Highlights

-

•

Liver abscess and sepsis caused by Clostridium perfringens and Klebsiella oxytoca did not lead to death.

-

•

The LA is a severe disease in surgery with an overall mortality of 6–14%.

-

•

In approximately 7–32% of the cases Clostridium perfringens is responsible for a LA.

Keywords: Liver abscess, Sepsis, Clostridium perfringens, Klebsiella oxytoca, Gas gangrene

Abstract

Introduction

Clostridium (C) perfringens and Klebsiella (K) oxytoca are pathogenous human bacteria. Due to the production of several toxins C. perfringens is virulent by causing i.a. the necrotizing fasciitis, gas gangrene and hepatic abscess. K. oxytoca mostly causes infections of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract.

Presentation of case

We are presenting the case of a male patient at the age of 64, who suffered from nausea and progressive pain in the right upper abdomen. A computer tomography of the abdomen revealed a 7 × 5,6 cm sized entrapped air in liver segment VII. Later the patient developed a multiorgan failure. We then performed an explorative laparotomy. Intraoperatively it became clear that the liver was destructed presenting an open liver abscess (LA) cavity of segment VII. The gallbladder was found inflamed. We successfully conducted the consistent debridement of segment VII and removed the gallbladder. Microbiological examination isolated C. perfringens and K. oxytoca. The patient survived undergoing antimicrobial and multimodal sepsis therapy.

Discussion

The LA is a severe disease in surgery. In literature an overall mortality of 6–14% is described. Mostly bacterial infections of the biliary tract and the gallbladder are responsible for a LA. Abscesses with sepsis caused by both, C. perfringens and K. oxytoca, are highly perilous but rarely described in literature.

Conclusion

When diagnosing an LA caused by C. perfringens an immediate surgical debridement and antimicrobial treatment is mandatory for the patient’s survival.

1. Introduction

C. perfringens is a gram-positive spore-forming and rod-shaped anaerobic bacillus tolerating up to 3% O2 [1]. Belonging to the family of Clostridiaceae, it was first described by Andrewes and Klein in the 1890s. This bacterium is grows rapidly, showing a doubling rate of 7 min [2]. C. perfringens can be found everywhere in nature and is a component of the human intestinal and genital tract. Its virulence depends on the toxin production. The main toxin is the phospholipase C (α toxin). It damages the structural integrity of the cell membrane by splitting lecithin of the cell membrane into phosphocholine and diglyceride. This leads to hemolysis [1]. Furthermore the phospholipase C initiates platelet aggregation and ischemia due to microvascular occlusion by activating the platelet glycoprotein receptor IIB and IIIA [3]. The virulence factors β-, ε- and t-toxin are acting on the vascular endothelium and causing a capillary leak [1]. By inoculating of clostridial spores into necrotic tissue C. perfringens causes a necrotizing fasciitis, gas gangrene, hepatic abscess, emphysematous cholecystitis, emphysematous gastritis as well as a emphysematous cystitis and necrotizing enterocolitis [3]. C. perfringens can be responsible for food poisoning [4].

K. oxytoca is a gram-negative aerobic. Though but facultatively anaerobic, non spore-forming, non-motile bacterium and belongs to the family of enterobacteriaceae. Klebsiella species can be found everywhere in the environment. It was first isolated by Flugge in 1886 [5]. By direct and indirect contact of contained persons and objects K. oxytoca causes infections of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract with a consecutive sepsis [6]. Due to the synthesis of Beta-lactamase this bacterium has the potential of being resistant to penicillin and ampicillin. Also resistances of Klebsiella strains against colistin and carbapenems have been found [7], [8].

Some authors postulate that K. oxytoca is responsible for up to 8% of the cases of acute pneumonia [6]. Especially immunocompromised patients suffer fatal infections caused by these bacteria.

The work in this case has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [9].

2. Presentation of case

Caucasian male patient, 65 years of age, was referred to our hospital. For approximately 24 h he had been suffering from pain in the right shoulder, the right upper abdomen, nausea and vomiting. The day before he had consumed alcoholic drinks, but denied an alcoholic abuse strictly. The medical history includes hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus type II, arterial hypertonia, a chronic obstructive pulmonary and coronary heart disease. Furthermore he underwent a Billroth-II-resection due to stomach ulcer disease 30 years ago. During the clinical examination the patient showed a positive murphy sign. Laboratory test revealed increased concentrations of the C-reactive protein, leucocytes, procalcitonin and liver enzymes such as bilirubin, transaminases and gammaGT. The abdominal ultrasound and computer tomography detected a 7 × 5,6 cm sized entrapped air in the liver segment VII, air in the bile duct system, an abscess formation in the right liver lobe and an inflamed gallbladder with a three-layer wall (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The puncture of the abscess was successfully conducted. Moreover we performed an oesophagogastroduodenoscopy including an endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. In spite of several attempts the papilla vateri could not be intubated because of a subdermal emphysema. While treated in the intensive care unit, the patient subsequently developed a sepsis failure with a respiratory insufficiency and a renal failure. A long term ventilation via tracheostomy and a temporary conducted dialysis was mandatory. After presenting the patient to surgery an interdisciplinary consensus decided to perform an explorative laparotomy, with the aim to drain the abscess as a major point in treatment of anerobic gas-producing bacterized abscess. Intraoperative findings revealed a liver that was moth-damage-like-destructed and an opened abscess cavity of the liver segment VII. The abscess formation was connected to the right pleura space and was treated by placing a pleura drainage. Approximately 4 l of bloody ascites had to be withdrawn by suction. We removed the inflamed gallbladder and conducted a debridement of the liver segment VII (Fig. 3). The microbiological examination of the removed gallbladder and liver tissue isolated Klebsiella oxytoca and Clostridium perfringens. Klebsiella oxytoca could only be cultivated in the blood sample. Additionally to the surgical treatment, including two scheduled laparotomies, the patient received antibiogramm suitable antibiotics and intensive care therapy. Fortunately after four weeks the patient was discharged without any residual symptoms.

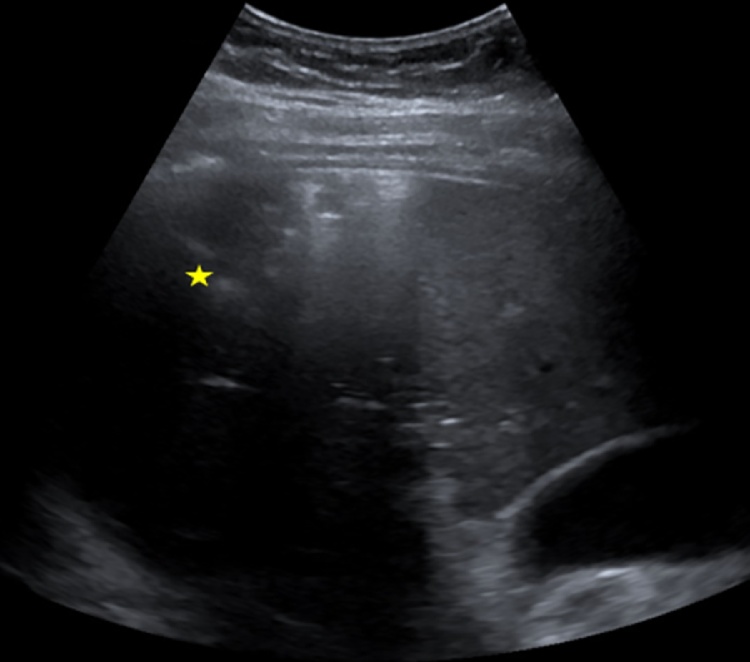

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound imaging of the liver. A 7 × 6 cm sized lesion surrounded by air in the right lobe of the liver became evident (marked by the yellow star).

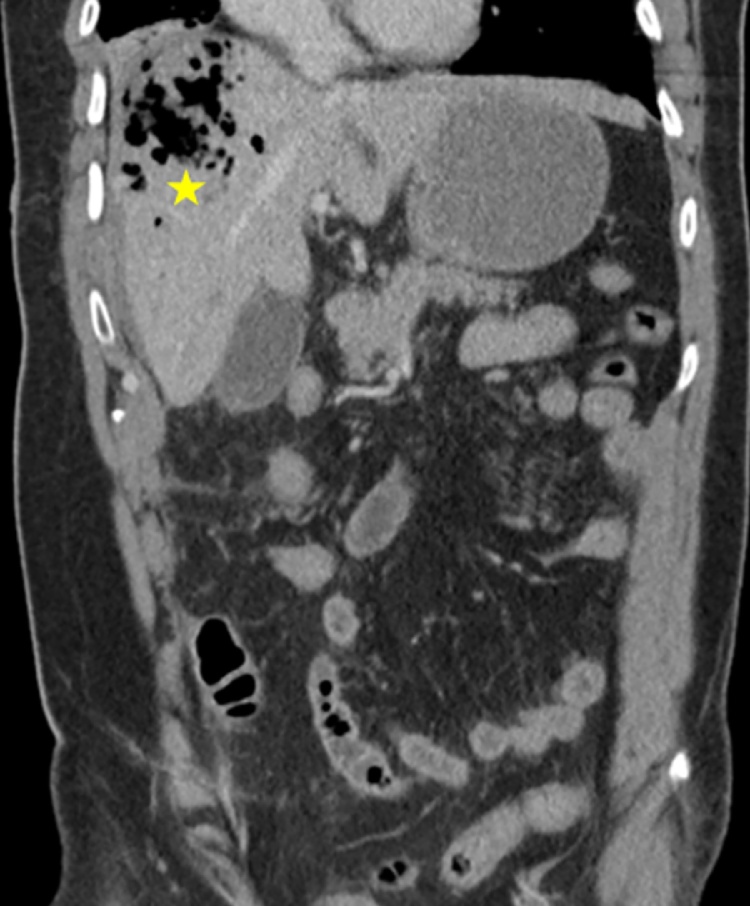

Fig. 2.

Computer tomography of the abdomen. The right hepatic lobe shows a 7 × 6 cm sized area of low attenuation containing mostly air (marked by the yellow star).

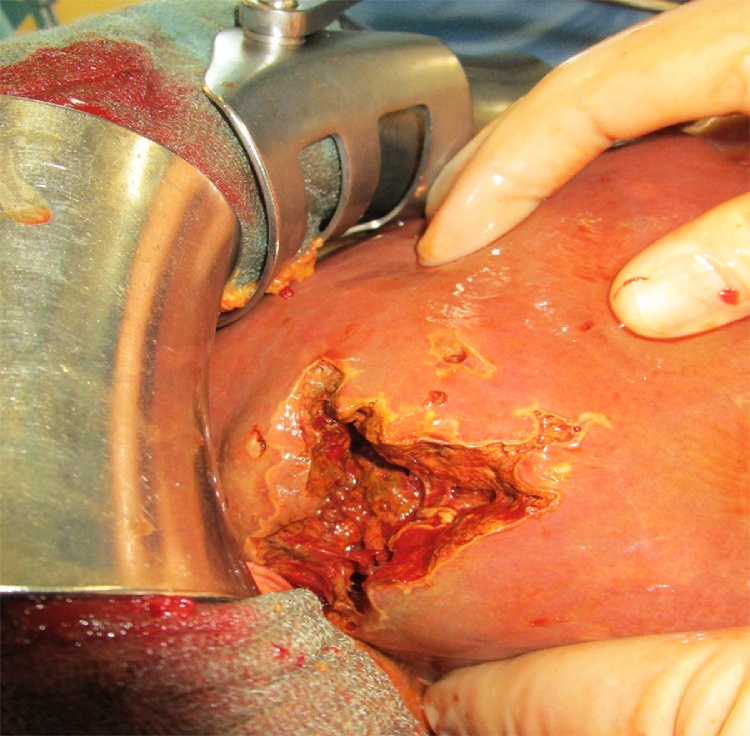

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative imaging of an opened abscess cavity in the liver segment VII.

3. Discussion

The LA is a severe disease in surgery with an overall mortality of 6–14% [10]. Hansen et al. performed a 10-year population-based retrospective clinical of LAs reaching 9% of the Danish population. They identified an LA incidence of 11 in 1,000,000. Most times infections of the biliary tract and the gallbladder just like in the case report at hand are responsible for LAs [11]. Chen et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of 72 patients, who suffered from a LA. Alcoholism, diabetes mellitus and bile stones were the main underlying diseases [12].

The LA is caused by different organisms. The most common pathogenes are bacteria – mostly Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and K. pneumoniae. In literature cases of LAs caused by C. perfringens, K. oxytoca, Lactobacillus, Fusobacterium, Salmonella enteritidis et typhi and Citrobacter koseri were described [11]. Performing a computer tomography (CT) and ultrasound images of the abdomen is described as being a sufficient approach for diagnosing a LA [13]. The major symptoms are fever and pain of the right upper abdomen with an emphysema [12]. The therapy has to be initiated immediately and includes antibiotic treatment, CT- or ultrasound-guided draining and consistent surgical debridement of the abscess with abdominal lavage [10].

In our case we diagnosed and treated a gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess caused by C. perfringens and K. oxytoca.

So far only two cases of LA with microbiological detection of K. oxytoca were reported. In both publications the patients were elderly and possibly suffering from an imbalanced diabetes type 2. The therapy of the LA by Saad et al. consisted of antibiotics and surgical draining, whereas Roca et al. successfully treated their patient only with ciprofloxacin [14], [15].

Several case reports of LAs caused by C. perfringens were published. In approximately 7–32% of the cases this bacterium is responsible for a LA [12]. After a liver transplantation clostridial infections along with sepsis and LA occur in approximately 2,5% of cases. For instance Jantsch et al. diagnosed a septicemia with C. perfringens by ultrasound detection of portal venous gas 24 h after a liver transplantation [13]. Moreover Eigneberger et al. published a casuistry of a LA due to C. perfringens septicemia 9 years after a liver transplantation [16]. This may lead to the assumption that mmunosuppression does play a certain role in the etiology of LAs followed by sepsis. Moreover it is well known in literature that diabetes increases the risk of developing and dying from an infectious disease [17], [18]. Therefore it is thinkable that the diabetes type II, our patient suffers from, may leaded to this severe infection with C. perfringens and K. oxytoca.

The therapy of a LA caused by C. perfringens and K. oxytoca consists of antibiotic treatment and debridement. In cases of infection with C. perfringens also an antitoxin treatment with the alpha toxin as a target is described. Accordingly Warn et al. demonstrated in an animal model that the application of Actoxumab© and Bezlotoxumab© – monoclonal antibodies against symptom-causing toxins TcdA and TcdB of C. difficile – prevents the appearance of toxin-dependent symptoms. Using antitoxin antibodies against Clostridium infections seems to take part in everyday clinical practice more and more though the evidence is low due to the lack of randomized clinical trials [19].

4. Conclusion

The LA is a serve disease in surgery with an overall mortality of 6–14%. Mostly infections of the biliary tract and the gallbladder are responsible for the LA. This is caused by different organisms.

The LA with septicemia caused by C. perfringens and especially by K. oxytoca are rarely described in literature though they are highly perilous. An immediate surgical debridement and antimicrobial treatment is mandatory for the patient’s survival.

When diagnosing a LA with entrapped air an infection of C. perfringens may be considered.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

Publication fee will be paid HELIOS Forschungsförderung of the Helios concern.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval necessary.

Consent

I have obtained written consent for publication of this case report from the patient and I can provide this should the Editor ask to see it.

Author’s contribution

Dr. med. Christoph Paasch (corresponding author): Contribution to the paper: author, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, writing the paper

Dr. med. Stefan Wilczek (co-author): Contribution to the paper: data analysis, treatment and examination of the patient (intensive care unit)

Prof. Dr. med. Martin W. Strik: Contribution to the paper: data analysis and interpretation, supervising writing of the paper

Guarantor

Dr. med. Christoph Paasch.

Contributor Information

Christoph Paasch, Email: christoph.paasch@helios-kliniken.de, chpaasch@web.de.

Stefan Wilczek, Email: Stefan.wilczek@helios-kliniken.de.

Martin W. Strik, Email: martin.strik@helios-kliniken.de.

References

- 1.Law S.T., Lee M.K. A middle-aged lady with a pyogenic liver abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. World J. Hepatol. 2012;4(8):252–255. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i8.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rives C., Chaudhari D., Swenson J., Reddy C., Young M. Clostridium perfringens liver abscess complicated by bacteremia. Endoscopy. 2015;47(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392867. UCTN:E457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz G.C., Boyer T., Renz J.F. Survival of Clostridium perfringens sepsis in a liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(11):1469–1472. doi: 10.1002/lt.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irikura D., Monma C., Suzuki Y., Nakama A., Kai A., Fukui-Miyazaki A., Horiguchi Y., Yoshinari T., Sugita-Konishi Y., Kamata Y. Identification and characterization of a new enterotoxin produced by Clostridium perfringens isolated from food poisoning outbreaks. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0138183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flügge C., Fox W. vol. 1. RCoPo; London: 1886. (Die Mikroorganismen: mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Ätiologie der Infektionskrankheiten). Verlag von F. C. W. Vogel, Leipzig. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power J.T., Calder M.A. Pathogenic significance of Klebsiella oxytoca in acute respiratory tract infection. Thorax. 1983;38(3):205–208. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li P., Wang M., Li X., Hu F., Yang M., Xie Y., Cao W., Xia X., Zheng R., Tian J., Zhang K., Chen F., Tang A. ST37 Klebsiella pneumoniae: development of carbapenem resistance in vivo during antimicrobial therapy in neonates. Future Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machuca I., Gutierrez-Gutierrez B., Gracia-Ahufinger I., Rivera Espinar F., Cano A., Guzman-Puche J., Perez-Nadales E., Natera C., Rodriguez M., Leon R., Caston J.J., Rodriguez-Lopez F., Rodriguez-Bano J., Torre-Cisneros J. Mortality associated with bacteremia due to colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with high-level meropenem resistance: importance of combination therapy without colistin and carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00406-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., Group S. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C.J., Pitt H.A., Lipsett P.A., Osterman F.A., Jr., Lillemoe K.D., Cameron J.L., Zuidema G.D. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. Changing trends over 42 years. Ann. Surg. 1996;223(5):600–607. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00016. discussion 607–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen P.S., Schonheyder H.C. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. A 10-year population-based retrospective study. APMIS. 1998;106(3):396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W., Chen C.H., Chiu K.L., Lai H.C., Liao K.F., Ho Y.J., Hsu W.H. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors of patients with pyogenic liver abscess requiring intensive care. Crit. Care Med. 2008;36(4):1184–1188. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a0a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jantsch H., Barton P., Fugger R., Lechner G., Graninger W., Waneck R., Winkler M. Sonographic demonstration of septicaemia with gas-forming organisms after liver transplantation. Clin. Radiol. 1991;43(6):397–399. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roca B., Ferrer D., Perez A.P. Liver abscess caused by Klebsiella oxytoca. Ann. Med. Int. 2005;22(7):355. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992005000700017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saad F., Ach K., Dallel Youssef N., Maarouf A., Chaieb Chadli M., Chaieb L. Hepatic abscess in diabetics, 2 case reports. Presse Med. 2004;33(2):98–100. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(04)98493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eigneberger B., Konigsrainer I., Kendziorra H., Riessen R. Fulminant liver failure due to Clostridium perfringens sepsis 9 years after liver transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2006;19(2):172–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah B.R., Hux J.E. Quantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(2):510–513. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearson-Stuttard J., Blundell S., Harris T., Cook D.G., Critchley J. Diabetes and infection: assessing the association with glycaemic control in population-based studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(2):148–158. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warn P., Thommes P., Sattar A., Corbett D., Flattery A., Zhang Z., Black T., Hernandez L.D., Therien A.G. Disease progression and resolution in rodent models of clostridium difficile infection and impact of antitoxin antibodies and vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6471–6482. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00974-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]