Abstract

Background

Chronic coronary heart disease (CHD) and acute myocardial infarction are endemic conditions. In Germany, an estimated 900 000 cardiac catheterizations were performed in the year 2014, and a percutaneous intervention was carried out in 40% of these procedures. It would be desirable to lessen the number of invasive diagnostic procedures while preserving the reliability of diagnosis. In this article, we present the updated recommendations of the German National Care Guideline for Chronic CHD with regard to diagnostic evaluation.

Methods

Updated recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation of chronic CHD were developed on the basis of existing guidelines and a systematic literature review and approved by a formal consensus process.

Results

8–11% of patients with chest pain who present to a general practitioner and 20–25% of those who present to a cardiologist have chronic CHD. General practitioners should estimate the probability of CHD with the Marburg Heart Score. Specialists can use detailed tables for determining the pre-test probability of CHD; if this lies in the range of 15% to 85%, then non-invasive tests should be primarily used for evaluation and treatment planning. If the pre-test probability is less than 15%, other potential causes should be ruled out first. If it is over 85%, the presence of CHD should be presumed and treatment planning should be initiated. Coronary angiography is needed only if therapeutic implications are expected (revascularization). Psychosocial risk factors for the development and course of CHD and the patient’s quality of life should be regularly assessed as well.

Conclusion

Non-invasive testing and invasive coronary angiography should be used only if their findings are expected to have therapeutic implications. Psychosocial risk factors, the quality of life, and adherence to treatment are important components of these patients’ diagnostic evaluation and long-term care.

Chronic coronary heart disease (CHD) and myocardial infarction are widespread diseases (1). In Germany, 361 377 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) were performed in 2014 during in total 906 843 cardiac catheterizations (extrapolated), corresponding to a rate of therapeutic interventions of 40% (2). To reduce the burden on the health system, it is desirable to decrease invasive in favor of non-invasive diagnostic testing without jeopardizing diagnostic and therapeutic safety. Therefore, the current „Diagnosis“ chapter of the German National Disease Management Guideline (NVL, Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie) „Chronic CHD“ (3) recommends the use of rational diagnosis algorithms, based on validated clinical and non-invasive methods, prior to initiating invasive diagnostic procedures. In addition, the guideline makes recommendations on the different responsibilities on the primary care level (general practitioner, GP) and on the cardiology level in the differential diagnosis and further work-up of these patients.

The update of the NVL guideline contains several new elements, such as

the new validated „Marburg Heart Score“ to estimate the probability of CHD on the GP level,

current information about sensitivity and specificity of non-invasive tests,

updated recommendations on the relevance and significance of exercise ECG testing,

updated recommendations on the containment of the use of invasive coronary angiography,

updated recommendations on not using somatic testing in the follow-up of patients with asymptomatic CHD; and

for the first time recommendations on psychosocial aspects as an essential component of the diagnostic evaluation.

Methods

NVL guidelines are created based on the concepts of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N), the evaluation criteria for guidelines of the German Medical Association (BÄK, Bundesärztekammer) and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung) (e1), the guideline rules of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften) (e2), as well as the German Guideline Appraisal Instrument (DELBI, Deutsches Leitlinienbewertungsinstrument) (e3). The basic methodological approach is described in the general methods report (e4), the specific methodology in the guideline report for the NVL guideline (4). The creation of the 4th edition was organized by the German Agency for Quality in Medicine (ÄZQ, Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin) from 2014 to 2016. The guideline group had a multidisciplinary membership (ebox). Potential conflicts of interest of all parties involved were recorded in a structured fashion according to AWMF specifications and published in the guideline report (4).

eBOX. Editors and authors of NVL Chronic CHD, 4th edition.

-

Editors

German Medical Association (BÄK, Bundesärztekammer) Working group of the German Medical Associations

National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung)

Working group of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V.)

as well as

Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ, Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft)

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin e. V.)

German Society of Internal Medicine (DGIM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Innere Medizin e. V.)

German Cardiac Society (DGK, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie – Herz- und Kreislaufforschung e. V.)

German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation of Cardiovascular Disease (DGPR, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Prävention und Rehabilitation von Herz- und Kreislauferkrankungen e. V.)

German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (DGTHG, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie e. V.)

German Society of Radiology (DRG, Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft e. V.)

German College of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (DKPM, Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin)

German Society of Nuclear Medicine (DGN, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nuklearmedizin)

German Society for Rehabilitation Sciences (DGRW, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rehabilitationswissenschaften)

-

Authors of the 4th edition

Prof. Dr. med. Ulrich Laufs

Prof. Dr. med. Norbert Donner-Banzhoff

Dr. Jörg Haasenritter*

Prof. Dr. med. Karl Werdan

PD Dr. med. Claudius Jacobshagen

Prof. Dr. med. Eckart Fleck*

Prof. Dr. med. Ulrich Tebbe

Prof. Dr. med. Christian Hamm

Prof. Dr. med. Sigmund Silber*

Prof. Dr. med. Frank Bengel*

Prof. Dr. med. Oliver Lindner*

Prof. Dr. med. Bernhard Schwaab

Prof. Dr. med. Eike Hoberg

Prof. Dr. med. Volkmar Falk

Prof. Dr. med. Hans-Reinhard Zerkowski

Prof. Dr. med. Jochen Cremer*

PD Dr. med. Hilmar Dörge

PD Dr. med. Matthias Thielmann

Prof. Dr. med. Armin Welz

Prof. Dr. med. Christoph Herrmann-Lingen*

Prof. Dr. med. Christian Albus*

Prof. Dr. med. Jörg Barkhausen*

Prof. Dr. med. Matthias Gutberlet*

-

- Methodological support and coordination

Dr. Susanne Schorr

Dr. med. Carmen Khan, (ÄZQ)

Prof. Dr. med. Ina Kopp (AWMF)

* Members of the working group Diagnosis

Evidence base

For the update, guideline databases were searched for relevant source and reference guidelines. Applicable guidelines with the highest relevance and applicability to the German healthcare situation were selected and appraised using the DELBI instrument (4).

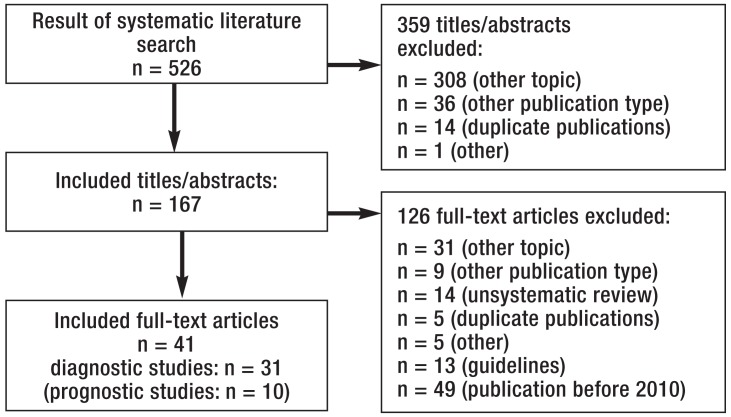

The Medline database (via Pubmed) and the Cochrane database were searched for systematic reviews comparing the use of non-invasive methods with the reference standard, coronary angiography, in patients with (suspected) chronic CHD which were published between January 2007 and May 2014 (etable 1). The hits identified were appraised in a two-step procedure (efigure). Included studies were assessed, extracted and graded according to the system of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (e5) (4).

eTable 1. Systematic literature search on the diagnostic value of imaging techniques.

| No. | Search query | Qty | ||

| Search strategy for Medline (www.pubmed.org) (27 May 2014) | ||||

| #44 | #9 OR #42 | 420 | ||

| #43 | #9 OR #41 | 462 | ||

| #42 | #41 NOT medline[sb] | 27 | ||

| #41 | #40 Filter: English, German, Publication Date from 2007/01/01 | 248 | ||

| #40 | #39 A #38 | 346 | ||

| #39 | systematic[sb] | 214 360 | ||

| #38 | #37 AND #21 | 19 008 | ||

| #37 | #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR 30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 | 93 696 | ||

| #36 | cardiac imaging*[TW] | 2492 | ||

| #35 | CMR [TW] | 3867 | ||

| #34 | adenosine AND (magnetic resonance [TW] OR MRI[TW]) | 6628 | ||

| #33 | Stress [TW] AND (magnetic resonance [TW] OR MRI[TW]) | 8656 | ||

| #32 | cardia*[TW] AND CT[TW] | 7510 | ||

| #31 | CTA[TW] | 5735 | ||

| #30 | comput*[TW] AND tomograph*[TW] AND coronary angiograph*[TW] | 9904 | ||

| #29 | CT[TW] AND coronary angiograph*[TW] | 3637 | ||

| #28 | MR angiograph*[TW] | 5042 | ||

| #27 | magneti*[TW] AND resonanc*[TW] AND angiograph*[TW] | 32 462 | ||

| #26 | myocard*[TW] AND perfusion imag*[TW] | 5254 | ||

| #25 | myocard*[TW] AND scintigraph*[TW] | 6276 | ||

| #24 | (single photon emission computed tomograph*[TW] OR SPECT[TW]) AND perfusio*[TW] | 7212 | ||

| #23 | (positron emission tomograph*[TW] OR PET[TW]) AND perfusio*[TW] | 3381 | ||

| #22 | stress[TW] AND echocardiograph*[TW] | 9608 | ||

| #21 | #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 | 252 739 | ||

| #20 | chest pain[TW] | 26 744 | ||

| #19 | (Ischemi*[TW] OR Ischaemi*[TW]) AND heart disease[TW] | 32 860 | ||

| #18 | Coronary heart diseas*[TW] OR CHD[TW] | 45 717 | ||

| #17 | Coronary artery diseas*[TW] OR CAD[TW] | 90 388 | ||

| #16 | Coronary ischemi*[TW] OR Coronary ischaemi*[TW] | 566 | ||

| #15 | Coronary stenos*[TW] | 11 709 | ||

| #14 | Non acute coronary disease | 14 075 | ||

| #13 | Coronary Arterioscleros*[TW] OR Coronary Atheroscleros*[TW] | 6867 | ||

| #12 | Myocardial ischemi*[TW] OR Myocardial ischaemi*[TW] | 49 940 | ||

| #11 | Angina pectoris[TW] | 38 481 | ||

| #10 | Stable Angina[TW] | 6445 | ||

| #9 | #8 Filter: English, German, Publication Date from 2007/01/01 | 393 | ||

| #8 | (#7 AND #6) | 664 | ||

| #7 | systematic[sb] | 214 360 | ||

| #6 | (#5 AND #4) | 58 993 | ||

| #5 | „Diagnostic Imaging“[Mesh] | 1 697 735 | ||

| #4 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3) | 243 334 | ||

| #3 | „Coronary Disease“[Mesh] | 179 998 | ||

| #2 | „Myocardial Ischemia“[Mesh:NoExp] | 31 768 | ||

| #1 | „Chest Pain“[Mesh] | 52 941 | ||

| © ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV und AWMF 2016 source: Guideline report of NVL Chronic CHD [4]) | ||||

| Recherchestrategie für die Datenbanken der Cochrane Library (27. Mai 2014) | ||||

| #37 | #7 OR 36 | 124 | ||

| #36 | (#35), from 2007 to 2014, in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews only), Other Reviews, Technology Assessments and Economic Evaluations | 123 | ||

| #35 | #34 AND #18 | 2043 | ||

| #34 | #19 OR #20 #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 | 20 982 | ||

| #33 | cardiac imaging*:ti,ab,kw | 1188 | ||

| #32 | CMR:ti,ab,kw | 15 921 | ||

| #31 | adenosine AND (magnetic resonance OR MRI):ti,ab,kw | 104 | ||

| #30 | Stress AND (magnetic resonance OR MRI):ti,ab,kw | 266 | ||

| #29 | cardi* AND CT:ti,ab,kw | 1205 | ||

| #28 | CTA:ti,ab,kw | 173 | ||

| #27 | compt* AND tomograph* AND coronary angiograph*:ti,ab,kw | 614 | ||

| #26 | CT AND coronary angiograph*:ti,ab,kw | 396 | ||

| #25 | MR aiograph*:ti,ab,kw | 257 | ||

| #24 | magneti* AND resonanc* AND angiograph*:ti,ab,kw | 682 | ||

| #23 | myocard* AND perfusion imag*:ti,ab,kw | 640 | ||

| #22 | myocard* AND scintigraph*:ti,ab,kw | 359 | ||

| #21 | (single photon emission computed tomograph* OR SPECT) AND perfusio*:ti,ab,kw | 594 | ||

| #20 | (positron emission tomograph* OR PET) AND perfusio*:ti,ab,kw | 169 | ||

| #19 | stre AND echocardiograph*:ti,ab,kw | 653 | ||

| #18 | #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 | 25 242 | ||

| #17 | (Ischemi* OR Ischaemi*) AND heart disease:ti,ab,kw | 4001 | ||

| #16 | Coronary heart diseas* OR CHD:ti,ab,kw | 9100 | ||

| #15 | Coronary artery diseas* OR CAD:ti,ab,kw | 10 249 | ||

| #14 | Coronary ischemi* OR Coronary ischaemi*:ti,ab,kw | 5499 | ||

| #13 | Coronary stenos*:ti,ab,kw | 2037 | ||

| #12 | Non acute coronary disease:ti,ab,kw | 620 | ||

| #11 | Coronary Arterioscleros* OR Coronary Atheroscleros*:ti,ab,kw | 1484 | ||

| #10 | Myocardial ischemi* OR Myocardial ischaemi*:ti,ab,kw | 6196 | ||

| #9 | Angina pectoris:ti,ab,kw | 5407 | ||

| #8 | Stable Angina:ti,ab,kw | 2555 | ||

| #7 | (#6), from 2007 to 2014, in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews only), Other Reviews, Technology Assessments and Economic Evaluations | 1 | ||

| #6 | (#5 AND #4) | 15 | ||

| #5 | „Diagnostic Imaging“:ti,ab,kw | 648 | ||

| #4 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3) | 10 518 | ||

| #3 | „Coronary Disease“:ti,ab,kw | 6897 | ||

| #2 | „Myocardial Ischemia“:ti,ab,kw | 2849 | ||

| #1 | „Chest Pain“:ti,ab,kw | 1508 | ||

| • Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3) • Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (63) • Health Technology Assessment Database (19) • NHS Economic Evaluation Database (39) | ||||

| Summary of the results from the databases | ||||

| Medline | Cochrane databases | Total | ||

| Aggregated evidence | ||||

| Hits | 462 | 124 | 586 | |

| Relevant hits | 462 | 64 | 526 | |

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: Guideline report of NVL Chronic CHD [4])

eFigure.

Flowchart of search on non-invasive techniques

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: Guideline report of NVL Chronic CHD [4])

A search for relevant guidelines on the use of invasive coronary angiography in the diagnosis of chronic CHD was performed in February 2015. These guidelines had to be not older than 5 years and published in German or English. The identified guidelines were appraised using the DELBI instrument and a guideline synopsis was created (4).

Pretest probability

Since no method of testing can achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, inaccuracies of the results obtained, both false negative and false positive, are to be expected. Taking into account the probability of the presence of a finding prior to test application (pretest probability) reduces the risk of an inaccurate result and thus increases the chance of a correct result with regard to the detection or exclusion of CHD. The assumptions are based on statistical analyses of data from many controlled studies and take age, sex, risks, symptoms, and test results into account.

Grades of recommendation and consensus-based adoption of recommendations

Grades of recommendation take into account the strength of the underlying evidence, ethical obligations, clinical relevance of the effect measures of the studies, the applicability of the study results to the target patient group, patient preferences, as well as practicability in everyday clinical use and within the structures of the German healthcare system. Two arrow symbols (↑↑) indicate a strong recommendation („is recommended/indicated“), one arrow symbol (↑) a weak recommendation („should be considered“), and two arrow symbols directed downwards (↓↓) a negative recommendation („is not recommended“). The consensus-based adoption of the recommendations was achieved using a Delphi technique and the draft version of the guideline was posted on the publically accessible website www.versorgungsleitlinien.de in November 2015 for comments.

Results

The DEGAM (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein– und Familienmedizin, German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians) guideline „Chest Pain“ was used as a source and reference guideline due to its high methodical quality (DELBI domain 3:0.86) (5). In addition, the ESC guidelines by Montalescot et al., rated lower with regard to methodology, (6) (DELBI domain 3: 0.43), and Perk et al. (7) (DELBI domain 3: 0.43) or their update by Piepoli et al. (8) were taken into consideration.

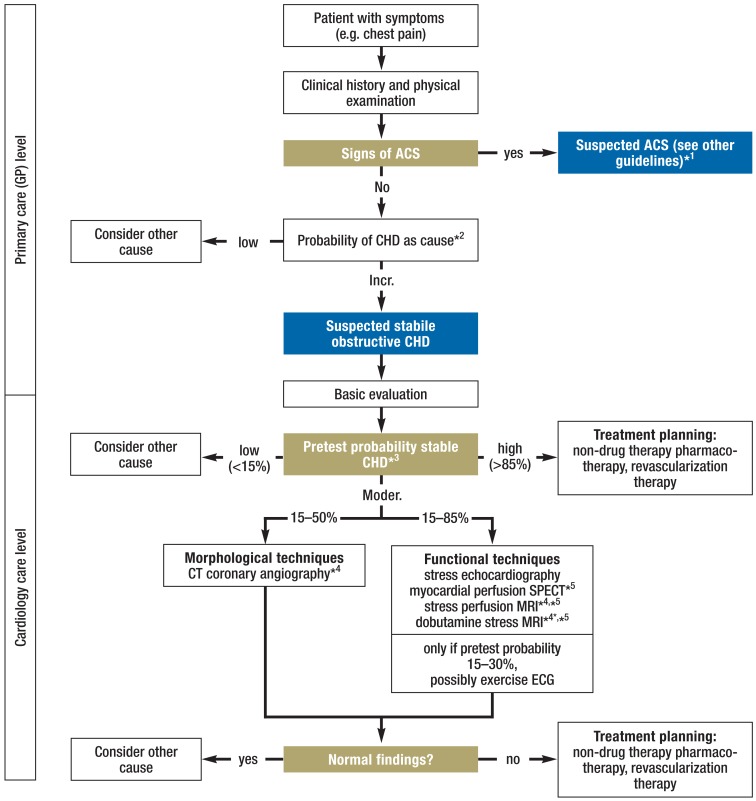

The diagnostic algorithm in patients with chronic CHD is depicted in the Figure. The basic assumption is that of patients with symptoms (angina pectoris) but no history of CHD who are assessed for potentially underlying obstructive CHD. The diagnostic process in patients with a history of CHD is basically similar.

Figure.

Diagnostic algorithm for suspected chronic CHD

*1 For treatment of acute coronary syndrome, please refer to other guidelines (e32– e37).

*2 Probability of CHD as cause (table 1)

*3 Pretest probability for obstructive CHD (table 2)

*4 Currently not covered by statutory health insurance; can be reimbursed through integrated care contracts

*5 In some medicines as off-label use.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CT, computed tomography; CHD, coronary heart disease; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

Differential diagnoses

On the level of GP care, chronic CHD is the cause of the pain in 8–11% of chest pain patients (9– 11). Relevant differential diagnoses include chest wall syndrome, psychogenic causes, respiratory tract infections, esophageal conditions, and acute coronary syndrome (9– 11). On the level of cardiology care, a cardiac etiology can be assumed in 20–25% of patients with unclear chest pain. The differential diagnosis includes, apart from myocardial infarction, valvular disease (especially aortic valve stenosis), aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and inflammatory myocardial and/or pericardial conditions.

History and physical examination

Important aspects of history taking are the exact recording of symptoms (location, development over time, pain quality), the assessment of physical stress tolerance and the identification of risk factors (12). Psychological, somatic and social information are recommended to be collected simultaneously right from the start when the clinical history is taken to prevent early fixation on somatic causes (↑↑, expert consensus).

On the primary care level (GPs), the probability that a patient with chest pain has an underlying obstructive CHD shall be estimated using the Marburg Heart Score (table 1) ([↑↑] [11, 13] according to [5]). A Marburg Heart Score = 2 points indicates an underlying obstructive CHD with a mean probability of <5%. When interpreting these score results, it is important to take the overall clinical picture into account (statement [11, 13] according to [5]).

Table 1. Marburg Heart Score to estimate probability of CHD and need for further diagnostic tests to be initiated on general practitioner care level—criteria and interpretation.

| Criterion | Point(s) |

| Sex and age (men ≥ 55 years, women ≥ 65 years) | 1 |

| Known vascular disease (CHD, PAD, stroke) | 1 |

| Exertional symptoms | 1 |

| Pain cannot be reproduced by palpation | 1 |

| Patient assumes pain is related to heart | 1 |

| For the score, total of points is calculated. Interpretation: • Score value 0–2: <2.5% (probability of obstructive CHD causing the chest pain) • Score value 3: approx. 17% (probability of obstructive CHD causing the chest pain) • Score value 4–5: approx. 50% (probability of obstructive CHD causing the chest pain) | |

| The interpretation also has to take the overall clinical picture into account. The mentioned probabilities of obstructive CHD are based on 2 validation studies (11, 13). | |

PAD, peripheral artery disease; CHD chronic coronary heart disease; © ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

On the cardiology care level, the data of the study by Genders et al. (14) are recommended to be used to determine pretest probability; the use of these data is also recommended by the ESC guideline (6) (table 2) (↑↑, expert consensus based on [6, 14]). The combined presence of the following features defines typical angina pectoris if 3 of the features are present and atypical angina pectoris if 2 are present, while 1 or none of the features defines non-anginal chest pain:

Table 2. Pretest probability of obstructive CHD in patients with stable chest pain to estimate the need for further diagnostic tests on the cardiology care level.

|

Typical angina pectoris |

Atypical angina pectoris |

Non-anginal chest pain |

||||

| Age* [years] | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 30–39 | 59% | 28% | 29% | 10% | 18% | 5% |

| 40–49 | 69% | 37% | 38% | 14% | 25% | 8% |

| 50–59 | 77% | 47% | 49% | 20% | 34% | 12% |

| 60–69 | 84% | 58% | 59% | 28% | 44% | 17% |

| 70–79 | 89% | 68% | 69% | 37% | 54% | 24% |

| >80 | 93% | 76% | 78% | 47% | 65% | 32% |

These data are based on the following definition of anginal symptoms (14) according to (15, 16): (A) squeezing pain located either retrosternally or in neck, shoulder, jaw or arm, (B) aggravated by physical exertion or emotional stress, (C) improved with rest and/or nitroglycerin within 5 minutes. The combined presence of the following features defines typical angina pectoris if 3 of the features are present and atypical angina pectoris if 2 are present, while 1 or none of the features defines non-cardiac chest pain.

* The calculated probabilities for the age groups represent the estimates for patients aged 35, 45, 55, 65, 75, and 85 years, respectively.

CHD, chronic coronary heart disease; © ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

squeezing pain experienced either retrosternally or in neck, shoulder, jaw or arm

aggravated by physical exercise or emotional stress

ameliorated by rest and/or nitroglycerin within 5 minutes ([14] according to [15, 16]).

Basic evaluation

Patients with suspected CHD due to their clinical history and findings are recommended to have a 12-lead resting ECG recorded (↑↑, expert consensus based on [5, 17]). However, systematic reviews have found that the informative value of resting ECGs in patients with stable chest pain or its usefulness to identify stable CHD is generally low (18, 19). Of special importance was the finding that a normal ECG alone does not reliably exclude an underlying CHD. Nevertheless, abnormal Q-waves as a sign of previous myocardial infarction as well as ST-segment and T-wave changes may indicate the presence of CHD (17). This is especially helpful if the patient has no known history of CHD.

In patients with suspected CHD due to their history and findings, resting echocardiography should be considered (↑, expert consensus). Transthoracic echocardiography is a useful tool to assess global and regional myocardial function and can thus contribute to the diagnosis of CHD in patients with regional wall motion abnormalities (hypokinesia, akinesia, dyskinesia) while taking into account the differential diagnosis (6, 20– 22).

Non-invasive tests

Exercise ECG is a frequently and widely used diagnostic tool to detect myocardial ischemia as the cause of the corresponding symptoms (12). However, with regard to its diagnostic value in comparison with other testing methods, its lack of diagnostic power for the diagnosis of CHD as the cause of e.g. chest pain is problematic. Assuming a pretest probability of 30–50%, based on clinical history and findings, the posttest probability in case of negative exercise ECG results is between 15 and 30% (own calculations based on Likelihood Ratio [LR] information in Mant et al. [19]). Given a pretest probability of >30%, posttest probability in case of a negative exercise ECG result is on average still higher than 15%; thus, further tests are still required (statement, expert consensus based on [19, 23]). Consequently, a negative finding can only be of help if pretest probability is <30%.

Altogether 31 meta-analyses on the diagnostic value of imaging techniques were identified; of these, the 9 most recent ones with the highest methodological quality were selected for stress echocardiography (e6), myocardial perfusion SPECT (e6– e9), stress-perfusion MRI (e6, e7), dobutamine stress MRI (e10), and CT coronary angiography (e9, e11– e13) to be used as the basis for the recommendations (etable 2). The results of the various analyses varied considerably. This was primarily due to differences in inclusion criteria, major clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the included primary studies, and rapid advances in the testing techniques.

eTable 2. Sensitivity and specificity of imaging techniques.

| Imaging technique | Sensitivity, [95% CI] | Specificity, [95% CI] |

| Stress echocardiography | 87%, [81; 91 ] (e6) | 89% [58; 98] (e6) |

| Myocardial perfusion SPECT | 70% [58; 79] (e7) 83% [73; 89] (e6) 88% [84; 91] (e8) 73% [59; 83] (e9) (compared with CT coronary angiography) |

76% [66; 83] (e7) 79% [66; 87] (e6) 79% [75; 83] (e8) 48% [31; 64] (e9) (compared with CT coronary angiography) |

| Stress perfusion MRI | 79% [72; 84] (e7) 91% [88; 93] (e6) |

75% [65; 83] (e7) 80% [76; 83] (e6) |

| Dobutamine stress MRI | 85 % [82; 90] (e10) | 86% [81; 91] (e10) |

| CT coronary angiography | 93 % [91; 95] (e11) between 88% and 100% (e12) 96 % [93; 98] (e13) (if only studies with the highest methodological quality are included) 99 % [96; 100] (e9) (compared with myocardial perfusion SPECT) |

86% [82; 89] (e11) between 64% and 92% (e12) 86% [83; 89] (e13) (if only studies with the highest methodological quality are included) 71% [60; 80] (e9) (compared with myocardial perfusion SPECT) |

[95% CI], 95% confidence interval, CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, Single-photon emission computed tomography © ÄZQ

BÄK, KBV and AWMF 2016 (source: Guideline report of NVL Chronic CHD [4])

Sensitivity and specificity considerations

In comparison with invasive coronary angiography, the sensitivity and specificity of most non-invasive techniques to detect obstructive CHD is about 85%. In patients with pretest probabilities of <15% and >85%, the tests have too many false positive or false negative results. This is illustrated by the following example:

In 1000 patients with 15% pretest probability (850 without CHD; 150 with CHD), a diagnostic test with 85% sensitivity and 85% specificity would generate in 850 patients correct results (850 × 0.85 + 150 × 0.85) and in 150 patients (850 × 0.15 + 150 × 0.15) incorrect results. However, if it is directly, i.e. without performing a test, assumed that all patients are healthy, this strategy is correct in 850 patients and incorrect in 150 patients. Thus, it has the same result as the diagnostic test. With decreasing pretest probability, the diagnostic test even performs worse. Only for pretest probabilities >15%, a diagnostic test with the criteria described above generates better results.

For pretest probabilities of 85%, a similar constellation is found. The assumption that all patients have the disease leads to results with an accuracy similar to that of a diagnostic test. If pretest probability increases further, the test performs progressively poorer in comparison with this assumption.

From these considerations it follows that in patients with low pretest probability (<15%) no diagnostic technique should be used to detect obstructive CHD. Instead, another cause of the symptoms should be considered (↑, expert consensus based on [e6–e13]). In patients with high pretest probability (>85%), obstructive CHD should be considered as the cause of the symptoms and treatment planning should be initiated (↑, expert consensus based on [e6–e13]). On patients with moderate pretest probability (15–85%), non-invasive techniques should be used for further work-up to rule out or confirm the suspected obstructive CHD (↑, [e6–e13]).

The non-invasive technique is recommended to be selected according to the pretest probability for obstructive CHD, the suitability of the patient for the respective test, test-related risks, locally available equipment, and local expertise (↑↑, expert consensus). Exercise ECG testing and CT coronary angiography are only recommended for certain pretest probabilities (figure). Morphological techniques, such as CT coronary angiography, can, in case of a negative result, very reliably rule out CHD; however, these techniques have limitations in the assessment of obstructive versus non-obstructive CHD; thus, they are most helpful if pretest probability is between 15 and 50%. Suitability criteria for the various non-invasive techniques are listed in eTable 3.

eTable 3. Suitability criteria for the various non-invasive techniques.

|

Stress echocardiography |

Myocardial perfusion SPECT |

Stress perfusion MRI |

Dobutamine stress MRI |

CT angiography | |

|

Target mechanism |

Wall motion | Perfusion, function | Perfusion, function | Wall motion | Coronary morphology |

| Target structure | whole left-ventricular myocardium | whole left-ventricular myocardium | left-ventricular myocardium | 3–5 representative slices | Coronary arteries |

|

Examination duration |

20–30 min | <10 min stress, (2 ×) 5–20 min camera (duration incl. pauses up to 4 h) | 20–30 min | 40–50 min | <5 min |

|

Stress testing methods |

ergometer, dobutamine, adenosine*1 |

ergometer, regadenoson, adenosine, rarely dobutamine*1 | Adenosine*1, regadenoson*1 | Dobutamine*1 | |

| Ionizing radiation | none (ultrasound) |

Gamma radiation | none | none | X-rays |

|

Limitation with pacemakers |

none | none | subject to pacemaker system | subject to pacemaker system | none |

| Disadvantages | possibly acoustic window restricted | attenuation artifacts (chest, diaphragm) possible | none | none | none |

| Intra- and inter-observer variability | Radiation exposure*2 |

Radiation exposure*2 |

|||

| Reimbursement | as a GKV service included in Cardiocomplex | GKV-covered service |

no GKV-covered service |

no GKV-covered service |

no GKV-covered service |

CT, computed tomography; GKV, statutory health insurance [gesetzliche Krankenkasse]; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography

*1 Off-label use of this medication. To justify this, the following criteria have to be observed: 1. proven efficacy, 2. favorable risk-benefit profile, 3. lack of alternatives—compassionate use. Thus, off-label use is only permissible in patients with serious disease where no treatment alternatives exist. Based on current scientific knowledge, there must be a reasonable chance of treatment success. In addition, there is a special obligation with regard to patient information. Patients are to be advised about the off-label use situation and potentially resulting liability issues. Joint decision-making is crucial.

*2 Radiation exposure depends on test protocol, imaging technique and technical equipment. Generally, the effective dose of the techniques used is in the lower dose range, i.e. below 10 mSv. Currently, examinations can be performed with radiation doses of about 1 mSv in certain cases. For comparison: The average effective dose in Germany is approx. 2–3 mSv/year. The Federal Office for Radiation Protection (BfS, Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz) has defined diagnostic reference values for the various imaging techniques which are updated on a regular basis (e38, e39) (see www.bfs.de).

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

In patients with known CHD and clinically suspected disease progression, functional non-invasive imaging techniques should preferentially be used for further work-up (↑, expert consensus). If a previous examination performed with one of these techniques is available, the same technique should be used again, whenever possible, to ensure the findings can be compared (↑, expert consensus).

Invasive coronary angiography

Altogether 9 guidelines making statements with regard to the use of coronary angiography for CHD diagnosis were identified and appraised using the DELBI tool (4). As basis for the recommendations (table 3), the best rated and most relevant guidelines were used (6, 24, 25). In the context of treatment planning, coronary angiography shall only be offered, if it can be expected that as a result of its findings the patient will undergo a revascularization procedure (table 3). As detailed in the Revascularization Therapy chapter of the NVL guideline Chronic CHD (3), patients should receive advice based on the patient information brochure „Suspected coronary heart disease: Do I need to undergo cardiac catheterization?“.

Table 3. Recommendations for coronary angiography.

| Recommendation | GoE | |

| Invasive coronary angiography is not recommended, based on individual decision by physician: • in case of low probability of obstructive CHD • in case of moderate probability of obstructive CHD and no signs of ischemia after non-invasive diagnostic evaluation • in case of high comorbidity where risk of coronary angiography is greater than benefit from confirmation of diagnosis and resulting treatment • in patients without symptomatic indication who, after advice based on the patient information brochure „Suspected coronary heart disease: Do I need to undergo cardiac catheterization?“, are not prepared to undergo CABG for prognostic indication; • after intervention (CABG or PCI) without renewed angina pectoris and without detection of ischemia in non-invasive diagnostic evaluation or without changes in findings in non-invasive imaging compared with status before intervention. | ↓↓ | Expert consensus |

| Patients with strong suspicion of obstructive CHD* after non-invasive diagnostic evaluation who, after advice based on the patient information brochure „Suspected coronary heart disease: Do I need to undergo cardiac catheterization?“, are prepared to undergo CABG for prognostic indication, invasive coronary angiography is recommended (see chapter Revascularization therapy of NVL Chronic CHD). | ↑↑ | (6, 24, 25) |

| Patients with strong suspicion of obstructive CHD after non-invasive diagnostic evaluation experiencing symptom persistence despite optimal conservative therapy (symptomatic indication) invasive coronary angiography is recommended (see chapter Revascularization Therapy of NVL chronic CHD [3]). | ↑↑ | (6, 24, 25) |

Two arrow symbols (↑↑) indicate a strong recommendation („is recommended“),

two arrow symbols directed downwards (↓↓) a negative recommendation („is not recommended“).

* Management of acute coronary syndrome is discussed in other guidelines (e32– e37).

GoE, grade of evidence (Strength of Recommendations and Quality of the Evidence); CHD, chronic coronary heart disease;

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

Psychosocial evaluation

The aspects discussed in the following are not related to differential diagnosis, but to support a comprehensive biopsychosocial simultaneous diagnosis. Low social status, lack of social support, job-related and family-related stress, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or certain personality patterns, especially hostility and the so-called Type-D pattern (habitual tendency to experience negative emotions in combination with social inhibition) can have a negative impact on development and course of CHD as well as the quality of life of the patient (7, 8, 26– 28). The best prognostic evidence is available for depressive disorder after acute coronary syndrome (29, e14). In addition, treatment options are available for depressed CHD patients which are effective in relieving symptoms of depression (e15). Thus, for the detection of a depressive disorder, a strong recommendation (↑↑, expert consensus based on [e14, e15, 29, 30]), for the detection of other relevant psychological disorders and psychosocial risk constellations a weak recommendation (↑, expert consensus based on [e16-e31, 31–33]) was issued. An overview of suitable medical history questions or questionnaires is provided in eTable 4. In case of positive screening for psychological problems/mental disorder, a clinical diagnosis with explicit exploration of all primary and secondary symptoms according to ICD-10 is recommended to be pursued (↑↑, expert consensus).

eTable 4. Overview of suitable questions and instruments for psychosocial evaluation.

| Risk factors | Screening questions for history taking | Standardized questionnaires |

| Mental disorders | ||

| Depression | During the last month, did you feel down? During the last month, did you lose interest and pleasure in life? |

Depression subscale of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

| Panic disorder | Have you been experiencing sudden attacks of anxiety and fear accompanied by symptoms such as palpitations, trembling, sweating, shortness of breath, fear of death, among others? | Panic items from PHQ-D |

|

Generalized anxiety disorder |

Do you feel nervous or tense? Do you often worry more than other people? Do you think you are constantly worrying and have lost control of it? | Anxiety subscale of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) or Patient Health Questionnaire (GAD-7) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | Do you suffer from intrusive, troublesome thoughts and memories of a severe event (images, nightmares, flashbacks)? (This event may also be a cardiac event or its treatment in some patients). | Impact of Event-Scale—revised (IES-R) |

| Other mental disorder | Do you suffer from another mental disorder? | |

| Psychosocial stress | ||

| Low socioeconomic status | Are you a manual worker or tradesperson? Is your highest education achievement a basic school qualification (or less)? | |

| Social isolation/lack of social support | Do you live alone? Do you miss one or more persons you can trust and rely on their help? | |

| Job-related stress | At work, do you often feel very challenged? Do you miss to be able to influence what type of work you do? Is the payment or acknowledgment you receive at work by far not enough for your efforts? Do you worry about your job or your career advances? | |

| Family-related stress | Do you have serious problems with your spouse or your family? | |

| Personality traits indicative of an unfavorable prognosis | ||

| Hostility or tendency to react angry | Do you often get upset over trifles? Do you often get upset about the habits of other people? | |

| Type-D personality pattern | In general, do you often fell anxious, irritable and depressed? Do you find it difficult to share your thoughts and feelings with strangers? | Type-D scale (DS14) |

© ZQ, BÄK, KBV und AWMF 2016 source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

Routine follow-up of patients with confirmed obstructive CHD

The GP is responsible for the regular long-term follow-up care of patients with chronic CHD. The corresponding recommendations (table 4) are based on expert consensus due to the lack of studies evaluating follow-up care.

Table 4. Recommendations for routine follow-up in patients with chronic CHD.

| Recommendation | GoE | |

| If patients with obstructive CHD have restricted LV function, left main coronary artery stenosis, multiple-vessel disease, proximal LAD stenosis, status post survived sudden cardiac death event, diabetes mellitus, or unsatisfactory intervention outcome, it further increases the risk of a cardiac event. In these patients, adequate intervals for regular follow-up examinations should be considered by cardiologists and general practitioners jointly. | ↑ | Expert consensus |

| In asymptomatic patients, except for thorough clinical history and control of cardiovascular risk factors, it is not recommended for follow-up care to include any special cardiac diagnostic tests (including exercise ECG, echocardiography) to confirm or exclude obstructive CHD. | ↓↓ | Expert consensus |

| Quality of life | ||

| Indicative assessment of health-related quality of life of patients in its physical, psychological and social aspects should be considered as part of the follow-up. In case of limitations in specific quality-of-life areas, somatic and psychosocial causes should be identified and, if required, steps for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment should be agreed with the patient. | ↑ | Expert consensus |

| Adherence | ||

| Regular assessment of adherence to medication and life style changes is recommended during follow-up. | ↑↑ | (35– 37) according to (7, 8) |

| Assessment of potential adherence barriers (e.g. concerns or misunderstandings, depression, cognitive impairments) and agreement of individual treatment adaptions (simplification of dosing regimen, external aids or remainder systems, among others) should be considered. | ↑ | (37) according to (7, 8) |

| In case of inadequate response to prescribed medications, medication adherence should be explored, potential barriers identified and steps to overcome these be agreed, prior to any treatment escalation should be considered. | ↑ | Expert consensus |

| In case of persistent non-adherence, further steps should be considered to overcome adherence barriers and to promote active adherence, if required with professional psychological or psychotherapeutic support, should be recommended. | ↑ | (37) according to (7, 8) |

One arrow symbol (↑) indicates a weak recommendation (“should be considered”), two arrow symbols (↑↑) indicate a strong recommendation

(„is recommended“), two arrow symbols directed downwards (↓↓) a negative recommendation („is not recommended“).

LV, left ventricle; LAD, left anterior descending artery; GoE, grade of evidence (Strength of Recommendations and Quality of the Evidence),

© ÄZQ, BÄK, KBV, and AWMF 2016 (source: NVL Chronic CHD [3])

Apart from a good prognosis, management of chronic CHD aims at achieving a high quality of life for the patient, another key parameter of treatment. For application in clinical practice, an indicative assessment of quality of life using the items of the EuroQoL (EQ-5D) sheet (34) is recommended. The recommendations on quality of life and treatment adherence (table 4) are based on the ESC guideline (7, 8) and a current position paper of the German Cardiac Society (26).

Key Messages.

The diagnosis of chronic CHD should be guided by clinically defined pretest probabilities. For this purpose, the Marburg Heart Score is available on the primary care (general practitioner) level. For the Cardiology care level, a table, comprising age, gender and the patient‘s specific symptoms, is recommended.

With pretest probabilities between 15 and 85%, non-invasive techniques are recommended. The selection of the technique should take into account the suitability of the patient for the respective test, test-related risks, locally available equipment, and local expertise.

Invasive coronary angiography is only recommended if consequences for treatment (revascularization therapy) can be expected.

Except for thorough history and control of cardiovascular risk factors, follow-up care of asymptomatic patients requires no special cardiac diagnostic tests.

Right from the start, psychosocial risk factors should be recorded and treated in a structured way, as it has been shown that depression can have a negative effect on quality of life and prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The group of authors would like to thank Dr. Susanne Schorr for the excellent methodological support and coordination during the preparation of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Frank Bengel, Prof. Dr. Matthias Gutberlet und Prof. Dr. Christoph Herrmann-Lingen for their very helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Lindner has received lecture fees from GE Healthcare, Casionpharm and Mediso.

Prof. Albus is receiving honoraria for an authorship related to the topic from Elsevier-Verlag, Deutscher Ärzteverlag and Schattauer-Verlag. He has received fees for scientific lectures from Daiichi-Sankyo, WebMD Germany, KelCON GmbH, PCO Tyrol Kongress, and MSD.

Prof. Barkhausen has received lecture fees from Bayer and Philips.

Prof. Silber, Prof. Fleck and Dr. Hasenritter declare no conflict of interest.

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD

References

- 1.Gosswald A, Schienkiewitz A, Nowossadeck E, Busch MA. Prävalenz von Herzinfarkt und koronarer Herzkrankheit bei Erwachsenen im Alter von 40 bis 79 Jahren in Deutschland Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:650–655. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsche Herzstiftung. Deutsche Herzstiftung. Frankfurt/Main: 2016. Deutscher Herzbericht 2016. 28. Sektorenübergreifende Versorgungsanalyse zur Kardiologie und Herzchirurgie in Deutschland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Chronische KHK - Langfassung, 4. Auflage. Version 1. http://doi.org/ 10.6101/AZQ/000267 (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Chronische KHK - Leitlinienreport, 4. Auflage. Version 1. http://doi.org/ 10.6101/AZQ/000264 (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haasenritter J, Bösner S, Klug J, Ledig T, Donner-Banzhoff N Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM) Omikron Publ. Düsseldorf: 2011. Brustschmerz. DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the Management of Stable Coronary Artery Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012): The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts).Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–1701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdon F, Herzig L, Burnand B, et al. Chest pain in daily practice: occurrence, causes and management. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138:340–347. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosner S, Becker A, Haasenritter J, et al. Chest pain in primary care: epidemiology and pre-work-up probabilities. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15:141–146. doi: 10.3109/13814780903329528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haasenritter J, Bosner S, Vaucher P, et al. Ruling out coronary heart disease in primary care: external validation of a clinical prediction rule. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e415–e421. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper A, Calvert N, Skinner J, et al. National Clinical Guideline Centre for Acute and Chronic Conditions. London: 2010. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosner S, Haasenritter J, Becker A, et al. Ruling out coronary artery disease in primary care: development and validation of a simple prediction rule. CMAJ. 2010;182:1295–1300. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, et al. A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1316–1330. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond GA, Staniloff HM, Forrester JS, Pollock BH, Swan HJ. Computer-assisted diagnosis in the noninvasive evaluation of patients with suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;1:444–455. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Cardiology Foundation, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) et al. ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1475–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skinner JS, Smeeth L, Kendall JM, Adams PC, Timmis A Chest Pain Guideline Development Group NICE guidance. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. Heart. 2010;96:974–978. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.190066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun AA, McGee SR. Bedside diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2004;117:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mant J, McManus RJ, Oakes RA, et al. Systematic review and modelling of the investigation of acute and chronic chest pain presenting in primary care. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii1–iii58. doi: 10.3310/hta8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheitlin MD, Alpert JS, Armstrong WF, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Developed in colloboration with the American Society of Echocardiography. Circulation. 1997;95:1686–1744. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography) J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography (ASE), American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC) et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1126–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:477–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2014;130:1749–1767. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) NICE. London: 2011. Management of stable angina. Last modified: December 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladwig KH, Lederbogen F, Albus C, et al. Positionspapier zur Bedeutung psychosozialer Faktoren in der Kardiologie Update 2013. Kardiologe. 2013;7:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gohlke H, Albus C, Bönner G, et al. CME Zertifizierte Fortbildung Empfehlungen der Projektgruppe Prävention der DGK zur risikoadjustierten Prävention von Herz- und Kreislauferkrankungen. Teil 4: Thrombozytenfunktionshemmer, Hormonersatztherapie, Verhaltensänderung und psychosoziale Risikofaktoren. Kardiologe. 2013;7:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albus C, Ladwig KH, Herrmann-Lingen C. Psychokardiologie: praxisrelevante Erkenntnisse und Handlungsempfehlungen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2014;139:596–601. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: systematic review and recommendations: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1350–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN), Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression - Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Version 5. http://doi.org/10.6101/AZQ/000364 (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandelow B, Wiltink J, Alpers GW, et al. S3-Leitlinie Behandlung von Angststörungen Kurzversion. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/051-028k_S3_Angstst%C3%B6rungen_2014-05_1.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deutschsprachige Gesellschaft für Psychotraumatologie (DeGPT), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychotherapeutische Medizin und ärztliche Psychotherapie (DGPM), Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin (DKPM), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie (DGPs), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychoanalyse, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Tiefenpsychologie (DGPT), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) S3-Leitlinie. Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung. ICD 10: F 43.1. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/051-010l_S3_Posttraumatische_Belastungsstoerung_2012-03.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde (DGPPN) Behandlungsleitlinie Schizophrenie. Darmstadt: Steinkopff. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 34.EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119:3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:540–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV) Beurteilungskriterien für Leitlinien in der medizinischen Versorgung - Beschlüsse der Vorstände der Bundesärztekammer und Kassenärztlicher Bundesvereinigung, Juni 1997. Dtsch Arztebl. 1997;94:A2154–A-2155. [Google Scholar]

- E2.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Zuckschwerdt. München: 2012. Das AWMF-Regelwerk Leitlinien. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin (ÄZQ), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Deutsches Instrument zur methodischen Leitlinien-Bewertung (DELBI). Fassung 2005/2006 + Domäne 8. www.leitlinien.de/mdb/edocs/pdf/literatur/delbi-fassung-2005-2006-domaene-8-2008.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E4.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Nationales Programm für VersorgungsLeitlinien. Methoden-Report 4th edition. www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/methodik/mr-aufl-4-version-1.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E5.Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ. 2001;323:334–336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.de Jong MC, Genders TS, van Geuns RJ, Moelker A, Hunink MG. Diagnostic performance of stress myocardial perfusion imaging for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1881–1895. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2434-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Chen L, Wang X, Bao J, Geng C, Xia Y, Wang J. Direct comparison of cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for detection of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088402. e88402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Parker MW, Iskandar A, Limone B, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac positron emission tomography versus single photon emission computed tomography for coronary artery disease: a bivariate meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:700–707. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.978270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Nielsen LH, Ortner N, Norgaard BL, Achenbach S, Leipsic J, Abdulla J. The diagnostic accuracy and outcomes after coronary computed tomography angiography vs conventional functional testing in patients with stable angina pectoris: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:961–971. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Nandalur KR, Dwamena BA, Choudhri AF, Nandalur MR, Carlos RC. Diagnostic performance of stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1343–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Li S, Ni Q, Wu H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 320-slice computed tomography angiography for detection of coronary artery stenosis: meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2699–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Powell H, Cosson P. Comparison of 64-slice computed tomography angiography and coronary angiography for the detection and assessment of coronary artery disease in patients with angina: a systematic review. Radiogr. 2013;19:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- E13.Gorenoi V, Schonermark MP, Hagen A. CT coronary angiography vs invasive coronary angiography in CHD. GMS Health Technol Assess. 2012;8 doi: 10.3205/hta000100. Doc02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2763–2774. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Rutledge T, Redwine LS, Linke SE, Mills PJ. A meta-analysis of mental health treatments and cardiac rehabilitation for improving clinical outcomes and depression among patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:335–349. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318291d798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Tonne C, Schwartz J, Mittleman M, Melly S, Suh H, Goldberg R. Long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction is lower in more deprived neighborhoods. Circulation. 2005;111:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.496174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA. 2010;303:1159–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Alter DA, Franklin B, Ko DT, et al. Socioeconomic status, functional recovery, and long-term mortality among patients surviving acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065130. e65130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:229–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Richardson S, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Krupka D, Davidson KW, Edmondson D. Meta-analysis of perceived stress and its association with incident coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1711–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Overtime work and incident coronary heart disease: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1737–1744. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Eller NH, Netterstrom B, Gyntelberg F, et al. Work-related psychosocial factors and the development of ischemic heart disease: a systematic review. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:83–97. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318198c8e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Orth-Gomer K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Schneiderman N, Mittleman MA. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. JAMA. 2000;284:3008–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Denollet J. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Roest AM, Martens EJ, Denollet J, de Jonge P. Prognostic association of anxiety post myocardial infarction with mortality and new cardiac events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:563–569. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dbff97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Burg MM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review. Am Heart J. 2013;166:806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Edmondson D, Richardson S, Falzon L, Davidson KW, Mills MA, Neria Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence and risk of recurrence in acute coronary syndrome patients: a meta-analytic review. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038915. e38915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Fan Z, Wu Y, Shen J, Ji T, Zhan R. Schizophrenia and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of thirteen cohort _studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:1549–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:936–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Grande G, Romppel M, Barth J. Association between type D personality and prognosis in patients with cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie (DGK) Infarkt-bedingter kardiogener Schock - Diagnose, Monitoring und Therapie. Langfassung. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/019-013l_S3_Infarkt-bedingter_kardiogener_Schock_Diagnose_Monitoring_Therapie_2010-abgelaufen.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E33.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, et al. European Society of Cardiology (ESC), ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:e344–e426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) SIGN. Edinburgh: 2013. Acute coronary syndromes. A national clinical guideline. Updated February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- E37.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz (BfS) Bekanntmachung der aktualisierten diagnostischen Referenzwerte für diagnostische und interventionelle Röntgenuntersuchungen. www.bfs.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/BfS/DE/fachinfo/ion/drw-roentgen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (last accessed on 26 June 2017) doi: 10.1055/a-1813-3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Bekanntmachung der aktualisierten diagnostischen Referenzwerte für nuklearmedizinische Untersuchungen. www.laekb.de/files/1456FC3088F/Referenzwerte_Nuklearmedizin.pdf (last accessed on 26 June 2017) [Google Scholar]