Highlights

-

•

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma was occurred at three sites simultaneously.

-

•

Independent ovarian cancer may coexist in case of corpus cancer.

-

•

Adenomyosis can be an origin for adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Adenomyosis, Endometriosis, Risk factors, Carcinogenesis

Abstract

Introduction

Although adenomyosis is a common disease, it is a relatively rare site for cancer origin. On the other hand, chocolate cysts have the potential to develop into cancer. We report a case of endometrioid adenocarcinoma occurred at three sites simultaneously; uterine endometrium, adenomyosis and ovarian endometriosis.

Presentation of case

A 51-year-old woman underwent total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy after a diagnosis of corpus cancer (endometrioid adenocarcinoma, G1) stage IA. However, cancer was also found independently at the site of adenomyosis and in endometrioid cysts after a detailed postoperative histological investigation. There has been no sign of recurrence at 12 months after six cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

Discussion

We reviewed cases of corpus cancer between January 2011 and December 2015 from our cancer database. Two hundred thirty-three patients with corpus cancer were identified. Ovarian malignancies were found in nine cases and six cases of them were histologically the same with the corpus cancer, but ovarian endometriosis was found in only two cases. On the other hand, adenomyosis was found histologically in 30 of these cases, but the case presented here was the only one diagnosed with cancer at a site of adenomyosis.

Conclusion

The mechanism by which malignancy develops in the normal endometrial tissue is not clear, but if endometrial cancer is found in the uterus, it could also be present in ectopic endometrial tissues such as sites of adenomyosis or chocolate cysts.

1. Introduction

Adenomyosis is a common disease found in 16%–34% cases in which the uterus is removed for the treatment of corpus cancer [1], [2]. Consistently, adenomyosis was found in 12.9% cases of corpus cancer in our cancer database. However, cancer arising from sites of adenomyosis is relatively rare [3]. Although ovarian cancer has been found in 0.7% of endometrial cysts [4], [5], other studies have reported that 17% of endometrioid adenocarcinoma cases and 24% of clear cell carcinoma cases have arisen from ovarian endometrial cysts [6], [7]. In line with the SCARE criteria, we report a case of endometrial adenocarcinoma with simultaneous cancer occurrences at a site of adenomyosis and within endometrial ovarian cysts [8]. Although carcinogenesis in an ectopic endometrial gland has not been described, in cases of endometrial cancer, the possibility of simultaneous cancer occurrence in an ectopic endometrial gland should be considered.

2. Case presentation

The patient was a 51-year-old, gravida 3, para 3 female. She was referred to our institute for further examination of abnormal vaginal spotting. An endometrial biopsy confirmed endometrioid adenocarcinoma, G1. She had no particular past medical history nor family history.

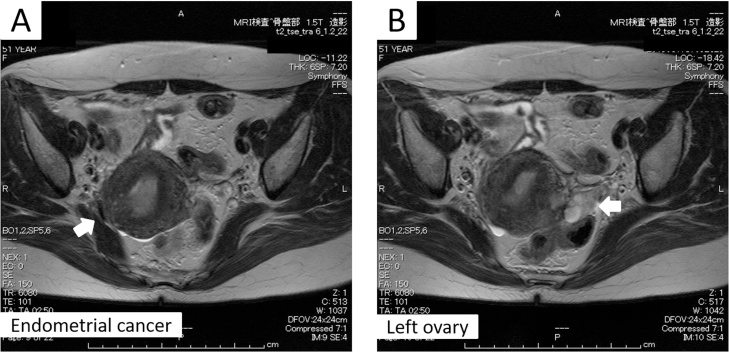

Laboratory results were unremarkable, except for slight anemia (Hb level: 9.9) and elevated tumor markers (CA125 level: 47.7 IU/mL and CA19-9 level: 280.0 IU/mL). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the presence of an irregularly shaped, intense T2, and enhanced mass in the intrauterine cavity, which partially obscured the junctional zone. The left ovary was multi-cystic, and chocolate cysts were suspected. The patient had moderate adenomyosis. Scant ascites was observed (Fig. 1A, B). Neither lymph node swelling nor suspicious metastasis to other organs was detected by computed tomography of the neck to the pelvis.

Fig. 1.

T2-weighted MRI.

The arrows indicate the corpus cancer tumor (A) and the multicystic left ovary (B).

Based on these findings, a preoperative diagnosis of corpus cancer stage I was made. Total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed uneventfully by two gynecologists, and the removed organs were sent for rapid intraoperative pathological analyses. Scant thin bloody ascites was also obtained and sent for cytological analysis. The uterus was enlarged to the size of a goose egg and adhered to the rectum and bilateral ovaries. The pouch of Douglas was closed. The observed adhesions appeared to be caused by endometriosis. The left ovary had confirmed multiple cysts that were filled with a chocolate-like liquid.

Macroscopically, a tumor was observed in the uterine cavity. Invasion of the mural layer could not be excluded but did not exceed more than half of it macroscopically. Cervical invasion was not detected. The results of rapid intraoperative pathological analyses confirmed stage IA corpus cancer; cytological analysis of the ascites was negative. A decision was made not to perform a lymphadenectomy.

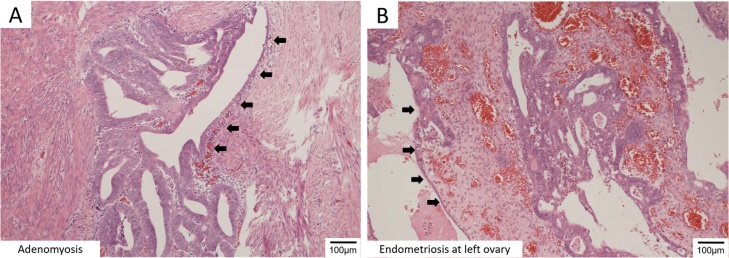

The final pathological diagnosis was surprising, because cancer was found at the sites of left ovarian endometriosis and adenomyosis. Non-cancerous tissue was observed to be gradually developing into a cancerous tissue. This is confirming that these cancers did not metastasize from the corpus cancer but independently arose at each site. (Fig. 2A, B)

Fig. 2.

Microscopic findings of Endometrioid adenocarcinoma at ectopic endometrial tissue.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma at a site of adenomyosis (A) and the left ovary (B). The arrows indicate a transitional area between the carcinoma and the normal tissue.

The standard treatment for ovarian cancer is pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, and appendectomy; total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are also commonly performed. We only performed total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which are insufficient for ovarian cancer.

There were two options for proper treatment of this patient postoperatively: one was additional surgery, including pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy, and appendectomy, followed by chemotherapy. The other option was chemotherapy alone without additional surgery. After discussions with the patient and her family, a decision was made for treatment with chemotherapy alone. Six cycles of combination therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin were completed. There has been no sign of recurrence at 12 months after the completion of chemotherapy.

3. Cancer database review

Cases of patients with corpus cancer who were registered in the cancer database at our hospital between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015 were reviewed. Two hundred thirty-three patients were identified. Adenomyosis was found histologically in 30 of these cases, but the case presented here was the only one diagnosed with cancer at a site of adenomyosis. Nine malignant ovarian tumors, including two borderline cases, were diagnosed among these cases of corpus cancer. Six cases of endometrioid adenocarcinoma were identified, but endometriosis was found in only two of these cases, including the present case. Other histological types of malignant ovarian tumors included mucinous adenocarcinoma, intestinal-type mucinous borderline tumor, and serous borderline adenofibroma. Standard surgery was performed in only one case, which had a definitive diagnosis before surgery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ovarian cancer present in cases of corpus cancer in our cancer database.

| Case No. | Age | Corpus cancer |

Ovarian cancer |

Chemotherapy (1st line) | Operation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | FIGO stage | Histology | FIGO stage | ||||

| 1a | 51 | EA, G1 | IB | EA, G1b | IA | TC | TAH + BSO |

| 2 | 51 | EA, G1 | IA | EA, G1 | IC(a) | TC | TAH + BSO |

| 3 | 53 | EA, G1 | IA | EA,G1 | IA | TC | TAH + BSO + PLN + PAN + POM |

| 4 | 44 | EA, G1 | IA | EA,G1b | IA | – | TAH + BSO |

| 5 | 45 | EA, G3 | IB | EA,G2 | IIIA | TC | TAH + BSO + POM |

| 6 | 74 | EA or MA | IIIA | EA or MA | IIC(b) | ddTC | TAH + BSO |

| 7 | 49 | EA, G1 | IA | MA | IC1 | – | TAH + BSO + POM + APE |

| 8 | 62 | EA, G1 | IA | mucinous borderline tumor intestinal type | IA | – | TAH + BSO |

| 9 | 48 | EA, G1 | IA | serous borderline adenofibroma | IC3 | – | TAH + BSO + POM |

EA: Endometrial adenocarcinoma, MA: Mucinous adenocarcinoma, TC: paclitaxel and carboplatin, ddTC: dose dense TC, TAH: Total abdominal hysterectomy, BSO: Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, PLN: Pelvic lymphadenectomy, PAN: Para-aortic lymphadenectomy, POM: Partial omentectomy, APE: Appendectomy

present patient.

ovarian endometriosis.

4. Discussion

Adenomyosis is a common disease but is a relatively rare site for cancer origin. Although there is no clear criterion to determine the stage of corpus cancer occurring at a site of adenomyosis, it is usually categorized as stage IB because cancer cells often exist deep in the muscular layer of the uterus [1], [9]. However, the prognosis for corpus cancer at a site of adenomyosis differs from that of typical corpus cancer stage IB. The prognosis for this type of corpus cancer is controversial [1], [2], [10], [11], [12]. Some studies reported that adenocarcinoma at a site of adenomyosis is characterized by a low histologic grade and excellent prognosis [2], [11]. On the other hand, other studies reported that the existence of adenomyosis could be a risk factor for advanced endometrial cancer [1], [12]. Treatment for this type of cancer should be considered carefully, with serious discussions between the gynecologists and pathologists involved.

It is known that sites of endometriosis can become malignant [4], [5]. Examples include clear cell carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma arising from chocolate cysts. Generally, large chocolate cysts found in patients over 40 years are at risk of becoming malignant [13], [14]. A rapid increase in tumor marker levels, like CA125, could be used to help identify ovarian cancer. In addition, imaging modalities like MRI could be useful for such a diagnosis. However, even if there were no changes in tumor marker levels and no suspicious areas identified on MRI, malignancy cannot be excluded. In cases of endometrial cancer, tumor markers cannot be used to rule out ovarian malignancy. Therefore, the possibility of ovarian cancer should be considered when chocolate cysts are present in cases of endometrial cancer.

For corpus cancer stage IA, the standard surgery is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. For ovarian cancer, it is pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, omentectomy and appendectomy in addition to hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Moreover, if corpus cancer was stage IB or more, lymphadenectomy was required. Therefore, accurate diagnosis is necessary as much as possible before performing operation. In this case, a pathological examination of the left ovary should have been performed during surgery. When ovaries are to be preserved, however, there is no evidence that a biopsy of an ovary with a normal appearance is typically performed to exclude malignancy. We hope that further research and discussion in these areas are ongoing.

5. Conclusion

The mechanism by which malignancy develops in the normal endometrial tissue is not clear, but if endometrial cancer is found in the uterus, it could also be present in ectopic endometrial tissues such as sites of adenomyosis or chocolate cysts. The fact that endometrioid adenocarcinoma was found at multiple sites in this case could be a piece of the puzzle for carcinogenesis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Lena Tashima is an attending doctor of this patient, collected the data and wrote this manuscript.

Dr Kensuke Hori contributed in clinical advices for patient treatment especially about adjuvant chemotherapy.

Dr Hitomi Ono participated in clinical management including assisting operation.

Dr Teruaki Nagano provided pathological diagnosis and prepared photos of microscopical findings.

Dr Shin-ichi Nakatsuka participated in the case discussion as a cancer board and gave precious opinions.

Dr Kimihiko Ito provided overall supervision and suggestion of the case report.

Guarantor

The guarantor for this case report is Dr Kimihiko Ito.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all members of department of obstetrics and gynecology and department of diagnostic pathology for helpful discussion.

References

- 1.Ismiil N., Rasty G., Ghorab Z. Adenomyosis involved by endometrial adenocarcinoma is a significant risk factor for deep myometrial invasion. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2007;11:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mittal K.R., Barwick K.W. Endometrial adenocarcinoma involving adenomyosis without true myometrial invasion is characterized by frequent preceding estrogen therapy, low histologic grades, and excellent prognosis. Gynecol. Oncol. 1993;49:197–201. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshiyama M., Suzuki A., Ozawa M. Adenocarcinomas arising from uterine adenomyosis: a report of four cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2002;21:239–245. doi: 10.1097/00004347-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishida M., Watanabe K., Sato N., Ichikawa Y. Malignant transformation of ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2000;50:18–25. doi: 10.1159/000052874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi H., Sumimoto K., Moniwa N. Risk of developing ovarian cancer among women with ovarian endometrioma: a cohort study in Shizuoka, Japan. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2007;17:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heaps J.M., Nieberg R.K., Berek J.S. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;75:1023–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce C.L., Templeman C., Rossing M.A. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE G.R. The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clement P.B., Young R.H. Endometrioid carcinoma of the uterine corpus: a review of its pathology with emphasis on recent advances and problematic aspects. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2002;9:145–184. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taneichi A., Fujiwara H., Takahashi Y. Influences of uterine adenomyosis on muscle invasion and prognosis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2014;24:1429–1433. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gizzo S., Patrelli T.S., Dall'asta A. Coexistence of adenomyosis and endometrioid endometrial cancer: role in surgical guidance and prognosis estimation. Oncol. Lett. 2016;11:1213–1219. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo K., Moeini A., Machida H. Tumor characteristics and survival outcome of endometrial cancer arising in adenomyosis: an exploratory analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2016;23:959–967. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4952-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodelon C., Pfeiffer R.M., Buys S.S., Black A., Sherman M.E. Analysis of serial ovarian volume measurements and incidence of ovarian cancer: implications for pathogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju262. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H. Ovarian cancer in endometriosis: epidemiology, natural history, and clinical diagnosis. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;14:378–382. doi: 10.1007/s10147-009-0931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]