | |

| 3CYL | 2 a-tocopherols/1 PEG/5 sulfates | 177 | 28 | 27 | 4.5 | 5.3 | — | 532 | 406 | PrTX-I | 1.87 | P21 | |

| 3CXI | 2 a-tocopherols/1 PEG/4 sulfates | 178 | 28 | 26 | 4.7 | 5.1 | — | 415 | 432 | BthTX-I | 1.83 | P21 | |

| 4K06 | 3 PEGs/5 sulfates | 178 | 28 | 27 | 5.1 | 4.9 | — | 458 | 429 | BbTX-II | 2.08 | P21 | |

| 3IQ3 (acti1) | 3 PEGs/2 sulfates | 177 | 27 | 27 | 4.7 | 5.2 | — | 473 | 391 | BthTX-I | 1.55 | P21 | |

| 3MLM | 2 myristic acids/4 sulfates | 178 | 28 | 28 | 4.6 | 5.4 | — | 312 | 460 | BnIV | 2.2 | P21 | |

The abbreviations are related to roll angle (R), twist angle (Ts), tilt angle (Ti), the distance between the two Cβ MDiS residues (dMDiS), canonical monomer (CanMon), non-canonical monomer (N-CanMon), resolution (Res), Space Group (SG), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and p-bromophenacyl bromide (BPB). The toxins (TX) Bnsp, Pr, Bth, Bb, Mj, Basp, and Bn are purified from the venom of Bothrops pauloensis, Bothrops pirajai, Bothrops jararacussu, Bothrops brazili, Bothrops moojeni, Bothrops asper and Bothrops neuwiedi, respectively. In Ligands column, PLA2-like protein inhibitors, negative and hydrophobic natural compounds are in dashed, italic, and bold font, respectively. *Chain letter A and B were inverted. #Side chain of H120 had to be remodeled for tunnel calculation. §125 Cβ was absent in model, and it was manually generated.

Table 2.

Summary of local and global measurements of PLA2-like crystallographic models.

| State | Ligands | PDBs | Angles | dMDiS (Å) | Tunnel (Å3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CanMon | N-CanMon | Monomer | ||||||||

| Roll | Twist | Tilt | A | B | A | A | B | |||

| INACTIVE | — | 1PA0, 2Q2J, 3HZD, 3I3H, 4K09, 4WTB, 2H8I | 141 (0.6) | 27 (0.4) | 54 (1.0) | — | 4.7 (0.2) | 10.3 (0.9) | 0 | 266 (29.6) |

| ACTIVE | Hydrophobic and negative molecules | All below | 174 (5.5) | 26 (2.6) | 37 (15.4) | 4.7 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.3) | — | 422 (78.5) | 412 (66.2) |

| 3QNL, 4YZ7, 4YU7, 2OK9, 3CYL, 3CXI, 4K06, 3IQ3, 3MLM | 178 (2.2) | 27 (1.4) | 28 (2.6) | 4.7 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.2) | — | 442 (69.0) | 427 (31.3) | ||

| 4KF3, 1XXS, 4YV5, 1Y4L | 169 (1.4) | 24 (0.8) | 46 (1.9) | 4.7 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.3) | — | 420 (43.1) | 432 (32.3) | ||

| 1QLL | 163 | 20 | 81 | 5.2 | 5.2 | — | 241 | 206 | ||

The abbreviations are related to the distance between the two Cβ MDiS residues (dMDiS), canonical monomer (CanMon), and non-canonical monomer (N-CanMon). Inactive state represents the structures whose PDB IDs are: 1PA0*, 2Q2J, 3HZD, 3I3H, 4K09, 4WTB*, 2H8I. The active state represents the structures whose PDB IDs are: 4KF3, 4YV5*, 1XXS*, 1Y4L*, 3QNL, 4YZ7, 3CYL, 3CXI, 4YU7, 2OK9, 4K06, 3IQ3, 3MLM. *Chain letter A and B were inverted.

Characterization and accessibility of the hydrophobic channel of PLA2-like toxins

Bothropic PLA2-like proteins have a cavity that is surrounded by positive and hydrophobic residues that participate in the binding of fatty acids1. The entrance of fatty acids into the hydrophobic channel of the toxin is hypothesized to be essential to induce dimer reorientation from the inactive to active state, a key step of the myotoxic mechanism of action14,22. To better characterize the allosteric activation induced by the entrance of hydrophobic molecules, we evaluated the accessibility of the hydrophobic channel through the iFace of the protein using CAVER software.

All canonical monomers contain a hydrophobic channel that is accessible through C-terminal residues. The PLA2-like structures in the inactive state only contain the accessible hydrophobic channel in monomers that are in the canonical conformation with a volume ~266 Å3 (Table 2). Curiously, the hydrophobic channels of the canonical monomers of BthTX-I/PEG400 and apo1 BthTX-I are closed by the side chain of H120, whereas they are open in the available models of other bothropic PLA2-like proteins24.

PLA2-like structures in the active state have symmetrical monomers, and the calculated tunnel is occupied by ligands, such as fatty acids, PEG molecules or inhibitors (Supplementary Table S1). Most of the calculated hydrophobic channels have a volume of ~400 Å3, with the exception of PrTX-II/n-tridecanoic acid, whose volumes are ~223 Å3 (Table 2). MjTX-II has an insertion at residue 120 compared to the other bothropic toxins (BaspTX-II, BbTX-II, BnIV, BnSP-VII, BthTX-I, PrTX-I and PrTX-II); thus, instead of the hydrophobic channel exiting through the middle region of the N-terminal helix, it is shifted to the beginning of the N-terminal helix15. Despite these differences, all of the calculated hydrophobic channels structurally connect the C-terminal region of one monomer to the N-terminal region and interior of the two parallel α-helices of the other monomer. The N-terminal region with its hydrophobic residues may participate in toxin activity30,31 and may be related to membrane interactions, similar to the MDiS.

Global measurements: orientation and translations between almost identical objects

The orientation between the monomers of available PLA2-like models are remarkably different and are related to the symmetrical and asymmetrical hydrophobic channel accessibility of active and inactive states structures, respectively. Previous efforts attempted to characterize the different orientations of models by one25 or two angles descriptions22. Herein, we update this angle description with a more intuitive, general and informative methodology. Since these structures are homodimers, we characterize the monomers orientation by describing the necessary rotation in Euler angles to superpose one monomer onto the other.

Han et al. used a similar approach to study the interdomain geometry between two domains of homologous proteins32. They described domain motion with a single translation and single rotation. Hayward wrote the DYNDOM software (fizz.cmp.uea.ac.uk/dyndom) to determine the hinge axes and measure closure or twist motions in a single angle description by using two conformations of the same protein33. With more than 20 available crystallographic structures, our approach differs, as we distinguish PLA2-like models using replicable and independent metrics based on Euler angles (Fig. 2).

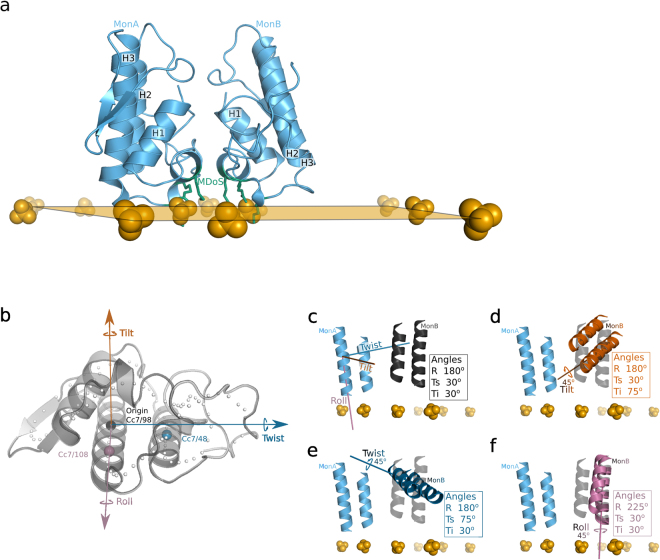

Figure 2.

Representation of the PLA2-like protein iFace and proposed axes of movement. Sulphate ions are represented as orange spheres and compose a plane that indicates the PLA2-like iFace (in a). N- and C-terminal residues compose this iFace, which includes a membrane docking site represented by green sticks in (a) that interacts with sulphates. In (b) the PLA2-like monomer is represented by a grey cartoon with Cc7 represented as spheres. The axes are established by Cc7/98 as the origin and coloured black; by Cc7/108 as the X-axis and coloured magenta; by a perpendicular vector to the X-axis, in the plane composed by X-axis and Cc7/48 sphere, as the Y-axis and coloured dark blue; and the normal vector to the XY plane coloured vermilion. In (c–f) the two antiparallel helices are illustrated to indicate different orientations of monomer A (light blue) corresponding to monomer B; the calculated angles are shown in the box. Tilt is coloured in vermilion, twist in dark blue and roll in dark blue. In (c–f) monomer B, coloured in black, is close to the orientation of BnIV/myristic acid structure (PDB id: 3MLM), which is established as a reference to show a difference of 45° in each of the axes of movement. The axes in (d–f) are shown as illustrations of the rotation that describes monomer B in transparent black relative to the other monomer, which is not transparent.

In our angle description and inspired by the DNA angular base pair parameters34, we called the angles tilt, twist and roll for the X, Y and Z axes, respectively (Fig. 2b–f and the calculation description is provided in Material and Methods - geometrical description between identical monomers). The X-axis is the centre of the longest α-helix (H3), the Y-axis is the vector that connects the X-axis to the other antiparallel α-helix (H2), and the Z-axis (orange axis in Fig. 2b) is the normal vector of the plane XY. Among the evaluated dimers, twist (Ts) is the angle with the lowest divergence and a value close to 25° in all samples (Tables 1 and 2). The roll angles (R) separate inactive and active states. The former is composed of the apo BnSP-VII, apo PrTX-I, apo1&2 BthTX-I, apo BbTX-II, BthTX-I/Zn2+ and BthTX-I/PEG400 (inact) structures, which have a roll of ~140° and tilt (Ti) of ~55° (Tables 1 and 2). All of these models are apo structures (Supplementary Table S1), with exception of BthTX-I/Zn2+ and apo PrTX-I, which have charged molecules or ions bound. Moreover, inact has a small PEG molecule inside the hydrophobic channel that induces dMDiS shortening (8.5 Å)24.

The structures in the active state have a roll angle greater than 160° (Tables 1 and 2). They are complexed with inhibitor molecule(s) or natural compound(s) in the hydrophobic channel (Supplementary Table S1), which agrees with the accessibility calculation of the previous sub item. Most of these structures have abundant negative molecules surrounding the protein, being the R34 and PLA2-like iFace [considered the side chains of residues 16, 17, 20, 115 and 118 (MDoS)] the most common region. This environment, which is rich in hydrophobic and negative molecules, may mimic a membrane interaction23. Roll angles of the active state close to 180° are closer to a symmetrical orientation, which may be the optimal exposure of same residues of both monomers in the protein iFace.

Most angles of active state models are similar, but they can be further separated according to their tilt angles in: 1) ~30: BthTX-I/PEG4k (acti1), BnIV/myristic acid, MTX-II/PEG4k, PrTX-I/BPB, PrTX-I/caffeic acid+PEG4k, BthTX-I/α-tocopherol, PrTX-I/α-tocopherol, PrTX-I/aristolochic acid+PEG4k, and PrTX-I/rosmarinic acid+PEG330; 2) ~50: BaspTX-II/suramin, MjTX-II/stearic acid (acti2), MjTX-II/suramin+PEG4k, and MjTX-II/PEG4k; ii.3) ~80: PrTX-II/n-tridecanoic acid (acti3) (Table 2). Especially for acti3, the higher tilt angle causes a shortening of the hydrophobic channels as their volumes are half of the hydrophobic channels of the other active models.

Evaluation of the flexibility of PLA2-like protein in active and inactive states

Analyzing the local and global measurements of available bothropic PLA2-like proteins, we identified two different states based on their roll angles: i) an inactive state (roll ~ 140°) that has an asymmetrical conformation with one non-canonical monomer and one hydrophobic channel accessible and ii) an active state (roll > 160°) with symmetrical canonical monomers and with both hydrophobic channels filled by hydrophobic molecules. It was hypothesized that for these toxins, the first state is converted to the second by an allosteric activation induced by the entrance of a hydrophobic molecule into the accessible hydrophobic channel24.

To address the allosteric activation hypothesis in silico, we evaluated the flexibility via NM-MD analysis of the BthTX-I models, as both inactive and active states were structurally determined. We chose inact and acti1 as representatives of the former and latter groups, respectively. In both cases, we evaluated flexibility in absence and presence of fatty acids, whereas PEG molecules available in the model were replaced by myristic acid.

PLA2-like activation

All of the models from inact and acti1 calculated from a ± 6.0 Å displacement of NM 7–9 had satisfactory energies, as the measured potential energies were smaller than 0.5 kcal/mol (Supplementary Fig. S2) and within order of magnitude of evaluated structures of other studies35,36. To observe the transition from one state to another, we compared the inact and acti1 models by superposing them on the corresponding NM-MD structures (Supplementary Table S3). Inact-FA/NM9/-3.1 Å (inact structure complexed to fatty acid minimized and displaced -3.1 Å among NM9) is the most similar to acti1, with a RMSD of 1.9 Å, and as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization has a minimum RMSD of 1.3 Å (Fig. 3a). The other calculated NMs of inact-FA have minimum RMSDs above 3 Å compared to acti1 (Supplementary Table S3). For the structures from NM calculations of apo-inact (without fatty acid), the most similar to acti1 had a RMSD of 2.8 Å and, as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization has a minimum RMSD of 1.2 Å (Supplementary Table S3). To confirm that lower amplitude NMs of apo-inact would not reach a better representation of acti1 model, the NM10–21 were also calculated, but with no better similarity than 2.8 Å. Therefore, the fatty acid in the canonical monomer of BthTX-I was fundamental for the toxin reach its active state (described by comparison with acti1) since the lowest RMSD obtained from inact-FA was almost 1 Å higher than apo-inact. Moreover, inact-FA/NM9 from −0.4 to −3.1 Å are the calculated structures that better describes the BthTX-I activation; such conformation changes will be further described as activation (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Video S5).

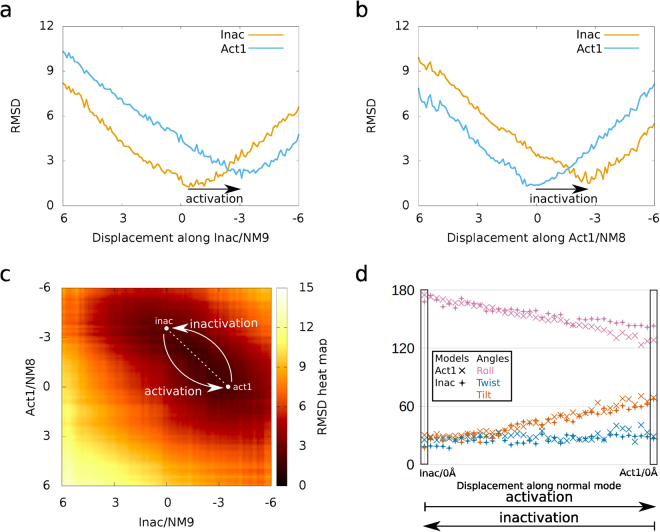

Figure 3.

Activation and inactivation descriptions using RMSD and proposed angles. In (a) inact/NM9/0 Å and -3Å structures resemble inact (orange line) and acti1 (blue line), respectively, describing the BthTX-I activation process. In (b) acti1/NM8/−3Å and 0 Å resemble inact (orange line) and acti1 (blue line), respectively, describing the BthTX-I inactivation process. In (c) the RMSD heat map demonstrates darker and lighter colours corresponding to high and low similarities, respectively. The structures from the dashed white transparent line from the white circle, which starts in act/NM8/−3.7 Å and inact/NM9/0 Å and ends in acti1/NM8/0 Å and inact/NM9/−3.7 Å, are similar and describe complementarity between activation and inactivation. In (d) the pairs of structures delimitated by the dashed white transparent line in (c) have similar angles, and activation is characterized by increase of roll, stability of twist and decrease of tilt angles. In (d) roll, twist, and tilt are coloured magenta, dark blue and vermilion, respectively, and models of acti1 and inact are represented by X and ◆, respectively.

For acti1-FA, the minimized structure on NM8/−2.7 Å is the most similar to inact, with a RMSD of 1.5 Å, and as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization has a minimum RMSD of 1.3 Å (Fig. 3b). The other calculated NMs of acti1-FA have a minimum RMSD, compared to inact, above 2.3 Å (Supplementary Table S3). For apo-acti1, the structure NM8/−2.1 Å is the most similar to inact with a RMSD of 1.7 Å, and as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization had a minimum RMSD of 1.8 Å (Supplementary Table S3). The presence of a fatty acid in both of canonical monomers of BthTX-I seems not essential for toxin acquiring its inactive state, as both apo-acti1 and acti1-FA NM8 reached similar representations of inact. Therefore, acti1-FA/NM8 from −2.7 to 0 Å are the calculated structures that better describes BthTX-I inactivation; such conformation changes will be further described as inactivation (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video S6).

To observe whether the activation and inactivation processes were complementary, we compared them by superposing inact-FA/NM9/±6 Å and acti1-FA/NM8/±6 Å and then plotting the RMSD in a heat map (Fig. 3c), with darker colours indicating similar structures. These two processes demonstrate that there is better agreement between inact-FA/NM9/−3.7 Å and acti1-FA/NM8/0 Å to inact-FA/NM9/0 Å and acti1-FA/NM8/−3.7 Å that are 38 consecutive superpositions with an average RMSD of 2.0 Å (shown by the dashed white transparent line in Fig. 3c). The angles from these paired structures correspond, as shown in Fig. 3d, which demonstrates the activation process as a movement that increases the roll angle and decreases the tilt angle. Therefore, our results suggest that the inactive state of PLA2-like proteins may transition to the active state through physically plausible movements in the presence of a fatty acid in the hydrophobic channel.

PLA2-like flexibility among active state models

PLA2-like structures may change to an active state from an inactive state after fatty acid interaction, which is described by an increase in the roll angles. Active state models may be further separated by tilt angles, with at least one model with both hydrophobic channels occupied by a fatty acid: acti1 (BthTX-I), with ~30°; acti2 (MjTX-II), with ~50°; and acti3 (PrTX-II), with ~80° (Table 2). Are these angles exclusive to a single toxin or are they a consequence of crystal packing? To address this question in silico, we evaluated their flexibility with NM-MD. Only the fatty acids in the toxin hydrophobic channels were maintained in the model.

All of the models from acti1, acti2, and acti3 containing fatty acids and calculated from a ± 6.0 Å displacement of NM 7–9 had satisfactory energies, as they had potential energies of less than 0.5 kcal/mol (Supplementary Fig. S2) and within order of magnitude of evaluated structures of other studies35,36. Among the calculated NM, NM7 of acti1–3 were the movements that best described the conversion from one conformation to the other, as observed by RMSD comparisons (Fig. 4a–c). For acti1/NM7, the minimum RMSD for the acti2 and acti3 models were 1.6 and 2.0 Å, respectively, which corresponded to the structures acti1/NM7/0.6 Å and acti1/NM7/5.4 Å, respectively; as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization had a minimum RMSD of 1.4 Å (Supplementary Table S3). For acti2/NM7, the minimum RMSD for acti1 and acti3 were 2.0 and 2.0 Å, respectively, which corresponded to the structures acti2/NM7/3.0 Å and acti2/NM7/−3.8 Å, respectively; as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization had a minimum RMSD of 1.5 Å. For acti3/NM7, the minimum RMSD for acti1 and acti2 were 3.3 Å and 3.1 Å, respectively, which both corresponded to the structure acti3/NM7/−4.5 Å; as a reference, the model itself prior to minimization had a minimum RMSD of 1.0 Å. The other structures from calculated NMs 8 and 9 of acti1, acti2, and acti3 had minimum RMSD values compared to the independent models higher than the obtained by NM7 (Supplementary Table S3). Therefore, NM7 better describes the movements of conversion between different active state models (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Video S7).

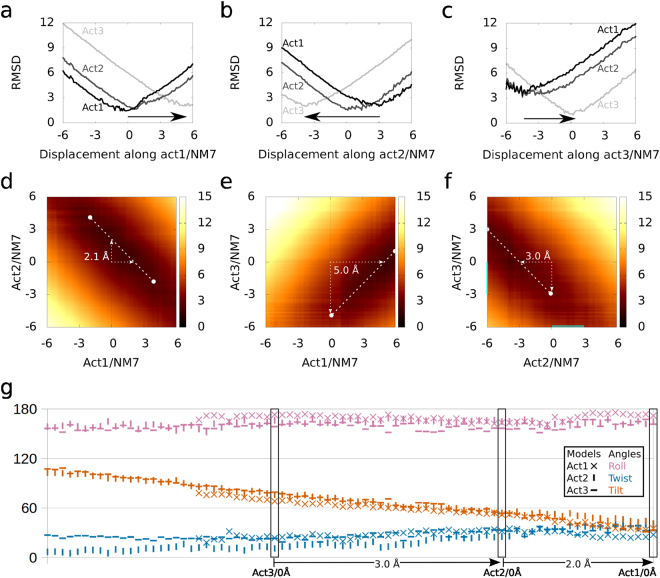

Figure 4.

Correspondence between NM7 of acti1–3 shown with the RMSD and proposed angles. In A, acti1/NM7/0 Å, 0.6 Å, and 5.4 Å structures resemble acti1, acti2, and acti3 crystallographic models, respectively. In (b) acti2/NM7/−3.8 Å, 0 Å, and 3.0 Å structures resemble acti1, acti2, and acti3 models, respectively. In (c) acti3/NM7/−4.5 Å, −4.5 Å, and 0 Å structures resemble acti1, acti2, and acti3 models, respectively. In (a–c) acti3, acti2, and acti1 are coloured in light grey, dark grey, and black, respectively. In (c–e) the RMSD heat map demonstrates darker and lighter colours as high and low similarities, respectively. The dashed white lines with circles on their edges correspond to the 60 lowest consecutive superpositions; therefore, 6 Å of highly correlated pair of structures. In (d) the NM7s of acti1 and acti2 are similar, with a shift of 2.1 Å, as shown by dashed white arrow. In (e) the NM7s of acti1 and acti3 are similar, with a shift of 5.0 Å, as shown by dashed white arrow. In (f) the NM7s of acti2 and acti3 are similar, with a shift of −3.0 Å, as shown by the dashed white arrow. In (g) the angles of the acti1–3/NM7 structures are plotted following the shift of (d–f). In (g) roll, twist, and tilt are coloured magenta, dark blue and vermilion, respectively, and the acti1, acti2, and acti3 structures are represented by X, │, and ─, respectively.

Figure 5.

Motion describing transition between different active state structures and interacting to the membrane. In (a,b) acti1 is represented by a blue cartoon with MDiS in yellow sticks, −6 Å displacement along normal mode 7 is represented by arrows, and the membrane, by the orange plane. (a,b) Show the same representation with a 90° rotation in the horizontal axis. In (c) scatter plot of distances of MDoS (dMDoSiFace) and MDiS to toxin iFace (dMDiSiFace) against tilt angles. In (c) structures from NM7/0 to −6 Å of acti1, 2, and 3 are represented by ⦁, ▴ and ▪, respectively.

The NM7 of these structures were correlated, as observed by the white dashed lines with a circle on the edges in the RMSD heat maps in Fig. 4d–f. These white dashed lines are the lowest 60 consecutive superpositions: 6 Å of highly correlated pairs of structures. The average RMSD for the superposition of these white dashed lines was 2.2, 2.6, and 2.8 Å for acti1/acti2, acti1/acti3, and acti2/acti3, respectively. Each NM7 had a different shift with respect to the other NM7, which was 2.1, 5.0, and 3.0 Å for acti1/acti2 (Fig. 4d), acti1/acti3 (Fig. 4e), and acti2/acti3 (Fig. 4f), respectively. The orientations between these paired structures, which were obtained by applying these shifts, corresponded (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Video S7). Therefore, our results suggest that the active state of PLA2-like structures with different tilt angles may be interchangeable by the described NM7s, which suggests that their mechanism of action is probably similar.

PLA2-like membrane disruption description

As the X-axis (measured by roll) is perpendicular to the plane of the protein iFace, the movements described by the other two orthogonal rotations, such as tilt, will change the orientations of the residues in the iFace. Therefore, the experimental flexibility observed in the tilt of the active state models and calculated NM7 models (Fig. 5) could be related to the disruption of the membrane in a clawing movement, as the C-terminal residues (MDiS) would move toward the plane of the iFace. Such a movement could pull phospholipids out of the membrane, disrupting its integrity, as hypothesized by Da Silva-Giotto et al.25. We calculated, along the direction of the tilt angle, a reduction in NM7 of active state PLA2-like proteins with fatty acids, tilt angles and MDiS approximations to the iFace (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Video S8). This approximation was evaluated by calculating the distance of the centroids of 121 Cβ and 125 Cβ to the plane of sulphates (dMDiSiFace). We calculated this distance using the plane equation with three sulphur atoms from the plane of sulphates in BnIV/myristic acid (shown in Fig. 2) after the dimers were superposed. The reduction of the tilt angles was correlated with dMDoSiFace and dMDiSiFace reductions (Fig. 5c). Therefore, the tilt variation among the crystal and NM-MD structures supports the hypothesis that reduced tilt angles correlate the MDoS and MDiS approximations to the toxin iFace.

Action mechanism

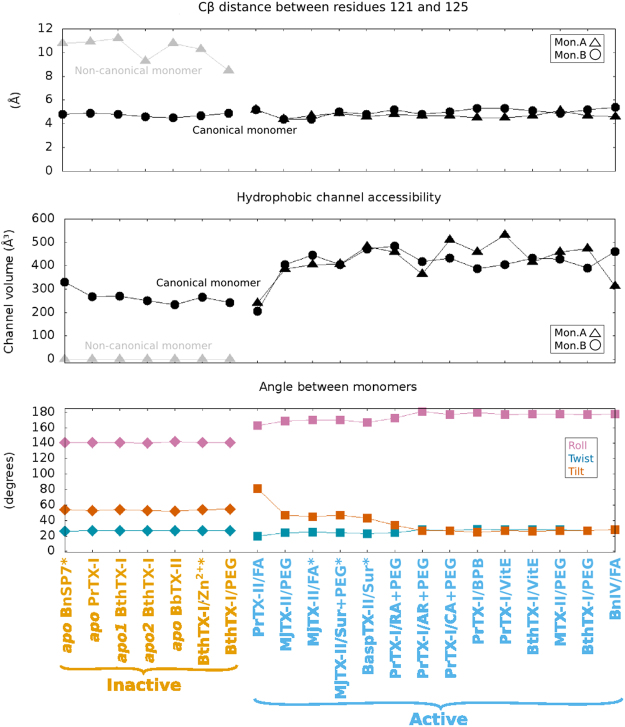

Based on these global and local analyses, we can better describe the various states of bothropic PLA2-like protein structures (Fig. 6). The inactive state of bothropic PLA2-like protein has monomers in an asymmetrical conformation. One monomer (A) is in a non-canonical conformation that does not have a MDiS cluster (dMDiS > 9 Å), and the hydrophobic channel is inaccessible (as observed by grey triangles of the orange structures in the dMDiS and the hydrophobic channel accessibility graphs shown in Fig. 6). The geometric relationship of the monomers is far from a symmetrical orientation, as the roll is distant to 180° (observed from angles of the orange structures in the monomer-monomer angle graph shown in Fig. 6). Both monomers of these structures lack hydrophobic molecules inside the hydrophobic channel.

Figure 6.

Distance between Cβs between residues 121 and 125, hydrophobic channel accessibility with the tunnel volume calculation, and monomer-monomer angles for all available bothropic PLA2-like toxins. The points refer to the structure shown in the abscissa of the third graph. In the first two graphs, monomers A and B are represented as ▴ and ⦁, respectively. In the monomer-monomer angle chart, the roll, twist, and tilt angles are coloured in magenta, vermilion and dark blue, respectively. The structures are coloured according to state, with inactive in orange and active in light blue. Toxins in an inactive state feature asymmetrical monomers, as one is non-canonical monomer with a MDiS distance greater than 8 Å and has hydrophobic channel closed (tunnel with volume 0) colored in grey in first two graphs, and its orientation relative to the other monomer is not symmetrical, as the numbers are far from 0 and 180°. Toxins in the active state possess both canonical monomers with MDiS distances close to 5 Å and both hydrophobic channels open, and the monomer-monomer orientation tends to a symmetrical relationship, as the angles tend to be either 0 or 180°. The abbreviations are related to polyethylene glycol (PEG), suramin (sur), α-tocopherol (VitE), and fatty acid (FA).

Due to the entrance of a hydrophobic molecule in the accessible toxin channel, the monomers are reoriented, with an increased roll angle towards 180°, to a more symmetrical relationship, leading to toxin activation. Active state models feature both monomers as being symmetrical with MDiS (dMDiS < 6 Å), and both hydrophobic channels are accessible (observed on the light blue structures in the MDiS distance and hydrophobic channel accessibility graphs in Fig. 6) and occupied by hydrophobic molecules. Despite these similarities, they differ according to their tilt angles in three primary categories, which are interchangeable according to NM calculations. Our data support that these differences are not related to a specific protein but are exclusive to a minimum energy level reached in the crystal packing, and different PLA2-like toxins may achieve the conformations of one another in solution. The reduction of the tilt angles precludes the MDiS approximation to the iFace, supporting this clawing movement as a membrane disruption mechanism (Supplementary Video S8).

In conclusion, we observed new structural features of PLA2-like toxins by measuring the MDiS distance, hydrophobic channel accessibility and geometric orientation between monomers from the available crystal and NM-MD structures. Our proposed geometrical description, with Euler angles, has proven to be useful for generating a detailed description of the dimeric arrangement of different PLA2-like toxin models, as we identified an inactive state and three active states. We also used this general description to interpret interchain movements according to MD studies after validating the model pairing by RMSD calculations. Moreover, this methodology can be used as a primary tool to characterize geometrically homodimeric protein models by quickly separating structures into groups and using the angles to intuitively interpret global flexibility, describing the mechanism of action.

Methods

Structures

The following structures, with the Protein Data Bank identification codes in parentheses (PDB id), were used: apo1 BthTX-I (3HZD), apo2 BthTX-I (3I3H), BthTX-I/Zn2+ (4WTB)24, BthTX-I/PEG4k [polyethylene glycol with an average weight of 4000 g/mol) (3IQ3)]13, BthTX-I/PEG400 (2H8I)21, BthTX-I/α-tocopherol (3CXI), PrTX-I/α-tocopherol (3CYL), apo PrTX-I (2Q2J)22, PrTX-I/BPB (2OK9)37, PrTX-I/rosmarinic acid+PEG330 (3QNL)38, PrTX-I/caffeic acid+PEG4k (4YU7), PrTX-I/aristolochic acid+PEG4k (4YZ7)39, PrTX-II/n-tridecanoic acid (1QLL)40, apo BnSP-VII (1PA0)26, apo BbTX-II (4K09), MTX-II/PEG4k (4K06)14, BaspTX-II/suramin (1Y4L)41, BnIV/myristic acid (3MLM)42, MjTX-II/stearic acid (1XXS)43, MjTX-II/PEG4k (4KF3)15, and MjTX-II/suramin+PEG4k (4YV5)44. The structures BthTX-I/BPB (3I03), apo BthTX-I (3I3I), apo BnSP-VI (1PC9), apo BaspTX-II (1CLP), and BbTX-II (4DCF) were not included because in the first two, their asymmetric unit (ASU) content is composed of a monomer, and in the others, the resolution was lower than or equal to 2.5 Å.

Bioinformatic tools

The software CAVER 3.0 (command line version)45 was used to characterize the toxin hydrophobic channel of the PLA2-like crystallographic models. Hydrophobic channels are referred to as tunnels by this algorithm. To improve the convergence of the different tunnels, the probe and shell radii were increased to 1.8 and 4, respectively. The calculated tunnels were manually inspected in PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7 Schrödinger, LLC.), and their volumes were calculated using the diameter and length of the tunnel. When PEGs or fatty acids were present in the model, the tunnel whose path filled this molecule was chosen. PyMOL and VMD (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/)46 was used to create cartoon and stick images.

Geometrical description between identical monomers

The geometric orientation between the monomers was measured by superposing one on the other and converting the matrix rotation into Euler angles (following the sequence 3,2,1 using the formulas from Section 8.11 of Diebel’s publication47). This is the most intuitive 3D rotation description as it uses each of the 3 axes once, such as the Tait-Bryan angles (row, pitch and yaw) used in aeronautics48.

Prior to the superposition calculations, the models were placed into immutable and standard orthogonal axes that relate structure to function. As the PLA2-like protein iFace forms a plane that is mostly composed of the N- and C-terminal regions of the protein, which are perpendicular to the two antiparallel α-helices (H2 and H3) (Fig. 2a), these two helices were used as references for two of the axes. To obtain the first axis in the direction and centre of the largest α-helix, the centroid of 7 consecutive carbon α (named herein as Cc7 and shown as grey spheres in Fig. 2b) was calculated. Approximately seven residues complete two α-helix turns. To facilitate the placement of different models in a common set of orthogonal axes, three Cc7s with small fluctuations were selected from the two longest helices, Cc7/48, Cc7/98 and Cc7/104, which had RMSF of 0.13, 0.08, and 0.08 Å, respectively (grey line in Fig. 1). The RMSF of Cα (black line in Fig. 1) was calculated after monomers were separated and superposed to a template (monomer A of BthTX-I/PEG4k). The RMSF of Cc7 was obtained using previous superposed structures. Cc7/98 was chosen as the origin, and Cc7/98 to Cc7/104 was used as the X-axis (magenta axis in Fig. 2b). The Y-axis was constructed as the perpendicular vector to the X-axis inside the plane composed of the X-axis and coordinate Cc7/48 (blue axis in Fig. 2b). One of the monomers was chosen as a reference to calculate the rotation matrix that was used to superpose it onto the other monomer.

The software lsqkab 49 was used to generate the required distances to calculate the RMSF and obtain the matrix rotation of the superpositions. The Ti, Ts and R angles were obtained from the rotation matrix. For the translation calculation, the distance between the centre of gravity of each monomer was obtained using the function gravity of mass available in PyMOL.

Normal mode analysis

The LF NMs movements of the bothropic PLA2-like toxin containing fatty acids in the hydrophobic channel were calculated by the CHARMM v.36b1 program50 and CHARMM36 force field51. The inactive state model inact and active state models acti1–3 were selected. As some of these models have PEGs inside the toxin hydrophobic channels, the ligands in acti1 and inact canonical monomers were replaced by myristic acids from the BnIV/myristic acid model after monomer-monomer Cα superposition. Since inact only has one canonical monomer, only one fatty acid was introduced in the structure. Inact and acti1 models absent of fatty acids were included in NM calculations. The topology and parameter files were generated by the CHARMM-GUI server (www.charmm-gui.org)52 by employing an additional energy minimization. The conjugated gradient algorithm was applied with harmonic constraints that were progressively decreased from 250 to 5 kcal/mol·Å2, with 100 steps of minimization at each decrease. The constraints were removed to carry out an additional 10,000 conjugated gradient steps, followed by 300,000 steps of the basis Newton-Raphson algorithm. The final minimized structure was used to calculate the three lowest frequencies NMs (7–9) using the VIBRAN module of CHARMM for the structures.

The structures were generated along each NM based on a short MD simulation at a low temperature (30 K) using the VMOD facility of CHARMM followed by a minimization afterwards. A maximum displacement range of 6.0 Å was established for each direction of the NM with a 0.1 Å projection step based on the values of the mass-weighted root mean square. For each of these steps, a constant harmonic force was applied over the Cα atoms (increasing from 1,000 until 10,000 kcal/mol·Å2), and a short MD simulation (1 ps) was carried out after each constant value, totalling 10 ps of simulation. The final structures were obtained by an additional 1,000 steps of conjugated gradient energy minimization maintaining the restraints. The miscellaneous mean field potential facility of CHARMM of the final structures was used for energy validation.

To relate NM to function, the distance of the essential cluster of residues to the PLA2-like iFace was calculated. This was accomplished by extracting the plane equation from the coordinates of 3 sulphurs of sulphates interacting with the protein iFace and calculating the distance from the chosen residues. To compare different NM motions in respect to the different states of PLA2-like proteins crystallographic structures, RMSD was calculated using these and the structures from NM analysis. The RMSD was calculated with lsqkab program. To illustrate NM motions, the principal component was calculated using the quasi-routine of the module VIBRAN of CHARMM to obtain the covariance matrix o Cα atomic displacements (according to Floquet et al.53).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPESP).

Author Contributions

R.J.B. performed the simulations and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. M.R.M.F., N.L. and R.J.B. designed and analyzed the experiments, and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15614-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rafael J. Borges, Email: rjborges@ibb.unesp.br

Marcos R. M. Fontes, Email: fontes@ibb.unesp.br

References

- 1.Fernandes, C. A. H., Borges, R. J., Lomonte, B. & Fontes, M. R. M. A structure-based proposal for a comprehensive myotoxic mechanism of phospholipase A2-like proteins from viperid snake venoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.09.015 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lomonte B, Gutiérrez JM. Phospholipases A2 From Viperidae Snake Venoms: How do They Induce Skeletal Muscle Damage? Acta Chim Slov. 2011;58:647–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montecucco C, Gutiérrez JM, Lomonte B. Cellular pathology induced by snake venom phospholipase A2 myotoxins and neurotoxins: common aspects of their mechanisms of action. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2008;65:2897–2912. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warrell DA. Snake bite. Lancet. 2010;375:77–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sant’Ana Malaque, C. M. & Gutiérrez, J. M. Snakebite Envenomation in Central and South America. in Critical Care Toxicology (eds Brent, J. et al.) 1–22, 10.1007/978-3-319-20790-2_146-1. (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

- 6.Lomonte B, Angulo Y, Sasa M, Gutiérrez JM. The phospholipase A2 homologues of snake venoms: biological activities and their possible adaptive roles. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:860–876. doi: 10.2174/092986609788923356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang TS, et al. Enzymatic toxins from snake venom: structural characterization and mechanism of catalysis: Enzymatic toxins from snake venom. FEBS J. 2011;278:4544–4576. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues RS, et al. Snake venom phospholipases A2: a new class of antitumor agents. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:894–898. doi: 10.2174/092986609788923266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chioato L, et al. Mapping of the structural determinants of artificial and biological membrane damaging activities of a Lys49 phospholipase A2 by scanning alanine mutagenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1247–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Núñez CE, Angulo Y, Lomonte B. Identification of the myotoxic site of the Lys49 phospholipase A(2) from Agkistrodon piscivorus piscivorus snake venom: synthetic C-terminal peptides from Lys49, but not from Asp49 myotoxins, exert membrane-damaging activities. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology. 2001;39:1587–1594. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Oliveira AH, Giglio JR, Andrião-Escarso SH, Ito AS, Ward RJ. A pH-induced dissociation of the dimeric form of a lysine 49-phospholipase A2 abolishes Ca2+-independent membrane damaging activity. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2001;40:6912–6920. doi: 10.1021/bi0026728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Oliveira AHC, Ferreira TL, Ward RJ. Reduced pH induces an inactive non-native conformation of the monomeric bothropstoxin-I (Lys49-PLA2) Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology. 2009;54:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandes CAH, et al. Comparison between apo and complexed structures of bothropstoxin-I reveals the role of Lys122 and Ca(2+)-binding loop region for the catalytically inactive Lys49-PLA(2)s. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;171:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandes CAH, et al. Structural bases for a complete myotoxic mechanism: Crystal structures of two non-catalytic phospholipases A2-like from Bothrops brazili venom. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1834:2772–2781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvador GHM, et al. Structural and functional studies with mytoxin II from Bothrops moojeni reveal remarkable similarities and differences compared to other catalytically inactive phospholipases A2-like. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology. 2013;72:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa TR, et al. Myotoxic phospholipases A2 isolated from Bothrops brazili snake venom and synthetic peptides derived from their C-terminal region: Cytotoxic effect on microorganism and tumor cells. Peptides. 2008;29:1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis B, Gutierrez JM, Lomonte B, Kaiser II. Myotoxin II from Bothrops asper (Terciopelo) venom is a lysine-49 phospholipase A2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991;284:352–359. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomonte B, Gutiérrez JM. A new muscle damaging toxin, myotoxin II, from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper (terciopelo) Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology. 1989;27:725–733. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues VM, et al. Geographic variations in the composition of myotoxins from Bothrops neuwiedi snake venoms: biochemical characterization and biological activity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1998;121:215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(98)10136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyama MH, et al. A quick procedure for the isolation of dimeric piratoxins-I and II, two myotoxins from Bothrops pirajai snake venom. N-terminal sequencing. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1995;37:1047–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murakami MT, et al. Interfacial surface charge and free accessibility to the PLA2-active site-like region are essential requirements for the activity of Lys49 PLA2 homologues. Toxicon Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinology. 2007;49:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.dos Santos JI, Soares AM, Fontes MRM. Comparative structural studies on Lys49-phospholipases A(2) from Bothrops genus reveal their myotoxic site. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;167:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahnson BJ. Structure, function and interfacial allosterism in phospholipase A2: insight from the anion-assisted dimer. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges RJ, et al. Functional and structural studies of a Phospholipase A2-like protein complexed to zinc ions: Insights on its myotoxicity and inhibition mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj. 2017;1861:3199–3209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Silva Giotto MT, et al. Crystallographic and spectroscopic characterization of a molecular hinge: conformational changes in bothropstoxin I, a dimeric Lys49-phospholipase A2 homologue. Proteins. 1998;30:442–454. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(19980301)30:4<442::AID-PROT11>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magro AJ, Soares AM, Giglio JR, Fontes MRM. Crystal structures of BnSP-7 and BnSP-6, two Lys49-phospholipases A(2): quaternary structure and inhibition mechanism insights. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;311:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandrov V, et al. Normal modes for predicting protein motions: a comprehensive database assessment and associated Web tool. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2005;14:633–643. doi: 10.1110/ps.04882105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas A, Hinsen K, Field MJ, Perahia D. Tertiary and quaternary conformational changes in aspartate transcarbamylase: a normal mode study. Proteins. 1999;34:96–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(19990101)34:1<96::AID-PROT8>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuglebakk E, Echave J, Reuter N. Measuring and comparing structural fluctuation patterns in large protein datasets. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2012;28:2431–2440. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Díaz C, Alape A, Lomonte B, Olamendi T, Gutiérrez JM. Cleavage of the NH2-terminal octapeptide of Bothrops asper myotoxic lysine-49 phospholipase A2 reduces its membrane-destabilizing effect. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;312:336–339. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soares AM, et al. Structural and functional characterization of BnSP-7, a Lys49 myotoxic phospholipase A(2) homologue from Bothrops neuwiedi pauloensis venom. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;378:201–209. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J-H, Kerrison N, Chothia C, Teichmann SA. Divergence of interdomain geometry in two-domain proteins. Struct. Lond. Engl. 2006;1993(14):935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Girdlestone C, Hayward S. The DynDom3D Webserver for the Analysis of Domain Movements in Multimeric Proteins. J. Comput. Biol. 2015;23:21–26. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2015.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghorbani M, Mohammad-Rafiee F. Geometrical correlations in the nucleosomal DNA conformation and the role of the covalent bonds rigidity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1220–1230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floquet N, et al. Normal mode analysis as a prerequisite for drug design: application to matrix metalloproteinases inhibitors. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5130–5136. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Floquet N, Dedieu S, Martiny L, Dauchez M, Perahia D. Human thrombospondin’s (TSP-1) C-terminal domain opens to interact with the CD-47 receptor: a molecular modeling study. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;478:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchi-Salvador DP, Fernandes CAH, Silveira LB, Soares AM, Fontes MRM. Crystal structure of a phospholipase A(2) homolog complexed with p-bromophenacyl bromide reveals important structural changes associated with the inhibition of myotoxic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1794:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dos Santos JI, et al. Structural and functional studies of a bothropic myotoxin complexed to rosmarinic acid: new insights into Lys49-PLA2 inhibition. PloS One. 2011;6:e28521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes CAH, et al. Structural Basis for the Inhibition of a Phospholipase A2-Like Toxin by Caffeic and Aristolochic Acids. PloS One. 2015;10:e0133370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee WH, et al. Structural basis for low catalytic activity in Lys49 phospholipases A2–a hypothesis: the crystal structure of piratoxin II complexed to fatty acid. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2001;40:28–36. doi: 10.1021/bi0010470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami MT, et al. Inhibition of myotoxic activity of Bothrops asper myotoxin II by the anti-trypanosomal drug suramin. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;350:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delatorre P, et al. Crystal structure of Bn IV in complex with myristic acid: a Lys49 myotoxic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops neuwiedi venom. Biochimie. 2011;93:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe L, Soares AM, Ward RJ, Fontes MRM, Arni RK. Structural insights for fatty acid binding in a Lys49-phospholipase A2: crystal structure of myotoxin II from Bothrops moojeni complexed with stearic acid. Biochimie. 2005;87:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salvador GHM, et al. Structural and functional evidence for membrane docking and disruption sites on phospholipase A2-like proteins revealed by complexation with the inhibitor suramin. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2015;71:2066–2078. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715014443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chovancova E, et al. CAVER 3.0: a tool for the analysis of transport pathways in dynamic protein structures. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14(33–38):27–28. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diebel, J. Representing Attitude: Euler Angles, Unit Quaternions, and Rotation Vectors (2006).

- 48.Janota A, Šimák V, Nemec D, Hrbček J. Improving the precision and speed of Euler angles computation from low-cost rotation sensor data. Sensors. 2015;15:7016–7039. doi: 10.3390/s150307016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabsch W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A. 1976;32:922–923. doi: 10.1107/S0567739476001873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brooks BR, et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Best RB, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Floquet N, et al. Conformational Equilibrium of CDK/Cyclin Complexes by Molecular Dynamics with Excited Normal Modes. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1179–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.