Abstract

Changing trends in the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general population over time are thought to be the main driving force behind the declining gastric cancer mortality in Japan. However, whether the prevalence of H. pylori infection itself shows a birth-cohort pattern needs to be corroborated. We performed a systematic review of studies that reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection among Japanese individuals. Meta-regression was conducted in the framework of a generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) to account for heterogeneity in the prevalence of H. pylori infection as a function of birth year. The prevalence of H. pylori infection confirmed a clear birth cohort pattern: the predicted prevalence (%, 95% CI) was 60.9 (56.3–65.4), 65.9 (63.9–67.9), 67.4 (66.0–68.7), 64.1 (63.1–65.1), 59.1 (58.2–60.0), 49.1 (49.0–49.2), 34.9 (34.0–35.8), 24.6 (23.5–25.8), 15.6 (14.0–17.3), and 6.6 (4.8–8.9) among those who were born in the year 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively. The present study demonstrated a clear birth-cohort pattern of H. pylori infection in the Japanese population. The decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection in successive generations should be weighed in future gastric cancer control programs.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the human stomach, has been evolving with humans for tens of thousands of years. Substantial evidence supports a central role for H. pylori in the pathogenesis of upper gastrointestinal diseases, including peptic ulcer and non-cardia gastric cancer1. Unlike other developed countries, gastric cancer burden remains high in Japan, where it is the second leading cause of cancer deaths, accounting for annual deaths of approximately 50,0002. The reason for the lingering high gastric cancer incidence is manifold, but a high prevalence of H. pylori infection, reportedly as high as 80% among Japanese adults over 40 years old in a 1982 study by Asaka et al.3, appears to be the major contributor. Currently approximately 40% of the Japanese adult population are estimated to be infected with H. pylori 4.

Numerous epidemiological studies in Japan have reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection in various time points and age groups. These findings have shown that the prevalence of H. pylori infection increases with age5. This phenomenon is presumably due to a birth-cohort effect, because almost all H. pylori infection is acquired prior to the age of five, and because the environment during early childhood, such as water supply system, socioeconomic status, household living environment and hygiene habits, is closely associated with H. pylori infection6. Given these unique characteristics of H. pylori, the prevalence by birth year would be a valuable indicator that can reflect the time trends of H. pylori infection.

Previous studies conducted in the Western population have suggested that gastric cancer, gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer, the three main H. pylori-related diseases, exhibit a similar birth cohort pattern, with lower rates observed in subsequent generations7. A decline in the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general population is thought to be the major driving force behind this common pattern, since potent risk factors other than H. pylori have not been identified. Nevertheless, whether H. pylori prevalence itself shows a birth-cohort pattern remains to be corroborated. To our knowledge, there is no systematic review or meta-analysis consolidating the data on the prevalence of H. pylori infection from studies involving Japanese individuals. Therefore, we systematically reviewed the existing literature that presented estimates of the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Japanese population. We aimed to derive a robust prevalence estimate of H. pylori infection by birth year, and to explore the factors that may be associated with between-study variations in H. pylori infection in our meta-regression analysis. These findings will help to inform gastric cancer screening policies.

Methods

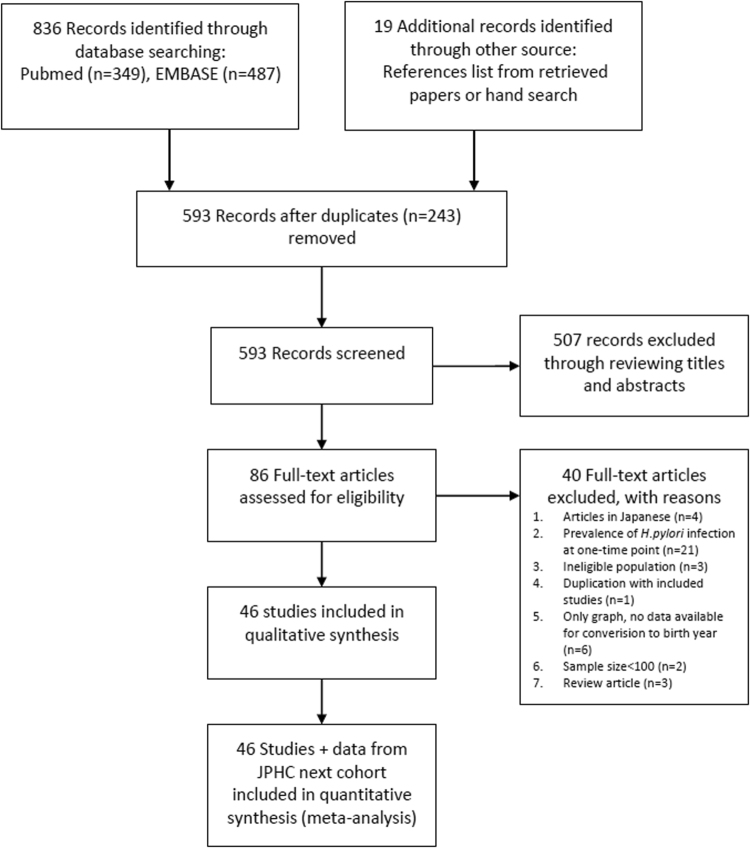

The PRISMA statement for preferred reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was used as a guide to conduct this study.

Data sources and Search strategy

Using the databases of PubMed and EMBASE, we performed a systematic review of the published studies on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Japanese population. The search on PubMed was limited to those studies that were conducted in human and to those that were published from inception to 30 June, 2016 with the following search terms: (“Helicobacter” [Mesh] OR “Helicobacter pylori” [title/abstract]) AND (“Prevalence” [Mesh] OR “prevalence” [title/abstract] OR “infection rate”) AND (“Japan” [Mesh] OR “Japan” [title/abstract] OR “Japanese” [title/abstract]). Similar strategies were applied in searching published studies in Embase. The search terms used in EMBASE were as follows: (“prevalence”/exp OR “prevalence”: ab, ti OR “infection rate”/exp OR “infection rate”: ab, ti) AND (“Japan”/exp OR “Japan”: ab, ti OR “Japanese”: ab, ti) AND (“helicobacter”/exp OR “helicobacter pylori”: ab, ti) AND (humans)/lim. To supplement electronic database searches, we also scrutinised the reference lists, and searched for unpublished data by contacting the head of known ongoing study projects in Japan.

Study selection

After excluding the duplicate literature from the two databases, we applied the following exclusion criteria: sample size less than 100; no information on time periods during which the study was conducted; review articles; studies published in languages other than English; reports on prevalence without stratifying subjects into different age groups; patients with symptomatic digestive diseases including peptic ulcer, gastric cancer and gastric MALT lymphoma. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were cross-sectional, case-control (only data in the control groups were extracted), or cohort studies that reported the prevalence and numbers of H. pylori infection in defined age groups (that is, age of those from whom samples were taken were specified or studies took place in population groups of a known age); or if they reported on the prevalence in any screening setting (such as community-based or hospital-based). We also included baseline data for H. pylori prevalence among 42,831 individuals who participated in the JPHC next cohort, the details of which can be accessed at the website (http://epi.ncc.go.jp/jphcnext/about/index.html). A PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram for study selection is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (LY and WC) independently searched and reviewed titles and abstracts identified by the literature search to select eligible studies. Citations identified by either reviewer were selected for full-text review. The same two authors then independently assessed the full-text articles, using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by the decision of a third author (KS). We extracted the prevalence by birth year from studies if such data were available in the original articles. And if such data were not available, we estimated birth year based on age groups and the year when the studies were conducted. The risk-of-bias assessment of all included studies was independently performed by two authors (LY and WC) using the Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool, in which 10 criteria are used to evaluate the methodological quality of studies that report prevalence data8. The results of risk-of-bias assessment were summarized in the Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Based on age groups reported in the original studies and the year when the studies were conducted, we converted them to birth years. For four studies which did not report the year of research, publication year was used instead to calculate the birth year9–12. For the analysis, we extracted data for the prevalence of H. pylori infection by birth year from each study: a total of 300 data points from 47 studies. In synthesizing the study results, we conducted a meta-regression to account for heterogeneity in the prevalence of H. pylori infection between studies using a logit link (logistic model).

The pre-specified explanatory variables included in the meta-regression were as follows: study ID, birth year, population source (community-based or clinical-based), diagnostic testing (serological test, or others; others include: urinary assay, salivary assay, stool antigen test, 13C-urea breath test and gastric biopsy), types of ELISA kits for measuring H. pylori positivity (antigen derived from domestic or foreign strains), and data collection period (prior to the year 2000, or later than 2000), with study ID as a random effect and other variables as fixed effects. Community samples came from nonclinical, population-based case-control or cross-sectional studies, and clinic-based samples included participants who were outpatients or underwent health check-ups in the clinical facilities. The year 2000 was chosen as a cutoff because the Japanese national health insurance scheme has covered H. pylori eradication for treating peptic ever since.

Since we have little prior justification for assuming a linear relationship between logit (the prevalence of H. pylori infection) and birth year, we used a penalized cubic spline to model the prevalence as a function of birth year in the framework of generalized additive mixed model (GAMM) implemented in the mgcv package in R13.In this analysis, we weighted observations by the inverse of the sum of the within-study variance and the residual between-study variance using the meta package14 in R. For all tests, P 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Subsequently, we performed sensitivity analyses stratified by study qualities (good or poor) which were defined according to the results of risk-of-bias diagnosis (studies that met higher or equal to 7 out of 10 criteria were defined as good quality, and the rest were defined as poor) or stratified by the year of research conducted (earlier or later than 2000), or by excluding children data points (n = 57) due to the concern that the accuracy of test kits in children has not been fully elucidated.

Results

The screening process is detailed in Fig. 1. Of the 86 full-text articles we reviewed, 46 met the inclusion criteria4,5,9–12,15–54. Collectively these citations included in the present study spanned birth years starting in 1908 and ending in 2003. Table 1 presents the characteristics for each study. Collectively, we successfully included 170,752 adults in the meta-regression analysis. Most of the studies were cross-sectional studies and were conducted in health screening, outpatient, or community settings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies addressing the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Japanese.

| Study ID | Reference | Data collection period | Participants | Setting | Adults or Children | Random Sampling | N | Mean Age [range] | Specimen type | Measurement kit | Antigen from domestic or foreign strains | Tested (n) | Positive (n) | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fukao et al.9 | NA | Healthy blood donors | Community | Children & adults | No | 1815 | [16–64] | Serum | ELISA kit (QUIDEL Corp., San Diego) | Foreign | 1815 | 949 | 53.3 |

| 2 | Replogle et al.39 | 1980–1993 | Patients screened for Hepatitis B virus at Tokyo University Hospital | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Children & adults | No | 1494 | [0–94] | Serum | NA | NA | 1207 | 470 | 38.9 |

| 3 | Kumagai et al.28 | 1986, 1994 | Participants of a cohort study | General population | Children & adults | No | 641, 549 | [6–80] | Serum | GAP-IgG test (Biomerica, Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 641, 549 | 510, 370 | 49.6, 67.4 |

| 4 | Youn et al.54 | 1993 | Patients without gastrointestinal symptoms | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Children & adults | No | 580 | [2–6], [7–19], [20-] | Serum | Immunoblot assay | NA | 100, 260, 100 | 20, 108, NA | 20, 40 > 75 |

| 5 | Kikuchi et al.26 | 1996 | Public service workers | Community | Adults | No | 5000 | [19–69] | Serum | Pilika Plate G Helicobacter, II (Biomerica Ltd., Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 4361 | 1330 | 30.5 |

| 6 | Fujisawa et al.21 | 1974, 1984, 1994 | Participants in a health screening program | Community | Children & adults | Yes | 1015 | Median 35.6, [0–89] | Serum | GAP-IgG test (Biomerica, Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 1015 | 426 | 42.0 |

| 7 | Yang et al.53 | 1996 | Employees of a manufacturing plant | Community | Adults | No | 598 | [20–59] | Serum | GAP-IgG test (Biomerica, Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 545 | 216 | 39.6 |

| 8 | Shibata et al.41 | 1997 | Residents | General population | Adults | No | 1207 | [30–64] | Serum | GAP-IgG, Biomerica, USA | Foreign | 636 | 310 | 48.7 |

| 9 | Ogihara et al.36 | 1989–1990 | Employees of small and medium-sized textile companies | Community | Adults | No | 9500 | [39–65 + ] | Serum | Pilika Plate G Helicobacter, II (Biomerica Ltd, Newport, USA) | Foreign | 8837 | 4268 | 48.3 |

| 10 | Yamagata et al.50 | 1988 | Participants of a cohort study | General population | Adults | No | 2742 | 57 in men, 59 in women, [40–80 + ] | Serum | HM-CAP (Enteric Products Inc, Westbury, NY) | Foreign | 2602 | 1721 | 66.1 |

| 11 | Kurosawa et al.29 | 1995–1996 | Elementary/junior high School students | Community | Children | No | 610 | 6 and 14 years | Saliva | HELISAI kit | Foreign | 610 | 83 | 13.6 |

| 12 | Okuda et al.38 | 1998–1999 | Asymptomatic children | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Children | No | 484 | [0–12] | Stool | Meridian Diagnositics, Cincinnati, USA | Foreign | 484 | 31 | 6.4 |

| 13 | Yamaji et al.51 | 1996–1997 | Individuals attending a health screening program | Community | Adults | No | 6489 | 48.1 [NA] | Serum | GAP-IgG test (Biomerica, Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 5732 | 2695 | 47.0 |

| 14 | Yamashita et al.52 | 1995–1996 | Healthy Children in an out-patient clinic | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Children | No | 336 | [0–19] | Serum | HEL-p-test; AMRAD, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Foreign | 336 | 59 | 17.5 |

| 15 | Shibata et al.5 | 1993 | Residents attending a health screening program | General population | Adults | No | 2347 | [30–79] | Serum | HM-CAP, EPI Inc., USA | Foreign | 954 | 703 | 73.7 |

| 16 | Fukuda et al.10 | 2003 | Asymptomatic children | General population | Children | No | 300 | 8 | Serum | HEL-p-test; AMRAD, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia | Foreign | 300 | 37 | 12.3 |

| 17 | Kato et al.11 | NA | Healthy Children | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Children | No | 454 | 6.1[0–15] | Serum | HM-CAP and PP-CAP, En-teric Products, New York, NY, USA | Foreign | 454 | 55 | 12.2 |

| 18 | Kato et al. 2004 | NA | Individuals with upper, gastrointestinal symptoms | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 6578 | [21–71 + ] | Serum | HM-CAP, Enteric Products, Incorporated, Stony Brook, NY, USA or a GAP lgG kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). | Foreign | 6578 | 3300 | 50.2 |

| 19 | Nobuta et al.12 | 1995–1996 | Asymptomatic individuals attending a health screening program | Community | Adults | No | 250, 209 | 40.7 (Niigata), 39.1 (Okinawa) | Serum | HM-CAP | NA | 250, 209 | 125, 88 | 50.0, 41.1 |

| 20 | Kikuchi et al.27 | 1988–1990 | Residents in various areas | General population | Adults | No | 635 | [40–79] | Serum | J-HM-CAP, Kyowa Medex Co. Ltd., Tokyo | Domestic | 633 | 443 | 70.0 |

| 21 | Kawade et al.24 | 1999–2001 | Patients with dyspepsia | Clinical- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 644 | 82.7 [65–107] | Serum | NA | NA | 644 | 337 | 52.3 |

| 22 | Shimatani et al.42 | 1997–2003 | University students attending a health check-up program | General population | Adults | No | 530 | 23.7 [NA] | Biopsy & serum | Rapid urease test (CLO test, Ballard Medical Products, Utah, USA), and HM-CAP Enteric Products, Westbury, NY, USA) | Foreign | 530 | 87 | 16.4 |

| 23 | Sasazuki et al.40 | 1990–1992 | Participants of a cohort study | General population | Adults | No | 511 | 57.4 [NA] | Serum | E Plate “Eiken” H. pylori, Antibody, Eiken Kagaku Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | Domestic | 511 | 383 | 74.9 |

| 24 | Fujimoto et al.20 | 1993, 2002 | Residents attending a health screening program | General population | Adults | No | 3819 | [20–70 + ] | Serum | ELISA (JHM-CAP, Kyowa Medix Co.,Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 3819 | 2116 | 55.4 |

| 25 | Shiotani et al.45 | 2005–2006 | University students | Community | Adults | Yes | 777 | 19.5 [18–25] | Serum | E Plate test (Eiken Kagaku) | Domestic | 777 | 114 | 14.7 |

| 26 | Naito et al.31 | 2002–2003 | Children from kindergarten or elementary school attending a health screening program | Community | Children | No | 452 | 4, 7, 10 | Urine | URINELISA H.pylori kit (Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo) | Domestic | 150, 150, 149, 149, 153, 153 | 8, 10, 7, 6, 6, 7 | 5.3, 6.7, 4.7, 4.0, 4.0, 4.6 |

| Study ID | Reference | Data collection period | Participants | Setting | Adults or Children | Random Sampling | N | Mean Age [range] | Specimen type | Measurement kit | Antigen from domestic or foreign strains | Tested (n) | Positive (n) | Prevalence (%) |

| 27 | Hirai et al.16 | 2007 | Asymptomatic adults | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 235 | [40–63] | Stool | TestMate Papid Pylori Antigen; BD Japan | Domestic | 186 | 75 | 40.3 |

| 28 | Mizuno et al.30 | 1987 | Residents | General population | Adults | No | 2589 | [35–75 + ] | Serum | Pilika Plate G Helicobacter, II (Biomerica Ltd., Newport Beach, CA) | Foreign | 2859 | 2147 | 75.1 |

| 29 | Nakajima et al.32 | 1998, 2005 | Individuals attending a health screening program | Community | Adults | No | 384 | [20–79] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 384 | 192 | 50.0 |

| 30 | Kawai et al.25 | 2003–2004 | Patients undergoing routine health check-up | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 418 | 39.2 [22–58] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 418 | 141 | 33.7 |

| 31 | Nakao et al.33 | 2001–2005 | All first-visit outpatients at Aichi Cancer Center | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 1465 | [20–79] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 1406 | 798 | 56.8 |

| 32 | Akamatsu et al.15 | 2007–2009 | Junior high school students | General population | Children | No | 1232 | [16–17] | Urine | RAPIRAN Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Tokyo, Japan | Domestic | 1224 | 64 | 5.2 |

| 33 | Toyoda et al.47 | 2004–2007 | Residents | General population | Adults | No | 1728 | 57.8 [30–89] | Serum | JHM-CAP, Kyowa, Medex Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan | Domestic | 1540 | 923 | 59.9 |

| 34 | Tamura et al.46 | 2008–2010 | Participants of a cohort study | General population | Adults | No | 5167 | [35–69] | Urine | Rapiran (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 5167 | 1881 | 36.4 |

| 35 | Shimoyama et al.43 | 2005 | Healthy adults attending a health screening program | General population | Adults | No | 1048 | [25–85] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 1048 | 638 | 60.9 |

| 36 | Urita et al.48 | 1999–2004 | Children attending a clinic | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Children | No | 838 | 12.4 [1–18] | Serum | NA | NA | 828 | 101 | 12.1 |

| 37 | Nakagawa et al.17 | 2005–2010 | Healthy adults attending a clinic | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 268 | [20–78] | UBT | NA | NA | 268 | 175 | 65.3 |

| 38 | Ueda et al.67 | 1997–2013 | Individuals attending a health screening program | Community | Adults | No | 14716 | NA [20 + ] | Serum/ur-ine/stool | E-plate (Eiken H.pylori antibody) | Domestic | 14716 | 5879 | 39.9 |

| 39 | Hirayama et al.4 | 2008 | Employees of a large company | Community | Adults | No | 21144 | NA [35–79] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemical Co.Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 21144 | 5822 | 27.5 |

| 40 | Okuda et al. 2014 | 2010–2011 | Participants of a population-based survey | General population | Children | No | 1299, 1909 | NA [0–8], NA [0–11] | Stool | TestMate Pylori Antigen EIA (Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd) | Domestic | 688, 835 | 13, 15 | 1.9, 1.8 |

| 41 | Shimoyama et al.44 | 2012 | Healthy adults attending a health survey | General population | Adults | No | 810 | [40–80] | Serum/st-ool | E-plate (Eiken Chemical Co.jLtd, Tokyo, Japan; Testmate EIA (Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Kyowa Medex) | Domestic | 505 | 224 | 44.4 |

| 42 | Watanabe et al.49 | 2005–2013 | All first-visit outpatients at Aichi Cancer Center | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 4698 | 60.5 [20–79] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken H.pylori antibody) | Domestic | 4285 | 1607 | 37.5 |

| 43 | Kamada et al.23 | 1975–1978, 1991–1994, 2010–2013 | Patients undergoing endoscopy for dyspepsia or gastric cancer screening | Clinic- or Hospital-based | Adults | No | 1381 | [18–70 + ] | Biopsy | Giemsa or Gimenez staining | NA | 289, 787, 305 | 216, 417, 107 | 74.7, 53.0, 35.1 |

| 44 | Akamatsu et al.18 | 2007–2013 | High school students | General population | Children | No | 3251 | [16–17] | Urine | RAPIRAN Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Tokyo, Japan | Domestic | 3251 | 136 | 4.2 |

| 45 | Nakayama et al. 201634 | 2011–2013 | Junior high school students | General population | Children | No | 681 | NA [12–15] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 454 | 14 | 3.1 |

| 46 | Charvat et al.19, JPHC Cohort II | 1993–1994 | Residents in various areas | General population | Adults | Yes | 21682 | [30–79] | Serum | E-plate (Eiken Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) | Domestic | 21682 | 14809 | 68.3 |

Abbreviation: NA, Not available; UBT, 13C-urea breath test.

Information on JPHC next cohort (Study ID = 45) is unpublished, details available upon request.

At first, full GAMM model with all of the aforementioned potential covariates included (Model 1) was estimated. To confirm whether Model 1 could best fit our data set, two more models were also estimated: one with covariates that showed significant effects in Model 1 (Model 2); the other one with only penalized cubic spline function of birth year and the random effect function of study ID (Model 3). Table 2 summarizes Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values for all the models. Comparison of AIC and BIC showed that the full model we proposed initially (Model 1) was the best one to fit the data (Table 2, Model 1, 1687.895 and 1880.004, respectively). Thus, Model 1 was believed to be appropriate to further predict the prevalence of H. pylori according to birth year in Japanese. The results of fitting for the best GAMM model (Model 1) are shown in Table 3. A borderline significant effect of diagnostic test (P = 0.08) is suggested, while non-significant effects of source of population, types of ELISA kit, or research year is identified.

Table 2.

Information for tested models.

| AIC | BIC | LogLik | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: | |||

| Logit(P) = s(birth year) + r(study ID) + f(source of population) + f(diagnostic test) + f(ELISA kits) + f(research year) | 1687.895 | 1880.004 | 792.0792 (df = 51.87) |

| Model 2: | |||

| Logit(P) = s(birth year) + r(study ID) + f(diagnostic test) | 1702.257 | 1889.008 | −800.7071 (df = 50.42) |

| Model 3: | |||

| Logit(P) = s(birth year) + r(study ID) | 1702.936 | 1890.291 | −800.8835 (df = 50.58) |

Abbreviations and definitions:

AIC: Akaike’s information criterion;

BIC: Bayesian information criterion;

LogLik: Log-likelihood;

P: prevalence;

s: penalized cubic spline;

r: random effect;

f: fixed effect;

df: degree of freedom.

Table 3.

Summary statistics from fitting meta-regression in the best model.

| Fixed effect parameter estimates: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Source of population | ||||

| Community-based | 1 | |||

| Clinical-based | 1.12 (0.73–1.52) | 0.56 | ||

| Diagnostic test | ||||

| Serology | 1 | |||

| Others* | 0.73 (0.37–1.08) | 0.08 | ||

| ELISA kits | ||||

| Domestic | 1 | |||

| Foreign | 1.15 (0.82–1.49) | 0.41 | ||

| Research year | ||||

| Earlier than 2000 | 1 | |||

| Later than 2000 | 0.89 (0.59–1.19) | 0.43 | ||

| Approximated significance of smooth terms: | ||||

| Estimated degree of freedom | Reference degree of freedom | Chi square | P | |

| Birth year | 7.3 | 8.1 | 4048 | <0.00001 |

| Random effect parameter estimates: | ||||

| Study ID | 37.2 | 41.0 | 1881 | <0.00001 |

*Others include: urinary assay, salivary assay, stool antigen test,13C-urea breath test, and gastric biopsy.

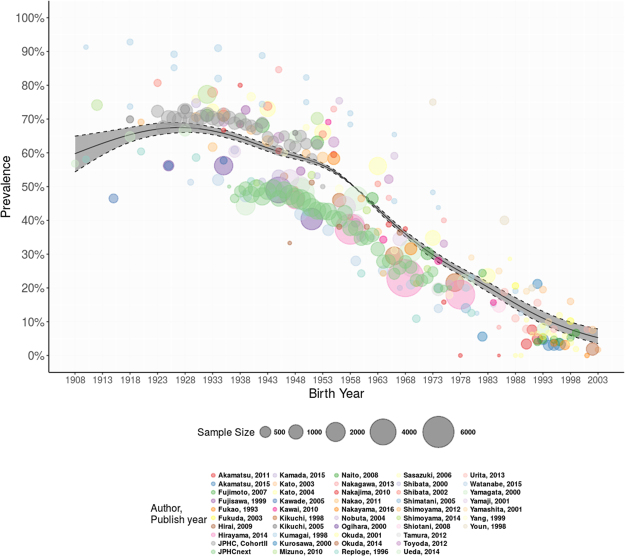

The results also demonstrate that the smoothing trend in birth year is significant (P 0.00001). This decreasing trend is illustrated in Fig. 2, which depicts the smoothed curve of the relationship between H. pylori infection prevalence and birth year. The spline function estimate of prevalence indicates that the prevalence of H. pylori ranged between 50% and 70% during the first four decades (1908–1948), after which the prevalence began to decrease steadily until 2003. To be specific, the predicted prevalence (%, 95% CI) was 60.9 (56.3–65.4), 65.9 (63.9–67.9), 67.4 (66.0–68.7), 64.1 (63.1–65.1), 59.1 (58.2–60.0), 49.1 (49.0–49.2), 34.9 (34.0–35.8), 24.6 (23.5–25.8), 15.6 (14.0–17.3), and 6.6 (4.8–8.9) among those who were born in the year 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively. The most recent cohorts, those born after 1998, appear to have a prevalence as low as less than 10% (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Multivariable adjusted prevalence of H. pylori infection in Japanese by birth year from year of 1908–2003.

Table 4.

Predicted prevalence of H.pylori infection in Japanese population by birth year from 1908 to 2003.

| Birth Year | Predicted Prevalence | 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | 59.7% | 54.3% | 64.9% |

| 1909 | 60.3% | 55.3% | 65.1% |

| 1910 | 60.9% | 56.3% | 65.4% |

| 1911 | 61.5% | 57.3% | 65.6% |

| 1912 | 62.1% | 58.2% | 65.8% |

| 1913 | 62.7% | 59.1% | 66.1% |

| 1914 | 63.2% | 60.0% | 66.3% |

| 1915 | 63.7% | 60.8% | 66.6% |

| 1916 | 64.2% | 61.5% | 66.8% |

| 1917 | 64.7% | 62.2% | 67.1% |

| 1918 | 65.1% | 62.8% | 67.4% |

| 1919 | 65.6% | 63.4% | 67.6% |

| 1920 | 65.9% | 63.9% | 67.9% |

| 1921 | 66.3% | 64.4% | 68.2% |

| 1922 | 66.6% | 64.7% | 68.4% |

| 1923 | 66.9% | 65.1% | 68.6% |

| 1924 | 67.1% | 65.3% | 68.8% |

| 1925 | 67.3% | 65.6% | 68.9% |

| 1926 | 67.4% | 65.7% | 69.0% |

| 1927 | 67.5% | 65.9% | 69.0% |

| 1928 | 67.5% | 66.0% | 69.0% |

| 1929 | 67.5% | 66.0% | 68.8% |

| 1930 | 67.4% | 66.0% | 68.7% |

| 1931 | 67.3% | 66.0% | 68.5% |

| 1932 | 67.1% | 65.9% | 68.3% |

| 1933 | 66.9% | 65.7% | 68.0% |

| 1934 | 66.6% | 65.5% | 67.7% |

| 1935 | 66.3% | 65.2% | 67.4% |

| 1936 | 65.9% | 64.8% | 67.0% |

| 1937 | 65.5% | 64.4% | 66.6% |

| 1938 | 65.1% | 64.0% | 66.1% |

| 1939 | 64.6% | 63.5% | 65.6% |

| 1940 | 64.1% | 63.1% | 65.1% |

| 1941 | 63.6% | 62.5% | 64.5% |

| 1942 | 63.0% | 62.0% | 64.0% |

| 1943 | 62.5% | 61.5% | 63.4% |

| 1944 | 61.9% | 60.9% | 62.9% |

| 1945 | 61.4% | 60.4% | 62.4% |

| 1946 | 60.8% | 59.8% | 61.9% |

| 1947 | 60.4% | 59.3% | 61.4% |

| 1948 | 59.9% | 58.9% | 60.9% |

| 1949 | 59.5% | 58.5% | 60.4% |

| 1950 | 59.1% | 58.2% | 60.0% |

| 1951 | 58.6% | 57.8% | 59.5% |

| 1952 | 57.2% | 56.5% | 57.8% |

| 1953 | 56.6% | 55.9% | 57.2% |

| 1954 | 55.8% | 55.2% | 56.4% |

| 1955 | 55.0% | 54.5% | 55.5% |

| 1956 | 54.0% | 53.6% | 54.5% |

| 1957 | 53.0% | 52.6% | 53.3% |

| 1958 | 51.8% | 51.5% | 52.0% |

| 1959 | 50.5% | 50.4% | 50.5% |

| 1960 | 49.1% | 49.0% | 49.2% |

| 1961 | 47.7% | 47.4% | 47.9% |

| 1962 | 46.2% | 45.8% | 46.6% |

| 1963 | 44.7% | 44.2% | 45.2% |

| 1964 | 43.2% | 42.6% | 43.8% |

| 1965 | 41.7% | 41.0% | 42.4% |

| 1966 | 40.3% | 39.6% | 41.0% |

| 1967 | 38.9% | 38.1% | 39.6% |

| 1968 | 37.5% | 36.7% | 38.3% |

| 1969 | 36.2% | 35.4% | 37.0% |

| 1970 | 34.9% | 34.0% | 35.8% |

| 1971 | 33.7% | 32.7% | 34.6% |

| 1972 | 32.5% | 31.4% | 33.5% |

| 1973 | 31.3% | 30.2% | 32.5% |

| 1974 | 30.3% | 29.1% | 31.4% |

| 1975 | 29.2% | 28.0% | 30.4% |

| 1976 | 28.2% | 27.1% | 29.4% |

| 1977 | 27.3% | 26.1% | 28.5% |

| 1978 | 26.4% | 25.2% | 27.5% |

| 1979 | 25.5% | 24.4% | 26.6% |

| 1980 | 24.6% | 23.5% | 25.8% |

| 1981 | 23.7% | 22.5% | 25.0% |

| 1982 | 22.9% | 21.6% | 24.1% |

| 1983 | 22.0% | 20.7% | 23.3% |

| 1984 | 21.1% | 19.7% | 22.5% |

| 1985 | 20.2% | 18.8% | 21.7% |

| 1986 | 19.3% | 17.8% | 20.8% |

| 1987 | 18.3% | 16.9% | 19.9% |

| 1988 | 17.4% | 15.9% | 19.0% |

| 1989 | 16.5% | 14.9% | 18.2% |

| 1990 | 15.6% | 14.0% | 17.3% |

| 1991 | 14.7% | 13.0% | 16.5% |

| 1992 | 13.8% | 12.1% | 15.7% |

| 1993 | 13.0% | 11.3% | 14.9% |

| 1994 | 12.2% | 10.4% | 14.1% |

| 1995 | 11.4% | 9.7% | 13.4% |

| 1996 | 10.7% | 8.9% | 12.7% |

| 1997 | 8.1% | 6.4% | 10.2% |

| 1998 | 7.6% | 5.8% | 9.8% |

| 1999 | 7.0% | 5.3% | 9.3% |

| 2000 | 6.6% | 4.8% | 8.9% |

| 2001 | 6.1% | 4.3% | 8.5% |

| 2002 | 5.7% | 3.9% | 8.2% |

| 2003 | 5.3% | 3.5% | 7.8% |

Further sensitivity analyses yielded essentially similar results, which were presented as figures in supplement materials (Supplementary Figures 1–5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to delineate the prevalence of H. pylori infection by birth year among the Japanese population based on systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Our findings suggest that H. pylori infection exhibits a birth cohort effect in Japan, with prevalence decreasing steadily in individuals born in successive years, from 59.1% in 1950 to 15.6% in 1990. In particular, the prevalence among children and adolescents is declining to very low levels, with the multivariable adjusted prevalence lower than 10% for individuals who were born after the year 1998. The multivariable adjusted prevalence of H. pylori infection seems to be lower among the older cohorts (subjects born during 1908–1918) compared with relatively younger subjects (birth year between 1923–1933) in Fig. 2. The possible reasons include potential development of atrophy or unstable estimates due to small sample sizes (the 95% CIs are much wider) among the older cohorts. Therefore, the uncertainty in prevalence estimates may exist and a cautious interpretation of results of the older cohorts is needed.

After evaluating various tools for assessing the quality of observational studies55, we adopted the Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool56, which was developed exclusively for epidemiological studies that reported on prevalence or incidence. It should be noted that even guided by such a tool, the risk-of-bias assessment is a subjective exercise. For this reason, two authors evaluated the risk-of-bias for each study independently, with disagreement resolved by either discussion or by a third author. Several concerns over methodological quality have arisen in the risk of bias assessment. First, concerning sampling strategy, most studies included in the current systematic review did not specify sampling strategy, which might have influenced the prevalence estimates owing to possible sampling bias. Second, because most studies did not explain the reasons for non-participation, it is not clear whether the study population was representative of the target population. If many individuals opted out of the survey because of illness or perceived good health, results may be an underestimate or overestimate of the real prevalence in the population. Third, serological antibody tests were used to define H. pylori infection in the majority of studies. A combination of at least two diagnostic methods is recommended to increase the validity of results, but only two studies adopted multiple tests to make a definitive diagnosis42,44. Fourth, controlling for two important confounders, H. pylori eradication and gastric atrophy, was not addressed in most studies. Taken together, the varied methodological approaches in the included studies and the above-mentioned limitations may have contributed to the wide variation in prevalence estimates for H. pylori infection, resulting in high between-study heterogeneity.

Based on various prevalence estimates for various age groups in included studies, a clear birth-cohort pattern emerged from our analysis. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was lower in sequential birth cohorts of Japanese born from 1908 to 2003. The results of our meta-analysis corroborated the birth-cohort pattern for H. pylori infection that was demonstrated in several included studies4,49, as well as a recent study exploring age, period, and cohort effects on gastric cancer mortality57. Moreover, our finding of a birth-cohort pattern for H. pylori infection in Japanese is similar to that documented in the United States and China, although the trajectory of decline across birth cohorts differed in these three countries58,59. The prevalence estimates observed for recent, younger birth cohorts in our study were comparable to those reported in the Western countries, but they were even lower when compared with those reported in China and South Korea60,61, two East Asian countries shouldering a similarly high gastric cancer burden. Whether the prevalence among young birth cohorts in Japan will continue to decline or it has already reached a nadir remains to be elucidated, although studies in Europe suggest that the prevalence has reached a nadir among children in recent years62.

Of covariates included in the meta-regression, the birth year explains much of the heterogeneity across studies. In other words, the birth year exerts a strong influence on H. pylori prevalence. Diagnostic testing (serological tests or others) might also contribute to between-study heterogeneity. Despite the sub-optimal performance characteristics of serological tests when compared with other diagnostic tests such as the urea breath test, the vast majority of included studies used serological tests to diagnose H. pylori infection because it is easy to perform and has good negative predictive value. In general, as the prevalence of an infection falls in a community, the accuracy of serological tests suffers, with an increase in the proportion of false-positive results. This also applies to H. pylori infection and this caveat should be considered when serological tests are used to diagnose H. pylori infection in a young population with a much-declined prevalence. Other potential explanations for false-positive serological test results include cross reactivity with other antigens, recent seroconversion and laboratory error. On the other hand, serological ELISA test might yield false-negative results in individuals who had serotiters in the range of 3–10 U/mL. Therefore, the observed prevalence reflected a mix of effects from both false-positive and false-negative results, making it difficult to quantify the true prevalence in the population. Because the vast majority of previous studies were limited by adopting only one diagnostic test, a combination of serological tests and other tests is necessary to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis. In addition, our meta-regression analysis indicated that differences in antigens used in ELISA did not significantly contribute to the between-study heterogeneity (odds ratio of foreign vs. domestic: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.82–1.49, p = 0.41). There was a concern that accuracy of kits made in Western countries may yield more intermediate results for Japanese people when compared with kits using antigens isolated from Japanese strains (for example, E-plate). However, according to our previous study63, when the recommended cut-off was used, there were no significant differences in diagnostic accuracy (95% CI) (domestic vs. imported: 92.5%, 90%-95% vs. 91.2%, 89%-94%, p 0.05), which is also in line with our current finding. With the predominant use of E-plate in recent years, the differences in prevalence stemming from antigen differences should not be a serious concern.

Our study has several limitations. First, including only English-language articles may lead to an over- or underestimation of the results. However, we only identified a very limited number of Japanese-language articles, which are mostly narrative reviews or conference reports. Nevertheless, no systematic bias from the use of language restriction (English-restriction) was noted in systematic review and meta-analysis64. In addition, another study65 found that English-language papers were of higher methodological quality than papers published in languages other than English. Thus, we believe that excluding studies published in Japanese language in the present study has little effect on summary estimates of prevalence of H. pylori infection. Second, because the modeling of prevalence estimates by birth cohorts across studies was used in the present meta-analysis, we were not able to assess traditional publication bias. Third, high-quality data for estimating the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general Japanese population are limited. In addition, regarding the covariates included in the present meta-regression analysis, the data were lacking on other H. pylori infection-related factors, such as socioeconomic status, living conditions, and personal hygiene habits. These factors may have also contributed to the declining trend of H. pylori infection prevalence in Japan. Fourth, H. pylori is characterized by its genetic diversity. Its virulence factors, such as CagA and VacA, vary geographically66. The effect of H. pylori genetic diversity on the changes in prevalence of H. pylori infection needs further study. Finally, although study showed that serological tests could be useful for children67, the accuracy of this kit in children has not yet been fully elucidated. Thus, studies that included or targeted children may generate uncertain estimates. However, excluding extracted children data points (n = 57) from the complete data set did not change the results materially (Supplementary Figure 5).

In conclusion, our study demonstrated a birth-cohort pattern of H. pylori infection among the Japanese population. Given the fact that the birth-cohort pattern of H. pylori shapes the trends of gastric cancer over time, our findings help to inform screening efforts aimed at prevention and early detection of gastric cancer in Japan. The decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection in successive generations should be weighed in gastric cancer screening programs.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere thanks to Youmei Wu (MSc Student, Department of Nutrition, School of Medicine Shanghai Jiaotong University) for assistance in literature retrieval using the Embase database. This study was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (B)(16H05244) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Author Contributions

Y.L., M.I. and C.W. originally conceived of this study, designed the study and completed the data set for analysis. C.W. and T.N. undertook the analysis. Y.L., C.W. and T.N. wrote the draft of the manuscript. S.K., M.I., N.S., and S.T. supervised the development of the manuscript. All authors provided critical input concerning the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15490-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterol. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue M. Changing epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:3–7. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asaka M, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterol. 1992;102:760–766. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90156-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueda J, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection by Birth Year and Geographic Area in Japan. Helicobacter. 2014;19:105–110. doi: 10.1111/hel.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibata K, et al. Relation of Helicobacter pylori infection and lifestyle to the risk of chronic atrophic gastritis: A cross-sectional study in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2002;12:105–111. doi: 10.2188/jea.12.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banatvala N, et al. The cohort effect and Helicobacter pylori. J. Infect. Dis. 1993;168:219–221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnenberg A. Review article: Historic changes of Helicobacter pylori-associated diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;38:329–342. doi: 10.1111/apt.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Prevalence Studies. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews.

- 9.Fukao A, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic atrophic gastritis among Japanese blood donors: A cross-sectional study. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4:307–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00051332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda Y, et al. Impact of CagA status on serum gastrin and pepsinogen I and II concentrations in Japanese children with Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Int. Med. Res. 2003;31:247–252. doi: 10.1177/147323000303100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato S, et al. Helicobacter pylori and TT virus prevalence in Japanese children. J. Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1126–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato M, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and the prevalence, site and histological type of gastric cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood, S. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. (CRC Press, 2006).

- 14.Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akamatsu T, et al. Introduction of an examination and treatment for helicobacter pylori infection in high school health screening. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1353–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirai I, et al. Assessment of east asian-type cagA-positive helicobacter pylori using stool specimens from asymptomatic healthy japanese individuals. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1149–1153. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.010934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa H, et al. Association between helicobacter pylori infection detected by the (13) c-urea breath test and low serum ferritin levels among japanese adults. Helicobacter. 2013;18:309–315. doi: 10.1111/hel.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akamatsu T, Okamura T, Iwaya Y, Suga T. Screening to Identify and Eradicate Helicobacter pylori Infection in Teenagers in Japan. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2015;44:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charvat H, et al. Prediction of the 10-year probability of gastric cancer occurrence in the Japanese population: The JPHC study cohort II. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138:320–331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujimoto Y, et al. Intrafamilial transmission of Helicobacter pylori among the population of endemic areas in Japan. Helicobacter. 2007;12:170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujisawa T, Kumagai T, Akamatsu T, Kiyosawa K, Matsunaga Y. Changes in seroepidemiological pattern of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus over the last 20 years in Japan. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2094–2099. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirayama Y, Kawai T, Otaki J, Kawakami K, Harada Y. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with healthy subjects in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;29(Suppl 4):16–19. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamada T, et al. Time Trends in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Atrophic Gastritis Over 40 Years in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:192–198. doi: 10.1111/hel.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawade M, et al. Prevalence of gastric cancer decreases with age in long-living elderly in Japan, possibly due to changes in Helicobacter pylori infection status. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;20:1333–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and reflux esophagitis in young and middle-aged Japanese subjects. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikuchi S, Kurosawa M, Sakiyama T. Helicobacter pylori risk associated with sibship size and family history of gastric diseases in Japanese adults. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1998;89:1109–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1998.tb00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikuchi S, et al. Serum pepsinogen values and Helicobacter pylori status among control subjects of a nested case-control study in the JACC study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15(Suppl 2):S126–133. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.S126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai T, et al. Acquisition versus loss of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: Results from an 8-year birth cohort study. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;178:717–721. doi: 10.1086/515376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurosawa M, Kikuchi S, Inaba Y, Ishibashi T, Kobayashi F. Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese children. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000;15:1382–1385. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizuno S, et al. Prescreening of a high-risk group for gastric cancer by serologically determined Helicobacter pylori infection and atrophic gastritis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010;55:3132–3137. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naito Y, et al. Changes in the presence of urine Helicobacter pylori antibody in Japanese children in three different age groups. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:291–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajima S, Nishiyama Y, Yamaoka M, Yasuoka T, Cho E. Changes in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal diseases in the past 17 years. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S99–S110. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakao M, et al. ABO genotype and the risk of gastric cancer, atrophic gastritis, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1665–1672. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama, Y., Lin, Y., Hongo, M., Hidaka, H. & Kikuchi, S. Helicobacter pylori infection and its related factors in junior high school students in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Helicobacter22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Nobuta A, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in two areas in Japan with different risks for gastric cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogihara A, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and smoking and drinking habits. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000;15:271–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okuda M, et al. Low prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: A population-based study in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20:133–138. doi: 10.1111/hel.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuda M, et al. Breast-feeding prevents Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:714–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200X.2001.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Replogle ML, et al. Increased risk of Helicobacter pylori associated with birth in wartime and post-war Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:210–214. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasazuki S, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection combined with CagA and pepsinogen status on gastric cancer development among Japanese men and women: A nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1341–1347. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibata K, et al. Green tea consumption and chronic atrophic gastritis: A cross-sectional study in a green tea production village. J Epidemiol. 2000;10:310–316. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimatani T, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, endoscopic gastric findings and dyspeptic symptoms among a young Japanese population born in the 1970s. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;20:1352–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimoyama T, et al. ABC screening for gastric cancer is not applicable in a Japanese population with high prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:331–334. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimoyama T, et al. Decrease of serum level of gastrin in healthy Japanese adults by the change of Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;29(Suppl 4):25–28. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiotani A, Miyanishi T, Kamada T, Haruma K. Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic diseases: Epidemiological study in Japanese university students. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;23:e29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamura T, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection measured with urinary antibody in an urban area of Japan, 2008-2010. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012;74:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toyoda K, et al. Serum pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori infection–a Japanese population study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:2117–2124. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urita Y, et al. Role of infected grandmothers in transmission of Helicobacter pylori to children in a Japanese rural town. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:394–398. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe M, et al. Declining trends in prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by birth-year in a Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1738–1743. doi: 10.1111/cas.12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamagata H, et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric cancer incidence in a general Japanese population: The Hisayama study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaji Y, et al. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: Analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut. 2001;49:335–340. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamashita Y, Fujisawa T, Kimura A, Kato H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: A serologic study of the Kyushu region in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2001;43:4–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2001.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang X, Nishibayashi H, Takeshita T, Morimoto K. Prevalence ofHelicobacter pylori infection in Japan: Relation to educational levels and hygienic conditions. Environ Health Prev Med. 1999;3:202–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02932259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Youn HS, et al. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori infection between Fukuoka, Japan and Chinju, Korea. Helicobacter. 1998;3:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shamliyan T, Kane RL, Dickinson S. A systematic review of tools used to assess the quality of observational studies that examine incidence or prevalence and risk factors for diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang C, Weber A, Graham DY. Age, period, and cohort effects on gastric cancer mortality. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015;60:514–523. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeh JM, et al. Contribution of H. pylori and smoking trends to US incidence of intestinal-type noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma: A microsimulation model. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeh JM, Goldie SJ, Kuntz KM, Ezzati M. Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and smoking on gastric cancer incidence in China: A population-level analysis of trends and projections. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:2021–2029. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim SH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: Nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagy, P., Johansson, S. & Molloy-Bland, M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China and the USA. Gut Pathogens8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Hoed CMden, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: Evidence for stabilized colonization rates in childhood. Helicobacter. 2011;16:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Obata Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological kits for helicobacter pylori infection with the same assay system but different antigens in a Japanese patient population. J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52:889–892. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morrison A, et al. The effect of english-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: A systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28:138–144. doi: 10.1017/S0266462312000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jüni P, Holenstein F, Sterne J, Bartlett C, Egger M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: Empirical study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:115–123. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ueda J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the e-plate serum antibody test kit in detecting helicobacter pylori infection among japanese children. J Epidemiol. 2014;24:47–51. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20130078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.